Teaching Medical Students About Health Systems Science and Osteopathic Principles and Practice Using a Virtual World: The Envision Community Health Center

-

Lise McCoy

Abstract

Medical education technology initiatives can be used to prepare osteopathic medical students for modern primary care practice and to provide students with training to serve vulnerable populations. Over academic years 2014 through 2017, the authors designed and implemented 26 case studies using patient simulations through a virtual community health center (CHC). First-year students, who were preparing for clinical training in CHCs, and second-year students, who were training in CHCs, completed the simulation case studies, gaining practice in clinical reasoning, Health Systems Science, and applied osteopathic principles and practice. This article explains the project, illustrates an alignment with Health Systems Science and osteopathic competencies, and highlights findings from previous research studies.

Modern osteopathic medical training must prepare trainees for practice environments in which medical science, technology, and delivery systems are constantly evolving. The 21st century health care professional must be able to work with interprofessional teams; use health technology and data; communicate effectively; focus on patient-centered, preventive, osteopathic primary care; work with community members and institutions; integrate primary care and public health; and adapt with resilience. Thus, medical education must likewise evolve to meet these needs.

Whereas traditional medical education focuses on basic science and clinical science, Health Systems Science (HSS) education has been promoted by the American Medical Association through the work of the Accelerating Change in Medical Education consortium.1 Described as the third pillar of undergraduate medical education, HSS provides “new physicians a broad view of the societal influences and administrative challenges that sometimes complicate patient care.”1 Although it continues to evolve, the current core domains of HSS include health care structure and process; health care policy, economics, and management; clinical informatics/health information technology; population health; value-based care; and health system improvement.1 Medical trainees who achieve competency in HSS will be able to effectively translate and apply both clinical science and basic science in the ever-evolving complex health care system. These providers will be able to address and make a positive impact on patients’ health at the individual, community, and population level.

Additionally, community-oriented primary care (COPC)2 is a continuous process by which primary health care is provided to a defined community on the basis of its health needs by the planned integration of public health with primary care.3 New osteopathic curricula provide methods to teach students elements of public health and focus on addressing the social determinants of health. Principles of COPC provide a relevant and pragmatic framework that allows health systems to work toward achieving the quadruple aim4 of decreasing workforce burnout, improving population health, increasing patient satisfaction, and reducing per-capita health care spending. To deliver high-quality COPC, providers must apply HSS with regard to navigating health care structure and process, interpreting clinical informatics, tracking population health, optimizing value-based care, and improving health care systems.

At A.T. Still University, School of Osteopathic Medicine in Arizona (ATSU-SOMA), a primary focus is to select, mentor, and train primary care physicians who are committed to working in community health centers (CHCs) and other areas with health care disparities. During their first year, osteopathic medical students form learning teams of 10 to 12 students. At the beginning of the second year, these teams travel to an affiliated CHC, where they spend years 2 through 4 in contextual learning environments that incorporate HSS and important elements of service learning—an “embedded, distributed model.”5,6 Given the need for our students to gain clinical skills and familiarity in practicing in the CHC environments, we developed 26 virtual patient simulation (VPS) case studies set in the Envision CHC, or the Virtual Community Health Center (VCHC). Health Systems Science and COPC were both underlying themes in the development of these cases studies, and this strategy has provided osteopathic medical students, who are embedded in CHCs across the country, deliberate practice with contextualized HSS competencies.

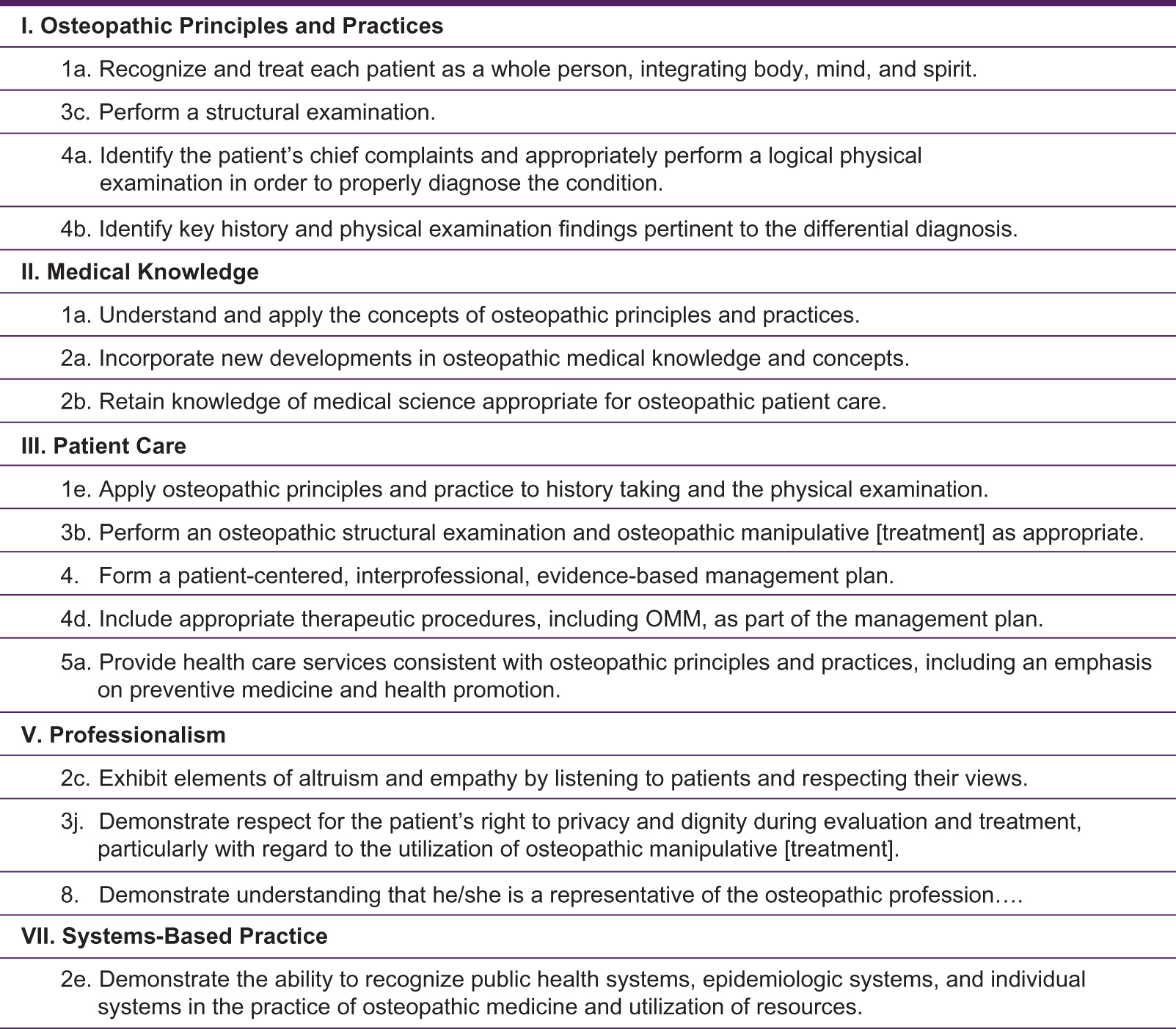

The VCHC project emphasizes the new osteopathic medical education paradigm by moving osteopathic medicine into the forefront of primary care instruction. Case studies in the VCHC align with osteopathic core competencies outlined by the American Association of Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine (Figure 1). Medical students practice osteopathic diagnostic and treatment skills, as well as have osteopathic considerations integrated in a wide variety of clinical cases beginning in the first year.

American Association of Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine competencies addressed by the virtual community health center at A.T. Still University, School of Osteopathic Medicine in Arizona. Abbreviation: OMM, osteopathic manipulative medicine. Source: Osteopathic Core Competencies for Medical Students: Addressing the AOA Seven Core Competencies and the Healthy People Curriculum Task Force's Clinical Prevention and Population Health Curriculum Framework. Chevy Chase, MD: American Association of College of Osteopathic Medicine; 2012.

In this article, we describe the virtual learning environment and implementation of the VCHC. Furthermore, we map VCHC cases to the elements of HSS and osteopathic principles and practice (OPP). We reference earlier evaluation studies to enhance the description and provide examples of ongoing analyses for institutions that may wish to incorporate this or similar programs into their curricula.

The Virtual Learning Environment

Given ATSU-SOMA's emphasis on community health and the need to foster skills associated with HSS and COPC, the aim of the VCHC project was the acculturation of medical students and other health professions trainees toward osteopathic primary care for community clinics.7 The original impetus for developing the VCHC was to develop situated,8 cognitively engaging9 VPS exercises. Before this project, medical student case study practice involved noninteractive, Microsoft PowerPoint–format case studies. Most fictitious patients were anonymous, white, and male. Clinical cases were not situated in community clinics and thus did not reflect social determinants of health in medically underserved populations. Faculty felt osteopathic medical students should practice humanizing care skills, such as learning proper use of patient names, understanding social determinants of health, developing fluency caring for patients from all ethnic backgrounds, and avoiding objectification or bias toward patients.10 In developing a realistic patient panel for the VCHC, the authors reviewed CHC patient demographic statistics.

Virtual patient simulation has emerged as an important medium of medical education, filling gaps within rotations, distance learning, residency, and traditional case practice.11 A growing body of research highlights their utility as safe learning contexts to practice patient care before or as a supplement to actual patient encounters.12,13 Compared with traditional case formats such as PowerPoint, VPS formats offer a variety of educational advantages, fostering clinical decision-making, providing standard feedback, and allowing each student to actively participate.7 The millennial generation of students has been influenced by video games, which often have dramatic story elements and virtual worlds.14 Learners from this generation and the next (Generation Z or post-millennials) bring a sophisticated technology skill set and sense of collaboration, having been brought up with new media and gamification.15 We hoped realistic cases set within a virtual world would make case studies more compelling.14

We implemented the VCHC cases (Table 1) primarily within first- and second-year osteopathic medical school courses during required case practice. In the current flipped lesson format,16 learners access the cases online through the platform DecisionSim approximately once per month before small group case practice. Students then discuss the cases and the various social, economic, and policy implications in class during debrief sessions with their peers and faculty tutors.

The Virtual Community Health Center Cases at A.T. Still University, School of Osteopathic Medicine in Arizona

| Case | Patient | Age, y | Race/Ethnicity | Clinical Presentation | Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Chris Williams | 13 | African American | Limb pain | Torus fracture of distal radius |

| 2 | Shirley Yazzie | 60 | American Indian | Limb pain | Rheumatoid arthritis |

| 3 | Nancy Johnson | 57 | Caucasian | Limb pain | Adhesive capsulitis |

| 4 | Jesús López-Gutiérrez | 47 | Hispanic | Regional back pain | Piriformis syndrome |

| 5 | Ashley McCaskill | 24 | Caucasian | Headache | Migraine without aura |

| 6 | Zelna Washington | 79 | African American | Acute neurologic event | Stroke (occlusive) |

| 7 | Zachary (Zack) Johnson | 16 | Caucasian | Acute neurologic event | Seizure |

| 8 | Lisa Wong-Lucas | 44 | Asian | Dizziness | Dizziness |

| 9 | Barbara Washington | 58 | African American | Hypertension | Hypertension |

| 10 | Lucia Nielsen-López | 3 | Caucasian | Sore throat/rhinorrhea | Sore throat/rhinorrhea |

| 11 | Emiliano Morales-Gómez | 31 | Hispanic | Sore throat/rhinorrhea | Acute epiglottitis |

| 12 | Mariana Gutiérrez-Cruz | 66 | Hispanic | Urinary frequency/red urine | UTI, hemorrhagic cystitis |

| 13 | Ken Johnson | 43 | Caucasian | Red urine | Ureterolithiasis (ureteral stone) |

| 14 | Mariana Gutiérrez-Cruz | 66 | Hispanic | Hyperglycemia | Type 2 diabetes mellitus |

| 15 | Sarah Whitehorse | American Indian | Constipation | Rectocele with vaginal prolapse | |

| 16 | Jesús López-Gutiérrez | 50 | Hispanic | Oral complaints | Oral leukoplakia |

| 17 | Shirley Yazzie | 60 | American Indian | Weight gain | Hypothyroidism |

| 18 | Jonathan Yazzie | 22 | American Indian | Scrotal mass | Testicular seminoma |

| 19 | Nancy Johnson | 59 | Caucasian | Breast disorders | Breast cancer |

| 20 | Peter Morales | 4 | Hispanic | Eye redness | Corneal abrasion |

| 21 | Lisa Wong-Lucas | 46 | Asian | Anemia | Thalassemia |

| 22 | Peter Morales | 4 | Hispanic | ADHD | ADHD |

| 23 | Ian Nielsen | 34 | Caucasian | Anxiety-related symptoms | PTSD |

| 24 | Sheila Washington-Banks | 40 | African American | Skin rash | Psoriasis |

| 25 | Telemetry unit | Various | Various | ACLS rhythms recognition | Multiple |

| 26 | Araceli Gamboa | 14 | Hispanic | Obesity | Obesity |

Abbreviations: ACLS, advanced cardiac life support; ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; UTI, urinary tract infection.

With each case, photographs of standardized patients are used to provide visual points of reference (Figure 2). Students learn to care for patients by managing each part of the patient encounter:

Sample photographs of standardized patients in the Envision Community Health Center, also called the Virtual Community Health Center. Such photographs accompany each virtual case.

■ collecting a detailed patient history, including social determinants of health

■ conducting a physical examination, including an osteopathic structural examination

■ ordering laboratory and imaging tests

■ suggesting a presumptive diagnosis

■ recommending a treatment and follow-up plan

Following a self-directed learning approach,17 osteopathic medical students assume the provider role, evaluate a patient, make meaningful choices, and explore the consequences of these choices. This approach allows for situated cognition, as well as legitimate peripheral participation,8 a process whereby students are initiated into the professional role of physician in a peripheral (safe and risk-free) environment. Student learning is scaffolded via the feedback provided in each case module, and a debrief exercise that follows the case study allows for personal and group reflection.

The VCHC allows first- and second-year osteopathic medical students to experience health care systems linked to communities, as well as interprofessional interactions linked to specific patient encounters.18 For example, students might inventory social determinants of health for a given patient and discuss patient-centered care, the needs of the family, osteopathic manipulative treatment (OMT) considerations, or community health implications. The results from student case debrief sessions have been reported in prior publications.7,18

Earlier Evaluations of the Training Method

The results of this innovation have been published in 2 prior mixed-methods studies.18,19 The evaluation (pilot) phase of the project demonstrated feasibility of the learning model and allowed researchers to work out methods for distributing the cases, tracking learning analytics, and video recording implementation sessions. We measured the value of this learning platform in terms of engagement, clinical reasoning, awareness of COPC, and OPP.

Engagement

In a 2016 study,18 researchers investigated whether the VCHC was cognitively engaging and fostered teamwork and participation. Triangulation of findings between the 4 data sources indicated that VCHC interactive cases were engaging in 3 dimensions: flow, interest, and relevance. In general, students enjoyed the activities and were absorbed in the clinical encounters. The issues with the cases, as expressed by students and tutors, were excessive text, time constraints, requested refinements in terms of alignment of case content to large group lectures, and the desire for students to practice the cases at home.

Clinical Reasoning, COPC, and OPP

The virtual cases provided deliberate practice with clinical reasoning, COPC principles, and osteopathic diagnosis and treatment. In a 2016 study,7 student clinical reasoning and awareness of COPC were measured using pre- and posttest data, case analytics, student responses to case debriefs, and tutor feedback for 8 VCHC cases. For a cohort of 93 first-year students, significant improvement in clinical reasoning was found.7 Student teams of 3 to 4 learners worked through 8 cases, and teams received a mean overall score of 74.7 out of 100 possible points. Individual scores improved between pre- and posttests, with a mean gain of 15.4 points (P<.001).7 Case debriefs allowed students the opportunity to discuss patient care, family-oriented care, and treatment options, including OMT. Tutors reported that students were absorbed in the case studies, an indication of flow and situational cognitive engagement. This finding was corroborated by a separate study that relied on photographic evidence of student affect and participation.18 Several issues surfaced during this referenced study. Due to time constraints within the small group sessions, it was difficult to require multiple-choice assessments for each case that had enough test items and that were aligned to course examinations. The case scoring system needed refinement, and the cases had too many branching pathways.

Fostering Practice With HSS and Osteopathic Competencies

Elements of HSS and COPC were intentionally integrated into each VCHC case module.1 Core domains of HSS include the following: health care structures and process; health care policy, economics, and management; clinical informatics/health information technology; population health; value-based care; and health system improvement. In addition, VCHC case modules address many of the HSS crosscutting domains, such as leadership and change agency, teamwork and interprofessional education, evidence-based medicine and practice, professionalism, ethics, and scholarship.1 Crosscutting domains transcend the core domains and relate to direct patient care competencies. The COPC domains included specific primary care skills: family-centered care; patient-centered care; patient social determinants of health and extended history; diagnostic reasoning and safety; health care team dynamics; warm handoffs; cost-effective treatment and payment options; respectful, humanistic, and compassionate interactions; electronic health records; osteopathic manipulative medicine (OMM) and OMT; evidence-based basic science tutorials; and community-oriented solutions.2

To determine the saturation level of each competency domain for each case, an independent consultant with significant Health Systems Science expertise conducted a post-hoc analysis of the alignment of curricular content of the 26 VCHC cases with core elements of HSS and OPP. This analysis was exempted by the ATSU Institutional Review Board.

First, the HSS expert defined categories, using the Skochelak et al textbook,1 and formatted them into a Microsoft Excel workbook. Second, within the COPC category, a competency subcategory of “OMM and OMT” was introduced. Cases including all osteopathic components (ie, relevant history, osteopathic structural examination, an osteopathic case consultation, and OMT videos) were coded as meeting the OMM and OMT core element. Third, the HSS expert progressed through each VCHC case study in a chronological fashion, from case 1 through case 26. For each case, she listed the case page number and corresponding title of the case page and coded the pertinent HSS core domains and crosscutting domains for the given page. Fourth, for case pages with multiple decision possibilities that could bring about varying results and virtual patient outcomes, she selected each decision point and followed through the consequences of each clinical decision to record all possible corresponding HSS core and crosscutting domains for each decision possibility. The HSS expert repeated this process for every page and for all 26 cases. Finally, the completed crosswalk was reviewed by team members (L.M., J.H.L., T.B., D.M.H., and F.N.S.). This team ensured domain agreement with the categories (and subthemes for each category) listed by Skochelak et al.1

Findings from this analysis are summarized in Table 2, documenting the breadth of HSS and COPC covered by the VPS cases. Results suggest the VCHC cases addressed nearly all of the HSS core domains except “Health Systems Improvement” and “Scholarship.” Thus, through the VCHC training program, trainees practiced a broad array of HHS topics at the level of first- and second-year osteopathic medical students. All of the crosscutting domains (other than scholarship) were integrated. Furthermore, the VCHC provided many opportunities for the risk-free practice of COPC-related skills.

Virtual Community Health Center Cases Aligned to the Core Elements of Health Systems Science and Community-Oriented Primary Care

| Case | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Core Element | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 |

| Health Systems Science Core Domains | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1. Health Care Structures & Processes | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| 2. Health Care Policy, Economics, & Management | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| 3. Clinical Informatics/Health Information Technology | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| 4. Population Health | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| 5. Value-Based Care | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| 6. Health Systems Improvement | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Health Systems Science Cross-Cutting Domains | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1. Leadership & Change Agency | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2. Teamwork & Interprofessional Education | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| 3. Evidence-Based Medicine & Practice | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| 4. Professionalism & Ethics | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| 5. Scholarship | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Health Systems Science Linking Domain | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Systems Thinking | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Community-Oriented Primary Care Skills | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1. Family-Centered Care | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| 2. Patient-Centered Care | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| 3. Patient SDH & Extended History | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| 4. Diagnostic Reasoning, Avoiding Medical Errors, & Patient Safety | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| 5. Health Care Team Dynamics, Warm Handoffs | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| 6. Cost-effective Treatment & Payment Options for Patients | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| 7. Respectful, Humanistic, & Compassionate Interactions | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| 8. Electronic Health Record | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| 9. OMM & OMT (unique to osteopathic medicine) | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| 10. Evidence-Based Basic Science Tutorials & Articles | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| 11. Community-Oriented Solutions (Population Health) | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

Abbreviations: OMM, osteopathic manipulative medicine; OMT, osteopathic manipulative treatment; SDH, social determinants of health.

In terms of alignment with OMM and OMT, as reported in Table 2 under the subcategory “Community-Oriented Primary Care,” 25 of the 26 VCHC case studies integrated osteopathic considerations, including relevant history, osteopathic structural examination, an osteopathic case consultation, and OMT videos.

Discussion

The innovation we describe in the present report reflects our efforts from 2014 through 2017 to develop a new training platform suitable for first- and second-year osteopathic medical students. The journey of developing the library of 26 virtual cases has been time consuming but enriching. In the current phase of the project, it appears that the VCHC cases provide deliberate practice with HSS and OPP competencies. The HSS domains of scholarship and health systems improvement were not addressed; these facets of HSS were not easy to integrate into VPS.

The VCHC was developed for students bound for community health care environments. While elements and formats of this library of virtual cases may be of interest to other osteopathic medical schools, some features, such as the clinical presentation model for deliberate practice with clinical reasoning, might not translate to other training contexts. Although faculty members have addressed issues that surfaced in earlier evaluation studies (excessive text, short multiple-choice quizzes, individual case practice at home before small group), there are new challenges this year, including the following:

■ expense of student licenses to allow cross-training of interprofessional teams of students from different colleges, such as nursing

■ faculty time to write interprofessional cases, which require a team approach

■ minor technology glitches, such as the end user (student) having to clear his or her cache

■ faculty time for creating test questions for each case aligned to end-of-course examinations

■ staff required to compile results of debriefs for the clinical faculty to review as formative assessment

■ upgrading the system so that case scores appear in the learning management system and students can see their own scores

■ further infusing collaborative practice and multiple provider conversations into the case format

Integrating these activities within the existing small group case curriculum required several years of building trust and strong communication with the team of small-group tutors. Continuous training of the small-group tutors facilitated the uptake and standardization of this new instructional intervention.

To our knowledge, the VCHC cases are among the first virtual patient simulations to integrate the full spectrum of osteopathic considerations, including osteopathic structural examinations and OMT. Future directions include developing more cases for interprofessional education, resident training, continuing medical education, public health, and competency-based education in distance-training environments.

Conclusion

In response to medical practice transformation, medical schools are striving to introduce HSS curricula and service learning experiences. In designing this medical education innovation, we sought to design engaging case studies integrating HSS competencies in a virtual world. An analysis of competencies and case content indicates that VCHC cases successfully integrated most HSS competencies and OPP into clinical cases. Although the project has been time consuming and challenging, it has been highly rewarding in terms of achieving an engaging method for providing practice with HSS and OPP competencies for osteopathic medical students.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Earla White, PhD, MEd, RHIA, for her analysis of the alignment of curricular content of the 26 VCHC cases with core elements of HSS and OPP.

Author Contributions

Drs McCoy, Lewis, Heath, and Schwartz provided substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; all authors drafted the article or revised it critically for important intellectual content; all authors gave final approval of the version of the article to be published; and all authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

References

1. Skochelak SE , HawkinsR, LawsonL, StarrS, BorkanJ, GonzaloJ. Health Systems Science. Philadelphia PA: AMA Educational Consortium; 2017.Search in Google Scholar

2. Geiger HJ . Community-oriented primary care: a path to community development. Am J Public Health.2002;92(11):1713-1716.10.2105/AJPH.92.11.1713Search in Google Scholar

3. Mullen F , EpsteinL. Community-oriented primary care: new relevance in a changing world. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(11):1748-1755.10.2105/AJPH.92.11.1748Search in Google Scholar

4. Bodenheimer T , SinskyC. From triple to quadruple aim: care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med.2014;12(6):573-576.10.1370/afm.1713Search in Google Scholar

5. Schwartz FN , HoverML, KinneyM, McCoyL. Student assessment of an innovative approach to medical education. Med Sci Educ.2012;22(3):102-107.10.1007/BF03341769Search in Google Scholar

6. Stewart T , WubbenaZC. A systematic review of service-learning in medical education: 1998-2012.Teach Learn Med.2015;27(2):115-122.10.1080/10401334.2015.1011647Search in Google Scholar

7. McCoy L , LewisJH, BennettT, AllgoodJA, BayC, SchwartzFN. Fostering service orientation in medical students through a virtual community health center. J Fam Med Community Health.2016;3(2):1-8.Search in Google Scholar

8. Lave J , WengerE. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation.Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press;1991.10.1017/CBO9780511815355Search in Google Scholar

9. Barab SA , HayKE. Doing science at the elbows of experts: issues related to the science apprenticeship camp. J Res Sci Teach.2001;38(1):70-102.10.1002/1098-2736(200101)38:1<70::AID-TEA5>3.0.CO;2-LSearch in Google Scholar

10. Schulman KA , BerlinJA, HarlessW, et al. The effect of race and sex on physicians' recommendations for cardiac catheterization. N Engl J Med.1999;340(8):618-626.10.1056/NEJM199902253400806Search in Google Scholar

11. Bateman J , AllenME, KiddJ, ParsonsN, DaviesD. Virtual patients design and its effect on clinical reasoning and student experience: a protocol for a randomised factorial multi-centre study. BMC Med Educ.2012;12:62. doi:10.1186/1472-6920-12-62Search in Google Scholar

12. Ziv A , SmallSD, WolpePR. Patient safety and simulation-based medical education. Med Teach.2000;22(5):489-495.10.1080/01421590050110777Search in Google Scholar

13. Botezatu M , HultH, ForsUG. Virtual patient simulation: what do students make of it? a focus group study. BMC Med Educ.2010;10(91):1-8.10.1186/1472-6920-10-91Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

14. Conradi E , KaviaS, BurdenD, et al. Virtual patients in a virtual world: training paramedic students for practice. Med Teach.2009;31(8):713-720.10.1080/01421590903134160Search in Google Scholar PubMed

15. Dede C . Planning for neomillenial learning styles.Educause Quarterly. January 2005:7-12.Search in Google Scholar

16. Pettit RK , McCoyL, KinneyM. What millennial medical students say about flipped learning. Adv Med Educ Pract.2017;8:487-497. doi:10.2147/AMEP.S139569Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

17. de Bilde J , VansteenkisteM, LensW. Understanding the association between future time perspective andself-regulated learning through the lens of self-determination theory. Learning Instruct.2011;21(3):332-344.10.1016/j.learninstruc.2010.03.002Search in Google Scholar

18. McCoy L , PettitRK, LewisJH, AllgoodJA, BayC, SchwartzFN. Evaluating medical student engagement during virtual patient simulations: a sequential, mixed methods study.BMC Med Educ.2016;16:20.10.1186/s12909-016-0530-7Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

19. McCoy L , LewisJH, BennettT, AllgoodJA, BayC, SchwartzFN. Fostering service orientation in medical students through a virtual community health center. J Fam Med Community Health.2016;3(2):1-8.Search in Google Scholar

© 2018 American Osteopathic Association

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- SURF

- Sleep and Lifestyle Habits of Osteopathic Emergency Medicine Residents During Training

- Addressing the Increased Incidence of Common Sexually Transmitted Infections

- ABSTRACTS

- Educating Leaders 2018: Abstracts From AACOM's Annual Conference

- OMT MINUTE

- Doming the Diaphragm in a Patient With Multiple Sclerosis

- EDITORIAL

- Resident Duty Hour Restrictions: The Implications Behind the New Data Ahead of the Single Accreditation System

- A Perspective on the Sleep and Lifestyle Habits of Emergency Medicine Residents

- LETTERS TO THE EDITOR

- Toxic Injury to the Gastointestinal Tract After Ipilimumab Therapy

- ORIGINAL CONTRIBUTION

- Using a Multitheory Model to Predict Initiation and Sustenance of Fruit and Vegetable Consumption Among College Students

- Predictors of Responsible Drinking or Abstinence Among College Students Who Binge Drink: A Multitheory Model Approach

- BRIEF REPORT

- Osteopathic Manipulative Therapy and Multiple Sclerosis: A Proof-of-Concept Study

- Diabetes Fellowship in Primary Care: A Survey of Graduates

- JAOA/AACOM MEDICAL EDUCATION

- Teaching Medical Students About Health Systems Science and Osteopathic Principles and Practice Using a Virtual World: The Envision Community Health Center

- CASE REPORT

- Hemiplegic Syndrome After Chopstick Penetration Injury in the Lateral Soft Palate of a Young Child

- CLINICAL IMAGES

- Orbital Fat Prolapse

- Unusual Cause of “Constipation”

Articles in the same Issue

- SURF

- Sleep and Lifestyle Habits of Osteopathic Emergency Medicine Residents During Training

- Addressing the Increased Incidence of Common Sexually Transmitted Infections

- ABSTRACTS

- Educating Leaders 2018: Abstracts From AACOM's Annual Conference

- OMT MINUTE

- Doming the Diaphragm in a Patient With Multiple Sclerosis

- EDITORIAL

- Resident Duty Hour Restrictions: The Implications Behind the New Data Ahead of the Single Accreditation System

- A Perspective on the Sleep and Lifestyle Habits of Emergency Medicine Residents

- LETTERS TO THE EDITOR

- Toxic Injury to the Gastointestinal Tract After Ipilimumab Therapy

- ORIGINAL CONTRIBUTION

- Using a Multitheory Model to Predict Initiation and Sustenance of Fruit and Vegetable Consumption Among College Students

- Predictors of Responsible Drinking or Abstinence Among College Students Who Binge Drink: A Multitheory Model Approach

- BRIEF REPORT

- Osteopathic Manipulative Therapy and Multiple Sclerosis: A Proof-of-Concept Study

- Diabetes Fellowship in Primary Care: A Survey of Graduates

- JAOA/AACOM MEDICAL EDUCATION

- Teaching Medical Students About Health Systems Science and Osteopathic Principles and Practice Using a Virtual World: The Envision Community Health Center

- CASE REPORT

- Hemiplegic Syndrome After Chopstick Penetration Injury in the Lateral Soft Palate of a Young Child

- CLINICAL IMAGES

- Orbital Fat Prolapse

- Unusual Cause of “Constipation”