Abstract

The imagery of Nebuchadnezzar’s divine affliction in Daniel 4 is as complex as it is fantastic. A variety of literary images interweave to present the king’s affliction in explicitly animalising terms. Despite this complexity, most visual depictions of the text focus on a largely similar image – that of Nebuchadnezzar eating grass or living naked in the wild. However, in a 17th-century English tapestry series associated with Thomas Poyntz, an altogether different scene is envisioned. Nebuchadnezzar is portrayed as fully clothed in the city of Babylon and, even more intriguingly, is explicitly depicted with both birds’ claws and feathers. This paper outlines trends in visually depicting Nebuchadnezzar’s affliction in art and then examines the tapestry’s visual portrayal of Daniel 4. In so doing, it is observed how the tapestry is distinctive in representing both the divine pronouncement and seeming enactment of this affliction in one image, as well as discerning the influence of lycanthropic interpretations of Daniel 4. Finally, this paper returns to read the biblical narrative in light of this unusual visual representation and observes how it draws the reader’s attention to two often overlooked textual features: the absence of other characters within this specific scene, and the rapidity with which Nebuchadnezzar’s affliction commences.

1 Introduction

“He could see it clearly. If it was a man, he was covered with feathers, but not like a bird – the quills had been pushed like needles into his skin … ”[1] This is how we are first introduced to the eponymous character of Jeremy de Quidt’s 2012 Carnegie Medal nominated book The Feathered Man. This young adult story focusses on a tooth-puller’s boy, a stolen diamond, and his pursuit by both a Jesuit priest and a villainous landlady. At times it is quite a disturbing tale but the queerest aspect of the book is this human-like figure who appears covered in feathers. De Quidt claims to have been inspired to create the character and write the story when his daughter was given a life-sized feather and chicken-wire sculpture of a kneeling man.[2]

So too, this paper was also inspired by encountering a feathered man, albeit in a tapestry at Glamis Castle. This image, which has been associated with the tapestry maker Thomas Poyntz and called: Nebuchadnezzar Transformed into a Beast,[3] appears to depict the effects of Nebuchadnezzar’s affliction in Daniel 4 (see Figure 1). This distinctively portrays the biblical character’s limbs as sprouting feathers, and such imagery is not reflected in other visual representations of this narrative. While the reception of the Bible has increasingly been the focus of much contemporary biblical scholarship, tapestries of biblical scenes, events and characters have often been overlooked by biblical scholars working on how the Bible has been used. This paper will therefore attempt to highlight some of the fruitful insights biblical scholars can glean by being attentive to biblical receptions in tapestries and encourage further research in this area. Firstly, a brief description of the tapestry itself will be undertaken. The paper will then examine how the tapestry has been influenced by previous artistic trends and contemporary 17th-century discourse to depict the specific nature of Nebuchadnezzar’s transformation and the context in which it takes place. In so doing, further light will be shed upon how this particular reception relates to the text and other interpretations of it. Finally, this paper will return to the text to see what new insights this tapestried image can provide for readers of Daniel 4.

Nebuchadnezzar Transformed into a Beast. Image courtesy of The Earl of Strathmore and Kinghorne, Glamis Castle.

2 Tapestry and Background

There has been a set of tapestries depicting “The Story of Nebuchadnezzar” in the British Isles since at least 1468 when King Edward IV of England purchased a four-piece set from the Flemish tapestry weaver Pasquier Grenier.[4] While these have not survived, records show they were cleaned multiple times up to 1590 and were much valued during Henry VIII’s reign.[5] Nevertheless, there is still an extant 17th-century tapestry series depicting biblical narratives related to Nebuchadnezzar in the UK. This five-part series depicts several scenes related to the biblical King Nebuchadnezzar including: “The Triumph of Nebuchadnezzar” (cf. Dan 1:2); “The Golden Idol” (cf. Dan 3:1–7); “The Fiery Furnace” (cf. Dan 3:8-23); and “Nebuchadnezzar’s Dream” (cf. Dan 4:4–27). The final image in this tapestry series, known as “Nebuchadnezzar Transformed into a Beast,” is a depiction of Nebuchadnezzar’s animalising affliction in Dan 4:28–33 (see Figure 6).[6] The cartoons for this five-part Nebuchadnezzar tapestry series were also apparently used for further sets of tapestries, of which three others are known and contain varying degree of extant panels (see Table 1).

The location of extant sets of The Story of Nebuchadnezzar tapestry seriesa

| Location | Extant panels |

|---|---|

| Glamis Castle (Angus, Scotland)b | The Triumph of Nebuchadnezzar The Golden Idol The Fiery Furnace Nebuchadnezzar’s Dream Nebuchadnezzar Transformed into a Beast |

|

|

|

| Knole (Kent, England)c | The Triumph of Nebuchadnezzar The Golden Idol The Fiery Furnace Nebuchadnezzar’s Dream Nebuchadnezzar Transformed into a Beast |

|

|

|

| Powis Castle (Powys, Wales)d | The Triumph of Nebuchadnezzar The Golden Idol – Nebuchadnezzar’s Dream Nebuchadnezzar Transformed into a Beast |

|

|

|

| Dispersed Sete | – – The Fiery Furnace Nebuchadnezzar’s Dream Nebuchadnezzar Transformed into a Beast |

-

aThe table lists out where sets of this tapestry series are currently located, and which particular panels are known to have survived from each set. If a specific panel is missing from a set this is indicated in the table through the use of: –. bThe panel of “Nebuchadnezzar’s Dream” has sadly been cut in half. For information on the Glamis Castle tapestries, see: David Scott-Moncrieff, “Glamis Castle, Forfar,” Country Life 108, October 27, 1950, 1408–1413. cFor information on this set and its supposed connection to the crown, see: Helen Wyld, “Nebuchadnezzar Transformed into a Beast: NT 1181084.4,” (2013), accessed June 23, 2023, https://www.nationaltrustcollections.org.uk/object/1181084.4. dFor information on the Powis Castle set, see: Helen Wyld, “Nebuchadnezzar Transformed into a Beast: NT 130090.1.” eThese three panels are all known to have circulated on the private art market in recent years. The Victoria and Albert Museum in London now houses “The Fiery Furnace.” It remains possible that the other two panels still exist but remain in private hands.

These tapestries have been associated with Thomas Poyntz, an associate and possible relative of Francis Poyntz (1632–1684) who was the Yeoman Arras Worker to King Charles II.[7] This ascription is based on the presence of the initials “T P” surrounding a St George’s cross on a white shield that is found on three tapestries in the Knole set.[8] Francis Poyntz, who was artistic director at Mortlake in 1670 before eventually setting up his own workshop, seems to have become the favoured tapestry manufacturer of the crown under the reign of Charles II.[9] Comparatively little is known about Thomas Poyntz (fl. 1660 – d. after 1688). The first mention of him is in 1678[10] and he seems to have taken over Francis’ workshop upon his death.[11] The tapestries produced at the workshop under his name continued to fetch high prices which perhaps reflects the quality of the work produced.[12] This information, along with an inventory of Knole in 1682 which documents five tapestries of Nebuchadnezzar,[13] allows the Knole set to be given a rough date between 1678–1682.[14] The other tapestry sets can presumably be dated around the same time period, although which might be the oldest is difficult to determine.[15]

The origin of the painted cartoons used for the design of the Nebuchadnezzar tapestries is unknown. One suggestion is that the designer was Flemish due to correspondences between these tapestries and a series depicting scenes related to Jeptha which originated in Antwerp.[16] The choice of this subject for the tapestry is undoubtedly influenced by religious attitudes about idolatry at the time. In 17th-century post-Reformation Britain the danger of idolatry seems to have led to a shift in the visual arts whereby New Testament subjects, with their propensity to feature the divine or Jesus, were avoided in favour of Old Testament scenes which could circumvent issues surrounding idolatrousness.[17] It is not until the 18th century that a tradition of religious art really seems to re-emerge in the British Isles.[18] The selection of Nebuchadnezzar as the subject of these tapestries is therefore in keeping with this wider trend within the visual arts of the 17th century to focus on the Old Testament.

Of the five known panels in this Nebuchadnezzar series, the tapestry of “Nebuchadnezzar Transformed into a Beast” is the last. This image is clearly focused on the figure of the Babylonian king who appears in the very centre of the tapestry. The depiction of the king’s appearance generally seems to match that found in the other tapestries within the Story of Nebuchadnezzar series too. He is ornately dressed with armour, a blue undertunic, and a rich red robe. He has a long beard, carries a sword at his hip, and wears a bejewelled breastplate and boots. As with the rest of the series, Nebuchadnezzar’s rich apparel reflects his royal status. Unlike the other scenes in the series though, Nebuchadnezzar’s appearance seems to be in some degree of disarray. His blue tunic is ragged, he appears to be in the process of removing his cloak, and he has apparently cast both his crown and sceptre onto the ground. In the other tapestries in the series, when he is not seated upon his throne, Nebuchadnezzar is portrayed as standing in a commanding fully upright posture. However, here he is crouched and stands little over half his full height when compared to other people within the scene. The clearest contrast to other panels in the series is that the tapestry depicts the king as having feathers, rather than hair, growing out from his arms and legs. Furthermore, Nebuchadnezzar’s hands also sport long and sharp fingernails.

In addition to the king, the tapestry also contains various other elements. The king is portrayed as standing on a patterned marble floor leading to a flight of steps. He is surrounded by buildings with columned elements and in the distance are glimpses of still further buildings. All copies of this tapestry include a number of other people in the scene. A cluster of figures is located behind the flight of steps and another individual is standing above and in front of them. There are also two further people who appear on the right of the image who are dressed as military figures.[19] These two soldiers have their hands raised and their eyes open wide in seeming astonishment. Equally, the prominent figure on the left has a look of terror on their face and appears to be in the process of fleeing the scene.[20] A dark dog wearing a red collar is also included at the front of the image and it gazes up at the king open-mouthed. Finally, a curious wiggly line proceeds from the top of the image towards Nebuchadnezzar’s head.

3 Analysis of the Tapestry’s Reception of Daniel 4

To begin an assessment of this tapestry’s portrayal of the king’s affliction in Daniel 4, focus will start with a brief outline of the biblical text itself, then turn to consider Nebuchadnezzar within the tapestry, and finally other elements within the image.

Within the biblical narrative of Daniel 4, there are several scenes. The text opens with an epistolary introduction as the king addresses his subjects and praises God (Dan 4:1–3).[21] Nebuchadnezzar then relates how he had a dream and various advisers attempted to interpret it (Dan 4:4–9). He then describes the dream to Daniel (Dan 4:10–18) who interprets it for him (Dan 4:19–27). The key scene is perhaps the description of Nebuchadnezzar’s affliction in Dan 4:28–33. Here, Nebuchadnezzar was walking in the royal palace of Babylon and declared the glory of the city he has built (Dan 4:29). After this, a heavenly voice proclaims that he will be afflicted (Dan 4:31–32). This is then fulfilled, and the details of Nebuchadnezzar’s affliction are outlined: “he was driven away from human society, he ate grass like oxen, and his body was bathed with the dew of heaven, until his hair grew as long as eagles’ feathers and his nails became like birds’ claws” (Dan 4:33). Eventually the king is restored in his condition (Dan 4:34) and this is reiterated again later where he states: “At that time my reason returned to me, and my majesty and splendour were restored to me for the glory of my kingdom. My counsellors and my lords sought me out, I was re-established over my kingdom, and still more greatness was added to me” (Dan 4:37).

In the “Story of Nebuchadnezzar” tapestry series, the first section of the biblical text (Dan 4:1-27) appears in the “Nebuchadnezzar’s Dream” panel. The final section of the narrative, which contains the unusual account of Nebuchadnezzar’s affliction, is then portrayed in the tapestry of “Nebuchadnezzar Transformed into a Beast.” There is a rich history of visual depiction of the king’s affliction, nevertheless these representations tend to tread a similar path and portray Nebuchadnezzar during his appointed time of affliction as a man living wild.[22] This tapestry diverges from this trend in a number of distinct ways, and these will now be addressed.

Firstly, this tapestry attempts to depict the moment at which Nebuchadnezzar’s affliction is pronounced to him (Dan 4:31–32). As noted earlier, the king has thrown off his crown and sceptre, and is removing his cloak. This is a highly symbolic portrayal signalling the fact that Nebuchadnezzar has lost his kingly status and position.[23] Specifically, these elements reflect the heavenly pronouncement preceding Nebuchadnezzar’s affliction, that “O King Nebuchadnezzar, to you it is declared: The kingdom is taken from you!” (Dan 4:31).[24] This is further corroborated by the wiggly line which connects the king’s head to the top of the tapestry. This represents the voice coming down from heaven in Dan 4:31.[25] This method of representing divine speech without visually depicting the deity seems to correspond with a 17-century artistic trend which avoided depicting God.[26] The final feature of the tapestry which resembles this moment in the Danielic narrative is the wider setting of the scene. Unlike the other artistic portrayals of Nebuchadnezzar’s affliction, this tapestry is not set in the wilderness. This evidently urban setting reflects the context of the textual scene where Nebuchadnezzar “was walking on the roof of the royal palace of Babylon” (Dan 4:29) when the heavenly voice pronounced his affliction.[27] It is therefore fair to conclude that the tapestry depicts events that take place in Dan 4:28-33 where Nebuchadnezzar’s affliction is announced to him while he is still living and reigning in Babylon and before he has been “driven away from human society” (Dan 4:33).

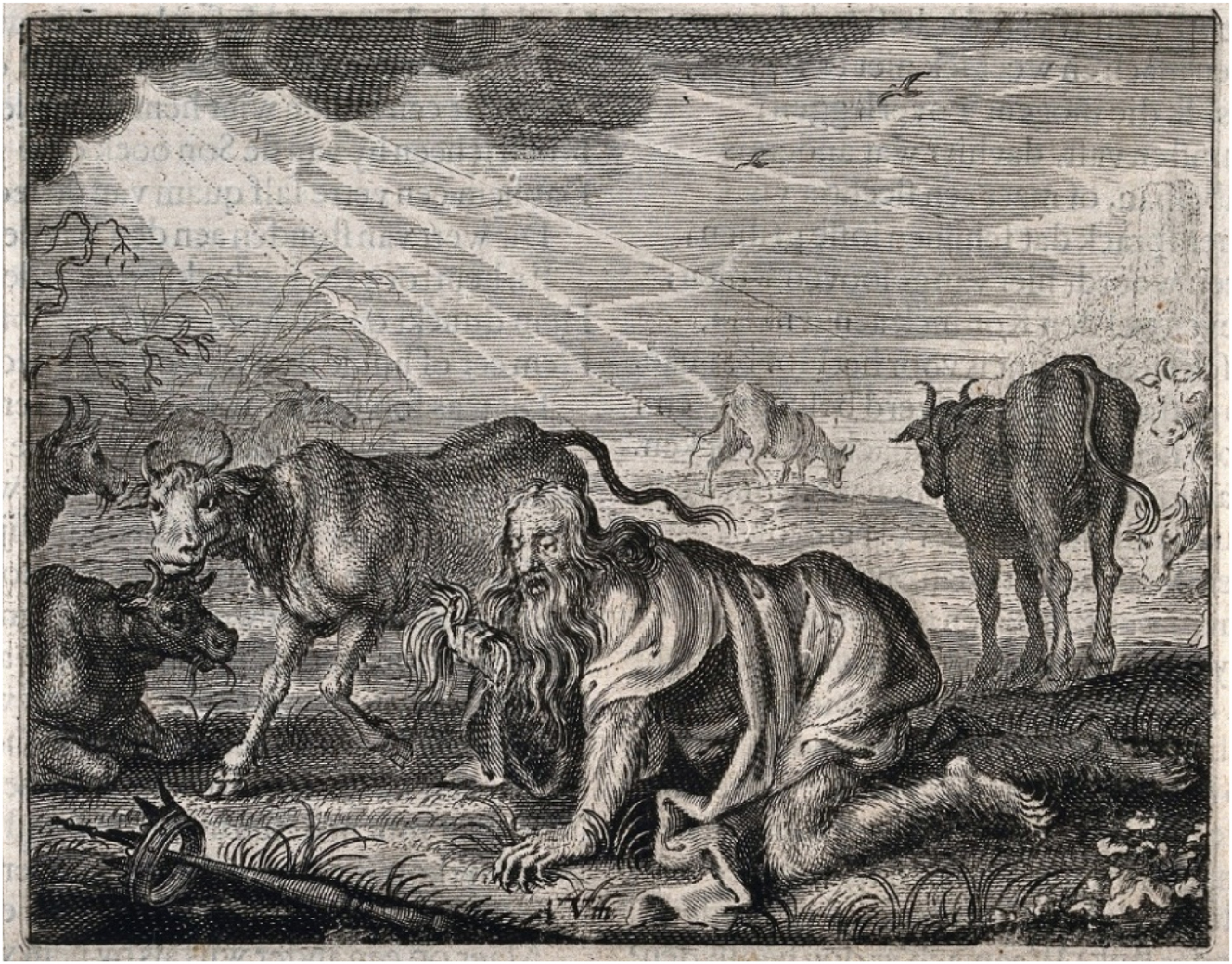

This observation is remarkable because there are few, if any, visual depictions of Nebuchadnezzar’s affliction being pronounced upon him.[28] Most depictions of Nebuchadnezzar portray him as a man living with animals, albeit with neglected appearance and behaving like an animal. Common features to these representations include showing Nebuchadnezzar crawling around on all-fours, eating grass, long hair, long fingernails and toenails, and depictions of him unclothed. For example, the 11th century Roda Bible contains such a representation,[29] as does Rudolf von Ems’ 14th Weltchronik (see Figure 2). Similar characteristics are highlighted in later textual illustrations such as in Nicolas Fontaine’s The History of the Old and New Testament of 1703 (see Figure 3), however here we also see Nebuchadnezzar in the process of consuming grass too. Interestingly, this latter depiction seems to have influenced perhaps the most famous image of Nebuchadnezzar’s affliction in Dan 4: that by William Blake.[30] Other portrayals vary somewhat by depicting Nebuchadnezzar as clothed while in the wilderness, albeit still on all-fours, eating grass, and with long hair or nails (see Figure 4). Further examples (see Figure 5) often add cattle to the scene, seemingly to illustrate how the king “ate grass like oxen” (Dan 4:33). So common is this image of Nebuchadnezzar afflicted in the wild that we might be forgiven for presuming that all these common elements are reflected in the text. However, a naked king walking on all fours is not found in the Aramaic text at all.[31]

Nebuchadnezzar in Rudolf von Ems, Weltchronik (Regensburg: ca. 1400–1410), f. 215v. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 33. Image in Public Domain.

Nebuchadnezzar Deposed and Driven Away in Nicolas Fontaine, The History of the Old and New Testament Extracted Out of Sacred Scripture and Writings of the Fathers, 3rd ed. (London: 1703). Image in public domain and retrieved from Pitts Theology Library, Emory University.

Scenes from the Life of King Nebuchadnezzar by Nicola di Maestro Antonio d’Ancona (ca. 1490) in The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Image in the public domain.

Nebuchadnezzar, Gone Mad, Grovels Like a Beast of the Earth; He Gropes for His Crown, ca. 17th-century Dutch line engraving. Image in the public domain.

The Banishment of King Nebuchadnezzar by Rombout van Troyen (1641). Image in the public domain.

Nonetheless, this tapestry does not just portray the pronouncement of the king’s divine affliction, but also depicts the enactment of this affliction too. As noted previously, the affliction has begun as the king has already discarded his crown and sceptre, indicating that his kingdom has symbolically been taken from him. However, the full extent of the affliction has not yet manifested itself as he is only in the process of ripping off his robe which, when complete, would presumably result in Nebuchadnezzar living without clothes with the animals. Equally, his stance also indicates this process of his affliction taking hold. The king has declined from the standing position he adopts in other tapestry panels to a kneeling position here. This moves him physically towards the ground and indicates the process of Nebuchadnezzar moving towards walking on all fours. Both nakedness and quadrupedalism are common features within the tradition of visually depicting Nebuchadnezzar’s affliction outlined above, and it is therefore likely that this tapestry visualises the process of Nebuchadnezzar’s transformational change into this commonly conceived image.

This visualisation of the enactment of the king’s affliction appears to have been influenced by existing imagery of how Nebuchadnezzar was banished to the wilderness. For example, Rombout van Troyen’s 1641 painting “The Banishment of King Nebuchadnezzar” similarly portrays the beginning of the king’s affliction using some of these same methods (see Figure 6). Nebuchadnezzar is kneeling, has had some of his clothing removed, and no longer wears his crown. These same elements are also used here to suggest that the king’s transformational change has begun but is not quite completed. The tapestry of “Nebuchadnezzar Transformed into a Beast” therefore seems to be adopting some of these known elements of visualising the enactment of the king’s affliction.

The most striking element of this transformational process Nebuchadnezzar is undergoing is perhaps the animalisation. As with most visual representations (see above), Nebuchadnezzar’s nails have grown long “like bird’s claws” (Dan 4:33). However, while other portrayals represent how “his hair grew as long as eagles’ feathers” (Dan 4:33) by showing Nebuchadnezzar with abnormally long facial hair, head hair, or body hair (see Figure 2), this tapestry distinctively presents his arm and leg hair as having actually become feathers. Unlike other early modern interpretations and representations of this passage which emphasise Nebuchadnezzar’s bovine similarity when he is afflicted (see Figure 5), the emphasis here is on his avian similarity.[32]

This feathered depiction of Nebuchadnezzar indicates that the king’s affliction is being understood as involving some degree of bodily metamorphosis.[33] Interestingly, despite a history of such interpretation, visual depictions of Daniel 4 almost never attempt to portray Nebuchadnezzar so that he looks like an actual non-human animal.[34] Anat Tcherikover has suggested that this is the case because “a metamorphosised Nebuchadnezzar, would be difficult to trace in the visual arts, simply because it would hardly be possible to recognise the fallen king among other animals and monsters.”[35] Perhaps this is true, however even in examples where the illustration is clearly labelled there is little evidence that suggests Nebuchadnezzar was depicted as physically metamorphosing into another animal. Instead, images of the king’s affliction in Daniel 4 seem to accord mainly with a tradition of interpreting the king’s affliction as about his mind and rational capabilities, perhaps seen most significantly in John Hamilton Mortimer’s 1772 drawing of “Nebuchadnezzar Recovering His Reason.”[36]

Furthermore, an animal metamorphic interpretation of Daniel 4 seems to have been particularly popular in early modern Europe following a revival of interest in early modern Europe following a revival of interest in werewolves and lycanthropy in the fifteenth to seventeenth centuries.[37] The prime example of this is Jean Bodin, the French lawyer and philosopher, who argued that the existence of werewolves “is confirmed by the sacred history of King Nebuchadnezzar, about whom the Prophet Daniel speaks, he was converted and transformed into an ox.”[38] In Bodin’s understanding, Nebuchadnezzar’s affliction is seen as a lycanthropic change albeit into an ox rather than a wolf. This was influential throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries with many European writers following Bodin in concluding that Nebuchadnezzar physically transformed into an animal.[39] This tapestry, which was created within a context where such interpretations were still influential, therefore plausibly reflects a similar understanding of the narrative.

Such a lycanthropic understanding of events in Daniel 4 is also indicated by the presence of a dog which appears to the left of Nebuchadnezzar. This prominently placed canid is absent in all other panels in the tapestry series and yet is found in all four versions of this specific scene.[40] This contrasts notably with how various other elements and figures within the tapestry vary from set to set. This recurrence of the dog and its prominent placement in the image suggests it holds significance. In Christian art, dogs often represent either fidelity or, particularly when they are dark in colour, evil or disbelief.[41] As dogs were used as a model or mirror for the human’s behaviour in art, the dog could be a comment upon Nebuchadnezzar’s own unbelief.[42] However, it might also be suggestive of the kind of transformation imagined for the king by embodying or modelling the perceived change he will undergo.

An additional piece of evidence which might support such an interpretation of the affliction in this tapestry is the presence of several other figures in the scene. This alone is interesting as it is uncommon for visual depictions of Daniel 4 to include other human figures in the scene.[43] In this tapestry, besides Nebuchadnezzar, the three other full-size people all express their horror at what is happening to the king. It is certainly worth observing that the dog also seems to recoil from the king here, as it gazes open-mouthed at his changed appearance. The reactions of these characters guide the viewer also to recognise the horror of the depicted events. This additionally might suggest the tapestry intends to portray a physical animal transformation, as a man who simply begins to behave like an animal or rip his clothes is odd, but a man who begins to acquire animal features is perhaps truly horrifying.

While it has been noted how most depictions of Daniel 4 do not include other human figures, there are a few examples that do. For example, van Troyen‘s painting (Figure 6) contains a number of people surrounding Nebuchadnezzar who are seemingly ushering him away. Another is the second panel of d’Ancona’s presentation of Daniel 4 (Figure 4) where a crowd of people follow the bearded king out of the city’s gate. In such scenes, the other characters are presented as attempting to remove Nebuchadnezzar from their society. The tapestry’s portrayal seems to be influenced by this less-common tradition of human characters being involved in banishing the king. However, it also provides a different take as, instead of being involved in the banishment itself, the other people seem merely to react emotionally to Nebuchadnezzar’s change. This is likely due to the change in scene as the tapestry portrays the pronouncement of the affliction rather than the complete banishment of the king. A further influence may be Jacob Pynas’ 1616 painting of “Nebuchadnezzar Restored to Royal Dignity” which is also set in the city and depicts Nebuchadnezzar surrounded by citizens of Babylon. These other characters appear to welcome the king back, whereas in the tapestry they reject him. Pynas’ work reflects Nebuchadnezzar’s later acceptance into the city by his courtiers (Dan 4:26), but this tapestry might have been inspired by it to mirror a similar scene before the affliction begins. This indicates that the tapestry is creatively combining the perceived role of other characters in banishing the king and welcoming him back.

It is thus clear that the feathered imagery of Nebuchadnezzar in this tapestry is influenced by a trend in interpreting Daniel 4 as involving a physical human-to-animal metamorphosis. However, this does not explain the curious and distinctive depiction of the king with feathered arms. While there is little evidence of Nebuchadnezzar undergoing a bird-like metamorphosis in visual representation of Daniel 4, one early interpretation does allow for such an impression. The 4th-century Christian Aphrahat writes that Nebuchadnezzar goes through various stages of animal transformation where he becomes like, for example, a lion and a cow. Interestingly, Aphrahat also distinctively describes how “when Nebuchadnezzar went out to the wilderness with the beasts he grew hair like (the plumage) of an eagle” and “there was given him the heart of a bird. And when wings grew upon him like those of an eagle, he exalted himself over the birds” (Aphrahat, Demonstrations 5.16).[44] This interpretation relies upon a perceived connection between Daniel 4 and Dan 7:4 to understand Nebuchadnezzar’s affliction as involving his sudden growth of wings.[45] In this tapestry though, instead of acquiring an eagle’s wings the hairs on Nebuchadnezzar’s limbs simply become feathers. This suggests a textual relationship with Dan 7:4 is not behind this portrayal and it is reliant only on Dan 4:33 where “his hair grew as long as eagles’ feathers.”[46]

Instead of an intertextual allusion to Dan 7:4, this portrayal of Nebuchadnezzar’s metamorphosis and acquisition of physical feathers growing out from his limbs might find its origin elsewhere. In 17-century England, tapestries of Old Testament subjects were used to symbolise moral, theological, or political messages.[47] Such a political message might explain the feathered depiction in the tapestry of “Nebuchadnezzar Transformed into a Beast.” The depiction of a king’s downfall would have been pertinent amidst the recent context of the English Civil Wars and the execution of King Charles I in 1649. Nebuchadnezzar imagery from Daniel 4 was often used to comment upon Charles’ rule and as a reminder that oppressive kings will come to a sticky end.[48] The enactment of the affliction in Daniel 4 was explicitly used as a metaphor for the wresting of powers away from the king. For example, in 1648, Verity Victor writes about the king’s wish to retain control of the militia: “In a word to grant the Kings desire in this, would be like the hewing down Nebuchadnezzars mighty Tree, and cutting off the branches and leaves thereof: yet leaving the stump of the roots thereof in the earth with bands of iron and brass. No, let us up with root and all.”[49] Even Royalist writers such as Robert Bacon make this parallel and present Charles I boasting about the great buildings he has built in a clear allusion to Dan 4:30.[50] This presentation of Charles I as another proud Nebuchadnezzar who is ultimately humiliated might explain the feathered imagery here. In the early modern period, a common practice of public punishment or humiliation was that of tarring and feathering (whereby a person is stripped, coated in tar, then covered in feathers). Records of this being carried out in 17th-century London include the mob punishment of a London bailiff in 1696.[51] The feathered depiction of Nebuchadnezzar, representing Charles I, on this tapestry would suggest the eventual public punishment of the king when he lost his kingdom at his execution, albeit the humiliation is depicted as a “genuine” feathering rather than involving tar as an adhesive. As this tapestry was ostensibly created after the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660, its subject matter might have been perceived as a cautionary tale for how kings, including very recent ones, can fall and thus the new monarchy under Charles II should proceed in light of such events.[52]

From this analysis, it has been shown how the tapestry of “Nebuchadnezzar Transformed into a Beast” adopts a number of elements common to the main tradition of visually depicting Daniel 4. The king has long nails, appears to have lost his kingship, and there are hints he is understood as embracing both nakedness and quadrupedalism when he is afflicted. However, Poyntz’s tapestry is also distinctive in a number of ways. Perhaps most interestingly, the king’s affliction incorporates various physical animalising changes including his apparent covering in feathers. This may be an example of a visual representation that imagines Nebuchadnezzar undergoing a physical metamorphosis. The distinctive feathered imagery itself seems to arise as part of 17-century discourse which associated Charles I with Nebuchadnezzar and so portrays a literal feathering of the king as a just humiliation. In addition, unlike most images of Nebuchadnezzar in Daniel 4, the scene is set within the city of Babylon and depicts the moment of the pronouncement of the king’s affliction by a heavenly voice. Moreover, this is combined with the process of the enactment of the pronouncement, and the king is portrayed as beginning to undergo the various elements associated with his divine affliction.

4 Returning to Daniel 4

In light of these observations, we can return to the biblical narrative in order to see how this depiction might impact a reading of Daniel 4. To do this, I will focus on two elements: the specific imagined scene, and the presence of other characters within the scene itself.

Firstly, therefore, the tapestry has been noted as depicting a scene which incorporates both the pronouncement and the enactment of Nebuchadnezzar’s affliction, which is presented as happening in discrete stages as Nebuchadnezzar goes through a process of change. Interestingly, when this is compared with the narrative in Daniel 4, the process of the enactment of the affliction is described very sparsely. It is simply stated that: “immediately the sentence was fulfilled against Nebuchadnezzar” (Dan 4:33). In Aramaic that which is rendered “immediately” in the NRSV is literally “בה־שׁעתא” or “in that moment.” The fulfilment (Aramaic: ספת) of his affliction happens in a remarkably short time frame and this sudden onset of his affliction has often been remarked upon by commentators.[53] Yet, it has not been acknowledged how the rapidity of the biblical narrative at this point obscures the actual moment when the king is afflicted. Instead of providing a description of how this affliction took place, the narrative almost glosses over this, states quite plainly that it happened in an instant, and provides no further detail. The tapestry therefore imagines a scene not depicted in the biblical text: the specific moment of his transformational affliction. This depiction also highlights the terseness of the biblical narrative at this point, the gap in its description of how this moment could have occurred, and how Nebuchadnezzar may have reacted to it.[54]

Furthermore, while the narrative suggests the pronounced affliction was fulfilled in an instant, it is clear that not all elements of this affliction happened all at once. For example, after this single moment, Nebuchadnezzar still needs to be “driven away from human society” and be “bathed with the dew of heaven” (Dan 4:33). Moreover, the lengthening of his nails and hair appear to indicate the passage of time as they need to be ignored long enough to grow to such a length.[55] These statements hint at a more delayed process of its enactment. Despite what the narrative explicitly claims, the complete fulfilment of Nebuchadnezzar’s sentence is therefore not immediate – neither in the tapestry nor in the biblical narrative.

These interesting differences might be further underlined if Daniel 4 MT is compared with the parallel tradition of Daniel 4 OG where the onset of the affliction is described thus: “by early morning everything concerning you will be completed” (Dan 4:30 OG). This does not rely upon an instantaneous fulfilment of the divinely pronounced affliction and instead suggests that time is required for all the elements to be manifest. While this still does not provide a description of how exactly this was enacted, it does allow a more realistic timeframe for the various elements to occur. This only further indicates the interesting immediacy and rapidity of the onset of Nebuchadnezzar’s affliction in Daniel 4 MT.

Secondly, it has been noted that the tapestry includes additional human figures in the scene who seem to guide the viewer to be horrified at the affliction of the king. Yet, it has not thus far been acknowledged that all these figures are without precedent in the pronouncement/enactment scene within Dan 4:28–33. From when Nebuchadnezzar is described walking in his palace in Babylon, to the pronouncement of the heavenly voice, to his removal from human society, there are no other human characters explicitly mentioned. The difference between text and tapestry on this point is striking but might be seen as instructive for an understanding of the textual scene here. While no other characters are present in this specific pronouncement scene, the wider narrative of Daniel 4 does contain other characters. Earlier in the text, various “magicians, the enchanters, the Chaldeans, and the diviners” are all mentioned as being consulted by the king (Dan 4:7), as well as the figure of Daniel himself (Dan 4:8). Furthermore, at the close of the narrative, Nebuchadnezzar states that “my counsellors and my lords sought me out” (Dan 4:36). When Nebuchadnezzar’s affliction is pronounced and enacted however, the text omits mention of these supporting characters. If his counsellors were to seek him out at the end of his affliction, readers might expect them to be present at its commencement too. To return to the tapestry, it could be argued that this depiction is resolving this seeming difficulty in Daniel 4 by furnishing the scene with characters mentioned elsewhere in the text. This makes the tapestry’s scene more rounded but further highlights the absence of these characters in Daniel 4 itself.

Additionally, once included, these additional characters play a role in the depicted scene. They are all apparently horrified at what is happening to Nebuchadnezzar and yet their subsequent action on the basis of this emotional response can only be hinted at. Presumably their horror would lead to a rejection of the king, (as presented in other depictions; see Figure 6), and the reaction of the figure on the left, who is seemingly fleeing the scene, is suggestive of just such a response. This aspect of the king’s rejection actually seems to find a parallel in the biblical narrative which states Nebuchadnezzar was “driven away from human society” (Dan 4:33). The king is explicitly stated to have been cast out of the city. However, as this is phrased passively, the agent of the action is obscured.[56] The tapestry seems to supply this missing agent and appears to suggest that Nebuchadnezzar was driven out by these horrified courtiers.[57] This addition to the tapestry’s depiction of the scene only further highlights the gap in Daniel 4 and the necessity for readers of the narrative to similarly implicitly supply an imagined agent here.

Again, comparison with Daniel 4 OG can bring these issues into clearer focus. On the one hand, Daniel 4 OG omits mention of all other human characters, with the exception of Daniel and Nebuchadnezzar, resulting in the complete absence of the king’s courtiers and diviners throughout the narrative (cf. 4:15, 33 OG).[58] It is therefore no surprise that they are absent in the heavenly pronouncement scene in this edition. However, this makes their absence in this scene in Daniel 4 MT all the more noticeable as, if they are referred to in other scenes in the narrative, their absence here is awkward. Interestingly, as well as this difference, Daniel 4 OG is also not troubled by the ambiguity surrounding the agent of the king’s exile. These agents are referred to specifically in Dan 4:29: “And the angels will drive you for seven years, and you will never be seen nor will you ever speak with any human. They will feed you grass like an ox, and your pasture will be the tender grass of the earth. Behold, instead of your glory they will bind you” (Dan 4:29 OG). Here, therefore, Nebuchadnezzar is driven out of his kingdom by angelic figures. This plays into the general portrayal in Daniel 4 OG of Nebuchadnezzar’s affliction as a divine punishment for his destruction of Jerusalem’s temple.[59] This parallel tradition again highlights the ambiguity regarding the agents behind Nebuchadnezzar’s exile in Daniel 4 MT, something which a close engagement with Poyntz’s tapestry also reveals about the Aramaic text, and which again the reader of the narrative would need to supply themselves.

These are, I argue, two ways in which an engagement with the visual depiction in this tapestry can highlight aspects of Daniel 4 which otherwise go unappreciated in a cursory reading of the text: the immediacy of the transformational scene, and the absence of other characters within this moment.

5 Conclusions

This essay has critically engaged with a 17th-century English tapestry known as “Nebuchadnezzar Transformed into a Beast” and the various distinctive ways in which it has engaged with the text. Taken on its own merits, this is an interesting example of early modern tapestry depicting a biblical scene not commonly found within textile art. Moreover, the precise portrayal is also distinctive when compared to other depictions of Nebuchadnezzar’s affliction as it centres on the scene of the pronouncement of Nebuchadnezzar’s affliction while he is still in Babylon as well as incorporating elements of the enactment of this affliction too. Perhaps the most striking aspect of the image is the sight of feathers growing from Nebuchadnezzar’s limbs. This demonstrates an awareness of the early modern shift in interpretation to view Nebuchadnezzar’s affliction as incorporating elements of a physical lycanthropic-style transformation, as well as an engagement with 17th-century discourse comparing Charles I with Nebuchadnezzar. Finally, this paper returned to look again at Daniel 4 and observed how the processual way in which the king’s affliction is depicted in the tapestry can lead us to consider the relative rapidity with which Nebuchadnezzar seemingly transforms in the text. Equally, cognizant of the presence of other characters within the tapestry, this essay has noted the striking absence of other characters in the biblical scene when Nebuchadnezzar is afflicted. The courtiers are absent, and the agents of the king’s expulsion are not specified. Through its seeming attempts to fill these gaps and provide additional figures within the scene, the tapestry’s portrayal also brings into focus these confusing aspects of the narrative which a reader is required to subconsciously account for. This tapestried image associated with Thomas Poyntz therefore provides more than an intriguing depiction of Nebuchadnezzar as a feathered man, but also provides an instructional guide to understanding some of the judgements readers must make when reading the biblical narrative of Nebuchadnezzar’s affliction.

Works Cited

Apostolos-Cappadona, Diane. 2020. A Guide to Christian Art. London: T&T Clark/Bloomsbury.10.5040/9780567685155Suche in Google Scholar

Archer, Gleason L.Jr. 1985. “Daniel.” In The Expositor’s Bible Commentary, edited by Frank Gaebelein, 7:3–160. Grand Rapids: Zondervan.Suche in Google Scholar

Astington, John H. 2017. Stage and Picture in the English Renaissance: The Mirror up to Nature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/9781316344095Suche in Google Scholar

Augustinus, Aurelius. 1628. Meditationes, soliloquia et manual. Amsterdam: Johannes Janssonius.Suche in Google Scholar

Atkins, Peter Joshua. 2024. “‘He Differed in Nothing from the Beasts’: The Disruption of the Human-Animal Difference in John Calvin’s Commentary on Daniel 4.” In Exploring Animal Hermeneutics, edited by Arthur Walker-Jones, and Suzanna R. Millar Semeia, 51–66. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature.10.2307/jj.18108261.8Suche in Google Scholar

Atkins, Peter Joshua. 2023. The Animalising Affliction of Nebuchadnezzar in Daniel 4: Reading Across the Human-Animal Boundary. Library of Hebrew Bible/Old Testament Studies 733. London: T&T Clark/Bloomsbury.10.5040/9780567706218Suche in Google Scholar

Bacon, Robert. 1649. The Labyrinth the Kingdom’s In. London.Suche in Google Scholar

Barber, Sarah. 2001. “Belshazzar’s Feast: Regicide, Republicanism and the Metaphor of Balance.” In The Regicides and the Execution of Charles I, edited by Jason Peacey, 94–116. Basingstoke: Palgrave.Suche in Google Scholar

Bodin, Jean. 1580. De la Démonomanie des Sorciers. Paris: Jacques Du Puys.Suche in Google Scholar

Brydges, Samuel Egerton. 1791. The Topographer for the Year 1791. London: J. Robson.Suche in Google Scholar

Campbell, Thomas P. 2007. Henry VIII and the Art of Majesty: Tapestries at the Tudor Court. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Curd, Mary Bryan. 2016. Flemish and Dutch Artists in Early Modern England: Collaboration and Competition, 1460–1680. Visual Culture in Early Modernity. Abingdon: Routledge.10.4324/9781315094069Suche in Google Scholar

Daniell, David. 2003. The Bible in English: Its History and Influence. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Fewell, Danna Nolan. 1991. Circle of Sovereignty: Plotting Politics in the Book of Daniel. Nashville: Abingdon Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Friedman, John Block. 2016. “Dogs in the Identity Formation and Moral Teaching Offered in Some Fifteenth-Century Flemish Manuscript Miniatures.” In Our Dogs, Our Selves: Dogs in Medieval and Early Modern Art, Literature, and Society, edited by Laura D. Gelfand, 325–62. Leiden: Brill.10.1163/9789004328617_016Suche in Google Scholar

Goldingay, John. 2019. Daniel. Rev. ed. Word Biblical Commentary 30. Grand Rapids: Zondervan.Suche in Google Scholar

Greenhill, William. 1839. An Exposition of the Prophet Ezekiel with Useful Observations Thereupon, edited by James Sherman. London: Samuel Holdsworth.Suche in Google Scholar

Hamling, Tara. 2010. Decorating the ‘Godly’ Household: Religious Art in Post-Reformation Britain. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Hefford, Wendy. 2002. “Flemish Tapestry Weavers in England: 1550–1775.” In Flemish Tapestry Weavers Abroad, edited by Guy Delmarcel, 43–61. Leuven: Leuven University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Holm, Tawny L. 2013. Of Courtiers and Kings: The Biblical Daniel Narratives and Ancient Story-Collections. Explorations in Ancient Near Eastern Civilizations 1. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns.10.1515/9781575068695Suche in Google Scholar

House, Paul R. 2018. Daniel: An Introduction and Commentary. Tyndale Old Testament Commentaries 23. London: Inter-Varsity Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Irvin, Benjamin H. 2003. “Tar, Feathers, and the Enemies of American Liberties, 1768–1776.” The New England Quarterly 76: 197–238. https://doi.org/10.2307/1559903.Suche in Google Scholar

Kauffmann, C. M. 2003. Biblical Imagery in Medieval England, 700–1550. London: Harvey Miller.Suche in Google Scholar

Kirkpatrick, Shane. 2005. Competing for Honor: A Social-Scientific Reading of Daniel 1–6. Biblical Interpretation 74. Leiden: Brill.10.1163/9789047407911_005Suche in Google Scholar

M’Kendrick, Scot. 1987. “Edward IV: An English Royal Collector of Netherlandish Tapestry.” The Burlington Magazine 129: 521–4.Suche in Google Scholar

Marillier, Henry Currie. 1930. English Tapestries of the Eighteenth Century: A Handbook to the Post-Mortlake Productions of English Weavers. London: The Medici Society.Suche in Google Scholar

Marinescu, Constantin. 1927. “Notes sur le faste à la cour d’Alfonse V d’Aragon, roi de Naples.” Mélanges d’Histoire Générale à l’Université de Cluif 1: 133–46.Suche in Google Scholar

Miner, Paul. 2010. “Blake’s Design of Nebuchadnezzar.” Blake: An Illustrated Quarterly 44.2: 75–8.Suche in Google Scholar

Newsom Carol A. with Brennan W. Breed. 2014. Daniel: A Commentary. Old Testament Library. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Porteous, Norman W. Daniel: A Commentary. Old Testament Library. London: SCM Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Quidt, Jeremy de. 2012. The Feathered Man. Oxford: David Fickling Books.Suche in Google Scholar

Scott-Moncrieff, David. 1950. “Glamis Castle, Forfar.” Country Life 108: 1408–3.Suche in Google Scholar

Segal, Michael. 2016. Dreams, Riddles, and Visions: Textual, Contextual, and Intertextual Approaches to the Book of Daniel. Berlin: De Gruyter.10.1515/9783110330991Suche in Google Scholar

Suchard, Benjamin D. 2022. Aramaic Daniel: A Textual Reconstruction of Chapters 1–7. Leiden: Brill.10.1163/9789004521308_002Suche in Google Scholar

Tcherikover, Anat. 1986. “The Fall of Nebuchadnezzar in Romanesque Sculpture (Airvault, Moissac, Bourg-Argental, Foussais).” Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 49.3: 288–300. https://doi.org/10.2307/1482358.Suche in Google Scholar

Thomasius, Jacobus, and Fredericus Tobius Moebius. 1667. De Transformatione Hominum in Bruta Dissertationem Philosophicam. Leipzig: Hahnius.Suche in Google Scholar

Thomson, W. G. 1973. A History of Tapestry from the Earliest Times until the Day, 3rd ed. Wakefield: EP Publishing.Suche in Google Scholar

Valeta, David M. 2008. Lions and Ovens and Visions: A Satirical Reading of Daniel 1–6. Hebrew Bible Monographs 12. Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Victor, Verity. 1648. The Royal Prophet: Or, a clear Discovery of His Majesties design in this present Treaty. London.Suche in Google Scholar

Watt, Tessa. 1991. Cheap Print and Popular Piety, 1550–1640. Cambridge Studies in Early Modern British History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Wyld, Helen. 2010. “Nebuchadnezzar Transformed into a Beast: NT 1181084.4.” https://www.nationaltrustcollections.org.uk/object/1181084.4 (accessed June 23, 2023).Suche in Google Scholar

Wyld, Helen. 2013. “Nebuchadnezzar Transformed into a Beast: NT 130090.1.” https://www.nationaltrustcollections.org.uk/object/130090.1 (accessed June 23, 2023).Suche in Google Scholar

Wyld, Helen. 2013. “Seventeenth-Century Tapestries at Ham House.” In Ham House: 400 Years of Collecting and Patronage, edited by Christopher Rowell, 178–93. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Wyld, Helen. 2012. “The Gideon Tapestries at Hardwick Hall.” West 86th 19.2: 231–54. https://doi.org/10.1086/668062.Suche in Google Scholar

Wyld, Helen. 2022. The Art of Tapestry. London: PWP/Bloomsbury.Suche in Google Scholar

Zakula, Tijana, and Elisa Barzotti. “Nebuchadnezzar: VI. Visual Arts.” Encyclopedia of the Bible and its Reception 20: 1182–3.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Snakes on a Page: Visual Receptions of the Eden Serpent through the History of Western Art and Their Survivals in Modern Children’s Bibles

- Jacob’s Nightly Encounter at Peniel and the Status of the Son: Reading Genesis 32 with Athanasius

- Cotton Mather’s Biblical Enlightenment: Critical Interrogations of the Canon and Revisions of the Common Translation in the Biblia Americana (1693–1728)

- Mainstreaming and Defamiliarizing the Rapture: The Leftovers Reads Left Behind

- The Feathered Man: The Reception of Daniel 4 in a 17th-Century English Tapestry of Nebuchadnezzar Transformed into a Beast

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Snakes on a Page: Visual Receptions of the Eden Serpent through the History of Western Art and Their Survivals in Modern Children’s Bibles

- Jacob’s Nightly Encounter at Peniel and the Status of the Son: Reading Genesis 32 with Athanasius

- Cotton Mather’s Biblical Enlightenment: Critical Interrogations of the Canon and Revisions of the Common Translation in the Biblia Americana (1693–1728)

- Mainstreaming and Defamiliarizing the Rapture: The Leftovers Reads Left Behind

- The Feathered Man: The Reception of Daniel 4 in a 17th-Century English Tapestry of Nebuchadnezzar Transformed into a Beast