Abstract

This study explores the potential of nitrogen-enriched lignins produced via ammoxidation – a process combining oxidation and nitrogen incorporation with ammonia (NH3) and oxygen (O2) – to improve wood fibres as sustainable peat alternatives in horticultural substrates. Organocell lignin (OCL) and kraft lignin (KL) were assessed, focusing on the effect of ammoxidation conditions on total nitrogen and amide nitrogen incorporation using OCL as a reference. Total nitrogen content in nitrogen-enriched KL (NKL) reached 6.3 % under 60 bar oxygen pressure, but amide nitrogen remained low (0.64 %), indicating challenges in optimizing this nitrogen type. Attempts to selectively increase amide nitrogen through reaction adjustments proved unfeasible. First cultivation tests showed 2 % nitrogen-enriched OCL (NOCL) enhanced plant growth in substrates with 50 % and 100 % wood fibres compared to lignin-free controls. Adding 10 % NOCL improved growth in peat-free substrates, though less effectively than the 2 % concentration. Conversely, NKL had no notable effect in 50 % wood-fibre substrates and negatively affected 100 % wood-fibre substrates. The results underscore the importance of modifying lignin reactivity prior to ammoxidation to boost amide nitrogen incorporation, offering insights into the viability of wood fibres as peat substitutes in horticulture.

1 Introduction

Peat is formed due to delayed microbiological activity caused by various factors, most notably a low concentration of oxygen, which allows organic residues to accumulate in certain types of ecosystems such as bogs or wetlands (Moore 1989). This means that peatlands are carbon sinks after the accumulation of organic matter at a rate of approximately 1 mm per year (Kern et al. 2017). They cover only 4–5 % of the global land area but they accumulate approximately 20 % of the carbon in the biosphere (Roulet 2000). However, due to the long regeneration time, peat cannot be considered renewable and its extraction causes a rapid decomposition of the organic matter leading to emission of greenhouse gases (Kern et al. 2017). The global carbon dioxide emissions from drained peatlands have been estimated as 1,298 Mton in 2008 (Joosten 2010). In the last 60 years, peat has been the main component of growing media, intended as the material or mixture of materials used to support plant growth by providing essential nutrients, water and aeration to the root system. Its abundance in Northern Europe at competitive price, coupled with its favourable physical, chemical, and biological properties, has solidified its role in horticulture (Schmilewski 2008). However, due to the critical role of peatlands as carbon sinks, their exploitation has become a major environmental concern. In addition, the extraction of peat also poses a significant threat to wetland ecosystems, which are vital habitats for diverse plant and animal species. This has intensified the search for sustainable alternatives that can replace peat in growing media while reducing environmental impact (Gruda 2012, 2021; Schmilewski 2008).

Wood fibres have gained attention as one of such alternatives. These fibres, derived from renewable forestry raw materials, offer favourable properties such as low bulk density and efficient drainage (Agarwal et al. 2023; Atzori et al. 2021; Aurdal et al. 2023; Barrett et al. 2016; Dickson et al. 2022). Over the past three decades, wood fibres have been incorporated into growing media formulations at levels of up to 30 % of the total composition, alongside other components. There is ongoing interest in increasing these substitution levels to further reduce reliance on peat (Gruda 2012, 2021). The main challenge in using wood fibres at higher proportions is the issue of nitrogen immobilization (Jansson and Persson 1982). Given the higher degradability of wood fibres in comparison to peat, nitrogen from the medium is sequestered as the microorganisms grow, reducing its availability for plant growth and potentially leading to deficiencies in nitrogen supply for crops (Vandecasteele et al. 2022). Lignin, a structural component of wood and a by-product of the pulp industry, offers a potential solution to this challenge. Its resistance to microbial degradation could help reduce nitrogen immobilization when added to wood fibre-based substrates (Feofilova and Mysyakina 2016). Furthermore, nitrogen enrichment of lignin may counteract the nitrogen deficiency, by providing nutrient to the medium (Fischer and Schiene 2002; Wurzer et al. 2021).

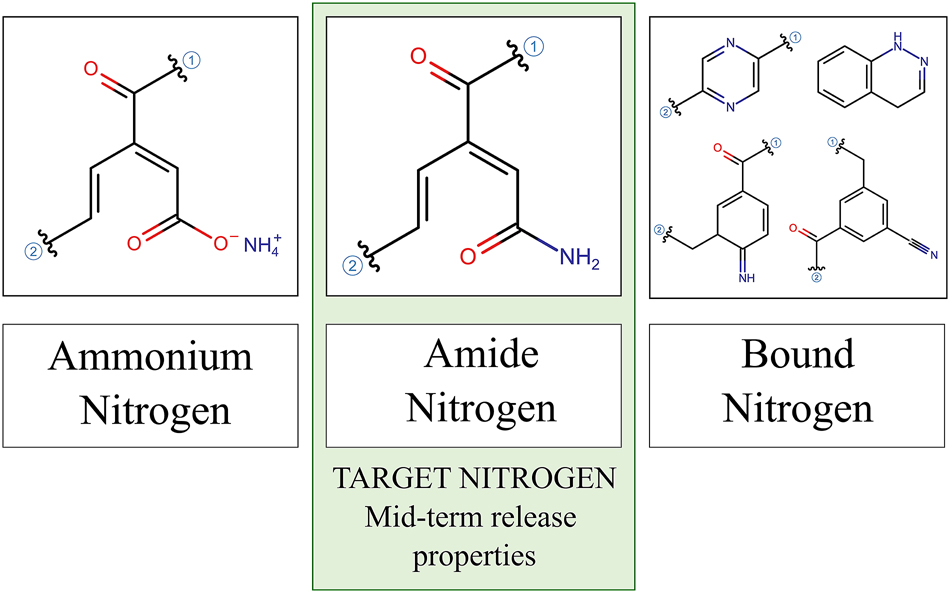

In a previous work, the ammoxidation of lignin was reviewed, which can introduce different nitrogen groups into the lignin structure (Coniglio et al. 2024). Such structures can be classified based on how easily the nitrogen is released into the substrate. Ammonium nitrogen (NH4–N), provides an availability of the nutrient immediately or within a few days after application, whereas amide nitrogen (amide-N) is released over the medium term, typically within weeks or months. In contrast, certain nitrogen structures are strongly bound to lignin, leading to long-term availability, sometimes extending over multiple harvesting cycles. This category includes nitrogen incorporated into heterocyclic aromatic structures. However, previous studies have also shown that under certain conditions, ammoxidation can lead to the formation of other compounds, such as nitriles or imines, which also exhibit limited nitrogen release. Collectively, these compounds can be referred to as bound nitrogen (bound-N), a group of structures that are not readily hydrolysable – meaning they do not significantly contribute to short- or medium-term nitrogen availability for plants (Coniglio et al. 2024).

N-lignins should act as substrate improvers rather than fertilizers for wood fibres in order to effectively prevent nitrogen immobilization and enhance wood fibre proportions as peat substitutes in horticultural substrates. In this context, amide-N must be the target nitrogen, as it provides a controlled nitrogen release over a timeframe appropriate for plant growth (Figure 1).

Groups of nitrogen structures which may get introduced to the lignin structure through ammoxidation. Examples of non-hydrolysable N-structures referred to as bound nitrogen are shown. The target nitrogen group for the production of substrate improvers is highlighted.

In the present study, the potential of ammoxidation to enhance the amide-N content of lignin for its use in substrate improvement was explored. In the first part, the influence of ammoxidation conditions (O2 pressure, temperature and time) using OCL as a reference was evaluated. A statistical analysis was performed and response surfaces for the incorporation of total nitrogen (total-N) and amide-N were obtained. Based on these results, KL, which is commercially available and generates significant scientific interest for valorisation, was ammoxidized. To assess the performance of the nitrogen-enriched lignins (N-lignins) in wood-fibre substrates as peat substitutes, cultivation tests were conducted using 2 % and 10 % N-lignin based on wood fibres in peat and fibre mixtures at 0 %, 50 %, and 100 %.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

Two different lignins were used in this work. On the one hand, an Organosolv lignin (OCL), in this case, a lignin produced by the Organocell process (Bayerische Zellstoff GmbH, Kelheim, Germany) was selected, which was produced by a pulping process with an ethanol-water extraction. The solids content of OCL was 94.1 %. A commercially available kraft lignin (KL) was used, consisting of a purified softwood lignin. It was dried in a circulating-air-drying-oven (Memmert UL 80,Frankfurt, Germany) at 30 °C for 5 days (93.7 % solids content). The nitrogen-enriched lignins are named NOCL for the Organocell and NKL for the kraft lignin, respectively.

Since the cultivation tests for the two lignins were carried out at different stages of the project, two types of wood fibres were used for this work. On the one hand, the fibres used for the cultivation tests using NOCL were produced at the laboratory using pine wood chips (Pinus spp.) supplied by Egger Holzwerkstoffe Wismar GmbH & Co. KG (Wismar, Germany) in a cylindrical horizontal 10 L reactor (Martin Busch und Sohn, Schermbeck, Germany), equipped with four blades reaching over the whole length of the reactor. The material was heated with steam at 140 °C for 5 min. At the end of the steam pre-treatment, the blade system was rotated at 1,455 rpm for 75 s while the reactor was still under pressure to defibrate the softened material. Fibres used for the cultivation tests using NKL were provided by Egger Holzwerkstoffe Wismar GmbH & Co. KG (Wismar, Germany) and were produced by the defibration of a mixture of 80 % spruce (Picea spp.) and 20 % pine (Pinus spp.) chips with a steam digestion time of 5.2 min at 202 °C.

2.2 Raw material characterization

The composition of the lignins was studied in terms of acid-insoluble and acid-soluble lignin, carbohydrates, ashes and ultimate analysis. To determine the carbohydrate composition, the lignins were dried at 60 °C and milled into a fine powder with a mortar. Subsequently, two-step acid hydrolyses were performed in triplicate on 200 mg samples. First, 2 mL of sulfuric acid (72 %, Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH, USA) were used at 30 °C for 60 min. The reaction was stopped by dilution of the sulfuric acid to a concentration of 4 %. The second step of hydrolysis was conducted in an autoclave (120 °C and 0.12 MPa) for 40 min to obtain monomeric sugars. Once cooled, the samples were filtered using a G4 sintered glass crucible and the weight of the acid-insoluble residue was determined. Additionally, the acid soluble lignin content in the filtrate was measured with a UV-Spectrophotometer LAMBDA 650 (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA) at a wavelength of 205 nm. Ash content was determined according to TAPPI T211. Ultimate analysis was performed (Elementar EL cube, Germany) to determine total nitrogen, carbon and sulphur content.

2.3 Ammoxidation

Lignins were ammoxidized in a 1-L autoclave (Autoclave Engineers, USA) using NH4OH (30–33 % NH3 in H2O) under O2 atmosphere. Lignin was added directly to the reactor followed by 50 mL of NH4OH solution and 550 mL of deionised water. The autoclave was sealed and O2 was injected up to the reaction pressure. The reactants were stirred continuously and the temperature was controlled with an on-off controller which allowed to maintain the temperature in a range of ±5 K. When the time was reached the heater was turned off and the reactor cooled using a coil with a chiller (Julabo F25, Germany) with propylene glycol and water (1:1). Once the reactor reached room temperature, it was slowly depressurized. The products solution was removed with a pipette and left to evaporate overnight in a crystallizer under a fume hood to remove the remaining NH3. The remaining aqueous solution was stored in an amber-colour flask until needed. For the chemical analysis the lignin was dried at 60 °C for 24 h and then milled using a mortar.

2.4 Experimental design

An experimental design was created to evaluate how temperature, time and O2 pressure affect the total-N incorporation as well as NH4–N and amide-N content during the ammoxidation of the reference lignin OCL. The design was based on a three-factor and three level Box-Behnken design (according to an incomplete factorial design, 33) for fitting response surfaces, as it is efficient for an exploratory analysis in terms of the numbers of experiments required. The independent variables used were temperature (x1) with levels of 120 °C, 150 °C and 180 °C; O2 pressure (x2) with levels of 10 bar, 20 bar and 30 bar; and time (x3) with levels of 30 min, 60 min and 90 min (Table 1). The dependent variables studied were total-N content and amide-N. The set of experiments consisted of 12 runs and three replicates of the central point (Table 3).

Experimental design in the original and coded form of the independent variables.

| Coded level | Temperature (°C) x1 | O2 pressure (bar) x2 | Time (min) x3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| −1 | 120 | 10 | 30 |

| 0 | 150 | 20 | 60 |

| 1 | 180 | 30 | 90 |

Chemical characterization of the technical lignins used: organocell lignin (OCL) and kraft lignin (KL).

| Component (wt% dry basis) | OCL | KL |

|---|---|---|

| Acid insoluble lignin | 92.5 | 93.2 |

| Acid soluble lignin | 4.7 | 5.7 |

| Carbohydrates | 1.4 | 1.1 |

| Glucose | 0.1 | 0.19 |

| Xylose | 0.5 | 0.33 |

| Mannose | 0.2 | 0.04 |

| Galactose | 0.3 | 0.46 |

| Arabinose | 0.3 | 0.09 |

| Ash | 3.1 | 1.1 |

| Elementary composition | ||

| C | 68.7 | 65.2 |

| N | 0.5 | 0.2 |

| S | 0 | 1.6 |

Box Behnken design and results for the evaluation of the effect of ammoxidation conditions on the nitrogen incorporation for the reference lignin.

| Exp | Temperature (°C) | O2 pressure (bar) | Time (min) | Total-N content (wt% dry basis) | NH4–N content (wt% dry basis) | Amide-N content (wt% dry basis) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 120 | 10 | 60 | 2.1 | 0.8 | 0.5 |

| 2 | 120 | 20 | 30 | 1.9 | 0.8 | 0.2 |

| 3 | 120 | 20 | 90 | 2.5 | 1.0 | 0.4 |

| 4 | 120 | 30 | 60 | 2.5 | 1.00 | 0.3 |

| 5 | 150 | 10 | 30 | 1.7 | 1.0 | 0.1 |

| 6 | 150 | 10 | 90 | 2.3 | 0.6 | 0.5 |

| 7 | 150 | 30 | 30 | 2.6 | 0.9 | 0.4 |

| 8 | 150 | 30 | 90 | 3.1 | 0.7 | 0.8 |

| 9 | 180 | 10 | 60 | 2.0 | 0.7 | 0.3 |

| 10 | 180 | 20 | 30 | 2.1 | 0.7 | 0.3 |

| 11 | 180 | 20 | 90 | 2.5 | 0.7 | 0.5 |

| 12 | 180 | 30 | 60 | 2.8 | 0.8 | 0.4 |

| 13 | 150 | 20 | 60 | 2.4 | 1.0 | 0.2 |

| 14 | 150 | 20 | 60 | 2.2 | 0.7 | 0.3 |

| 15 | 150 | 20 | 60 | 2.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 |

The influence of the independent variables was studied by statistical analysis through an ANOVA variance analysis, setting a confidence level of 95 %. The study was performed using StatSoft, data analysis software system (Inc. Statistica version 13) and response surfaces for the dependent variables were constructed to visualize the effects of the independent variables.

2.5 Nitrogen analysis

NH4–N and amide-N contents were determined using a modified Kjeldahl method with a Parnas Wagner device. First, lignin samples were hydrolysed with MgO, and the released NH3 was steam-distilled, collected in 0.1 M HCl, and titrated with 0.1 M NaOH to determine NH4–N content. Similarly, another lignin sample was hydrolysed with 33 % NaOH, and the released NH3 was steam-distilled, collected in 0.1 M HCl, and titrated with 0.1 M NaOH to determine the combined NH4–N and amide-N content. Total-N was determined by ultimate analysis (Elementar EL cube, Langenselbold, Germany). The bound-N content, representing nitrogen incorporated into non-hydrolysable structures, was calculated as the difference between Total-N and the sum of NH4–N and amide-N.

2.6 FTIR analysis

FTIR spectra were obtained for the ammoxidized lignins using a Bruker Invenio-S spectrometer (Massachusetts, USA) equipped with attenuated total reflection (ATR) (2 mm) diamond. The spectra acquisition involved 64 scans with a spectral resolution of 4 cm−1 in the range of 4,000–400 cm−1. Before each sample was analysed, the background spectrum was collected, to subtract any unwanted residual peaks from the sample spectrum.

2.7 Plant performance evaluation

To evaluate the performance of N-lignins as substrate improvers, mixes of wood fibres with 2 % and 10 % proportions of N-lignin were prepared. Substrates of 100 % wood fibres and 50 % wood fibres mixed with white peat were tested. Cultivation tests of Chinese cabbage were performed following the DIN EN 16086-1 method. For each condition tested, three pots were evaluated as replicates, with 20 seeds per pot. To assess any potential growth-inhibiting effects from the addition of each N-lignin, a negative control experiment was conducted by adding 2 % and 10 % N-lignin to white peat. Additionally, a peat control was established using white peat without N-lignin, following the same experimental setup (3 pots, 20 seeds per pot). After 4 weeks, the dry mass of the plants in each pot was measured. Growth performance was assessed visually and by comparing the dry mass of plants in the test substrates to the reference control. Growth performance was assessed both visually and by comparing the dry mass to the control. In all cases, the substrates were fully fertilized according to the specified method. Considering all the conditions and the two N-lignins, a total of 57 pots were used in the experiments.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Raw material characterization

OCL was chosen to be used as a reference lignin because of its similar structure to native lignin (Kai et al. 2016; Lora and Glasser 2002). Furthermore, it is sulphur free and its reactivity is normally higher than other technical lignins (Lindner and Wegener 1988). On the other hand, KL was selected as it is the most abundant by-product of the pulping industry and therefore it is commercially available at large scale (Gellerstedt 2015). However, the reactivity is lower, mainly due to the presence of a more condensed structure resulting from the pulping process and the subsequent precipitation (Fabbri et al. 2023). The results of the characterization of the two lignins are presented in Table 2. As expected, the materials show a high proportion of acid insoluble lignin given the fact that both raw materials used are purified lignins. The carbohydrate content is low, which benefits the objectives of this work. Studies report that phytotoxic compounds can be formed from carbohydrates even under mild ammoxidation conditions (Klinger et al. 2013a,b). At higher temperatures, the formation of inhibitory compounds significantly increases, severely hindering growth. This is also relevant for the use of impurified pulping liquors as raw materials. From the ultimate analysis it can be observed that the nitrogen content of the raw materials is minor, which means that the C/N ratios for OCL and KL are 160 and 380 respectively. It is reported that a material should have C/N ratios lower than 20 to be able to work as good fertilizers or soil improvers (Fischer and Schiene 2002; Lapierre et al. 1994). These results are consistent to other values reported previously reviewed (Coniglio et al. 2024) and explain the need to enrich the lignins with nitrogen compounds. Regarding sulphur content, KL has a relatively low concentration of sulphur, which is beneficial since high content in ammoxidized lignins has been reported to negatively affect plant growth (Ngiba et al. 2022; Tyhoda 2008).

3.2 Ammoxidation of reference lignin

The effect of ammoxidation conditions, temperature, O2 pressure and time, on total-N content, NH4–N content and amide-N content for the reference lignin, OCL, was studied. The experimental conditions and results are shown in Table 3.

The influence of the independent variables can be studied from the statistical factors obtained through the ANOVA analysis (Table 4) as well as from the response surfaces for the dependent variables (Figures 2 and 3).

ANOVA results for total-N and amide-N, displaying the F-values and corresponding p-values for each independent variable (pressure, temperature, and time).

| Total-N (wt% on dry basis), R2 = 0.893; R2adj = 0.812 | ||

|---|---|---|

| F | p | |

| Temperature | 0.825 | 0.47220 |

| Pressure | 20.843 | 0.00067 |

| Time | 11.592 | 0.00433 |

|

|

||

| Amide-N (wt% On dry basis), R 2 = 0.495; R 2 adj = 0.117 | ||

|

|

||

| Temperature | 0.286 | 0.759 |

| Pressure | 0.677 | 0.535 |

| Time | 2.933 | 0.111 |

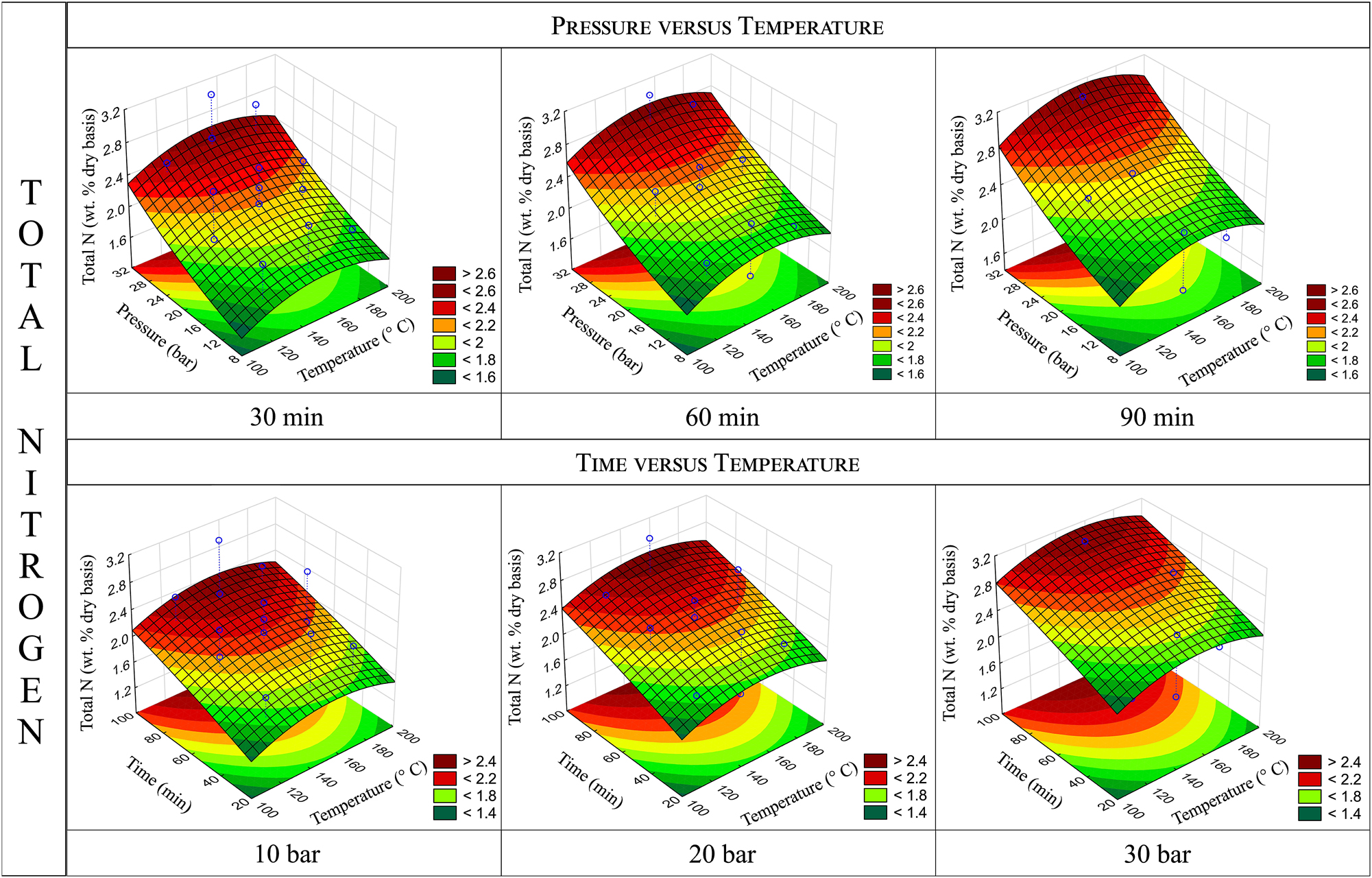

Response surfaces for total-N content obtained by varying pressure and temperature holding time constant (top) and by varying time and temperature holding pressure constant (bottom).

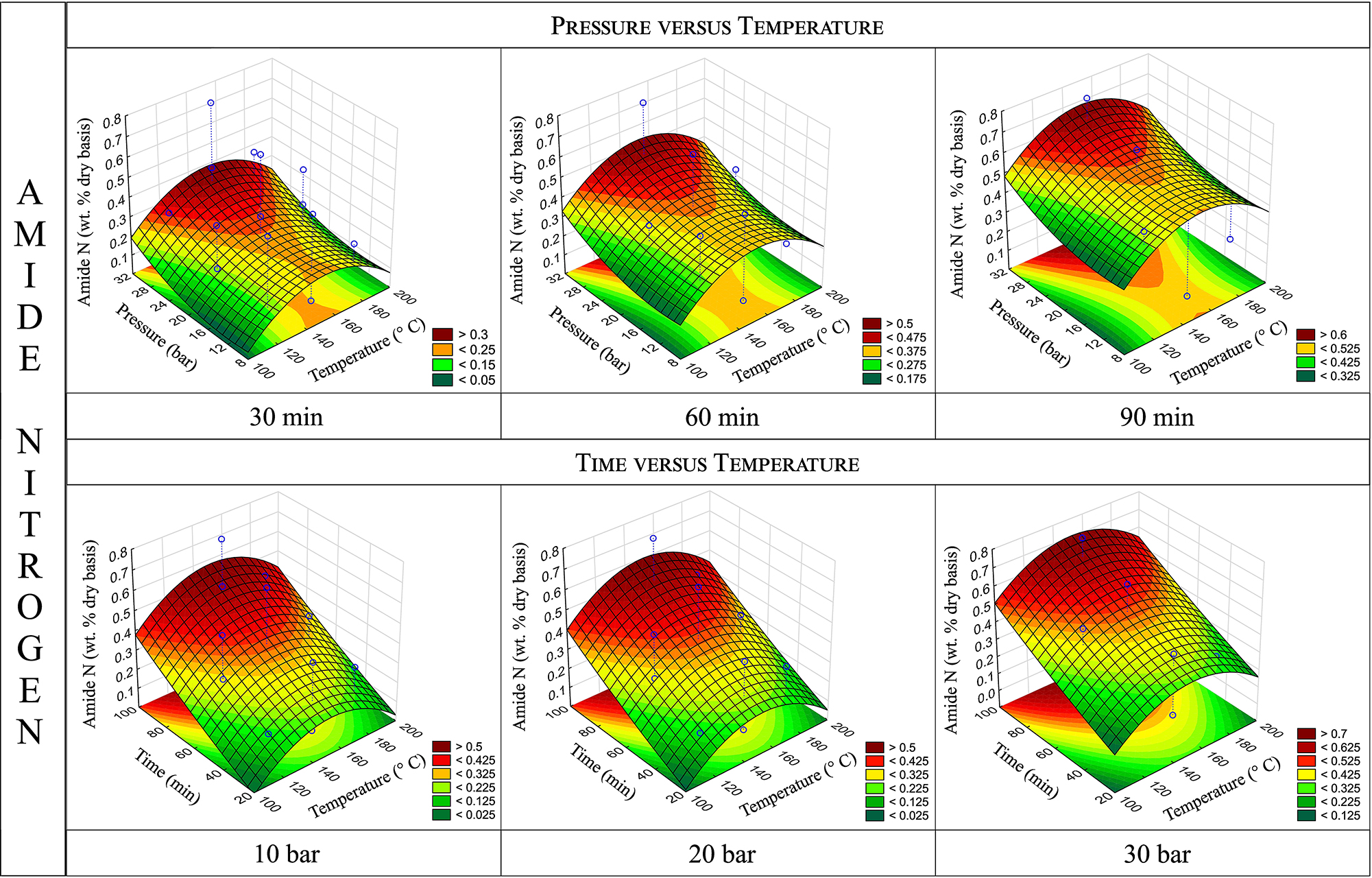

Response surfaces for amide-N content obtained by varying pressure and temperature holding time constant (top) and by varying time and temperature holding pressure constant (bottom).

Several insights can be derived from the ANOVA analysis. The significance level (p-value) serves as a key indicator of whether the observed effects are statistically significant. Specifically, a p-value below 0.05 at a 95 % confidence level indicates that the independent variable in question has a statistically significant impact on the dependent variable (Montgomery 2017). Additionally, analysing the F-value provides information about the magnitude of the effect. When comparing two independent variables, a higher F-value for one suggests that it has a more pronounced influence on the variation observed in the dependent variable (Field 2018; Montgomery 2017).

However, to accurately evaluate the quality of the model, it is crucial to consider both the coefficient of determination (R2) and the adjusted coefficient (R2adj). R2 measures the proportion of the total variance in the dependent variable that is explained by the model. While it provides an initial indication of the model fit, its reliability diminishes as more independent variables are added to the model, as it does not account for the potential overfitting that may arise from increasing model complexity. In contrast, R2adj modifies the R2 value by factoring in the number of independent variables and the sample size. This adjustment offers a more realistic assessment of the model’s explanatory power, particularly in cases where the model includes multiple predictors (Draper and Smith 2014; Hair et al. 2010). When R2adj is close to R2, it suggests that the additional variables included in the model contribute meaningfully to explaining the variance and enhance the model’s fit. In Table 4, this can be observed for the model predicting total-N, where R2 = 0.893 and R2adj = 0.812. The small difference indicates that the multiple variables introduced have only a minor effect on the regression, underscoring a robust overall fit. This reliable fit justifies drawing meaningful conclusions from the ANOVA analysis for total-N.

The model for amide-N (Table 4) shows a much lower R2 (0.495), indicating that only 49.5 % of the variance in amide-N is explained by the independent variables: pressure, temperature and time. The large discrepancy between R2 and R2adj highlights substantial data variability, which reduces the model’s explanatory capacity (Hair et al. 2010). Furthermore, the model considers only linear and quadratic terms, potentially overlooking higher-order interactions that could play a critical role in explaining amide-N variability (Montgomery 2017). It is also possible that other variables not included in this study, such as solid-liquid ratio or NH3 concentration, influence amide-N formation.

Regarding the effect on amide-N incorporation, the ANOVA analysis (Table 4) reveals that none of the independent variables has a statistically significant effect, as the p-values for all three variables exceed 0.5. This aligns with the challenges previously discussed regarding the model’s fit for amide-N, as evidenced by the low R2adj and its considerable difference from R2. Nevertheless, a comparison of the F-values for the variables suggests that reaction time has a slightly greater influence than pressure.

Figure 2 illustrates the response surfaces generated for the total-N content when two parameters are varied while keeping the third constant. From the pressure versus temperature surfaces, it can be observed that there is no optimal value for working pressure; instead, an increase in oxygen pressure consistently leads to higher total-N content. This aligns with the p-value obtained for pressure (p = 0.00067), indicating that pressure has a significant effect on total-N incorporation. These findings are consistent with previous studies. For instance, Capanema et al. (2001b) found that oxygen pressure affects both the rate of nitrogen incorporation and the rate of lignin solubilization.

The p-value obtained for time (p = 0.00433) reveals that this parameter also has a relevant effect, which is evident from the pressure versus temperature surfaces, as they rise towards higher nitrogen contents as the reaction time progresses from 30 to 60 and 90 min. However, time exerts a less pronounced effect compared to pressure. The ANOVA analysis confirms this, as the F-value for pressure (F = 20.843) is nearly double that for time (F = 11.592). Additionally, when observing the time versus temperature response surfaces, the trends are much flatter, indicating that the increase in nitrogen content with longer reaction times is more gradual. Furthermore, the time versus temperature surfaces display a steeper increase in nitrogen content as oxygen pressure rises from 10 to 30 bar, a more pronounced trend compared to the pressure versus temperature surfaces.

For temperature, the effect on the dependent variable is not statistically significant. This is evident from the p-value obtained for this parameter (p = 0.47220, greater than 0.05), indicating no meaningful influence of temperature on total-N incorporation. On the response surfaces, while slightly higher nitrogen values are observed near the central temperature point for a given pressure or time, the variation is minimal. The other variables, particularly pressure, are the primary drivers. Consequently, pressure versus time surfaces are nearly identical across the three temperature levels and are therefore not shown in this article. This lack of effect can be attributed to the selected temperature range being sufficient to facilitate the necessary reactions for nitrogen incorporation, making the reaction rates primarily dependent on O2 pressure and time. These findings are consistent with previous research showing that activation energies for nitrogen incorporation are relatively low (Capanema et al. 2001a, 2002). Indeed, it has been reported that approximately 20–25 % of the maximum nitrogen content is rapidly incorporated as long as oxygen is present, indicating that nitrogen incorporation is mainly a function of oxygen partial pressure. Moreover, studies have demonstrated that the mechanisms of lignin ammoxidation remain consistent within the 70–130 °C range. The results of this work suggest that this effect may extend to higher temperatures, within the range of 120–180 °C.

Figure 3 illustrates the response surfaces generated for amide-N content, showing the effect of varying two parameters while keeping the third constant. The pressure versus temperature surfaces indicate that the increase in amide-N with rising pressure is gradual, resulting in a gently sloped curve. Additionally, a slight increase of the surfaces toward higher amide-N contents can be observed, when the reaction time increases from 30 min to 60 min and then to 90 min. Although a similar trend is observed for the time versus temperature surfaces as pressure increases, the change is less pronounced.

These findings are consistent with previous research. Capanema et al. (2001b) reported that oxygen pressure affects the kinetics of nitrogen incorporation but does not significantly affect the reaction mechanisms during lignin ammoxidation, suggesting that the formation of specific compounds is not significantly influenced by oxygen. This is reflected in the results of the present work, which show that higher pressures and longer reaction times result in lignins with increased amide-N but also higher levels of undesirable bound-N, limiting their suitability for the intended application as substrate improvers. While this study explored higher pressure ranges up to 30 bar compared to Capanema et al. (2001b), who investigated 5–12 bar, the results indicate that increasing the reaction rate does not enable selective enhancement of amide-N over bound-N.

The effect of temperature on amide-N, as with total-N, is marginal. While the shape of the temperature response curve might suggest that amide-N content peaks near the central temperature point, variations across the temperature range are minimal. Capanema et al. (2002) noted that temperature could influence the ratio of reaction pathways but with only minor effects. Consistent with this, the results of this work do not show any significant differences in the ratio of total-N to amide-N. However, the inherent variability of the amide-N data may limit the robustness of this observation.

It is important to note that, across all cases, the amide-N content remains very low. A maximum content of 0.75 % was achieved under conditions of 150 °C, 90 min, and 30 bar (Experiment 8, Table 3). The differences for the amide incorporation between the different conditions are low, which may explain why none of the variables has a statistically significant effect.

3.3 N-lignin production for cultivation tests

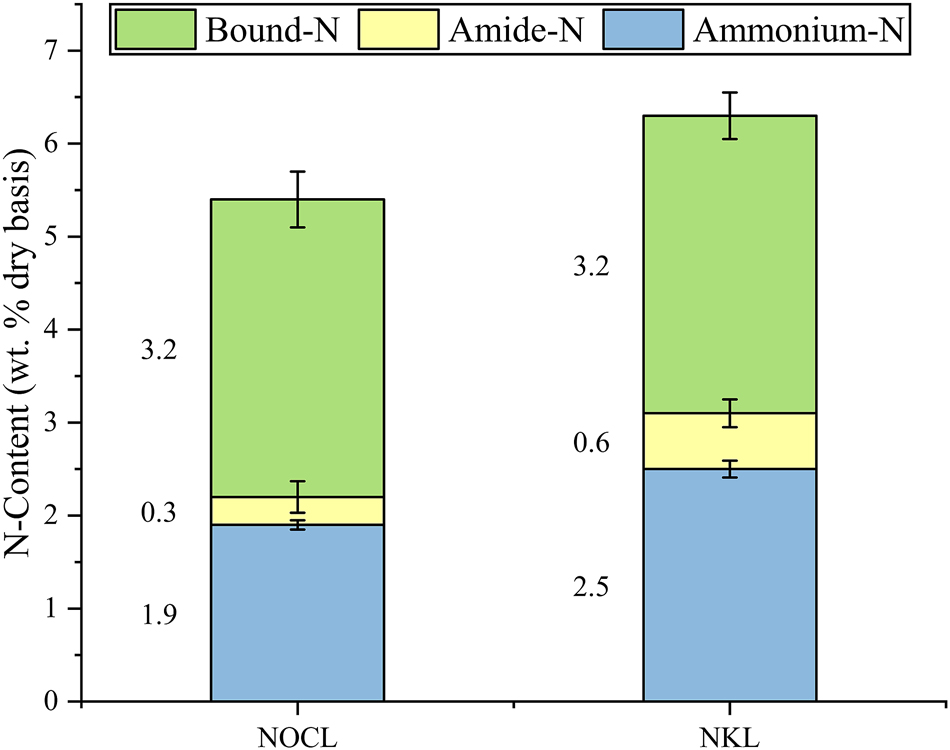

Considering the results of the experimental design for the reference lignin OCL, both OCL and KL lignins were ammoxidized using the longest reaction time (90 min). Given that pressure was identified as the most influential factor for total-N incorporation, the O2 pressure was significantly increased to 60 bar, aiming to achieve higher nitrogen incorporation while maintaining a comparable ratio between total-N and amide-N to those observed in the initial experiments, and thus to obtain a higher absolute amide-N content. The temperature, which was shown to have no statistically significant effect, was maintained at the central value of 150 °C. Three runs were performed for each lignin, and the total-N, NH4–N, and amide-N contents were determined. The results are presented in Figure 4.

Contents for the ammonium-N (NH4), amide-N and bound-N fraction of the ammoxidated lignins for cultivation tests (NOCL: ammoxidated Organocell lignin; NKL: ammoxidated kraft lignin).

As expected, the elevated oxygen pressure resulted in a higher total-N incorporation, reaching a total-N content of 5.4 wt% for the NOCL, compared to the maximum of 3.1 wt% observed at 30 bar under the same temperature and reaction time conditions (Table 3). Similarly, NKL exhibited a higher nitrogen incorporation, achieving 6.3 wt%. However, the proportion of amide-N in both lignins remained notably low: 0.30 wt% for NOCL and 0.64 wt% for NKL.

Interestingly, increasing the pressure not only enhanced total-N incorporation but also significantly reduced the amide-N to total-N ratio. For OCL, the experiment with the highest amide-N content (Exp. 8–30 bar) achieved an amide-N to total-N ratio of 0.24, whereas at an oxygen pressure of 60 bar, this ratio dropped to 0.06. Contrary to the trends observed in the experimental design for OCL, the elevated pressure under these conditions did not improve the amide-N content. Instead, the results suggest that working at pressures significantly beyond the experimental range of 30 bar may influence the reaction mechanisms themselves, rather than just the reaction rates. One plausible explanation for the reduced amide-N proportion is, that higher pressures may have promoted pathways leading to the formation of heterocyclic nitrogen compounds derived from amide degradation.

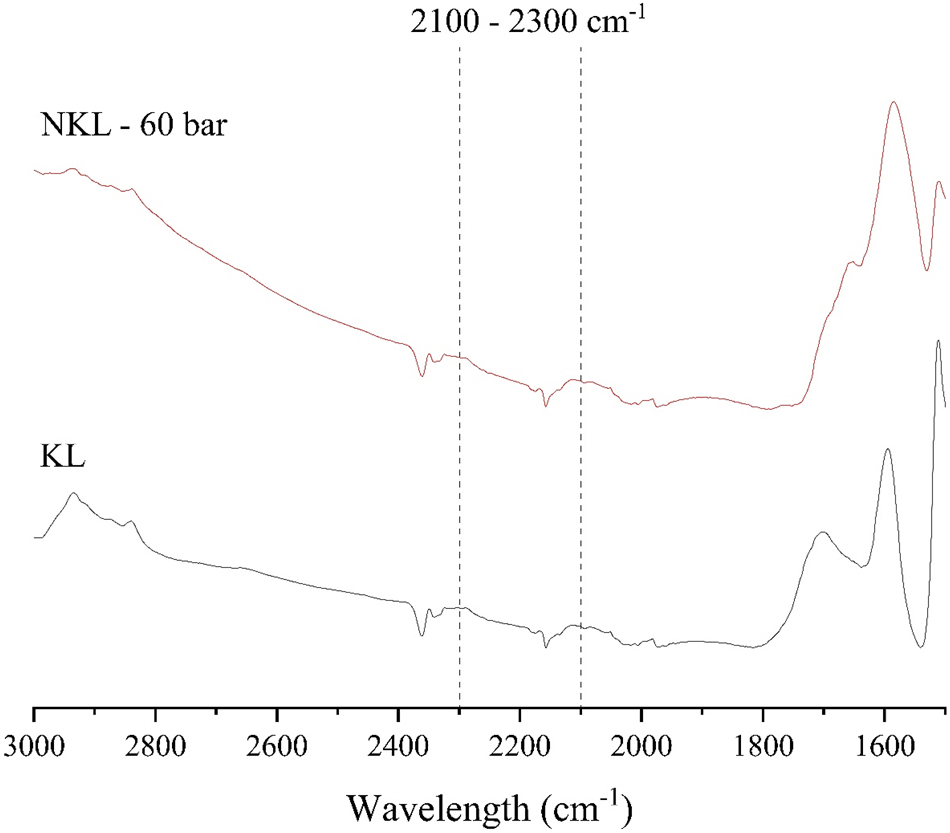

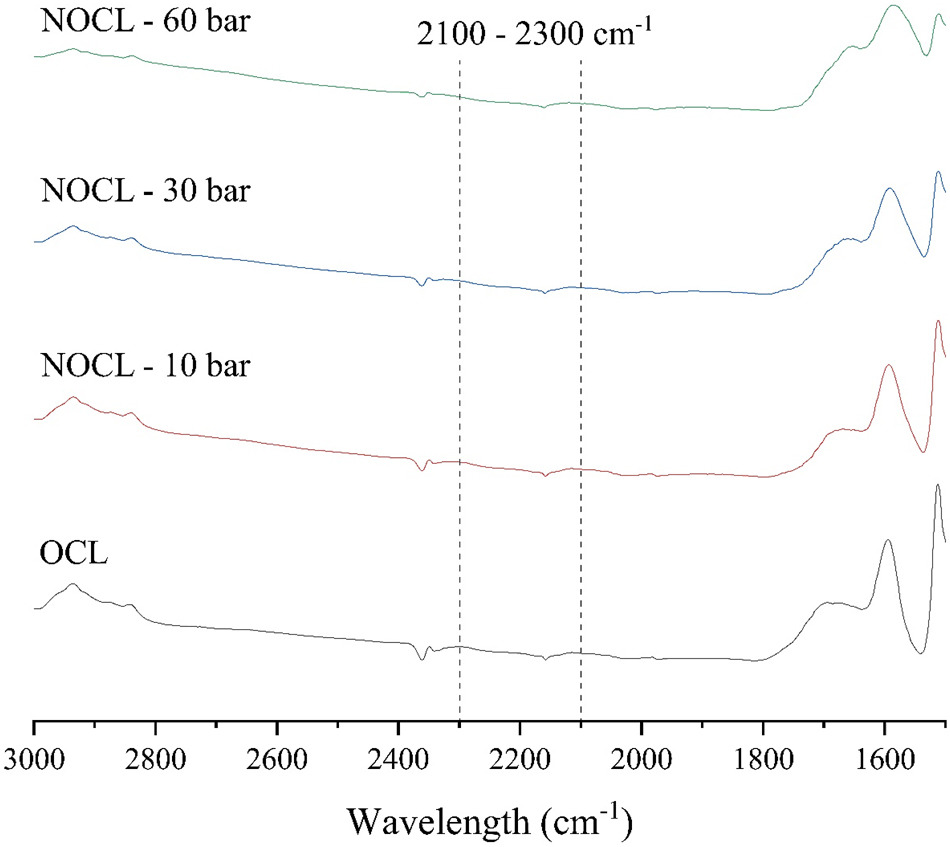

Another possible explanation could be the formation of nitriles due to the increased pressure applied during lignin production. In fact, it has been reported that ammoxidation under particularly severe conditions can lead to nitrile formation (Coniglio et al. 2024). However, their detection via Py-GC/MS may be inconclusive due to the degradation of amides under pyrolytic conditions (Tyhoda 2008). The presence of nitriles can be investigated using FTIR, as this functional group typically exhibits a sharp absorption band in the range of 2,260–2,200 cm−1 (Socrates 2001). In fact, Potthast et al. (1996) confirmed their presence in ammoxidized lignins through the detection of a low-intensity band at 2,200 cm−1. To further examine this phenomenon, the starting lignins (KL and OCL) as well as the lignins produced for the cultivation trials (NKL and NOCL) were analyzed using FTIR. Additionally, for the Organocell lignins, spectra were recorded for an ammoxidized lignin at 10 bar (Exp. 5 in Table 3) and at 30 bar (Exp. 8 in Table 3) to compare with the ammoxidation at 60 bar. The selected spectral region relevant for nitrile detection is presented in Figures 5 and 6.

Section of the FTIR spectra (baseline corrected) for kraft lignin (KL) and for the ammoxidated kraft lignin (NKL) for the cultivation tests. The wavelength range corresponding to the presence of nitriles is highlighted.

Section of the FTIR spectra (baseline corrected) for Organocell lignin (OCL) and for ammoxidated Organocell lignins (NOCL) at 10 bar, 30 bar and 60 bar. The wavelength range corresponding to the presence of nitriles is highlighted.

For kraft lignin, the ammoxidation performed for the cultivation trials did not result in the formation of nitriles within the lignin structure, as no absorptions were observed in the corresponding spectral range (Figure 5). In fact, within the whole 2,300–2,100 cm−1 range, no noticeable differences were detected in the NKL spectrum compared to the starting lignin, ruling out any potential band overlapping. Similarly, for Organocell lignin, an increase in ammoxidation pressure from 10 bar to 30 bar and then to 60 bar did not lead to nitrile formation. Therefore, the formation of these compounds due to increased pressure, as a potential explanation for the higher proportion of non-hydrolysable nitrogen in the lignins produced for the cultivation trials, is not supported by the data.

However, the structural changes in lignins due to ammoxidation require further investigation and should be addressed in future studies. It is evident that selectively enriching lignin with amide-N while minimizing the formation of bound-N under simultaneous oxidation and ammonolysis conditions remains a challenge. Future efforts should focus on alternative strategies to increase the proportion of amide-N, including structural modifications of the lignin prior to ammoxidation. Enhancing lignin reactivity through preactivation has been widely recognized as a critical step in lignin valorisation (Kai et al. 2016; Laurichesse and Avérous 2014; Rinaldi et al. 2016). Potential approaches to activate lignin prior to the reaction with ammonia include increasing the hydroxyl groups content (Harth et al. 2023; Pandey and Kim 2011), carboxylation to raise carboxylic acid levels (Andriani and Lawoko 2024), or pre-oxidation using hydrogen peroxide (Ngiba et al. 2022; Qi-Pei et al. 2006).

3.4 Effect of NOCL on plant growth

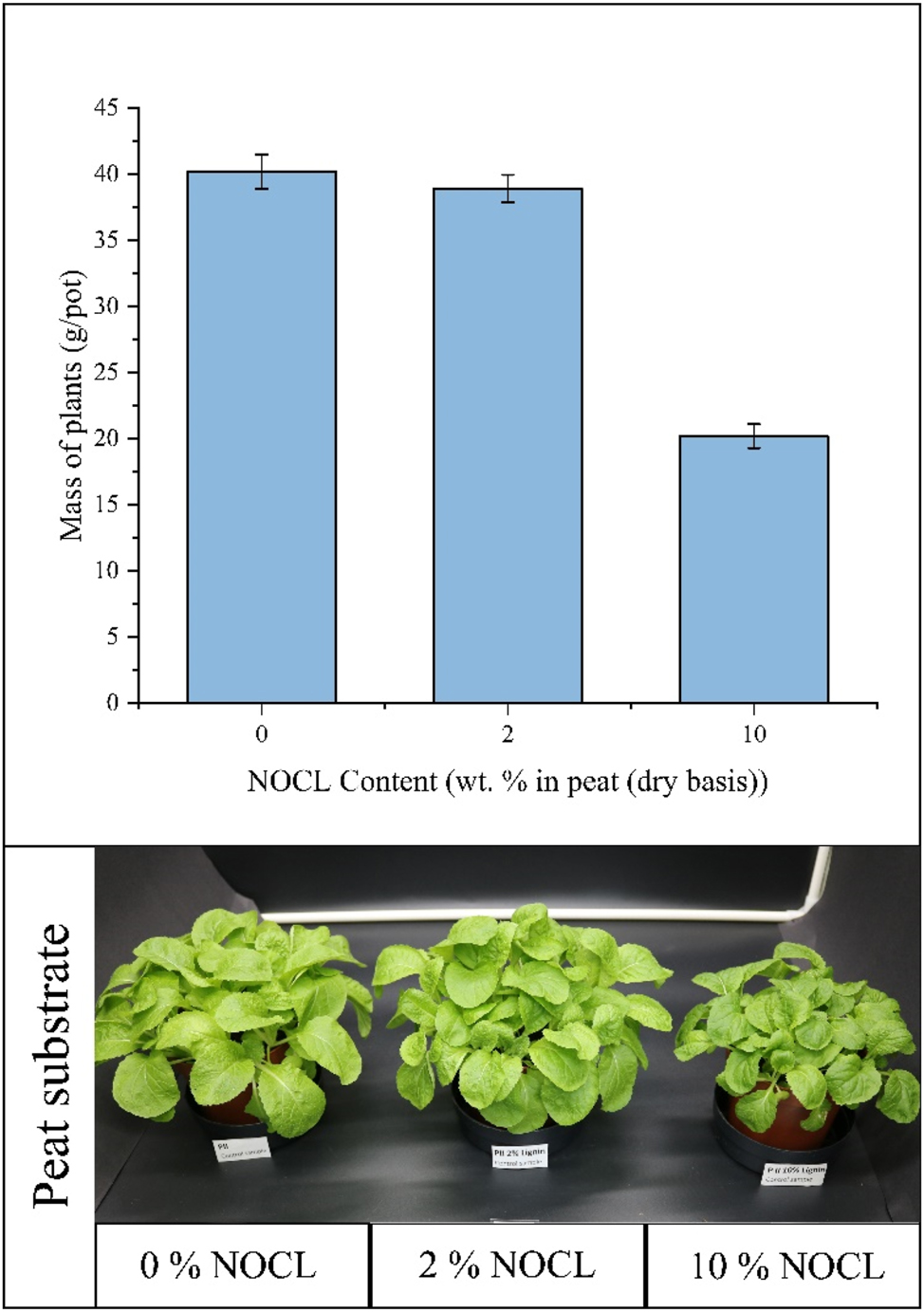

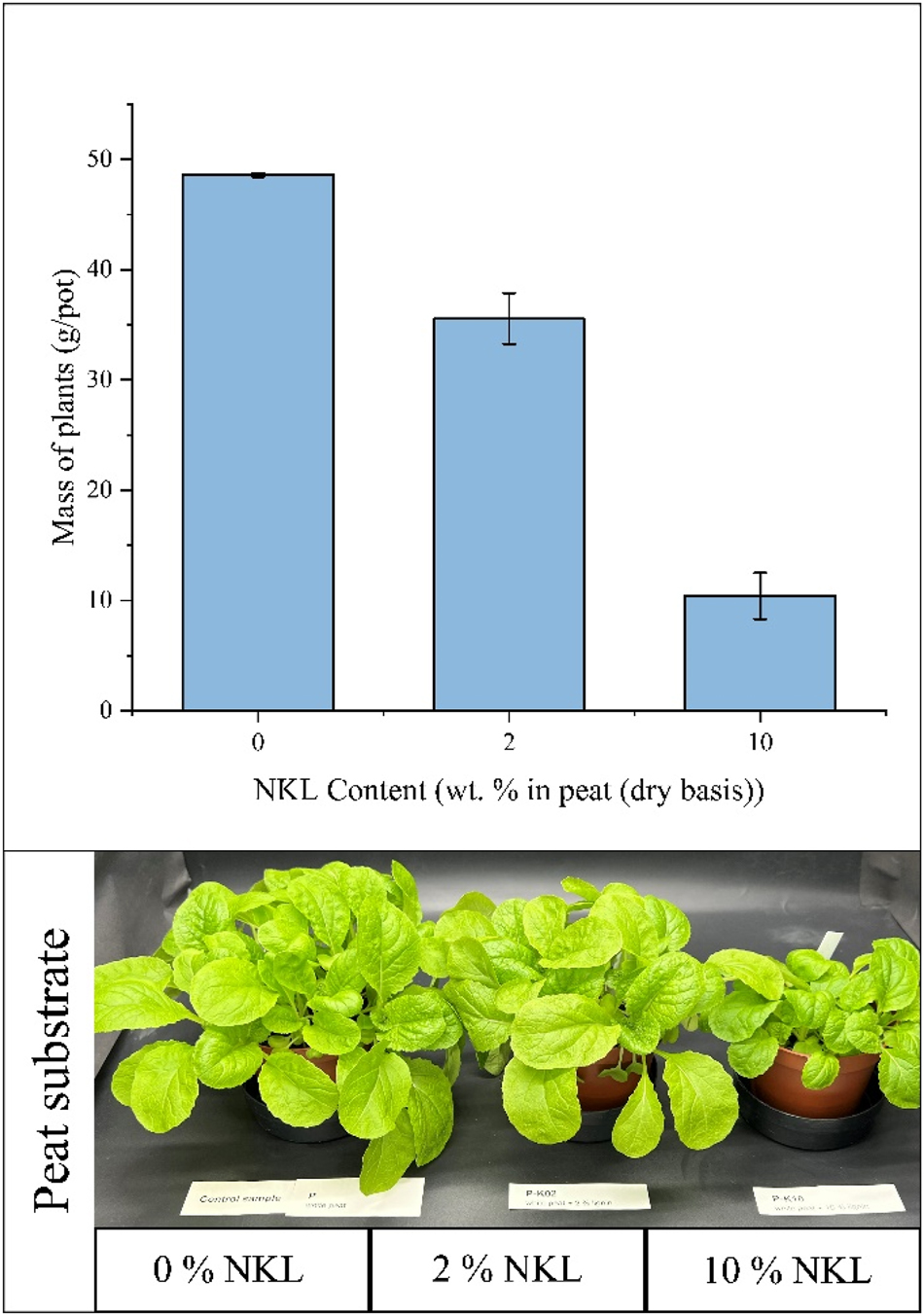

The performance of NOCL as a substrate improver was assessed through a 4-week cultivation test using Chinese cabbage. Figure 7 presents the first results of the negative control test, designed to evaluate any potential growth-inhibiting effects of NOCL. The results indicate that adding 2 % NOCL to peat did not adversely affect plant growth. This conclusion is supported by plant dry mass data, and visual comparison of the plants. However, a negative impact on growth was observed when the NOCL concentration was increased to 10 %. This was reflected in reduced plant mass and visibly lower growth compared to the control. Considering the possible variability associated to plant growth, these results should be confirmed with further tests increasing the number of pots.

Results of the negative control test for NOCL (ammoxidated Organocell lignin) – Chinese cabbage plants after 4 weeks cultivated in peat with NOCL.

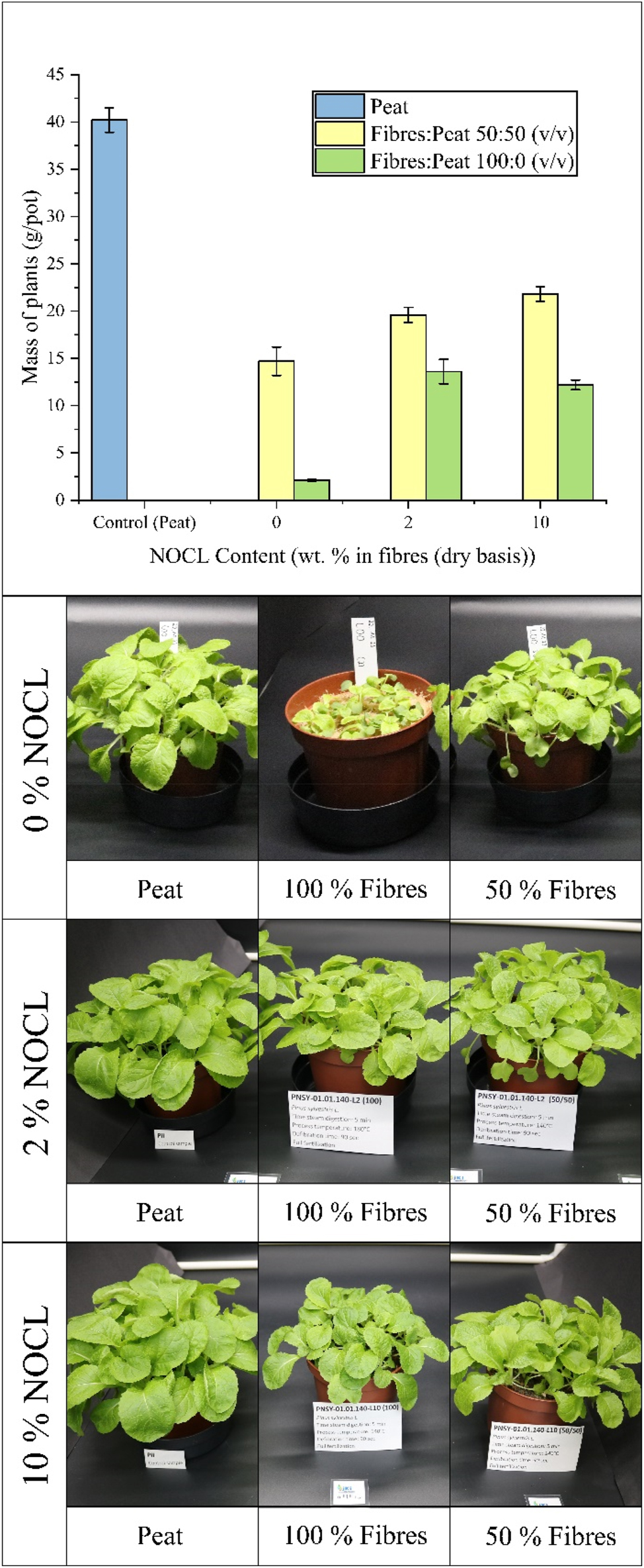

The performance of NOCL was tested in substrates composed of a 50 % mixture of wood fibres and peat, as well as in 100 % fibre-based substrates, with peat as control. Figure 8 presents the results of this assessment. For the 100 % fibre substrate, the addition of 2 % NOCL had a positive effect on plant growth. In the absence of lignin, a visual observation of the plants shows poor growth, with small, discoloured leaves. A possible explanation of this is a potential nutrient deficiency, which may be caused by nitrogen immobilization. However, even if the tests were performed according to a standardised method (DIN EN 16086-1), future tests with a higher number of pots may be needed to confirm these results. By contrast, the addition of 2 % NOCL improved growth, increasing plant mass from 2.1 gplants/pot to 13.6 gplants/pot. Increasing the NOCL concentration to 10 % did not result in further improvements. While plant growth was not substantially worse than in the 2 % NOCL treatment, a slight decline was observed. This may be attributed to the growth-inhibiting effects of lignin at higher concentrations, as previously noted in the negative control experiment with peat.

Results of the plant growth of Chinese cabbage test for mixes of wood fibres and peat with 0 %, 2 % and 10 % of NOCL (ammoxidated Organocell lignin).

First results for substrates composed of 50 % wood fibres and 50 % peat, the addition of NOCL consistently enhanced plant growth. In the substrate containing 2 % NOCL, there was a 33 % increase in plant mass per pot compared to the sample without NOCL. The substrate with 10 % NOCL still showed an increase. It is important to note that the N-lignin was added relative to the wood fibre component. Thus, 10 % N-lignin relative to the fibres translates to 5 % N-lignin in the overall 50 % fibre–peat substrate mixture. This dilution effect could explain why, in the negative control experiment, the addition of 10 % N-lignin showed a growth-inhibiting effect, whereas the 10 % NOCL relative to the fibres in the 50 % substrate mixture resulted in a positive impact on plant growth.

Nevertheless, it is evident that the performance of all fibre–peat substrates was clearly inferior to that of the 100 % peat control. This outcome is not unexpected, given the well-established superiority of peat as a horticultural substrate. It is crucial to emphasize, as outlined in this study’s objectives, that the goal of N-lignin is to function as a substrate improver. Striving to fully replicate the properties of peat may be a dead-end approach. However, these first results with plant cultivation tests indicate that the use of NOCL can enhance the performance of wood fibres as a horticultural substrate. Further research is needed to continue improving the performance of fibre-based substrates.

3.5 Effect of NKL on plant growth

In a similar way to the tests performed with NOCL, a negative control experiment was conducted using peat with 2 % and 10 % NKL added, and its performance was compared to the peat control without N-lignin. These first results indicate that, unlike NOCL, NKL has a negative effect on plant growth, even at concentrations as low as 2 % (Figure 9).

Results of the negative control test for NKL (ammoxidated kraft lignin) – Chinese cabbage plants after 4 weeks cultivated in peat with NKL.

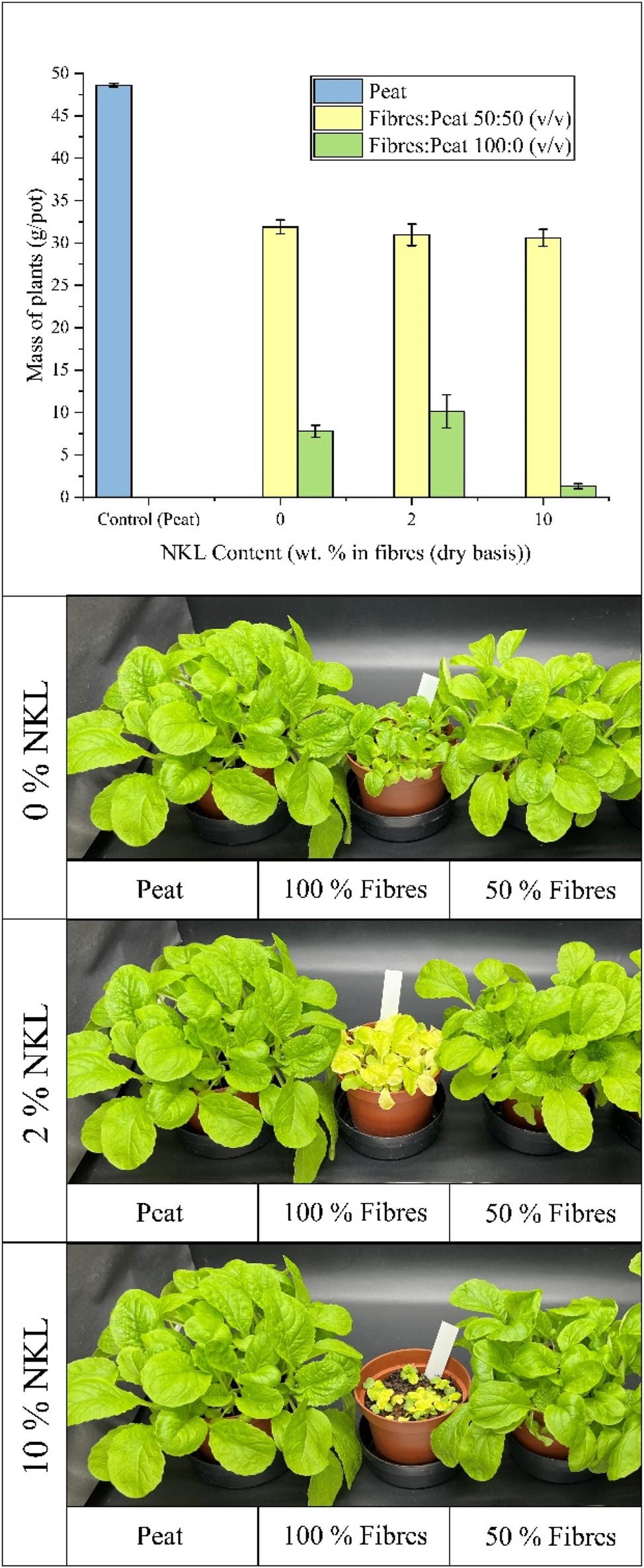

This negative effect was also clearly observed in the samples produced with fibre and peat substrates. In the substrates composed of 50 % fibres, no improvement was observed with the addition of NKL, as nearly no differences in plant mass between samples with 0 %, 2 %, and 10 % NKL were visible (Figure 10). It is important to consider that the fibres used in this case are different than the ones for the NOCL test and exhibit slightly better performance, as evidenced by the plant mass per pot results for the substrates without N-lignin. Specifically, for the 50 % fibre substrate without N-lignin, the wood fibres used in the NKL test resulted in nearly double the plant mass per pot compared to the fibres used in the NOCL test. When adding N-lignin to the substrate, two potentially opposing effects could occur. On one hand, the reduction of the nitrogen immobilization in the fibres could improve plant growth. On the other hand, the potential growth-inhibiting effect of N-lignin – evaluated in the negative control experiments with peat – could inhibit plant growth. In the case of the 50 % fibre substrate with NKL, it is possible that these opposing effects counterbalance each other, particularly when considering the dilution effect of lignin, as discussed earlier. Nevertheless, future tests with a higher number of pots may be needed to confirm these results.

Results of the plant growth of Chinese cabbage test for mixes of wood fibres and peat with 0 %, 2 % and 10 % of NKL (ammoxidated kraft lignin).

For substrates composed of 100 % fibres, the addition of 2 % NKL did not show a relevant increase in plant mass per pot. Observations of plant appearance after the experiment suggested that plants grown in the substrate with 2 % NKL tended to exhibit a poorer condition compared to those grown in fibres without lignin, including some yellowing of the leaves. Additionally, the incorporation of 10 % NKL seemed to have a pronounced negative impact, as only small sprouts of Chinese cabbage were observed, accompanied by discoloration and notably low plant mass per pot (Figure 10). While these findings suggest that the negative effects of NKL observed in the peat control experiment might also influence the 100 % fibre substrates, these results should be interpreted with caution until further studies with a higher sample size are conducted to confirm these trends. In contrast to NOCL, there are several studies that have utilized NKL in plant cultivation tests, which were reviewed earlier (Coniglio et al. 2024). However, in all cases, these studies evaluate its performance as a fertilizer in non-fibrous substrates: Therefore, the comparison to the results of this study should be interpreted with caution since this also implies that nitrogen application rates considerably lower than those used in this study are required. Ramirez et al. (1997) compares the performance of NKL as a fertilizer with ammonium sulphate. The test was conducted by cultivating sorghum in pots containing three plants, with seven replicates, using nitrogen loads of 160 kg N/ha, which equates to 4.3 g of fertilizer per pot. Considering a total of 4 kg of substrate, this represents 0.1 % of lignin. Given the considerably lower performance observed compared to commercial fertilizer, the authors also tripled the dose. Even at this increased rate, 0.3 % lignin is still much lower than the amounts evaluated in this study as a substrate improver. It was only with this higher load that grain yield for sorghum cultivation over 66 days showed an increase compared to the reference. However, it is reasonable to conclude that the potential inhibitory effect of NKL is negligible at such low N-lignin concentrations.In subsequent studies, nitrogen application rates were even lower, such as 120 kg N/ha (Ramírez-Cano et al. 2001) and 130 kg N/ha (Ramírez et al. 2007). In a more recent study, Ngiba et al. (2022) evaluated the performance of various types of N-lignins as fertilizers compared to commercial fertilizers. In this case, the application rate was again much lower than in the present study. Pots containing 1.5 kg of Malmesbury river sand were treated with 5 g of N-lignin per pot through irrigation, applied in three doses for a total of 15 g N-lignin per pot. This corresponds to 0.33 % N-lignin in relation to the substrate per application, totalling 1 % by the final dose. In addition to being lower than the 2 % and 10 % considered in this study, it should also be noted that due to the method of application, any potential inhibitory effect of N-lignin was likely further diluted compared to its incorporation into the substrate at the start of cultivation. Furthermore, the fact that in previous studies N-lignins were used as fertilizers implies that the type of nitrogen they were expected to provide differs from the focus of this work. Specifically, in the work from Ngiba et al. (2022), N-lignin was expected to provide nitrogen availability comparable to commercial fertilizer. However, plant yields were lower. It remains unclear whether this was due to a toxic effect or because some of the nitrogen was not available to plants. In the present study, it is evident that under the conditions tested, ammoxidized NKL shows inhibitory effects on Chinese cabbage growth at concentrations of 2 % and 10 %. It is important to emphasize, however, that the plants used were different, so the results are not directly comparable. On the other hand, as already clarified, to detect a significant effect, a test with a larger number of pots should be conducted.

4 Conclusions

The results of this study demonstrated that ammoxidation effectively increased the total-N content of lignins, achieving a maximum of 6.3 wt% in NKL under elevated pressures (60 bar), although the proportion of desirable amide-N remained limited, indicating that current ammoxidation conditions do not optimally favour the formation of this nitrogen type compared to less desirable bound-N. Furthermore, the analysis revealed that oxygen pressure and reaction time had significant impacts on the overall nitrogen incorporation, while temperature exhibited minimal effects. An increase in oxygen pressure led to higher nitrogen incorporation rates; however, this was accompanied by a decrease in the selectivity for amide-N. Adjusting the reaction conditions of ammoxidation does not lead to improved N-lignins; instead, the enhancement of amide-N correlates with an undesirable increase in bound-N. Therefore, it becomes evident that merely modifying the reaction parameters within the ammoxidation framework is insufficient for achieving the desired outcomes. Cultivation tests with Chinese cabbage showed that the addition of 2 % NOCL enhanced plant growth in 100 % wood-fibre substrates, resulting in higher dry mass of plants compared to lignin-free control. Conversely, at a concentration of 10 % NOCL, a decline in growth was observed, highlighting a potential growth-inhibiting effect at elevated lignin concentrations. In substrates composed of 50 % peat and fibre mixtures, the addition of NOCL benefited growth at both concentrations compared to the substrate without N-lignin. In substrates composed of 50 % peat and fibre mixtures, the addition of NKL did not impact plant growth. In contrast, NKL negatively impacted plant growth in 100 % wood-fibre substrates even at a 2 % concentration, suggesting that the specific characteristics of each lignin type can significantly influence their effectiveness as substrate improvers. Further tests with larger sample size are needed to confirm these tendencies. Given the findings of this study, it is shown that alternative strategies aimed at enhancing lignin reactivity prior to ammoxidation are imperative. Overall, this study contributes valuable insights into the viability of the use of nitrogen-enriched lignins as substrate improvers in order to develop wood fibres, which act as sustainable peat substitutes in horticultural applications, while also emphasizing the need for further research to optimize ammoxidation methodologies and evaluate the performance of these substrates.

Funding source: Thünen-Institut

Award Identifier / Grant number: HoFaTo

Funding source: Agencia Nacional de Investigación e Innovación

Award Identifier / Grant number: POS_EXT_2023_2_180080

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Niklas Bongarts, Sina Ehrich, Silke Radtke and Christiane Riegert for the technical support. Financial support of the first author’s studies provided by the National Research and Innovation Agency of Uruguay (ANII) [POS_EXT_2023_2_180080] is greatly appreciated.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: Some paragraphs in this manuscript were improved with the assistance of ChatGPT, an AI language model developed by OpenAI.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: The project “HoFaTo” was funded by the Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture as part of the German Climate Protection Programme 2022. The first author was funded by National Research and Innovation Agency of Uruguay (ANII) [POS_EXT_2023_2_180080].

-

Data availability: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, RC, upon reasonable request.

References

Agarwal, P., Saha, S., and Hariprasad, P. (2023). Agro-industrial-residues as potting media: physicochemical and biological characters and their influence on plant growth. Biomass Convers. Biorefi. 13: 9601–9624, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13399-021-01998-6.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Andriani, F. and Lawoko, M. (2024). Oxidative carboxylation of lignin: exploring reactivity of different lignin types. Biomacromolecules 25: 4246–4254, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.biomac.4c00326.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Atzori, G., Pane, C., Zaccardelli, M., Cacini, S., and Massa, D. (2021). The role of peat-free organic substrates in the sustainable management of soilless cultivations. Agronomy 11: 1236, https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy11061236.Suche in Google Scholar

Aurdal, S.M., Woznicki, T.L., Haraldsen, T.K., Kusnierek, K., Sønsteby, A., and Remberg, S.F. (2023). Wood fiber-based growing media for strawberry cultivation: effects of incorporation of peat and compost. Horticulturae 9, https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae9010036.Suche in Google Scholar

Barrett, G.E., Alexander, P.D., Robinson, J.S., and Bragg, N.C. (2016). Achieving environmentally sustainable growing media for soilless plant cultivation systems – a review. Sci. Hortic. 212: 220–234, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2016.09.030.Suche in Google Scholar

Capanema, E.A., Balakshin, M., Chen, C.L., Gratzl, J.S., and Kirkman, A.G. (2001a). Oxidative ammonolysis of technical lignins. Part 1: kinetics of the reaction under isothermal condition at 130°C. Holzforschung 55: 397–404, https://doi.org/10.1515/hf.2001.066.Suche in Google Scholar

Capanema, E.A., Balakshin, M.Y., Chen, C.L., Gratzl, J.S., and Kirkman, A.G. (2001b). Oxidative ammonolysis of technical lignins. Part 2: effect of oxygen pressure. Holzforschung 55: 405–412, https://doi.org/10.1515/hf.2001.067.Suche in Google Scholar

Capanema, E.A., Balakshin, M.Y., Chen, C.L., Gratzl, J.S., and Kirkman, A.G. (2002). Oxidative ammonolysis of technical lignins. Part 3: effect of temperature on the reaction rate. Holzforschung 56: 402–415, https://doi.org/10.1515/hf.2002.063.Suche in Google Scholar

Coniglio, R., Schütt, F., and Appelt, J. (2024). Challenges for the utilization of ammoxidized lignins and wood fibres as a peat substitute in horticultural substrates. J. Clean. Production 475, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.143737.Suche in Google Scholar

Dickson, R.W., Helms, K.M., Jackson, B.E., Machesney, L.M., and Lee, J.A. (2022). Evaluation of peat blended with pine wood components for effects on substrate physical properties, nitrogen immobilization, and growth of Petunia (Petunia ×hybrida Vilm.-Andr.). HortScience 57: 304–311, https://doi.org/10.21273/hortsci16177-21.Suche in Google Scholar

Draper, Norman R. and Smith, Harry (2014). Applied regression analysis, 3rd ed. Wiley, Toronto.Suche in Google Scholar

Fabbri, F., Bischof, S., Mayr, S., Gritsch, S., Jimenez Bartolome, M., Schwaiger, N., Guebitz, G.M., and Weiss, R. (2023). The biomodified lignin platform: a review. Polymers 15: 1694, https://doi.org/10.3390/polym15071694.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Feofilova, E.P. and Mysyakina, I.S. (2016). Lignin: chemical structure, biodegradation, and practical application (a review). Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 52: 573–581, https://doi.org/10.1134/S0003683816060053.Suche in Google Scholar

Field, A.P. (2018). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics. Sage Publications, London.Suche in Google Scholar

Fischer, K. and Schiene, R. (2002) Nitrogenous fertilizers from lignins – a review. In: Hu, T.Q. (Ed.). Chemical modification, properties and usage of lignin. Academic Plenum Publishers, pp. 167–198.10.1007/978-1-4615-0643-0_10Suche in Google Scholar

Gellerstedt, G. (2015). Softwood kraft lignin: raw material for the future. Ind. Crops Prod. 77: 845–854, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2015.09.040.Suche in Google Scholar

Gruda, N. (2012). Current and future perspective of growing media in Europe. Acta Hortic. 960: 37–43, https://doi.org/10.17660/actahortic.2012.960.3.Suche in Google Scholar

Gruda, N.S. (2021) Soilless culture systems and growing media in horticulture: an overview. In: Gruda, N.S. (Ed.). Advances in horticultural soilless culture. Burleigh Dodds, Dublin, pp. 1–17.10.1201/9781003048206-1Suche in Google Scholar

Hair, Joseph, Anderson, Rolph, Babin, Barry, and Black, William (2010). Multivariate data analysis, 7th ed. Pearson, New York.Suche in Google Scholar

Harth, F.M., Hočevar, B., Kozmelj, T.R., Jasiukaitytė-Grojzdek, E., Blüm, J., Fiedel, M., Likozar, B., and Grilc, M. (2023). Selective demethylation reactions of biomass-derived aromatic ether polymers for bio-based lignin chemicals. Green Chem. 25: 10117–10143, https://doi.org/10.1039/d3gc02867d.Suche in Google Scholar

Jansson, S.L. and Persson, J. (1982) Mineralization and Immobilization of soil nitrogen. In: Nitrogen in agricultural soils. John Wiley & Sons, pp. 229–252.10.2134/agronmonogr22.c6Suche in Google Scholar

Joosten, H. (2010). The global peatland CO2 picture: peatland status and drainage related emissions in all countries of the world. Wetlands International, Ede.Suche in Google Scholar

Kai, D., Tan, M.J., Chee, P.L., Chua, Y.K., Yap, Y.L., and Loh, X.J. (2016). Towards lignin-based functional materials in a sustainable world. Green Chem. 18: 1175–1200, https://doi.org/10.1039/c5gc02616d.Suche in Google Scholar

Kern, J., Tammeorg, P., Shanskiy, M., Sakrabani, R., Knicker, H., Kammann, C., Tuhkanen, E.M., Smidt, G., Prasad, M., Tiilikkala, K., et al.. (2017). Synergistic use of peat and charred material in growing media: an option to reduce the pressure on peatlands? J. Environ. Eng. Landsc. Manag. 25: 160–174, https://doi.org/10.3846/16486897.2017.1284665.Suche in Google Scholar

Klinger, K.M., Liebner, F., Fritz, I., Potthast, A., and Rosenau, T. (2013a). Formation and ecotoxicity of N-heterocyclic compounds on ammoxidation of mono- and polysaccharides. J. Agric. Food Chem. 61: 9004–9014, https://doi.org/10.1021/jf4019596.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Klinger, K.M., Liebner, F., Hosoya, T., Potthast, A., and Rosenau, T. (2013b). Ammoxidation of lignocellulosic materials: formation of nonheterocyclic nitrogenous compounds from monosaccharides. J. Agric. Food Chem. 61: 9015–9026, https://doi.org/10.1021/jf401960m.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Lapierre, C., Monties, B., Meier, D., and Faix, O. (1994). Structural Investigation of kraft lignins transformed via oxo-ammoniation to potential nitrogenous fertilizers. Holzforschung 48: 63–68, https://doi.org/10.1515/hfsg.1994.48.s1.63.Suche in Google Scholar

Laurichesse, S. and Avérous, L. (2014). Chemical modification of lignins: towards biobased polymers. Prog. Polym. Sci. 39: 1266–1290, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2013.11.004.Suche in Google Scholar

Lindner, A. and Wegener, G. (1988). Characterization of lignins from organosolv pulping according to the Organocell process part 1. Elemental analysis, nonlignin portions and functional groups. J. Wood Chem. Technol. 8: 323–340, https://doi.org/10.1080/02773818808070688.Suche in Google Scholar

Lora, J.H. and Glasser, W.G. (2002). Recent industrial applications of lignin: a sustainable alternative to nonrenewable materials. J. Environ. Polym. 10: 39–48, https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1021070006895.10.1023/A:1021070006895Suche in Google Scholar

Montgomery, D.C. (2017). Design and analysis of experiments. John Wiley & Sons, New York.Suche in Google Scholar

Moore, P.D. (1989). The ecology of peat-forming processes: a review. Int. J. Coal Geol. 12: 89–103, https://doi.org/10.1016/0166-5162(89)90048-7.Suche in Google Scholar

Ngiba, Q., Görgens, J.F., and Tyhoda, L. (2022). Lignin ammoxidation: synthesis of nitrogen releasing soil conditioning products from waste pulp liquor and their pot trial evaluation. Waste Biomass Valorization 13: 4785–4796, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12649-022-01830-w.Suche in Google Scholar

Pandey, M.P. and Kim, C.S. (2011). Lignin depolymerization and conversion: a review of thermochemical methods. Chem. Eng. Technol. 34: 29–41, https://doi.org/10.1002/ceat.201000270.Suche in Google Scholar

Potthast, A., Schiene, R., and Fischer, K. (1996). Structural investigations of N-modified lignins by 15N-NMR spectroscopy and possible pathways for formation of nitrogen containing compounds related to lignin. Holzforschung 50: 554–562, https://doi.org/10.1515/hfsg.1996.50.6.554.Suche in Google Scholar

Qi-Pei, J., Xiao-Yong, Z., Hai-Tao, M., and Zuo-Hu, L. (2006). Ammoxidation of straw-pulp alkaline lignin by hydrogen peroxide. Environ. Prog. 25: 251–256, https://doi.org/10.1002/ep.10148.Suche in Google Scholar

Ramirez, F., González, V., Crespo, M., Meier, D., Faix, O., and Zhiiga, V. (1997). Ammoxidized kraft lignin as a slow-release fertilizer tested on Sorghum vulgare. Bioresour. Technol. 61: 43–46, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0960-8524(97)84697-4.Suche in Google Scholar

Ramírez, F., Varela, G., Delgado, E., López-Dellamary, F., Zúñiga, V., González, V., Faix, O., and Meier, D. (2007). Reactions, characterization and uptake of ammoxidized kraft lignin labeled with 15N. Bioresour. Technol. 98: 1494–1500, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2005.08.004.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Ramírez-Cano, F., Ramos-Quirarte, A., Faix, O., Meier, D., González-Alvarez, V., and Zúñiga-Partida, V. (2001). Slow-release effect of N-functionalized kraft lignin tested with Sorghum over two growth periods. Bioresour. Technol. 76: 71–73, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0960-8524(00)00066-3.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Rinaldi, R., Jastrzebski, R., Clough, M.T., Ralph, J., Kennema, M., Bruijnincx, P.C.A., and Weckhuysen, B.M. (2016). Paving the way for lignin valorisation: recent advances in bioengineering, biorefining and catalysis. Angew. Chem. 128: 8296–8354, https://doi.org/10.1002/ange.201510351.Suche in Google Scholar

Roulet, N.T. (2000). Peatlands, carbon storage, greenhouse gases, and the Kyoto protocol: prospects and significance for Canada. Wetlands 20: 605–615, https://doi.org/10.1672/0277-5212(2000)020[0605:pcsgga]2.0.co;2.10.1672/0277-5212(2000)020[0605:PCSGGA]2.0.CO;2Suche in Google Scholar

Schmilewski, G. (2008). The role of peat in assuring the quality of growing media. Mires and Peat 3.Suche in Google Scholar

Socrates, G. (2001). Infrared and Raman characteristic group frequencies: tables and charts, 3rd ed. John Wiley & Sons, Chichester.Suche in Google Scholar

Tyhoda, L. (2008). Synthesis, characterisation and evaluation of slow nitrogen release organic soil conditioners from south african technical lignins. PhD thesis. University of Stellenbosch, Stellenbosch.Suche in Google Scholar

Vandecasteele, B., Van Loo, K., Ommeslag, S., Vierendeels, S., Rooseleer, M., and Vandaele, E. (2022). Sustainable growing media blends with woody green composts: optimizing the N release with organic fertilizers and interaction with microbial biomass. Agronomy 12, https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy12020422.Suche in Google Scholar

Wurzer, G.K., Hettegger, H., Bischof, R.H., Fackler, K., Potthast, A., and Rosenau, T. (2021). Agricultural utilization of lignosulfonates. Holzforschung 76: 155–168, https://doi.org/10.1515/hf-2021-0114.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- The 17th European Workshop on Lignocellulosics and Pulp (EWLP) in Turku/Åbo, Finland (August 26–30, 2024)

- Wood Chemistry

- Exploring the potential of ammoxidation of lignins to enhance amide-nitrogen for wood-based peat alternatives and its impact on plant development

- Supercritical carbon dioxide extraction of crude tall oil: an alternative upgrading approach

- Wood Technology/Products

- Swelling of cellulose stimulates etherification

- Machine learning-assisted spectrometric method for pulp extractive analysis based on model pulps

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- The 17th European Workshop on Lignocellulosics and Pulp (EWLP) in Turku/Åbo, Finland (August 26–30, 2024)

- Wood Chemistry

- Exploring the potential of ammoxidation of lignins to enhance amide-nitrogen for wood-based peat alternatives and its impact on plant development

- Supercritical carbon dioxide extraction of crude tall oil: an alternative upgrading approach

- Wood Technology/Products

- Swelling of cellulose stimulates etherification

- Machine learning-assisted spectrometric method for pulp extractive analysis based on model pulps