Chemical composition, antitumor activity, and toxicity of essential oil from the leaves of Lippia microphylla

-

Aline L. Xavier

Abstract

The chemical composition, antitumor activity and toxicity of the essential oil from Lippia microphylla leaves (OEL) were investigated. The major constituents were thymol (46.5%), carvacrol (31.7%), p-cymene (9%), and γ-terpinene (2.9%). To evaluate the toxicity of OEL in non-tumor cells, the hemolytic assay with Swiss mice erythrocytes was performed. The concentration producing 50% hemolysis (HC50) was 300 μg/mL. Sarcoma 180 tumor growth was inhibited in vivo 38% at 50 mg/kg, and 60% at 100 mg/kg, whereas 5-FU at 50 mg/kg caused 86% inhibition. OEL displays moderate gastrointestinal and hematological toxicity along with causing some alteration in liver function and morphology. However, the changes were considered reversible and negligible in comparison to the effects of several anticancer drugs. In summary, OEL displays in vivo antitumor activity and a moderate toxicity, which suggests further pharmacological study.

1 Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the overall impact of cancer has more than doubled in the last 30 years. It is estimated that in 2008, there were roughly 12 million new cancer cases and seven million deaths due to cancer worldwide. Future projections indicate that cancer mortality will continue to rise, reaching 13.2 million in 2030 [1].

Natural products still serve as the major source of new therapeutic agents [2, 3]. More than two thirds of the drugs used in cancer treatment come directly from natural products or are developed using knowledge gained from the activity of their ingredients [4]. A variety of such natural products are, for example, vincristine, vinblastine, paclitaxel, docetaxel, etoposide, doxorubicin, among others [5]. Many mono- and sesquiterpenes, widely found in essential oils isolated from different species, are also known in the literature for their potent antitumor effects [6].

The family Verbenaceae contains several species that are used in therapy; this is primarily due to the presence of essential oils [7]. Most of them are traditionally utilized as gastrointestinal and respiratory remedies [8]. Several studies have demonstrated antitumor activity of isolated constituents of species of this family [9, 10]. Constituents isolated from species of the genus Lippia, the major genus of the family, have been proven to be cytotoxic against various tumor cell lines [11, 12]. Lippia microphylla Cham., popularly known as alecrim-de-tabuleiro, is rarely mentioned in either the phytochemical or pharmacological literature; there are reports of the popular use of its leaves in the treatment of respiratory diseases or as an antiseptic [13]. From the roots of the plant, tecomaquinone I and naphthoquinones have been isolated [14]. These substances displayed significant cytotoxic activity against various cell lines. Antifungal and antioxidant properties have also been reported [15, 16]. Volatile compounds from this oil have been shown to enhance the antibiotic activities of both gentamicin and norfloxacin [17]. Herewith, we report on an investigation into the essential oil from the leaves of Lippia microphylla (OEL), its chemical composition, its antitumor activity, and its toxicity in vitro and in vivo.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 General

5-Fluorouracil (5-FU), Triton X-100, Tween 80, and cyclophosphamide were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) was purchased from Mallinckrodt Chemicals (Phillipsburg, NJ, USA). Kits for biochemical analysis were purchased from Labtest (Lagoa Santa, MG, Brazil). An automatic biochemical analyzer (COBAS Mira Plus, Roche Diagnostic Systems) and an automatic hematological analyzer (Animal Blood Counter – ABC Vet, Horiba) were used.

2.2 Plant processing

The plant material was collected in June in Serra Branca – Paraíba, identified by Maria de Fatima Agra, voucher Agra et al. 6118, and deposited in Herbario Lauro Pires Xavier at the Federal University of Paraíba.

The fresh aerial parts (100 g) of Lippia microphylla were subjected to hydrodistillation for 4 h using a Clevenger-type apparatus at 40 °C. The obtained oil (0.5 mL) was yellow and fragrant. The oil was dried with anhydrous sodium sulfate and filtered. For analysis, 2 μL of the volatile oil obtained was dissolved in 1 mL of ethyl acetate.

2.3 Identification of volatile compounds of the OEL

The analysis of the oil was carried out on a Termo Scientific DSQ II GC-MS instrument (Austin, TX, USA) under the following conditions: DB-5ms (30 m×0.25 mm; 0.25 μm film thickness) fused-silica capillary column; programmed temperature: 60–240 °C (3 °C/min); injector temperature; 250 °C; carrier gas: helium, adjusted to a linear velocity of 32 cm/s (measured at 100 °C); injection type: splitless (2 μL of a 1:1000 n-hexane solution); split flow was adjusted to yield a 20:1 ratio; septum sweep was a constant 10 mL/min; EIMS: electron energy, 70 eV; temperature of ion source, and connection parts: 200 °C. The quantitative data (volatile constituents) were obtained by peak-area normalization using a FOCUS GC/FID, operated under conditions similar to those in GC-MS, (except for the carrier gas, which was nitrogen). The retention index was calculated for all the volatile constituents using an n-alkane (C8-C20, Sigma-Aldrich) homologous series.

Individual components were identified by comparison of both mass spectra and GC retention data with authentic compounds which had previously been analyzed and stored in our own library, as well as with the aid of commercial libraries containing the retention indices and mass spectra of volatile compounds commonly found in essential oils [18, 19].

2.4 Tumor cells and animals

Sarcoma 180 tumor cells were maintained in the peritoneal cavity of Swiss mice in the Bioterio Prof. Thomas George of the Federal University of Paraíba, Brazil. Thirty-eight female and six male Swiss albino mice weighing 28–32 g, obtained from the Federal University of Paraíba, and the Federal University of Pernambuco, Brazil, were used. The animals were housed in cages with free access to food and water. All animals were kept under a 12 h/12 h light-dark cycle (lights on at 6:00 a.m.). Actions on reducing pain, stress and any suffering were taken in accordance with ethical guidelines for animal usage. The Animal Studies Committee of the Federal University of Paraíba had approved the experimental protocol (number 0509/109).

2.5 Hemolysis assay

The hemolytic activity of OEL was tested using mice erythrocytes [20]. Briefly, fresh blood samples were collected with a heparinized capillary to prevent blood coagulation. To obtain a pure suspension of erythrocytes, 2 mL of whole blood were added to 10 mL PBS, pH 7.4, and centrifuged. The supernatant was then removed by gentle aspiration, and the above process was repeated two more times. Erythrocytes were finally resuspended in PBS to make 1% (v/v) solution for the hemolysis assay. Various concentrations (47–875 μg/mL) of OEL dissolved in DMSO (5% v/v in PBS) were added to the suspension of red blood cells obtained from the mice. Tubes with the OEL-erythrocyte mixtures were incubated on a shaker for 60 min and then centrifuged. The absorbance of the supernatants was determined at 540 nm using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (SHIMADZU®) to measure the extent of red blood cell lysis, and the concentration producing 50% hemolysis (HC50) was determined. Positive controls (100% hemolysis), and negative controls (0% hemolysis) were also determined by incubating erythrocytes with 1% Triton X-100 in PBS, and 5% DMSO in PBS, respectively.

2.6 Determination of the effects of OEL on tumor growth in vivo

Eight-day-old sarcoma 180 ascites cells (0.2 mL–25×106 cells/mL) were implanted subcutaneously into the left sub-axillary region of the female mice [21]. One day after inoculation, OEL (50 or 100 mg/kg) was dissolved in 5% (v/v) Tween-80, and administered intraperitoneally for 7 days to mice transplanted with sarcoma 180 tumor. 5-FU (50 mg/kg) was used as a standard drug. The healthy group (healthy mice) and tumor control group (mice bearing sarcoma 180), were inoculated with 5% Tween-80 in 0.9% (w/v) NaCl. On the eighth day, peripheral blood samples from all mice were collected from the retro-orbital plexus under light sodium thiopental anesthesia (40 mg/kg). The animals were then sacrificed by cervical dislocation. The tumors were excised and weighed. The rate of tumor growth inhibition in percent was calculated by the following formula: Inhibition (%)=[(A–B)/A]×100, where A is the average of the tumor weights of the tumor control group, and B is that of the treated group.

2.7 Toxicological analyses

Body weights were registered at the beginning and end of the treatment, and the animals were observed daily for signs of behavioral abnormalities (depressant or excitatory effects on the central or autonomic nervous system) throughout the course of the study [22]. The liver, spleen, thymus, and kidneys were excised and weighed for the calculation of their organ indices according to the following formula: organ index=organ weight (mg)/animal weight (g). For biochemical analysis, blood samples from the animals were centrifuged, and the levels of urea and creatinine, as well as the activities of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) were determined. For the hematological analysis, heparinized whole blood was used, and the following hematological parameters were determined: hemoglobin (Hb) level, red blood cell (RBC) count, hematocrit (Hct), and the red cell indices mean corpuscular volume (MCV), mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH), and mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC), as well as total and differential leukocyte counts. After weight determination and fixation in 10% (v/v) formaldehyde, livers, and kidneys were examined for size, color changes, and hemorrhage. Portions of the livers and kidneys were cut into small pieces, then into sections of 5 μm, and stained with hematoxylin-eosin. For detection of hepatic fibrosis, the liver sections were stained according to [23] and examined microscopically for lesions.

2.8 Genotoxicity

For the micronucleus assay, groups of six Swiss male mice were treated intraperitoneally with doses of OEL at 50, 100 and 150 mg/kg, respectively. A group treated with a standard drug (cyclophosphamide, 50 mg/kg, i.p.), and a control group (saline containing 5% Tween 80) were included. After 24 h, the animals were anesthetized with sodium thiopental (40 mg/kg) and peripheral blood samples were collected at the orbital plexus for blood smears. For each animal, three blood smears were prepared, and a minimum of 2000 erythrocytes were counted to determine the frequency of micronucleated erythrocytes [24].

2.9 Statistical analysis

The in vitro assays were performed in quadruplicate and repeated three times. Data are presented as mean±SEM. The HC50 value and their 95% confidence intervals (CI 95%) were obtained by nonlinear regression. The differences between experimental groups were compared by analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey’s test (p<0.05).

3 Results and discussion

Twenty-six compounds, representing 99.9% of the OEL were identified. The main chemical components identified were thymol (46.5%), carvacrol (31.7%), p-cymene (9%), and γ-terpinene (2.9%) (Table 1). The chemical composition of essential oil from the leaves of Lippia microphylla differs from that published by [25]. This difference is expected, since the plants were collected at different times and in different regions; these are factors that can change the chemical composition of volatile components. However, the chemical composition of Lippia microphylla presented here is consistent with that of other Lippia species in which thymol is always a major component [26–28].

Chemical composition of OEL.

| RI | Compound | (% of total) |

|---|---|---|

| 929 | α-Pinene | 0.51 |

| 988 | Myrcene | 1.4 |

| 1014 | α-Terpinene | 0.2 |

| 1023 | p-Cymene | 9.0 |

| 1055 | γ-Terpinene | 2.92 |

| 1088 | p-Cimenene | 0.1 |

| 1097 | trans-Sabinene hydrate | 0.1 |

| 1128 | Alloocimene | 0.1 |

| 1133 | cis-p-Mentha-2,8-dien-1-ol | 0.1 |

| 1170 | Umbelliferone | 0.12 |

| 1179 | 4-Terpineol | 0.57 |

| 1182 | p-Cimen-8-ol | 0.1 |

| 1186 | α-Terpineol | 0.1 |

| 1227 | O-Methylthymol | 0.28 |

| 1236 | Methylcarvacrol | 0.20 |

| 1293 | Thymol | 46.52 |

| 1301 | Carvacrol | 31.74 |

| 1343 | Carvacrol acetate | 1.61 |

| 1362 | Thymol acetate | 1.32 |

| 1415 | β-Caryophyllene | 1.15 |

| 1430 | trans-α-Bergamotene | 0.11 |

| 1451 | α-Humulene | 0.06 |

| 1476 | Butylated 4-hydroxyanisol | 0.68 |

| 1505 | β-Bisabolene | 0.42 |

| 1537 | Spathulenol | 0.16 |

| 1576 | Oxide Caryophyllene | 0.42 |

| Total | 99.99 |

RI, Retention Index.

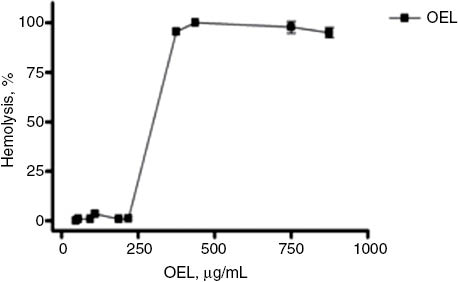

To evaluate the toxicity of OEL in non-tumor cells, a hemolytic assay with Swiss mice erythrocytes was performed. The percentage of hemolysis increased in an OEL concentration-dependent manner. The concentration producing 50% hemolysis (HC50 value) was in the range of 300 (283.4–317.9) μg/mL, (Figure 1), suggesting that OEL has low toxicity against cells which are commonly affected in anticancer treatments [5].

Percentage of hemolysis in red blood cells of Swiss mice upon treatment with OEL (μg/mL). Each dot represents the average±SEM of three experiments with three replicates, with a 95% confidence interval.

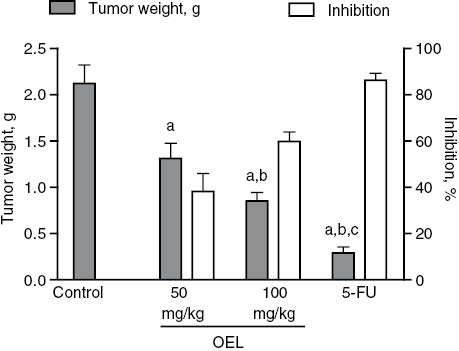

Mice transplanted with sarcoma 180 were treated i.p. with OEL at (50 and 100 mg/kg) for 7 days. In comparison to the tumor control group, a significant reduction in tumor weight was observed in both groups. Eight days after implantation, the average tumor weight was 2.12±0.20 g in the tumor control group, and 1.31±0.17 g, and 0. 85±0.09 g in OEL treated groups at 50 and 100 mg/kg, respectively. In mice treated with 5-FU (50 mg/kg) tumor weight was also significantly reduced (0.29±0.06 g). Inhibition was 38, 60 and 86% for treatment with OEL at 50 and 100 mg/kg, and 5-FU, respectively (Figure 2). Thus, OEL displayed significant in vivo antitumor activity for both tested doses.

Effect of OEL and 5-FU on tumor weight and inhibition of tumor growth in mice transplanted with sarcoma 180. Data are expressed as average±SEM of six animals analyzed by ANOVA followed by Tukey test. ap<0.05 compared to tumor control. bp<0.05 compared to OEL (50 mg/kg). cp<0.05 compared to OEL (100 mg/kg).

Considering the various toxic side effects of anticancer agents on normal cells, we proceeded to investigate possible OEL toxicity. Virtually all cancer drugs promote gastrointestinal disorders, including anorexia. Anorexia is directly linked to malnutrition and weight loss [29]. Table 2 provides data on the animals’ water and feed consumption for 7 days of treatment with OEL, and their change in weight. A significant decrease in water and feed consumption of animals treated with the highest dose of OEL and 5-FU was observed, which corresponded to a significant decrease in weight. These results indicate toxicity of OEL to the gastrointestinal system at 100 mg/kg, however, such effects are observed with most anticancer drugs currently in use, as seen here for 5-FU. As such, this effect is not a principally limiting factor for pre-clinical pharmacological studies.

Feed and water consumption and weight of animals (n=6) subjected to different treatments (7 days).

| Group | Dose, mg/kg | Water consumption, mL | Feed consumption, g | Initial weight, g | Final weight, g |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy animals | – | 42.9±3.0 | 31.9±2.3 | 29.4±0.5 | 32.6±0.8 |

| Tumor control | – | 52.9±1.5 | 31.2±1.8 | 29.1±0.7 | 38.5±1.1 |

| 5-FU | 50 | 34.6±3.5a | 18.5±3.2a | 27.5±0.7 | 22.1±0.9a |

| OEL | 50 | 54.2±2.4 | 26.1±1.6 | 25.1±0.7 | 32.0±0.7 |

| OEL | 100 | 31.1±3.6a | 17.3±2.4a | 24.0±0.5 | 23.7±0.7a |

Data presented as mean±SEM of six animals analyzed by ANOVA followed by Tukey test. ap<0.05 compared to tumor control.

Concerning biochemical and hematological parameters, no significant changes were observed in urea and creatinine levels in all the groups (Table 3). Urea is a product of amino acid metabolism, and creatinine is a breakdown product of muscle creatine; both substances are excreted by the kidneys [30]. Upon kidney failure, degradation products of metabolism, particularly nitrogenous substances such as urea and creatinine, accumulate in the body, resulting in increased serum levels. Several anticancer drugs currently in clinical use trigger some form of renal toxicity [21]. However, renal toxicity was not observed for OEL.

Effects of 5-FU and OEL on biochemical parameters of peripheral blood of mice (n=6) subjected to different treatments (7 days).

| Group | Dose, mg/kg | AST, U/L | ALT, U/L | Urea, mg/dL | Creatinine, mg/dL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy animals | – | 103.7±6.7 | 55.7±2.0 | 52.8±0.8 | 0.46±0.02 |

| Tumor control | – | 202.7±6.7a | 71.8±3.3 | 32.8±3.6 | 0.40±0.03 |

| 5-FU | 50 | 197.4±29.2a | 62.7±21.6 | 40.8±5.1 | 0.42±0.04 |

| OEL | 50 | 283.2±16.8a,b | 91.0±7.9 | 29.2±2.9 | 0.32±0.02 |

| OEL | 100 | 400.8±17.1a,b | 152.3±5.2a,b | 36.6±4.4 | 0.33±0.02 |

Data presented as mean±SEM of six animals analyzed by ANOVA followed by Tukey test. ap<0.05 compared to healthy animals; bp<0.05 compared to tumor control.

With regard to liver function, significant increases in the activities of aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) were observed in the serum of OEL-treated, but not FU-treated, mice (Table 3). Tumor implantation alone increased AST activity in the tumor control group as compared to the healthy group (Table 3). Like kidneys, the liver is susceptible to the effects of anti-neoplastic agents. In cases of liver injury, AST and ALT spill into the blood thus allowing diagnosis and monitoring of liver injury [31]. However, while AST is found in liver cells, it is also found in skeletal and cardiac muscle, kidneys, pancreas, and erythrocytes. When any of these tissues is damaged, AST is released into the blood. Since there are no routine laboratory methods available to determine the origin of AST in blood, diagnosis of the cause of its increase should take into account the possibility of injury to any of the organs where it resides [32]. The significant increase in transaminase activity suggests oil-induced liver toxicity for the higher dose employed here. We noted an increase in AST activity in all transplanted animals, regardless of the treatment, which may be related to tumor-caused damage to one or more of the tissues harboring AST. Skeletal muscle is one of the likely sources, due to mechanical trauma caused by a tumor invading the sub-axillar region. The liver is the other likely source, because it is a complex organ involved in many functions, among them, participation in the mononuclear phagocyte system, and it is the primary site of the removal of antigen-antibody complexes from circulation.

Regarding hematologic parameters, unlike most antineoplastic agents, OEL did not significantly affect the major hematological parameters of the animals (Table 4). There was, however, an increase in the value of the mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC). The erythrocyte indices MCV, MCH and MCHC are used in the diagnosis of anemias, but this particular result may be related to some degree of hemolysis of the samples since no significant changes were observed in RBC, MCV and MCH [31].

Effects of 5-FU and OEL on hematological parameters of peripheral blood of mice (n=6) subjected to different treatments (7 days).

| Group | Dose, mg/kg | Red blood cells, 106/mm3 | Hemoglobin, g/dL | Hematocrit, mg/dL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy animals | – | 8.5±0.1 | 14.4±0.1 | 47.6±0.6 |

| Tumor control | – | 7.6±0.2 | 13.4±0.3 | 41.2±1.2 |

| 5-FU | 50 | 8.7±0.6 | 15.6±0.9 | 45.4±3.3 |

| OEL | 50 | 6.6±0.2 | 12.0±0.7 | 35.9±2.0 |

| OEL | 100 | 7.5±0.4 | 14.0±0.7 | 39.5±2.2 |

Data presented as mean±SEM of six animals analyzed by ANOVA followed by Tukey test.

| Group | Dose, mg/kg | MCV, fm3 | MCH, pg | MCHC, g/dL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy animals | – | 56.2±0.2 | 17.3±0.1 | 29.4±0.1 |

| Tumor control | – | 54.7±0.8 | 17.7±0.3 | 32.5±0.6a |

| 5-FU | 50 | 52.3±1.4 | 18.0±0.6 | 34.5±0.7a,b |

| OEL | 50 | 54.3±2.0 | 18.2±0.8 | 33.4±0.2a |

| OEL | 100 | 53.3±0.8 | 18.8±0.3 | 35.8±0.4a,b |

Data presented as mean±SEM of six animals analyzed by ANOVA followed by Tukey test. ap<0.05 compared to healthy animals; bp<0.05 compared to tumor control.

| Group | Dose, mg/kg | Total leukocytes, 103/mm3 | White blood cell differential count, % | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lymphocytes | Neutrophils | Monocytes | Eosinophils | |||

| Healthy animals | – | 7.9±0.7 | 76.0±1.5 | 27.8±1.7 | 1.3±0.2 | 1.7±0.2 |

| Tumor control | – | 9.6±1.5 | 42.7±3.7a | 47.2±3.8a | 5.3±0.8a | 1.5±0.6 |

| 5-FU | 50 | 0.6±0.1b | 94.0±1.4a,b | 2.7±0.9a | 2.3±0.3b | 0.3±0.3 |

| OEL | 50 | 14.2±2.7 | 39.2±5.0a | 56.7±4.5a | 2.3±0.6b | 1.8±0.3 |

| OEL | 100 | 14.1±3.4 | 45.3±7.9a | 48.8±7.4a | 3.5±0.9 | 2.0±0.5 |

Data presented as mean±SEM of six animals analyzed by ANOVA followed by Tukey test. ap<0.05 compared to healthy animals; bp<0.05 compared to tumor control.

In the tumor control group, the percentage of monocytes was significantly increased above that of the healthy group. The primary function of a monocyte is phagocytosis and digestion of large particulate matter such as senescent cells and necrotic cellular debris [33]. This can explain the increase of this cell type in the tumor-bearing mice. A comparable increase of this cell type was not observed in animals treated with 5-FU or OEL, probably due to the inhibitory effect on tumor growth and hence reduced need for phagocytosis.

Additionally, it should be noted that the percentage of neutrophiles was increased in all transplant groups, regardless of treatment. This phenomenon is observed in cases of tissue necrosis and in the presence of tumors [34]. Likewise, the percentage of lymphocytes was decreased in all transplant groups, which is likely related to the reduced lymphocyte counts observed in moribund animals [34].

A marked leukopenia (decreased white blood cell count) with an increase in the lymphocyte percentage was evident in animals treated with 5-FU. Such changes are expected in antineoplastic treatment [35].

To evaluate possible toxic effects of OEL on the animals’ organs (liver, kidneys, spleen and thymus), these were excised, weighed and analyzed macroscopically for the presence of necrosis or bleeding. No changes were observed in any of the treated animals, with the exception that the spleen index was reduced significantly in animals treated with 100 mg/kg OEL, thereby the increase of this parameter caused by tumor inoculation was reversed (Table 5). 5-FU, a drug currently used in clinical medicine, which reduces spleen and thymus indices, exerts a potent immunosuppressive effect [36]. There is a close relationship between the occurrence, growth, and decline of a tumor, and the general state of the immune system. Immune function in an organism may respond not only during the generation and development of the tumor, but it may also be an important factor in preventing the patient’s tumor from returning [37]. Thus, one of the major drawbacks of current anticancer therapies, such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy, is the suppression of the immune system [38], which was not observed in the treatment with OEL.

Effects of 5-FU and OEL on the mice organ indices (n=6) subjected to different treatments (7 days).

| Group | Dose, mg/kg | Thymus index, mg/g | Spleen index, mg/g | Liver index, mg/g | Kidney index, mg/g |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy animals | – | 3.4±0.2 | 5.2±0.3 | 62.1±1.4 | 10.8±0.2 |

| Tumor control | – | 3.9±0.4 | 8.5±0.8a | 68.8±2.2 | 9.3±0.2 |

| 5-FU | 50 | 1.8±0.3a,b | 2.7±0.3a,b | 57.8±2.7b | 11.0±0.1 |

| OEL | 50 | 3.8±0.5 | 6.9±0.4 | 65.3±1.9 | 9.1±0.6 |

| OEL | 100 | 2.3±0.6 | 5.5±0.5b | 62.6±2.1 | 10.9±0.6 |

Data presented as SEM of the mean of six animals analyzed by ANOVA followed by Tukey test. ap<0.05 compared to healthy animals; bp<0.05 compared to tumor control.

5-FU also reduced the liver index, revealing the hepatotoxic effect of this drug, which corroborates literature data [36].

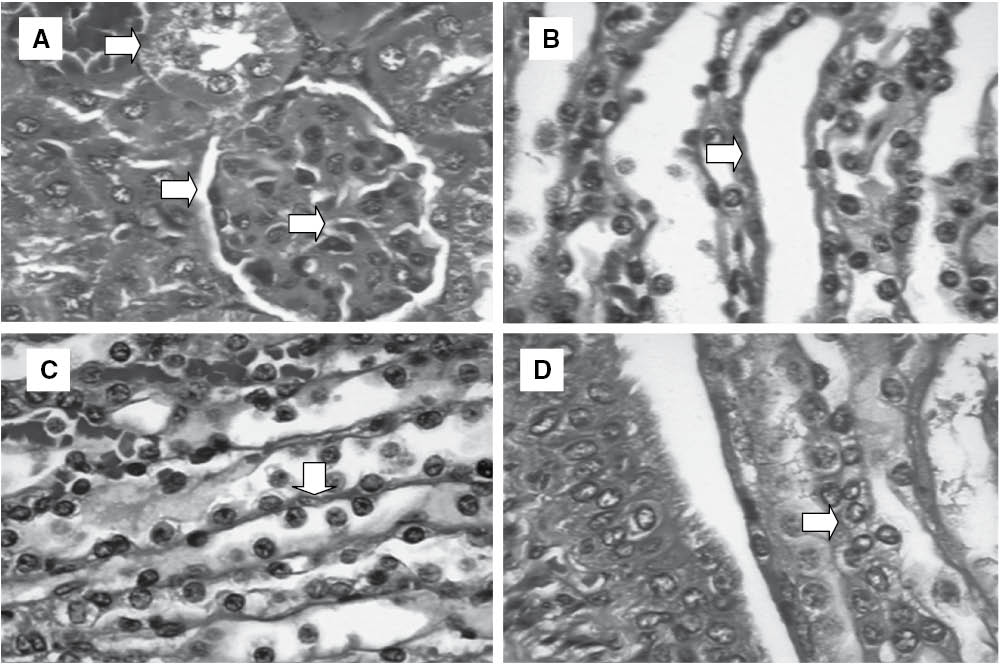

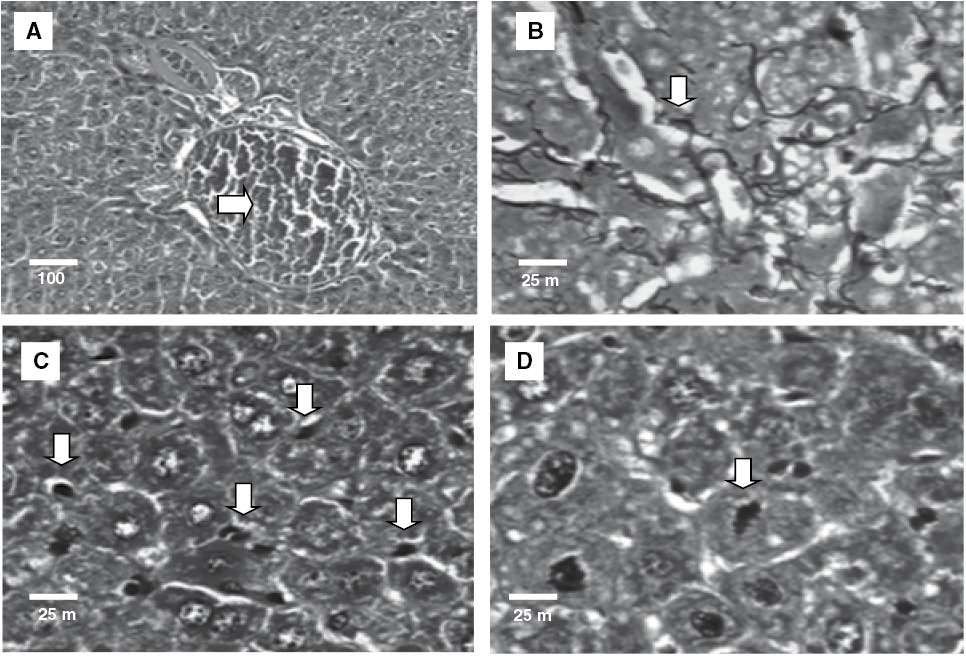

For a more detailed evaluation of possible toxic effects on the organs of the treated animals, a histological analysis was carried out. The kidneys of the mice from all groups did not differ histologically (Figure 3), indicating low OEL toxicity in kidneys, thereby corroborating the results of the biochemical analysis of renal function (Table 3). On the other hand, while the livers of animals treated with 5-FU or OEL at a dose of 50 mg/kg displayed preserved lobular architecture, lobular and portal venous congestion was observed (Figure 4A), as well as small and sparse foci of hepatocellular necrosis with deposition of thin collagen fibers (fibrosis) (Figure 4B), and Kupffer cell hyperplasia (Figure 4C). The same changes, albeit more frequent, were observed in animals treated with a dose of 100 mg/kg. In addition, in two animals treated with an OEL dose of 50 mg/kg a hepatocellular proliferative effect was observed (Figure 4D). These findings suggest a toxic effect on this organ, corroborating the finding of increased AST and ALT activities as a consequence of OEL treatment (Table 3). These changes, common to both groups treated with OEL, have been reported in the literature as evidence of weak hepatotoxicity during which withdrawal or reduction of the dose of the drug usually leads to rapid recovery from the damage [39]. The liver is an organ with great regenerative and adaptive ability, even when hepatocellular necrosis is present, as observed in the livers of the OEL-treated animals. If the conjunctive tissue is preserved, regeneration can be almost complete [40].

Histopathology of kidneys of experimental groups: (A) Glomerulus preserved with thin Bowman’s capsule, capillary tuft supported by delicate mesangium, proximal convoluted tubule – Control; (B) Proximal convoluted tubule – 5-FU (50 mg/kg); (C) Loop of Henle – OEL (100 mg/kg) and (D) Distal convoluted tubule – OEL (100 mg/kg). Hematoxylin-eosin.

Histopathology of liver of experimental groups: (A) lobular and portal venous congestion – 5-FU (50 mg/kg); (B) reticulin collapse – OEL (50 mg/kg); (C) Kupffer cell hyperplasia – OEL (100 mg/kg) and (D) isolated mitoses – OEL (100 mg/kg). Hematoxylin-eosin (A, C and D) and Gordon and Sweet method for reticulin (B).

The medical use of essential oils is not regulated in many countries, even though little is known about their toxicity. Few publications on essential oils contain data on their “latent” toxicities such as teratogenesis, carcinogenesis, or mutagenesis [41]. The genotoxic effects of anticancer drugs in non-tumor cells are of special significance for the possible induction of secondary tumors in patients undergoing therapy [42]. To evaluate possible in vivo genotoxic effects of OEL, we checked the frequency of micronucleated erythrocytes in peripheral blood, but found no such effect of OEL (Table 6). This suggests that OEL does not have in vivo genotoxic (clastogenic and/or aneugenic) effects, an important aspect of its therapeutic applicability.

Number of micronucleated erythrocytes in peripheral blood of mice treated with single doses of OEL and cyclophosphamide (n=6).

| Group | Dose, mg/kg | Number of micronucleated cells |

|---|---|---|

| Control | – | 5.3±0.9 |

| Cyclophosphamide | 50 | 39.2±2.7a |

| OEL | 50 | 6.2±0.5 |

| OEL | 100 | 5.8±0.6 |

| OEL | 150 | 10.0±1.0 |

Data presented as SEM of the mean of six animals analyzed by ANOVA followed by Tukey test. ap<0.05 compared to tumor control.

4 Conclusions

OEL has significant in vivo antitumor activity, along with low toxicity. Our results may assist in developing novel OEL based chemotherapeutic agents.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Brazilian agencies Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES) and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq). David Peter Harding performed English editing of the manuscript.

Authors’ conflict of interest disclosure: We do not have any conflict of interest for the present paper.

References

1. Ferlay J, Shin H, Bray F. Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC Cancer Base No.10. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer. 2010. Acess in http://globocan.iarc.fr.Search in Google Scholar

2. Manjegowda CM, Deb G, Limaye AM. Epigallocatechin gallate induces the steady state mRNA levels of pS2 and PR genes in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Indian J Exp Biol 2014;52:312–6.Search in Google Scholar

3. Castello-Branco M, Tavares J, Silva M, Barbosa-Filho JM, Anazetti MC, Frungillo L, et al. Xylodiol from Xylopia langsdorfiana induces apoptosis in HL60 cells. Braz J Pharmaco 2011;21:1035.10.1590/S0102-695X2011005000135Search in Google Scholar

4. Efferth T. Cancer therapy with natural products and medicinal plants. Planta medica 2010;76:1035–6.10.1055/s-0030-1250062Search in Google Scholar

5. Brandão HN, David JP, Couto RD, Nascimento JA, David JM. Química e farmacologia de quimioterápicos antineoplásicos derivados de plantas. Quim Nova 2010;33:1359–69.10.1590/S0100-40422010000600026Search in Google Scholar

6. Sobral MV, Xavier AL, Lima TC, Sousa DP. Antitumor Activity of monoterpenes found in essential oils. Sci World J 2014;2014:1–35.10.1155/2014/953451Search in Google Scholar

7. Santos JS, Melo JI, Abreu MC, Sales MF. Verbenaceae sensu stricto na região de Xingó: Alagoas e Sergipe, Brasil. Rodriguésia 2009;60:985–98.10.1590/2175-7860200960412Search in Google Scholar

8. Pascual ME, Slowing K, Carretero E, Sánchez Mata D, Villar A. Lippia: traditional uses, chemistry and pharmacology: a review. J Ethnopharmacol 2001;76:201–14.10.1016/S0378-8741(01)00234-3Search in Google Scholar

9. Tailor NK, Boon HL, Sharma M. Synthesis and in vitro anticancer studies of novel C-2 arylidene congeners of lantadenes. Eur J Med Chem 2013;64:285–91.10.1016/j.ejmech.2013.04.009Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Wang WX, Xiong J, Tang Y, Zhu JJ, Li M, Zhao Y, et al. Rearranged abietane diterpenoids from the roots of Clerodendrum trichotomum and their cytotoxicities against human tumor cells. Phytochemistry 2013;89:89–95.10.1016/j.phytochem.2013.01.008Search in Google Scholar PubMed

11. Gonzalez-Guëreca MC, Soto-Hernandez M, Martinez-Vazquez M. Isolation of (-)(2S)-5,6,7,3′,5′-pentahydroxyflavanone-7-O-beta-D-glucopyranoside, from Lippia graveolens H.B.K. var. berlandieri Schauer, a new anti-inflammatory and cytotoxic flavanone. Nat Prod Res 2010;24:1528–36.10.1080/14786419.2010.488234Search in Google Scholar

12. Mesa-Arango AC, Montiel-Ramos J, Zapata B, Duran C, Betancur-Galvis L, Stashenko E. Citral and carvone chemotypes from the essential oils of Colombian Lippia alba (Mill.) N.E. Brown: composition, cytotoxicity and antifungal activity. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2009;104:878–84.10.1590/S0074-02762009000600010Search in Google Scholar PubMed

13. Agra MD, Freitas PF, Barbosa-Filho JM. Synopsis of the plants known as medicinal and poisonous in Northeast of Brazil. Revista Brasileira de Farmacognosia 2007;17:114–40.10.1590/S0102-695X2007000100021Search in Google Scholar

14. Santos HS, Costa SM, Pessoa OD, Moraes MO, Pessoa C, Fortier S, et al. Cytotoxic naphthoquinones from roots of Lippia microphylla. Z Naturforsch 2003;58c:517–20.10.1515/znc-2003-7-812Search in Google Scholar PubMed

15. David JP, Meira M, David JM, Brandão HN, Branco A, Agra MF, et al. Radical scavenging, antioxidant and cytotoxic activity of Brazilian Caatinga plants. Fitoterapia 2007;78:215–8.10.1016/j.fitote.2006.11.015Search in Google Scholar PubMed

16. Souza EL, Lima ED, Freire KR, Sousa CP. Inhibitory action of some essential oils and phytochemicals on the growth of various moulds isolated from foods. Braz Arch Biol Techn 2005;48:245–50.10.1590/S1516-89132005000200011Search in Google Scholar

17. Coutinho HD, Rodrigues FF, Nascimento EM, Costa JG, Falcão-Silva VS, Siqueira-Júnior JP. Synergism of gentamicin and norfloxacin with the volatile compounds of Lippia microphylla Cham.(Verbenaceae). J Essent Oil Res 2011;23:24–8.10.1080/10412905.2011.9700443Search in Google Scholar

18. Adams RP. Identification of essential oil components by gas chromatography/quadrupole mass spectroscopy. Carol Stream, Allured Publ. Corp. EUA, 2001.Search in Google Scholar

19. NIST/EPA/HIH Mass Spectral Library. Nist Mass Spectral Search Program (NIST 05, Version 2.0d). Gaithersburg, MD: The NIST Mass Spectrometry Data Center, 2005.Search in Google Scholar

20. Kang C, Munawir A, Cha M, Shon ET, Lee H, Kim JS, et al. Cytotoxicity and hemolytic activity of jellyfish Nemopilema nomurai (Scyphozoa: Rhizostomeae) venom. Comp Biochem Physiol C Toxicol Pharmacol 2009;150:85–90.10.1016/j.cbpc.2009.03.003Search in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Bezerra D, de Castro F, Alves A, Pessoa C, de Moraes MO, Silveira ER, et al. In vitro and in vivo antitumor effect of 5-FU combined with piplartine and piperine. J Appl Toxicol 2008;28:156–63.10.1002/jat.1261Search in Google Scholar PubMed

22. Almeida RN, Falcão AC, Diniz RS, Quintans Jr. LJ, Polari RM, Barbosa-Filho JM, et al. Metodologia para avaliação de plantas com atividade no Sistema Nervoso Central e alguns dados experimentais. Revista Brasileira de Farmacognosia 1999;80:72–6.Search in Google Scholar

23. Gordon H, Sweet HH. A simple method for the silver impregnation of reticulin. Am J Pathol 1936;12:545–51.10.1002/path.1700430311Search in Google Scholar

24. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (1997). Guidelines Nos. 471 to 476, adopted 1997.Search in Google Scholar

25. Costa SM, Santos HS, Pessoa OD, Lemos TL. Constituents of the essential oil of Lippia microphylla Cham. from Northeast Brazil. J Essent Oil Res 2005;17:378–9.10.1080/10412905.2005.9698935Search in Google Scholar

26. Franco CS, Ribeiro AF, Carvalho NC, Monteiro OS, Silva JK, Andrade EH, et al. Composition and antioxidant and antifungal activities of the essential oil from Lippia gracilis Schauer. Afr J Biotechnol 2014;13:3107–13.10.5897/AJB2012.2941Search in Google Scholar

27. Maia JG, Andrade EH. Database of the Amazon aromatic plants and their essential oils. Quim Nova 2009;32:595–622.10.1590/S0100-40422009000300006Search in Google Scholar

28. Veras HN, Rodrigues FF, Colares AV, Menezes IR, Coutinho HD, Botelho MA, et al. Synergistic antibiotic activity of volatile compounds from the essential oil of Lippia sidoides and thymol. Fitoterapia 2012;83:508–12.10.1016/j.fitote.2011.12.024Search in Google Scholar

29. Talmadge J, Singh R, Fidler I, Raz A. Murine models to evaluate novel and conventional therapeutic strategies for cancer. Am J Pathol 2007;170:793–804.10.2353/ajpath.2007.060929Search in Google Scholar

30. Pereira J. Bioquímica clínica. João Pessoa: Editora Universitária/UFPB, Brazil, 1998.Search in Google Scholar

31. Henry J. Diagnósticos clínicos e tratamento por métodos laboratoriais. Barueri: Manole, 2008.Search in Google Scholar

32. Miller O, Gonçalves R. Laboratório para o clinico. São Paulo: Atheneu, 1999:61.Search in Google Scholar

33. Gad S. Animal models in toxicology. New York: Taylor & Francis Group, 2007.10.1201/9781420014204Search in Google Scholar

34. Evans G. Animal hematotoxicology. New York: CRC Press, 2009:78.10.1201/9781420080100Search in Google Scholar

35. Pita JC. Avaliação da atividade antitumoral e toxicidade do trachylobano-360 de Xylopia langsdorffiana St. Hil. & Tul. (Annonaceae). João Pessoa: Federal University of Paraíba, 2010.Search in Google Scholar

36. Eichhorst S, Müerköster S, Weigand M, Krammer PH. The chemotherapeutic drug 5-fluorouracil induces apoptosis in mouse thymocytes in vivo via activation of the CD95 (APO-1/Fas) system. Cancer Res 2001;61:243–8.Search in Google Scholar

37. Mitchell M. Immunotherapy as part of combinations for the treatment of cancer. Int Immunopharmacol 2003;3:1051–9.10.1016/S1567-5769(03)00019-5Search in Google Scholar

38. Deng W, Sun H, Chen F, Yao ML. Immunomodulatory activity of 3beta, 6beta-dihydroxyolean-12-en-27-oic acid in tumor-bearing mice. Chem Biodivers 2009;8:1243–53.10.1002/cbdv.200800187Search in Google Scholar PubMed

39. Montenegro R, Farias R, Pereira M, Alves AP, Bezerra FS, Andrade-Neto M, et al. Antitumor activity of pisosterol in mice bearing with S180 tumor. Biol Pharm Bull 2008;31:454–7.10.1248/bpb.31.454Search in Google Scholar PubMed

40. Kummar V, Abbas A, Fausto N. Robbins and Cotran pathology basis of disease. Philadelphia, USA: WB Saunders, 2004.Search in Google Scholar

41. Kilani S, Ledauphin J, Bouhlel I, Ben Sghaier M, Boubaker J, Skandrani I, et al. Comparative study of Cyperus rotundus essential oil by a modified GC/MS analysis method. Evaluation of its antioxidant, cytotoxic, and apoptotic effects. Chem Biodivers 2008;5:729–42.10.1002/cbdv.200890069Search in Google Scholar PubMed

42. Cavalcanti B, Ferreira J, Moura D, Rosa RM, Furtado GV, Burbano RR, et al. Structure-mutagenicity relationship of kaurenoic acid from Xylopia sericeae (Annonaceae). Mutat Res 2010;701:153–63.10.1016/j.mrgentox.2010.06.010Search in Google Scholar PubMed

©2015 by De Gruyter

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Characterization of amniotic fluid of Dohne Merino ewes (Ovis aries) and its possible role in neonatal recognition

- Chemical composition, antitumor activity, and toxicity of essential oil from the leaves of Lippia microphylla

- Anti-hyperlipidemic activity of an extract from roots and rhizomes of Panicum repens L. on high cholesterol diet-induced hyperlipidemia in rats

- Feeding stimulants for larvae of Graphium sarpedon nipponum (Lepidoptera: Papilionidae) from Cinnamomum camphora

- Effect of fluoride on the proteomic profile of the hippocampus in rats

- Anti-angiogenic and antiproliferative properties of the lichen substances (-)-usnic acid and vulpinic acid

- Research note

- Fungal biotransformation of crude glycerol into malic acid

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Characterization of amniotic fluid of Dohne Merino ewes (Ovis aries) and its possible role in neonatal recognition

- Chemical composition, antitumor activity, and toxicity of essential oil from the leaves of Lippia microphylla

- Anti-hyperlipidemic activity of an extract from roots and rhizomes of Panicum repens L. on high cholesterol diet-induced hyperlipidemia in rats

- Feeding stimulants for larvae of Graphium sarpedon nipponum (Lepidoptera: Papilionidae) from Cinnamomum camphora

- Effect of fluoride on the proteomic profile of the hippocampus in rats

- Anti-angiogenic and antiproliferative properties of the lichen substances (-)-usnic acid and vulpinic acid

- Research note

- Fungal biotransformation of crude glycerol into malic acid