Abstract

Context

This review was undertaken to provide information concerning the advancement of research in the area of COVID-19 screening and testing during the worldwide pandemic from December 2019 through April 2023. In this review, we have examined the safety, effectiveness, and practicality of utilizing trained scent dogs in clinical and public situations for COVID-19 screening. Specifically, results of 29 trained scent dog screening peer-reviewed studies were compared with results of real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and rapid antigen (RAG) COVID-19 testing methods.

Objectives

The review aims to systematically evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of utilizing trained scent dogs in COVID-19 screening.

Methods

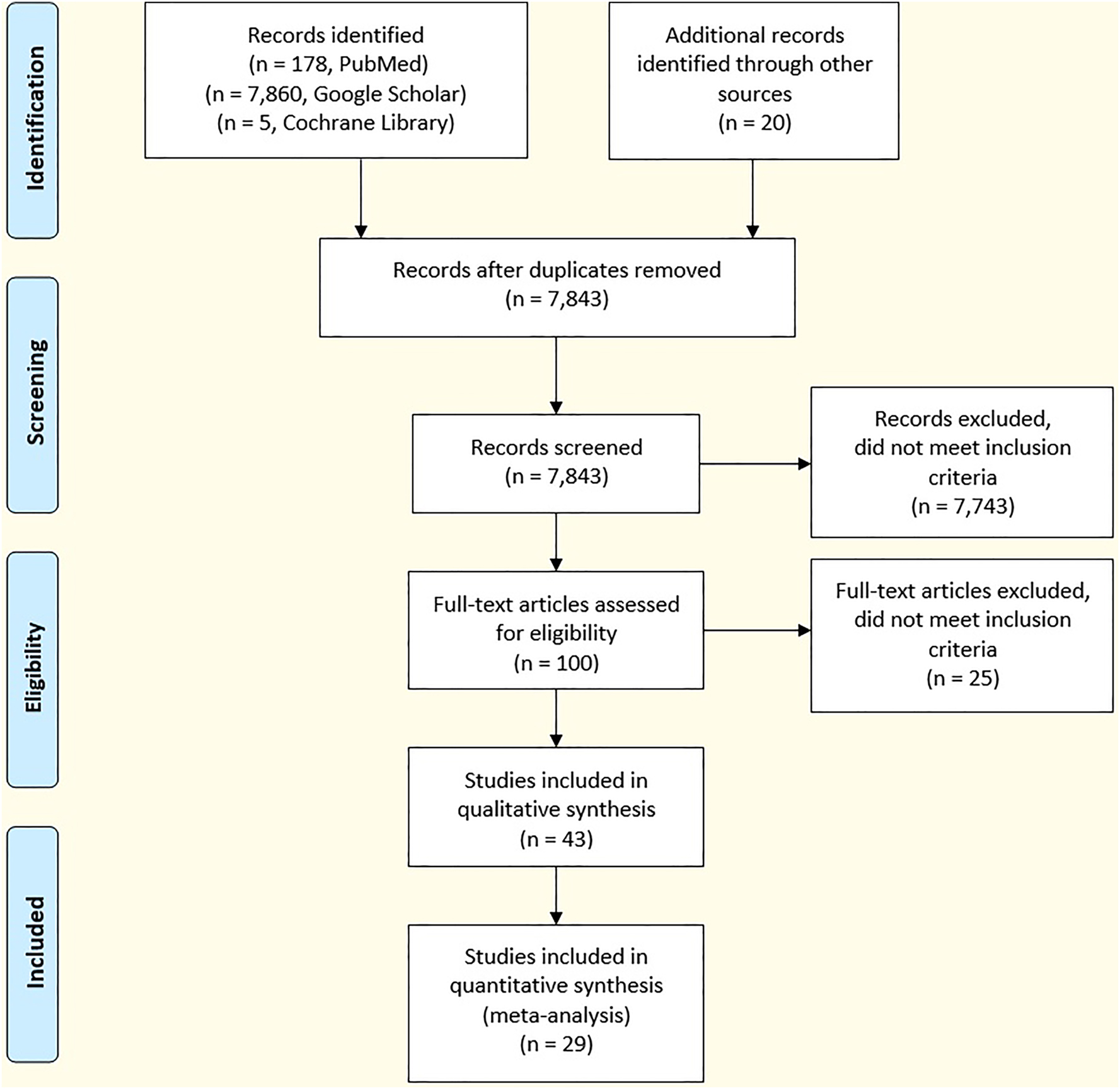

At the time of submission of our earlier review paper in August 2021, we found only four peer-reviewed COVID-19 scent dog papers: three clinical research studies and one preprint perspective paper. In March and April 2023, the first author conducted new literature searches of the MEDLINE/PubMed, Google Scholar, and Cochrane Library websites. Again, the keyword phrases utilized for the searches included “COVID detection dogs,” “COVID scent dogs,” and “COVID sniffer dogs.” The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 Checklist was followed to ensure that our review adhered to evidence-based guidelines for reporting. Utilizing the results of the reviewed papers, we compiled statistics to intercompare and summarize basic information concerning the scent dogs and their training, the populations of the study participants, the types of sampling methods, the comparative tests utilized, and the effectiveness of the scent dog screening.

Results

A total of 8,043 references were identified through our literature search. After removal of duplicates, there were 7,843 references that were screened. Of these, 100 were considered for full-text eligibility, 43 were included for qualitative synthesis, and 29 were utilized for quantitative analysis. The most relevant peer-reviewed COVID-19 scent dog references were identified and categorized. Utilizing all of the scent dog results provided for this review, we found that 92.3 % of the studies reached sensitivities exceeding 80 and 32.0 % of the studies exceeding specificities of 97 %. However, 84.0 % of the studies reported specificities above 90 %. Highlights demonstrating the effectiveness of the scent dogs include: (1) samples of breath, saliva, trachea-bronchial secretions and urine as well as face masks and articles of clothing can be utilized; (2) trained COVID-19 scent dogs can detect presymptomatic and asymptomatic patients; (3) scent dogs can detect new SARS-CoV-2 variants and Long COVID-19; and (4) scent dogs can differentiate SARS-CoV-2 infections from infections with other novel respiratory viruses.

Conclusions

The effectiveness of the trained scent dog method is comparable to or in some cases superior to the real-time RT-PCR test and the RAG test. Trained scent dogs can be effectively utilized to provide quick (seconds to minutes), nonintrusive, and accurate results in public settings and thus reduce the spread of the COVID-19 virus or other viruses. Finally, scent dog research as described in this paper can serve to increase the medical community’s and public’s knowledge and acceptance of medical scent dogs as major contributors to global efforts to fight diseases.

Novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The COVID-19 virus initially appeared in Wuhan, China in December 2019. As of April 26, 2023, over 764 million people had been sickened, and over 6.9 million had died after contracting the COVID-19 virus [1]. The pandemic necessitated concerted worldwide public health efforts to slow the spread of the highly contagious virus. Thus, new COVID-19 screening and testing methods, including the use of trained scent dogs, were developed in a short period of time [2, 3].

Why utilize medical scent dogs? A dog’s sense of smell is its most important sense and the one that enables its use for disease detection [4], [5], [6]. A dog senses and differentiates a broad range of molecules with extremely small concentrations. This capability can be attributed to several factors: (1) a dog’s nose is generally proportionately large; (2) it has 1,094 olfactory receptors compared with a human’s 802; (3) it has 125–300 million olfactory cells compared to 5–6 million for a human; (4) a dog has separate sets of inflow nostrils and outflow folds, enabling efficient odor sampling; and (5) one-third of a dog’s brain is devoted to interpretation of odors compared with only 5 % for a human [4], [5], [6]. It is interesting to note that it has been reported that dogs can detect one part per trillion in n-amyl acetate (nAA), which is about three orders of magnitude better than possible with scientific instrumentation [7]. For illustration, a dog could detect the equivalent of one drop of a liquid in 20 Olympic-size swimming pools or 5 × 1010 mL [7]. Dogs can detect odors/volatile organic compounds (VOCs), which are produced by human tissues that evolve into particular pathologic states associated with specific diseases. The VOCs may originate from flaked-off skin or hair cells, blood, breath, saliva, sweat, tears, nasal mucous, urine, semen, or feces. Dogs likely process and store this odorous information as patterns or smell ‘images’ in their brains. They have already proven successful for the identification of diseases, including malaria, some types of cancers, diabetes, epilepsy, and Parkinson’s disease [6, 8], [9], [10].

Methods

At the time of submission of our earlier review paper [2] in August 2021, we found only four peer-reviewed COVID-19 scent dog papers: three clinical research studies and one preprint perspective paper. In March and April 2023, the first author (TD) conducted new literature searches of the MEDLINE/PubMed, Google Scholar, and Cochrane Library websites. Again, the keyword phrases utilized for the searches included “COVID detection dogs,” “COVID scent dogs,” and “COVID sniffer dogs.” Figure 1 shows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) literature flow chart. The PRISMA 2020 Checklist was followed to ensure that our comprehensive, systematic review adhered to evidence-based guidelines for reporting. In particular, criteria for eliminating papers included: (1) only peer-reviewed papers were included; (2) no gray literature papers were included; (3) no secondhand account papers were included; (4) duplicates were eliminated; and (5) papers not directly related to the objectives of the paper were not included. More than 90 % of the papers included for our review were published during the pandemic; a few relevant background papers and two books written prior to the pandemic were also included. For this paper, the most relevant peer-reviewed COVID-19 scent dog references were identified and categorized as follows: 12 review and perspective papers and reports, 21 papers concerning COVID-19 virus transmission between dogs and humans, 23 clinical scent dog studies Table 1, 6 field scent dog studies (Table 2), and 4 papers devoted to new technologies involving dogs and ENoses (odor sensors), which are electronic devices designed to detect multiple chemical components by mimicking the human or dog olfactory system. Six papers concerned COVID-19 tests utilized for intercomparisons with COVID-19 scent dog research results. Excellent COVID-19 scent dog reviews and perspective papers have been published since the beginning of the pandemic [6, 11], [12], [13], [14], [15]. Finally, it is noted that over 400 scientists from 32 nations have co-authored peer-reviewed papers directly related to COVID-19 scent dog research during the pandemic.

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) literature search flow diagram.

Information for 5 clinical studies.

| Study | Angeletti et al. [16] | Chaber et al. [17] | Demirbas et al. [18] | Devillier et al. [19] | Eskandari et al. [20] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Countries | Italy | Australia, UAE, France | Turkey, Portugal, Germany | France | Iran |

| Study location | Clinic | Clinic | Clinic | Clinic | Clinic |

| No. of samples | n=100 | n=514 | n=29 | n=241 | n=200 |

| No. of dogs (n=) | 3 | 15 | 3 | 7 | 6 |

| Breeds | 1 Black GSD, 1 GSD, 1 Dutch Shep. |

14 Labs, 1 Spaniel |

1 Border Collie, 1 Lab, 1 English Cocker Spaniel |

5 Malinois, 1 Dutch Shepherd, 1 Groenen-dael |

1 GSD, 2 Labs, 1 Germ. Black, 1 Border Gypsy, 1 Retriever |

| Dog ages, yrs | 1–4 | 1–8 | 3–4 | 2–6 | NR |

| Pre-trained | 2 Y, 1 N | 8 Y, 7 N | 1 Y, 2 N | 6 Y, 1 N | Y |

| Training period | 4 weeks | NR | 10 weeks | 8 weeks | 7 weeks |

| Sample type | Sweat | Sweat | Mask, Breath, Droplets | Breath, sweat | Throat, Masks, clothes |

| Comparison test | RT-PCR | RT-PCR | RT-PCR | RT-PCR Bayes. Anal. |

RT-PCR |

| Sensitivity | NR | 95.3 | 91.3–100 | 84.0–88.7 | 65 throat, up to 86 masks/clothes |

| Specificity | NR | 97.1 | 97.2–98.3 | 83.1–89.0 | 89 throat, 92.9 masks and clothes |

| Accuracy | 92–100 | NR | NR | 88 | >80 throat |

| Comments | PPV=49.0–86.6 NPV=89.8–97.5 |

PPV=89.6 NPV=90.3 |

-

GSD, German Shepherd dog; NR, not reported; RT-PCR, reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction; UAE, United Arab Emirates. Percentages are shown to the first decimal when reported by the researchers.

Information for five clinical studies.

| Study | Essler et al. [21] | Grandjean et al. [22] | Grandjean et al. [23] | Grandjean et al. [24] | Guest et al. [25] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Countries | United States | France Lebanon |

France UAE |

France Lebanon |

United Kingdom |

| Study location | Clinic | Clinic | Clinic | Clinic | Clinic |

| No. of samples | n=365 | n=177 | n=335 | n=218 | n=3,921 |

| No. of dogs (n=) | 9 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 6 |

| Breeds | 8 Labs, 1 Malinois |

5 Malinois 1 Jack Russell Terrier |

5 Malinois, 1 Dutch Shepherd, 1 Groenen-dael |

5 Malinois, 1 Dutch Shepherd, 1 Groenen-dael |

1 Cocker Spaniel, 1 Lab Mix, 3 Labs, 1 Golden Retriever |

| Dog ages, yrs | 1.5–6 | 1–8 | 2–6 | 2–6 | 3–8 |

| Pre-trained | NR | Y | Y | Y | NR |

| Training period (n=) | NR | 1–3 weeks | 8 weeks | 8 weeks | 6 weeks |

| Sample type | Urine | Sweat | Sweat (Naso for compar.) | Sweat (Naso for compar.) | Smell, socks, Masks |

| Comparison test | RT-PCR | RT-PCR | RT-PCR | RT-PCR | RT-PCR, sensors, Bayes. Anal. |

| Sensitivity | 71 | NR | 97–100 | 87–94 | 82–94 |

| Specificity | 98 | NR | 91–94 | 78–92 | 76–92 |

| Accuracy | 94 | 76–100 | NR | NR | NR |

| Comments | PPV=84 NPV=99 |

PPV>40 NPV>88 |

-

GSD, German Shepherd dog; NPV, negative predictive value; NR, not reported; RT-PCR, reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction; UAE, United Arab Emirates. Percentages are shown to the first decimal when reported by the researchers.

Information for five clinical studies.

| Study | Hag-Ali et al. [26] | Jendrny et al. [27] | Jendrny et al. [28] | de Maia et al. [29] | Maurer et al. [30] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Countries | UAE, Egypt, Netherlands Kenya |

Germany | Germany | Brazil France |

United States United Kingdom |

| Study location | Clinic | Clinic | Clinic | Clinic | Clinic |

| No. of samples | n=3,290 | n=1,012 | n=5,242 (93 Subjects) | n=100 with flu-like symptom | n=584 Followed by n=153 |

| No. of dogs (n=) | 4 | 8 | 10 | 2 | 3 |

| Breeds | 1 Malinois, 2 Malinois-GSD Mixes, 1 GSD |

1 Dutch Shep. Mix, 1 Dutch Shepherd 3 Labs, 2 Malinois, 1 Span. |

5 Malinois, 3 Labs, 1 GSD, 1 Dutch Shepherd |

NR | Labs |

| Dog ages, yrs | NR | 0.6–8 | 1–9 | NR | 1–5 |

| Pre-trained | Y | 6 Y, 2 N | 5 Y, 5 N | Y | N |

| Training period (n=) | 4 weeks | 1 week | 8 days | NR | 6 weeks |

| Sample type | Sweat | Saliva, Throat |

Urine (U), sweat (Sw), saliva (Sa) | Sweat | Sweat |

| Comparison | RT-PCR Bayes. Anal. |

RT-PCR | RT-PCR | RT-PCR | RT-PCR |

| Sensitivity | 89 | 82.7 | U 98.2, Sw 94.2 Sa 95.5 |

95 Dog 1 100 Dog 2 |

98, 1 Dog 96 |

| Specificity | 99 | 96.4 | U 95.5, Sw 90.9 Sa 81.6 |

NR | 92 |

| Accuracy | NR | 94 | U 95, Sw 91, sa 93 | 97.4 both dogs | NR |

| Comments | Sens. was greater than RT-PCR’s; Spec. was comparable |

PPV=84 NPV=96 |

U PPV=89.9 U NPV=98.7 Sw PPV=76.9 Sw NPV=96.6 Sa PPV=80.0 Sa NPV=96.4 |

PPV=100 NPV=98.2 |

-

GSD, German Shepherd dog; NPV, negative predictive value; NR, not reported; PPV, positive predictive value; RT-PCR, reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction; UAE, United Arab Emirates. Percentages are shown to the first decimal when reported by the researchers.

Information for four clinical studies.

| Study | Mendel et al. [31] | Mutesa et al. [32] | Ozgur-Buyukatalay et al. [33] | Sarkis et al. [34] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Countries | United States | Rwanda Germany Canada |

Turkey | Lebanon France United States |

| Study location | Clinic | Clinic | Clinic | Clinic |

| No. of samples | n=40 | n=5,253 | n=1,002 | n=41 Sympt. n=215 Asympt. |

| No. of dogs (n=) | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| Breeds | 1 Malinois 1 Dutch Shepherd 1 Terrier Mix 1 Collie Mix |

2 Labs 2 Malinois |

1 Lab, 1 English Cocker Spaniel |

2 Belgian Malinois |

| Dog ages, yrs | NR | 2 | 3, 4 | NR |

| Pre-trained | 3 Y, 1 N | Y | Y | N |

| Training period (n=) | 1 month | 5 months | 21 days | 7 months |

| Sample type | Breath Masks |

Sweat | Masks | Sweat |

| Comparison | GC-MS | RT-PCR | RT-PCR | RT-PCR |

| Sensitivity | NR | 75.0–89.9 Delta 36.6–41.5 Omicr. |

50.0 D1 TI, 81.8 D1 TF 42.7 D2 T1, 83.1 D2 TF |

100 Sympt. 100 Asympt. |

| Specificity | NR | 96.1–98.4 Delta >95 Omicr. |

58.0 D1 TI, 60.5 D1 TF 56.2 D2 T1, 60.5 D2 TF |

99 Sympt. 93 Asympt. |

| Accuracy | 96.2–99.4 | NR | 53.6 D1 T1, 67.5 D1 TF 48.8 D1 TI, 69.4 D2 TF |

NR |

| Comments | PPV=87.0–97.6 | PPV=51.9–59.3 Del NPV=98.1–98.9 Del PPV=21.2–41.9 Om NPV=97.6–99.1 Om |

PPV=59.1 D1 TI, 50.4 D1 TF NPV=48.9 D1 TI, 87.2 D1 TF PPV=54.2 D2 TI, 52.5 D2 TF NPV=44.7 D2 TI, 88.2 D2 TF |

-

GC-MS, gas chromatograph-mass spectrometer; GSD, German Shepherd dog; NPV, negative predictive value; NR, not reported; PPV, positive predictive value; RT-PCR, reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction. Percentages are shown to the first decimal when reported by the researchers. For Ozgur-Buyukatalay et al. [33], TI is the initial time of test and TF is the final time of test. Results are for Dog 1 (D1) and Dog 2 (D2) of experiments. The Omicron variant changed between T1 and T2, and virulence decreased between T1 and T2. Retraining was required.

Information for four clinical studies.

| Study | Ten Hagen et al. [35] | Twele et al. [36] | Gokool et al. [37] | Charles et al. [38] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Countries | Germany | Germany | United States | Canada |

| Study location | Clinic | Clinic | Clinic | Clinic |

| No. of samples | n=2,054 | n=732 | n=293 | n=108 |

| No. of dogs (n=) | 12 | Same [27, 28, 35] | 5 | 2 |

| Breeds | 5 Labs, 4 Malinois, 2 GSD, 1 Cocker Spaniel |

Same [27, 28, 35] | 2 GSD, 1 Lab, 1 small Muster-lander, 1 Husky-GSD Mix |

1 English Springer Spaniel, 1 Lab |

| Dog ages, yrs | 1–5 | Same [27, 28, 35] | 3–7 | NR |

| Pre-trained | Y | Y | Y | NR |

| Training period (n=) | 3 days | 3 days | NR | 19 weeks |

| Sample type | Saliva | Saliva, sweat, Urine | T-shirts | Gargle, sweat, Breath/Mask |

| Comparison | RT-PCR | RT-PCR | GC-MS | RT-PCR |

| Sensitivity | 73.8 scen 1 61.2 scen 2 75.8 scen 3 |

86.7 scen 1 94.4 scen 2 86.9 scen 3 |

88 ave. 2 dogs, 46 ave., 3 dogs |

100 |

| Specificity | 95.1 scen 1 90.9 scen 2 90.2 scen 3 |

95.8 scen 1 96.1 scen 2 88.1 scen 3 |

95 ave., 2 dogs, 87 ave., 3 dogs |

87.5 |

| Accuracy | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Comments | PPV=76.8 scen 1 NPV=97.6 scen 1 PPV=76.8 scen 2 NPV=94.8 scen 2 PPV=67.0 scen 3 NPV=94.5 scen 3 |

PPV=82.9 scen 1 NPV=97.3 scen 1 PPV=87.8 scen 2 NPV=98.0 scen 2 PPV=57.1 scen 3 NPV=97.5 scen 3 |

PPV=47.1 NPV=100 |

-

GC-MS, gas chromatograph-mass spectrometer; GSD, German Shepherd dog; NPV, negative predictive value; NR, not reported; PPV, positive predictive value; RT-PCR, reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction. Percentages are shown to the first decimal when reported by the researchers. For Ten Hagen et al. [35], Scen 1: Swab samples were taken from individuals infected with viruses other than SARS-CoV-2 as distractors; Scen 2 and Scen 3: cell culture supernatant from cells infected with SARS-CoV-2, cells infected with other coronaviruses and non-infected cells were presented. For Twele et al. [36], Scen 1: samples of acute COVID-19 vs. Long COVID were utilized, Scen 2: Long COVID and negative control samples were utilized, Scen 3: acute SARS-CoV-2 positive samples and negative control samples were presented.

Information for six field studies.

| Study | Kantele et al. [39] | Mancilla-Tapia et al. [40] | Pirrone et al. [41] | Ten Hagen et al. [42] | Vesga et al. [43] | Glaser et al. [44] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Countries | Finland France |

Mexico Finland |

Italy | Germany | Colombia United States |

United States |

| Study location | Helsinki Airport |

Health center | Public Pharm. | 4 concerts | Direct sniffing: Hospital and Metro System |

K-12 Calif. School |

| No. of samples | n=303 airport | n=138 sweat n=128 saliva | n=360 Labr n=97 Direct |

n=2,802 | n=848 Hosp n=550 Metro |

n=3,897 |

| No. of dogs (n=) | 4 | 6 | 5 | 8 | 5 Hosp 3 Metro |

2 |

| Breeds | 3 Labs, 1 White Shepherd |

2 GSD, 3 Malinois, 1 Unspec. |

1 Malin., 1 Bord. Collie, 2 Gold. Retriev., 1 Mix |

2 Labs, 3 Malin. 1 GSD, 1 GSD Mix, 1 Shep. Mix |

4 Malinois, 1 Malam.-Husky Mix, 1 Pit Bull |

2 Labs |

| Dog ages, yrs (n=) | 4–8 | 1–2 | 3–12 | 2–10 | 0.5–3 | NR |

| Pre-trained | Y | 1 Y, 5 N | 3 Y, 2 N | 6 Y, 2 N | N | Y |

| Training | NR | 12 weeks | 4.5 Mon. | 1–2 weeks | 56 Days | 2 Mon. |

| Sample type | Sweat | Sweat, saliva | Sweat | Sweat | Saliva | Sweat, |

| Comparison | RT-PCR | RT-PCR | RT-PCR Labr, RAD Direct | RAD, RT-PCR |

RT-PCR | RAD |

| Sensitivity | 92 Valid., NR airport |

76, 80 sweat 70, 78 Sal. |

93 Labr 89 Direct |

81.6 | 95.9 Hosp 68.6 Metro |

83 |

| Specificity | 91 Valid. NR airport |

75, 88 sweat NR Sal. |

99 Labr 95 Direct |

99.9 | 95.1 Hosp 94.4 Metro |

90 |

| Accuracy | 92 Valid. 98 airport |

NR | NR | 99.7 | 95.2 Hosp 93.6 Metro |

NR |

| PPV=87.8 Valid. NPV=94.4 Valid. |

PPV=61–86 Sw NPV=62–83 Sw PPV=58–59 Sal NPV=69–85 Sal |

Direct only PPV=68–98 NPV=96–100 |

PPV=70.0 NPV=100 |

PPV=69.7 H NPV=99.5 H PPV=28.2 M NPV=99.0 M |

-

GSD, German Shepherd dog; NPV, negative predictive value; NR, not reported; PPV, positive predictive value; RAD, reactive airway disease; RT-PCR, reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction. Percentages are shown to the first decimal when reported by the researchers. In Pirrone et al. [41], Labr stands for laboratory.

The variables selected for Tables 1 and 2 were chosen to provide key information relevant to the various studies to enable comparisons among them as well as to enable fundamental general statistics to be computed. These include: number of samples, number of dogs, breed types, ages of dogs, training history, sample types, comparison tests, sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value. Not all of this information was available from the reviewed papers. Sensitivity (%) is defined as the number of true positive results divided by the sum of the number of true positives and the number of false positives. Specificity (%) is defined as the number of true negative results divided by the sum of the numbers of true negatives and false negatives. Accuracy (%) is defined as the ratio of true results to the sum of true and false results. Positive predictive value (PPV in %) is the probability that subjects with a positive screening test in fact have the disease. Negative predictive value (NPV in %) is the probability that subjects with a negative screening test truly do not have the disease. These statistics were reported in the individual papers and not calculated by the present authors. Note that not all percentages were reported to the first decimal place in the reviewed papers.

Results

The overarching objective of the present paper is to evaluate the safety, effectiveness, and practicality of utilizing trained scent dog screening for disease outbreaks such as COVID-19 based on relevant peer-reviewed papers published during the pandemic period of December 2019 through April 2023. The present review and synthesis are directed primarily toward medical and healthcare professionals and administrators, who may be interested in the use of medical scent dogs during future epidemics and pandemics or for other medical applications. The following subsections concern: (1) safety considerations; (2) selection and training of dogs; and (3) results of clinical and field studies.

Safety considerations

The safety of scent dogs, their handlers, and those who are inspected by the dogs is critical for the acceptance and implementation of the scent dog screening and testing approach. This is consistent with the One Health paradigm, which defines health as more than the absence of disease and recognizes the interrelationships among humans, animals, and environmental welfare. Two key questions are: (1) Can medical detection dogs contract and become ill with the COVID-19 virus?; and (2) Can dogs pass on the COVID-19 virus to humans? These questions have been addressed in several diverse ways. Some researchers have described a limited number of primarily singular cases of dogs infected with COVID-19 [45–58]. However, Sánchez-Montes et al. [59] sampled 130 dogs and cats in an area of high incidence of the COVID-19 virus and found no infections in the animals. In addition, other relevant studies reported similar negative results [60–63]. Krafft et al. [64] found no strong evidence for pet-to-human transmission or sustained pet-to-pet transmission of SARS-CoV-2. Finally, Damas et al. [65] utilized a comparative genomics approach to study the conservation of the angiotensin I converting enzyme 2 (ACE2). ACE2 is the main receptor of SARS-CoV-2 and was utilized to investigate the possible routes of transmission and sensitivity in different species. They found that dogs were in the low-risk category. To our knowledge, there have been no deaths of dogs that can be unequivocally attributed to COVID-19. Importantly, the studies described above suggest that it is safe for healthy individual handlers to utilize scent dogs to directly screen and test individuals who may be infected with the COVID-19 virus.

Selection and training of scent dogs

Desirable traits for scent detection dogs include: good temperament, lack of aggressiveness, obedient, sociable, independent but able to focus and follow commands, capability to detect and pinpoint low-level scent signals, adaptable to different environments, enjoy working with a handler, high search drive, and endurance and persistence in doing scent work [2, 13], [14], [15]. Less than 5 % of the dogs initially chosen for the studies described in this review were found to be ill-suited for the projects. As shown in Tables 1 and 2, a variety of breeds have been deployed for detecting and screening for COVID-19–infected individuals [16–44]. The previously trained dogs had been utilized for a variety of scent applications such as search and rescue, explosives, narcotics, and police work.

Medical scent dog training methods bear similarities with those for agricultural, explosives, and narcotics detection dogs. The basic principle utilized for scent dog training can be explained with the simple ‘three cup experiment’ utilizing a pet dog (Figure 2). Three upside-down cups, one with a treat under it, are placed on a stand unsighted by the dog. The dog is then allowed to approach the stand. Inevitably, the dog tips over the cup with the treat and enjoys its treat. The training of medical scent dogs is typically done in sanitary laboratory rooms, which utilize lines or wheels with canisters containing items with either targeted odors (VOCs) or distracting odors, or are empty (Figure 2). Dogs are either taken into the laboratory room by a handler or released to find the targets. In the beginning, often a treat is the target but another target odor is gradually added so that the dog learns to identify and associate the second target odor. Then, the treat is eventually removed so that the dog indicates on the new target odor residing in the canister (by standing still, sitting, lying down, or pawing) and is rewarded with a treat or play toy (or complementary clicker sound) for the correct identification. Important aspects are the preparation of training aid samples, their safe containment, and their delivery systems [12, 15]. Key points relevant to COVID-19 scent dog training are made by Maughan et al. [12]: (1) dogs and handlers are necessarily exposed to potentially infectious individuals and samples; (2) background odors can possibly mask the targeted COVID-19–related odor; (3) the COVID-19–produced odor can be extremely faint, necessitating a very low limit of odor detection, which fortunately dogs possess; and (4) personal protection equipment can be required for the highly infectious COVID-19 virus.

![Figure 2:

Illustrations showing how scent dogs are trained and how Enoses are being developed. (A) Illustration of the three cup sniffing experiment with the first author’s Great Pyrenees (photo credit Todd Dickey). (B) One of the second author’s COVID-19 scent dogs sniffing a test canister (photo credit second author). (C) Flowchart illustrating how volatile organic compounds (VOCs) are sensed and processed by dogs and ENoses (flowchart modified after Karakaya et al. [73] With permission).](/document/doi/10.1515/jom-2023-0104/asset/graphic/j_jom-2023-0104_fig_002.jpg)

Illustrations showing how scent dogs are trained and how Enoses are being developed. (A) Illustration of the three cup sniffing experiment with the first author’s Great Pyrenees (photo credit Todd Dickey). (B) One of the second author’s COVID-19 scent dogs sniffing a test canister (photo credit second author). (C) Flowchart illustrating how volatile organic compounds (VOCs) are sensed and processed by dogs and ENoses (flowchart modified after Karakaya et al. [73] With permission).

Results of clinical and field studies

Clinical studies [16–38] are summarized in Table 1, and field studies [39–44] are summarized in Table 2. We found no apparent biases in any of these studies. Two of the recommendations of our earlier review paper [2] were that more studies and samples were needed. Both of these have been satisfied, as evidenced in Tables 1 and 2 with 29 studies involving 147 scent dog deployments and the use of over 31,000 samples or direct scenting of humans. The number of dogs involved in the individual studies ranged from 2 to 15 with a mode of 6 and an average of 6. The number of different breeds and mixed breeds was 19, with Labrador Retrievers (Labs) and Belgian Malinois by far the most commonly utilized (nearly 100 times). These breeds have been utilized extensively in scent detection work for several purposes and have made for easy transitions to the COVID-19 scent work. Other breeds, such as beagles, have been utilized quite successfully as well. No obvious preference based on performance by breed has been reported. The ages of dogs utilized for these studies ranged from 0.5 to 12 years, and both male and female dogs were utilized with neither factor apparently affecting the results. A total of 53 dogs were pretrained, and 37 were previously untrained. The previously untrained dogs’ performances were generally comparable or in some cases slightly superior to those of the pretrained dogs. The previously untrained dogs have the advantage that they are not as prone to indicating on scents other than the COVID-19–associated scent. The training periods for the COVID-19 scent detection studies varied widely from 3 days to 7 months, with the typical training periods lasting a few weeks. This broad variation can be attributed in part to the use of both previously trained dogs and previously untrained dogs as well as the experience of the researchers with scent dogs. The types of samples utilized in these studies included sweat, saliva, throat, urine, masks (sweat droplets), clothes, socks, and T-shirts. Sweat (15) and saliva (7) were the most common sampling modes.

Comparisons of the scent dog results were done primarily with the real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) test [3] or the rapid antigen (RAG) lateral flow test [3]. Both tests are molecular or genetic assays. The RT-PCR test utilizes reverse transcription to obtain DNA, afterwards amplifying the amount by PCR. RT-PCR then detects SARS-CoV-2. The RAG test detects specific proteins on the surface of the virus. The RT-PCR test can detect lower COVID-19 viral load levels than the RAG lateral flow test [3] and has a higher specificity than the RAG test. This is advantageous in initially identifying infected individuals and is the main reason that the RT-PCR test is often labeled as the “Gold Standard Test.” All testing methods, including scent dog testing, are imperfect. The RT-PCR and RAG tests are imperfect because of specimen source, collection and sampling errors, temporal phase of infection, and detectable viral load. Therefore, intercomparisons between the results of these tests and those of the scent dog results must be interpreted with caution and argue for Bayesian analyses, which can be utilized to account for estimated uncertainties in referenced tests [19, 25, 26].

The World Health Organization (WHO) and the German Paul Ehrlich Institute (PEI) have recommended diagnostic sensitivities and specificities for antigen tests to be more than 80 % and more than 97 %, respectively [66]. It has been reported that the RT-PCR test has sensitivities ranging from 32 to 97 % and specificities ranging from 90 to 100 % [67–69]. Based on another report [70], RAG tests have shown sensitivities of 34–90 % and specificities of 58–99 %. Utilizing the scent dog results provided for this review in Tables 1 and 2, we found that 92.3 % of the studies reached sensitivities exceeding 80 and 32.0 % of the studies exceeded specificities of 97 %. However, 84.0 % of the studies reported specificities above 90 %. We thus suggest that the scent dog method can yield results at least comparable to those of the RT-PCR and RAG tests. Some specific findings from the scent dog clinical studies (see Table 1) are highlighted as follows: (1) samples of breath, saliva, trachea-bronchial secretions, and urine as well as face masks and articles of clothing can be effectively utilized for sampling (Table 1); (2) trained COVID-19 scent dogs have demonstrated a capability to detect presymptomatic and asymptomatic patients who are less likely to be screened because they do not suspect that they are infected [22]; (3) the capability of scent dogs was analyzed with respect to the vaccination status of the subjects [19]; (4) it was found that some scent dogs can generalize the odor of COVID-19 with the same accuracy rate when exposed to new SARS-CoV-2 variants for which they have not previously been trained to detect [33]; (5) the scent dogs utilized by Ten Hagen et al. [35, 42] were able to differentiate SARS-CoV2 infections from infections with other novel coronaviruses, influenza viruses, parainfluenza viruses, an adenovirus, a rhinovirus, a metapneumovirus (human metapneumovirus [HMPV]), and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), which are all etiological agents common to respiratory tract infections [35, 42]; (6) scent dogs identified samples of Long COVID-19 patients with a high sensitivity [36]; and (7) the use of Bayesian statistical models [19, 25, 26] and gas chromatograph-mass spectrometers (GC-MSs) [31, 37], can be useful analytical approaches.

The deployment of scent dogs for the detection of COVID-19 in the public sector was a recommendation and a goal of authors early on during the pandemic [2]. Maughan et al. [12] have illustrated three in-person screening methods (see their Figure 2) as follows: (1) individuals or samples are separated from the scent dogs by a barrier or in a separate room while their samples (e.g., sweat) are sniffed by the dogs; (2) individuals pass through an area separated from the scent dogs by a permeable screen or high-efficiency particulate air filter, possibly utilizing a fan forcing air from the individuals to the awaiting scent dogs on the opposite side; and (3) the scent dog team screens by directly sniffing individuals en masse or in a lineup. The two primary field sampling modes utilized in the studies described here are: (1) collection of a sample that is presented immediately to a dog and quickly sniffed, giving a result within a few minutes; and (2) direct sniffing of individuals giving a result in seconds.

Peer-reviewed papers dedicated to public sector deployments are summarized in Table 2. The venues for these studies included: the Helsinki International Airport [39], a Mexican health center [40], community public pharmacies in Italy [41], four concerts in Germany [42], a Metro system in Colombia [43], and a K-12 school in California [44]. A brief summary of the results of these six field studies follows. The sample types were sweat or saliva. Comparisons were done with RT-PCR tests four times and with RAG tests twice. Field values of sensitivity ranged from 68.6 to 95.9 %, with 3 of the 6 ranging between 92.0 and 95.9 %. Specificities ranged from 75.0 to 99.9 %, with 3 of the 6 ranging between 95.1 and 99.9 %. These results are similar to and in some cases better than the clinical study results as well as the RT-PCR and RAG test results.

Interestingly, the speed of in-person screening is exemplified by the concert studies of Ten Hagen et al. [42], who were able to do a lineup with 40 samples including sample collection, lineup loading, and unloading within only 3 min [42]. Other venues have been utilized over the past 3 years as well. Peer-reviewed papers are yet to be published on COVID-19 scent dog work done at assisted living facilities, universities, movie sets, and sporting events. Some specific COVID-19 scent dog screenings done by the second author are worth mentioning. For example, COVID-19 scent dog screening was done at an entertainment event in Georgia in April 2021. There, approximately 3,500 people were screened, resulting in positive indications of eight people by the beagle scent dogs. Additional screening was done at a concert in Texas and two festivals in Florida. Finally, Maughan et al. [12] describe a variety of additional potential venues suitable for field screenings. These include transportation hubs, ships, farms, worksites, buildings, border crossings, and prisons.

Discussion

The time between RT-PCR sampling and the return of results can be up to days, whereas the RAG test results are obtained within about 15 min. Again, if scent dogs directly sniff individuals, results are learned in seconds or a few minutes if samples are taken and sniffed soon after by the dogs [39–44] (see Table 2). Crozier et al. [3] have illustrated (see their Figure 1) that the time from exposure to the COVID-19 virus to the infectious/symptomatic stage occurs within a few days. This rapid increase in viral load indicates the importance of early and frequent screening of individuals with methods that are capable of both early detection of low viral load and fast return of results. Ideally, individuals who are asymptomatic, presymptomatic, or pauci-symptomatic (i.e., subclinical) would test positive along with symptomatic individuals. Importantly, rapid return of the testing or screening results (e.g., utilizing the RAG test or scent dogs rather than the RT-PCR test) is important for isolation or quarantining of infected individuals to minimize interactions with uninfected individuals. The criticality of the speed of the return of test results cannot be overemphasized [3, 26, 71]. Finally, an interesting point suggested by one of the reviewers of this paper follows. People carry viruses in different quantities and in different places. Therefore, RAG and RT-PCR samples from nasal cavity or saliva might not catch infections in all people. However, scent dogs, which directly sniff subjects, can locate the viral infection in the “whole person.” This attribute places into context individuality and a holistic view embraced by osteopathic medicine.

Thus, is the RT-PCR, RAG, or scent dog test better for public health screening and testing? There are good arguments for each one. Interestingly, Hag-Ali [26] challenged the RT-PCR test as being the “Gold Standard” COVID-19 test with respect to multiple aspects. They utilized Bayesian statistical analyses in their scent dog study, which sampled 3,134 nasal swabs and found that the sensitivity of their scent dog–based test was superior to the RT-PCR test. In addition, the specificity of the two testing methods were nearly identical. They concluded that the scent dog method with its high sensitivity, short turnaround time, low cost, lack of invasiveness, and ease of application “lends itself as a better alternative to the RT-PCR in screening for COVID-19 in asymptomatic individuals.” Other studies included in this paper are generally consistent with this conclusion. Further, the scent dog approach has much less of an environmental impact than the other common tests.

Limitations to the peer-reviewed studies were articulated by their authors. For example: (1) proper criteria for lengths of training periods and switching from training to testing mode need to be determined [21, 24, 28]; (2) nearby distracting noises, smells, or naturally occurring weather conditions can be distracting and limit accuracy [22, 42, 44]; (3) a participant’s disease status can change during the time (i.e., up to 72 h) between the dog test and the reference RT-PCR or RAG test [17, 30, 33]; (4) a dog’s exposure time to a sample may be too short [40]; (5) false-positive rates of the dogs may actually reflect false-negative rates of the RT-PCR or RAG test [17, 21, 22, 24, 26, 33, 40, 42], in which case dogs may become discouraged [21]; (6) more dogs are needed for some experiments, because 8 of the 29 studies in this review had only two or three dogs [16, 18, 29, 30, 33, 34, 38, 44]; (7) more positive samples were needed, especially toward the end of the pandemic, when there were minimal numbers of positive cases [18–20, 25, 32, 39, 43, 44]; (8) dogs may become frustrated when too few positive cases are presented, [17, 28]; (9) variability of performance from one dog to another under the same conditions needs to be understood [27]; and (10) some, but not all, studies suggested that refresher training was needed to accurately detect new COVID-19 variants [32, 33, 39].

In addition to the questions and limitations described above, others need to be addressed for the routine use of medical scent dogs for in-person screening [3, 12, 13]. Examples include: (1) More dogs would need to be rapidly trained and deployed during future epidemics and pandemics [12, 13, 23]. The training and field use of scent dogs may benefit from the recruitment of dog owners who are already involved in recreational scent work under the auspices of the American Kennel Club and other organizations worldwide. (2) Is the use of scent dogs cost-effective? Some of the research in this review was in fact motivated by the need for inexpensive testing in developing nations [29, 32, 42, 43]. One study found that the scent dog method was cheaper than the RAG test [32]. More economic research is needed [13]. (3) Working scent dogs still have their own basic needs such as rest, sleep, eating, play, and basic companionship. Like humans, they can have off-days, which the handler needs to recognize and properly react to and utilize backup dogs [12]. (4) During deployments, handlers must be aware that some people may have allergies, be afraid of or uncomfortable with dogs, or feel stigmatized by being positively indicated by a dog [13]. (5) The screening process requires a team effort between the dog and handler, who must have a close relationship [12]. (6) Finally, the implementation of wide-scale in-person programs will require funding and development of infrastructure that is responsible for certification, protocol standards, and deployments [3, 12, 13, 23].

Can dogs be utilized in developing new diagnostic instrumentation and sensors? As a point of reference, one of the peer-reviewed studies [43] reported that the limit of detection (LOD) for four of their dogs was lower than 2.6 × 10−12 copies ssRNA/mL, which is the equivalent of detecting a drop (0.05 mL) of any odorous substance dissolved in a volume of water greater than the capacity of 10.5 Olympic swimming pools or 2.6 × 1010 mL. This capability surpasses today’s available instruments by three orders of magnitude [9]. There is a fundamental need to determine which VOC is specific to SARS-CoV-2 infection and to assess its persistence. Only within the past few decades has the science of smell made major advances in the quest to identify odors and VOCs. GC-MSs have become major tools to analyze smells in cancer research [72]. They have also already been utilized for COVID-19 research [31, 37]. However, GC-MSs are large, require technical training, and are expensive. As alternatives to GC-MSs, miniaturized electronic devices called ENoses are being developed to detect multiple chemical components (odors) by mimicking the human or dog olfactory system [73]. Briefly, the concept, as illustrated in Figure 2, is to intake sample VOCs, which are sensed by miniaturized chemical sensor arrays (analogous to a dog’s nose), and then processed/analyzed (via pattern recognition/analysis as by a dog’s brain) utilizing methods such as artificial neural networks (ANNs) to determine the presence or absence of a specific chemical or virus such as the COVID-19 virus [74]. Dogs can be utilized to train the ENose. A long-term goal is to develop wearable medical sensors for detecting diseases (i.e., based on ENoses) as well as fundamental physiological indicators such as heart rate, blood pressure, oxygen, and others [75].

Conclusions

Our literature search shows a remarkable, nearly ten-fold increase in COVID-19 scent dog research over the past 2 years. Based on our extensive review, which includes results of 29 COVID-10 scent dog experiments, we came to the following conclusions. It is safe for healthy individual handlers to utilize scent dogs to directly screen and test individuals who may be infected with the COVID-19 virus. The effectiveness of the trained scent dog method is comparable to or in some cases superior to the real-time RT-PCR test and the antigen (RAG) test. Trained scent dogs can be effectively utilized to provide quick (seconds to minutes), nonintrusive, and accurate results in public settings and thus reduce the spread of the COVID-19 virus or other viruses. Finally, scent dog research as described in this paper can serve to increase the medical community’s and public’s knowledge and acceptance of medical scent dogs as major contributors to global efforts to fight diseases.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Dr. Diclehan Karakaya Ulucan for granting us permission to use and modify their Figure 1 from the following paper: Karakaya, D, Ulucan, O, Turkan, M. Electronic nose and its applications: a survey. Int J Autom Comput 2020;17:179–209.

-

Research funding: None reported.

-

Author contributions: Both authors provided substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; both authors drafted the article or revised it critically for important intellectual content; both authors contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data; both authors gave final approval of the version of the article to be published; and both authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

-

Competing interests: Heather Junqueira is the owner of BioScent, Inc.

References

1. World Health Organization (WHO) Website. Coronavirus (COVID-19) dashboard [Updated April 26, 2023]. https://covid19.who.int/ [Accessed 1 May 2023].Suche in Google Scholar

2. Dickey, T, Junqueira, H. Toward the use of medical scent dogs for COVID-19 screening. J Osteopath Med 2021;121:141–8. https://doi.org/10.1515/jom-2020-0222.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

3. Crozier, A, Rajan, S, McKee, M. Put to the test: use of rapid testing technologies for covid-19. BMJ 2021;372:n208. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n208.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

4. Rosell, F. Secrets of the snout. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2014:265 p.Suche in Google Scholar

5. Goodavage, M. Doctor dogs. New York: Dutton publishing; 2019:353 p.Suche in Google Scholar

6. Kokocińska-Kusiak, A, Woszczyło, M, Zybala, M, Maciocha, J, Barłowska, K, Dzięcioł, M. Canine olfaction: physiology, behavior, and possibilities for practical applications. Animals 2021;11:2463. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11082463.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

7. Walker, DB, Walker, JC, Cavnar, PJ, Taylor, JL, Pickel, DH, Hall, SB, et al.. Naturalistic quantification of canine olfactory sensitivity. Appl Anim Behav Sci 2006;97:241–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2005.07.009.Suche in Google Scholar

8. Bijland, LA, Bomers, MK, Smulders, YM. Smelling the diagnosis: a review on the use of scent in diagnosing disease. Neth J Med 2013;71:300–7.Suche in Google Scholar

9. Angle, C, Waggoner, LP, Ferrando, A, Haney, P, Passer, T. Canine detection of the volatilome: a review of implications for pathogen and disease detection. Front Vet Sci 2016;3:4–7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2016.00047.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

10. Junqueira, H, Quinn, T, Biringer, R, Hussein, M, Smiriglio, C, Barrueto, et al.. Accuracy of canine scent detection of non–small cell lung cancer in blood serum. J Am Osteopath Assoc 2019;119:413–8. https://doi.org/10.7556/jaoa.2019.077.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

11. D’Aniello, B, Pinelli, C, Varcamonti, MRM, Lombardi, P, Scandurra, A. COVID sniffer dogs: technical and ethical concerns. Front Vet Sci 2021;8:669712. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2021.669712.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

12. Maughan, MN, Best, EM, Gadberry, JD, Sharpes, CE, Evans, KL, Chue, CC, et al.. The use and potential of biomedical detection dogs during a disease outbreak. Front Med 2022;9:848090. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2022.848090.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

13. Otto, CM, Sell, TK, Veenema, TG, Hosangadi, D, Vahey, RA, Connell, ND, et al.. The promise of disease detection dogs in pandemic response: lessons learned from COVID-19. Disaster Med Public Health Prep 2021;17:e20. https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2021.183.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

14. Sakr, R, Ghsoub, C, Rbeiz, C, Lattouf, V, Riachy, R, Haddad, et al.. COVID-19 detection by dogs: from physiology to field application-a review article. Postgrad Med 2022;98:212–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/postgradmedj-2020-139410.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

15. Meller, S, Al Khatri, MSA, Alhammadi, HK, Álvarez, G, Alvergnat, G, Alves, LC, et al.. Expert considerations and consensus for using dogs to detect human SARS-CoV-2-infections. Front Med 2022;9:1015620. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2022.1015620.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

16. Angeletti, S, Travaglino, F, Spoto, S, Pascarella, MC, Mansi, G, De Cesaris, M, et al.. COVID-19 sniffer dog experimental training: which protocol and which implications for reliable identification? J Med Virol 2021;93:5924–30. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.27147.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

17. Chaber, AL, Hazel, S, Matthews, B, Withers, A, Alvergnat, G, Grandjean, D, et al.. Evaluation of canine detection of COVID-19 infected individuals under controlled settings. Transbound Emerg Dis 2022;69:e1951–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/tbed.14529.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

18. Demirbas, YS, Kismali, G, Saral, B, Sareyyupoglu, B, Habiloglu, AD, Ozturk, H, et al.. Development of a safety protocol for training and using SARS-CoV-2 detection dogs: a pilot study. J Vet Behav 2023;60:79–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jveb.2023.01.002.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

19. Devillier, P, Gallet, C, Salvator, H, Lecoq-Julien, C, Naline, E, Roisse, D, et al.. Biomedical detection dogs for identification of SARS-CoV-2 infections from axillary sweat and breath samples. J Breath Res 2022;16. https://doi.org/10.1088/1752-7163/ac5d8c.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

20. Eskandari, E, Ahmadi Marzaleh, M, Roudgari, H, Hamidi Farahani, R, Nezami-Asl, A, Laripour, R, et al.. Sniffer dogs as a screening/diagnostic tool for COVID-19: a proof of concept study. BMC Infect Dis 2021;21:243. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-021-05939-6.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

21. Essler, JL, Kane, SA, Nolan, P, Akaho, EH, Berna, AZ, DeAngelo, A, et al.. Discrimination of SARS-CoV-2 infected patient samples by detection dogs: a proof of concept study. PLoS One 2021;16:e0250158. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0250158.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

22. Grandjean, D, Sarkis, R, Lecoq-Julien, C, Benard, A, Roger, V, Levesque, E, et al.. Can the detection dog alert on COVID-19 positive persons by sniffing axillary sweat samples? A proof-of-concept study. PLoS One 2020;15:e0243122. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0243122.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

23. Grandjean, D, Elie, C, Gallet, C, Julien, C, Roger, V, Desquilbet, L, et al.. Diagnostic accuracy of non-invasive detection of SARS-CoV-2 infection by canine olfaction. PLoS One 2022a;17:e0268382. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0268382.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

24. Grandjean, D, Gallet, C, Julien, C, Sarkis, R, Muzzin, Q, Roger, V, et al.. Identifying SARS-COV-2 infected patients through canine olfactive detection on axillary sweat samples; study of observed sensitivities and specificities within a group of trained dogs. PLoS One 2022b;17:e0262631. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0262631.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

25. Guest, C, Dewhirst, SY, Lindsay, SW, Allen, DJ, Aziz, S, Baerenbold, O, et al.. Using trained dogs and organic semi-conducting sensors to identify asymptomatic and mild SARS-CoV-2 infections: an observational study. J Trav Med 2022;29:taac043. https://doi.org/10.1093/jtm/taac043.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

26. Hag-Ali, M, AlShamsi, AS, Boeijen, L, Mahmmod, Y, Manzoor, R, Rutten, H, et al.. The detection dogs test is more sensitive than real-time PCR in screening for SARS-CoV-2. Commun Biol 2021;4:686. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-021-02232-9.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

27. Jendrny, P, Schulz, C, Twele, F, Meller, S, von Köckritz-Blickwede, M, Osterhaus, ADME, et al.. Scent dog identification of samples from COVID-19 patients-a pilot study. Inf Disp 2020;20:536. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-020-05281-3.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

28. Jendrny, P, Twele, F, Meller, S, Schulz, C, von Köckritz-Blickwede, M, Osterhaus, ADME, et al.. Scent dog identification of SARS-CoV-2 infections in different body fluids. BMC Infect Dis 2021;21:707. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-021-06411-1.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

29. de Maia, RCC, Alves, LC, da Silva, JES, Czyba, FR, Pereira, JA, Soistier, V, et al.. Canine olfactory detection of SARS-CoV-2 infected patients: a One Health approach. Front Public Health 2021;9:647903. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.647903.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

30. Maurer, M, Seto, T, Guest, C, Somal, A, Julian, C. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 by canine olfaction: a pilot study. Open Forum Infect Dis 2022;9:ofac226. https://doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofac226.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

31. Mendel, J, Frank, K, Edlin, L, Hall, K, Webb, D, Mills, J, et al.. Preliminary accuracy of COVID-19 odor by canines and HS-SPME-GC-MS using exhaled breath samples. Forensic Sci Int: Syn 2021;3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fsisyn.2021.100155.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

32. Mutesa, L, Misbah, G, Remera, E, Ebbers, H, Schalke, E, Tuyisenge, P, et al.. Use of trained scent dogs for detection of COVID-19 and evidence of cost-saving. Front Med 2022;9:1006315. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2022.1006315.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

33. Ozgur-Buyukatalay, E, Demirbas, YS, Bozdayi, G, Kismali, G, Ilhan, MN. Is diagnostic performance of SARS-CoV-2 detection dogs reduced -due to virus variation- over the time. Appl Anim Behav Sci 2023;258:105825. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2022.105825.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

34. Sarkis, R, Lichaa, A, Mjaess, G, Saliba, M, Selman, C, Lecoq-Julien, C, et al.. New method of screening for COVID-19 disease using sniffer dogs and scents from axillary sweat samples. J Public Health 2022;44:e36–41. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdab215.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

35. Ten Hagen, NA, Twele, F, Meller, S, Jendrny, P, Schulz, C, von Köckritz-Blickwede, M, et al.. Discrimination of SARS-CoV-2 infections from other viral respiratory infections by scent dog detection dogs. Front Med 2021;8:749588. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2021.749588.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

36. Twele, F, Ten Hagen, NA, Meller, S, Schulz, C, Osterhaus, A, Jendrny, P, et al.. Detection of post-COVID-19 patients using medical scent detection dogs – a pilot study. Front Med 2022;9:877259. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2022.877259.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

37. Gokool, VA, Crespo-Cajigas, J, Mallikarjun, A, Collins, A, Kane, SA, Plymouth, V, et al.. The use of biological sensors and instrumental analysis to discriminate COVID-19 odor signatures. Biosensors 2022;12:1003. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios12111003.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

38. Charles, M, Eckbo, E, Zurberg, T, Woznow, T, Aksu, L, Navas, LG, et al.. In search of COVID-19: the ability of biodetection canines to detect COVID-19 odours from clinical samples. JAMMI 2022;7:343–9. https://doi.org/10.3138/jammi-2022-017.Suche in Google Scholar

39. Kantele, A, Paajanen, J, Turunen, S, Pakkanen, SH, Patjas, A, Itkonen, L, et al.. Scent dogs in detection of COVID-19: triple-blinded randomized trial and operational real-life screening in airport setting. BMJ Glob Health 2022;7:e008024. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2021-008024.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

40. Mancilla-Tapia, JM, Lozano-Esparza, V, Orduña, A, Osuna-Chávez, RF, Robles-Zepeda, RE, Maldonado-Cabrera, B, et al.. Dogs detecting COVID-19 from sweat and saliva of positive people: a field experience in Mexico. Front Med 2022;9:837053. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2022.837053.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

41. Pirrone, F, Piotti, P, Galli, M, Gasparri, R, La Spina, A, Spaggiari, L, et al.. Sniffer dogs performance is stable over time in detecting COVID-19 positive samples and agrees with rapid antigen test in the field. Sci Rep 2023;13:3679. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-30897-1.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

42. Ten Hagen, NA, Twele, F, Meller, S, Wijnen, L, Schulz, C, Schoneberg, C, et al.. Canine real-time detection of SARS-CoV-2 infections in the context of a mass screening event. BMJ Glob Health 2022;7:e010276. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2022-010276.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

43. Vesga, O, Agudelo, M, Valencia-Jaramillo, AF, Mira-Montoya, A, Ossa-Ospina, F, Ocampo, E, et al.. Highly sensitive scent-detection of COVID-19 patients in vivo by trained dogs. PLoS One 2021;16:e0257474. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0257474.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

44. Glaser, CA, Le Marchand, CE, Rizzo, K, Bornstein, L, Messenger, S, Edwards, CA, et al.. Lessons learned from a COVID-19 dog screening pilot in California K-12 schools. JAMA Pediatr 2023:177:644–6. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2023.0489.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

45. Sit, THC, Brackman, CJ, Ip, SM, Tam, KWS, Law, PYT, To, EMW, et al.. Infection of dogs with SARS-CoV-2. Nature 2020;586:776–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2334-5.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

46. Leroy, EM, Goulih, MA, Brugere-Picpux, J. The risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission to pets and other wild and domestic animals strongly mandates a one-health strategy to control the COVID-19 pandemic. One Health 2020;10:100133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.onehit.2020.100133.Suche in Google Scholar

47. Medkour, H, Catheland, S, Boucraut-Baralon, C, Laidoudi, Y, Sereme, Y, Pingret, JL, et al.. First evidence of human-to-dog transmission of SARS-CoV-2 B.1.160 variant in France. Transbound Emerg Dis 2022;69:e823–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/tbed.14359.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

48. de Souza Barbosa, AB, Kmetiuk, LB, de Carvalho, OV, Brandão, APD, Doline, FR, Lopes, SRRS, et al.. Infection of SARS-CoV-2 in domestic dogs associated with owner viral load. Res Vet Sci 2022;153:61–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rvsc.2022.10.006.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

49. Fritz, M, Rosolen, B, Krafft, E, Becquart, P, Elguero, E, Vratskikh, O, et al.. High prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in pets. One Health 2021;11:100192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.onehlt.2020.100192.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

50. Alberto-Orlando, S, Calderon, JL, Leon-Sosa, A, Patiño, L, Zambrano-Alvarado, MN, Pasquel-Villa, LD, et al.. ARS-CoV-2 transmission from infected owner to household dogs and cats is associated with food sharing. Int J Infect Dis 2022;122:295–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2022.05.049.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

51. Hamer, SA, Ghai, RR, Zecca, IB, Auckland, LD, Roundy, CM, Davila, E, et al.. SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.7 variant of concern detected in a pet dog and cat after exposure to a person with COVID-19, USA. Transbound Emerg Dis 2022;69:1656–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/tbed.14122.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

52. Lee, DH, Helal, ZH, Kim, J, Hunt, A, Barbieri, A, Tocco, N, et al.. Severe acute respiratory syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in a dog in Connecticut in February 2021. Viruses 2021;13:2141. https://doi.org/10.3390/v13112141.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

53. Barroso-Arévalo, S, Rivera, B, Domínguez, L, Sánchez-Vizcaíno, JM. First detection of SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.7 variant of concern in an asymptomatic dog in Spain. Viruses 2021;13:1379. https://doi.org/10.3390/v13071379.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

54. Fernández-Bastit, L, Rodon, J, Pradenas, E, Marfil, S, Trinité, B, Parera, M, et al.. First detection of SARS-CoV-2 Delta (B.1.617.2) variant of concern in a dog with clinical signs in Spain. Viruses 2021;13:2526. https://doi.org/10.3390/v13122526.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

55. Kuhlmeier, E, Chan, T, Agüí, CV, Willi, B, Wolfensberger, A, Beisel, C, et al.. Detection and molecular characterization of the SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant and the specific immune response in companion animals in Switzerland. Viruses 2023;15:245. https://doi.org/10.3390/v15010245.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

56. Jeon, GT, Kim, HR, Kim, JM, Baek, JS, Shin, YK, Kwon, OK, et al.. Tailored multiplex real-time RT-PCR with species-specific internal positive controls for detecting SARS-CoV-2 in canine and feline clinical samples. Animals 2023;13:602. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani13040602.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

57. Panei, CJ, Bravi, ME, Moré, G, De Felice, L, Unzaga, JM, et al.. Serological evidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in pets naturally exposed during the COVID-19 outbreak in Argentina. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 2022;254:110519. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetimm.2022.110519.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

58. Guo, R, Wolff, C, Prada, JM, Mughini-Gras, L. When COVID-19 sits on people’s laps: a systematic review of SARS-CoV-2 infection prevalence in household dogs and cats. One Health 2023;16:100497. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.onehlt.2023.100497.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

59. Sánchez-Montes, S, Ballados-González, GG, Gamboa-Prieto, J, Cruz-Romero, A, Romero-Salas, D, Pérez-Brígido, CD, et al.. No molecular evidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in companion animals from Veracruz, Mexico. Transbound Emerg Dis 2022;69:2398–403. https://doi.org/10.1111/tbed.14153.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

60. Suharsono, H, Mukti, AG, Suryana, K, Tenaya, IWM, Pradana, DK, Daly, G, et al.. Preliminary study of coronavirus disease 2019 on pets in pandemic in Denpasar, Bali, Indonesia. Vet World 2021;14:2979–83. https://doi.org/10.14202/vetworld.2021.2979-2983.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

61. Temmam, S, Barbarino, A, Maso, D, Behillil, S, Enouf, V, Huon, C, et al.. Absence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in cats and dogs in close contact with a cluster of COVID-19 patients in a veterinary campus. Health 2020;10:100164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.onehlt.2020.100164.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

62. Akhtardanesh, B, Jajarmi, M, Shojaee, M, Salajegheh, Tazerji, S, Khalili Mahani, M, et al.. Molecular screening of SARS-CoV-2 in dogs and cats from households with infected owners diagnosed with COVID-19 during Delta and Omicron variant waves in Iran. Vet Med Sci 2023;9:82–90. https://doi.org/10.1002/vms3.1036.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

63. Dróżdż, M, Krzyżek, P, Dudek, B, Makuch, S, Janczura, A, Paluch, E. Current state of knowledge about the role of pets in zoonotic transmission of SARS-CoV-2. Viruses 2021;13:1149. https://doi.org/10.3390/v13061149.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

64. Krafft, E, Denolly, S, Boson, B, Angelloz-Pessey, S, Levaltier, S, Nesi, N, et al.. Report of one-year prospective surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 in dogs and cats in France with various exposure risks: confirmation of a low prevalence of shedding, detection and complete sequencing of an alpha variant in a cat. Viruses 2021;13:1759. https://doi.org/10.3390/v13091759.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

65. Damas, J, Hughes, GM, Keough, KC, Painter, CA, Persky, NS, Corbo, M, et al.. Broad host range of SARS-CoV-2 predicted by comparative and structural analysis of ACE2 in vertebrates. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2020;117:22311–22. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2010146117.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

66. Wiersinga, WJ, Rhodes, A, Cheng, AC, Peacock, SJ, Prescott, HC. Pathophysiology, transmission, diagnosis, and treatment of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a review. JAMA 2020;324:782–93. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.12839.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

67. Ghoshal, U, Vasanth, S, Tejan, N. A guide to laboratory diagnosis of Corona Virus Disease-19 for the gastroenterologists. Indian J Gastroenterol 2020;39:236–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12664-020-01082-3.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

68. Boger, B, Fasci, MM, Vilhena, RO, Cobre, AF, Tonin, FS, Pontarolo, R. Systematic review with meta-analysis of the accuracy of diagnostic tests for COVID-19. Am J Infect Control 2021;49:21–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2020.07.011.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

69. Dinnes, J, Deeks, JJ, Berhane, S, Taylor, M, Adriano, A, Davenport, C, et al.. Rapid, point-of- care antigen and molecular-based tests for diagnosis of SARS-VoC-2 infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2021;3:CD013705. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD013705.10.1002/14651858.CD013705Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

70. Paul-Ehrlich-Institut. Mindestkriterien für SARS-CoV-2 Antigentests im Sinne von §1 Abs. 1 Satz 1 TestVO: antigenschnelltests. 2022. https://www.pei.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/DE/newsroom/dossiers/mindestkriterien-sars-cov-2-antigentests.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=9 [Accessed April, 2023].Suche in Google Scholar

71. Larremore, DB, Wilder, DB, Lester, E, Shehata, S, Burke, JM, Hay, JA, et al.. Test sensitivity is secondary to frequency and turn-around times for COVID-19 screening. Sci Adv 2021;7. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abd5393.10.1126/sciadv.abd5393Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

72. Guest, C, Harris, R, Sfanos, KS, Shrestha, E, Partin, AW, Trock, B, et al.. Feasibility of integrating canine olfaction with chemical and microbial profiling of urine to detect lethal prostate cancer. PLoS One 2021;16:e0245530. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0245530.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

73. Karakaya, D, Ulucan, O, Turkan, M. Electronic nose and its applications: a survey. Int J Autom Comput 2020;17:179–209.10.1007/s11633-019-1212-9Suche in Google Scholar

74. Snitz, K, Andelman-Gur, M, Pinchover, L, Weissgross, R, Weissbrod, A, Mishor, E, et al.. Proof of concept for real- time detection of SARS CoV-2 infection with an electronic nose. PLoS One 2021;16:e0252121. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0252121.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

75. Ates, HC, Nguyen, PQ, Gonzalez-Macia, L, Morales-Narváez, E, Güder, F, Collins, JJ, et al.. End-to-end design of wearable sensors. Nat Rev Mater 2022;7:887–907. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41578-022-00460-x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- General

- Review Article

- COVID-19 scent dog research highlights and synthesis during the pandemic of December 2019−April 2023

- Medical Education

- Original Articles

- Key factors for residency interview selection from the National Resident Matching Program: analysis of residency Program Director surveys, 2016–2020

- Ultrasound-assisted bony landmark palpation in untrained palpators

- Musculoskeletal Medicine and Pain

- Original Article

- Educational intervention promotes injury prevention adherence in club collegiate men’s lacrosse athletes

- Neuromusculoskeletal Medicine (OMT)

- Clinical Practice

- Counterstrain technique for anterior and middle scalene tender point

- Public Health and Primary Care

- Brief Report

- Preventing quality improvement drift: evaluation of efforts to sustain the cost savings from implementing best practice guidelines to reduce unnecessary electrocardiograms (ECGs) during the preadmisison testing evaluation

- Clinical Image

- Emerging treatment of prurigo nodularis with dupilumab

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- General

- Review Article

- COVID-19 scent dog research highlights and synthesis during the pandemic of December 2019−April 2023

- Medical Education

- Original Articles

- Key factors for residency interview selection from the National Resident Matching Program: analysis of residency Program Director surveys, 2016–2020

- Ultrasound-assisted bony landmark palpation in untrained palpators

- Musculoskeletal Medicine and Pain

- Original Article

- Educational intervention promotes injury prevention adherence in club collegiate men’s lacrosse athletes

- Neuromusculoskeletal Medicine (OMT)

- Clinical Practice

- Counterstrain technique for anterior and middle scalene tender point

- Public Health and Primary Care

- Brief Report

- Preventing quality improvement drift: evaluation of efforts to sustain the cost savings from implementing best practice guidelines to reduce unnecessary electrocardiograms (ECGs) during the preadmisison testing evaluation

- Clinical Image

- Emerging treatment of prurigo nodularis with dupilumab