To The Editor

Gas-forming pyogenic liver abscess (GFPLA), accounting for 1%–5% of pyogenic liver abscess,[1] is usually associated with diabetes and abnormality of blood glucose level. Klebsiella pneumoniae, usually detected from blood culture and liver puncture, is the most frequent bacterium for GFPLA, with a tendency to metastatic infection and shock. Between 27.7% and 37.1% of patients could die due to this.[2–3] Therefore, immediate and effective treatment is of vital importance. In case of metastatic intracranial infection caused by GFPLA, meningitis and brain abscess are the most frequent, while metastatic gas embolization and pneuomocrania are rare. Here, we present a rare case in which the patient died from cerebral gas embolization due to K. pneumoniae-induced GFPLA.

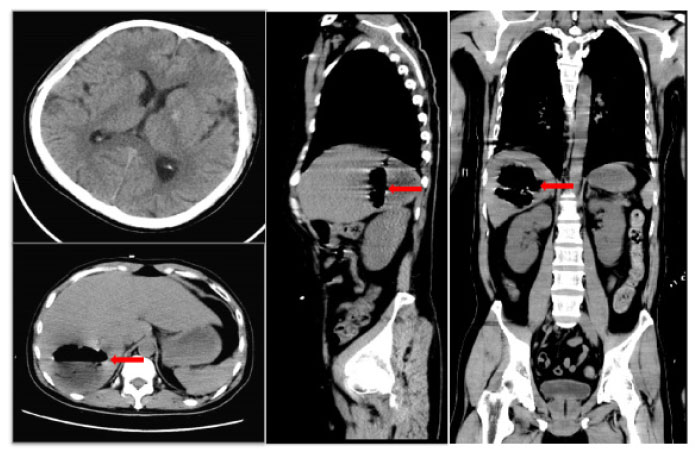

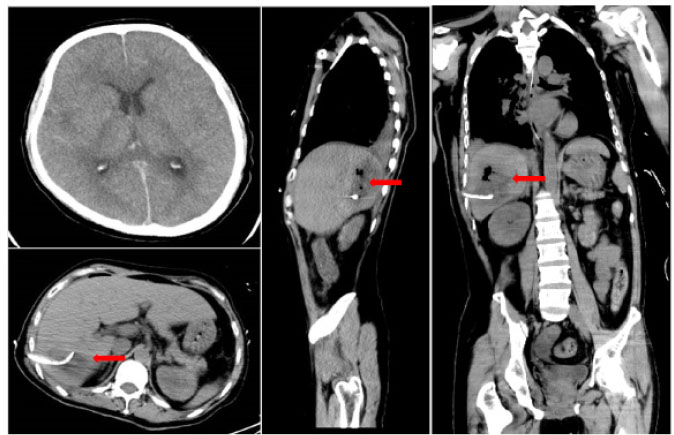

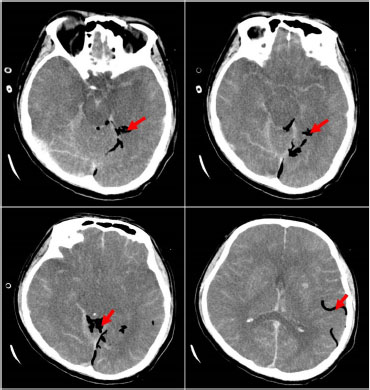

A 41-year-old male was admitted to the intensive care unit with sustained chills and fevers for 1 week and coma for 5 h. Leukocyte, neutrophil, C-reactive protein, and procalcitonin levels were high and platelet level was low. There was a significant increase in glycosylated hemoglobin, indicating undiagnosed diabetes mellitus or poor glucose control. Computed tomography (CT) revealed liver abscess with a large fluid–gas plane, but indicated no brain abnormalities (Figure 1). A diagnosis of GFPLA was made; percutaneous abscess drainage combined with anti-infective therapy was carried out, but the patient’s condition deteriorated, and bilateral pupil dilatation occurred on the next day. Immediate CT review showed brain edema and subarachnoid hemorrhage despite decrease in hepatic fluid and gas levels (Figure 2). A culture of abscess fluid and blood, along with next-generation sequencing yielded a definitive diagnosis of K. pneumoniae infection (Figures 3). Anaerobic and fungal cultures were negative. Anti-infective therapy based on drug-sensitive experiments was administered (imipenem cilastatin 2 g, every 6 hours), but the treatment was not effective and the patient eventually died of progressive cerebral swelling, herniation, and pneuomocrania (Figure 4).

GFPLA is the extreme condition of pyogenic liver abscess accounting for 1%– 5% of all liver abscesses, and is associated with higher morbidity and mortality than non–gas-forming pyogenic liver abscess.[1] The majority of GFPLA cases are infected by K. pneumoniae with a high incidence of extrahepatic complications involving eye, muscle, fascia, and the central nervous system.[4–5] Patients with extrahepatic metastatic infection have a relatively worse condition and are more often admitted to intensive care unit (ICU). Nevertheless, almost 20% of patients will die eventually.[2]

Initial brain CT scan shows no abnormalities, while sagittal and axial abdominal CT scans reveal a hepatic abscess with high gas and fluid levels in the right lobe. Red arrow: a large amount of gas is seen in the cavity of the liver abscess. CT: computed tomography.

Repeat CT scans on day 2 reveal emerging cerebral edema and subarachnoid hemorrhage, but there is a decrease in hepatic gas and fluid levels. Red arrowhead: after liver abscess puncture drainage, the gas in the abscess cavity had decreased obviously. CT: computed tomography.

In this case, the patient developed a metastatic intracranial infection and pneumocephalus, which led to severe brain edema and hernia. This is rare, but a life-threatening complication and is worth being concerned about.

GFPLA is mainly diagnosed via ultrasound (US) or a computerized tomography (CT) scan. Lee et al.[3] reported 100% detection rate through either US or CT. Relevant studies have shown that monomicrobial K. pneumoniae was the most common bacterium found in patients with GFPLA.[3,6] K. pneumoniae was found in 85.9% (80.6%–100%) of positive liver pus cultures in GFPLA patients versus 67.7% (65.8%–85.7%) in non-GFPLA patients. In this case, the pus cavity and blood culture of the patient were confirmed to be K. pneumoniae, but the cerebrospinal fluid culture could not be performed due to the existence of cerebral hernia. Therefore, the intracranial metastasis of K. pneumoniae could not be directly confirmed. However, recent studies have indicated that K. pneumoniae-induced GFPLA is significantly associated with metabolic disorders including hypertension, diabetes, and fatty liver. Poorly controlled diabetes is probably an independent risk factor for extrahepatic complications.[7] Glucose fermentation by bacteria causes the accumulation of formic acid, which is metabolized by formic hydrogenlyase. Gas is produced and accumulated in the process, and large amount of gas accumulation will inevitably lead to the continuous increase of pressure in the abscess cavity, which will subsequently cause difficulty of drug entry and the high risk of bacterial blood entry.[3] In spite of the absence of history of diabetes in this case, a significantly increased glycosylated hemoglobin and glycosylated albumin suggested undiagnosed diabetes, and poor glucose control may be the main risk factor for dissemination. Therefore, the patient in this case had a high risk of distant spread of infection, and new intracranial pneumatosis could be seen on the head CT, reexamined on the fifth day after admission. It is not ruled out that pathogenic bacteria and gas enter the blood due to high pressure in the pus cavity. While considering the impact of intracranial infection caused by K. pneumoniae, we should also pay attention to the impact of air embolism on the blood supply of brain tissue, which is bound to cause ischemia, hypoxia, and the swelling of brain tissue. In terms of treatment, in addition to antibiotic and abscess drainage, for the GFPLA patients, attention must be paid on strict glycemic monitoring and control in order to prevent metastatic infection. Furthermore, GFPLA patients could have impaired consciousness due to toxic infectious materials, which must be differentiated from metastatic intracranial infection through immediate image scanning to avoid a delay in treatment.

Culture of blood and abscess fluid demonstrating Klebsiella pneumoniae infection

CT scan on day 5 showing exacerbated brain swelling, cerebral herniation, and emerging pneumocrania. Red arrow: visible intracranial pneumatosis. CT: computed tomography.

Funding statement: The study was supported by the High-level Hospital Construction Research Project of Maoming People’s Hospital.

-

Author Contributions

WSC, MXF: Conceptualization, Writing—Original draft preparation, Writing—Reviewing and Editing. MXF: Writing—Manuscript improvement. CBC: Supervision, Project administration.

-

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this manuscript and any accompanying images. The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

-

Conflict of Interest

Chunbo Chen is an Associate Editor-in-Chief of the journal. The article was subject to the journal’s standard procedures, with peer review handled independently of the editor and the affiliated research groups.

References

1 Zhang Y, Zang GQ, Tang ZH, Yu YS. Fatal gas-forming pyogenic liver abscess due to Klebsiella pneumoniae. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo 2013;55:144.10.1590/S0036-46652013000200017Search in Google Scholar PubMed

2 Thng CB, Tan YP, Shelat VG. Gas-forming pyogenic liver abscess: A world review. Ann Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 2018;22:11–8.10.14701/ahbps.2018.22.1.11Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

3 Lee HL, Lee HC, Guo HR, Ko WC, Chen KW. Clinical significance and mechanism of gas formation of pyogenic liver abscess due to Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Clin Microbiol 2004;42:2783–5.10.1128/JCM.42.6.2783-2785.2004Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

4 Wang WJ, Tao Z, Wu HL. Etiology and clinical manifestations of bacterial liver abscess: A study of 102 cases. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018;97:e12326.10.1097/MD.0000000000012326Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

5 Chen Y. Clinical Challenges with Hypervirulent Klebsiella Pneumoniae (hvKP) in China. J Transl Int Med 2021;9:71–5.10.2478/jtim-2021-0004Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

6 Wang J, Yan Y, Xue X, Wang K, Shen D. Comparison of pyogenic liver abscesses caused by hypermucoviscous Klebsiella pneumoniae and non-Klebsiella pneumoniae pathogens in Beijing: a retrospective analysis. J Int Med Res 2013;41:1088–97.10.1177/0300060513487645Search in Google Scholar PubMed

7 Yoon JH, Kim YJ. Liver abscess due to Klebsiella pneumoniae: risk factors for metastatic infection. Scand J Infect Dis 2014;46:21–6.10.3109/00365548.2013.851414Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2023 Weisheng Chen, Miaoxian Fang, Chunbo Chen, published by De Gruyter on behalf of the SMP

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Perspective

- A cycloruthenated complex, ruthenium (II) Z (RuZ) overcomes in vitro and in vivo multidrug resistance in cancer cells: A pivotal breakthrough

- Protocols for Traditional Chinese Medicine guidelines for acute primary headache

- Timing of anticoagulation for the management of portal vein thrombosis in liver cirrhosis

- Roles of noncoding RNAs in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- Suggestions on home quarantine and recovery of novel coronavirus patients

- Review Article

- Therapeutic potential and mechanisms of sacral nerve stimulation for gastrointestinal diseases

- The evolution of folate supplementation – from one size for all to personalized, precision, poly-paths

- Original Article

- A generalized deep learning model for heart failure diagnosis using dynamic and static ultrasound

- A new ferroptosis-related signature model including messenger RNAs and long non-coding RNAs predicts the prognosis of gastric cancer patients

- A newly-synthesized compound CP-07 alleviates microglia-mediated neuroinflammation and ischemic brain injury via inhibiting STAT3 phosphorylation

- Adrenomedullin induces cisplatin chemoresistance in ovarian cancer through reprogramming of glucose metabolism

- Serum myoglobin modulates kidney injury via inducing ferroptosis after exertional heatstroke

- Letter to Editor

- Gas embolism caused by gas-forming pyogenic liver abscess

Articles in the same Issue

- Perspective

- A cycloruthenated complex, ruthenium (II) Z (RuZ) overcomes in vitro and in vivo multidrug resistance in cancer cells: A pivotal breakthrough

- Protocols for Traditional Chinese Medicine guidelines for acute primary headache

- Timing of anticoagulation for the management of portal vein thrombosis in liver cirrhosis

- Roles of noncoding RNAs in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- Suggestions on home quarantine and recovery of novel coronavirus patients

- Review Article

- Therapeutic potential and mechanisms of sacral nerve stimulation for gastrointestinal diseases

- The evolution of folate supplementation – from one size for all to personalized, precision, poly-paths

- Original Article

- A generalized deep learning model for heart failure diagnosis using dynamic and static ultrasound

- A new ferroptosis-related signature model including messenger RNAs and long non-coding RNAs predicts the prognosis of gastric cancer patients

- A newly-synthesized compound CP-07 alleviates microglia-mediated neuroinflammation and ischemic brain injury via inhibiting STAT3 phosphorylation

- Adrenomedullin induces cisplatin chemoresistance in ovarian cancer through reprogramming of glucose metabolism

- Serum myoglobin modulates kidney injury via inducing ferroptosis after exertional heatstroke

- Letter to Editor

- Gas embolism caused by gas-forming pyogenic liver abscess