Abstract

COVID-19 affected libraries and accelerated online library services. Technology, disinformation, and fake news, along with shrinking budgets created additional challenges. Embracing knowledge management (KM) can be one of the ways through which libraries can survive, but also innovate, grow, and thrive. Through an open-ended survey of 109 librarians from 21 countries, this study investigated library challenges and perceptions of librarians on whether KM can help mitigate some of these challenges. The study found that libraries continue to face a myriad of challenges, many linked to budget constraints. More than half of the participants had heard of KM before and indicated having a knowledge sharing culture, top management support, and technology infrastructure for knowledge sharing. About 40 % said they did not have KM practices. Most felt that adopting KM should be helpful to the library. The proposed model of perceived helpfulness of KM should enable KM mechanisms for the library.

1 Introduction

Ever-increasing digitization, the recent COVID-19 pandemic, and decreasing budgets have brought enormous challenges for libraries worldwide. All these challenges have put the library’s importance and long-term existence at risk. Some of the challenges confronting libraries today include addressing the diverse needs of users with limited resources, staying updated with the technological advancements, navigating ethical dilemmas, and ensuring ongoing professional development for staff. Cox (2023) discussed how libraries are losing importance within organizations e.g. in companies or universities, so they’re getting fewer resources and less control. Libraries are also struggling to find their role in the digital age as technology changes quickly. Political, economic, social, and technological changes outside of the organization make it harder for libraries to operate. Many of the challenges pertain to the COVID-19 pandemic (Ashiq et al. 2022), disinformation and fake news (Tripodi et al. 2023; Sullivan 2019), technologies such as search engines, smartphones, social media, and artificial intelligence (Ojobor 2023; Mohammed et al. 2022), and budget constraints (Green 2022; Hall and Duggins 2021). We discuss each of these challenges in greater length in the next section.

So, what can be done about the library challenges? Here’s where knowledge management can help. Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995) defined knowledge management (KM) as the capacity of an organization to generate new knowledge, distribute it across the entirety of the company, and integrate it into products, services, and systems. Dalkir (2017) described it as a systematic process of identifying, capturing, organizing, accessing, and sharing knowledge within an organization to facilitate effective decision-making, problem-solving, innovation, and overall organizational performance. KM is traditionally used in business settings. However, this research is focused on KM in the context of libraries, which can help the library increase efficiency and bring about innovation in services (Islam et al. 2015, 2017). While bringing about efficiency and innovation, KM is a very effective mechanism for libraries to help addresses many of the challenges that they face today. The positive role of KM for libraries has been found in several studies (e.g. Malaysia 2012; Islam et al. 2015, 2017; Agarwal and Islam 2014, 2015; Xiao 2020; Ratkanthiwar et al. 2024).

1.1 Research Questions

The primary purpose of this study is to explore why libraries are struggling to survive in the post-COVID-19 world and how KM can help alleviate some of its challenges.

The research questions are:

RQ1: What are the areas of challenges faced by libraries?

RQ2: How do librarians perceive the role of KM in helping mitigate these challenges?

We use three studies as a theoretical lens to guide our data gathering and analysis: Ashiq et al. (2022) for RQ1, and Agarwal and Marouf (2016) and Marouf and Agarwal (2016) for RQ2.

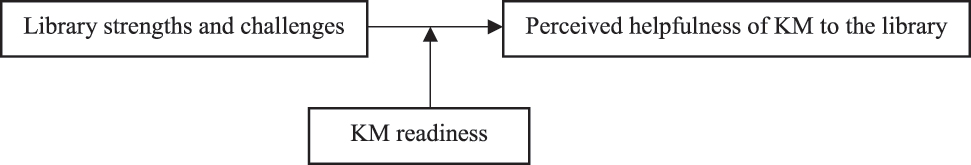

1.2 Research Model

To address the research questions, we first need to determine what the specific challenges are that libraries face today – whether it be COVID, disinformation, budget cuts, or technology/AI, and what are their strengths in the face of these challenges. We propose that if a library is ready for KM implementation (through a knowledge sharing culture, decentralized structure, organizational support, top management support, technology infrastructure, etc. – see Agarwal and Marouf 2016; Marouf and Agarwal 2016), then it is more likely to perceive KM to be helpful to the library in meeting the specific challenges that it faces.

In Figure 1, we propose a model for the perceived helpfulness of KM to the library to overcome its challenges. This model serves as a guide for our literature review and data collection and analysis, while helping to structure our paper. By identifying what is going well and not so well in the library, what opportunities and threats does it have, and assessing the existing KM practices and infrastructure in the library, a determination can be made whether KM is seen to be helpful or not. This would lead to the dependent variable, “perceived helpfulness of KM to the library,” in the model. Here, KM readiness serves as a moderator and determines the degree to which library challenges can be overcome by adopting KM.

Perceived helpfulness of KM to the library to overcome its challenges.

2 Literature Review

ExLibris (2022) outlines three trends that are shaping the future of libraries. First, the shift to digital services and delivery models is enhancing access but creating the need for licensing agreements, lending policies, and ways to digitize their existing collections. Second, patron expectations are rising. This makes libraries look for ways to make it easier for patrons to find materials that match their needs, in whatever format or device they are using. Third, budgetary pressures are forcing libraries to look for ways to automate and to streamline workflows. Let us delve deeper into the specific challenges that libraries face today.

2.1 Challenges Facing Libraries

Several articles have discussed the significant challenges faced by libraries – in academic, public, and other settings. We summarize below the challenges in the last few years brought out by the COVID-19 pandemic, disinformation and fake news, technology, and budget cuts.

2.1.1 COVID-19 Pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic induced anxiety and stress among the general population, impacting libraries and their users (Kosciejew 2021; Obenauf 2021). Smith (2019) discussed various challenges faced by the public, which impacted public libraries. These include reduced trust in government, disbelief towards reliable information, decreased community engagement and civility, a shrinking middle class, resistance to taxes, shorter attention spans, declining reading habits, lack of diversity, insufficient recognition, and obstacles in library education. The necessity of implementing social distancing measures and ensuring public safety during Covid led to temporary closures or restricted access to library facilities. This affected vulnerable populations who relied on public libraries for internet access, educational support, and social interaction (Guernsey et al. 2021). Sheikh et al. (2023) conducted a bibliometric analysis of COVID-19 related literature published in the Library and Information Science journals. The themes and keywords they identified in the literature touched upon the challenges brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic and how libraries responded to them. For example, in the theme, “library management,” and sub-theme, “managerial challenges and strategy,” some of the keywords are lockdown, impact, distribution, crisis, business continuity, and sustainability.

Similarly, they identified other themes in the areas of library services, education in libraries, library technology, and the wider impact on the information society, ranging from social media communication to helping bridge the digital divide to tackling Covid-related misinformation. Rivera-Macias and Casselden (2024) investigated the challenges experienced by different types of libraries in the Helsinki metropolitan area of Finland by asking library staff to reflect on the digital literacy services that they offered during the pandemic. The library staff found it hard to reach library patrons requiring digital support. They also highlighted the impact of teleworking, technology use, and the social aspects of working from home.

Ashiq et al. (2022) summarized seventeen studies on how libraries encountered challenges during the pandemic. These challenges, summarized in Table 1, encompass human and infrastructural issues, workplace anxiety and stress, impact of the infodemic and changes in information-seeking behavior, and leadership and planning concerns. We use Ashiq et al. (2022) as a theoretical lens to guide the library challenges aspect of our study.

Challenges faced by libraries during COVID-19 (Ashiq et al. 2022).

| Absence of pandemic plans, lack of mindset and training from work at home, lack of resources, equipment and infrastructure for online working (Harris 2021) |

| Apathy towards libraries and librarians, inadequate funding, poor technological infrastructure, lack of skilled personnel (Ifijeh and Yusuf 2020) |

| Confusion while decision making, policy change, library accessibility, changing information seeking behavior of library users, poor digital collection and repositories, users lacking digital literacy skills (Rafiq et al. 2021) |

| Connectivity issues, planning and policy issues, technology frustrations and failures, communication and engagement challenges (Gotschall et al. 2021) |

| Digital divide, job insecurity, chronic scarcity of funds, outsourcing, lack of professionally trained staff, lack of legislation and policies, copyright issues for digitization (Tammaro 2020) |

| Digital divide, poor ICT infrastructure, lack of funds, lack of information and digital skills, non-availability of proper workspaces at homes, human and infrastructural resources, infodemic, users’ poor digital skills, access management, copyright issues (Ameen 2021) |

| Fear of the pandemic, closure of the libraries, restriction on book borrowing (Fasae et al. 2021) |

| Infodemic, social media, anxiety, changing information world (Cox and Brewster 2020; Naeem and Bhatti 2020) |

| Instability of internet networks, service limitation in working hours, managing budget during the new normal (Koos et al. 2021; Mbambo-Thata 2021; Winata et al. 2021) |

| Lack of qualified library staff, Scarcity of e-resources, internet issues, insufficient amount of print materials digitized, copyright hinders the digitization of textbooks (Bashorun et al. 2021; Zhou 2022) |

| Lack of social media strategy, staffing issues, managing multiple platforms, managing trolling or tensions (Koulouris et al. 2020) |

| Lack of visionary leadership, users varying information behavior, human resource challenges, monetary challenges, rapid technological development (Ashiq et al. 2021) |

| Library staff anxiety, lack of required infrastructure when working from home, lack of training and preparedness, negative emotional feelings (such as isolation, anxiety, uncertainty and stress (Mehta and Wang 2020) |

| Policies, procedural, financial, and infrastructural challenges, lack of teleworking culture (Chigwada 2020) |

| Secure connectivity challenges, social distancing culturally challenging, limited mentorship/consultations, poor technology and infrastructure, infodemic/misinformation rise, IT knowledge and skills gaps (Ocholla 2021) |

| Uncertainty, staff management issues (Obenauf 2021; Temiz and Salelkar 2020) |

| Workplace anxieties and stress, fake news, disruption and difficulty (Guo et al. 2021; Kosciejew 2021) |

Casselden and Paxton (2024) talk about how previous behavior patterns were interrupted during the COVID-19 pandemic, with changes in the use of public library resources and greater use of digital resources. In a mixed methods study, they investigated the views of public librarians on the provision and promotion of audiobooks in public libraries in England and Wales during the pandemic. They recommended ways in which audio books can be used and promoted better through social media.

2.1.2 Disinformation and Fake News

Libraries undergo a vetting process that online sources may lack. This vetting process is crucial and libraries play a key role in ensuring the validity of research. They do so by gathering trustworthy information in their collections, which could typically be peer-reviewed or verified in other ways (Mudditt 2015; Shannon and Bossaller 2015). The proliferation of social media has led to a vast amount of information being disseminated without rigorous vetting processes. Making it difficult for libraries to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the sources they provide. With over 62.3 % of the global population engaging with social media platforms, spending an average of 2 h and 23 min per day browsing and posting content, the validity of online information has become difficult to monitor (Chaffey 2024). Sullivan (2019) argues why librarians cannot fight fake news as they address the crisis without looking at its deeper issues, whereby librarians may see misinformation as something concerning students, audiences, the public, even educated people, or “others without the skills that supposedly inoculate librarians against fake news” (97). “Absent an understanding of our all-too-human vulnerability to misinformation, librarians risk characterizing the problem as somehow outside of themselves” (97). Librarians hesitate to take a frontline stance against politicized misinformation due to concerns about neutrality and to avoid political entanglements (Tripodi et al. 2023). Apart from the traditional services offered by libraries, libraries now provide digital literacy training programs and services to the user community which requires more effort. Through interviews and workshop discussions of public library staff from Washington State in the U.S., Young et al. (2021) suggest three areas in which researchers can support public libraries in helping to combat disinformation: 1) designing effective programming; 2) developing tools that help librarians keep up-to-date on relevant misinformation; and 3) intervening in the political and economic contexts that hamper the freedom of librarians to engage in controversial topics.

2.1.3 Technology

Technology has challenged libraries for a few decades now, with easy access to resources, discovery searching facilities, and Google Books search initiatives (MacColl 2006). Google, smartphones, blockchain, AI and other cutting-edge technologies compete for people’s attention and make it challenging for libraries to engage the user with its services, with a constant need for updates, new software, and collaboration with tech providers. Digital libraries have big starting costs and ongoing maintenance expenses for libraries. Librarians need to find new ways to secure funding and deal with copyright, licenses, and other formalities, which are more difficult than dealing with print materials (IFLA 2024). Technology helps librarians with websites and databases but also challenges them often due to lack of skills, infrastructural support, funding and awareness (Mohammed et al. 2022). Ojobor (2023) discusses how new technology such as blockchain can help libraries, but many libraries grapple with lack of enough money, electricity that doesn’t work all the time, bad internet, and not having enough skilled people to use the technology. The integration of modern technology into library operations and services, along with the escalating demands and expectations of users, necessitates comprehensive training. All these present different types of challenges for libraries.

2.1.4 Budget Cuts

The COVID-19 pandemic deeply affected library budgets, especially staffing, acquisition of materials, and library consortia services (Frederick et al. 2020; Green 2022; Johnson 2020; Machovec 2020). In a survey of 638 library directors, McKenzie (2020) found 75 % of them working with smaller budgets, which were cut by 1–9 % in 2020–21. In their study of 327 library employees in Kentucky, Hall and Duggins (2021) found that about 32.74 % of academic library staff postponed medical care due to pandemic-related budget concerns. This financial strain forced libraries to make tough decisions, including reducing staff, scaling back on acquisitions, and postponing infrastructure upgrades and new services. There is significant uncertainty about the financial recovery of libraries in the long run due to budget cuts made during the pandemic. Budget cuts create significant obstacles for libraries in their mission of providing information, education, and services to their users.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many countries enforced partial or complete shutdown of libraries, identifying them as non-essential services. In their study, Frederick and Wolff-Eisenberg (2020) found that libraries had to invest more in digital tools, quickly switch to remote support, and face budget cuts. This situation was particularly challenging for developing economies, where libraries often rely on government funding or support from parent institutions, both of which faced economic downturns (Salubi 2023). After a SWOT analysis of strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats faced by libraries, particularly post-pandemic, Salubi (2023) identified budgetary constraints as a weakness and threat that libraries are facing and are likely to continue to face.

2.1.5 Strengths and Opportunities for Libraries

However, the Covid pandemic also brings innovative services and practices worldwide for libraries to continue serving their communities. Library staff at the Open University of Sri Lanka used remote work periods during the pandemic to expand their collections of open educational resources and to improve access to these for students and faculty (Abeysekera et al. 2020).

During lockdown, Chinese libraries quickly adapted to digital services to promote reading (Xin 2022). Wuhan Library distributed QR codes in over fifty communities for cloud reading access and launched an online reading marathon with 15,545 participants. The National Library of China also introduced various online reading activities to keep readers engaged remotely (Xin 2022). Salubi (2023) proposed a “libraries of the future” framework where they identify several strengths and opportunities for libraries. These include trustworthy information sources, learning and teaching support, research collaboration, and digital and scholarly communication fed by technology-enhanced future information services. These services include information literacy and fact-checking to fight disinformation, data management and data literacy, preservation of cultural heritage, digital humanities, and democratization of access to accurate information and authoritative knowledge.

2.2 Knowledge Management in Libraries

Several previous studies have been conducted on KM in libraries (Agarwal and Islam 2014, 2015; Islam et al. 2013, 2015, 2017). Malaysia (2012) investigated the role of KM in enhancing library user experiences and satisfaction. Studies have explored how KM practices can help a library gain competitive advantages, offer personalized services, and engage users (Balagué et al. 2016; Islam et al. 2014; Kim and Abbas 2010). There is growing interest among library staff in understanding the impact of KM initiatives on organizational culture. With increased budget cuts, spread of fake news, and its acceleration as seen during the COVID-19 pandemic, creativity and innovation is not just a luxury for libraries but needed for survival and continued relevance. Capturing, creating, organizing, and disseminating knowledge for patrons is part of what libraries do. Harnessing KM for these can help libraries be more effective and innovative. In an example of how libraries can use KM effectively, the Peking University Library restructured its organization to shift from traditional information management to a knowledge-focused approach. By redefining staff roles and workflows under the “knowledge stream” system, the library improved knowledge acquisition, organization, and innovation. This innovative application of KM fostered a better knowledge flow, enhancing service delivery and supporting the university’s growth (Xiao 2020). Academic libraries can use KM tools to improve collaboration in research and education. These tools help organize, store, and share information while building knowledge-sharing communities. Content Management Systems like DSpace, EPrints, and Greenstone are commonly used to store research outputs and institutional resources. Additionally, reference management tools such as Zotero, Mendeley, and EndNote help researchers organize citations and share reference libraries (Ratkanthiwar et al. 2024).

2.3 Theoretical Lens

In our research, we used three studies as a theoretical lens to guide our work. For library challenges, we use the findings tabulated by Ashiq et al. (2022) to inform our data gathering and analysis (see Table 1). We can ascertain if the challenges identified in our study are similar to the ones found by Ashiq et al. (2022) in a post-COVID scenario.

For KM readiness, we use Agarwal and Marouf (2016) and Marouf and Agarwal (2016) to guide our study and adapt them from a university to a library setting. Agarwal and Marouf proposed qualitative and quantitative instruments for individual and organizational factors that affect and individual’s readiness to participate in a KM initiative, which in turn affects the perceived organizational readiness to adopt KM. This assessment of KM readiness is important before KM adoption and implementation can be initiated in any organization. The organizational factors affecting KM readiness are knowledge sharing culture, decentralized structure, organizational support, top management support, and technology infrastructure. Marouf and Agarwal carried out a survey of 1,263 faculty members from fifty-nine accredited Library and Information Science programs in universities across North America to determine if universities were ready to adopt KM or not. They assessed the effect of individual factors of trust, knowledge self-efficacy, perceived degree of collegiality, openness for change, and reciprocity on individual readiness. They found that apart from trust, all other factors positively affected individual readiness, which affected organizational readiness to adopt KM. In our study, we are trying to determine if libraries are ready for knowledge management. This would pertain to the organizational readiness of libraries for KM. Specifically, we want to study how librarians perceive the role of KM in helping mitigate the various challenges that they face. This would pertain to the individual perceptions of librarians in determining if their libraries are ready to adopt KM or not. Thus, Agarwal and Marouf (2016) and Marouf and Agarwal (2016)’s studies on KM readiness are applicable in our quest to answer our second research question.

3 Methodology

We used an open-ended survey to gather data for our study (Boeren 2019; Fowler Jr. 2013). The survey was applicable and open to anyone working in a library. The subject population was primarily academic librarians. However, people working in other types of libraries such as public and special libraries were not precluded from participating in the study as the findings of library challenges and the role of KM would be applicable to them as well. Academic librarians are the people who interact with colleagues and other stakeholders, assist patrons with providing services, and find reference and research materials when asked for by people. Academic librarians focus on the acquisition, organization, and dissemination of academic and research information, while other librarians potentially handle more diverse patron needs.

We announced the survey through mailing lists – the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA) KM mailing list (www.ifla.org) and the Association for Information Science & Technology (ASIS&T) SIG KM mailing list (www.asist.org). These are the mailing lists pertaining to knowledge management that are managed by different library and information science associations and organizations. We also announced the survey to our university listservs, the Simmons University School of Library and Information Science student mailing list and the Librarians and Information Scientists, Bangladesh (LISBd), on our own social media handles, asked people to share, and reached out to academic libraries directly through email as well.

The survey questionnaire was designed using a Google form and had an informed consent section at its beginning. IRB approval was obtained from the Simmons University IRB to carry out the survey. Participation was voluntary. None of the questions were made compulsory. Thus, a participant could choose not to answer a question they were not comfortable with. Questions (see Table 2) were either self-developed or adapted from past studies. The primary data for the study was gathered in a three-month period from July to September 2023.

Survey questions.

| Demographics | Gender, birth year, current job title/role, name and location of library, time in the field of work, time in current job, highest education, specialization in highest degree of study |

| Library strengths and challenges (self-developed) | What are the things that are going well at your library? The strengths? In which areas is your library struggling? What challenges do you face? Is your library concerned about these challenges? Please elaborate how these impact your library. a) disinformation and fake news (infodemic); b) COVID pandemic and its aftereffects; c) budget cuts; d) competition from technology (Google, smartphones, Artificial intelligence/ChatGPT); e) any other challenges. |

| Library awareness and readiness for KM (adapted from Agarwal and Marouf 2016; Marouf and Agarwal 2016) | Have you previously heard of knowledge management? If yes, how and where? Does your library have a knowledge sharing culture? Please explain. Do you have top management support and technology infrastructure for knowledge sharing? Please explain. Does your library have any knowledge management practices (e.g. incentives or rewards for knowledge sharing; novel ideas and innovation supported or funded; brainstorming meetings, retreats, etc.)? Please explain. Do you think adopting KM will help your library? If so, how? |

4 Data Analysis and Findings

We analyzed our data using Excel and ChatGPT. We experimented with ChatGPT prompts to analyze the responses to open-ended questions. For that, we had to do data cleaning, as well as prior classification of responses to get more accurate themes. For example, for the question, “Have you previously heard of knowledge management? If yes, how and where?”, we classified the 109 responses into four categories – yes, qualified yes, unsure, and no. Then, we gave the open-ended responses pertaining to each category to ChatGPT with a prompt such as: “Summarize this data into categories. I will provide the data. Include quotes where relevant.” ChatGPT would then provide a set of themes with quotes. We then verified the ChatGPT response for accuracy, asked more specific questions to ChatGPT if needed, and further manually analyzed the themes/responses along with the data to arrive at the final findings that we include in the paper. The results of our analysis are presented below. The interpretation of the study findings is done in the Section 5 Discussion.

4.1 Demographics

We surveyed 109 practicing librarians from twenty-one countries in six continents, with 56 % of the respondents from North America, 23 % from Asia, 6.5 % each from Africa, and Europe, and the rest from Oceania and South America. They included 56 % librarians, 27 % library directors or heads, and 14 % library assistants. A majority of these (66 %) were female, with about 25 % male, and 6.5 % identifying as non-binary, other, or preferring not to disclose their gender. The participants ranged from twenty-three to seventy years of age with an average age of forty-three (see Table 3). They had been in the LIS field from just starting to forty years, with an average of 13.5 years, and in the current job averaging 6.5 years. About 65 % of the respondents had master’s degrees, 23 % bachelor’s, 7 % doctoral, and 2 % had certificates or diplomas. Further, 65 % of the participants had specialized in LIS, 5 % in history, about 4 % in English, 3 % in education, and the rest in other fields (see Table 4).

Demographics – gender, age, job title/role, library location.

| Gender | Age (years) | Job title/role | Location of library |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male 27 (24.78 %) Female 72 (66.05 %) Other 6 (5.5 %) – non-binary 4, agender 1, trans 1 Prefer not to say 1 (0.92 %) Unspecified 3 (2.75 %) |

Mean 43 Median 41.5 Mode 35 Min 23 Max 70 Unspecified seven responses |

Director/Head 29 (26.61 %) Librarian 61 (55.96 %) Library Assistant 15 (13.76 %) Unspecified 4 (3.67 %) |

USA – 60 (55.05 %) Bangladesh – 18 (16.51 %) India, Nepal, Nigeria, Pakistan, South Africa, Switzerland – 2 (1.83 %) each Australia, Belgium, Canada, Chile, Croatia, Czech Republic, Norway, Tanzania, UAE, Uganda, UK, Vanvuatu, Zimbabwe – 1 (0.92 %) each Not provided – 6 (5.5 %) |

Demographics – time in field, time in job, education, specialization.

| Time in field of work | Time in current job (years) | Highest education | Degree specialization |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean 13.55 years SD 9.79 years Median 12 years Mode 12 years Min 0.5 years Max 40 years Unspecified 4 |

Mean 6.43 SD 6.75 Median 12 Mode 12 Min 1 month Max 29 Unspecified four responses |

Doctoral = 8 (7.34 %) Masters = 71 (65.14 %) Bachelors = 25 (22.94 %) Certificate/Diploma = 2 (1.83 %) Unspecified = 3 (2.75 %) |

LIS = 71 (65.13 %) History = 5 (4.59 %) English = 4 (3.67 %) Education = 3 (2.75 %) Others = 19 (17.43 %) Unspecified = 7 (6.42 %) |

4.2 Library Strengths

We asked our survey respondents on what is going well at their library and what their areas of strength are. They indicated library facilities and collections; services and programs; user engagement and outreach in a safe environment; technology and innovation/online resources; staff, teamwork, and training; and community support and funding as some of areas of strength for the library (see Table 5).

Library strengths.

| Areas of strengths | Responses |

|---|---|

| Library facilities and collections | Their library being the “largest and oldest academic library in our country”, having “incredible new facility with makerspace, recording studio, cafe, commercial kitchen, history room, and archive”, “state of the art building, infrastructure, impressive collection”, and a “well-running up-to-date collection.” |

| Services and programs | “Regular library committee meetings to improve services, fast decision-making”, “a wide variety of services such as reference assistance, user education, guided campus tours”, “children’s programs, well-attended book clubs, popular Library of Things collection”, “training …for the users”, and “services to researchers at undergraduate, graduate and postgraduate level both in print and electronic formats.” |

| User engagement and outreach in a safe environment | “A lot of students consider the library a safe place to be and consider us safe people to talk to” and that while the library is open, “there are always students in the library”. They talked about having a “supportive community” with “low threshold services”, “well-attended programs”, and “new releases, special programs, children’s room”. Community engagement was important to the library, “providing services to researchers at undergraduate, graduate and post-graduate level both in print and electronic formats”, and “reaching all school kids in our city”. |

| Technology and innovation/online resources | “IT support for users”, “more online resources and hybrid participation”, “access to technology”, “reader service, Turnitin service (new addition)“, etc. For ease of remote access, the participants indicated increasing online services. Respondents indicated a provision of “e-library services”, “electronic resource access, researcher interest in the Archives”, “collection of e-contents (e-books, e-Journals, ETDs [electronic theses & dissertations], proceedings, etc.).” |

| Staff, teamwork, and training | “Great teachers”, “well-organized,… trained… [workforce]“, “excellent teamwork, innovative thinking”, “…a more employee-centric approach at the library… starting in 2021, which has introduced many new employee programs.” |

| Community support and funding | “Strong community support, active trustees”, “public support”, a “robust foundation [that] helps keep the library functional and afloat even in the face of underfunding from town”, and mentioned being “well-funded.” |

4.3 Library Challenges

We asked our survey respondents about areas in which their library is struggling and the challenges that they face. They indicated collection, budget, and resource challenges, “We haven’t been able to acquire nearly as many materials/resources for kids as we’d like to, in order to run programs for our students”; mental health, safety, and security, “mentally unstable, short-tempered, impatient patrons have increased,” “there has been some physical assaults and a lot of mentally draining situations”; inadequate staffing, “because we do not have a large staff, there are certain projects that need to be put on hold”; staff morale, training, and leadership, “we are not paid well, and that strongly affects morale,” “The director is on the cusp of retiring and is uninspired, not doing much”; building, maintenance, and space challenges, “budget constraints and a deteriorating library building that isn’t being prioritized,” “building issues (water damage, HVAC, etc.),” “the space is too small”; social media and promotion, “the promotion of its services and resources to the community is also a challenge”; aftereffects of COVID-19, “people are still afraid of small group programs where people sit close together,” “remote work policy,” “we have experienced a huge uptick in informal challenges to our collections and programming”; continuing relevance due to technology changes, “fewer books were checked out last year than the year before,” “budget – lacking sufficient/current technology,” “OPAC is not fully operational”; and diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) challenges, “challenges to books with LGBTQ themes” and “perception of librarians as ’groomers’ and woke.” (terms relating to self-righteousness and lack of trust by the patron). A lot of the challenges such as inadequate collections or staffing, low maintenance of buildings, marketing and promotion, etc. were linked to money and budget constraints.

We asked the survey respondents to elaborate further if the library is concerned about specific challenges brought about by a) disinformation and fake news (infodemic); b) the Covid pandemic and its aftereffects; c) budget cuts; d) competition from technology (Google, smartphones, Artificial intelligence/ChatGPT); and e) any other challenges and how they impact the library (see Table 6).

Major challenges faced by libraries.

| Areas of challenges | Responses |

|---|---|

| Disinformation and fake news (Infodemic) | Most survey respondents showed concern about disinformation, largely because of its easy access, “we have entered a new world, once again, where there is bad information everywhere – much easier to find nonsense than correct information” and because people tend to believe them, “AI is also wreaking havoc on our teen population because they simply believe everything they see.” They listed the problems brought about by this: “Infodemic undermines the credibility of libraries as a source of credible information and creates confusion among library users.” “Disinformation about the library is impacting us and creating bad feelings about the library in the community and leading to challenging conversations about our collections and programming.” Libraries are playing a role in helping sieve correct information from the false. “We’re always concerned about the ‘infodemic’ and do our best to transparently provide vetted information.” |

| COVID pandemic and its aftereffects | Librarians talked about the patron use of e-resources as an aftereffect of the COVID pandemic. “During…COVID…, dependence and the use of e-resource, e-books, digital and electronic services by library users were dramatically increased.” “We are still recovering as far as library usage and circulations from the lows experienced during the pandemic closure.” “The pandemic taught everyone to use ebooks, so that is a huge help to the patrons.” They also talked about the effect of the pandemic on both the patrons and the staff, and how some of these might last for a long time. “Covid…left a fear of huge gathering. Physical training is no longer attended to because of fear.” “Covid pandemic continues to affect staffing, which can delay access to resources.” “We still have staff who wear masks and would like it to be policy that everyone be required to wear masks.” “COVID was always going to be something that is looming around, even if we have vaccines now.” |

| Budget cuts | Librarians cited budgets cuts as a major issue faced by libraries. They impact libraries by “reducing the number of staff, limiting their ability to provide services and resources to the community”, creating “shortage of relevant materials”, and “books hav[ing] not been purchased for the past three years.” Others cited the difficulties caused by limited budgets. “The library was undergoing a renovation during COVID and even though the new library has almost 2X the footprint as the former building, the operating budget is still close to what it was during the pandemic” “We were held to a 1.5 % increase last fiscal year, which barely covers our increase in electricity, leaving nothing extra for materials.” ”[the] town funding [is unable] to keep up with inflation.”. Some responses mentioned managing despite the cuts. “Budget cuts [are] always [difficult], but we manage maybe because we are a small Library in a great community.” “Budget cuts haven’t been a big issue for us, although there have been minimal, if any, raises for staff in years.” |

| Competition from technology | Technologies such as Google, smartphones, and Artificial intelligence/ChatGPT challenge libraries, leading to “people…using…[library] databases much less with the rise of Google.” “The biggest challenge with smartphones is getting patrons to not use them loudly in public areas.” “In this internet era, especially from social media, everyone becomes an expert. Sometimes it really hampers the regular work.” Others cited difficulties with libraries not keeping up with change. “The gap between the rapid change of technological uplift in the field of library and most of the mindsets of library planners to adopt or cope up with these rapid development is one of the core hindrances”. There were supportive voices for technology as well. “The use of technological devices and tech-based service is severely active now than usual time. This is the positive change of our library user community.” “I don’t feel like there is an actual threat from technology, but there is a perception that the library is no longer as needed because of technology.” “Technology is not something we are in competition with but is a tool that our library can utilize to increase access and services.” “We do not compete with technology. We support our patrons as they learn to navigate new options.” “[Our] library is not concerned about technology as competition, but rather as a tool.” |

| Other challenges | These included dealing with difficult patron situations, staff turnover, and building maintenance and improvement. “We need social workers at each branch where we are constantly dealing with difficult situations against mentally unstable patrons, homeless patrons, etc.” “Staff turnover is too much and having a union is a joke.” “Staffing is the major issue. We do not have enough staff to provide all our services at during all operating hours.” “The only other challenge we are facing is one of building maintenance. We are in a building which is partly from the 1800s with an addition from the early 80s. We have leaks everywhere and not enough space for materials.” “community is not united in their opinion on how to move forward with improving facilities-build new in a centralized location or renovate 2 old buildings.” |

4.4 Library Awareness and Readiness for KM

We asked five questions to the survey participants focusing on the degree to which their library was aware of and ready for KM.

4.4.1 KM Awareness

Seventy participants (64.22 %) had heard of KM while 36 (33.03 %) hadn’t heard of it before. Three participants did not respond. Respondents indicated that they became familiar with KM through one or more channels including academic courses (fifty-three responses), reading and research (thirty responses), conferences and seminars (seventeen responses), work experience (twelve responses), and professional training (eight responses). Thus, they acquired knowledge of KM through a combination of formal education, professional development, and practical experience. The counts are more than the seventy positive responses as many people indicated multiple avenues through which they heard about KM.

4.4.2 Knowledge Sharing Culture

When asked if their library had a knowledge sharing culture, sixty-five respondents (59.63 %) said yes, eighteen said yes but with conditions (16.51 %), six were unsure (5.5 %), sixteen (14.68 %) said no, while four participants did not respond to the question. For those that reported having a culture of knowledge sharing in their libraries, various channels and practices are employed to encourage knowledge sharing. This includes group discussions, presentations, social media, meetings, and collaborations. Many libraries use tools like shared drives, intranets, and collaboration platforms to facilitate this culture. Some libraries also participate in consortia and organize seminars or symposiums to share knowledge. While there might not always be formal policies, the general trend is toward promoting knowledge sharing among staff and with library users. There is an emphasis on communication, collaboration, and documentation to support this culture.

These are examples of some “yes” responses: “Yes, we are pretty good at communicating knowledge throughout the organization by means of regular staff and department meetings, email and in internal Intranet to disseminate information”; “My library uses collaboration tools such as Teams to share and organize knowledge and information”; “We save and document and share. We have multiple people trained to do several jobs”; “We have a consortium with different email lists; we are able to share information easily and often”; “The most significant knowledge sharing culture of the… library is one that fosters an environment of collaboration and open communication among library staff and patrons.”

Those who indicated a qualified yes with conditions mentioned limited or inconsistent knowledge sharing: “Information between departments often travels slowly and management sometimes fails to keep staff aware of changes”; “We create documentation and lots of meeting notes, not so much active sharing and teaching”; “Practical knowledge is shared to deliver more consistent services; however, specialized knowledge tends to be siloed in pertinent departments without appropriate dissemination procedures in place. This leads to some confusion, inefficiency, and errors.”

Those who indicated a lack of knowledge sharing culture in their libraries cited factors such as technological limitations, divided practices among different departments, insufficient training and understanding of knowledge management, and issues related to management and staff turnover. Some responses highlighted challenges such as a lack of documentation, difficulties in finding the right information or personnel, and the small size of the library: “I believe our library does not have a knowledge sharing culture. The practices of different departments are very divided from each other”; “We do not have the current technological support to make this a reality”; “I believe this stems from having poor management for the last few years. The Director did not share information willingly with staff and did not leave much behind when he left”; “It’s been one of my major struggles here, finding exactly the right person who knows about exactly the thing that I need.”

4.4.3 Top Management Support and Technology Infrastructure for Knowledge Sharing

We asked if the library had top management support and technology infrastructure for knowledge sharing. Fifty-two indicated yes (47.71 %), twenty-four qualified yes (22.02 %), nine were unsure (8.26 %), eighteen said no (16.51 %), and six provided no responses.

These are some of the reasons provided indicating management and leadership support for knowledge sharing: “Our top management is highly supportive of knowledge sharing initiatives”; “The board of directors is directly involved in the day-to-day functioning of the library”; “We encourage idea generation and sharing information from conferences and events”; “We have leaders in each area of the firm and a KM system”; “Director and Friends group support novel ideas and innovations, funding materials and opportunities.” Participants also provided examples of technology infrastructure for sharing: “We do have state-of-the-art technology infrastructure for knowledge sharing”; “We use Microsoft SharePoint to share information”; “We have several places where knowledge sharing can take place, including a staff wiki and Google Drive.”

These were some of the responses for a qualified yes for management support and technology infrastructure: “Library management is supportive, however some of the town management remain somewhat skeptical about the value of the library and knowledge sharing”; “Support is there, but knowledge is lacking”; “We currently just use email, and Google Apps for education and not really a dedicated knowledge management system”; “Our technology infrastructure is improving with the dedication of a tech-savvy and super-intelligent Tech Services/IT librarian.”

Some were unsure: “If we do, then I trust upper management supports it, but at this time I am not sure.” The reasons for lack of management support and infrastructure were provided as follows: “No, we currently do not. But I hope that will change next year as the current director retires”; “People have been reprimanded for spending too much time ‘socializing’ when they were discussing programming ideas across departments”; “Our IT support is very limited (overworked) and heavily protected”; “We don’t have any such knowledge sharing infrastructure. Unofficially we share knowledge in soft form through e-mail, one-drive, or USB”; “Despite there being an internal demand for KM from the library on its holdings, we do not have the tech support to implement such capabilities”; “Our town is weak in adopting and maintaining current technologies. This is a major weakness across the entire town.”

4.4.4 Knowledge Management Practices

We asked the survey participants if their library had any KM practices (e.g., incentives or rewards for knowledge sharing; novel ideas and innovation supported or funded; brainstorming meetings, retreats, etc.). Forty-three said no (39.45 %), thirty-six said yes (33.03 %), sixteen qualified yes (14.68 %), six were unsure (5.5 %), and eight provided no responses.

This was the justification provided for lack of KM practices in the library: “There’s no incentive here to do better. The acknowledgement is only shown through words in a capitalistic society. [In] 2 years in the branch, I’m doing more work than the people who [have] been in the system for 20 years. If you are capable, they just take advantage of you”; “I like to use the analogy that if certain library folks were hit by a bus tomorrow, we would have no idea how to do their jobs because it’s not documented anywhere and most folks do not have any sort of back-up or cross-training”; “The practice is almost entirely top-down with very little incentives to share knowledge. I have already been scolded for sharing an idea directly to my colleagues without going first to my top one”; “There are no rewards for KM in my public library except maybe a thumbs up in a reply all email. We are encouraged to attend webinars and other professional development opportunities, but they aren’t really funded”; “All positions in the library are tightly controlled and unionized. No financial incentives are available. And town government’s thinking is quite limited and not aligned with library services or innovation.”

Respondents who indicated having successful KM practices listed: recognition and incentives, “Upper management provides special salary increments or promotions based on recommendations from the librarians to those who make significant contributions to our knowledge management processes,” “Incentives for knowledge-sharing include stipends ranging from $38.50 to $75 an hour,” “Travel grants and awards for submitting know-how incentivize knowledge sharing”; sharing platforms and practices, “Knowledge sharing is a part of every project, with documentation and instructions expected for future project members,” “Regular meetings, retreats, and workshops facilitate knowledge sharing,” “Library meetings, strategic planning sessions, and consortium activities contribute to information exchange”; technology and systems, “KOHA LMS is used for knowledge management,” “Funding is available for implementing knowledge-sharing systems”; training and development, “Trainings are supported and funded, and staff actively participate in teaching and learning,” “Funds are available for professional development if relevant to the current position,” “Monthly staff meetings, staff development days, and industry conference attendance are part of the learning culture”; communication channels, “Intranet, email blasts, and Shout-Out forms are employed for information dissemination and recognition”; and community engagement, “[we have] staff days for knowledge sharing, updating methods, and regular meetings of the Library Leadership Team.”

Some participants listed limited KM practices: “There’s only two of us working in the library generally, so we try to meet to discuss ideas but can’t always execute them the way we’d like”; “Verbal appreciations at staff meetings every month”; “There is no incentive or rewards, due to no such policy and budget, but we arrange brainstorming meetings and retreats”; “Innovation is supported when finances allow, retreats have happened with new leadership”; “Meetings once or twice a year, if that [counts].”

4.4.5 Perceived Helpfulness of KM to the Library

Participants were asked if adopting KM will help the library. Seventy-one (65.14 %) said yes, thirteen (11.93 %) qualified yes, ten (9.17 %) were unsure, two (1.83 %) said no, and thirteen provided no responses. Participants overall felt that adopting KM will enhance knowledge sharing, communication, and collaboration, “make it easier for people to work together,” “help in cross-collaboration between departments,” “lead to more transparent communication,” “promote better communication and inspire staff”; increase efficiency, “boost efficiency and productivity,” “cut down on staff time needed for training new employees,” “streamline processes and simplify tasks,” “help them make better decisions,” “improve customer service”; help retain organizational knowledge, “preservation of institutional repository and locally produced contents,” “maintaining continuity amidst staff turnover,” help support and train new employees “imparting hands-on training to employees,” “developing skills of colleagues,” “support any new library staff,” “help new staff learn what we do and how we do it”; and encourage innovation, “encourage new ideas,” “develop innovative and relevant services.”

The more guarded responses included not having enough information, “It sounds fantastic but I don’t know enough about it,” “there is a need to introduce the management and the employees with the concept of KM and then start to think how it will help”; yes and no, “we don’t have much organizational knowledge to benefit but I think the overall transfer and sharing of knowledge would benefit,” “Yes, if the library manager has deep knowledge and expertise, and No if his wrong ideas transferred to the newcomers”; and not having the right technology knowhow and resources for KM, “I think it could, but the technological aptitude of our librarians varies greatly, so the buy-in to learn new things isn’t always easy to come by,” “It could with the proper technology and staff time and resources to update and maintain it,” “That would be nice, but it would also be another system to maintain. We kind of operate in silos, so it would be a lot of duplicated work… We use Niche Academy and a shared drive, but it’s still quite clunky,” “Somewhat, but again, we’re small, and the effort to keep up anything formal would be more cumbersome and inefficient than what we do now.”

Some were unsure: “I would have to weigh my options, but this appears like an interesting proposal for a library,” while two said no, “I don’t really know enough about it, but things seem to be working well for us as is.”

5 Discussion

Our first research question was, “What are the challenges faced by libraries?” The study found that while libraries are strong in their traditional service offerings, they continue to face a myriad of challenges. Many of the challenges were linked to budget constraints. A majority of the participants had heard of KM before, about 60 % said they had a knowledge sharing culture, and about half the respondents indicated top management support and technology infrastructure for knowledge sharing. About 40 % of the participants said they did not have KM practices such as incentives or rewards for knowledge sharing, novel ideas and innovation supported or funded, brainstorming meetings, retreats, etc. Many of the challenges, especially those pertaining to threat from technology (Mohammed et al. 2022; Ojobor 2023) and budget constraints (Green 2022; Hall and Duggins 2021) were also identified in prior literature, but many have been aggravated due to recent events like the COVID-19 pandemic (Ashiq et al. 2022), the acceleration of disinformation and fake news (Sullivan 2019; Tripodi et al. 2023), and common use of smartphones, and now AI, which make it harder for the library to prove its relevance to the common patron. Ashiq et al. (2022) had identified the challenges faced by libraries during COVID-19. We found that some of the immediate challenges of 2020 or 2021, when COVID was at its peak, such as fear of the pandemic, restriction on book borrowing, etc. did not surface as much. However, the overall challenges that libraries face including lack of resources and funding, inadequate digital collection, lack of literacy skills in users, technology frustrations and failures, etc. continue to apply.

Table 7 lists library strengths and challenges in the first two columns. As we can see, some of the library strengths identified in our study can also be challenges for certain libraries depending on their size, budget, resources, and financial support they have. While we list technology and Artificial Intelligence (AI) as a challenge, new modern KM technologies can further strengthen the library’s role in bridging the digital divide and serving underserved populations, including those with limited internet access, technological capabilities, or residing in remote areas. For example, public libraries have been instrumental in introducing 3D printing technology to marginalized and underserved communities in the United States. By providing access to these tools, Woodson et al. (2020) argue how libraries can help bridge technological gaps and promote skill development. Similarly, AI holds great promise for helping libraries and its patrons if we can surmount its ethical concerns and figure out ways to use it appropriately.

Library strengths, challenges, and KM readiness.

| Library strengths | Library challenges | KM readiness |

|---|---|---|

| Facilities and collections Services and programs User engagement/outreach Online resources and technology Staff, teamwork, training Community support/funding |

Disinformation Aftereffects of COVID-19 Technology and AI Budget, staffing, and space Mental health, safety, and morale Diversity, equity, and inclusion |

KM awareness Knowledge sharing culture Top management support Technology infrastructure KM practices – incentives and rewards, training, engagement, communication |

Our second research question was, “How do librarians perceive the role of KM in helping mitigate the challenges they face?” A majority (65 %) of the participants felt that adopting KM should be helpful to the library, with another 12 % saying yes with some reservations. This indicates that there was overall support for KM. This is in line with the arguments that many researchers (e.g. Kim and Abbas 2010; Islam et al. 2013, 2014, 2015, 2017; Agarwal and Islam 2014, 2015; Balagué et al. 2016) have been making about the applicability of KM in libraries.

Marouf and Agarwal (2016) had identified individual factors such as trust, knowledge self-efficacy, perceived degree of collegiality, openness for change, and reciprocity affecting individual readiness of professors to participate in a KM initiative at their university. Agarwal and Marouf (2016) had identified organizational factors such as knowledge-sharing culture, decentralized structure, organizational support, top management support, and ICT infrastructure affecting individual readiness as well. This individual readiness would, in turn, affect the perceived organizational readiness to adopt KM. In our study, apart from KM awareness, which can be an individual factor, the organizational factors either facilitating or inhibiting KM adoption in libraries were knowledge sharing culture, top management support, technology infrastructure, and other KM practices. Table 7 (rightmost column) lists the KM readiness factors covered in the study.

6 Implications and Conclusions

The existing library challenges were addressed by our first research question where we investigated the specific areas where libraries are struggling. The results confirm that many of the challenges introduced – such as budget constraints, technological disruptions, and a lack of digital resources – are prevalent in practice, thus reinforcing the prevalent literature and our theoretical lens. Based on prior literature, we presented KM as a potential strategic solution, whereby our second research question sought librarians’ perceptions of KM’s role in addressing these challenges. The results showed that while awareness and partial adoption of KM practices exist, full integration is limited by structural and cultural factors. Thus, KM can be beneficial to libraries once libraries show leadership support for it and help provide the needed infrastructure for KM implementation. The findings offer evidence that the adoption of KM practices, if strengthened, could help libraries overcome many of the structural and technological challenges highlighted at the outset.

This study can be useful for libraries to ascertain both their strengths and weaknesses, especially post the COVID-19 pandemic, which, along with disinformation, technology and AI, and budget constraints, has brought in a new set of challenges. The indirect benefit to study participants, as well as librarians and researchers, is developing awareness of KM and its potential help in overcoming library challenges. Even if the libraries did not recognize the sharing and use of KM as important until now, the findings of this study should help them to consider KM as important. If they put KM into practice, it will help the libraries become more creative and innovative in the long run. An important contribution of this paper is a model of perceived helpfulness of KM to the library to overcome its challenges. As we can see from the model, KM readiness and KM practices already prevalent in the library (culture, infrastructure, rewards, incentives for sharing, etc.) moderate and help determine the degree to which KM will be helpful to the library in overcoming its many challenges.

7 Limitations and Future Work

The study has several limitations.

First, this study is part of a larger survey which also included questions on: a) knowledge retention and transfer in libraries – how does the library retain the knowledge of people who leave or resign from the library and provide organizational knowledge to new employees; b) KM implementation in libraries – if the library was to implement KM, what would be the best way to go about it, what things to need to be in place; and c) KM tools in libraries – what technology tools and non-technology mechanisms would be useful to implement KM in the library. Since this paper focused on library challenges and the role of KM in overcoming those, these additional findings focusing more on KM implementation and strategy will be analyzed and shared in future publications. There could also be follow-up questions on why KM is not practiced in particular libraries, which will lead light on the reasons behind a lack of knowledge sharing or a KM culture.

Second, though this was a global survey, about 55 % of the respondents were based in the US. Thus, the findings will be US-centered in many cases. The data needs to be analyzed separately for US and other countries to see if there are regional differences in the library strengths, challenges, and KM practices found in the study. Also, as the survey collected data from libraries in vastly different contexts, there can be differences in the types of services likely be routinely offered in different countries. Thus, the degree of generalizability of findings may be limited by these differences.

Third, the study included data from anyone working in a library, apart from the primary focus area of academic libraries. In the field for “name and location of libraries,” many participants included only the location. From those that included the names, fourteen mentioned “public library.” Thus, at least 12.8 % of the participants are from other types of libraries apart from academic libraries. Asking specific questions on the “type of library” and separating data based on library type, e.g. academic, public, or special libraries, might bring out differences in findings.

Fourth, some people may question the use of ChatGPT for categorizing our data, considering flaws in ChatGPT, and might prefer more traditional means of data analysis. However, we wanted to both try out and demonstrate how AI tools can be used for data analysis in LIS studies. We vetted any analysis done or categories generated by ChatGPT manually as well. Also, the study did not specifically cover the recent use of AI and AI tools in libraries. Future studies should focus on the impact of AI on libraries.

Finally, the proposed research model for the perceived helpfulness of KM to the library to overcome its challenges should be tested using other methods such as quantitative surveys and in-person interviews and focus groups.

Acknowledgments

The data for the survey was gathered to supplement the chapters of an upcoming book on KM in Libraries. We employed ChatGPT 3.0 for the data analysis of our open-ended survey responses, and for the generation of categories and identification of relevant quotes from the data. We manually evaluated the output. We did not use generative AI tools/services for any other content to author this submission. The authors assume all responsibility for the content of this submission.

References

Abeysekera, K. H. T., A. H. K. Balasooriya, and M. M. I. K. Marasinghe. 2020. “Best Practices in Library Management During Covid-19 Pandemic: Case of the Library, the Open University of Sri Lanka (OUSL).” Sri Lanka Journal of Management Studies 2 (2): 147–54. https://doi.org/10.4038/sljms.v2i2.43.Suche in Google Scholar

Agarwal, N. K., and M. A. Islam. 2014. “Knowledge Management Implementation in a Library: Mapping Tools and Technologies to Phases of the KM Cycle.” VINE Journal of Information and Knowledge Management Systems 44 (3): 322–44. https://doi.org/10.1108/VINE-01-2014-0002.Suche in Google Scholar

Agarwal, N. K., and M. A. Islam. 2015. “Knowledge Retention and Transfer: How Libraries Manage Employees Leaving and Joining.” VINE Journal of Information and Knowledge Management Systems 45 (2): 150–71. https://doi.org/10.1108/VINE-06-2014-0042.Suche in Google Scholar

Agarwal, N. K., and L. Marouf. 2016. “Quantitative and Qualitative Instruments for Knowledge Management Readiness Assessment in Universities.” Qualitative and Quantitative Methods in Libraries 5 (1): 149–64. https://www.qqml-journal.net/index.php/qqml/article/view/313 (accessed October 20, 2025).Suche in Google Scholar

Ameen, K. 2021. “COVID-19 Pandemic and Role of Libraries.” Library Management 42 (4/5): 302–4. https://doi.org/10.1108/LM-01-2021-0008.Suche in Google Scholar

Ashiq, M., F. Jabeen, and K. Mahmood. 2022. “Transformation of Libraries During Covid-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review.” The Journal of Academic Librarianship 48 (4): 102534. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2022.102534.Suche in Google Scholar

Ashiq, M., S. U. Rehman, and G. Mujtaba. 2021. “Future Challenges and Emerging Role of Academic Libraries in Pakistan: A Phenomenology Approach.” Information Development 37 (1): 158–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266666919897410.Suche in Google Scholar

Balagué, N., P. Düren, and J. Saarti. 2016. “Comparing the Knowledge Management Practices in Selected European Higher Education Libraries.” Library Management 37 (4/5): 182–94. https://doi.org/10.1108/LM-12-2015-0068.Suche in Google Scholar

Bashorun, M., B. Babaginda, R. Bashorun, and I. Adekunmisi. 2021. “Transformation of Academic Library Services in Coronavirus Pandemic Era: The New Normal Approach.” Journal of Balkan Libraries Union 8 (1): 42–50. https://dergipark.org.tr/en/download/article-file/1669730 (accessed October 20, 2025).Suche in Google Scholar

Boeren, E. 2019. “The Roles of Quantitative and Qualitative Data Gathering in Survey Research.” In Scholarly Publishing and Research Methods Across Disciplines, edited by E. Boeren, J. A. Henschke, S. L. Munn, E. O’Donnell, M. S. Plakhotnik, T. S. Rocco, et al.., 135–58. IGI Global.10.4018/978-1-5225-7730-0.ch007Suche in Google Scholar

Casselden, B., and E. Paxton. 2024. “Learning from Audiobook Usage in Public Libraries During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Journal of Librarianship and Information Science. https://doi.org/10.1177/09610006241251858.Suche in Google Scholar

Chaffey, D. 2024. “Global Social Media Statistics Research Summary 2024.” https://www.smartinsights.com/social-media-marketing/social-media-strategy/new-global-social-media-research/#:∼:text=According%20to%20the%20Datareportal%20January,online%20within%20the%20last%20year (accessed January 10, 2024).Suche in Google Scholar

Chigwada, J. 2020. “Preparedness of Librarians in Zimbabwe in Dealing with COVID-19 Library Closure.” Qualitative and Quantitative Methods in Libraries 9: 107–16. https://www.qqml-journal.net/index.php/qqml/article/view/628 (accessed October 20, 2025).Suche in Google Scholar

Cox, J. 2023. “The Position and Prospects of Academic Libraries: Weaknesses, Threats and Proposed Strategic Directions.” New Review of Academic Librarianship 29 (3): 263–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/13614533.2023.2238691.Suche in Google Scholar

Cox, A., and L. Brewster. 2020. “Library Support for Student Mental Health and Well-Being in the UK: Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” The Journal of Academic Librarianship 46 (6): 102256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2020.102256.Suche in Google Scholar

Dalkir, K. 2017. Knowledge Management in Theory and Practice, 3rd ed. MIT Press.Suche in Google Scholar

ExLibris. 2022. “Three Trends Shaping the Future of Libraries.” Library Journal. https://www.libraryjournal.com/story/three-trends-future (accessed August 23, 2024).Suche in Google Scholar

Fasae, J. K., C. O. Adekoya, and I. Adegbilero-Iwari. 2021. “Academic Libraries’ Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic in Nigeria.” Library Hi Tech 39 (3): 696–710. https://doi.org/10.1108/LHT-07-2020-0166.Suche in Google Scholar

FowlerJr.F. J. 2013. Survey Research Methods. Sage.Suche in Google Scholar

Frederick, J., R. C. Schonfeld, and C. Wolff-Eisenberg. 2020. “The Impacts of COVID-19 on Academic Library Budgets: Fall 2020.” The Scholarly Kitchen. https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2020/12/09/academic-library-budgets-fall-2020/ (accessed February 9, 2024).Suche in Google Scholar

Frederick, J., and C. Wolff-Eisenberg. 2020. “Academic Library Strategy and Budgeting During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Results from the Ithaka S+R US Library Survey 2020.” https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2020-12/apo-nid310046.pdf (accessed March 20, 2024).10.18665/sr.314507Suche in Google Scholar

Gotschall, T., S. Gillum, P. Herring, C. Lambert, R. Collins, and N. Dexter. 2021. “When One Library Door Closes, Another Virtual One Opens: A Team Response to the Remote Library.” Medical Reference Services Quarterly 40 (1): 11–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/02763869.2021.1873612.Suche in Google Scholar

Green, A. 2022. “Post COVID-19: Expectations for Academic Library Collections, Remote Work, and Resource Description and Discovery Staffing.” The Journal of Academic Librarianship 48 (4): 102564. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2022.102564.Suche in Google Scholar

Guernsey, L., S. Prescott, and C. Park. 2021. “Public Libraries and the Pandemic: Digital Shifts and Disparities to Overcome.” New America. https://www.newamerica.org/education-policy/reports/public-libraries-and-the-pandemic/ (accessed March 8, 2024).Suche in Google Scholar

Guo, Y., Z. Yang, Z. Yang, Y. Q. Liu, A. Bielefield, and G. Tharp. 2021. “The Provision of Patron Services in Chinese Academic Libraries Responding to the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Library Hi Tech 39 (2): 533–48. https://doi.org/10.1108/LHT-04-2020-0098.Suche in Google Scholar

Hall, A. R., and B. Duggins. 2021. “The Impact of the Early COVID-19 Pandemic Response on Kentucky’s Library Workforce.” https://ir.library.louisville.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1524&context=faculty (accessed April 10, 2024).Suche in Google Scholar

Harris, S. Y. 2021. “The Coronavirus Pandemic in the Caribbean Academic Library: Jamaica’s Initial Interpretation of Strengths, Biggest Impact, Lessons and Plans.” Library Management 42 (6/7): 362–75. https://doi.org/10.1108/LM-10-2020-0149.Suche in Google Scholar

Ifijeh, G., and F. Yusuf. 2020. “Covid-19 Pandemic and the Future of Nigeria’s University System: The Quest for Libraries’ Relevance.” The Journal of Academic Librarianship 46 (6): 102226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2020.102226.Suche in Google Scholar

IFLA. 2024. “Digitization in Libraries: The Challenges of Preservation and Accessibility.” https://www.ifla.org/news/digitalisation-in-libraries-the-challenges-of-preservation-and-accessibility/ (accessed January 7, 2025).Suche in Google Scholar

Islam, M. A., N. K. Agarwal, and M. Ikeda. 2017. “Effect of Knowledge Management on Service Innovation in Academic Libraries.” IFLA Journal 43 (3): 266–81. https://doi.org/10.1177/0340035217710538.Suche in Google Scholar

Islam, M. A., N. K. Agarwal, and M. Ikeda. 2014. “Library Adoption of Knowledge Management Using Web 2.0: A New Paradigm for Libraries.” IFLA Journal 40 (4): 317–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/0340035214552054.Suche in Google Scholar

Islam, M. A., N. K. Agarwal, and M. Ikeda. 2015. “Knowledge Management for Service Innovation in Academic Libraries: A Qualitative Study.” Library Management 36 (1/2): 40–57. https://doi.org/10.1108/LM-08-2014-0098.Suche in Google Scholar

Islam, M. A., M. Ikeda, and M. M. Islam. 2013. “Knowledge Sharing Behavior Influences: A Study of Information Science and Library Management Faculties in Bangladesh.” IFLA Journal 39 (3): 221–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/0340035213497674.Suche in Google Scholar

Johnson, P. 2020. “Libraries During and After the Pandemic.” Technicalities 40 (4): 2–8.Suche in Google Scholar

Kim, Y. M., and J. Abbas. 2010. “Adoption of Library 2.0 Functionalities by Academic Libraries and Users: A Knowledge Management Perspective.” The Journal of Academic Librarianship 36 (3): 211–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2010.03.003.Suche in Google Scholar

Koos, J. A., L. Scheinfeld, and C. Larson. 2021. “Pandemic-Proofing your Library: Disaster Response and Lessons Learned from COVID-19.” Medical Reference Services Quarterly 40 (1): 67–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/02763869.2021.1873624.Suche in Google Scholar

Kosciejew, M. 2021. “The Coronavirus Pandemic, Libraries and Information: A Thematic Analysis of Initial International Responses to COVID-19.” Global Knowledge, Memory and Communication 70 (4/5): 304–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/GKMC-04-2020-0041.Suche in Google Scholar

Koulouris, A., E. Vraimaki, and M. Koloniari. 2020. “COVID-19 and Library Social Media Use.” Reference Services Review 49 (1): 19–38. https://doi.org/10.1108/RSR-06-2020-0044.Suche in Google Scholar

MacColl, J. 2006. “Google Challenges for Academic Libraries.” https://www.ariadne.ac.uk/issue/46/maccoll/ (accessed April 10, 2024).Suche in Google Scholar

Machovec, G. 2020. “Pandemic Impacts on Library Consortia and Their Sustainability.” Journal of Library Administration 60 (5): 543–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/01930826.2020.1760558.Suche in Google Scholar

Malaysia, B. T. H. O. 2012. “Relationship Between Knowledge Management Practices and Library Users’ Satisfaction at Malaysian University Libraries: A Preliminary Finding.” Australian Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences 6 (12): 30–40.Suche in Google Scholar

Marouf, L. N., and N. K. Agarwal. 2016. “Are Faculty Members Ready? Individual Factors Affecting Knowledge Management Readiness in Universities.” Journal of Information and Knowledge Management 15 (3): 1650024. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0219649216500246.Suche in Google Scholar

Mbambo-Thata, B. 2021. “Responding to COVID-19 in an African University: The Case of the National University of Lesotho Library.” Digital Library Perspectives 37 (1): 28–38. https://doi.org/10.1108/DLP-07-2020-0061.Suche in Google Scholar

McKenzie, L. 2020. “Library Leaders Brace for Budget Cuts.” https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2020/12/09/university-library-leaders-prepare-uncertain-financial-future-amid-pandemic (accessed May 10, 2024).Suche in Google Scholar

Mehta, D., and X. Wang. 2020. “COVID-19 and Digital Library Services – A Case Study of a University Library.” Digital Library Perspectives 36 (4): 351–63. https://doi.org/10.1108/DLP-05-2020-0030.Suche in Google Scholar

Mohammed, A. Z., A. A. L. Gora, M. A. Usman, and M. L. Ibrahim. 2022. “Infopreneurial: Opportunities and Challenges for Library and Information Science Professionals in the 21st Century.” Asian Journal of Information Science and Technology 12 (2): 22–8. https://doi.org/10.51983/ajist-2022.12.2.3318.Suche in Google Scholar

Mudditt, A. 2015. “The Knowledge Supply Chain in the Internet Age: Who Decides what Information is Trustworthy?” The Scholarly Kitchen. https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2015/12/16/the-knowledge-supply-chain-in-the-internet-age-who-decides-what-information-is-trustworthy/ (accessed May 10, 2024).Suche in Google Scholar

Naeem, S. B., and R. Bhatti. 2020. “The Covid-19 ‘Infodemic’: A New Front for Information Professionals.” Health Information & Libraries Journal 37 (3): 233–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/hir.12311.Suche in Google Scholar

Nonaka, I., and K. Takeuchi. 1995. The Knowledge Creating Company. Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780195092691.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Obenauf, S. E. 2021. “Remote Management of Library Staff: Challenges and Practical Solutions.” The Journal of Academic Librarianship 47 (5): 102353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2021.102353.Suche in Google Scholar

Ocholla, D. N. 2021. “Echoes Down the Corridor. Experiences and Perspectives of Library and Information Science Education (LISE) During COVID-19 Through an African Lens.” Library Management 42 (4/5): 305–21. https://doi.org/10.1108/LM-02-2021-0016.Suche in Google Scholar

Ojobor, R. C. 2023. “Blockchain Technology for Library Services: Challenges and Opportunities for Libraries from a Nigerian Perspective.” In Information Services for a Sustainable Society: Current Developments in an Era of Information Disorder, edited by M. Fombad, C. Chisita, O. Onyancha, and M. Minishi-Majanja, 7–23. De Gruyter Saur.Suche in Google Scholar

Rafiq, S., M. Ashiq, S. U. Rehman, and F. Yousaf. 2021. “A Content Analysis of the Websites of the World’s Top 50 Universities in Medicine.” Science & Technology Libraries 40 (3): 260–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/0194262X.2021.1889446.Suche in Google Scholar

Ratkanthiwar, M. S., R. S. Lengure, P. A. T. Agashe, and U. G. Harde. 2024. “Use of Knowledge Management Tools for Collaborative Research and Learning in Academic Libraries.” Library of Progress – Library Science, Information Technology & Computer 44 (3). https://doi.org/10.48165/bapas.2024.44.2.1.Suche in Google Scholar

Rivera-Macias, B., and B. Casselden. 2024. “Researching Finnish Library Responses to Covid-19 Digital Literacy Challenges Through the Employment of Reflective Practice.” Journal of Librarianship and Information Science 56 (1): 98–119. https://doi.org/10.1177/09610006221130781.Suche in Google Scholar

Salubi, O. 2023. “Transforming Libraries and Information Professionals for the Industry 4.0 in Developing Countries: Towards the Development of a Framework for Accelerating Change Post-Covid-19.” Alexandria 35 (1–2). https://doi.org/10.1177/09557490231197971.Suche in Google Scholar