Abstract

The acquisition and use of a second language may impact a speaker’s first language, a phenomenon known as attrition. An area of particular interest for research on attrition has been the interpretation of subject pronouns in languages like Italian, which exhibit distinct biases for null and overt pronouns. That body of work has largely focused on overt pronouns, arguing that speakers’ biases for those forms weaken under attrition. However, we argue that previous results are more mixed than usually acknowledged; they also provide evidence that speakers undergoing attrition may exhibit a strengthening of their L1 (interpretive) biases more generally. To assess whether we should take this second trend seriously, the present paper investigates an apparent strengthening effect relating to null pronouns in Italian. For this, we conducted a sentence interpretation task with globally ambiguous sentences which included either a null or an overt pronoun. This task was presented to two groups of native Italian speakers, one in Italy and one in an English-speaking country. As predicted, results revealed a stronger interpretive bias for null pronouns under attrition. Therefore, we argue that theories of attrition should account for why speakers may exhibit not only a weakening of specific biases, but also a strengthening of their L1 biases more generally.

1 Introduction

While researchers have long recognized that one’s first language (L1) may affect the acquisition of a second language (L2), they have only more recently begun to study how acquiring an L2 may impact a speaker’s L1. This phenomenon, referred to as L1 attrition, can be observed in various aspects of language such as phonemic realization (e.g., Flege 1987) or lexical access (e.g., Linck et al. 2009) and diversity (e.g., Schmid and Jarvis 2014).

Within the syntactic domain, most research on attrition has focused on optionality between null and overt subjects in (consistent) null-subject languages such as Italian or Spanish. Although work on these forms has indicated that the underlying syntactic availability of null subjects is stable, authors generally report a relaxation of the discourse restrictions in the interpretation (Gürel 2004; Kaltsa et al. 2015; Tsimpli et al. 2004), production (Köpke and Genevska-Hanke 2018; Martín-Villena 2023), and online processing (Chamorro et al. 2016b) of overt pronouns.

This is convergent with work on multilingualism more generally which has found related asymmetries in bilingual children (e.g., Paradis and Navarro 2003; Serratrice et al. 2004; Sorace et al. 2009), adult heritage speakers (e.g., Keating et al. 2011; Montrul 2004), and late L2 speakers (e.g., Belletti et al. 2007; Montrul and Louro 2006; Sorace and Filiaci 2006). This has led to interest in the Interface Hypothesis (IH, Sorace and Filiaci 2006). Originally formulated as a dichotomy between the narrow syntax and interface structures, the IH was proposed to account for the observation that even highly advanced L2 speakers of null-subject languages exhibit non-convergence in their interpretation of overt pronouns despite having acquired the null-subject status of their L2. The proposal has since been extended to other multilingual populations and has evolved to a gradient distinction between more ‘external’ and more ‘internal’ interfaces, where the structures at the former are hypothesized to be harder to acquire/more susceptible to attrite than structures at the latter (Sorace 2011; Tsimpli and Sorace 2006).

In contrast to other work that has highlighted the convergence with other populations (e.g., Sorace 2011), however, the present paper will focus more narrowly on attrition. In doing so, we will show that the previous results are more mixed than is usually acknowledged. While there is indeed good evidence that attrition can lead to the relaxation of certain syntax-discourse mappings, there is also evidence that suggests speakers undergoing attrition can exhibit a more general strengthening of their L1 (interpretive) biases. To assess whether we should take this second trend seriously, the present paper presents an experiment in which we investigate how attrition affects the interpretation of globally ambiguous null and overt pronouns in Italian.

We take this study to be a novel contribution to the literature for two reasons. First, we believe that the tendency for speakers to rely more on their L1 biases under attrition has so far gone unnoticed. Second, results from the present study corroborate a notable example of this trend relating to null subjects in Italian, thereby increasing the credence that this effect should be taken seriously and accounted for.

2 Background and research questions

2.1 A working definition of attrition

Within the present paper, we take the term attrition to refer to any changes within an individual speaker’s L1 due to the acquisition and use of an L2 after the L1 had been acquired.[1] Therefore, attrition is distinct from language change due to pathology or language loss/change at the community level. Additionally, we restrict ourselves to adult attrition. In this sense, attrition is typically studied in migration contexts in which the potential attriter (i.e., the person undergoing attrition) has moved from their L1 community to their L2 community where they are likely to receive substantially less L1 input as well as substantially more L2 input.

An aspect of this definition that is worth highlighting is that we do not presuppose that attrition is the result of transfer from the L2. That is to say, we will not exclude the possibility that attrition may be the result of cognitive effects related to becoming bilingual. Although we take this assumption to be shared by other researchers (e.g., Chamorro et al. 2016a; Martín-Villena 2023; Sorace 2011), we believe that explicitly stating this assumption allows us to identify novel and potentially interesting patterns, as will become relevant below.

2.2 Pronominal biases in Italian

A fruitful domain for attrition research has been the syntactic optionality offered by Italian-style null-subject languages. In these languages, null subjects are licensed by agreement (Rizzi 1982, 1986) meaning that the subject of a well-formed finite clause may be phonologically overt or null (1a). This contrasts with non-null-subject languages like English (1b).

| (Raine e Maciej / ø) amano i gatti. | [Italian] |

| ‘(Raine and Maciej / they) love cats.’ |

| (Raine and Maciej / *ø) love cats. |

Despite this syntactic optionality, null and overt pronouns in Italian are constrained by discourse factors such as topicality and focus, with overt pronouns representing the ‘marked’ option (Cardinaletti and Starke 1999). When the referent of the subject represents a topic continuity, native Italian speakers prefer the production of null subjects. Conversely when the subject represents a shift in topic, native speakers disprefer null pronouns in favour of overt pronouns or non-pronominal DPs (e.g., Di Domenico et al. 2020; Sorace et al. 2009).

This asymmetry extends to comprehension, under the assumption that matrix subjects are generally treated as default sentential topics (Reinhart 1981). For example, Carminati (2002) found that native Italian speakers overwhelmingly interpreted null pronouns in sentences like (2) as referring to the matrix subject (80 %) and overt pronouns as referring to a non-subject antecedent (83 %). Subsequent studies with globally ambiguous items have supported this finding (e.g., Vogelzang et al. 2020: null 86 % subject, overt 61 % non-subject; Contemori and Di Domenico 2021: null 75 % subject, overt 80 % non-subject).

| Martai scriveva frequentamente a Pieraj quando (øi/?j/?k / lei?i/j/k) era negli Stati Uniti. | |

| ‘Marta wrote to Piera frequently when she was in the United States.’ | [Italian] |

Convergent results have also been reported by work on the online processing of pronouns in Italian. Using pragmatically disambiguated items like (3), Carminati (2002) found that native Italian speakers read the second clause slower when null pronouns were biased to corefer with the object of the preceding clause than when they were biased to corefer with its subject. The opposite pattern was observed with overt pronouns. These findings have since been replicated (Filiaci et al. 2014).

| Dopo che Giovannii ha criticato Brunoj così ingiustamente, (øi / luij) si è sentito offeso. | |

| ‘After Gianni criticized Bruno so unjustly, he felt offended.’ | [Italian] |

2.3 Attrition in null-subject languages

To investigate how the interpretive biases for (intrasentential) pronominal resolution are affected by attrition, Tsimpli et al. (2004) conducted a picture selection task. For this, the authors recruited L1-Greek and L1-Italian speakers who had achieved ‘near-native’ proficiency in their L2-English and had been immersed in their L2 for a minimum of six years. They additionally recruited a control group for each language. Items consisted of biclausal sentences in which the ambiguous pronominal form always appeared in the embedded clause. In half of their items, the matrix clause preceded the embedded clause (4a). In the other half, the order was reversed (4b).

| L’anziana signora saluta la ragazza quando (ø / lei) attraversa la strada. | [Italian] |

| ‘The elderly woman greets the girl when she crosses the road.’ |

| Mentre (ø / lei) esce dall’ascensore, l’infermiera urta la donna delle pulizie. |

| ‘While she exits the elevator, the nurse bumps into the cleaning lady.’ |

Sentences were presented along with three pictures corresponding to the logically possible interpretations of the pronoun: coreferential with the matrix subject, the matrix object, or some unspecified new referent. Participants were invited to select any and all images that corresponded to the given item.

When presented with overt pronouns, the control participants were expected to prefer matrix-object or new-referent interpretations (i.e., topic-shift, [TS], readings). When presented with a null pronoun, they were expected to prefer matrix-subject interpretations (i.e., non-TS readings). For the experimental groups, the authors predicted that English would influence the interpretable discourse features on overt pronouns in Italian (i.e., representational changes to the L1), but not the availability of null subjects. Specifically, they predicted a bleaching of the [+TS] featural specification for those pronouns, resulting in indeterminacy in their interpretation. For this task, the authors only presented the Italian data.[2]

For embedded-first items (4b) with null pronouns, the authors reported a significant preference for matrix-subject readings in both L1-Italian groups, with no difference between the groups. For embedded-first items with overt pronouns, the authors reported an interaction driven by a significantly stronger preference for new-referent readings in the control group than in the experimental group. No significant differences were reported for the rates of matrix-subject or matrix-object readings.

For matrix-first items (4a), significant interactions were observed for items with both null and overt pronouns. Within null items, this was driven by the fact that the experimental group opted for significantly more matrix-subject readings and significantly fewer matrix-object readings than the control group. For matrix-first items with overt pronouns, the interaction was driven by the experimental group selecting significantly more matrix-subject readings than the control group. No differences were reported between matrix-object or new-referent readings.

Tsimpli et al. (2004) interpret these results to support their hypothesis that attrition only affects interpretable features for two reasons. First, they observed an attrition effect in the interpretation of overt pronouns. Second, no effect of attrition was observed in the embedded-first items with null pronouns. However, there are some inconsistencies with their account. First, the attrition effect for overt pronouns in the embedded-first items (4b) is not capturable in terms of a change in the [+TS] specification of overt pronouns. That trend was driven by fewer new-referent interpretations by the experimental group who instead selected numerically – but not significantly – more matrix-object and matrix-subject interpretations. Second, the increase in matrix-subject interpretations for overt pronouns by the experimental group in the matrix-first items (4a) was modest (control: 7 %; experimental 21 %) and did not result in a loss of their TS bias. This is not what would be expected if the feature had become underspecified. Third, the increased non-TS bias observed in the matrix-first items (4a) with null pronouns cannot be captured under their account. Instead, the authors speculate that the experimental group may have misanalysed the embedded clause as being non-finite like (5), resulting in obligatory control by the matrix subject, a point to which we will return after considering data from other studies.

| The elderly woman greets the girl when crossing the street. |

Tsimpli et al. (2004) also report the results from their Greek participants from a picture selection task investigating the interpretation of a related property of null-subject languages, the syntactic optionality of pre- and postverbal subjects. In that task, an initial sentence always introduced a set of possible referents (6). A second sentence always contained an indefinite subject DP that could be interpreted as old or new information. Half the items contained a preverbal subject (6a) and half a postverbal subject (6b). After each item, participants were presented images corresponding to the two logically possible readings (old information, new information) as well as an invalid option. Participants were invited to select any and all images that matched the sentence. When participants selected both valid options, this was not recorded as a new and an old response, but rather as a separate category ‘both’.

| I gitonisa mu ston trito orofo apektise dhidhima. | [Greek] |

| ‘My neighbour on the third floor had twins.’ |

| Xtes vradhi ena moro ekleje. |

| Xtes vradhi ekleje ena moro. |

| ‘Last night a baby was crying.’ |

The control group was expected to prefer old readings for preverbal subjects and exhibit no clear bias for postverbal subjects. Under attrition, the experimental group was predicted to differ significantly in their interpretation of preverbal subjects only. In that case, they were expected to admit more new readings under the influence of English which requires a preverbal subject regardless of information status.

In the preverbal items, the experimental group selected significantly[3] fewer new readings and significantly more ‘both’ readings relative to the control group. No difference was reported for old readings. For the postverbal items, both groups exhibited indeterminacy, but in different ways. For the control group new, old, and ‘both’ were selected at similar rates. Conversely, the experimental group exhibited a clear bias for ‘both’ interpretations and opted for new and old readings around a fifth of the time. In this condition, the two groups differed significantly in their rates of old and ‘both’ readings.

Again, Tsimpli et al. (2004) interpret their results to support their hypothesis that attrition affects interpretable features only. They base this conclusion on the increased rate of ‘both’ readings for preverbal subjects which they take to indicate increased indeterminacy in the interpretation of preverbal subjects with regard to the feature [±Topic]. However, we should also note that their post hocs indicated no difference in old readings while also indicating that the experimental group selected significantly fewer – not more – new (i.e., non-Topic) readings. Thus, it seems more reasonable to attribute the increase in ‘both’ responses to the decrease in pure non-Topic readings. To see this more clearly, consider what would have happened if the authors had only considered the overall response rates of new and old, rather than treating ‘both’ as a separate category. The control group would have shown a modest bias in line with the expected preference for old readings (new: 46 % of items; old: 66 %, approximately[4]) whereas the experimental group would have shown a much more noticeable bias (new: 52 %; old: 86 %, approximately).

Applying the same logic to the results from postverbal items also affects our interpretation, albeit to a lesser extent. On the one hand, Tsimpli et al. (2004) interpret the experimental group’s (i) significantly higher rates of ‘both’ responses and (ii) lower rates of old responses to indicate increased indeterminacy. On the other, if we were to only consider the overall rates of new and old readings collapsing both, we see that the two groups pattern together and appear to show no bias (control: new: 57 %; old: 57 %; experimental: new: 72 %; old 70 % approximately[5]). Thus, it seems that the two groups do not actually differ in their interpretive biases (both showing indeterminacy) in line with Tsimpli et al.’s (2004) predictions, although the experimental group is overall more permissive.

Integrating the Greek and Italian results, it seems that only one of Tsimpli et al.’s (2004) attrition effects (matrix-first items with overt pronouns in Italian) provides clear evidence that attrition surfaces as the relaxation of restrictions relating to discourse features. Conversely, if the reader is willing to accept our re-interpretations presented above, two of their attrition effects (matrix-first items with null pronouns in Italian and preverbal subjects in Greek) appear to indicate that attriters exhibited a more pronounced version of an interpretive bias already present in the L1. Finally, the remaining two effects do not appear to relate to (interpretable) discourse features.[6] First, we should not attribute the decrease in other responses for embedded-first items with overt pronouns in Italian to a change in the [+TS] feature due to the lack of a significant difference in the rate of matrix-subject readings. Second, the increased acceptance rate for any interpretation of postverbal subjects in Greek cannot be attributed to a featural change.

A similarly mixed pattern can be observed in Gürel (2004). In that study, they were interested in how prolonged exposure to English might affect pronominal resolution in Turkish, another null-subject language (Şener and Takahashi 2010). In addition to null pronouns (ø), Turkish has two overt pronominal forms that may occupy the subject position: o (‘s/he’) and kendisi (‘self’). When these forms appear in contexts like in (7), o cannot be coreferential with the matrix subject. This contrasts with pronominal subjects in English (8) which admit either interpretation. The same asymmetry also does not hold for kendisi or ø.

| Buraki [(o-nun*i/j / kendi-si-nini/j / øi/j) zeki ol-duğ-u]-nu düşün-üyor. | [Turkish] |

| ‘Burak thinks that [he/self/ø is intelligent].’ |

| Johni believes [hei/j is intelligent]. |

For Turkish, Gürel (2004) predicted attrition to be selective. This is couched in terms of the Activation Threshold Hypothesis (ATH, M. Paradis 1993, 2007) which proposes that the less a given form is used, the higher its threshold for activation (i.e., it is less available) and vice versa. Under this proposal, attrition is predicted when a form in the L1 has a ‘competing’ form in the L2 with a lower activation threshold. Relevant to the present discussion, Gürel (2004) assumed that the overt pronoun o in Turkish competes with overt English pronouns such as he. Therefore, they predicted o would begin to admit matrix-subject readings in sentences like (7) under pressure from the L2. However, English does not admit null subjects, nor does it have a pronoun analogous to kendisi in subject position. Consequently, those forms were predicted to remain stable.

To test this idea, Gürel (2004) recruited a group of native Turkish speakers who had emigrated after the age of sixteen and had lived in English-speaking countries for a minimum of ten years. L2 proficiency was not assessed, but participants were assumed to be highly proficient in their L2-English given their professional and educational backgrounds. A control group still residing in Turkey was also recruited. This group did not consist of idealized monolinguals and were deemed competent enough in English to take part in the story task.[7]

Participants were presented three tasks. In the written interpretation task, participants saw a series of sentences similar to (7). Within those items, the author manipulated the pronominal form (o, kendisi, ø) and whether the potential antecedent was referential or quantified (e.g., Burak vs everyone). After each sentence, participants were asked to indicate their interpretation of the embedded subject selecting from three options: coreferential with the matrix subject (e.g., Burak), disjoint reference (i.e., someone else), or both.

Similar items were used in the story-based and picture-based truth-value judgement tasks. However, in those tasks, participants were presented either a short story in English or a picture along with each item. This was done to provide a context in order to force particular interpretations of the pronominal elements. Against these story contexts, participants were asked to judge whether the following Turkish sentence was true or false.

Results from the written interpretation task indicated that both groups almost always selected the disjoint reading and almost never interpreted o as coreferential with the matrix subject. Statistical analyses indicated that the only difference between the two was that the experimental group selected subject interpretation marginally more frequently than the control group in quantified items. No difference was found for referential antecedents. Moreover, no statistically significant differences were found in the rates of ‘both’ (i.e., subject or disjoint) readings.

As for kendisi, the control group preferred ‘both’ interpretations and never selected disjoint readings. The experimental group similarly dispreferred disjoint readings. However, they rarely gave ‘both’ responses and instead strongly preferred subject interpretations. A similar, but less pronounced, shift away from ‘both’ and toward subject readings by the experimental group was also attested for null pronouns. For both pronominal types, these shifts toward more subject readings were significant.

For the story-based truth-value judgement task, both groups preferred disjoint reading for o and subject readings for kendisi and ø. The only significant difference between the groups surfaced with o. While the control group almost never accepted subject readings, the experimental group did so at a higher rate for both referential and quantified antecedents. Similarly, in the picture-based task, the control group categorically rejected bound readings whereas the experimental group accepted such readings in a subset of trials. However, in that task, significant differences were also observed within kendisi and null pronominal items. Although both groups preferred subject readings, this bias was stronger in the experimental group.

Gürel (2004) interprets their results to indicate three things. First, the distinction between the o and the other two pronouns is maintained under attrition. Second, attriters begin to treat o more like ‘he’ under pressure from English, consistent with the ATH. Third, they take the increased bias toward subject readings for kendisi and ø to indicate that the experimental group exhibited a reduced awareness of the ambiguity for those pronouns.

However, integrating the results from their two truth-value judgement tasks we might come to an alternative interpretation. In those tasks where participants were forced to accept or reject a particular reading, participants did not exhibit indeterminacy. Rather, all participants preferentially interpreted ø and kendisi as referring to the matrix subject (values ≥ 74 %). Therefore, it seems reasonable to suggest that Turkish speakers exhibit a matrix-subject bias in the interpretation of the relevant forms. Integrating this with their written task results, we might suggest that the experimental participants are not less aware of the ambiguity, but instead more sensitive to their L1’s matrix-subject bias in that context.

Integrating the Turkish findings with those from Tsimpli et al. (2004) then, there are two parallels worth highlighting. First, the results from Gürel’s (2004) two truth-value judgement tasks indicate that o in Turkish is susceptible to attrition similar to overt pronouns in Italian, with matrix-subject readings becoming more prevalent. Moreover, the effect in Turkish (story-based: referential: 4 % vs 30 %; quantified: 3 % vs 22 %; image-based: referential: 0 % vs 21 %) is similar in magnitude to the effect observed in matrix-first items with overt pronouns in Italian (7.6 % vs 21.2 %). Clearly, in neither case have the attriting participants lost the L1 bias, despite its relaxation. Second, under our re-interpretation, the results for ø and kendisi in Turkish are convergent with Tsimpli et al.’s (2004) results for the matrix-first null pronominal items in Italian and the preverbal items in Greek. In those cases, a bias already present in the L1 appears to have strengthened under attrition. Moreover, the results from Gürel’s (2004) interpretation task are replicable (Gürel and Yılmaz 2011), suggesting we should not consider them spurious.

A convergent pattern was also observed in two studies by Martín-Villena (2023). For a pilot study exploring the role of conjunctions on pronominal reference, Martín-Villena (2023) recruited a large sample of native (Iberian) Spanish speakers (N = 131) who had grown up monolingually and were still residing in Spain (Martín-Villena, p.c.). However, seventy-six considered themselves ‘highly proficient’ in their L2-English, while fifty-five considered themselves as ‘not [being] proficient enough in English’.

Their experimental method and items were adapted from the pronominal sentence interpretation task in Tsimpli et al. (2004). In this Spanish version, the matrix clause always preceded the embedded clause and the type of conjunction (mientras – ‘while’, cuando – ‘when’) was manipulated. Items were presented with images corresponding to subject, object, and other interpretations of the ambiguous pronoun. Participants were instructed to select their preferred interpretation.

| La anciana saludó a la mujer cuando ella cruzaba la calle. | [Spanish] |

| ‘The elderly woman greeted the woman when she crossed the street.’ |

| El padre saludó al hijo mientras él montaba en bicicleta. |

| ‘The father greeted the son while he was riding a bike.’ |

Focusing on their most relevant results, Martín-Villena (2023) reported a significant L2-level by pronoun interaction which was driven by more object interpretations for the highly proficient L2ers in the overt conditions, i.e., participants who deemed themselves more proficient in their L2 exhibited a stronger – not weaker – TS bias in their interpretation of overt pronouns. This is unexpected under a feature-based account like that in Tsimpli et al. (2004) or the ATH but fits with the novel pattern noted in the Greek, Italian, and Turkish results above. Of course, one might reasonably object that even though these are ‘highly proficient’ L2ers, they were still residing in their L1 community and as such may not be representative of prototypical attriting populations in migration contexts. To that end, we turn to Martín-Villena’s (2023) main study.

For their main study, Martín-Villena (2023) conducted an almost identical picture selection task to explore potential attrition effects using three groups of native (Iberian) Spanish speakers who had grown up monolingually: a control group, an immersed experimental group, and an instructed experimental group. The control group consisted of ‘functionally monolingual’ speakers who had never lived abroad and had minimal contact with English. The immersed bilingual group consisted of a large number of participants (N = 94) who were living in the UK or Ireland and had emigrated after the age of 15 years. The instructed experimental group consisted of a large number of participants (N = 80) still residing in Spain who were studying for English Studies degrees and received non-trivial English input. Both experimental groups were assessed to be highly proficient in their L2-English.

For that main task, Martín-Villena (2023) based their predictions on both the IH and the ATH. Starting with the IH, they predicted a relaxation of the TS bias for overt pronouns. However, they follow a more recent instantiation which focuses on potential processing-based explanations (Sorace 2011, 2016) rather than representational change. This shift toward a processing-based account is based on two ideas: (i) that the felicitous use of pronominal forms requires rapid, real-time integration of contextual and linguistic information and (ii) that bilinguals may be less efficient in this process (potentially due to cognitive load related to language control or a trade-off between increased inhibitory control and updating). Under this account, the overexertion of overt pronouns compensates for bilinguals’ difficulties with real-time integration as overt pronouns have been suggested to function as a processing default in languages like Italian (Sorace 2011). Following the ATH, Martín-Villena (2023) additionally predicted the attrition effect to be more pronounced in the immersed group relative to the instructed one.

Focusing on their most germane results, Martín-Villena (2023) observed significant group-by-pronoun interactions. Convergent with their pilot results, these interactions were driven by a significantly stronger TS bias for overt pronouns for both experimental groups relative to the control group, with no difference between the experimental groups.

Complicating the picture, however, Martín-Villena (2023) used the Bilingual Language Profile questionnaire (BLP, Birdsong et al. 2012) to assess participants’ language dominance. This indicated that all groups were still L1 dominant with the difference between the two languages most pronounced for the control group and least pronounced for the immersed group. Modelling revealed that in addition to the group-by-pronoun interaction, there was also a significant BLP score by pronoun interaction, surfacing as a weaker TS bias for overt pronouns in participants who were less L1 dominant. On the surface, this seems to converge with previous work that has reported a weaker TS bias for overt pronouns under attrition. However, this conflicts with the Martín-Villena’s (2023) own findings (pilot and main study). Martín-Villena interprets this conflict as evidence that we should move beyond dichotomous groups and instead investigate attrition with continuous measures such as dominance (2023: xxi, 292). However, the interaction with BLP score does not negate the interaction with group. Moreover, if dominance (as measured by an index like the BLP) is the factor that we should be interested in when exploring attrition, rather than the traditional factor of group, we might predict that the interaction with BLP score should survive in a simplified model which does not include group. This is not the case (Martín-Villena p.c.); the significance of the interaction with BLP score depends on the inclusion of the interaction with group, but not vice versa. That observation in turn raises the question of what relevant aspect of the participants the BLP is tapping.

More recent work on attrition and pronominal resolution in Italian, however, does not fit nicely into the emerging pattern noted in the studies discussed above. For their study, Gargiulo and van de Weijer (2020) recruited two groups of native Italian speakers: a control group in Italy and an experimental group in Sweden. Although that group had grown up in Italy, they had migrated to Sweden at least seven years prior to testing (mean = 11.83) and rated themselves as highly proficient (4.75/5) in Swedish, a non-null-subject language. Both groups completed a sentence interpretation task using items as in (10).

| Monica ha discusso molto con Antonella da quando (ø / lei) è tornata da Parigi. |

| ‘Monica has argued a lot with Antonella since she came back from Paris.’ [Italian] |

However, as Gargiulo and van de Weijer (2020) were interested in how re-immersion in a speaker’s L1 community affects attrition (on which see Chamorro et al. 2016b), they had experimental participants complete their task twice, once before their summer holidays in Italy (min 11 days, mean = 23.2) and a second time as soon as possible after their return to Sweden (mean = 2.95 days). For consistency, the control group also participated twice with a minimum of twenty days between test sessions (mean = 22 days).

Results indicated that both groups exhibited the expected interpretation biases for null and overt pronouns; they preferentially selected subject readings for null pronouns and non-subject readings for overt pronouns. However, the effect of pronoun interacted with session. The authors interpreted this to be driven by an increased non-TS bias for null pronouns in the second testing session. The effect of pronoun also interacted with group (i.e., an effect of attrition). Based on visual inspection, this was interpreted as being driven by a weaker non-TS bias for null pronouns in the experimental group contra Tsimpli et al. (2004) despite a similar trend in the data for overt pronouns. The authors suggest that the change in the interpretation of null pronouns is due to a locality effect (Table 1)

Rate of non-TS responses by group and pronoun in both sessions adapted from Gargiulo and van de Weijer (2020)(Table 1).

| Session | Control | Experimental | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Null | Overt | Null | Overt | |

| First | 78 % | 9 % | 74 % | 16 % |

| Second | 88 % | 11 % | 80 % | 13 % |

Thus, summarizing the above, while there is evidence that attrition can lead to the relaxation of the TS bias for overt pronouns (e.g., Italian: Tsimpli et al. 2004; Turkish: Gürel 2004; Greek: Kaltsa et al. 2015; Spanish: Martín-Villena 2023), there is also evidence that attrition can lead to a strengthening of the TS bias instead (Spanish: Martín-Villena 2023). Moreover, the latter of these two effects appears to be part of a more general pattern as strengthening of interpretive biases is observed in a wider range of contexts. This sometimes appears where there is no (surface) overlap between the L1 and the L2 (e.g., ø: Italian: Tsimpli et al. 2004; Turkish: Gürel 2004; Gürel and Yılmaz 2011; reflexives: Turkish: Gürel 2004; Gürel and Yılmaz 2011), and sometimes surfaces in instances of overlap (e.g., overt pronouns: Spanish: Martín-Villena 2023; preverbal subjects: Greek: Tsimpli et al. 2004). Given the different structures involved, it is clear we cannot maintain Tsimpli et al.’s (2004) suggestion that attriters sometimes misanalyse sentences with null pronouns as non-finite resulting in obligatory control. Nor can this pattern be captured by the ATH or a processing-based version of the IH that assumes overt pronouns function as a processing default. Rather we suggest that the increased reliance on interpretive biases might be a general (cognitive) effect under attrition. Nonetheless, a sceptical reader might object (i) that our interpretation of the data leads to a radically different view of attrition (ii) that it is based on a small number of studies, and (iii) that there are some potentially contradictory results for null pronouns in Italian (Gargiulo and van de Weijer 2020). Therefore, we might worry whether the effects are spurious. To that end, the present paper presents an experiment to further investigate how attrition affects the interpretation of pronouns – both null and overt – in Italian. For this, we drew the following research questions:

RQ1:

In Italian matrix-first sentences, can we observe a weakening of the TS bias for overt pronouns under attrition?

RQ2:

In Italian matrix-first sentences, can we observe a strengthening of the non-TS bias for null pronouns under attrition?

3 Methods

3.1 Participants

For this experiment, we recruited two groups of native Italian speakers who had grown up monolingually[8] in Italy until at least the age of sixteen and reported no diagnosed language-related disorders.

The control group comprised thirty-three participants who were living in Italy. As part of a background questionnaire, participants were asked to list the languages they spoke at or above an ‘intermediate’ level. They were additionally asked to indicate how often they used each of these languages in a typical day. That revealed that these participants were not idealized monolinguals, with thirty reporting speaking some language other than Italian. Of those participants who spoke another language, all reported speaking English. To quantify language use in a typical day, we calculated percentages for each language. Table 2 presents group means and standard deviations for the use of Italian, English, and other. At the time of testing, the mean age of these participants was 40.91 years (SD = 6.40; range = 35–57)

Mean language use by participants as percentages of a typical day with standard deviations.

| Control | Experimental | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Italian | 85 % | 14% | 23 % | 19 % |

| English | 13% | 11 % | 76% | 19 % |

| Other | 2% | 5 % | 1 % | 3 % |

The experimental group comprised twenty-nine participants who had been living in a majority English-speaking country for a minimum of six years (cf. Tsimpli et al. 2004) at the time of testing (mean = 14.27 years; SD = 7.89; range = 6.17–40.58).[9] To avoid possible re-exposure effects (Chamorro et al. 2016b), experimental participants were pre-screened to ensure they had not travelled back to the L1 community in the three months prior to testing. Group means and standard deviations for the use of Italian, English, and other languages as percentages of a typical day are presented in Table 2. As some previous work that had restricted itself to ‘near-natives’ (e.g., Chamorro et al. 2016a, 2016b; Tsimpli et al. 2004), experimental participants took the Cambridge Assessment General English quick placement test. On average, experimental participants scored 21.76/25 (SD = 1.66; range = 18–24), suggesting that they are likely upper-intermediate/advanced L2 speakers. This group was comparable in age to the group still residing in Italy (mean age in years = 43.48; SD = 7.18; range = 36–66).

3.2 Stimuli

Critical items (N = 20) were adapted from Tsimpli et al.’s (2004) picture selection task. These sentences vary by pronoun (null or overt) and order (matrix-first[10] vs embedded-first). As it was unclear whether the original items were fully counterbalanced, we adapted the items by counterbalancing the pronominal subject in each sentence. This was done to ensure that any effect of pronominal type in later modelling was not due to differences in the items used in the null and overt conditions. An example of the four conditions for the pronominal items is presented in (11). Sentences were distributed across two lists such that each participant saw each item once, five in each condition.

| Matrix-first null condition | |

| L’anziana signora saluta la ragazza [quando ø attraversa la strada]. | [Italian] |

| Matrix-first overt condition |

| L’anziana signora saluta la ragazza [quando lei attraversa la strada]. |

| ‘The old woman greets the girl when she crosses the road.’ |

| Embedded-first null condition |

| [Mentre ø guarda l’orologio] l’anziana signora si avvicina alla donna delle pulizie. |

| Embedded-first overt condition |

| [Mentre lei guarda l’orologio] l’anziana signora si avvicina alla donna delle pulizie. |

| ‘While she looks at the clock the old woman moves toward the cleaning lady.’ |

The experiment also included distractor sentences (N = 24) and filler items (N = 26), both of which were biclausal. Distractor sentences contained pseudorelative-relative clause parsing ambiguities and are reported in Cairncross et al. (2024). Filler items consisted of unambiguous co-ordinated sentences as in (12).

| Cecilia abita negli Stati Uniti e Camilla abita in Giappone. |

| ‘Cecilia lives in the United States and Camilla lives in Japan.’ |

3.3 Procedure

Participants were recruited via Prolific Academic, and the study was implemented using PCIbex (Zehr and Schwarz 2018). After providing informed consent, participants completed a short language background questionnaire. Experimental participants then completed the English-placement test. Finally, all participants completed the sentence interpretation task during which they were presented sentences in isolation. After reading each sentence participants pressed the space bar, causing the sentence to be replaced by a comprehension question.[11] For critical items, this always asked about the participants’ interpretation of the ambiguous pronoun.[12] Below the comprehension question, three potential answers were always written, one for each of the NPs mentioned in the item as well as the option qualcun altro (‘someone else’). Potential responses were labelled ‘F’, ‘J’, and ‘B’. While the positions of the two textually given possible responses were counterbalanced such that the NP which was mentioned first appeared as the ‘F’ option in half of the trials (and as the ’J’ option in the other half). Qualcun altro (‘someone else’) always appeared as the ‘B’ option. To submit their preferred interpretation, participants used their keyboards. The study lasted approximately 30 minutes and participants were paid £4.50. Prior to testing, ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Modern and Medieval Languages and Linguistics at the University of Cambridge.

3.4 Hypotheses and predictions

The following hypotheses were drawn in relation to RQ1 and RQ2 respectively:

H1:

For overt pronouns in the matrix-first items, the experimental group will exhibit a weaker TS bias than the control group.

H2:

For null pronouns in the matrix-first items, the experimental group will exhibit a stronger non-TS bias than the control group.

Therefore, within the matrix-first items we expected a main effect of group as well as a main effect of pronoun. Specifically, based on the findings in Tsimpli et al. (2004) (see Section 2.2), we expected the control group to select subject interpretations around chance level for null pronouns while the experimental group would display a non-TS bias. For overt pronouns in the same items, both groups were expected to exhibit a TS bias, although this is expected to be weaker in the experimental group.

3.5 Data cleaning and analysis

We coded as missing any trial for which the sentence reading time or the question response time were implausibly fast (implemented as < 1500 ms and < 500 ms respectively), affecting 0.72 % of the data.

Prior to data collection, we made two decisions about our planned analyses that are worth highlighting. First, we decided that the matrix-first items should be modelled separately from the embedded-first ones. This was motivated by the fact that our research questions are not about whether attrition significantly affects pronoun-antecedent biases in one of the orders more than the other. Rather, we are specifically interested in how the pronoun-antecedent biases are affected within the matrix-first items. Second, we decided to collapse the distinction between non-subject and other readings (original responses available on OSF). Although we included both as they are natural responses to the target questions and increased the comparability to Tsimpli et al. (2004), we are only theoretically interested in the TS/non-TS distinction.

For expositional ease, only the results from the matrix-first items (i.e., those items relevant for our research questions) are presented below. Results for the embedded-first items are available on the associated OSF page.

To analyse the data, responses were coded as ±subject and were entered into a mixed effect logistic regression using the lme4 package (Bates et al. 2015) in R (R Core Team 2022). Using an empty model, we selected the best fitting random-effects structure for our within-participant fixed effect (i.e., pronoun, Matuschek et al. 2017) using the Akaike Information Criterion. We then entered pronoun (negative level = null) and group (negative level = control) as fixed effects using sum coding.

4 Results

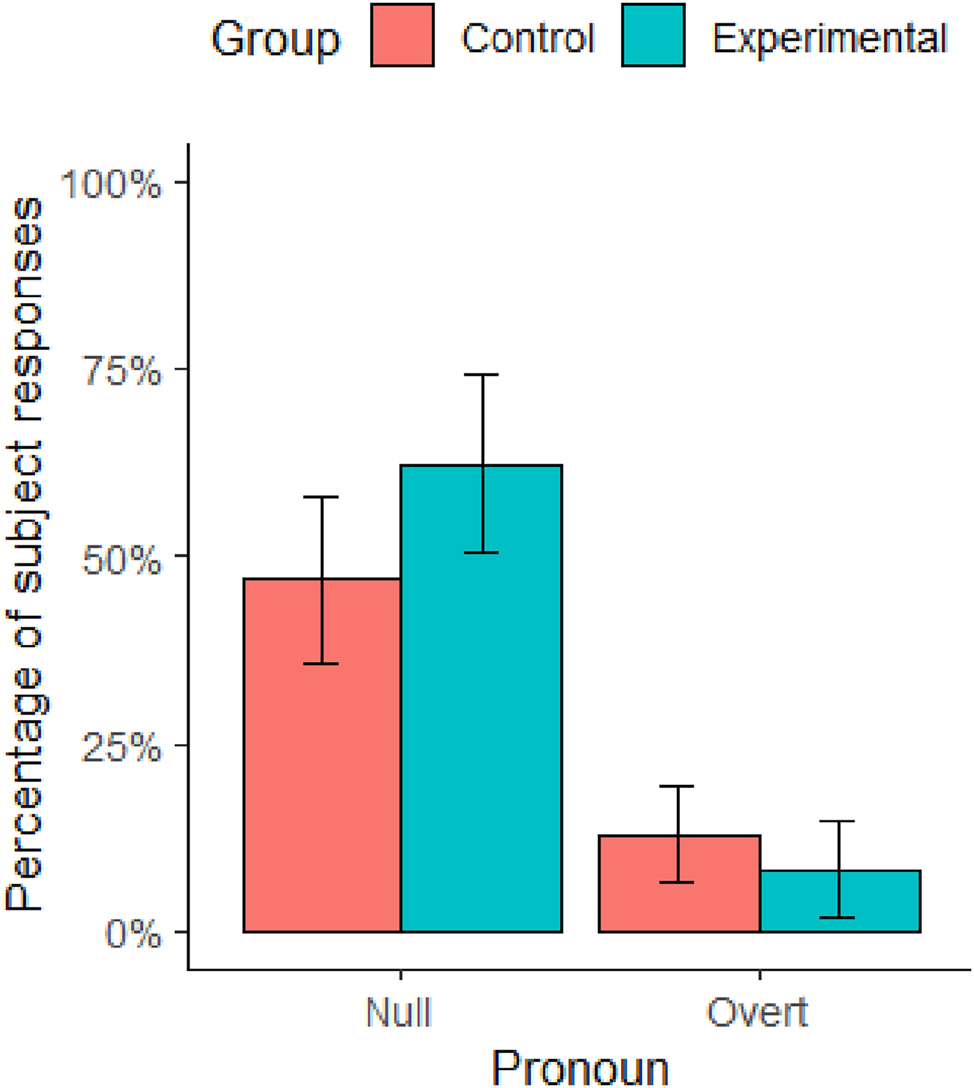

Figure 1 presents the percentage of subject responses after matrix-first items broken down by group and pronominal form. In those items, the control group selected subject interpretations for null pronoun at around chance levels whereas there was a slight subject bias in the experimental group (control: 46.97 %; experimental: 62.22 %). In the overt items, both groups preferred non-subject interpretations (control: 12.88 %; experimental: 8.28 %). The model output is presented in Table 3.

Subject response rates (by participant) for the matrix-first items by group and pronominal form with 95 % confidence intervals.

Model output for the matrix-first pronominal sentence interpretations with pronoun (negative level = null) and group (negative level = control) as sum coded predictors.

| Est. | CI | Std. error | z-Value | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −1.53 | −2.21 – −0.85 | 0.35 | −4.43 | <0.001 | *** |

| Pronoun | −2.90 | −4.35 – −1.45 | 0.74 | −3.91 | <0.001 | *** |

| Group | 0.03 | −0.69 – 0.74 | 0.36 | 0.08 | 0.94 | |

| Pronoun:Group | −1.49 | −2.87 − −0.10 | 0.71 | −2.11 | 0.04 | * |

The model indicated a significant effect of pronoun (βˆ = −2.90; z = −3.91; p < 0.001). This surfaced as fewer subject interpretations with overt pronouns. The model did not indicate a significant effect of group. However, the interaction between pronoun and group was significant (βˆ = −1.49; z = −2.11; p = 0.04). To follow up on that significant interaction, we then conducted pairwise comparisons using the emmeans package (Lenth 2022) and report Holm–Bonferroni corrected p-values. This indicated that the effect of pronoun was significant in both groups (control: βˆ = −2.16; z = −2.88; p = 0.01; experimental: βˆ = −3.64; z = −4.11; p < 0.001). In both cases, this was due to fewer subject interpretations with overt pronouns. The effect of group within the overt pronominal items was non-significant, and only marginal within the null pronominal items (βˆ = 0.77; z = 2.10; p = 0.07).

5 Discussion

In this paper, we reported a sentence interpretation task to investigate two potential attrition effects in Italian. Namely, we predicted the experimental group to exhibit a weakening of the TS bias for overt (H1) as well as a strengthening of the non-TS bias for null pronouns (H2) relative to the control group resulting in a main effect of group. Statistical modelling confirmed a main effect of pronoun. However, instead of a main effect of group, modelling indicated an interaction with pronoun with the experimental group exhibiting numerically more exaggerated interpretive biases for both null and overt pronouns. Given that the post hoc tests within the two pronominal conditions were not significant after correcting p-values, there seem to be two possible interpretations of this interaction. We might suggest that this interaction was driven by a stronger non-TS bias for null pronouns given that the TS bias for overt pronouns was only larger by about five percentage points in the experimental group whereas the experimental group’s non-TS bias for null pronouns was about fifteen percentage points larger than the control group’s. Alternatively, we might suggest that this effect was driven by the numerically more exaggerated biases for both null and overt pronouns, despite the trend being noticeably smaller in the latter. Regardless of which interpretation the reader takes to be more reasonable, this means that experimental participants exhibited a stronger non-TS bias for null pronouns than the control group, confirming (H2).

This raises the question of how we should interpret this attrition effect, given that our control group selected non-TS interpretation at around chance levels. We believe that this should be interpreted as an increased reliance on the non-TS bias already present in the L1, which is to some degree obfuscated in these particular items. This is because, as noted above, previous studies using different sets of intrasentential items have found (adult) native Italian speakers to exhibit a clear and reliable non-TS bias in both their interpretation (e.g., 80 % in Carminati 2002; 86 % in Vogelzang et al. 2020; 75 % in Contemori and Di Domenico 2021), and their processing of null pronouns (e.g., Carminati 2002; Filiaci et al. 2014 [13]). Conversely, previous studies with these specific (matrix-first) items have found Italian control groups’ rate of non-TS interpretation for null pronouns to be around 50 % (e.g., 50.8 % in Tsimpli et al. 2004; approximately[14] 40 % in Belletti et al. 2007; approximately 54 % in Serratrice 2007, although see also Kraš 2008 who observed a 72 % non-TS response rate with a modified version of these stimuli), suggesting that this is an experimental artefact of these specific items.

Integrating overt pronouns into our increased bias interpretation, if the reader takes our interaction to indicate that overt pronouns were also affected by attrition (albeit to a lesser extent than null pronouns), our results are straightforwardly compatible. Conversely, if the reader interprets our interaction to have been driven by a change in the items with null pronouns only, then it is worth highlighting that the responses from the control group were already relatively extreme for matrix-first items with overt pronouns. For those items, the control group selected non-TS readings in only 12.88 % of trials. This imposed a logical limit on any potential strengthening of the non-TS bias given that the percentage of non-TS responses could not fall below zero. This issue is further compounded by the globally ambiguous nature of the items themselves. That is to say, it would be unreasonable to expect fully categorical judgements (i.e., 0 % subject) given that other responses were still possible. Thus, even if attrition were to have led to a strengthening of the TS bias for overt pronouns in our experimental participants, any effect would have been subtle and difficult to detect with our items due to a floor/ceiling effect. Thus, regardless of the reader’s preferred interpretation, results from overt pronouns are compatible with our increased biases interpretation.

At this point, we should stress that we are not arguing that attrition must always lead to an increased reliance on biases already present in the L1. That position would be too strong. There is good evidence that attrition may lead to a relaxation of the TS bias for overt pronouns as predicted by accounts like Sorace’s (2011, 2016) overt-as-processing-default idea or Paradis’s (1993, 2007) ATH. That effect for overt pronouns clearly does not follow from the kind of bias-couched account discussed above. A potential response might be to suggest that we need a mixed account, i.e., a bias-couched account to capture the general strengthening effect plus the reader’s preferred account for the overextension of overt pronouns. This seems possible at least in principle because a biases-couched account is not mutually exclusive with the above-mentioned processing-based accounts. However, a mixed account would come at the cost of parsimony. More problematically, it would make conflicting predictions for overt pronouns. Although undesirable, this may be necessary based on the currently available data. There seems to be inconsistency in the way that attrition surfaces for overt pronouns specifically, i.e., where we would expect the two tendencies discussed above to conflict (e.g., compare Martín-Villena 2023; Tsimpli et al. 2004 or Cairncross 2024; Chamorro et al. 2016b), suggesting that we should somehow incorporate this variability of outcomes into our models.

Nonetheless, without some restriction on when we should expect a weakening or a strengthening of biases when the two tendencies conflict, a mixed account of attrition would be unfalsifiable in these contexts. One potential way to resolve the observed inconsistencies across studies might be to follow the Form-Specific Multiple Constraints approach of Kaiser and Trueswell (2008). Those authors suggest that pronominal resolution is affected by multiple factors and that these multiple factors may affect specific pronominal forms differently. Transferring this idea to null-subject languages like Italian, experiments with native (non-attriting) speakers have found that the TS bias for overt pronouns is more flexible and sensitive to contextual factors than the non-TS bias for null pronouns (Carminati 2002). This raises the possibility that the conflicting results for overt pronouns between studies may relate to the different set of items/tasks employed. Consistent with this idea, recall that Martín-Villena (2023) reported very similar increased TS bias for overt pronouns in three distinct (and relatively large) samples of Spanish speakers using the same stimuli and task. Nonetheless, given the currently available results we cannot tease out what specific factors might play a role in the conflicting results for overt pronouns, and so this idea remains speculation.

Alternatively, one might try to resolve the inconsistency in attrition results by moving beyond the traditional factor of group, instead focusing on specific aspects of language experience (e.g., language exposure or dominance). Some credence for this idea may also be drawn from Martín-Villena (2023), who explicitly argues for a version of this idea, albeit for slightly different reasons. Recall that in that study, group membership was associated with a stronger overt pronoun bias for the bilingual groups. However, in the same model, becoming less L1 dominant, as measured by the BLP, was associated with a weaker bias for overt pronouns (i.e., the opposite effect). This was despite the two bilingual groups being less L1 dominant than the functional monolinguals. Under earlier accounts of attrition that have focused narrowly on the relaxation of the interpretive/processing bias for overt pronouns, this conflict within participants cannot be easily resolved. However, under a mixed account like that proposed above which explicitly acknowledges competing pressures under attrition, such results can straightforwardly be accommodated; while decreasing L1 dominance leads to a weakening of the TS bias for overt pronouns, some other (unspecified) aspect of bilingualism leads to an increased reliance on L1 biases. In a similar vein, acknowledging competing pressures may allow for the incorporation of Gargiulo and van de Weijer’s (2020) argument that attrition can lead to an increased locality effect resulting in a reduced non-TS bias for null pronouns, which would otherwise be uncapturable under any of the proposals discussed above. However, this all remains speculative, as the present study was not designed to tease apart how various aspects of speakers’ language backgrounds differentially affect pronominal resolution. Therefore, we do not have sufficiently detailed background information nor a suitable sample to explore this avenue further. Additionally, it is not currently clear which variables we should focus on first. Yet, as should be stressed, any future work in this direction should be hypothesis-driven given the large number of potentially relevant variables when working with bilingual populations.

The only potential restrictions that we can seem to exclude based on the current data are (i) the idea that the more specific tendency (i.e., overextension): always trumps the more general tendency (i.e., to rely more on the L1 biases) and (ii) the idea that the inconsistent effect of attrition can be entirely resolved by pointing to cross-linguistic differences given that conflicting results have been found within (Iberian) Spanish (Chamorro et al. 2016b; Martín-Villena 2023). Beyond this we leave the question of how to resolve the apparent inconsistency of attrition to future work.

A related but thornier question that must be answered if we are to maintain a bias-couched account of the type suggested above is: why should speakers undergoing attrition exhibit a strengthening of their L1 biases? This was not a question the present study was designed to answer. However, recent results indicating strengthening effects may also appear in online measures (Cairncross 2024) seem to suggest that this cannot be driven by meta-linguistic awareness (under the assumption that such effect should be restricted to/more prominent in offline tasks where participants have time to explicitly reason about their responses). Instead, following Sorace (2011, 2016), we might speculate about the role of cognitive load due to real-time reference maintenance or even language control. Recasting their idea that overt pronouns function as a processing default that can alleviate processing load in bilinguals, one might suggest that biases in general can serve this function. This seems to predict that we might also observe strengthening in other bilingual populations such as L2 speakers with the opposite language pairs (e.g., L1-English, L2-Italian). However, we are unaware of any such effects in L2-Italian (e.g., Belletti et al. 2007; Sorace and Filiaci 2006, who used the same items). As such, we leave open the question of why speakers might exhibit stronger biases under attrition.

As a final point, it is worth discussing a salient alternative to our Increased Biases Hypothesis, which we might call the Increased Topicality Hypothesis. Although we found evidence of an increased non-TS bias for null pronouns and, under one interpretation of our interaction, no change in the items with overt pronouns, previous studies (e.g., Chamorro et al. 2016b; Gürel 2004; Kaltsa et al. 2015; Martín-Villena 2023; Tsimpli et al. 2004) have reported a relaxation of the TS bias under attrition. As such, one might argue that instead of some biases becoming weaker while others become stronger, pronouns in general begin to prefer more topical interpretation under attrition. Such an account would have an advantage of parsimony. It could also be straightforwardly extended to the increased topicality bias observed for preverbal subjects in Greek (Tsimpli et al. 2004) as well as the increased matrix-subject interpretation for null pronouns and kendisi in Turkish (Gürel 2004; Gürel and Yılmaz 2011).

In fact, while this manuscript was under review, something similar to this idea was proposed by Contemori and Mossman (2024). For their study, they recruited two groups of native (Mexican) Spanish speakers: an experimental group that spoke intermediate to advanced L2-English and a control group of monolinguals. Both groups completed a sentence interpretation task in Spanish with matrix-first items similar to that in the present study (13). The L2-English group additionally completed an English version of the task (14), for which a monolingual English group was also recruited.

| Pedro saludó a Carlos cuando (ø / él) cruzaba la calle. | [Spanish] |

| ‘Pedro greeted Carlos when he crossed the street.’ |

| Adam chatted with Nick when he was watching TV. |

Results from the Spanish version of the task indicated that although both groups exhibited an effect of pronoun, there was also a significant effect of group. This was driven by experimental participants selecting significantly more non-TS interpretations regardless of pronominal form (null: 75 %, overt: 52 %) relative to the control group (null: 68 %, overt: 43 %) i.e., they observed an increased topicality effect. However, rather than attributing this to a cognitive origin, Contemori and Mossman (2024) interpret their effect as being driven by cross-linguistic influence (contra the assumption in earlier work like Gürel 2004 that the overt pronoun in the L2 does not influence/compete with the null pronoun in the L1). This is because native speakers of English exhibit a first-mention bias in the interpretation of pronouns like in (14) and this is acquirable by L2 speakers (their control: 75 %; experimental: 68 %). Moreover, individual differences in their experimental participants’ rates of non-TS interpretations in the English version of the task significantly correlated with their rates of non-TS interpretation in the Spanish version of the task, regardless of pronoun type.

While this effect is indeed compatible with a cross-linguistic-influence-based explanation like they suggest, it cannot be used as an argument against a cognitively couched one, as even acknowledged by Contemori and Mossman (2024). After all, without further restriction, cognitive effects would be expected to influence all of a speaker’s languages. Moreover, although not directly compared, the first-mention/non-TS bias observed in the L2-English of their experimental participants was not meaningfully larger than the non-TS bias observed for null pronouns in their monolingual Spanish participants (both 68 %). Therefore, under a cross-linguistic influence account, it is not clear how the speakers’ bias in their L2 could drive the observed changes in their L1. Conversely, if we interpret this as a general cognitive effect leading to more topical interpretations of pronouns under attrition, no such issue arises.

Additionally, an account based solely on the Increased Topicality Hypothesis (either driven by cross-linguistic influence as argued by Contemori and Mossman 2024 or driven by a general cognitive effect), faces some issues. First, by itself, it would not be able to capture the increased TS bias for overt pronouns observed in Martín-Villena’s (2023) pilot study or the two experimental groups in their main study (see also Cairncross 2024 for convergent findings in online processing). Second, the Increased Biases Hypothesis can be further differentiated from the Increased Topicality alternative by considering phenomena beyond the null-subject parameter. In cases where native speakers exhibit a bias unrelated to topicality, the Increased Topicality Hypothesis would make no prediction. Conversely, the Increased Biases Hypothesis would predict a strengthening of other biases under attrition. A phenomenon that might be of interest in this regard is the attrition of relative clause attachment biases, which recent work has suggested is best captured in terms of an increased locality bias already present in the L1 (Cairncross et al. 2024).[15] Thus, although the Increased Topicality Hypothesis would avoid postulating both a strengthening and a weakening effect, it would capture less of the data and would still leave open the question of why speakers undergoing attrition should exhibit this effect.

6 Conclusions

Based on previous work, we argued that attrition may lead not only to a weakening of the TS bias for overt pronouns in languages like Italian, but also to a general strengthening of L1 biases. To assess whether we should take the proposed pattern seriously, we conducted a sentence interpretation task with globally ambiguous items. Although we did not observe a weakening effect for overt pronouns, our results confirm the strengthening effect for null pronouns in Italian. This, combined with the replicability of the previous strengthening effects in Turkish and Spanish, strongly suggests that this pattern should not be considered spurious; rather than focusing narrowly on overt pronouns, future work on attrition should seek to account for this novel strengthening effect, potentially through an approach like the Increased Biases Hypothesis sketched above.

-

Data accessibility statement: The data and R script to reproduce the reported model and graph are accessible at: https://osf.io/4fa5j/?view_only=cc1d89c43e9043449df1be0cf28162c6.

References

Bates, Douglas, Martin Mächler, Ben Bolker & Steve Walker. 2015. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software 67(1). 1–48. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v067.i01.Suche in Google Scholar

Belletti, Adriana, Elisa Bennati & Antonella Sorace. 2007. Theoretical and developmental issues in the syntax of subjects: Evidence from near-native Italian. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 25. 657–689. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-007-9026-9.Suche in Google Scholar

Birdsong, David, L. M. Gertken & Mark. Amengual. 2012. Bilingual language profile: An easy-to-use instrument to assess bilingualism. Available at: https://sites.la.utexas.edu/bilingual/.Suche in Google Scholar

Cairncross, Alex. 2024. L1 attrition in Italian: Pronominal reference and (pseudo-)relative parsing ambiguities. Cambridge: University of Cambridge Doctoral dissertation.Suche in Google Scholar

Cairncross, Alex, Margreet Vogelzang & Ianthi Tsimpli. 2024. Pseudorelatives, relatives, and L1 attrition: Resilience and vulnerability in parser biases. International Journal of Bilingualism 28(5). 1016–1032. https://doi.org/10.1177/13670069231198224.Suche in Google Scholar

Cardinaletti, Anna & Michal Starke. 1999. The typology of structural deficiency: A case study of the three classes of pronouns. In Henk van Riemsdijk (ed.), Clitics in the languages of Europe (EUROTYP 5), 145–233. Berlin & New York: De Gruyter Mouton.10.1515/9783110804010.145Suche in Google Scholar

Carminati, Maria Nella. 2002. The processing of Italian subject pronouns. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Amherst Doctoral dissertation.Suche in Google Scholar

Chamorro, Gloria, Patrick Sturt & Antonella Sorace. 2016a. Selectivity in L1 attrition: Differential object marking in Spanish near-native speakers of English. Journal of Psycholinguist Research 45. 697–715. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10936-015-9372-4.Suche in Google Scholar

Chamorro, Gloria, Antonella Sorace & Patrick Sturt. 2016b. What is the source of L1 attrition? The effect of recent L1 re-exposure on Spanish speakers under L1 attrition. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 19(3). 520–532. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1366728915000152.Suche in Google Scholar

Contemori, Carla & Elisa Di Domenico. 2021. Microvariation in the division of labor between null- and overt-subject pronouns: The case of Italian and Spanish. Applied Psycholinguistics 42(4). 997–1028. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0142716421000199.Suche in Google Scholar

Contemori, Carla & Sabrina Mossman. 2024. Pronoun interpretation in intermediate-advanced L2 English speakers: L2 to L1 cross-linguistic effects. International Journal of Bilingualism 29(4). 1050–1066. https://doi.org/10.1177/13670069241260941.Suche in Google Scholar

Di Domenico, Elisa, Ioli Baroncini & Andrea Capotorti. 2020. Null and overt subject pronouns in topic continuity and topic shift: An investigation of the narrative productions of Italian natives, Greek natives and near-native second language speakers of Italian with Greek as a first language. Glossa: A Journal of General Linguistics 5(1). https://doi.org/10.5334/gjgl.1009.Suche in Google Scholar

Filiaci, Francesca, Antonella Sorace & Manuel Carreiras. 2014. Anaphoric biases of null and overt subjects in Italian and Spanish: A cross-linguistic comparison. Language, Cognition and Neuroscience 29(7). 825–843. https://doi.org/10.1080/01690965.2013.801502.Suche in Google Scholar

Flege, James Emil. 1987. The production of “new” and “similar” phones in a foreign language: Evidence for the effect of equivalence classification. Journal of Phonetics 15(1). 47–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0095-4470(19)30537-6.Suche in Google Scholar

Gargiulo, Chiara & Joost van de Weijer. 2020. Anaphora resolution in L1 Italian in a Swedish-speaking environment before and after L1 re-immersion: A study on attrition. Lingua 233. 102746. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2019.102746.Suche in Google Scholar

Giannakou, Aretousa. 2023. Anaphora resolution and age effects in Greek-Spanish bilingualism: Evidence from first-generation immigrants, heritage speakers, and L2 speakers. Lingua 292. 103573. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2023.103573.Suche in Google Scholar

Grillo, Nino, João Costa, Bruno Fernandes & Andrea Santi. 2015. Highs and lows in English attachment. Cognition 144. 116–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2015.07.018.Suche in Google Scholar

Gürel, Ayşe. 2004. Selectivity in L2-induced L1 attrition: A psycholinguistic account. Journal of Neurolinguistics 17(1). 53–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0911-6044(03)00054-x.Suche in Google Scholar

Gürel, Ayşe & Gülsen Yılmaz. 2011. Restructuring in the L1 Turkish grammar: Effects of L2 English and L2 Dutch. Language, Interaction and Acquisition 2(2). 221–250. https://doi.org/10.1075/lia.2.2.03gur.Suche in Google Scholar

Kaiser, Elsi & John C. Trueswell. 2008. Interpreting pronouns and demonstratives in Finnish: Evidence for a form-specific approach to reference resolution. Language and Cognitive Process 23(5). 709–748. https://doi.org/10.1080/01690960701771220.Suche in Google Scholar

Kaltsa, Maria, Ianthi Tsimpli & Jason Rothman. 2015. Exploring the source of differences and similarities in L1 attrition and heritage speaker competence: Evidence from pronominal resolution. Lingua 164. 266–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2015.06.002.Suche in Google Scholar

Keating, Gregory D., Bill VanPatten & Jill Jegerski. 2011. Who was walking on the beach? Anaphora resolution in Spanish heritage speakers and adult second language learners. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 33(2). 193–221. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0272263110000732.Suche in Google Scholar

Köpke, Barbara & Dobrinka Genevska-Hanke. 2018. First language attrition and dominance: Same same or different? Frontiers in Psychology 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01963.Suche in Google Scholar

Kraš, Tihana. 2008. Anaphora resolution in near-native Italian grammars: Evidence from native speakers of Croatian. EUROSLA Yearbook 8(1). 107–134. https://doi.org/10.1075/eurosla.8.08kra.Suche in Google Scholar

Lenth, Russel V. 2022. emmeans: Estimated marginal means, aka least-squares means [Computer software manual]. Available at: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=emmeans (R package version 1.7.5).Suche in Google Scholar

Linck, Jared A., Judith F. Kroll & Gretchen Sunderman. 2009. Losing access to the native language while immersed in a second language: Evidence for the role of inhibition in second-language learning. Psychological Science 20(12). 1507–1515. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02480.x.Suche in Google Scholar

Martín-Villena, Fernando. 2023. L1 morphosyntactic attrition at the early stages: Evidence from production, interpretation, and processing of subject referring expressions in L1 Spanish-L2 English instructed and immersed bilinguals. Grenada: Universidad de Grenada Doctoral dissertation.Suche in Google Scholar

Matuschek, Hannes, Reinhold Kliegl, Shravan Vasishth, Harald Baayen & Bates Douglas. 2017. Balancing type I error and power in linear mixed models. Journal of Memory and Language 94. 305–315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jml.2017.01.001.Suche in Google Scholar

Montrul, Silvina. 2004. Subject and object expression in Spanish heritage speakers: A case of morphosyntactic convergence. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 7(2). 125–142. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1366728904001464.Suche in Google Scholar

Montrul, Silvina & Celeste Rodríguez Louro. 2006. Beyond the syntax of the Null Subject Parameter: A look at the discourse pragmatic distribution of null and overt subjects by L2 learners of Spanish. In Vincent Torrens & Linda Escobar (eds.), The acquisition of syntax in Romance languages, 401–418. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.10.1075/lald.41.19monSuche in Google Scholar

Paradis, Michel. 1993. Linguistic, psycholinguistic, and neurolinguistic aspects of “interference” in bilingual speakers: The activation threshold hypothesis. International Journal of Psycholinguistics 9(2). 133–145.Suche in Google Scholar

Paradis, Michel. 2007. L1 attrition features predicted by a neurolinguistic theory of bilingualism. In Barbara Köpke, Monika S. Schmid, Merel Keijzer & Susan Dostert (eds.), Language attrition: Theoretical perspectives, 121–134. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/sibil.33.09parSuche in Google Scholar

Paradis, Johanne & Samuel Navarro. 2003. Subject realization and crosslinguistic interference in the bilingual acquisition of Spanish and English: What is the role of the input? Journal of Child Language 30(2). 371–393. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0305000903005609.Suche in Google Scholar

R Core Team. 2022. R: A language and environment for statistical computing [Computer software manual]. Available at: https://www.R-project.org/.Suche in Google Scholar

Reinhart, Tanya. 1981. Pragmatics and linguistics: An analysis of sentence topics. Philosophica 27(1). 53–94. https://doi.org/10.21825/philosophica.82606.Suche in Google Scholar

Rizzi, Luigi. 1982. Issues in Italian syntax. Dordrecht: Foris Publications.10.1515/9783110883718Suche in Google Scholar

Rizzi, Luigi. 1986. Null objects in Italian and the theory of pro. Linguistic Inquiry 17(3). 501–557.Suche in Google Scholar

Schmid, Monika S. & Scott Jarvis. 2014. Lexical access and lexical diversity in first language attrition. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 17(4). 729–748. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1366728913000771.Suche in Google Scholar

Schmid, Monika S. & Barbara Köpke. 2017. The relevance of first language attrition to theories of bilingual development. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 7(6). 637–667. https://doi.org/10.1075/lab.17058.sch.Suche in Google Scholar

Şener, Serkan & Daiko Takahashi. 2010. Ellipsis of arguments in Japanese and Turkish. Nanzan Linguistics 6. 79–99.Suche in Google Scholar

Serratrice, Ludovica. 2007. Cross-linguistic influence in the interpretation of anaphoric and cataphoric pronouns in English–Italian bilingual children. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 10(3). 225–238. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1366728907003045.Suche in Google Scholar

Serratrice, Ludovica, Antonella Sorace & Sandra Paoli. 2004. Crosslinguistic influence at the syntax-pragmatics interface: Subjects and objects in English-Italian bilingual and monolingual acquisition. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 7(3). 183–205. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1366728904001610.Suche in Google Scholar

Sorace, Antonella. 2011. Pinning down the concept of “interface” in bilingualism. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 1(1). 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1075/lab.1.1.01sor.Suche in Google Scholar

Sorace, Antonella. 2016. Referring expressions and executive functions in bilingualism. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 6(5). 669–684. https://doi.org/10.1075/lab.15055.sor.Suche in Google Scholar

Sorace, Antonella & Francesca Filiaci. 2006. Anaphora resolution in near-native speakers of Italian. Second Language Research 22(3). 339–368. https://doi.org/10.1191/0267658306sr271oa.Suche in Google Scholar

Sorace, Antonella, Ludovica Serratrice, Francesca Filiaci & Michela Baldo. 2009. Discourse conditions on subject pronoun realization: Testing the linguistic intuitions of older bilingual children. Lingua 119(3). 460–477. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2008.09.008.Suche in Google Scholar

Tsimpli, Ianthi & Antonella Sorace. 2006. Differentiating interfaces: L2 performance in syntax-semantics and syntax discourse phenomena. In David Bamman, Tatiana Magnitskaia & Colleen Zaller (eds.), BUCLD 30: Proceedings of the 30th annual Boston University Conference on Language Development, vol. 2, 653–664. Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Tsimpli, Ianthi, Antonella Sorace, Caroline Heycock & Francesca Filiaci. 2004. First language attrition and syntactic subjects: A study of Greek and Italian near-native speakers of English. International Journal of Bilingualism 8(3). 257–277. https://doi.org/10.1177/13670069040080030601.Suche in Google Scholar

Vogelzang, Margreet, Francesca Foppolo, Maria Teresa Guasti, Hedderik van Rijn & Petra Hendriks. 2020. Reasoning about alternative forms is costly: The processing of null and overt pronouns in Italian using pupillary responses. Discourse Processes 57(2). 158–183. https://doi.org/10.1080/0163853x.2019.1591127.Suche in Google Scholar

Zehr, Jérémy & Florian Schwarz. 2018. PennController for Internet Based Experiments (IBEX) [Computer software manual]. Open Science Framework. Available at: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/MD832.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.