Abstract

Based on the two postulates of the invariance of both the laws of physics and light speed in inertial frames, Einstein revolutionised the prevalent conceptions of space and time in the Special Theory of Relativity, which is not however without difficulties, due to gaping holes in its philosophical foundations. The first postulate is an unjustified and clumsily drafted extension of Galilean Relativity, while the second postulate, if interpreted as meaning that the speed of light will not be altered by a moving frame, does not lead to Lorentz transformations, but just reveals that a light ray is not transported by a moving frame. Reference frames involving light propagation do not exhibit the equivalence inherent in inertial frames, and hence could be classified as seemingly-inertial, being some category of non-inertial frames. Either equivalence, including simultaneity in both moving and stationary frames, is a defining characteristic of inertial frames, or else if inertial frames allow inequivalence, then they are not indistinguishable, which is a contradiction. All along, the definitions of “frames of reference,” “inertial frames,” and “simultaneity” and the “legal” drafting of the two postulates play a crucial role in the development and consistency of the Theory, almost as much as the thought experiments and the mathematics.

1 Motion, rest, and commonality of motion

The motion of objects through space and time has always been one of the main areas of study in physics and philosophy. Galilean and Newtonian Relativity established a special correspondence between two states that would at first sight not only bear little resemblance to each other, but are generally considered as extreme opposites – motion and rest.

While basic intuition would dictate that an object (or a collection of objects) situated in a stationary frame such as a stationary ship or train, would behave differently from the same object (or collection of objects) situated in a moving frame, such as a sailing ship or moving train; yet, Galilean Relativity established a philosophical correspondence and a physical and mathematical correlation between the two inertial frames – the laws of physics, and hence the objects’ behaviour are the same in a stationary as well as a moving frame, as long as the velocity of the moving frame is uniform.

The behaviour of the same object/s in the two inertial frames – in motion and at rest – is equivalent and indistinguishable as long as the moving frame proceeds with constant speed and there is no acceleration. And if more than one object is situated within the frames, their relations with respect to (w.r.t) each other will also be conserved, independent of whether the frame is in motion or at rest.

The consequence of this, the essence of Galilean and Newtonian Relativity, means that one cannot distinguish a moving frame from a stationary one by observing the behaviour of the objects contained by them. Thus, in their epic treatise Dialogue Concerning Two Chief World Systems, Galilei and Drake (1953) examine the motions of various objects including “flies, butterflies, and other small flying animals,”[1] situated below decks and examine their motions first in a stationary, then in a moving ship, and discovers that no distinction can be drawn between the two frames and conclude that they are equivalent and indistinguishable. A butterfly flying below decks from stern to bow and vice versa will cover the same distance at the same time, hence at the same speed, whether the ship is moving or at rest.

Indeed, in what is probably the most overlooked, yet most important justification of the Relativity principle, Galileo explains the underlying cause of these effects – commonality of motion between the ship and its contents – “The cause of all these correspondences of effects is the fact that the ship’s motion is common to all the things contained in it, and to the air also.”

As long as the motion of the reference frame (Galilean ship) is uniform and communicated and transferred to the motion of its contents (inter alia the Galilean butterfly), such that it becomes common to both, the behaviour of the contents in the frame when at rest (butterfly in the ship at rest) will be equivalent and indistinguishable from the behaviour of the same contents in the frame when in motion (butterfly in the moving ship). Consequently, one cannot tell, and no experiment can be done to establish, if a frame is in motion or at rest, from the behaviour of the objects contained in them, since in both of the two equivalent frames, the laws of motion and kinematics, which were the known laws of physics at the time, take the same form [vide conclusion #5].

The imagery of the sailing ship was mentioned by Galileo in the context of the debate as to whether the Earth moved or stood still, and such a simple principle once established was generalised as a philosophical justification as to why one cannot detect the Earth’s motion nor distinguish a moving Earth from a stationary one, from the behaviour of objects on its surface, since such objects being transported along by a moving planet, would behave in the same manner if the Earth, idealised as an inertial frame, is in motion, as well as were it to be at rest.[2] Since the inertial frames are equivalent and indistinguishable, one cannot distinguish a moving Earth from a stationary Earth, just from the behaviour of the objects on its surface, and this is in conformity with everyday experience, since we have no sensation of the motion of the Earth in spite of it spinning and revolving [vide conclusion #5].

But what is an inertial frame that gives rise to this equivalence? Since an inertial frame is not a physical object found in nature, but an abstract philosophical structure translated into mathematical terms, its nature is heavily dependent upon, and constituted by its definition. Its being and essential nature will be determined by the way it is defined, both in classical and Special Relativity (vide conclusion #1).

2 Inertial frames of reference as containers and the problem with light

When Newton reiterated the principle of Relativity in Corollary 5 of his Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica (Newton 1687) “the motions of bodies included in a given space are the same among themselves, whether that space is at rest, or moves uniformly forward in a right line without any circular motion,” he not only retained the Galilean principle incorporating it into his Laws of Motion, but even borrowed the metaphor of the moving ship, – “a clear proof of which we have from the experiment of a ship; where all motions happen after the same manner, whether the ship is at rest, or is carried uniformly forwards in a right line,” and emphasising the importance of “included in a given space,” which in some texts is translated as “confined in a given space.”

An inertial frame of reference is thus a chunk of space that obeys Newton’s Law of inertia, hence the nomenclature, in the sense that an object at rest will remain at rest in such a frame and an object in motion will stay in that same state of motion within the frame unless acted upon by an external force. Since both frames (moving and stationary) must obey Newton’s Law of Inertia, to qualify as inertial frames and give rise to the correspondence of equivalence, it follows as a corollary that if a body in the stationary frame behaves differently in the moving frame, due to acceleration or other reasons, then the frames’ equivalence is broken by the emergence of fictitious forces, and hence the frames become non-inertial.

Thus, while apparently simple at first glance, the concept of an “inertial frame of reference” is quite a complex philosophical issue. A vast literature about the subject with contributions by Huygens, Lange, Leibniz, Mach, Einstein and Poincare’ amongst others, still left unresolved questions, and a debate wide open till the present day. However, it would seem that amongst the defining criteria for inertial frames to exist, the following are essential properties:

a frame of reference at rest or moving at uniform speed which could also contain and transport other objects inside it, which in turn might be either moving or at rest;

commonality of motion between the container (frame of reference), moving or at rest, and the contained objects, if any, and their motions, leading to correspondence of effects, in such a manner that the Law of Inertia applies and no fictitious forces arise.

The motion of the container is not always shared by its contents, and all depends not just on the nature and characteristics of the container or the contents but also on the interaction between container and contents, as well as the constancy or otherwise of the speed of the container. No commonality of motion means no transportation and no inertial frames. A frame labelled as inertial might determine the way its contents behave, but the behaviour of the contents w.r.t the container will also determine if a frame can be labelled as inertial or not. It works both ways, in a self-referential manner. The inertial nature or otherwise of the frame will dictate the way the contents will behave, but on the other hand the behaviour of the contents will determine if a frame is inertial or not. It is a question of self-reference leading possibly to infinite regress. (vide conclusion #2, #6, and #7).

This Principle of Relativity correlating stationary and uniformly moving frames was firmly established and accepted for almost 300 years, until Einstein started investigating electrodynamics and discovered that while Newton’s laws of Mechanics were invariant under Galilean transformations, Maxwell’s Laws of Electrodynamics and the Laws of Optics, were not. The speed of light in empty space, which, experiments by Michelson and Morley, Fizeau, and others had established, was constant, was refused to be incorporated into the philosophical, physical, and mathematical system of Galilean Relativity based on the equivalence of inertial frames and translated mathematically by addition (combination) and subtraction (separation) of velocities of frames and their contents, since a fixed speed of light allows nothing, not even the speed of the reference frame as container, to be added or subtracted to it.

The conundrum Einstein faced was that unlike corporeal bodies, electromagnetic radiation refused to participate in commonality of motion and correspondence of effects with a moving container in which it propagated, but unfortunately, he posited the question in the wrong manner, focusing on maintaining a fixed speed of light in all inertial frames, without realising that light was problematic for inertial frames, the two being possibly incompatible (refer conclusion #7).

While the speed of a butterfly could be added or subtracted to the speed of the ship, depending on the direction of motion, when observed from the shore, the speed of light could not be added or subtracted to that of a moving ship, when observed also from the shore, and furthermore, while the speed of butterfly w.r.t the ship was unaltered in both stationary and moving ships, the speed of light seemed to change w.r.t a moving ship depending on the direction of motion. In tackling this conundrum, Einstein focused on devising a system that would yield a constant speed of light in all frames, but failed to realise that the equivalence and indistinguishability features which are the hallmark of inertial frames did not materialise in frames involving light, and hence the frames were doubtfully inertial in nature, fully non-inertial at worst, or seemingly-inertial at best. [vide conclusion #5 and #12].

3 Excluding inertial frames – above board – non-inertial or seemingly-inertial

Thus, inertial frames as containers required more than just a uniform speed to subsist – they required commonality of motion which leads to correspondence of effects. Indeed it was Galileo himself who in laying down the foundations of Relativity, established also a criterion of exclusion, retaining the example of a ship sailing at uniform speed, he goes on to exclude certain situations from the purview of the Principle he had just laid down – “That is why I said you should be below decks; for if this took place above in the open air, which would not follow the course of the ship, more or less noticeable differences would be seen in some of the effects noted. No doubt the smoke would fall as much behind as the air itself. The flies likewise, held back by the air, would be unable to follow the ship’s motion if they were separated from it by a perceptible distance……But the difference would be small as regards the falling drops and as to the jumping and throwing it would be quite imperceptible.”

In this excerpt, which is also often overlooked, Galileo is establishing a criterion of exclusion for the principle of Relativity due to equivalence breaking – above board, unlike below decks, the behaviour of the objects on the moving ship can be distinguished from that of the same objects when the ship is at rest. Galileo is here stating, although not so emphatically, that uniform speed was not enough for a moving ship to constitute an inertial frame. The other essential requirement was a particular interaction between the frame of reference and its contest described as “commonality of motion.” Even though the ship moves at uniform velocity w.r.t the shore, and there is no acceleration by the moving frame, Galileo excludes the situation above board from the purview of inertial frames and relativity.

Galileo distinguishes between inertial frame (below decks) and the non-inertial frame (above board) – once above board, there will be differences ranging from huge, to small, to existent but almost imperceptible, then the frame is no longer inertial, not due to the speed of the ship, which remains constant, but due to the lack of commonality of motion between the ship and the objects on board, between the container (the frame of reference) and its contents, leading to the extinguishment of the correspondent equivalence between the two frames, moving and stationary (vide conclusion #2).

Galileo positioned the flies, butterflies, smoke, and other objects in a sort of perforated, uninsulated space of reference above board the moving/stationary ship, rather than as two separate reference frames moving w.r.t each other. For the purposes of comparative analysis, the inertial below decks scenario of the ship, moving or at rest, can be conceptually abstracted into an insulated glass box, whereas the above board scenario of the ship, moving or at rest, can be abstracted into an uninsulated cage. The cage imagery captures the essence of the situation above board and distinguishes it from the one below decks. For all intents and purposes, one could envision the “cage” as just an abstract three-dimensional co-ordinate system which does not enclose and insulate the space within it and does not transport its contents by commonality of motion and correspondence of effects (vide conclusion #7).

Transportation in this context has the same meaning as commonality of motion and correspondence of effects, whereby the component of velocity of the container is shared in quality and magnitude by the contents (vide conclusion #2).

While the abstract glass box is an insulated chamber transferring its motion to its contents and transporting them along, the abstract cage is a perforated, uninsulated chamber that fails to transfer its motion to its contents and fails to transport them along. In the first instance, there is the Galilean correspondence of effects, while in the second, there is not. There is a different interaction between the container and its content (vide conclusion #2).

The cage imagery represents a valid frame of reference, in which even though the frame is not accelerated, an object in the frame will experience fictitious forces and slide backward when the frame moves forward and vice versa, in a situation similar to that of fictitious forces, but which arises, in this case, not due to acceleration, but due to the particular interaction between frame and contents. Constant speed is not the only defining property for inertial frames.

For while the mobile glass box is sealed and insulated from the wider “stationary” frame, dragging the enclosed space along with it, on the other hand, the space within the perforated cage is neither sealed nor insulated from the wider “stationary” frame, and the cage does not drag the “enclosed” space along with it, just like dragging a perforated frame does not transport its contents, dragging the boundaries, an imaginary co-ordinate system, but not the space and contents within.

To a corporeal object contained, the glass box is an inertial frame, the cage is not, even though both move at the same constant speed, while the glass box drags along the space inside it, the perforated cage does not. But to an incorporeal body like electromagnetic radiation including light, neither the glass box, nor the cage are an insulated body, and none of them will transport electromagnetic radiation or participate in commonality of motion or correspondence of effects. Electromagnetic radiation cannot be transported by a moving material container and it inhabits the frame of reference of the fixed stars, even when propagating inside corporeal containers such as ships, trains, and moving rooms (vide conclusion #6, #7, and #9).

Inertial frames take just one form, but non-inertial frames may be of various kinds. When it comes to inertial frames, a miss is as good as a mile and a slight deficiency excludes inertial frames and their inherent and intrinsic properties. On the other hand, the category of non-inertial frames can include a wide variety of frames from outright non-inertial to just slightly non-inertial.

Below decks, travelling from the stern to bow (and vice versa), the butterfly will travel the same distance in the same time, at the same velocity w.r.t the ship, in both directions, both when the ship is moving and at rest. Its velocity w.r.t the shore will result in addition (ship + butterfly) from stern to bow and subtraction (ship-butterfly) from bow to stern. This is typical inertial equivalence.

On the other hand, in the non-inertial above board frame, the butterfly will have a longer distance to travel to reach the bow since it is moving away from the butterfly, and less distance to travel in the opposite direction since the stern is approaching it in that case. This results both when viewed from the “moving” frame of the ship and from the “stationary” frame of the shore. Speed w.r.t shore will be identical in both directions, both when the ship is moving and at rest, whereas w.r.t the moving frame, velocities will subtract from stern to bow and add in the opposite direction.

One cannot fail to notice that while in the inertial frame, velocities add up when container and contents travel in the same direction and subtract when in different directions, in non-inertial frames, the opposite happens. This is an important consideration, since in the case of inertial frames one is dealing with the speed of transportation leading to a material change in the actual speed, whereas in non-inertial frames, it is a change in the speed of approach/recession, a change in the observed speed [vide conclusion #2].

Einstein will substitute the Galilean butterfly with a light ray which will move across a moving rigid rod, a moving co-ordinate system, a moving room, and a moving train. In all cases, the butterflies and light rays move in frames of reference as containers, be they rods, rooms, trains, ships, or abstract co-ordinate systems.

Now, if Einstein’s light ray is shone across the Galilean ship, it will be seen to behave very similar to the above board butterfly, since in the absence of transportation, the light ray will have longer and shorter distances to travel, respectively, from stern to bow and vice versa. Notwithstanding the enormous differences between a corporeal butterfly and an incorporeal light ray, certain similarities can be noted. The light ray will retain its speed w.r.t the “stationary” frame both when the ship is moving and at rest, and the motion of the ship will not influence the speed of the light ray (and the butterfly when above board). One can say that both the light ray and the butterfly will retain a constant speed w.r.t shore if emitted in a stationary as well as a moving ship, a statement much in line with the Second Postulate of Special Relativity [vide conclusion #8].

For corporeal bodies, below decks is sealed and insulated from the wider stationary frame, dragging the enclosed space along with it, while the frame of reference above board is neither sealed nor insulated from the wider “stationary” frame, and does not drag the “enclosed” space along with it. To the object contained, below decks is an inertial frame, while above board is not, even though both move at the same constant speed. On the other hand, for electromagnetic radiation, including the light ray, neither space is an insulated one and the light ray inhabits the wider “stationary” frame of the fixed stars, retaining its speed fixed w.r.t that frame, independent of the motion of the ship. But can such a frame be deemed to be inertial? [vide conclusion #8].

4 Non-inertial frames, fictitious forces, and equivalence breaking

Now, if the Galilean ship were to accelerate instead of sailing smoothly at constant speed, the below decks’ equivalence would also be broken, and all objects therein contained would experience a fictitious force in the direction opposite to that of the acceleration, if the ship accelerates forward, all objects including butterflies, would experience a backwards “pull.” Objects situated below decks of an accelerated ship would behave similarly, in quality and modality of motion if not in quantity, to objects situated above board an unaccelerated, uniformly moving ship – in both cases, one can tell a moving ship from a ship at rest.

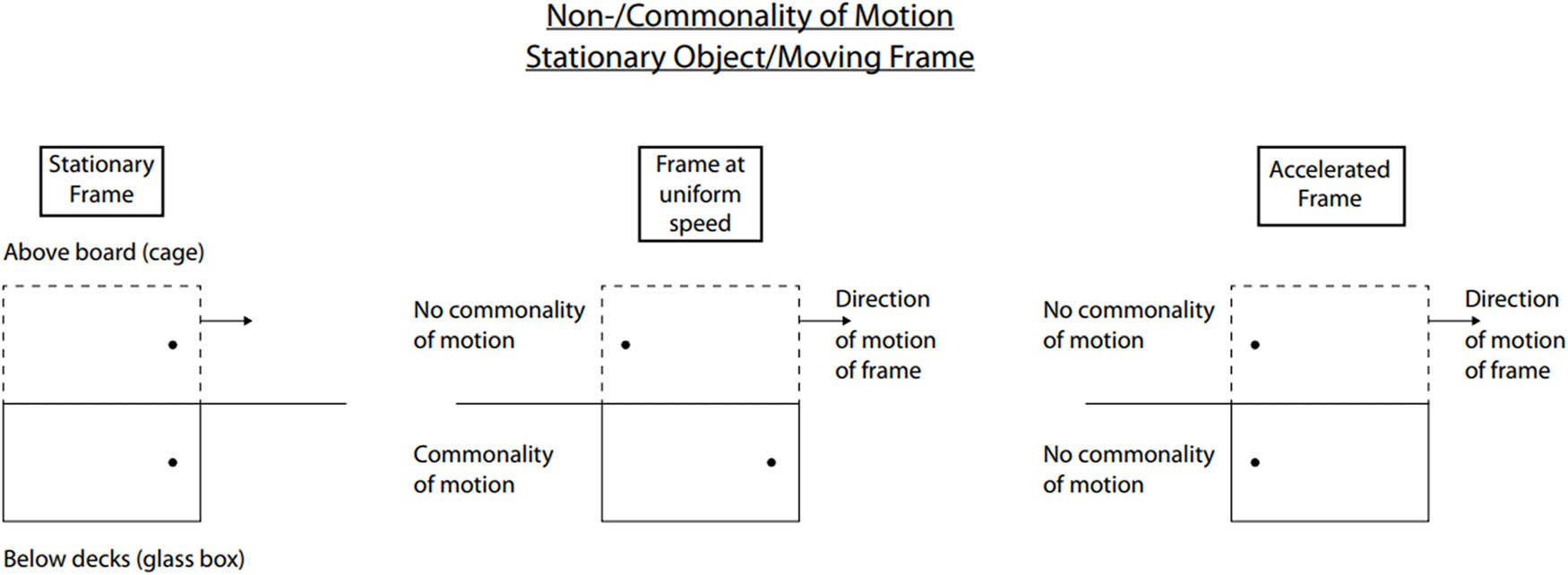

Since it is not an actual force which is being imparted on the objects themselves but a kinematical effect, a consequence of their inertia, which resists an abrupt change in the state of rest or uniform motion, it is known as a fictitious or pseudo force, which is a consequence of the relative motion between the frame and its contents. The butterfly in an accelerated below decks will be in a similar situation as the butterfly in the unaccelerated, uniformly moving above board, and since equivalence is broken in the corresponding stationary frames in both scenarios, one can easily distinguish a stationary frame from a moving one, in both cases (Figure 1).

The inertial nature or otherwise of the frame is determined not just by the velocity but also by the interaction of the “container” with the “contents,” whether the contents share the motion of the container, which then becomes common to both, hence commonality of motion, and a process of transportation ensues or else the contents do not share the motion of the container and hence, there is no commonality of motion. Neither in accelerated frames nor in the above board situation does commonality of motion ensue with regards to corporeal bodies, whereas it ensues in the below decks sealed containers scenarios. As regards electromagnetic radiation, there is no commonality of motion with any physical container whatsoever, moving at uniform or accelerated speed. Commonality of motion is almost an exception wherein one body transfers its motion to another body, which it contains.

In reality, also, and this is of great relevance to the current discussion, one could argue that the fictitious force gives rise to a “fictitious” velocity of the contents themselves w.r.t the accelerated frame below decks or unaccelerated frame above board, which in reality is due and should be attributed to the motion of the frame, not that of the contents. Now, if such a force is called “fictitious force” because it is not due to a real force imparted on the object or interaction with the frame, should not the resultant velocity be termed “fictitious” velocity and also should not the simple relative velocity be termed “fictitious” velocity since the observed velocity is not the real velocity but one due to a particular vantage point of observation and the relative motion between bodies without an actual variation in their individual speeds?

Relative velocity (in the absence of transportation) in some respects could also be envisaged as a fictitious velocity – if a car travels at a certain speed w.r.t to the road, but another car travelling at the same speed w.r.t the road observes it to be at rest w.r.t itself, is not that a fictious zero speed – if a car seems to be at rest, when it is moving, could not that be considered as “fictitious” velocity? [vide conclusion #3].

Thus, while the seemingly-inertial character of frames involving light is not due to the acceleration of the frame but due to the lack of commonality of motion and non-transportation, there is an important kinematical similarity between the two – it is easy to distinguish between a stationary and moving frame since there is no equivalence and non-equivalence excludes inertial frames, which must comply to strict requirement to qualify as such, whereas non-inertial frames can be of various kinds allowing of degrees of divergence from inertial frames. Frames involving light which are not strictly inertial and could constitute some sub-category of non-inertial frames, could be labelled as seemingly-inertial, for lack of a better term, and even though in the category of non-inertial frames, they are most similar to inertial frames, they are almost inertial but not quite, and a miss is as good as a mile [vide conclusion #7, #9, and #12].

Inequivalence means that two simultaneous events in the stationary frame will not be simultaneous in the accelerated frames, as well as frames involving light even if unaccelerated, and if equivalence and simultaneity in both frames are defining characteristics of inertial frames, then both the accelerated frames and those involving light are like non-inertial. The distinguishability between the stationary and moving frames is a consequence of the non-equivalence of the frames [vide conclusion #12].

In non-inertial frames, it is not the object contained in the frame that is really moving, but the frame w.r.t the object; in the inertial case, it is not the stationary frame that is moving but the other one, even though each might consider the other to be moving. In the seemingly-inertial frames, light is not transported by the moving frame although it moves at constant speed. Inertial frames exhibit commonality of motion, whereas non-inertial frames, for one reason or another, do not [vide conclusion #3, #4, and #6].

5 Reference frames, inertial or otherwise – from physical containers to abstract co-ordinate systems

Let us now examine Einstein’s transformation of the Galilean reference frame. In developing Special Relativity from Galilean Relativity, Newton’s “included in a given space” and Galileo’s “below decks” frame of reference were transformed by Einstein into “a co-ordinate system” consisting of “three rigid rods,” thereby seemingly losing their classical enclosed and insulated nature and characteristic commonality of motion with their contents, in the process.

In The Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies (Einstein 1905), transcends the purely physical “enclosed spaces” as reference frames and ushers into the abstract mathematical – “in ‘stationary’ space take two systems of co-ordinates, i.e. two systems each of three rigid material lines, perpendicular to one another, and issuing from a point. Let the axes of X of the two systems coincide, and their axis of Y and Z respectively be parallel.” The use of the expression “three rigid material lines” almost gives the impression that while postulating a mathematical construction, he is trying to blow real physical life into it by emphasising “rigid” and “material” in qualifying the lines.

Then, in Relativity – the Special and General Theory (Einstein 1915), he retains the same structure of the inertial frame – we can imagine this reference-body supplemented laterally and in a vertical direction by means of a framework of rods, so that an event which takes place anywhere can be localised with reference to this framework…….In every such framework we imagine three surfaces perpendicular to each other marked out, and designated as “co-ordinate planes” (“co-ordinate system”). A co-ordinate system K then corresponds to the embankment, and a co-ordinate system K' to the train.

Such an abstract structure is different from Galileo and Newton’s physical enclosed spaces and it seems to be a hybrid between the mathematical Cartesian co-ordinate system in three dimensions and a chunk of real physical space, a space of reference, as it were, contained in the space traced out by the three rigid rods. It cannot be excluded that in his excessive zeal to abstract concepts, Einstein was undecided as to the exact nature of this hybrid structure he had created – a frame of reference partially mathematical partially physical, and it is from this lack of clarity, which does not only contaminate the inertial nature of the frames but even the essence and definition of the frame of reference itself, that some of the complications and obscurities will arise, most important of all – is this structure inertial or not, especially when light propagation is involved? [vide conclusion #1].

Even Arthur I Miller[3] showed considerable scepticism about Einstein’s inertial frame conceptualisation, indeed he states that “Even though the inertial system – composed of rigid rods and an associated isotropic and homogenous space – was a logical inconsistency, nevertheless its use as a concept enabled Einstein to connect empirical data in a new way; this, after all, was the role he assigned to concepts.”

In spite of different approaches and material differences, there is one feature which is common to Galilean, Newtonian, and Einstein’s frames of reference – they are all intended as containers, they all act as containers in which light rays propagate and butterflies fly. But as we have already seen there are different types of containers, different kinds of contents, and different kinds of interactions between containers and contents, inertial, non-inertial, and other variants in between [vide conclusion #2].

6 Fabric of space and the constant speed of light

Einstein referred to the Michelson Morely experiment in his 1905 paper as “the unsuccessful attempts to discover any motion of the earth relatively to the “light medium.” The scope of the notorious experiment was to detect the hypothesised medium through which light allegedly propagated – the luminiferous ether – and its effect on light speed. Since light was a wave, the prevailing science of the time believed, it must be oscillating in some medium, arbitrarily labelled as the ether, and since Earth had a relative speed w.r.t such a medium, an ether wind would arise, and since the Earth would at times be moving parallel to the ether wind and at other times at different angles to it, this should cause the speed of light to vary depending on the direction of the ether wind.

However, the predicted hypothesised results did not materialise and the outcome of the experiment was interpreted to indicate not only the inexistence of ether, but also that the speed of light in empty space was fixed and did not depend on the speed of the emitter or detector, in other words, the speed of the emitter/detector could not be added/subtracted to the speed of light. It is very ironic that while all treatises on Special Relativity usher with the Michelson Morley experiment’s banishment of ether, no time has been wasted since the experiment, to populate the vacuum of free space with all sorts of exotic particles and mysterious forms of matter and energy such as the Higgs boson, dark energy, and dark matter, which are just quantum substitutes to the elusive ether as that granular fabric of space through which light propagates.

After all, the speed of light according to Maxwell’s equations is a consequence of the permeability and permittivity of free space, which possibly reveal just as much about the fabric of empty space, as they do about the inherent nature of light itself, and one might argue that the nature of the fabric of space itself is inbuilt in Maxwell’s equations themselves through the permeability and permittivity concepts.

But there was another aspect of the constant speed of light, which related to the inherent nature of light itself, rather than the medium in which it propagated, that could not be incorporated in Galilean Relativity. And this aspect was not that the speed of light is independent of the speed of the emitting source, since this is not peculiar to light, but a characteristic of waves in general, including sound waves, which obey the Galilean transformations.

So, what aspect of the constant speed of light was causing tensions with Galilean Relativity such that Einstein believed a new Theory had to be developed? It was the fact that unlike sound, apparently, light did not require a medium through which to propagate, and hence all observers in any state of motion had to observe light travelling at one constant speed.

7 Legislating the first postulate – a failure in “legal” drafting

If the speed of light was to remain constant independent of the speed of the emitter/detector and the speed of the observer, Einstein was facing this conundrum – if the laws of mechanics applied equally in a moving as well as a stationary frame when inertial, what changes were needed to the Galilean formalism to fit in light propagation and its constant speed in such a way as to retain a constant speed of light in moving and stationary frames?

If the category of laws that were invariant in inertial frames was to be widened from the laws of Mechanics to those of Optics and Electromagnetism, then Galilean Relativity had to be modified, in such a way as to retain a constant speed of light both in the stationary and the moving frame. Without enquiring into the justification or validity of extending the principle of relativity to light propagation, he proceeded to extend the category “laws of motion” in Galilean Relativity to “all laws of physics” in Special Relativity, and since the constancy of the speed of light was to be considered a law of physics, after Fizeau, Michelson Morley, and others, it automatically fell within the purview of the new postulate as unjustifiably modified.

However, his unjustified overhaul of the Galilean Relativity Principle did not end with this extension. He proceeded to turn it into a law that governs the validity of other physical laws. Without any philosophical justification for establishing such a rule of validity and extending it to all physical laws, Einstein arbitrarily and indiscriminately turned a principle based on empirical evidence and observation, and applicable limitedly to the laws of motion, into a principle applicable to all laws of physics, and proceeded to turn it into a law about the validity of all physical laws.[4] He not only altered its extent of applicability as a Galilean postulate, but also its essence – all laws of physics had to be invariant in all inertial frames. Such a radical overhaul necessitated a solid philosophical justification, which is completely missing, leaving a large gaping lacuna in the philosophical foundations [vide conclusion #1 and #14].

The only, insufficient attempt, to justify such a formulation is found in the first page of the 1905 paper – “Examples of this sort, together with the unsuccessful attempts to discover any motion relatively to the “light medium,” suggest that the phenomena of electrodynamics as well as those of mechanics possess no properties corresponding to the idea of absolute rest. They suggest rather that, as has already been shown to the first order of small quantities, the same laws of electrodynamics and optics will be valid for all frames of reference for which the equations of mechanics hold good.” This is no philosophical justification for such a radical overhaul and its formulation in its various versions[5], and especially the generality in which it is drafted creates difficulties as to its essential nature and character as a law of physics [vide conclusion #14].

Contrary to laws regulating human behaviour, which are usually imposed on society by governments and legislators, the laws of physics are discovered as revealing and exposing the underlying general patterns of nature. In his formulation of the first postulate, devoid of experimental or empirical data, or rational analysis, Einstein seems to be imposing a law on nature rather than exposing a law of nature, without any philosophical justification [vide conclusion #1 and #14].

After “legislating” the first postulate, Einstein next sought to “squeeze” the speed of light, by brute force, within the grand scheme of inertial frames. According to his first postulate, being a law of physics, it had to be invariant in inertial frames. But again, he failed to examine, leaving another gaping philosophical lacuna, if light propagation was compatible with inertial frames, was the uniform speed of the moving frame, by itself, enough for the correspondence of equivalence between inertial frames to arise, or did one have to consider the nature of light, its behaviour in, and interaction with, the moving frame as a container, to determine whether such state of affairs qualified as an inertial frame or not? [vide conclusion #2, #4, and #14].

One could also point out that it was wrong to treat the issue as just a kinematical problem, when in reality it was much more complex – it involved dynamics and quantum mechanics, besides logic and philosophy – the mathematics was just the tip of the iceberg. The quantum nature of light is so elusive that not even the most fundamental issue has been resolved even at the present day, more than a century since then – the wave particle duality debate still rages on after decades of ongoing debate, just like the Michelson-Morley experiment was not to be the end of the debate as to the fabric of space through which light propagates [vide conclusion #14].

8 Einstein’s thought experiments of light rays propagating in moving frames

While both Galileo and Newton employ the metaphor of the sailing ship, Einstein employs a number of thought experiments he conjured over a number of years, some contradicting others. The first one was the light ray moving along a moving rigid rod in The Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies (1905) in his first ever exposition of Special Relativity and the Relativity of Simultaneity.

A rigid rod whose ends are marked A and B, respectively, is at rest w.r.t a “stationary” frame. A light ray is emitted from A to B and then back from B to A along the rigid rod at rest along the x axis to which two identical clocks are attached at A and B being the two ends of the rod, and since Einstein adopts a definition of synchronicity to the effect that for the clocks to be synchronised, the time taken by the light from A to B must be the same it takes for the return journey from B to A, then this results in two synchronous clocks, since that definition is fulfilled. The two events would be simultaneous if emission from A and B took place at the same time as emission from B to A along the rod when not in motion.

A “corresponding” moving frame, allegedly also inertial, is then set up by having the rigid rod and attached clocks proceed along the x axis of the “stationary” frame, in the direction of increasing x and having a light ray emitted from A when the origin of the two frames coincides, reaching B when the rod has advanced on the x axis and having it reflected back to A while the rod is still moving in the same direction of increasing x.

According to Einstein, this results in asynchronous clocks in the moving system since the time taken by the light ray from A to B is longer than that taken from B to A due to the movements of the rod requiring a longer and shorter time and distance, respectively, from A to B and from B to A[6] leading to a speed variation due to receding/approaching speeds. Like the Galilean butterfly above board flying from A to B (being stern and bow) and vice versa, the light ray in this case is not transported by the moving rod, but the two motions are independent of each other, and hence simultaneity should not be expected along the moving rod [vide conclusion #6 and #11].

In its great simplicity this is the thought experiment on which Einstein based his far-reaching conclusions about space and time, leading inter alia to time dilation and length contraction, four vectors, the equivalence of mass and energy, and eventually to the General Theory of Relativity.

Then, some years later in Relativity – the Special and General Theory (1917), Einstein employs yet another different thought experiment to illustrate the Relativity of Simultaneity, where two flashes of lightning hit a railway embankment (stationary frame) simultaneously at A and B situated a large distance apart. A train (moving frame) whose midpoint M’ when at rest coincides with the midpoint M between A and B in the stationary frame of the embankment, which also coincide with A’ and B’ on the train, moves on the railway with constant velocity along the direction of increasing x from the direction of A towards the direction of B.

“If an observer sitting in the position M’ on the train did not possess this velocity, then he would remain permanently at M, and the light rays emitted by the flashes of lightning A and B would reach him simultaneously i.e. they would meet just where he is situated. Now in reality (considered with reference to the railway embankment), he is hastening towards the beam coming from B’ while he is riding on ahead of the beam of light coming from A. Observers who take the railway train as their reference body must therefore come to the conclusion that the lightning flash B took place earlier than the lightning flash at A ….... Events which are simultaneous with reference to the embankment are not simultaneous with respect to the train, and vice versa” - Relativity, the Special and the General Theory, Albert Einstein, 1916 (Relativity of Simultaneity).

The facts are correct but the conclusions are not. While it is a fact that the flash from B will reach observers on the midpoint of the train earlier than the flash from point A, whereas when the train was at rest the two flashes reached the observers simultaneously, the inferences drawn are incorrect. Clearly in this case, the two flashes struck the railway simultaneously, while observers in different frames will detect them non-simultaneously and this could be easily explained by distinguishing between occurrence of an event and its detection. While there is one simultaneous frame, the stationary one, there are as many non-simultaneous frames as there are velocities, an infinite number of non-inertial frames.

More than 30 years after first proposing Special Relativity, in “The Evolution of Physics: the Growth of Ideas from Early Concepts to Relativity and Quanta” (Einstein and Infeld 1938), Einstein came up with yet another thought experiment – that of the light ray moving inside a moving room, where he replicates his moving rod and light ray set-up, but this time employing an enclosed space imagery – a moving room, instead of a moving rod. In spite of the enclosed space set-up, the light ray still refused to be transported along by the moving room and yielded non-simultaneous events and unsynchronised clocks. Moving along the rigid rod, the light ray is clearly not being transported by the moving rod, but it is not even being transported when propagating inside a moving room [vide conclusion #6].

Moreover, in the moving room[7] thought experiment, Einstein swaps the synchronised fames – in the rod example, the clocks were synchronised in the stationary frame while unsynchronised in the moving frame, whereas in the moving room thought experiment, the clocks were synchronised in the moving frame while unsynchronised in the stationary frame, thus swapping simultaneity in the two frames in two different thought experiments, and this adds to the confusion. It could be that he chose the room as the stationary frame and the space in which it moved as the moving frame, in observance of the principle that each frame can claim it is at rest and the other frame is moving even when in reality it is the one moving, but in any case, there could be a contradiction between the two thought experiments.

Instead of the moving rod, room and train, Einstein could have retained Galileo and Newton’s imagery of the sailing ship, since the same reasoning would apply.

9 Interpretation of the thought experiments and the lacunae in the philosophical foundations

In all of these thought experiments there are two emission events and two detection events which occur first in a stationary, then in a moving frame. The butterfly flying from stern to bow and vice versa is now substituted by a light ray, which travels along a rod, inside a room and towards an observer in a train. Einstein’s ultimate goal was to examine how a fixed light speed can be incorporated within Galilean Relativity, and what adjustments needed to be done to formulate a consistent theory.

However, in his zeal to tweak Galilean Relativity to accommodate a constant speed of light in all frames, there is one fundamental question which Einstein failed to address – is electromagnetic radiation transported along by a moving container in such a manner that the motion of the frame is transferred to the radiation itself by “commonality of motion and correspondence of effects” or do they move independent of each other. More fundamentally – can frames of reference involving light be considered as inertial, and is light propagation compatible with inertial frames? Only an affirmative reply to that question would have legitimised the use of inertial frames in the development of Special Relativity, since no commonality of motion means, as we have seen, no inertial frames, and no inertial frames means no Principle of Relativity [vide conclusions #7, #9, and #12].

Nowhere in his seminal 1905 paper establishing Special Relativity, nor in subsequent ones for that matter, is this philosophical question analysed, nor even touched upon, hence the lacuna in the philosophical foundations. In The Evolution of Physics (1938), Einstein himself stated – “Our aim is to indicate the ideas forming the basis of a new physical and philosophical view.” The basis of the philosophical foundations of Special Relativity are conspicuous by their absence, and the supposed philosophical bedrock of Special Relativity is the Relativity of Simultaneity as exposed in #2 of the 1905 paper The Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies (Einstein 1905). However, as one of the best commentaries on the subject, Arthur I Miller, states in “Albert Einstein’s Special Theory of Relativity – Emergence (1905) and Early Interpretation (1905–1911)” – “As far as I know Einstein’s demonstration in #2 of the Relativity of Simultaneity is rarely analysed.” (Miller 1981) [vide conclusion #14].

Not only are Einstein’s philosophical justifications lacking in the paper which ushered Special Relativity, and subsequent ones, but also their analysis by subsequent commentators are few and sparse. A failure of #2 to pass the logical, philosophical, and physical tests could have tragic implications for the whole Theory with domino effect for the General Theory, which is based upon it [vide conclusion #14].

The Special Theory of Relativity is based on inertial frames. Nowhere in the derivation and formulation of Special Relativity did Einstein dispense with the requirement of inertial frames and the Principle of Relativity, and it was always clear that both were intended to be the foundations on which Lorentz transformations were developed and superimposed. Indeed, Arthur I Miller[8] again makes this very clear – “Despite these new elements in his theory, Einstein often emphasised its continuity with Newton’s mechanics. For example we find in the opening section of his paper “Foundations of the General Theory of Relativity” (Einstein 1915), the statement that “the special theory of relativity does not depart from classical mechanics through the postulate of relativity, but through the postulate of the constancy of light.[9]”

From this passage, it is clear he intended a smooth transition from classical to special relativity, a tweak of the old theory, not an overhaul. Tweaking a theory to accommodate new elements is one thing, but overhauling it and divesting it of its essential constituents is another. One could not accommodate light in the Galilean Relativity formalism, the way he intended to do, without destroying its foundations, in such a way that Special Relativity did not have Galilean Relativity as its foundations.

While Einstein’s intention was to retain the Galilean foundations and develop them into a new theory, and not to build a new theory ex novo, by correlating the moving and stationary frames by means of inertia, the concept was so disfigured when light was introduced in the frames of reference, that by the time the conclusions were reached, there was nothing resembling inertial frames anymore, for the behaviour of the frames on which the conclusions were now based resembled more non-inertial frames rather than inertial ones.

This uneasiness with the notion of inertial frames in the derivation of Special Relativity is highlighted by Arthur I Miller[10] – “However, even though Einstein felt that the ‘system of coordinates’ concept as well as of the motion relative to a reference system satisfied the stipulation of meaning, the concept of an inertial system did not, and he considered this to be a ‘logical weakness’ of the theory of special relativity.”

10 More lacunae – the relativity of simultaneity

The common denominator in all of Einstein’s thought experiments was a light ray going in two directions along a body first resting then in uniform motion in one direction. He then correlated a stationary to a moving frame, which he considered to be inertial, in order to pin an equivalence to them, but what he ended up with, as soon as light was introduced in the frames, were not inertial frames any more, and the equivalence which he so badly required, was destroyed in the process. Once inertial frames evaporated, the Galilean Relativity which he required to use as a basis for upgrading to Lorentz transformations evaporated too, there was no philosophical foundations to build upon. In spite of differences, Galilean and Special Relativity allegedly have a common denominator – inertial frames. Simultaneity is important in the development of Special Relativity as a manifestation of equivalence inherent in inertial frames [vide conclusion #11 and #14].

Simultaneity can be defined as the occurrence of two or more events at the same time. In an objective, observer independent world, simultaneity refers to the time at which the events occurred rather than the time at which they were observed but according to Einstein’s definition of synchronisation of clocks and simultaneity, while it is quite simple to determine simultaneity for events that occur at the same place, it gets more complicated for events that are separated by vast distances, especially if those events are observed by observers in motion relative to the events themselves. The thought experiments led him to a re-formulation of classical Simultaneity, which he termed the Relativity of Simultaneity based on the Lorentz transformations.

Now, first of all, one must distinguish between simultaneity of transmission of a light ray and simultaneity (or lack of it) of detection. A non-simultaneous detection of two light rays in a moving frame does not necessarily imply a non-simultaneous transmission and a simultaneous reception does not necessarily imply a simultaneous emission. Transmission and detection of a light ray are two separate events. None of this is dealt with in Special Relativity literature. In general, events occur when they happen and not when they are observed.

Second, in Galilean Relativity, two simultaneous events in the stationary frame are simultaneous in the moving frame, both to an observer moving with the frame and to an observer in the “stationary” frame, and that is what makes inertial frames equivalent and indistinguishable. In all of Einstein’s thought experiments, along the stationary rod, room, or train both detection events are simultaneous; however, when in motion, the two events are non-simultaneous both to an observer moving with the frame and to an observer in the “stationary” frame and thus, there is not even any remote semblance of equivalence [vide conclusion #5 and #11].

If there is no simultaneity in the moving frame, while there was simultaneity in the “corresponding” stationary frame, then the frames are not equivalent and indistinguishable and hence not inertial, and if the frame is not inertial, then the principle of relativity does not apply, and the reverse argument is also valid – if there is no equivalence, then the frames are not inertial and hence, simultaneity should not be expected in the moving frame. If equivalence is the hallmark of inertial frames, and simultaneity is a fundamental manifestation of equivalence, how can a non-simultaneous non-equivalent frame configure within the category and definition of inertial frames? Frames only obtain the special status of “inertial” once they pass the equivalence test. One can call a frame “inertial” as much as one likes but ultimately its behaviour will determine if it is inertial or not [vide conclusion #5, #6, #11, and #12].

If simultaneity in the stationary frame must translate to simultaneity in the moving frame, for the frames to be considered as inertial, but this equivalence does not arise in frames involving light, then how can such frames be considered as inertial? Since the moving rod, room, or train is not transporting the light ray along with them, due to absence of commonality of motion, there is no equivalence between the frames, and just like the butterfly above board the moving ship, one can tell when the rod/room/train/ship is moving and when it is at rest. The speed of light and the speed of the rod w.r.t the “stationary” frame are constant, and the speed of light will not have the speed of the rod added or subtracted to it. Whether it is a butterfly or a light ray, as long as there is no transportation, it will retain the same speed in the “stationary” frame independent of the motion of the moving frame. Hence, a light ray moves at constant speed w.r.t the stationary frame even when emitted along a moving rod, room, or co-ordinate system and this being the real departure from Galilean Relativity yet it does not lead to the weird effects of the Lorentz transformations. In seemingly-inertial frames, a fixed speed will be retained relative to the “stationary” and not the moving system. [vide conclusion #4, #5, #7, #9, #10, and #11].

If the time taken to reach two equidistant detectors is equal and the two events are simultaneous, it means the frame is at rest since the light took the same time to cover equal distances, at the same speed, while if the times are different, and hence the events are non-simultaneous, it necessarily and irrefutably means the frame is moving. While conceding that Galilean transformations function differently from Lorentz transformations yet both require inertial frames for their legitimacy and since the behaviour of light is in conflict with inertial frames, then Lorentz transformations lose their philosophical legitimacy [vide conclusion #14].

In frames involving light, simultaneity does not arise because the moving frame is not inertial, and if the moving frame is not inertial, simultaneity should not be expected, let alone imposed. Simultaneity should be a defining criterion for inertial frames instead of an elastic concept that could be stretched and squeezed to incorporate almost everything, even its perfect opposite, since anything that is not simultaneous is not just different but the perfect opposite of simultaneous. With regards to simultaneity, a miss is as good as a mile [vide conclusion #12 and #13].

The Relativity of Simultaneity, which is the supposed philosophical cornerstone of the Special Relativity edifice, is nothing else but the result of misconstruing non-inertial frames as corresponding, equivalent frames, when in reality there is no equivalence between stationary and moving frames in which light propagates, since they do not fulfil the criteria of inertial frames, as we have seen [vide conclusion #7, #11, and #12].

Indeed, the lack of objective simultaneity in the classical sense should not have been considered as some sort of different kind of simultaneity (relative or otherwise), but an irrefutable indicator of the absence of equivalence of frames, leading to an exclusion of inertial frames and hence an exclusion of relativity.

Two events are either simultaneous or not. Relatively simultaneous is a contradiction in terms. If two events are simultaneous in both frames that might be in itself a solid reason to correlate them. But what is the reason to believe two non-simultaneous events in one frame are correlated with two simultaneous events in another? Such an illogical correlation would need quite a strong philosophical foundation to support it, but there is none. Forcing non-simultaneous events in one frame to become simultaneous in another is a reality breaker. To understand the Relativity of Simultaneity the way Einstein did is to divest objective reality of all its inherent and objective existence. Two events are simultaneous or otherwise independent of the circumstances in which they are observed [vide conclusion #5 and #14].

It is only through the mathematical process of the Lorentz transformations that non-simultaneous events in a moving frame become “relatively” simultaneous. But there is no physical or philosophical justification for this, since events occur when they happen not when they are observed. Furthermore, according to the Lorentz transformations, the more non-simultaneous two events look in the stationary frame, the more simultaneous they look in the moving frame, and vice versa. If the concept of simultaneity can embrace such non-simultaneous events as equivalent and indistinguishable, it loses any meaning at all [vide conclusion #5 and #14].

The Lorentz transformations fix this conundrum by having as many simultaneous events in the “other” frame as there are velocities. In Galilean Relativity there is one set of simultaneous events when the frame is at rest and also when the frame is moving at any speed, but in Special Relativity there are as many sets of simultaneous events as there are velocities that the frame can travel at. There are as many frames in which two events are simultaneous as much as there are velocities. At each velocity, a new set of events will look simultaneous to an observer in the “other” frame. Classical Simultaneity had any meaningful significance at all since two events simultaneous in the stationary frame were also simultaneous in the moving frame, at all speeds.

We are all familiar with the deceiving perception of faraway objects appearing to move slower than closer ones as well as the other illusion of the motion of a train one is sitting in, when in reality it is the other train that is moving. In the Lorentz transformations length contraction, time dilation and simultaneity are also somehow a matter of perception or observation rather than objective reality, so much so that Einstein distinguishes between the geometrical and the kinematical notions of an object.

Length contraction and time dilation are very much observer-dependent since they describe the way events in one frame are observed from another frame, and hence why there is no preferred frame, for each frame can claim that it is at rest and the other frame is moving, and hence its time is dilated and length contracted, even though the frame making that claim would be the one not actually moving. There is danger of self-referential infinite regress, one could argue. The Lorentz factor then is just a number which re-dimensions Galilean Relativity, but like in Galilean Relativity, the Lorentz factor dictates how space and time look to observers in corresponding frames.

But this could only apply if the moving and stationary frames are equivalent. Time in the stationary system (t) and time in the moving system (t′), space (x) in the stationary system and space (x′) in the moving system are connected by the Lorentz factor, which is the conversion factor between two frames as long as they are equivalent. But that equivalence is based on the premise that on each side of the equation sit two inertial frames, otherwise the equivalence is extinguished.

Basically, this is the essence of the Lorentz transformations mechanism – it transforms the metrics of space and time from stationary to moving frames, and vice versa, based on the fundamental premise that the two are corresponding equivalent and indistinguishable inertial frames, which are so equivalent that each is equally justified to hold that it is at rest and the other frame is moving and vice versa. But since it results that in frames involving light, one can easily distinguish a moving frame from a stationary one, then all this collapses. The equivalence is legitimate as long as the frames are inertial, and inertial frames depend on equivalence [vide conclusion #12].

The inertial nature or otherwise of the frame will dictate the way the contents in it will behave, but on the other hand, the behaviour of the contents will determine if a frame is inertial or not [vide conclusion #6].

For simultaneity to have any meaning at all it has to be linked to more stringent requirements, and finally to objective reality. If so many events in so many different frames can qualify as simultaneous and at the same time non-simultaneous in so many other frames, what is the meaning and relevance of simultaneity and how is it connected to the real world? In classical Relativity, simultaneity has meaningful significance because it is equivalent in all frames, and so equivalent that it renders the frames indistinguishable [vide conclusion #5, 14].

Furthermore, the lack of an (unexpected) simultaneity should not have been interpreted as or translated into a lack of synchronicity of clocks. The Principle of Sufficient Reason would dictate that if two events are simultaneous in one frame but non-simultaneous in another, one should examine the nature of the frames as the possible culprit for equivalence breaking before blaming it on the passage of time and the extension of space and turning both upside down.

11 Frames involving light are seemingly-inertial frames [vide conclusion # 4]

Finally, if frames involving light are not inertial, they must be either non-inertial or something in between. After all it was Newton himself who had envisaged quasi-inertial frames, which are neither inertial nor non-inertial – “A striking aspect of Newton’s treatment of indistinguishable frames of reference was his discovery of approximately indistinguishable frames: spaces that are accelerating, yet can be treated, for practical purposes, as if they were at rest or in uniform motion. Newton made this notion precise in Corollary VI to the laws of motion.”[11]

At this point, we can finetune the definition of an inertial frame of reference as an abstract idealised space, which is either stationary or moves at uniform velocity and is such that no distinction can be drawn between the behaviour of the contents when the frame is in motion from the frame at rest, due to the equivalence, which is a consequence of the correspondence between the moving and stationary frames due to commonality of motion [vide conclusion #2].

A non-inertial frame of reference is an abstract idealised space, which due to acceleration or other reasons cannot be considered as corresponding or equivalent to, and indistinguishable from a stationary frame, since from the behaviour of the contents, one can easily distinguish the moving frame from the stationary frame. Non-inertial frames may be of various kinds [vide conclusion #3].

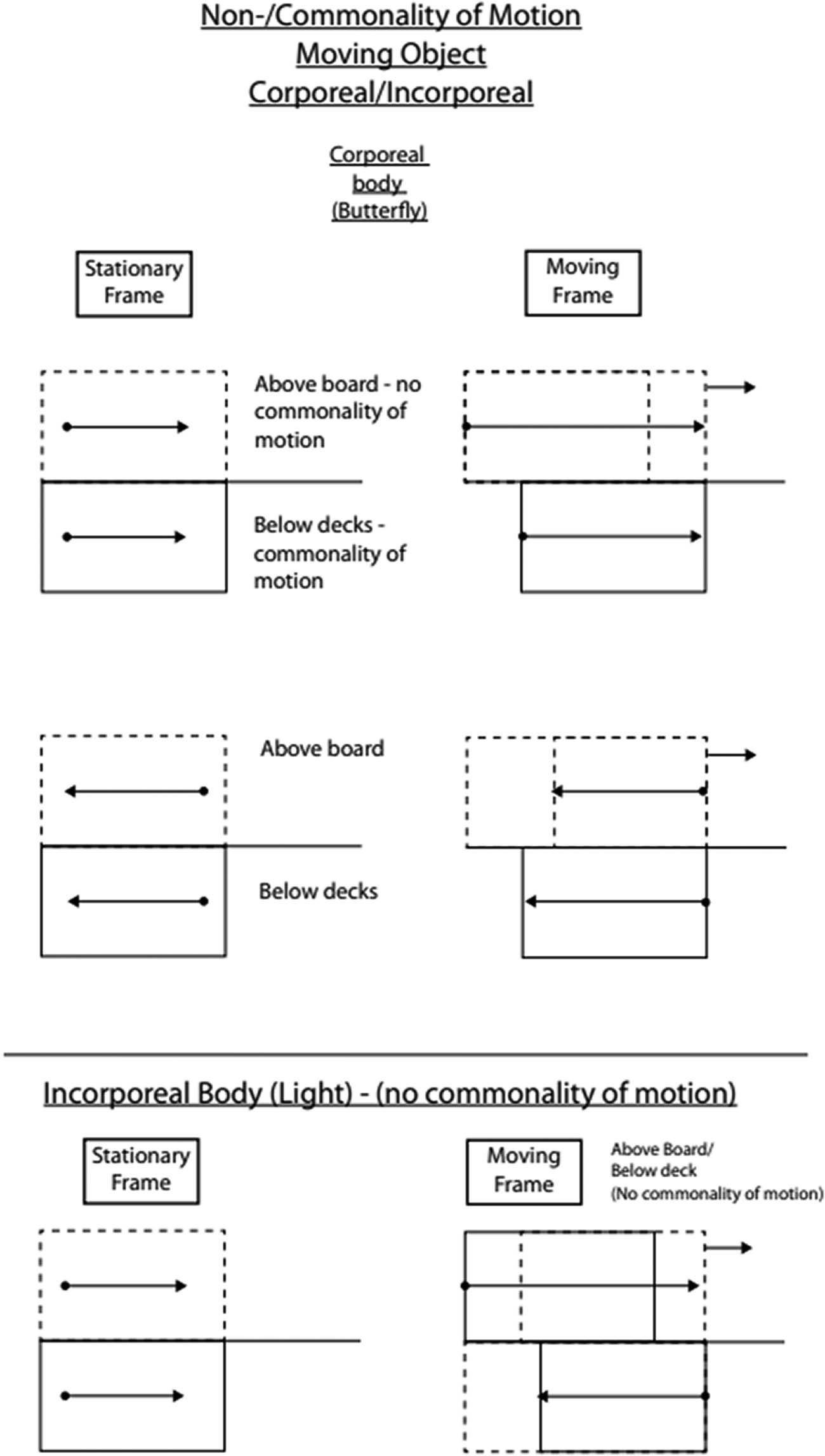

Indeed, light propagation should be excluded from the purview of inertial frames on the same grounds that accelerated frames are excluded, but for different reasons. There is no “commonality of motion and correspondence of effects” between a light ray and the reference frame in which it propagates and such lack of commonality of motion leads to inequivalence between the stationary and moving frames, which in turn excludes the inertial nature of the frames as well as the principle of Relativity both classical and the one drafted by Einstein, since its applicability is limited to inertial frames. A ray of light cannot be transported by a moving frame (Figure 2) [vide conclusion #4, 7, 9].

Corporeal bodies are subject to commonality of motion in an insulated container (below decks) whereas no conmonality of motion ensues in a perforated container (above board) whereas on the other hand incorporeal bodies such as electromagnetic radiation is subject to commonality of motion in neither container. Addition/subtraction of velocities is a consequence of this fundamental distinction.

Once it is established that even to an observer at rest in the moving frame, two events involving light are non-simultaneous, while the two events were simultaneous to the same observer at rest in the same frame when the frame itself was at rest, then the subsequent inferences, including as to how a frame is observed by an observer in a different frame, are irrelevant. Such considerations were only relevant once the two frames were equivalent and indistinguishable to an observer in the frame itself. If the frames are not even equivalent to an observer moving with the frame itself, considerations as to observations from other frames are superfluous [vide conclusion #5, 12].

12 Formulation of the second postulate based on non-transportation of light rays

Indeed in view of these considerations, Einstein’s formulation of the second postulate to the effect that the speed of light is constant in the “stationary” frame independent of the speed of the source emitting it must be construed to mean that while in normal Galilean transformations, the velocity of objects carried along by a moving frame w.r.t a “stationary” frame is made up of two components, the velocity of the container added/subtracted to/from the velocity of the contents; in the case of light, since there is no addition/subtraction of velocities, light retains its speed w.r.t the “stationary” frame, since the speed of the container is not added to it [vide conclusion #2 and #4].

This is the simplest interpretation to the second postulate – the speed of light will be constant w.r.t the stationary frame whether it be propagating in a moving or stationary frame, since unlike Galilean Relativity, the moving frame will not exhibit commonality of motion with the light ray, and hence its speed will not change w.r.t the stationary system [vide conclusion #7 and #9].

In Galilean Relativity, the speed of an object will change w.r.t the stationary system if it travels in a moving frame, but in frames involving light, the speed of light will not change w.r.t stationary system even if emitted in a moving frame. This constitutes the real departure from Galilean Relativity, which, however, does not lead to length contraction and time dilation, and which means that in Galilean Relativity, the addition/subtraction of velocities is the speed of transportation of the body contained by the moving container, leading to an actual change in speed; in frames involving light, since there is no transportation, the variance in speed is just the speed of approach/recession, which results in a change not in the material speed of the body, but of the speed observed. Above board the moving ship, the butterfly’s speed too will be unaltered w.r.t the stationary frame of the shore, as we have seen. [vide conclusion #2 and #10].

No other interpretation seems to be simpler, more legitimate, and plausible even more so when one considers this particular formulation is no oversight, once the same principle is repeated in the same terms and with the same vigour in page 6 of the same 1905 paper – “and applying the principle of the constancy of the velocity of light in the stationary system,” and again page 8 – “….is propagated with the velocity c, if, as we have assumed, this is the case in the stationary system.” The particular choice of words in formulating the most important principle in all of Relativity, in the paper establishing Relativity, is surely not arbitrary and should not go unnoticed or unexamined since it has an important bearing on the precise meaning of the postulate itself. Once again, the “legal” drafting of the two maxims is fundamental [vide conclusion #1 and #8].

In this context, Miller again expresses his concern about the way the second postulate is formulated in 1905, since such a formulation does not lead to or necessitate the Lorentz transformations – “The universality of the second principle is perhaps clouded by Einstein’s use in 1905 of the term “resting” system….” “Resting” system is that which has been referred to as the stationary system, so the reference here is to the “stationary” system. In various instances, Miller expresses concern about important issues in the 1905 paper, yet unfortunately, he gives the impression of being an apologist and indeed, instead of delving deeper where these nebulous concepts crop up, he overlooks them, dismisses them, or ignores them completely. Indeed, even in this case under examination, instead of analysing the true meaning of the particular choice of words in the formulation of the second postulate he just dismisses his declared concern by adding that “yet any inertial system can be the “resting system” [vide conclusion #14].

However, this shallow justification does not hold water since Einstein himself in the same paper made it very clear what he meant by stationary system – “Observers moving with the moving rod would thus find that the two clocks were not synchronous, while observers in the stationary system would declare the clocks to be synchronous.” By contrasting the stationary with the moving system, there is no doubt what Einstein meant by the “stationary” system, and Miller’s defence is very feeble, highly unlikely if not outright unrealistic besides being contradicted by Einstein himself.

It is clear that in formulating the second postulate, Einstein was quite evasive, nebulous, and ambiguous about his real intentions, and what he really had in mind, even in his later formulations. While in The Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies, light moves with the determined velocity c in the “stationary” system, in The Evolution of Physics, “the velocity of light in vacuo is the same in all co-ordinate systems moving uniformly, relative to each other.” In Relativity – the Special and General Theory, he again reiterates “the speed of light in vacuo.” While the “stationary” system does not feature specifically in the second formulation, one could speculate that it has been replaced by the vacuum in which light travels, for is not the expression “speed of light in a vacuum” similar to the expression “the speed of light in the stationary frame”?

Thus, even though in The Evolution of Physics, he omits any reference to the stationary system, yet one could speculate that the word “stationary” is replaced by “in vacuo,” in which case, the essence remains the same in the sense that unlike Galilean Relativity, light is not transported by a moving frame and its speed relative to the stationary system/in vacuo remains constant. It seems that he always formulated the speed of light as constant w.r.t something, either the stationary frame or the vacuum, while at the same time imposing the further requirement that it be constant in all frames [vide conclusion #9].

One could further speculate that if he had in mind to correlate the Lorentz transformations, which had already been known for some time, to a particular description of reality, he was unclear in the drafting of his postulates in order to give himself the freedom to proceed in the pre-planned course for otherwise more clarity would have rendered the Lorentz transformations unnecessary [vide conclusion #14].

Even though later formulations of the second postulate veer away from the emphasis on a fixed speed in the “stationary” frame, in which case, the Lorentz Transformations could be redundant, yet the essence still remained the same. If one adopts this interpretation, that the speed of light is constant w.r.t the stationary frame even if it travels in a moving frame, length contraction and time dilation do not follow from this interpretation and the Lorentz transformations are unjustified [vide conclusion #8].

13 Problem of the speed of light in the moving system

So, if one were to adopt the original formulation of the second postulate in the sense that a light ray retains its constant speed w.r.t the stationary system, it is not essential, for the postulate to be fulfilled, that the light ray is observed to retain its constant speed in the moving system also, since the limits of applicability of the postulate are the constancy of the speed in the stationary system and not also in the moving one, and this as we have seen is the really remarkable departure form of Galilean Relativity [vide conclusion #10].

But even if one were to adopt subsequent formulations of the second postulate, one would realise that it becomes more a question of semantics rather than mathematics, since while Einstein considers two frames moving at constant speed w.r.t each other as tantamount to inertial frames by definition, and since this other formulation specifies that the speed of light is constant in all inertial frames, since as we have seen, frames involving light are just seemingly-inertial and not fully inertial, then the second postulate is a contradiction in terms. Frames involving light are not strictly inertial when in motion, almost inertial but not quite, and thus it is a logical contradiction to state that the speed of light is constant in inertial frames when frames involving light are not inertial. While such an interpretation of the second postulate is of dubious validity, yet it will thus not be violated if the speed of light is not constant in seemingly-inertial frames! [vide conclusion #1 and #12].

But even if one were to interpret the second postulate as requiring a fixed speed of light in the moving frame, one must point out that a light ray propagating across a moving rod, moving room, or moving co-ordinate system is considered as a light ray moving inside a moving frame of reference. Frames of reference were of particular relevance to Galilean Relativity in so far as they can act as containers. Objects simply moving w.r.t each other at various constant speeds were not what Galileo and Newton seem to have mainly had in mind. Galileo could have considered a butterfly flying above board a sailing ship as two objects (butterfly and ship) moving w.r.t each other but he did not, he construed them as a butterfly moving inside a moving frame of reference [vide conclusion #2 and #6].

He constructed an “above boards” non-inertial reference frame and placed the butterfly inside it, and then observed the butterfly’s motion vis-à-vis that particular frame of reference and compared it to an inertial frame of reference – below decks. Similarly, after setting up the stationary system K and the moving system k, which are two frames of reference acting as containers, Einstein envisages a ray of light to be emitted “from the origin of the system k along the X axis.” The co-ordinate frames of reference system K and system X, the moving room inside which light rays move, the moving rod and moving train along or inside which light rays move are all intended as containers, they are not two bodies (light ray and container) moving w.r.t each other but a light ray travelling within a moving frame of reference as container [vide conclusion #2 and #6].

There is a slight but very important distinction in all this. The relationship between container and contents in inertial frames is different from that in non-inertial frames including the sub-category of non-inertial frames here labelled as seemingly-inertial frames, for lack of a better term. In the former, there is commonality of motion and transportation, while in the latter, there is not. In the below decks non-inertial scenario, the ship’s motion materially affects the total speed of the butterfly vis-à-vis the “stationary” frame of the shore. It is not a matter of perception or observation but of actual, physical increase or decrease in speed by means of addition or subtraction, depending on the direction of motion of the ship and that of the butterfly.

The speed of the frame’s contents w.r.t the stationary frame materially change when the container is in motion. With regards to the above board scenario, the ship’s motion, on the other hand, will not materially affect the butterfly’s speed w.r.t the “stationary” frame of the shore and this would give rise only to a difference in the observed relative motion w.r.t the ship. One is an observed change in relative speed, which one might term “fictitious,” while the other is a material change in relative speed.

A fast-moving spacecraft might transport a flying butterfly from Earth to the moon at a faster speed by having its own velocity added to that of the butterfly, but it will not transport faster a light ray, since the light ray will retain its speed independent of whether moving in an empty space or inside the fast-moving spacecraft [vide conclusions #7 and #9].

The butterfly’s speed w.r.t the “stationary” frame of the fixed stars will materially increase when transported by the spacecraft, but the light ray’s speed would not be altered by the spacecraft’s speed and hence, it will remain constant in the “stationary” frame of the fixed stars. According to this interpretation, the conclusion of Special Relativity are unjustified, since the second postulate is satisfied without the need for Lorentz transformations – the speed of light is constant in the stationary frame whether it travels in a moving frame or not.