Abstract

This paper critically examines the importation of concepts and tools from the field of music theory into interdisciplinary research that investigates music and meaning. Within the field of music theory, one type of music theory – Western classical music theory – holds institutional dominance to the extent that the term “music theory” has become synonymous with this specific type of theory, even though it has been demonstrated to be highly incompatible with non-Western musical practices as well as many genres of popular music. This paper examines the biases and blind spots of Western classical music theory that carry over into research in music semiotics and related interdisciplinary fields such as music psychology, critically reflecting on the limitations these biases and blind spots impose on investigations into music and meaning. An eclectic range of alternative discourses on musical knowledge (e.g. from theoretical texts on non-Western and non-classical musical practices) are also explored and insights from these alternative music theories are collated in order to synthesise practical considerations that allow for broader (and less ethnocentric) perspectives to be applied in future research on music and meaning, with a particular emphasis on considerations for multimodal semiotic studies of music in contemporary global media practices.

1 Introduction

The study of music and meaning is inherently interdisciplinary, demanding engagement with multiple fields. Alongside concepts and methods for theorising and analysing meaning making (e.g. from semiotics), it is also necessary to apply concepts, analytical tools and terminology that enable music to be studied, which are often derived from (whether implicitly or explicitly) the disciplinary field of music theory. This is a field that has been strongly criticised (both from within the field and externally) for its white racial, Eurocentric and class centric biases (Ewell 2020; Robinson 2020; Tagg 2014). Interdisciplinary research that applies approaches from semiotics (amongst other fields) to the study of music has undoubtedly contributed to challenging conventional approaches to music scholarship and introduced broader and more critical perspectives to it. However, when the tools of conventional music theory are applied in research on music and meaning with the assumption that they can be used as a neutral apparatus for understanding musical phenomena, not only is there a risk for the same biases to be replicated – resulting in culturally specific practices being equated with universal principles of musical meaning making – additionally, the vast range of ways of understanding musical structure, as well as the broad potential for types of meanings that can be made musically get overlooked. This poses a challenge for research in music and meaning, one that is long overdue to be fully addressed. However, it is also an opportunity for interdisciplinary studies in music and meaning to contribute to the democratisation and decolonisation of music theory.

This paper critically examines the importation of music theoretical concepts and tools into interdisciplinary research that investigates music and meaning making. It does so by identifying the biases and blind spots of the tools and concepts that are commonly borrowed from Western classical music derived theory. It also explores alternative perspectives from music theories derived from non-Western classical musical genres and traditions. In doing so, it critically reflects on the limitations that concepts and tools exclusively derived from Western classical music theory impose on the investigation of musical meaning, and explores the insights that are opened up when alternative perspectives and approaches are considered. These insights are synthesised as practical considerations that can be applied broadly in future research on music and meaning making in general, and more specifically in relation to contemporary multimodal semiotic practices.

2 Background

2.1 The politics of “music theory”

The term “music theory”, used grammatically in the singular and without a determiner or qualifier (e.g. as opposed to “a music theory” or “music theories”) as it is often used, implies theory that can account for all musics, across genres and situated in any social and historical context. For this to be true, music theory must be pluralistic, comprising many different theories, perspectives and approaches based on studies of a wide range of musical practices from different cultural traditions and contexts. Ewell (2023: 23) makes plurality explicit in his idealised definition of music theory, which is “the interpretation, investigation, analysis, pedagogy, and performance of any music from our planet”. In Blum’s (2023) account of music theory in ethnomusicology, his definition of theory is centred around the process of theorising, which comprises processes such as “reflection, introspection, speculation, conceptualization, imagination, judgment, or argument” (Blum 2023: 5), hence “theories […] are at once outcomes of theorizing and invitations or occasions for further theorizing” (Blum 2023: 1). Blum’s (2023: 18) process-oriented definition of music theory emphasises plurality of perspectives through its dialogic nature: “Music theory and musical knowledge […] are subject to continual reinterpretation and transformation”. This definition of music theory points towards the necessity of constant critical engagement.

Critical engagement with music theory involves evaluation of whether a given music theoretical concept, tool or perspective fits with a musical practice, especially when the theory itself was developed in and imported from another context. For example, Farraj and Shumays’ (2019) theorisation of Arabic music in the 20th century seeks in part to “correct misconceptions” sourced from ancient Greek music theory that were introduced by “medieval Arab theorists and then passed down over the last millennium”, as well as misconceptions sourced from European music theory that were first “forced upon modern Arabs in the colonial period and then adopted” in “attempts to modernize and assimilate to Western culture” (Farraj and Shumays 2019: xxx). Critical engagement also entails evaluation of the theory in relation to specific social purposes e.g. whether a theory is intended to be used primarily for normative (e.g. pedagogical) purposes or descriptive ones (Huebscher 2022: 171). An additional aspect of critical engagement is examining how well theorisations of music lend themselves to connections with other fields of human knowledge by recognising music as a complex social phenomenon that is always connected to other dimensions of social reality (cf. Born 2010).

These aspects of critical engagement also reveal the ways in which music theory can be subject to politics in specific institutional contexts (which in turn makes critical engagement all the more important). This is a politics of representation and legitimacy – this is both a question of how music theory represents “music” and thereby define the parameters along which musical practices are legitimated, as well as a question of how music theory represents itself and thereby determines what counts as music theory (or rather, whose music theory counts and who gets to do the theorising?). Within the academic field of music theory, these politics have historically played out resulting in one type of music theory – based largely on a classical canon of music from Europe between the 17th and 19th centuries – maintaining a dominant position and being the central focus of the field. This is a music theory that also places a large amount of emphasis on the internal structure of music, with a focus of one aspect of that structure (namely tonality) and privileges the approach of one theorist (Heinrich Schencker) at the expense of others.

This dominance of Western classical music theory plays out across multiple institutions including music education and academia. In a paper titled Music Theory and the White Racial Frame, Ewell (2020) highlights the white racial dominance of the field of music theory in terms of the composers and theorists privileged in music scholarship and tertiary music education. In this paper, he names and challenges the core belief within the field of music theory that is used to legitimise this dominance, namely the belief that the music and ideas of white composers and theorists (in particular, those from Germanophone countries between the 18th and early 20th centuries) are exclusively or exceptionally worth studying as a basis for music theory, and as well as the belief that issues of race and whiteness are irrelevant to music theory. Johnson-Williams (2023) further unpacks these core beliefs, tracing their history to 19th century European Romantic ideas of there being an inherent autonomous aesthetic value in “the music itself” and hence being beyond any issues of race. She not only documents how such beliefs persist today, but also how they have been continuously used since the Victorian era to legitimise the institutionalisation of a “musical standard” based on the Western canon in music education in the UK and commonwealth countries (Johnson-Williams 2023). Boyd (2025) also argues that the authority and reputation of so-called “music theory” is used to devalue and delegitimate Black music in public and private spheres since it does not meet the specific standards of complexity deemed valuable by a tradition of music theory that is based on repertoire from the Western European classical canon.

Within academic music theory, although there has historically been a narrow focus on theories based on a limited repertoire and a select few theorists, diverse and critical perspectives on music theory can be found. Ethnomusicology has contributed to music theory with alternative perspectives and approaches based on studies that demonstrate Western classical music theory’s incompatibility with many non-Western musical traditions and (perhaps more importantly) demonstrate that often practitioners of these traditions have their own legitimate ways of theorising music that should be taken seriously (e.g. Blum 2023; Feld 1981). Musicological studies of popular music genres (e.g. Butler 2006; Tagg 2013) have done the same. There have also been scholars both within and outside of the field of music theory who have introduced to music scholarship tools from other fields such as semiotics, psychology, gender theory and cultural studies to expand music theory’s focus beyond the internal structure of music. For example, there have been music theorists who have taken in the critiques and observations from ethnomusicology and used tools from psychology to develop less Eurocentric music theoretical frameworks (e.g. Hasty 1997; Rahn 1996). Critical perspectives – whether they concern selecting or adapting music theoretical resources in ways that are sensitive to specific socio-cultural contexts of musical practices, or examining race and racial justice as well as other dimensions of social reality and ethics in relation to music theory – have become more commonplace in academic music theory, especially in recent years amongst scholars who are seeking to expand and redefine the agenda for music theory (e.g. Boyd 2022; Ewell 2023; McCreless 1997; Rehding and Rings 2019).

Although there is an ongoing transformation within academic music theory challenging the dominant position that Western classical music theory holds, the consequences of Western classical music theory’s dominance on musical knowledge more broadly outside of the academic field of music theory should also be considered. The institutionalisation of Western classical music theory as a “standard” in music education in the USA, as well as in UK and commonwealth countries, has far reaching implications for global knowledge production when considering the influential power of the anglosphere on global knowledge production. These include implications for interdisciplinary research that draws upon music theory as a source of knowledge on music. A major area of interdisciplinary music scholarship that should be considered in this context is the study of music and meaning.

2.2 Music theory and interdisciplinary research on music and meaning

There is a broad range of research that examines meaning in music as a psychological and/or social phenomenon. This includes research conducted under various labels such as music semiotics, music psychology (or closely related labels such as music perception and music cognition) and New Musicology. All of these studies attempt to examine the meanings that music has for people producing or listening to it. In other words, they all deal with meaning in musical sound and connect it in some way to extra-musical phenomena, whether it be human perception, emotion or social communication. Key authors who have worked under the label of music semiotics (or music semiology) include Jean-Jacques Nattiez, Eero Tarasti, Raymond Monelle, David Lidov and Robert Hatten, amongst others. Although there is no single approach that unifies music semiotics, the tendency of music semiotic studies is to systematically theorise or analyse music as a meaning making system (for instance, as a ‘grammar’), building up a technical metalanguage of concepts and categories relating to meaning making structures, processes or principles, often drawing on general concepts from semiotic theories (e.g. Peircean semiotics). Studies in the psychological perception of music aim to investigate how (objective) musical sound stimuli are (subjectively) perceived, thus they seek out explanations of how music becomes meaningful to humans (especially in relation to emotion) through general principles of human perception. Studies that were a part of a movement of critical research in music scholarship that came to be known as “New Musicology” sought to analyse how musical compositions (as well as musicological discourses) construct meanings in relation to specific social categories such as gender and sexuality (e.g. McClary 2002).

As is the case with the academic field of music theory, interdisciplinary studies of music and meaning have mainly focused on Western classical music in terms of the repertoire studied. However, all of these different approaches to the study of music and meaning have contributed to expanding the possibilities of music scholarship by introducing new ways of studying music that connect music’s internal structure to extra-musical phenomena. New Musicology’s analysis of meanings in musical works takes musical analysis beyond autonomous aesthetics and makes issues such as “violence, misogyny, and racism” relevant to the study of musical structures and aesthetics (McClary 2002: 4). Music semiotics and music psychology have demonstrated that there are general principles to musical meaning that apply across cultural contexts (e.g. that musical meaning largely derives from the experience of the moving human body), warranting and facilitating further investigation in relation to musical practices outside of the Western canon. For instance, music semiotics opened new pathways for the investigation of how general semiotic principles manifest in ways that are specific to cultural musical traditions (e.g. Martinez 1997).

Tagg (2013) and van Leeuwen (1999) have expanded the study of the semiotics of music by conceptualising general principles of (social) meaning making in music and examining examples from a very broad range of musical genres, traditions, contexts and practices (including multimodal practices such as film and advertising). In doing so, they demonstrate the rich potential and varied forms of musical meaning making beyond that which an exclusive focus on Western classical music has to offer. Their frameworks for music semiotic analysis have also been widely applied to studies in multimodality and musical discourse analysis. Such approaches, however, are an exception in music semiotics, and the majority of work in music semiotics remains largely focused on repertoire from the Western canon.

Although studies in music and meaning have opened up new possibilities for music research, there has been relatively little critical examination of tools and concepts from conventional music theory derived from the study of music of the Western canon. Even studies in New Musicology that attempt to analyse music of the Western canon with a critical lens have often done so relying on conventional music theory derived tools. Tagg (2014) has noted that through his research on non-Western classical genres of music, he was made aware of the problems of applying concepts and terminology from conventional music theory to non-Euroclassical forms of music as they can be “inadequate” and “deceptive” (Tagg 2014: 1). He also notes that although his own work has contributed to identifying specific problems that arise when assuming that concepts from conventional Euroclassical music theory can be applied to any type of music as well as suggesting alternative terms and concepts in these cases, such assumptions still persist in many contexts of music studies (Tagg 2014: 35). Tagg’s campaign to develop alternative ways for denotating and conceptualising musical structure that are less ethnocentric and more democratic than conventional Euroclassical music theory (Tagg 2014) and his call for music semiotics to shift its focus away from repertoire of the Western canon (Tagg 2013: 148–150) go hand in hand.

Just as critical engagement with music theory is important when working within the field of music theory, it is also important when drawing on it while working in any area of music scholarship. For research in music and meaning, critical engagement with music theory should also be accompanied by a principled approach to selecting musical repertoire and contexts for study. The following section will consider a broad area of musical inquiry that is of particular relevance for research on music and meaning today, namely music circulating in the contemporary globalised media ecology.

2.3 Research on music and meaning: multimodal discourse analysis in the contemporary global media landscape

As the previous section highlighted, research in the study of music and meaning has focused on studying the musical repertoire of the Western canon, as has the field of music theory. Tagg (2013: 145–151) has argued that there is an urgent need for musicology and semiotics to take seriously the study of the music circulating in contemporary media as it is this music that is encountered in everyday life, and as noted above, the tools from conventional music theory based on the study Western classical music alone are inadequate for understanding meaning making in such contexts. This relationship between music, media and everyday life has been theorised by Pontara and Volgsten (2017) who argue that the ubiquitous dissemination of music in society, which has both a discursive dimension (i.e. relating to the socially constructed knowledge of what music is) and a sounding dimension, is intricately connected to the process of “mediatisation”, which refers to “the transformation of everyday life, culture and society in the context of the transformation of the media” (Krotz 2017: 110). It has been argued in this context that if a critical literacy of media texts is deemed an important competency in contemporary society, then this media literacy should also include an understanding of musical meaning making (cf. Pontara and Volgsten 2017: 254; Tagg 2013: 115).

Studies in multimodal social semiotics have taken an interest in understanding media texts as a major aspect of the contemporary semiotic landscape. Within this body of research, there have been studies that focus on the role that music contributes as a semiotic resource to multimodal meaning making practices such as television, film, popular music and advertising (e.g. Machin 2010; Moschini and Wingstedt 2020; van Leeuwen 2017; Wingstedt et al. 2010). Such semiotic studies of contemporary media practices that focus on music’s role in multimodal meaning making are relatively rare compared to studies that focus on investigating other semiotic modes (e.g. language, visual images) in these media practices. The relative lack of attention on music’s role in meaning making in global media practices can be attributed, in part, to the difficulty of analysing musical meaning in these practices, especially since most of the existing tools and methods for understanding musical meaning making are not wholly compatible when applied to these contexts.

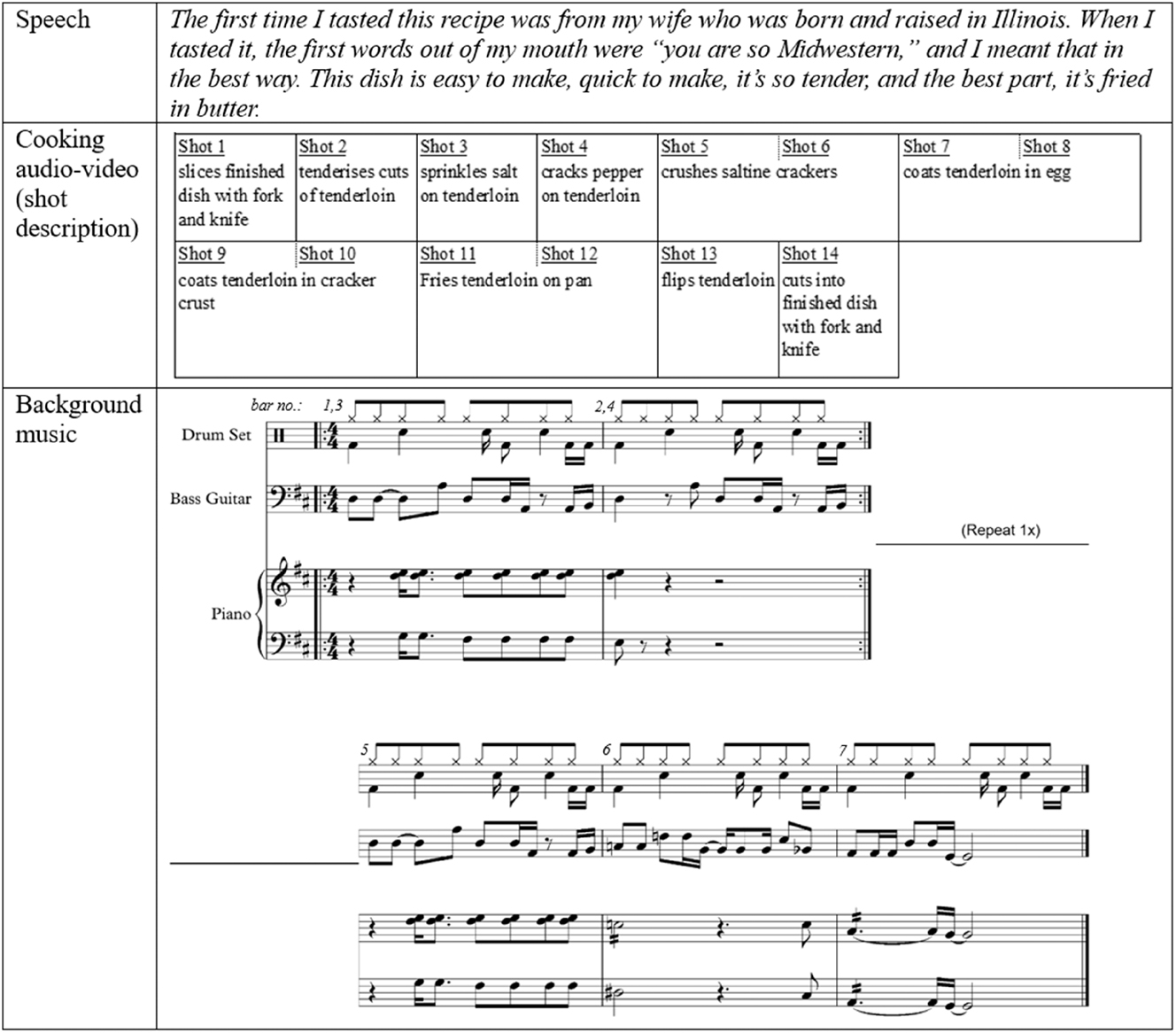

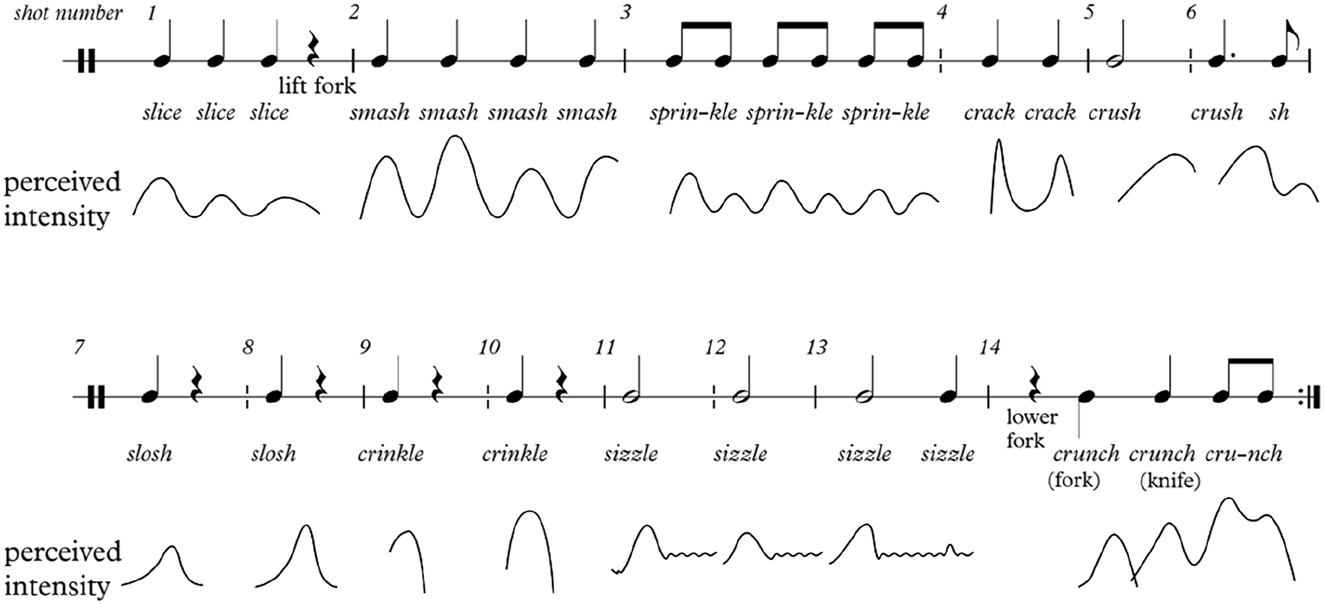

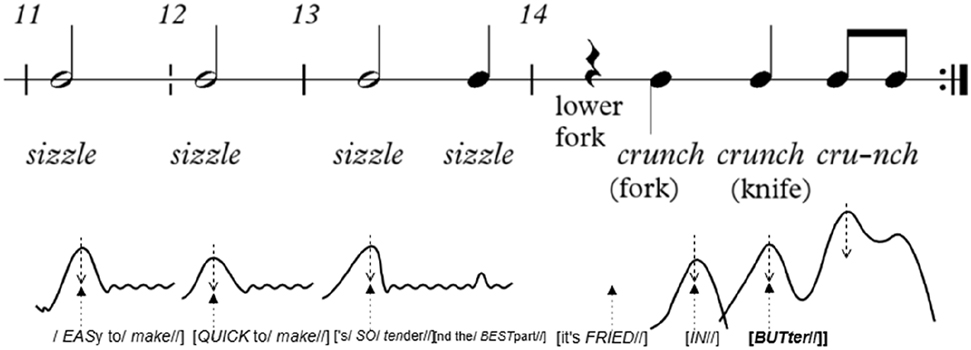

Let us briefly consider an example of a contemporary media text and the questions that arise when attempting to analyse musical meaning making in the example. The example is an Instagram reel (i.e. a short-form social media video) posted by the New York Times Cooking to their Instagram account in December 2024. The reel is a 16-second-long video for a recipe for Saltine-Crusted Pork Tenderloin by the New York Times Cooking writer, Kevin Pang.[1] The reel is audiovisual and combines multiple semiotic resources which I have dissected into three simultaneous semiotic channels and transcribed in Table 1. The first semiotic channel is the speech audio – this is the audio of the recipe writer speaking about the recipe. The second semiotic channel is the audio and video that portray cooking actions involved to make the recipe. This semiotic channel is multimedial since it is audiovisual, however it can be considered as a single semiotic channel since the recorded sounds and recorded visuals of the cooking actions are synchronised to form a single layer of meaning making for the video. The third semiotic channel is the background music.

Transcription of NYT cooking recipe video for Saltine-Crusted Pork Tenderloin.

In this example, “music” is most obviously found in the third semiotic channel labelled as “background music”. However, the background music is not a discrete layer that simply adds prepackaged meanings to the video. All three semiotic channels unfold over time together and create specific temporal relations with one another. Therefore, to fully appreciate the musical meaning of this media text, it is insufficient to analyse the background music in isolation, but rather the musicality of each individual semiotic channel (including the speech audio channel and the audiovisual channel of the cooking actions) as well as the media text as a whole must be taken into consideration. It is also important to consider that the background music was not specifically composed for this multimodal media text. Not only has this specific music audio been used in a myriad of other social media videos, but the generic features of the background music are recognisable enough to trace it to a popular genre of music that appears in many other musical contexts. The conventions of the background music’s genre, the conventions of the type of media text (short form video) and the technological affordances of the social media platform that allow for an excerpt of pre-existing music audio to be easily inserted as background music to any video must all be taken into account together to appreciate how the music as an integral part of the media text makes meaning.

Most existing approaches to understanding or analysing musical meaning are insufficient for addressing the key considerations identified above. Whether these approaches attempt to posit general explanations of how music becomes meaningful to humans, provide detailed and systematic tools for analysis of musical meaning, or demonstrate critical analyses of socio-cultural meanings made in music, insofar as they import tools and concepts from Western classical music theory with the assumption that these tools and concepts are compatible with any cultural musical practice or context, and/or do not substantially engage with alternative music theoretical perspectives, these approaches will be limited.

The remaining sections of this paper will closely examine specific limitations of this literature through a metatheoretical analysis and explore practical considerations for future research in music and meaning, especially for multimodal semiotic research that investigates musical meaning making in contemporary globalised media practices. Section 3 critically examines a selection of discursive blind spots and biases of Western classical music theory that are commonly recontextualised in research on music and meaning, and also explores a variety of alternative music theoretical discourses. The purpose of this section is not to arrive at a “pure” music theory free of blind spots that applies to any music in any context, nor is it to attempt to provide a comprehensive account of the immensely vast range of music theories that have existed across the world throughout history.[2] Rather, it is to explore a limited yet eclectic variety of specific ways that knowledges of music have been constructed that present alternative conceptualisations to conventional theory, and in doing so, demonstrate that Western classical music theory is itself one specific socially constructed knowledge of music that exists amongst many others. Section 4 discusses the findings of the metatheoretical analysis in order to synthesise practical considerations for future research in the study of music and meaning. It does so by identifying some of the underlying principles that emerge from the metatheoretical analysis and connecting these underlying principles to other areas of human knowledge that are relevant to the study of meaning such as social theory, semiotics, and the phenomenology of movement. Section 5 revisits the illustrative example presented above and analyses it from a multimodal social semiotic perspective, applying the practical considerations synthesised in Section 4.

3 The biases and blind spots of Western classical music theory

Theories are always and necessarily incomplete. They foreground certain aspects of a practice and background others (i.e. theories abstract concepts and patterns from practices) in accordance to what is deemed relevant in a particular context or set of contexts. Analysis, like theorisation, is a process of abstraction – it involves separating certain parts of the object of analysis out of the whole. What is important then, is to be aware of what is being abstracted from the whole in the process of analysis, what is being left out, and understanding if and what damage is done in these omissions. To identify the biases and blind spots of Western classical music theory, we can cross-examine other theories and bodies of knowledge related to other musical practices.

The subsequent subsections will take a discursive approach to the analysis of music theories following van Leeuwen’s (2005) approach to discourse analysis. This approach is both Foucauldian and linguistic in that it recognises discourses as: “socially constructed knowledges of some aspect of aspect of reality”; pluralistic in that “there can be different discourses, different ways of making sense of the same aspect of reality, which include and exclude different things, and serve different interests”; and examinable through text analysis (van Leeuwen 2005: 94–95). Thus, the subsections will examine Western classical music theory as one socially constructed knowledge of music and compare this discourse with other socially constructed knowledges of music. The former will be examined through text analysis of research outputs in music semiotics and other interdisciplinary fields that investigate music and meaning (e.g. music perception, music psychology), and the latter through music theoretical texts and other texts that construct knowledge of music that do not come from Western classical music theory. The aim is thus to examine normative discourses of music that have originated in conventional music theory and have been recontextualised in research on music and meaning, and to compare these with instances of theorisation where corresponding aspects of musical knowledge have been socially constructed in different ways in different contexts. To reiterate, the aim is not to provide a comprehensive account of all possible music theoretical discourses that exist, nor is it to arrive at some pure, unmediated musical truth, rather it is to explore a limited yet eclectic plurality of ways that musical knowledge has been constructed in discursive instances of theorisation.

Sections 3.1 and 3.2 examine the boundaries that Western classical music theory has constructed between music and its context, and Section 3.3 examines the constructed “internal” boundaries of music i.e. between the constituents of music, and the specific ways in which these constituents have been conceptualised in Western classical music theory.

3.1 Separation of “music” from its social context

That the word music is used grammatically as a noun is noteworthy, as it allows music to be separated from its social context and for human agency to be backgrounded or erased in analysis. In studies on meaning and music, it is very common to find grammatical constructions that isolate “music” as a discrete entity that contains elements or has characteristics that are meaningful, has its own agency, or has particular effects can that induce responses when people listen to it, e.g.:

[…] in the music(al work): “The framework of the Affektenlehre founded a common understanding of the meaning deposited in the music” (Christensen 1995: 86), “These two metasemes produced in the musical work a kind of divided consciousness” (Monelle 2000: 145).

The music itself: “The listening to the music itself (the level of the musical data)” (Tarasti 1995), “and symbol refers to a response based on internal, ‘syntactic’ relationships within the music itself” (Sloboda and Juslin 2010: 89), “Before proceeding to the music itself, however, I want to reconstruct something of the historical contexts” (McClary 2002: 82).

music with grammatical agency: “Sometimes music can make us laugh, cry, or want to dance” (Larson 2012: 1), “as the music moves away from stability and back towards a new point of stability” (Jackendoff 2009: 201).

music in an ergative-intransitive construction: “[music] feels meaningful and emotional to most people” (Vuust et al. 2022: 287).

As Pontara and Volgsten have highlighted, “there is no such thing as ‘the music itself’; representing music (verbally, visually, etc.) and thinking about music are to be already involved in the cultural construction of what music means and what it is” (Pontara and Volgsten 2017: 251). Musicologist Christopher Small advocates for construing music as an activity rather than as a thing, and therefore uses the term, “musicking” to highlight the specific types of musical activities (e.g. performing, listening, composing) that people are involved in (Small 1998).

In his ethnomusicological study of West African music, Chernoff (1979) underlines the concept of musical cultural integration to stress that African musical forms can only be understood in the context of their social situations:

There are very few important things which happen without music, and the range and diversity of specific kinds of music can astound a Westerner. Ashanti children sing special songs to cure a bedwetter; in the Republic of Benin there are special songs sung when a child cuts its first teeth; among the Hausas of Nigeria, young people pay musicians to compose songs to help them court lovers or insult rivals; men working in a field may consider it essential to appoint some of their number to work by making music instead of putting their hands to the hoe; among the Hutus, men paddling a canoe will sing a different song depending on whether they are going with or against the current. (Chernoff 1979: 34)

Music sociologists have also argued that musical practices should be considered as integral to social practices and to social life itself (Crossley 2020; Hesmondhalgh 2013). When “music” is abstracted from its context as it is in discourses derived from conventional music theory, what is taken for granted are the social roles that participants have in the process of music making and the kinds of activities that they are engaged in. Much experimental research on music perception is thus oriented towards answering questions framed around the mechanisms that explain emotional responses and the desire to move when people listen to music (Vuust et al. 2022). Robinson’s (2020) decolonial work on Indigenous sound studies invites and challenges researches in sound and music studies to adopt a “critical listening position”, which entails becoming aware of the “listening privilege, listening biases and listening ability” that we carry and often take for granted (Robinson 2020: 10). For example, Robinson notes the differences between ontologies of Western music, which “are largely though not exclusively oriented toward aesthetic contemplation and for the affordances it provides” (e.g. setting moods for activities in everyday life), and those of Indigenous song (in relation to Indigenous groups in North America), which serve different functions including “law and primary historical documentation” (Robinson 2020: 41). Taking such ontological differences into account, Robinson illuminates the damage done in the context of ethnographic collection of Indigenous songs in Canada during the 20th century (which was justified as a means of cultural preservation in the face of cultural loss caused by colonial policies that banned Indigenous populations from practicing their own culture) when these songs as “forms of doing (healing, law, and sovereignty)” become disconnected from Indigenous communities (Robinson 2020: 151) and transcriptions and recordings of Indigenous songs are misused by settler Canadian composers in their contemporary art music by breaching Indigenous protocols of their use (Robinson 2020: 150).

In Farraj and Shumays’ (2019) account of Arabic music, music as a dynamic and collective process is highlighted through many different aspects of music making. For example, in describing participant roles in music performances, they explain that.

Performers and listeners (the sammi’a) have a symbiotic relationship in Arabic music. During tarab,[3] a feedback loop develops between them, a very important ingredient for tarab, if not a prerequisite for it. When listeners hear beautiful music that is being performed for them, they react both in verbal and nonverbal ways to show their appreciation. In return, that confirms to musicians that their performance is being appreciated, and that they are provoking the desired reaction in the listeners. That motivates them to give more and to excel and keeps tarab moving forward. (Farraj and Shumays 2019: 367)

Not only is there a dynamic responsivity between audience and performers, but there is also a dynamic responsiveness between performers:

Because of its richness in ornamentation, Arabic music is not required to faithfully follow a composition note for note and can therefore be highly personalized. Heterophony (when different musicians simultaneously ornament the same melody differently) is a dynamic exercise, one that cannot be composed or notated. It happens in a live performance and needs a type of musician who devotes more energy to listening than to reading sheet music. Therefore, experienced Arabic musicians develop a resilient disposition that allows them to be attentive and quick to react to the other musicians’ playing. (Farraj and Shumays 2019: 8)

A final point to make on the separation of music from its social context is that this also includes a separation from its historical and geographical context. Many ethnomusicological studies underline the importance of taking into account social histories and geographical provenance of musical structures to fully understand and appreciate musical meaning, particularly in relation to continuity and variation of musical traditions (e.g. see Brown 2014; Chernoff 1979; Farraj and Shumays 2019).

3.2 Separation of “music” from other semiotic modes

The discursive separation of music from its context also entails a separation of music from other communicative and artistic modes with which it forms a whole. It is not uncommon for papers in music semiotics to base their analyses on musical scores or sound recordings alone. With growing interest in multimodality in semiotic research, there has been an effort more recently to combine the semiotic analysis of music with the analysis of other semiotic modes in multimodal communicative practices such as popular music (Machin 2010) and film (Wingstedt et al. 2010). Whilst such studies have demonstrated that music can be combined and coordinated with other semiotic modes to make meanings in various and complex ways, in many theorisations, music has also been construed as an already integral part of a single practice.

Many traditional genres of Japanese music for instance are integral parts of other artforms such as dance, poetry recitation and theatre. Noh, for example, is a traditional Japanese theatrical art first codified in treatises written by the playwright, Zeami in the 14th and 15th centuries (Komparu 1983: 345–347). A central aesthetic principle in Zeami’s theoretical texts is Jo-ha-kyu, a tripartite spatio-temporal ordering principle, which applies to every aspect of Noh including the compilation of plays in a program, composition of sections in a play, organisation of the performance space, and the rhythm of the performance, which includes performers’ movements, chanting, and instrumental music (Komparu 1983: 24–29). Komparu (1983: 29), also notes that the Jo-ha-kyu principle is found in many other traditional Japanese performing arts.

Zeami’s theoretical text constructs Jo-ha-kyu as a general aesthetic principle, however it can also be constructed as a musical principle when music is abstracted out from the theatrical art. Akira Tamba (1932–2023), a Japanese composer who moved to and had a career in France (where he studied under Olivier Messiaen) had written theoretical texts in French on the aesthetics of Japanese music (e.g. Tamba 1988) distilling music and musical aesthetics out from traditional Japanese performing arts (including Noh) to write to a French audience interested in comparing “Western” and “Eastern” musical aesthetics. He not only wrote theoretical texts on Japanese musical aesthetics (which included the principle of Jo-ha-kyu) but also applied them to his musical compositions, which were otherwise based in a Western classical musical tradition. Later in his career, he had also written a book in Japanese on Jo-ha-kyu as a living and continuous Japanese tradition, writing about it from multiple discursive perspectives including Jo-ha-kyu as a mathematical pattern, as a general aesthetic principle in traditional performing arts, as a musical aesthetic principle in traditional music, and finally as an aesthetic principle that can be applied in contemporary musical composition, in which Tamba analyses how Messiaen applied Jo-ha-kyu in an orchestral composition (Tamba 2004).

Although in Western thinking, music has an obvious association with dance, it is still discursively kept separate from it. Consider the following phrases from a recent review article on neuroscientific research of music: “our ability to dance to music”; “Why do people rush to the dance floor when hearing the grooves on James Brown’s records and move to the music with such apparent pleasure?” (Vuust et al. 2022: 294). The semantics of these phrases makes music (construed as a thing) a pre-existing entity to which people can dance/move (construed as an activity). In this construction, music is independent from dancing, which is an optional addition. Music and dance can, however, be thought of as integrated processes that mutually shape one another. For instance, in his interpretation of L’affillard’s Principes Très-Faciles (1705), an early 18th century French treatise on singing, Schwandt (1974) argues that L’affillard provides detailed instructions for articulation, phrasing and tempo so that singers can learn to perform songs to popular court dances (e.g. courante, menuet, sarabande, bourrée, gavotte, passepied) in a manner that makes them danceable. An even more integrative construction of music and dance can be found in Butler (2006):

EDM dancers at a live event can have a significant impact upon the sounds that unfold. Successful DJs are highly attuned to the crowd’s behavior: most do not play prearranged sets, instead preferring to shape their performance as the evening unfolds in order to get a maximal response from the people on the floor. As a result, the audience’s actions – whether or not they dance, the intensity with which they dance, and the other physical and verbal cues that they give to the DJ – can affect what music will be played, when it will be played, and how it will be played.

Furthermore, communication flows […] not only between audience and DJ, but also within the audience itself. Individual dancers collaborate with the DJ and with each other to create a sense of “vibe” – a powerful affective quality associated with the experience of going dancing – among those present. […] this sense of communal energy is an essential part of an effective event. (Butler 2006: 72)

Just as is the case in the performance of Arabic music, music making here is construed as a dynamic and collective process that cannot be separated from its context, which in the case of EDM (Electronic dance music) live events includes dancers. Hence, vibe can be thought of as a music theoretical concept that recognises dancer and DJ (Disc Jockey) to be integral participants in a social musical activity in the context of EDM practices, just as tarab can also be thought of as a music theoretical concept in the context of Arabic musical practices.

3.3 Division of “music” into separate constituents

That a music theory separates music into separate analytical constituents or aspects is self-evident. However, where a theory draws the lines between aspects of “music”, which ones are focussed on, and generally how they are conceptualised can have many possibilities. Studies on meaning and music often take analytical categories from conventional music theory and use these concepts as a point of departure for investigating musical meaning. For example, Tarnawska-Kaczorowska (1995), analysing the music work as a “sign”, considers the lowest layer (i.e. the fundamental level of structure) as the materials of music, which include “the sound (acoustical signal) itself”, “articulation”, “dynamics”, “rhythm”, “meter”, “agogics”, “melody”, “harmony”, and “texture”. The examples that she gives of each constituent reflects conventional music theoretical understanding e.g. “the sound (acoustical signal) itself: a, C, F#, Eb”, “articulation: legato, sforzato, sul ponticello, frullato;”, “rhythm: quarter-note, dotted eighth-note, triplet, rest”, “melody: a two-bar ascending melody, an intervallic structure based mainly on second”, “harmony: major third, perfect fourth, augmented triad, a quartal chord, subdominant, variously formalized systems for noting the harmonic progressions” (Tarnawska-Kaczorowska 1995: 123).

Although Tarnawska-Kaczorowska (1995) lists nine distinct constituents, it is not uncommon for studies to single out a smaller number as being the most important “fundamental” constituents of music e.g. “from the point of view of music theory, music can be broken down into three fundamental constituents – melody, harmony and rhythm” (Vuust et al. 2022: 287). As Vuust et al.’s review article encapsulates, studies in music perception and cognition tend to use one or more of these analytical concepts as a basis for study e.g. research questions are formulated around how the brain processes these elements of music, what mechanisms and parts of the brain are involved, and also seek to understand the psycho-physiological responses in terms of emotion or action, the effect of prior musical learning, and consequences for musical communication in relation to “cognitive processing” of these musical constituents. It is also not uncommon for these specific music theoretical concepts to be foregrounded in music semiotic analyses and used as the basis for analysing musical meaning, e.g. Larson’s (2012) framework for analysing musical meaning based on metaphors of motion recognises two categories of musical forces: melodic forces and rhythmic forces.

The remaining subsections will examine how melody, harmony and rhythm are conceptualised in conventional music theoretical discourses and compare these conceptualisations to alternative ones found in other music theoretical discourses. The purpose of these subsections is to illustrate not only the incompatibility of these Western frameworks when applied to non-Western (and non-classical) musical practices, but also to illuminate the ways in which these conceptualisations on their own provide a limited view on music as a type of meaning making phenomenon, and to explore a range of alternate perspectives.

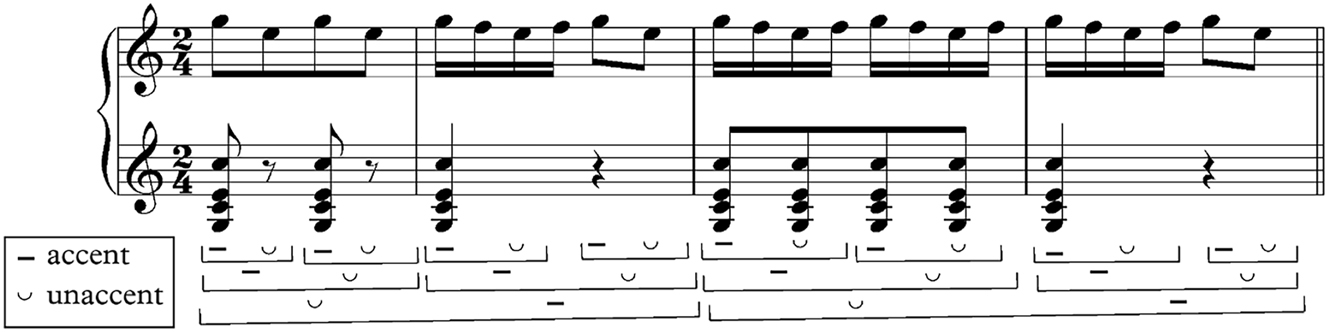

3.3.1 Melody

In Western music theory, the basic unit of melody is the pitched sound (or “note”), which is systematised into 12 pitch classes which divide the tonal space of the octave evenly into intervals of semitones (Figure 1) and can also be organised into a circle of fifths. Melodies are understood as a sequence of discrete pitched sounds, which form melodic contours. The collection of pitches in the melody points to a tonal centre (the tonic) and a scale of notes that can ascend and descend in steps (relatively small intervals) from the tonic in one octave to the tonic in the next octave up or down. The specific scale (order of intervals from tonic to tonic) suggests a particular modality, which in Western music is either the major or minor mode (see Figure 2).

Octave divided into 12 notes, each separated by an interval of a semitone.

C major scale.

In this discourse of melody, discrete pitched sounds are the basic building blocks and analytical point of departure: “Once musical pitches are combined into melodies, global properties emerge, such as melodic contour, melodic expectations and tonality” (Vuust et al. 2022: 291). For Larson (2012), although melody “is not just a succession of pitches but may be heard in terms of physical motion”, his entry point and basis for melodic analysis is the sequential organisation of discrete pitched sounds, for example:

In “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star,” the first note (C) provides a base for subsequent melodic action. Every other note is heard as above that C. And if we pause on any of those other notes, we may feel that the unfinished melody is “up in the air.” In other words, melodic gravity pulls all those other notes down. […] This melody has a prototypical shape. A large ascending leap is balanced by descending steps, creating an arching path. […] As in an analogous physical motion, the energy of the large ascending leap is dissipated in the following descending steps. To me, this leap suggests a quality of ease because it leaps from the most stable platform (the tonic) to the next-most-stable degree of the scale (the fifth scale degree). That ease, combined with the energy associated with an ascending leap of this size, suggests a kind of athletic quality that is effortless and secure. (Larson 2012: 83–84)

The above example is typical of music semiotic analysis based on melodic analysis – sequences of notes are analysed, and meaning is interpreted in relation to the size and direction of intervals between notes, the relationship between notes and the tonal centre (e.g. stable/unstable) and the overall melodic shape.

Within this discourse of melody, it is often assumed that what is specific to Western music are tonal conventions and vocabulary. In other words, it is assumed that melodies can be constructed or analysed in any musical tradition as sequences of discrete pitches selected from culturally specific closed systems of pitches (equivalent to the Western 12-tone system in Figure 1) and reflecting melodic scales/modes that are distinct from,but constructed using the same principles as melodic scales in Western music. However, when closely examining other musical practices and knowledges based on those practices, it becomes apparent that this framework is not always an ideal way of understanding melody, and in some cases, is incompatible.

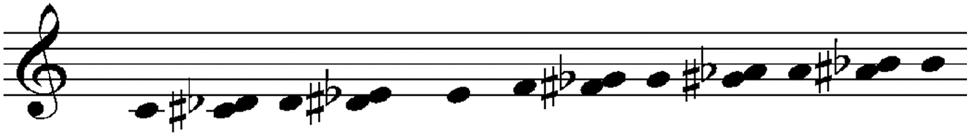

For instance, Farraj and Shumays (2019) have argued that the Western framework for melody is incompatible on multiple levels when applied to Arabic musical practice. Firstly, the basic unit that they assign to melody in Arabic music is the jins (plural: ajnas) and not a discrete pitched sound (Farraj and Shumays 2019: 192). A jins is defined as an area of melody with phrases in a limited vocal register (usually around 3–5 notes) and a distinct and identifying interval structure between notes (Farraj and Shumays 2019: 192–193. See Figure 3a below). A melodic pathway will remain in a jins before moving (modulating) to a different jins either up to a higher register or down to a lower register (Farraj and Shumays 2019: 192). Each jins has a distinct set of intervals and therefore a distinct character or mood, so each modulation to a new jins along the melodic pathway brings with it a change of character/mood (Farraj and Shumays 2019: 195). The two most important notes in a jins is the tonic (the “note of principal melodic emphasis”), the leading tone (the note immediately below the jins) and the ghammaz (the note of modulation – when modulating, the tonic of the upper jins will be the same as the ghammaz of the lower jins) which is also emphasised, particularly when modulating (Farraj and Shumays 2019: 195–196). Each jins has multiple possibilities for modulation to other specific ajnas, and a network of interconnecting ajnas which maps out the possibilities for modulation between ajnas is called a maqam (plural: maqamat), which also reflects the full collection of musical pitches across the network of interconnected ajnas (see Figure 3b). The complete melodic pathway that is formed as the melody modulates from jins to jins (within the network of a maqam) is the sayr (literally “course” or “motion”), which also carry with it expectations and conventions for melodic behaviour within a maqam (Farraj and Shumays 2019: 314–315).

Diagrammatic representations of a jins and a maqam: (a) diagrammatic representation of a jins, loosely based on figure 13.4 in Farraj and Shumays (2019: 199); (b) diagrammatic representation of a maqam as a network of ajna, based on diagram in Farraj and Shumays (2019: 280). Each ellipse represents a particular jins and lines indicate possible movement between ajna.

This very concise (and perhaps oversimplified) overview of Farraj and Shumays’ (2019) theoretical conceptualisation of melodic pathways in Arabic music illustrates many points of incongruency with a conventional Western conception of melody. Firstly, the basic unit of melody is not a pitched sound but the jins. It may be tempting to ask why the “note” is not considered the basic melodic unit, since a jins can be further broken down into distinct pitched sounds. Farraj and Shumays stress that pitches (and the intervals between them) are not considered in the abstract, but rather, they are only considered specifically in relation to “its effect on the jins as a unit” (Farraj and Shumays 2019: 194). This is not to say that intonation is approximate in Arabic music – on the contrary, intonation in Arabic music is in fact more precise and strict in comparison to Western music (Farraj and Shumays 2019: 10). Farraj and Shumays argue that it makes little sense to theorise a complete set of possible pitches in Arabic music (analogous to the equal temperament 12-pitch system used in Western music) from which melodies and melodic scales are built, since if one were to do so, there would be an incredibly fine level of detail e.g. “if we take […] the [equal temperament] semitone between the notes E-flat and E-natural, at least 10–12 aurally distinct pitches from different maqam scales occur within it” (Farraj and Shumays 2019: 167). Further, there is no direct equivalent concept of a melodic mode or scale – both the jins and the maqam are concepts with similar aspects, but neither of them translate perfectly and both have very clear differences.

What is clear when we compare the conceptual affordances between the conventional Western understanding of melody with that of Farraj and Shumays (2019) is that the latter emphasises the melodic pathway as a continuous whole rather than something that is built up from a sequential ordering of discrete units (i.e. a “syntax”). The jins, as the basic unit of melody is larger than a discrete pitched sound, and even above this basic unit, connection between ajnas is emphasised through concepts such as a modulating note and the metaphor of a maqam as a network of interconnected ajnas which maps out potential melodic pathways.

Alternative discourses of melody can also be found in traditional Korean genres of music, which have produced a very diverse range of systems of recording and transmitting musical knowledge. One type of system used to facilitate the reproduction of music is Gueum, which uses a closed system of onomatopoeic syllables that imitate an instrument’s timbre to indicate playing style and pitch (Kwon 2024). Gueum has been used both in oral transmission as well as a system for written notation of music, used in yukbo type scores which were widely used by the late 15th century (Kwon 2024). Although many different Gueum systems existed across different time periods and for different instruments, a common feature was that the consonants of a syllable would indicate timbre and playing technique (e.g. plucking with a plectrum) and the vowels would provide an indication of relative pitch (Kwon 2024). When notated in yukbo, gueum notates musical sound in discrete segments and thus does not indicate the individual musical expression of the performer (Kwon 2024). Gueum, like the conventional Western system of notation, organises musical sounds into a discrete system. However, whilst in the Western system of notation, discrete “notes” indicate the pitch, in gueum, pitch is not as important as the timbre that is indicated by each note. When extended to the concept of melody, this makes it possible to conceptualise melody as a pathway not only of changing pitches, but also of changing timbre.

Another type of score notation that is found specifically in traditional vocal genres of Korean music (such as gagok and sijo) that first appeared in the 18th century is supa-bo, which (in contrast with notation forms that used closed systems of notes notated as discrete segments) represents melodies as continuous wavy lines (Jo 2021; Y. W. Kim 2010). Although reproduction of musical pieces is difficult using these types of scores alone, the representation of the melodic flow and the overall melodic line has allowed it to be an effective learning aid not only in learning gagok songs (Y. W. Kim 2010), but also in contexts of contemporary school music education (Jo 2021).

In traditional genres of Korean music, a concept that is roughly equivalent to that of melodic mode or scale is akjo. However, akjo is much broader than the Western concept of melodic scale encompassing more than just intonation of melodic materials. For example, consider the following description of performance of woojo and gyemyeonjo (which are two akjo that are found across various instrumental and vocal genres of music) found in Hakpo Hyeongeumbo, a music theoretical text presumed to date from the early 20th century:

The sound of woojo ascends and descends, momentarily flies then momentarily hides likes dripping water. The sound of gyemyeonjo is extremely strong and clear, like striking metal or stone. The learner must understand this. (in Kang et al. 2021: 630 translated to modern Korean by editors, my translation to English)

This passage in the Hakpo Hyeongeumbo immediately precedes a series of scores notated in supa-bo type notation,[4] each score also indicating whether the song is in woojo or gyemyeonjo.

When we examine sources of knowledge of Arabic and Korean genres of music, we find that melody can be conceptualised in different ways, e.g. not just a shape that is built from a sequence of discrete pitches, but as a dynamically flowing pathway, which is not only a pathway of degrees of pitch but simultaneously of other aspects of sound as well.

3.3.2 Harmony

In Western music theory, harmony is closely related to melody since it uses the same materials (i.e. pitched sounds) and is therefore also an important dimension of tonal organisation. Tonality, with its focus on harmony, and based largely on the theories of Austrian theorist, Heinrich Schenker (1868–1935) plays a central and defining role in Western music theory. The point of departure for the conceptualisation of harmony is the simultaneous combination of the pitched sounds to form chords. In Western tonal harmony, chords are formed by simultaneously stacking pitched sounds (at least three) in intervals of thirds, which therefore forms tertial chords (Tagg 2014). Western tonal theory is concerned with how chords are ordered in a sequence, and the resulting movement of individual lines (including the melody) from this harmonic sequence. Chords are formed based on each degree of the major or minor scale. The two most important chords are the ones built on the first degree (the tonic, or I) and fifth degree (the dominant, or V) of the scale. Schenkerian analysis is primarily concerned with identifying the underlying, “fundamental structure” (German: Ursatz) of a musical work, which can be summed up as goal-oriented motion from I to V and back to I (Schenker 1979: 4). Thus chords are assigned functions in relation to this structure e.g. chords IV (subdominant) and ii (supertonic) in the major mode primarily function as pre-dominant chords, i.e. they lead up to chord V, which subsequently leads back to chord I.

Since this type of “harmonic language” forms a central part of the meaning in Western classical music, semiotic studies of Western classical music often incorporate harmonic analysis and point out whether the harmonic movement towards its goal is direct or if it deviates in some way e.g.:

One of the attractions of Brahms’s Hungarian Dance especially evident in measures 17–32 is the brusque simplicity of his harmonic language. Making do with little more than tonic, dominant, and subdominant he charts a confident and unwavering harmonic course through the tonal landscape of the dance. To be sure, the broad outlines of this landscape are part and parcel of the traditions of Western European dance music; that said, the specific course Brahms traces is a consequence of the syntactic processes he deploys, which organize the constituent sonic analogs of the passage to create an analog for a dynamic process that moves surely and somewhat precipitously toward its goal. (Zbikowski 2017: 118)

This type of analysis which is common in music semiotic analyses can also be found in McClary’s (2002) analysis of an aria from Donizetti’s opera, Lucia di Lammermoor:

In measure 32 there is a sudden pivot from the key of the dominant, Bb major, to the key of its lowered submediant, Gb major. And it is at the moment of this flat-six excursion that the kind of madness Donizetti seems to have in mind bursts forth in all its splendor. (McClary 2002: 93)

Chord progressions are also commonly used in experimental studies on music and emotion that address the general concept of “musical expectancy” by testing listener responses to “unexpected chords” (e.g. Steinbeis et al. 2006) within a Western tonal framework.

It is worth noting that the basic principles of tonal harmony apply not only to Western classical music, but also to the majority of musical practices of global Western culture (e.g. popular music, film music), therefore Western tonality and chord progressions have become a dominant paradigm for understanding music in the context of globalisation. Although conventional Western classical harmonic theory is the dominant framework for understanding harmony, it is not the only one. In the 1950’s and 1960’s, George Russell developed a theory to describe different ways in which jazz musicians in the US were relating melodic scales to chords through their improvisations, which came to be known as the Lydian Chromatic Concept of Tonal Organization (Russell 2001). Russell’s theory recognised different types of tonal gravity including “Horizontal Tonal Gravity” (HTG) and “Vertical Tonal Gravity” (VTG), the latter associated primarily with the “modal” jazz movement. In HTG, which is based around the tonality of the major (i.e. Ionian) scale, chords function to accompany melodic movement that resolves towards a “tonic station” goal (thus chords function in the same way as in Western classical music). In VTG, which is based around the tonality of the Lydian scale, the chord and melodic scale form a unity (Russell uses the concept of “chordmode” to capture the unity of chord and melodic mode), therefore there is no “goal pressure” (Russell 2001: 9) and melodies are related “to each chord in the chordstream as an autonomous vertical entity” (Russell 2001: 58). In HTG (and conventional Western tonality), chords and their functions are derived from the degrees of the melodic scale where as in VTG, melody is derived from each individual chord.

Russell’s (2001) theory of harmony is based on the 12-tone system of Western music, yet it uses these resources in very different ways to “conventional” Western tonality. It is also possible find other forms of tonality and harmony from non-Western musical traditions, however, the diversity of non-Western forms of tonality has been lost and threatened as a result of the “colonising force” of European tonality, a topic Agawu (2016) has critically examined in the context of the African continent. Agawu (2016) describes one such form of tonal expression that has existed on the African continent since the pre-European era, namely use of the anhemitonic pentatonic scale (Agawu 2016: 343–344). He analyses a recorded performance by Bibayak pygmies from Gabon using this tonal resource and highlights how it contrasts with European tonality:

Each singer has internalized the pentatonic horizon and sings her individual part against that horizon, assured that articulating one or two notes – that is, a subset of the five-note collection – is enough to guarantee the integrity of the resultant pentatonic texture. There are no long-term trajectories in this mode of play, no phrase-generated expectations, no authentic cadences, no archetypal urges of managed desire and its fulfillment. There is only presentness, the repetition of notes and groups of notes into patterns organized around a palpable pulse. The form emerges additively from an accumulation of nows, a kind of moment form. […] If modern artistic production were being guided by this pentatonic practice, it would explore the openness of resultant sounds; give priority to intervals of seconds, fourths, and fifths; embrace a nonteleological temporality; and prefer an egalitarian texture to a hierarchic one. This is, of course, not a prescription for what composers should do but a thought experiment about what they would do if they were following certain cultural or communal imperatives. (Agawu 2016: 343–344)

It is also important to remember that whilst in Western classical music, harmony is the principal paradigm for developing complexity as well as for combining parts to form a whole (which is literally what complexity is), in other musical traditions, we find other areas of complexity and part-whole relations. For example, as alluded to in Section 3.3.1, the focus in Arabic music is on melodic complexity and richness, which is facilitated by heterophony that allows multiple musicians to simultaneously ornament the same melody in idiosyncratic ways (Farraj and Shumays 2019: 8). In many African musical traditions, there is a focus on rhythmic complexity (Chernoff 1979: 41), which will be discussed in the next section.

3.3.3 Rhythm

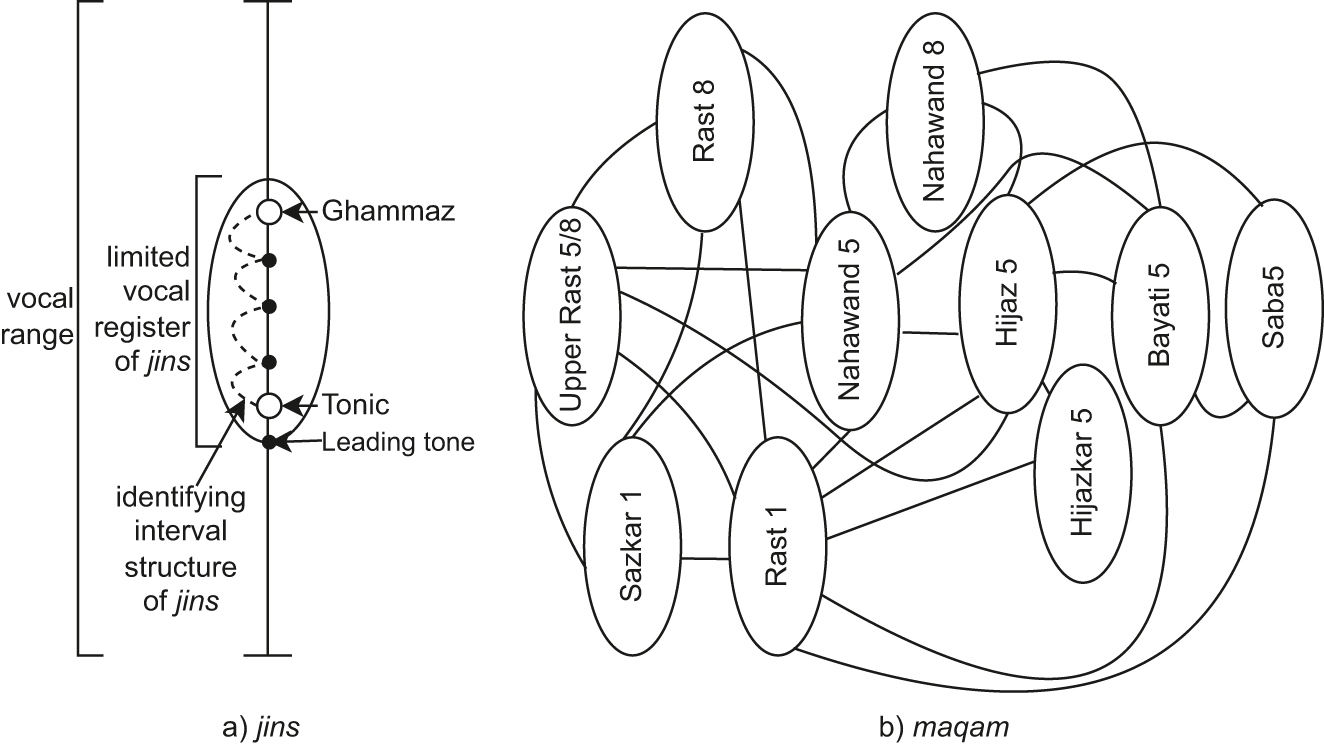

In Western classical music theory, rhythm is often defined as temporal durations of notes and rests, which can be measured by a metre, which is the underlying regular pattern of accentuation of a regular pulse (or “beat”). When the rhythm stresses notes that fall on weak beats or between beats, this is often referred to as syncopation. In Western classical music theory, the study of rhythm has historically had much less focus than harmony, however theories of rhythm that apply to Western music do exist. One of the first key theories was by Cooper and Meyer (1960), who develop a very intricate, unconventional and perhaps controversial framework for analysing rhythm in Western classical music. In their view, rhythm should not be sidelined, as they declare in the very first sentences of their book: “To study rhythm is to study all of music. Rhythm both organizes, and is itself organized by, all the elements which create and shape musical processes” and take a position against reducing rhythm to durational proportions (Cooper and Meyer 1960: 1). In this framework, metre measures the regular alternation between accented beats and unaccented beats (e.g. one accented beat for every three beats), and rhythm is the grouping of unaccented beats with accented beats. Each rhythmic group has one accented beat plus one or more unaccented beats. Rhythmic groups can then be grouped together to form rhythmic groups at a higher level. The rhythmic group at the higher level will be composed of one accented rhythmic group and one or more unaccented rhythmic groups. Rhythmic groupings can then be formed at the next level up with the same principles. These levels are called “architectonic levels” and also apply to metre, with metric accents at each level generally coinciding with rhythmic accents. Figure 4 is an example of a rhythmic analysis by Cooper and Meyer (1960) which illustrates the principles of their framework directly listed above.

Rhythmic analysis of excerpt of Haydn’s String Quartet Op. 33 No. 3 found in Cooper and Meyer (1960: 38).

What is noteworthy about their framework for rhythmic analysis is that although rhythm is independent of metre to some degree, rhythm and metre are also inextricably linked – rhythmic accents coincide with metric accents, and rhythmic groupings can only have one accent, meaning that the duration of a rhythmic group is limited to (approximately) one metric cycle of alternation. Also, both accentuation and rhythmic grouping are perceptual, relational concepts – accentuation means a beat or rhythmic group is “marked for consciousness” (compared to unaccented beats) by various means, and grouping is determined by similarity or proximity, by various means (Cooper and Meyer 1960: 6–7). It is worth noting that Cooper and Meyer (1960) draw on evidence from experimental studies on perception to build their music theoretical framework. Whilst this is just one aspect of rhythm in their framework, there is also much interest in studying musical rhythm primarily through a perceptual psychological lens (e.g. London 2012). Another noteworthy feature about their theoretical framework is the conceptualisation of musical structure as dynamic process:

As a piece of music unfolds, its rhythmic structure is perceived not as a series of discrete independent units strung together in a mechanical, additive way like beads, but as an organic process in which smaller rhythmic motives, while possessing a shape and structure of their own, also function as integral parts of a larger rhythmic organization. (Cooper and Meyer 1960: 2)

Another theory of rhythm that builds on the approach developed by Cooper and Meyer (1960) is found within the Generative Theory of Tonal Music (GTTM) by Lehrdahl and Jackendoff (1983), which is a theory heavily inspired by Chomskyan linguistics and aims to theorise music in relation to a “generative grammar”. GTTM’s framework for rhythmic analysis is similar to Cooper and Meyer’s (1960) framework, however a significant difference is that they return to a more “conventional” distinction between metre and rhythm (which they call grouping) – metre forms an abstract “grid” of time points (which are not durations), and grouping forms durations which can be measured by metre, but is independent from it. From this perspective, temporal durations and temporal measurement are separate phenomena.

It could be argued that the rhythmic model proposed by GTTM, with the measurement of time as an abstract “grid”, is well suited for analysing rhythm in Western classical music since Western classical music has what Chernoff (1979: 42) calls a “unifying” or “main” beat that all musicians adhere to. As noted in 3.3.2, Western classical music builds complexity in its harmonic progressions. Since the building blocks of harmony (chords) require temporal simultaneity, Western classical music tends to be monorhythmic – all instruments play to the same beat.

Chernoff (1979) describes a very different rhythmic sensibility in the musical traditions of West Africa. Rather than there being a unifying beat, different instruments play separate rhythmic patterns with individual accentual patterns that do not meet one another, which from a conventional music theoretical perspective would be described as “polymetric” (Chernoff 1979: 42). Although there is no unifying beat, the separate rhythms are unified: rhythms fit together into a “cross-rhythmic fabric” (Chernoff 1979: 51). In other words, different rhythms fit together by each having a beat that mutually responds to one another (thus have a conversational relationship with one another) rather than one that is simultaneous with one another (Chernoff 1979: 55). An effect of cross-rhythms is that rhythms mutually define one another by cutting each other in different ways (Chernoff 1979: 52, 59). In order for this to be effective, different rhythms must adhere to the conversational relationship, so that the rests and unaccented parts of one rhythm allows other rhythms to be better accentuated:

A rhythm which cuts and defines another rhythm must leave room for the other rhythm to be heard clearly, and the African drummer concerns himself as much with the notes he does not play as with the accents he delivers. […] In traditional African music, compositions have been developed and refined over the years, and superfluous beating has been eliminated so that the rhythms do not encroach on each other. A master drummer’s varied improvisations will isolate or draw attention to parts of the ensemble more than they seek to emphasize their own rhythmic lines, and a musician must always play with a mind to communicative effectiveness. (Chernoff 1979: 60)

What Chernoff (1979) also makes clear is that rhythm goes hand in hand with repetition in African music:

Repetition is an integral part of the music. It is necessary to bring out fully the rhythmic tension that characterizes a particular “beat,” and in this sense, repetition is the key factor which focuses the organization of the rhythms in an ensemble. The repetition of a well-chosen rhythm continually reaffirms the power of the music by locking that rhythm, and the people listening or dancing to it, into a dynamic and open structure. The rhythms in African music may relate by cutting across each other or by calling or responding to each other, but in either case, because of the conflict of African cross-rhythms, the power of the music is not only captured by repetition, it is magnified. (Chernoff 1979: 111–112)

In Western classical music, repetition finds its place in metre (i.e. in a regular “beat”) but not necessarily in rhythm, which is simply the durational values of notes and groups of notes. Anku (2000) theorises that in African music, each recurrent rhythm provides a “regulative beat”. However, rather than keeping linear time as the Western conception of metre does, Anku argues that African music should be understood in relation to circular (or cyclical) time – each cycle of rhythmic repetition is a regulative beat, and multiple rhythms form concentric time circles. Other music theorists have also called into question the applicability of conventional music theory’s strict division of rhythm and metre to African music (e.g. Hasty 1997; Rahn 1996). Rhythmic/cyclical repetition (e.g. in the form of riffs) has also been recognised as playing an important role in musics of the African diaspora more broadly (Floyd 1995; Monson 1999).

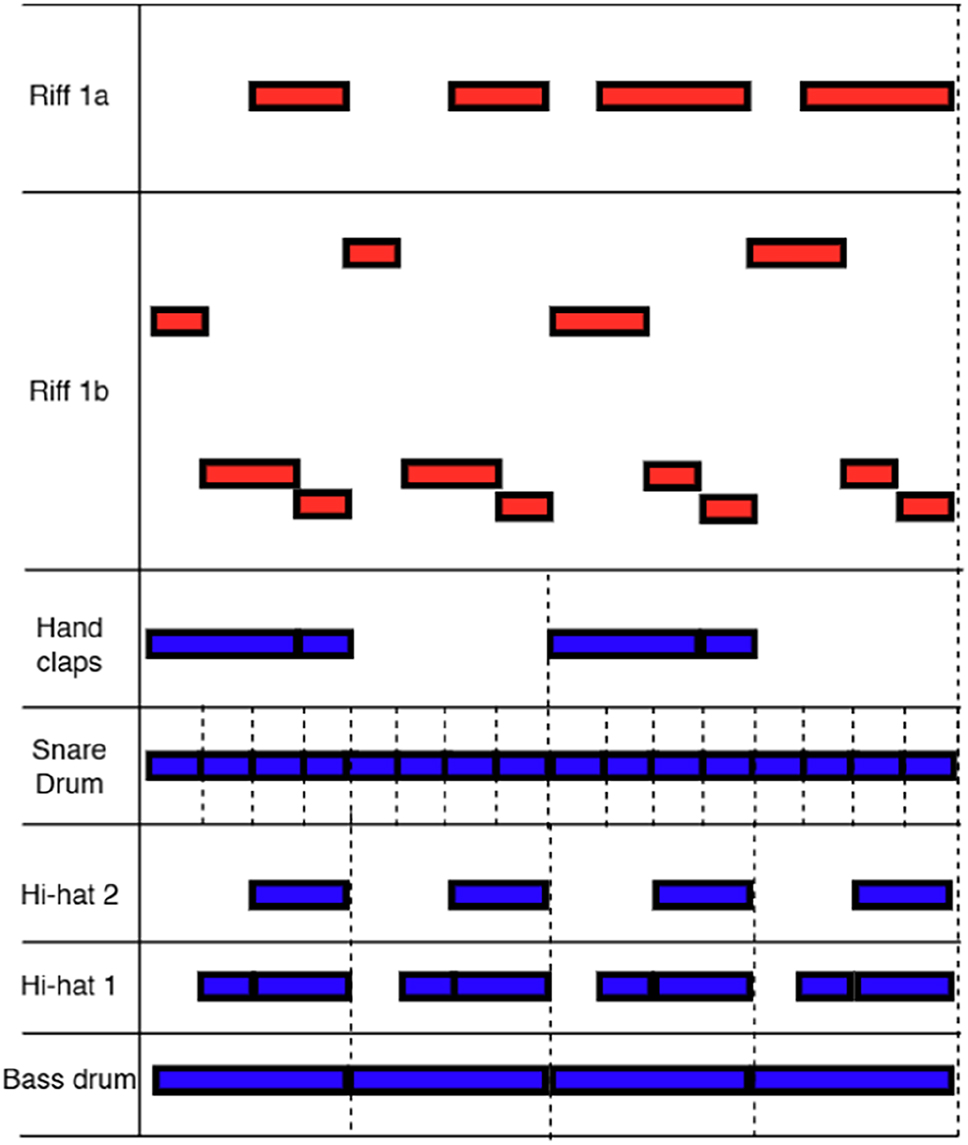

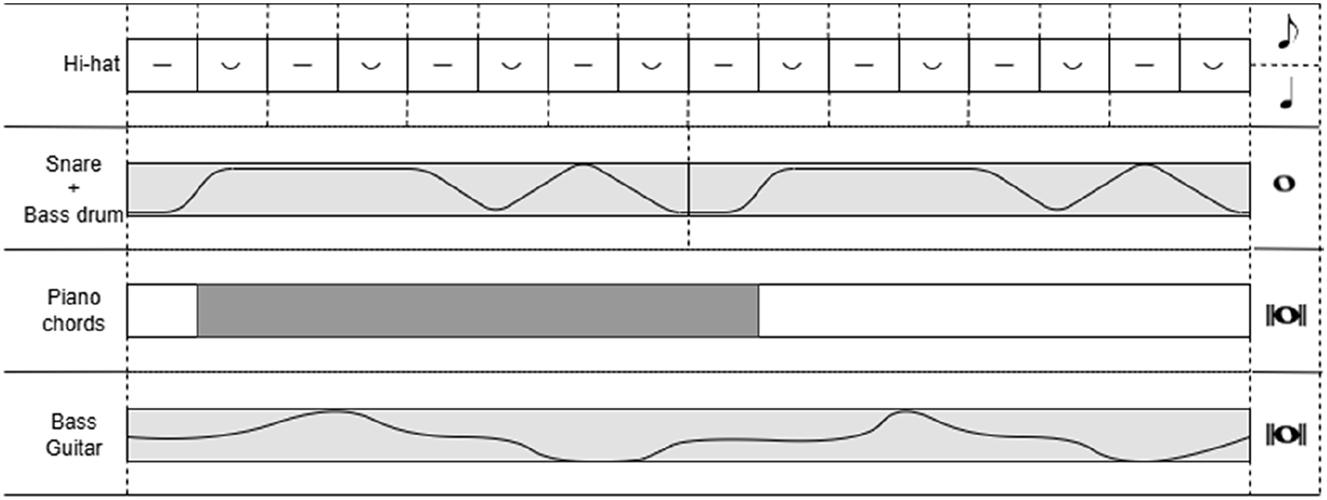

One genre of music with origins in African American musical practice in which the layering of cyclical repetition is particularly prominent (and a defining feature) is techno. In techno (and other EDM genres) repeating patterns are known as “loops” and in some cases, a techno track will exclusively be composed with loops (Butler 2006: 90). Butler (2006: 95–113) analyses a pre-recorded techno track by Jeff Mills titled Jerical (1992) in order to demonstrate how the theoretical distinction between rhythm and metre is not useful in this genre of music and to also illustrate that textural and rhythmic/metric processes are intertwined. Butler dissects the different instrumental layers of Jerical to show two characteristic features of the genre: the music is built on layers with distinctive sounds, which together form a blended but heterogenous texture (no one layer is more prominent more than any other) and each layer plays a loop (see Figure 5).

Graphic notation of the loops played by each instrument in Jerical (1992) by Jeff Mills, based on transcription in Butler (2006: 97). Dotted lines indicate where each cycle begins again.

Although each layer only plays one short pattern repeatedly, layers are introduced progressively, one by one until eventually the track reaches a point where it has a “complete texture”. After this point, different textural configurations are explored as different layers are taken away and reintroduced. What Butler highlights in his analysis is that this process of “textural completion is accompanied by a metrical completion” (Butler 2006: 97). Butler notes that each layer not only has a loop with a unique rhythmic pattern, but also a unique rhythmic value: the rhythmic value of the loop of the riff layers is a semibreve, a minim for the hand claps, a quaver for the snare drum, and a crochet for the bass drum and hi-hat layers. What Butler notes is that each of these rhythmic values corresponds with a distinct level of a 4/4 metre, and when all layers are played together they combine to form this 4/4 metre, but when any layer is missing, the metre is also incomplete and thus the metric identity of the music is heard differently. What Butler’s analysis and argument essentially illustrates is that each rhythmic layer provides a “beat” against which any other rhythmic layer can be measured, thus the distinction between rhythm and metre is unnecessary, in a similar way that Anku (2000) theorises that a recurrent rhythm will provide a regulative beat.

In a paper titled Riffs, Repetition and Theories of Globalization, Ingrid Monson (1999) makes note of the cross-cultural continuities of the underlying the principles by which repetition is used in layered ways across musics of the African diaspora:

Although musics such as jazz, Afro-Cuban, zouk, Haitian vodou drumming, bata drumming, and the traditional musics of the Ewe, Dagomba, and Banda-Linda peoples are extremely divergent in terms of musical surface, the continuities at the level of collective musical process and use of repetition are striking. Repeating parts of varying periodicities are layered together to generate an interlocking texture […] which then serves as a stage over which various kinds of interplay (call and response) and improvisational inspiration take place. If the layered combination generates a good flow (hits a groove) a compelling processual whole emerges that sustains the combination through time and also the people interrelated through playing it, dancing to it, or listening to it (live or on recordings). That these combinations often carry named identities (swing, guaguancó, gahu, etc.) illustrates the symbolic and affective dimensions of the synthesizing cultural flow that emerge simultaneously from these processes. (Monson 1999: 36–44)

What is interesting about Monson’s ethnomusicological analysis is that she connects musical process to cultural process. From this perspective, we could say that rhythmic repetition is not restricted to the spatio-temporal boundaries of an individual musical event, but can continue across musical instances to the point rhythms become named. Whilst this particular approach to layering multiple rhythms of different periodicities that Monson describes may be a specific characteristic of musics of the African diaspora, cyclically repeated rhythms with named identities play an important part in the musical vocabularies of various musical cultures. For instance, according to Farraj and Shumays (2019) (who also reject the universal applicability of the Western conceptual distinction between rhythm and metre) there is a very diverse range of iqa‘at (cyclical rhythmic patterns that are played by percussion instruments that accompany singers or melodic instruments; singular: iqa‘ ) across the Arab world. Farraj and Shumays (2019) catalogue iqa‘at in relation to time signatures and notate their “skeletons”, which are the basic underlying abstract forms (in practice, the skeletons are nearly always elaborated with ornamentation) including two generic types of drum sounds that can be made across different types of percussion instruments: dum, which is a “bassy sustained sound” and tak, a “sharp and dry sound” (Farraj and Shumays 2019: 88). They also describe iqa‘at in relation to their conventions, characteristic structural features, timing subtleties and affects e.g. in describing two variations of Iqa‘ Hacha‘ they write:

Hacha‘ (also pronounced Hadja‘) is a very popular Iraqi dance iqa‘ that made its way to Syria and beyond. The most basic form of Hacha‘ is in 2/4 and is identical to Wahda Saghira in its notation, except that it is faster and more jumpy. This iqa‘ is used in many folkloric songs from Syria, such as “‘al- maya,” or in Sufi songs such as “tala‘a al- badru ‘alayna.” (Farraj and Shumays 2019: 109)