Abstract

Language courses in heterogeneous classes present frequent and complex teaching challenges throughout universities. To remedy these teaching-learning situations, which are complicated for both the teacher and the learner, a blended learning system aimed at developing student autonomy has been devised. This approach provides instruction tailored to individual needs while maintaining the class cohesion necessary for successful course delivery. The blended learning model, which is based on project-based teaching, autonomous learning and differentiated teaching, calls on a wide range of transversal competencies to ensure that it works properly. The aim of this article is to summarise our theoretical framework, describe the system, illustrate the chosen research methodology, and provide the results of our study. While previous studies based on a three-stage action research process have demonstrated the system’s effectiveness in addressing heterogeneity, the findings also reveal that learners perceive the system as enabling the simultaneous development of several transversal competencies, including curiosity, creativity, collaboration, communication, confidence, and digital literacy. The findings of this study provide concrete insights for practitioners seeking to implement differentiated pedagogical approaches in heterogeneous contexts, while also highlighting promising avenues for researchers exploring the impact of transversal competencies in language learning.

Résumé

Les cours de langues dans des classes hétérogènes posent fréquemment des défis pédagogiques complexes dans les universités. Pour remédier à ces situations d’enseignement-apprentissage, qui compliquent autant le travail de l’enseignant que celui de l’apprenant, un dispositif hybride visant à développer l’autonomie des étudiants a été conçu. Cette approche propose un enseignement adapté aux besoins individuels tout en maintenant la cohésion de classe nécessaire à la réussite des cours. Le dispositif hybride, qui s’appuie sur une approche par projets, l’autonomie d’apprentissage et la pédagogie différenciée, mobilise un large éventail de compétences transversales pour fonctionner efficacement. Cet article vise à présenter notre cadre théorique, à décrire le dispositif, à illustrer la méthodologie de recherche choisie et à présenter les résultats de notre étude. Des études antérieures basées sur un processus de recherche-action en trois étapes ont démontré l’efficacité du dispositif pour traiter l’hétérogénéité. Les résultats révèlent également que les apprenants perçoivent ce système comme permettant le développement simultané de plusieurs compétences transversales, telles que la curiosité, la créativité, la collaboration, la communication, la confiance et les compétences numériques. Ces résultats offrent des perspectives concrètes pour les praticiens souhaitant mettre en œuvre des approches pédagogiques différenciées dans des contextes hétérogènes, tout en mettant en lumière des pistes prometteuses pour les chercheurs explorant l’impact des compétences transversales dans l’apprentissage des langues.

Resumen

Los cursos de idiomas en clases heterogéneas presentan con frecuencia desafíos pedagógicos complejos en las universidades. Para remediar estas situaciones de enseñanza-aprendizaje, que complican tanto el trabajo del docente como el del estudiante, se ha diseñado un sistema híbrido destinado a desarrollar la autonomía de los estudiantes. Este enfoque propone una enseñanza adaptada a las necesidades individuales mientras mantiene la cohesión grupal necesaria para el éxito de los cursos. El sistema híbrido, que se basa en un enfoque por proyectos, la autonomía en el aprendizaje y la enseñanza diferenciada moviliza una amplia gama de competencias transversales para funcionar eficazmente. Este artículo tiene como objetivo presentar nuestro marco teórico, describir el sistema, ilustrar la metodología de investigación elegida y exponer los resultados de nuestro estudio. Estudios previos basados en un proceso de investigación-acción en tres etapas han demostrado la eficacia del sistema para abordar la heterogeneidad. Los resultados también revelan que los estudiantes perciben este sistema como una herramienta para el desarrollo simultáneo de varias competencias transversales, tales como la curiosidad, la creatividad, la colaboración, la comunicación, la confianza y las competencias digitales. Estos resultados ofrecen perspectivas concretas para los profesionales que deseen implementar enfoques pedagógicos diferenciados en contextos heterogéneos, al mismo tiempo que destacan vías prometedoras para los investigadores que exploren el impacto de las competencias transversales en el aprendizaje de idiomas.

Zusammenfassung

Sprachkurse in heterogenen Klassen stellen an Universitäten häufig komplexe pädagogische Herausforderungen dar. Um diese Lehr-Lernsituationen, die sowohl für Lehrkräfte als auch für Lernende schwierig sind, zu bewältigen, wurde ein hybrides Lernsystem entwickelt, das darauf abzielt, die Autonomie der Studierenden zu fördern. Dieser Ansatz bietet eine auf die individuellen Bedürfnisse abgestimmte Lehre und bewahrt gleichzeitig die notwendige Klassenkohäsion für eine erfolgreiche Kursdurchführung. Das hybride Lernmodell, das auf projektbasiertem Unterricht, autonomem Lernen und differenzierter Lehre basiert, fordert ein breites Spektrum an transversalen Kompetenzen, um effektiv zu funktionieren. Ziel dieses Artikels ist es, unseren theoretischen Rahmen zusammenzufassen, das System zu beschreiben, die gewählte Forschungsmethodik zu veranschaulichen und die Ergebnisse unserer Studie zu präsentieren. Während frühere Studien, die auf einem dreistufigen Aktionsforschungsprozess basieren, die Wirksamkeit des Systems bei der Bewältigung von Heterogenität aufgezeigt haben, zeigen die Ergebnisse auch, dass Lernende das System als förderlich für die gleichzeitige Entwicklung mehrerer transversaler Kompetenzen wahrnehmen, darunter Neugier, Kreativität, Zusammenarbeit, Kommunikation, Selbstvertrauen und digitale Kompetenz. Die Ergebnisse dieser Studie bieten konkrete Einblicke für Praktiker, die differenzierte pädagogische Ansätze in heterogenen Kontexten umsetzen möchten, und eröffnen gleichzeitig vielversprechende Wege für Forscher, die die Auswirkungen transversaler Kompetenzen im Sprachlernen untersuchen.

1 Introduction

French as a foreign language (FFL) courses with learners of different proficiency levels are common in university settings. A June 2021 study revealed that a quarter of learners experienced a slowdown in their learning and decreased motivation in this context (Pouzergues, 2023). A blended learning system for differentiated teaching with the aim of autonomy development was designed to meet the specific needs of learners while maintaining the cohesion of the class group. While the system’s effectiveness has been demonstrated in previous studies (Pouzergues 2023; Nissen 2019; Sagarra & Zapata 2008), this study focuses on the development of selected transversal competencies mobilized during the course.

In this study, we aim to answer the following question: How do learners perceive and experience the efficacy of a blended learning system rooted in (1) a project-based approach, (2) pedagogical differentiation, and (3) the development of learner autonomy to foster transversal competencies?

After describing the key concepts related to course design and transversal competencies, we’ll present the system to clarify the competencies involved. We will then present the methodology employed, the corpus studied and conclude with the results obtained.

2 Theoretical framework

2.1 Heterogeneity in language classes

Disparities in language proficiency are the most readily identifiable aspect of classroom heterogeneity. Two main categories can be distinguished: inter-individual heterogeneity, which refers to the different CEFR[1] (Common European Framework of Reference for Languages) levels present in the same class (A1 to C2), and intra-individual heterogeneity, which characterizes the different levels of competency that the same learner may possess in the five CEFR language skills: listening comprehension, reading comprehension, writing, speaking and oral interaction.

In addition, other forms of heterogeneity influence FFL learning in the university environment. These include disparities related to the learning environment, such as the diversity of educational contexts and learners’ specific needs (Castellotti & Moore, 2008; Mangiante, 2017), psychological disparities, such as learners’ cognitive differences, personal motivations and emotional diversity (Ryan & Deci, 2000), and learners’ biographies, including their educational and cultural backgrounds, as well as their varied linguistic experiences (Huver, 2015).

Given these multiple dimensions of heterogeneity that characterize FFL university classes, the question arises: how can pedagogical approaches be designed to effectively accommodate such diversity? The following section explores various strategies that have been developed to address these challenges.

2.2 Taking heterogeneity into consideration

The various forms of heterogeneity require special attention from teachers to adapt their teaching methods and meet the needs of all learners.

Indeed, as Larsen-Freeman points out: “each individual [. . .] acts as a unique learning context, bringing a different set of systems to a learning event, responding differently to it, and therefore, learning differently as a result of participating in it” (Larsen-Freeman 2013: 79).

While some authors describe the homogeneous classroom as a “myth“ (Matsuda 2006), for Robbes it’s an “indisputable anthropological observation: heterogeneity between humans is a fact, and this fact constitutes the main justification for differentiated pedagogy” (Robbes 2009: 5).

2.2.1 Pedagogical differentiation

The primary aim of differentiation is to meet the needs of the learner and “embraces all the initiatives a teacher can undertake to recognize the differences between his or her students“ (Kahn 2010: 5). Furthermore, differentiation “allows pupils to understand their own learning styles and to negotiate their own targets. In other words, it encourages positive involvement and increased autonomy” (Coffey 2018: 188), which is particularly relevant in our context.

Coffey (2018: 190–192) proposes four strategies for effective differentiation:

Providing optimal challenges: The task-project must correspond to learners’ expectations, needs and profiles, and thus enable them to become highly involved in their own learning (Almulla 2020). Project-based learning also gives each learner the opportunity to take part in group projects, despite the heterogeneity present in the classroom, while providing a unifying framework (David 2013).

Level of learning: Learners should be offered activities that are within their reach, but not too easy. Tasks that are either overly challenging or too simple risk causing distraction and, over time, disengagement. It is the application of Bruner’s concept of scaffolding that enables learners to progress beyond their zone of proximal development (Wilson & Devereux 2014).

Pace of learning: Pace of learning refers to the speed at which new elements are introduced and the time allowed for their assimilation. This aspect is complex for the teacher to master, especially in face-to-face teaching when working in sub-groups. However, the remote modality of a blended learning system proves particularly useful and effective in enabling learners to follow their own pace (O’Byrne & Pytash 2015).

Type of learning: This strategy aims to take into account different learner profiles (cf. 2.1 heterogeneity). To explicitly address all “intelligence types” and learning styles in every lesson, new teachers quickly realize that learners can often create their own effective learning strategies when given sufficient freedom. This highlights the importance of fostering autonomy and self-awareness by teaching students how to develop learning skills (Coffey 2018).

In the following section, we will discuss the significance of learner autonomy and examine its specific contribution within differentiated pedagogy.

2.2.2. Learner autonomy

Learner autonomy is central to the theory and practice of language teaching (Little 2007: 27) and plays a key role in differentiated pedagogy and blended learning. It is defined as a learner’s ability to manage his or her own learning (Holec 1979: 3), which includes setting goals, choosing resources and strategies, evaluating results, and managing learning. This ability is most often acquired through formal learning (ibid), and although it is difficult to teach autonomy in a comprehensive way, specific skills can be developed to encourage it (Albero 2003: 7).

Moreover, the (co-)development of language proficiency and learner autonomy should not be separated as they are “mutually supporting and fully integrated with each other” (Little 2007: 14). This interconnectedness underlines the importance of tools and strategies that foster both dimensions simultaneously.

The tools used in language resource centers (Cappellini, Lewis & Rivens Mompean 2017) are

individual advice interviews providing conceptual, methodological and psychological support; learning to learn sessions aimed at developing learners’ learning skills by drawing on their individual experiences; collective logbooks promoting learner involvement and the creation of a community of practice; ePortfolios, which are systematic collections of student work analyzed to show progress (Kohonen & Westhoff, 2001).

These four tools, through the implementation of metacognitive regulation, contribute to the development of learner autonomy, essential to differentiated pedagogy in heterogeneous contexts (see: Pouzergues 2022).

Blended learning environments, particularly those that incorporate project-based approaches, represent a valuable opportunity to both nurture learner autonomy and effectively implement pedagogical differentiation.

2.2.3 Blended learning and project-based pedagogy

“Blended Learning is the strategic combination of online and in-person learning” (Graham & Halverson 2022: 4). It is based on the use of an online learning platform and a so-called “active pedagogy” (such as a project-based pedagogy or service learning). These systems are structured around a pedagogical scenario (Nissen 2019) and a communication scenario (Mangenot 2008), enabling a harmonious integration of the two modalities. Support from a tutor or peer is essential for effective learning. Project tasks form the central pillar of the teaching scenario, being designed to prepare learners for real, authentic social actions, which engage them cognitively and interpersonally. These tasks also play a unifying role in a heterogeneous class and foster the development of learner autonomy.

Differentiated pedagogy, project-based learning, and the development of autonomy in a blended course frequently call for several transversal competencies. These competencies are essential to the successful functioning of the blended learning system (La Scala et al. 2022). We define these concepts in the following section. The convergence of differentiated pedagogy, learner autonomy, and project-based learning within blended environments constitutes a pedagogical framework designed to cultivate key learner competencies.

To address our research question, it is therefore necessary to define the specific transversal competencies mobilised and developed in such settings.

2.3 Transversal competencies

The notion of competency is defined as “a complex knowledge-action based on the effective mobilization and combination of a variety of internal and external resources within a family of situations“ (Tardif, Fortier & Préfontaine 2006: 22). Competency is characterized by actual application or execution. Thus, it is commonly accepted that it is clearly distinct from mere theoretical knowledge.

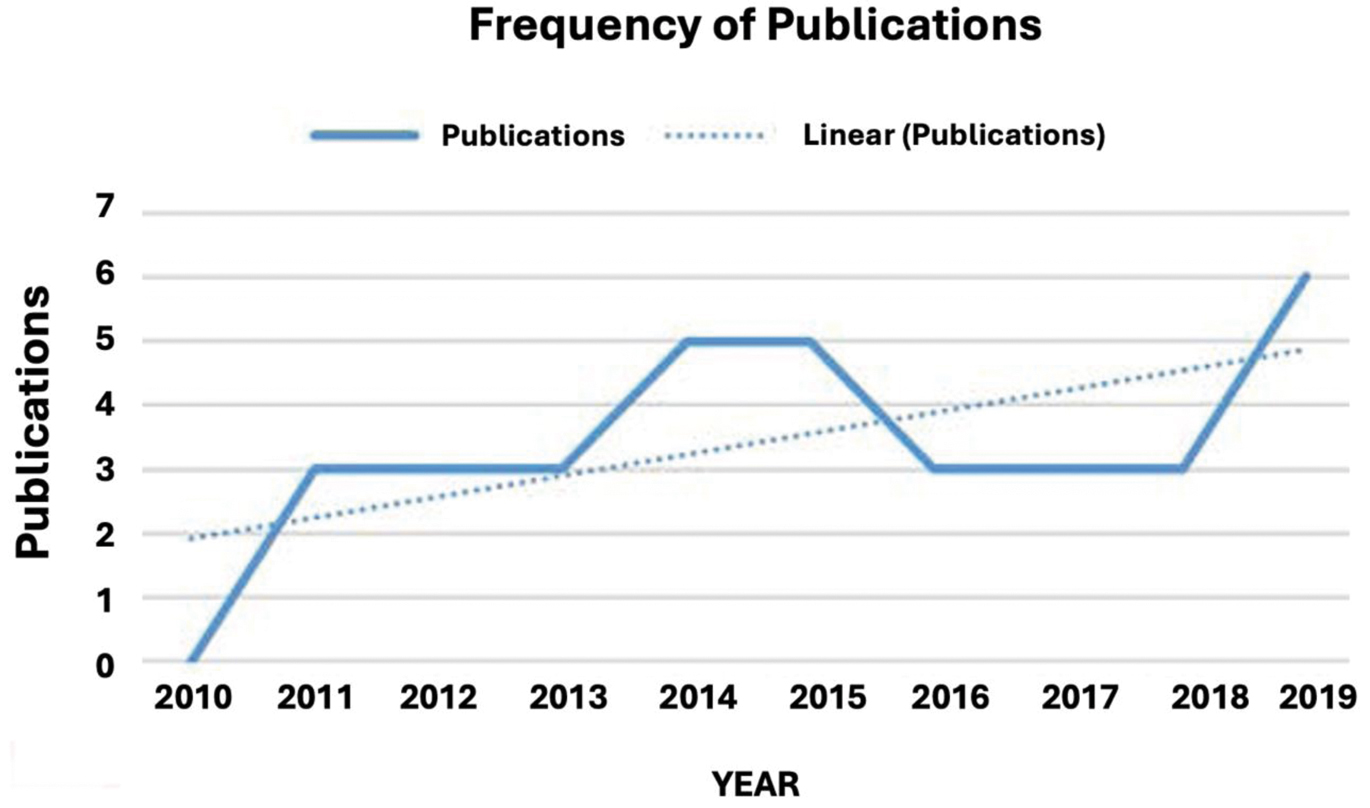

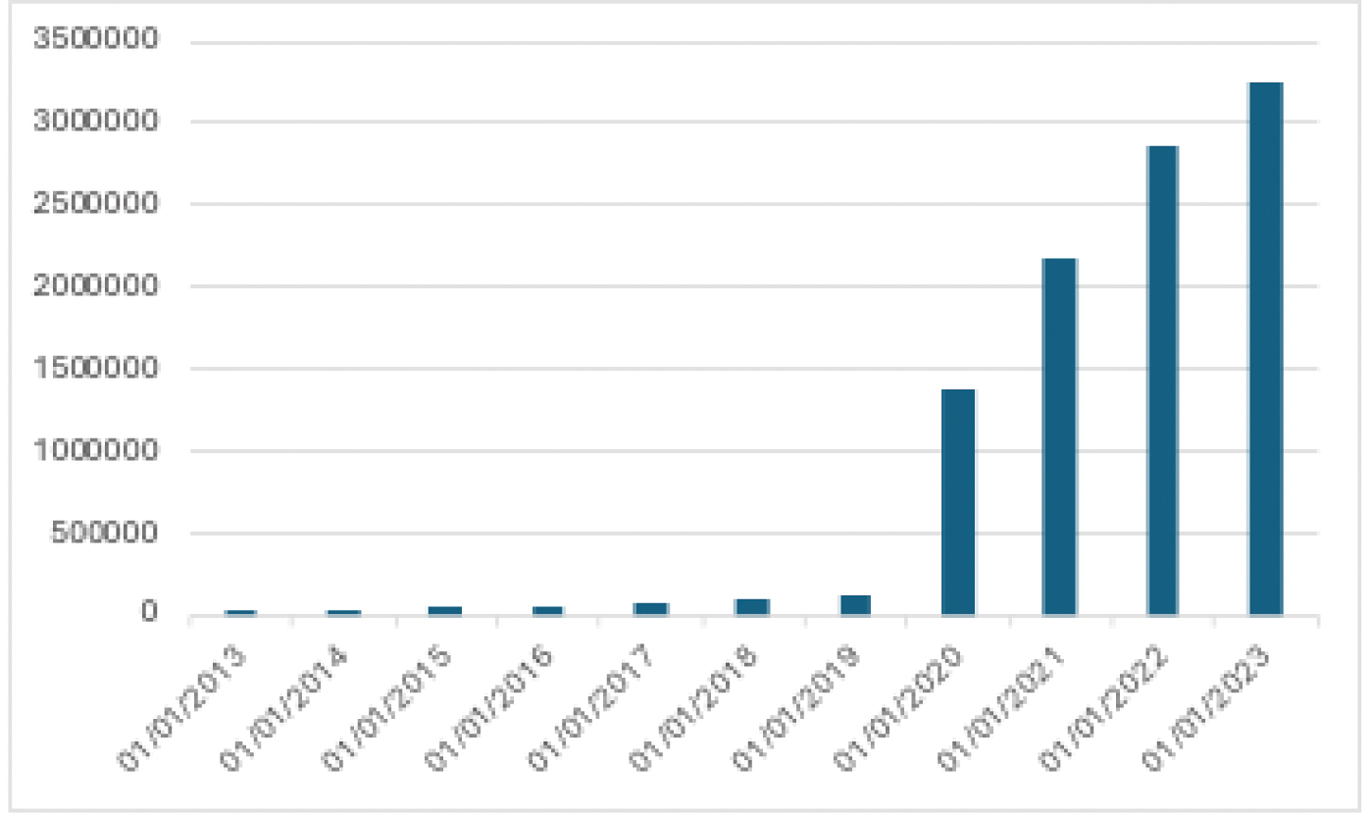

In the field of education, the idea of transversal competencies has been around for a long time, aiming to develop fundamental competencies in learners. Historically, university students were required to learn Latin and Greek to develop structured, argumentative thinking (Tardif & Dubois 2013). In recent years, there has been a marked resurgence of interest in transversal competencies, as shown by the bibliometric analysis represented in Figure 1 (Calero López & Rodríguez-López 2020), which evidences a significant rise in related scientific research. This interest is shared on the web, if we refer to the number of results referenced by Google, which have increased exponentially over the last ten years (between 2013 and 2023 as shown in Figure 2. However, specific studies on transversal competencies and language learning are still rare and their development remains difficult to evaluate (Tardif & Dubois 2013).

Frequency of publications on transversal competences 2010–2019 (Calero López & Rodríguez-López 2020).

Evolution of the number of results for the search “compétences transversales” ‘transversal competency’ on Google in French, between 20013 and 2023 (Personal statement of 10 July 2024).

A variety of terms overlap with transversal competencies can be found, such as soft skills, key competencies, transferable skills, cross-functional skills, 21st-century skills, or global competencies. However, they share the same fundamental essence, but vary slightly in terms of objectives and intentions, which is why we will speak of transversal competencies as more comprehensive and academic (Starck & Boancă 2019).

A review of certain conceptualizations of transversal competencies reveals two main characteristics (ibid), they are non-technical: not linked to a specific task or professional context. They encompass general abilities that can be applied in a variety of contexts, facilitating individual adaptability. And they are non-disciplinary: built against a disciplinary logic, in line with a presumed informal and/or non-formal acquisition. This means they transcend the boundaries of traditional academic disciplines, promoting holistic learning.

According to ESCO (European Skills, Competences and Occupations: a body of the European Commission) they are “the cornerstone for the personal development of a person”[2].

These transversal competencies are often highlighted for their importance in the professional integration and employability of students. One example is the European transval.eu project, which aims to make transversal competencies explicit in validation and orientation processes. With this in mind, a number of universities have proposed university repositories of transversal competencies such as the Université de Montréal’s Référentiel des compétences transversales favorisant l’intégration professionnelle des étudiants aux cycles supérieurs[3], or the University of Ottawa’s uOcompetencies[4].

These six transversal competencies—curiosity, collaboration, communication, creativity, confidence, and digital literacy—were chosen for their critical role in fostering adaptability and success in higher educational learning contexts (Sá & Serpa 2018). Their selection is grounded in established competency frameworks such as the Université de Montréal’s Référentiel des compétences transversales and the University of Ottawa’s uOcompetencies, which emphasize their importance for higher education and professional integration.

These competencies are closely aligned with the employed pedagogical approaches—including project-based learning, differentiated teaching, and autonomy development—all of which inherently require active engagement with these competencies.

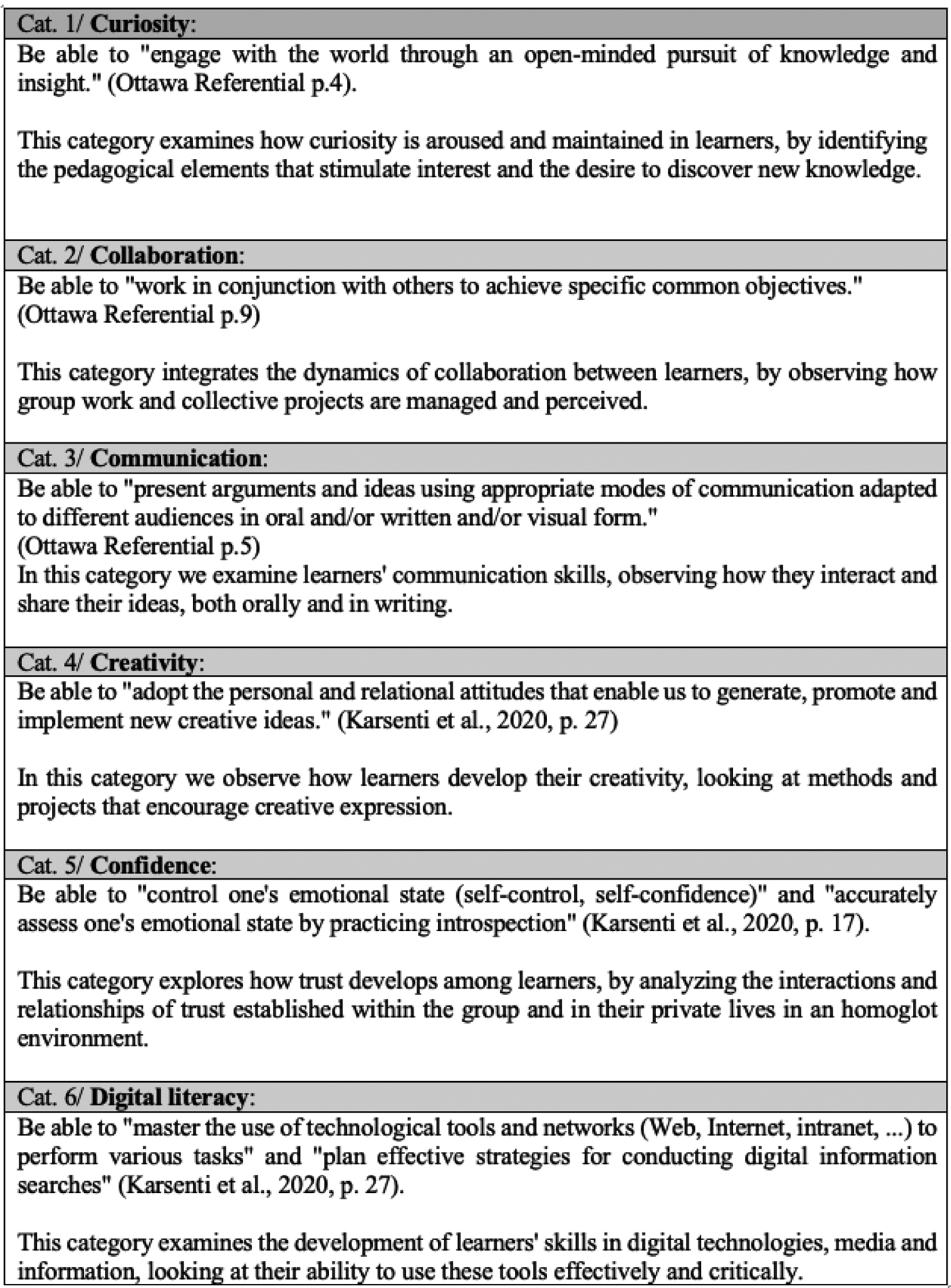

The detailed definitions of the six transversal competencies (curiosity, collaboration, communication, creativity, confidence, and digital literacy) used in this study are provided in Appendix 1. The development of autonomy is not covered here, as it has already been dealt with in another article (Pouzergues & Cappellini 2022). We will rely on these definitions when analyzing the content of the data and selecting coding categories.

Building on these theoretical foundations, the following section presents the blended learning system designed to address our research question: how do learners perceive and experience the efficacy of the learning system in fostering transversal competencies?

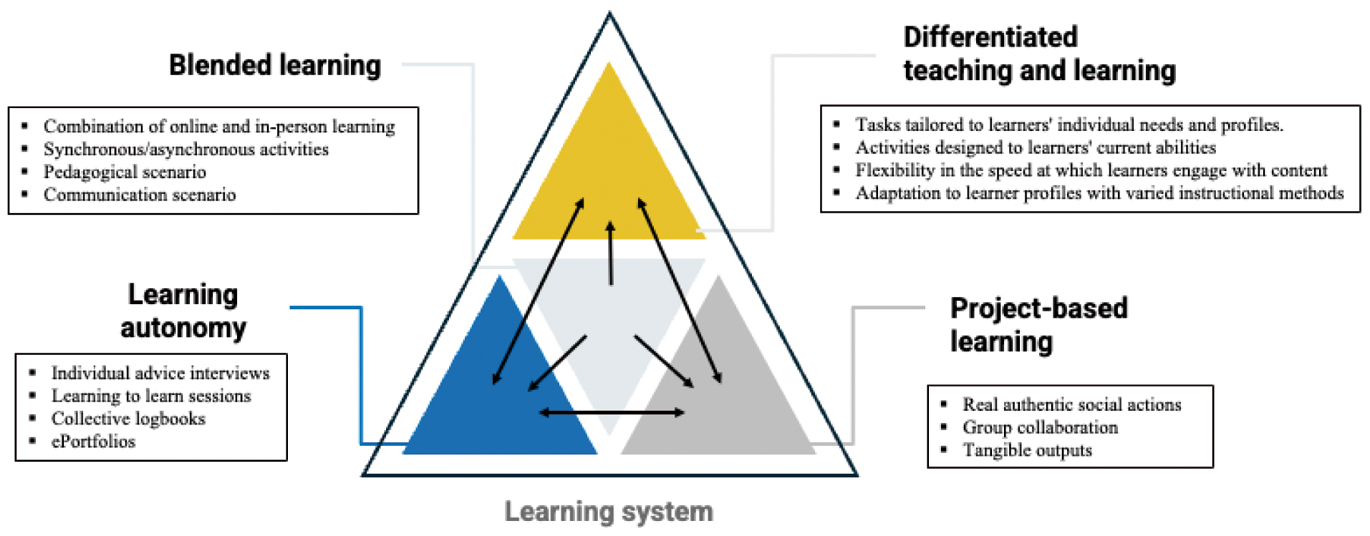

3 Description of the blended learning system for differentiated teaching with the aim of autonomy development

As indicated in the introduction, our learning system is built on four interconnected elements: differentiated teaching, learner autonomy, project-based learning, and blended learning. These elements mutually reinforce one another (Figure 3) as blended learning supports differentiated teaching through personalized pacing and flexible content delivery; project-based learning fosters autonomy by encouraging learners to self-manage tasks and make decisions; differentiated teaching enhances project-based learning by tailoring tasks to individual needs; and autonomy development is strengthened through blended learning tools.

Blended learning system for differentiated instruction fostering learner autonomy.

As part of our project-based pedagogy, we have proposed 4 different project tasks with the aim of offering an optimal challenge. Over the course of the sessions, learners are invited to complete two digital project tasks (among the 4 proposed below) in preparation for a concrete social plan:

Participate in a video pitch competition organized by the doctoral school (AR1[5] and AR3): This activity enables learners to synthesize their research in a concise and impactful way.

Produce a scientific poster on one of the 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals (AR1 and RA2): This task encourages learners to deepen their understanding of global issues and present their work in a visual and informative way for an exhibition.

Participate in the “Je filme ma formation” competition organized by ministry of education (AR2): Learners create a video highlighting their educational journey, enabling them to reflect on their educational experience and share their vision with a wider audience.

Building an interactive map for future international students (AR3): Learners develop an interactive map for publication on the University website. As part of a service-learning approach, this task aims to provide useful resources for welcoming new students.

These digital projects are designed to engage learners and encourage the practical application of their skills. By involving them in real, relevant actions, we aim to ensure that these tasks contribute to reinforcing their autonomy and motivation, while meeting their personal needs.

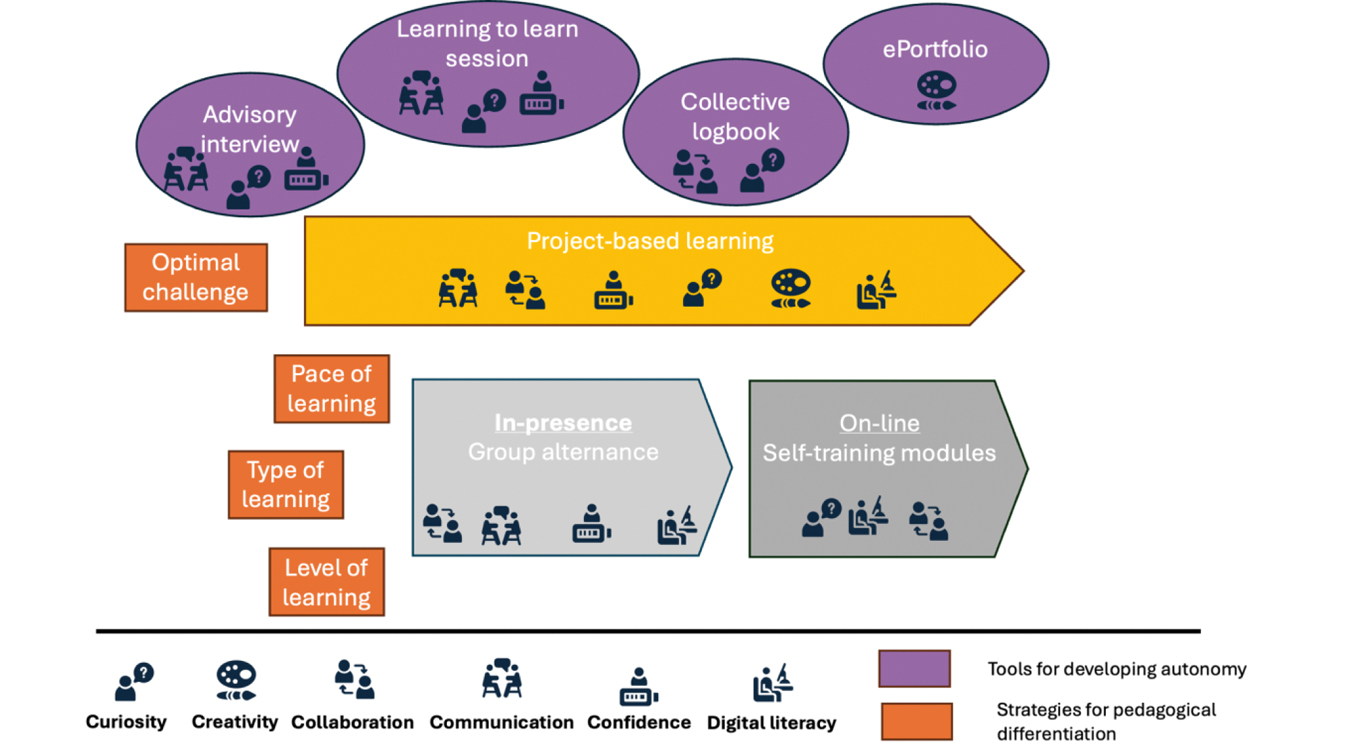

The level of learning is respected by alternating face-to-face groups (same levels/mixed levels) to adapt to learners’ needs, while offering personal pace-of-learning distance rhythms. In addition, the 4 development tools support the type of learning:

Individual advice interviews: These interviews, held at the beginning, middle and end of the course via videoconference, enable learners to receive personalized support. They provide an opportunity to adjust learning objectives, discuss progress and answer learners’ specific questions, while reinforcing their motivation and commitment.

Learning to learn sessions: These weekly face-to-face sessions, held at the beginning or end of the course, aim to develop learners’ metacognitive skills. They help them become more aware of their own learning processes, adopt effective strategies, and improve their autonomy. These sessions also foster a collaborative learning environment.

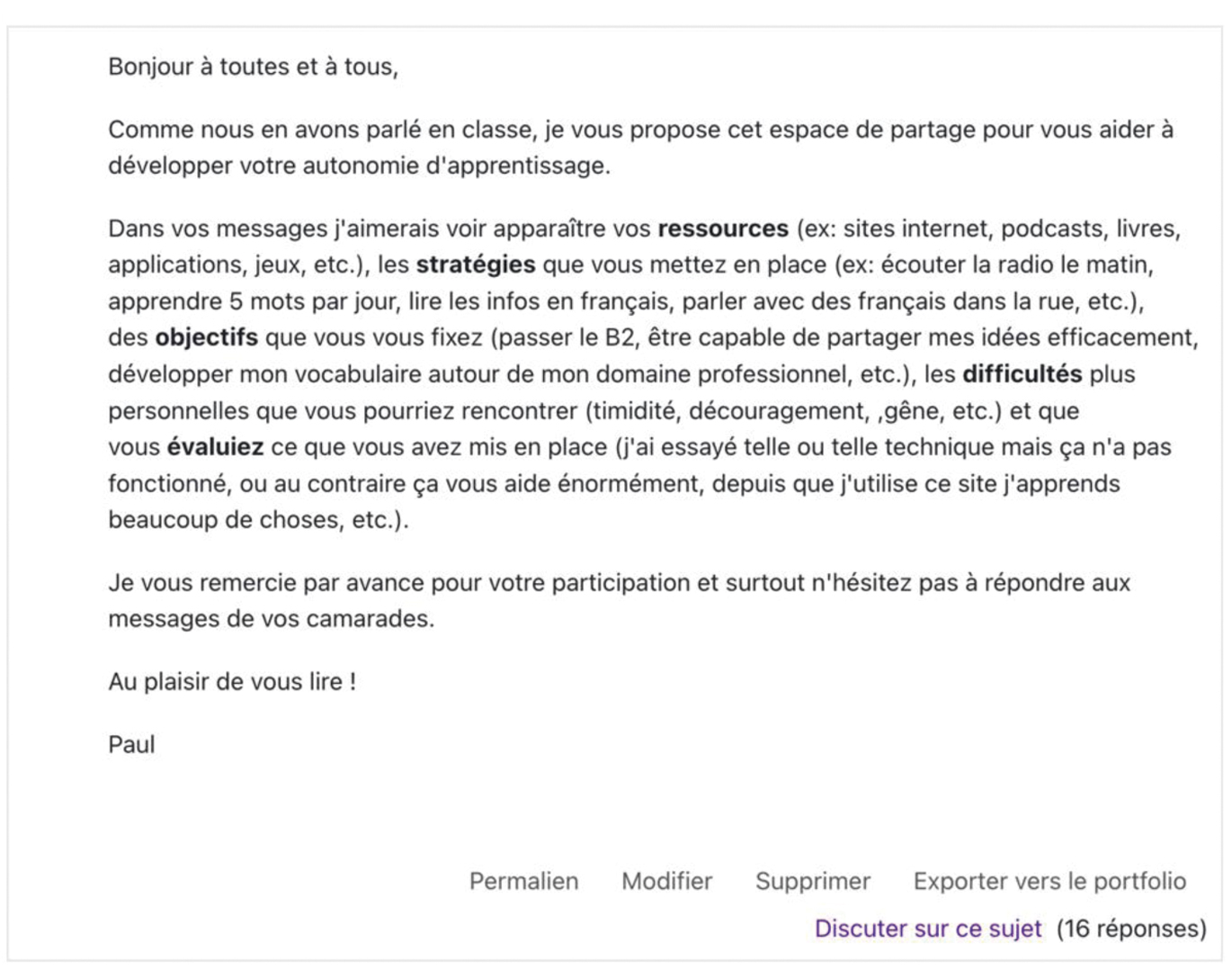

Collective logbooks: Used as a forum on the Moodle platform, these online logs enable learners to share their thoughts, document their progress, and collaborate with their peers (see Appendix 4). They provide an interactive space where learners can discuss challenges, exchange ideas and help each other, contributing to a supportive and engaged classroom dynamic.

ePortfolios: These shared folders, accessible via drive-type tools, enable learners to collect and organize their digital work in one place. ePortfolios facilitate ongoing reflection, self-assessment and the presentation of achievements. They also provide visibility of learners’ skills development for themselves, their teachers, and their peers.

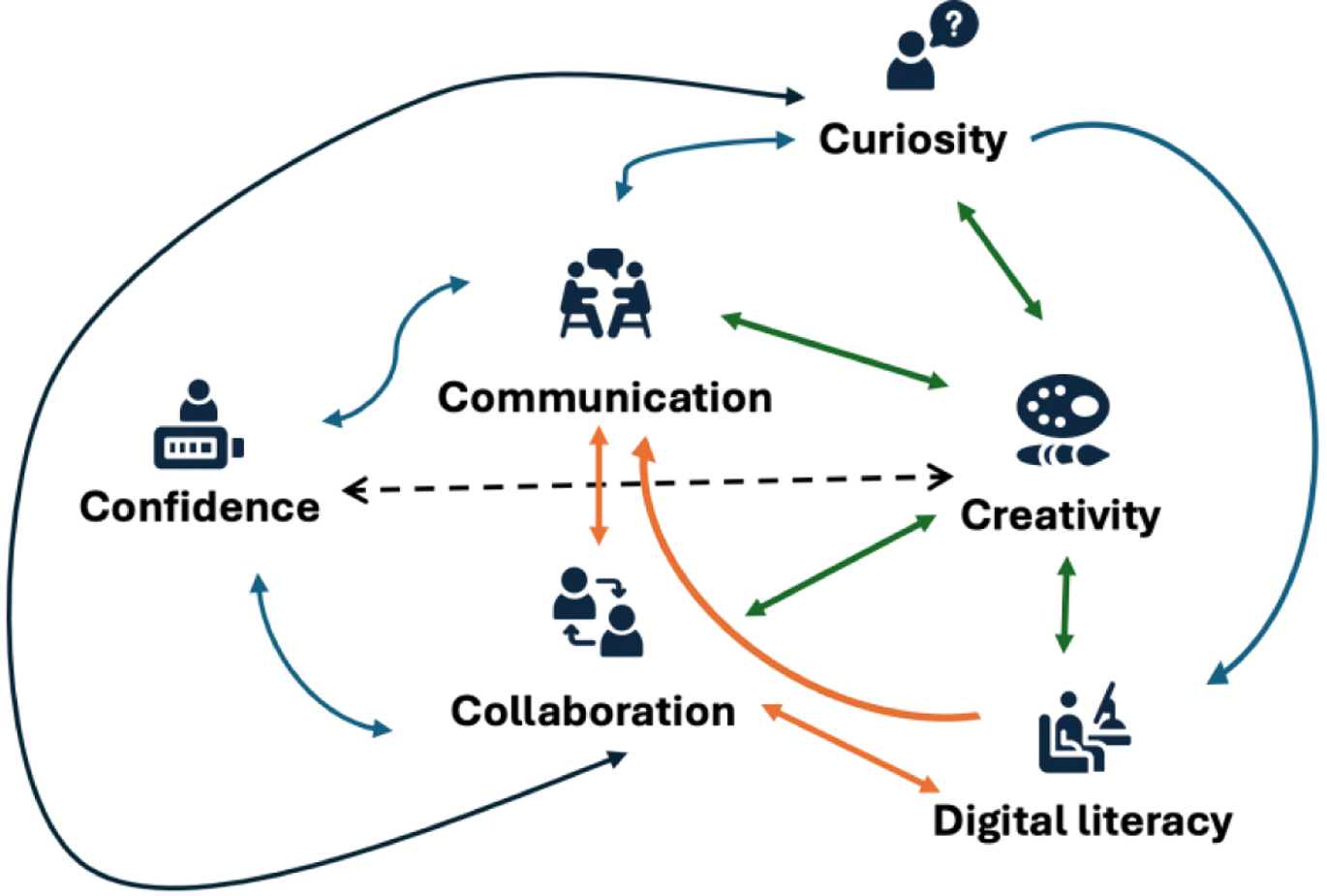

These tools, integrated into the blended learning system, encourage more personalized, interactive and reflective learning, while supporting learner autonomy and collaboration. Learners are encouraged to draw on their transversal competencies to successfully complete the course as illustrated by the schematic representation of the 6 transversal competencies selected and involved in the different elements of the system, as illustrated in Figure 4.

Illustration of the 6 transversal competencies selected and involved in the different elements of the system.

For more details on this system, please refer to Pouzergues Paul’ PhD thesis (Pouzergues 2023).

To investigate how learners perceive and experience the efficacy of this blended learning system in fostering transversal competencies, the following section outlines the research design and data collection methods employed to capture learners’ perspectives and experiences.

4 Methodology

4.1 Data type

Data collection for our study draws on several sources to ensure cross-validation of information. Following Maren’s (2003), methodological framework, the research employs three interconnected types of data that together provide a comprehensive understanding of learner experiences. The first category, invoked data, corresponds to the traces of activities carried out within the blended learning system. These naturally occurring traces include messages recorded in the logbook, recordings of advisory interviews, and learners’ productions, enabling analysis of participants’ behavior and interactions in spontaneous contexts. Induced data takes the form of questionnaires administered at the beginning and end of the course. These questionnaires are designed to gather specific information on learners’ perceptions, attitudes and knowledge before and after the teaching intervention. This method makes it possible to measure learner progress and evaluate the impact of the hybrid system. Data elicited come from “individual comprehension interviews“ (Kaufmann 2016) conducted by teacher-researchers from outside the system. The aim of these interviews is to gather in-depth insights into learners’ experiences, allowing them to express their thoughts, feelings and reflections in detail. The fact that these interviews are conducted by outsiders adds a dimension of objectivity and neutrality to the analysis.

By combining these three types of data, we gain a holistic view of how learners perceive the development of their transversal competencies within the system.

4.2 The corpus

As previously indicated, our action-research (AR) was carried out in three distinct stages, involving three multi-level classes with numbers ranging from 6 to 13 learners (see Appendix 2 1 for a detailed description of the participants and course specifications).

The first stage of action research (now AR1) lasting a total of 30 hours of classes spread over 10 weeks took place in the second semester of the 2020–2021 academic year, with a group of 6 PhD students with levels ranging from A0 to B2. The second stage of action research (now AR2) took place in the first semester of the 2021–2022 academic year, for 40 hours over 7 weeks. This training was offered to a group of 13 learners of Malaysian origin from an exchange program within the Mechanical and Production Engineering department of the Aix-Marseille IUT. Levels for this group ranged from A2 to C1.The third stage (now AR3) took place in the second half of 2021–2022, with a group of 13 learners from a wide variety of backgrounds. As with the first stage, this phase involved 30 hours of training spread over 10 weeks.

The data collected during these three stages form the corpus of our study. It includes questionnaires that were administered during the last class of each course to assess learners’ perceptions (32 questionnaires). Individual advice interviews conducted by videoconference at the beginning and middle of the course were recorded (32 interviews, i.e. 16 hours of recording). Logbook messages were written by learners throughout their training in forums on the university platform (132 messages) with the prompt provided in Appendix 3. Finally, comprehension interviews, as theorised by Kaufmann (2016), constitute a qualitative method aimed at gathering in-depth information while adopting an open, non-directive research posture. The interviews were conducted in French, English, Spanish or Portuguese (depending on the participants’ levels and languages of origin) by external interviewers who were not involved in the teaching, using an interview guide (see Appendix 3). A total of 26 comprehension interviews, covering all students from AR2 and AR3 (n = 26) and representing approximately 13 hours of recording time, were conducted[6].

These varied data help us to provide a solid basis for analyzing the impact of the system on the development of learners’ cross-disciplinary skills in a heterogeneous context.

4.3 Analysis

The analysis adopts an explanatory sequential mixed methods design (Fetters, Curry & Creswell 2013), combining quantitative and qualitative techniques to offer a comprehensive understanding of the data. We first conducted quantitative analysis, followed by qualitative inquiry to explain and contextualize the quantitative findings. The qualitative analysis is based on a content analysis (Bardin 2013) structured around 6 main thematic categories (Paillé & Mucchielli 2016) described in Appendix 1.

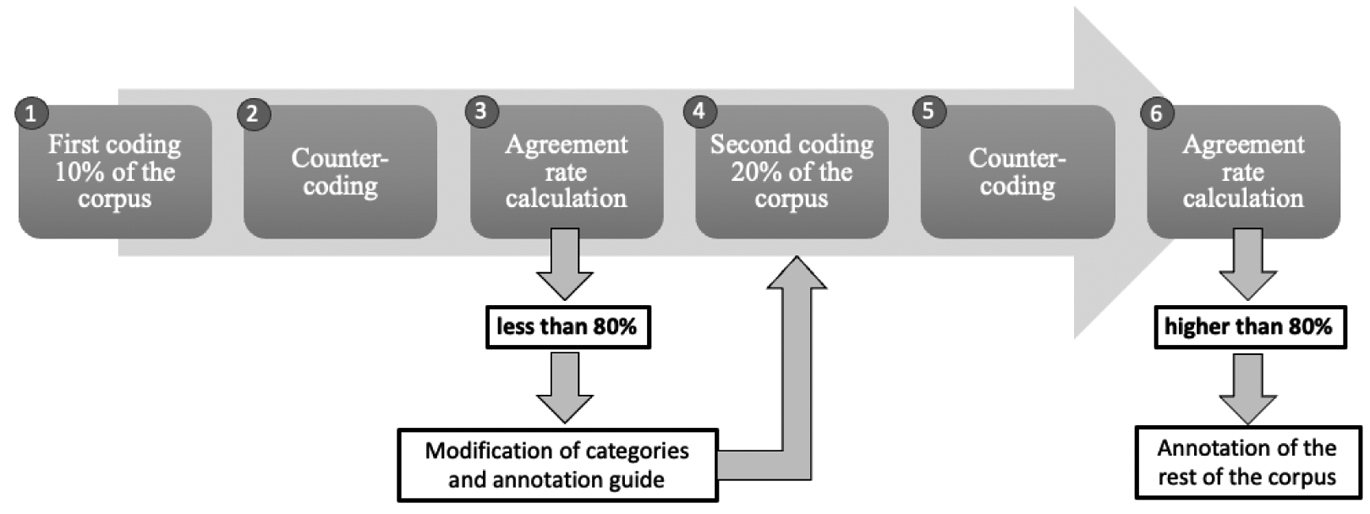

To ensure trustworthiness of the qualitative data, we employed several strategies: we developed a detailed annotation guide (see Appendix 1) to standardize the coding process; we utilized ELAN annotation software (Brugman & Russel 2004) for audio-visual data and Excel software for nominal data, enhancing the systematic organization and analysis of our data; to guarantee the reliability of our coding, we applied double-blind coding (Tellier 2014) on 20 % of the corpus, first coding 10 % of the data, followed by a second coding on another 10 % sample after necessary adjustment as illustrated in Figure 5. The analytic and coding procedures were undertaken by research collaborators external to teaching activities to safeguard the integrity and impartiality of the findings.

Double blind coding stages

This method minimizes potential bias and ensures consistency in the application of thematic categories across the dataset.

This methodological framework enabled us to gather comprehensive data on learners’ perceptions and experiences of transversal competencies development within our blended learning system. The following section presents the findings that emerged from this multi-faceted analysis, organized according to the six transversal competencies identified in our theoretical framework.

5 Results

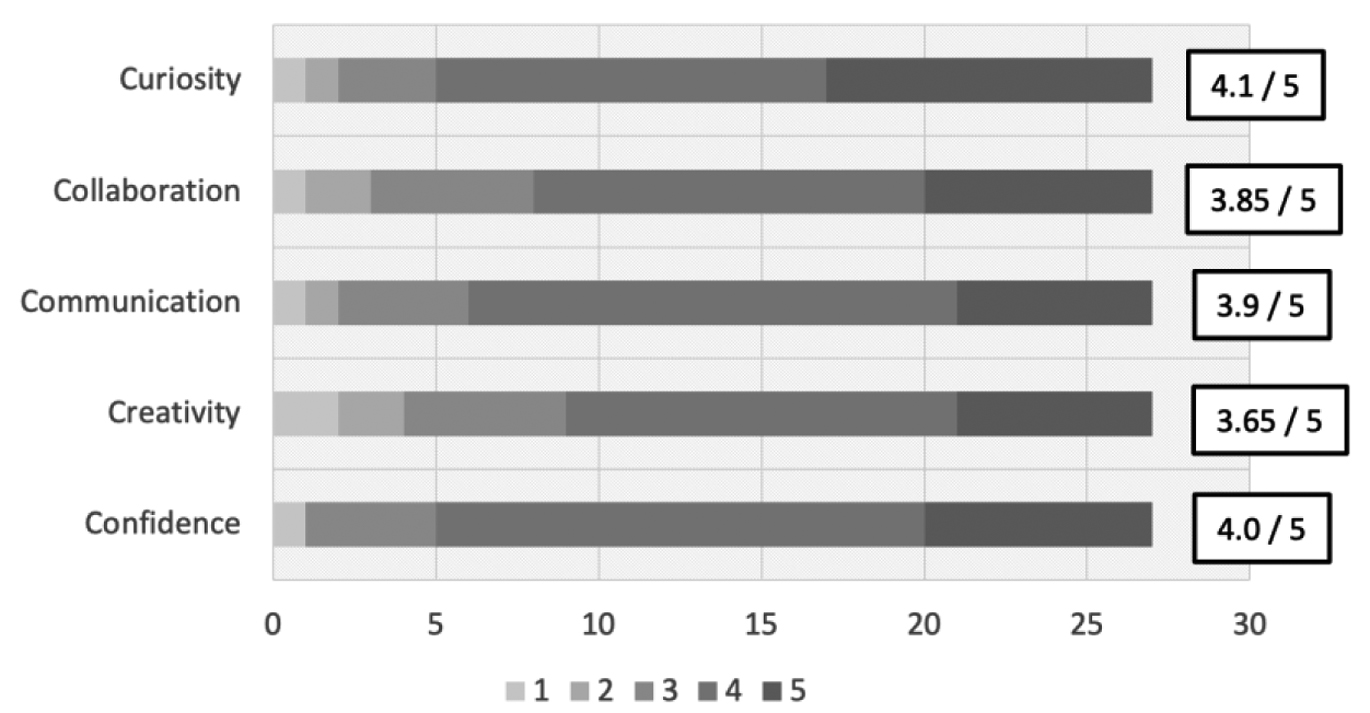

In this results section, the analysis begins by detailing the results obtained for the 6 categories, mentioning in brackets the links that weave between categories. In the discussion section, these links will be highlighted to answer our research question. The following graph shows the learners’ responses in AR2 and AR3, i.e. 26 learners (instead of the 32 who took part in the study). Indeed, it was only after the first stage of action research that the value of assessing the development of learners’ transversal competencies became apparent. The data from the graph will be analyzed over the next 5 sub-sections. A specific graph is shown for digital literacy in sub-section 6.

Self-assessment of learners’ progress in developing transversal competencies Responses to question: Please indicate whether you feel this course has helped you develop any of these skills: (1= no, not at all; 5 = yes, very much).

5.1 Curiosity

As the project progresses, learners progressively opted for a wider variety of learning resources and strategies, in particular to help them carry out the project tasks, which for most of them are a source of curiosity. For Pedro-B2[7], it’s an opportunity to learn more about their field of study, as he notes in his logbook: “There’s also the project to make a video in relation to Mechanical and Productive Engineering. In this project, there are many more opportunities to learn about our subject.”

Moreover, by way of example, the video project enabled Emma-B2 in RA2 to discover that she wished to continue her studies in production engineering at the Lyon Engineering School, as he explains in his comprehension interview:

I learned a lot by making the video, not only about French but also about my future. [Why?] As I did the process in the workshop the welding the bending, to record the video, I found it very interesting for me to do things like that, and I think in the future I’d like to continue my studies in production engineering at the engineering school and I looked, thanks to that, I looked for engineering schools and I found that maybe if it’s possible I’d like to continue at the Lyon engineering school.

Noah-A1 highlights the link between this category, the curiosity of founding new vocabulary, and collaboration (category 2) and communication (category 3): “the fact of making a project between all of us makes more effort, you have to look for words or try to communicate“.

Another important source of curiosity detected within the system is observing the habits of their peers, as illustrated by the following logbook messages. Ming-B1: “The class logbook has been very useful for discovering new ways of learning and sharing them with my friends.”; Asha-A2: “The logbook allowed us to exchange information on ways of learning, as well as being a means of practicing our writing””.

This quest for new forms of learning reflects an open-mindedness and a thirst for learning inherent in curiosity as expressed by Ayo-A2. “From our learning, we have to take a step back to look for YouTube channels to learn something that I needed and didn’t know, and that I had to look for resources online to look for different things to so kind of stimulate curiosity.”

Furthermore, 24 of the 26 learners felt that the system had developed their curiosity, with a total score of 4.1/5; this numerical statistic reinforces our qualitative analysis.

5.2 Collaboration

Teamwork is essential to both differentiated teaching and project-based teaching, two approaches that are intrinsic to our learning system.

Gradually, learners in multi-level classes enrich their learning by drawing on the knowledge of higher proficiency peers and sharing it with peers at lower levels of proficiency, as witnessed by Ayo-A2 “I saw that there were people much more advanced than me and I learnt from that in a way. And I also think that if you’re not that advanced, or if you’re already advanced, the fact that you’re teaching is also a way of learning, you learn even more.”

However, working together is not always easy at first, as was the case for Mei-C1, for whom this was not something he was used to, but it enabled him to learn to be “more patient“ and “to explain“.

Mei-C1 “I think I’m going a bit too fast, but the work [referring to collaborative group work] allows me to be more patient... yes, because you have to explain and I haven’t done that much before, so it’s also a lot of practice, so yes, it’s good”.

For Ben-A2, although sometimes “very difficult”, working together on the project was an experience that she nevertheless enjoyed because it encouraged her to communicate (category 3): “it’s always complicated to work in a group, but I didn’t find it very difficult at times, but I enjoyed it [...] working together on a project makes it harder, we need to find the correct words, try to communicate.”

Luna-B2 also found it a “very good exercise” in her ECN3: “And also the poster is very good because when you work with another person the ideas are totally different but that’s good because you have to discuss [...] And then you have to find an intermediate point between the two ideas of the other person with you and that I think it’s a very good exercise.”

Finally, some consider the development of this transversal competency to be useful “in the future” or in “their career path”, as the following testimonials show:

Arjun-B1: “Personally, I really appreciate the projects and group work that we’ve done throughout our course together. In my opinion, it allows me to benefit from the application of the qualities of work so that I can apply it in my professional career.”; Anna-C1: “For me, I like the project-based activities because they allow us to learn a lot of new things. When we were doing these activities, we used different learning methods that were very interesting, and I think we’ll use them in the future.”

In addition, despite the heterogeneities present, all the learners were able to carry out the project tasks requested, using digital tools (category 6) and demonstrating creativity (category 5).

In terms of quantitative data, 23 of the 26 learners felt that the system had enabled them to develop their ability to collaborate. The total score for this transversal competency is 3.85/5.

5.3 Communication

The various elements of the course lead learners to develop their communication skills in the broadest sense: they must express themselves in front of the class with presentation aids, make videos, write posters and then explain them orally, write messages in the logbook, among other tasks. All these activities provide opportunities to develop their written and oral communication skills. For Luna-ECL-B2 4:20 for example, it enables her to learn to describe herself and her research work “I really like the projects [...] it’s very good because for me it was very complicated to describe myself, with this exercise ... I think [...] I have more fluidity when I talk about myself on my thesis on the things I do before, and so I like it a lot.”

The co-occurrences of this category with categories 1 and 2 show that communicative competence is closely linked to collaboration and confidence, particularly when it comes to speaking, as indicated by student Anna-C1, who believes that by the end of the course she is able to speak in front of many people: “Once in the wile we have to do presentation in front of others and sometimes for me, in the first place I’m very nervous, I was very nervous but as time goes by, and I believe I have improve my French a little, I become more confident and I can speak in front of many people”.

Jian-B1 also appreciates being able to speak in front of an audience, and admits to being less shy: “I particularly like video pitch because I... because I used to practice speaking in front of an audience”.

As in category 1, 24 of the 26 learners felt that the system had improved their communication skills, with a total score of 3.9/5 – a result which supports the findings of our qualitative analysis.

5.4 Confidence

The development of confidence is approached from several angles. The first, mentioned in category 3, is to put learners in front of an audience in an oral production situation during project-related activities, as illustrated by these examples:

Jian -B1: “Through this class I overcome my fear to talk in front of the people because we do the shooting together.”

Jian-B1 “I particularly like video pitch because I... because I used to practice speaking in front of the audience, so I think ... I’m less shy now.”

Mateo-A2 “these activities [project-task] help us a lot to be more confident and make us think before speaking to have a structured speech.”

For Ayo-A2, this was even the most interesting part of the course, as it enabled her to gain confidence in speaking:

The best part of the course was creating the video. [...]I’ve become much more confident when speaking, because when I first came here in the first month, I was afraid of saying something wrong. [...] I think during the course I became much more confident when I spoke, when I asked for something, when I asked for information, when I said something, even if it was wrong, I really relaxed, but during the first week, I think I didn’t say anything because I was afraid of making mistakes.

Another entry discusses the differences in proficiency levels that can help the development of confidence:

Lucas-A2 : “Interacting with people of a higher level gives me extra confidence to say that if I say something and the person who is starting understands me, but also the person who is already advanced understands me and I understand them both equally, it gives me the feeling that I can communicate in an environment that is not simulated, say, what it would be in everyday life.”

A less predictable entry is a comparison linked to the learner’s “culture” as shown by the testimony of Amara-B2. A barrier linked to her imperfect level which, as well as making her “feel guilty and frustrated,” would prevent her from communicating because she feels that her level is not sufficient to be able to communicate freely. But seeing peers at a lower level without this cultural barrier allows her “to get rid of it”, to find the courage to speak, or at least “to try“, despite the imperfection of her oral production skills:

I’m very afraid to speak French ‘parce que je pense que je ne peux pas parler très bien alors je ne veux pas parler’ [because I don’t think I can speak very well, so I don’t want to speak] because in my culture if you do it very terribly it’s not very good thing [...] After 2 years [in France] my French level is very terrible its makes me feel guilty and frustrated to some degrees I just try to get rid of it [...]this class there is some people speaking very good French and some who are just starting like [Ben] A1-A2 and I’m very surprise because people no matter their level they are very happy to express them self in French either the simplest their words for example bonjour and they are super happy [..] so you can still speak French even if you make a lot of mistakes [...] so in my daily life I try to speak French more and more because of this different niveau in the class I get some courage to face the fact that I’m not speaking quite well but I will still try”

Learners gave a positive self-assessment of 4.0/5 for the development of their confidence. There are many comments along these lines, such as Pedro-B2 : “I feel that my level of speaking is better than before and I feel more confident every time I speak”. Only one learner out of 26 felt that the scheme had not enabled them to develop this transversal competency.

Another point worth emphasizing is that some learners said they would like to reinvest in developing this skill, as Mary-C1 indicates the video project (which he called “pitch-talk”) was very useful because it enabled him to take part in a 3-minute competition [certainly referring to the “my thesis in 180 seconds” competition] “in a fluent and organised way”, something he would not have “really dared” to do before this experience:

The Pitch Talk part, talking about myself, what I’ve already done, what I’m doing and the summary is very, very useful because I know that one day I’m going to take part in competitions and the 3-minute Pitch Talk. It is something I didn’t really dare to do before, but now I’ve got the experience, and I can really do it in a fluid and organised way.

5.5 Creativity

Although creativity is the transverse competency with the lowest score (3.65/5) and 4 out of 26 learners answered negatively (below 3), we can observe that, for some learners, the system, particularly through the projects, enabled them to discover their competency as shown by Sofia-B1 “Before this I was never interested to make video like this, because I’m not a very creative person. And when I made this video, it made me think a lot on how to be more creative, and work with other people”.

For others, it has helped them to develop their creativity through the use of a variety of media, as in the case of Ayo-A2: “I think this course has helped me to develop my creativity. Um, I think it encourages us to be more creative, at the best part of the course, when it comes to creating videos, we’ve used the different tools available, video, music, drawings, emojis.”

Furthermore, for Luna-B2, who describes herself as a “creative” person, the scheme enabled her to stimulate her creativity: “I love doing things that involve stimulating creativity, so I really enjoyed editing the video”. A creativity that is also reflected in the quality of her final productions, winner of the “Coup de Coeur” prize in the pitch-video competition[8]. In the three action-research projects, most learners produced work that went beyond their expectations and those of their teacher.

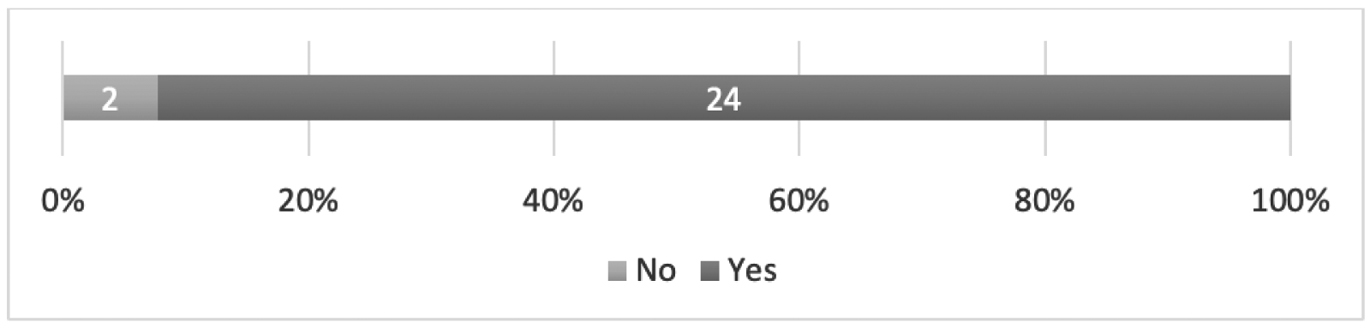

5.6 Digital literacy

As we have shown in the description of the system (see section 3), its operation relies heavily on numerous digital tools (video editing, shared documents, videoconferencing, Moodle platform, etc.) and networks (websites dedicated to learning French, social networks, etc.). Although most learners are already familiar with most of these tools, notably in their personal lives, they feel that they have developed their digital literacy through this system. In fact, in the end-of-course questionnaire in AR2 and AR3, only 2 out of 26 learners replied negatively to the question: “Do you think this course has enabled you to develop your digital skills.” (see Figure 7).

The specific competencies developed vary greatly from one learner to another, but we can see that making and editing videos is one of the areas where they feel they have improved the most; Amara-B2 remarks that “I learned how to make a video through this class ... I never used this tool before.”

Self-assessment of learners’ progress in developing digital literacy Responses to question: Do you think this course has enabled you to develop your digital literacy? Two answers are possible: yes/no.

The use of digital tools proves to be both an enjoyable and rewarding form of learning. When combined with collaboration (Category 2), it enables learners to master “editing tools and software”, as shown by Eva-C1:

I really like the opportunity to create the GMP training video with my mates. It allows me to express my ideas in a new environment, in a new language. It’s quite interesting to see the collaboration between us when we try to produce the script, we had a lot of fun, but at the end of the work, we had a lot of experience with editing tools and software.

For others, the competence enhancement is to be able to collect information in another language (French) about the region where the course takes place (in Aix-en-Provence) or in another country, such as for Mei-C1: “the project (interactive map) enables me to learn how to gather information”.

Another remarkable improvement is the increasing use of shared documents. Although these tools were imposed in the first sessions, we can see that the learners, who for the most part did not use them previously, are now adopting this type of document autonomously to carry out numerous tasks (writing their video scripts, drafting the poster, etc.).

This testimonial from Anna-C1, an advanced student, illustrates the benefits of using shared documents for group work:

For example, with [teacher name] we used many shared documents, and we can, all of us, all the members of the group, can do the works at the same time. In Malaysia we didn’t use it so it’s very new to me, and it’s very interesting as we can also correct the mistakes that the others makes so it’s very interesting, and we can exchange easily.

While the preceding analysis examines each transversal competency individually, the findings reveal complex interconnections between competencies that warrant further examination. The following discussion explores these interactions and their implications for addressing our research question.

6 Discussion and conclusion

The results observed in the previous 6 categories show the strong interconnection between them, as illustrated in Figure 8, where each competency reinforces and enhances the others through a dynamic network of relationships. Indeed, as we have seen in the results section, curiosity is stimulated by collaborative projects and communication-related activities. Learners showed a tendency to explore a variety of resources and develop diversified learning strategies to complete project-tasks, which also fosters collaboration and communication.

Creativity manifests itself in learners’ productions, using a variety of media (videos, graphics, drawings, music, etc.). This creativity is often the result of effective collaboration, where learners share their ideas. Confidence was developed mainly through activities requiring communication and collaboration, particularly when carrying out project tasks requiring oral presentations in front of their peers. The learners expressed an improvement in their self-confidence due to the heterogeneities present in the class (both linguistic and cultural). Communication and collaboration, both inseparable and essential in this system, have enabled learners to improve their ability to present their research or more general ideas in a clear, structured way, while boosting their confidence.

We also showed that learners developed their digital literacy by using various technological tools to deliver projects, such as video editing and the use of shared online documents. This competency is closely linked to collaboration and communication, as the use of these tools required group work.

However, certain limitations of this study must be emphasized. Firstly, the size of the sample, limited to 3 stages of action research with 32 learners (26 of whom took part in the questionnaires and comprehension interviews), does not allow us to generalize the results at this stage. Furthermore, self-assessment of competencies may be biased by learners’ subjective perceptions, thus influencing the reliability of the results. Moreover, the absence of a control group makes it difficult to attribute observed progress directly to the specific system used, as other external factors may have contributed to the development of learners’ skills. Nonetheless, the quantitative and qualitative results show that these competencies are interdependent and mutually reinforcing.

Analysis of the results obtained through the three stages of action research shows that the blended learning system, anchored in a project-based approach, differentiated pedagogy, and the development of learner autonomy, fosters the development of certain transversal competencies in learners.

In particular, the study shows that most learners feel that their competencies in the areas of curiosity, collaboration, communication, confidence, creativity and digital literacy have been significantly enhanced. Indeed, carrying out project tasks using digital tools has stimulated learners’ curiosity and creativity, while encouraging communication and collaboration within multi-level groups. In addition, the numerous opportunities to express themselves in public and to work with peers from different proficiency levels and cultures enabled them to boost their confidence. Finally, the frequent and varied use of technological tools has allowed learners to substantially develop their digital literacy.

Schematic representation of the links between the 6 cross-disciplinary competencies.

A number of limitations need to be considered, including sample size and the absence of a control group, which may limit the generalizability of the results. Self-assessment of competency, while informative, remains subjective and may bias the conclusions.

Despite these limitations, the results suggest that the implementation of a pedagogical system integrating differentiated learning, autonomy development and project-based pedagogy can foster the development of transversal competencies essential to learners’ personal development. Indeed, these competencies are crucial to learners’ adaptability and success in varied and constantly evolving learning environments.

An interesting future line of inquiry would be to evaluate and quantify precisely what elements of the system specifically impact curiosity, collaboration, communication, trust, creativity and digital literacy, or other transversal competencies not studied here, such as empathy and/or adaptability.

The findings of this study provide concrete insights for practitioners by proposing a pedagogical model that combines differentiated learning, autonomy development, and project-based pedagogy. This model is well-suited to heterogeneous contexts and promotes the development of transversal competencies essential for learners’ academic and professional success. For researchers, this study opens avenues to further explore the specific impact of language training systems on the development of transversal competencies.

Appendix

Appendix 1: Annotation guide

Appendix 2: Description of participants and course duration

In order to preserve the anonymity of our learners, we assigned pseudonyms to each participant.

| Stage 1 (AR1) | |||||||

| 30 hours over 10 weeks : 20 hours in class + 10 hours online | |||||||

| Name | Country of Origin | Doctoral School | LC | RC | OP | WP | GL |

| Alexander | Pakistan | Economics | A0 | A0 | A0 | A0 | A0 |

| Layla | Saudi Arabia | Economics | A0 | A0 | A0 | A0 | A0 |

| Noah | Pakistan | Economics | A2 | A2 | A1 | A1 | A1 |

| Grace | Nigeria | Environmental Sciences | A2 | A1 | A1 | A1 | A2 |

| Ayo | Brazil | Environmental Sciences | A2 | B1 | A2 | A2 | A2 |

| Ming | China | Asian Societies & Culture | B1 | B2 | A2 | B2 | B1 |

| Camila | Colombia | Environmental Sciences | B2 | B2 | B2 | B1 | B2 |

| Stage 2 (AR2) | |||||||

| 40 hours over 7 weeks : 22 hours in class + 18 hours online | |||||||

| Name | Country of Origin | School | LC | RC | OP | WP | GL |

| Luna | Malaysia | Mechanical and Production Engineering | B2 | B2 | B1 | B1 | B2 |

| Arjun | B1 | B2 | B1 | B1 | B1 | ||

| Anna | B2 | C1 | B2 | C1 | C1 | ||

| Jian | B1 | B2 | B2 | B1 | B1 | ||

| Eva | B2 | C1 | B2 | C1 | C1 | ||

| Ben | B1 | B2 | A2 | A2 | A2 | ||

| Sofia | B1 | B2 | B1 | B1 | B1 | ||

| Asha | B1 | B1 | A2 | A2 | A2 | ||

| Emma | B2 | B1 | B2 | B2 | B2 | ||

| Zoe | B2 | B2 | B1 | B1 | B1 | ||

| Mei | C1 | B2 | C1 | C1 | C1 | ||

| Patricia | B1 | B1 | B1 | B1 | B1 | ||

| Pedro | B2 | B2 | B1 | B1 | B2 | ||

| Stage 3 (AR3) | |||||||

| 30 hours over 10 weeks : 20 hours in class + 10 hours online | |||||||

| Name | Country of Origin | Status / School | LC | RC | OP | WP | GL |

| Camila | Colombia | Company | A2 | A2 | A2 | A1 | A1 |

| Dmitri | Russia | Life & Health Sciences | A2 | A2 | A1 | A1 | A1 |

| Lucia | Uruguay | Environmental Sciences | A2 | A2 | A1 | A1 | A1 |

| Lucas | United States | Individual | A2 | A2 | A2 | A1 | A2 |

| Mateo | Brazil | Individual | A2 | B1 | A2 | A2 | A2 |

| Nicole | Brazil | Individual | A2 | B1 | A2 | A2 | A2 |

| Alice | Brazil | Individual | B2 | B2 | B1 | A2 | B1 |

| Eva | Brazil | Environmental Sciences | B1 | B2 | B1 | B1 | B1 |

| Diego | Colombia | Engineering Sciences | B2 | B2 | B2 | B2 | B2 |

| Amara | China | Spaces, Cultures, Societies | B2 | B2 | B1 | B2 | B2 |

| Fati | Mauritania | Individual | B2 | B2 | B2 | B1 | B2 |

| Mary | China | Engineering Sciences | B2 | C1 | B2 | B1 | C1 |

| Amir | Iran | Math & Computer Science | C1 | C1 | B2 | B1 | C1 |

Legend:

LC = Listening Comprehension

RC = Reading Comprehension

OP = Oral Production

WP = Written Production

GL = General Level

Appendix 3: Comprehension interview guide

1. Heterogeneous class:

You were in a multi-level class. Was this a problem for you?

Was it an advantage or a disadvantage?

In your opinion, was the course adapted to a multi-level class?

Do you feel you made progress? If so, in which competencies?

Did the course meet your specific needs?

2. The course:

a. General assessment:

Was this a regular course for you?

What was new?

What did you particularly like or dislike?

b. The tools:

What did you think of:

– the logbook

– learning to learn sessions

– advice interviews

Were they useful for you?

What did they bring you?

c. Projects:

– The video pitch

– The collaborative interactive map

Did they help you make progress? open the discussion

d. Collaborative work:

It seems to me that you have often worked in groups, in pairs or threes.

What do you think of this?

Was it useful for you?

Do you think it helped you to develop your oral production and comprehension?

Did you enjoy working with all your classmates? Yes/No

Why or why not?

3. Transversal competencies

Do you think this course has helped you to develop your digital competencies? Yes/No

If yes, which ones? Which tools?

More generally, do you think this course has helped you to develop soft skills such as:

– Creativity

– Confidence

– Collaboration

– Curiosity

– Communication skills

If so, why or how? Please give examples.

Appendix 4: Example of the first logbook message

Traduction :

Hello everyone,

As we discussed in class, I am offering this sharing space to help you develop your learning autonomy.

In your messages, I would like to see your resources (e.g., websites, podcasts, books, apps, games, etc.), the strategies you implement (e.g., listening to the radio in the morning, learning 5 words a day, reading the news in French, talking with French people in the street, etc.), the goals you set for yourself (e.g., passing the B2 exam, being able to share your ideas effectively, developing vocabulary related to your professional field, etc.), the more personal challenges you might face (e.g., shyness, discouragement, discomfort, etc.), and how you evaluate what you have implemented (e.g., “I tried this or that technique but it didn’t work,” or conversely, “It helped me a lot; since I started using this site, I’ve been learning a lot,” etc.).

Thank you in advance for your participation and don’t hesitate to respond to your classmates’ messages.

Looking forward to reading you!

References

Albero, Brigitte. 2003. L’autoformation dans les dispositifs de formation ouverte et à distance: Instrumenter le développement de l’autonomie dans les apprentissages. Les TIC au cœur de l’enseignement supérieur, 139–159. Laboratoire Paragraphe, Université Paris VIII-Vincennes-St Denis.Suche in Google Scholar

Almulla, Mohammed Abdullatif. 2020. The effectiveness of the project-based learning (PBL) approach as a way to engage students in learning. Sage Open 10(3). 2158244020938702. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244020938702.10.1177/2158244020938702Suche in Google Scholar

Bardin, Laurence. 2013. L’analyse de contenu. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. https://doi.org/10.3917/puf.bard.2013.01.10.3917/puf.bard.2013.01Suche in Google Scholar

Brugman, Hennie & Albert Russel. 2004. Annotating multi-media/multi-modal resources with ELAN. In Maria Teresa Lino, Maria Francisca Xavier, Fátima Ferreira, Rute Costa & Raquel Silva (eds.), Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC’04), Lisbon, Portugal: European Language Resources Association (ELRA).Suche in Google Scholar

Calero López, Inmaculada & Beatriz Rodríguez-López. 2020. The relevance of transversal competences in vocational education and training: A bibliometric analysis. Empirical Research in Vocational Education and Training 12(1). 12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40461-020-00100–0.10.1186/s40461-020-00100-0Suche in Google Scholar

Cappellini, Marco, Tim Lewis & Annick Rivens Mompean. 2017. Learner autonomy and Web 2.0 (Advances in CALL Research and Practice). Sheffield & Bristol: Equinox.10.3138/9781781795989Suche in Google Scholar

Coffey, Simon Joseph. 2018. Differentiation in theory and practice. In Maguire, M., Skilling, K., Glackin, M., Gibbons, S., & Pepper, D. (eds.), Becoming a teacher, 5th edn., 187–201. Milton Keynes: Open University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

David, Catherine. 2013. L’agir enseignant en classe de FLE multilingue et multi-niveaux en milieu homoglotte. Nice: Aix Marseille Université dissertation.Suche in Google Scholar

Fetters, Michael D., Leslie A Curry & John W Creswell. 2013. Achieving integration in mixed methods designs—Principles and practices. Health Services Research 48(6 Pt 2). 2134–2156. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475–6773.12117.10.1111/1475-6773.12117Suche in Google Scholar

Graham, Charles R., & Lisa R Halverson. 2022. Blended learning research and practice. In Olaf Zawacki-Richter & Insung Jung (eds.), Handbook of open, distance and digital education, 1–20. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-0351-9_68–1.10.1007/978-981-19-0351-9_68-1Suche in Google Scholar

Holec, Henri (ed.). 1979. Autonomie et apprentissage des langues étrangères. Strasbourg: Conseil de l’Europe.Suche in Google Scholar

Kahn, Sabine (ed.). 2010. Pédagogie différenciée (Le point sur... Pédagogie). Bruxelles: De Boeck.Suche in Google Scholar

Karsenti, Thierry, Daniel Robichaud, Bryn Williams-Jones & Normand Roy (eds.). 2020.Référentiel des compétences transversales favorisant l’intégration professionnelle des étudiants aux cycles supérieurs. Montréal: Université de Montréal.Suche in Google Scholar

Kaufmann, Jean-Claude (ed.). 2016.L’entretien compréhensif. Paris : Armand Colin.Kohonen, Viljo & Gerard Westhoff. 2001. Enhancing the pedagogical aspects of the European Language Portfolio. Strasbourg: Conseil de l’Europe.Suche in Google Scholar

La Scala, Jérémy, Graciana Aad, Isabelle Vonèche-Cardia & Denis Gillet. 2022. Developing transversal skills and strengthening collaborative blended learning activities in engineering education: A pilot study. In 2022 20th International Conference on Information Technology Based Higher Education and Training (ITHET), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1109/ITHET56107.2022.10031948.10.1109/ITHET56107.2022.10031948Suche in Google Scholar

Larsen-Freeman, Diane. 2013. Complexity theory: A new way to think. Revista Brasileira de Linguística Aplicada 13(2). 369–373. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1984–63982013000200002.10.1590/S1984-63982013000200002Suche in Google Scholar

Little, David. 2007. Language learner autonomy: Some fundamental considerations revisited. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching 1(1). 14–29. https://doi.org/10.2167/illt040.0.10.2167/illt040.0Suche in Google Scholar

Mangenot, François. 2008. La question du scénario de communication dans les interactions pédagogiques en ligne. In Journées communication et apprentissage instrumenté en réseaux, 13–26. Paris: Hermès-Lavoisier.Suche in Google Scholar

Maren, Jean-Marie Van Der. 2003. La recherche appliquée en pédagogie. Bruxelles: De Boeck Supérieur.Suche in Google Scholar

Matsuda, Paul Kei. 2006. The myth of linguistic homogeneity in U. S. college composition. College English 68(6). 637–651. https://doi.org/10.58680/ce20065042.10.58680/ce20065042Suche in Google Scholar

Nissen, Elke. 2019. Formation hybride en langues : articuler présentiel et distanciel (Collection Langues & Didactique). Paris: Les Éditions Didier.O’Byrne, W. Ian & Kristine E. Pytash. 2015. Hybrid and blended learning. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy 59(2). 137–140. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaal.463.10.14375/NP.9782278094011Suche in Google Scholar

Paillé, Pierre & Alex Mucchielli (eds.). 2016. L’analyse qualitative en sciences humaines et sociales. Paris: Armand Colin.10.3917/arco.paill.2016.01Suche in Google Scholar

Pouzergues, Paul. 2022. Multilevel courses and blended learning – tools for pedagogical differentiation and promoting student autonomy. European Journal of Applied Linguistics (EUJAL). https://doi.org/10.1515/eujal-2022–0007.10.1515/eujal-2022-0007Suche in Google Scholar

Pouzergues, Paul & Marco Cappellini. 2022. La classe multi-niveaux et la pédagogie différenciée dans un cours hybride. Des leviers pour l’autonomisation des apprenants. Le Français Dans Le Monde (FDLM), Recherche et applications 72–83.Suche in Google Scholar

Pouzergues, Paul. 2023. Mise en place d’une formation hybride en langue pour la prise en compte des hétérogénéités en classe de FLE multi-niveaux : Analyse d’un dispositif de différenciation pédagogique à visée autonomisante. Phdthesis, Aix Marseille Univ, CNRS, LPL. https://hal.science/tel-04418830.Suche in Google Scholar

Robbes, Bruno. 2009. La pédagogie différenciée : Historique, problématique, cadre conceptuel et méthodologie de mise en œuvre. Revue française de pédagogie, XXXVIII(4), pp XX-XX.Suche in Google Scholar

Sá, Maria José & Sandro Serpa. 2018. Transversal competences: Their importance and learning processes by higher education students. Education Sciences 8(3). 126. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci8030126.10.3390/educsci8030126Suche in Google Scholar

Sagarra, Nuria & Gabriela C. Zapata. 2008. Blending classroom instruction with online homework: A study of student perceptions of computer-assisted L2 learning. ReCALL 20(2). 208–224. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0958344008000621.10.1017/S0958344008000621Suche in Google Scholar

Starck, Sylvain & Ioana Boancă. 2019. Édito – Les compétences transversales : une notion et des usages qui interrogent. Recherches en éducation (37).10.4000/ree.790Suche in Google Scholar

Tardif, Jacques & Bruno Dubois. 2013. De la nature des compétences transversales jusqu’à leur évaluation : une course à obstacles, souvent infranchissables. Revue française de linguistique appliquée XVIII(1). 29–45. https://doi.org/10.3917/rfla.181.0029.10.3917/rfla.181.0029Suche in Google Scholar

Tardif, Jacques, Gilles Fortier & Clémence Préfontaine (2006). L’évaluation des compétences : documenter le parcours de développement. Montréal: Chenelière-éducation. Suche in Google Scholar

Wilson, Kate & Linda Devereux. 2014. Scaffolding theory: High challenge, high support in academic language and learning (ALL) contexts. Journal of Academic Language and Learning 8(3). A91–A100. Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.