Abstract

The weaving process is constantly evolving in terms of productivity, quality, and possibilities of fabrication of different fabric structures and shapes. This article covers some issues that have still not been resolved and represents distracting factors in the woven fabrics production. In the development of woven fabric using the CAD technology, it is inevitably a deviation of the virtual image on the computer screen from the woven sample. According to comprehensive industry analyses, the findings of many authors who contributed to the resolution of these problems can be concluded that these problems are still present in the development and production of striped, checkered, and jacquard woven fabrics. In this article, jacquard, multicolor woven fabrics were investigated, with deviations in pattern sizes and shades of color in warp and weft systems compared to virtual simulation on the computer, as well as the tendency of the weft distortion arising from the weaving process leading to the pattern deformation.

1 Introduction

The most common definition of woven fabrics is that “The fabric is a textile plannar product made of two thread systems that are interlaced together at right angle.” With today’s fabrication possibilities of different woven structures and shapes, this definition is no longer comprehensive. The fabric may not only consist of two systems and the position of thread systems does not have to be mutually perpendicular but it can be laid in different directions and in different 3D forms. Likewise, the interlacing of warp and weft is often not at right angles, despite their position at the time of weaving.

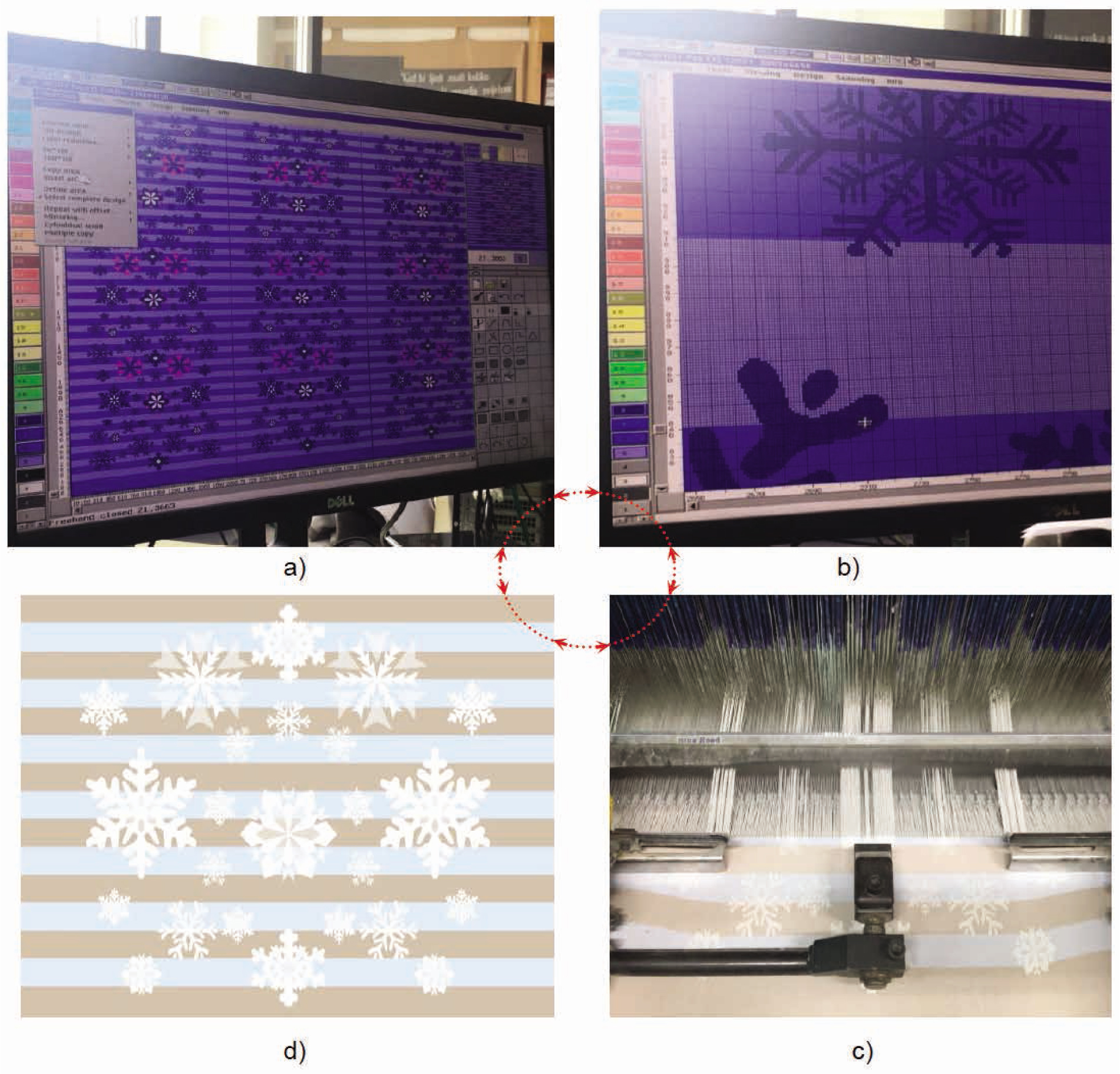

Continuous work on the development and production of new advanced woven fabrics that will compete in the market is a necessity for the survival of a textile company. To make fabrics meet all the market criteria in terms of quality and cost-effectiveness, extensive knowledge and engagement of textile technicians and textile designers are required. The production of the fabric of the appropriate characteristics is an extremely complex process that extends through several dozen phases with many obstacles and unpredictable problems, especially in the manufacture of jacquard and multicolored patterns [1,2,3,4]. Some of them were not fully mastered until today, as shown in Figure 1.

Deviation of the virtual pattern dimensions on the screen compared to the pattern dimension on the produced fabric

Deviation in color shades on the screen and on the fabric

Deviation in shades of color per fabric length

Weft distortion formed in the weaving process

Development flow of a new fabric pattern with the CAD-CAM system in weaving.

Each fabric, with a certain probability, may have some or more deviations, which means that every piece of fabric is in fact inimitable and unique, despite the development and improvement of the weaving process. Therefore, looking at the micro-to-the-macro scale, woven fabric is like a living being, unrepeatable and unique [5,6,7,8].

1.1 Deviation of the virtual image pattern dimensions on the screen compared to the pattern dimension in produced woven fabric

Making jacquard fabrics is not only an extremely complex, demanding, and expensive process but also a major challenge in creating patterns of unlimited possibilities in color combinations, weaves, yarn fineness, and the warp and the weft densities – to get a certain pattern on the fabric. The CAD/CAM systems in weaving technology enable the designer to create inexhaustible creations in a short time, making the weaving easier, faster, more economical and ensuring better production. This weaving system represents a firm synergy of preparation for weaving and fabric design, modern electronic weaving machines, and warp and weft compositions. CAD systems facilitate and accelerate the preparation and design of future woven fabrics. Their advantage is that it is possible to see the appearance of the fabric in a very short time and adjust all the parameters required to make the sample. On the basis of the parameters taken from the database (weave, densities, thread thickness, colors, etc.) and their combinations, the desired fabric virtual simulation can be very easily obtained. CAM systems allow quick set up of the machine, data storage, and databases archiving that are essential for weaving preparation and permanent optimization of the production. Some of the software solutions for woven fabric design and computer-supported woven fabric production management are EAT, NedGraphics, Arachne, ScotWeave, Design Dobby, Pointcarre Weave Design, and others.

Woven fabrics with jacquard patterns can have different types of weaves per pattern (effect), different colors of warp and weft, and different raw materials. Each pattern is made up of several effects that differ in at least one of the specified parameters. To make the better-highlighted effects, they often have their weaves, so, in that effect, the warp and weft are interlacing differently, which means they also have different crimp and consequently different shrinkage. This phenomenon does not have to create a problem in the weaving process, but the fabric relaxation, after removal from the machine, is shrinkage in the direction of the warp and the weft, which can lead to additive effects on the woven surface. The consequence of this is the change of dimension by effect, and by pattern. Differences in pattern dimensions are also influenced by other parameters such as tension of the warp and the weft threads during the weaving process, deviations in warp and weft density, and fineness of the warp and the weft threads and even in the colors. After yarn dyeing in different colors, the difference in the thickness of the yarn may occur, although these differences do not have to be noticeable in yarn fineness. In the experimental part of this article, the differences in the thickness of the yarn after dyeing and their impact on the width of the stripes in the fabric will be determined.

1.2 Distinction in the color shades of the virtual image on the screen compared to the woven fabric

When designing a woven fabric sample, the fabric parameters will be selected to get closer as much as possible to the original or preferred fabric appearance. The color catalog and their shades allow the selection of the color that will be approximately equal to the desired sample. As the color catalog is bigger, it is more likely to get the desired design. The evolution of jacquard textiles and accompanying technologies has led to more diverse design solutions and to the ability of production of more complex fabric structures that are most often highlighted in different colors. The traditional structural method remained relatively unchanged, though the jacquard computer applications had significantly increased design efficiency and contributed to innovations in design solutions.

The fabric pattern shown on the screen is very difficult to transfer to the fabric, when, at the same time, designing the fabric is more easily facilitated by using computer technology. Despite the modernization and automation of yarn dyeing machines, color recipe preparation, and drying, there are possible variances in yarn coloration that result from the characteristics of the fibers (their hydrophobicity and hydrophilicity) and the yarn (twist number and direction of twists, yarn tension at dyeing). The appearance of the fabric can deviate from the desired design, despite the well-adjusted color shade for the following reasons:

the yarn angle at the weaving point which is under the influence of stiffness and tension of the yarn (higher tension of one thread system enables the greater crimp of the other one allowing the larger bending in weave points and consequently greater visibility on the front side of the fabric)

weaves and their various geometries caused by different ways of thread interlacing and floating, for example, diagonal stripes direction at twill fabrics

warp and weft densities, or their ratio that affects the difference in coloration of the effect (higher density gives a more intense effect on the front side of the fabric, especially at the flotation places)

Deviations in color shadings per effects on the computer screen compared to the produced fabric can also be the result of a subjective assessment.

1.2.1 Deviation in color shades

For multicolored fabrics (striped or checkered), yarn dyeing is done before weaving. Warped yarn can be dyed before or after warping process. Warp yarn dying before the warping process and weft yarn before weaving is most commonly performed on cross-wound bobbins and nearly in tress shape. If the warp yarns are multicolored with more than 100 threads per color, then the more economical way of dyeing is on warp beams made by direct warping. Uneven coloration by the layers of cross-wound bobbins or warp beams is inevitable [9]. The inner layers of yarn on the cross-wound bobbin or warp may be lighter in shade than the outer layers and the layers beside the cone or warp roller tube. The result is an unevenly colored yarn whose further processing consequently gives a woven fabric with the stripes of shade variations on the surface, oriented in the direction of the warp or weft.

In the case of fabric dyeing after weaving, which is possible in the single color woven fabrics production, the color may vary gradually in shade over the fabric length due to the unequal concentration of dyeing agent in the dye bath at the beginning and the end of the dyeing process. By making garments from such fabrics, there is a risk of color differences of the joined parts, if they are separated from different parts of the fabric. In addition, when making uniforms, a common requirement is to have uniforms of the same colors, shades, and tones, and in such cases, the dyeing must be made in a fiber stage (dyeing of combed top).

1.2.2 Weft distortion

In woven fabrics, warp and weft should be positioned at the right angle one to another, but in certain situations, this is not the case. Weft distortions are usually smaller than few degrees and are not a big problem for single color fabrics.

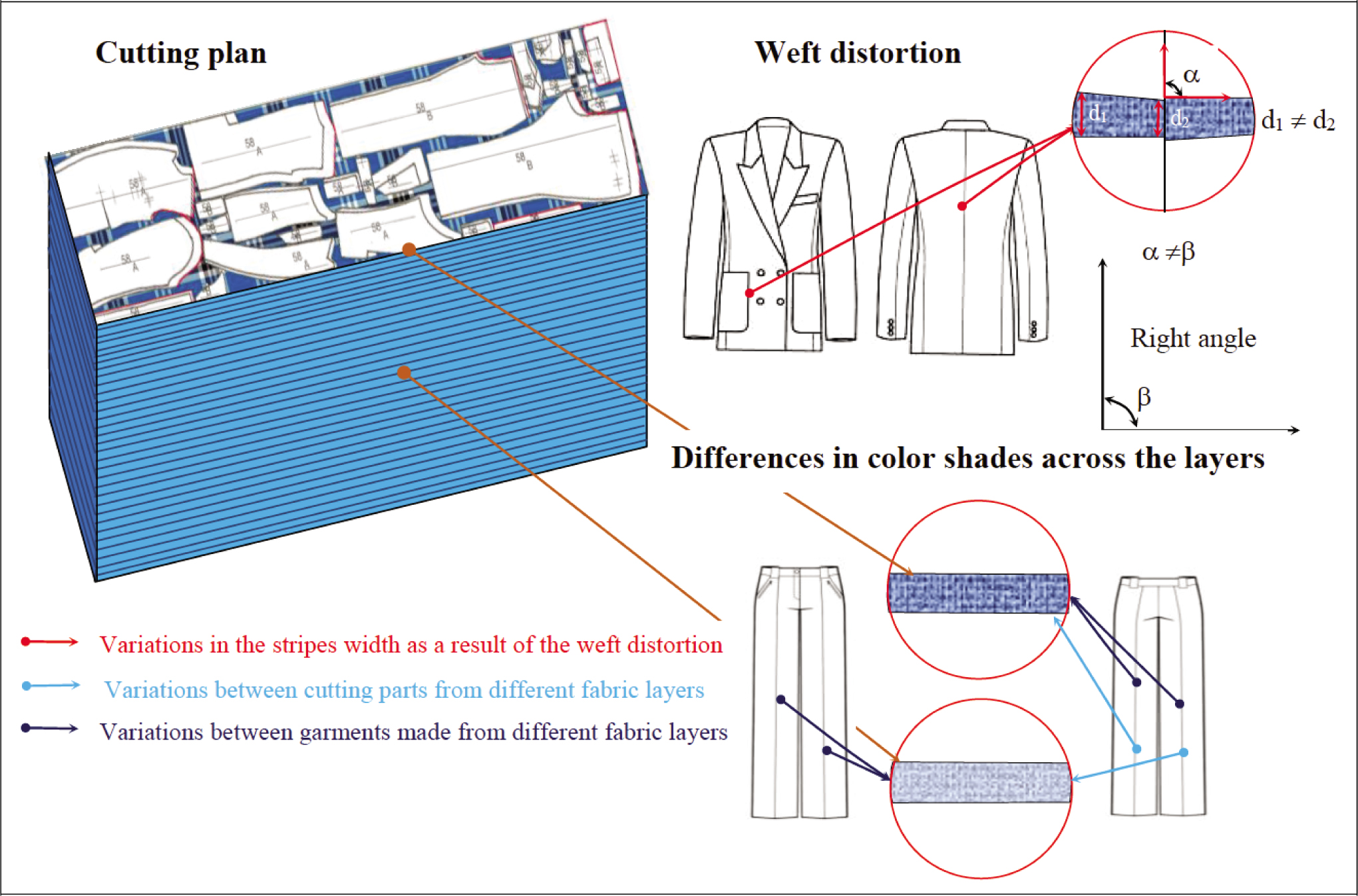

The appearance of the weft distortion causes the problem in the cutting room. In lay planning and marker making operations of a fabric with strips or checks, warp distortion will cause the strips or checks distortion. The consequence is the inability to overlap the lines of joined pattern pieces. Weft straightening is possible in the finishing process, but the result is uneven width between lines, which also leads to the same problems.

Parameters that affect a weft distortion could be divided into several groups:

Influence of yarn: twist direction, number of twists, fineness, surface treatment and raw material composition, tensile properties of fibers and yarns, spinning type, and others

Influence of the fabric structural parameters such as weave, the direction of structural diagonals that can result from the weave (twills and satins), the density of the warp and the weft and their ratio, woven fabric ends, the thread density, and the weave in the ends.

Impact of the weaving conditions: tension of the warp, tension of the weft, moment of closing and opening of the shed, and the duration and moment of weft beat-up, the direction of weft insertion, weft insertion type, weft insertion speed, type, and width of the machine.

Impact of the preparatory stages: warping method (direct or sectional), warping conditions (thread tension, warping machine automation, and uneven warp diameter by beam width).

Which parameter is more dominant, and which distortion shape can be expected, is still a major problem in designing fabric and planning the fabric’s qualitative features.

Some devices serve for tracking the position of the weft in the fabric on the loom after the fabric formation line and allow variable cloth take-up over the back roller width. Because of the sensitivity of these devices to vibration produced by looms and their high prices, they are not currently accepted in production but still make a big contribution to addressing these problems [10,11,12,13,14,15,16].

2 Experimental

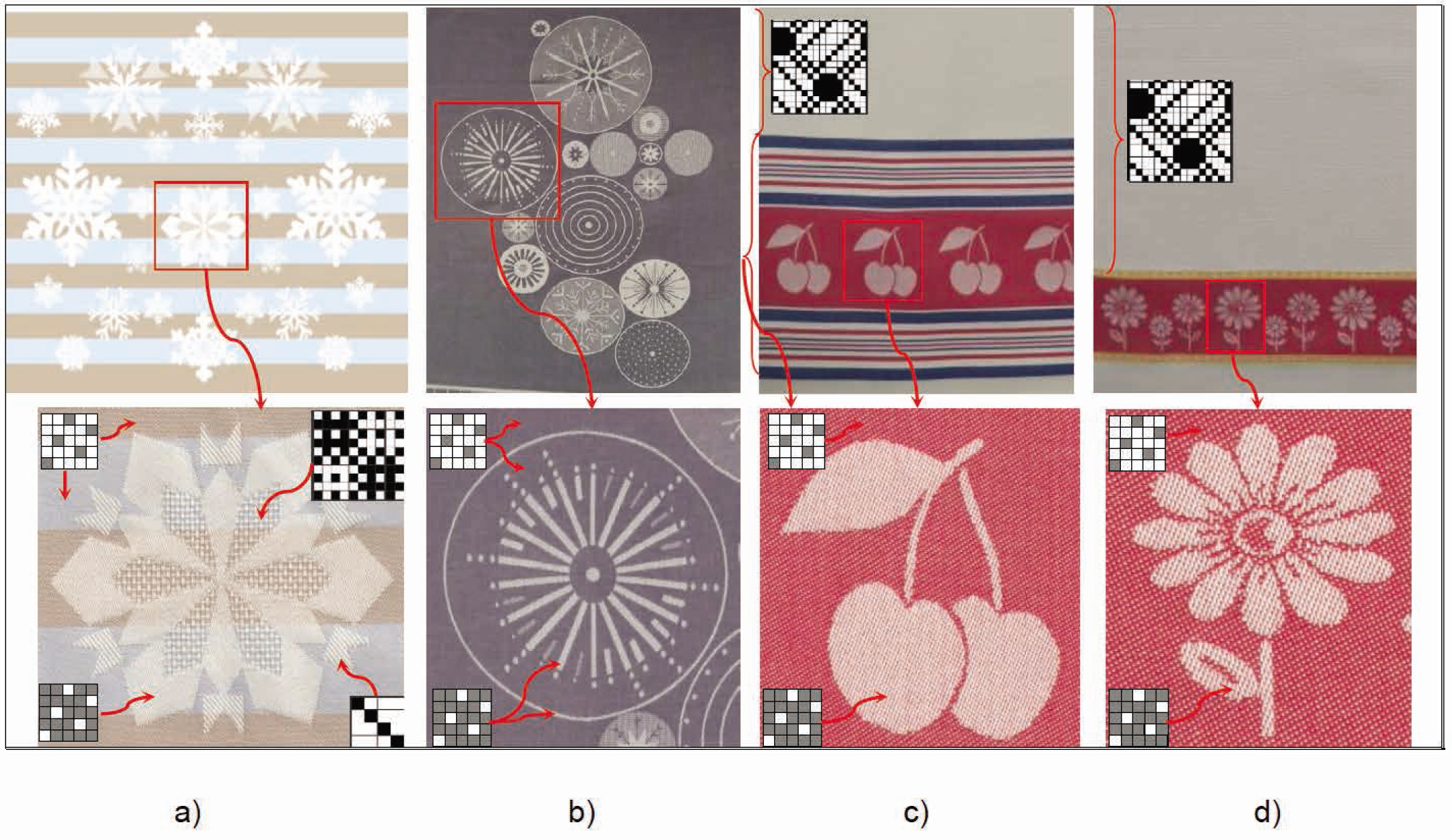

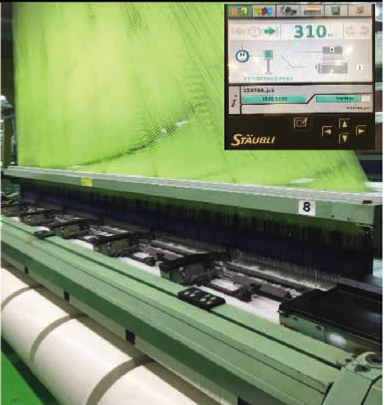

The tests were carried out on four newly developed cotton fabrics for table and linen. The fabrics were produced on the same jacquard weaving machine, from the yarn of the same structural features in the warp and weft. Weft is in different colors, and the fabrics are woven with different patterns (Figure 2). The basic characteristics of the machine are shown in Table 1.

Woven fabric samples for testing: (a) sample A, (b) sample B, (c) sample C, and (d) sample D.

Basic characteristics of the weaving machine

| Characteristics of the machine | Value |  |

| Weaving machine | Sulzer Rüti, P7200 B390N4J | |

| Jacquard | Staübli | |

| rpm (weft/min.) | 310 | |

| Weaving performance (m wefts/min.) | 1200 | |

| Maximum working width of the machine (cm) | 390 | |

| Maximum number of hooks | 4,400 |

3 Results and discussion

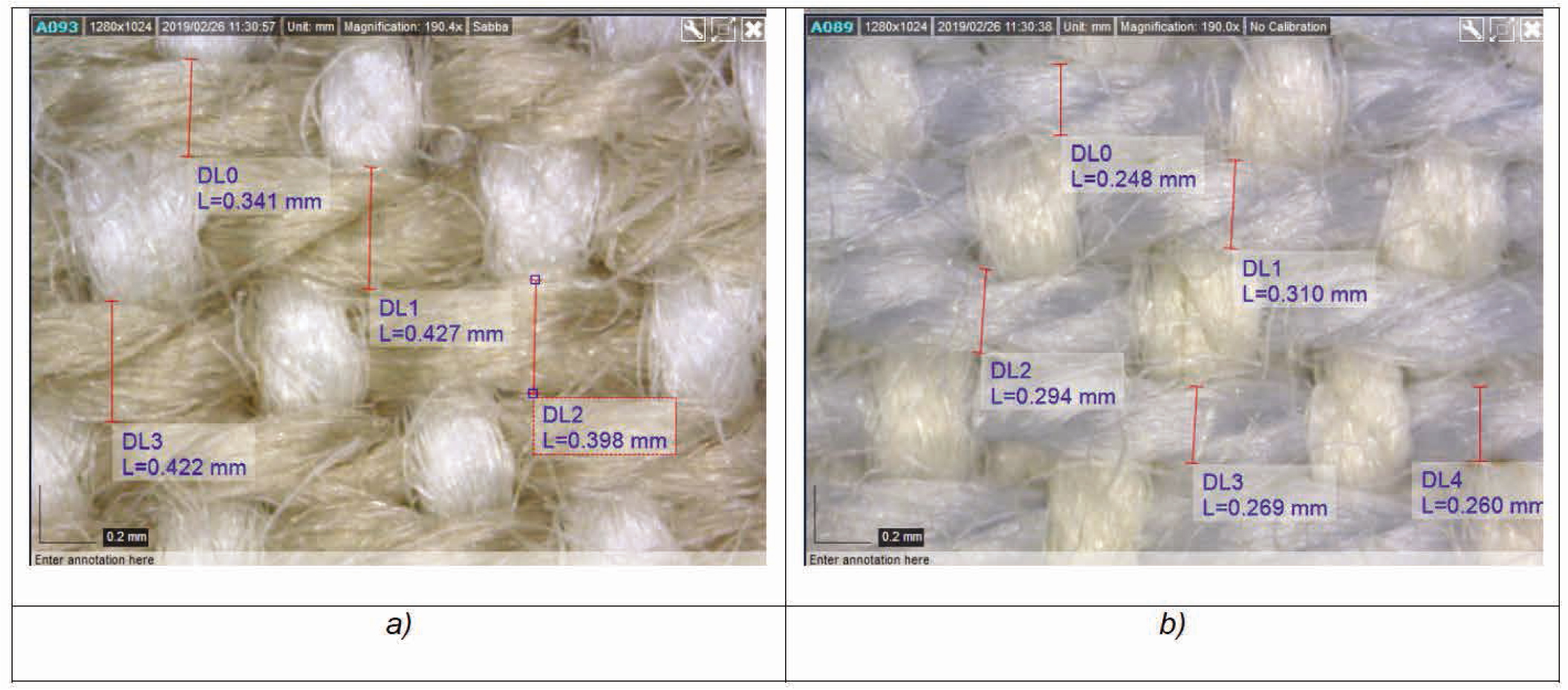

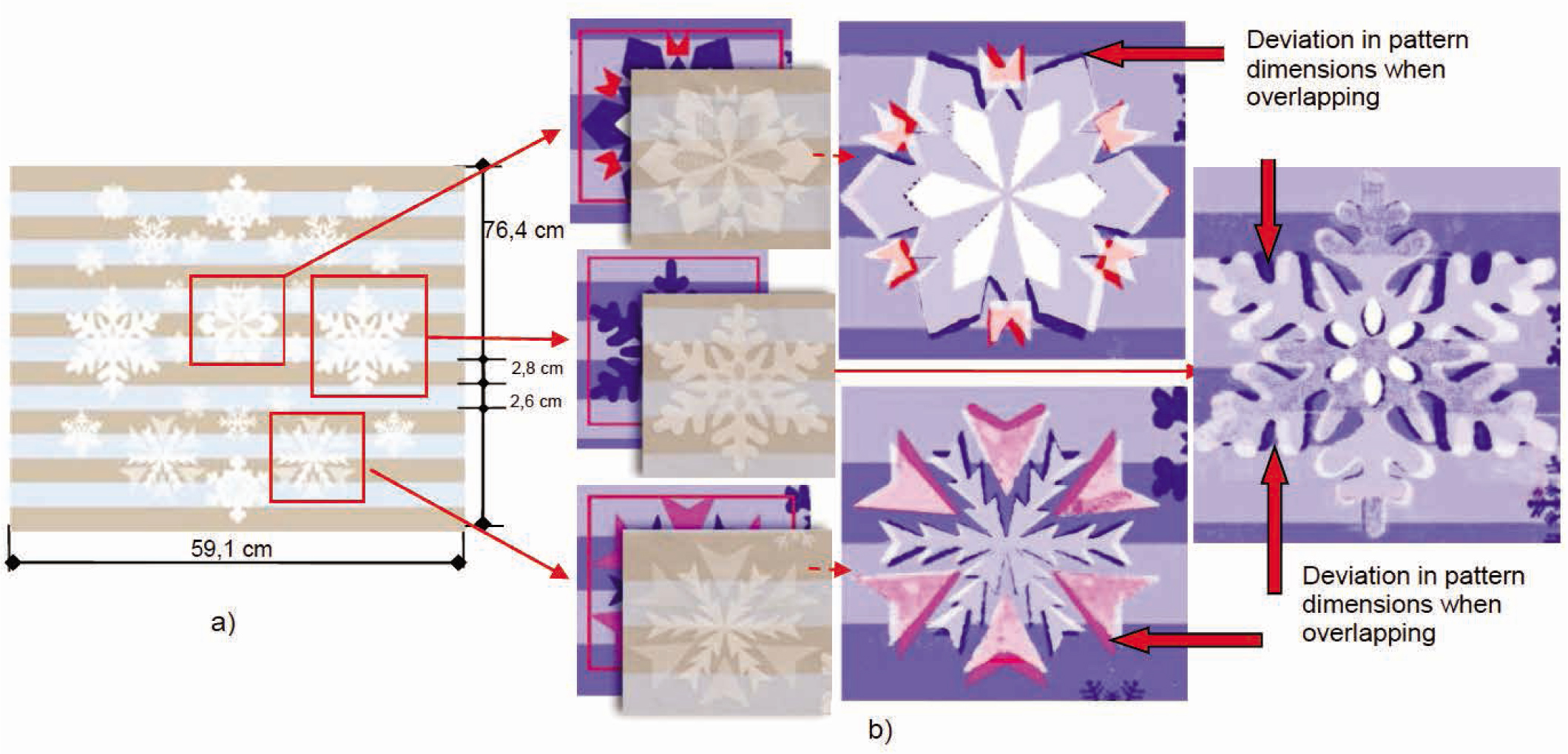

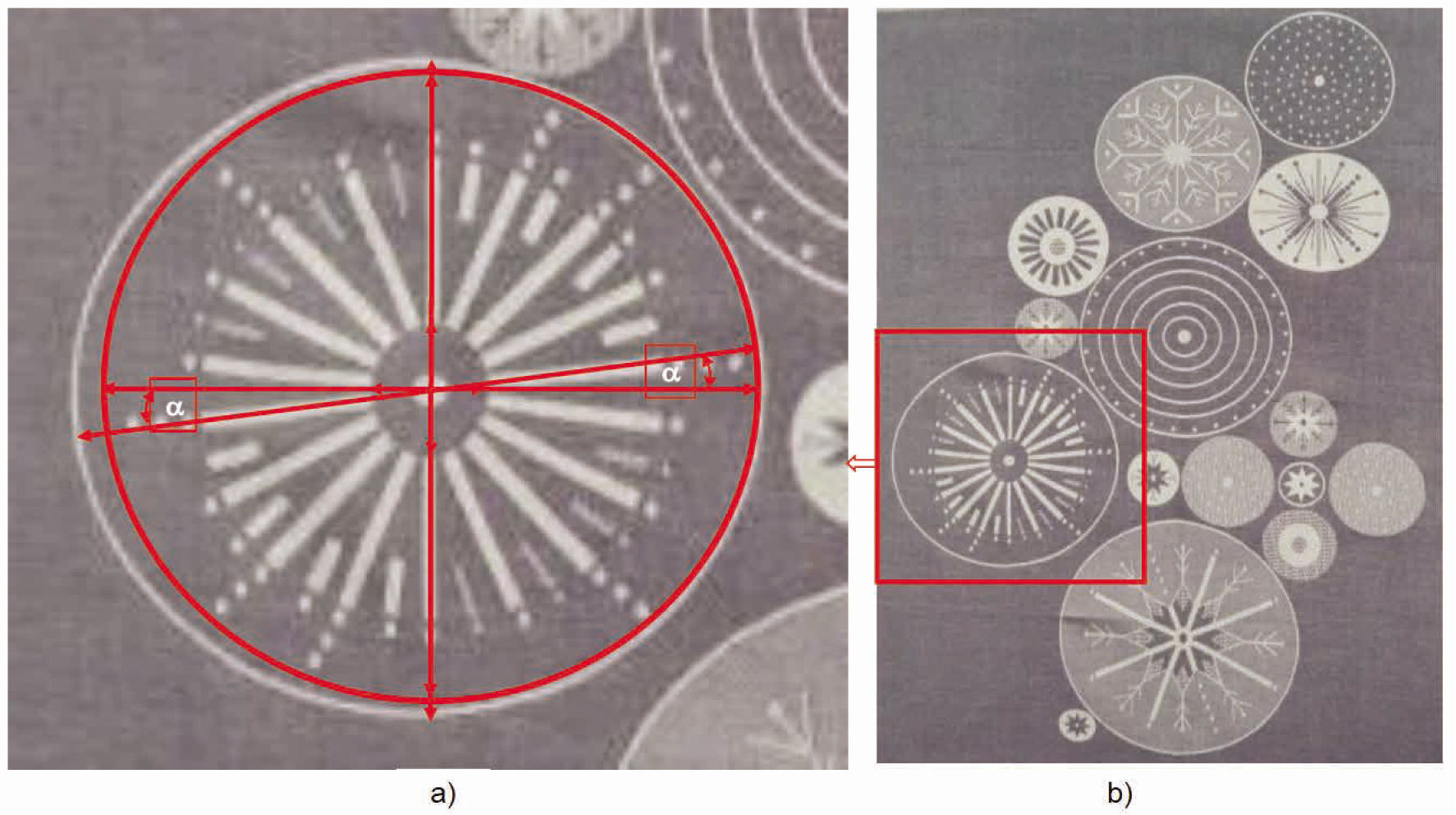

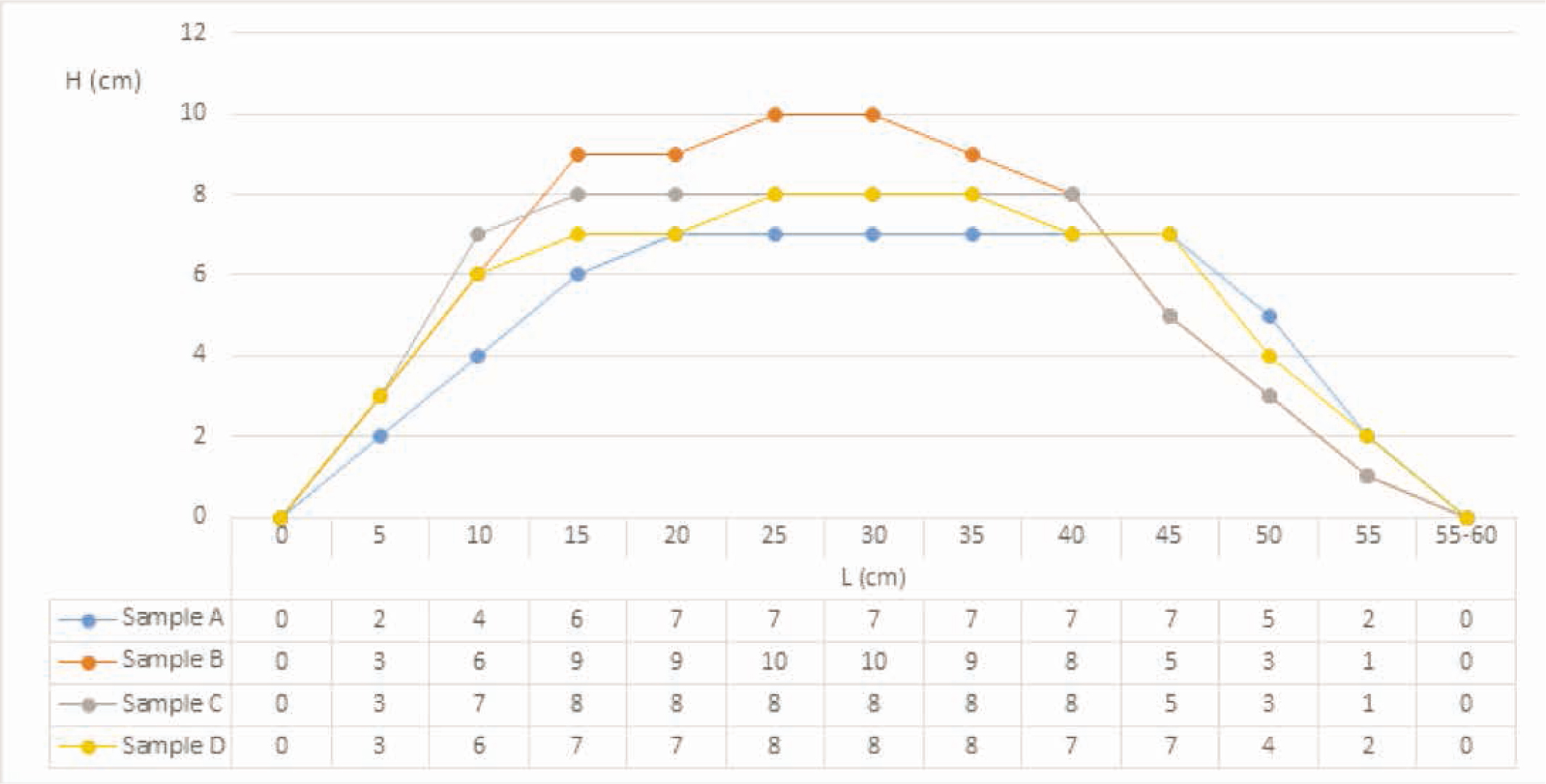

The yarn and fabric test results are shown in Table 2 and Figures 3–7. Fabric samples (A, B, C, and D) have been woven from the same warp and weft on the same weaving machine. The difference between the patterns is in the design, respectively, weave, and the weft colors. Although the weaving and material conditions are the same for all samples, there are differences in sample dimensions in the direction of the warp and the weft. Likewise, differences between widths of strips from different weft colors within the same sample (sample A) were confirmed, although the strips have the same number of weft threads. The color of the beige strip has an average width of 26.6 mm and an average thickness of one weft thread 0.333 mm, while the blue strip has a width of 26 mm and a thickness of the weft thread 0.326 mm, indicating that the yarn dyed in beige color is slightly more voluminous than the yarn dyed in blue color (Figure 3). Deviation of the patterns (fabric - drawing) can be seen by overlapping the individual segments in the sample (Figure 4 overlapping snowflakes). The differences are visible by main direction of the fabric. The larger the pattern gives the greater deviations. Weft distortion is best seen on samples with patterns in the shape of the circle and the ones closer to the edges (Figure 5). The greatest influence on the deformation of the pattern has a yarn density deviation and weft distortion.

Yarn and woven test results

| Tested values | Sample | Comparison of results of simulation vs. actual sample | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CAD/CAM | Actual woven fabric sample | ||

| Warp and weft density; (niti/cm/CV/%) | A | Warp: 40 Weft: 30 |

Warp: 37/0.63 Weft blue: 27.0/0.51; beige: 27.1/1.85 |

| B | Warp: 36.8/1.5 Weft dark blue: 27.3/2.7 |

||

| C | Warp: 37/1.3 Weft: base white: 27.1 - 1.29; pattern: 26.9/2.5 |

||

| D | Warp: 37/1.3 Weft: base white: 27.1/2.11; pattern: 27.0/2.0 |

||

| Warp and weft fineness (tex) | A, B, C, D | 16.5×2/16.5´2 | 16.5×2/16.5×2 |

| Sample dimensions (cm)/CV (%) | A | Length: 70 Width: 50 |

Length: 76.5/3.2 Width: 55.5/6.9 |

| B | Length: 77.8/2.8 Width: 54.6/4.1 |

||

| C | Length: 75.2/3.5 Width: 55.3/5.6 |

||

| D | Length: 75.5/3.1 Width: 55.1/4.8 |

||

| Number of warp threads per sample | A,B,C,D | Warp thread number in repeat 1920 + 78 threads for ends = 1998 threads (one color, white) | |

| Total number of warp threads | A,B,C,D | (1920 × 6 tape) + (39×2×6) threads for ends = 11988 threads (white) | |

| Total number of weft threads by color per sample | A | 1180 beige + 770 blue = 1950 | |

| B | 1950 dark blue | ||

| C | 240 blue + 500 red + 1210 white = 1950 | ||

| D | 155 red + 60 yellow + 1735 white = 1950 | ||

| Warp width in reed/fabric width (cm) | A,B,C,D | 62.7 × 6 tape = 389.7/352.8 | |

| Yarn twist number (u/1m) | A,B,C,D | Warp and weft: 325 | |

| Raw material composition | A,B,C,D | Warp and weft: 100% cotton | |

| Weave | A,B,C,D | Detailed illustration on Figure 2 | |

| Average deviation of samples (drawing/fabric) | A | Warpwise (by length) 9.3%; u smjeru potke (po širni): 11.0% | |

| B | Warpwise (by length) 9.9%; u smjeru potke (po širni): 9.2% | ||

| C | Warpwise (by length) 7.1%; u smjeru potke (po širni): 10.6% | ||

| D | Warpwise (by length) 7.1%; u smjeru potke (po širni): 10.2% | ||

CAD, computer aided design; CAM, computer-aided manufacturing; CV, variation coefficient.

Display of yarn thickness per strip, sample A: (a) beige weft strip and (b) blue weft strip.

Dimensions of fabric samples and dimension deviations on sample A: (a) dimensions of the fabric patterns and (b) deviations in dimensions overlapping: monitor - fabric patterns.

Weft distortion angle: (a) weft distortion display and deformation circular pattern and (b) fabric sample with circular patterns (sample B).

Deviation in the color shade by the fabric layers and weft distortion.

Weft distortion height (H/cm) per fabric width (L/cm).

3.1 Woven sample pattern deviations

Uneven width of the fabric strips, as well as changes in dimensions on the tested fabric patterns and their individual surfaces that depict individual effects, is not a big problem if fabrics are intended for table or linen woven fabrics. If the fabrics with defects are intended for garments (jackets, dresses, coats, blouses, etc.), then these faults will be noted at the joining points of the cutting parts, where the fit of the specimens is a necessity. However, for the aforementioned clothing items, multicolored and jacquard fabrics are preferred, and these problems are still present in the textile industry.

The shade variability along the fabric length, caused by unevenly dyed cross-wound yarn bobbins or warp beams, where the color shade is gradually changing over the length of the fabric, is not a big problem if the cutting parts are joined from the same layer. Joining of the cutting parts that are not from the same layer of fabric, this defect can occur (Figure 6). In addition, comparing the garments sewn from the upper, middle, and lower layers, it is very likely that the difference in color shades will occur.

Weft distortion is a common defect that can only be observed in multicolored and checkered woven fabrics. Weft distortion may have different shapes, and the most common is bow-shaped distortion extending over the fabric width (Figure 7). The highest distortion intensity of all samples is on the edges of the fabric while in the central part of the fabric weft maintains a relatively straight and at the 90° angle in relation to the warp.

Sample A with the transverse stripes has the slightest degree weft distortion, while the ample with the one color weft (dark blue) has the highest degree of weft distortion. Although fabric samples were made from the same warp, on the same weaving machine and in the same weave, there is a difference not only in the samples width and thread densities but also in the weft distortion amount. Since the samples differ only in terms of design, color, and color scheme, it can be argued that these parameters influence weft distortion degree.

For striped and checkered fabric with the distorted weft, intended for garments, it is not possible to match the lines at the joining places (Figure 6). This problem can be alleviated through the process of weaving and chemical finishing, in a cutting room by making a cutting plan with larger waste, and by carefully combining cutting parts from the same layer. Subsequent adjustment of distorted weft is possible in the chemical finishing processes by passing the fabric over the rollers of specific geometry. In places where the roll perimeter is larger, the fabric is more elongated as compared to the smaller one. Consequently, there may be a gradual increase in the distance between the lines at striped woven fabric leading to a new, sewing problem (Figure 6).

4 Conclusions

This research aimed to cover some irreparable defects in the manufacture of multicolored and checkered woven fabric. According to the analyses and the results obtained, the following could be concluded:

The increase of the stripes width in the direction of the weft is the result of different changes in the yarn thickness after dyeing. Yarn dyeing affects the change of yarn thickness or yarn volume.

Deviation of the sample size or part of the sample developed in the CAD system and deviation of the pattern on the woven fabric is caused by numerous parameters. The conditions of weaving cannot be maintained constant and depend primarily on the yarn tensile and other properties (color, fineness, yarn volume, and twist number), structural parameters of the fabric (density and weave), weaving conditions (weft distortion, warp, and weft tension). Geometry and size deviation within the pattern is due to the use of several different weaves in a single pattern, the position of the pattern in the fabric sample (greater deviations are on the marginal parts of the fabric) that leads to different shrinkage of the warp and weft threads and thus to the dimension changes.

Deviations in the color shade of the fabric sample on the monitor in comparison with the woven fabric sample is a major problem in the manufacture of multicolored and checkered fabrics. This is caused by the difficulty of adjusting the color by the effect of the sample on the monitor to the one on the fabric. Likewise, yarn dyeing on cross-wound bobbins or warp beams makes it hard to achieve the uniform color per layer. The inner layers of yarn on the cross-wound bobbin or warp may be lighter in shade than the+6 outer layers and the layers beside the cone or warp roller tube. If all cutting parts in a garment are separated from the same fabric layer, then this problem is less noticeable. The problem is greater if the cutting parts from different fabric layers are joined.

Many parameters related to material, processing and weaving conditions affect the weft distortion. Structural parameters of the fabric (weave, density), yarn properties (twist number and direction, tensile, and other properties), and weaving conditions (warp and weft tension, reed position, shafts, and shed height at the time of weft insertion), as well as the preparatory phases (warping type, hardness of the warp beam, and sizing) are some of the causes of the weft distortion phenomenon. The most common shape of weft distortion is the shape of the parabola or skew. The problematic consequence of weft distortion in the fabric is deformation of the pattern within the woven fabric, which makes it difficult to match the pattern when joining the cutting parts in a garment.

Funding

This work has been supported by Croatian Science Foundation under the projects lP-2018-01-3170 Multifunctional woven composites for thermal protective clothing.

References

[1] Ormerod, A., Sondhelm, W. S. (1998). Weaving: technology and operations, The Textile Institute.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Goerner, D. (1986). Woven structure and design. Part 2. Compound structures, Leeds: Wira Technology Group.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Istenič, S., Bizjak, M. (2016). Izdelava vzorca za zahtevne žakarske tkanine v bližnji preteklosti Creation of Design Pattern for Complex Jacquard Fabrics in the Recent Past, Tekstilec, 59(3), 244–249.10.14502/Tekstilec2016.59.244-249Search in Google Scholar

[4] Dimitrovski, K. (2007). Designing of complex jacquard fabrics in no time. In: Proceedings of XIth International, Textile and apparel symposium.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Šabarić, I., Brnada, S., Kovačević, S. (2010). Designer solutions of weft distortion in striped Fabrics. In: The 5th International Textile, Clothing & Design Conference, World of Textiles, Dubrovnik, Croatia.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Šomođi, Z., Kovačević, S., Dimitrovski, K. (2010). Fabric distortion after weaving - an approximate theoretical model. In: Book of Proceedings of the 5th International Textile, Clothing and Design Conference 2010 - Magic World of Textiles, Dubrovnik, Croatia.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Kadi, N., Karnoub, A. (2015). The effect of warp and weft variables on fabric’s shrinkage ratio. Journal Textile Science and Engineering, Published April 30, 2015 DOI: 10.4172/2165-8064.1000191.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Funder, A. (1983). Pomicanje kuta križanja osnovinih i potkinih niti u tkaninama. Tekstil, 32, 643–648,10.2116/bunsekikagaku.32.11_643Search in Google Scholar

[9] Gudlin Schwarz, I., Kovačević, S., Katović, D., Dimitrovski, K. (2013). Properties of yarns of different colors sized by standard and pre-wetting process. Fibres & Textiles in Eastern Europe, 5(101), 66–72.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Hahn, H. (1991). Vorausberechnung der Kett und Schußfadeneinarbeitung im entspannten Gewebe, Melliand Textilberichte, 73(4), 333–336.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Nosek, S. (1968). Dinamická setkatelnost tkanin, textil. Czech Republic, 13(8), 286–288.Search in Google Scholar

[12] Vangheluwe, L., Kiekens, P. (1992). Einfluß von Test- und Garnparametern auf die Relaxation und rückläufige Relaxation. Melliand Textilberichte, 73(2), 117–120.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Wulfhorst, B., Schneemelcher, S. (1990). Analyse der dynamischen Belastung von Schaftmaschinen. Textil Praxis International, 45(8), 831–838.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Weinsdörfer, H., Wasantha, W. (1987). Meß, Prüf- und Auswerteverfahren zur Beurteilung der Kettfadenbeanspruchung beim Weben. Melliand Textilberichte, 68(5), 327–332.Search in Google Scholar

[15] Wimalaweera, W., Weinsdörfer, H. (1987). Einfluß des Webgeschirrs auf den Webvorgang und die Garnbeanspruchung. Melliand Textilberichte, 68(10), 721–727.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Kovačević, S., Dimitrovski, K., Hađina, J. (2006). Procesi tkanja, Sveučilišni udžbenik. Tekstilno-tehnološki fakultet (Zagreb).Search in Google Scholar

© 2021 Stana Kovačević et al., published by Sciendo

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Investigation of Textile Heating Element in Simulated Wearing Conditions

- The Influence of Brand on Consumer Quality Assessment of Clothes: A Case Study of the Polish Market

- Limitations of the CAD-CAM System in the Process of Weaving

- Thermal Protective Performance of Firefighters’ Clothing Under Low-Intensity Radiation Heat Exposure

- The Eco-Modification of Textiles Using Enzymatic Pretreatment and New Organic UV Absorbers

- Development of Ergonomically Designed Functional Bra for Women with Hemiplegia

- Polish Textile and Apparel Industry: Global Supply Chain Management Perspective

- Yarn Damage Evaluation in the Flat Knitting Process

- Surface Characteristics of Seersucker Woven Fabrics

- Structural Damage Characteristics of a Layer-to-Layer 3-D Angle-Interlock Woven Composite Subjected to Drop-Weight Impact

- Changeover Process Assessment of Warp-Knitting Let-Off Equipped with Multispeed Electronic Let-Off System

- Thermal Analysis of Heating–Cooling Mat of Textile Incubator for Infants

- Kinematic Comparison of a Heald Frame Driven by A Rotary Dobby with A Cam-Slider, A Cam-Link and A Null Modulator

- Durability Assessment of Composite Structural Element Reinforced with Fabric due to Delamination

- Analysis of Basis Weight Uniformity Indexes for the Evaluation of Fiber Injection Molded Nonwoven Preforms

Articles in the same Issue

- Investigation of Textile Heating Element in Simulated Wearing Conditions

- The Influence of Brand on Consumer Quality Assessment of Clothes: A Case Study of the Polish Market

- Limitations of the CAD-CAM System in the Process of Weaving

- Thermal Protective Performance of Firefighters’ Clothing Under Low-Intensity Radiation Heat Exposure

- The Eco-Modification of Textiles Using Enzymatic Pretreatment and New Organic UV Absorbers

- Development of Ergonomically Designed Functional Bra for Women with Hemiplegia

- Polish Textile and Apparel Industry: Global Supply Chain Management Perspective

- Yarn Damage Evaluation in the Flat Knitting Process

- Surface Characteristics of Seersucker Woven Fabrics

- Structural Damage Characteristics of a Layer-to-Layer 3-D Angle-Interlock Woven Composite Subjected to Drop-Weight Impact

- Changeover Process Assessment of Warp-Knitting Let-Off Equipped with Multispeed Electronic Let-Off System

- Thermal Analysis of Heating–Cooling Mat of Textile Incubator for Infants

- Kinematic Comparison of a Heald Frame Driven by A Rotary Dobby with A Cam-Slider, A Cam-Link and A Null Modulator

- Durability Assessment of Composite Structural Element Reinforced with Fabric due to Delamination

- Analysis of Basis Weight Uniformity Indexes for the Evaluation of Fiber Injection Molded Nonwoven Preforms