Abstract

Left dislocation (LD) is described as a feature of informal, spoken discourse. However, most research on LD relies on a collection of examples or on datasets with a restricted mode/formality. To understand LD use across discourse types, we investigate the frequency of LDs in a corpus of 287 participants with four narrative types: informal spoken, formal spoken, informal written, formal written. We consider the speaker characteristics of age (adolescent and adult), gender (female and male), and speaker group (English monolinguals and German, Greek, Russian, and Turkish heritage speakers). We also analyze LD characteristics (e.g., noun phrase, function) based on formality. We found that the spoken mode contained more LDs than the written one and that informal narratives had more LDs than formal ones. However, the effect of formality was modulated by speaker group: only Turkish heritage speakers produced more LDs in the informal than formal narratives, while the other groups showed no evidence of a formality effect. No evidence of age or gender effects was discovered. Lastly, participants used LDs of the same characteristics in both formalities. Thus, the study confirms previous findings on LD use across discourse types and raises the importance of including bilingualism as a speaker characteristic.

1 Left dislocations across discourse types in monolinguals and bilinguals’ English

Left dislocation (LD) in English has been discussed frequently in terms of its discourse function. Specifically, studies have focused on LD as a topic-promoting device or as a method of introducing discourse-new subjects (Prince 1984; Westbury 2016). While many studies allude to the use of LDs based on discourse types (formality, mode) or speaker characteristics (age, gender), few of the existing studies examine the use or distribution of LDs in different formalities and modes of communication (see Section 2.1.1 for a detailed discussion). Further, many of the studies make no mention of the speaker characteristic of bilingualism, which is relevant given the substantial percentage of bilinguals among English speakers – for instance, 21.7 % of US residents speak a language other than English at home (US Census Bureau 2022). Also, LDs are likely to be dynamic in bilingual speakers according to the Interface Hypothesis (Sorace 2011; Tsimpli 2014) and prior research has shown dynamicity in the use of LDs by bilingual speakers (Hervé et al. 2015; Winkle 2015). The current study uses data from adolescents and adults to investigate whether and how the use of LDs differs in informal spoken, formal spoken, informal written, and formal written narratives. We additionally compare the use of LDs across the speaker characteristics of age, gender, and bilingualism. The participants include monolingual speakers (MSs) of English and heritage speakers (HSs) of German, Greek, Russian, and Turkish living in the United States. The following section provides details on previous studies on LD, including how they differ from the current analysis, and information on HSs, including how bilingualism is a relevant speaker characteristic when examining LDs.

2 Background

2.1 Left dislocation

Throughout the literature, left dislocation[1] (LD) is described as a structure in which a constituent precedes its core clause (1). Specifically, a noun phrase occurs outside of its canonical position, to the left of the core clause or proposition. The argument position within the core clause is typically filled with a pronoun that is coreferential with the dislocated noun phrase (Gregory and Michaelis 2001; Prince 1984, 1997; Shaer and Frey 2004; Westbury 2016). Because the argument position is filled by the pronoun, the noun phrase is extra-syntactic and independent of the host sentence (Gregory and Michaelis 2001; Shaer and Frey 2004).

| My father, he’s Armenian. |

| (Prince 1997: 2) |

Three main sub-categories of LDs are described in the literature, which are distinguished by the type of coreferential element in the clause. In hanging topic LDs, the coreferential element can be a variety of different structures, including a strong or weak pronoun, an agreement morpheme, or an epithet (2a) (Anagnostopoulou 1997; Shaer and Frey 2004; Westbury 2016). Clitic LDs have a clitic pronoun in the argument position of the clause (2b) (Anagnostopoulou 1997; Westbury 2016). Contrastive LDs are similar to clitic LDs, but they have a d-pronoun, or weak pronoun, in the argument position of the clause (2c) (also called German Weak Pronoun LD) (Anagnostopoulou 1997; Frey 2005; Grohmann 2000; Shaer and Frey 2004). Notably, topicalization is not considered an LD; topicalization has a left dislocated referential expression, but there is no resumptive, coreferential pronoun in the clause (2d) (Gregory and Michaelis 2001; Prince 1984, 1997; Szűcs 2014).

| Hanging Topic LD (French) | |||||||

| Blue | et | Linda, | ils | se | lavent | les | dents. |

| blue | and | linda | they | refl | wash | the | teeth |

| ‘Blue and Linda, they are washing their teeth.’ | |||||||

| (Hervé et al. 2015: 992) | |||||||

| Clitic LD (Spanish) | |||||||

| A | sus | amigos, | Pedro | los | invitó | a | cenar. |

| acc | his | friends | pedro | cl.acc | invited.3sg | to | dine |

| ‘As for his friends, Pedro invited them to dine.’ | |||||||

| (Alexiadou 2006: 670) | |||||||

| Contrastive LD (Dutch) | |||||

| Die | man | die | ken | ik | niet. |

| that | man | that.one | know | I | not |

| ‘That man, I don’t know.’ | |||||

| (Anagnostopoulou 1997: 152) | |||||

| Topicalization (English) |

| Mary, John saw yesterday. |

| (Prince 1984: 213) |

Geluykens (1992) argues that a semantic classification of LDs is more effective than a syntactic one; in this way the superficial syntactic differences between the types of coreferential element can be ignored while the semantic similarities of LDs still allow them to be grouped. This then incorporates LDs in which the pronoun and noun phrase are linked through a partial rather than total coreferential relationship (3 and 4; also called Chinese-Style Topic Constructions) (Geluykens 1992; Westbury 2016).[2]

| Steve, his mother likes beans. |

| (Geluykens 1992: 20) |

| My first husband, we had a car then a motorcycle. |

| (Westbury 2016: 28) |

LDs – regardless of the syntactic differences – have several functions in discourse. First, LDs are widely considered a topic promoting device (5) (Geluykens 1992; Givón 1983; Gregory and Michaelis 2001; Szűcs 2014; Westbury 2016; though see Prince 1984, 1997). Second, LDs are used to introduce new, not currently salient, or unexpected referents by removing them from the dispreferred subject position (6) (Gregory and Michaelis 2001; Manetta 2007; Prince 1984, 1997; Szűcs 2014; Westbury 2016). Third, LDs are used to indicate that the dislocated element is part of a partially ordered set that is already evoked in the discourse (7) (Gregory and Michaelis 2001; Szűcs 2014). As part of a set relation, LDs link the current utterance to previous discourse (Shaer and Frey 2004). In addition, LDs can be used to clarify the referent and avoid ambiguity (8) (Ashby 1988; McLaughlin 2011). The clarification function has mostly been discussed for French data and as a function of both left and right dislocation together (the example shows a right dislocation).

| Topic Promotion |

| A: Well our house in New Mexico, it was stucco. But we had all this trim to paint and lots of it. |

| B: Yeah. |

| A: And we did basically seventy-five percent of the house and then I was afraid to do the eves and high stuff. |

| (Gregory and Michaelis 2001: 1689) |

| (Re-)Introduction |

| Once there was a king who was very wise. He was rich and was married to a beautiful queen. They had two sons. The first was tall and brooding, he spent his days in the forest hunting snails, and his mother was afraid of him. The second was short and vivacious, a bit crazy but always game. Now the king, he lived in Switzerland… |

| (Westbury 2016: 36) |

| Ordered Set |

| She had an idea for a project. She’s going to use three groups of mice. One, she’ll feed them mouse chow, just the regular stuff they make for mice. Another, she’ll feed them veggies. And the third, she’ll feed junk food. |

| (Prince 1997: 129) |

| Clarification |

| Par un bel après-midi, à Munich, on était allés, Rainer et moi, dans un endroit qui venait d’ouvrir. |

| (McLaughlin 2011: 224) |

Various other functions of LDs have also been discussed in the literature although they are not directly relevant to this paper. These include, for example, contrast, turn taking (signal beginning of speaker’s turn), filler (hesitation with no clear pragmatic motivation), epithet (information about the referent), summary (regroups series of noun phrases), acknowledgement (echoing of referent in previous speaker’s utterance), and indication of politeness (Ashby 1988; Lange 2012; McLaughlin 2011; Tizón-Couto 2015, 2016). Discourse type restricts the functions of LDs, as some are interactional and would not occur in monologue-type speech or writing.

The use of LDs can be influenced by properties of the discourse, the speaker, or the sentential subject. LDs are more common in informal spoken discourse than in any other formality or mode (Geluykens 1992; Keenan 1977). English-speaking adults produce LDs most under casual, spontaneous circumstances and rarely in planned or written discourse (Keenan 1977). More recent findings by Biber et al. (2021: 948) suggest that LDs are most common in conversation and in fictional dialogues, while they are very rare in written prose. Research on written registers aligns with this conclusion – Tizón-Couto (2015) found that in present-day English (1900–1949), LDs and other left-detached sequences are most common in drama, fiction, and sermons, that is, in written registers that aim to recreate orality. For the written texts stemming from 1840 to 1914, it has also been demonstrated that speech-purposed writing (i.e., the writing that is meant to be performed or read aloud – drama, comedy, and sermons) contained a higher frequency of LDs than speech-like writing (i.e., writing of communicative immediacy – diaries, official and private letters), with mixed writing (prose fiction and trial proceedings) falling in between (Tizón-Couto 2017; see Section 2.2 of his paper for more references on the use of LD based on orality and informality). However, it remains open if these tendencies are present in today’s English.

As for the speaker properties, two studies on the use of LDs in English in two communities in Canada found differing patterns of use of LDs based on age in the two communities. In the primarily bilingual community, there was an age-graded pattern of use of LDs, meaning that middle-aged speakers used LDs least while younger and older speakers used LDs more. In the primarily anglophone community they found that the use of LD was relatively low by all speakers, and in the process of decline (Tagliamonte and Jankowski 2019, 2023). On the other hand, two other studies found no evidence of an effect of age or gender on the use of LDs (Gregory and Michaelis 2001; Lange 2012). Speakers’ language background can also play a role in the use of LDs: bilingual speakers of Indian English have been shown to have higher proportions of LDs than speakers of other English varieties (Lange 2012; Winkle 2015).

The animacy, complexity, and information status of the sentential subject have also been discussed as predictors of LDs. Some studies argue that proper names and humans occur in LDs significantly more than groups of humans and non-human subjects (Tagliamonte and Jankowski 2019, 2023). However, Snider and Zaenen’s (2006) study on LDs in a switchboard telephone corpus found no effect of animacy on the use of LDs overall. Instead, information status was a significant predictor of LDs with mediated entities (i.e., new but inferable (Nissim et al. 2004)) being dislocated more than new and old entities. Notably, the analysis on information status used a smaller subset of data than the analysis on animacy, and when animacy was investigated in just this small subset, it was a significant predictor of LDs. Tizón-Couto (2016) also investigated animacy and information status in written LDs in English historically (1500–1914). He found that LDs predominantly contain animate referents and that the majority of dislocated elements are mediated. Lastly, several studies investigated the complexity of the dislocated noun phrase in regard to the processing load of the structures. Tizón-Couto (2016, 2017) found that the length of the dislocated noun phrase is partially determined by the processing complexity of the LD. Longer noun phrases typically occurred with punctuation marks that clarified the overall structure. Winkle (2015) investigated the frequency of simple and modified noun phrases in LDs in several varieties of English with the expectation that modified noun phrases would be more common if LDs simplify the processing of an utterance. She found that modified noun phrases occur in 9.4 %–31.9 % of LDs depending on the English variety, with L1 English varieties generally having a higher percentage of modified noun phrases (pp. 115, 235; see also Lange 2012 for similar findings).

2.1.1 Gaps in prior studies on left dislocation

Despite the apparent wealth of information on LDs, most of the studies described above relied on a collection of examples rather than a large data corpus, or it is unclear what data was used (e.g., Prince 1984, 1997; Shaer and Frey 2004; Szűcs 2014; Westbury 2016). The few studies that included more data still did not investigate the distribution of LDs based on discourse type or speaker characteristic in a systematic way (for systematic historical analyses of LDs see Tizón-Couto 2015, 2016, 2017). For example, Gregory and Michaelis (2001) examined the functional contrast of LDs and topicalization using data from a switchboard telephone corpus. These data come from only one discourse type – phone conversations among unacquainted adults – and it is unclear what formality this represents. As for speaker characteristics, the corpus included men and women of varying ages and dialect groups, and there was no evidence that any of these were significant factors in the use of LDs. Gregory and Michaelis’s (2001) study provides insight into the use of LDs, but the participants include only adults and there is no mention of bilingualism although it is likely that many of the speakers in the study could be heritage speakers (HSs), L2 speakers of other languages, or L2 speakers of English. In general, bilingual speakers should be included in studies on English to be representative of actual language use, since in the US, 21.7 % of residents speak a language other than English at home (US Census Bureau 2022). Considering the phenomenon of LD more specifically, the inclusion of bilinguals and their comparison with monolingual speakers is important since LD is likely to be dynamic in the bilingual language use due to its location at the interface of a core language area (syntax) and a non-core language area (discourse), according to the Interface Hypothesis (Sorace 2011; Tsimpli 2014). Previous research has also indicated that bilingual speakers might use LDs differently from monolinguals. For example, in a study on French-English bilingual children (ages 5;4–6;7), Hervé et al. (2015) found that the bilingual children used more LDs in English contexts than the English monolingual children who instead preferred NP + VP constructions. Similarly, Nadasdi (1995) investigated LDs[3] in the spoken French of English-French bilingual adolescents in Ontario, rather than in their English. He found that speakers with less exposure to French (i.e., more exposure to English) used LDs less often in French.

Another example of a corpus-based study is Geluykens (1992), who provides an overview of LD use, particularly their communicative function. The study examined four data types: spoken conversational, spoken non-conversational, written printed, and written unprinted. The spoken conversational data included face-to-face and telephone conversations, and the spoken non-conversational included spontaneous and prepared (but unscripted) orations. The written printed data included arts and sciences materials, excerpts from newspapers, and fiction writing, and the written unprinted data included business letters, intimate letters, and personal journals. The two types of spoken language represent more and less interactive discourse, while the two types of written language represent more and less formal writing. Thus, the study provides a foundation for understanding LD use based on formality or mode. One of the claims of the study is that LDs are most frequent in informal spoken discourse (p. 21). However, judging by the frequency results (p. 34), it is difficult to determine if LD use is formality-based, interaction-based, or perhaps both, as the formality is unclear in the given data (e.g., a telephone conversation could be either formal or informal). Additionally, the data came from male and female participants, but the age and language background of the speakers was not specified.

Furthermore, two studies examined the use of LDs in the conversational component of the International Corpus of English in several varieties of English (Lange 2012; Winkle 2015). As mentioned above, both studies indicated that speakers of Indian English use LDs more frequently than speakers of other varieties. However, these studies did not include American English, and the formality of the conversations was not strictly controlled (Winkle 2015, p. 3). In addition, similar to Gregory and Michaelis (2001), these studies do not provide insight into the use of LDs in non-conversational spoken discourse.

Concerning LD characteristics, the complexity and the animacy of the dislocated noun phrase and the functions of introducing a new referent and re-introducing a given referent have been explored in data of either only one mode or of an undefined formality. For example, Lange (2012: 169) and Winkle (2015: 110–115) investigated complexity of the NP (simple versus modified) and function of LDs in conversations of an undefined formality in several English varieties, which did not include American English. In contrast, Tizón-Couto (2016, 2017) investigated complexity of the noun phrase (length) and function in only the written mode using historical data. Animacy is another relevant factor in the use of LDs with animate referents more likely to be dislocated. Tagliamonte and Jankowski (2019, 2023) argued that subject animacy is a major predictor of LDs in spoken English in a predominantly French-English bilingual community. Similarly, Snider and Zaenen (2006) found an effect of animacy on LDs when information structure is also considered in data from a switchboard telephone corpus.

To expand on this prior work and fill some of these gaps in the literature, our study investigates the distribution of LDs across informal spoken, formal spoken, informal written, and formal written non-conversational narratives. Further, we include the speaker characteristics of age (i.e., adolescent and adult), gender (i.e., male and female), and bilingualism (i.e., English monolinguals and HSs of German, Greek, Russian, and Turkish). Lastly, we explore the functions and noun phrase characteristics (i.e., animacy, complexity, and resumptive pronoun) of LDs that occur in these modes and formalities.

2.2 The current study

The current study examines if and how the use of LDs in English differs across the following discourse types: informal spoken, formal spoken, informal written, and formal written. We additionally ask (a) whether, and how, the use of LDs is conditioned by speaker characteristics and (b) whether LDs with particular characteristics are more likely to be used in certain contexts. We approach this question in several ways.

2.2.1 Narrative and speaker characteristics

We investigate the frequency of LDs in English narratives by formality (informal and formal) and mode (spoken and written). This allows us to manipulate formality and mode without an additional variable of interactive discourse type, which will provide clarity to Geluykens’ (1992) finding that LDs are primarily a feature of informal conversation.

Further, we investigate the frequency of LDs by age (adolescent and adult) and gender (male and female). This allows us to expand the ages investigated in Gregory and Michaelis’s (2001), Lange’s (2012), and Tagliamonte and Jankowski’s (2019, 2023) studies to younger speakers and to test their finding that gender is not a significant factor in LD use. We also investigate the frequency of LD use by English monolingual and bilingual speakers, and a potential interaction of speakers’ language background, age, and gender with discourse formality.

English bilingual speakers in this study are represented by German HSs, Greek HSs, Russian HSs, and Turkish HSs speaking English as their dominant language. HSs are bilinguals who speak a heritage language at home that is not the majority language of the community (Benmamoun et al. 2013; Rothman 2009). HSs often are dominant in their heritage language at young ages, but this typically shifts during childhood such that they become dominant in the community language as adolescents and adults (Benmamoun et al. 2013). In the context of American English, we expect that many native bilingual speakers are in fact heritage speakers. Further, the choice of studying heritage speakers and monolinguals that speak the same English variety expands on previous research that compared bilinguals and monolinguals speaking different language varieties (Lange 2012; Winkle 2015).

The four HS groups were selected due to the diversity of the heritage languages (belonging to different branches of the Indo-European family and the Turkic family) and to the availability of the data. All heritage languages feature LDs that are comparable to English (see the description in Appendix A). However, Turkish LDs are the most structurally different from English – either the dislocated element has to be accompanied by a converb gelince (similar in meaning to English as for), or it has to be an object (not a subject), while the pronominal element appears in the postverbal position that is restricted to backgrounded information (Göksel and Kerslake 2005; Kornfilt 1997; Kornfilt 2011; Schroeder 1992). Based on these differences between English and Turkish, we can hypothesize that Turkish HSs would use LDs less frequently than other HSs, whose heritage languages have more similar LD structures to English. Concerning the frequency of use of LDs in the heritage languages, we could not find any concrete information in the previous literature, and, hence, did not make predictions based on this parameter.

2.2.2 LD characteristics

Finally, we perform a descriptive analysis of the characteristics of LDs used, including the animacy of the dislocated referent, the complexity of the noun phrase, the type of pronoun, and the function of the LD.

Based on previous literature, we hypothesize that the frequency of LDs will be higher in the informal than formal contexts and in the spoken than written modes (Geluykens 1992; Keenan 1977). We expect no evidence of an age and gender effect on the use of LDs (Gregory and Michaelis 2001; Lange 2012) but an effect of bilingualism on the use of LDs, as differences in LD use have been shown in other bilingual populations (Hervé et al. 2015; Nadasdi 1995).

3 Methods

3.1 Participants and data collection

Participants are five groups of English speakers living in the United States: English monolinguals and bilingual speakers of English and one of four heritage languages (German, Greek, Russian, and Turkish). The majority of HSs (91.9 %) were first exposed to English at the age of 5 or earlier, with 45.7 % having the first contact with English from birth. Monolinguals were defined as those for whom English was the only language spoken at home, with no other language exposure before age 6. HSs are those who speak English as the majority language of their community as well as a heritage language which they learned from birth from at least one parent who is an L1 speaker of the heritage language. The participants are divided into two age groups – adolescent (13–18 years) and adult (20–37 years, Table 1).

Distribution of participants.

| Group | Adolescent | Adult | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (male/female) | Mean age (SD) | N (male/female) | Mean age (SD) | |

| English MSs | 32 (13/19) | 16.1 (1.4) | 32 (13/19) | 28.5 (3.9) |

| German HSs | 27 (15/12) | 15.5 (1.5) | 7 (2/5) | 25.3 (4.1) |

| Greek HSs | 33 (16/17) | 16.3 (1.4) | 32 (13/19) | 29.1 (3.4) |

| Russian HSs | 32 (13/19) | 15.8 (1.4) | 33 (11/22) | 27.5 (3.3) |

| Turkish HSs | 32 (10/22) | 16.0 (1.6) | 27 (9/18) | 26.2 (4.1) |

Data collection followed the Language Situations methodology (Wiese 2020; Wiese et al. 2025), which elicits controlled, comparable, and quasi-naturalistic productions across formalities and modes. Participants watched a short video depicting a minor car crash and then recounted what they saw as if they were a witness to the accident. This procedure was completed in a formal context and an informal context, as well as in spoken and written modes. For the formal context, the participant recounted the video as a voice message to a police hotline and as written police report. For the informal context, the participant recounted the video as a WhatsApp voice message and a WhatsApp text message to a friend. Thus, each participant produced four narratives.

Based on these narrative data, we assessed the English proficiency of participants using speech rate (syllables per second) and two measures of lexical diversity: moving-average type-token ratio (MATTR) and measure of textual lexical diversity (MTLD; see Azar et al. 2020; Nagy and Brook 2020 for the association between speech rate and proficiency in HSs; Kyle et al. 2024 for the connection of lexical diversity and proficiency in L2 speakers). We found no difference in proficiency of the groups based on participants’ speech rates. As recommended in the literature (Zenker and Kyle 2021), we calculated MATTR and MLTD only on the narratives with at least 50 tokens – 1065 out of 1148. Contrary to the speech rate findings, Turkish HSs differ from English monolinguals in both lexical diversity measures. The other HSs groups do not differ from the monolingual speakers. Table 2 includes the three proficiency measures for each speaker group (group values and SEs predicted by linear models); for the models and data see the OSF repository at https://osf.io/ygk6m/?view_only=5c080b841a2b495aac73771bbd74dc3f, and for the spoken files that were used for the speech rate calculation, see release 0.4.0 of the Research Unit on Emerging Grammars (RUEG) corpus (Wiese et al. 2021).

Proficiency measures by speaker group.

| Group | Speech rate Predicted value (SE) |

MATTR Predicted value (SE) |

MTLD Predicted value (SE) |

|---|---|---|---|

| English MSs | 3.26 (0.052) | 0.68 (0.005) | 38.84 (0.93) |

| German HSs | 3.34 (0.071) | 0.68 (0.006) | 40.31 (1.26) |

| Greek HSs | 3.23 (0.051) | 0.67 (0.005) | 37.85 (0.91) |

| Russian HSs | 3.20 (0.051) | 0.67 (0.005) | 38.73 (0.92) |

| Turkish HSs | 3.22 (0.054) | 0.66 (0.005) | 36.07 (0.94) |

All narratives[4] were divided into communication units (CU) – a main clause plus any dependent clauses[5] (Schneider et al. 2005) using EXMARaLDA software (Schmidt and Wörner 2014). CUs served as the unit of comparison for our study, since each CU could contain a maximum of one LD. The mean length of the narratives was 12.2 CUs (with a median of 11 and a range of 2–57). An example of an informal, spoken narrative is shown in (9), including the division into CUs and further annotations. The annotated data are accessible through the OSF repository.

3.2 Annotation

We first identified all LDs in the corpus according to the definition in Section 2.1. We then annotated each LD for four features as detailed in the following paragraphs: referent, type of pronoun, type of noun phrase, and function.

3.2.1 Referent

Across all narratives, we identified a total of 19 referents that were frequently used: man, woman1, couple, family, ball, stroller, baby, woman2, dog, leash, groceries, trunk, car1, car2, car3, cars, driver1, driver2, drivers. We annotated each narrative for the presence of these 19 referents (9), determining which referents were realized as LDs.

| [Hey bud]CU [so I was uh I was just walking down the street]CU [and there was this um on one side of the street there was this couple COUPLE walking down]CU [the guy MAN had a ball BALL]CU [and the th/ the chick WOMAN1 had a carriage stroller with a baby BABY in it STROLLER I’m guessin]CU [uh and on the other side of the street was this um this lady WOMAN2 with a dog DOG]CU [and she WOMAN2 was loading groceries groceries into her car CAR3]CU [um and then down these down the street comes these two cars CARS]CU [and the guy um that had the ball MAN he MAN accidentally kicks his ball BALL across the street]CU [and then the dog DOG runs out into the street right in front of this car CAR1]CU [uh and then the lead car CAR1 stops short]CU [and this the car CAR2 right behind it rear/ rearends it CAR1 cause it CAR1 like it stops so suddenly]CU [um and then the guy with the ball MAN he MAN runs over to help this chick WOMAN2 with her groceries GROCERIES]CU [um and then I guess when he MAN’s done he MAN walks over to to check out what’s up with these drivers DRIVERS]CU [and one of them I think one of them DRIVER1 called nine one one]CU |

| (USbi07MR_isE)6 |

- 6

The speaker code in the examples includes the following information: US – country of elicitation, United States; bi/mo – bilingual/monolingual speaker; 01 – speaker number (>50 for adolescents, <50 for adults); M/F – speaker’s sex; D/G/R/T/E – HS’s heritage language (D for German, G for Greek, R for Russian, T for Turkish) or monolinguals’ L1 (English); f/i – formal/informal setting; s/w – spoken/written mode; E – language of elicitation (English).

3.2.2 Pronoun type

We identified three types of pronouns: personal, possessive, and partitive (10). We annotated each LD for pronoun type; cases with a resumptive noun were not counted as LDs.

| Personal: | A guy, he dropped a soccer ball. |

| (USbi60MD_isE) | |

| Possessive: | The person who was unloading the car, their stuff kinda rolled into the street. |

| (USmo52FE_fsE) | |

| Partitive: | The two cars, one of them rear-ended the one in front of him. (USmo58ME_fsE) |

3.2.3 Noun phrase type

Following Winkle (2015: 113–115), we categorized the noun phrases as simple or modified with modified noun phrases including a preposition, coordination, and/or a relative clause (11). We annotated each LD for noun phrase type.

| Simple: | A guy, he dropped a soccer ball. |

| (USbi60MD_isE) | |

| Modified: | And the guy with the ball, he’s like bouncing it. |

| (USbi67MG_isE) |

3.2.4 Function

We identified four functions of LDs in the data (12). “New introduction” denotes LDs that introduce new referents in the discourse. “Re-introduction” denotes LDs that re-introduce referents that are not currently salient in the discourse. “Set” denotes LDs that indicate that a referent is part of a set. Finally, “Clarification” denotes LDs that are used to clarify the narrative in some way. Although LDs are widely considered topic promoting devices, we did not consider this function because there is no clear method of determining topic in English (Prince 1984, 1997).

| New introduction: | I saw a man accidentally drop a ball in the middle of the road, |

| when a car just stopped for two seconds. The second car stopped as well, but it crashed in front of the other car. The woman who was packing her groceries in the trunk, she did not realized her dog was chasing the ball and the dog could of been hit by the car. (USmo24FE_fwE) | |

| Re-introduction: | There was this couple walking down the guy had a ball and th/ the chick had a carriage with a baby in it I’m guessing uh and on the other side of the street was this lady with a dog and she was loading groceries into her car um and then down this street comes these two cars and the guy um that had the ball he accidentally kicks his ball across the street. (USbi07MR_isE) |

| Set: | I decided to take a walk, and as I was walking, there was a little family walking, Im assuming it was the father, he was tribbling a soccer ball. (USbi73FG_iwE) |

| Clarification: | I saw this guy he was walking with his wife and his baby and he dropped his ball into the road and this dog tried to go after it and the lady across the street who was loading her car um her food fell and he tried the guy he went to go help the lady pick up her food. (USbi76FD_isE) |

When differentiating between the new-introduction and re-introduction functions, the span to determine if a referent was new or old was the full narrative. It could be argued that all of the referents are in fact mediated due to the limited referents in the original stimulus, and as such these two functions should be conflated as referent introduction. However, we felt new and old were more accurate classifications because the participants were recounting the car crash video for a hypothetical audience with no prior knowledge of it, so the referents would not be inferable to the interlocutor. Further, research has found that there is a slightly higher proportion of new referents in LDs in L1 varieties of English than in L2 varieties of English (Winkle 2015: 110).

3.3 Analysis

Our analyses fall into three broad categories – confirmatory (narrative and speaker characteristics), exploratory (interaction of speaker characteristics with formality),[7] and descriptive (LD characteristics). The data, R code, and Excel workbook that can be used to reproduce all analyses can be accessed through the OSF repository.

3.3.1 Confirmatory analysis: narrative and speaker characteristics

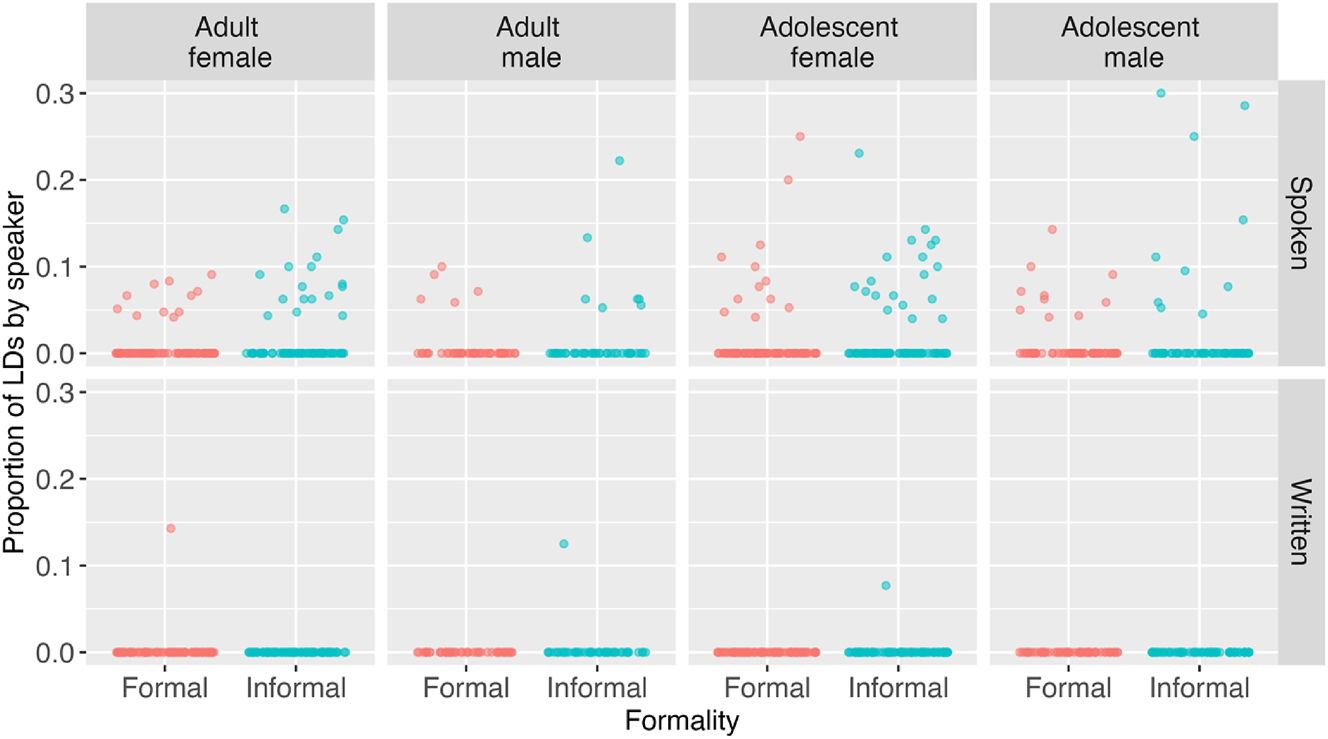

We first analyzed the data by the narrative characteristics of formality and mode and by the speaker characteristics of age and gender to see if the effect of these variables, as reported in the previous literature, manifests itself in our data. We coded each CU as containing an LD or not and then predicted the presence of LDs in CUs using generalized binomial linear mixed effects models employing the lme4 package (version 1.1-30, Bates et al. 2015) in R (R Core Team 2022). This type of modeling assumes that each CU provides exactly one chance for an LD to appear (e.g., “the man, he dropped the ball”) since more than one LD is generally not possible in a CU (e.g., “*the man, the ball, he dropped it”).[8] Table 3 (Section 4.1) shows the raw numbers of LDs and CUs that the models were based on, and Figure 1 represents the proportions of LDs used by each speaker in each narrative (formal spoken, formal written, informal spoken, informal written), with speakers split by age and gender.

By-speaker proportions of LDs out of CUs by age group and gender, split by formality and mode. Colored dots represent speakers, one dot = one speaker.

We included four predictors as fixed effects: formality (formal/informal), mode (spoken/written), age group (adult/adolescent), and gender (female/male), since these variables were explored in the literature (Geluykens 1992; Gregory and Michaelis 2001; Lange 2012; Tagliamonte and Jankowski 2019, 2023). We also included an interaction of age and gender since previous sociolinguistic research indicated that differences between men and women in the use of certain phenomena can be modulated by their age group (e.g., Labov 2001: 303–132). We did not include an interaction of formality and mode because there were only three data points in the written mode.

We used treatment contrast coding for the predictors, with formal setting, spoken mode, adult age group, and female gender as reference levels. We performed model selection as described in Gries (2021):[9] first, we maximally specified the random effect of participants by including a by-participant random intercept and mode and formality random slopes. Next, we performed a step-by-step reduction of random effects: we removed the random effect that explained the least variance and compared the model fit of the new reduced model with the model fit of the previous model using ANOVA at each step. When the random effects could not be simplified anymore (i.e., any further reduction resulted in a worse model fit), we moved on to the second step – the reduction of fixed effects using drop1() function. We removed fixed effects until the reduced model had a significantly worse fit than the previous model.

We performed several diagnostics for the final model: we calculated a marginal R squared value using the r.squaredGLMM() function from MuMIn package (Bartoń 2024) to assess how much variance in the outcome variable was described by the model. Additionally, we checked the models for multicollinearity (using the vif() function from the car package; Fox and Weisberg 2019), overfitting (with isSingular() function), and overdispersion (using a custom function overdisp.mer() from Gries 2021: 439).

3.3.2 Exploratory analysis: interaction of speaker characteristics with formality

In addition, we fit an exploratory model that included the two already-covered speaker characteristics of gender and age and added speaker group (English monolinguals/German HSs/Greek HSs/Russian HSs/Turkish HSs), which has not been investigated in previous LD studies. We also included the interactions of the three speaker characteristics with the narrative characteristic of formality, since our previous research has shown that at least some speaker groups (adolescent German HSs) can approach the formality distinction differently (Tsehaye et al. 2021); we aimed to explore this trend further.

Similar to the first analysis, all predictors were treatment contrast coded, with female gender, adult age group, English monolingual speaker group, formal setting, and spoken mode being the reference levels. We maximally specified the random effects (by-participant random intercept as well as mode and formality random slopes) and performed the same model selection procedure based on Gries (2021) as before. The same model diagnostics as in the first analysis were applied to the final model. In Section 4, we report the estimates, SEs, z- and p-values obtained from the two analyses (4.1 and 4.2).

3.3.3 Descriptive analysis: LD characteristics

Lastly, we completed a descriptive analysis of the following characteristics of LDs used in each of the two formality conditions: type of noun phrase, type of pronoun, referent, and function (details in Section 3.2). We calculated the proportion of LDs with a certain characteristic out of the total LDs produced in each formality condition. For example, we determined the number of LDs with a simple noun phrase and with a modified noun phrase out of the total LDs for each context. We also determined the frequency of LD functions based on speaker group because prior research has found differences in LD function in L1 and L2 varieties of English (Winkle 2015); although our participants are all L1 English speakers, function may be a particularly dynamic characteristic. Due to the limited number of LDs in the data, this is a descriptive analysis to assess whether there are possible differences in the LD characteristics used based on formality, which can be investigated in detail in future research.

4 Results

4.1 Confirmatory analysis: narrative and speaker characteristics

In this analysis, we examined the frequency of LDs by formality, mode, gender, and age group. We also included an interaction of age and gender. Table 3 shows the overall proportions of LDs out of CUs for the four combinations of gender and age group, split by formality and mode. Figure 1 shows individual by-speaker proportions of LDs out of CUs for each combination of gender and age group, split by formality and mode.

Raw numbers of LDs and CUs by gender and age, split by formality and mode.

| Formal spoken | Formal written | Informal spoken | Informal written | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LD | CU | LD/CU | LD | CU | LD/CU | LD | CU | LD/CU | LD | CU | LD/CU | |

| Adult female | 13 | 1,192 | 0.011 | 1 | 918 | 0.001 | 23 | 1,117 | 0.021 | 0 | 718 | 0.000 |

| Adult male | 5 | 682 | 0.007 | 0 | 474 | 0.000 | 9 | 616 | 0.015 | 1 | 400 | 0.003 |

| Adolescent female | 18 | 1,239 | 0.015 | 0 | 1,005 | 0.000 | 28 | 1,118 | 0.025 | 1 | 786 | 0.001 |

| Adolescent male | 12 | 902 | 0.013 | 0 | 669 | 0.000 | 18 | 805 | 0.022 | 0 | 505 | 0.000 |

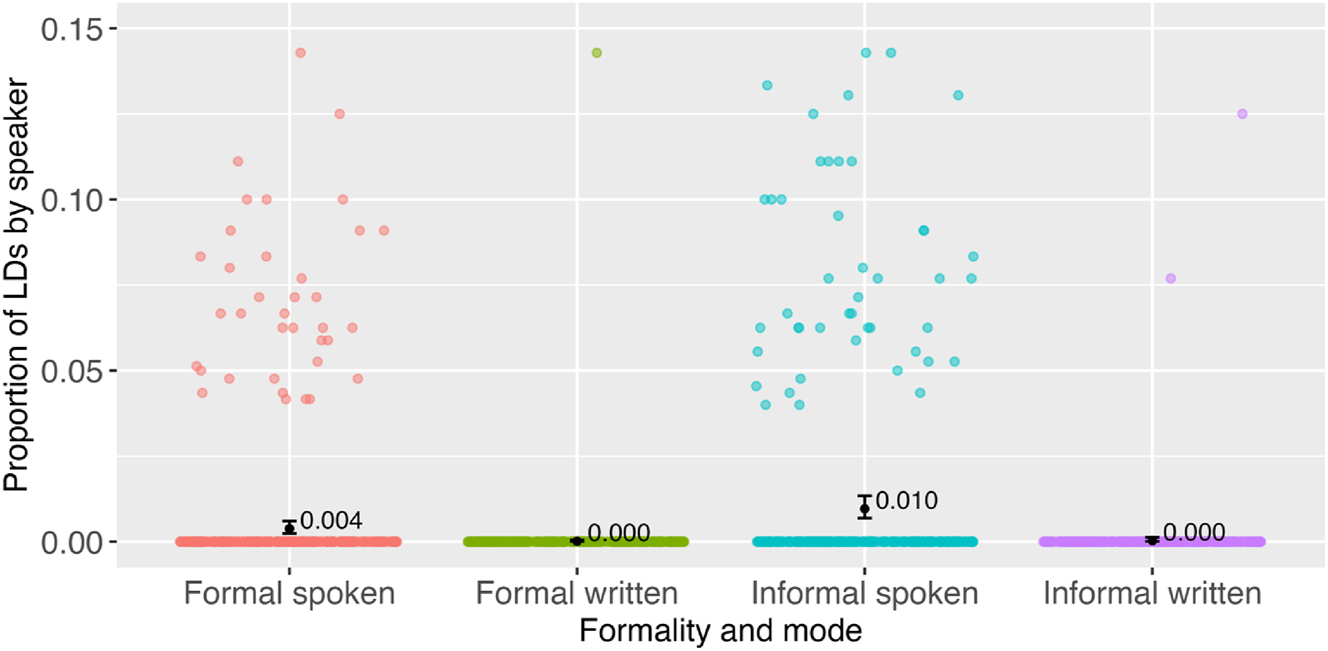

In the inferential analysis, the gender and age group predictors were dropped during the model selection, meaning that they did not significantly contribute to predicting LD use. The final model contained mode and formality as fixed effects and a formality random slope uncorrelated with a by-speaker random intercept. In this final model, we observed a strong main effect of mode (est. = −3.4129, SE = 0.6941, z = −4.917, p < 0.001), with fewer LDs in the written mode compared to the spoken mode. In addition, there was a main effect of formality (est. = 0.9293, SE = 0.2846, z = 3.266, p = 0.001), with more LDs in the informal setting than in the formal one (Figure 2). The fixed effects accounted for 35.8 % of variance in the outcome variable; no issues with multicollinearity, overfitting, or overdispersion were detected.

Predicted probabilities of LDs by formality and mode and individual proportions of LDs out of CUs. Colored dots represent speakers; black dots with whiskers represent predicted probabilities of LDs based on the linear mixed effects model. The y-axis is zoomed from the original size of 0–0.3 to the size of 0–0.15 to make the model predictions more visible. When zooming, 10 data points above the 15 % mark were removed: two in formal spoken, eight in informal spoken.

4.2 Exploratory analysis: interaction of speaker characteristics with formality

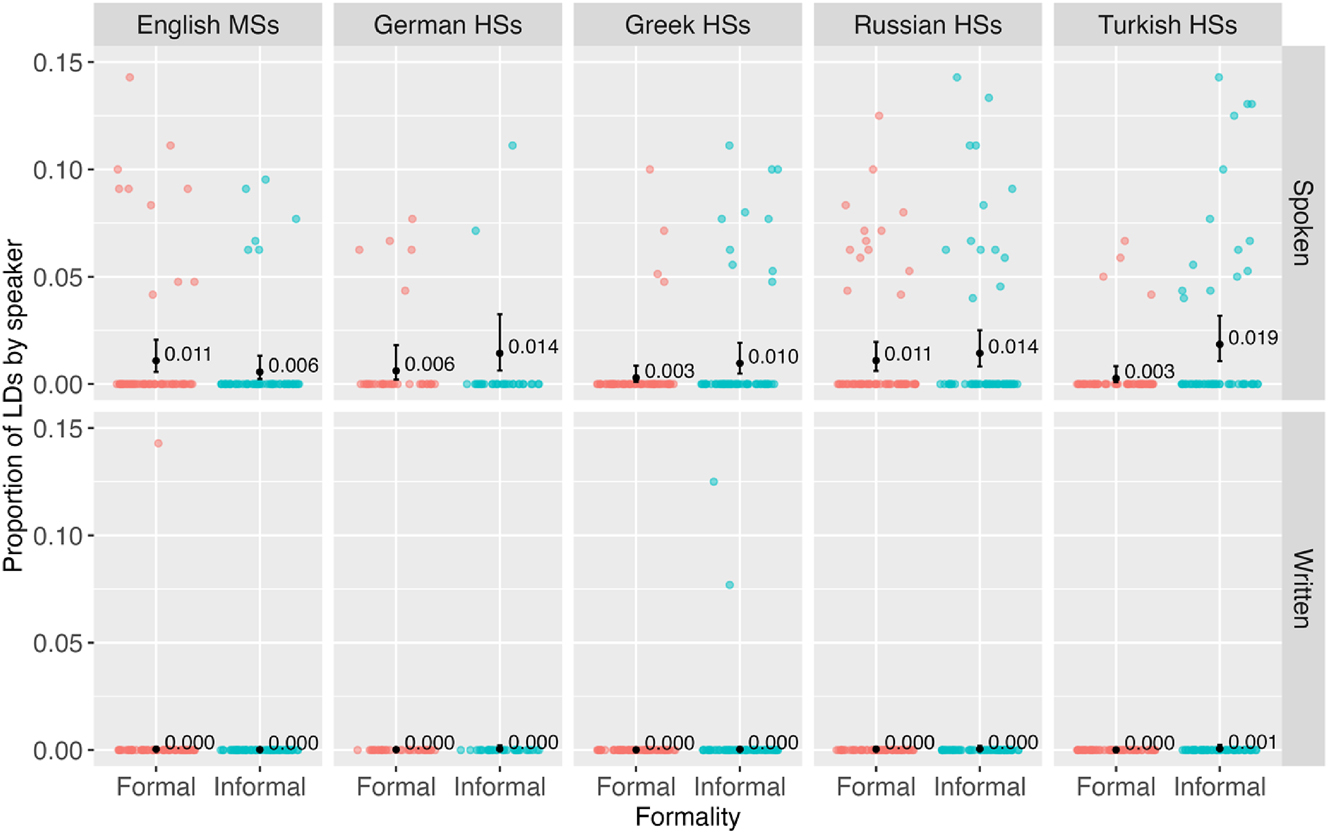

Our second analysis examined the interaction of formality with the speaker characteristics of gender, age group, and speaker group. Mode was included as a control variable. Table 4 shows the overall proportions of LDs out of CUs for the five speaker groups, split by formality and mode. Figure 3 shows the individual by-speaker proportions of LDs out of CUs by speaker group, split by formality and mode, along with the predicted probabilities of LDs based on the linear model.

Raw numbers of LDs and CUs by speaker group, split by formality and mode.

| Formal spoken | Informal spoken | Formal written | Informal written | Total | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LD | CU | LD/CU | LD | CU | LD/CU | LD | CU | LD/CU | LD | CU | LD/CU | LD | CUs | LD/CU | |

| English MSs | 15 | 834 | 0.018 | 8 | 771 | 0.010 | 1 | 615 | 0.002 | 0 | 514 | 0.000 | 24 | 2,734 | 0.009 |

| German HSs | 5 | 463 | 0.011 | 10 | 397 | 0.025 | 0 | 374 | 0.000 | 0 | 265 | 0.000 | 15 | 1,499 | 0.010 |

| Greek HSs | 5 | 903 | 0.006 | 12 | 812 | 0.015 | 0 | 661 | 0.000 | 2 | 503 | 0.004 | 19 | 2,879 | 0.007 |

| Russian HSs | 19 | 971 | 0.020 | 22 | 883 | 0.025 | 0 | 763 | 0.000 | 0 | 553 | 0.000 | 41 | 3,170 | 0.013 |

| Turkish HSs | 4 | 844 | 0.005 | 26 | 793 | 0.033 | 0 | 653 | 0.000 | 0 | 574 | 0.000 | 30 | 2,864 | 0.010 |

Predicted probabilities of LDs by speaker group, split by formality and mode and individual proportions of LDs out of CUs. Colored dots represent speakers; black dots with whiskers represent predicted probabilities of LDs based on the linear mixed effects model. The y-axis is zoomed from the original size of 0–0.3 to the size of 0–0.15 to make the model predictions more visible. When zooming, 10 data points above the 15 % mark were removed: two in English MSs, three in German HSs, two in Russian HSs, and three in Turkish HSs.

In the inferential analysis, the final model’s fixed effects included mode, formality, and speaker group, as well as an interaction of formality and speaker group. Random effects included only a by-speaker random intercept. The significant interaction of formality and speaker group indicated that the formality slope was different in Greek HSs and Turkish HSs, compared to English monolinguals (Greek HSs est. = 1.863, SE = 0.777, z = 2.396, p = 0.017; Turkish HSs est. = 2.622, SE = 0.778, z = 3.370, p < 0.001). The simple effect of formality within English monolinguals indicated no evidence of the difference between formal and informal setting in English monolinguals’ productions (est. = −0.66, SE = 0.493, z = −1.338, p = 0.18). The fixed effects accounted for 42.5 % of variance in the outcome variable; no issues with multicollinearity, overfitting, or overdispersion were detected.

To see if there is a difference between the formal and informal settings in the four HS groups, we performed pairwise comparisons using emmeans() function and custom contrasts from the emmeans package (version 1.8.9, Lenth 2023). The resulting comparisons (with Holm-adjusted p-values) indicated that Turkish HSs had a significantly lower proportion of LDs in the formal setting than the informal one (est. = −1.961, SE = 0.601, z = −3.261, p = 0.004), while the other HS groups did not make a significant distinction between the formalities.

Overall, the results of the two inferential analyses show that mode is an important predictor of LD use, with the spoken mode having more LDs than the written one, as predicted based on Geluykens (1992). Formality also plays a role – when taken as a non-interacting predictor, we observe that the informal setting has more LDs than the formal one, as predicted based on the claim by Geluykens (1992). However, our exploratory analysis indicated that the formality effect is modulated by the speaker group: it is actually Turkish HSs that make the expected distinction between the formality settings (significantly more LDs in the informal one). In contrast, English monolinguals, along with German, Greek, and Russian HSs, do not show evidence of the significant formality distinction – the speakers in our sample used similar proportions of LDs in formal and informal settings. Finally, we observed no evidence of gender and age group effects, similar to Gregory and Michaelis (2001).

4.3 Descriptive analysis: LD characteristics

Lastly, we analyzed the LD characteristics – noun phrase, pronoun, referent, and function – used by formality. The frequency of simple and modified noun phrases in LDs by formality is shown in Table 5; the frequency is represented as a proportion[10] of LDs of each type out of the total LDs used in the informal and formal contexts, as well as overall. In general, speakers mostly use modified noun phrases, and this difference is more extreme in the formal than informal context. The frequency of LDs with modified noun phrases is consistent with the idea that LDs may simplify the processing of a complex utterance or sentence (Lange 2012; Tizón-Couto 2016, 2017; Winkle 2015). However, our results show a higher frequency of modified noun phrases than Lange (2012) and Winkle (2015)’s results.

Type of noun phrase used in LD by formality.

| LDs | Simple | Modified | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Informal | 80 | 0.475 | 0.525 |

| Formal | 49 | 0.265 | 0.735 |

| Total | 129 | 0.395 | 0.605 |

The frequency of different pronoun types in LDs by formality is given in Table 6. Personal pronouns are used most frequently, followed by possessive pronouns.

Type of pronoun used in LD by formality.

| LDs | Personal | Possessive | Partitive | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Informal | 80 | 0.925 | 0.075 | 0.000 |

| Formal | 49 | 0.776 | 0.184 | 0.041 |

| Total | 129 | 0.868 | 0.116 | 0.016 |

10 of the 19 referents in the data were produced at least once using an LD, and we categorized these referents as animate (man, woman1, couple, family, woman2, driver1, and drivers) and inanimate (car1, car2, cars). Table 8 shows the proportion of LDs with animate and inanimate referents out of the total LDs for each formality. We additionally determined the frequency of these 10 animate and inanimate referents overall in the data (Table 7). Animate referents are used most frequently in LDs in both formalities. Animate referents are also used more frequently in the narratives overall; however, this difference is more exaggerated in the LDs.

Referent animacy in LD by formality.

| Proportion of (in)animate referents in LDs | Proportion of (in)animate referents in narratives. | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LDs | Animate | Inanimate | Referents | Animate | Inanimate | |

| Informal | 80 | 0.863 | 0.138 | 5,733 | 0.614 | 0.386 |

| Formal | 49 | 0.816 | 0.184 | 8,766 | 0.609 | 0.391 |

| Total | 129 | 0.845 | 0.155 | 14,499 | 0.611 | 0.389 |

This suggests that the use of a referent in an LD depends on a combination of referent animacy and overall frequency of the referent (see analysis by each referent in OSF repository), which is consistent with Tagliamonte and Jankowski’s (2019, 2023) findings that a major predictor of left dislocation in English and French is subject animacy (see also Snider and Zaenen 2006; Tizón-Couto 2016, 2017).

Lastly, the frequency of the functions of LDs by formality is provided in Table 8. LDs are used mostly to reintroduce referents and to introduce new referents in the narrative.

Function of LD by formality.

| LDs | New-intro | Re-intro | Set | Clarif. | New-intro, set | Clarif., re-intro | Re-intro, set | Clarif., set | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Informal | 80 | 0.300 | 0.425 | 0.138 | 0.038 | 0.075 | 0.013 | 0.013 | 0.000 |

| Formal | 49 | 0.286 | 0.429 | 0.143 | 0.000 | 0.041 | 0.000 | 0.082 | 0.020 |

| Total | 129 | 0.295 | 0.426 | 0.140 | 0.023 | 0.062 | 0.008 | 0.039 | 0.008 |

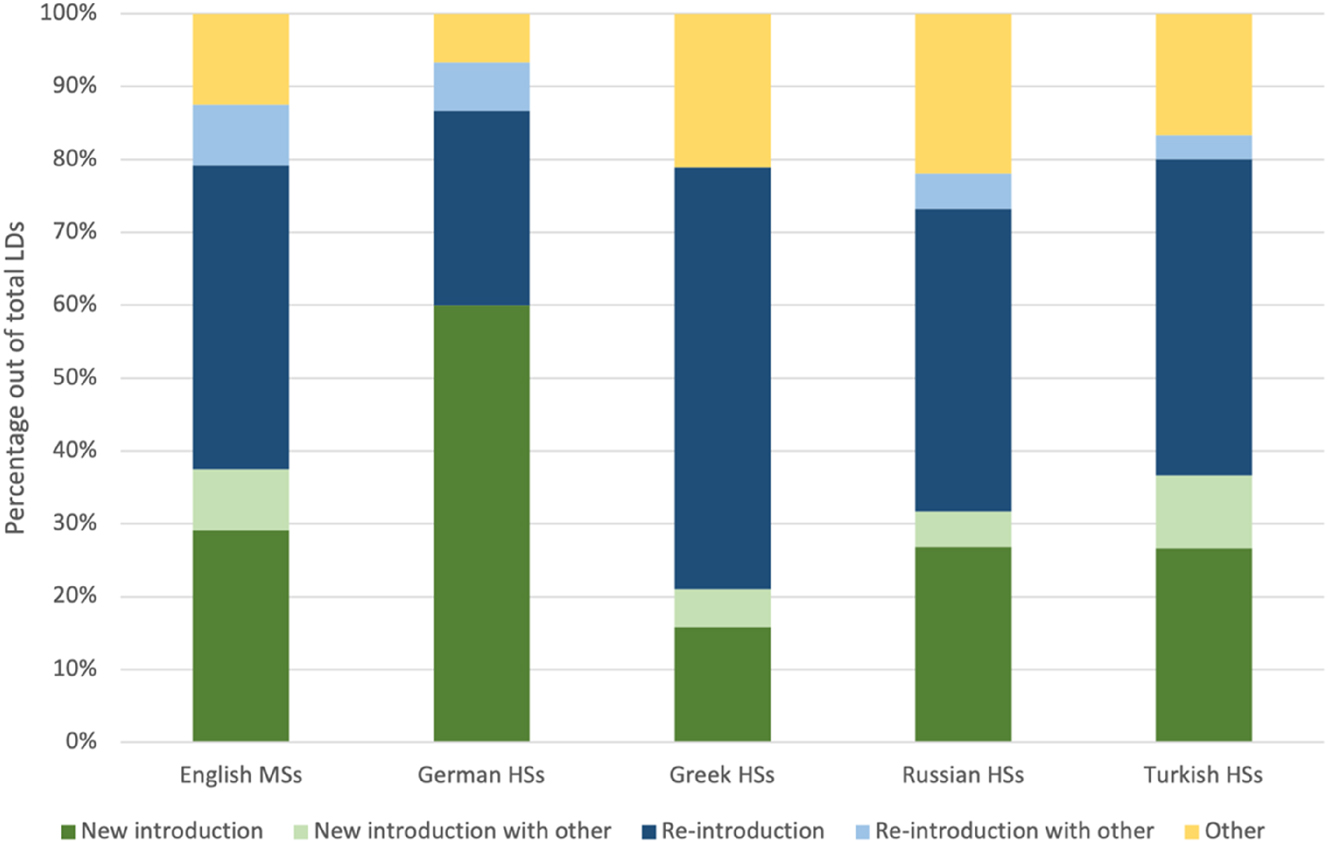

Re-introduction is the most frequent function of LDs in both formalities. While we did not explicitly investigate information status of the dislocated referents in general, this suggests that overall LDs express old information rather than new information. This contrasts with Winkle’s (2015: 110) findings that dislocated referents more frequently contain new information in L1 varieties of English, but more frequently contain old information in L2 varieties of English. In L1 varieties, 34.7 %–46.2 % of LDs have a new referent, and 37.1 %–42.1 % have an old referent. In L2 varieties, 23.1 %–30.2 % of LDs have a new referent, and 43.2 %–61.5 % have an old referent. (p. 234). Thus, our results align more closely with the results for L2 English varieties. To gain more insight into if this may be an effect of bilingualism, we compared the use of LDs by function and by speaker group, as shown in Figure 4. For this analysis, we combined the functions of clarification and set as “other,” because we did not take the referents’ information status into account for those functions.

Percentage of LDs of each function by speaker group.

German HSs are the only speakers to use more LDs with a new introduction function than with a re-introduction function. English MSs and all other HS groups use more LDs with a re-introduction function. These findings are substantially the same when additionally considering formality (see OSF repository for full analysis).

5 Discussion

We investigated the use of left dislocations in English across informal spoken, informal written, formal spoken, and formal written narratives to expand on prior research and provide clarity to the use of LDs based on formality and mode. Additionally, we investigated the use of LDs based on the speaker characteristics of age, gender, and bilingualism. Lastly, we completed an analysis on the different types of LDs used in each formality condition.

First, from the inferential analysis on narrative characteristics, we found that LDs are used significantly more in the spoken mode than in the written mode. There were only three LDs in our written data, which fit Tizón-Couto’s (2017) definition of speech-like writing. He found that LDs are more frequent in speech-purposed writing than speech-like writing in historical data, so it is possible that speech-purposed productions today would also exhibit higher rates of LDs than the present data, which could be investigated in future research. Additionally, LDs were used significantly more in the informal setting than formal setting in general, without taking the speaker group into account (but see the interaction below). This aligns with Geluykens’ (1992) finding that LDs are a phenomenon of informal conversation in English and extends it to non-conversational discourse types.

Next, we found no overall differences in LD use based on gender or age, which is consistent with Gregory and Michaelis (2001) and Lange (2012). However, through our exploratory analysis on the interaction between formality and the speaker characteristics of age, gender, and speaker group, the speaker characteristic of bilingualism was found to affect the use of LDs. We found that English monolinguals did not use LDs differently in the informal and formal settings, and the German, Greek, and Russian HSs behaved similarly to the English monolinguals. In contrast, Turkish HSs used significantly more LDs in the informal than formal setting. Numerically, English monolinguals were the only speaker group that had slightly (but not significantly) more LDs in the formal setting than in the informal setting (see Figure 2). The HS groups had the reverse pattern – more LDs in the informal than in the formal setting. However, the reversal was large enough to reach significance only for Turkish HSs, not for German, Greek, and Russian HSs. Thus, we can conclude that the formality effect is modulated by speaker group: Turkish HSs treated the formality distinction differently than the English monolinguals, while German, Greek, and Russian HSs did not.

We had predicted that Turkish HSs would use LDs less frequently than English MSs other HSs because the structure of LDs in Turkish differs more from that of English, while the other German, Greek, and Russian have LDs relatively similar in structure to that of English. We did not find an overall difference in frequency of LDs between the speaker groups, which would have supported our hypothesis. However, we did find that Turkish HSs behaved differently than the other speaker groups in terms of formality. The reason for this difference is not immediately obvious, but we propose several possibilities that should be investigated in further research. First, it is possible that cross-linguistic influence from the heritage Turkish to the majority English affects the use of LDs. Although they are structurally different, LDs in Turkish may be more frequent in informal speech than they are in English. Alternatively, extralinguistic factors such as speaker attitude and perception of the situation could cause these differences. HSs might use more formal language in the formal narratives than monolinguals to demonstrate their language skills in general. This could be due to many underlying factors, including pressure to conform to standard English, more exposure to language tests, or more frequently discussing language in general/their own language use than monolinguals. This would be consistent with Tsehaye et al.’s (2021) finding that monolingual speakers and HSs approach the formality distinction differently when using subordinate clauses, likely due to extralinguistic factors. As a reminder, all HSs reverse the formality trend compared to English monolinguals. While this is only significant for the Turkish HSs, perception of the situation may be similar for all HS groups. Additionally, the Turkish HSs had lower lexical diversity scores than all other speaker groups, which could contribute to the pressure to conform to standard English. This being said, it is not possible to make definitive conclusions regarding the cause of the different use of LDs by speaker group without further research. Future studies should examine the use of LDs by the HSs in their heritage Turkish, as well as the language of monolingual Turkish speakers to support these findings. It would further be interesting to study the use of LDs in other bilingual groups, such as late L2 learners of Turkish, to see if they show similar results.

Lastly, through our descriptive analysis of LD characteristics, we found that generally LDs in our data had a dislocated modified noun phrase, a resumptive personal pronoun, an animate referent, and a function of re-introducing that referent in both informal and formal contexts. Our results indicate that the structure of LDs is not appreciably different based on discourse type. However, these analyses additionally provide insight into some open questions in the literature or contrast with prior findings. First, the frequent use of modified noun phrases in our data suggest that our participants used LDs as a simplifying strategy by breaking an utterance down into smaller chunks (Lange 2012: 160; Winkle 2015: 113). We additionally found that the difference in frequency between simple and modified noun phrases was slightly larger in the formal than in the informal contexts. This may be because formal discourse has more complex language generally, so there is more of a need for simplification strategies. Notably, our data contained a higher proportion of modified noun phrases than Lange (2012) and Winkle (2015)’s studies. It is possible that this is related to the varieties of English under study; we only investigated LD use in American English, while Lange (2012) and Winkle (2015) studied other English varieties. Further, if this is directly related to ease of processing, it is possible that the modified noun phrases differ between these corpora; a full analysis of noun phrase length could provide clarity to the issue of LD complexity in future research (for example see Tizón-Couto 2016, 2017).

Second, we found that LDs favor animate referents. This aligns with Tagliamonte and Jankowski’s (2019, 2023) studies that animate subjects – specifically proper names and humans – are significantly more likely to occur in LDs than inanimate subjects. However, those studies investigated anglophones and francophones in a predominantly French speaking town, and as such are not directly comparable with our study. In addition, our results are consistent with Snider and Zaenen’s (2006) results, which found an effect of animacy on LDs when information status is taken into account (although the full data set without information structure annotation did not show an effect of animacy on LDs). Thus, we conclude that animacy is an important factor in LD, but further research should explore its possible interactions with speaker language background and information status in more detail.

Lastly, we found that LDs were used to re-introduce a referent more frequently than to introduce a new referent. This is somewhat surprising as Winkle (2015) found that speakers of L1 varieties of English tend to use LDs with a new referent more frequently than an old referent. Our contrasting result could be a side-effect of the data elicitation methodology; there are only so many referents available in the stimulus, so LDs with new introductions are more likely to occur only at the very beginning of narrative, while LDs with re-introductions have more available space/time to occur. However, the German HSs used LDs with a function of introducing a new referent more frequently than to re-introduce a referent, suggesting that function is not solely a side-effect of data elicitation. Further research is needed to tease out the effect of function, information status, English variety, and speaker background on LD use.

To summarize, the current study contributes to the body of work on LDs in several important ways. First, many studies claimed that LDs are a feature of informal, spoken discourse but analyzed data of only one discourse type or an unclear formality. We found a significant effect of mode and formality on the use of LDs in English from four non-conversational discourse types. Further, no studies on American English investigated the use of LDs by bilingual speakers. This was a major gap in the literature because bilingualism is frequent in the United States and LDs are dynamic in other bilinguals’ speech. In this study, we took language background into account, and we found an interaction of formality and speaker group. Specifically, LDs were distributed differently across formal and informal settings in the majority English of Turkish HSs as compared to the English monolinguals and the German HSs, Greek HSs, and Russian HSs. The underlying cause of this result (e.g., cross-linguistic influence or extralinguistic factors), as well as the use of LDs by different types of bilinguals, should be expanded on in future research.

Funding source: Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft

Award Identifier / Grant number: FOR 2537: AL 1886/2-1 & AL 1886/4-1

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all researchers who have contributed to the data collection and the development of the RUEG corpus, where the data in the current study comes from.

-

Research funding: The study was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation); the grant was awarded to the Research Unit “Emerging Grammars in Language Contact Situations” (FOR 2537), projects P2 (project no. 394837597, GZ AL 1886/2-1) and P8 (project no. 313607803, GZ AL 1886/4-1).

-

Author contribution: Tatiana Pashkova and Hannah Lee have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship.

German has LDs, specifically hanging topic LDs and contrastive LDs (Anagnostopoulou 1997; Cinque 1997; Grohmann 2000). These structures have a sentence peripheral noun phrase with a coreferential element in the core clause. The coreferential element in hanging topic LDs is typically a personal pronoun (Frey 2005), but there is a wide range of possibilities for this element (1a) (Shaer and Frey 2004). Case agreement is not required for hanging topic LDs in German (Shaer and Frey 2004). For contrastive LDs, the coreferential element is a d-pronoun, or weak pronoun, which requires case agreement in German (1b) (Frey 2005). Notably, clitic LDs are not possible in German (Anagnostopoulou 1997).

| Den/der | Hans, | jeder | mag | ihn. |

| the.acc/nom | Hans | everyone | likes | him |

| ‘Hans, everyone likes him’ | ||||

| Den | Hans den | mag | jeder. |

| the.acc | Hans him | like | everyone |

| ‘Hans, everyone likes him’ | |||

| (Shaer and Frey 2004: 466) | |||

The functions of LDs in German include marking topic, picking out a referent that is linked to already available discourse referents, or signaling a discourse break (Frey 2005).

Greek has both hanging topic LDs and clitic LDs (Anagnostopoulou 1997). Like German, the hanging topic LDs have a variety of possible resumptive elements, and they do not require case agreement (2a). Clitic LDs, conversely, must have a clitic as the resumptive element, and they require case agreement (2b) (Anagnostopoulou 1997).

| Ton petro | ton | nostalgo | ton gliko | mu/afton poli | ||

| the peter.acc | cl.acc miss | the sweet | my/him | much | ||

| zontas | makria. | |||||

| living | far.away | |||||

| ‘Peter, I miss my dear a lot living far away’ | ||||||

| Ton | petro | ton | nostalgo poli. |

| the | peter.acc | cl.acc | miss.1sg much |

| ‘I miss Peter a lot’ | |||

| (Anagnostopoulou 1997: 153) | |||

The literature has considered these topic-marking structures. However, Alexopoulou and Kolliakou’s (2002) analysis of clitic LDs found that clitic LDs are most productively used as links, meaning they pick out a subset of a previously introduced salient set, which corresponds to other researchers’ findings on the function of LDs more generally (Gregory and Michaelis 2001; Shaer and Frey 2004; Szűcs 2014).

Russian also has LDs. There are no clitics in the language, so overt differences in the structure of LDs are minimal (Polinsky and Potsdam 2014). The LDs in Russian are less restricted than in Germanic languages and can be considered instances of broadly defined XP scrambling (3) (Polinsky and Potsdam 2014; Sekerina 1997).

| Joga | mark | zanimaetssja | eju | každyj | den. |

| yoga.nom | mark.nom | practices | it.inst | every | day |

| ‘Yoga, Mark does it every day’ | |||||

| (Bailyn 2012 as cited in Polinsky and Potsdam 2014: 634) | |||||

McCoy (2003) looks broadly at subject and object doubling in Russian. This study finds that in colloquial Russian, subjects are more regularly doubled than objects. However, either the subject or object can be doubled if the other argument is contrastively focused; contrastive focus evokes membership in a set, which aligns with previously discussed functions of LDs.

Turkish allows for nouns to occur before the clause, but there is typically no coreferential pronoun (Göksel and Kerslake 2005). Some research claims that when the noun occurs before the clause there is a pronoun that is phonologically unrealized (Kornfilt 1997; Kornfilt 2011). However, LD with a realized pronoun is less frequent, and only occurs when the noun is set off from the clause with the verb gelince, which is similar in use to the English ‘as for’ (4). The use of gelince requires the dislocated noun to be in the dative case, so a pronoun is required in the canonical position to clarify the grammatical role of the noun (Göksel and Kerslake 2005; Kornfilt 1997; Schroeder 1992).

| Ali-ye | gel-ince | hasan-kendi-sin-i | on-u | ahmed-e | gönder-di. |

| ali-dat | come-when | hasan-self-3sg-acc | he-acc | ahmet-dat | send-past |

| ‘As for Ali, Hasan sent him to Ahmet’ | |||||

| (Kornfilt 1997: 201) | |||||

Schroeder (1992) also discusses object ‘clefting’ in which a topic object occurs sentence initially and is referred to again in a post-predicate position (5).

| Cenazeler nasıl kaldırılıyor? | |

| cenaze-ler nasıl | kaldır-ıl-ıyor |

| funeral-pl how | lift-pass-prs.cont |

| ‘How are funerals organized’ | |

| Cenazeler… yani basta ustalar yapar onu. | |||

| cenaze-ler yani başta | usta-lar | yap-ar | o-nu |

| funeral-pl well mainly | master-pl | do-prs | they-acc |

| ‘The funerals…well, it’s mainly the masters who do them’ | |||

| (Schroeder 1992: 156) | |||

This structure is an example of left dislocation in Turkish, and it is used to reintroduce a referent in the discourse or to shift the discourse topic (Schroeder 1992).

References

Alexiadou, Artemis. 2006. Left dislocation (including CLLD). In Martin Everaert & Henk van Riemsdijk (eds.), Blackwells companion to syntax, vol. 2, 669–699. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.10.1002/9780470996591.ch37Suche in Google Scholar

Alexopoulou, Theodora & Dimitra Kolliakou. 2002. On linkhood, topicalization, and clitic left dislocation. Linguistics 38. 193–245. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0022226702001445.Suche in Google Scholar

Anagnostopoulou, Elena. 1997. Clitic left dislocation and contrastive left dislocation. In Elena Anagnostopoulou, Hank van Riemsijk & Zwarts Frans (eds.), Materials on left dislocation, 152–192. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.10.1075/la.14.11anaSuche in Google Scholar

Ashby, William. 1988. The syntax, pragmatics and sociolinguistics of left- and right-dislocations in French. Lingua 75. 203–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/0024-3841(88)90032-0.Suche in Google Scholar

Azar, Zeynep, Alsı Özyürek & Ad Backus. 2020. Turkish-Dutch bilinguals maintain language-specific reference tracking strategies in elicited narratives. International Journal of Bilingualism 24(2). 376–409. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367006919838375.Suche in Google Scholar

Bailyn, John Frederick. 2012. The syntax of Russian. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Bartoń, Kamil. 2024. MuMIn: Multi-model inference. R package version 1.48.4. Available at: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=MuMIn.Suche in Google Scholar

Bates, Douglas, Martin Mächler, Ben Bolker & Steve Walker. 2015. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software 67(1). 1–48. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v067.i01.Suche in Google Scholar

Benmamoun, Elabbas, Silvina Montrul & Maria Polinsky. 2013. Heritage languages and their speakers: Opportunities and challenges for linguistics. Theoretical Linguistics 39(3-4). 129–181. https://doi.org/10.1515/tl-2013-0009.Suche in Google Scholar

Biber, Douglas, Stig Johansson, Geoffrey N. Leech, Susan Conrad & Edward Finegan. 2021. Grammar of spoken and written English. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.10.1075/z.232Suche in Google Scholar

Cinque, Guglielmo. 1997. ‘Topic’ constructions in some European languages and ‘connectedness’. In Elena Anagnostopoulou, Hank van Riemsijk & Zwarts F. Frans (eds.), Materials on left dislocation, 93–118. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.10.1075/la.14.08cinSuche in Google Scholar

Fox, John & Sanford Weisberg. 2019. An R companion to applied regression, 3rd edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.Suche in Google Scholar

Frey, Werner. 2005. Pragmatic properties of certain English and German left peripheral constructions. Linguistics 43(1). 89–129. https://doi.org/10.1515/ling.2005.43.1.89.Suche in Google Scholar

Geluykens, Ronald. 1992. From discourse process to grammatical construction: On left dislocation in English. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.10.1075/sidag.1Suche in Google Scholar

Givón, Talmy. 1983. Topic continuity in discourse: A quantitative crosslanguage study. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.10.1075/tsl.3Suche in Google Scholar

Göksel, Aslı & Celia Kerslake. 2005. Turkish: A comprehensive grammar. London, New York: Routledge (Routledge Comprehensive Grammars).10.4324/9780203340769Suche in Google Scholar

Gregory, Michelle & Laura Michaelis. 2001. Topicalization and left-dislocation: A functional opposition revisited. Journal of Pragmatics 33. 1665–1706. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0378-2166(00)00063-1.Suche in Google Scholar

Gries, Stefan Th. 2021. Statistics for linguistics with R: A practical introduction. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.10.1515/9783110718256Suche in Google Scholar

Grohmann, Kleanthes K. 2000. A movement approach to contrastive left dislocation. Rivista di Grammatica Generativa 25. 3–65.Suche in Google Scholar

Hervé, Coralie, Ludovica Serratrice & Martin Corley. 2015. Dislocations in French-English bilingual children: An elicitation study. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 19(5). 987–1000. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1366728915000401.Suche in Google Scholar

Keenan, Elinor O. 1977. Why look at planned and unplanned discourse. In Elinor O. Keenan & Tina Bennett (eds.), Discourse across time and space. Southern California Papers in Linguistics. No. 5, 1–42. Los Angeles University of Southern California.Suche in Google Scholar

Kornfilt, Jaklin. 1997. Turkish. London: Routledge (Descriptive Grammars).Suche in Google Scholar

Kornfilt, Jaklin. 2011. The sentential subject constraint/CED as a left-dislocation constraint in Turkish. In A. Simpson (ed.), Proceedings of WAFL 7, 203–220. Cambridge, MA: MITWPL.Suche in Google Scholar

Kyle, Kristopher, Hakyung Sung, Masaki Eguchi & Fred Zenker. 2024. Evaluating evidence for the reliability and validity of lexical diversity indices in L2 oral task responses. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 46(1). 278–299. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263123000402.Suche in Google Scholar

Labov, William. 2001. Principles of linguistic change, volume 2: Social factors. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.Suche in Google Scholar

Lange, Claudia. 2012. The syntax of spoken Indian English, vol. G45. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.Suche in Google Scholar

Lenth, Russell V. 2023. emmeans: Estimated marginal means, aka least-squares means. R Package Version 1.8.9. Available at: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=emmeans.Suche in Google Scholar

Manetta, Emily. 2007. Unexpected left dislocation: An English corpus study. Journal of Pragmatics 39. 1029–1035. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2007.01.003.Suche in Google Scholar

McCoy, Svetlana. 2003. Pronoun doubling and quantification in colloquial Russian. Journal of Slavic Linguistics 11(1). 141–159.Suche in Google Scholar

McLaughlin, Mairi. 2011. When written is spoken: Dislocation and the oral code. French Language Studies 21(2). 209–229. https://doi.org/10.1017/S095926951000030X.Suche in Google Scholar

Nadasdi, Terry. 1995. Subject NP doubling, matching, and minority French. Language Variation and Change 7(1). 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954394500000879.Suche in Google Scholar

Nagy, Naomi & Marisa Brook. 2020. Constraints on speech rate: A heritage-language perspective. International Journal of Bilingualism 28(6). 1115–1134. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367006920920935.Suche in Google Scholar

Nissim, Malvina, Shipra Dingare, Jean Carletta & Mark Steedman. 2004. An annotation scheme for information status in dialogue. In Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC’04). Lisbon, Portugal: European Language Resources Association (ELRA).Suche in Google Scholar

Polinsky, Maria & Eric Potsdam. 2014. Left edge topics in Russian and the processing of anaphoric dependencies. Journal Linguistics 50(3). 627–669. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022226714000188.Suche in Google Scholar

Prince, Ellen. 1984. Topicalization and left-dislocation: A functional analysis. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 433. 213–225. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.1984.tb14769.x.Suche in Google Scholar

Prince, Ellen. 1997. On the functions of left-dislocation in English discourse. In Akio Kamio (ed.), Directions in functional linguistics, 117–143. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.10.1075/slcs.36.08priSuche in Google Scholar

R Core Team. 2022. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available at: https://www.R-project.org/.Suche in Google Scholar

Rothman, Jason. 2009. Understanding the nature and outcomes of early bilingualism: Romance languages as heritage languages. International Journal of Bilingualism 13(2). 155–163. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367006909339814.Suche in Google Scholar

Schmidt, Thomas & Kai Wörner. 2014. EXMARaLDA. In Jacques Durand, Ulrike Gut & Gjert Kristoffersen (eds.), The Oxford handbook of corpus phonology, 402–419. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Schneider, Phyllis, Rita V. Dubé & Denyse Hayward. 2005. The Edmonton narrative norms instrument. Available at: http://www.rehabresearch.ualberta.ca/enni.10.1037/t75173-000Suche in Google Scholar

Schroeder, Christoph. 1992. Topics in Turkish: A few impressions and examples. In Giuliano Bernini & Davide Ricca (eds.), Topics. EUROTYP Working Papers, I/2, May, 151–175. (Theme Group 1: Pragmatic Organization of Discourse.) (Strasbourg).Suche in Google Scholar

Sekerina, Irina. 1997. The syntax and processing of scrambling constructions in Russian (unpublished doctoral dissertation).Suche in Google Scholar

Shaer, Benjamin & Werner Frey. 2004. ‘Integrated’ and ‘non-integrated’ left-peripheral elements in German and English. Proceedings of the Dislocated Elements Workshop 35(2). 465–502. https://doi.org/10.21248/zaspil.35.2004.238.Suche in Google Scholar

Snider, Neal & Annie Zaenen. 2006. Animacy and syntactic structure: Fronted NPs in English. Intelligent Linguistic Architectures: Variations on Themes by Ronald M. Kaplan. Stanford: CSLI Publications.Suche in Google Scholar

Sorace, Antonella. 2011. Pinning down the concept of “interface” in bilingualism. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 1(1). 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1075/lab.1.1.01sor.Suche in Google Scholar

Szűcs, Péter. 2014. On English topicalization and left-dislocation from an information-structural perspective. In Surányi, Balázs & Turi, Gergő (eds.), Proceedings of the Third Central European Conference in Linguistics for Postgraduate Students 114–127. Budapest: Pázmány Péter Catholic University.Suche in Google Scholar

Tagliamonte, Sali A. & Bridget L. Jankowski. 2019. Grammatical convergence or microvariation? Subject doubling in English in a French dominant town. Proceedings of the Linguistic Society of America 4. 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3765/plsa.v4i1.4514.Suche in Google Scholar

Tagliamonte, Sali A. & Bridget L. Jankowski. 2023. Subject dislocation in Ontario English: Insights from sociolinguistic typology. Language Variation and Change 35. 299–324. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954394523000236.Suche in Google Scholar

Tizón-Couto, David. 2015. A corpus-based account of left-detached items in the recent history of English. English Text Construction 8(1). 21–64. https://doi.org/10.1075/etc.8.1.02tiz.Suche in Google Scholar

Tizón-Couto, David. 2016. Left-dislocated strings in Modern English epistolary prose. In Gunther Kaltenböck, E. Keizer & A. Lohmann (eds.), Outside the clause: Form and function of extra-clausal constituents, 203–240. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.10.1075/slcs.178.08tizSuche in Google Scholar

Tizón-Couto, David. 2017. Exploring the Left Dislocation construction by means of multiple linear regression. Belgian Journal of Linguistics 31. 301–327. https://doi.org/10.1075/bjl.00012.tiz.Suche in Google Scholar

Tizón-Couto, David & David Lorenz. 2021. Variables are valuable: Making a case for deductive modeling. Linguistics 59(5). 1279–1309. https://doi.org/10.1515/ling-2019-0050.Suche in Google Scholar

Tsehaye, Wintai, Tatiana Pashkova, Rosemarie Tracy & Shanley E. M. Allen. 2021. Deconstructing the native speaker: Further evidence from heritage speaker for why this horse should be dead!. Frontiers in Psychology 12. 717352. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.717352.Suche in Google Scholar