Point-of-care creatinine testing for kidney function measurement prior to contrast-enhanced diagnostic imaging: evaluation of the performance of three systems for clinical utility

-

Beverly Snaith

, Martine A. Harris

, Bethany Shinkins

, Marieke Jordaan

und Andrew Lewington

Abstract

Background:

Acute kidney injury (AKI) can occur rarely in patients exposed to iodinated contrast and result in contrast-induced AKI (CI-AKI). A key risk factor is the presence of preexisting chronic kidney disease (CKD); therefore, it is important to assess patient risk and obtain kidney function measurement prior to administration. Point-of-care (PoC) testing provides an alternative strategy but there remains uncertainty, with respect to diagnostic accuracy and clinical utility.

Methods:

A device study compared three PoC analysers (Nova StatSensor, Abbott i-STAT and Radiometer ABL800 FLEX) with a reference laboratory standard (Roche Cobas 8000 series, enzymatic creatinine). Three hundred adult patients attending a UK hospital phlebotomy department were recruited to have additional blood samples for analysis on the PoC devices.

Results:

The ABL800 FLEX had the strongest concordance with laboratory measured serum creatinine (mean bias=−0.86, 95% limits of agreement=−9.6 to 7.9) followed by the i-STAT (average bias=3.88, 95% limits of agreement=−8.8 to 16.6) and StatSensor (average bias=3.56, 95% limits of agreement=−27.7 to 34.8). In risk classification, the ABL800 FLEX and i-STAT identified all patients with an eGFR≤30, whereas the StatSensor resulted in a small number of missed high-risk cases (n=4/13) and also operated outside of the established performance goals.

Conclusions:

The screening of patients at risk of CI-AKI may be feasible with PoC technology. However, in this study, it was identified that the analyser concordance with the laboratory reference varies. It is proposed that further research exploring PoC implementation in imaging department pathways is needed.

Introduction

The use of intravascular iodinated contrast agents is common in diagnostic imaging, but the benefits of their use must be weighed against the potential risk [1]. Patients with preexisting chronic kidney disease (CKD) and other factors, such as diabetes, may be at risk of developing acute kidney injury (AKI) following contrast administration. Contrast-induced AKI (CI-AKI) has been defined as AKI occurring 24–72 h after the intravascular administration of iodinated contrast media that cannot be attributed to other causes [2]. Where the contrast may be one of a number of other additional attributable factors post-intervention, the term post-contrast AKI (PC-AKI) may be more appropriate [3]. To minimise the risk of this potentially fatal complication, several international guidelines [1], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9] recommend patient screening and kidney function testing. In the outpatient setting, the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), calculated from the serum creatinine (SCr), is used to risk stratify patients prior to contrast administration. Historically, most guidelines have traditionally advised that an eGFR below 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 signifies an increased risk of CI-AKI triggering strategies aimed at optimising volume status with prophylactic oral hydration or intravenous (IV) volume expansion. The highest risk group is considered to be in patients with an eGFR below 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 [1], which may, in some health systems, result in restriction of iodinated contrast altogether. Despite variation in clinical practice internationally [10], [11], [12], [13] regarding the best way to calculate a patients individual risk and which prevention strategies to implement, testing of kidney function prior to administration of iodinated contrast is uniformly accepted as standard practice.

Point-of-care (PoC) testing for kidney function is an attractive method for providing a rapid result, particularly in the emergency department, acute medical unit or critical care setting where there is a need to make immediate decisions regarding treatment. With ever increasing demands on health services globally, it has been explored as a strategy to ensure patient safety before the administration of contrast media [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25]. However, the literature reveals both disparity in clinical concordance with the central laboratory and the clinical utility of PoC in clinical practice and adoption has therefore been limited [10]. Importantly, even where they are available in diagnostic imaging departments, such devices have not been widely integrated into the clinical pathway. There remains an important need to formally evaluate the role of PoC testing in terms of accuracy, clinical feasibility and health economic benefits.

Aims of this investigation

This Bias Estimation of Point of Care Creatinine (BEPoCC ISRCTN 18805212) study sought to compare the performance of 3 CE-marked PoC analysers against a reference laboratory standard to confirm the accuracy of kidney function categorisation and assess their validity for clinical decision making in diagnostic imaging.

Materials and methods

Study participants

Over a 6-week period in September and October 2016, consecutive adult outpatients (≥18 years) attending a UK hospital phlebotomy department for routine Urea and Electrolytes (U&E) blood tests were approached. No upper age limit was adopted, but pregnant individuals and those unable to consent were excluded.

Following consent, participants completed a screening questionnaire based on previous studies [22], [26], [27] to examine patients kidney risk status and stratify the sample into low and high risk groups based on their co-morbidities and medication. This stratification method ensured the study sample comprised patients with a range of kidney function levels to ensure applicability to a diagnostic imaging setting. The PoC results were not reported to the referring clinician and did not influence any clinical decisions. Demographics, including age, gender and race (Afro-Caribbean or not Afro-Caribbean), were collected for each participant.

Method agreement is a question of estimation, not hypothesis testing. In this scenario, there is no ‘minimum’ sample size required. The confidence interval for 95% limits of agreement is ±1.96 √(3/n)s, where n is the sample size and s is the standard error [28]. Therefore, a sample size of 300 provides a 95% CI of approximately ±0.2s.

Ethics

The research complied with all the relevant regulations and institutional policies, and it ran in accordance with the tenents of the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval for the study was granted by South East Scotland Research Ethics Committee (IRAS:202240), and all participants gave written informed consent. The study was adopted onto the NIHR portfolio (CPMS ID: 31955).

Blood sampling

The standard U&E blood sample was collected by an experienced phlebotomist and processed following local operating procedures. To ensure minimal patient intervention, an additional sample of blood was immediately collected from the same venous puncture site. The whole blood research sample (S-Monovette Lithium Heparin 2.7 mL tube, Ref 05.1553; Sarstedt, Numbrecht, Germany) was labelled with a unique study identifier and transferred to the on-site laboratory for analysis.

Capillary blood sampling was subsequently performed from the fingertip of each participant by two research radiographers (BS and MAH), as would be the case in routine practice. The skin was pierced with a spring-loaded lancet and the sample collected directly onto the analysis strip avoiding squeezing of the finger or milking of blood.

Phlebotomy and laboratory staff were unaware of the patients’ eGFR, reference method results and other PoC results at the time of sample collection and analysis. Where there was incomplete data, i.e. results not available across all methods, the participants were excluded from the sample.

Test methods

The reference standard was Roche Modular IDMS calibrated enzymatic creatinine analysis, performed on serum samples on a Cobas8000 platform (Roche, Inc., Mannheim, Germany). During the study period,for the five creatinine analysers on the reference laboratory platform, the between-run imprecision was determined using independent commercially available QC materials, the standard practice in the laboratory. CVs ranged from 1.3% to 2.1% (median=1.8%) at a concentration of 81 μmol/L, 1.0%–1.4% (median=1.4%) at a concentration of 203 μmol/L and 0.9%–1.3% (median 1.2%) at a concentration of 615 μmol/L.

The CE-marked PoC analysers were the StatSensor (Nova Biomedical, Waltham, MA, USA) and i-STAT (Abbott Laboratories, Princeton, NJ, USA), both handheld devices in current use in UK imaging departments and the ABL800 FLEX (Radiometer, Brønshøj, Denmark), a benchtop analyser. Capillary blood samples were analysed on the StatSensor in the phlebotomy department. Due to the larger volume requirements, whole blood samples were analysed on the i-STAT and ABL800 FLEX devices, which were situated in the laboratory due to space constraints. Each PoC analyser uses a creatinine method based on the amperometric detection of H2O2 generated by three enzyme cascade reactions and expresses plasma calibrated patient results. To avoid interdevice variation, a single analyser was used from each manufacturer for the duration of the study. Quality control (QC) was performed daily during the research using the manufacturers’ quality control materials and limits of acceptability for imprecision.

The laboratory SCr result was confirmed from the hospital order communication system, as in routine practice. The PoC whole blood creatinine (WBCr) result was documented for each participant. No offset adjustment was applied for PoC measurements. All results were transcribed into the EDGE research management system (University of Southampton, UK Version 2.0.28) and exported to Excel® (Microsoft Corporation) for initial analysis. For consistency, the eGFR for all PoC devices were derived using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation [29], taking account of race and gender. In addition, the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) study equation [30] was also used to calculate an alternative eGFR level for comparison.

Statistical analysis

In the absence of repeated patient sample measurements from each PoC device, imprecision, expressed as coefficient of variation (CV), was calculated based on the daily analysis of quality control material. We report the mean, standard deviation (SD) and range across the patient samples for each device. We also report, and illustrate using Bland-Altman plots, the mean bias of the PoC devices relative to the laboratory reference standard along with the 95% limits of agreement for the differences. Passing-Bablok regression analyses explore the presence of proportional and constant error for each of the three devices (from the slope and intercept coefficient, respectively). This approach does not assume that any measurement error in either the laboratory or PoC measurements is normally distributed.

Total analytical error was calculated in line with Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) recommendations [31]:

where

The eGFR results calculated using the CKD-EPI equation were categorised according to the associated risk of CI-AKI [1] using predefined categories (high risk, ≤30; moderate, 31–59; low, ≥60). Overall clinical concordance was calculated as the number (%) of samples falling into the same CI-AKI risk category as that derived from the laboratory method. To evaluate clinical utility, eGFR values calculated from PoC devices were also compared to the laboratory derived eGFR values through error grid analysis [33], which visually demonstrates a scatter plot of both methods into clinically relevant areas.

The analyses and plots were generated using the Analyse-It add-in (Analyse-it Software Ltd, Leeds, UK) for Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, USA) and the statistical software package R (The R Foundation, https://www.r-project.org/).

Results

Quality control/device imprecision

The daily QC confirmed that all measurements were within the ranges given by the manufacturer for each device prior to analysis of participant samples (Table 1). Variation in the number of QC samples analysed relates to automatic daily QC with the ABL800 FLEX and manual QC for the handheld analysers on recruitment days only.

Summary of PoC quality control replication data.

| QC sample | i-STAT | StatSensor | ABL800 FLEX | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level 1 | Level 3 | Level 1 | Level 3 | Level 1 | Level 2 | High | |

| Reference mean (range)a | 380 (309–451) | 44 (09–80) | (44–124) | (398–663) | (211–291) | (21–37) | 1500 |

| Mean, μmol/L | 384.9 | 47.6 | 80.9 | 496.5 | 243.8 | 29 | 1547.8 |

| SD, μmol/L | 9.3 | 2.4 | 6.4 | 35.8 | 3.6 | 0.6 | 27.7 |

| CV % | 2.3 | 5 | 7.9 | 7.2 | 1.5 | 2.1 | 1.8 |

| n | 26 | 26 | 25 | 25 | 53 | 54 | 60 |

QC, quality control; CV, coefficient of variation; n, number of samples. aValues supplied by individual manufacturers for their QC materials.

Participant demographics

A total of 363 individuals consented to complete the screening questionnaire. Of these, 63 were subsequently excluded prior to allocation to the relevant study arm, resulting in 300 participants proceeding to intervention (Supplementary Figure 1). The study sample comprised 158 males and 142 females, with 3 individuals (1.0%) defining their race as Afro-Caribbean. The age range was 18–92 years with a mean of 60 years (SD±18 years).

The participants were stratified into high (n=200) and low-risk (n=100) arms based on the result of the screening questions. A range of risk factors were identified, including previous abnormal kidney function or kidney disease, older age, hypertension, heart disease, gout, use of anti-inflammatories, chemotherapy or other nephrotoxic drugs and multiple myeloma.

Test failure

A total of five procedural failures were recorded during the study, four with the StatSensor and one with the ABL800 FLEX. No failures were recorded for the i-STAT. In relation to the StatSensor, two of the four failures were due to flow errors during sampling, one was due to the strip not being located correctly and the other related to the machine timing out due to inactivity. In all cases, a second test was successful. The ABL800 FLEX failure was due to an incorrectly sited syringe during processing of the sample. The second attempt to analyse the same sample was completed successfully.

Participant samples

A summary of the creatinine concentrations for each participant sample measured by the laboratory reference standard and each of the 3 PoC devices is reported in Table 2.

Descriptive and method comparison statistics for patient creatinine values (PoC devices compared with the laboratory reference standard).

| Mean (SD) | Range | r | Mean bias (95% CI) | 95% Limits of agreement | Passing-Bablok | Total analytical error | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower (95% CI) | Upper (95% CI) | Constant Error (95% CI) | proportional error (95% CI) | ||||||

| Laboratory reference standard, μmol/L | 92 (34) | 38–302 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| iSTAT, μmol/L | 96 (36) | 35–323 | 0.985 | 3.88 (3.14 to 4.62) | −8.8 (−10.06 to −7.54) | 16.6 (15.30 to 17.82) | −3.289 (−5.029 to −1.572) | 1.079 (1.060 to 1.098) | −6.80 to 14.56 |

| StatSensor, μmol/L | 95 (35) | 44–330 | 0.891 | 3.56 (1.75 to 5.37) | −27.7 (−30.80 to −24.60) | 34.8 (31.72−37.92) | 0.778 (−6.103 to 6.217) | 1.022 (0.957 to 1.103) | −22.75 to 29.87 |

| ABL800 FLEX, μmol/L | 91 (33) | 37–304 | 0.991 | −0.86 (−1.37 to −0.35) | −9.6 (−10.52 to −8.78) | 7.9 (7.06 to 8.81) | −0.046 (−1.000 to 1.538) | 0.992 (0.975 to 1.000) | −8.26 to 6.54 |

All PoC devices demonstrated both positive and negative bias vs. the laboratory results over the range of patient creatinine values measured (Table 2 and Supplementary Figures 2–4). The i-STAT and the StatSensor both demonstrated a small positive average bias, although this was predominantly at higher creatinine with the i-STAT. By contrast, the ABL800 FLEX demonstrated a marginal negative average bias but had the tightest 95% limits of agreement of the three devices.

The constant and proportional error for each PoC device compared to the laboratory reference standard is reported, estimated based on the Passing-Bablok regression models.

Clinical relevance

Calculation of eGFR

The average total error for eGFR calculated from the WBCr measurements for the i-STAT and ABL800 FLEX when compared to those from the laboratory reference standard was less than the desired 10% error goal (5.5% and 5.0%, respectively). The average total error for the StatSensor exceeded this goal (13.6%).

When eGFR results, derived from the reference standard laboratory SCr, were categorised according to the potential risk of CI-AKI and a subsequent need for the initiation of preventative measures, there was variation between the outcomes when using the CKD-EPI and MDRD calculations (Table 3). When risk stratifying into high and moderate vs. low risk, CKD-EPI and MDRD agreed for 94.2% of individuals. In 5% of cases, the MDRD calculations overestimated the risk and therefore would have resulted in unnecessary preventative measures being applied. In the remaining three cases, the risk was underestimated, although the results were close to the cutoff values.

Comparison of the eGFR result from laboratory reference standard serum creatinine using the CKD-EPI and MDRD equations.

| CKD-EPI | MDRD | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | Moderate | Low | Total | |

| High | 12 | 1 | - | 13 |

| Moderate | 1 | 59 | 2 | 62 |

| Low | – | 14 | 211 | 225 |

| Total | 13 | 74 | 213 | 300 |

High, eGFR≤30; moderate, eGFR=31–59; low, eGFR≥60.

Error grid analysis

When identifying patients with an abnormal kidney function (eGFR<60), i-STAT WBCr results and ABL800 FLEX WBCr results showed 98.6% (n=74/75) and 97.3% (n=73/75) concordance respectively with the laboratory SCr results, whereas StatSensor WBCr results showed 89.3% (n=67/75) concordance.

In relation to those at highest clinical risk where contrast may be withheld (eGFR≤30), clinical concordance with the laboratory reference standard the results were similar (i-STAT n=13/13, 100%; ABL800 FLEX n=13/13, 100.0%; StatSensor n=9/13, 69.2%).

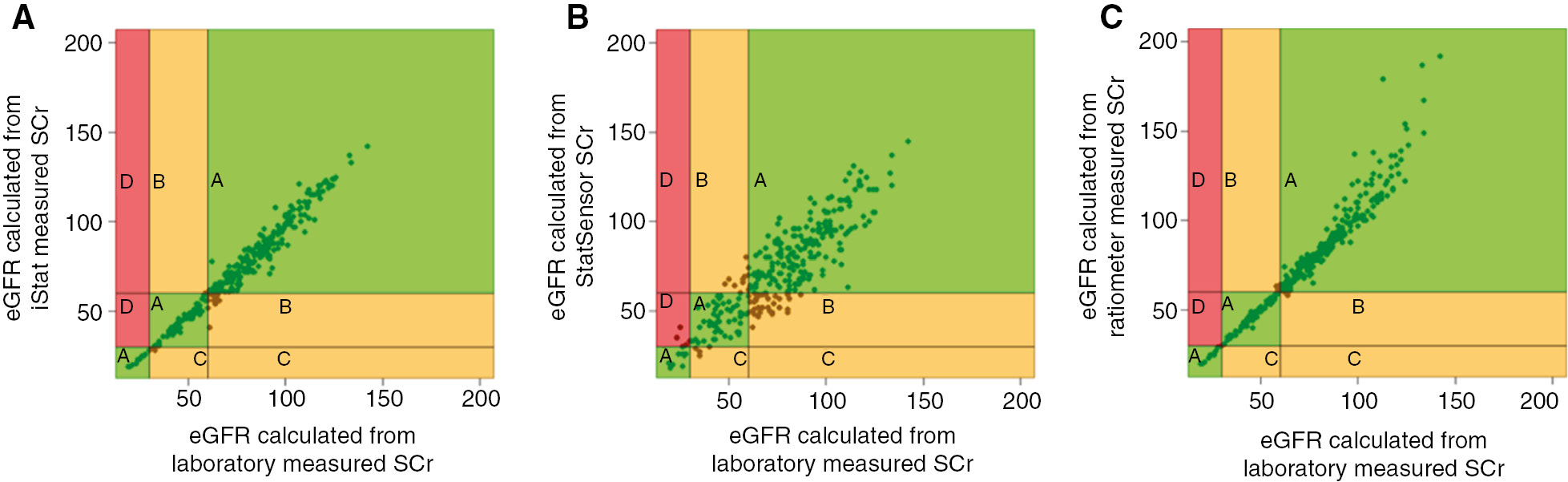

When the CKD-EPI eGFR values were grouped according to the risk of CI-AKI, all PoC devices resulted in the risk of CI-AKI being over- or underestimated in a small number of patients in comparison to the laboratory reference standard (Table 4). Error grids (Figure 1A–C) demonstrate performance zones for risk categorisation based on the CKD-EPI eGFR calculations. The number of participants placed in each zone and the patient management repercussions of risk misclassifications are summarised in Table 4.

Patient management implications of concordance between eGFR risk stratification based on UK guidelines during data collection [1].

| Zone | Implication on management decision | i-STAT no (%) | StatSensor no (%) | ABL800 FLEX no (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Correct risk classification – appropriate management | 282 (94.0) | 250 (83.3) | 297 (99.0) |

| B | Incorrectly classified, but no implication for clinical management | 16 (5.3) | 42 (14.0) | 3 (1.0) |

| C | Incorrect classification, potential for unnecessary prophylaxis or with-holding of contrast | 2 (1.0) | 4 (1.3) | 0 |

| D | Incorrect classification and potential for increased risk of CI-AKI due to insufficient prophylaxis | 0 | 4 (1.3) | 0 |

Error grid analysis of concordance between eGFR risk stratification derived from laboratory measured serum creatinine and 3 POC devices (A)= i-STAT, (B)=StatSensor, (C)=ABL800 FLEX.

Zones relating to patient management repercussions are highlighted and related data is summarised in Table 4.

Discussion

Clinical practice guidelines recommend targeted screening of kidney function based on individual risk [7], [8]. However, due to the silent nature of many forms of kidney disease and complex workflows within diagnostic imaging, it is usual practice for all patients receiving iodinated contrast-enhanced imaging to have had a SCr and eGFR checked prior to the examination [10], [11], [12], [13]. This result establishes whether it is safe for a patient to receive iodinated contrast media and identify if any preventative measures are required or whether contrast media is withheld. It is therefore very important that the kidney function result is available and that this is accurate and reliable. In practice, problems with availability of a kidney function result can lead to significant implications for patients in terms of delay in diagnosis and reduction in service efficiency [10], [15]. These issues may be addressed by the introduction of PoC technology.

The i-STAT and the StatSensor have been evaluated most frequently in the diagnostic imaging literature [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25] and are available in a small number of clinical departments across the UK [10]. The sampling techniques used in this study mirror how they are being used in practice. The results confirm that kidney function testing is feasible on a PoC device, but variation in clinical concordance between the devices tested and the laboratory reference standard was evident similar to previous research [14]. The ABL800 FLEX analyser was the most precise of the three with the lowest total analytical error, closely followed by the i-STAT. The StatSensor fared worst in both categories and failed to identify a small proportion of high-risk patients. The capillary samples were taken by fingerprick, which may have contributed to the analytical error during participant testing. Crucially, this study evaluated clinical performance that establishes whether the test can identify individuals with predefined criteria or conditions within a particular clinical context [34]. In line with other recent studies [14], [17], [22], [24], [35], the ABL800 FLEX or i-STAT may be appropriate for use in this context, whereas the StatSensor results were outside the recommended performance goals for eGFR [32].

The CKD-EPI creatinine equation has been recommended to estimate GFR, using creatinine assays with calibration traceable to the standardised reference material [36]. Our study confirmed previous evidence of variation in eGFR calculation when using the two different equations [37], with overestimation of CI-AKI risk with MDRD in some patients [38], [39]. Although only the laboratory differences are reported, this pattern would be seen across methods. In clinical practice, for PoC devices with an inbuilt eGFR calculator, this confirms the importance of ensuring that the equation used (CKD-EPI or MDRD) is aligned to the local laboratory. Importantly, this also identifies the relevance of cross-laboratory standards where patient results are shared but different calculation standards are used.

This study, which is the first to utilise error grid analysis for eGFR based clinical outcomes, demonstrated that PoC analysers aligned the majority of participant samples to the correct CI-AKI risk category and reassuringly no high-risk cases would have been missed with two of the three PoC devices.

The need for efficient workflow and rapid turn-around of contrast-enhanced diagnostic imaging studies supports the introduction of PoC creatinine testing [15], [22]. However, due to previous concerns around the accuracy of PoC creatinine technology, it is yet to make its way into mainstream use. Further evidence is required of the feasibility and practicality of embedding this technology into clinical practice.

Robustness of findings

This study was conducted in a phlebotomy setting and the patients may not wholly represent those referred for contrast-enhanced imaging. Despite the stratification of participants, only one quarter of samples in the present study demonstrated an abnormal kidney function (eGFR<60); however, this is comparable with other studies [14], [25] and considered a sufficient spread to review the appropriateness of PoC for clinical practice in the diagnostic imaging context.

This was not a formal method evaluation study, as required for introduction into routine practice, but focussed on exploring the clinical impact of using POCT compared to use of the laboratory. The study was limited to the assessment of bias, total error and clinical performance of the devices in relation to creatinine and eGFR. Precision, interference, cross-reactivity, linearity and quantitation limits of PoC analysers have not been investigated and are outside the scope of this study. The analytical goal for total allowable error in creatinine measurements is derived from repeated measurements, which was not possible in this study. The analysis is therefore limited to reporting the total analytical error and the performance goal for eGFR was defined as the key outcome.

Comparisons were made using the recommended CKD-EPI creatinine equation and an IDMS calibrated enzymatic creatinine assay; however, both the MDRD equation and the creatinine assays based on the Jaffe reaction are still being used in a number of laboratories [10]. Concordance between PoC and eGFR determined in these laboratories may differ from our findings.

Procedure failure rates have been reported but other practical factors, such as ease of device maintenance and pros and cons of bedside capillary vs. venous whole blood sampling, were not explored further. The cost of PoC implementation has not been investigated in this study; however, variations in the initial and ongoing costs of devices will vary depending on type (hand held vs. benchtop) and volume of samples analysed [40].

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Mid Yorkshire Hospitals Research Department and Pathology, in particular Paul Walker and the PoC team (Tracey Eastwood, Ebrahim Rawat and colleagues), for equipment oversight and advice. We would like to acknowledge the NIHR Leeds Diagnostic Evidence Cooperative PPI group, Professor Chris Price and members of the Radiology PoC creatinine (RADPoCC) scientific advisory group, particularly Becky Kift.

Author contributions: All the authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this submitted manuscript and approved submission.

Research funding: The project received funding from Yorkshire and Humber Academic Health Science Network (Grant Number: YHP0318). The device manufacturers provided the devices and consumables for use in the study.

Employment or leadership: Dr Michael Messenger, Dr Andrew Lewington and Dr Bethany Shinkins are currently supported by the NIHR Leeds Diagnostic Evidence Co-operative. The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the HTA programme, NIHR, NHS or the Department of Health.

Honorarium: None declared.

Competing interests: The funding organisation(s) played no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the report for publication.

References

1. Royal College of Radiologists. Standards for intravascular contrast administration to adult patients, 3rd ed. London: RCR, 2015.Suche in Google Scholar

2. Andreucci M, Faga T, Pisani A, Sabbatini M, Michael A. Acute kidney injury by radiographic contrast media: pathogenesis and prevention. BioMed Res Int 2014. DOI: 10.1155/2014/362725.10.1155/2014/362725Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

3. van der Molen AJ, Reimer P, Dekkers IA, Bongartz G, Bellin M-F, Bertolotto M, et al. Post-contrast acute kidney injury – Part 1: definition, clinical features, incidence, role of contrast medium and risk factors. Eur Radiol 2018. DOI: 10.1007/s00330-017-5246–5.10.1007/s00330-017-5246–5Suche in Google Scholar

4. The Renal Association, The Bristish Cardiovascular Intervention Society and The Royal College of Radiologists. Prevention of contrast induced acute kidney injury (CI-AKI) in adult patients; 2013.Suche in Google Scholar

5. Canadian Association of Radiologists. Consensus Guidelines for the prevention of contrast induced nepropathy. Ontario, Canada, 2011.Suche in Google Scholar

6. European Society of Urogenital Radiology. ESUR guidelines on contrast media. 2016, Version 9. Available from: http://www.esur.org/esur-guidelines/. Accessed: 27 Sep 2017.10.1007/s00330-016-4673-zSuche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

7. American College of Radiologists. ACR manual on contrast media. 2015, Version 10.Suche in Google Scholar

8. Royal Australian & New Zealand College of Radiologists. Iodinated contrast media guideline. Sydney, 2016.Suche in Google Scholar

9. Kidney Diseases Improving Global outcomes (KDIGO), Acute Kidney Injury Working group. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for acute kidney injury. Kidney Int Suppl. 2012;2:1–138.Suche in Google Scholar

10. Harris MA, Snaith B, Clarke R. Strategies for assessing renal function prior to outpatient contrast-enhanced CT: a UK survey. Br J Radiol 2016;89:20160077.10.1259/bjr.20160077Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

11. Cope LH, Drinkwater KJ, Howlett DC. RCR audit of compliance with UK guidelines for the prevention and detection of acute kidney injury in adult patients undergoing iodinated contrast media injections for CT. Clin Radiol 2017;72:1047–52.10.1016/j.crad.2017.07.002Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Antwi WK, Botwe B, Kyei KA, Arthur L, Manteeba H, Quaicoe B, et al. Determination of creatinine level before administration of intravenous iodinated contrast media at two selected hospitals in Ghana. S Afr Radiogr 2015;53:8–13.Suche in Google Scholar

13. Moos SI, Stoker J, Beenan LF, Flobbe K, Bipat S. The prevention of contrast-induced nephropathy in Dutch hospitals. Neth J Med 2014;71:48–54.Suche in Google Scholar

14. Korpi-Steiner NL, Williamson EE, Karon BS. Comparison of three whole blood creatinine methods for estimation of glomerular filtration rate before radiographic contrast administration. Clin Chem 2009;132:920–6.10.1309/AJCPTE5FEY0VCGOZSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

15. Lee-Lewandrowski E, Chang C, Gregory K, Lewandrowski K. Evaluation of rapid point-of-care creatinine testing in the radiology service of a large academic medical center: impact on clinical operations and patient deposition. Clin Chim Acta 2012;413:88–92.10.1016/j.cca.2011.05.006Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

16. Haneder S, Gutfleisch A, Meier C, Brade J, Hanak D, Schoenberg SO, et al. Evaluation of a handheld creatinine device for real-time determination of serum creatinine in radiology departments. World J Radiol 2012;4:328–34.10.4329/wjr.v4.i7.328Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

17. Morita S, Suzuki K, Masukawa A, Ueno E. Assessing renal function with a rapid, handy, point-of-care whole blood creatinine meter before using contrast materials. Jpn J Radiol 2011;29:187–93.10.1007/s11604-010-0536-8Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Inoue A, Nitta N, Ohta S, Imoto K, Yamasaki M, Ikeda M, et al. StatSensor-I point-of-care creatinine analyser may identify patients at high-risk of contrast-induced nephropathy. Exp Ther Med 2017;13:3505–8.10.3892/etm.2017.4389Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

19. Dimeski G, Tilley V, Jones BW, Brown NN. Which point-of-care analyser for radiology: direct comparison of the i-Stat and StatStrip creatinine methods with different sample types. Ann Clin Biochem 2013;50:47–52.10.1258/acb.2012.012081Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

20. Aumatell A, Sharpe D, Reed W. Validation of the Nova StatSensor creatinine for testing blood before contrast computed tomography studies. Point Care 2010;9:25–31.10.1097/POC.0b013e3181d2d8a5Suche in Google Scholar

21. Karamasis G, Hampton-Till J, Al-Janabi F, Mohdnazri S, Parker M, Ioannou A, et al. Impact of point-of-care pre-procedure creatinine and eGFR testing in patients with ST segment elevation myocardial infarction undergoing primary PCI: The pilot STATCREAT study. Int J Cardiol 2017;240:8–13.10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.03.147Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

22. Too CW, Ng WY, Tan CC, Mahmood MI, Tay KH. Screening for impaired renal function in outpatients before iodinated contrast injection: comparing the Choyke questionnaire with a rapid point-of-care-test. Eur J Radiol 2015;84:1227–31.10.1016/j.ejrad.2015.04.001Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

23. Houben IP, van Berlo CJ, Bekers O, Nijssen EC, Lobbes MB, Wildberger JE. Assessing the risk of contrast-induced nephropathy using a finger stick analysis in recalls for breast screening: the CINFIBS explorative study. Contrast Media Mol Imaging 2017. DOI:10.1155/2017/5670384.10.1155/2017/5670384Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

24. You JS, Chung YE, Park JW, Lee W, Lee H-Y, Chung TN, et al. The usefulness of a rapid point-of-care creatinine testing for the prevention of contrast-induced nephropathy in the emergency department. Emerg Med J 2013;30:555–8.10.1136/emermed-2012-201285Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

25. Carden AJ, Salcedo ES, Tran NK, Gross E, Mattice J, Shepard J, et al. Prospective observational study of point-of-care creatinine in trauma. Trauma Surg Acute Care Open 2016;1:1–4.10.1136/tsaco-2016-000014Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

26. Choyke PL, Cady J, DePollar SL, Austin H. Determination of serum creatinine prior to iodinated contrast media: is it necessary in all patients? Tech Urol 1998;4:65–9.Suche in Google Scholar

27. Ledermann HP, Mengiardi B, Schmid A, Froehlich JM. Screening for renal insufficiency following ESUR (European Society of Urogenital Radiology) guidelines with on-site creatinine measurements in an outpatient setting. Eur Radiol 2010;20:1926–33.10.1007/s00330-010-1754-2Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

28. Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet 1986;1:307–10.10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.10.001Suche in Google Scholar

29. CKD-EPI Calculator for Adults (SI Units). National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Available from: https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/health-communication-programs/nkdep/lab-evaluation/gfr-calculators/adults-si-unit-ckd-epi/Pages/default.aspx. Accessed: 27 Sep 2017.Suche in Google Scholar

30. UK CKD Guide eGFR Calculator. Renal Association. Available from: http://egfrcalc.renal.org/. Accessed: 27 Sep 2017.Suche in Google Scholar

31. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Evaluation of total analytical error for quantitative medical laboratory measurement procedures, EP21, 2nd ed. Wayne, PA: CSLI, 2016.Suche in Google Scholar

32. Myers GL, Miller WG, Coresh J, Fleming J, Greenberg N, Greene T, et al. Recommendations for improving serum creatinine measurement: a report from the Laboratory Working Group of the National Kidney Disease Education Program. Clin Chem 2006;52:5–18.10.1373/clinchem.2005.0525144Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

33. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. How to construct and interpret an error grid for quantitative diagnostic assays; approved guideline EP27-A. 32(12). Wayne, PA: CSLI, 2012.Suche in Google Scholar

34. Varbakel JY, Turner PJ, Thompson MJ, Plüddermann A, Price CP, Shinkins B, Van den Bruel A. Common evidence gaps in point-of-care diagnostic test evaluation: a review of Horizon scan reports. BMJ Open 2017;7:e015760.10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015760Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

35. Naugler C, Redman L. Letter to the editor: comparison of estimated glomerular filtration rates using creatinine values generated by i-STAT and Cobas 6000. Clin Chim Acta 2014;429:79–80.10.1016/j.cca.2013.11.033Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

36. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Chronic kidney disease in adults: assessment and management. 2014. Available from: nice.org.uk/guidance/cg182. Accessed: 19 Oct 2017.Suche in Google Scholar

37. McFadden EC, Hirst JA, Verbakel JY, McLellan JH, Hobbs FD, Stevens RJ, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis comparing the bias and accuracy of the modification of diet in renal disease and chronic kidney disease epidemiology collaboration equations in community-based populations. Clin Chem 2018;64:475–85.10.1373/clinchem.2017.276683Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

38. Matsushita K, Mahmoodi BK, Woodward M, Emberson JR, Jafar TH, Jee SH, et al. Comparison of risk prediction using the CKD-EPI equation and the MDRD study equation for estimated glomerular filtration rate. J Am Med Assoc 2012;307:1941–51.10.1001/jama.2012.3954Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

39. Rootjes PA, Bax WE, Penne WL. Difference in risk assessment for development of contrast-induced acute kidney injury using the MDRD versus CKD-EPI equations to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Eur J Intern Med 2016;36:e33–4.10.1016/j.ejim.2016.08.032Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

40. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Point-of-care creatinine tests before contrast-enhanced imaging. 2018. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/advice/mib136/resources/pointofcare-creatinine-tests-before-contrastenhanced-imaging-pdf-2285963399057605. Accessed: 19 January 2018.Suche in Google Scholar

Supplementary Material:

The online version of this article offers supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2018-0128).

©2018 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorials

- Procalcitonin for diagnosing and monitoring bacterial infections: for or against?

- Is it time to abandon the Nobel Prize?

- In Memoriam

- Norbert Tietz, 13th November 1926–23rd May 2018

- Reviews

- Procalcitonin guidance in patients with lower respiratory tract infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Telomere biology and age-related diseases

- Opinion Paper

- Procalcitonin-guided antibiotic therapy: an expert consensus

- Genetics and Molecular Diagnostics

- mRNA expression profile in peripheral blood mononuclear cells based on ADRB1 Ser49Gly and Arg389Gly polymorphisms in essential hypertension — a case-control pilot investigation in South Indian population

- General Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine

- External quality assessment schemes for glucose measurements in Germany: factors for successful participation, analytical performance and medical impact

- Long-term stability of glucose: glycolysis inhibitor vs. gel barrier tubes

- Observational studies on macroprolactin in a routine clinical laboratory

- Anti-streptavidin IgG antibody interference in anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP) IgG antibody assays is a rare but important cause of false-positive anti-CCP results

- Point-of-care creatinine testing for kidney function measurement prior to contrast-enhanced diagnostic imaging: evaluation of the performance of three systems for clinical utility

- Hematology and Coagulation

- Analytical performance of an automated volumetric flow cytometer for quantitation of T, B and natural killer lymphocytes

- Lupus anticoagulant testing using two parallel methods detects additional cases and predicts persistent positivity

- Reference Values and Biological Variations

- Within-subject biological variation of activated partial thromboplastin time, prothrombin time, fibrinogen, factor VIII and von Willebrand factor in pregnant women

- Within-subject and between-subject biological variation estimates of 21 hematological parameters in 30 healthy subjects

- Immunoglobulin G (IgG) and IgG subclass reference intervals in children, using Optilite® reagents

- Cancer Diagnostics

- Serum carbohydrate sulfotransferase 7 in lung cancer and non-malignant pulmonary inflammations

- Cardiovascular Diseases

- Clinical performance of a new point-of-care cardiac troponin I test

- Diabetes

- Testing for HbA1c, in addition to the oral glucose tolerance test, in screening for abnormal glucose regulation helps to reveal patients with early β-cell function impairment

- Effects of common hemoglobin variants on HbA1c measurements in China: results for α- and β-globin variants measured by six methods

- Infectious Diseases

- Serum procalcitonin concentration within 2 days postoperatively accurately predicts outcome after liver resection

- Predictive value of serum gelsolin and Gc globulin in sepsis – a pilot study

- Cerebrospinal fluid free light chains as diagnostic biomarker in neuroborreliosis

- Letter to the Editor

- Glucose and total protein: unacceptable interference on Jaffe creatinine assays in patients

- Interference of glucose and total protein on Jaffe-based creatinine methods: mind the covolume

- Interference of glucose and total protein on Jaffe based creatinine methods: mind the covolume – reply

- Measuring procalcitonin to overcome heterophilic-antibody-induced spurious hypercalcitoninemia

- Paraprotein interference in the diagnosis of hepatitis C infection

- Timeo apis mellifera and dona ferens: bee sting-induced Kounis syndrome

- Bacterial contamination of reusable venipuncture tourniquets in tertiary-care hospital

- Detection of EDTA-induced pseudo-leukopenia using automated hematology analyzer with VCS technology

- Early adjustment of antimicrobial therapy after PCR/electrospray ionization mass spectrometry-based pathogen detection in critically ill patients with suspected sepsis

- Thromboelastometry reveals similar hemostatic properties of purified fibrinogen and a mixture of purified cryoprecipitate protein components

- Bicarbonate interference on cobas 6000 c501 chloride ion-selective electrodes

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorials

- Procalcitonin for diagnosing and monitoring bacterial infections: for or against?

- Is it time to abandon the Nobel Prize?

- In Memoriam

- Norbert Tietz, 13th November 1926–23rd May 2018

- Reviews

- Procalcitonin guidance in patients with lower respiratory tract infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Telomere biology and age-related diseases

- Opinion Paper

- Procalcitonin-guided antibiotic therapy: an expert consensus

- Genetics and Molecular Diagnostics

- mRNA expression profile in peripheral blood mononuclear cells based on ADRB1 Ser49Gly and Arg389Gly polymorphisms in essential hypertension — a case-control pilot investigation in South Indian population

- General Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine

- External quality assessment schemes for glucose measurements in Germany: factors for successful participation, analytical performance and medical impact

- Long-term stability of glucose: glycolysis inhibitor vs. gel barrier tubes

- Observational studies on macroprolactin in a routine clinical laboratory

- Anti-streptavidin IgG antibody interference in anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP) IgG antibody assays is a rare but important cause of false-positive anti-CCP results

- Point-of-care creatinine testing for kidney function measurement prior to contrast-enhanced diagnostic imaging: evaluation of the performance of three systems for clinical utility

- Hematology and Coagulation

- Analytical performance of an automated volumetric flow cytometer for quantitation of T, B and natural killer lymphocytes

- Lupus anticoagulant testing using two parallel methods detects additional cases and predicts persistent positivity

- Reference Values and Biological Variations

- Within-subject biological variation of activated partial thromboplastin time, prothrombin time, fibrinogen, factor VIII and von Willebrand factor in pregnant women

- Within-subject and between-subject biological variation estimates of 21 hematological parameters in 30 healthy subjects

- Immunoglobulin G (IgG) and IgG subclass reference intervals in children, using Optilite® reagents

- Cancer Diagnostics

- Serum carbohydrate sulfotransferase 7 in lung cancer and non-malignant pulmonary inflammations

- Cardiovascular Diseases

- Clinical performance of a new point-of-care cardiac troponin I test

- Diabetes

- Testing for HbA1c, in addition to the oral glucose tolerance test, in screening for abnormal glucose regulation helps to reveal patients with early β-cell function impairment

- Effects of common hemoglobin variants on HbA1c measurements in China: results for α- and β-globin variants measured by six methods

- Infectious Diseases

- Serum procalcitonin concentration within 2 days postoperatively accurately predicts outcome after liver resection

- Predictive value of serum gelsolin and Gc globulin in sepsis – a pilot study

- Cerebrospinal fluid free light chains as diagnostic biomarker in neuroborreliosis

- Letter to the Editor

- Glucose and total protein: unacceptable interference on Jaffe creatinine assays in patients

- Interference of glucose and total protein on Jaffe-based creatinine methods: mind the covolume

- Interference of glucose and total protein on Jaffe based creatinine methods: mind the covolume – reply

- Measuring procalcitonin to overcome heterophilic-antibody-induced spurious hypercalcitoninemia

- Paraprotein interference in the diagnosis of hepatitis C infection

- Timeo apis mellifera and dona ferens: bee sting-induced Kounis syndrome

- Bacterial contamination of reusable venipuncture tourniquets in tertiary-care hospital

- Detection of EDTA-induced pseudo-leukopenia using automated hematology analyzer with VCS technology

- Early adjustment of antimicrobial therapy after PCR/electrospray ionization mass spectrometry-based pathogen detection in critically ill patients with suspected sepsis

- Thromboelastometry reveals similar hemostatic properties of purified fibrinogen and a mixture of purified cryoprecipitate protein components

- Bicarbonate interference on cobas 6000 c501 chloride ion-selective electrodes