Abstract

Chitin and keratin are naturally abundant biopolymers. They hold significant potential for sustainable applications due to their chemical structure, (nano)structural properties, biodegradability and nontoxicity. Chitin, a polysaccharide contained in exoskeletons of arthropods and the cell walls of fungi, forms strong hydrogen bonds that confer mechanical stability, which is ideal for use in protective structures and lightweight composites. Keratin, a fibrous protein found in vertebrate epithelial tissues such as wool, feathers and hair, is characterized by its high sulfur content and the formation of disulfide bonds, which provide both mechanical strength and flexibility. Utilizing chitin and keratin waste materials from the food industry, such as shrimp shells, chicken feathers and sheep wool, offers an eco-friendly alternative to synthetic materials and leverages their inherent biocompatibility. Additionally to the common macroscale reuse of chitin and keratin waste as fertilizer or livestock feed, using chitin and keratin as functional materials adds further uses for these versatile materials. The waste is increasingly being utilized specifically for its superior structural properties resulting from nanoscale functionalities. Chitin and keratin exhibit excellent thermal insulation properties, making them suitable for energy-efficient building materials. Their structural colours (e.g., in butterflies and birds), arising from micro- and nanoscale arrangements, offer non-fading colouration for textiles and coatings without the need for potentially harmful dyes. Additionally, these biopolymers provide lightweight yet strong materials ideal for packaging, consumer products, and – when smartly structured – even passive radiative cooling applications. Biomimetic designs based on chitin and keratin promise advancements across multiple fields by harnessing their natural properties and converting waste into high-value products, thereby addressing recycling issues and promoting sustainability.

1 Introduction

Chitin and keratin are ubiquitous materials in organisms. Chitin is a structural polysaccharide constructed from chains of modified glucose. It is found in single-celled organisms such as certain diatoms 1 and yeasts 2 and in fungal cell walls, 3 insects, 4 spiders 5 and crustaceans 6 as well as in molluscs 4 and (less commonly) some other invertebrates such as annelids, nematodes, bryozoans and cnidarians. 7 Keratin is a fibrous protein produced in the epithelial tissues of various vertebrates. Keratin is contained in wool, hair, feathers, hooves, horns, claws, beaks and skin. 8 , 9

The functionality of keratin and chitin in biological systems arises from the synergy between their unique chemical compositions and nanoscale to macroscale hierarchical structuring. The biomimetic translation of this structuring enhances material properties such as strength, flexibility, and durability. Additionally, the localized availability of resources for the biosynthesis of keratin and chitin underscores their sustainability and recyclability, highlighting their potential as eco-friendly materials for innovative applications in material science. 10 , 11 , 12

Chemically, keratin is distinguished by its high sulfur content due to the abundance of cysteine amino acids, which form disulfide bonds. 13 These bonds are crucial for mechanical stability and flexibility. 14 , 15 Chitin can form strong hydrogen bonds between adjacent chains. 16 These hydrogen bonds enhance its structural stability, which is crucial, for example, the protective exoskeletons of insects and crustaceans and the cell walls of fungi. 17 , 18

The structural arrangement of chitin and keratin on the micro- and nanometer length scales contributes to more than just mechanical strength: the hierarchical structuring of chitin in butterfly wing scales and of keratin in the feathers of birds such as hummingbirds, pigeons and peacocks, for example, interacts with light through complex photonic structures, resulting in brilliant colours (without the use of pigments). 19

Organism-inspired structural functionalities are primarily translated into technology through the use of highly engineered materials, 20 , 21 such as structural colours inspired by butterfly wings, achieved using metal oxides and volatile solvent-based systems. 22 , 23 Alternatively, structure-based functionalities can be implemented using chitin and keratin waste such as shrimp shells or sheep wool. 24 This alternative offers clear advantages: it utilises renewable, non-toxic, biodegradable, and recyclable materials. 25 The functional properties intrinsic to chitin and keratin are directly transferred to biomimetic applications, preserving the natural base materials without modification.

Incorporating biomimetic principles into material design requires synergising chemistry-based functionalities and structure-based characteristics on various length scales, reflecting the multi-scale strategies observed in natural systems (integration instead of additive manufacturing 26 ). This combined approach enhances material performance and sustainability, demonstrating that chemistry and structural design are most effective when applied together rather than in isolation.

2 Chitin and keratin in organisms and related biomimetics

Keratin is widespread across various classes of animals, including mammals, birds, and reptiles. It is a significant component of humans’ hair, skin, nails, and cornea. Human hair is composed of approximately 80 % hard keratins, 27 though its concentration varies based on location and function within the body. In other mammals, keratin forms the structure of horns, hooves, and claws, while in birds, it is present in feathers and beaks. 28 Reptiles have keratin in their scales and claws. 29

Chitin is a crucial structural component in the exoskeletons of various arthropods, including insects, spiders, and crustaceans such as crabs and lobsters. 30 , 31 It is also present in the cell walls of certain fungi 32 and contributes to the radula – a feeding structure – in some molluscs. Chitin content varies significantly across organisms: squid, cuttlefish, and octopuses contain between 6 % and 40 % chitin, 11 , 33 , 34 , 35 while the exoskeleton of insects can incorporate up to 40 %. 36 Specific insect chitin content ranges from 18.4 % in cockroaches (Blattella sp.) to 64 % in butterflies (Pieris sp.). 37 In crustaceans, chitin typically constitutes 20–30 % of the exoskeleton, 38 ranging from 17.8 % in shrimp (Crangon crangon) to 75 % in lobster (Homarus sp.). 39 Fungal species such as Aspergillus niger (black mould) can contain chitin levels between 2.3 % and 42 %. 39 The determination of chitin content across different organisms varies depending on the species and the specific composition under different conditions. 37

Keratin and chitin are structural biopolymers known for their durability and resistance to environmental degradation. 40 , 41 Keratin protects against mechanical wear and tear, forming intermediate filaments within cells that reinforce tissues such as skin, hair and nails, shielding tissues from physical and chemical damage. 42 , 43 Chitin resists microbial degradation, forming long chains that enhance the strength and rigidity of exoskeletons and cell walls, fortifying exoskeletons and cell walls and offering structural defence for organisms. 44 , 45

3 Waste management and sustainable utilization of keratin

Much keratin-rich waste originates from the food industry, particularly slaughterhouses, meat markets, and the wool industry. 28 This waste comprises keratin-containing animal by-products, such as wool, hair, hooves, and feathers. Only a few microorganisms, such as keratinophilic microflora (bacteria and fungi), can break down keratin proteins. 46 , 47 Biological degradation of keratin waste is considered more efficient than physical and chemical methods. 48 Organic and biodegradable keratin waste can be repurposed as a sustainable resource via chemical and mechanical processing, transforming it into valuable biomaterials. 49 , 50 Keratin derived from biomass offers an eco-friendly alternative that is naturally free from synthetic chemicals and thus reduces environmental impact. 51

3.1 Keratin-enriched waste

Poultry slaughterhouses generate substantial feather waste, as only 60–70 % of poultry parts are deemed suitable for human consumption. 52 Keratinous by-products comprise roughly 15–20 % of slaughterhouse waste, with feathers accounting for 7–9 %. 53 Feather waste is challenging for livestock to digest due to its keratin content, necessitating various pre-treatment methods – physical, chemical, or biological – for effective utilization. 54 While some feather waste is processed into feather fodder for animal feed or fertilizer, the majority is discarded via landfill disposal or incineration, contributing to pollution concerns. The environmental impact of these disposal methods underscores the need to increase feather recycling. Feathers comprise approximately 91 % β-keratin, a highly sought-after resource. 55 , 56 , 57 Keratin extracted from organic waste is a sustainable toxin-free resource. 51

Wool is a historically significant natural fibre which has long played a crucial role in global trade and agricultural economies. 58 , 59 Wool’s fibrous structure is composed of approximately 95 % keratin by weight, with a cysteine content between 11 % and 17 %, and highly resistant to degradation in common solvents. This resilience is attributed to the tightly packed α-helix and β-sheet in keratin. 58 , 60 Wool’s market share faces increasing competition from synthetic fibres as consumer preference shifts toward lighter-weight products. 61 Environmental concerns, such as the water and resource intensity of wool production and pollution associated with processing, have also contributed to declining demand, confining wool use primarily to luxury goods. 62

Market statistics typically account only for wool that enters the manufacturing chain and is processed into various products, overlooking raw wool produced on farms that remains unused, often due to low quality unsuitable for textiles. 63 In recent years, sheep shearing has sometimes been performed solely for animal welfare, offering no profit to farmers, with the resultant wool shifting from a valuable product to a waste management challenge. 64 The accumulation of wool waste has become a significant issue in waste management, underscoring the need for sustainable options. 58 , 65

In addition to wool, other keratin-rich waste by-products include human hair, animal hair, and hooves from various sources, such as cattle, horses, oxen and pigs (260 million pigs were slaughtered in the EU in 2016 66 ). 55

Keratin extraction employs various methods, including oxidation, 67 reduction, 68 sulfitolysis 69 and superheated hydrolysis. 70 , 71 Each technique targets the cleavage of cystine disulfide bonds within the keratin structure, yielding low molecular weight proteins and peptides. 72 The resulting keratin extracts are typically characterized through molecular weight analysis and amino acid profiling to evaluate their composition and functionality. The choice of extraction method is highly dependent on the starting material, such as hooves, feathers, or wool, each possessing distinct structural and chemical properties. These differences necessitate tailored adjustments to optimize the extracted keratin’s yield and quality. 55

4 Waste management and sustainable utilization of chitin

With population growth, 73 waste generation has risen significantly, 12 particularly from food production, 74 where valuable by-products are discarded. 75 For instance, seafood waste is often incinerated, landfilled, discarded at sea, or left to decompose, which poses risks to human health and biodiversity and causes environmental problems. 76 Chitin and chitosan (derived from chitin) possess high economic value due to their versatile biological properties. 77

The seafood processing industry generates substantial waste, including shells and exoskeletons that are slow to biodegrade due to their high structural components. 78 Disposing seafood waste in marine environments contributes to coastal pollution by affecting water quality and marine ecosystems. 79 Accumulated organic waste can lead to nutrient overload, fostering algal blooms and depleting oxygen levels, which harm local biodiversity. 80

Seafood by-products (waste) can be utilized as valuable raw materials for chitosan and chitin production. 81 Chitosan’s excellent adsorption capabilities make it suitable for removing heavy metals and dyes from wastewater. 82 , 83 Edible chitosan-based films extend the shelf life of perishable products as a barrier against moisture and microbial contamination. 84 , 85 Crustacean exoskeletons are the primary source of chitin for commercial use due to their high chitin content and wide availability. 86

Chitin nanomaterials can be extracted in the form of chitin nanocrystals or chitin nanofibers, each exhibiting unique structural and functional properties. 87

The cyclic use and reuse of chitin and chitosan can be effectively achieved through large-scale fermentation processes, leveraging their biodegradability and renewability. This approach enables the sustainable production of value-added products, minimizes waste, and supports circular bioeconomy frameworks by integrating microbial fermentation for efficient biopolymer recovery and transformation. 88

4.1 Chitin-enriched waste

The shrimp industry is a substantial source of chitin waste worldwide, driven by high global shrimp consumption. 89 In 2023, shrimp production reached 5.6 million tons globally, 90 with projections indicating an increase to 7.28 million tons by 2025, reflecting a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 6.1 % from 2020 to 2025. 91 Asian countries collectively contributed over 80 % of global shrimp production in 2023. 92

The shrimp processing stage, particularly peeling and deveining, generates considerable chitin waste, primarily from the shells, with 45–48 % of raw shrimp material by weight discarded as waste. 93

Shrimp waste is a valuable source of animal protein and essential biomaterials, including chitin, lipids (e.g., glycerides, phospholipids, carotenoids), and calcium carbonate. Studies indicate that dried shrimp waste contains approximately 18 % chitin, 43 % protein, 29 % ash, and 10 % fat. 94 In addition, shrimp waste harbours bioactive compounds such as unsaturated fatty acids, carotenoid pigments, free amino acids, and trace elements. 95 Efficient recovery of these components presents substantial industrial, environmental and research opportunities. 96

Beyond shrimp shell waste, insect-derived chitin is an emerging source of this versatile biopolymer, with insects containing 5 %–10 % chitin (dry weight). 97 , 98 Chitin is readily separable from the protein-rich parts of insects, such as their bodies, larvae, or exoskeletons. During various life stages (e.g., larvae, pupae, prepupae, adults), insects shed exoskeletons, providing a chitin-rich substrate for extraction. 36 , 99 Although chitin from shrimp, crabs, squid pens, and mushrooms has been widely studied, the production and comparative analysis of chitin nanofibers (ChNFs) from different insect sources is an emerging research field. 100

While insect and crustacean chitin share similar chemical structures, crystalline arrangements, and thermal properties, they vary in morphology and fibre accessibility, which affects extraction efficiency. 36 , 101 The extraction processes must be tailored to the source; crustacean shells contain predominantly calcium carbonate, whereas insect exoskeletons have a higher protein and lipid content, requiring adjusted demineralization and deproteinization steps. 102 Fungal chitin sources have glucan residues on their fibre surface, which is challenging to purify. 103

Chemical chitosan extraction is a multi-step process comprising demineralization, deproteinization, and deacetylation. 104 , 105 , 106 Demineralization typically employs a dilute hydrochloric acid (HCl) solution to dissolve calcium carbonate and calcium chloride, the predominant inorganic components in the exoskeletons of crustaceans. 107 Deproteinization follows, where an alkaline treatment is applied to eliminate proteins, resulting in purified chitin. The final step, deacetylation, transforms chitin into chitosan by removing acetyl groups. Apart from the chemical extraction of chitin and chitosan, there is a biological alternative method. 36 , 108 Biological methods offer an environmentally friendly alternative by utilizing lactic acid for demineralization and proteases secreted into the fermentation medium for deproteinization. 33 , 37 , 107

5 Chemical properties of chitin and keratin

The structural polymers chitin and keratin fulfil distinct functions due to their unique chemical compositions and structural configurations. 109 , 110 Despite differences in their molecular makeup, both serve essential structural roles, exhibit fibrous properties, and provide protective functions. Chitin is a polysaccharide consisting of long chains of N-acetylglucosamine, a glucose derivative, which lends rigidity to the exoskeletons and cell walls in various organisms. 11 , 111 In contrast, keratin is a sulfur-containing protein rich in the amino acid cysteine. It forms disulfide bonds that enhance its strength and resilience, making it ideal for protective tissues like hair, nails, and feathers. 13 , 72

5.1 Chemistry of keratin

The amino acid sequence forms alpha-helices and beta-sheets, which assemble into intermediate filaments within cells, contributing to the tissue’s mechanical stability and resilience. 42 Keratins are particularly abundant in the outer layers of the skin and protective structures. 112 Their high cysteine content allows for disulfide bonds, giving keratin durability and resistance to environmental stresses. 113

Unlike specific biological tissues, the keratin-based matrix lacks the capacity for self-repair, as it primarily comprises non-living tissue formed by keratinocytes (keratin-producing cells) that die and accumulate in the outermost layers. This structural framework provides resilience and protection but remains incapable of regenerating in the same manner as bone or other living tissues. 42 , 114 , 115

5.1.1 Primary structure

At the molecular level, keratin exists in two main types – alpha-keratin and β-keratin – which are distinguished by their amino acid composition and structural organization. α-keratin is primarily found in mammals, with some exceptions like the pangolin, which has α- and β-keratin. In contrast, β-keratin is characteristic of birds and reptiles. 116 , 117 , 118 , 119 Each type has distinct atomic-scale and sub-nanoscale structures (Figure 1). 8 , 120

The hierarchical structure of α-keratin and β-keratin spans multiple scales, from the amino acid sequence forming alpha-helices and beta-sheets to protofilaments and intermediate filaments. These intermediate filaments further organize into larger macroscopic structures, demonstrating higher-order arrangement and functionality. This multi-scale architecture underpins the remarkable mechanical and biological properties of keratin-based materials. Source: 8 licensed under CC BY.

In α-keratin, the structure is divided into three regions: crystalline fibrils (helices), the matrix, and the terminal domains of the filaments. 116 Its α-helical shape arises from internal hydrogen bonds, which coil the chain. 121 The α-helical chains are stabilized by sulfur-based cross-links, forming dimers that further assemble into protofilaments. 117 , 122 These protofilaments feature N- and C-terminal ends rich in cysteine, essential for bonding with other intermediate filament (IF) molecules, thus creating a robust and organized network. 123 α-keratin itself is divided into type I (acidic) and type II (basic) categories, further classified into hard keratin (5 % sulfur content) and soft keratin (1 % sulfur content) based on structural properties. 124 , 125 Hard keratin – found in hair, feathers, horns, claws, hooves, and exoskeletons – is sub-classified into Ia (acidic-hard) and IIa (basic-hard), while soft keratin – found in cellular tissue like calluses – is categorized as Ib (acidic-soft) and IIb (basic-soft). 117 , 126 The molecular mass of α-keratin ranges from approximately 40 kDa–68 kDa, 127 with a notable cysteine content (7–20 %), essential for forming disulfide linkages that provide mechanical strength and durability. 128

In contrast, β-keratin has a different molecular structure, featuring a central domain with β-sheet residues flanked by N- and C-terminal regions. 129 In β-keratin, the β-strands align antiparallelly, stabilized by hydrogen bonds that create a stable, planar, and pleated sheet structure. 130 The beta sheets form a rigid, planar surface due to this arrangement. Both filament and matrix regions integrate within a single protein structure, resulting in a comparatively smaller molecular mass, ranging between 10 kDa and 22 kDa. 127

These structural distinctions between α- and β-keratin – particularly in cysteine content, molecular mass, and bonding types – underlie their differing mechanical properties and functional roles across species.

5.1.2 Secondary structure

The two main regular secondary protein structures, α-helices and β-sheets, are crucial internal support frameworks within extended polypeptide chains and serve as critical classifications for keratins. Both α- and β-keratins exhibit a distinctive filament-matrix architecture at the nanoscale (Figure 1). 116 , 131

α-Keratin proteins organize into a coiled-coil structure, where α-helices wind around each other to form superhelical bundles. 117 , 132 These bundles typically consist of two or three helices in parallel or antiparallel orientation, although bundles with up to seven helices have been observed. 133 The right-handed helices are stabilized by interchain hydrogen bonds, resulting in a twisted helical structure. In α-keratins, the term ‘filament’ refers to intermediate filaments (IFs) visible under transmission electron microscopy, with a diameter of approximately 7–10 nm. 134 The spacing between the α-helical axes within these structures measures 0.98 nm. 117 , 135

In β-keratin, the ‘filament’ – often termed the ‘β-keratin filament’ – is about 3–4 nm’ in diameter and is organized into a pleated-sheet structure. 136 This structure is stabilized by hydrogen bonds between β-strands, as well as the planarity of the peptide bond, resulting in a robust, planar sheet. 137 The sheet is formed as a single polypeptide chain that folds into four parallel and antiparallel strands, maintained by intermolecular hydrogen bonds, with an inter-sheet spacing of approximately 0.97 nm. 130

5.1.3 Hierarchical structures

Hair and wool fibres serve as exemplary models to illustrate keratin’s hierarchical structure. As shown in Figure 2, this structure comprises several distinct layers. 138 The outermost layer, the cuticle, which constitutes approximately 10 % of the fibre’s volume, consists of overlapping cells that secure the hair within the follicle by firmly attaching it to the root shaft. 115 Each scale cell in the cuticle comprises three sub-layers: the epicuticle, the exocuticle, and the endocuticle. The arrangement and morphology of these cuticle cells influence the frictional properties of hair. In human hair (Figure 3), the cuticle typically has five to ten layers of scales, while wool fibres usually consist of only one to two layers. 139 Generally, fibres with greater diameters have multiple layers of cuticle cells, and the thickness of individual cuticle cells varies, measuring around 0.3 µm in Merino wool, 0.5–0.66 µm in Lincoln wool, and approximately 0.33 µm in human hair. 140 , 141

The hierarchical structure of human hair spans scales from nanometers to micrometres, beginning with alpha-helices and intermediate filaments (as detailed in Figure 1) and extending to microfibrils, cortical cells, and the entire hair fibre. This layered organization, ranging from ∼2 nm to over 100 μm, highlights the complexity of keratin’s architecture and its role in imparting strength, flexibility, and functionality to hair. Source: 142 permission granted.

The chemical structures of chitin and chitosan. Chitosan is obtained through partial deacetylation of chitin in the solid state under alkaline conditions or via enzymatic hydrolysis catalyzed by chitin deacetylase. This structural difference imparts distinct solubility and functionality, enabling diverse biological and industrial applications. 150 Source: 174 licensed under CC BY.

The cortex layer, constituting roughly 90 % of the fibre’s mass, 115 comprises three distinct zones: the orthocortex, paracortex, and mesocortex, each characterized by unique structural arrangements that influence the fibre’s curliness. 143 The paracortex’s Intermediate Filaments (IFs) display a more uniform hexagonal arrangement. In contrast, the IFs in the orthocortex form discrete bundles and are surrounded by a smaller matrix volume than in the paracortex. 42 , 144 The paracortex also has a smaller diameter than the orthocortex. The lipid-rich cell membrane complex provides cohesion among cortical cells, with microfibrils (formed from IFs) and matrix proteins visible within. 145

At the nanoscale, alpha-helical chains assemble to form IFs embedded in a sulfur-rich matrix containing proteins, nuclear remnants, cell membrane complexes, and intercellular cement. 116 , 146 , 147 The medulla, a central porous layer comprising foamy keratin, shows notable variation among fibre types. Fine fibres, such as Merino wool and polar bear fur, typically lack a medulla (a hollow core), enhancing their thermal insulation properties. 8 , 115 , 148

5.2 Chemistry of chitin and chitosan

Chitin, or poly (β-(1 → 4)-N-acetyl-D-glucosamine), is the second most abundant natural polysaccharide after cellulose and is integral to various organisms. 149 , 150 , 151 Chitin provides structural integrity in single-celled organisms, such as diatoms, protists (eukaryotic microorganisms), and fungal cell walls. In multicellular organisms, it is found in sponges, corals, molluscs, worms, and notably in the exoskeletons of arthropods. 152 The crystalline structure of chitin varies by source, resulting in three distinct polymorphic forms: α-chitin, β-chitin and γ-chitin. These forms differ primarily in the stacking arrangement of chitin chains. In α-chitin, the chains are arranged in an alternating antiparallel orientation, contributing to its rigidity, while in β-chitin, all chains align in a parallel arrangement, which offers greater flexibility. 153 The third form, γ-chitin, is a structural variant of the α-family, exhibiting a combination of parallel and antiparallel stack configurations. 154

5.2.1 α-chitin

α-chitin is the predominant polysaccharide in krill, lobster and crab shells, yeast cell walls, shrimp shells, and insect cuticles. Its crystalline structure is highly organized with a space group symmetry designated as P212121, an orthorhombic crystal system. 155 Here, “P” signifies a primitive cell with a single lattice point per unit cell, while 21 represents a two-fold rotational axis, of which three are in this arrangement. 156 This orthorhombic structure is characterized by a symmetry group of 222 and demonstrates high crystallinity, observed in X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns. XRD reveals a hallmark diffraction ring for α-chitin at approximately 0.338 nm alongside an inner ring at 0.943 nm, both stable even in hydrated conditions, reflecting chitin chains’ dense, ordered packing.

Electron diffraction further elucidates α-chitin’s structural parameters, with cell dimensions nearly twice those of β-chitin in one axis. Detailed crystallographic analysis shows that α-chitin’s unit cell accommodates two antiparallel chitin chains per unit, aligned in sheets and bonded by intra-sheet solid hydrogen interactions, such as C=O⋯NH. These interactions form a cohesive network that significantly enhances the material’s mechanical stability and rigidity. 150 , 155

At the molecular level, α-chitin consists of long chains of N-acetylglucosamine units linked via β-(1 → 4) glycosidic bonds. 149 The N-acetyl glycosyl moiety is the independent crystallographic unit in α- and β-chitin, serving as a recurring structural element. 157 Regarding its interaction with solvents, α-chitin exhibits selective swelling behaviour; water and alcohol cannot penetrate its crystalline lattice. However, aliphatic diamines, acting as potent swelling agents, can intercalate within the lattice, creating highly crystalline complexes. These agents fit between the chitin sheets, causing directional expansion. Interestingly, this inter-sheet swelling correlates with the number of carbon atoms in the diamine, while the chitin structure’s original crystallinity is restored upon acid removal. 150 , 158 , 159 This selective swelling behaviour highlights the material’s unique capacity for guest-molecule intercalation, with implications for various applications.

5.2.2 β-chitin

β-chitin is relatively rare, found in specific marine and deep-sea biological structures such as squid pens, diatom spines, and the tubes of certain deep-sea worms, including pogonophores and vestimentiferans, typically at depths of 1,000–10,000 m. 160 , 161 Although β-chitin also occurs in a few other organisms, it is significantly less prevalent than α-chitin. 162 Structurally, β-chitin differs subtly but distinctly from α-chitin, particularly in its crystallographic and hydration properties. 163 , 164 The characteristic diffraction ring of β-chitin appears at 0.324 nm, similar to that of α-chitin. However, upon hydration, this ring expands to approximately 1.16 nm, indicating a substantial increase of 0.242 nm compared to α-chitin, highlighting its unique response to moisture. 150

β-chitin’s crystalline structure consists of a single chitin molecule per unit cell, arranged in parallel chains within stacked sheets. These sheets are stabilized primarily by intra-sheet hydrogen bonds, which confer structural cohesion but lack significant inter-sheet hydrogen bonding along one crystallographic axis. Consequently, β-chitin exhibits pronounced intercrystalline swelling when exposed to water, alcohol, or amines, with these molecules able to penetrate its crystal lattice without disrupting overall crystallinity. 165 , 166 This intra-crystalline swelling is reversible; however, exposure to solid acids induces an irreversible conversion of β-chitin to α-chitin. 167 This transformation involves breaking intra- and inter-sheet hydrogen bonds, resulting in a loss of crystallinity and significant shrinkage. This irreversible β-to-α transition suggests the superior thermodynamic stability of α-chitin, which recrystallizes into a more energetically favoured arrangement. 155

5.2.3 Chitosan

Chitosan is a non-toxic, linear polysaccharide and the primary derivative of chitin, comprising randomly distributed N-acetylglucosamine and glucosamine units. 168 It is obtained through partial deacetylation of chitin in the solid state under alkaline conditions or via enzymatic hydrolysis catalyzed by chitin deacetylase. 169 Chitosan is predominantly sourced from crustaceans, especially squid pens. 170 In its solid form, it has a semi-crystalline structure. Electron diffraction analysis shows an orthorhombic unit cell with space group (P212121), containing two antiparallel chitosan chains without intercalated water molecules. 171 The molecular weight of chitosan ranges from 10,000 to 1 million Daltons, 172 and its structure includes an amino group and two hydroxyl groups, which form a network of intermolecular hydrogen bonds that contribute significantly to its stability. 173

6 Biomimetics using chitin and chitosan

Biomimetics, bio-inspiration, and bio-utilization are distinct yet interconnected concepts, as systematically defined by Drack and Gebeshuber. 175 This work proposes an integrative approach that merges these methodologies to optimize biopolymers such as chitin, keratin, and chitosan, effectively bridging biomimetic principles with bio-inspired innovations. This approach becomes particularly compelling when these materials are sourced through recycling. Recycling facilitates sustainable material recovery while maintaining their intrinsic functional properties.

Chitin is a highly versatile biopolymer found in marine organisms and insects, offering significant potential across various applications, from biomedicine to materials science. Both chitin and its derivative, chitosan, exhibit notable biological activities, including antitumor, antimicrobial, and antioxidant properties, primarily influenced by their unique chemical compositions and structural configurations. 150 , 174 , 176 A detailed examination of chitin’s hierarchical structure provides critical insights into its mechanical properties and informs the development of advanced materials. Understanding these properties supports innovations in protective armour and structural materials inspired by chitin’s role in providing strength and resilience to various biological organisms. 177

The list of properties presented is intentionally selective and not comprehensive, focusing on the most notable characteristics of chitin and chitosan that are particularly pertinent for biomimetic applications without claiming to provide a conclusive inventory of their potential attributes.

6.1 Mechanical properties

Chitin’s unique chemistry and hierarchical structure confer remarkable mechanical properties, which can be further enhanced through polymorphic forms, specifically α- and β-chitin crystals, that provide additional structural strength. 178 These polymorphs introduce distinct molecular arrangements and bonding patterns contributing to increased rigidity and resilience. 177

6.1.1 Tensile strength

Uniaxial tension simulations were conducted to investigate α- and β-chitin crystal’s tensile properties along the [001] direction, chosen due to the more muscular backbone strength of carbohydrate chains compared to the weaker non-bonded interchain interactions. The results indicated that both chitin polymorphs exhibited linear elasticity at minor strains, with α-chitin showing an elastic modulus nearly twice that of β-chitin. 179 , 177 Under increasing strain, both forms displayed nonlinear elasticity preceding failure, with α-chitin uniquely featuring a yielding plateau absent in β-chitin. Throughout loading, α-chitin sustained higher stress up to yielding. 180 However, post-yield, the stress-strain curves of both polymorphs converged, ultimately showing equivalent tensile strength and critical fracture strain at failure. 181 , 182 The work of fracture and effective modulus of α-chitin exceeded those of β-chitin, underscoring its superior resistance to deformation. At the atomic scale, failure in both polymorphs originated from the β-(1 → 4) linkages within chitin backbone chains. However, α-chitin underwent a structural transformation under substantial tension, leading to yielding, whereas β-chitin maintained its crystalline structure until the backbone ruptured. 177 , 183 , 184 Despite their comparable ultimate tensile strength and fracture strain, these observations clarify α- and β-chitin’s differing failure modes and deformation mechanisms under tensile load. 177

Chitosan, derived from shrimp shells, is an environmentally friendly, biodegradable, and antibacterial polysaccharide with a chemical structure similar to cellulose, allowing for easy integration with cellulose-based surfaces, such as hand sheets. Researchers examined the influence of chitosan on mechanical properties by incorporating shrimp-derived chitosan into cellulose hand sheets at 0.25 %–0.50 % of the oven-dry pulp weight. 185 The tensile index, indicating sheet resistance to breaking under tension, increased significantly with chitosan addition, suggesting enhanced tear resistance. 186 , 187 The modulus of elasticity, reflecting the sheet’s capacity to recover its shape post-deformation, also improved markedly, implying increased elasticity and deformation tolerance. The enhancement of tensile strength and elasticity demonstrates chitosan’s potential to improve cellulose-based sheet performance for various applications, contributing to durability and flexibility. 188 , 189 , 190

6.1.2 Wear resistance

The anti-wear performance of chitin crystals is crucial for the protective armour in crustaceans and beetles, which safeguards softer tissues from environmental abrasions. These biological structures must effectively counteract surface scratches and material degradation over time, which may otherwise compromise their protective function. 191 , 192 When subjected to forces at steep attack angles, these surfaces consistently exhibit a characteristic wear pattern known as “cutting mode,” marked by scratch grooves and material debris accumulation. 191

To assess the anti-scratch performance of chitin, a minimum applied force, denoted Fcut, is required to initiate surface scratching. Higher Fcut values correlate with improved wear resistance. 192 Factors influencing Fcut include shear strength, attack angle, penetration depth, and surface energy, particularly on the [010] chitin surface. Surface energy represents the energy required to create a new surface area, which can be determined by evaluating changes in total potential energy when a chitin crystal is split. 192 Comparative analyses of Fcut for α- and β-chitin crystals reveal that α-chitin demonstrates superior wear resistance across various conditions. This superior performance aligns with the frequent occurrence of α-chitin in natural protective structures, suggesting a potential relationship between wear resistance and crystal polymorphism. 177

6.2 Bactericidal properties

The antibacterial chemical properties of chitin, chitosan, and their derivatives have garnered significant attention in research. The antibacterial activity against various pathogens makes them potential candidates for various antimicrobial applications. 193 , 194 Chitosan is recognized for its broad-spectrum antimicrobial properties, which offer significant advantages over conventional disinfectants, including a faster action rate, enhanced effectiveness, and lower mammalian cell toxicity. 195 While the precise mechanisms behind chitosan’s antimicrobial properties are still under investigation, it is widely believed that chitosan’s positively charged polysaccharide interacts with the negatively charged bacterial cell membrane, resulting in increased cell permeability. 196 , 197 , 198

The antibacterial effects of chitosan are proposed to involve several mechanisms. Low molecular weight (MW) chitosan can penetrate bacterial cell walls and inhibit essential processes, such as mRNA and DNA synthesis, especially in gram-positive bacteria. In contrast, high-MW chitosan is thought to act primarily at the cell surface, altering its permeability or forming a barrier that restricts the influx of essential solutes. 196 , 199 Chitosan’s antibacterial efficacy is also affected by environmental pH, with acidic conditions enhancing its adsorption onto bacterial cells due to increased positive ionic charge. 174 , 198 , 200 At pH 6, chitosan’s higher solubility further enhances its antibacterial action compared to chitin. 193

Other factors impacting chitosan’s antimicrobial activity include its degree of acetylation (DA) and molecular weight. 198 , 201 Lower DA and MW, combined with acidic pH, have been shown to enhance antibacterial effectiveness Salah et al., 202 Yun, Kim, and Lee, 203 Liu et al. 204 Chitosan also exhibits differential effects on gram-positive versus gram-negative bacteria, 174 , 205 increasing activity against gram-positive bacteria with MW. In contrast, the opposite trend is observed with gram-negative bacteria. It remains unclear, however, whether chitosan’s action is bacteriostatic (inhibiting growth) or bactericidal (inducing cell death). 193

In addition to antibacterial effects, chitosan has antifungal activity, effectively inhibiting fungal species by forming a permeable film at the cell interface and activating plant defence mechanisms. 206 Its antifungal efficiency varies with properties such as MW and DA. 207 Numerous modifications to chitosan have been developed to enhance solubility and antimicrobial effectiveness, introducing functional groups along polymeric chains. 208 Common modifications include N-modification, O-modification, and combined N–O-modification, with approaches such as quaternization, carboxymethylation, and sulfonation, significantly improving solubility and antimicrobial potential. 193

Heedy et al. explored the synergistic antimicrobial effects of chitosan nanostructures, 209 revealing that a chitosan hydrogel with nanopillars showed enhanced antimicrobial properties, markedly inhibiting the growth of the gram-negative bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa and the fungus Fusarium oxysporum. Chitosan based nanostructures avoid unwanted toxic chemicals and harsh fabrication processes. 210 Surfaces with nanopillar topographies inspired by cicada wings, 194 butterfly wings, 211 and shark skin 212 exhibit antimicrobial properties. These materials act antimicrobially due to the nanopillars deforming bacterial membranes, causing oxidative stress and rupturing. 213

Natural polymer hydrogels have gained increasing attention compared to synthetic polymer hydrogels due to their low toxicity, excellent biocompatibility, ease of degradation, abundant availability, and lower cost. 214 Hydrogels made from chitin and chitosan can be tailored through various modifications to serve as scaffolds for ideal wound dressings or as “intelligent” hydrogels for controlled and targeted drug release. 215 , 216 , 217 These hydrogels have been found to exhibit self-healing properties. 218 Keratin-based hydrogels exhibit valuable properties for wound healing, drug release, and neural regeneration. 219 , 220

6.3 Structural colour

Chitin exhibits various structural conformations shaped by natural processes such as biopolymerization, crystallization, and non-equilibrium self-assembly. 178 These processes produce unique physical effects, including intricate light scattering, polarization, and mechanical properties, driven by the balance between highly structured chain conformations within nanofibrils and disordered regions. 178 Colours play essential roles in Nature for communication, defence, signalling, and environmental adaptation, including camouflage. 221 , 222 , 223 , 224 Unlike pigments that selectively absorb light due to electron delocalization within specific molecules, structural colouration arises from scattering, interference, and diffraction at the nanoscale, with structures on the order of the wavelength of visible light. 19

Chitin serves as the primary structural component in the exoskeletons of various species, providing both robustness and an adaptable colour palette. 120 , 178 , 225 , 226 Recent studies have focused on understanding how butterfly wing-scale nanostructures influence light reflection at different angles. For instance, butterflies with structural colours, such as Papilio memnon and Parides sesostris, utilize grating structures with ridges and cross-ribs, producing strong orientation-dependent reflection when ridges are perpendicular to incident light. 227 This orientation-based reflectance produces varied appearances based on viewing angle, which can be replicated in synthetic materials for technological applications. 228

A notable example of chitin’s optical properties is the blue colour of the Morpho butterfly (Morpho peleides see Figure 4), which displays a vibrant metallic-blue hue due to coherent scattering from layered nano- and microscale structures. Unlike conventional multilayers, Morpho butterflies have tilted, Christmas tree-like multilayered surfaces that generate a metallic blue with minimal angle dependence. 231 This unique colour is produced by periodic surface nanostructures that cause diffraction from additional grooves, with organized chitin fibres in the cuticle contributing to birefringence due to their polymer orientation. Refractive indices between 1.54 and 1.62 and air-filled nanostructures enhance Morpho’s brilliant, angle-independent colour. 232 , 233

Nanostructures are responsible for structural colouration in various insects. These features demonstrate how nanoscale architecture, rather than pigments, produces vibrant colours through interference, diffraction, and selective light reflection. (a) (left) Morpho peleides butterfly image. (right) Transverse section of wing scales showing christmas-tree like structure and ridges (SEM image). (b) (left) Female of a Japanese jewel beetle. Source, 229 permission granted. (right) Transverse TEM sections of cuticle showing multi-layered structures. (c) (left) Glorious scarab image. (right) SEM image of the cuticle with its multi-layered structure with helicoidal cholesteric twist. (d) (left) Snot weevil image. Source, 230 permission granted. (middle) Bright-field light microscopy image. (right) Single green-coloured scale (SEM image). Source: 178 licensed under CC BY.

Chitin also enables beetles to achieve diverse optical effects such as luminescence, iridescence, photonic structures, and polarized reflectance. Beetles like the scarab feature helicoidal nano- and microstructures in their chitin layers, selectively reflecting left-circularly polarized light. 234 , 235 Chrysomelid beetles, for instance, utilize quasi-ordered structures that produce diffuse, non-iridescent colours through light scattering. 236 At the same time, interaction with water can shift colours in both beetles and butterflies by altering refractive index and reflectance. 237 Dense chitin fibril networks in species like Cyphochilus beetles and Lepidiota stigma achieve bright whiteness through multiple scattering, whereas transparent species like the glasswing butterfly (Greta oto) use chitin nanopillars for transparency by reducing scattering along one axis. 238 , 239

Weevils demonstrate complex three-dimensional photonic crystals, such as gyroid and diamond networks, contributing to iridescent, rainbow-like appearances. 240 The rainbow weevil (Pachyrrhynchus congestus) achieves this through an inverse opal-like chitin structure with diamond symmetry. 230 In crustaceans, chitin-based Bouligand layers – periodically arranged uniaxial fibre layers in a helicoidal pattern – enhance resistance to mechanical damage. 241 , 242 Crustaceans typically do not display iridescence, unlike beetles, but species like green and blue crabs may use pigments combined with Bouligand layers as waveguides, creating mixed-colour effects. 178 , 243

Chitin’s nanostructures enable a broad spectrum of optical and mechanical functions across species. Whether enhancing structural colour, modulating transparency, or optimizing mechanical strength, chitin nanofibrils play a central role in biological adaptations, often combined with materials like CaCO3, proteins, and pigments in exoskeletons. These complex structural designs underscore the interplay between optical functionality and mechanical resilience in natural materials, guiding biomimetic advances in material science. 18 , 244

6.4 Pharmaceutical and biomedical properties

The remarkable attributes of chitin and chitosan, including biocompatibility, 245 renewable sourcing, 246 nontoxicity, 172 non-allergenicity, 247 and biodegradability, 248 enable their use across diverse biomedical and industrial applications. These biopolymers demonstrate a wide range of biological functions, such as antifungal, 249 antibacterial, 250 antitumor, 251 immunoadjuvant, 252 anti-thrombogenic, 253 and anti-cholesteremic properties, 254 enhancing their value for applications in drug delivery, tissue engineering, wound care, and film production.

Chitin and chitosan can be fabricated into various forms, including powders, films, fibres, solutions, sponges, gels, beads, and capsules, enabling their use in oral, nasal, and ocular drug delivery systems, as well as in wound dressings and vaccine delivery platforms. 255 Due to its cationic nature, chitosan can interact with cell surfaces, modulating ion transport and enhancing absorption and hydration. Its mucoadhesive properties make it particularly useful as an excipient and drug carrier, improving bioavailability and therapeutic efficacy. 256

While its insolubility and processing challenges somewhat constrain chitin’s applications, its combination with chitosan significantly expands its functional utility. Chitosan’s solubility in acidic environments, coupled with its tunable chemical and physical properties that can be further enhanced through modifications, significantly increases its versatility. 174 , 257

6.4.1 Tissue engineering

Tissue engineering aims to develop materials capable of replacing damaged tissue or stimulating advanced regenerative processes within the body. Tissue engineering involves manipulating living cells by modulating their environment or genetic engineering to create biological materials suitable for implantation. Implantable materials must meet stringent criteria, including biocompatibility, functional efficiency, mechanical strength, and long-term stability. 258

Designing polymer scaffolds for tissue engineering requires meeting several critical requirements. These include high porosity with an optimized pore size distribution and a large surface area to facilitate cell infiltration and nutrient exchange. 245 Biodegradability is equally vital, as the scaffold’s degradation rate must align with the pace of new tissue formation. 259 Structural integrity is necessary to prevent pore collapse during tissue growth, demanding robust mechanical properties. Furthermore, the scaffold must be nontoxic and biocompatible, promoting cellular adhesion, proliferation, migration, and differentiation to support effective tissue regeneration. 110 , 260

Chitin has emerged as a promising material for scaffolds in tissue engineering due to its advantageous properties. 261 It can be moulded into various forms, including hydrogels, porous sponges, and fibrous scaffolds, each tailored to specific tissue engineering applications. 262 Physical or biochemical modifications often enhance chitin utility. 176 These modifications include blending chitin with other polymers or chemically functionalizing its surface with sugars, peptides, or proteins to improve cell adhesion and bioactivity. For example, hybrid chitin nanofibers combined with silk fibroin or poly(glycolic acid) have been developed to support cell attachment and proliferation. 263 , 264

Chitin scaffolds find particular application in cartilage, bone, and tendon tissue engineering, where their mechanical and biological properties are critical for mimicking the natural extracellular matrix. 265

6.4.2 Wound healing

Research has highlighted the significant potential of chitin and chitosan in accelerating wound healing, particularly for patients with impaired healing, such as those with diabetes. 266 , 267 Chitin-based products, including powders, fabrics, beads, and films, have been extensively investigated for their medical applications due to their biocompatibility, safety, and versatility. 268

Studies demonstrate the effectiveness of chitosan scaffolds and membranes in treating deep burns and chronic wounds. 269 , 270 Innovative approaches, such as employing fungal mycelia to produce bioactive wound-healing membranes, further expand the applicability of chitosan-based materials. 271 Composite scaffolds, such as α-chitin/nanosilver and β-chitin/nanosilver, have exhibited superior antibacterial activity and enhanced hemostatic properties, making them promising candidates for wound care applications. 215 , 272

Clinical evaluations of chitosan-based dressings on skin graft donor sites have shown accelerated wound healing, improved tissue quality, and reduced healing times compared to conventional dressings. These advancements underscore the therapeutic potential of chitin and chitosan in wound healing. 110

6.4.3 Drug delivery systems

Drugs typically consist of one or more pharmacologically active agents combined with a suitable carrier to facilitate administration Smolen. 273 Effective drug delivery systems must meet several criteria: the active ingredient must be delivered selectively to the target site within the body, in precise amounts, and at a controlled rate over a specified period Cirillo et al., 274 Coelho et al., 275 , Baharlouei and Rahman. 276 Various polymers, including hydrogels, capsules, and tablets, are employed as carriers to achieve this. These carriers must exhibit biodegradability, biocompatibility, and non-toxicity, and their three-dimensional structure enables precise control over the timing and rate of drug release. 168 , 277

Polymers play a pivotal role in modulating the pharmacokinetics of active ingredients, enhancing therapeutic efficacy while minimizing side effects. 168 Natural polymers, derived from plants, animals, fungi, and bacteria, offer distinct advantages over synthetic counterparts, such as inherent biodegradability, biocompatibility, and accessibility. 278 Widely used natural polymers in pharmaceutical applications include cellulose, chitosan, and alginate. 279

Chitosan, in particular, stands out for its versatility. Its properties, including solubility, bioactivity, and functionality, are influenced by its degree of deacetylation and molecular weight, allowing for tailored applications. 280 Chitosan can be formulated into diverse dosage forms, such as tablets, capsules, hydrogels, films, membranes, and nanocomposites. 281 This adaptability enables its use in various drug delivery systems, making it an essential material for advancing precision medicine and patient-specific therapies. 282

6.4.4 Cancer treatment

Chitosan and its derivatives demonstrate considerable potential in cancer therapy, particularly for targeted drug delivery and cancer cell imaging. Advances in nanoparticle engineering have enabled the development of chitosan-based systems that facilitate precise drug delivery, controlled release, and the visualization of cancerous tissues (see Section 6.4.3). Chitosan’s biocompatibility, biodegradability, and ability to sustain the release of therapeutic agents also make it an attractive candidate for gene therapy applications Chuan et al., 283 Baharlouei and Rahman. 276

Chitosan-coated nanoparticles have shown efficacy in targeting specific cancer markers, inhibiting tumour growth, and inducing apoptosis in cancer cells. 110 , 284 , 285 The antitumor effectiveness of chitosan is influenced by its structural properties, such as degree of deacetylation, molecular weight, and the type of cancer being targeted. 286 Research indicates that chitosan oligosaccharides with specific molecular weights exhibit significant tumour-inhibiting capabilities in animal models. 287 , 288 Lower molecular weight chitosan often demonstrates enhanced antimetastatic effects and immune-stimulatory properties, critical for slowing cancer progression. 287

However, conflicting data exist regarding the influence of molecular weight on chitosan’s cytotoxicity towards cancer cells. Some studies suggest that lower molecular weight enhances antitumor activity, 287 , 288 , 289 while others report no significant differences in toxicity between varying molecular weights. 290 , 291 Despite these discrepancies, chitosan shows promise not only as an anticancer agent but also as a carrier for encapsulating and delivering anticancer drugs.

Further preclinical studies are required to unravel the precise mechanisms of chitosan’s anticancer activity, optimize its formulation, and enhance its therapeutic efficacy. These efforts are crucial to advancing chitosan-based systems into viable clinical applications and next-generation cancer treatments. 174 , 292

6.4.5 Bone regeneration

Studies highlight the structural similarity between chitin- and chitosan-based nanofibrous scaffolds and the extracellular matrix of bone, positioning these scaffolds as promising candidates for bone regeneration applications (see Section 6.4.1). These scaffolds exhibit essential features, including a high surface area, small pore size, and substantial porosity, collectively mimicking the natural bone matrix. 293 This biomimetic architecture supports cell adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation, facilitating osteogenesis. 294

Incorporating carbon nanotubes into chitosan composites has significantly enhanced their mechanical strength, improving their suitability for load-bearing applications. 295 , 296 Additionally, chitosan composites integrated with calcium phosphates, such as beta-tricalcium phosphate and hydroxyapatite, have demonstrated favourable outcomes in bone repair and regeneration, as evidenced by various animal studies. 297 , 298 These combinations capitalise on the osteoconductive properties of calcium phosphates and the biocompatibility of chitosan to promote bone healing and integration.

Researchers have employed strategies such as reinforcing the composite matrix and designing multilayered nanocomposites to optimise chitosan-based materials for bone tissue engineering further. 299 These approaches aim to improve mechanical properties, such as tensile strength and elasticity while maintaining biocompatibility and bioactivity. 245 Future research directions include fine-tuning scaffold fabrication techniques, exploring novel reinforcement materials, and conducting long-term in vivo studies to assess the efficacy and safety of these composites in clinical settings. 300 , 301 These efforts could pave the way for advanced bone tissue engineering and regenerative medicine solutions. 110 , 302

6.5 Biomimetic passive radiative cooling

Every physical object with a temperature above absolute zero (0 K or −273.15 °C) emits electromagnetic radiation, a phenomenon described by Planck’s law. Within the Earth’s atmosphere is a spectral range between 7.5 µm and 13 µm, referred to as the atmospheric window, in which atmospheric gases exhibit minimal absorption and are nearly transparent to infrared radiation. This transparency allows Earth’s surfaces to emit thermal radiation within this range directly into outer space. 303

When a surface combines high solar reflectivity with thermal solid emissivity in the atmospheric window, it can achieve cooling below ambient temperatures without requiring external energy input. This natural phenomenon, passive daytime radiative cooling (PDRC), has garnered significant interest due to its potential applications in energy-efficient cooling systems. 304

Certain species of butterflies 305 and ants 306 have evolved nanostructures on their wing scales or bodies that exploit PDRC to regulate body temperature. The Saharan Silver Ant (Cataglyphis bombycina) possesses specialized chitinous hairs with a triangular cross-section and surface indentations. 307 These structures efficiently reflect sunlight while enhancing infrared emission via Mie scattering and total internal reflection, enabling effective cooling in extreme desert environments. The hairs act as an antireflection layer in the mid-infrared, increasing heat emission, while the bare underside reflects heat from the hot desert ground more effectively than if it were covered with hairs. 308

Within the triangular hairs, Mie scattering captures light, which is then emitted in multiple directions. The hairs increase reflection at certain wavelengths due to fundamental and higher-order Mie resonance. Variations in the cross-sectional sizes of the hairs smooth out these resonance peaks, resulting in a coating with enhanced broadband reflectivity. 309 , 310

Inspired by such biological strategies, researchers investigate chitosan films derived from shrimp shells for their potential to mimic these cooling properties. Engineering these biopolymer-based materials to exhibit high solar reflectivity and tailored emissivity within the atmospheric window holds promise for sustainable cooling applications, offering a biomimetic approach to passive thermal management. 311

7 Biomimetics using keratin structures

Keratin is a structural protein with diverse morphologies tailored to its functions, from providing waterproof barriers to forming impact-resistant materials. 312 Unlike collagen, another prominent structural protein, keratin assembles through the twisting of polypeptide chains into a coiled-coil configuration. 313 Its structure consists of crystalline and amorphous regions, resulting in a combination of high toughness and a substantial Young’s modulus, enabling it to resist deformation under stress.

A defining feature of keratin is its abundance of cysteine residues, which form robust disulfide bonds. 314 These bonds cross-link the protein chains and matrix molecules, enhancing mechanical strength and stability. 315 The hierarchical organization of keratin, from its molecular configuration to its macroscopic structure, contributes to its remarkable versatility and mechanical properties, solidifying its role as an essential biomaterial in Nature. 115

7.1 Hydrophobic and bactericidal properties

Hydrophobicity is a crucial surface property often observed in natural systems. Known as the “lotus effect”, micro- and nanoscale surface roughness minimizes the contact area of water droplets, promoting self-cleaning by enabling droplets to roll off at small tilt angles, carrying dirt and debris. 316 Despite keratin’s inherent hydrophilic tendencies, this mechanism keeps surfaces dry and clean in organisms such as lotus plants and geckos.

An exemplary application of this property is the anti-icing ability of penguin feathers. 317 Their micro- and nanostructured surfaces trap air within crevices, preventing water adhesion and freezing. This air entrapment is a thermal barrier, reducing ice formation and heat transfer. Penguin feathers’ barbules and hamuli (hook-like structures) feature grooves approximately 100 nm deep, which contribute to the roughness essential for air pocket formation. 8 , 317 Hamuli are also found in the hindwings of Hymenoptera (bees, wasps, ants, and sawflies), where they connect forewings and hindwings, enhancing aerodynamic stability and efficiency during flight. 318

Various natural surfaces exhibit bactericidal properties, such as dragonfly wings, 319 cicadas wings(chitin-based), 194 and geckos (keratin-based). 320 These surfaces disrupt bacterial membranes, with some demonstrating both anti-biofouling and bactericidal effects. 321 , 322 In lizards and geckos, the outer layer of the skin, the “Oberhäutchen” (upper membrane), is composed of β-keratin. This layer often contains small spinules, which confer superhydrophobic properties, repel water, and hinder bacterial colonization. Gecko skin has been found to exhibit antibacterial properties, achieving an 88 % efficacy against gram-negative bacteria and a 66 % efficacy against gram-positive bacteria. 323

Gecko skin exhibits a static water contact angle of 151°–155°, qualifying it as superhydrophobic (contact angles >150° 324 ). 325 Unlike surfaces such as insect hairs or penguin feathers, where intricate roughness patterns dominate, gecko skin’s superhydrophobicity arises primarily from spinules’ density. 325 These structures prevent water accumulation and enable self-cleaning by facilitating droplet coalescence and runoff with minimal disturbance, effectively removing bacteria and debris. 326

These findings highlight the multi-functionality of gecko skin in resisting microbial growth and maintaining a clean, water-repellent surface, as well as the remarkable adhesive system geckos possess, which is discussed in detail in Section 7.6, offering significant inspiration for biomimetic material design.

7.2 Structural color

It is crucial to distinguish between chemical and structural colours arising from fundamentally different processes. Chemical colours result from the selective absorption and reflection of light by pigments, where specific wavelengths are absorbed by conjugated electron systems within the pigments. The absorbed energy excites electrons to higher states and is later dissipated as heat, emitted as fluorescence, or transferred to other molecules. 327 , 328

Structural colours, in contrast, arise when incident light is reflected, scattered, or deflected by structures on the scale of light’s wavelengths (380–700 nm), with minimal energy exchange between the light and the material. This type of colouration can produce vibrant, iridescent hues. Five fundamental physical phenomena contribute to structural colouration: multilayer interference, scattering, diffraction, thin film interference, and photonic crystals. 19 Many of the green, blue, and violet colours observed in Nature and all iridescent colours result from structural colouration. Such colours are typical in birds, insects, plants, algae, and viruses. The morphologies of such nanostructures include multilayer structures (such as in the iridescent throat patch of hummingbirds), two-dimensional photonic crystals (such as in the peacock and in mallard feathers) or spinodal-like channel structures (such as in the Eurasian Jay Garrulus glandarius). 8 , 329 , 330 , 331

In avian species, non-iridescent structural colours are often due to light scattering within nanostructures composed of β-keratin and air within the medullary cells of feather barb rami (branches of the feather’s central shaft). 332 These nanostructures can be categorized into two main morphological types: ‘channel’ nanostructures, which feature elongated, tortuous air channels surrounded by β-keratin bars, and ’spherical’ nanostructures, which consist of spherical air cavities encased in thin β-keratin bars, sometimes interconnected by small passages. 333 These structures form through self-assembly, creating multi-layered assemblies of β-keratin alongside pigment-based proteins such as melanin or carotenoids. The vivid colours observed in bird feathers result from combining nanostructure colouring and colour pigment mixing. 334

Despite its relatively low refractive index (∼1.5), β-keratin significantly produces high reflectance and vibrant colouration when incorporated into multi-layered structures. 8 , 334 Studies by Jeon et al. and colleagues explored how the keratin cortex surrounding multi-layered melanosomes in common feather barbules influences feather colour. 329 They discovered that altering the thickness of the keratin cortex could substantially affect the colouration, particularly the hue, while leaving other optical properties, such as saturation and brightness, largely unaffected. Both optical simulations and empirical observations underscored the importance of the keratin cortex in regulating feather colour, offering a detailed understanding of how structural elements influence colour perception.

7.3 Specific mechanical properties

Keratin-based materials, widely found in Nature, are integral to the mechanical performance of organisms, offering load-bearing capacity, impact resistance, and protective functions. One of keratin’s distinctive features is its hydration-dependent mechanical properties. When dry, keratin exhibits a high stiffness and load-bearing capacity with Young’s modulus of approximately 10 GPa. 335 , 336 , 337 In contrast, it becomes ductile when fully hydrated and exhibits a significantly reduced Young’s modulus (∼0.1 GPa), highlighting its remarkable adaptability to varying environmental conditions. 336 , 338

Keratin materials display higher-order assemblies with geometric complexity across multiple length scales, contributing to their mechanical excellence. 339 For example, the hoof walls of horses and bovines illustrate how keratin’s higher-order architecture supports energy dissipation and structural resilience. Horse hooves, subject to impact speeds of around eight m/s and forces approximating 16.1 N/kg, are primarily composed of dead keratinocytes, providing resilience without self-repair. 337 , 340 The hoof wall features a mesoscale architecture of hollow tubules (∼40 µm in diameter) encased in rigid elliptical regions (200 µm × 100 µm) embedded within a lamellar matrix of keratinocytes (Figure 5). This arrangement enhances fracture toughness by controlling crack propagation and redirection. The intertubular matrix, tubule orientation, and the volume fraction of intermediate filaments (IFs) vary through the hoof wall’s thickness, contributing to fracture resistance. Cracks initiated along tubules often divert outward by intertubular materials, sparing inner living tissues. 336 , 337 , 341 , 342 Fracture surfaces reveal energy dissipation mechanisms within IFs, keratin matrices, cell boundaries, and tubular components, ensuring efficient crack deflection and damage resistance. Hydration aids in restoring the initial shape of compressed keratin samples, demonstrating the material’s reversible deformation capabilities. 343

Hierarchical structure of the horse hoof wall, from nanoscale intermediate filaments to macroscale features. The diagram traces the formation of intermediate filaments into microfibrils, their organization within keratinocytes, hollow tubular alignment, and their integration into the hoof wall, showcasing the multiscale design contributing to its mechanical strength. Source: 8 licensed under CC BY.

Fingernails and claws, composed of keratin, further illustrate its structural diversity. These structures, critical for providing rigid support and protecting soft pads, consist of a sandwich-like tri-laminar architecture: a dorsal layer, a transverse-fibre-dominated intermediate layer and a thin ventral layer. 115 The fibre orientation influences fracture behaviour, with cracks typically propagating parallel to the nail’s free edge, avoiding damage to underlying tissues. Lamellar epithelial cells within these layers, combined with surface sutures, enhance bonding and structural integrity. 344

Environmental humidity significantly affects keratin’s mechanical properties, with increased moisture leading to reduced tensile strength. 345 This variability underscores keratin’s adaptability and its pivotal role in structural biology. From hooves to claws and nails, keratin’s multi-scale architecture and hydration-dependent properties exemplify its biological significance and potential for biomimetic applications.

7.4 Thermal insulation

Keratinous systems are highly effective thermal insulators due to their hierarchical structures and porous properties, enabling efficient air trapping. 346 These natural materials help regulate body temperatures in animals such as polar bears and penguins, enabling survival in extreme environments. 347

Penguin feathers include contour (body) and down (plume) feathers, each with distinct structures, roles and localisation. 348 Down feathers primarily comprise thermal insulation, characterised by a branched hierarchical arrangement. 349 Their structure features a central shaft (calamus) from which barbs and barbules extend, interlocked by hamuli for enhanced stability. The barbs contain a cellular core with progressively increasing porosity toward the centre, creating a foam-like structure that maximises surface area for heat retention and provides exceptional insulation. 350 , 351 This structural adaptation parallels the design of porcupine quills, which also exploit porosity and hierarchy for lightweight yet effective insulation. 352 This arrangement is similar to porcupine quills (see Section 7.5, Figure 6).

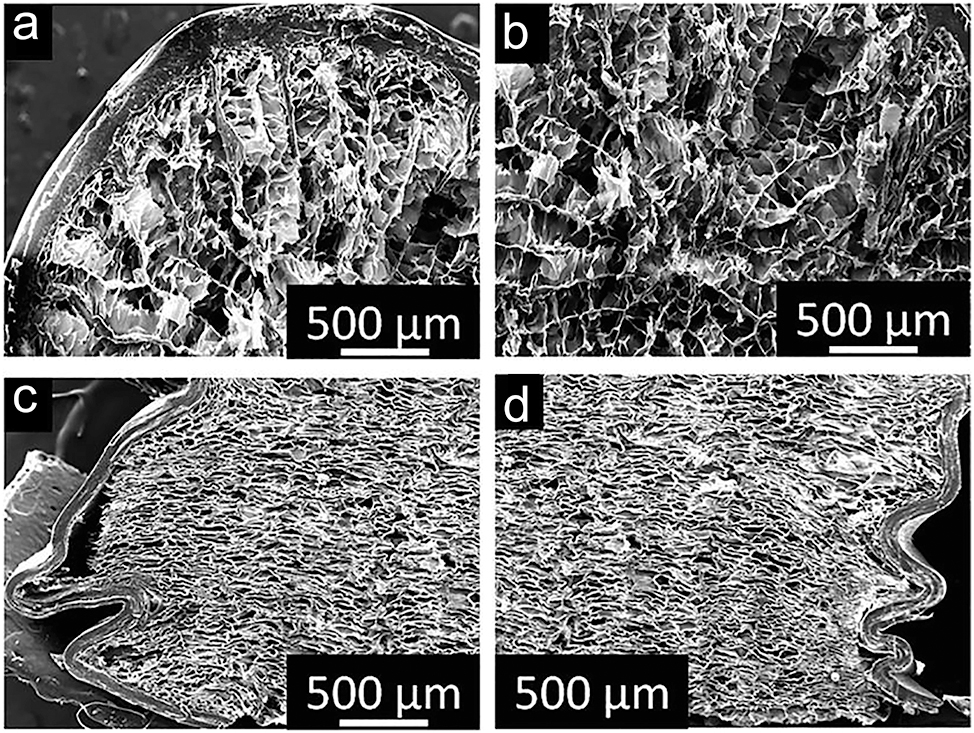

Cross-sectional micrographs of a porcupine quill: (a, b) SEM images showing the horizontal cross-section of the quill prior to compression, highlighting its structural integrity. (c, d) SEM images of the vertical cross-section post-compression, revealing deformation patterns and mechanical response. Source: 360 licensed under CC BY.

Polar bear fur, by contrast, achieves insulation through its unique dual-layered hair system. 353 The hollow guard hairs absorb ultraviolet light and channel it to the bear’s black skin, where it generates heat. 354 These hollow hairs and their air-filled medulla minimise heat loss while providing mechanical resilience. The overlapping keratinocyte-derived scales comprise the rough surface of the hair. 355 , 356 Pores in these scales connect to the cortex, tightly packed with keratin fibre bundles. These fibres, composed of coiled-coil α-keratin, are aligned along the hair shaft. Between the fibres, tubular pores prevent crack propagation, ensuring flexibility, mechanical strength, and durability. 357

The medulla’s architecture distinguishes between penguin feathers and polar bear hair. Penguin feathers exhibit foam-like porosity, whereas polar bear guard hairs contain hollow vacuoles. 356 Despite these differences, both systems demonstrate that hierarchical structures and porosity are fundamental to thermal insulation. Penguin feathers consist of β-keratin sheets, while polar bear hair comprises α-keratin. Both materials feature wrinkled outer surfaces, porosity within and on the main shafts, aligned keratin bundles in the cortex, and tubular porosity between these bundles. 356 , 358 , 359

7.5 Lightweight structures

Sandwich structures are widely utilized in engineering applications due to their unique combination of ultra-lightweight composition, efficient energy absorption, and mechanical strength comparable to bulk materials. 361 These structures achieve tailored performance by modifying the material properties and geometry of their face layers (outer cortex) and core (foam-like interior). 362 , 363 Typically, sandwich structures incorporate a high Young’s modulus material in the face layers for stiffness and a low Young’s modulus core for weight reduction, resulting in a lightweight and structurally robust material. 364 , 365 Such structures often exhibit rectangular or cylindrical cross-sections optimized for specific mechanical needs. 361

Keratin-based systems such as beaks, quills, feathers, spines, and baleen are biological analogues of engineered sandwich structures. 366 , 367 , 368 These natural designs often utilize the same material in the face and core but in different physical forms: a dense, compact face layer and a porous, foam-like core. For instance, porcupine quills, primarily composed of alpha-keratin, exemplify this arrangement 367 (Figure 6). These quills possess a thin-walled cylindrical cortex surrounding a closed-cell foam core, providing resilience against compressive and flexural loads. 367 Experiments reveal that the foam core stabilizes the structure under load, mitigating severe failures like buckling in hollow or foam-free quills. 360 The outer shell buckles into a wavy pattern upon compression, but the foam core maintains integrity and energy absorption. 366

Similarly, hedgehog spines exhibit comparable sandwich structures reinforced with longitudinal stringers and transverse plates. 369 While structurally similar to porcupine quills, hedgehog spines differ in function, serving primarily as shock absorbers during falls. In contrast, porcupine quills act as a defensive mechanism, detaching from the body and inflicting injury upon predators. These natural designs demonstrate the potential of lightweight, resilient materials in bioinspired engineering.

The combination of dense outer layers and porous cores in keratin-based systems serves as a model for designing advanced materials. By integrating foam within a rigid outer layer, these natural structures achieve remarkable mechanical properties such as impact resistance and energy dissipation, all while maintaining a low mass. 8 , 109 This bioinspired approach has significant implications for developing efficient, lightweight materials for modern engineering applications.

7.6 Reversible adhesion

Flight feathers have an additional feature. Their barbules overlap those of neighboring filaments and hook them onto one another so that they are united into a continuous vane. There are several hundred such hooks on a single barbule, a million or so in a single feather, and a bird the size of a swan has about twenty-five thousand feathers.

(David Attenborough, 370 )

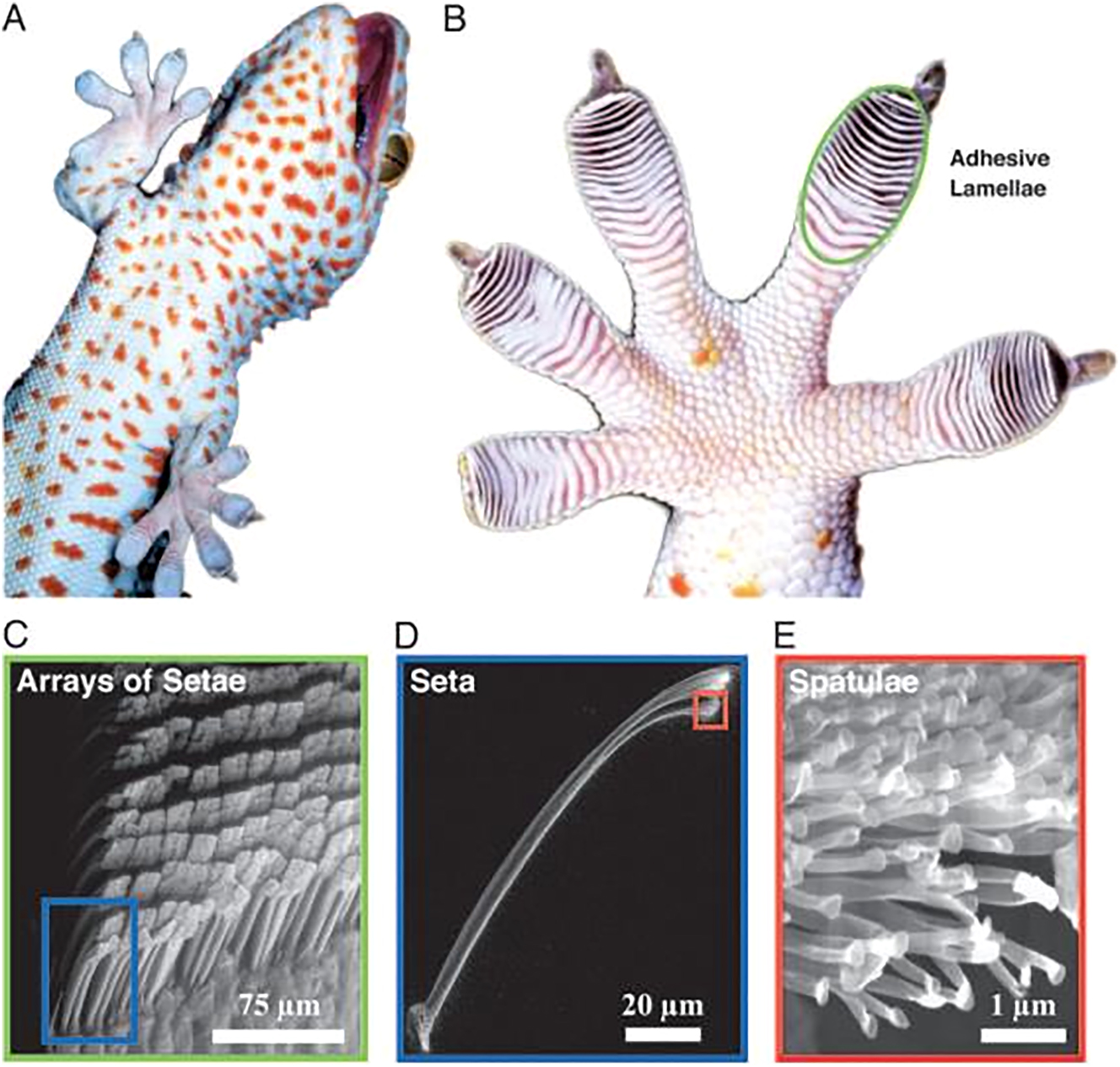

Reversible adhesion refers to the ability to adhere and detach from surfaces repeatedly without causing damage to the substrate or the adhesive organ itself. 372 This capability, widely observed in Nature, can be categorized into various mechanisms, including dry adhesion (e.g., van der Waals forces), wet adhesion (e.g., capillary forces), mechanical interlocking friction, chemical bonding, and suction resulting from pressure differences. 373 , 374 The specific mechanism employed by an organism often depends on its environmental conditions and the functional requirements of its adhesive organ. Various natural systems leverage hierarchical and nanostructured surfaces, such as those seen in keratin-based materials, to optimize adhesion properties. 8 , 375 , 376

Feather vanes provide an illustrative example of mechanical interlocking friction. Bird feathers exhibit interlocking mechanisms comprising tiny hooks (hamuli) on the barbules, which latch onto adjacent barbs to form a cohesive vane. 350 , 377 This structure is essential for maintaining the feather’s aerodynamic and mechanical integrity during flight. 350 , 378 , 379 The directional permeability of feather vanes facilitates efficient air capture, enhancing lift. The branching barbs and attached barbule network, supported by the rachis, form a lattice structure. 379 The hamuli ensure a secure connection, while these components’ geometric arrangement and rigidity contribute to efficient energy transfer and flexibility. 380 , 381 This interlocking system allows birds to “zip” and “unzip” their feathers during preening, restoring functionality and ensuring durability under mechanical stress. 382