Abstract

Reaction of 8-bromo-7-ethyl-3-methylxanthine 1 with zerovalent group 10 metal complexes gave via an oxidative addition of the C–Br bond the neutral complexes trans-[2] (M = Pd) and trans-[3] (M = Pt) bearing a theobromine-derived azolato ligand. While the oxidative addition to [Pd0(PPh3)4] gave exclusively trans-[2], the reaction with the more substitution-inert [Pt0(PPh3)4] yielded after 1 day the kinetic product cis-[3], which was converted under heating for a total of 3 days completely into the thermodynamically more stable complex trans-[3]. Treatment of trans-[2], trans-[3] or the mixture of cis-/trans-[3] with the proton source HBF4⋅Et2O led to complexes trans-[4]BF4, trans-[5]BF4 and a mixture of cis/trans-[5]BF4 with retention of the original ratio of cis to trans, respectively. The molecular structures of the azolato complexes trans-[2] and trans-[3] and of the theobromine derived pNHC complexes trans-[4]BF4 and trans-[5]BF4 have been determined by X-ray diffraction studies.

1 Introduction

N-Heterocyclic carbenes (NHCs) featuring two alkyl or aryl substituents at the ring-nitrogen atoms are ubiquitous ligands in organometallic chemistry [1], [2], [3]. The enormous variety of NHC ligands, their different steric and electronic properties and the general stability of the M–CNHC bonds allow for multiple applications of NHCs and their complexes, such as catalysts for selected transformations [4], [5], [6], in metallodrugs [7] or as building blocks in supramolecular assemblies [8], [9]. A modification of the NHC ligand after complex formation is not possible for most complexes bearing NR,NR-substituted NHCs. Such post-synthetic modifications of NHC ligands require, for example, an unsubstituted or protonated ring-nitrogen atom of the diazaheterocycle. Protic NHC ligands (pNHCs) [10], [11], [12] feature one or two protonated ring-nitrogen atoms. Coordinated pNHCs can be deprotonated at the ring-nitrogen atoms. Subsequent N-alkylation leads to new NHC ligands [13], [14]. In addition, complexes bearing a pNHC ligand are potentially suitable for substrate binding and orientation through N–H⋅⋅⋅substrate hydrogen bonds [15], [16], [17], [18].

Generally, access to complexes bearing pNHC ligands is limited [10], [11], [12]. Most pNHC complexes have either been prepared by a template-controlled cyclization of functionalized isocyanides [13] or by the oxidative addition of azoles to complexes of low-valent late transition metals [10], [11], [12]. The oxidative addition protocol can follow two strategies. One method is based on the oxidative addition of the C2–H bond of N-alkylazoles to low-valent transition metal complexes with formation of azolato/hydrido complexes followed by a reductive elimination of a proton from the metal center with protonation of the azolato ligand to the pNHC ligand [10], [11], [12]. This procedure has been employed for the preparation of pNHC complexes of various transition metals such as RhI [19], [20], RuII [21], [22], [23], Fe0 [24], IrI [20] or IrIII [23], [25]. The oxidative addition of neutral azoles is often limited to azoles bearing an N-bound donor, which pre-coordinates to the metal center and thus facilitates the subsequent C2–H oxidative addition [25]. In contrast to the C2–H oxidative addition, the C2–X oxidative addition of 2-halogenoazoles proceeds in the absence of an additional donor function bound to the azole. While first reports of the oxidative addition of azole C2–X bonds by Roper appeared as early as 1973 [26], [27], this procedure has recently received renewed attention [10], [11], [12], [28]. Several complexes bearing protic NH,NH- [14], [29] or NH,NR-NHC ligands [28], [30] have been described. Apart from pNHC ligands obtained from the ubiquitous 2-halogenoimidazole or 2-halogenobenzimidazole NHC precursors [28], [30], protic MIC (MIC = mesoionic carbene) [31], [32] and CAAC ligands [33] are also known. Finally, biomolecules such as 8-halogenocaffeine [29], [34], [35] or -adenine [35], [36] have been employed in oxidative addition reactions to yield complexes with pNHC ligands.

The oxidative addition of 8-halogenocaffeine and -adenine to [Pt(PPh3)4] yielded exclusively the complexes with a trans arrangement of the PPh3 ligands [35], while the oxidative addition of 2-chlorobenzimidazole to Pt0 yielded a mixture of cis- and trans-PPh3 complexes [28]. We became interested in the factors governing the product distribution in the oxidative addition of halogenoazoles to Pd0 and Pt0. Next to the reaction temperature and duration, the type of halogenoazole appears to be a factor. The purine base theobromine is structurally related to caffeine but the electronic situation is slightly different due to a variation in the N-substitution of the pyrimidine ring. In this contribution we present the results obtained from the oxidative addition of a 8-bromotheobromine derivative to Pd0 and Pt0 complexes.

2 Results and discussion

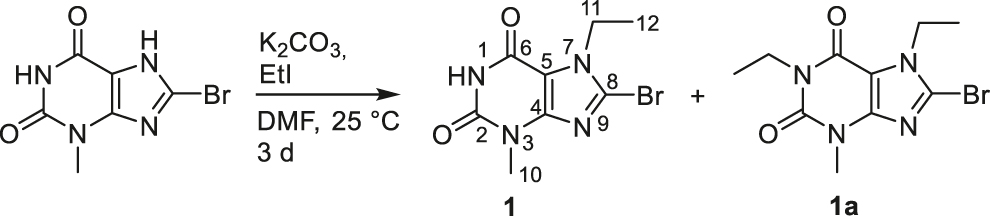

2.1 Synthesis and characterization of 8-bromo-7-ethyl-3-methylxanthine 1

The NHC precursor 8-bromo-7-ethyl-3-methylxanthine 1 was synthesized by alkylation of 8-bromo-3-methylxanthine [37] with 1.1 equivalents of ethyl iodide in the presence of K2CO3 as base (Scheme 1). Next to 1, the formation of the doubly N1,N7 di-alkylated byproduct 1a (ratio 1:1a = 1:0.4) was observed. Compound 1 was separated by column chromatography and isolated in 40% yield.

Synthesis of 8-bromo-7-ethyl-3-methylxanthine 1.

Formation of the ligand precursor 1 was confirmed by NMR spectroscopy, mass spectrometry and by elemental analyses. In the 1H NMR spectrum of 1 the resonances for the CH2 and CH3 groups of the N7 bound ethyl substituent are detected as quartet and triplet at δ = 4.34 and 1.41 ppm, respectively. The characteristic resonances in the 13C{1H} NMR spectrum of 1 are observed at δ = 153.9 (C6), 151.1 (C2) and 127.5 ppm (C8). The resonances of the carbon atoms of the N7 bound ethyl substituent were detected at δ = 43.3 (CH2, C11) and 15.7 ppm (CH3, C12).

2.2 Synthesis and characterization of complexes trans-[2] and trans-[3]

Treatment of [Pd(PPh3)4] with an equimolar amount of 1 in boiling toluene for 3 days yielded complex trans-[2] as a colorless solid in 67% yield. Under identical conditions, ligand precursor 1 reacted with [Pt(PPh3)4] to give the colorless complex trans-[3] in 54% yield (Scheme 2). However, when the reaction time was decreased to one day, complex cis-[3] was isolated instead. Complex cis-[3] is the kinetic product of the oxidative addition reaction of 1 to [Pt(PPh3)4]. After two days reaction time a mixture of cis-[3] and the thermodynamically more stable trans-[3] in a ratio of 1 to 0.54 was observed. After a reaction time of three days, the only observed product was complex trans-[3].

![Scheme 2: Synthesis of PdII complex trans-[2] and PtII complexes cis-/trans-[3].](/document/doi/10.1515/znb-2021-0011/asset/graphic/j_znb-2021-0011_scheme_002.jpg)

Synthesis of PdII complex trans-[2] and PtII complexes cis-/trans-[3].

Both the PdII and the PtII complexes bear a C8-bound negatively charged theobromine-derived azolato ligand with an unsubstituted nitrogen atom. The formation of dinuclear species was not observed, contrary to the results reported for the oxidative addition of 2-halogenated benzimidazole derivatives to zero-valent group 10 metals in the absence of a proton source [28]. The mode of reactivity found for 8-bromotheobromine is in good agreement with the observations made for similar purine bases such as caffeine or other theophylline derivatives [29], [34], [35], [38], where the 8-halogenated derivatives oxidatively add to [Pd(PPh3)4] or [Pt(PPh3)4] leading exclusively to the mononuclear complexes. This observation can be rationalized with the reduced electron density within the five-membered heterocycle due to the electron-withdrawing nature of the annelated ring system together with the steric demand of the azolato ligand [38]. The formation of a cis-configurated platinum(II) complex was not observed previously in the oxidative reaction of halogenated purine bases.

The azolato complexes were characterized by NMR spectroscopy. Interestingly, the resonance for proton H1 (bond to atom N1) in the 1H NMR spectrum was detected at δ = 8.44 (trans-[2]) and 8.28 ppm (trans-[3]). These resonances are shifted up-field compared to the H1 resonance in free 1 (δ = 8.72 ppm), which we attribute to the negative charge of the azolato ligands in the complexes. The other 1H NMR resonances for trans-[2] and trans-[3] fall in the expected range. The 13C{1H} NMR spectra exhibit resonances at δ = 163.7 (t, 2JCP = 3.5 Hz) and 151.7 (t, 2JCP = 9.8 Hz) ppm for the C8 carbon atoms in trans-[2] and (trans-[3]), respectively. As expected, the chemical shift of C8 is shifted significantly upon metal coordination (δ(C8) = 127.5 ppm in 1). The chemical shifts for C8 in trans-[2] and trans-[3] compare well to the chemical shifts reported for the C8 carbon atom in related PdII and PtII complexes bearing a C8-bound xanthine-derived azolato ligand [29], [34], [35]. The triplet resonances observed for C8 in trans-[2] or trans-[3] indicate the trans arrangement of the phosphine donors in these complexes. The trans configuration can also be concluded from the observation of only one resonance in the 31P{1H} NMR spectra at δ = 21.5 ppm (s) for trans-[2] and δ = 18.7 ppm (s, Pt satellites, 1JPPt = 2769 Hz) for trans-[3].

A comparison of the NMR data of the PtII isomers cis-[3] and trans-[3] reveals significant differences. The resonance of the C8 carbon atom in cis-[3] was detected as a doublet of doublets at δ = 167.6 ppm (dd, 2JCP(trans) = 148.9 Hz, 2JCP(cis) = 9.5 Hz) caused by the two chemically different phosphorus atoms. A significant difference between 2JCP(trans) and 2JCP(cis) has previously been reported for related complexes of the type [M(azolato)(PPh3)2(X)] [28]. In addition, the C8 resonance in cis-[3] is shifted significantly downfield compared to the C8 resonance in trans-[3] (δ = 151.7 ppm).

The 31P{1H} NMR spectrum of cis-[3] reveals two resonances at δ = 15.3 ppm (d, 2JPP = 17.9 Hz, Pt satellites 1JPPt = 1973 Hz, PtransPh3) and at δ = 12.6 ppm (d, 2JPPt = 18.0 Hz, Pt satellites 1JPPt = 3970 Hz, PcisPh3). Due to the cis arrangement of the PPh3 ligands in cis-[3], rotation about the Pt–C8 bond is restricted and diastereotopic behavior was observed for the two methylene protons of the N7-bound ethyl substituent leading to two separated resonances for these protons at δ = 4.66 ppm (dq, 2JHH = 14 Hz, 3JHH = 7.1 Hz, 1H, H11a) and δ = 4.13 ppm (dq, 2JHH = 14 Hz, 3JHH = 7.1 Hz, 1 H, H11b).

In addition to NMR spectroscopy, the formation of trans-[2] and trans-[3] was also indicated by HR mass spectrometry (ESI, positive ions). The mass spectra exhibited the peaks of highest intensity for trans-[2] at m/z = 905.0845 (calcd. for [trans-[2]+H]+ 905.0848) and for trans-[3] at m/z = 993.1456 (calcd. 993.1451 for [trans-[3]+H]+).

Crystals of trans-[2]·2CH2Cl2 and trans-[3]·2CH2Cl2 were obtained by slow diffusion of diethyl ether into a saturated dichloromethane solution of the respective complex. The molecular structures of complexes trans-[2] and trans-[3] are depicted in Figure 1.

![Figure 1: Molecular structures of trans-[2] in crystals of trans-[2]·2CH2Cl2 (top) and trans-[3] in crystalline trans-[3]·2CH2Cl2 (bottom).Hydrogen atoms have been omitted for clarity and 50% displace-ment ellipsoids are depicted. Selected bond lengths (Å) and angles (deg) for trans-[2] [trans-[3]]: M–Br 2.4882(3) [2.4943(4)], M–P1 2.3334(6) [2.3169(9)], M–P2 2.3416(6) [2.3241(9)], M–C8 1.980(2) [1.982(3)], N7–C8 1.365(3) [1.366(4)], N9–C8 1.347(3) [1.351(4)]; Br–M–P1 91.080(2) [90.10(3)], Br–M–P2 92.72(2) [91.71(2)], Br–M–C8 176.65(7) [177.38(10)], P1–M–P2 175.19(2) [176.73(3)], P1–M–C8 88.70(6) [89.77(10)], P2–M–C8 87.68(6) [88.54(10)], N7–C8–N9 111.5(2) [111.1(3)].](/document/doi/10.1515/znb-2021-0011/asset/graphic/j_znb-2021-0011_fig_001.jpg)

Molecular structures of trans-[2] in crystals of trans-[2]·2CH2Cl2 (top) and trans-[3] in crystalline trans-[3]·2CH2Cl2 (bottom).

Hydrogen atoms have been omitted for clarity and 50% displace-ment ellipsoids are depicted. Selected bond lengths (Å) and angles (deg) for trans-[2] [trans-[3]]: M–Br 2.4882(3) [2.4943(4)], M–P1 2.3334(6) [2.3169(9)], M–P2 2.3416(6) [2.3241(9)], M–C8 1.980(2) [1.982(3)], N7–C8 1.365(3) [1.366(4)], N9–C8 1.347(3) [1.351(4)]; Br–M–P1 91.080(2) [90.10(3)], Br–M–P2 92.72(2) [91.71(2)], Br–M–C8 176.65(7) [177.38(10)], P1–M–P2 175.19(2) [176.73(3)], P1–M–C8 88.70(6) [89.77(10)], P2–M–C8 87.68(6) [88.54(10)], N7–C8–N9 111.5(2) [111.1(3)].

In both complexes the azolato ligand is oriented essentially perpendicular to the PdBrP2 plane, while the two PPh3 ligands are arranged in the expected trans orientation. The M–C8 bonds lengths (Pd–C8 1.980(2) Å, Pt–C8 1.982(3) Å) are identical within experimental error. However, the M–Br bond lengths are slightly different with the longer one observed for the Pt–Br bond. This order is reversed for the M–P bond lengths, where the shorter distances are observed for the Pt–P bonds. However, all bond lengths and angles involving the metal atoms fall in the range previously described for PdII and PtII complexes bearing xanthine-derived azolato ligands [34], [35], [38].

Notably, and in accord with previous observations [34], [35], [38], the N9–C8 bonds in both complexes (trans-[2] 1.347(3) Å, trans-[3] 1.351(4) Å) are shorter than the N7–C8 bond lengths (1.365(3) and 1.366(4) Å), although the differences in the N–C8 distances (Δd < 0.02 Å) are smaller than the difference in the N–Cazolato bond lengths observed for a Pt-benzimidazolato complex (Δd ≈ 0.07 Å) [39]. The difference in the N–C bond lengths can be attributed to the negative charge at atom N9 which, however, is smaller in the xanthine derived azolato ligands compared to the benzimidazolato ligand due to the electron withdrawing nature of the annelated heterocycles.

While the formation of dinuclear complexes via attack of the unsubstituted azolato ring-nitrogen atom at the metal atom of a second complex molecule was not observed for trans-[2] and trans-[3], these complexes still form dinuclear aggregates via the formation of N1–H⋅⋅⋅O2 hydrogen bonds (Figure 2). Related hydrogen bonds have been observed in azolate complexes obtained by oxidative addition of 8-halogenoguanosine derivatives to [Pd(PPh3)4] [36].

![Figure 2: Hydrogen bonds between two molecules of trans-[2] (top) and trans-[3] (bottom) in the crystal structures of trans-[2]·2CH2Cl2 and trans-[3]·2CH2Cl2, respectively. Displacement ellipsoids are drawn at the 50% probability level. Hydrogen atoms except for H1 have been omitted for clarity. Selected bond lengths (Å) and angles (deg) for trans-[2] [trans-[3]]: O2⋅⋅⋅N1 2.828 [2.821], O2⋅⋅⋅H–N1 169.7 [168.2].](/document/doi/10.1515/znb-2021-0011/asset/graphic/j_znb-2021-0011_fig_002.jpg)

Hydrogen bonds between two molecules of trans-[2] (top) and trans-[3] (bottom) in the crystal structures of trans-[2]·2CH2Cl2 and trans-[3]·2CH2Cl2, respectively. Displacement ellipsoids are drawn at the 50% probability level. Hydrogen atoms except for H1 have been omitted for clarity. Selected bond lengths (Å) and angles (deg) for trans-[2] [trans-[3]]: O2⋅⋅⋅N1 2.828 [2.821], O2⋅⋅⋅H–N1 169.7 [168.2].

2.3 Synthesis and characterization of complexes trans-[4]BF4 and trans-[5]BF4

Treatment of complexes trans-[2] and trans-[3] with HBF4·Et2O yielded complexes trans-[4]BF4 and trans-[5]BF4 in reasonable yields via protonation of the N9 ring-nitrogen atom (Scheme 3). Thus complexes trans-[4]BF4 and trans-[5]BF4 bear a theobromine-derived pNHC ligand. Interestingly, these complexes cannot be prepared in a one-pot reaction by treating the C8-halogenated xanthine derivative with [M(PPh3)4] in the presence of a mild acid such as NH4BF4 [28], [29]. This difference in reactivity can be attributed to the electron withdrawing theobromine system, which leads for complexes trans-[2] and trans-[3] to a decreased basicity of the unsubstituted ring-nitrogen atom of the azolato ligand.

![Scheme 3: Synthesis of the PdII and PtII complexes trans-[4]BF4 and trans-[5]BF4.](/document/doi/10.1515/znb-2021-0011/asset/graphic/j_znb-2021-0011_scheme_003.jpg)

Synthesis of the PdII and PtII complexes trans-[4]BF4 and trans-[5]BF4.

The NMR spectra of trans-[4]BF4 and trans-[5]BF4 are similar to those of the parent azolato complexes trans-[2] and trans-[3], respectively. The only exceptions are the resonances at δ = 11.25 (trans-[4]BF4) and δ = 10.41 ppm (trans-[5]BF4) in the 1H NMR spectra for the NH protons of the pNHC ligands. The 13C{1H} NMR spectra exhibit the resonances of the carbene carbon atom C8 as triplet at δ = 164.9 ppm (2JCP = 9.4 Hz) and at δ = 151.7 ppm (2JCP = 10.1 Hz) for trans-[4]BF4 and trans-[5]BF4, respectively. These chemical shifts are close to those observed for the C8 carbon atoms of the parent complexes trans-[2] (δ = 163.7 ppm) and trans-[3] (δ = 151.7 ppm). The 31P{1H} NMR spectra of both complexes exhibit the resonances of the two chemically equivalent phosphorus atoms as singlets at δ = 21.0 ppm (trans-[4]BF4) and δ = 16.6 ppm (trans-[5]BF4). In addition, for trans-[5]BF4, Pt satellites were observed (1JPPt = 2464 Hz). Interestingly, the 1JPPt coupling constant in cationic trans-[5]+ is smaller than that in neutral trans-[3] (1JPPt = 2769 Hz). A similar trend in the coupling constant upon the transition from the azolato to the pNHC complexes has been observed for trans-PtII complexes bearing caffeine-derived NHC ligands [35]. A triplet was observed in the 195Pt{1H} NMR spectrum of trans-[5]BF4 at δ = −4500.4 ppm (1JPPt = 2464 Hz). HR mass spectrometry (ESI, positive ions) showed the strongest peaks for the cation trans-[4]+ at m/z = 905.0842 (calcd. 905.0848 for [trans-[4]]+) and for trans-[5]+ at m/z = 993.1445 (calcd. 993.1451 for [trans-[5]]+).

The composition and geometry of trans-[4]BF4 and trans-[5]BF4 were verified by X-ray diffraction studies with crystals of composition trans-[4]BF4 and trans-[5]BF4·Et2O, respectively. The asymmetric unit of trans-[4]BF4 contains two essentially identical formula units. Only one of the complex cations in the asymmetric unit of trans-[4]+ is depicted in Figure 3 (top) together with the complex cation of trans-[5]+ (bottom).

![Figure 3: Molecular structures of one of the two independent complex cations trans-[4]+ (top) in trans-[4]BF4 and of trans-[5]+ (bottom) in trans-[5]BF4·Et2O. Hydrogen atoms except for H9 have been omitted for clarity and displacement ellipsoids are drawn at the 50% probability level. Selected bond lengths (Å) and angles (deg) of cation trans-[4]+ [trans-[5]+]: M–Br 2.4602(4) [2.4685(4)], M–P1 2.3627(9) [2.3233(9)], M–P2 2.3212(9) [2.3155(9)], M–C8 1.988(3) [1.982(3)], N7–C8 1.338(4) [1.340(5)], N9–C8 1.361(4) [1.352(4)]; Br–M–P1 89.56(2) [90.22(2)], Br–M–P2 88.08(2) [89.61(2)], Br–M–C8 176.48(10) [177.28(10)], P1–M–P2 177.46(3) [171.66(3)], P1–M–C8 93.91(10) [89.42(10)], P2–M–C8 88.46(10) [91.14(10)], N7–C8–N9 106.9(3) [107.2(3)].](/document/doi/10.1515/znb-2021-0011/asset/graphic/j_znb-2021-0011_fig_003.jpg)

Molecular structures of one of the two independent complex cations trans-[4]+ (top) in trans-[4]BF4 and of trans-[5]+ (bottom) in trans-[5]BF4·Et2O. Hydrogen atoms except for H9 have been omitted for clarity and displacement ellipsoids are drawn at the 50% probability level. Selected bond lengths (Å) and angles (deg) of cation trans-[4]+ [trans-[5]+]: M–Br 2.4602(4) [2.4685(4)], M–P1 2.3627(9) [2.3233(9)], M–P2 2.3212(9) [2.3155(9)], M–C8 1.988(3) [1.982(3)], N7–C8 1.338(4) [1.340(5)], N9–C8 1.361(4) [1.352(4)]; Br–M–P1 89.56(2) [90.22(2)], Br–M–P2 88.08(2) [89.61(2)], Br–M–C8 176.48(10) [177.28(10)], P1–M–P2 177.46(3) [171.66(3)], P1–M–C8 93.91(10) [89.42(10)], P2–M–C8 88.46(10) [91.14(10)], N7–C8–N9 106.9(3) [107.2(3)].

The major differences in the metric parameters of the pNHC complex cations trans-[4]+ and trans-[5]+ relative to the parent azolato complexes trans-[2] and trans-[3] were observed in the five-membered diazaheterocycles. While the M–C8 bond lengths in the pNHC complexes are identical within experimental error (trans-[4]BF4 1.988(3) Å, trans-[5]BF4 1.982(3) Å), they are also unchanged from the bond lengths in the neutral azolato complexes (trans-[2] 1.980(2) Å and trans-[3] 1.982(3) Å). A significant change was observed for the N–C8 bonds upon N9 protonation. While the azolato complexes trans-[2] and trans-[3] (Figure 1) feature shorter N9–C8 and longer N7–C8 bonds, the protonation to trans-[4]BF4 and trans-[5]BF4 leads to almost identical N–C8 separations. Even more significant is the reduction of the N7–C8–N9 angle upon N9 protonation (trans-[4]BF4 106.9(3)°, trans-[5]BF4 107.2(3)°) compared to the azolato complexes (trans-[2] 111.5(2)°, trans-[3] 111.1(3)°) which is in accord with previous observations [34], [35].

The crystal structure of trans-[4]BF4 reveals two hydrogen bond interactions of the complex cation with two BF4− anions via the N9–H and N1–H groups (distances N9⋅⋅⋅F3 2.725 Å, N1⋅⋅⋅F2 2.842 Å), leading to chains of cations in the solid state (Figure 4). For trans-[5]BF4⋅Et2O the N1–H proton interacts with the co-crystallized diethyl ether molecule (distance N1⋅⋅⋅O 3.054 Å).

![Figure 4: Intermolecular interactions in the crystal structure of trans-[4]BF4. Displacement ellipsoids are drawn at the 50% probability level. Hydrogen atoms, except for N1–H and N9–H, have been omitted for clarity. Selected hydrogen bond lengths (Å): N9⋅⋅⋅F3 2.725 Å, N1⋅⋅⋅F2 2.878 Å.](/document/doi/10.1515/znb-2021-0011/asset/graphic/j_znb-2021-0011_fig_004.jpg)

Intermolecular interactions in the crystal structure of trans-[4]BF4. Displacement ellipsoids are drawn at the 50% probability level. Hydrogen atoms, except for N1–H and N9–H, have been omitted for clarity. Selected hydrogen bond lengths (Å): N9⋅⋅⋅F3 2.725 Å, N1⋅⋅⋅F2 2.878 Å.

2.4 Synthesis and characterization of a mixture of platinum complexes cis/trans-[5]BF4

The mixture of complexes cis-/trans-[3] (1: 0.54, obtained after 2 days reaction time, Scheme 2) was suspended in THF and HBF4⋅Et2O was added dropwise (Scheme 4). This led to the formation of a mixture of complexes cis-/trans-[5]BF4, which was isolated in a total yield of 50%. The coexistence of both complexes as well as a constant ratio of complexes (cis-[5]BF4:trans-[5]BF4 = 1:0.54) was confirmed by NMR spectroscopy.

![Scheme 4: Synthesis of cis-/trans-[5]BF4.](/document/doi/10.1515/znb-2021-0011/asset/graphic/j_znb-2021-0011_scheme_004.jpg)

Synthesis of cis-/trans-[5]BF4.

As was observed for the azolato complex cis-[3], the NMR data of the pNHC complex cis-[5]BF4 differ from those of the trans-isomer. Generally, the resonances assigned to cis-[5]BF4 in the 1H NMR spectrum of the mixture are observed more downfield shifted than those belonging to the trans-complex. In addition, the rotation about the Pt–C8 bond in cis-[5]BF4 is hindered leading to diastereotopic methylene protons detected as two doublets of quartets at δ = 4.58 ppm (2JHH = 14 Hz, 3JHH = 7.1 Hz) and at δ = 4.21 ppm (2JHH = 14 Hz, 3JHH = 7.1 Hz). In the 13C{1H} NMR spectrum of the complex mixture, the resonances of the carbene carbon atoms are well separated. While the resonance for the carbon atom C8 of trans-[5]BF4 was detected as a triplet at δ = 151.7 ppm (2JCP = 10.1 Hz), the C8 resonance of the cis-isomer was observed more downfield as a doublet of doublets at δ = 164.6 ppm (2JCP(trans) = 145.4 Hz, 2JCP(cis) = 9.6 Hz). The resonance of C8 in cis-[5]BF4 is slightly upfield shifted compared to the C8 resonance in the azolato complex cis-[3] (δ = 167.6 ppm). The resonances of the two chemically non-equivalent phosphorus atoms were detected as doublets at δ = 13.1 ppm (Ptrans) and 11.0 ppm (Pcis) both featuring an identical 2JPP = 18.9 Hz coupling constant and the characteristic platinum satellites (1JPPt = 2286 Hz, Ptrans and 3652 Hz Pcis) in the 31P{1H} NMR spectrum of cis-[5]BF4. These resonances are slightly upfield from the corresponding resonances in cis-[3]. The 195Pt NMR spectrum of the mixture of isomers exhibits a triplet at δ = −4500.4 ppm (1JPPt = 2464 Hz) for trans-[5]BF4 and a doublet of doublets at δ = −4602.9 ppm (1JPtP(cis) = 3652, 1JPtP(trans) = 2286 Hz) for cis-[5]BF4.

3 Conclusion

We have prepared novel PdII and PtII complexes trans-[2] and trans-[3] bearing a theobromine-derived azolato ligand obtained by the oxidative addition of 8-bromo-N7-ethyl-3-methyl-xanthine 1 to [M0(PPh3)4] (M = Pd, Pt) followed by protonation at their N9 positions to give the pNHC complexes trans-[4]BF4 and trans-[5]BF4. The azolato complexes trans-[2] and trans-[3] were obtained as the only reaction products after a reaction time of 3 days in boiling toluene. For the reaction of [Pt(PPh3)4] with 1, the effect of a reduction of the reaction time was studied revealing that after only 1 day the isomer cis-[3] was the exclusive reaction product, while after 2 days reaction time a mixture of the cis/trans isomers was obtained in a ratio of 1:0.54. N9-Protonation of trans-[2], trans-[3] or the mixture of cis-/trans-[3] (1:0.54) with HBF4⋅Et2O yielded in all cases the complexes bearing the protic theobromine-derived NHC ligand. X-ray diffraction structure determinations revealed for complexes trans-[2] and trans-[3] an intermolecular interaction between two molecules via N1–H⋅⋅⋅O2 hydrogen bonds. The pNHC complexes trans-[4]BF4 and trans-[5]BF4·Et2O featured N9–H⋅⋅⋅F–BF2–F⋅⋅⋅H–N1 (trans-[4]BF4) or N1–H⋅⋅⋅OEt2 (trans-[5]BF4·Et2O) hydrogen bonds involving the BF4− anions or the co-crystallized diethyl ether.

4 Experimental section

4.1 General remarks

All manipulations were carried out in an argon atmosphere using standard Schlenk or glovebox techniques. Solvents were dried by standard methods under argon and were freshly distilled prior to use. 1H, 13C{1H} and 31P{1H} NMR spectra were measured on a Bruker AVANCE I 400 or a Bruker AVANCE III 400 spectrometer. Chemical shifts (δ) are expressed in ppm using the residual protonated solvent signal as internal standard. Coupling constants are expressed in Hertz. Mass spectra were obtained with a Bruker Reflex IV MALDI TOF or an Orbitrap LTQ XL (Thermo Scientific) spectrometer. Elemental analyses were obtained on a Vario EL III CHNS analyzer. The 8-bromo-3-methylxanthine and the metal precursors [M0(PPh3)4] (M = Pd, Pt) were purchased from commercial sources and were used as received.

4.2 8-Bromo-7-ethyl-3-methylxanthine (1)

8-Bromo-3-methylxanthine (1.200 g, 4.90 mmol) and an excess of potassium carbonate (843 mg, 6.10 mmol) were suspended in DMF (15 mL). Ethyl iodide (0.44 mL, 5.48 mmol) was added to this suspension and the reaction mixture was stirred for 3 days at ambient temperature. The yellowish suspension was poured into ice-cold water (100 mL) and stirred for 1 h at 0 °C. The formed precipitate was isolated by filtration, washed with water and dried in vacuo. The residue was purified by column chromatography (SiO2, CH2Cl2:MeOH 100:5) to give 1 after drying in vacuo as a colorless solid. Yield: 535 mg (1.96 mmol, 40%). – 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD2Cl2, ppm): δ = 8.72 (s, 1 H, H1), 4.34 (q, 3JHH = 7.1 Hz, 2 H, H11), 3.47 (s, 3 H, H10), 1.41 (t, 3JHH = 7.1 Hz, 3 H, H12). – 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CD2Cl2, ppm): δ = 153.9 (C6), 151.1 (C2), 150.6 (C4), 127.5 (C8), 109.2 (C5), 43.3 (C11), 29.3 (C10), 15.7 (C12). – MS (MALDI, DHB): m/z = 274, 272 [1+H]+. – C8H9BrN4O2 (273.09 g mol−1): calcd. C 35.18, H 3.32, N 20.52; found C 35.26, H 3.42, N 20.51.

4.3 General procedure for the synthesis of trans-[2] and trans-[3]

Equimolar amounts of compound 1 (66 mg, 0.24 mmol) and [M(PPh3)4] (0.24 mmmol, M = Pd, Pt) were dissolved in toluene (10 mL) and stirred for three days under reflux. The solvent was then removed under reduced pressure and the residue washed twice each with hexane (10 mL each) and diethyl ether (10 mL each). After drying in vacuo the trans-configurated complexes were obtained as colorless solids. Crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction studies were obtained by slow diffusion of diethyl ether into saturated dichloromethane solutions of the complexes.

4.3.1 Analytical data for trans-[2]

Yield: 144 mg (0.16 mmol, 67%). – 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD2Cl2, ppm): δ = 8.44 (s, 1 H, H1), 7.62−7.57 (m, 12 H, Ph-Hortho), 7.43 (t, 3JHH = 7.3 Hz, 6 H, Ph-Hpara), 7.34 (t, 3JHH = 7.3 Hz, 12 H, Ph-Hmeta), 3.83 (q, 3JHH = 7.1 Hz, 2 H, H11), 3.09 (s, 3 H, H10), 0.97 (t, 3JHH = 7.1 Hz, 3 H, H12). – 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CD2Cl2, ppm): δ = 163.7 (t, 2JCP = 3.5 Hz, C8), 153.9 (C6), 152.8 (C2), 151.4 (C4), 135.0 (v-t, 2/4JCP = 6.6 Hz, Ph-Cortho), 131.0 (Ph-Cpara), 130.9 (v-t, 1/3JCP = 24.3 Hz, Ph-Cipso), 128.6 (v-t, 3/5JCP = 5.6 Hz, Ph-Cmeta), 109.8 (C5), 43.9 (C11), 28.7 (C10), 15.9 (C12). – 31P{1H} NMR (162 MHz, CD2Cl2, ppm): δ = 21.5 (s). – HRMS ((+)-ESI): m/z = 905.0845 (calcd. 905.0848 for C44H40BrN4O2P2Pd, [trans-[2]+H]+), 927.06615 (calcd. 927.0668 for C44H39BrN4O2P2PdNa, [trans-[2]+Na]+). – C44H39N4BrO2P2Pd (904.03 g mol−1): calcd. C 58.45, H 4.35, N 6.20; found C 56.72, H 4.40, N 5.96.

4.3.2 Analytical data for trans-[3]

Yield: 134 mg (0.13 mmol, 54%). – 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD2Cl2, ppm): δ = 8.28 (s, 1 H, H1), 7.63−7.58 (m, 12 H, Ph-Hortho), 7.45−7.42 (m, 6 H, Ph-Hpara), 7.36−7.33 (m, 12 H, Ph-Hmeta), 3.81 (q, 3JHH = 7.1 Hz, 2 H, H11), 3.08 (s, 3 H, H10), 0.92 (t, 3JHH = 7.1 Hz, 3 H, H12). – 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CD2Cl2, ppm): δ = 153.6 (C6), 152.9 (C2), 151.7 (t, 2JCP = 9.8 Hz, C8), 151.2 (C4), 135.0 (v-t, 2/4JCP = 6.1 Hz, Ph-Cortho), 131.1 (Ph-Cpara), 130.1 (v-t, 1/3JCP = 29.0 Hz, Ph-Cipso), 128.5 (v-t, 3/5JCP = 5.3 Hz, Ph-Cmeta), 108.3 (C5), 43.7 (C11), 28.7 (C10), 15.7 (C12). – 31P{1H} NMR (162 MHz, CD2Cl2, ppm): δ = 18.7 (s, Pt satellites, 1JPPt = 2769 Hz). – HRMS ((+)-ESI): m/z = 993.1456 (calcd. 993.1451 for C44H40BrN4O2P2Pt, [trans-[3]+H]+).

4.4 Complex cis-[3]

A solution of 1 (12.4 mg, 0.05 mmol) and [Pt(PPh3)4] (56.5 mg, 0.05 mmol) in toluene (10 mL) was stirred for one day at 110 °C. The solvent was then removed under reduced pressure and the residue was washed twice with hexane (5 mL each) and diethyl ether (5 mL each). After drying in vacuo compound cis-[3] was obtained as a colorless solid. Yield: 20 mg (0.02 mmol, 40%). – 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD2Cl2-CD3OD, ppm): δ = 7.48−7.39 (m, 12 H, Ph-Hortho), 7.34−7.28 (m, 6 H, Ph-Hpara), 7.21−7.12 (m, 12 H, Ph-Hmeta), 4.66 (dq, 2JHH = 14 Hz, 3JHH = 7.1 Hz, 1 H, H11a), 4.13 (dq, 2JHH = 14 Hz, 3JHH = 7.1 Hz, 1 H, H11b), 3.24 (s, 3 H, H10), 1.56 (t, 3JHH = 7.1 Hz, 3 H, H12). The proton H1 was not detected due to H/D-exchange with the solvent CD3OD. – 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CD2Cl2-CD3OD, ppm): δ = 167.6 (dd, 2JCP(trans) = 148.9 Hz, 2JCP(cis) = 9.5 Hz, C8), 154.0 (C6), 153.0 (d, 4JCP(trans) = 10.2 Hz, C4), 151.7 (C2), 135.7 (d, 2JCP = 10.4 Hz, PtransPh3, Ph-Cortho), 134.4 (d, 2JCP = 11.2 Hz, PcisPh3, Ph-Cortho), 131.4 (d, 4JCP = 2.2 Hz, PcisPh3, Ph-Cpara), 130.9 (d, 4JCP = 2.2 Hz, PtransPh3, Ph-Cpara), 129.5 (dd, 1JCP = 63.0 Hz, 2JCP = 1.5 Hz, PtransPh3, Ph-Cipso), 128.6 (d, 3JCP = 11.3 Hz, PcisPh3, Ph-Cmeta), 128.5 (d, 3JCP = 10.4 Hz, PtransPh3, Ph-Cmeta), 108.7 (d, 4JCP(trans) = 4.0 Hz, C5), 44.3 (C11), 30.1 (C10), 15.7 (C12). The signal for Cipso of PcisPh3 was not detected. – 31P{1H} NMR (162 MHz, CD2Cl2-CD3OD, ppm): δ = 15.3 (d, 2JPP = 17.9 Hz, Pt satellites 1JPPt = 1973 Hz, PtransPh3), 12.6 (d, 2JPP = 18.0 Hz, Pt satellites 1JPPt = 3970 Hz, PcisPh3).

4.5 General procedure for the synthesis of complexes trans-[4]BF4 and trans-[5]BF4

Samples of complexes trans-[2] or trans-[3] (0.07 mmol) were suspended in THF (5 mL) and an excess of HBF4·Et2O (0.030 mL, 0.22 mmol) was added dropwise to the stirred suspension. The reaction mixture was stirred for 1 h at ambient temperature, while the suspension became a clear solution. The solvent was then removed under reduced pressure and the residue was washed twice with diethyl ether (10 mL each). After drying of the residue in vacuo the pNHC complexes were obtained as colorless solids. Crystals of trans-[4]BF4 and trans-[5]BF4 suitable for X-ray diffraction experiments were obtained by slow diffusion of Et2O into a saturated acetonitrile-methanol or acetonitrile solution of the individual complexes.

4.5.1 Analytical data for trans-[4]BF4

Yield: 57% (40 mg, 0.04 mmol). – 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3CN-CD3OD, ppm): δ = 11.25 (s, 1 H, H9), 9.90 (s, 1 H, H1), 7.66 (m, 12 H, Ph-Hortho), 7.54 (t, 3JHH = 7.3 Hz, 6 H, Ph-Hpara), 7.47 (t, 3JHH = 7.3 Hz, 12 H, Ph-Hmeta), 3.99 (q, 3JHH = 7.2 Hz, 2 H, H11), 2.92 (s, 3 H, H10), 0.96 (t, 3JHH = 7.2 Hz, 3 H, H12). – 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CD3CN-CD3OD, ppm): δ = 164.9 (t, 2JCP = 9.4 Hz, C8), 152.9 (C6), 149.8 (C2), 144.8 (C4), 135.6 (v-t, 2/4JCP = 6.3 Hz, Ph-Cortho), 130.5 (Ph-Cpara), 130.2 (v-t, 1/3JCP = 25.7 Hz, Ph-Cipso), 130.1 (v-t, 3/5JCP = 5.4 Hz, Ph-Cmeta), 109.5 (C5), 48.1 (C11), 30.7 (C10), 15.7 (C12). – 31P{1H} NMR (162 MHz, CD3CN-CD3OD, ppm): δ = 21.0 (s). – HRMS ((+)-ESI): m/z = 905.0842 (calcd. 905.0848 for C44H40N4BrO2P2Pd, [trans-[4]]+).

4.5.2 Analytical data for trans-[5]BF4

Yield: 43% (28 mg, 0.03 mmol). – 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3CN, ppm): δ = 10.41 (s, 1 H, H9), 8.98 (s, 1 H, H1), 7.70−7.68 (d, 3JHH = 7.3 Hz, 12 H, Ph-Hortho), 7.57−7.54 (m, 6 H, Ph-Hpara), 7.51–7.48 (m, 12 H, Ph-Hmeta), 3.99 (q, 3JHH = 7.0 Hz, 2 H, H11), 2.91 (s, 3 H, H10), 0.97 (t, 3JHH = 7.1 Hz, 3 H, H12). – 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CD3CN, ppm): δ = 152.7 (C6), 151.7 (t, 2JCP = 10.1 Hz, C8), 149.5 (C2), 143.8 (C4), 135.5 (v-t, 2/4JCP = 6.1 Hz, Ph-Cortho), 132.9 (Ph-Cpara), 129.9 (v-t, 3/5JCP = 5.4 Hz, Ph-Cmeta), 129.3 (v-t, 1/3JCP = 29.8 Hz, Ph-Cipso), 108.3 (C5), 47.6 (C11), 30.7 (C10), 15.3 (C12). – 31P{1H} NMR (162 MHz, CD3CN, ppm): δ = 16.6 (s, Pt satellites 1JPPt = 2464 Hz). – 195Pt NMR (86 MHz, CD3CN, ppm): δ = −4500.4 (t, 1JPPt = 2464 Hz). – HRMS ((+)-ESI): m/z = 993.1445 (calcd. 993.1451 for C44H40N4BrO2P2Pt, [trans-[5]]+).

4.6 Complex mixture cis-/trans-[5]BF4

A mixture of cis-[3]/trans-[3] in the ratio of 1:0.54 (95 mg, 0.10 mmol) was suspended in THF (5 mL) and an excess of HBF4·Et2O (0.030 mL, 0.22 mmol) was added under stirring to the suspension. The reaction mixture became a clear solution while stirring at ambient temperature for 1 h. After removal of the solvent under reduced pressure, the obtained solid was washed twice with diethyl ether (10 mL each) and dried in vacuo. The obtained colorless mixture of cis-/trans-[5]BF4 exhibited the same ratio of cis- and trans-isomer as observed for the starting material. Yield: 50 mg (0.05 mmol, 50%). Analytical data assigned to trans-[5] in the mixture are identical to those of a pure sample of trans-[5]BF4 (see above). Therefore, only data for cis-[5]BF4 are listed here. – 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3CN, ppm): δ = 11.01 (s, 1 H, H9), 9.02 (s, 1 H, H1), 7.55−7.49 (m, 12 H, Ph-Hortho of PcisPh3 and PtransPh3), 7.55−7.42 (m, 18 H, Ph-Hpara/meta), 4.58 (dq, 2JHH = 14 Hz, 3JHH = 7.1 Hz, 1 H, H11a), 4.21 (dq, 2JHH = 14 Hz, 3JHH = 7.1 Hz, 1 H, H11b), 3.26 (s, 3 H, H10), 1.55 (t, 3JHH = 7.1 Hz, 3 H, H12). – 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CD3CN, ppm): δ = 164.6 (dd, 2JCP(trans) = 145.4 Hz, 2JCP(cis) = 9.6 Hz, C8), 153.2 (C6), 150.0 (C2), 144.2 (d, 4JCP(trans) = 5.8 Hz, C4), 136.3 (d, 2JCP = 10.2 Hz, Ph-Cortho, PtransPh3), 134.9 (d, 2JCP = 11.2 Hz, Ph-Cortho, PcisPh3), 133.1 (d, 4JCP = 2.1 Hz, Ph-Cpara, PcisPh3), 132.2 (d, 4JCP = 2.0 Hz, Ph-Cpara, PtransPh3), 130.0−129.9 (m, Ph-Cmeta, PcisPh3), 29.3 (d, 3JCP = 10.7 Hz, Ph-Cmeta, PtransPh3), 108.5 (d, 4JCP(trans) = 4.0 Hz, C5), 47.4 (C11), 30.9 (C10), 15.2 (C12). The signals for Cipso of the PPh3 ligands were not detected. – 31P{1H} NMR (162 MHz, CD3CN, ppm): δ = 13.1 (d, 2JPP = 18.9 Hz, Pt satellites 1JPPt = 2286 Hz, PtransPh3), 11.0 (d, 2JPP = 18.9 Hz, Pt satellites 1JPPt = 3652 Hz, PcisPh3). – 195Pt NMR (86 MHz, CD3CN, ppm): δ = −4602.9 (dd, 1JP(cis)Pt = 3652 Hz, 1JP(trans)Pt = 2286 Hz). – MS ((+)-ESI): m/z = 993.1445 (calcd. 993.1451 for [cis-/trans-[5]]+).

4.7 X-ray structure determinations

Diffraction data for all compounds were collected with a Bruker APEX-II CCD diffractometer equipped with a micro source using MoKα radiation (λ = 0.71073 Å). Diffraction data was collected at T = 100(2) K over the full sphere and was corrected for absorption. Structure solutions were found with the Shelxt (intrinsic phasing) [40] package (intrinsic phasing) using direct methods and were refined with Shelxl [41] against all |F2| using first isotropic and later anisotropic displacement parameters (for exceptions see description of the individual molecular structures). Hydrogen atoms were added to the structure models on calculated positions if not noted otherwise.

4.7.1 Selected crystallographic details for trans-[2]·2CH2Cl2

Formula C46H43N4BrCl4O2P2Pd, M = 1073.89 g·mol−1, colorless block, 0.50 × 0.44 × 0.44 mm3, triclinic, space group

4.7.2 Selected crystallographic details for trans-[3]·2CH2Cl2

Formula C46H43N4BrCl4O2P2Pt, M = 1162.58 g·mol−1, colorless block, 0.35 × 0.30 × 0.27 mm3, triclinic, space group

4.7.3 Selected crystallographic details for trans-[4]BF4

Formula C44H40N4BBrF4O2P2Pd, M = 991.86 g·mol−1, colorless block, 0.20 × 0.06 × 0.06 mm3, triclinic, space group

4.7.4 Selected crystallographic details for trans-[5]BF4·C4H10O

Formula C48H50N4BBrF4O3P2Pt, M = 1154.67 g·mol−1, colorless needle, 0.46 × 0.17 × 0.04 mm3, triclinic, space group

Further details of the crystal structure investigation may be obtained from Fachinformationszentrum Karlsruhe, 76344 Eggenstein-Leopoldshafen, Germany (fax: +49-7247-808-666; e-mail: crysdata@fiz-karlsruhe.de, http://www.fiz-informationsdienste.de/en/DB/icsd/depot_anforderung.html) on quoting the deposition number CCDC 2058003 (trans-[2]·2CH2Cl2), CCDC 2058004 (trans-[3]·2CH2Cl2), CCDC 20058006 (trans-[4]BF4) and CCDC 2058005 (trans-[5]BF4·C4H10O).

Funding source: Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft

Award Identifier / Grant number: SFB 858 and IRTG 2027

Author contributions: All the authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this submitted manuscript and approved submission.

Research funding: This research was funded by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB 858 and IRTG 2027).

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding this article.

References

1. Hahn, F. E., Jahnke, M. C. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 3122–3172; https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.200703883.Suche in Google Scholar

2. Jahnke, M. C., Hahn, F. E. Top. Organomet. Chem. 2010, 30, 95–129; https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-04722-0_4.Suche in Google Scholar

3. Hopkinson, M. N., Richter, C., Schedler, M., Glorius, F. Nature 2014, 510, 485–496; https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13384.Suche in Google Scholar

4. Janssen-Müller, D., Schlepphorst, C., Glorius, F. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 4845–4854; https://doi.org/10.1039/c7cs00200a.Suche in Google Scholar

5. Mata, J. A., Hahn, F. E., Peris, E. Chem. Sci. 2014, 5, 1723–1732; https://doi.org/10.1039/c3sc53126k.Suche in Google Scholar

6. Peris, E. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 9988–10031; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00695.Suche in Google Scholar

7. Liu, W., Gust, R. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2016, 329, 191–213; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccr.2016.09.004.Suche in Google Scholar

8. Sinha, N., Hahn, F. E. Acc. Chem. Res. 2017, 50, 2167–2184; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.accounts.7b00158.Suche in Google Scholar

9. Gan, M.-M., Liu, J.-Q., Zhang, L., Wang, Y.-Y., Hahn, F. E., Han, Y.-F. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 9587–9641; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00119.Suche in Google Scholar

10. Jahnke, M. C., Hahn, F. E. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2015, 293-294, 95–115; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccr.2015.01.014.Suche in Google Scholar

11. Jahnke, M. C., Hahn, F. E. Chem. Lett. 2015, 44, 226–237; https://doi.org/10.1246/cl.141052.Suche in Google Scholar

12. Kuwata, S., Hahn, F. E. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 9642–9677; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00176.Suche in Google Scholar

13. Edwards, P. G., Hahn, F. E. Dalton Trans. 2011, 40, 10278–10288; https://doi.org/10.1039/c1dt10864f.Suche in Google Scholar

14. Das, R., Hepp, A., Daniliuc, C. G., Hahn, F. E. Organometallics 2014, 33, 6975–6987; https://doi.org/10.1021/om501120u.Suche in Google Scholar

15. Meier, N., Hahn, F. E., Pape, T., Siering, C., Waldvogel, S. R. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2007, 1210–1214; https://doi.org/10.1002/ejic.200601258.Suche in Google Scholar

16. Miranda-Soto, V., Grotjahn, D. B., DiPasquale, A. G., Rheingold, A. L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 13200–13201; https://doi.org/10.1021/ja804713u.Suche in Google Scholar

17. Marelius, D. C., Darrow, E. H., Moore, C. E., Golen, J. A., Rheingold, A. L., Grotjahn, D. B. Chem. Eur J. 2015, 21, 10988–10992; https://doi.org/10.1002/chem.201501945.Suche in Google Scholar

18. Hahn, F. E. ChemCatChem 2013, 5, 419–430; https://doi.org/10.1002/cctc.201200567.Suche in Google Scholar

19. Tan, K. L., Bergman, R. G., Ellman, J. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 3202–3203; https://doi.org/10.1021/ja017351d.Suche in Google Scholar

20. He, F., Wesolek, M., Danopoulos, A. A., Braunstein, P. Chem. Eur J. 2016, 22, 2658–2671; https://doi.org/10.1002/chem.201504030.Suche in Google Scholar

21. Price, C., Elsegood, M. R. J., Clegg, W., Rees, N. H., Houlton, A. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1997, 36, 1762–1764; https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.199717621.Suche in Google Scholar

22. Flowers, S. E., Johnson, M. C., Pitre, B. Z., Cossairt, B. M. Dalton Trans. 2018, 47, 1276–1283; https://doi.org/10.1039/c7dt04333c.Suche in Google Scholar

23. Brackemeyer, D., Schulte to Brinke, C., Roelfes, F., Hahn, F. E. Dalton Trans. 2017, 46, 4510–4513; https://doi.org/10.1039/c7dt00682a.Suche in Google Scholar

24. Mühlen, C., Linde, J., Rakers, R., Tan, T. T. Y., Kampert, F., Glorius, F., Hahn, F. E. Organometallics 2019, 38, 2417–2421; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.organomet.9b00260.Suche in Google Scholar

25. Cepa, S., Schulte to Brinke, C., Roelfes, F., Hahn, F. E. Organometallics 2015, 34, 5454–5460; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.organomet.5b00799.Suche in Google Scholar

26. Fraser, P. J., Roper, W. R., Stone, F. G. A. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 1974, 102–105.10.1039/dt9740000102Suche in Google Scholar

27. Fraser, P. J., Roper, W. R., Stone, F. G. A. J. Organomet. Chem. 1973, 50, C54–C56; https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-328x(00)95077-0.Suche in Google Scholar

28. Kösterke, T., Pape, T., Hahn, F. E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 2112–2115.10.1021/ja110634hSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

29. Blumenberg, J., Wilm, L. F. B., Hahn, F. E. Organometallics 2020, 39, 1281–1287; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.organomet.0c00046.Suche in Google Scholar

30. Branzan, R. M. C., Kösters, J., Jahnke, M. C., Hahn, F. E. Z. Naturforsch 2016, 71b, 1077–1085; https://doi.org/10.1515/znb-2016-0137.Suche in Google Scholar

31. Jin, H., Tan, T. T. Y., Hahn, F. E. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 13811–13815; https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201507206.Suche in Google Scholar

32. Jin, H., Mück-Lichtenfeld, C., Hepp, A., Stephan, D. W., Hahn, F. E. Chem. Eur J. 2017, 23, 5943–5947; https://doi.org/10.1002/chem.201700065.Suche in Google Scholar

33. Termühlen, S., Blumenberg, J., Hepp, A., Daniliuc, C. G., Hahn, F. E. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 2599–2602; https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.202010988.Suche in Google Scholar

34. Jahnke, M. C., Hervé, A., Kampert, F., Hahn, F. E. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2021, 515, 120055; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ica.2020.120055.Suche in Google Scholar

35. Brackemeyer, D., Hervé, A., Schulte to Brinke, C., Jahnke, M. C., Hahn, F. E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 7841–7844; https://doi.org/10.1021/ja5030904.Suche in Google Scholar

36. Kampert, F., Brackemeyer, D., Tan, T. T. Y., Hahn, F. E. Organometallics 2018, 37, 4181–4185; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.organomet.8b00685.Suche in Google Scholar

37. Klein, J. P., Klaus, J. S., Kumar, A. M., Gong, B. U. S. Jpn. Outlook 2005, 6, 878–715 B1.Suche in Google Scholar

38. Dutschke, P. D., Bente, S., Daniliuc, C. G., Kinas, J., Hepp, A., Hahn, F. E. Dalton Trans. 2020, 49, 14388–14392; https://doi.org/10.1039/d0dt03369c.Suche in Google Scholar

39. Kösterke, T., Kösters, J., Würthwein, E.-U., Mück-Lichtenfeld, C., Schulte to Brinke, C., Lahoz, F., Hahn, F. E. Chem. Eur J. 2012, 18, 14594–14598; https://doi.org/10.1002/chem.201202973.Suche in Google Scholar

40. Sheldrick, G. M. Acta Crystallogr. 2015, A71, 3–8; https://doi.org/10.1107/s2053273314026370.Suche in Google Scholar

41. Sheldrick, G. M. Acta Crystallogr. 2015, C71, 3–8.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2021 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- In this issue

- Synthesis and evaluation of α-glucosidase inhibitory activity of sulfonylurea derivatives

- Discovery of novel obovatol-based phenazine analogs as potential antifungal agents: synthesis and biological evaluation in vitro

- Fluorine analogs of dicamba and tricamba herbicides; synthesis and their pesticidal activity

- Synthesis and crystal structure analyses of tri-substituted guanidine-based copper(II) complexes

- Synthesis, cytotoxicity and in silico study of some novel benzocoumarin-chalcone-bearing aryl ester derivatives and benzocoumarin-derived arylamide analogs

- The guanidinium t-diaqua-bis(oxalato)chromate(III) dihydrate complex: synthesis, crystal structure, EPR spectroscopy and magnetic properties

- Synthesis of the scandium chloride hydrates ScCl3·3H2O and Sc2Cl4(OH)2·12H2O and their characterisation by X-ray diffraction, 45Sc NMR spectroscopy and DFT calculations

- Oxidative addition of a 8-bromotheobromine derivative to d10 metals

- A 3D 2-fold interpenetrating Cu(II) coordination polymer based on 4,4′-oxybis(benzoic acid) and 1,3-bis(2-methyl-imidazol-1-yl) benzene exhibiting photocatalytic properties

- Crystal structure of the new silicide LaNi11.8–11.4Si1.2–1.6

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- In this issue

- Synthesis and evaluation of α-glucosidase inhibitory activity of sulfonylurea derivatives

- Discovery of novel obovatol-based phenazine analogs as potential antifungal agents: synthesis and biological evaluation in vitro

- Fluorine analogs of dicamba and tricamba herbicides; synthesis and their pesticidal activity

- Synthesis and crystal structure analyses of tri-substituted guanidine-based copper(II) complexes

- Synthesis, cytotoxicity and in silico study of some novel benzocoumarin-chalcone-bearing aryl ester derivatives and benzocoumarin-derived arylamide analogs

- The guanidinium t-diaqua-bis(oxalato)chromate(III) dihydrate complex: synthesis, crystal structure, EPR spectroscopy and magnetic properties

- Synthesis of the scandium chloride hydrates ScCl3·3H2O and Sc2Cl4(OH)2·12H2O and their characterisation by X-ray diffraction, 45Sc NMR spectroscopy and DFT calculations

- Oxidative addition of a 8-bromotheobromine derivative to d10 metals

- A 3D 2-fold interpenetrating Cu(II) coordination polymer based on 4,4′-oxybis(benzoic acid) and 1,3-bis(2-methyl-imidazol-1-yl) benzene exhibiting photocatalytic properties

- Crystal structure of the new silicide LaNi11.8–11.4Si1.2–1.6