Kant’s Prize Essay and Nineteenth Century Formalism

-

Richard Lawrence

Abstract

Kant’s Prize Essay of 1764 emphasizes the importance for mathematical cognition of manipulating signs according to rules, which has led some recent commentators to ask whether Kant’s position there is a species of mathematical formalism. While most have hesitated to find formalism in the Prize Essay, this hesitation derives from misconceptions about what formalists actually believe. I therefore examine some nineteenth century formalists who were in dialogue with Kant, using their views as a model against which to compare the Prize Essay. I argue that Kant’s view in the Prize Essay is continuous with their formalism, since the Prize Essay shares the essential aspects of their views about the sign-signified relation in mathematics and the role of signs in mathematical reasoning.

1 Formalism and the Prize Essay

Mathematical formalism is a family of views that emphasizes the importance of signs in mathematical reasoning and knowledge. Formalism holds that in at least some parts of mathematics, the content of mathematical knowledge should be explained in terms of the manipulation of signs according to rules. A formalist explains our knowledge of complex numbers , for example, by pointing to the algebraic rules which govern them, and denies that we must ground their existence (say, by giving a geometrical interpretation) prior to laying down these rules. For the formalist, these rules determine the concept of complex number. By manipulating signs according to the rules, we arrive at new statements that constitute new mathematical knowledge about that concept. Thus mathematical knowledge can flow from rules for manipulating signs.

Kant at one point held a view that sounds like formalism, in a pre-Critical essay titled Inquiry concerning the distinctness of the principles of natural theology and morality (UD), known in the literature as the “Prize Essay” because it was submitted to (and nearly won) an essay contest from the Berlin Academy of Sciences in 1763. Kant writes there:

In both [arithmetic and algebra], there are posited first of all not things themselves but their signs, together with the special designations of their increase or decrease, their relations, etc. Thereafter, one operates with these signs according to easy and certain rules, by means of substitution, combination, subtraction and many kinds of transformation, so that the things signified are themselves completely forgotten in the process, until eventually, when the conclusion is drawn, the meaning of the symbolic conclusion is deciphered. (UD, AA 2:278)

Throughout the Prize Essay, Kant emphasizes the importance of signs in mathematics. As this passage shows, he thinks of manipulation of signs according to rules as the method by which we derive conclusions in arithmetic and algebra. He also argues that signs’ role as “sensible means to cognition” is responsible for the distinctive certainty of mathematical knowledge. This has led some recent commentators to ask whether Kant’s position in the Prize Essay is a species of formalism (Carson 1999, 2009; Dunlop 2014, 2020; Rechter 2006).

Most are hesitant to attribute an unqualified formalism to Kant. Carson, for example, thinks that Kant “obviously opposes” formalism, and only wants to claim that “more must be said to differentiate” the Prize Essay view from formalism than Kant actually says there (Carson 1999, 642 – 643). Dunlop on the other hand is willing to find formalism in the Prize Essay, but only “in a wider sense” (Dunlop 2014, 672).

One reason to be cautious about a formalist reading of the Prize Essay is that there are important parallels between Kant’s view there and his mature view in the Critique of Pure Reason, and it is natural to read the Prize Essay as a forerunner to the Critique. But in the Critique’s account of mathematical knowledge, Kant no longer emphasizes the importance of signs, and a formalist reading of his view is much less attractive. Thus interpreting the Prize Essay view as a species of formalism makes the question of how exactly it differs from the Critique especially pressing.

I would like here to shed light on the issue of whether and in what sense the Prize Essay defends a kind of formalism by taking an approach not explored in the literature so far. Formalism emerged in the mid-nineteenth century, and was an important view among German mathematicians, especially those working in real and complex analysis. These formalists were aware of Kant’s philosophy of mathematics, at least as expressed in the Critique, and sometimes explicitly invoke Kant to explain their own positions. We can use their understanding of formalism to interpret the Prize Essay: if we find Kant’s view in the Prize Essay to be relevantly similar to theirs, this is good reason to think of the Prize Essay as defending a formalist view. I will argue that there is indeed good reason to read the Prize Essay this way, thus agreeing with Dunlop, though on the basis of a different understanding of formalism. Likewise, we will see that the nineteenth century formalists explicitly rejected the strong role for intuition that Kant proposes in the Critique. This suggests that an interpretation in line with those of Guyer (1991) and Carson (1999) is broadly correct, on which the Critique view differs significantly from the Prize Essay precisely because it abandons the emphasis on signs in favor of intuition.

The nineteenth century formalists have often been misunderstood. This is largely due to the influence of critics like Frege and Weyl, who caricatured formalism as turning mathematics into a game of meaningless symbols. These criticisms have also shaped how interpreters of the Prize Essay understand formalism, which is another reason they have hesitated to attribute formalism to Kant. Before we can compare nineteenth century formalism to the view in the Prize Essay, we need a clearer view of this formalism, unencumbered by the misunderstandings such criticisms have introduced or by more modern versions of the view. Thus I will begin by setting out what I take to be the essential components of the formalist view in the nineteenth century. I will then argue that we can find these components in the Prize Essay, so that Kant’s view there can legitimately be interpreted as continuous with the formalism of the nineteenth century. I will close by examining how the later formalists reacted to the Critique, and reflecting on what this tells us about the Prize Essay view.

2 Formalism in nineteenth century mathematics

By the end of the nineteenth century, formalism was a widely held view among German mathematicians. Frege for example wrote at the end of his life that when he started his foundational investigations, he encountered formalism “in an apparently predominant position” (Frege 1997, 371). Already in 1884 he had described it as “widely-held” (Frege 1884/1980, xxii). In an attempt to clear the way for his own logicist program, Frege devoted long passages to critiquing “formal arithmetic” throughout his career[1], and was exasperated that his criticisms fell on deaf ears. Although we have mostly lost sight of this view today, due to both Frege’s influence in philosophy and wider changes in mathematics, we should keep in mind that formalism enjoyed widespread support among mathematicians of the time. It was not a simplistic view, and even Frege’s sophisticated arguments failed to diminish its popularity.

I shall focus here on two of Frege’s formalist interlocutors, Hermann Hankel and Johannes Thomae, to outline the formalist position. Both are prominent formalists whose views were (and are still) actively discussed.[2] Their view is relatively explicit and well developed. Moreover, both use Kantian language and explicitly invoke Kant—as authority and as foil. Gottfried Martin has also shown that there is a line of influence from Kant to Hankel, by way of Johann Schultz, Martin Ohm, and Hermann Grassmann (Martin 1985, ch. 3).[3] This line of influence extends to Thomae as well, since Thomae took himself to be following Hankel (Thomae 1908). Thus we have a reasonably clear view of their relation to Kant’s philosophy of mathematics, so it makes sense to take their formalism as a model to compare against the Prize Essay. I will limit my discussion here to the aspects of their view which are relevant for that comparison.

It makes less sense to compare Kant with Hilbert here, although Hilbert’s formalism is better known and the most widely discussed.[4] Hilbert’s formalism arises from his proof-theoretic program for the foundations of mathematics, developed throughout the 1920s. Although that program also has important connections to Kant, it is more difficult to get those connections in view: mathematics was so different by the 1920s that Kant would hardly have recognized it. In particular, Hilbert’s proof-theoretic work took place after the transition to the new logic developed by Frege, Russell, Peano, and others, in a context that had already accepted the idea of a formal language: a logical language whose symbols could be given different interpretations. Indeed, Hilbert’s own work helped initiate this transition. Because Hankel and Thomae were writing before this transition, their view of mathematics is more directly comparable with Kant’s. It is useful, specifically, to compare their view of signs with Kant’s in the Prize Essay, since both occur in a context which did not conceive of signs as symbols in a formal language.

In fact, one of the noteworthy features of the earlier formalists’ discussion of signs is that they do not seem to think of them as part of a language at all. Although they speak often of signs and afford them a special role in mathematics, they never mention language, and do not think of the relationship between sign and signified in linguistic terms. In this respect they differ both from the British algebraists, who followed Berkeley in seeing algebraic symbolism as a sort of language, and from Frege, whose goal was to develop a logical language, a Begriffsschrift, sufficient for defining the concepts of mathematics in purely logical terms. The fact that the nineteenth century formalists do not speak of signs in connection with language at all, despite notable discussions of language in their British predecessors and German contemporaries, is our first clue that they understand signs in a different, non-linguistic sense, which I will argue we also find in the Prize Essay.

Frege, by contrast, clearly does think of signs as forming a language, and his linguistic conception of signs can be a source of misunderstandings that we should avoid here. For Frege, signs are concrete, perceptible items that are written down or spoken:

What are signs? I will restrict my attention to formations that are created by means of writing or printing on the surface of a physical object (blackboard, paper); for clearly it is only these that are intended when the numbers are termed signs. (Frege 1903/2013, §98)

Frege presupposes throughout his discussions of formalism that signs are concrete, but this contradicts many things the formalists actually say. Thomae, for example, calls the infinite decimal expansions of real numbers “signs”:

An infinite decimal, a decimal with infinitely many places…is an abbreviation, a sign for an infinite sequence of the usual finite decimals, or a sign which is assigned to such a sequence. (Thomae 1898, 5 – 6)

This implies that signs are not something we could hope to write down or say aloud, but rather something more abstract. Hankel makes claims with similar implications: he conceives of signs, for example, as forming completed infinite systems (Hankel 1867, 35 – 36). Cantor[5] is even more explicit, almost directly claiming that signs are “abstract thought things”:

it has never been claimed, by me or anyone else, that the signs … are concrete magnitudes, in the proper sense of the word. As abstract thought-things (Gedankendinge) they are only magnitudes in an improper or derived sense of the word. (Cantor 1889, 476)

For the formalists, then, signs are something abstract, not concrete marks.

Frege also introduced the misconception that for the formalists, signs do not signify or mean anything. Frege says, for example, that “in formal arithmetic…[signs] are not supposed to signify (bezeichnen) something else; rather they are themselves the object of concern” (Frege 1903/2013, §100, translation slightly adapted). This is the point Frege finds most objectionable about formal arithmetic: for Frege, if we do not think of signs in arithmetic as signifying or meaning something, then arithmetic has no content, contains no truths, and cannot be considered a science.

But here again, Frege’s characterization of formalism contradicts what formalists actually say. Hankel insists, for example, that “a sign must signify something” (Hankel 1867, 14), and attributes not just one, but two kinds of meaning to signs: signs have a “formal” meaning (formale Bedeutung), given by laying down rules of calculation, and sometimes an “actual” meaning (actuelle Bedeutung) as well, which is essentially a presentation of their formal meaning in intuition (Hankel 1867, 70, 8). Thomae inherits this distinction from Hankel, speaking of empirical applications of numbers as having additional meaning which goes beyond their purely formal meaning (Thomae 1898, 3 – 4). It is thus incorrect to say that on the formalist view, signs do not signify anything, or have no meaning or content.

This misconception is particularly important to clear up here, because it has shaped the existing debate about formalism in the Prize Essay. Dunlop and Rechter, for example, using language that goes back to Parsons (1969/1992), frame the issue of formalism in the Prize Essay by asking whether mathematical signs have “reference”. This is because they understand formalism as a position on which signs have no reference, merely refer to themselves, or are “non-representational” in some other sense. The problem with this framing is that our notion of reference stems from Frege’s technical concept of Bedeutung and is loaded with the baggage of his understanding of it. If we understand reference as Frege did, then it is probably true that the formalists’ signs have no reference. But this is unsurprising, even trivial. For Frege, it was totally clear that the formalists’ signs have no reference, in his technical sense of that word; indeed, he developed that technical sense partly in order to argue that formalism was untenable.

To ask whether signs have reference, either for Kant or for the nineteenth century formalists, is therefore to bias the issue toward Frege’s negative conclusion. It would be better to simply ask whether signs signify something on the formalist view, leaving open whether the sign-signified relation might be a different representational relationship than that of linguistic reference. As we have just seen, the formalists explicitly claim that signs do signify something. They hold that signs have meaning, that they are signs for something else, and thus that there is a representational relationship between sign and signified.

Here we come to a puzzle, though. As Frege would be the first to point out, the formalists are in the habit of saying that signs are “empty”. Thomae for example, in an oft-quoted passage, writes that

for the formal conception, arithmetic is a game with signs which one may well call empty, thereby conveying that (in the calculating game) they do not have any content except that which is attributed to them with respect to their behavior under certain combinatorial rules (game rules). (Thomae 1898, 3)

Hankel similarly speaks of “pure” signs, “empty” systems of signs, and numbers which are “empty of content” (inhaltsleer) and “purely abstract forms” (Hankel 1867, 8, 11, 47). Don’t such remarks support Frege’s interpretation that for the formalists, mathematical signs don’t signify anything, and mathematics is not a science, but a meaningless game? If the formalists believe that signs signify something, or have meaning or content, why do they make such remarks?

I will return to this question in more detail below, in connection with the Critique. For now, it suffices to answer that for both Hankel and Thomae, the point of claims like this is to deny that signs must represent geometrical or empirical quantities. By calling signs “empty”, the formalists are insisting on the independence of formal arithmetic from its potential applications to quantities given in pure or empirical intuition: signs can have meaning even without such applications. The formalists’ claim that signs are “empty” thus does not contradict the claim that signs signify; instead, it is a way of distinguishing signs’ meaning or significance from the quantities to which they apply.

This distinction between meaning and application runs parallel to Kant’s later distinction between concepts and intuitions. For the formalists, numbers and arithmetic apply to quantities given in intuition; but the meaning of arithmetical signs is conceptual, and determined by a definition. They think of such definitions as being given by laying down the rules which govern arithmetical operations. Thomae for example writes

Insofar as the content of the concept for which the infinite decimal is a sign is completely exhausted in arithmetic by the fact that the behavior of this sign is determined with respect to the rules of calculation…this concept is to be called formal (Thomae 1898, 5 – 6)

Here Thomae is explicit that a “sign” is a sign for a concept. It is thus representational, and has a content. But that content is “formal” because that concept is of a certain kind: namely, one completely determined by the rules for calculation. Hankel associates the formal with the conceptual in a similar way, and says that signs “receive their formal meaning only through our laying down the rules according to which they can be operated with” (Hankel 1867, 70). The rules they have in mind are the laws which govern the arithmetical operations: for example, the commutativity of addition () or the distributivity of multiplication over addition (). Hankel likewise says that with these laws one has “exhausted the fundamental properties [of addition and multiplication] and at the same time given their formal definition” (Hankel 1867, 3).

To understand what is going on here, it helps to know a bit more about the formalists’ mathematical goals. In general, they are aiming to construct higher-order number systems, such as the real or complex numbers. They think of the rules of calculation as fixing the arithmetical relations in a whole system of numbers, and in that sense “determining the concept” of such a number system. They are giving such constructions without the aid of modern set theory or logic, so their approach is to build a higher-order number system by starting from a lower-order one, defining the arithmetical operations for the new higher-order numbers in terms of the operations given on the lower-order one. Thomae’s construction of the real numbers, for example, proceeds by defining what it means to add, subtract, multiply and divide certain infinite sequences of rational numbers, presupposing definitions of the arithmetical operations on rational numbers themselves. One can then prove that those sequences of rationals, under these definitions of the arithmetical operations, form a structure which (as we would now put it) is isomorphic to the real number field.

How does such a construction determine the concepts signified by individual number signs, that is, signs for particular numbers? The formalists do not concern themselves much with this question, in part because they are focused on real and complex analysis, where functions, not particular numbers, are the main object of study. The best formulation we can give on their behalf is that each individual number is determined by its arithmetical relations to all the others—by its place in the whole system of numbers which the rules define. The number signified by , say, is that number such that

and so on ad infinitum. By laying down the rules which govern the arithmetical operations for the whole domain, we fix the relations between this number and all the others, and thereby determine the concept signified by . As Hankel puts it,

I call the signs of such a system numbers, and thus set their concept in a necessary context with the operations through which they are formed and pass into one another. Every change of the operations brings a change of the numbers with it. (Hankel 1867, 35)

In modern terminology, the nineteenth century formalists thus have a basically structuralist approach to defining different number systems. Their constructions are based on the idea that we can define the concept of a whole number system by defining arithmetical operations on some system of objects, then abstracting from or ignoring the non-arithmetical features of those objects and focusing on the arithmetical structure which the definitions induce on them. Such a definition determines the concept of that whole number system, and thereby the concepts of each of the numbers in it. Although they speak about “concepts” rather than “structures” and “signs” rather than the “positions” or “offices” in the structure, their position is similar to modern structuralism. This is significant because some interpreters, especially those influenced by Parsons (1969/1992), also find a structuralist view in Kant’s philosophy of arithmetic. In particular, Rechter (2006) sees such structuralism already in the Prize Essay, as I will discuss below.

A final point is worth emphasizing for purposes of comparison with Kant’s view in the Prize Essay. The formalists hold that the rules which define such a number system and the individual numbers within it are arbitrary; we are free to lay down whatever rules we like. Hankel gives the clearest expression of this position:

How we define the rules of purely formal operations (Verknüpfungen), i. e., of carrying out operations (Operationen) with mental objects, is our arbitrary choice (steht in unserer Willkühr), except that one essential condition must be adhered to: namely that no logical contradiction may be implied in these same rules. (Hankel 1867, 10)

For Hankel, the rules are thus subject to the principle of contradiction, but this is the only constraint: “the mathematician counts as impossible in the strict sense only what is logically impossible, i. e., what is self-contradictory” (Hankel 1867, 6).[6] Hankel acknowledges that there is a further question about whether a number system given by such an arbitrary definition can find a “substrate” or “make their appearance in” intuitively-given objects (Hankel 1867, 7). But no such substrate is necessary to define or investigate that number system. In formal arithmetic, we are free to define arbitrary number concepts, subject only to the principle of contradiction.

In summary, then, for the formalists, “signs” signify, or are signs for, individual number concepts. Although they speak of signs and insist that they signify, the formalists do not think of the sign-signified relation in linguistic terms: signs are not concrete marks which refer to concepts. Signs are abstract and present concepts in a non-linguistic manner. The contents of those concepts are determined, and exhausted, by the rules governing arithmetical operations in a complete number system, because these rules determine the arithmetical structure of that system. We are free to define different number systems by laying down different rules, so long as those rules are consistent. In particular, it is not required that the numbers in such a system are applicable to quantities given in (pure or empirical) intuition. The investigation of such arbitrarily-defined systems is a legitimate mathematical activity independent of whether any such applications are possible.

3 Formalism in the Prize Essay

Does Kant defend a version of formalism in the Prize Essay? Given the interpretation of formalism above, there are good reasons to say that he does. The Prize Essay articulates a view of mathematics on which it consists of a practice of presenting arbitrarily-defined concepts in signs, manipulating those signs according to rules, and drawing conclusions about those concepts from the results of those manipulations. Moreover, the Prize Essay argues, this detour through signs is an important part of the mathematical method, and helps explain the unique certainty of mathematical reasoning. As we will see, this view agrees in essentials with that of the nineteenth century formalists. Indeed, comparing the two illuminates both views. The discussion above will help us identify a species of formalism in the Prize Essay; at the same time, the Prize Essay helps explain why later mathematicians may have found formalism attractive.

The main question which the Prize Essay seeks to answer was “whether metaphysical truths in general… are capable of the same clear proof as geometrical truths” (Guyer 1991, 119). Kant took a broad view of the question, considering in his answer not just geometry but also arithmetic and algebra, seeking to explain why reasoning in all three branches of mathematics admits of greater certainty than metaphysical reasoning. His explanation highlights two related features of mathematical reasoning: first, the unique way in which signs present concepts in mathematics, and second, the unique freedom we have in mathematics to define those concepts. Both features are absent in metaphysical reasoning; and both align with a formalist view.

Let us focus first on the way signs work in mathematics, in contrast to metaphysics and philosophy. Kant writes:

If the procedure of philosophy is compared with that of geometry it becomes clear that they are completely different. The signs employed in philosophical reflection are never anything other than words. And words can neither show in their composition the constituent concepts of which the whole idea, indicated by a word, consists; nor are they capable of indicating in their combinations the relations of the philosophical thoughts to each other. Hence, in reflection in this kind of cognition, one is constrained to represent the universal in abstracto without being able to avail oneself of the important device which facilitates thought and which consists in handling individual signs rather than universal concepts of the things themselves. (UD, AA 2:278 – 279)

Kant claims here that the signs in philosophy are words. Words indicate “ideas”, which are composed of concepts. So in philosophy at least, signs represent concepts. Although Kant does not say so directly here, it is clear that he also thinks of signs in mathematics as signifying or representing concepts, as words do in philosophy.[7] Indeed, the whole argument of the Prize Essay presupposes this view.

The difference between mathematics and philosophy lies not in what their signs signify, but in how they signify. The difficulty in philosophy is that signs “can neither show in their composition” nor “in their combinations” concepts and the relations between them in thoughts. In language, signs tell us nothing about the structure or relations of the concepts they signify. For this reason, Kant thinks, we have to strain in philosophy to look past the signs and work with the concepts themselves (“in abstracto”), to discover their structure and keep it constantly present in mind.

In mathematics, by contrast, “handling individual signs” is a “device which facilitates thought”. Kant implies here that mathematical signs have a different sort of representational relationship to concepts than words do. In contrast to words, mathematical signs apparently do show us the structure and relations of the concepts they signify. To express this idea, I will say that mathematical signs are transparent. The transparent nature of signs in mathematics allows us to work with the signs themselves in reasoning, instead of always having to focus on the concepts they signify.

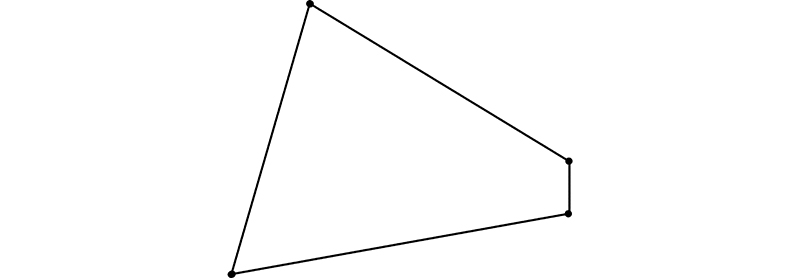

To see how this can be, it helps to focus initially on geometric diagrams, which are Kant’s primary model of how signs function in mathematical reasoning. Consider Kant’s example of the definition of a trapezium: a figure with four straight sides bounding a plane surface so that the opposite sides are not parallel to each other (UD, AA 2:276). Now consider a diagram of a trapezium, like this:

One can see in the diagram that the figure has four sides, that the sides are straight, that they bound a plane surface, and that opposing sides are not parallel. The diagram presents the concept of a trapezium by presenting all and only the characteristic marks of that concept in spatial relation to one another, as properties of a single figure. Because the diagram presents everything relevant about the concept of a trapezium, we can use it as a stand in for the concept itself in reasoning. That is, we can manipulate the diagram in certain ways, and so long as our manipulations follow the rules for manipulating geometric diagrams, the conclusions we draw will hold for all trapezia.

We may conclude from this that in geometry at least, Kant shares the basic view of the nineteenth century formalists about the nature of signs in mathematics: they are abstract representations which signify concepts in a transparent, non-linguistic fashion. While the formalists merely fail to discuss language, Kant expressly contrasts the way words signify concepts in language with the way signs present concepts in mathematics. The case of geometric diagrams makes the contrast sharp: in a geometric diagram, concepts are presented in a way that is clearly different from the way they are presented in language. A diagram of a trapezium is a sign which shows us much more about the structure of the concept of trapezium than the word “trapezium” does. If it does not seem obvious that a diagram is an abstract representation, keep in mind that the same diagram can be, say, drawn on a chalkboard and printed in a textbook. That is, the diagram is a type, not a concrete, physical token; and I argued above that for the formalists, signs cannot be concrete physical tokens, and are abstract at least in that sense.

What about signs in arithmetic and algebra, though? Is it clear that they, too, signify concepts in a non-linguistic fashion, as geometric diagrams do? Kant does distinguish the way that geometric and algebraic signs signify: he writes that “in geometry, the signs are similar to the things signified, so that the certainty of geometry is even greater, though the certainty of algebra is no less reliable” (UD, AA 2:292). He implies here that the representational relationship of algebraic signs to what they signify is different from the relationship of similarity found in geometry. But this does not immediately imply that in algebra, the sign-signified relationship is a linguistic one. As Kant stresses here, manipulation of signs in algebra still provides for certainty in algebraic reasoning. In this respect, signs in arithmetic and algebra are more akin to geometric diagrams for Kant than to words in philosophy. The signs of arithmetic and algebra still present concepts to us in a way that “facilitates thought” and admits of certainty, even though they don’t do this by being similar to what they signify.

Kant’s brief comments in the Prize Essay about the sign-signified relation in arithmetic and algebra leave much open to interpretation; the most illuminating interpretation I am aware of is Ofra Rechter’s (Rechter 2006). Drawing on notes from Kant’s mathematics lectures contemporaneous with the Prize Essay, Rechter argues that Kant was impressed by the generative character of our decimal notation for numbers and our grade-school algorithms for performing calculations in that notation. These algorithms in effect set up an isomorphism between calculations we make in decimal notation and arithmetic operations on natural numbers. This leads Rechter to a structuralist reading of Kant’s view of arithmetic, on which the system of decimal notation presents the conceptual structure of the natural number system to us not by being similar to it, but by modeling it: by exemplifying or instantiating the positions and relations in that structure in a particular system of signs (Rechter 2006, 38). In virtue of the rules governing the generation of numerals, each individual numeral determines not just which number concept it signifies, but its position in the structure relative to all the others. So unlike a language, where we must learn the connections between words and concepts individually, a numeral system links each number sign to a number concept via a set of general rules. We have here then a third sort of sign-signified relationship, distinct from the relation words bear to concepts in language, but also from the relation Kant calls “similarity” in geometry.

One limitation of Rechter’s interpretation is that she does not extend this view beyond elementary arithmetic. Kant intends his view to also cover reasoning in algebra, which he assimilates to reasoning in arithmetic. Kant views algebra as a species of arithmetic, and writes that “in both kinds of arithmetic”—that is, both “the arithmetic of numbers” and algebra, the “general arithmetic of indeterminate magnitudes”— “there are posited first of all not things themselves but their signs”. He then gives a single description of how reasoning in those disciplines proceeds: “one operates with these signs according to easy and certain rules, by means of substitution, combination, subtraction and many kinds of transformation” (UD, AA 2:278).

In light of this assimilation of arithmetic and algebra, we should not over-emphasize the role of numerals and school arithmetic in Kant’s view. To interpret Kant’s description as applying to algebra, we will have to conceive of signs more abstractly than as numeral strings, for example by thinking of infinite decimals or certain geometric magnitudes as signs for irrational quantities. To accommodate algebraic variables, we will also have to acknowledge that some signs do not correspond to a single determinate quantity, and that the “easy and certain rules” Kant mentions include, beyond school algorithms for calculation, the laws governing the arithmetic operations. These too can be understood as rules for manipulating signs. The law of distribution of multiplication over addition, for example,

can be viewed as a rule which permits substituting a sign of the form with a sign of the form , or vice versa. An application of this rule permits exchanging, say, for when solving an algebra problem.

It is exactly those general laws governing the arithmetic operations which the nineteenth century formalists think of as determining the structure of a whole system of numbers, and thus concepts like real number or complex number. So if we assume Rechter’s structuralist reading is on the right track, and extend that reading to cover Kant’s view of algebra as well, the resulting view is continuous with nineteenth century formalism. Both Kant and the formalists take a complete system of signs to play an essential role in our knowledge of a given number domain. This system is structured by the rules governing operations with those signs. Because the rules guarantee a correspondence between signs and the concepts they signify, manipulation of signs in this system is a means to obtaining knowledge about those concepts.

The Prize Essay further argues that the greater certainty of mathematical knowledge stems from the distinctive representational relationship between mathematical signs and what they signify:

mathematics, in its inferences and proofs, regards its universal knowledge under signs in concreto, whereas philosophy always regards its universal knowledge in abstracto, as existing alongside signs. And this constitutes a substantial difference in the way in which the two inquiries attain to certainty. For since signs in mathematics are sensible means to cognition, it follows that one can know that no concept has been overlooked, and that each particular equation[8] (Vergleichung) has been drawn in accordance with easily observed rules etc. And these things can be known with the degree of assurance characteristic of seeing something with one’s own eyes. (UD, AA 2:291)

Kant’s idea is evidently that, because mathematical signs present concepts to us in a transparent manner, we are able to verify that thoughts and inferences represented with those signs are correct. We can see, in a more or less literal sense, that mathematical reasoning proceeds correctly, since it takes place by means of a system of signs governed by rules, and those signs present everything relevant about the concepts they signify.

This explanation of the certainty of mathematical reasoning depends on another thesis of the Prize Essay, namely, that mathematical concepts are given by arbitrary definitions. In mathematics, “the concept which I am defining is not given prior to the definition itself; on the contrary, it only comes into existence as a result of that definition” (UD, AA 2:276). Kant emphasizes this point numerous times in the Prize Essay, stressing that a mathematical concept is defined “by means of an arbitrary combination” of concepts and “only comes into existence as a result of the definition” (UD, AA 2:280 – 281). The act of defining creates mathematical concepts, and a mathematician is free to define whatever concept she likes. Because mathematical concepts are given by arbitrary definitions, we know exactly what belongs to them and what does not. That is what makes it possible to set up a system of signs which present all, and only, the relevant features of those concepts, and rules for manipulating those signs which allow us to draw correct inferences about the concepts with certainty.

To make this concrete, consider again the diagram of a trapezium above. It is easy to verify that the figure in the diagram is a representation of a trapezium because, as we already observed, you can see that it exhibits each of the concept’s characteristic marks. But it also important that you don’t need to look for anything else. The concept of a trapezium has no other marks than the ones which the definition explicitly puts into it. Thus, as Kant says, we can know that “no concept has been overlooked” in the diagram: because the concept is created by an arbitrary definition, we know that there are no ‘hidden’ parts of the concept which might only be discovered by further analysis and which are not exhibited in the figure. It is possible to draw conclusions about trapezia by reasoning with the diagram precisely because that concept is given by an arbitrary definition.

The same is true for arithmetic and algebraic signs, though because the sign-signified relationship is different there, we have to understand Kant’s idea that “no concept is overlooked” differently. An arithmetical sign does not present the concept of an individual number in the same way that a diagram presents the concept of a trapezium, exhibiting each of the marks of the concept as features in spatial relation to one another. Instead, it presents an individual number concept in virtue of the rules governing a whole system of signs, which set up a correspondence between those signs and number concepts. But here too, the arbitrariness of the definition of the whole system ensures that the system of signs presents all the relevant features of the concepts they signify. For suppose it were possible that the concepts we signify with, say, 24 and 57 have some hidden features not fixed by the definition which imply that . If that were possible, then our ‘definition’ of the natural numbers might not only fail to capture facts about these numbers, but actually be inconsistent with such facts. So unless the definition completely determines the arithmetical relations of these concepts, it cannot provide certain knowledge of arithmetic at all.

As Katherine Dunlop has observed, Kant shares the thesis that mathematical concepts are given by arbitrary definitions with formalism “in a wider sense”, and she attributes a species of formalism to him on this basis (Dunlop 2014, 672; 2020). In fact, Kant’s explanation of mathematical certainty comes particularly close to the nineteenth century formalists here, confirming this diagnosis. As we saw above, the formalists explicitly claim that mathematical concepts are given by arbitrary definitions, and specifically, by laying down rules for calculating with signs. Recall that they also emphasize that these rules of calculation exhaust the definitions of number concepts. This is just another way of saying that number concepts contain all, and only, what we put into them: when we define them by laying down rules of calculation, we determine everything relevant about them in mathematics. While the formalists say little to justify this view, Kant’s claim in the Prize Essay is that this is not only a distinguishing feature of mathematical definitions, but the ground of mathematical certainty. In this respect, the Prize Essay helps make sense of their view: mathematical concepts must be completely given by arbitrary definitions because that is what ensures the certainty of the conclusions we draw about them by means of the manipulation of signs.

We have thus found, in essentials, the same role for signs in mathematics in Kant’s Prize Essay as in the nineteenth century formalists. The signs of the Prize Essay signify concepts. In both geometry and algebra, this sign-signified relation is a transparent, non-linguistic relationship, very different from the relationship between words and philosophical concepts. Signs can present mathematical concepts in this transparent manner because mathematical concepts are completely determined by arbitrary definitions. And Kant, in contrast to the formalists, gives us a reason why they must be defined arbitrarily: that arbitrariness is the ground of mathematics’ unique certainty.

This continuity between the Prize Essay and later formalism was perhaps to be expected. As Guyer (1991) and Dunlop (2014) have shown, Kant’s view in the Prize Essay drew heavily from the understanding of mathematics in Leibniz and Wolff, who had also emphasized the importance of signs in mathematical cognition. Kant himself made a break with that tradition in the Critique, but it shouldn’t be surprising if it continued to have an influence on German mathematics even after Kant.[9] Seen from this perspective, the Prize Essay and nineteenth century formalism belong to the same continuing stream of thought; it was the Critique which branched off in a new direction. The nineteenth century formalists were conscious of this, and explicitly formulated their view in opposition to the Critique. Let me close by examining that aspect of their view in more detail.

4 The Critique and the formalists’ rejection of intuition

In the Critique of Pure Reason, Kant does not entirely abandon the idea that signs are important in mathematical cognition, but he no longer emphasizes their importance as he did in the Prize Essay. Instead, his new doctrine of pure intuition takes over much of the theoretical role that signs played in the earlier work. For Kant in the Critique, mathematical cognition is based on the construction of concepts in intuition. Both geometric and algebraic reasoning are seen primarily in terms of such constructions. Although Kant thinks of algebraic reasoning as proceeding by “symbolic” construction, which “displays by signs in intuition the concepts”, it is the notion of construction, not signs themselves, which plays the primary explanatory role.

Carson (1999) has offered an explanation of this shift in Kant’s view, arguing that the doctrine of pure intuition in the Critique closes a gap Kant sees in his position in the Prize Essay. The problem is that, if we are free to simply create mathematical concepts via arbitrary definitions as the Prize Essay suggests, then those concepts need not have any “objective reality”, and are epistemologically no better than arbitrarily invented metaphysical concepts like that of a slumbering monad. The doctrine of pure intuition, Carson argues, solves this problem. It provides a constraint on which concepts we can define in mathematics, and thereby secures the objectivity of mathematical knowledge. The concepts we can legitimately define are those constructible in pure intuition. This distinguishes the concept of a trapezium both from metaphysical fictions like slumbering monad and from mathematical impossibilities like figure enclosed by two straight lines.

Carson’s reading is supported by passages like this one in the Critique, where Kant, writing about principles like “between two points there can be only one straight line”, claims that:

they would still not signify anything at all if we could not always exhibit their significance in appearances (empirical objects). Hence it is also requisite for one to make an abstract concept sensible, i. e., display the object that corresponds to it in intuition, since without this the concept would remain (as one says) without sense, i. e., without significance (ohne Bedeutung). Mathematics fulfills this requirement by means of the construction of the figure, which is an appearance present to the senses (even though brought about a priori). (KrV, A239 – 40/B298 – 99)

Here we see that by insisting that mathematical concepts must be constructible in intuition, Kant intends to ensure that they are applicable to empirical reality. If we cannot “exhibit their significance in appearances”, and specifically in “empirical objects”, then those concepts are “without sense” and “without significance”.

The nineteenth century formalists were familiar with Kant’s view in the Critique, and it is precisely this part of his view that they reject. They expressly deny that mathematical concepts must be presented in intuition in order to be significant. Hankel states that his goal is to establish “a purely intellectual mathematics detached from all intuition, a pure theory of form” (Hankel 1867, 9). He says that the numbers of formal arithmetic are “not constructible in intuition” and are to be distinguished from actual magnitudes:

To avoid all unclarity of the concepts, which so easily arises from the indeterminateness of application, one does well to call such numbers—the concept of which is completely determinate, but which are not capable of any construction in intuition—transcendent, purely mental, purely intellectual or purely formal, in contrast to the actual (actuelle) numbers which find their representation in the theory of actual (wirklichen) magnitudes and their combination. (Hankel 1867, 7)

In formal arithmetic, we operate with “intellectual objects, thought-things, to which actual objects or relations of such objects can, but need not, correspond” (Hankel 1867, 9). Thomae likewise emphasizes that “the formal conception of number” is “free…of relations to objects of the senses”, that further “axioms” are needed to relate the numbers of formal arithmetic to “intuitive manifolds”, and that it is precisely when applying numbers to “given manifolds” that “metaphysical difficulties” arise. For Thomae, the formal standpoint “lifts us beyond” all such difficulties; that is what we gain by adopting it (Thomae 1898, 3 – 4).

As I already suggested above, the formalists are insisting in these passages that there is a legitimate conception of number which is independent of possible applications of number in experience. According to this formal conception, number is something conceptual rather than intuitive, and signs can present such formal number concepts even if they do not correspond to any intuitively-given quantity. This is why they call signs “empty”: by this they mean that signs have no intuitive content, not that they have no content at all. Signs can have a formale Bedeutung prior to, and independent of, any construction in intuition. They still allow that such construction is possible, and important for applications of number systems; but they reject the Critique’s constraint that mathematical concepts are ohne Bedeutung unless they are constructible in intuition.

The formalists had good reasons for rejecting this constraint. The mathematical developments of the nineteenth century made it necessary to develop a more abstract conception of number, not tied to intuitive representations. Both Hankel and Thomae expressed their formalism in textbooks that dealt with the complex number field, and wanted to head off metaphysical objections to “imaginary” numbers, such as that no such numbers are given in intuition. (Hankel’s book also dealt with “alternating” numbers and quaternions, two even more exotic species of numbers with no obvious representation in intuition.) Both were also writing in a context where it was no longer considered rigorous to rely on geometric intuition as an explanation of continuity of the real line and of functions on the real numbers. In this context, Kant’s demand that number concepts have applications in intuition represented a severe restriction on the development of real and (especially) complex analysis.

Obviously, Kant’s position in the Prize Essay is not based on an explicit rejection of the doctrine of intuition in the Critique, nor on the needs of nineteenth century mathematics. But if the Critique attempted to fill a gap in the Prize Essay view by constraining mathematical definitions to concepts which can be constructed and applied in intuition, then by rejecting that constraint, the later formalists were steering back toward the view of the Prize Essay. This is yet another reason to characterize the Prize Essay as aligned with nineteenth century formalism, albeit a more indirect one.

So nineteenth century formalism consciously rejected a central way in which the Critique went beyond the Prize Essay. But it shares most of the Prize Essay’s understanding of the nature of mathematical signs and their role in mathematical cognition. The overlap is significant enough, I think, to call the Prize Essay view a genuinely formalist one, and not merely formalist in an attenuated or wider sense. In particular, we should not hesitate to find formalism in the Prize Essay out of a mistaken belief that signs have no reference or representational content on a formalist view. While some formalists may hold this, neither Kant nor his closest formalist successors did. Instead, formalism as they understood and defended it was based on the idea that signs represent mathematical concepts in a special, transparent way, intimately related to mathematicians’ freedom to define arbitrary number systems, independent of their possible applications.

This research was supported by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) grant ESP 211-G.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Anna Bellomo, Ofra Rechter, Alan Weir, audiences in Prague, Vienna, and Berlin, and two anonymous reviewers for discussion and feedback.

References

All translations are quoted from The Cambridge Edition of the Works of Immanuel Kant (1996) and the quotation rules followed are those established by the Akademie-Ausgabe (AA). Kant, Immanuel (1900 ff): Gesammelte Schriften. Hrsg.: Bd. 1 – 22 Preußische Akademie der Wissenschaften, Bd. 23 Deutsche Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin, ab Bd. 24 Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen. Berlin.

Cantor, Georg (1872). Ueber die Ausdehnung eines Satzes aus der Theorie der trigonometrischen Reihen. Mathematische Annalen, 5, 123 – 133.10.1007/BF01446327Suche in Google Scholar

Cantor, Georg (1889). Bemerkung mit Bezug auf den Aufsatz: Zur Weierstrass’-Cantor’schen Theorie der Irrationalzahlen in Math. Annalen Bd. XXXIII, p. 154. Mathematische Annalen, 33, 476.10.1007/BF01443973Suche in Google Scholar

Carson, Emily (1999). Kant on the Method of Mathematics. Journal of the History of Philosophy, 37(4), 629 – 652.10.1353/hph.2008.0905Suche in Google Scholar

Carson, Emily (2009). Hintikka on Kant’s mathematical method. Revue internationale de philosophie, 250(4), 435 – 449.10.3917/rip.250.0435Suche in Google Scholar

Dathe, Uwe (1997). Gottlob Frege und Johannes Thomae. In Gottfried Gabriel and Wolfgang Kienzler (eds.), Frege in Jena: Beiträge zur Spurensicherung, Vol. 2. Würzburg: Königshausen & Neumann, 87 – 103.Suche in Google Scholar

Detlefsen, Michael (2005). Formalism. In Stewart Shapiro (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 236 – 317.10.1093/0195148770.003.0008Suche in Google Scholar

Dunlop, Katherine (2014). Arbitrary combination and the use of signs in mathematics: Kant’s 1763 Prize Essay and its Wolffian background. Canadian Journal of Philosophy, 44(5 – 6), 658 – 685.10.1080/00455091.2014.967738Suche in Google Scholar

Dunlop, Katherine (2020). Kant and Mendelssohn on the Use of Signs in Mathematics. In Carl Posy and Ofra Rechter (eds.), Kant’s Philosophy of Mathematics: Volume 1: The Critical Philosophy and its Roots, Vol. 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 15 – 34.Suche in Google Scholar

Epple, Moritz (2003). The End of the Science of Quantity: Foundations of Analysis, 1860 – 1910. In Hans Niels Jahnke (ed.), A History of Analysis. Providence, Rhode Island: American Mathematical Society, 291 – 323.10.1090/hmath/024/10Suche in Google Scholar

Frege, Gottlob (1980). The Foundations of Arithmetic (Second; J.L. Austin, Trans.). Evanston, Illinois: Northwestern University Press. (Original work published 1884)Suche in Google Scholar

Frege, Gottlob (1984). On formal theories of arithmetic. In Brian McGuiness (ed.), Collected Papers on Mathematics, Logic and Philosophy (112 – 121). Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 112 – 121.Suche in Google Scholar

Frege, Gottlob (1997). Numbers and arithmetic. In Michael Beaney (ed.), The Frege Reader. Oxford: Blackwell, 371 – 373.Suche in Google Scholar

Frege, Gottlob (2013). Basic Laws of Arithmetic (Vol. 2; P. A. Ebert and M. Rossberg (eds.)). Oxford: Oxford University Press. (Original work published 1903)Suche in Google Scholar

Guyer, Paul (1991). Mendelssohn and Kant: One Source of the Critical Philosophy. Philosophical Topics, 19(1), 119 – 152.10.5840/philtopics199119113Suche in Google Scholar

Hankel, Hermann (1867). Vorlesungen über die complexen Zahlen und ihre Functionen. Leipzig: Leopold Voss.10.1515/crll.1867.67.200Suche in Google Scholar

Hartimo, Mirja Helena (2007). Towards completeness: Husserl on theories of manifolds 1890 – 1901. Synthese, 156(2), 281 – 310.10.1007/s11229-006-0008-ySuche in Google Scholar

Hartimo, Mirja, and Mitsuhiro Okada (2016). Syntactic reduction in Husserl’s early phenomenology of arithmetic. Synthese, 193(3), 937 – 969.10.1007/s11229-015-0779-0Suche in Google Scholar

Heine, E. (1872). Die Elemente der Functionenlehre. Journal für die reine und angewandte Mathematik, 74, 172 – 188.10.1515/crll.1872.74.172Suche in Google Scholar

Kant, Immanuel (1838). Immanuel Kant’s sämmtliche Werke (Vol. 1; K. Rosenkranz and F. W. Schubert, Eds.). Leipzig: L. Voss.Suche in Google Scholar

Kant, Immanuel (1992). Inquiry concerning the distinctness of the principles of natural theology and morality, being an answer to the question proposed for consideration by the Berlin Royal Academy of Sciences for the year 1763. In David Walford & Ralf Meerbote (Eds.), Immanuel Kant: Theoretical Philosophy, 1755 – 1770 (243 – 275). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. (Original work published 1764)Suche in Google Scholar

Kant, Immanuel (1998). Critique of Pure Reason (P. Guyer & A. W. Wood, Eds.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. (Original work published 1781 – 1787)10.1017/CBO9780511804649Suche in Google Scholar

Lawrence, Richard (2021). Frege, Hankel, and Formalism in the Foundations. Journal for the History of Analytical Philosophy, 9(11).10.15173/jhap.v9i11.5007Suche in Google Scholar

Lawrence, Richard (2023). Frege, Thomae, and Formalism: Shifting Perspectives. Journal for the History of Analytical Philosophy, 11(2).10.15173/jhap.v11i2.5366Suche in Google Scholar

Martin, Gottfried (1985). Arithmetic and Combinatorics: Kant and his Contemporaries (J. Wubnig, ed.). Carbondale, Illinois: Southern Illinois University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Parsons, Charles (1992). Kant’s Philosophy of Arithmetic. In Carl J. Posy (ed.), Kant’s Philosophy of Mathematics: Modern Essays. Dordrecht: Springer, 43 – 79. (Original work published 1969)10.1007/978-94-015-8046-5_3Suche in Google Scholar

Rechter, Ofra (2006). The View from 1763: Kant on the Arithmetical Method Before Intuition. In Emily Carson and Renate Huber (eds.), Intuition and the Axiomatic Method. Dordrecht: Springer, 21 – 46.10.1007/1-4020-4040-7_2Suche in Google Scholar

Resnik, Michael D. (1980). Frege and the Philosophy of Mathematics. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Shabel, Lisa (1998). Kant on the “symbolic construction” of mathematical concepts. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part A, 29(4), 589 – 621.10.1016/S0039-3681(98)00023-5Suche in Google Scholar

Stenlund, Sören (2015). On the Origin of Symbolic Mathematics and Its Significance for Wittgenstein’s Thought. Nordic Wittgenstein Review, 4(1), 7 – 92.10.15845/nwr.v4i1.3302Suche in Google Scholar

Tappenden, Jamie (2019). Infinitesimals, Magnitudes, and Definition in Frege. In Philip A. Ebert and Marcus Rossberg (eds.), Essays on Frege’s Basic Laws of Arithmetic. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 235 – 263.10.1093/oso/9780198712084.003.0010Suche in Google Scholar

Thomae, Johannes (1898). Elementare Theorie der analytischen Functionen einer complexen Veränderlichen (2. ed.). Halle: Nebert.Suche in Google Scholar

Thomae, Johannes (1908). Bemerkung zum Aufsatze des Herrn Frege. Jahresbericht der Deutschen Mathematiker-Vereinigung, 17, 56.Suche in Google Scholar

Wolff, Christian (1710). Anfangs-Gründe aller Mathematischen Wissenschaften, Vol. 4. Halle: Renger.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2024 by the author

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Titlepages

- Titelseiten

- Titelseiten

- Articles

- On Kant’s Schema of Reality

- Kant’s Prize Essay and Nineteenth Century Formalism

- Reflections on Kant on Reflections

- Magnitude, Matter, and Kant’s Principle of Mechanism

- The Impossible Biangle and the Possibility of Geometry

- Topics of the Kant Yearbook 2025, 2026 and 2027

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Titlepages

- Titelseiten

- Titelseiten

- Articles

- On Kant’s Schema of Reality

- Kant’s Prize Essay and Nineteenth Century Formalism

- Reflections on Kant on Reflections

- Magnitude, Matter, and Kant’s Principle of Mechanism

- The Impossible Biangle and the Possibility of Geometry

- Topics of the Kant Yearbook 2025, 2026 and 2027