Abstract

Universal Basic Income (UBI) is revolutionary and simple at the same time and elicits both attraction and aversion from the general public. This is one of the reasons why, despite its potential to contribute to some of the most pressing current challenges, UBI has not yet been implemented in any country in the world, at least at a system-wide scale. By drawing on innovation theories and adopting a mixed methods approach, this exploratory study investigates public acceptance of UBI in Spain. This study contributes to the emerging literature on public opinion on a UBI as well as to the field of innovation of public policies.

1 Introduction

Universal basic income (UBI) is “a regular transfer in cash to every individual irrespective of income from other sources and with no obligations” (Van Parijs and Vanderborght 2015). Hence, UBI is an unconditional and universal form of income, setting it apart from current redistributive policies in place, which rely on eligibility requirements, such as demonstrating a certain income level, and are conditioned to certain behaviors (typically, job searching). UBI can be seen as a social innovation (Koistinen and Perkiö 2014) that is both revolutionary and simple. This duality elicits both attraction and aversion from the policymakers and the general public. This is acknowledged as one of the reasons why UBI has struggled to find its way into political agendas since its systematization as a public policy in the XIXth century (Roosma and van Oorschot 2020; Van Parijs 2004). In fact, except for several limited-scope experiments, UBI has not yet been implemented in any country in the world, at least at a system-wide scale (Widerquist 2018).

The idea of UBI has notwithstanding received increased attention from scholars and practitioners worldwide, particularly after the COVID crisis (Banerjee et al. 2020; Ståhl and MacEachen 2021; Weisstanner 2022), as it is being advocated as a potential remedy for a wide range of pressing societal issues. These include but are not limited to unemployment, environmental crises, gender inequality, political disaffection, and the challenges arising from digitalization and automation (Carrero-Domínguez and Navas-Parejo 2019; Gómez-Frías et al. 2021; Hall et al. 2019; Weisstanner 2022). Simultaneously, while several researches have been made demonstrating its financial feasibility (Martinelli 2017; Díaz-Oyarzábal et al. 2019; Hoynes and Rothstein 2019), scholars and policymakers have consistently raised significant reservations regarding the feasibility of universal basic income (UBI), primarily stemming from its substantial implementation costs (De Wispelaere and Stirton 2012). Additionally, concerns have been voiced about its ethical suitability-is it appropriate that people without any particular condition live upon the work of others (Van Parijs 2004)?- and the uncertain consequences it might have on both individuals and the overall system, such as its potential for generating work disincentives (de Paz-Báñez et al. 2020), to alter the equilibrium of the labor market (Conesa et al. 2023) or to generate inflation (Miller 2021). Within the context of Spain, Casado and Sebastián (2019) and Díaz-Oyarzábal et al. (2019) offer a compelling illustration of divergent expert perspectives on the viability and desirability of implementing UBI in the country.

Over the last years, the literature on UBI has expanded from the theoretical and ideological arena to more empirically oriented debates. Experiments, such as the ones conducted in Finland (Andrade et al. 2022), Kenya (Widerquist 2018), Canada (Hamilton and Mulvale 2019), USA (Berenguer 2019) or Spain (García 2022) have enabled scholars to examine the economic, political and individual effects of UBI in practice. This is good news for UBI advocators, as, according to innovation theorists, one of the determinants for the diffusion of a social innovation such a UBI is its trialability, i.e. the extent up to which the idea can be tested before making a final commitment (Oldenburg and Glanz 2008). Nonetheless, the level of compatibility between a UBI and the values, beliefs, and needs of the public is recognized as another significant determinant for the diffusion of innovation, while our understanding of the general public’s perceptions and attitudes towards this pioneering policy alternative remains limited (Parolin and Siöland 2020; Zimmermann et al. 2020).

Understanding how the public perceives UBI and what arguments are important in shaping a favorable or negative opinion on the implementation of this innovative public policy is then of great importance for the further promotion of UBI into a political or economic agenda in any given context. In investigating this topic, it is useful to take into account that public perception of UBI is not necessarily connected to the expert debate, as voters tend to make decisions based on heuristics or mental shortcuts (Lau and Redlawsk 2001). While the question of which groups might support a basic income – and for what reasons – is not new, public opinion on UBI remains relatively underexplored. The existing literature on this topic is still in its early stages, having only recently begun to expand. In particular, the perspective of the middle class – often the social majority in many European countries – has received limited attention (Yeung 2022). Moreover, there is a notable lack of comprehensive analyses examining the actual arguments and positions both for and against UBI, as well as how these views compare to alternative policy options.

By drawing on innovation theories and adopting a mixed methods approach, this exploratory study addresses the following question: What arguments can be related to a positive and negative opinion towards UBI among Spanish middle class?

Both theoretical and practical implications can be derived from this study. To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first one that has addressed the analysis of critical arguments linked to public opinion about UBI in a given context using a mixed methods approach. This research contributes to the emerging literature on public opinion on a universal basic income (UBI) as well as to the field of innovation of public policies. It effectively identifies key arguments and criteria for segmenting the population, which could be employed in a more extensive quantitative survey on the subject. Additionally, it provides valuable perspectives that policymakers in Spain could incorporate while developing a communication strategy with the goal of garnering broad-based endorsement for UBI.

The article is structured as follows. Section 2 provides a synthesis of the theoretical framework in which this work is based. Section 3 describes the interview methodology and statistical analysis carried out. Section 4 describes the families of arguments identified in the interviews both for and against basic income.

Section 5 applies the predictive model, comparing these arguments as variables to obtain the feasibility, desirability and acceptance of the public policy. In Section 6, these results are interpreted, obtaining some very clear lines on arguments that are necessary and/or sufficient to deduce the position on basic income. Section 7 finally presents the conclusions illustrating how the above could be applied to the political communication necessary to facilitate the implementation of basic income.

2 Theoretical Framework

2.1 Innovation Theories and UBI

Innovation theories seek to explain the mechanisms by which ideas, concepts, technical information, and practices disseminate within societies and are embraced by individuals, organizations, and political communities. This pursuit involves investigating the reasons behind these processes, as well as the pace at which they occur (Berry and Berry 2018; Rogers 1983; Wejnert 2002).

Innovation theories have been applied to different fields, such as technology, political sciences, geography, economy or sociology. Of particular interest for this research is the fact that they have also been used to analyze the spread of policy innovations, such as new educational models (Ramirez and Boli 1987), social security systems (Weyland 2005) or welfare reforms (Thomas and Lauderdale 1988). The innovation theory lens has also been used to analyze the reasons for the (non) adoption of a UBI in Finland (Koistinen and Perkiö 2014). It has been noted that innovation in policy institutions and particularly in welfare policies is often intricate and slow (Pierson 2000), due to complex path dependencies and numerous intertwined factors. Large scale welfare reforms have occurred only in very specific periods of time, often after large crisis which open a “window of opportunity” (Sweeney et al. 2000). Other than that, public policy making is often reactive and incremental (Greener 2005; Pierson 2000).

As an example, in Spain, the COVID crisis opened a window for a reform of redistributive policies in 2020. For a few months, the possibility of establishing a UBI was raised. However, ultimately an incremental solution was considered, introducing a “Minimum Living Income” (a conditional and not universal income) at the national level, which supplemented the existing minimum income system already in place in all Spanish regions (Government of Spain 2020). While the new system meant an increase on the global national budget devoted to redistribution policies, its implementation has suffered from typical bureaucratic difficulties associated with non-universal and conditional systems (Gimeno-Ullastres 2019). As repeatedly denounced by entities such as the State Association of Directors and Managers of Social Services of Spain (2023), due to its bureaucratic complexity, after three years of its introduction, only 20.8 % of the population living under the poverty line benefit from the minimum living income in Spain.

One of the main topics discussed in the context of innovation theories is the dynamics of innovation diffusion. These dynamics is based upon the fact that there are different types of adopters depending on how prone they are in adopting these innovations. Adopters have been classified according to the following groups: early adopters, early majority, late majority, and laggards. For the innovation to achieve self-sustainability, it requires broad adoption among individuals or groups. Within the adoption rate, there exists a threshold known as the critical mass, where the number of individual adopters guarantees the ongoing self-sustained adoption of the innovation (Rogers 2014; Wejnert 2002).

A second recurrent topic in innovation theory is the discussion around the determinants of diffusion’s extent and speed (Oldenburg and Glanz 2008). As an example, Oldenburg and Glanz (2008) establish the following factors conditioning a social innovation diffusion: relative advantage over alternative options, the fact that the idea can be tried before making a final commitment (trialability), the amount of risk associated with the innovation, and the compatibility or fit of the innovation into the audience’s lifestyle, cultural/ethnic beliefs and practices or self-image. In a similar vein, Koistinen and Perkiö (2014) define a number of dimensions associated to successes and failures of UBI proposals in Finland: the specific characteristics of the proposal, the channels and actors intervening in its communication, the macro-economic and political context, the perception of different actors regarding the proposal and the achieved outcomes. Along these and other innovation models, it is obvious that the perception of the public about the UBI proposal is one of the primary influencing factors.

Therefore, from the perspective of innovation theory, focusing on comprehending public opinion regarding UBI is highly relevance. In the Spanish context, where the middle-income class forms a significant social majority, investigating the perceptions of this group is relevant, as reaching the critical mass necessary to guarantee enough UBI support would heavily rely on effectively engaging with the interests and needs of this particular demographic. Moreover, according to previous research, middle-income class tends to be particularly reluctant to the implementation of a UBI as they perceive themselves as net payers and not beneficiaries of the proposal (Roosma and van Oorschot 2020; Zimmermann et al. 2020).

Although a recent body of literature exists devoted to investigating public opinion of UBI, previous studies have essentially concentrated in revealing various explanatory factors (geographic, demographic and psychographic). In contrast, research on the actual arguments and positions for and against UBI as well as how it is compared with other policy options is scarce. The following section provides an overview on prior research on this topic.

2.2 Overview of Prior Research on Public Opinion of UBI

The strand of literature that investigates public opinion of UBI is recent-most studies are not more than five years old- and still emergent. Regarding its geographical coverage, there are various studies that focus on the European region as a whole (Baranowski and Jabkowski 2021) and specific countries within Europe, such as Finland (Linnanvirta et al. 2019), Belgium (Laenen et al. 2023), Croatia (Relja et al. 2015), the Netherlands (Gielens et al. 2023) and Spain (Rincon 2023; Gómez-Frías et al. 2021). There are also studies conducted in other regions of the world that concentrate on specific countries like the US (Hamilton et al. 2023; Yeung 2022), Canada (Calnitsky 2018), Australia (Patulny and Spies-Butcher 2023), Japan (Yang et al. 2020) and South Africa (Fouksman 2020) as well as comparative studies between countries within Europe and across different regions (Baranowski and Jabkowski 2021; Chrisp et al. 2020; Nettle et al. 2021; Stadelmann-Steffen and Dermont 2020; Zimmermann et al. 2020). It is evidence that there is a lack of such studies in large areas of Africa and Asia, as well as in Latin America.

In terms of methodology, most studies use official cross-national or national surveys, such as the European Social Survey (ESS), as an empirical basis for their analysis (see for example, Baranowski and Jabkowski 2021; Choi 2021; Lee 2021; Nettle et al. 2021). While this kind of quantitative studies are useful to detect demographic and social factors at a macro level that are related to positive or negative perceptions about UBI, they rely on questions that are often too generic. In consequence, they fail to capture important context-specific factors and psychological mechanisms that would be important to grasp people’s understanding of the UBI and the reasons why they reject or support it (Chrisp et al. 2020). Other works also adopt quantitative approaches but rely on more specific survey or experimental designs (Stadelmann-Steffen and Dermont 2020; Yang et al. 2020; Yeung 2022). These enable to test public’s opinion in view of more specific context-dependent implementation scenarios. Finally, a number of recent works adopt a qualitative approach to delve into specific dimensions, such as the social legitimacy of UBI from a social justice perspective (Zimmermann et al. 2020), the attitudes of young citizens to the introduction of UBI in a specific scenario linked to automation (Herke and Vicsek 2022) or the position of a particular sector in a given country (Gómez-Frías et al. 2021).

Regarding the findings of these studies, literature on the subject essentially concentrates in revealing various explanatory factors (geographic, demographic and psychographic) that could be linked to certain opinions or perceptions for and against UBI. In this regard, at least in the European context, geographic factors have been found to have an impact on public support for UBI. Indeed, it has been found that, globally, support for basic income seems to be significantly higher in Central and Eastern European countries (Baranowski and Jabkowski 2021), although results at the country level contradict this outcome and show high levels of support in Nordic countries such as Finland when compared to a Central European country such as Switzerland (Stadelmann-Steffen and Dermont 2020). The literature is more consistent regarding the influence of macroeconomic factors. Indeed, UBI tends to be more supported in countries with lower levels of GDP and lower social spending and employability rates (Laenen et al. 2023; Parolin and Siöland 2020). Moreover, the perspective adopted by the public towards a UBI seems to be strongly shaped by the welfare institutions of the countries in which they live (Shin et al. 2021; Zimmermann et al. 2020).

Regarding demographics, many studies reveal a link between the class position of individuals and UBI support, as people who are in a more vulnerable socio-economic position – including often younger, low-income individuals, unemployed or precariously employed, suburban renters, etc.- support UBI more (Bollain et al. 2025; Roosma and van Oorschot 2020; Shin et al. 2021; Zimmermann et al. 2020). However, findings regarding the link between the level of education and support are not conclusive. While studies in regional contexts such as Australia show higher support towards UBI from individuals that are higher educated (Patulny and Spies-Butcher 2023), other studies in different contexts (The Netherlands) show that the higher and the lower educated are equally ambivalent towards the policy (Gielens et al. 2023). Other demographic explanatory factors that seem to influence individuals’ perceptions toward UBI identified in literature are family structure and interest in participating in non-market activities (Yang et al. 2020).

Psychographic factors, such as values and lifestyles, seem to have great explanatory power to understand differences in UBI support, particularly in countries with higher levels of spending (Parolin and Siöland 2020). Support seems to be higher in individuals who have more post-materialist concerns, including Green-left voters and egalitarianists, and those favoring redistributive values and universalism (Choi 2021; Patulny and Spies-Butcher 2023; Roosma and van Oorschot 2020) and has been found to be lower and more rigid among conservatives (Yeung 2022). Welfare state chauvinism is also more likely to be associated with negative attitudes towards a UBI in higher income countries (Bay and Pedersen 2006; Diermeier et al. 2021; Laenen et al. 2023, 2023; Parolin and Siöland 2020). Other values, such as power and achievement are positively and significantly associated with support for UBI, while other values such benevolence, has a negative relationship with that (Choi 2021).

The existing body of literature that comprehensively analyzes the actual arguments and positions in favor of or against UBI, and how it is compared to alternative policy options, is scarce. There is a dearth of research in this area, with only a few notable studies, such as the recent work conducted by Rincon (2023) within the Spanish context, providing valuable insights. Through a conjoint analysis for understanding the way the public compares UBI to other policy options, this study reveals that, for the Spanish public, one of the most controversial UBI features is its universality, i.e. the fact that it is given to everyone and not only to “the poor”, while its unconditionality (the lack of conditions to recipients) is less unpopular. This has been found to be the case also in other contexts (Lee 2021; Roosma and van Oorschot 2020). Beliefs about the meaning of work and the need for work-based society are also very prominent in shaping perceptions about UBI in different contexts (Herke and Vicsek 2022).

In any case, when examining various aspects of public acceptance towards UBI, there seems to be a consensus in considering two dimensions: desirability-with respect to ethical or moral normative beliefs – and feasibility – understood as the viability of financing and implementing public policy in a given context-see for example, Van Parijs and Vanderborght (2017) or Busso et al. (2019).

3 Methodology

3.1 Sample Selection

An exploratory study was carried out based on semi-structured interviews with a convenience sample composed of individuals of different ages, professional profiles and genders belonging to the Spanish middle class.

From the perspective of innovation theory, placing emphasis on comprehending public opinion regarding UBI is of utmost importance. In Spain, where the middle-income class constitutes a substantial portion of society, it is particularly important to explore the views of this group. Indeed, according to the OECD the lower-income class is defined as those whose income falls below 75 % of the national median income; the middle-income class is between 75 % and 200 % of the median, while the upper-income class consists of those whose income exceeds 200 % of the median (OECD 2019). According to 2022 data by the Spanish National Statistical Institute (INE 2022), around 65 % of the Spanish population belongs to the middle-class.

Gaining widespread support for UBI would then largely depend on addressing the interests and needs of this demographic, which could be pivotal in achieving the necessary critical mass for its successful implementation. Similarly, a sample in which the dominant expectation is that they will be net payers after the implementation of a basic income favors understanding resistance among those who may be adversely affected by the measure.

Participants were recruited as volunteers from the personal networks of the researchers and over 60 students in a third-year undergraduate class, using a snowballing technique. An open call was also launched through social networks to recruit further candidates.

The applied methodology can be considered a mixed methods approach in the sense that combines qualitative and quantitative data collection and analysis in one study.

3.2 Qualitative Phase: Interviews

Interviews were conducted between the months of October 2022 and May 2023. Seven interviews were considered invalid or not fulfilling the segmentation criteria. In total, 45 valid interviews were conducted.

18 of the interviewees were women and 27 were men. The age profile of the persons interviewed ranged from 20 to 73 years old. 42 % of the sample was younger than 20 years old, 36 % of the sample was between 25 and 55 years old, and 22 % of the sample was more than 55 years old. Most of the interviewees were from the Community of Madrid (25 people). The rest belonged to other Spanish regions (Andalusia, Cantabria, Asturias, Galicia, Castilla-León, the Basque Country and the Canary Islands).

None of the interviewees had a marked political ideology (affiliation or loyalty to a specific party), but most declared themselves to be affiliated with generally moderate political currents (center, center-right, center-left or center-liberal). In general, with three exceptions, the people included in the sample did not have first-hand knowledge of the situation of people receiving social benefits. All interviewees were either employed or studying at the time of the interview. All of the jobs they were doing corresponded to the “white-collar” category, in the sense used by Weaver (1975), i.e. professional, clerical, managerial or administrative workers.

The interviews were designed to evaluate to what extent a UBI was acceptable for the individuals and preferable to other welfare options as well as to engage in a thorough discussion on the arguments for and against UBI. It is worth noticing that this kind of discussion is not possible when adopting more massive quantitative approaches. The design was validated on the basis of a focus group with professionals from the construction sector; the results of this focus group are explained in Gómez-Frías et al. (2021). Specifically, the interviews were conducted according to the following structure:

First, respondents were asked to answer the following question: “What do you think the Welfare State should offer to all citizens? Minimum living income; Universal basic income; Either; Neither; I don’t understand the difference; Other. This initial question was designed to test general knowledge and awareness about UBI and other welfare options implemented in Spain.

Next, respondents were asked to argue about the desirability and feasibility of Basic Income.

Subsequently, to enrich and help focus the terms of the discussion, participants in the study were shown a 5-min informative video produced by Spanish public television (RTVE 2020). The full content of this video can be watched online. This video showed the summary of arguments for and against basic income wielded by several academic experts in the field throughout a conference on Basic Income organized at the Polytechnic University of Madrid in October 2019. The event was organized around two round tables and brought together 10 experts from different disciplines (economics, law, business administration, sociology and philosophy). More specifically, the video covered the following topics: The potential impact of automation on the job market; the concerning situation of growing poverty and inequality worldwide; the difference between minimum income and basic income policies; inefficiencies and bureaucratic problems associated with minimum income policies; the poverty trap; stigma and invasion of family privacy associated with minimum income policies; potential decrease in labor supply and active population that could be generated by a basic income; potential of UBI to improve recognition of sectors with high social value but low market value.

After the video, the interviewees were asked to react to the arguments presented and to continue arguing about the acceptance of UBI.

Finally, as a general conclusion of the discussion, interviewees were asked to provide a binary answer (“Yes”, “No”) regarding the three response variables measured in the quantitative phase (see below): desirability, feasibility and acceptance.

All interviews were recorded and transcribed. Subsequently, the collected material was analyzed using content analysis techniques (Miles and Huberman 1994; Saldaña 2021). The codes were defined inductively and were iteratively refined throughout the analysis. All interviews were coded by two researchers independently and discrepancies that arose were resolved in successive working meetings. The coding and analysis applied followed a force-field logic (Lewin 1951). Force-field analysis considers human behavior as dynamic, resulting from the balance of forces working in opposite directions. According to this conception, change in behavior would occur when the forces in favor of a given change outweigh the forces against it (see Figure 1).

“Force-field” logic used in the analysis on acceptance of UBI (own elaboration).

3.3 Quantitative Phase: Logistic Regression

The statistical analysis of the results was performed by applying logistic regression or logit regression. Logistic regression is a type of regression analysis used to predict the outcome of a categorical variable (a variable that can adopt a limited number of categories) as a function of the independent or predictor variables (Harrell 2001; Hosmer et al. 2013). The term logit refers to the natural logarithm of the odds ratio (the probability of success of the studied phenomenon divided by the probability of failure of that same phenomenon). The logit technique fits a regression model where the response variable would be logit of the probability of the studied variable.

Specifically, and following Van Parijs and Vanderborght (2017) and Busso et al. (2019), three response variables were considered: Desirability, Feasibility, and Acceptance (a combination of the first two). The operationalization of these variables was as follows:

Desirability: whether UBI it is considered desirable from an ethical or normative perspective.

Feasibility: whether UBI is seen as practicable from a pragmatic standpoint (e.g. budgetary, organizational).

Acceptance: the overall position in favor of or against UBI.

Response variables were treated as binary categorical variables, with 0 representing “No” responses to the final question asked in the interviews (“In your opinion, is a UBI desirable/feasible/acceptable?”) and one representing “Yes” responses to the same question.

Independent variables comprised various arguments for and against basic income, which were coded as binary categorical variables. A “1” indicates the presence of the argument in the discussion, while a “0” signifies its absence. Arguments in favor of basic income include those suggesting positive outcomes at either a systemic or individual level resulting from UBI implementation. Conversely, arguments against basic income highlight potential negative outcomes or logical flaws at either the individual or systemic level.

4 Arguments Against and in Favor of Basic Income

4.1 General Results on Awareness and Acceptance of UBI

A general descriptive analysis of the results shows that the majority of those interviewed adopted a critical attitude towards basic income. Thus, 47 % of the sample considered this public policy desirable and only 24 % considered basic income to be feasible. 45 % of the sample considered basic income neither feasible nor desirable. Finally, only 16 % considered basic income acceptable (simultaneously desirable and feasible).

It is worth noticing that 20 % of people in the sample declared that they did not know what a UBI was. Among those that declared to understand the concept, there were many that, throughout the discussion, showed a confusion between UBI and other forms of conditional welfare policies (such as the Minimum Income). In general, there was a widespread lack of knowledge and awareness regarding the type and outcomes of welfare policies already in place in Spain.

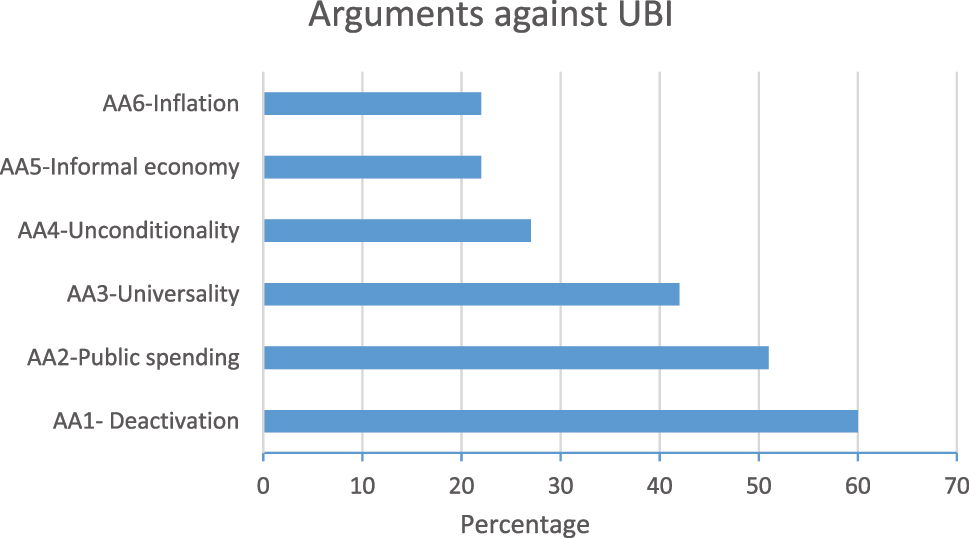

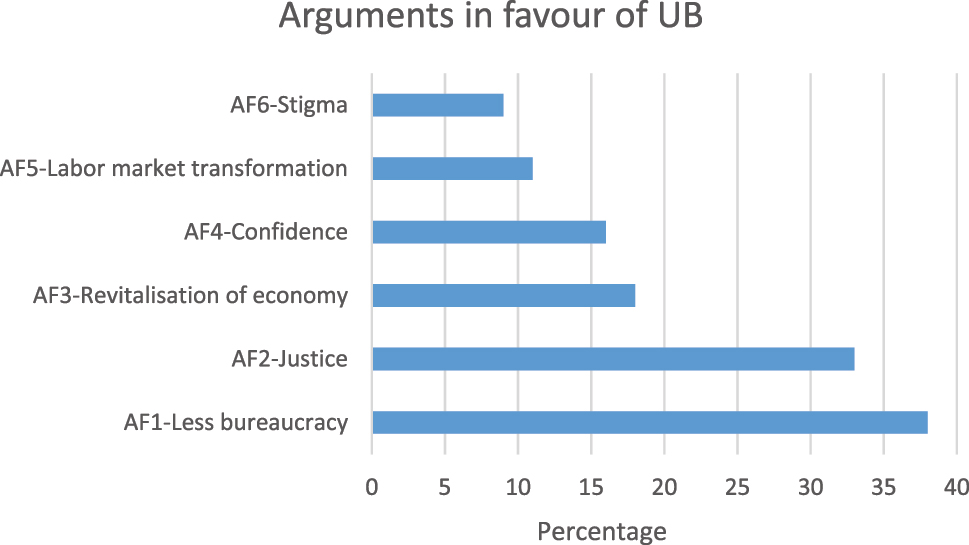

The qualitative analysis made it possible to clearly identify six arguments against and six arguments in favor of UBI in the discourse. These arguments are presented in the following sections and summarized in Figures 2 and 3.

Arguments against UBI present in the sample. Source: Own elaboration.

Arguments in favor of UBI present in the sample. Source: Own elaboration.

4.2 Arguments Against UBI

4.2.1 AA1- Deactivation of the Economy

A majority argument (60 % of those interviewed) was that basic income could be a disincentive to economic activity. As one of the persons interviewed declared:

UBI would act as a disincentive for formal employment. The appropriate welfare measure remains to provide an income guarantee while allowing it to be compatible with other social benefits. On the other hand, ’living off subsidies’ is increasingly being passed down as an intergenerational way of life.

In particular, many people felt that it could result in less interest in filling certain jobs (the less qualified ones). This could have as a side effect an improvement (or at least a change) in the quality of employment supply.

Several people from economically depressed regions, where low-skilled citizens predominate, were particularly sensitive to this argument and insisted that basic income would create many problems in these regions. Some interviewees went so far as to state that basic income would “eliminate the competitiveness of the system” or “anesthetize citizens”. As it was explained by one of the persons interviewed:

In my town, there are few qualified professionals, and most jobs are basic. I wouldn’t be able to hire the assistants I have in my clinic (for those people, it would mean quitting their jobs). This could jeopardize essential employment. In the environment I work in, it would be discouraging.

This outcome aligns with prior research on public attitudes toward UBI, as it reinforces the significance of beliefs regarding the necessity of a work-centered society in influencing perceptions of UBI (Laenen et al. 2023). Interestingly, there is not empirical evidence of a significant reduction in labor supply linked to UBI (de Paz-Báñez et al. 2020; Gibson et al. 2018). UBI has been rather found to stimulate activity although a decrease in workers from certain categories has been also noted, i.e. children, the elderly, the sick, those with disabilities, women with young children to look after, or young people who continued studying (de Paz-Báñez et al. 2020).

On the other hand, this result introduces a contrasting perspective or adds nuance to the notion that UBI tends to garner greater support in countries or regions with lower GDP levels (Laenen et al. 2023; Parolin and Siöland 2020). In any case, it appears that the regional context plays a crucial role as a segmentation factor in this particular scenario.

4.2.2 AA2- Increase in Public Spending

Another argument that was very present in the interviews (51 % of those interviewed) was that the implementation of basic income would lead to an increase in public spending and the general level of taxes. Some interviewees were of the opinion that the increase in spending would be “completely unsustainable” or would lead us “to ruin”. Other interviewees, however, gave a more balanced assessment of the possible increase, arguing that “we can afford it” or that “instead of spending the money on something else it could be spent on this”. All interviewees identified themselves as belonging to the segment of “net payers” of basic income.

Several interviewees emphasized the need to adopt an overall view and not forget the circular nature of income and that money “has to come from somewhere”. They emphasized the need to increase business productivity in order to be able to adopt public policies such as basic income.

In general, it was evident that there is a wide lack of knowledge among the population regarding the magnitudes and types of coverage of the current welfare state, with largely unfounded apprehensions about the budgetary cost of UBI, bearing in mind that, at least in certain implementations, it would replace conditional benefits up to the same level as that adopted for basic income. In any case, many people within this segment admitted to having difficulty in assessing the potential increase in spending, which, as also found in previous studies, reinforces the importance in this discussion of providing accurate information on the type of implementation envisaged (Díaz-Oyarzábal et al. 2019). Furthermore, regarding this argument, to move forward in the debate, it seems clear that it is necessary to articulate a complete vision of the social and economic model to be built and not only of the particular redistribution strategy.

4.2.3 AA3- Difficulties to Accept Universality

A significant proportion of the people interviewed expressed difficulties in accepting an income of a universal nature (42 % of the sample). For these people, it is counter-intuitive or ineffective to give money “to the rich”. The state should then help “only those who need it”. Sometimes it seems that this segment does not understand that the benefit would be returned through taxes; at other times it does seem to understand the mechanism, but it is described as “absurd”. The possible administrative difficulties generated by the implementation of a conditional income system, they add, should be solved (by adding civil servants, simplifying the criteria or implementing electronic administration). As it was expressed by one of the persons interviewed:

Giving money to people who don’t need it makes no sense. I understand that the management (of a conditional income system) is not easy, but I guess there could be mechanisms to make a good selection. Just improve the algorithm or add more civil servants to the process!

While experts are unanimous in stressing the importance of the administrative difficulties of conditional income systems (Gimeno-Ullastres 2019, Herd and Moynihan 2019), the discussion surrounding universality appears to be primarily influenced by diverse normative perspectives.

This result is consistent with the outcomes of previous studies conducted in Spain, which indicated a notably low level of popularity for universality (Rincon 2023).

Also linked to the idea of universality, some people expressed their opinion about the fact that UBI should be given only to certain demographic groups, particularly young people, as it would be a mean to “help them in the beginning of their lives”. However, this was a matter of dissention, as other people in the sample were afraid that a UBI could act as a “perverting” factor and “result in young people who neither study nor work”. In one of the interviewed person’s own words:

The group that scares me the most is the youth. How do you give money without asking for anything in return to one of those 16-year-olds who are disoriented and not looking for anything in life? The most likely outcome is that they would become parasites of their families and the system forever.

This aspect of the discussion is particularly compelling, as Spain has the highest child poverty rate in the EU (UNICEF 2024), and, linked to this problem, it has been suggested that there could be a potential consensus on providing a basic income to minors-see for example, the discussion by Salguero (2024). However, this assertion overlooks the negative sentiments held by a segment of society about this i.e. which could potentially obstruct this initiative.

4.2.4 AA4-Difficulties to Accept Unconditionality

Another aspect that was considered counterintuitive, although by a smaller proportion of respondents (27 % of people) was the unconditional nature of the basic income. That is, the fact that the benefit would be provided without any quid pro quo. This segment expressed their conviction that the money distributed by the state should be spent on morally adequate goods, such as “food and other basic necessities”, and in no case on luxury or leisure goods. One person pointed out the need to assume “certain obligations” when enjoying “certain rights,” such as the responsibility to seek employment. Another respondent stated that offering such a benefit should be accompanied by a social intervention to bring about a change in behavior and in particular should be accompanied by training actions to reduce the digital divide. Some of those interviewed went so far as to point out that UBI would mean a “degradation of values” and even an increase in “vices and addictions”. In one of the interviewee’s own words:

As long as there is no control over behaviour, money will be lost along the way. What happens to those who don’t know how to manage it? People spend more than they can afford, and with more money, there’s a risk of falling into addictions. This might lead to increased spending on security and healthcare to treat these addicted individuals.

This kind of argument has been widely found in previous studies on deservingness of UBI and welfare policies in general (Laenen et al. 2023; Rincon 2023; Roosma and van Oorschot 2020).

Similar to the discourse on the universality of UBI, discussions surrounding the unconditional nature of UBI appear to be predominantly influenced by diverse normative perspectives rather than technical or expert-driven arguments.

4.2.5 AA5-Corruption and Informal Economy

22 % of the people interviewed believed basic income would encourage the informal economy and “undeclared” work, particularly in a context such as the Spanish one, where there are practices of “fraud” and “corruption” that hinder the implementation of this type of measures. The implementation of a basic income would require an “impeccable” economic context, as the “Nordic countries”, for example, are thought to have. As one of the interviewed persons declared:

We are not Finland or Sweden. We are not there, either economically or culturally. There is an informal economy, and receiving ’free money’ doesn’t help people in general.

Again, as found in previous studies, this result reinforces the importance of the regional or geographical and macroeconomic context as a segmentation factor (Baranowski and Jabkowski 2021; Laenen et al. 2023; Parolin and Siöland 2020; Stadelmann-Steffen and Dermont 2020).

Interestingly, respondents were not aware of the “poverty trap” mechanisms that are typically associated to conditional welfare schemes (Barrett et al. 2016). One consequence of this issue is that individuals enrolled in such programs hesitate to accept potentially unstable job offers out of fear to lose their income rights. In consequence, they decide not to work or to adopt an informal activity (Barrett et al. 2016; Bueskens 2017). In this regard, although the effect of UBI over informality is object of controversy in expert debate (Elgin et al. 2022; Rubião 2021), certain proponents of UBI argue in expert discussions that an unconditional welfare scheme would likely alleviate the informal economy instead of promoting it (Gimeno-Ullastres 2019).

4.2.6 AA6-Inflation

Finally, 22 % of the people interviewed were convinced that the implementation of a UBI in Spain would generate a generalized price increase or an increase in certain products (leisure or luxury products, which would be consumed more frequently).

While the possibility of local inflation effects is acknowledged in expert discussions (Miller 2021) a generalized inflationary phenomenon would only be possible if a UBI was financed through “helicopter money”, i.e. by increasing money supply.

4.3 Arguments in Favor of UBI

4.3.1 AF1-Less Bureaucracy

There are management problems and administrative difficulties associated with minimum income systems. In particular, the operationalization and control of the conditions necessary to be able to receive these incomes are complex, which generates high administrative costs and means that in practice many of the people who should receive the subsidy do not actually receive it. 38 % of those interviewed were sensitive to this argument, frequently expressed by advocators of UBI in expert debates (Barragué et al. 2019; Gimeno-Ullastres 2019). The less bureaucracy and simplicity associated with a UBI system was perceived as a favorable element for acceptance for 38 % of the sample.

4.3.2 AF2-Justice

For 33 % of those interviewed, implementing a basic income would reduce inequality and allow us to live in a fairer society. These people were aware that effectively tackling poverty would bring collective benefits, such as greater social stability or reduced risks for a broad spectrum of the population, regardless of who the recipients or net payers were.

This result resonates with previous studies which have found that psychographic factors, such as values and beliefs are of great relevance in explaining UBI support. In particular, as found in this case, people that are egalitarianists are more favorable towards UBI (Choi 2021; Patulny and Spies-Butcher 2023; Roosma and van Oorschot 2020).

4.3.3 AF3- Revitalization of the Economy

For 18 % of the sample, implementing a UBI would activate consumption and contribute to boosting the economy. Several people expressed that receiving a basic income would be “like returning taxes to all citizens”.

It is interesting to note that while previous studies on public opinion towards UBI have linked support for it with green-left voters (Choi 2021), this argument aligns more closely with a liberal ideology. This observation aligns with the notion of ideological transversality of UBI, as frequently stated by academics (Barragué et al. 2019).

4.3.4 AF4- Improving Confidence

Basic income could make people feel calmer and more confident to move forward, to become emancipated and even to undertake or start a new professional path. This argument was put forward by 16 % of the sample. It is interesting to note that, in general, no significant differences were found in the frequency of occurrence of the different arguments for different age groups and genders, except for this argument, which was significantly more frequent for women. This result suggests that gender could be a relevant segmentation criterion for investigating public opinion towards UBI. Interestingly, while the gender perspective of UBI has been explored in scholarly papers and expert debates (Lombardozzi 2020; Schulz 2017), up to the current moment, this dimension has not been explored in the context of the studies specifically investigating public opinion towards UBI.

Indeed, the benefits that a UBI would have for the incumbent population in terms of mental health have been apparent in several UBI experiments (Wilson and McDaid 2021). As an example, during the recent UBI experiment in Finland, participants who received a UBI declared to be more satisfied with their lives and experienced less mental strain, depression, sadness and loneliness. Additionally, individuals who received basic income demonstrated a higher level of trust in both fellow citizens and social institutions. Moreover, they exhibited greater confidence in their own future and their ability to exert influence compared to the control group (Kangas et al. 2019).

4.3.5 AF5-Labor Market Transformation

Only 11 % of the sample mentioned the digital revolution and the transformation of the labor market. For these people, the basic income debate is relevant and interesting in a context where it will be necessary to find innovative solutions. This result has been found in previous studies on public opinion of a UBI, which stresses that the public’s attitudes towards the policy seem to be significantly influenced by how they perceive the future vision of a society transformed by UBI (Yang et al. 2020).

It is intriguing that while this dimension is very present in expert debates (Dermont and Weisstanner 2020; Hamilton and Mulvale 2019; Mulvale 2019; Yang et al. 2020), it did not hold significant prominence within the sample. This observation could be attributed to the public’s tendency to adopt a short-term perspective, as evidenced in previous studies (Gómez-Frías et al. 2021).

4.3.6 AF6- Reduction of Stigma

Finally, only 9 % of the people interviewed were sensitive to the fact that basic income would avoid the stigmatization that could result from being “singled out” as a beneficiary of a minimum income.

As mentioned earlier, the positive impact of UBI on mental health, which is partly attributed to the reduction of stigma, has been emphasized in UBI experiments (Wilson and McDaid 2021). The limited significance of this argument within the sample could be interpreted as a challenge for the target group (net payers) to empathize with the emotions and experiences of the beneficiaries.

5 Predictive Model for Feasibility, Desirability and Acceptance

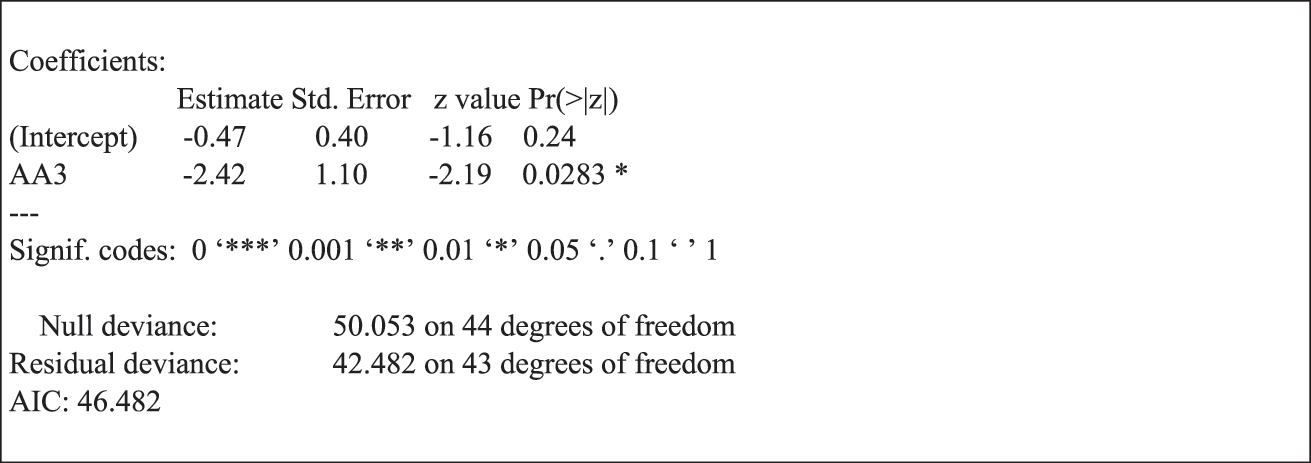

5.1 Feasibility

Logit models were tested with all dependent variables (arguments for and against defined as categorical variables with two levels-0 if argument does not appear; one if argument appears) against feasibility as the response variable.

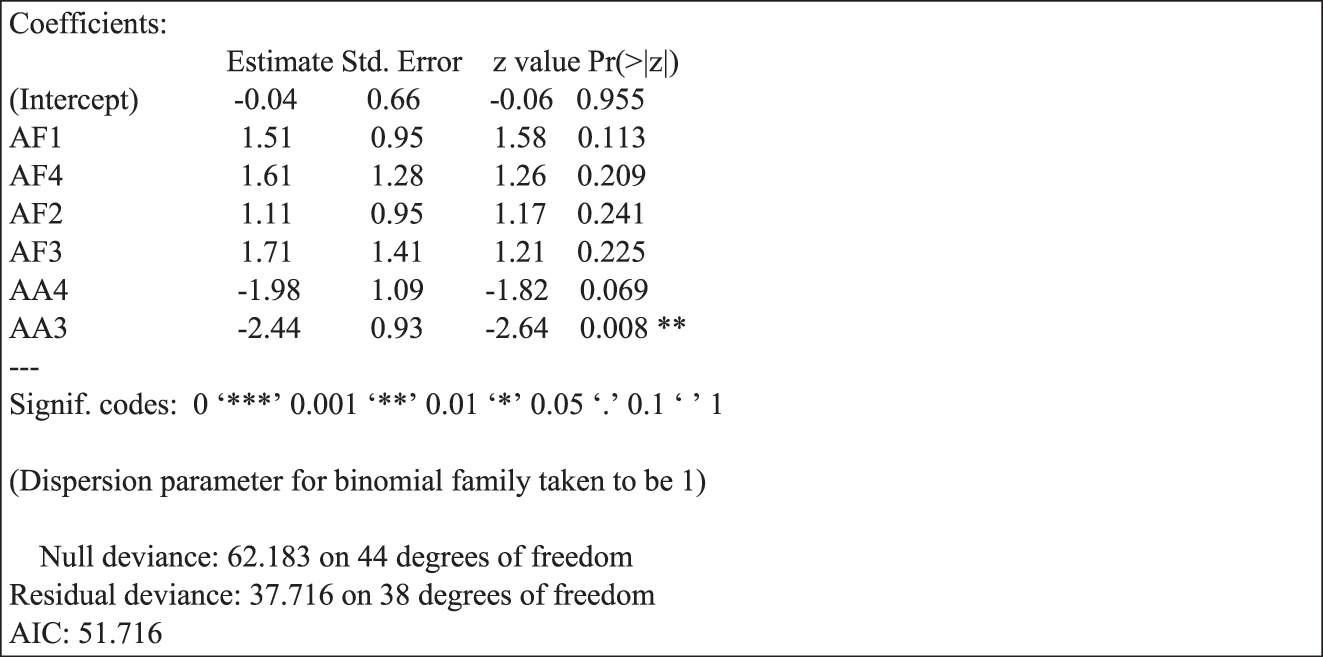

Only a negative association corresponding to argument AA3 (“Difficulties in accepting the universality of basic income”) was significant with 95 % confidence. That is, those people who do not understand the interest of “giving money to the rich” and then giving it back through taxes are those who are more likely to consider basic income unfeasible. These people are precisely those who minimize the importance of the problems and administrative inefficiencies generated by minimum income systems. Figure 4 shows the coefficients of the estimated model, as well as the values of the residual variance and the Akaike information criterion.

Predictive model for feasibility based on logit regression. Source: Own elaboration.

Regarding the diagnosis of the model for predictive purposes, the Likelihood ratio test provides a p-value of 0.0155 (significant value for a confidence level greater than 95 %). However, we obtain a classification error of 27 % when performing the classification table. This is an appreciable error and indicates that there are additional factors that should be included in the model that have not been covered by the current study.

5.2 Desirability

Again, logit models were tested with all dependent variables against desirability as the response variable. Four arguments in favor (AF1, AF2, AF3 and AF4) and two against (AA3 and AA4) were significant. Table 1 shows the coefficients of each of the models, as well as their level of significance.

Arguments linked to UBI desirability (logit model). Source: Own elaboration.

| Argument | Coeficient | P-value | Significance level |

|---|---|---|---|

| AF1-Less bureucracy | 1.19 | 0.063 | 90 % |

| AF2-Justice | 1.23 | 0.063 | 90 % |

| AF3-Revitalisation of economy | 1.48 | 0.093 | 90 % |

| AF4-Confidence | 2.22 | 0.050 | 95 % |

| AA3-Universality | −2.49 | 0.001 | 99 % |

| AA4-Unconditionality | −1.28 | 0.089 | 90 % |

Again, as in the case of feasibility, we see that the most important and clearest association (highest degree of significance) is with argument AA3 (“Difficulties in accepting the universality of basic income”). This would be followed by the argument that affects the capacity of basic income to generate confidence to face the future (AF4); then, the argument that relates basic income with a revitalisation of the economy through an activation of consumption (AF3), followed by the difficulties to accept giving an income without conditions (AA4), the perception that basic income would improve social justice (AF2); finally, the opinion on the capacity of basic income to simplify bureaucracy (AF1).

Next, we constructed a predictive logit model with all significant variables. The Akaike information criterion is the lowest of all the models constructed in relation to desirability (greater than 60 in all cases), which confirms its greater suitability as a predictive model (Figure 5).

Predictive model for desirability based on logit regression. Source: Own elaboration.

The classification error of the predictive model is 22 % and the Likelihood ratio test gives a p-value of 0.00042 and is therefore highly significant.

5.3 Acceptance

Finally, logit models were fitted for acceptance. Three arguments in favor (AF4, AF2 and AF3) and one against (AA1) were significant. Gender was also significant with a negative coefficient, showing that women in the sample are more likely to accept basic income (Table 2).

Arguments linked to UBI acceptance (logit model). Source: Own elaboration.

| Argument | Coeficient | P-value | Significance level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | −1.57 | 0.082 | 90 % |

| AF4-Confidence | 1.85 | 0.046 | 95 % |

| AF2-Justice | 1.94 | 0.033 | 95 % |

| AF3-Revitalisation of economy | 1.60 | 0.076 | 90 % |

| AA1-Deactivation of economy | −1.57 | 0.083 | 90 % |

The most important association is established with argument AF2, which refers to the idea that basic income would contribute to a fairer society for all. This is followed by argument AF4, i.e. the argument that basic income would contribute to strengthening confidence in the future and the ability to take important steps in life. This is followed with a lower level of significance by the AF3 argument (the capacity of basic income to dynamize the economy through an increase in consumption) and AA1, the belief that basic income would discourage work.

The model has a good predictive capacity, with only a 7 % error in the classification matrix and an Akaike criterion value of 28.2. The likelihood ratio test is 0.0004 and is therefore highly significant.

6 Discussion of Results

Table 3 presents a summary of the arguments and factors that were significant for feasibility, desirability and, finally, acceptance of UBI among the population in the sample.

Summary of arguments linked to the perception of feasibility, desirability and acceptance. Source: Own elaboration.

| Arguments/factors | Feasibility | Desirability | Acceptance |

|---|---|---|---|

| AA1-Deactivation of economy | x | ||

| AA3-Unniversality | x | x | |

| AA4-Unconditionality | x | ||

| AF1-Less bureaucracy | x | ||

| AF2-Justice | x | x | |

| AF3-Revitalisation of economy | x | x | |

| AF4-Confidence | x | x | |

| Gender | x |

It can be observed that there are two arguments against basic income (AA3, AA4) that condition the perception of feasibility and/or desirability, but not acceptance. We could qualify them as sufficient, but not necessary arguments. In other words, they are arguments against basic income which, when they appear, are sufficient to increase the probability of not accepting basic income, but their absence does not necessarily have a significant impact on the segment of people who accept the policy. These arguments are related with the very nature of basic income: a universal income granted without conditions. People in whom these arguments are present simply consider that it is an absurd idea and that it would involve excessive expenditure. Why give money to those who do not need it? If this money is to be paid back through taxes, why do we give it to them in the first place?

On the other hand, being sensitive to the fact that basic income could mean greater administrative simplicity and lower bureaucratic costs (AF1) is a favorable element, but not enough to accept basic income.

The acceptance of basic income is very fundamentally conditioned by normative and non-practical arguments. In the first place, it rests very strongly on the value of social justice (AF2). People for whom achieving fairer and more egalitarian societies is important accept the idea of basic income to a greater extent. On the other hand, positively valuing the greater calm and confidence that a benefit of this type could generate is also a determining argument (AF4). This argument appears in people who, throughout their discourse, show greater empathy with respect to people who could be net recipients of basic income or who have even found themselves in a situation of vulnerability. It is worth noting that women, who are usually associated with higher levels of empathy and also risk aversion (Baez et al. 2017; Eckel and Grossman 2008), seem to present a higher level of acceptance of basic income in the sample.

There are also practical arguments related to the acceptance of basic income. Indeed, people who accept basic income seem to be optimistic about its systemic effects (AF3) and state that it could boost consumption or even translate into greater competitiveness of companies and higher rates of entrepreneurship. On the contrary, the fear of basic income being a disincentive to work and the economy (AA1) stands out as the main negative argument conditioning basic income. The fact is that the effects that a UBI could have in one sense or another seem to depend necessarily on the broader social and economic context in which this policy is inserted, as well as on other measures that could be taken to encourage entrepreneurial activity and education.

7 Concluding Remarks

7.1 Limitations

The results of the analysis identify eight variables relevant to the acceptance of basic income and/or its two components – feasibility and desirability. However, these findings should be understood as limited by the socio-geographical scope of the sample. To generalize the results more broadly, it would be necessary to extend the study to a larger, more diverse population. The current sample was intentionally focused on middle-income individuals, but, even taking this into consideration, there is a bias, as the upper-middle class is overrepresented, and participants are predominantly white-collar professionals with high levels of education. It would be beneficial to include lower-middle-class individuals and blue-collar workers to provide a more comprehensive perspective inside the targeted demographic group.

That said, while the data collected from the interviews has been subjected to quantitative analysis, which has allowed for more robust conclusions, this is fundamentally a qualitative study. Its primary aim is to generate hypotheses and identify avenues for further research. The objective is to deepen our understanding of the phenomenon under study – public opinion about UBI among the middle class – and to guide future studies that can validate these preliminary conclusions and quantify the various relevant variables identified. The key findings, that should be understood as hypotheses, are outlined below.

7.2 Conclusions and Practical Implications

The first conclusion drawn from this study is the value of examining the components of universal basic income (UBI) acceptance in a more nuanced manner, rather than treating it as a single, monolithic variable, as is often done in survey-based studies. By using this qualitative approach, we have gained a more detailed understanding of UBI acceptance. Specifically, it is useful to consider two key components – perception of feasibility and desirability. These two aspects are associated with different arguments, actions, and challenges, and thus warrant distinct attention when considering potential interventions.

For instance, perception of feasibility seems to be heavily influenced by the concept of universality and the proper understanding of the tax redistribution mechanism for higher-income groups. As it is closely linked to the specific model of basic income being proposed, addressing perceptions of UBI feasibility requires careful explanation of these details.

Desirability, on the other hand, is more complex and multifaceted, as it is shaped by normative arguments and value judgments. While feasibility can be addressed through clear explanations of implementation mechanisms, desirability poses a greater challenge because it may involve shifts in societal values and norms.

Moreover, the results of this study suggest the existence of two distinct segments within the middle class regarding their level of awareness and understanding of universal basic income (UBI). The first segment, representing a threshold of acceptance, fails to grasp the concept and perceives it as nonsensical or absurd. These individuals are deeply embedded in a capitalist system and adhere strongly to the meritocratic model. Very often, this group is not even aware of the redistribution policies currently in place in their country, such as minimum income programs, neither they are familiar with their potential problems of implementation. It is worth noting that, in our sample, most participants fell into this category, and fundamental misconceptions about the nature of UBI persisted even after more than 20 min of discussion. This raises important questions about the validity of large-scale quantitative studies currently being conducted. First, it is unclear whether respondents fully grasp what UBI entails. Second, as mentioned above, these studies often treat acceptance as a monolithic variable, which limits the ability to derive meaningful, actionable insights.

In consequence, a key practical implication of these findings is a call for UBI researchers to critically reassess current methodologies of investigation of public opinion of UBI and incorporate qualitative perspectives more carefully before designing large-scale surveys.

Another practical implication, addressed to UBI advocacy organizations, is the need to address the initial threshold of acceptance in a specific manner. There is a clear need for basic education that differentiates UBI from other social policies, such as minimum income programs. Emphasizing the dissemination of evaluations of existing public policies is crucial, as these can help shape a more informed public understanding of UBI’s potential.

The media also bears significant responsibility in this regard, as it often neglects critical aspects of policy implementation. Greater media attention to these details is essential for fostering a more informed, nuanced public debate about UBI.

Then, in order to move beyond the acceptance threshold, it would be necessary to address underlying value systems, a challenging and long-term endeavor that extends far beyond the specific debate on UBI. Promoting values of citizenship and collaboration is crucial, as UBI acceptance requires these values to gain broader acceptance. Moreover, the presence of such values would likely enhance the UBI’s effectiveness, fostering greater reciprocity and reducing potential abuses, which in turn could address one of the common criticisms of UBI. Fostering these values, especially empathy and the ability to “put oneself in another’s shoes,” is essential. In this regard, implementing experiential learning initiatives could be a valuable strategy to promote empathy and a deeper understanding of the collective benefits of UBI.

Finally, in the Spanish context, the discussion around a basic income addressed to minors is particularly significant. It is essential to address the legitimate concerns that some segments of the population may have regarding its implementation. A more realistic approach to understanding public acceptance of this policy is needed, acknowledging that scepticism or hesitation may arise. Engaging with these doubts openly and providing clear, evidence-based explanations will be crucial for fostering informed debate and increasing the likelihood of wider acceptance of basic income for children in Spain.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the valuable contribution of the third-year students of the Bachelor’s degree in Organizational Engineering (2022–2023) for helping to conduct the interviews used in this study.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individuals included in this study, or their legal guardians or wards.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

Andrade, L. H. A. de, M. Ylikännö, and O. Kangas. 2022. “Increased Trust in the Finnish UBI Experiment – Is the Secret Universalism or Less Bureaucracy?” Basic Income Studies 17 (1): 95–115. https://doi.org/10.1515/bis-2021-0004.Suche in Google Scholar

Baez, S., D. Flichtentrei, M. Prats, R. Mastandueno, A. M. García, M. Cetkovich, and A. Ibáñez. 2017. “Men, Women… Who Cares? A Population-Based Study on Sex Differences and Gender Roles in Empathy and Moral Cognition.” PLoS One 12 (6): e0179336. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0179336.Suche in Google Scholar

Banerjee, A., M. Faye, A. Krueger, P. Niehaus, and T. Suri. 2020. “Effects of a Universal Basic Income during the Pandemic.” Innovations for Poverty Action Working Paper.Suche in Google Scholar

Baranowski, M., and P. Jabkowski. 2021. “Basic Income Support in Europe: A Cross-National Analysis Based on the European Social Survey Round 8.” Economics & Sociology 14 (2): 167–83. https://doi.org/10.14254/2071-789X.2021/14-2/9.Suche in Google Scholar

Barragué, B., L. Arroyo Jiménez, and M. C. Fernandez Aller. 2019. “La justificación normativa de la Renta básica universal desde la filosofía política y el derecho.” Revista Diecisiete 1: 81–94.10.36852/2695-4427_2019_01.02Suche in Google Scholar

Barrett, C. B., T. Garg, and L. McBride. 2016. “Well-Being Dynamics and Poverty Traps.” Annual Review of Resource Economics 8 (1): 303–27. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-resource-100815-095235.Suche in Google Scholar

Bay, A.-H., and A. W. Pedersen. 2006. “The Limits of Social Solidarity: Basic Income, Immigration and the Legitimacy of the Universal Welfare State.” Acta Sociologica 49 (4): 419–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001699306071682.Suche in Google Scholar

Berenguer, A. 2019. “Un experimento en la ciudad de Nueva York.” Revista Diecisiete: Investigación Interdisciplinar para los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible 1: 31–6.10.36852/2695-4427_2019_01.06Suche in Google Scholar

Berry, F. S., and W. D. Berry. 2018. “Innovation and Diffusion Models in Policy Research.” In Theories of the Policy Process, 253–97. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9780429494284-8Suche in Google Scholar

Bollain, J., I. Guerendiain-Gabás, M. Arnoso-Martínez, and Á. Elías Ortega. 2025. “Exploring Young People’s Attitudes towards Basic Income.” Basic Income Studies 19 (2): 253–86.10.1515/bis-2022-0030Suche in Google Scholar

Bueskens, P. 2017. Poverty-traps and Pay-Gaps: Why (Single) Mothers Need Basic Income. Views of a Universal Basic Income: Perspectives from across Australia, 42–51, Melbourne: The Green Institute.Suche in Google Scholar

Busso, S., A. Meo, and T. Parisi. 2019. “From Utopia to (Social) Policy Option? Attitudes towards Basic Income and Welfare Legitimacy in Europe.” Polis 33 (2): 241–66.Suche in Google Scholar

Calnitsky, D. 2018. ““If the Work Requirement Is Strong”: The Business Response to Basic Income Proposals in Canada and the US.” The Canadian Journal of Sociology/Cahiers Canadiens de Sociologie 43 (3): 291–315.10.29173/cjs29357Suche in Google Scholar

Carrero Domínguez, M. C., and M. Navas Parejo Alonso. 2019. “Renta básica y mujer. Incentivos y desincentivos. Efectos sobre la igualdad y los roles sociales.” Revista Diecisiete: Investigación Interdisciplinar para los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible (1): 37–56.10.36852/2695-4427_2019_01.07Suche in Google Scholar

Casado, J. M., and M. Sebastián. 2019. “Análisis crítico de la renta básica: Costes e incentivos. Aplicación al caso Español.” Revista Diecisiete: Investigación Interdisciplinar para los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible (1): 117–34.10.36852/2695-4427_2019_01.04Suche in Google Scholar

Choi, G. 2021. “Basic Human Values and Attitudes towards a Universal Basic Income in Europe.” Basic Income Studies 16 (2): 101–23. https://doi.org/10.1515/bis-2021-0010.Suche in Google Scholar

Chrisp, J., V.-V. Pulkka, and L. Rincón García. 2020. “Snowballing or Wilting? what Affects Public Support for Varying Models of Basic Income?” Journal of International and Comparative Social Policy 36 (3): 223–36. https://doi.org/10.1017/ics.2020.28.Suche in Google Scholar

Conesa, J. C., B. Li, and Q. Li. 2023. “A Quantitative Evaluation of Universal Basic Income.” Journal of Public Economics 223: 104881.10.1016/j.jpubeco.2023.104881Suche in Google Scholar

de Paz-Báñez, M. A., M. J. Asensio-Coto, C. Sánchez-López, and M.-T. Aceytuno. 2020. “Is There Empirical Evidence on How the Implementation of a Universal Basic Income (UBI) Affects Labour Supply? A Systematic Review.” Sustainability 12 (22): 9459. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229459.Suche in Google Scholar

De Wispelaere, J., and L. Stirton. 2012. “A Disarmingly Simple Idea? Practical Bottlenecks in the Implementation of a Universal Basic Income.” International Social Security Review 65 (2): 103–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-246X.2012.01430.x.Suche in Google Scholar

Dermont, C., and D. Weisstanner. 2020. “Automation and the Future of the Welfare State: Basic Income as a Response to Technological Change?” Political Research Exchange 2 (1): 1757387.10.1080/2474736X.2020.1757387Suche in Google Scholar

Díaz-Oyarzábal, J., J. A. Gimeno-Ullastres, and V. Gómez-Frías. 2019. “Modelos de financiación de una renta básica para España.” Revista Diecisiete: Investigación Interdisciplinar para los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible (1): 135–60.10.36852/2695-4427_2019_01.05Suche in Google Scholar

Diermeier, M., J. Niehues, and J. Reinecke. 2021. “Contradictory Welfare Conditioning—Differing Welfare Support for Natives versus Immigrants.” Review of International Political Economy 28 (6): 1677–704. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2020.1780294.Suche in Google Scholar

Eckel, C. C., and P. J. Grossman. 2008. “Men, Women and Risk Aversion: Experimental Evidence.” Handbook of Experimental Economics Results, 1, 1061–73.10.1016/S1574-0722(07)00113-8Suche in Google Scholar

Elgin, C., M. A. Kose, F. Ohnsorge, and S. Yu. 2022. “Understanding the Informal Economy: Concepts and Trends.” In The Long Shadow of Informality: Challenges and Policies, 35–91. USA: World Bank Group.10.1596/978-1-4648-1753-3_ch2Suche in Google Scholar

Fouksman, E. 2020. “The Moral Economy of Work: Demanding Jobs and Deserving Money in South Africa.” Economy and Society 49 (2): 287–311. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085147.2019.1690276.Suche in Google Scholar

García, L. R. 2022. “The Policy and Political Consequences of the B-Mincome Pilot Project.” European Journal of Social Security 24 (3): 213–29.10.1177/13882627221123347Suche in Google Scholar

Gibson, M., W. Hearty, and P. Craig. 2018. “Potential Effects of Universal Basic Income: A Scoping Review of Evidence on Impacts and Study Characteristics.” The Lancet 392: S36. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32083-X.Suche in Google Scholar

Gielens, E., F. Roosma, and P. Achterberg. 2023. “Between Left and Right: A Discourse Network Analysis of Universal Basic Income on Dutch Twitter.” Journal of Social Policy 54 (3): 939–60, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279422000976.Suche in Google Scholar

Gimeno-Ullastres, J. A. 2019. “De Rentas Mínimas a Renta Básica.” Revista Diecisiete: Investigación Interdisciplinar para los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible (1): 59–80.10.36852/2695-4427_2019_01.01Suche in Google Scholar

Gómez-Frías, V., T. Sánchez-Chaparro, D. Maeso-Álvarez, and J. Salgado-Criado. 2021. “Universal Basic Income in the Spanish Construction Sector: Engaging Businesses in a Public-Policy Debate.” Journal of Small Business Strategy 31 (1): 10–9.Suche in Google Scholar

Government of Spain. 2020 In press. “Real Decreto-ley 20/2020, de 29 de mayo, por el que se establece el ingreso mínimo vital.” Boletín Oficial del Estado, https://www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-2020-5493 (Accessed November 8, 2023).Suche in Google Scholar

Greener, I. 2005. “The Potential of Path Dependence in Political Studies.” Politics 25 (1): 62–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9256.2005.00230.x.Suche in Google Scholar

Hall, R. P., R. Ashford, N. A. Ashford, and J. Arango-Quiroga. 2019. “Universal Basic Income and Inclusive Capitalism: Consequences for Sustainability.” Sustainability 11 (16): 4481.10.3390/su11164481Suche in Google Scholar

Hamilton, L., M. Despard, S. Roll, D. Bellisle, C. Hall, and A. Wright. 2023. “Does Frequency or Amount Matter? an Exploratory Analysis the Perceptions of Four Universal Basic Income Proposals.” Social Sciences 12 (3): 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12030133.Suche in Google Scholar

Hamilton, L., and J. P. Mulvale. 2019. ““Human Again”: The (Unrealized) Promise of Basic Income in Ontario.” Journal of Poverty 23 (7): 576–99.10.1080/10875549.2019.1616242Suche in Google Scholar

Harrell, F. E. 2001. Regression Modeling Strategies: With Applications to Linear Models, Logistic Regression, and Survival Analysis, 608. New York: Springer.10.1007/978-1-4757-3462-1Suche in Google Scholar

Herd, P., and D. P. Moynihan. 2019. Administrative burden: Policymaking by Other Means. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.10.7758/9781610448789Suche in Google Scholar

Herke, B., and L. Vicsek. 2022. The Attitudes of Young Citizens in Higher Education towards Universal Basic Income in the Context of Automation—A Qualitative Study. International Journal of Social Welfare, 31(3), 310–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijsw.12533Suche in Google Scholar

Hosmer, D. W.Jr., S. Lemeshow, and R. X. Sturdivant. 2013. Applied Logistic Regression. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons.10.1002/9781118548387Suche in Google Scholar

Hoynes, H., and J. Rothstein. 2019. “Universal Basic Income in the United States and Advanced Countries.” Annual Review of Economics 11 (1): 929–58.10.1146/annurev-economics-080218-030237Suche in Google Scholar

Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE). 2022. Encuesta de estructura salarial. https://www.ine.es/dyngs/Prensa/avEES2022.htm.Suche in Google Scholar

Kangas, O., S. Jauhiainen, M. Simanainen, M. Ylikännö. 2019. “The Basic Income Experiment 2017–2018 in Finland: Preliminary Results.” Reports and Memorandums of the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health 2019:9. Helsinki: Ministry of Social Affairs and Health.Suche in Google Scholar

Koistinen, P., and J. Perkiö. 2014. “Good and Bad Times of Social Innovations: The Case of Universal Basic Income in Finland.” Basic Income Studies 9 (1–2): 25–57. https://doi.org/10.1515/bis-2014-0009.Suche in Google Scholar

Laenen, T., A. Van Hootegem, and F. Rossetti. 2023. “The Multidimensionality of Public Support for Basic Income: A Vignette Experiment in Belgium.” Journal of European Public Policy 30 (5): 849–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2022.2055112.Suche in Google Scholar

Lau, R. R., and D. P. Redlawsk. 2001. “Advantages and Disadvantages of Cognitive Heuristics in Political Decision Making.” American Journal of Political Science 45: 951–71.10.2307/2669334Suche in Google Scholar

Lee, S. 2021. “Politics of Universal and Unconditional Cash Transfer: Examining Attitudes toward Universal Basic Income.” Basic Income Studies 16 (2): 191–208. https://doi.org/10.1515/bis-2021-0013.Suche in Google Scholar

Lewin, K. 1951. Field Theory in Social Science. New York: Harper and Row.Suche in Google Scholar

Linnanvirta, S., C. Kroll, and H. Blomberg. 2019. “The Perceived Legitimacy of a Basic Income Among Finnish Food Aid Recipients.” International Journal of Social Welfare 28 (3): 271–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijsw.12362.Suche in Google Scholar

Lombardozzi, L. 2020. “Gender Inequality, Social Reproduction and the Universal Basic Income.” The Political Quarterly 91 (2): 317–23.10.1111/1467-923X.12844Suche in Google Scholar

Martinelli, L. 2017 In press. “Assessing the Case for a Universal Basic Income in the UK.” IPR Policy Brief, https://www.bath.ac.uk/publications/assessing-the-case-for-a-universal-basic-income-in-the-uk/attachments/ipr-assessing-the-case-for-a-universal-basic-income-in-the-uk.pdf (Accessed August 13th, 2025).Suche in Google Scholar

Miles, M. B., and A. M. Huberman. 1994. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. Washington DC: Sage.Suche in Google Scholar

Miller, J. 2021. Universal Basic Income and Inflation: Reviewing Theory and Evidence. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3920748.Suche in Google Scholar

Mulvale, J. P. 2019. “Social-ecological Transformation and the Necessity of Universal Basic Income.” Social Alternatives 38 (2): 39–46.Suche in Google Scholar

Nettle, D., E. Johnson, M. Johnson, and R. Saxe. 2021. “Why Has the COVID-19 Pandemic Increased Support for Universal Basic Income?” Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 8 (1): 79. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00760-7.Suche in Google Scholar

Oldenburg, B., and K. Glanz. 2008. “Diffusion of Innovations.” Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice 4: 313–33.Suche in Google Scholar

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). 2019. Under Pressure: The Squeezed Middle Class. Paris: OECD Publishing.Suche in Google Scholar

Parolin, Z., and L. Siöland. 2020. “Support for a Universal Basic Income: A Demand–Capacity Paradox?” Journal of European Social Policy 30 (1): 5–19.10.1177/0958928719886525Suche in Google Scholar

Patulny, R., and B. Spies-Butcher. 2023. “Come Together? the Unusual Combination of Precariat Materialist and Educated Post-materialist Support for an Australian Universal Basic Income.” Journal of Sociology: 14407833231167222. https://doi.org/10.1177/14407833231167222.Suche in Google Scholar

Pierson, P. 2000. Increasing Returns, Path Dependence, and the Study of Politics. American Political Science Review 94 (2): 251–67. https://doi.org/10.2307/2586011.Suche in Google Scholar

Ramirez, F. O., and J. Boli. 1987. “The Political Construction of Mass Schooling: European Origins and Worldwide Institutionalization.” Sociology of Education 60: 2–17.10.2307/2112615Suche in Google Scholar

Relja, R., I. Reić-Ercegovac, and B. Blažević. 2015. “Perception of Basic Income in Relation with Some Socio-Demographic Features in the Area of Split-Dalmatia County.” Sociologija 57 (3): 459–75.10.2298/SOC1503459RSuche in Google Scholar

Rincon, L. 2023. “A Robin Hood for All: A Conjoint Experiment on Support for Basic Income.” Journal of European Public Policy 30 (2): 375–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2021.2007983.Suche in Google Scholar

Rogers, E. M. 1983. Diffusion of Innovations. New York: The Free press.Suche in Google Scholar

Rogers, P. 2014. “Theory of Change.” Methodological Briefs: Impact Evaluation 2 (16): 1–14.Suche in Google Scholar

Roosma, F., and W. J. H. van Oorschot. 2020. “Public Opinion on Basic Income.” Journal of European Social Policy 30 (2): 190–205. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928719882827.Suche in Google Scholar

RTVE. 2020. La Renta Básica Universal. https://www.rtve.es/play/videos/para-todos-la-2/renta-basica-universal-posible-reportaje-varios-expertos-economistas/5479485/ (accessed November 8, 2023).Suche in Google Scholar

Rubião, O. M. 2021. “Universal Basic Income in a Developing Economy with a Large Informal Sector.” Brazilian Review of Econometrics 41: 44–68.10.12660/bre.v41n12021.84425Suche in Google Scholar

Saldaña, J. 2021. “Coding Techniques for Quantitative and Mixed Data.” In The Routledge Reviewer’s Guide to Mixed Methods Analysis, 151–60. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.10.4324/9780203729434-14Suche in Google Scholar

Salguero, M. 2024. La renta básica universal y el derecho de los niños a un nivel de vida adecuado. https://www.redrentabasica.org/rb/la-renta-basica-universal-y-el-derecho-de-los-ninos-a-un-nivel-de-vida-adecuado/.Suche in Google Scholar

Schulz, P. 2017. “Universal Basic Income in a Feminist Perspective and Gender Analysis.” Global Social Policy 17 (1): 89–92.10.1177/1468018116686503Suche in Google Scholar

Shin, Y.-K., T. Kemppainen, and K. Kuitto. 2021. “Precarious Work, Unemployment Benefit Generosity and Universal Basic Income Preferences: A Multilevel Study on 21 European Countries.” Journal of Social Policy 50 (2): 323–45. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279420000185.Suche in Google Scholar

Stadelmann-Steffen, I., and C. Dermont. 2020. “Citizens’ Opinions about Basic Income Proposals Compared – A Conjoint Analysis of Finland and Switzerland.” Journal of Social Policy 49 (2): 383–403. Cambridge Core https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279419000412.Suche in Google Scholar