Abstract

The structural and elastic properties of V-Si (V3Si, VSi2, V5Si3, and V6Si5) compounds are studied by using first-principles method. The calculated equilibrium lattice parameters and formation enthalpy are in good agreement with the available experimental data and other theoretical results. The calculated results indicate that the V-Si compounds are mechanically stable. Elastic properties including bulk modulus, shear modulus, Young’s modulus, and Poisson’s ratio are also obtained. The elastic anisotropies of V-Si compounds are investigated via the three-dimensional (3D) figures of directional dependences of reciprocals of Young’s modulus. Finally, based on the quasi-harmonic Debye model, the internal energy, Helmholtz free energy, entropy, heat capacity, thermal expansion coefficient, Grüneisen parameter, and Debye temperature of V-Si compounds have been calculated.

1 Introduction

Due to the potential chemical and physical properties, transition metal silicides draw much interest in high-temperature applications [1]. According to the V-Si binary phase diagram, there are four binary silicide compounds (A15-V3Si, C40-VSi2, D8m-V5Si3, and V6Si5 with an orthorhombic structure) [2]. The V-Si compounds have been studied for many years. For V5Si3, there are three phases with W5Si3-prototype, Mn5Si3-prototype, and Cr5B3-prototype, where the W5Si3-prototype phase is a stable structure [3]. We just study the W5Si3-prototype V5Si3. In order to obtain the structural and mechanical properties of the V-Si compounds, a number of works have been reported. Carcia and Barsch measured the pressure derivatives of the single-crystal elastic constants of V3Si at 77 and 298 K [4]. Zhang et al. investigated the thermodynamic stability of V6Si5 [5]. Zhang et al. also optimised thermodynamic modeling of the V-Si compounds by experiments [6]. The structural and electronic properties (electronic band structures and density of states) of V3Si, VSi2, V5Si3, and V6Si5 have been investigated by using density functional calculations [7].

However, other studies have also studied the elastic constants of V-Si compounds using ultrasonic measurements [8]. In theoretical studies, elastic constants and the directional dependences of Young’s modulus have not been discussed adequately but are important. In this work, we performed first-principles calculations for the elastic properties of V3Si, VSi2, V5Si3, and V6Si5 consisting of elastic constants, bulk modulus, Young’s modulus, shear modulus, Poisson’s ratio, and directional dependences of Young’s modulus. Based on the quasi-harmonic Debye model, Debye temperature, Grüneisen parameter, heat capacity, and thermal expansion coefficient of V3Si, VSi2, V5Si3, and V6Si5 compounds are also investigated.

2 Method

The first-principles calculations are performed by using the plane wave method, as implemented in the CASTEP code [9], which has been shown to obtain the reliable results for the structural properties of various solids [10]. For structural property calculations, the exchange correlation potential is described in the generalised gradient approximation (GGA) using the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) functional [11]. Vanderbilt-type ultrasoft pseudopotentials (USPPs) [12] are employed to describe the electron–ion interactions. Two parameters that affect the accuracy of calculations are the kinetic energy cutoff that determines the number of plane waves in the expansion and the number of special k points used for the Brillouin zone (BZ) integration. We performed convergence with respect to BZ sampling and the size of the basis set. Converged results are achieved with special k-points mesh 10×10×10 for V3Si, 8×8×8 for VSi2, 5×5×4 for V5Si3, and V6Si5, respectively. The size of the basis set is given by cutoff energy equal to 500 eV.

3 Results and Discussion

3.1 Structural Properties

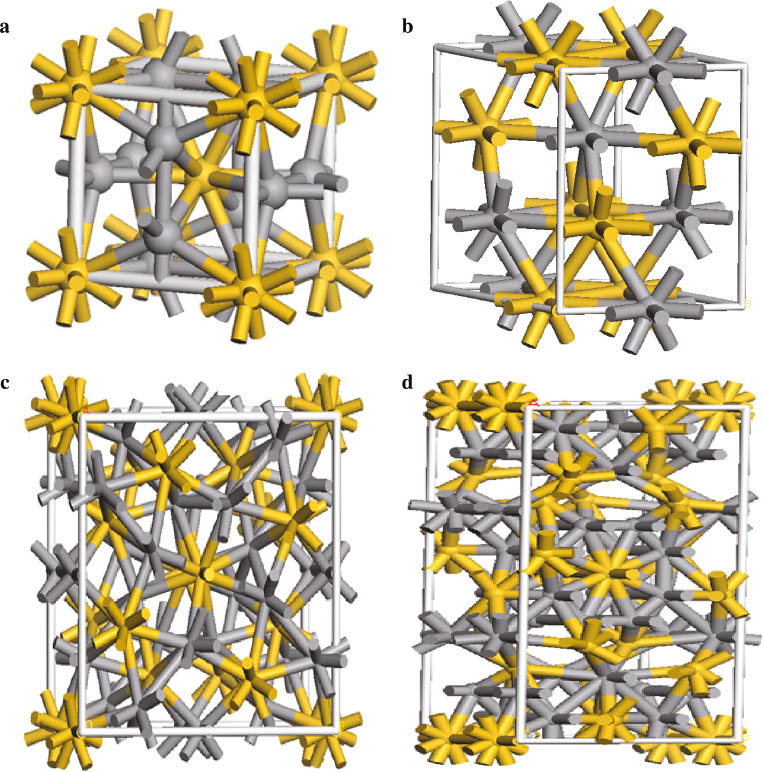

In this article, the initial crystal structures are based on the experimental crystallographic data of V-Si compounds, and the lattice parameters of these compounds are optimised by using first-principle calculations. The crystal structures of V-Si compounds are shown in Figure 1. The optimised lattice parameters are listed in Table 1, where the available experimental data and other theoretical results are included. For V3Si, the calculated lattice parameters by the GGA-PBE method are in good agreement with the previous results (4.7001 Å) and other theoretical results [13, 15, 16]. For VSi2, the calculated lattice parameters are found to be a=b=4.5597 Å, c=6.3602 Å, respectively, showing that they are in good agreement with the experimental values [17]. For V5Si3, the calculated lattice parameters are found to be a=b=9.3997 Å, c=4.7252 Å, respectively, are in good agreement with previous results [3, 7, 16]. For V6Si5, the calculated lattice parameters in this work are well consistent with the previous results [16, 18]. These agreements with the previous results provide a confirmation that this work is reliable.

The crystal structure of V-Si compounds (a) V3Si, (b) VSi2, (c) V5Si3, and (d) V6Si5 (The V atoms are shown as gray spheres and the Si atoms as yellow spheres.).

Calculated results with other theoretical and experimental lattice parameters (Å) and formation enthalpy (kJ/mol) of the V3Si, VSi2, V5Si3, and V6Si5.

| System | Space group | a | b | c | Ef |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V3Si | pm3n | 4.7021a | –44.78a | ||

| 4.735 [13] | –38.75 [14] | ||||

| 4.727 [15] | –46.4 [13] | ||||

| 4.7001 [16] | –44.6 [16] | ||||

| VSi2 | p6422 | 4.5597a | 4.5597a | 6.3602a | –54.26a |

| 4.57 [17] | 4.57 [17] | 6.37 [17] | –45.91 [5] | ||

| V5Si3 | I4/mcm | 9.3997a | 4.7252a | –59.55a | |

| 9.3930 [16] | 4.7292 [16] | –56.5 [16] | |||

| 9.46 [7] | 4.77 [7] | –53.73 [5] | |||

| 9.44 [7] | 4.76 [7] | –59.00±2 [13] | |||

| 9.3947 [3] | 4.7265 [3] | –56.4 [3] | |||

| V6Si5 | Ibam | 15.9126a | 7.4859a | 4.8296a | –54.27a |

| 15.9419 [16] | 7.4951 [16] | 4.8100 [16] | –53 [16] | ||

| 15.966 [18] | 7.501 [18] | 4.858 [18] | –50.7±2 [19–21] |

aThis work.

The formation enthalpy Ef per atom of the VxSiy compounds can be expressed as

where x and y are indices that give the amount of atoms of each atomic species within the unit cell of a structure VxSiy. Etot is the total energy of atom of the elements or compound. The calculated formation enthalpies of V3Si, VSi2, V5Si3, and V6Si5 are also listed in Table 1, together with available experimental data and other theoretical results. For V3Si, the formation enthalpy Ef is in good agreement with previous results [13, 14, 16]. The formation enthalpy of VSi2 is also predicted in this work and in good agreement with theoretical results [5]. Compared to the experimental data [13], the present calculated formation enthalpy of the V5Si3 is also in good agreement and is coherent with other theoretical results [3, 5, 16]. For V6Si5, the calculated formation enthalpy Ef (–54.27 kJ/mol) in this work is in good agreement with the value –53 kJ/mol obtained by the GGA-PBE method [16] and other previous measurement results [19–21]. The deviation is only 6.57%.

3.2 Elastic Constants

The number of independent elastic constants is different for various crystal structures. For a cubic crystal, it has three independent elastic constants (C11, C12, and C44). For a hexagonal crystal, it has five independent elastic constants (C11, C12, C13, C33, and C44). For a tetragonal chalcopyrite crystal, it has six independent elastic constants (C11, C12, C13, C33, C44, and C66). For an orthorhombic crystal, it has nine elastic constants (C11, C22, C33, C44, C55, C66, C12, C13, and C23). The mechanical stability criteria are given by [22–25].

As shown in Table 2, all of the elastic constants for V3Si, VSi2, V5Si3, and V6Si5 compounds satisfy the respective mechanical stability criteria. It indicates that all above structures are mechanically stable. The elastic constants for V3Si are in agreement with the experimental data (at T=77 K) [4]. It is worth pointing out that our theoretical calculations of the elastic constants for VSi2 with space group P6422 are in agreement with the experimental data [17]. The Cij values calculated by the GGA-PBE method of V5Si3 are also provided and compared. The calculated Cij values in this work are well consistent with the previous results [3]. Unfortunately, there are no other theoretical and experimental results for comparison with our elastic results for V6Si5.

Calculated results with other theoretical and experimental elastic constants Cij (GPa) of the compounds in V3Si, VSi2, V5Si3, and V6Si5.

| System | C11 | C12 | C13 | C22 | C23 | C33 | C44 | C55 | C66 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V3Si | This work | 241.78 | 169.56 | 78.60 | ||||||

| [4] | 233.6 | 151 | 77.1 | |||||||

| VSi2 | This work | 375.46 | 62.70 | 76.39 | 426.99 | 144.94 | ||||

| [17] | 357.8 | 50.6 | 68.1 | 422.3 | 135.7 | |||||

| V5Si3 | This work | 397.23 | 104.46 | 99.91 | 341.07 | 104.09 | 129.06 | |||

| [3] | 401.7 | 106.7 | 99.6 | 351.1 | 103.1 | 127.8 | ||||

| V6Si5 | This work | 392.70 | 123.69 | 80.59 | 331.60 | 91.74 | 343.01 | 136.12 | 98.89 | 114.54 |

It is known that the mechanical properties are determined by the elastic modulus. The polycrystalline elastic properties, including bulk modulus B, shear modulus G, Young modulus E, and Poisson’s ratio σ, can be obtained by Voigt–Reuss–Hill (VRH) approximation. The B, G, and E are listed in Table 3. As can be seen from Table 3, the bulk modulus B of for V-Si compounds follows the order V3Si>V5Si3>V6Si5>VSi2. V3Si has the largest bulk modulus (193.64 GPa). The Young’s modulus of for the V3Si, VSi2, V5Si3, and V6Si5 compounds follows the order VSi2>V5Si3>V6Si5>V3Si.

Calculated results with other theoretical and experimental bulk modulus B (GPa), shear modulus G (GPa), Young modulus E (GPa), Poisson’s ratio σ, the ratio of the shear modulus G to the bulk modulus B, the compressional wave Vp (m/s), the shear velocities VS (m/s), and average wave velocity Vm (m/s) of the compounds in V3Si, VSi2, V5Si3, and V6Si5.

| System | B | G | E | σ | B/G | Vp | VS | Vm | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V3Si | This work | 193.64 | 57.52 | 157.01 | 0.364 | 3.37 | 6939.3 | 3154.8 | 3554.1 |

| [8] | 213 | 7116 | 3819 | ||||||

| VSi2 | This work | 178.29 | 153.15 | 357.18 | 0.166 | 1.16 | 9060.4 | 5733.2 | 6307 |

| Exp. [17] | 167.2 | 147.9 | 342.6 | 0.158 | |||||

| [8] | 8757 | 5535 | |||||||

| V5Si3 | This work | 193.26 | 121.69 | 301.74 | 0.239 | 1.59 | 8213.4 | 4805.3 | 5328.5 |

| [3] | 195.8 | 122.1 | 303.1 | 0.24 | 1.60 | 8150 | 4755 | 5274 | |

| [8] | 7818 | 4380 | |||||||

| V6Si5 | This work | 183.71 | 120.16 | 295.95 | 0.232 | 1.53 | 9910.7 | 5858 | 6489.7 |

According to Pugh’s criterion [26], the ductility or brittleness of a solid material is judged by B/G ratio. The critical value which separates ductile and brittle material is B/G=1.75. If B/G>1.75, behaves in a ductile manner. Otherwise, behaves in a brittle. Moreover, the Poisson’s ratio σ is consistent with B/G, which refers to a ductile compound has a large σ>0.26 [27]. The values of B/G are larger than 1.75 and values of σ are larger than 0.26 for V3Si in Table 3, which testify that they are ductile. The values of B/G and σ for VSi2, V5Si3, and V6Si5 are less than 1.75 and 0.26, respectively. It shows that they are all brittle.

The values of the compressional velocity wave Vp and the shear wave velocity VS can be obtained using the Navier’s equation [28], where ρ is density of the compound.

The average wave velocity Vm can be calculated by

The calculated sound velocity of Vp, VS, and Vm for the V3Si, VSi2, V5Si3, and V6Si5 compounds are listed in Table 3. In comparison, the calculated values of Vp and VS for V3Si at zero pressure are a little lower than reported by Fleischer et al. [8]. For VSi2, the calculated values of Vp and VS are in good agreement with those reported by Fleischer et al. [8]. For V5Si3, the calculated Vp and VS in this work are in agreement with the values by the VASP-GGA method [3] and other previous results [8]. Without experimental data and theoretical results of the V6Si5, we cannot make any comparisons. We expect that our theoretical results provide the valuable reference for the further research.

As a method to study the elastic anisotropic behavior of a solid material, the 3D surface constructions of the directional dependences of reciprocals of Young’s modulus E are very useful. The expressions of the reciprocals of Young’s modulus for the V3Si, VSi2, V5Si3, and V6Si5 compounds are different for each other due to their various crystal structures [22].

In Figure 2, we show the mechanical stable structures of V3Si, VSi2, V5Si3, and V6Si5 compounds. The surface in each graph represents the magnitude of Young’s modulus E along different orientations. From this figure, we can clearly see that the Young’s modulus shows some anisotropy at different orientations. It also should be noted that the Young’s modulus of V3Si shows slight anisotropy and the Young’s modulus of VSi2, V5Si3, and V6Si5 shows some anisotropy for different orientations. As for the hexagonal VSi2, the 3D directional dependences of the Young’s modulus along z axis are more compressible than along x- and y-axes. The 3D figure of the Young’s modulus for the tetragonal V5Si3 is characterised by more anisotropic along the z-axis than that along the x- and y-axes. As for the orthorhombic V6Si5, the 3D surface of Young’s modulus along x-, y-, and z-axes is shown highly anisotropic.

![Figure 2: The directional dependence of the Young’s modulus for the V3Si, VSi2, V5Si3, and V6Si5 compounds [(a) V3Si, (b) VSi2, (c) V5Si3, and (d) V6Si5]. The magnitude of Young’s modulus at different directions is represented by the contour. The units are in GPa.](/document/doi/10.1515/zna-2015-0367/asset/graphic/j_zna-2015-0367_fig_002.jpg)

The directional dependence of the Young’s modulus for the V3Si, VSi2, V5Si3, and V6Si5 compounds [(a) V3Si, (b) VSi2, (c) V5Si3, and (d) V6Si5]. The magnitude of Young’s modulus at different directions is represented by the contour. The units are in GPa.

3.3 Thermal Properties of V3Si, VSi2, V5Si3, and V6Si5 under High Temperature and High Pressure

In order to investigate the thermal properties of V3Si, VSi2, V5Si3, and V6Si5 compounds under high pressure (0–25 GPa) and melting points temperature [6], we have used the quasi-harmonic Debye model as implemented in the Gibbs code [29]. First, we obtain a set of total energy results versus unit-cell volumes around the equilibrium geometry. Then, the above-mentioned results are fitted to the equation of state in order to obtain different parameters as a function of pressure and temperature from standard thermal relations. By the above-mentioned method, we can get the internal energy U, the heat capacity of constant volume CV, the heat capacity at constant pressure CP, the entropy S, the thermal expansion coefficient α, Debye temperature Θ, and Grüneisen parameter γ.

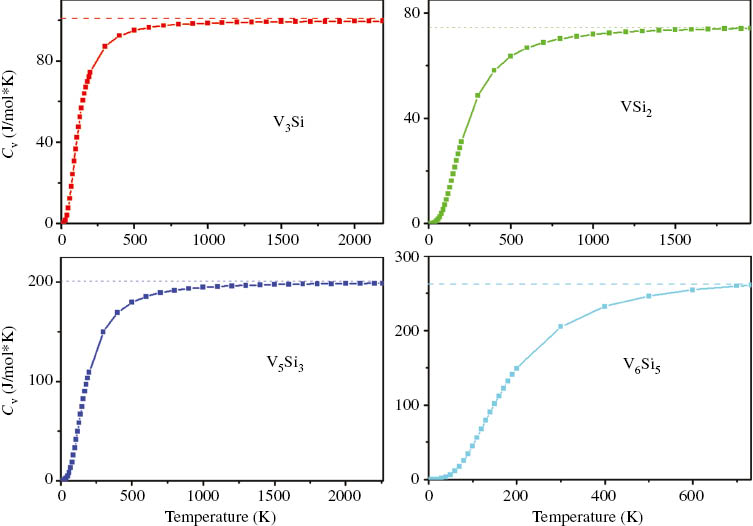

The thermal properties of the V3Si, VSi2, V5Si3, and V6Si5 compounds are calculated at the different temperatures ranging from 0 to about melting points. The pressure effect is investigated in the range 0–25 GPa. Heat capacity belongs to one of the most important thermal properties of the materials. Figure 3 shows the calculated heat capacity at constant volume as functions of the temperature under zero GPa. It can be seen from Figure 3 that the heat capacity CV increases exponentially with the temperature at T<400 K. At higher temperature, CV follows the Debye model and approaches the Dulong–Petit limit indicating the thermal energy at high temperature excites all phonon modes.

The heat capacity of constant volume CV (J/mol K) for V3Si, VSi2, V5Si3, and V6Si5 in V-Si compounds at 0 GPa.

As an important physical quantity, the Debye temperature could distinguish the physical properties between high- and low-temperature regions. The variation of the Debye temperature Θ (K) as a function of pressure and temperature is displayed in Figure 4. With the applied pressure increasing, the Debye temperatures are almost linearly increasing. The temperature and pressure dependence of Θ (K) reveals that the thermal vibration frequency of atoms in V-Si (V3Si, VSi2, V5Si3, and V6Si5) compounds changes with temperature and pressure.

Debye temperature versus pressure at various temperatures for V3Si, VSi2, V5Si3, and V6Si5.

Figure 5 shows the volume thermal expansion coefficient a of V3Si, VSi2, V5Si3, and V6Si5 across different pressures, from which it can be seen that the volume thermal expansion coefficient α increases quickly at a given temperature particularly at zero pressure below the temperature of 300 K. After a sharp increase, the volume thermal expansion coefficient of the V3Si, VSi2, V5Si3, and V6Si5 is nearly insensitive to the temperature above 300 K due to the electronic contributions. Thermal expansion coefficient α strongly decreases with pressure at a constant temperature.

Thermal expansion coefficients versus temperature at various pressures for V3Si, VSi2, V5Si3, and V6Si5.

Finally, we have also calculated the internal energy U, entropy S, thermal expansion coefficient α, heat capacity CV and CP, Helmholtz free energy A, Grüneisen parameter γ, and Debye temperature Θ for the V3Si, VSi2, V5Si3, and V6Si5 in V-Si at 300 K under different pressures. The theoretical results are presented in Table 4. However, there has been no experimental and theoretical data available for the thermal properties of V3Si, VSi2, V5Si3, and V6Si5 compounds so far. Therefore, our calculated results can provide support for future works on V3Si, VSi2, V5Si3, and V6Si5 compounds.

The calculated internal energy U (kJ/mol), heat capacity of constant volume CV (J/mol*K), heat capacity of constant pressure CP (J/mol*K), Helmholtz free energy A (kJ/mol), entropy S (J/mol*K), Debye temperature Θ (K), Grüneisen parameter γ, and thermal expansion coefficient α (10–5/K) for V3Si, VSi2, V5Si3, and V6Si5 at 300 K under different pressures.

| P/GPa | U | CV | Cp | A | S | Θ | γ | α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V3Si | ||||||||

| 0.00 | 33.96 | 87.19 | 87.79 | 7.35 | 88.69 | 499.87 | 1.768 | 1.31 |

| 5.00 | 34.31 | 86.15 | 86.66 | 8.85 | 84.87 | 522.37 | 1.705 | 1.16 |

| 10.00 | 34.65 | 85.17 | 85.61 | 10.19 | 81.56 | 543.00 | 1.653 | 1.04 |

| 15.00 | 34.98 | 84.24 | 84.62 | 11.40 | 78.62 | 562.16 | 1.609 | 0.95 |

| 20.00 | 35.30 | 83.35 | 83.69 | 12.40 | 75.98 | 580.12 | 1.571 | 0.87 |

| 25.00 | 35.60 | 82.50 | 82.80 | 13.52 | 73.59 | 597.14 | 1.537 | 0.80 |

| VSi2 | ||||||||

| 0.00 | 32.07 | 48.60 | 49.01 | 22.82 | 30.83 | 923.96 | 2.593 | 1.08 |

| 5.00 | 33.38 | 45.81 | 46.10 | 25.14 | 27.48 | 991.74 | 2.463 | 0.86 |

| 10.00 | 34.54 | 43.49 | 43.71 | 27.05 | 24.97 | 1049.19 | 2.369 | 0.72 |

| 15.00 | 35.69 | 41.31 | 41.48 | 28.84 | 22.80 | 1104.18 | 2.289 | 0.61 |

| 20.00 | 36.82 | 39.25 | 39.39 | 30.55 | 20.91 | 1157.32 | 2.221 | 0.52 |

| 25.00 | 37.84 | 37.51 | 37.62 | 32.02 | 19.40 | 1203.72 | 2.166 | 0.46 |

| V5Si3 | ||||||||

| 0.00 | 76.91 | 149.88 | 150.97 | 42.94 | 113.23 | 740.44 | 1.973 | 1.24 |

| 5.00 | 78.52 | 145.85 | 145.85 | 46.70 | 106.07 | 777.18 | 1.899 | 1.07 |

| 10.00 | 80.06 | 142.12 | 142.12 | 50.08 | 99.93 | 811.02 | 1.837 | 0.94 |

| 15.00 | 81.51 | 138.69 | 139.25 | 53.11 | 94.67 | 841.96 | 1.786 | 0.84 |

| 20.00 | 82.90 | 135.46 | 136.00 | 55.90 | 90.01 | 871.07 | 1.742 | 0.76 |

| 25.00 | 84.25 | 132.42 | 132.98 | 58.49 | 85.86 | 899.48 | 1.704 | 0.69 |

| V6Si5 | ||||||||

| 0.00 | 106.01 | 205.42 | 206.93 | 59.67 | 154.47 | 744.86 | 1.952 | 1.25 |

| 5.00 | 108.31 | 199.72 | 200.94 | 64.97 | 144.45 | 782.62 | 1.877 | 1.08 |

| 10.00 | 110.48 | 194.45 | 195.46 | 69.71 | 135.90 | 817.31 | 1.815 | 0.95 |

| 15.00 | 112.53 | 189.62 | 190.47 | 73.95 | 128.60 | 848.99 | 1.764 | 0.85 |

| 20.00 | 114.51 | 185.08 | 185.81 | 77.87 | 122.13 | 878.78 | 1.719 | 0.76 |

| 25.00 | 116.44 | 180.75 | 181.39 | 81.54 | 116.32 | 907.18 | 1.680 | 0.69 |

4 Conclusions

We have investigated the structural, elastic properties, elastic anisotropy, and thermodynamic properties of V3Si, VSi2, V5Si3, and V6Si5 compounds using first-principles calculations. The calculated elastic constants of compounds indicate that the V3Si, VSi2, V5Si3, and V6Si5 compounds are mechanically stable. Bulk modulus, shear modulus, Young’s modulus, and Poisson’s ratio have also been calculated and discussed. Moreover, we found that the pressure and temperature have important effects on the internal energy, heat capacity, Helmholtz free energy, entropy, Debye temperature, Grüneisen parameter, and thermal expansion coefficient.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant nos. 51402251 and 51502259). This work was sponsored by the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province of China (BK20130428). This work was supported by the joint research fund between Collaborative Innovation Center for Ecological Building Materials and Environmental Protection Equipments and Key Laboratory for Advanced Technology in Environmental Protection of Jiangsu Province (GX2015305), and Natural Science Foundation of the Higher Education Institutions of Jiangsu Province (Grant no. 14KJD430003). This work was supported by the science and technology project from Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China (2015-K4-007). This work was supported by Top-notch Academic Programs Project of JiangSu Higher Education Institutions, TAPP (Grant no. PPZY2015A025).

References

[1] B. P. Bewlay, M. R. Jackson, J. C. Zhao, P. R. Subramanian, M. G. Mendiratta, et al., MRS Bull. 28, 646 (2003).10.1557/mrs2003.192Suche in Google Scholar

[2] T. B. Massalski, J. L. Murray, L. H. Bennett, and H. Baker (Eds.), Binary Alloy Phase Diagrams, ASM Metals Park, OH 1990.Suche in Google Scholar

[3] X. M. Tao, H. M. Chen, X. F. Tong, Y. F. Ouyang, P. Jund, et al., Comput. Mater. Sci. 53, 169 (2012).10.1016/j.commatsci.2011.09.030Suche in Google Scholar

[4] P. F. Carcia and G. H. Barsch, Phys. Stat. Sol. (b) 59, 595 (1973).10.1002/pssb.2220590227Suche in Google Scholar

[5] C. Zhang, J. Wang, Y. Du, and W. Q Zhang, J. Mater. Sci. 42, 7046 (2007).10.1007/s10853-007-1865-6Suche in Google Scholar

[6] C. Zhang, Y. Du, W. Xiong, H. H. Xu, P. Nash, et al., Calphad 32, 320 (2008).10.1016/j.calphad.2007.12.005Suche in Google Scholar

[7] M. B. Thieme and S. Gemming, Acta. Metall. 57, 50 (2009).10.1016/j.actamat.2008.08.034Suche in Google Scholar

[8] R. L. Fleischer, R. S. Gilmore, and R. J. Zabala. Acta. Metall. 37, 2801 (1989).10.1016/0001-6160(89)90314-3Suche in Google Scholar

[9] V. Milman, B. Winkler, J. A. White, C. J. Packard, M. C. Payne, et al., Int. J. Quantum Chem. 77, 895 (2000).10.1002/(SICI)1097-461X(2000)77:5<895::AID-QUA10>3.0.CO;2-CSuche in Google Scholar

[10] H. J. Hou, F. J. Kong, J. W. Yang, L. H. Xie, and S. X. Yang, Phys. Scr. 89, 065703 (2014).10.1088/0031-8949/89/6/065703Suche in Google Scholar

[11] J. P. Perdew, K. Burke, and M. Ernzerhof, Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996).10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.3865Suche in Google Scholar

[12] D. Vanderbilt, Phys. Rev. B 41, 7892 (1990).10.1103/PhysRevB.41.7892Suche in Google Scholar

[13] S. V. Meschel and O. J. Kleppa, J. Alloys Compd. 267, 128 (1998).10.1016/S0925-8388(97)00528-8Suche in Google Scholar

[14] E. K. Storms and C. E. Myers, High Temp. Sci. 20, 87 (1985).Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Y. F. Lomnytska, Powder Metall. Met. Ceram. 46, 461 (2007).10.1007/s11106-007-0072-ySuche in Google Scholar

[16] C. Colinet and J. C. Tedenac, Comput. Mater. Sci. 85, 94 (2014).10.1016/j.commatsci.2013.12.044Suche in Google Scholar

[17] F. Chu, M. Lei, S. A. Maloy, J. J. Petrovic, and T.E. Mitchell, Acta Mater. 44, 3035 (1996).10.1016/1359-6454(95)00442-4Suche in Google Scholar

[18] P. Spinat, R. Fruchart, and P. Herpin, Bull. Soc. Fr. Mineral. Cristallogr. 93, 23 (1970).10.3406/bulmi.1970.6423Suche in Google Scholar

[19] V. N. Eremenko, G. M. Lukashenko, and V. R. Sidorko, Rev. Intl. Hautes Temp. Refract. 12, 237 (1975).Suche in Google Scholar

[20] V. N. Eremenko, G. M. Lukashenko, V. R. Sidorko, and O. G. Kulik, Dopov. Akad. Nauk Ukr. RSR Ser. A 38, 365 (1976).Suche in Google Scholar

[21] V. N. Eremenko, G. M. Lukashenko, and V. R. Sidorko, Dopov. Akad. Nauk Ukr. RSR Ser. B 36, 712 (1974).Suche in Google Scholar

[22] J. F. Nye, Physical Properties of Crystals, Oxford University Press, Oxford 1985.Suche in Google Scholar

[23] Q. K. Hu, Q. H. Wu, Y. M. Ma, L. J. Zhang, Z. Y. Liu, et al., Phys. Rev. B 73, 214116 (2006).10.1103/PhysRevB.73.214116Suche in Google Scholar

[24] M. Born and K. Huang, Dynamical Theory of Crystal Lattices, Clarendon Press, Oxford 1954.Suche in Google Scholar

[25] O. Beckstein, J. E. Klepeis, G. L. W. Hart, and O. Pankratov, Phys. Rev. B 63, 134112 (2001).10.1103/PhysRevB.63.134112Suche in Google Scholar

[26] S. F. Pugh, Philos. Mag. 45, 823 (1954).10.1080/14786440808520496Suche in Google Scholar

[27] J. J. Lewandowski, W. H. Wang, and A. L. Greer, Philos. Mag. Lett. 85, 77 (2005).10.1080/09500830500080474Suche in Google Scholar

[28] K. B. Panda and K.S. Ravi Chandran, Comput. Mater. Sci. 35, 134 (2006).10.1016/j.commatsci.2005.03.012Suche in Google Scholar

[29] M. A. Blanco, E. Francisco, and V. Luaa, Comput. Phys. Commun. 158, 57 (2004).10.1016/j.comphy.2003.12.001Suche in Google Scholar

©2016 by De Gruyter

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Decay Mode Solutions for the Supersymmetric Cylindrical KdV Equation

- Cooling of Moving Wavy Surface through MHD Nanofluid

- Parallel Plate Flow of a Third-Grade Fluid and a Newtonian Fluid With Variable Viscosity

- Flow of a Micropolar Fluid Through a Channel with Small Boundary Perturbation

- Exact Solutions for Stokes’ Flow of a Non-Newtonian Nanofluid Model: A Lie Similarity Approach

- A New Reduction of the Self-Dual Yang–Mills Equations and its Applications

- Quasi-periodic Solutions to the K(−2, −2) Hierarchy

- Superposition of Solitons with Arbitrary Parameters for Higher-order Equations

- Elastic and Thermal Properties of Silicon Compounds from First-Principles Calculations

- Exact Solutions for N-Coupled Nonlinear Schrödinger Equations With Variable Coefficients

- Rapid Communication

- Electrical Conductivity of Molten CdCl2 at Temperatures as High as 1474 K

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Decay Mode Solutions for the Supersymmetric Cylindrical KdV Equation

- Cooling of Moving Wavy Surface through MHD Nanofluid

- Parallel Plate Flow of a Third-Grade Fluid and a Newtonian Fluid With Variable Viscosity

- Flow of a Micropolar Fluid Through a Channel with Small Boundary Perturbation

- Exact Solutions for Stokes’ Flow of a Non-Newtonian Nanofluid Model: A Lie Similarity Approach

- A New Reduction of the Self-Dual Yang–Mills Equations and its Applications

- Quasi-periodic Solutions to the K(−2, −2) Hierarchy

- Superposition of Solitons with Arbitrary Parameters for Higher-order Equations

- Elastic and Thermal Properties of Silicon Compounds from First-Principles Calculations

- Exact Solutions for N-Coupled Nonlinear Schrödinger Equations With Variable Coefficients

- Rapid Communication

- Electrical Conductivity of Molten CdCl2 at Temperatures as High as 1474 K