Challenges and improvement in management of neonates born to mothers with COVID-19 in China

-

Jie Yang

, Zhichun Feng

and on behalf of the Chinese Neonatologist Association

Abstract

Objective

China was the first country suffering from the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic and one of the countries with stringent mother-neonate isolation measure implemented. Now increasing evidence suggests that coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) should not be taken as an indication for formula feeding or isolation of the infant from the mother.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study in 44 hospitals from 14 provinces in China to investigate the management of neonates whose mothers have confirmed or suspected COVID-19. In addition, 65 members of Chinese Neonatologist Association (CNA) were invited to give their comments and suggestions on the clinical management guidelines for high-risk neonates.

Results

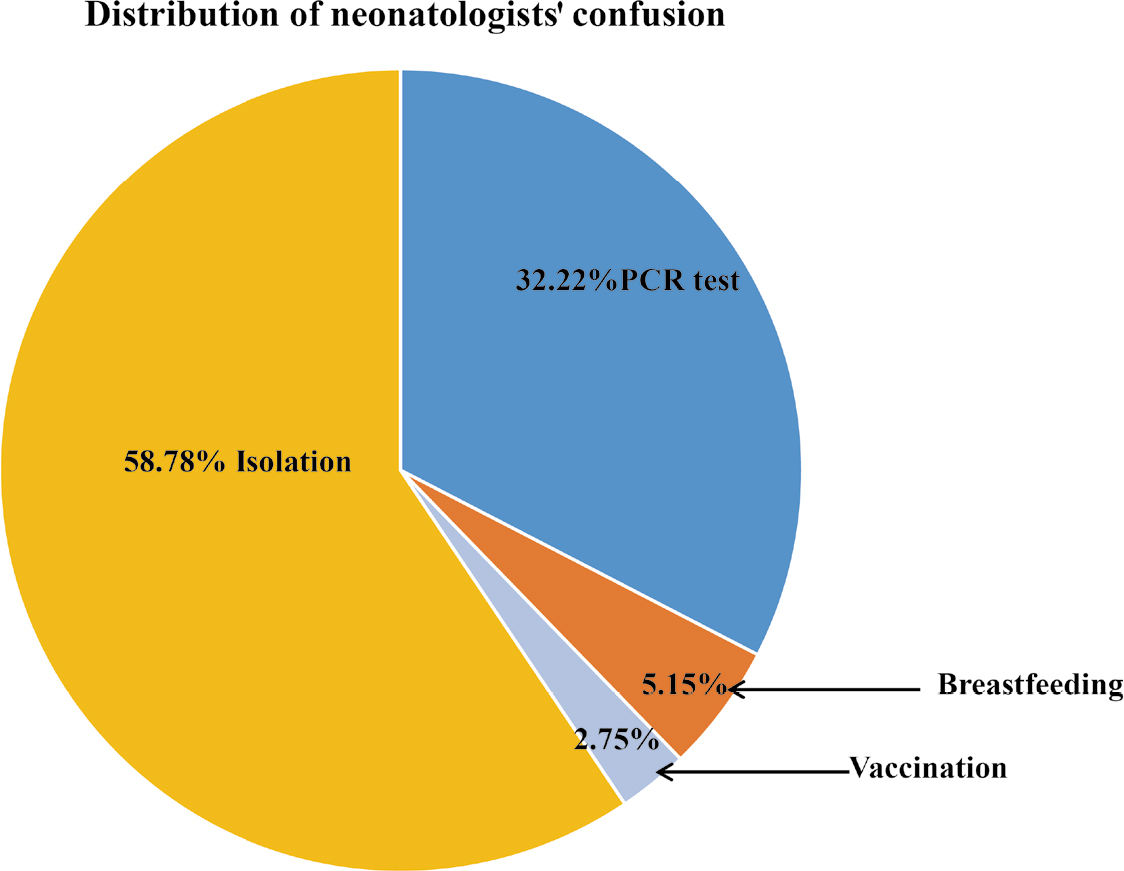

There were 121 neonates born to 118 mothers suspected with COVID-19 including 42 mothers with SARS-CoV-2 positive results and 76 mothers with SARS-CoV-2 negative results. All neonates were born by caesarean section, isolated from their mothers immediately after birth and were formula-fed. Five neonates were positive for SARS-CoV-2 at initial testing between 36 and 46 h after birth. Regarding the confusion on the clinical management guidelines, 58.78% of the newborns were put into isolation, 32.22% were subject to PCR tests, and 5.16% and 2.75% received breastfeeding and vaccination, respectively.

Conclusion

The clinical symptoms of neonates born to mothers with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 were mild, though five neonates might have been infected in utero or during delivery. Given the favorable outcomes of neonates born to COVID-confirmed mothers, full isolation may not be warranted. Rather, separation of the mother and her newborn should be assessed on a case-by-case basis, considering local facilities and risk factors for adverse outcomes, such as prematurity and fetal distress.

1 Background

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a global pandemic with 217 558 771 confirmed cases, including 4 517 240 deaths, as of September 1, 2021[1]. China was the first country to suffer from the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic with more than 90 000 cases[2]. At the beginning of this pandemic, the management regarding care of neonates whose mothers have confirmed or suspected COVID-19 was not uniform. The Chinese Neonatologist Association, Chinese Maternal Child Health Association issued the consensus on the management of SARS-CoV-2 infection in neonates[3,4,5]. The consensus recommended that the neonates born to mothers confirmed or suspected with COVID-19 should be placed in a single room, isolated from healthy neonates and mothers with a minimum of 14 days and suspended breastfeeding. However, there were very few relevant data and supporting evidence on COVID-19 and neonates isolation at the time when the consensus was made.

There were series of observational studies reported from Chinese clinicians, focusing on the perinatal clinical characteristics of COVID-19. However, the measures that may impose long-term impact on neonatal psychological development, such as isolation and breastfeeding strategy under this consensus, have been less documented[6,7,8,9,10]. Salvatore and colleagues performed a cohort study in the United State, they found that perinatal SARS-CoV-2 transmission is unlikely and allowing newborns to room-in and breastfed were safe with the appropriate precautions[11]. Recently, a systematic review analyzed the risk of neonatal infection by breastfeeding and mother–infant interaction. This review suggested that COVID-19 should not be an indication for formula feeding or isolation of the infant from the mother[12]. These newly emerging evidence prompted us to ponder that prolonged isolation may not only waste medical recourse but also have long term negative effects in neonatal psychological development.

The Chinese Neonatologist Association held a cohort study to investigate the management of neonates whose mothers have confirmed or suspected COVID-19. In addition, the members of CNA were invited to comment on the clinical management guidelines on high-risk neonates and provide suggestion for further improvement.

2 Methods

2.1 Study population

A retrospective cohort study was conducted in 44 hospitals from 14 provinces in China through the Chinese Neonatal Association. The hospitals were selected because they were designated as referral centers for neonates born to mothers with confirmed or presumed COVID-19, of which ten are level II hospitals with 100–500 beds and 34 level III hospitals with more than 500 beds. Most of these hospitals (N = 38) had their own equipment and technical strength to conduct SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing, and the remaining 6 hospitals sent samples to the local China Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for PCR testing.

The pregnant women were tested for COVID-19 only if being clinically or epidemiologically suspected of COVID-19 following the national guideline when the study was carried out. Clinical signs suggestive of COVID-19 were any two of the following: fever and/or respiratory symptoms, radiographic imaging consistent with COVID-19 pneumonia, and decreased white blood cell counts or decreased lymphocyte count in the early stages of illness[13]. Potential epidemiological exposure to COVID-19 included residence in or travel to Wuhan and other areas in China where cases had been reported, contact with an individual who had tested positive for COVID-19, contact with patients with fever or respiratory symptoms from areas where cases had been reported; or clusters of two or more cases with fever and/or respiratory symptoms such as in families, offices and schools[13].

When a mother was suspected of COVID-19, obstetricians were advised to inform neonatologists 30 minutes before delivery so that a neonatologist could be present at the delivery and prepare appropriate care for the newborn. All neonates born to suspected mothers were admitted to designated hospitals where isolation rooms with standard protection precautions were available. There were three types of isolation units: primary care units for neonates without symptoms, special care units for high-risk neonates or those needing short term assisted ventilation without any organ failure, and intensive care units for newborns with severe symptoms and/or requiring assisted ventilation. If the mother's SARS-CoV-2 test result was unavailable at the time of delivery, either because the prenatal test results has not yet been reported or because the mother was only tested postnatally, the neonate was moved to the intensive care isolation unit. Neonates were isolated immediately after birth for at least 14 days, following guidance from the Chinese Neonatal Association Expert Consensus on management of neonates at high risk of COVID-19[3].

2.2 Data collection

Neonatologists identified all neonates born to mothers with confirmed or presumed COVID-19 between January 20, 2020, and February 20, 2020. Data were extracted from the mother's clinical records including age, history of exposure to COVID-19, mode of delivery, gestational age at delivery, diagnosis of diabetes or hypertension during pregnancy, whether she had any fever or cough prior to labor and delivery, leucocyte counts and chest imaging results (mostly CT scans). For each neonate the attending neonatologist recorded the birth weight, Apgar score at 1 and 5 minutes, any signs of fever or dyspnea during hospitalization, laboratory and chest imaging results (mostly X-rays), and feeding practices. Two investigators (YJ and RZX) independently reviewed all data collected to verify the accuracy.

Mothers suspected of COVID-19 were tested for SARS-CoV-2 during pregnancy using samples obtained from throat and/or nasal pharyngeal swabs. Most women were tested during the late third trimester when they were admitted with symptoms, but the exact gestational age at testing was not recorded. For neonates, upper respiratory tract and anal swab specimens were obtained and tested for SARS-CoV-2 between 1 and 48 h after birth, as per national policy. For neonates with a positive initial PCR test result, repeated tests were performed until discharge. No samples from cord blood, placenta, amniotic fluid or birth canal were collected. Laboratory confirmation of COVID-19 was performed in labs certified for SARS-CoV-2 PCR testing by the National Health Commission of China[14].

2.3 Further improvement suggestions on improvement of managing neonates at high risk COVID-19

After breakthrough of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic in China, CNA invited members to comment on the consensus and provide suggestions for further improvement on the four key measurements including isolation, laboratory investigation, breastfeeding and vaccination.

2.4 Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 21.0 (IBM, USA). Descriptive univariate analyses were performed on clinical and laboratory characteristics of mothers and neonates by whether the mother had been tested positive or negative for SARS-CoV-2. Chi-squared tests were used to identify differences between SARS-CoV-2 positive and negative mothers.

2.5 Patient and public involvement

This was a retrospective case series study, and no patients were involved in the study design or in setting the research questions or the outcome measures directly. No patients were asked to advise on interpretation or writing up of results.

3 Results

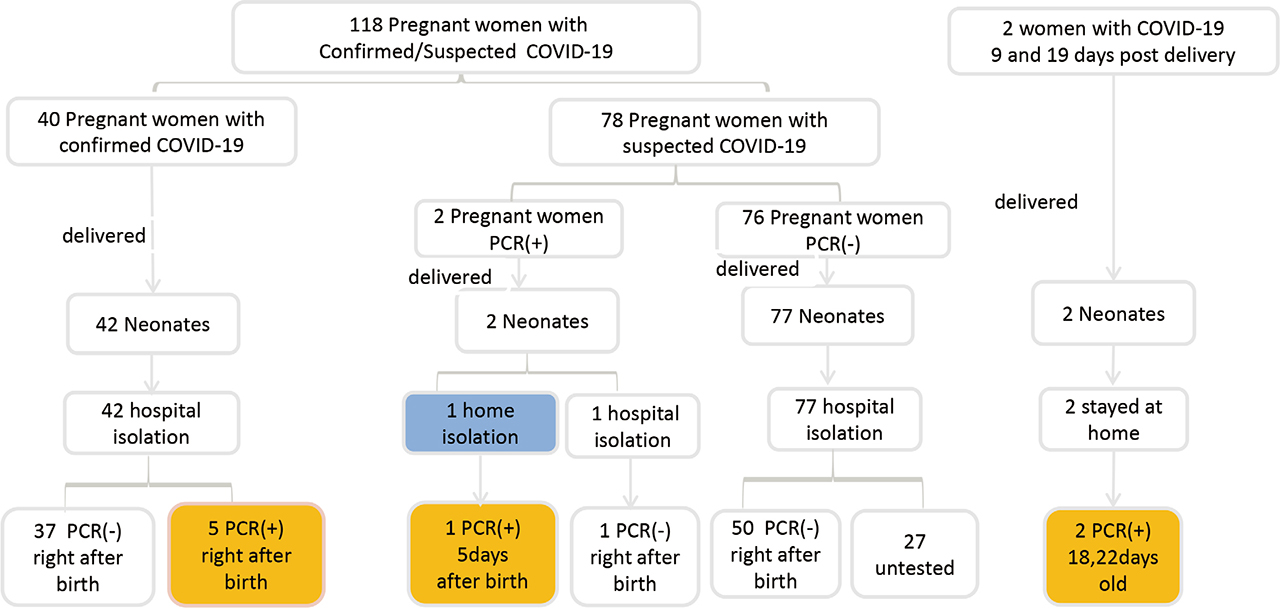

Between January 20, 2020 and February 20, 2020, 137 mothers and 140 neonates (3 pairs of twins) were recruited into the study. Most mothers were from Hubei (N = 58, 42.3%) or Guangdong (N = 37, 27.0%) province, and the others were from Jiangxi (8), Hunan (7), Henan (5), Shaanxi (5), Jiangsu (4), Zhejiang (4), Gansu (3), Anhui (2), Beijing (1), Shanxi (1), Ningxia (1) or Chongqing (1). 31 (22.6%) neonates were admitted to the Wuhan Children's Hospital, 11 (8.0%) to the Hubei Provincial Maternal and Child Health Hospital, and 10 (7.3%) to the Shenzhen Maternal and Child Health Hospital, with the rest to other hospitals with far fewer cases to each (mostly one or two). Nineteen of the 137 mothers suspected of COVID-19 during pregnancy were excluded due to the lack of available PCR testing in some hospitals early in the epidemic. Of the remaining 118 mothers with known PCR test results, 42 were tested positive for SARS-CoV-2: 40 were confirmed before delivery and 2 were suspected prenatally but only confirmed postnatally (within 24 h postpartum). The maternal-neonatal management procedures were shown in Fig. 1.

Management of neonates born to pregnant women with confirmed/suspected COVID-19

Most mothers were between 20 and 29 years old, with no difference between those being tested positive and negative for SARS-CoV-2. Women tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 were more likely to have given birth by caesarean section (88.1%) than SARS-CoV-2 negative women (63.2%, P = 0.004). The baseline clinical characteristics of mothers included in the present analysis are summarized in Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of mothers with confirmed or suspected COVID-19

| Characteristics | Mothers positive for SARS-CoV-2 (N = 42) | Mothers negative for SARS-CoV-2 (N = 76) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0.448 | ||

| 20–24 | 1 (2.4%) | 5 (6.6%) | |

| 25–29 | 16 (38.1%) | 30 (39.5%) | |

| 30–34 | 20 (47.6%) | 27 (35.5%) | |

| ≥35 | 5 (11.9%) | 14 (18.4%) | |

| Caesarean section, N (%) | 37 (88.1%) | 48 (63.2%) | 0.004 |

| Complications during pregnancy | |||

| Diabetes, N (%) | 16 (38.1%) | 16 (21.0%) | 0.046 |

| Hypertension, N (%) | 10 (23.8%) | 7 (9.2%) | 0.031 |

| History of exposure to COVID-19 | 41 (97.6%) | 67 (88.2%) | 0.155 |

| Signs and symptoms | |||

| Fever, N (%) | 28 (66.7%) | 49 (64.5%) | 0.811 |

| Cough or sore throat, N (%) | 21 (50.0%) | 18 (23.7%) | 0.004 |

| Neutrophil count<9.5×109/L | 37 (94.9%)* | 40 (53.3%)* | <0.001 |

| Lymphocyte count (<1×109/L) | 4 (10.3%) | 8 (10.7%) | 1.000 |

| Abnormal Chest imaging, N (%) | 39 (95.1%)δ | 45 (72.6%)δ | 0.009 |

- *

39 of 42 mothers with confirmed COVID-19 and 75/76 mothers with negative test results had routine blood results.

- δ

41 of 42 mothers with confirmed COVID-19 and 62/76 mothers with negative test results had chest imaging.

121 neonates, including three pairs of twins, were born to the 118 mothers included in this study. Among 44 neonates born to mothers testing positive for SARS-CoV-2, 34.1% were born at less than 37 weeks, compared to 20.8% for those born to SARS-CoV-2 negative mothers (P = 0.107). Similarly, 25.0% were low birthweight, compared to 18.2 % in those born to negative mothers (P = 0.566). Proportionally more neonates born to SARS-CoV-2 positive mothers had poor Apgar scores at one and 5 minutes (P = 0.377 and 0.269 respectively), but all neonates survived. Neonates born to SARS-CoV-2 positive mothers were more likely to have fever (34.1% vs. 13.0%, P = 0.006) and abnormal chest imaging (60.0% vs. 46.3%, P = 0.189) than those born to SARS-CoV-2 negative mothers (chest imaging was missing for 27 babies). Their baseline clinical characteristics are listed in Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of neonates born to mothers with confirmed or suspected COVID-19

| Neonates born to mothers with confirmed COVID-19 (N = 44)* | Neonates born to mothers without confirmed COVID-19 (N = 77)# | t/χ2 | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gestational age at delivery, N (%) | 3.422 | 0.181 | ||

| ≤33 week | 5 (11.4) | 8 (10.4) | ||

| 34–36 week | 10 (22.7) | 8 (10.4) | ||

| 37–41 week | 29 (65.9) | 60 (77.92) | ||

| ≥42 week | 0 | 0 | ||

| Premature, N (%) | 15 (34.1) | 16 (20.8) | 2.604 | 0.107 |

| Birth weight, N (%) | 2.033 | 0.566 | ||

| ≤1000 g | 0 | 0 | ||

| >1 000–1 500 g | 0 | 2 (2.6) | ||

| >1 500–2 500 g | 11 (25.0) | 14 (18.2) | ||

| >2 500–4 000 g | 32 (72.7) | 60 (77.9) | ||

| >4 000 g | 1 (2.3) | 1 (1.3) | ||

| Female sex, N (%) | 18 (40.9) | 35 (45.5) | 0.235 | 0.628 |

| Apgar score, N (%) | ||||

| ≤7 at 1 min after birth | 5 (11.4) | 4 (5.2) | 0.781 | 0.377 |

| ≤7 at 5 min after birth | 3 (6.8) | 1 (1.4) | 1.221 | 0.269 |

| Signs and symptoms | ||||

| Fever (≥ 37.3°C), N (%) | 15 (34.1) | 10 (13.0) | 7.608 | 0.006 |

| Dyspnea, N (%) | 14 (31.8) | 25 (32.5) | 0.005 | 0.941 |

| No symptoms, N (%) | 20 (45.5) | 49 (63.6) | 3.777 | 0.052 |

| Chest imaging | ||||

| Abnormal, N (%) | 24 (60.0)$ | 25 (46.3)Φ | 1.729 | 0.189 |

| Feeding mode, N (%) | ||||

| Exclusively Breastfeeding | 0 | 2 (2.6) | 0.113 | 0.736 |

| Formula feeding | 40 (90.9) | 62 (80.5) | 2.283 | 0.131 |

| Mixed feeding | 4 (9.1) | 9 (11.70) | 0.019 | 0.890 |

| Nil by mouth | 0 | 4 (5.2) | 1.018 | 0.313 |

| SARS-CoV-2 PCR | ||||

| Isolation unit, N (%) | 44 (100) | 50 (64.9) | ||

| Performed, N (%) | ||||

| Not isolated | 1 (2.3) | 0 | ||

| Primary care | 14 (31.8) | 58 (75.3) | 24.037 | 0 |

| Special care | 29 (65.9) | 19 (25.7) | ||

| Intensive care | 0 | 0 | ||

- *

Includes 2 pairs of twins.

- #

Includes 1 pair of twins.

- $

40 of 44 cases in neonates born to mothers with prenatally confirmed COVID-19 had chest imaging.

- Φ

54 of 77 cases in neonates born to mothers with prenatally suspected/postnatally PCR-negative had chest imaging.

All neonates were isolated in a single room immediately after birth, except for one baby born to a mother who was only found to be SARS-CoV-2 positive postnatally. 72 neonates were isolated in a primary care isolation unit (14 in SARS-CoV-2 positive mothers and 58 in SARS-CoV-2 negative mothers), and 48 in a special care isolation unit (29 in positive mothers and 19 in negative mothers) (P = 0.000). Most neonates were exclusively formula fed, with no difference between the groups (90.9% vs. 80.5%, P = 0.131). A few neonates who received mixed feeding were fed expressed breastmilk and formula milk.

94 neonates were tested for SARS-CoV-2, and the rest 27 neonates without test were all born to mothers without confirmed SARS-CoV-2. Six neonates were tested positive for SARS-CoV-2. Five neonates were born to mothers who tested positive during pregnancy, including one set of twins (neonate 1 and 2 in Table 3). These five neonates tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 on initial testing between 36 and 46 h after birth, with tests becoming negative between 3 and 7 days after birth (Table 3). Among 2 postnatally confirmed mothers, one neonate was asymptomatic and discharged after birth, but tested positive 5 days later when the parents returned to the hospital because the baby was ill. One neonate was isolated after birth and tested negative. Among the 6 SARS-CoV-2 positive neonates, two were born premature, one had birth asphyxia, and all had fever and/or respiratory distress with abnormal chest imaging. All 6 neonates were born by caesarean and were exclusively bottle fed.

Clinical characteristics of neonates with positive PCR SARS-CoV-2 testing and select characteristics of their mothers

| Neonate 1 | Neonate 2 | Neonate 3 | Neonate 4 | Neonate 5 | Neonate 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mothers | ||||||

| Age (years) | 32 | 32 | 33 | 30 | 32 | 27 |

| Diabetes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Hypertension | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Fever | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Cough or sore throat | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Chest radiography | Normal | Normal | Abnormal | Abnormal | Abnormal | Abnormal |

| Leukocyte count (×109/L) | 6.3 | 6.3 | 3.6 | 8.8 | 6.9 | 7.9 |

| PCR-positive prior to delivery | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Neonates | ||||||

| Gestational age | 31w+2 | 31w+2 | 40w+0 | 40w+6 | 39w+1 | 38w+5 |

| Birthweight (g) | 1580 | 1580 | 3250 | 3360 | 3500 | 3300 |

| Caesarean section | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Apgar score (1 min, 5 min) | 3, 4 | 8, 9 | 8, 9 | 9, 10 | 9, 10 | 9, 10 |

| Fever | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Tachypnea | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No |

| Chest radiography | Abnormal | Abnormal | Abnormal | Abnormal | Abnormal | Abnormal |

| Leukocyte count (×109/L) | 4.8 | 4.3 | 7.4 | 17.9 | 12.2 | 7.3 |

| SARS-CoV-2 PCR test result* | ||||||

| 1st testing | 36 h Nasal pharyngeal swab (+) Anal swab (+) |

36 h Nasal pharyngeal swab (+) Anal swab (+) |

40 h Nasal pharyngeal swab (+) Anal swab (+) |

46 h Nasal pharyngeal swab (+) Anal swab (+) |

38 h Nasal pharyngeal swab (+) Anal swab (+) |

5 days Nasal pharyngeal swab (+) Anal swab (+) |

| 2nd testing | 3 days Nasal pharyngeal swab (−) Anal swab N/A |

4 days Nasal pharyngeal swab (+) Anal swab N/A |

4 days Nasal pharyngeal swab (+) Anal swab (+) |

3 days Nasal pharyngeal Nasal swab (+) Anal swab N/A |

4 days pharyngeal swab (−), Anal swab N/A |

N/A |

| Isolated immediately after birth | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Breastfeeding or received expressed breast milk | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Outcome | Discharged | Discharged | Discharged | Discharged | Discharged | Discharged |

- *

Hours or days after birth

Regarding the confusion on the clinical management guidelines, 58.78% were put into isolation, 32.22 % were subjected to PCR test, and 5.16% and 2.75% received breastfeeding and vaccination, respectively. The data are shown in Fig. 2.

Suggestion on improvement of managing high risk COVID-19 neonates

4 Discussion

Here, we report management of 121 neonates born to 118 COVID-19 suspected mothers, of whom 42 were SARS-CoV-2 positive and 76 SARS-CoV-2 negative. In the present study, many babies were asymptomatic but about a third had signs of fever and dyspnea. In a cohort study, all neonates born between March 22, 2020 and May 17, 2020, had no symptoms of COVID-19[12], so there was no relationship between the season and the diseases.

The clinical, laboratory and imaging findings among pregnant women suspected of COVID-19 were similar to those found by other research teams[12, 15–18].

In our study, all neonates born to mothers with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 were isolated for 14 days or more. For neonates born to mothers with suspected infection, isolation was released once the mothers’ Covid-19 had been excluded, no matter whether the neonates were symptomatic or not. For neonates born to mothers with confirmed Covid-19 the isolation duration is no less than 14 days, following advice from the Chinese Neonatologist Association Expert Consensus on management of neonates at high risk of COVID-19. Isolation precautions are intended to minimize pathogen transmission and reduce hospital-acquired infections[19]. However, the isolation process is time-consuming and medical resource-consuming. Furthermore, the potentially negative mid- and long-term effects caused by separation from the mother had been documented[20].

Therefore, the decision to isolate the baby should be carefully weighed against the evidence that neonates with COVID-19 are asymptomatic or only have mild symptoms. Longer isolation duration than necessary not only adds economic burden also brings about a risk of depriving resource for neonates in need. As stringent infection control measures for prevention of cross infection between high-risk infants and neonates with other problems are very important.

The decision on isolating neonates should be based on the possibility of maternal-fetal vertical transmission. No direct evidence has thus far been found for SARS-CoV-2 maternal-fetal vertical transmission no matter in single centre cohort study or in systemic review[7,8,9,10,11,15,16,17,18]. We should consider whether the Chinese Neonatologist Association Expert Consensus on management of neonates at high risk of COVID-19 was too stringent in isolation. Secondly, the decision on isolation should be based on PCR result of mother and neonate. In our study, 19 (13.87%) of the 137 mothers suspected of COVID-19 during pregnancy were excluded due to lack of available PCR testing, 27 neonates (22.31%) were not tested for COVID-19. The PCR test should be conducted in all suspected mothers, once the mothers’ infection is ruled out, neonatal isolation should be released without any COVID-19 nucleic acid PCR tests. Timely SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid PCR tests for suspected mothers is strongly recommended, because it may reduce isolation duration of their neonates and avoid wasting medical resource and exhausting medical staff.

A recent study in the UK found that most neonates born to mothers with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 had mild symptoms, though 12 (5%) subsequently had a positive test for SARS-CoV-2[18]. Salvatore and colleagues reported the management and outcomes of 120 neonates born to 116 mothers who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 at delivery in New York City. All neonates were allowed to room-in with mothers and breastfeed, if medically appropriate. The analysis included 68 (83%) neonates roomed in. Neonates were kept in a closed isolette 6 feet (1.83 m) apart from mothers, except during feeding. No neonates tested positive by nasopharyngeal swab at 12–24 h, 5–7 days, or 14 days, and all neonates remained asymptomatic[12]. The study showed that rooming-in are safe when accompanied by mother wearing mask and with frequent hand hygiene. They concluded that SARS-CoV-2 transmission to neonates from infected family members is unlikely when proper precautions are taken. In our study, the neonatal PCR positive rate was 5/137(3.65%) under the strict isolation and no breast milk feeding conditions. When compared to the report by Salvatore and colleagues, our neonatal PCR positive rate was high. This hinted that unnecessarily neonatal isolation might exist in our management.

In our study, babies were isolated from their mothers immediately after birth and very few babies were breastfed. Current WHO guidance recommends breastfeeding by mothers with mild symptoms of COVID-19, using appropriate precautionary measures such as hand hygiene precautions and face mask[21]. Maintaining physical separation of more than 2 m at other times is also recommended in the systemic review[12]. The study reported by Salvatore and colleague showed that breastfeeding were safe in 64 (78%) neonates at day 5–7 and 45 (85%) of 53 followed-up at 1 month[12]. However, mask wearing and frequent hand and breast hygiene are important because there is evidence that SARS CoV 2 RNA can be present in human breast milk[22], which raised the possibility baby infection through breast milk.

Regarding confusion on the clinical management guidelines, 58.78% are for isolation, 32.22 % are for PCR tests, 5.16% and 2.75% are for breastfeeding and vaccination respectively. All these problems that confused the Chinese clinicians in daily work needed to be improved. In addition, these items were also main differences between the guideline of Chinese Neonatologist Association and that of American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Fetus and Newborn (AAP)[23] American Association of Obstetrics and Gynecologists[24–25].

5 Conclusions

In summary, we analyzed the data collected from a Chinese mother-neonates cohort in the early phase of the global pandemic and found a high isolation rate and a low breast feeding rate compared with the clinical reports from other countries and systemic reviews[12,18]. Considering the increasing research evidence for the low necessity for isolation, the suggestions from Chinese neonatologists for improvement of the management of neonates, and the lack of scientific ground for the guidelines set by the Chinese Neonatologist Association comparing with those by other countries, we proposed that it is time to revisit the isolation and breastfeeding strategy on management of neonates born to mothers with COVID-19. Separation of the mother and her newborn should be assessed on a case-by-case basis, considering the availability of local facilities and risk factors for adverse outcomes, such as prematurity and fetal distress. COVID-19 should not be an indication for formula feeding or isolation of the infant from the mother.

Availability of data and material

Data are available on various websites and have been made publicly available (more information can be found in the first paragraph of the Results section).

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ contributions

ZC F study design and organization. JY and ZX R study co-design, data review and report writing. LK Z, SW X and YS, study co-design, and patient recruitment. data review and report writing. JY M, data input. ZZ, data review and report writing. LW, LC. WL, study co-design and regional coordinator. CR edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

Funding from the Department of Maternal and Child Health, National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China: Construction and Evaluation of Neonatal Intensive Care System in China (201906063).

This manuscript benefited with technical inputs from Dr. Xiaona Huang (UNICEF China), Dr. Michelle Dynes (UNICEF East Asia and Pacific), and Ms. Anuradha Narayan (UNICEF China). We sincerely thank members of CNA for their efforts in recruiting patients.

References

[1] World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) Situation dashboard. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2021.Search in Google Scholar

[2] National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China. The latest situation of novel coronavirus pneumonia as of 24:00 on 17 September 2021. Available at: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/wjw/index.shtml. Accessed on Sep 17, 2021. (Chinese).Search in Google Scholar

[3] Yang J, Feng Z C. On behalf of the Chinese Neonatologist Association. Proposed management on 2019 novel coronavirus infection in neonates. Chin J Perinat Med, 2020; 23: 80–82. (Chinese).Search in Google Scholar

[4] Wang J H, Qi H B, Bao L, et al. A contingency plan for the management of the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak in neonatal intensive care units. Lancet Child Adolesc Health, 2020; 4(4): 258–259.10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30040-7Search in Google Scholar

[5] Li F, Feng Z C, Shi Y. Proposal for prevention and control of the 2019 novel coronavirus disease in newborn infants. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed, 2020; 105(6): fetalneonatal-2020-318996.10.1136/archdischild-2020-318996Search in Google Scholar

[6] Chen L, Li Q, Zheng D, et al. Clinical characteristics of pregnant women with Covid-19 in Wuhan, China. N Engl J Med, 2020; 382(25): e100.10.1056/NEJMc2009226Search in Google Scholar

[7] Chen H, Guo J, Wang C, et al. Clinical characteristics and intrauterine vertical transmission potential of COVID-19 infection in nine pregnant women: a retrospective review of medical records. Lancet, 2020; 395(10226): 809–815.10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30360-3Search in Google Scholar

[8] Zeng L, Xia S, Yuan W, et al. Neonatal early-onset infection with SARS-CoV-2 in 33 neonates born to mothers with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Pediatr, 2020; 174(7): 722–725.10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.0878Search in Google Scholar

[9] Zhu H, Wang L, Fang C, et al. Clinical analysis of 10 neonates born to mothers with 2019-nCoV pneumonia. Transl Pediatr, 2020; 9(1): 51–60.10.21037/tp.2020.02.06Search in Google Scholar

[10] Yu N, Li W, Kang Q, et al. Clinical features and obstetric and neonatal outcomes of pregnant patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective, single-centre, descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis, 2020; 20(5): 559–564.10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30176-6Search in Google Scholar

[11] Walker K F, O’Donoghue K, Grace N, Dorling J, Comeau J L, Li W, et al. Maternal transmission of SARS-COV-2 to the neonate, and possible routes for such transmission: a systematic review and critical analysis. BJOG, 2020;127(11): 1324–1336.10.1111/1471-0528.16362Search in Google Scholar

[12] Salvatore C M, Han J Y, Acker K P, et al. Neonatal management and outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic: an observation cohort study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health, 2020; 4(10): 721–727.10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30235-2Search in Google Scholar

[13] National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China. New coronavirus pneumonia prevention and control program (6th edition). Available at: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/yzygj/s7653p/202002/8334a8326dd94d329df351d7da8aefc2.shtml. Accessed on Oct 5, 2020.Search in Google Scholar

[14] National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China. Guideline for laboratory testing of new coronary virus pneumonia. Available at: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/xcs/zhengcwj/202002/a5d6f7b8c48c451c87dba14889b30147/files/3514cb996ae24e2faf65953b4ecd0df4.pdf. Accessed on Oct 5, 2020. (Chinese).Search in Google Scholar

[15] Lokken E M, Walker C L, Delaney S, et al. Clinical characteristics of 46 pregnant women with a SARS-CoV-2 infection in Washington State. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 2020; 223(6): 911.e1–911.e14.10.1016/j.ajog.2020.05.031Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] Schmid MB, Fontijn J, Ochsenbein-Kölble N, et al. COVID-19 in pregnant women. Lancet Infect Dis, 2020; 20(6): 652–653.10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30175-4Search in Google Scholar

[17] Breslin N, Baptiste C, Gyamfi-Bannerman C, et al. COVID-19 infection among asymptomatic and symptomatic pregnant women: Two weeks of confirmed presentations to an affiliated pair of New York City hospitals. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM, 2020; 2(2): 100118.10.1016/j.ajogmf.2020.100118Search in Google Scholar

[18] Knight M, Bunch K, Vousden N, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of pregnant women hospitalised with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection in the UK: a national cohort study using the UK Obstetric Surveillance System (UKOSS). BMJ, 2020; 369: m2107.10.1101/2020.05.08.20089268Search in Google Scholar

[19] Landelle C, Pagani L, Harbarth S. Is patient isolation the single most important measure to prevent the spread of multidrug-resistant pathogens? Virulence, 2013; 4(2): 163–171.10.4161/viru.22641Search in Google Scholar

[20] Sprague E, Reynolds S, Brindley P. Patient isolation precautions: are they worth it? Canadian Respiratory Journal, 2016; 2016: 5352625.10.1155/2016/5352625Search in Google Scholar

[21] World Health Organization. Q&A: Breastfeeding and COVID-19. Available at: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/question-and-answers-hub/q-a-detail/q-a-on-covid-19-and-breastfeeding. Accessed on May 7, 2020.Search in Google Scholar

[22] Chambers C D, Krogstad P, Bertrand K, et al. Evaluation of SARS-CoV-2 in breastmilk from 18 infected women. medrXiv 2020; published online June 16. DOI:10.1101/2020.06.12.20127944 (preprint).Search in Google Scholar

[23] AAP issues guidance on infants born to mothers with suspected or confirmed COVID-19. Available at: https://www.aappublications.org/news/2020/04/02/infantcovidguidance040220. Accessed on May 7, 2020.Search in Google Scholar

[24] Favre G, Pomar L, Qi X, et al. Guidelines for pregnant women with suspected SARS-CoV-2 infection. Lancet Infect Dis, 2020; 20(6): 652–653.10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30157-2Search in Google Scholar

[25] Salvatore C M, Han J Y, Acker K P, et al. Neonatal management and outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic: an observation cohort study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health, 2020, 4(10): 721–727.10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30235-2Search in Google Scholar

© 2022 Jie Yang et al., published by Sciendo

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Review

- Dissecting pathophysiology of a human dominantly inherited disease, familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy, by using genetically engineered mice

- Effect of cold on knee osteoarthritis: Recent research status

- Original Article

- Effects of intermittent cold-exposure on culprit plaque morphology in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction patients: a retrospective study based on optical coherence tomography

- A randomized retrospective clinical study on the choice between endodontic surgery and immediate implantation

- Challenges and improvement in management of neonates born to mothers with COVID-19 in China

- Nortriterpenoids from the fruit stalk of Schisandra chinensis (Turcz.) Baill.

- Altered expression profile of long non-coding RNAs during heart aging in mice

- Cryptotanshinone increases the sensitivity of liver cancer to sorafenib by inhibiting the STAT3/Snail/epithelial mesenchymal transition pathway

Articles in the same Issue

- Review

- Dissecting pathophysiology of a human dominantly inherited disease, familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy, by using genetically engineered mice

- Effect of cold on knee osteoarthritis: Recent research status

- Original Article

- Effects of intermittent cold-exposure on culprit plaque morphology in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction patients: a retrospective study based on optical coherence tomography

- A randomized retrospective clinical study on the choice between endodontic surgery and immediate implantation

- Challenges and improvement in management of neonates born to mothers with COVID-19 in China

- Nortriterpenoids from the fruit stalk of Schisandra chinensis (Turcz.) Baill.

- Altered expression profile of long non-coding RNAs during heart aging in mice

- Cryptotanshinone increases the sensitivity of liver cancer to sorafenib by inhibiting the STAT3/Snail/epithelial mesenchymal transition pathway