Abstract

This paper analyzes the constraints that Virtual YouTubers (VTubers) encounter during “just chatting” streams on YouTube Live when interacting with viewers who send text messages. We apply quantitative and qualitative methods to investigate how frequently streamers refer to viewers’ messages, the time lag between message receipt and reference, and how streamers cope linguistically with live streaming constraints. The analysis demonstrates that streamers struggle to address all messages, particularly given the occurrence of unavoidable time lags. We also found that streamers use three methods to manage these challenges: “reading messages aloud”, “reading usernames aloud”, and “using adjacency pairs”. Additionally, we noted that in “reading messages aloud” – the most frequently used method – quotative particles and reporting verbs are often omitted, deviating from general modern Japanese grammar. This omission, while similar to phenomena in spoken Japanese, is uniquely influenced by the nature of live streaming and “just chatting” activities.

1 Introduction

Owing to technological advancements in recent decades, computer-mediated communication (CMC) has changed drastically from sharing text only to sharing graphicons (i.e., emojis, emoticons, stickers, etc.), audio, images, and video (Herring 2019). This study examines language use in live streaming, in an attempt to understand new forms of CMC in the Japanese-speaking environment. Specifically, we conduct a basic observation of how streamers known as Virtual YouTubers (VTubers) interact with viewers who send messages via text chat on YouTube Live, a live streaming service facilitated by YouTube.

Live streaming entails the transmission of video files and other media via the Internet in real time without prior recording or storage (Rogers 2023). In Japan, general Internet users began utilizing this method around 2001, with early services (e.g., Netoraji) streaming only audio (Nabeshima 2021). After video sharing became possible, live streaming activities diversified, including “just chatting”, live gameplay (Let’s Play), singing, playing instruments, dancing, cooking, and drawing.

In the late 2000s, Niconico Live was the main platform for Japanese live streaming culture; since the 2010s, however, YouTube Live has taken over this role (Institute for Information and Communications Policy 2024). The characteristics of streamers (YouTubers) using YouTube Live have also diversified over time. Recently, in addition to those streamers who show their faces on camera, others do not show their faces at all, while others still use 2D or 3D avatars. Among these, VTubers are a relatively new type of streamer who use motion capture technology to animate 2D or 3D avatars (Figure 1).

An example of live streaming by a VTuber: VTubers can utilize their voice and movements of the avatar. Viewers can send messages via the text chat on the right-hand side.

While avatar-using streamers have existed since the early 2010s, the term “VTuber” first gained traction after a VTuber called Kizuna AI, who was affiliated with a Japanese company, adopted it in 2016 (Lawrenson 2022). VTubers have since spread rapidly worldwide, largely attracted to the ability to stream without being constrained by the physical attributes of the “person inside” (Lu et al. 2021). As of November 2022, over 20,000 VTubers are reportedly active worldwide (User Local Inc. 2022), representing a wide range of languages and character settings. However, even today, five of the ten VTubers with the most subscribers are primarily active in Japan and speak Japanese (User Local Inc. 2024).

The major forms that VTuber activity may take have evolved since Kizuna AI’s appearance. Until early 2018, many VTubers uploaded pre-recorded videos using 3D avatars in studios. Now, however, most VTubers primarily use 2D avatars for live streaming (Nishino 2022). One major factor driving this change is that viewer watch time is a condition for monetization on YouTube (YouTube n.d.a), and live streaming with 2D avatars, which requires less equipment and preparation, is more conducive to securing sufficient watch time. Such changes have also influenced the stream content, leading to a tendency to revert to relatively long-established content, such as chatting, game play, and singing. In particular, with respect to the most traditional content – that is, “just chatting” streams – VTuber streams have consistently accounted for more than half of the top ten search results for the keyword “Zatsudan haishin” (“just chatting”) on YouTube in the past five years.

Despite the unique history of streaming and VTuber culture in the Japanese-speaking environment, academic research on these phenomena is surprisingly scarce. As one of the few exceptions, Lu et al. (2021), who interviewed Chinese viewers, provides an excellent explanation of VTuber culture in Japan and its diffusion, but detailed explorations of how Japanese-speaking streamers and viewers use language to facilitate interaction remain a desideratum. The present study uses VTubers’ “just chatting” streams as data to understand the reality of language use and argues that new media and contextual environments can give rise to new language forms that are not permitted in traditional Japanese speech.

2 Previous studies on live streaming and the research question of this paper

Prior to the analysis, this section reviews previous studies relevant to this paper and then presents the study’s specific research questions. As noted above, studies focusing on live streaming in the Japanese-speaking environment are scarce. In other language environments, however, research on various live streaming services, such as Twitch, Periscope, and AfreecaTV, has accumulated over the last decade (Choe 2019; Licoppe and Morel 2018; Nematzadeh et al. 2019; Olejniczak 2015; Pires and Simon 2015; Recktenwald 2018; Song and Licoppe 2024; Tang et al. 2016). For example, adopting approaches used in conversation analysis, Licoppe and Morel (2018) observed Periscope streams hosted by French speakers and revealed that a “talking head design”, whereby the streamer’s face is shown in the center of the screen, is established as a visual norm and that the streamer typically refers to all chat messages sent by viewers. Similarly, Song and Licoppe (2024) analyzed streams involving English speakers using the successor service to Periscope and argued that messages in which viewers indicate that they have noticed something within the stream offer a powerful means by which viewers can demonstrate engagement. Meanwhile, Tang et al. (2016) drew on interviews and other methods to study Periscope and suggested that whether interaction between streamers and viewers occurs varies, according to the stream’s purpose and activities.

Previous studies have addressed various streaming activities, and one that is discussed particularly extensively is Let’s Play on Twitch (Nematzadeh et al. 2019; Olejniczak 2015; Pires and Simon 2015; Recktenwald 2018). For example, studies that quantitatively analyzed chat messages sent by viewers during Let’s Play streams (Nematzadeh et al. 2019; Olejniczak 2015) revealed that for streams with many viewers, individual messages tend to be shorter, time intervals between messages are shorter, more repetition of identical content occurs, more use of emoticons is observed, and less conversation takes place between viewers, while the opposite trends are observed when there are fewer viewers. Recktenwald (2018) also conducted primarily qualitative (and partly quantitative) analysis of the relationship between streamer utterances and viewer messages during English Let’s Play streams. As a result, he observed that the most typical streamer utterances are reports of in-game events that do not address a specific recipient or chat message and, similarly, the most typical viewer messages represent simple impressions of the gameplay and other activities, which do not require a response. However, Recktenwald (2018) also found that viewers sometimes send questions about the game, expecting responses, and in such cases, streamers often use a technique called “Topicalizer”, whereby they read the chat message aloud at the beginning of their turn before responding.[1]

Streamers’ technique of reading messages aloud before responding has been reported not only by Recktenwald (2018) but also by Licoppe and Morel (2018) in their analysis of French Periscope streams, in which they refer to it as the “Read Aloud and Respond” (RAR) format. This suggests that the technique may be universal. Recktenwald (2018) discussed several factors contributing to the occurrence of the Topicalizer, including delays caused by technical issues within the Twitch system, delays resulting from engagement in other activities (gameplay), and the imbalance between the number of viewers attempting to initiate interactions with the streamer and the streamer’s capacity to respond to these interactions. Licoppe and Morel (2018) similarly remarked that the complexity of individual viewer usernames on Periscope, which often include symbols and numbers, makes them difficult to read aloud, thus contributing to the RAR format’s occurrence. In any case, it appears that live streamers must indicate explicitly what they are referring to, even more so than in face-to-face conversations or other media environments.

However, the extent to which technical and situational constraints derived from qualitative discussions (Licoppe and Morel 2018; Recktenwald 2018) specifically impact the progression of individual streams and the frequency with which various language usage features supposedly arising from these constraints actually occur have yet to be sufficiently verified. Similarly, compared to interactions on Twitch, which generally assume concurrent engagement in other activities, “just chatting” streams focus primarily on conversation with viewers. As such, it is not self-evident whether analyses from previous studies are applicable to streams that involve different activities. In light of these circumstances, this paper will describe the reality of “just chatting” streams by Japanese-speaking VTubers by addressing the following three research question:

To what extent do streamers refer to viewers’ messages?

What is the specific length of the time lag that occurs between when a message is sent and when the streamer refers to it?

How do streamers cope linguistically with the constraints of live streaming?

The examination based on these questions, while building on previous research, targets language, activities, and streamers not sufficiently described in previous studies. Therefore, we are confident that it will also yield valuable insights for general research on live streaming.

3 Data and method

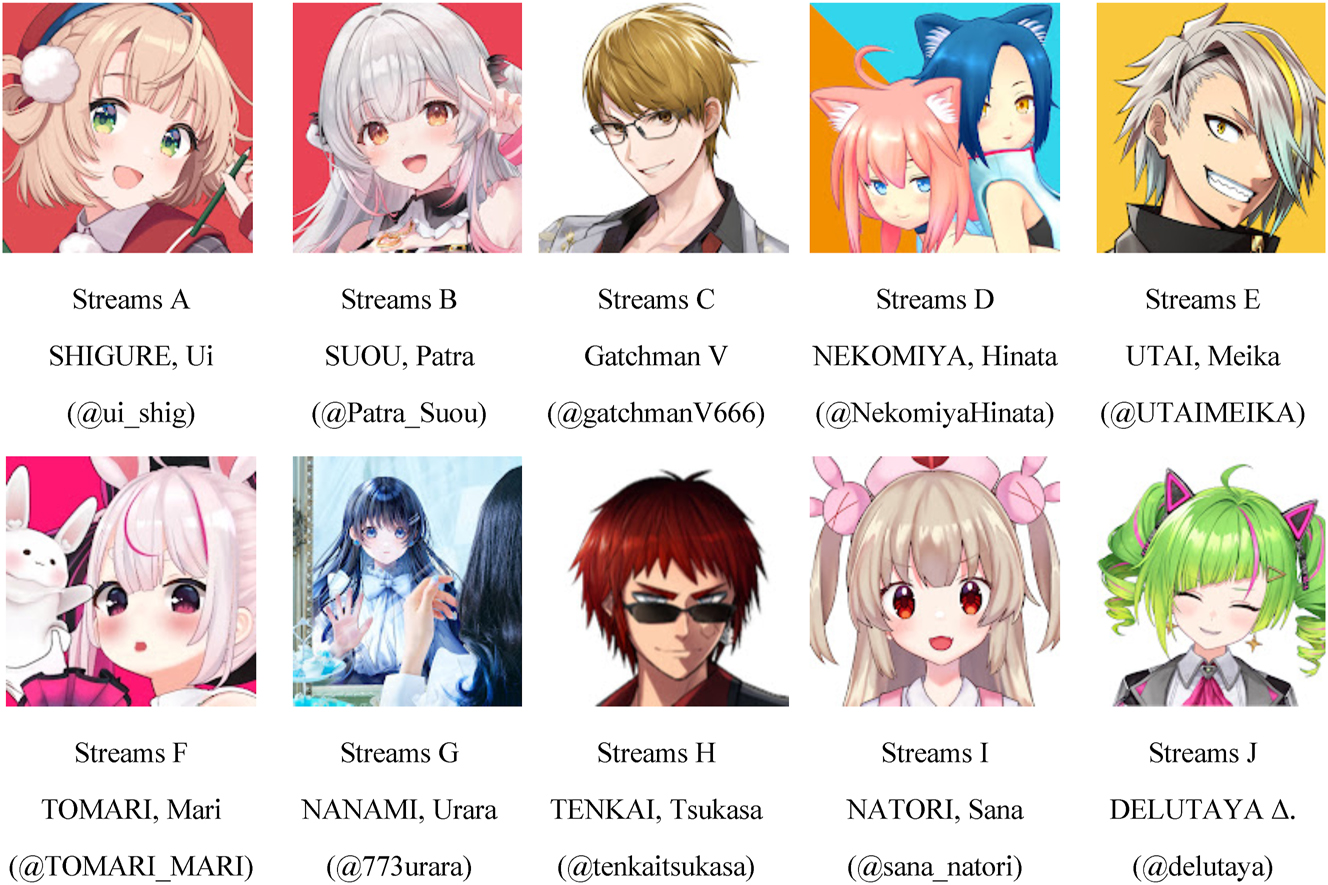

To determine the characteristics of live streaming in the Japanese-speaking environment, we examined the most recent “just chatting” stream archives of the top 10 VTubers in terms of subscriber numbers, who were not affiliated with any specific operating company as of the end of August 2023, who used Japanese, and who had hosted “just chatting” streams within the last year. Table 1 presents the streamers’ names, video titles, streaming dates, URLs, and the number of messages from viewers, along with the stream IDs assigned for analysis. Similarly, Figure 2 compiles the icons (avatar faces) used by each streamer on their YouTube channel. We focused on “just chatting” streams hosted by VTubers because, as explained in Section 1, Japanese live streaming spread from platforms that exclusively allowed audio sharing, making “just chatting” the most traditional activity and, recently, VTubers have become the primary proponents of this activity. Furthermore, we focused specifically on VTubers who were not affiliated with any company. This is because such VTubers constitute the mainstream in terms of the streamer population.[2] Additionally, these VTubers are relatively free from compliance constraints, which are often opaque to researchers, especially regarding interactions with viewers.

“Just chatting” streams analyzed in this study: Stream ID, streamer name, video title, stream date, URL, and message count.

| ID | Streamer name | Video title | Stream date | URL | Message counta |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | SHIGURE, Ui (@ui_shig) |

Mibare no kiki ni chokumen shita onna no zatsudan (A Woman’s Chat Facing the Crisis of Being Doxxed) | May 10, 2023 | https://www.youtube.com/live/gDLVHnuPkAE | 23,170 |

| B | SUOU, Patra (@Patra_Suou) |

[Zatsudan] Hitonatsu no taiken wa watashi o otona ni suru… [Suou Patra] ([Chatting] A Summer Experience Makes Me an Adult… [Suou Patra] ([Chatting] A Summer Experience Makes Me an Adult… [Suou Patra]) [Suou Patra]) |

Aug 27, 2023 | https://www.youtube.com/live/158OCZiYid8 | 10,129 |

| C | Gatchman V (@gatchmanV666) | Hisashiburi no Koukai Zatsudan Waku (A Public Chat Session After a Long Time) | Apr 6, 2023 | https://www.youtube.com/live/bg1WPi9ZILY | 7,346 |

| D | NEKOMIYA, Hinata (@NekomiyaHinata) | [Zatsudan] Konpasu taikyuu haishin otsukaresama kai nado [Nekomiya Hinata] ([Chatting] Post-Compass Endurance Stream Celebration, etc. [Nekomiya Hinata]) | Aug 11, 2023 | https://www.youtube.com/live/NuWC_dUWK64 | 672 |

| E | UTAI, Meika (@UTAIMEIKA) | [Asakatsu Zatsudan] Ohayou (Netenai) [Utai Meika] ([Morning Chat] Good Morning (Didn’t Sleep) [Utai Meika]) | Aug 16, 2023 | https://www.youtube.com/live/PQKqBV6fDVw | 1,777 |

| F | TOMARI, Mari (@TOMARI_MARI) | Ohiru minna de tabeyou ze!!! [#TomaLive] (Let’s Eat Lunch Together!!! [#TomaLive]) | Aug 19, 2023 | https://www.youtube.com/live/EoZWaPYrfs8 | 3,177 |

| G | NANAMI, Urara (@773urara) | [Nanami Urara] #Ponpoko24 shutsuen repo haishin! Natsu no omoide uta zatsudan waku [#UraStream] ([Nanami Urara] #Ponpoko24 Appearance Report Stream! Summer Memories Song Chat [#UraStream]) |

Aug 22, 2023 | https://www.youtube.com/live/nBFOh-DHHuI | 826 |

| H | TENKAI, Tsukasa (@tenkaitsukasa) | [Shuku] Tenkai tsukasa no gouyuu zatsudan – mou itsu buri ka mo oboetenē yo hen [Vtuber] ([Celebration] Tenkai Tsukasa’s Extravagant Chat – I Don’t Even Remember the Last Time Edition [Vtuber]) | Aug 29, 2023 | https://www.youtube.com/live/tRB6VekMZpg | 3,310 |

| I | NATORI, Sana (@sana_natori) | Sana channel natsumatsuri furikaeri ya zatsudan – Oshiri puri ondo mo aru yo -(Sana Channel Summer Festival Review and Chat – There’s Also the Oshiri Puri Dance) | Aug 2, 2023 | https://www.youtube.com/live/nfQjtOO0nN0 | 11,426 |

| J | DELUTAYA Δ. (@delutaya) |

[Zatsudan & Kansoukai] Nihon toukou shita yo Kiite kureta? [Δ.DELUTAYA] ([Chat & Review] I Posted Two Videos Kiite kureta? [Δ.DELUTAYA] ([Chat & Review] I Posted Two Videos Did You Listen? [Δ.DELUTAYA]) Did You Listen? [Δ.DELUTAYA]) |

May 15, 2023 | https://www.youtube.com/live/zFPCBmyx8_c | 2,446 |

-

aMessages sent within the first 60 min of the video (excluding Super Chats, which involve sending money).

Icons (avatar faces) used by the streamers on their YouTube channels. The icons were collected in October 2024 from the homepage of each channel (@xxxx or https://www.youtube.com/@xxxx). In the case of the icon for Stream D, two avatars are depicted; however, this paper focuses on ‘just chatting’ streams conducted solely by the person represented by the avatar on the left (NEKOMIYA, Hinata). It should also be noted that while each avatar may suggest certain age or gender attributes associated with the streamer, the streamers did not necessarily disclose such information publicly.

The data were collected with reference to VSTARTS (https://www.vstats.jp/), a website that compiles VTuber statistics. During this process, streams whose main content clearly differed from “just chatting” activities, such as game play or drawing, were excluded. Additionally, even if the video title included the word “Zatsudan” (“just chatting”), streams that involved only minimal interaction with viewers were not considered “just chatting” streams.

All streams listed in Table 1 adopted a “talking head design” (Licoppe and Morel 2018), whereby the avatar was centered in the video screen. It was observed that these streams are primarily structured through the repeated discourse pattern outlined below:

The streamer speaks about something (→ 2)

Viewers send messages in the text chat system (→ 3 or 3′)

The streamer refers to some of the messages (sometimes using them as a segue to develop or change the topic)

The streamer continues speaking without referring to the messages (sometimes implicitly considering the messages)

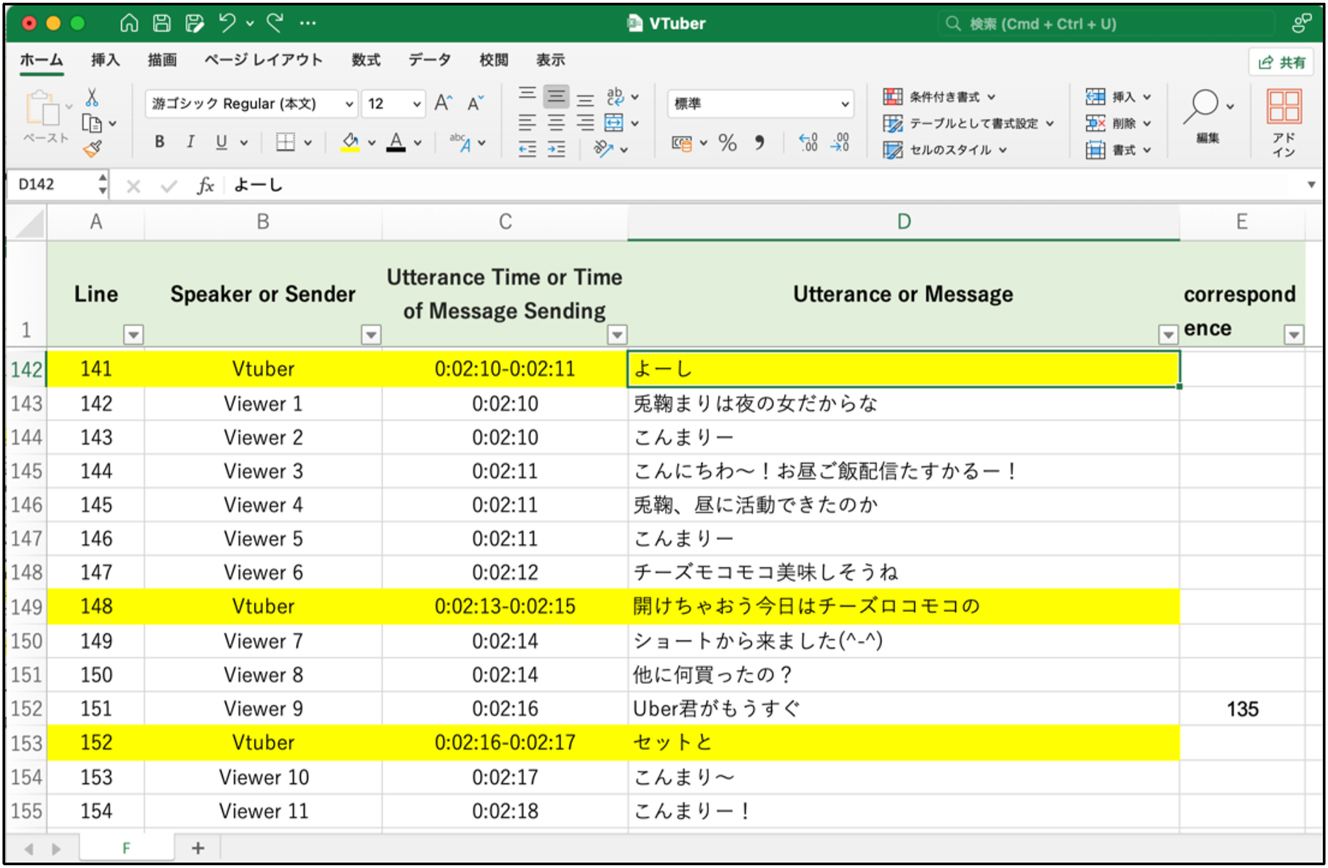

Therefore, we first transcribed the streamer’s utterances during the first 60 min of the video using the automatically generated transcripts provided by YouTube, including timestamps. Second, we organized the transcribed utterances and 64,279 messages sent by viewers within the same 60-minute period in chronological order using Microsoft Excel (Figure 3). Third, we manually examined whether each utterance or message in each row corresponded to any preceding utterance or message and, if so, identified which specific message or utterance it corresponded to. In the third stage, the first and second authors independently conducted the analysis, and only those judgments that matched were considered to constitute “corresponding utterances or messages”. Where multiple identical or highly similar messages were sent within a short period and the streamer referred to one of them, we considered it a reference to three messages for convenience.

Excel sheet displaying VTuber utterances and viewer messages arranged in chronological order.

This paper focused on the development from step 2 to step 3 of the discourse structure mentioned above. We examined specifically when and how the streamer referred to individual messages.

4 Results of the analysis

4.1 To what extent do streamers refer to viewers’ messages?

First, we analyzed the extent to which the streamers in our dataset of “just chatting” streams referred to messages sent by viewers. Previous research includes analyses suggesting that streamers may be expected to read the messages that their viewers send them (Licoppe and Morel 2018) as well as analyses that indicate this is not invariably the case (Recktenwald 2018). In “just chatting” streams, in which interaction between the streamer and viewers is the primary activity, it is expected that large numbers of utterances and messages that are expressly aimed at facilitating interaction will be exchanged. However, an imbalance between the number of such messages and the streamer’s ability to respond to them is also anticipated (Recktenwald 2018). In fact, in Stream A, which had the most messages among the data we observed, 2,769 unique viewers sent messages within the first 60 min of the video. In light of this, we counted the number of messages sent during the streams that the streamers referred to in a manner that allowed us to identify the specific content of the message. Table 2 presents the results of this analysis (“Number of Messages” and “Percentage of total”), along with the number of unique viewers who sent messages during the first 60 min of the video.

Number of messages referred to by the streamers.a

| Stream ID | Number of messages | Total message count | Percentage of total | Number of viewers who sent messages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 100 | 23,170 | 0.4 % | 2,769 |

| B | 187 | 10,129 | 1.8 % | 713 |

| C | 28 | 7,346 | 0.4 % | 744 |

| D | 51 | 672 | 7.6 % | 68 |

| E | 70 | 1,777 | 3.9 % | 229 |

| F | 276 | 3,177 | 8.7 % | 401 |

| G | 70 | 826 | 8.5 % | 99 |

| H | 129 | 3,310 | 3.9 % | 421 |

| I | 87 | 11,426 | 0.8 % | 698 |

| J | 86 | 2,446 | 3.5 % | 413 |

-

aAll data are from the first 60 min of the video, and Super Chats involving monetary contributions were not included as messages.

As Table 2 demonstrates, excluding Super Chats involving monetary contributions, the proportion of messages explicitly referred to by the streamer ranges from 8.7 % (Stream F) to 0.4 % (Stream C), indicating that over 90 % of messages were not specifically addressed by the streamer. Furthermore, 0.4 % of messages were referred to in Stream A, which had the highest total number of messages, while 7.6 % were referred to in Stream D, which had the lowest total number of messages. This indicates that the imbalance between the number of messages and the streamer’s capacity to respond influences the interaction, as found by Recktenwald (2018). However, Stream C, in which the proportion of referred messages was as low as that in Stream A, received only approximately one-third of the total number of messages sent to Stream A. Stream F, which had the highest proportion, received roughly five times the total messages sent to Stream D. This suggests that the frequency with which streamers refer to messages may also vary depending on the streamer’s personality, their relationship with viewers, and the content discussed.

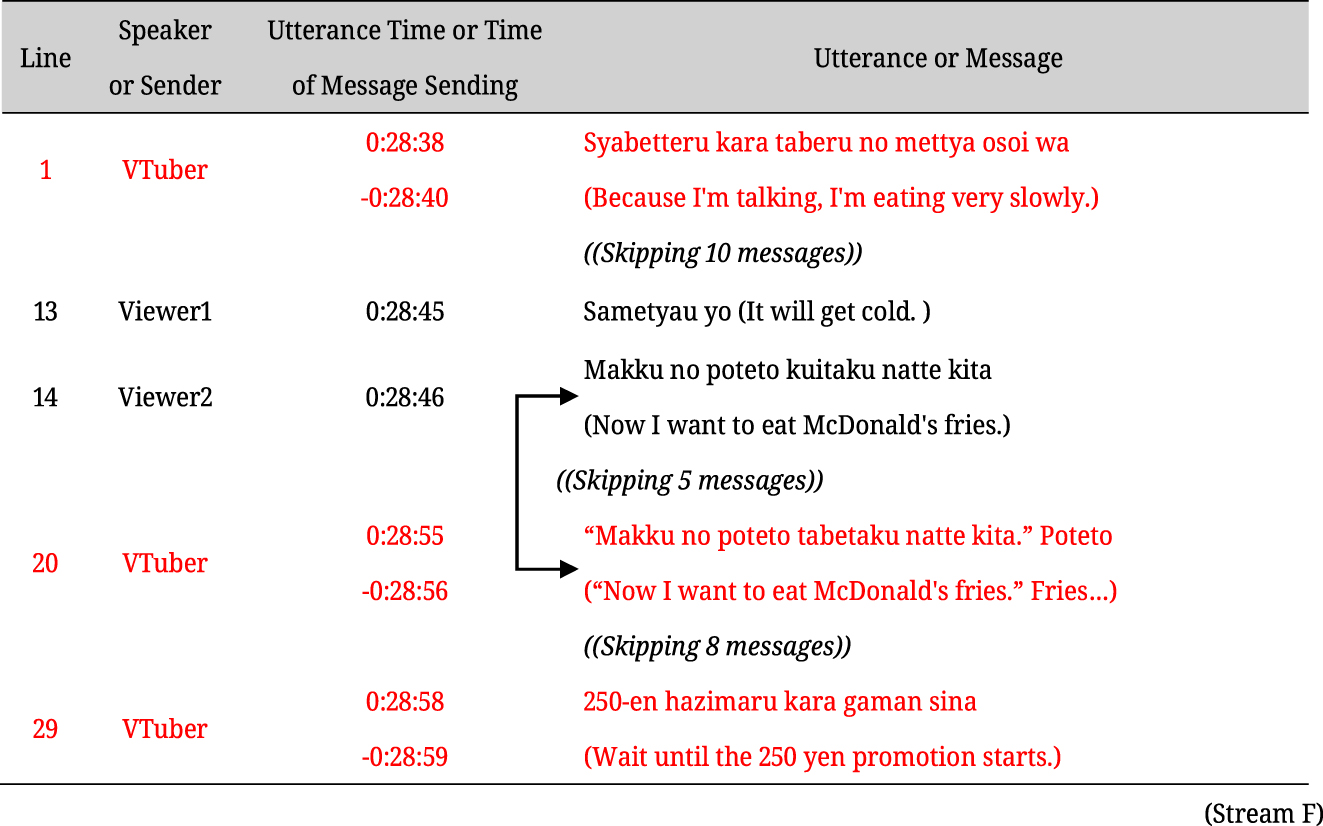

Similarly, as Recktenwald (2018) observed on Twitch, when the streamer referred to messages from viewers, it was often in response to messages requiring an answer. However, there were also instances in our data that did not fit this characteristic, such as in example (1), in which the streamer picked up comments that did not require a response. In example (1), the streamer was eating a McDonald’s hamburger during the stream, and the message from Viewer 2 in line 14 was a simple, unprompted comment (“Now I want to eat McDonald’s fries”). However, the streamer read this message aloud in line 20 and then advised the viewer in line 29 to hold off on buying fries due to an upcoming price drop sale. Thus, while the streamer only refers to a fraction of viewer messages, these references do not invariably conform to a Q&A format. This is likely to be related to the inherently interactive nature of “just chatting” streams, which are aimed at bidirectional communication.

Previous quantitative studies focused on Twitch have reported that the length and diversity of individual messages, the temporal spacing between messages, and the frequency with which conversations take place among viewers change depending on the size of the audience (Nematzadeh et al. 2019; Olejniczak 2015). Given that our focus was on the streamer’s language use, detailed analysis of viewer messages is beyond this paper’s scope, though little conversation took place among the viewers in all the streams.[3]

4.2 What is the specific length of the time lag that occurs between when a message is sent and when the streamer refers to it?

Next, we examine the specific time lag that occurs when streamers refer to messages from viewers. A common characteristic of CMC is that, due to the nature of communication via the internet and electronic devices, it takes longer for others to recognize an utterance or message after it has been sent, as compared to face-to-face conversations (Schoenenberg et al. 2014). This issue also naturally applies to nearly synchronous video-mediated and video-text communication in Japanese-speaking environments. For example, Hosoma and Muraoka (2022) have noted that even slight transmission delays in Zoom can affect the synchronization of actions and turn-taking among participants. Moreover, in live streaming, in addition to the system-induced time lags, delays may occur due to the viewers’ use of text. Similarly, delays often occur on the streamer’s side, as they often need to engage in multiple activities simultaneously, such as interacting with viewers, sharing personal stories, and playing games, depending on the progression of the discourse (Recktenwald 2018).

In YouTube Live, part of the system-induced lag (server-related delay) can be controlled, and streamers must select “normal latency”, “low latency”, or “ultra-low latency” when commencing a stream (YouTube n.d.b). All streams we examined are likely to have been set to “ultra-low latency”, which is estimated to result in an approximate 3-second server processing delay.[4] Meanwhile, based on the analysis in Section 4.1, we extracted the timestamps of each message explicitly referred to by the streamer only when the streamer clearly referred to a single message (i.e., excluding cases where multiple identical or highly similar messages were sent within a short period). We then compared these message timestamps with the start times of the streamer’s corresponding utterances, as extracted from auto-generated subtitles. Based on these comparisons, we calculated the average time span between the sending of a message and the streamer’s response for each “just chatting” stream (Table 3).

Average time from a viewer’s message to the streamer’s reference.

| Stream ID | Time |

|---|---|

| A | 11 s |

| B | 8 s |

| C | 12 s |

| D | 38 s |

| E | 12 s |

| F | 9 s |

| G | 16 s |

| H | 8 s |

| I | 9 s |

| J | 22 s |

As Table 3 suggests, it takes more than twice as long for a streamer in a “just chatting” stream to refer to a viewer’s message after it has been sent, as compared to the system-induced lag in YouTube Live. However, the length of this lag varies across the data. Comparison of Streams A, B, and I, each of which had over 10,000 messages in the first 60 min of the video, with Streams D and G, which each had fewer than 1,000 messages, reveals that more messages result in quicker references by the streamer, while fewer messages result in a longer time before the streamer refers to them.

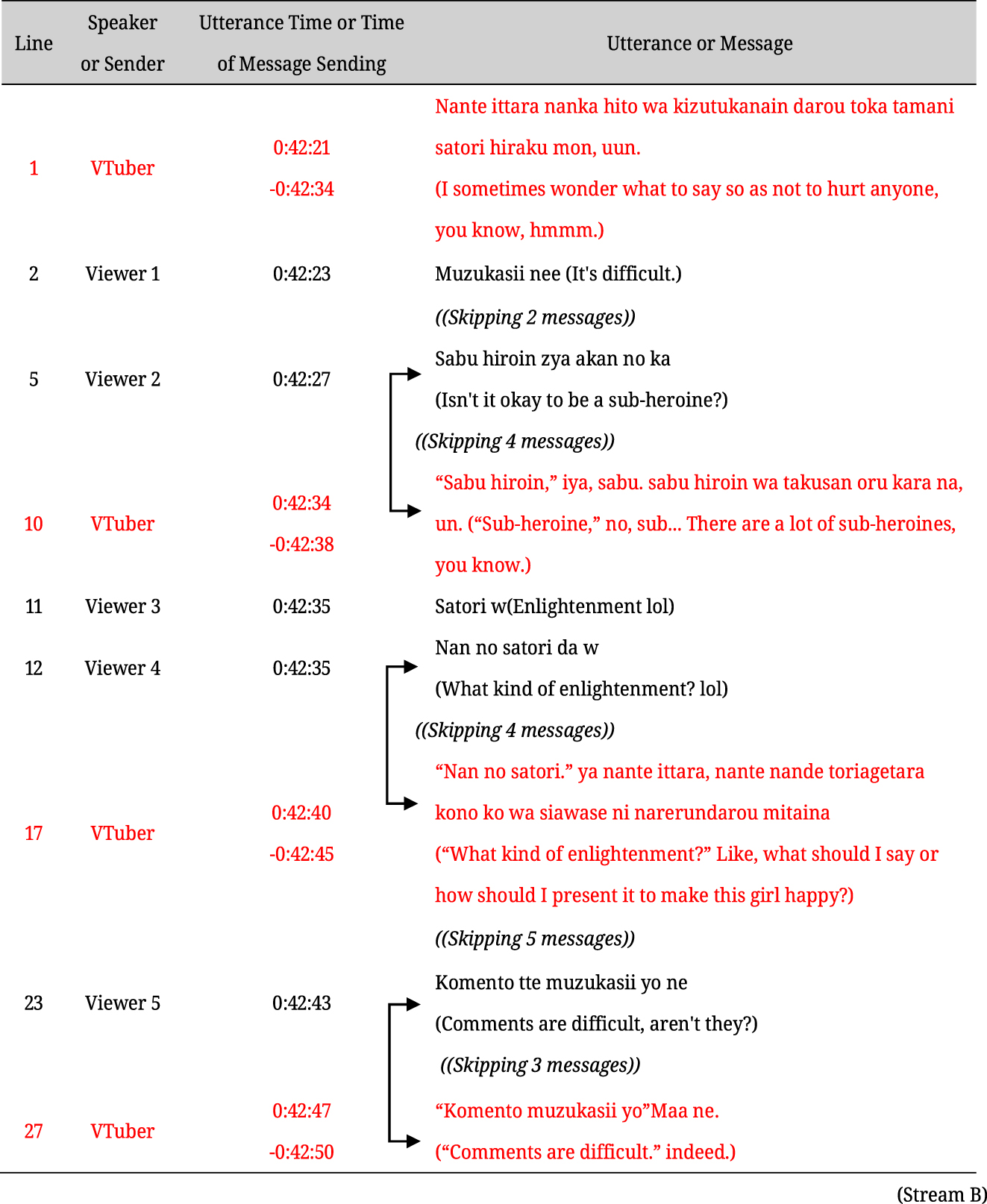

In example (2) from Stream B, for example, the streamer discusses the difficulty of building relationships with heroines in a dating simulation game. Meanwhile, viewers continuously send messages expressing empathy or responding to the streamer’s words. The streamer refers to individual messages within 7 s of their sending time, and these references are observed to be concise – all within 5 s, except for the utterance in line 1. Streams A, B, and I, which have particularly large viewer numbers, all exhibit these characteristics, with frequent and concise references repeated throughout the video.

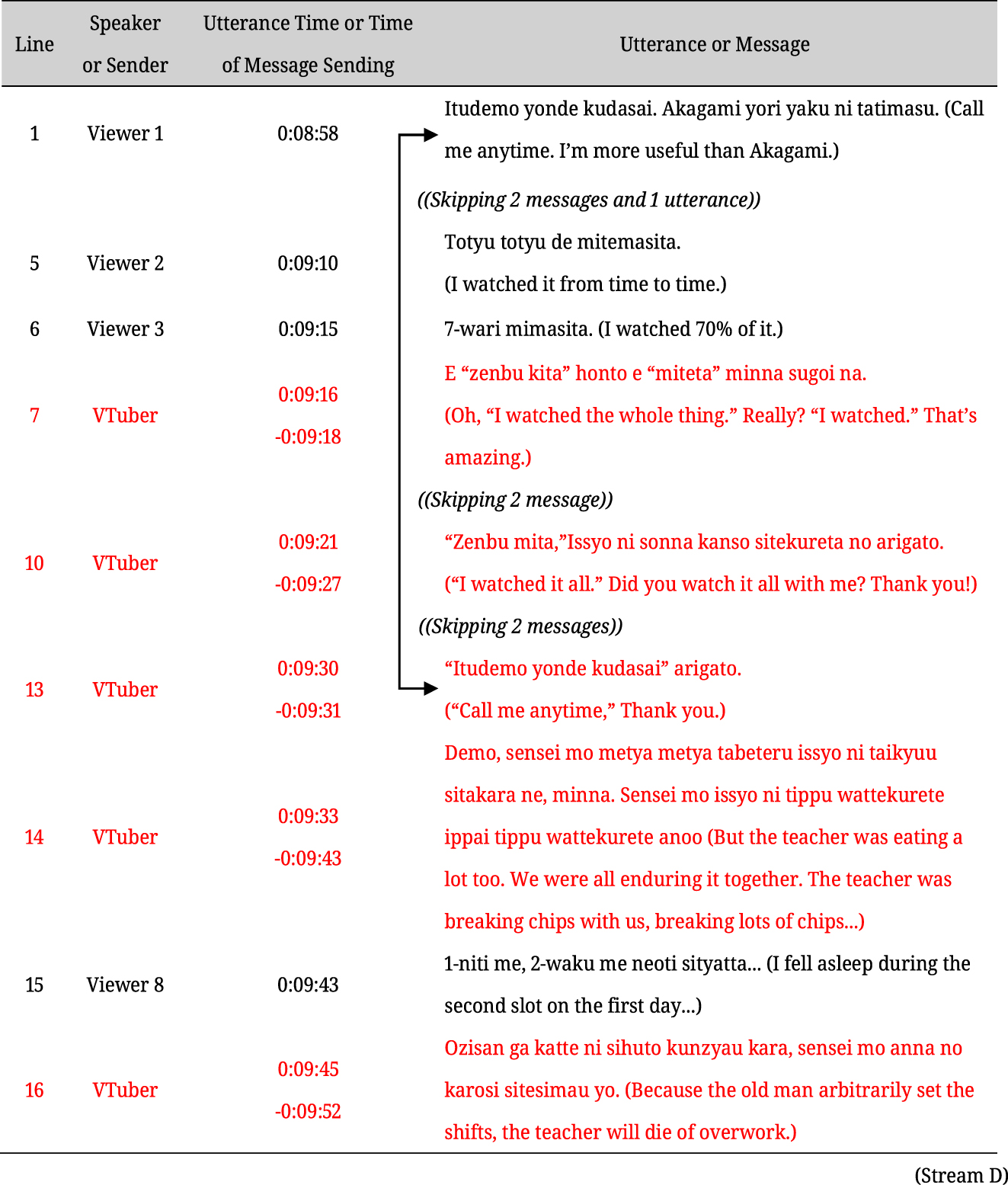

By contrast, in example (3) from Stream D, the streamer reflects on a lengthy Let’s Play stream from several days previously, and individual viewers mention how much of the stream they watched. The interval between messages is always more than 1 s, indicating that the streamer has relatively ample time to check each message. However, 32 s elapse between the time the message in line 1 is sent to the time it is referred to in line 13, indicating that the references are not prompt. Additionally, the utterances following line 13 are not limited to concise responses, given that the streamer uses the conjunction “Demo” (but) to extend the utterance into a reflective speech that continues for 22 s until line 16.

As this contrast reveals, the streamer adjusts the amount of time dedicated to a single topic or individual viewer based on the flow of messages.

4.3 How do streamers linguistically cope with the constraints of live streaming?

Finally, we analyze the linguistic methods that streamers use to interact smoothly with viewers while live streaming. As noted earlier, it is difficult for streamers to refer to all viewer messages and, even if they can, a certain time lag is unavoidable. Therefore, to overcome these constraints, our data identified three methods that streamers appear to use: “reading messages aloud”, “reading usernames aloud”, and “using adjacency pairs”.[5]

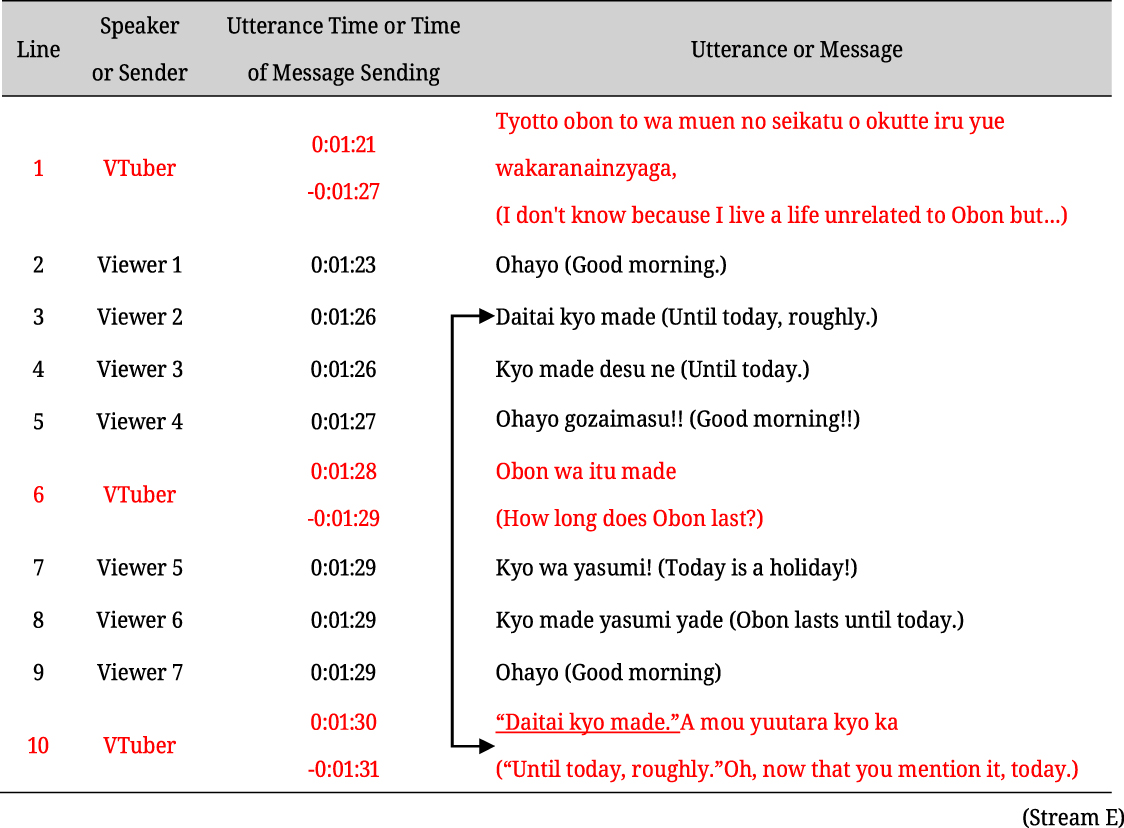

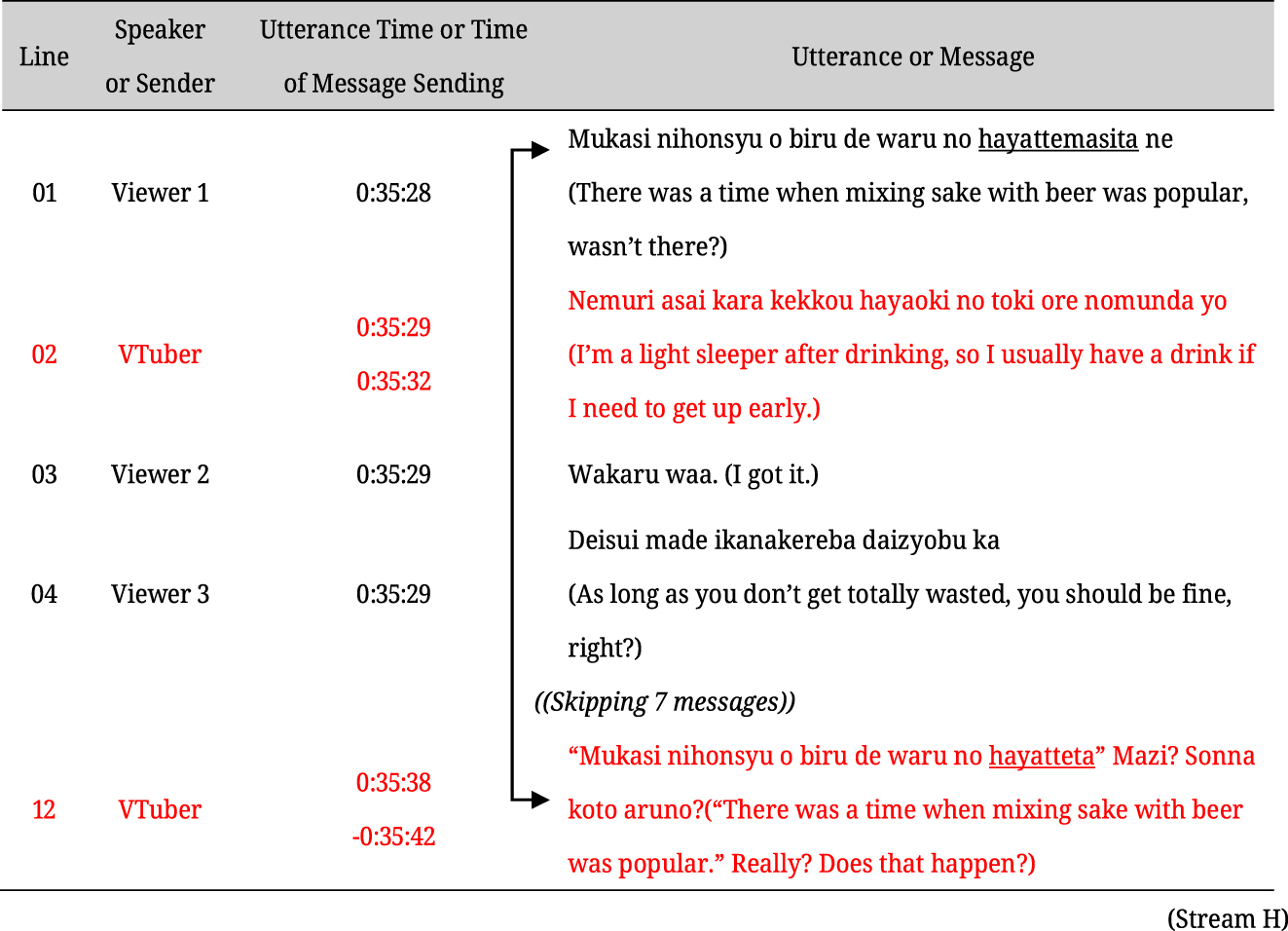

Of these methods, “reading messages aloud” is similar – or identical – to the Topicalizer technique that Recktenwald (2018) reported based on observations of English-language live streams and the RAR format reported by Licoppe and Morel (2018) based on observations of French live streaming activities. For example, in lines 1 and 6 of (4), the streamer asks about the duration of the Obon holiday, a unique Japanese holiday. Meanwhile, during the streamer’s utterance, viewers sent their responses to the question. The streamer subsequently read aloud one of these responses from Viewer 2 (line 3) and declared at line 10 that the question was resolved.

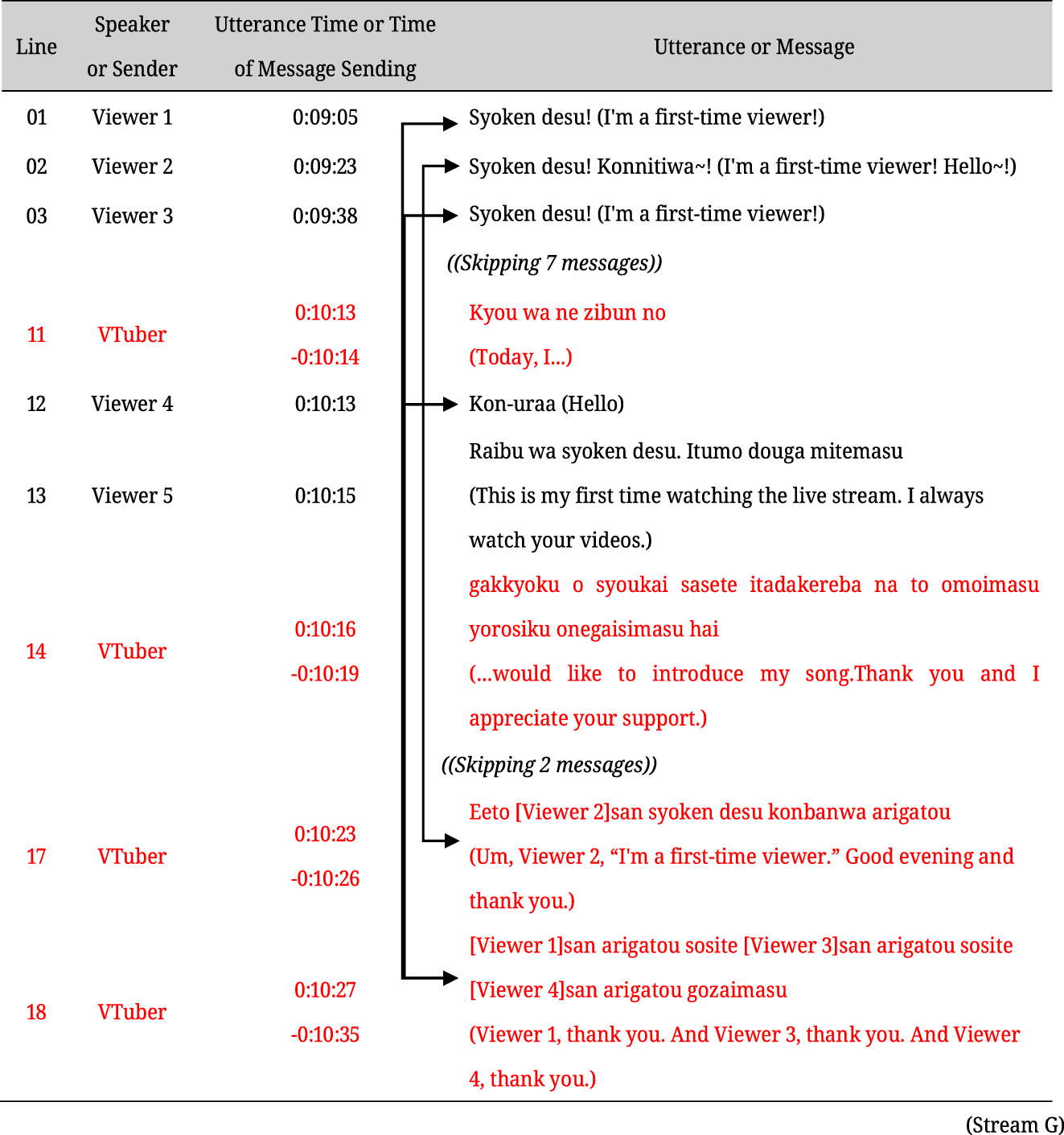

Similarly, “reading usernames aloud” entails the streamer reading the usernames of those who sent messages (strictly speaking, their YouTube channel names). In (5), the streamer explains the day’s content in lines 11 and 14 and the preceding utterances. Meanwhile, viewers send messages reporting that it is their first time watching the live stream (lines 01, 02, 03, and 13) or simply greeting the streamer (line 12). Based on these messages, the streamer reads the usernames aloud in lines 17 and 18 and expresses gratitude.[6]

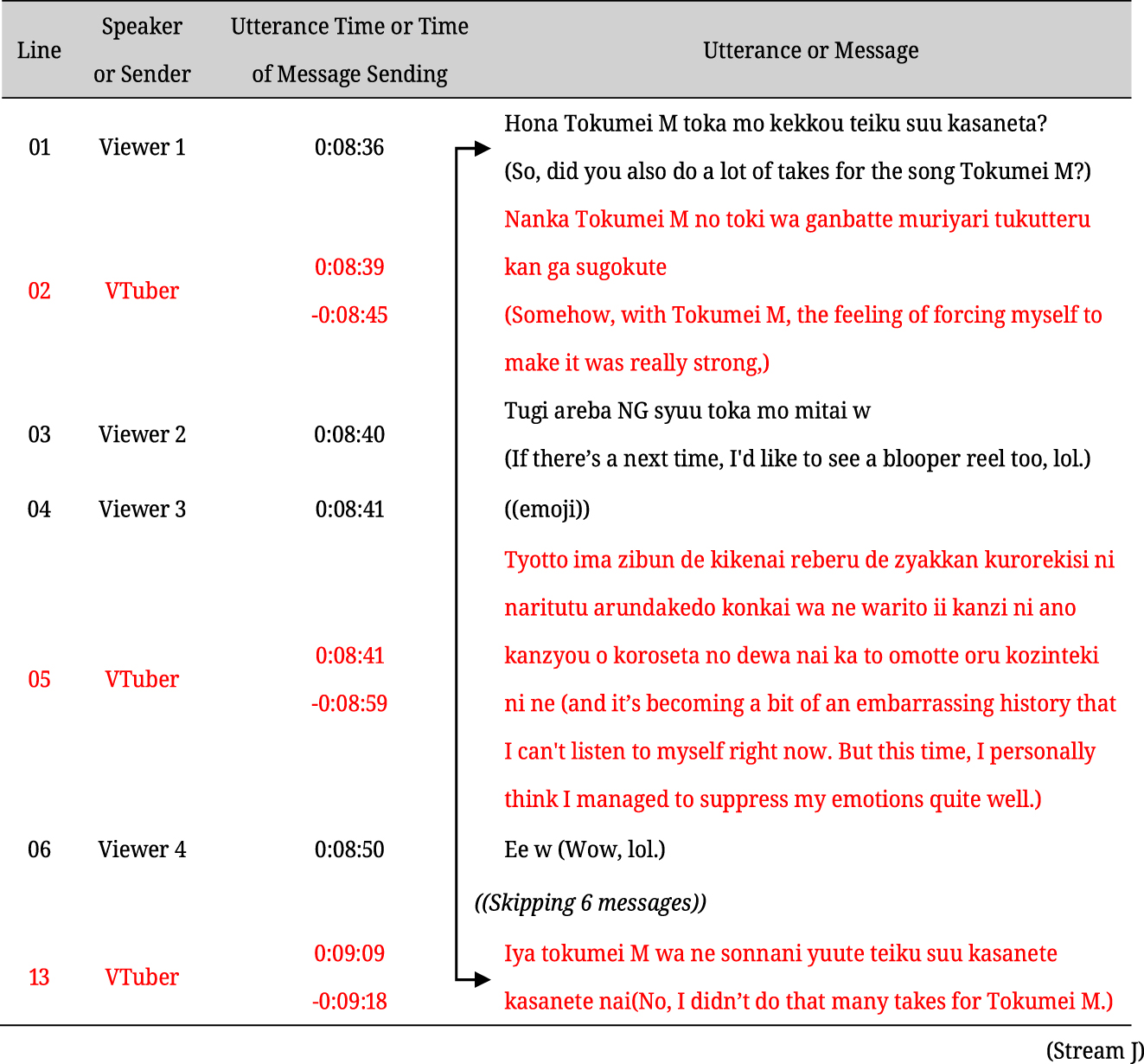

Furthermore, “using adjacency pairs” involves the streamer making utterances that are designed as the second part of adjacency pairs (Schegloff and Sacks 1973), such as an “answer” to a “question”. In (6), the streamer gives her impressions of the latest song she has covered, comparing it to a previously covered song, “Tokumei M”, in lines 02 and 05. After this segment, the streamer responds in line 13 to a viewer’s question in line 01 (“So, did you also do a lot of takes for the song Tokumei M?”). The streamer’s utterance in line 13 begins with the negative response “Iya” (“No”), indicating that it is the second part of an adjacency pair, with the first part found in the preceding message.

It should be noted that these three methods are not mutually exclusive within a single utterance. For example, the utterance in line 17 of (5) (“Um, Viewer 2,” “I’m a first-time viewer.” “Good evening and thank you.”) has characteristics of both “reading usernames aloud” and “reading messages aloud”. Similarly, just as Recktenwald (2018) presents the Topicalizer as a method for referencing messages that “request a response”, utterances that fulfill the category of “reading messages aloud” are also often the second part of an adjacency pair.[7]

However, “Reading messages aloud” is clearly the most frequently used of the three methods. Even counting only those instances in which not only a single noun or noun phrase but also entire clauses or sentences were read aloud, it was observed that in all but one stream, more than half of the references fell into the “reading messages aloud” category, as Table 4 demonstrates.

References corresponding to “reading messages aloud” excluding single nouns or noun phrases.

| Stream ID | “Reading messages aloud” | Percentage of total references |

|---|---|---|

| A | 71 | 71.0 % |

| B | 141 | 75.4 % |

| C | 2 | 7.1 % |

| D | 26 | 51.0 % |

| E | 50 | 71.4 % |

| F | 199 | 72.1 % |

| G | 52 | 74.3 % |

| H | 82 | 63.6 % |

| I | 57 | 65.5 % |

| J | 65 | 75.6 % |

On the other hand, instances in which “reading usernames aloud” or “using adjacency pairs” occurred independently, as seen in (5) and (6), were relatively rare, with fewer than 10 examples in most streams.[8] Therefore, “reading messages aloud” may also be acknowledged as a commonly used technique in live streaming in the Japanese environment.

Moreover, from a grammar research perspective, an interesting point is that, despite some ambiguities attributable to listening comprehension issues, more than 90 % of instances of “reading messages aloud” omitted quotative particles, such as “tte”, and reporting verbs, such as “iu” (to say). In modern Japanese, quotative particles and reporting verbs are generally difficult to omit, with few exceptions. Therefore, the omission of these elements in live streaming may be regarded as a rare example in which the characteristics of the medium and the situational context interfere with the grammar itself. The next section will discuss this peculiarity in detail.

5 Zero-marked quotative in “just chatting” streams

In Section 4, we analyzed the constraints faced by streamers in communication with viewers, using “just chatting” streams hosted by 10 VTubers as case studies. We also observed three methods used to address these constraints. This section examines the linguistic peculiarity of the most commonly used method, “reading messages aloud”, and discusses the background that gives rise to such peculiarity in live streaming.

5.1 “Reading messages aloud” as a quotative expression

As observed in 4.3, “reading messages aloud” is used in a way that is embedded within the streamer’s own speech (Licoppe and Morel 2018). Therefore, before proceeding with the discussion, we first clarified whether the viewer’s message, as expressed via this method, should be regarded as a quotation or merely as a form of “reading aloud”. In modern Japanese, the most typical approach to indicating quotations is to use the quotative particles “to” or “tte” (or their equivalents “toka” and “nante”) and a reporting verb, as shown in (7) (Fujita 2000; Kato 2010; Sunakawa 2003). In spoken language, one of these two elements may be omitted, but it is uncommon for both to be dropped.[9]

| Minna10 | ga | “sugoi | ne” | { to / tte / | toka / nante } | itteru. |

| Everybody | nom | Awesome | fp | qp | say-pfv | |

| ‘Everyone is saying “That’s amazing!”’ | ||||||

- 10

Abbreviations used are as follows: ACC (Accusative), COP (Copula), DAT (Dative), FP (Final Particle), GEN (Genitive), HO (Honorific), INT (Interjection), NEG (Negative), NOM (Nominative), PASS (Passive), PFV (Perfective), POL (Politeness), PROG (Progressive), QP (Quotative Particle or its equivalent form), and TOP (Topic).

On the other hand, when it comes to simply reading aloud, neither the quotative particle nor the reporting verb are necessarily required, as seen in (8).

| (Saying tongue twisters while looking at the characters) | ||||||||

| Ee | “Tonari | no | kyaku | wa | yoku | kaki | kuu kyaku | da” __. |

| int | next | gen | customer | top | many | persimmon | eat customer | cop |

| ‘Well, “The customer next to me eats a lot of persimmons.”’ | ||||||||

Thus, the peculiarity of omitting quotative particles and reporting verbs while “reading messages aloud” could be identified only when this method was a form of quotation.

Concerning this issue, we considered “reading messages aloud” during live streaming to fulfill the characteristics of a quotation (albeit not entirely) for two reasons. The first reason was that, in the cases we observed, “reading messages aloud” did not merely involve reading messages verbatim but sometimes involved slight modifications to the message form. For example, in (9), a viewer sends a message in the polite form (-hayattemasita) in line 01. However, when the streamer reads it aloud in line 12, the sentence-ending form has been altered to the plain form (-hayatteta).

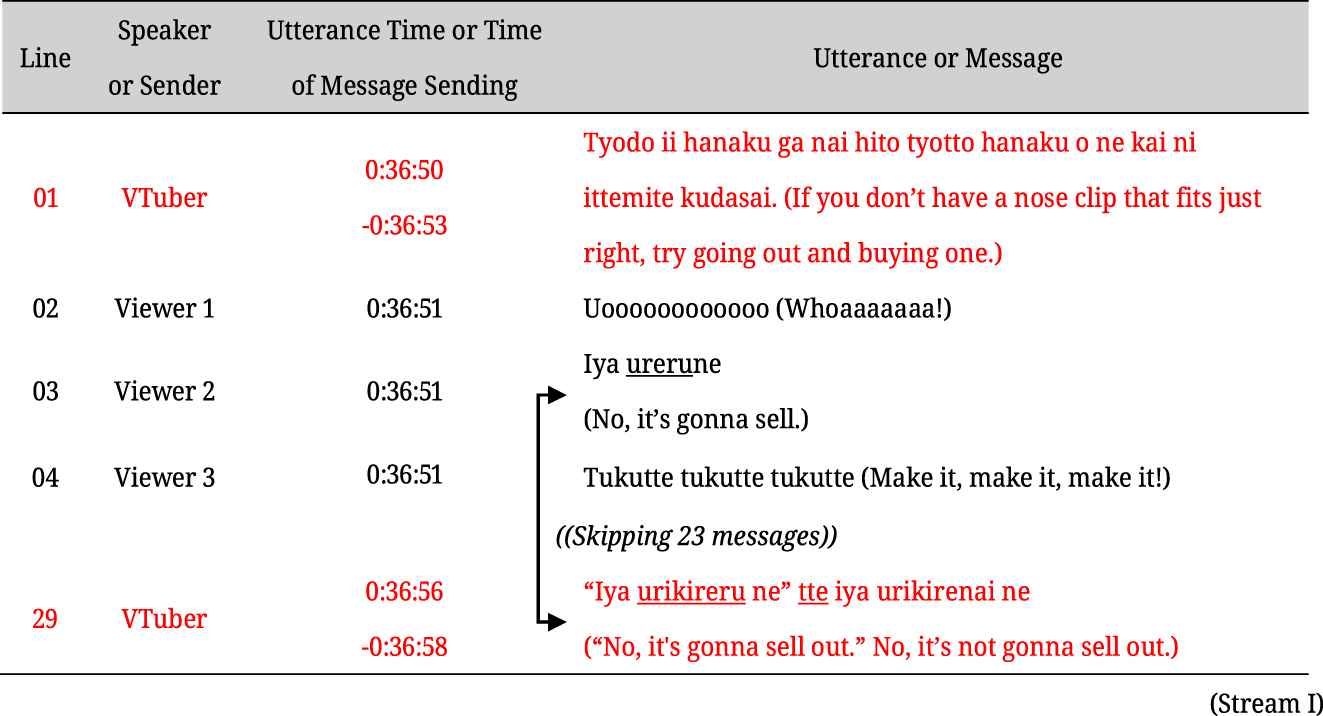

The second reason is that, as reported in 4.3, although more than 90 % of the cases observed in “just chatting” streams omitted quotative particles and reporting verbs, a few instances did involve quotative particles. For example, in (10), where the streamer jokingly recommends an unnecessary item (a clip for the nose) to the viewer, the streamer refers to the viewer’s message from line 01 in line 12. In this instance, the act of “reading messages aloud” in line 12 involves a similar modification in form (changing “ureru” (sell) to “urikireru” (sell out)) as seen in (9), as well as the use of the quotative particle “tte” at the end.

According to Fujita (2000), three conditions (A), (B), and (C) are necessary for a typical syntactic quotation, made explicit through grammatical forms in Japanese, to be established:

Intentionality of expression or stance in expression (i.e., something meant to “reproduce”)

Characteristics as a linguistic entity (sign) (i.e., used as “something like that”)

Characteristics as a syntactic unit (i.e., based on B), (the linguistic entity functions as a cohesive unit and serves as a constituent of the sentence).

(Fujita 2000: 10)

Of these, (A) points to the essence of “quotation” as an act of “reproduction”, based on identity. However, the determination of such identity depends on the speaker’s interpretation and, thus, the quotation and the quoted text may involve modifications to the extent that facts remain unchanged. Additionally, (B) indicates that the quoted speech should be recognizable as “quoted speech” and thus be distinguishable from the “narrative part”. Furthermore, (C) suggests that a “syntactic quotation” is typically embedded in the sentence by a quotative particle.[11]

Based on Fujita (2000), the alterations in linguistic form observed in (9) and (10) suggest that the act of “reading messages aloud” in these instances reflects the speaker’s interpretation as they reproduce the content. Additionally, in (9), the rate of speech, prosody, and pauses distinguish the act of “reading messages aloud” from the streamer’s own speech (thus distinguishing between “quoted speech” and the “narrative part”). Similarly, in (10), with the use of the quotative particle “tte”, all of the conditions outlined by Fujita (2000) are met. These observations indicate that live streaming can function as a venue where “reading messages aloud” may be performed not merely as “reading aloud” but as “quotation”. Therefore, the lack of quotative particles and reporting verbs can in many cases, as in (9), indeed be considered an unusual phenomenon in the grammatical structure of Japanese.

5.2 Differences in relation to existing expressions

Incidentally, previous studies on spoken Japanese have also pointed out that, even in cases clearly recognized as quotations, there is a possibility that quotative particles and reporting verbs may not appear in certain contexts or discourse genres.[12] For example, (11) is an utterance in a casual conversation among university students discussing an incident in which their mutual acquaintance, M, inquired about another acquaintance, A. In this utterance, the first two sentences in quotation marks use the particle “toka” and the reporting verb “iu,” but the third sentence omits these elements. Sunakawa (2003) notes that such omissions are possible when a story is being reenacted within a conversation and the speakers act as characters.

| “A | nanka | kakusiterunda | yonee” | toka | ittete, | |

| A (person’s name) | something | hide-prog-nom-cop | fp | qp | say-pfv | |

| “nanka | aru | yonee” | toka | itte, | “yaa | betuni |

| something | exist | fp | qp | say | no | particularly |

| nanmo | nainzya | nai desu | kanee?” | __ Atasi | ||

| anything | nothing-nom-cop | not cop | fp | I | ||

| dokkidoki | sitee. | |||||

| nervous | do | |||||

| ‘She said, “A is hiding something,” and also, “There must be something,” to which |

||||||

| (Sunakawa 2003: 152) | ||||||

It is noteworthy that, in English conversation also, introductory clauses such as “He said” may be omitted when participants reenact reported speech (Holt 2007). Holt (2007) observes that such omissions predominantly occur in jokes and are established in three cases: when the introductory clause has already been used in preceding utterances, when prosodic or vocal quality changes accompany the quoted speech, and when the quoted speech includes dialect or offensive language, clearly indicating that it is not the speaker’s own words. In general, when indicating direct speech, English explicitly prefaces quotations with an introductory clause with a subject and a reporting verb before the speech, as shown in (12). In contrast, as shown in 5.1, Japanese explicitly indicates quotations by placing a particle and a reporting verb after the speech. Thus, although the positioning of linguistic markers for quotations differs between the two languages, Holt’s (2007) observations may still be applicable to Japanese to some extent, as illustrated by (11), in which the first two quotations do not omit linguistic markers.

| He said, “There’s a fly over there!” |

Another exception in spoken Japanese is that of political speeches. For instance, in the speech in (13), the words of another person regarding Japan’s national defense are quoted without the use of quotative particles or reporting verbs.

| “Nihon | no | anzen | wa | dai | nana | kantai | dake | de | ee,” | ___ |

| Japan | gen | safety | top | The | Seventh | Fleet | only | cop | okay | |

| Konna | Netoboketa | koto | o | iu | Minsyutou | ni | minasamagata | |||

| such | absurd | thing | acc | say | Democratic Party | dat | you | |||

| no | inoti | ya | zaisan | o | azukeru | koto | wa | dekimasu | ka? | |

| gen | life | and | property | acc | entrust | that | top | possible | fp | |

| ‘“The Seventh Fleet is enough to protect Japan’s safety.” Can you entrust your lives and property to a Democratic Party that says such absurd things?’ | ||||||||||

| (Okubo 2013: 133) | ||||||||||

Okubo (2013) refers to such expressions in political speeches as “Zero-gata inyo hyogen” (Zero-marked quotative) and asserts that they are used to evaluate the words of others who are not present or to draw the audience into the narrative world by vividly depicting the conversation.

The omission of quotative particles and reporting verbs in dialogues and monologues noted in previous studies shares similarities and differences with the omission of these elements in “reading messages aloud” during live streaming. One similarity, as pointed out by Holt (2007), is that transitioning from reading a message (quotation) to the VTuber’s own speech often involves changes in prosody and voice quality. For example, in the utterance from (4) discussed in Section 4.3 (excerpted in (4)′), the quoted part was spoken more slowly than the subsequent part (i.e., the streamer’s own speech).

| “Daitai | kyo | made.” | __ | A | mou | yuutara | kyo | ka |

| roughly | today | until | oh | already | say-if | today | fp | |

| ‘“Until today, roughly,” Oh, now that you mention it, today.’ | (Stream E) | |||||||

Similarly, the streamer’s “reading messages aloud” invariably serves the purpose of expressing their own response to the message, akin to politicians’ quotation of others’ words in speeches, to express their own evaluations (Okubo 2013).

Meanwhile, differences include the frequency of occurrence and the origin of the quoted speech. In face-to-face or telephone conversations, the omission of linguistic forms indicating quotations is possible only in very limited contexts, and the majority of quotations are explicitly marked. By contrast, in VTuber streams, as mentioned above, despite some ambiguous cases due to changes in prosody or voice quality, at least 90 % of instances omit both quotative particles and reporting verbs.

Similarly, the omission of linguistic forms in previous studies occurs when the speaker is quoting the words of someone not present (including past or future selves) or when reenacting a different conversation. By contrast, in live streaming, the messages read aloud are the words of viewers currently participating in the stream, and the conversation is happening in the here and now. Thus, at least within the scope of actual spoken utterances, the omission of quotative particles and reporting verbs in “reading messages aloud” possesses a uniqueness not observed in other discourse environments.

5.3 Similarities with existing expressions

The simplest explanation for the omission of quotative particles and reporting verbs in live streaming is that, due to the high frequency of “reading messages aloud”, streamers may avoid repeatedly uttering redundant elements. However, in Japanese radio broadcasts, which also feature a few broadcasters with many listeners and lack shared spatial presence, even when emails or letters from listeners are frequently read aloud, it is observed, as in (14), that the sender is always identified at the beginning of the utterance and, in many cases, quotative particles and reporting verbs are appended at the end. Therefore, it is suggested that the peculiarity of language use in live streaming cannot be explained merely by the act of “reading messages aloud” itself or its high frequency.

| Aiti-ken, | Nou | aru | taka | wa | tie | o | dasu | san |

| Aiti-prefecture | Nou | aru | taka | wa | tie | o | dasu (Radio name) | ho |

| kara. | ||||||||

| from |

| “Akiramezu | ni | yarituzuketeiru | koto | to | ieba, | razio | bangumi | e |

| give up-neg | dat | continue-prog | thing | qp | say | radio | program | to |

| no | toukou | desu. | ||||||

| gen | submit | cop | ||||||

| Zimoto | no | Aiti | no | razio | kyoku | wa | motiron | Nippon |

| local | gen | Aiti | gen | radio | station | top | naturally | Nippon |

| Housou | no | bangumi | ni | |||||

| Broadcasting | gen | program | dat |

| mo | yoku | toukou | simasu. | Demo | iwayuru | hagaki | syokunin | no |

| also | often | submit | do | but | so-called | postcard | craftsman | gen |

| youni | omosiroku | |||||||

| like | entertainingly |

| kakenai | node, | syougai | daritu | wa | itiwari | gobu | kurai | desu. |

| write-neg | so | lifetime | batting | average | top | 15 percent | about | cop |

| Demo | yomareta | |||||||

| but | read-pass |

| toki | no | kaikan | ga | wasurerarezu, | akiramezu | tuzukete | imasu” | to iu |

| time | gen | pleasure | nom | unforgettable | give up-neg | do | qp | saything |

| koto | desu. | |||||||

| continue | cop | |||||||

| ‘From Mr. Nou aru taka wa chie o dasu in Aichi Prefecture. “The thing I have been persistently doing without giving up is sending contributions to radio programs. I often contribute not only to local Aichi radio stations but also to programs on Nippon Broadcasting System. However, since I can’t write as entertainingly as “postcard craftsmen”, my lifetime batting average is about 15%. Still, I cannot forget the pleasure of being read, so I continue without giving up.”’ | ||||||||

| (“Sandwichman: The Radio Show Saturday” on Nippon Broadcasting System, June 1, 2024.) | ||||||||

Meanwhile, if we shift our perspective and consider that the omission of linguistic forms is driven by more active motivations rather than redundancy, we may obtain a more appropriate explanation. Specifically, although this may seem contrary to the discussion in Section 5.1, we propose that zero-marked quotatives in live streaming still possess an expressive effect of recreating some form of dialogue, similar to analogous utterances observed in face-to-face and telephone conversations (Holt 2007; Sunakawa 2003). Furthermore, we suggest that such an expressive effect is necessitated by both technical and situational issues.

The technical issue, as clarified in Section 4.2, is that live streaming, despite being labeled “live”, is never a truly synchronous CMC mode. This applies not only between the streamer and viewers but also among viewers themselves. The streamer and viewers do not share the same time-space, and there can be no guarantee that they are watching the same video (some viewers might have the browser completely in the background, listening only to the audio). Therefore, the streamer is constantly obliged to clarify what they are referencing.

Similarly, the situational issue is that in “just chatting” streams, the streamer is literally required to chat with viewers. As mentioned, although live streaming is not fully synchronous, participants are not entirely free to act asynchronously. In particular, the streamer, as the only one who can speak audibly, must talk continuously to sustain the viewers’ interest. In Japanese face-to-face or telephone conversations, feedback from the receiver guides the progression of the conversation (Horiguchi 1997). However, in live streaming, such feedback typically arrives with a slight delay. Therefore, without any measures, the streamer’s discourse is persistently at risk of becoming a monologue.

Given these two issues, the omission of quotative particles and reporting verbs may be recognized as a highly effective method for clarifying what is being referenced and restoring a conversational feel. Streamers can introduce viewers’ messages without converting them into their own words, such as using the phrase “to itteru” (“the viewer is saying”), and immediately follow up with responses to those words, overcoming the temporal and spatial gaps between the streamer and viewers, and effectively “recreating dialogue”.

Furthermore, the relationship between the technical and situational issues in “just chatting” streams and language use also explains why the other methods observed in Section 4 are less favorable than “reading messages aloud”. “Reading usernames aloud” and using “adjacency pairs” merely communicate the intention to the specific user who sent the message while being unfriendly to the many viewers who usually do not continuously monitor the chat section. Moreover, “reading usernames aloud”, in particular, can single out one viewer from among many, which may risk antagonizing other viewers, particularly where popular VTubers are concerned. Therefore, the method of reading messages aloud without mentioning usernames and continuing the streamer’s own speech may be regarded as a highly sophisticated practice.

In summary, the zero-marked quotative occurring in “reading messages aloud” shares expressive effects with other zero-marked quotatives observed in different contexts, in terms of “recreating dialogue”. However, the motivations for utilizing such effects clearly possess unique aspects closely tied to the characteristics of live streaming and the interpersonal communication that takes place therein. Additionally, the fact that zero-marked quotatives observed in live streaming differ from similar, previously identified elliptical expressions, and functioning as a format that indicates conversations happening here and now, suggests that new media and situational contexts can generate new linguistic forms that were not previously permissible in traditional Japanese.

6 Conclusions

This paper has analyzed the constraints that arise when streamers on YouTube Live interact with viewers who send text messages, focusing on “just chatting” streams hosted by VTubers. The analysis revealed that it is difficult for streamers to address all messages received and that a time lag is inevitable. However, three methods used by streamers to overcome these challenges were identified: “reading messages aloud”, “reading usernames aloud”, and “using adjacency pairs”. Moreover, we remarked that the frequently used method of “reading messages aloud” often involves the omission of quotative particles and reporting verbs, which typically do not occur in general modern Japanese, and discussed the peculiarity of this phenomenon. Specifically, it was argued that, while such omissions share expressive effects with exceptional phenomena in spoken Japanese noted in previous studies, the motivations for these effects are unique to the nature of live streaming and “just chatting” activities.

Our finding that new media and contextual environments are generating linguistic forms previously not permitted may reignite the early-2000s debate as to whether CMC changes language, which was frequently discussed when computers and mobile phones were newly introduced. For instance, Thurlow and Brown (2003) argued, based on their analysis of text messaging, that the unique language use observed therein remains an extension of existing language practices. However, with the increased diversity in CMC forms today, it is worth reconsidering the extent to which unique language use in different media environments may be explained as extensions of existing practices or as manifesting the existence of genuinely new forms. Live streaming, in particular, where streamers and viewers use different modalities, offers a compelling field for exploring how modalities and temporal–spatial contexts shape language use and linguistic behavior.

Future research should include further analysis of viewers’ language use and differences in streamers’ behavior depending on viewer numbers. Similarly, it is desirable to focus on streamers other than VTubers and activities other than “just chatting”. Continued exploration of the characteristics of linguistic communication in live streaming is necessary.

Acknowledgments

This paper was based on an oral presentation delivered at the 48th Meeting of the Japanese Association of Sociolinguistic Sciences (March 9, 2024). In the course of preparing this paper, several numerical errors were corrected. The research for this paper was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 22K19998.

References

Asahi, Yoshiyuki. 2008. Nyūtaun Kotoba no Keisei-katei ni Kansuru Shakaigengogakuteki Kenkyū [A sociolinguistic study on the process of the formation of “new town” language]. Tokyo: Hitsuzi Syobo.Suche in Google Scholar

Choe, Hanwool. 2019. Eating together multimodally: Collaborative eating in mukbang, a Korean livestream of eating. Language in Society 48(2). 171–208. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0047404518001355.Suche in Google Scholar

Fujita, Yasuyuki. 2000. Kokugoinyōkōbun no Kenkyū [A Study of the Japanese Quotative Structure]. Osaka: Izumi Shoin.Suche in Google Scholar

Herring, Susan C. 2019. The co-evolution of computer-mediated communication and computer-mediated discourse analysis. In Patricia Bou-Franch & Pilar Garcés-Conejos Blitvich (eds.), Analyzing digital discourse: New insights and future directions, 25–67. London: Palgrave Macmillan.10.1007/978-3-319-92663-6_2Suche in Google Scholar

Holt, Elizabeth. 2007. ‘I’m eyeing your chop up mind’: Reporting and enacting. In Elizabeth Holt & Rebecca Clift (eds.), Reporting talk: Reported speech in interaction, 47–80. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511486654.004Suche in Google Scholar

Horiguchi, Sumiko. 1997. Nihongo Kyōiku to Kaiwa Bunseki [Japanese Language Education and Conversation Analysis]. Tokyo: Kurosio Shuppan.Suche in Google Scholar

Hosoma, Hiromichi & Harumi Muraoka. 2022. Enkaku Komyunikēshon no Jikan-teki na Zure wa Sōgo Kōi Bunseki ni Donoyōna Eikyō o Ataeuru ka [How Can Latency in Telecommunication Affect Action Sequence Analysis?]. Shakai Gengo Kagaku [The Japanese Journal of Language in Society] 25(1). 230–237.Suche in Google Scholar

Institute for Information and Communications Policy. 2024. Reiwa 5-nendo Jōhō Tsūshin Media no Riyō Jikan to Jōhō Kōdō ni Kansuru Chōsa [2023 survey on the usage of information communication media and information behavior]. https://www.soumu.go.jp/main_content/000953019.pdf (accessed 9 January 2025).Suche in Google Scholar

Kato, Yoko. 2010. Hanashi Kotoba ni okeru Inyō Hyōgen: Inyō Hyōshiki ni Chūmoku shite [Quotation Expressions in Spoken Language: Focusing on Quotative Markers]. Tokyo: Kurosio Shuppan.Suche in Google Scholar

Lawrenson, Emily. 2022. What is a VTuber? Why are they so popular? Qustodio. https://www.qustodio.com/en/blog/what-is-a-vtuber/ (accessed 9 January 2025).Suche in Google Scholar

Licoppe, Christian & Julien Morel. 2018. Visuality, text and talk, and the systematic organization of interaction in Periscope live video streams. Discourse Studies 20(5). 637–665. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445618760606.Suche in Google Scholar

Lu, Zhicong, Chenxinran Shen, Jiannan Li, Hong Shen & Daniel Wigdor. 2021. More Kawaii than a real-person live streamer: Understanding how the Otaku community engages with and perceives Virtual YouTubers. CHI ’21: Proceedings of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems 137. 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1145/3411764.3445660.Suche in Google Scholar

Nabeshima, Masaaki. 2021. Sutorīmingu no Rekishi [The History of Streaming]. https://www.kosho.org/blog/streaming/history/ (accessed 9 January 2025).Suche in Google Scholar

Nematzadeh, Azadeh, Giovanni Luca Ciampaglia, Yong-Yeol Ahn & Alessandro Flammini. 2019. Information overload in group communication: From conversation to cacophony in the Twitch chat. Royal Society Open Science 6(10). 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.191412.Suche in Google Scholar

Nishino, Junji. 2022. VTuber Bunka ni okeru Ikutsuka no Epokku [Several Epochs in VTuber Culture]. Nihon Chinō Jōhō Fajji Gakkai Fajji Shisutemu Shinpojiumu Kōen Ronbunshū [Proceedings of the Fuzzy System Symposium, Japan Society for Fuzzy Theory and Intelligent Informatics] 38. 494–497.Suche in Google Scholar

Okubo, Kanako. 2013. Kyōyū sareru Tasha no Kotoba: Senkyo Enzetsu ni Mochiirareru Zero-gata Inyō Hyōgen no Bunseki [Sharing Another’s Words: Zero Marked Qnotative in Political Campaign Speeches]. Shakai Gengo Kagaku [The Japanese Journal of Language in Society] 16(1). 127–138.Suche in Google Scholar

Olejniczak, Jędrzej. 2015. A linguistic study of language variety used on Twitch.Tv: Descriptive and corpus-based approaches. Redefining Community in Intercultural Context 4(1). 329–334.Suche in Google Scholar

Pires, Karine & Gwendal Simon. 2015. YouTube live and twitch: A tour of user-generated live streaming systems. In MMSys ’15: Proceedings of the 6th ACM Multimedia Systems Conference, 225–230.10.1145/2713168.2713195Suche in Google Scholar

Recktenwald, Daniel. 2018. The discourse of online live streaming on twitch: Communication between conversation and commentary. The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Ph.D. dissertation. https://theses.lib.polyu.edu.hk/handle/200/9795 (accessed 9 January 2025).Suche in Google Scholar

Rogers, Kara. 2023. Livestreaming. Encyclopedia Britannica 15. https://www.britannica.com/technology/livestreaming (accessed 9 January 2025).Suche in Google Scholar

Schegloff, Emanuel A. & Harvey Sacks. 1973. Opening up closing. Semiotica 8. 289–327.10.1515/semi.1973.8.4.289Suche in Google Scholar

Schoenenberg, Katrin, Alexander Raake & Judith Koeppe. 2014. Why are you so slow? Misattribution of transmission delay to attributes of the conversation partner at the far-end. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies 72(5). 477–487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2014.02.004.Suche in Google Scholar

Song, Le & Christian Licoppe. 2024. Noticing-based actions and the pragmatics of attention in expository live streams. Noticing ‘effervescence’ and noticing-based sequences. Journal of Pragmatics 226. 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2024.04.001.Suche in Google Scholar

Sunakawa, Yuriko. 2003. Wahō ni yoru Shukan Hyōgen [Subjective Expressions by Speech]. In Yasuo Kitahara (ed.), Asakura Nihongo Kōza 5 Bunpō 1 [Asakura Japanese Language Course 5 Grammar 1], 128–156. Tokyo: Asakura Shoten.Suche in Google Scholar

Tang, John, Venolia Gina & Kori Marie Inkpen. 2016. Meerkat and periscope: I stream, you stream, apps stream for live streams. CHI ’16: Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems 4770–4780. https://doi.org/10.1145/2858036.2858374.Suche in Google Scholar

Thurlow, Alex Brown. 2003. Generation Txt? The sociolinguistics of young people’s text-messaging. Discourse Analysis Online 1–1. http://extra.shu.ac.uk/daol/articles/v1/n1/a3/thurlow2002003-01.html (accessed 9 January 2025).Suche in Google Scholar

User Local, Inc. 2022. VTuber (Bācharu YūChūbā), Tsui ni 2 Man-nin o Toppa (Yūzā Rōkaru Shirabe) [VTubers (Virtual YouTubers) finally exceed 20,000 (according to user local)]. https://www.userlocal.jp/press/20221129vt/ (accessed 9 January 2025).Suche in Google Scholar

User Local, Inc. 2024. Fan-sū Rankingu [Fan Count Ranking. https://virtual-youtuber.userlocal.jp/document/ranking (accessed 9 January 2025).Suche in Google Scholar

YouTube. n.d.a. How to earn money on YouTube. https://support.google.com/youtube/answer/72857 (accessed 9 January 2025).Suche in Google Scholar

YouTube. n.d.b. Live streaming latency. https://support.google.com/youtube/answer/7444635 (accessed 9 January 2025).Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Advancements in Japanese linguistics: diverse perspectives

- Articles

- Stem inalterability in Japonic

- Restructuring and focus in Japanese

- When syntax and semantics of compounds matter to voicing alternations: an experimental investigation of effects of grammatical relation on rendaku

- Temporal dynamics of alignment: unveiling new semantic dimensions in interpreting the illocutionary particle ne in Japanese

- Discourse analysis of “just chatting” streams on YouTube live: focusing on the interaction between virtual YouTubers and viewers

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Advancements in Japanese linguistics: diverse perspectives

- Articles

- Stem inalterability in Japonic

- Restructuring and focus in Japanese

- When syntax and semantics of compounds matter to voicing alternations: an experimental investigation of effects of grammatical relation on rendaku

- Temporal dynamics of alignment: unveiling new semantic dimensions in interpreting the illocutionary particle ne in Japanese

- Discourse analysis of “just chatting” streams on YouTube live: focusing on the interaction between virtual YouTubers and viewers