Abstract

Research on legal mobilisation in cases of prison violence is rare as it is positioned at the intersection of two separate strands of investigation: Whereas studies on legal mobilisation in prison hardly differentiate between distinctive types of problems or conflicts and thus neglect the particularities victims of violence are confronted with, research on violence in prison focuses on prevalence, prevention, procedural justice or the prison climate without integrating insights from the literature of legal mobilisation. In reconsidering the findings of an empirical study on violence in Austrian prisons, the authors argue that responses to violence in prison follow different rules to those used in complaint procedures, making official reporting more unlikely. To fully understand the barriers to legal claims procedures and the impact of extra-legal conflict resolution in the case of violent victimisation, a broad understanding of legal mobilisation that considers the complex and vivid dynamics of conflict resolution is helpful. Analysing the empirical data from this perspective allows not only to better understand the phenomenon of prison violence and the victims’ reluctance to use official reporting mechanisms, but also points to ways of dealing with violence to not feed the spiral of violence in prison.

Zusammenfassung

Forschung zur Rechtsmobilisierung in Fällen von Gewalt in Haft ist rar, da diese an der Schnittstelle zweier getrennter Untersuchungsfelder angesiedelt ist: Klassische Forschung zu Gewalt im Strafvollzug fokussiert, einerseits, auf Prävalenz, Prävention, Verfahrensgerechtigkeit oder das Haftklima ohne Erkenntnisse aus dem Bereich der Rechtsmobilisierungsforschung zu berücksichtigen. Andererseits unterscheiden Studien zur Rechtsmobilisierung im Strafvollzug kaum zwischen unterschiedlichen Problem- bzw. Konflikttypen und vernachlässigen damit die Besonderheiten von Gewalt in Gefängnissen. Die Ergebnisse einer empirischen Studie zu Gewalt in österreichischen Gefängnissen legen nahe, dass die Reaktion auf Gewalt dort anderen Regeln folgt als bei Beschwerden aus anderen Gründen: Gewalt offiziell zu melden ist, u.a. infolge des Stellenwerts und der Dynamiken von Gewalt in Haft, schwieriger und unwahrscheinlicher. Um besser zu verstehen, warum Opfer von Gewalt in Haft so selten offiziell Meldung erstatten und welche Konsequenzen außerrechtliche Konfliktlösungen haben, ist es hilfreich, Rechtsmobilisierung in seiner ganzen Breite zu fassen, d.h. die Komplexität und Dynamik der Konfliktbearbeitung umfassend zu berücksichtigen. Die Analyse der empirischen Daten aus dieser Perspektive ermöglicht nicht nur ein besseres Verständnis des Phänomens von Gewalt in Haft und der Zurückhaltung der Opfer bei der Inanspruchnahme offizieller Meldemechanismen, sondern zeigt auch Wege für einen Umgang mit Gewalt auf, der die Gewaltspirale nicht weiter nährt.

Based on an empirical study on violence in Austrian prisons (Hofinger & Fritsche 2021) the article focuses on prisoners’ responses to violent incidents and discusses them from a perspective of legal mobilisation.[1] Research on legal mobilisation in prison is rare, mainly focusing on when, why and by whom complaint procedures are used in US prisons (e.g., Calavita & Jenness 2013, 2014), and only in exceptional cases in European detention facilities, i.e., in Ireland (van der Valk et al. 2022) or Romania (Dâmboeanu et al. 2021). The complaints covered in these studies refer to a wide range of problems, for example, living conditions, medical care, missing or damaged property as well as lack of staff respect, rehabilitative programmes or jobs (Calavita & Jenness 2014: 56–62). Some also concern general notions of human rights violations, discrimination or situations of perceived procedural injustice (Dâmboeanu et al. 2021: 128–129). Violence remains a rather blurred cross-sectional category or does not come into focus at all. Even though these studies give relevant insights on the restricting and enabling factors of legal mobilisation in prison, as outlined below, differentiation by type of problems or conflicts that lead to putting “law in action” (Pound 1910) is lacking. Conversely, findings on how inmates respond to experiences of violent victimisation only integrate the theoretical findings of the legal mobilisation literature in exceptional cases; analyses of responses to such victimisation are often no more than a by-product of much broader studies on (unreported) violence, focusing on prevalence, individual coping strategies, prevention mechanisms, the overlap of offending and victimisation, or procedural justice (e.g. Rocheleau 2015; Bierie 2013; Steiner & Wooldredge 2020; van Ginneken & Wooldredge 2024; Caravaca-Sánchez et al. 2023; Silberman 2001; Day et al. 2022; Toman 2019; for the German speaking context: Baier & Bergmann 2013; Boxberg et al. 2016; Neubacher et al. 2018; Hofinger & Fritsche 2021). We thus contend that legal mobilisation in the context of violence in prison requires separate consideration. The individual handling of violent victimisation in prison, the relative normality of violence in everyday prison life as a widely accepted means of conflict resolution among prisoners, subcultures framed by notions of “hypermasculinity” and disdain for the role of the victim (Bereswill 2006: 244 referring to Toch 1998, Neuber 2014), as well as the prisoner code of non-cooperation with staff, suggest that an analysis of individual responses to violence from the theoretical perspective of legal mobilisation provides new insights into reducing violence and improving access to justice in prisons (Hofinger & Fritsche 2021: 280–297).

In our analysis we point to aspects that might be fruitful to consider in future research on the handling of violence in prison and encourage more differentiated discussions on legal mobilisation for particular types of problems and conflicts in prison settings. In addition, to address the current lack of geographic diversity (van der Valk et al. 2022: 263), we contribute a European perspective from a German-speaking context to the study of legal mobilisation in prison.

After a short outline of the design of the study on prison violence in Austria, we first approach legal mobilisation in general and analyse prison violence as a particular type of problem. Secondly, we use this framework to interpret empirical data regarding inmates’ reactions to violence and the use of institutional procedures. Thirdly, in summarising our empirical findings, we discuss particularities of legal mobilisation in the case of violence in prison. We point to aspects that might be useful to allow either for an increased effectiveness of existing mechanisms, or for more constructive ways of dealing with violence aside from official procedures, so that non-mobilisation does not feed the spiral of violence in imprisonment.

The study “Violence in Austrian prisons”

From 2018 to 2020 the first empirical study on violence in Austrian prisons was carried out (Hofinger & Fritsche 2021). Based on an approximated representative sample,[2] standardised face-to-face interviews were conducted with 386 inmates in 10 Austrian prisons (for details on methodology, cf. Hofinger & Fritsche 2021: 33–36; 103–106, 2020). Besides investigating the prevalence of physical, psychological and sexual violence (among inmates but also violence by staff)[3] as well as perceptions of the social climate as material, social, emotional and moral conditions (Auty & Liebling 2020: 359; Ross et al. 2008: 447) in Austrian prisons, data on how prisoners handled instances of violent victimisation were collected. For selected cases,[4] more detailed data on the consequences as well as on the actors that had been informed about the incident and the use of complaint procedures were gathered. Besides institutional reactions to these incidents, reasons for not filing a complaint were asked for, in case the violence was not officially reported. In line with current conceptual discussions highlighting the relevance of extra- and quasi-legal processes as well as the role of intermediaries for conflict transformation, the legal notion of mobilisation was understood very broadly, i.e., including reporting to officers, the prison management, the ombudsman’s office, the probation service, or one’s own lawyer. Also, questions on the reporting of incidents to social, medical, psychological or religious services were included in the questionnaire.

In addition to the questionnaire, ten problem-centred qualitative interviews (Witzel 2000) with prisoners who had recently experienced violence complemented the quantitative data, focusing on the reconstruction of violent incidents and their handling.[5] Six guided interviews with experts[6] contained a special section on reporting procedures in the case of violence and on the consequences of complaints.[7] Additionally, we received data on complaints and their processing from the Ministry of Justice.

Given the specific ethical challenges in prison settings and in research on violence, both quantitative as well as qualitative interviews were conducted in one-to-one settings in safe spaces by interviewers who were not only trained in methodology but also experienced in communicating with vulnerable groups. Face-to-face settings without strict time constraints provided room for building trust, thoroughly clarifying aspects of anonymity and informed consent,[8] and allowing for the dynamic development of conversations in line with the respondents’ needs. Given the taboo surrounding victimisation and experienced violence in detention, addressing the interviewees as “experts” on prison culture while simultaneously offering them spaces “to be heard” within a generally isolating environment helped mitigate the risk of re-traumatization during the interviews. Additionally, a leaflet listing victim support facilities was provided (Hofinger & Fritsche 2020: 18–24).

The research used a theoretically derived definition of violence, i.e, interviewees were asked how often they had experienced a particular situation in prison, such as aggressive shouting, humiliation, slapping, threats, beating, forced sexual acts etc. (Kapella et al. 2011; Straus et al. 1996; Ireland & Ireland 2008). In doing so, even incidents that the individual subjectively might not have considered as violence were recorded. As in other studies on violence in prison, this research did not initially focus on individual responses to violence. However, data analyses and retrospective reflections pointed to the relevance of reconsidering the findings in the light of the concept of legal mobilisation, searching for additional answers to explain inhibitions to official reporting and the relatively great numbers of unreported violence in prison as a highly regulated structure.

Limitations of the study mainly stem from the fact that the overall research project was not originally designed within a legal mobilisation framework, but focused on violence and prison climate. Complaint procedures were just one aspect among others. Thus, on the one hand, some indicators that could have been useful in further explaining (non-)mobilisation processes were either not gathered systematically or not in sufficient detail (e.g. further effects of [non-]mobilisation, detailed role of intermediaries, etc.). On the other hand, theoretical sampling for qualitative interviews was based more on criteria related to violence than to mobilisation.

Setting the frame: Legal mobilisation as a means of conflict resolution

Legal mobilisation can be understood as one form of conflict transformation, i.e. a particular way to respond to problems. In their seminal article, Felstiner et al. (1980–81) illustrate convincingly that, before a situation can be dealt with by an official (legal) institution, it has to go through several transformation processes in order to be perceived as a potentially legal, i.e., justiciable problem. The often-quoted triad, “naming, blaming, claiming” (Felstiner et al. 1980–81) points to a process, where an experience is perceived as injurious (naming), a guilty party is identified and the idea that something can be done about the grievance emerges (blaming), and where finally help or compensation is requested (claiming).

Conflict transformation passes several stages and “key transition decisions” (Trubek et al. 1983: 38) shaped by different “agents of transformation” (Felstiner et al. 1980–81: 639–649), structural conditions, as well as the actors’ position and consciousness. How a conflict is framed, what action is taken, depends on available economic, social and cultural resources, social inequality structures, such as race, class, gender, religion, disability etc., knowledge of law and rights, socialisation, “legal opportunity structures” (Vanhala 2012), or personality traits (Albiston et al. 2014; Morrill et al. 2015: 591; Genn et al. 1999; Blankenburg 1995; Gramatikov et al. 2010: 29ff.; Sandefur 2008; Engel & Munger 2003). Discourses of law and rights, reactions of the “audience” (Felstiner et al. 1980–81: 642) and the role of “mediating agents” (Albiston et al. 2014: 115), such as lawyers, NGOs, therapists etc. have a particular impact on conflict transformation. Studies on “Paths to Justice” (Genn et al. 1999; Pleasence et al. 2013) stress the relevance of the type of problem for strategies of conflict transformation. Not only the subjectively perceived severity of a problem, but also the quality of the relationship between the concerned parties are discussed as relevant factors; research findings suggest, for example, that conflicts in anonymous and short-term relationships are more often solved by legal means than conflicts in intimate and long-lasting relationships (Blankenburg 1995: 43; Miller & Sarat 1980: 544; Pleasence et al. 2013: 35). Decisions to use legal institutions are also influenced by previous experiences with the law – particularly for victims of violence (Merry 2003). These experiences shape images of the law and thus co-constitute legal (rights) consciousness, but also one’s sense of entitlement. Legal (rights) consciousness, i.e., “the ways in which people experience, understand, and act in relation to law” (Chua and Engel 2019: 336), or, more broadly, an individual’s “diffuse relation to law” (Baer 2021: 220 – own translation), is situated at the edges of legal mobilisation: By some it is perceived as an influencing factor, by others rather as a sub-aspect of legal mobilisation (Fuchs 2021: 36; Lehoucq & Taylor 2020: 178).

These different interpretations point to challenges in the definition of legal mobilisation and show that a clear and commonly recognised definition of the term is lacking: In their analysis of literature on legal mobilisation, Lehoucq and Taylor note a “conceptual slippage” (Lehoucq & Taylor 2020: 168) in the usage of the term, as different activities, various actors, and forms of claims are subsumed under the term legal mobilisation, and boundaries to other concepts, such as legal framing or legal consciousness, are blurred. In an effort to clarify the term, Lehoucq and Taylor suggest defining legal mobilisation as “the use of law in an explicit, self-conscious way through the invocation of a formal institutional mechanism” (Lehoucq & Taylor 2020: 178). In doing so, they seek to distinguish legal mobilisation from other forms of action where legal institutions are not engaged or put “into action”, where official law is only referred to implicitly, or where conflict resolution relies on other norms than official state law. Even though this rather narrow definition proves to be empirically useful, it does not fully capture the complexity of conflict transformation and the grey zones or shadows of the law and its institutions: Several research findings conclude that conflict resolution does not evolve in a linear manner towards the use of courts or similar legal institutions, but is instead dynamic, moving back and forth. In addition, only a small share of conflicts reach legal institutions, i.e., conflict resolution via official legal procedures is anything but the norm, at least in everyday life outside prison (e.g., Genn et al. 1999; Currie 2009; World Justice Project 2019; Pleasence et al. 2013; van Velthoven & Voert 2005).

With regard to these dynamics, the metaphor of the “dispute tree”, introduced by Albiston et al. (2014) permits a better grasp of the position of the law and its institutions in conflict resolution, taking grey zones of the law into account. By distinguishing “branches”, “flowers” and “fruits”, Albiston et al. illustrate the complex and vivid dynamics of conflict resolution: Different ways of handling a conflict (branches) generate different outcomes, i.e. symbolic recognition (flowers) or material remedies (fruits) (Albiston et al. 2014: 108–110). If the law is perceived as only one specific branch beside other means of conflict resolution, it becomes evident that legal mobilisation can only be understood in its context. In doing so, a change of perspective becomes possible and allows for a more comprehensive analysis of conflict resolution in its social embedding: “the tree metaphor not only invites questions about whether and how individuals climb a given tree but also examines the conditions under which a particular tree and its many branches will flourish or die. It also sweeps more broadly to consider the overall health of the forest as well as individuals’ paths through that forest.” (Albiston et al. 2014: 109).

To assess this complexity of conflict resolution, Morrill’s broader understanding of legal mobilisation as “the social process through which individuals define problems as potential rights violations and decide to take action within and/or outside the legal system to seek redress for those violations” (Morrill et al. 2010: 654) appears helpful. This definition not only stresses the necessity of identifying a situation as a violation of rights (and not, for example, as an unmet need or as disrespect), but also opens the perspective on several modes of action: not only formal legal action, but also quasi-legal mobilisation, i.e. law-like procedures, and extralegal action, i.e. bilateral negotiation, self-help or covert action, come into focus (Morrill et al. 2010: 655). Such a comprehensive analytical perspective permits a better assessment of the role of legal institutions or formal mechanisms in intersectional, potentially simultaneous, and heterogenous paths of conflict resolution.

Before further discussing the pertinence of these conceptual aspects for violence as a particular type of problem in prison, central findings concerning the embeddedness of violence in detention will be delineated.

Violence in prison as a particular type of conflict: From normality to rights violation

Researchers have been studying prison violence since the 1940s, stressing its relative normality as well as providing different explanations for its extensive occurrence. Prisons are total institutions (Goffman 1973; Dollinger & Schmidt 2015). The legitimate use of direct coercive force by staff under certain circumstances, a strict control regime, institutional conditions that can be understood as structural violence (Galtung 1975; Grant-Hayford & Scheyer 2016: 2) as well as the so-called “pains of imprisonment” (Sykes 2007 [1958]: 286; Crewe 2011) can be seen as an integral part of punishment and shape prisoners’ everyday experience.

Several approaches try to explain the increased level of violence in prisons: On the one hand, the so-called deprivation theory ascribes violent behaviour in prison to the negative effects of imprisonment and understands it as an adaptation to prison culture (“prisonisation”) and its subcultural rules (Clemmer 1968 [1940]; Sykes 2007 [1958]). On the other hand, the importation model explains violence by the fact that inmates not only bring their aggression and their dysfunctional problem-solving mechanisms into prison, but also “import” their informal hierarchies (Irwin & Cressey 1962; Rowe 2007). Recent studies confirm the link between experiences of violence in childhood and perpetration but also victimisation in prison (e.g., Bieneck & Pfeiffer 2012: 26; Hofinger & Fritsche 2021: 48–52). Neuber refers to the interconnectedness of biographical conflicts of autonomy and dependence and interprets violent action in prison as a form of defending painful biographical experiences (Neuber 2009: 86). Thus, violence has often been internalised as a normal, legitimate and everyday means of conflict resolution. But neither the importation of aggression nor deprivation caused by imprisonment fully explain a given level of violence in prison. Thus, integrative approaches not only incorporate management aspects (e.g., Huebner 2003) and situational factors (e.g., Gadon et al. 2006; Wortley 2002) but also consider the legitimacy of the prison regime (Sparks et al. 1996; Sparks & Bottoms 2008)[9] or the perception of the prison’s social climate and its interaction with violence and victimisation (Crewe & Liebling 2015; Liebling 2011; Snacken 2005; Liebling & Arnold 2004; Skar et al. 2019). Research on the prison climate (Ross et al. 2008: 447; Auty & Liebling 2020) shows that detention conditions, particularly if they are experienced as dehumanising, unfair or illegitimate, can promote alienation, aggression or violence (Hofinger & Fritsche 2021: 88–102; Klatt et al. 2017). In any case, regardless of the extent of violence experienced or exercised, the individual is urged to relate to prevailing rules in prison, and thus also to violence (Neuber 2009: 40; Neubacher & Boxberg 2018: 195).

In addition, other subcultural norms shape everyday life in prison and are intertwined with violence: Hierarchies and (sub-)group membership need to be respected, and a clear dividing line between staff and inmates (Chong 2014: 106–119) establishes loyalty among inmates as an overriding norm. Violence can be used to gain respect and prestige and avoid subordination. In addition, the male character of prison subculture – with manifestations such as the devaluation of sensitivity and vulnerability, and the revaluation of strength and dominance – contributes not only to the normality of violence but also shapes reactions to it (e.g., Chong 2014; Boxberg & Bögelein 2015; Neubacher & Boxberg 2018; Bereswill 2004a, 2004b): Performing “artificial hypermasculinity” (Bereswill 2006: 244 referring to Toch 1998– own translation) goes hand in hand with stereotypical constructions of masculinity linked to strength, toughness and invulnerability as well as to the demarcation and devaluation of femininity (e.g., Bereswill 2006: 243; Lamott 2014: 320; Neuber 2009: 189). Demonstrating masculinity also serves as a form of collective defence mechanism to mask vulnerability, denying weakness and fear (Bereswill 2006: 247–252). Those who are unable to establish their position as strong and assertive run a greater risk of becoming a victim. However, the boundaries between perpetrator and victim are blurred – victims easily become perpetrators at another time (Hofinger & Fritsche 2021: 194–196; Toman 2019).

Taking these different aspects into account, the subcultural embeddedness makes violence an omnipresent reference point, co-determining behaviour in prison. Violence plays a role in negotiating boundaries and social affiliation, but also in the inmates’ understanding of themselves and their relationship with others. Nevertheless, even if prison violence is “embedded” in its (sub-)cultures, it constitutes a violation of legal rights, is – often – sanctionable, threatens the person’s integrity, and potentially damages identities. Even if it is not possible and perhaps not even desirable that every violent incident is officially reported, better protection against violence for prisoners is an important goal, from both the perspective of human rights as well as that of rehabilitation.

Legal mobilisation in the case of violence – empirical findings

In the Austrian study, it was found that 72 % of the surveyed prisoners (n=386) had encountered at least one violent incident during imprisonment. The research revealed that 70 % of inmates experienced psychological violence, 41 % physical violence, and 10 % sexual violence or harassment (Hofinger & Fritsche 2021: 107). This means that nearly three-quarters of prisoners could have possibly mobilised the law to deal with their experience of violent victimisation. However, filing a complaint or reporting the incident to the authorities is not common practice. Many instances of violent victimisation that could warrant criminal prosecution were not reported.

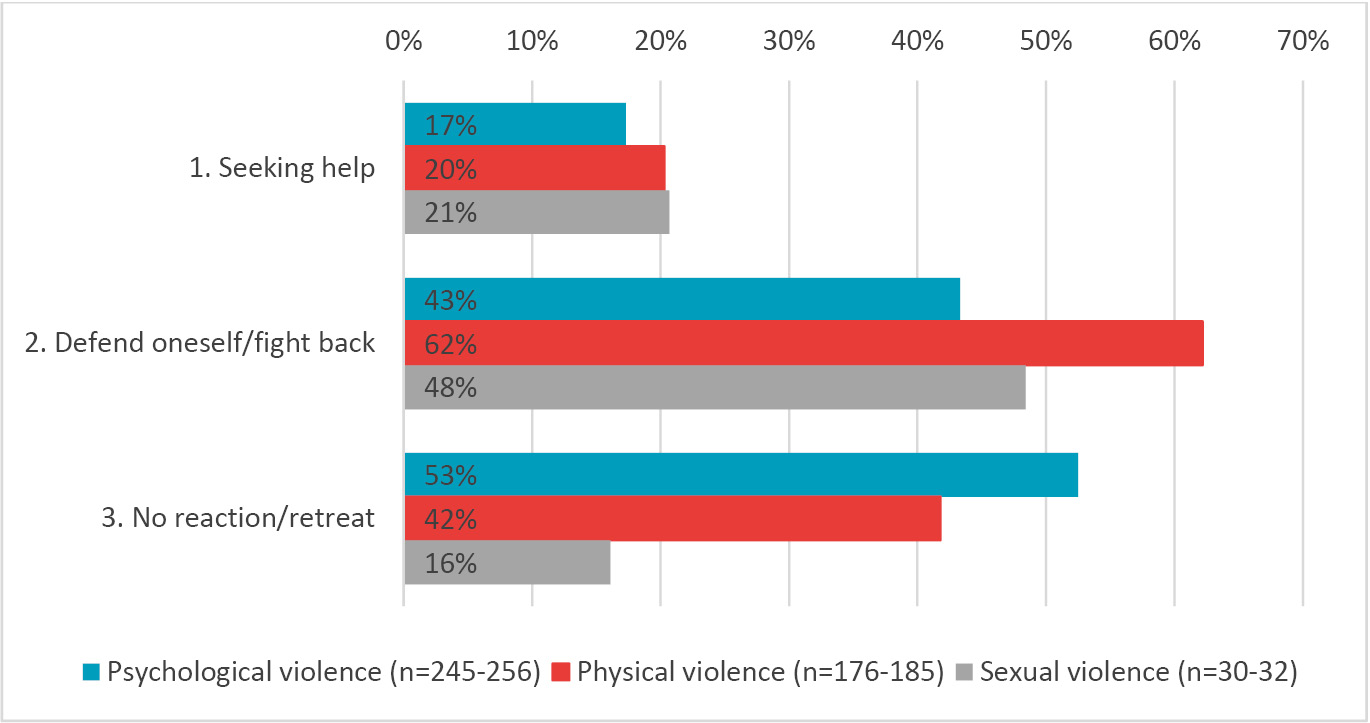

Looking at the types of reaction to the different forms of violence in prison (figure 1) it becomes evident that, firstly, seeking help is quite unpopular: On average, only a maximum of one-fifth stated that they had at least once proactively sought help (from fellow inmates or staff), reported the incident or accepted help offered. Secondly, a relatively high proportion of prisoners who experienced physical violence (62 %) or psychological violence (43 %) responded with some sort of verbal or physical self-defence. Thirdly, quite a lot of incidents resulted in a sense of helplessness, leading to retreat and withdrawal: More than half of the victims of psychological violence and 42 % of the victims of physical violence stated that, at certain moments, they were unable to do anything about it, felt defenceless or kept quiet to avoid trouble.[10]

Reactions to reported incidents in prison according to form of violence[11]

In general, and not surprisingly, severe forms of violence come to the attention of the institution more often than less severe forms, physical violence more often than psychological violence. To better understand how violence is dealt with in prison, we asked the surveyed prisoners to describe in detail one incident of each type of violence (psychological, physical and sexual). How did they react when they were attacked or abused? Whom did they tell about it? Did they file a complaint?

Most frequently, i.e., in about 40 % of the incidents described in detail[12], fellow inmates were informed. Apart from other inmates, prison officers played an important role as addressees of complaints – 35 % of the respondents said that they had informed a prison officer in the case of physical violence, 29 % in the case of psychological and 25 % in the case of sexual violence or harassment. In addition, between 17 % and 27 % mentioned social or psychological services, and between 11 % and 20 % friends or family as persons to contact. Institutions outside the prison walls, such as the Ombudsman’s Office (“Volksanwaltschaft”) or Austria’s main victim protection organisation (“Weißer Ring”) played a very limited role.

For the subjectively most serious incidents data is available on the proportion of inmates who filed an official report or complaint to the prison management or a prison officer, the ministry, or the police (Hofinger & Fritsche 2021: 265–267): Only 23 % of the cases of psychological violence described in detail (n=249) filed a complaint or an official report, 19 % in the case of physical violence (n=174) and four persons (14 %) in the case of sexual violence (n=28).

In comparison with findings from other countries on the use of complaint procedures and legal mobilisation in prison that speak of “extensive use” or a “central role” of legal complaint mechanisms (Dâmboeanu et al. 2021: 132; van der Valk et al. 2022: 280; Calavita & Jenness 2013: 51), figures of around 20 % seem very low. Calavita and Jenness speak of more than 70 % having filed a grievance at least once, though concerning any sort of problem (Calavita & Jenness 2013: 66); Dâmboeanu et al. state that of 75 % of prisoners who experienced any rights violation in prison, half had filed a complaint at least once (Dâmboeanu et al. 2021: 128) – though again, problems were not limited to violent incidents. Therefore, and given the distinct role of violence in prison, it is reasonable to assume that legal mobilisation for this particular type of problem follows different rules, both, to those governing the general use of complaint procedures in prison, as well as to the reporting culture outside prison, and is worth discussing in more detail.

Explaining mobilisation behaviour in the context of prison violence

In order to understand mobilisation behaviour in the case of prison violence, it is helpful, from an analytical point of view, to begin with the three-stage model of conflict transformation (Felstiner et al. 1980–81). Although a high percentage of inmates reported and thus named violence in the interviews, it is important to note, that naming violence during an anonymous interview is different from naming it in everyday prison life: In the interviews, respondents were only asked to confirm or deny whether a certain situation, such as excessive shouting, slapping or pushing, had occurred. Its classification as violence was a decision made by the researcher. In everyday prison life, however, such incidents have to be perceived and classified as “violence” by the individuals themselves, without any “framing support” from the interviewer. As already suggested above, several factors in prison can inhibit the framing of such incidents as violence and thus further influence conflict transformation.

Contested definitions of violence

To begin with, definitions of violence are often contested or vague. What is understood, for example, as psychological violence, depends largely on subjective assessments of a situation, on individual or group norms, as well as on situational contexts (e.g., Kapella et al. 2011: 84–90; Blackstone et al. 2009: 655). Apart from some forms with a relatively narrow definition of violence, for example those defined in criminal law, scientifically sound, systematic definitions of the severity of violence are not always available (Kapella et al. 2011: 54; 117–118). In practice, depending on previous experiences, expectations towards the other person, the social environment, or a specific situational context, one and the same incident may be interpreted by one person as violence, by another as rudeness, disrespect or even as a legitimate means of conflict resolution.

Given the nature of prisons as total institutions, the lines between the pains of imprisonment, structural violence, the regime of “penality”[13] (Sexton 2015), manifestations of a bad social climate, and personal violence are generally blurred. This was evident when inmates were asked, for example, to describe in their own words the subjectively most serious incident of psychological violence they had encountered: Every tenth inmate referred to incidents that could also be subsumed under unfair or arbitrary treatment and thus be understood as part of a negative social climate in prison. Hence there is a certain probability that in these cases the understanding of such incidents as violence was determined by the interviewer rather than the interviewee. The complex but also elusive nature of some forms of violence was similarly addressed on several occasions in the qualitative interviews. For example, one inmate stated that shouting in and of itself would not constitute violence for her. However, ongoing or aggressive shouting without reason, especially when it undermines basic human rules of communication and opportunities to be heard, would culminate in psychological violence; an interpretation that overlaps with definitions of structural violence as well as with the pains of imprisonment as such. Other interviewees put violence into perspective, for example, brawls in the context of a football match were rated as less dramatic than the lack of opportunities for sport; incomprehensible or unfair sanctions were rated as more stressful and rather classified as psychological violence than direct verbal abuse (Hofinger & Fritsche 2021: 127–140). Thus, depending on the specific understanding and context, a situation can be perceived and named as violence, as normality or even as a deserved part of punishment. The perceived quality, and thus the labelling of an incident as violence or something else, also affects the attribution of blame and linked responses. The more a situation becomes normal or habitual, the less likely it is to be recognised as personal violence and as a violation of basic rights; opportunities for intervention that could bring relief or prevent further escalation may then be overlooked.

Normality and masculinity as perception and claiming barriers

Connected to this, the link between (stereotypically constructed) masculinity and victimhood is of further importance for conflict transformation, since naming, but even more so blaming and claiming, presupposes self-identification as a victim. According to Holder, the linked “consciousness of victimisation” is “rooted in internal psychological and cognitive processes that constantly interpret, re-interpret, construct, and re-construct the bounds of what is normal and understandable or even permissible and expected” (Holder 2017). In a predominantly male prison culture, this process of re-interpretation and reconstruction is particularly challenging because victimhood and masculinity are quite contradictory concepts. The “male victim” still seems to be a cultural paradox (Neuber 2014: 75) – in public discourses men are still primarily constructed as perpetrators, women as victims. Identification as a victim contradicts the ideal of a (stereotypical) male ego and is therefore generally risky for the self-image (e.g. Mosser 2015: 179; Puchert & Scambor 2012; Lenz 2012). As long as some forms of violence are still part of “doing masculinity” (Neuber 2014: 78), naming violence faces paradoxical challenges: On the one hand, experiences that are understood as a normal part of male biographies, such as involvement in fights, cannot be named or even perceived. On the other hand, it is not possible to address aspects that contradict one’s own concept of masculinity – out of shame or because they endanger one’s identity (Jungnitz et al. 2004: 18; Schröttle 2016: 114). This is particularly true for sexual violence or harassment, but also for other forms of violence. Due to this complicated nature of violence within male subcultures, conflict transformation faces additional obstacles. Illustrated links between victimhood, weakness and masculinity may refer to self-blame of not being “man enough”, and – as Felstiner et al. put it, “[p]eople who blame themselves for an experience are less likely to see it as injurious, or, having so perceived it, to voice a grievance about it” (Felstiner et al. 1980–81: 641).

However, the normality of violence is not only a question of individual self-perception, but an inherent characteristic of the social environment as such. This is reflected in the high prevalence rates, with almost three quarters of respondents stating that they had experienced at least one violent incident. In addition, data on the perceived social climate and the detention conditions also point to the normalisation of some forms of violence. Almost half of the respondents had observed physical violence between prisoners on several occasions, and a similar share said that there was a lot of fighting between prisoners. About one in six prisoners had observed physical violence between prisoners and staff on several occasions. Indications of a certain normality of what could be classified as psychological violence are evident in the fact that one in three inmates report that they (rather) do not feel treated as human beings, and a similar number (rather) agree that staff treatment is often dismissive (Hofinger & Fritsche 2021: 82). Not feeling treated as a human being can also undermine one’s sense of entitlement, as the idea of having rights and being able to make demands can be weakened. And, as van der Valk and Rogan note, as long as there is a “low bar for what constitutes ‘bad treatment’, it is not surprising that we see prisoners not making formal complaints about what happens to them; they simply ‘get on with it’” (van der Valk & Rogan 2023: 7). Thus, due to the normality of violence, the triviality threshold of what is perceived as violence and for what one can seek redress seems to be rather high in prison.

Ambiguous quality and accessibility of institutional claiming mechanisms

Moving on to the act of claiming in a narrower sense, i.e., involving the prison administration or external institutions as addressees, the picture becomes more complex: Even when incidents are named and labelled as violence, the data show that solutions are often limited to self-help, avoidance of risky situations or inaction – corresponding to Morrill’s category of “lumping” (Morrill et al. 2010: 655). This is particularly surprising given that violent victimization is not merely a grievance, but can be punishable under criminal law. One might expect that, at least in serious cases or those involving staff, official mechanisms would be readily used. However, in prison several aspects limit the utilization of official complaint channels (§ 120–122 StVG, Penitentiary System Act), such as filing a complaint with the prison director, the competent court or the Ministry of Justice as the highest prison authority or filing a criminal charge.

Despite assertions from other studies that “prison erases socio-economic differences” (Dâmboeanu et al. 2021: 134) and therefore factors such as education, economic resources, or class attribution cannot explain mobilisation behaviour within prison as they do outside, the challenges stemming from lack of resources and cultural capital persist in accessing official complaint mechanisms in the case of Austria: About two-thirds of the interviewees had a first language other than German, and about one in four prisoners had spent less than one year in Austria at the time of the study; the educational level is generally low. These aspects can influence legal knowledge, but also the sense of entitlement. Data show that, even though complaints can also be lodged in the person’s first language, prisoners who are Austrian citizens complain disproportionately often to the Ministry, thus, language skills and origin seem to influence complaint behaviour (Kompetenzstelle Rechtsschutz der Generaldirektion für den Strafvollzug und den Vollzug freiheitsentziehender Maßnahmen 2019).

In addition, access to “mediating agents” (Albiston et al. 2014: 115), who could support claims or strengthen the sense of entitlement, is limited in Austrian prisons: There is a severe shortage of staff, especially of social or special services (Rechnungshof Österreich 2024: 70–84). External and independent institutions such as visiting committees were relatively unknown to the respondents at the time of the study. Two-thirds of them (n=170) could not name an external institution, such as ombuds offices or victim support organisations (Hofinger & Fritsche 2021: 266). Even informal support is scarce. Depending on the type of institution and the type of detention, up to 50 % of detainees (n=376) reported that they never receive visitors – actors that could possibly help with procedures or with accessing legal aid outside prison walls.

A significant number of respondents anticipate that complaints will not be effective and mention this as their reason for not taking action: one fifth of those who did not complain officially (21 % for each form of violence)[14] did so because they were convinced that complaints would be useless, thus “wasted agency” (van der Valk & Rogan 2023: 9). 13 % (psychological violence) and 10 % (physical violence) stated that they would not be believed anyway. In line with findings in other countries, success rates and satisfaction with the procedures are in fact rather low in cases where complaints have been lodged. In addition, due to the overlapping of the roles of victim and perpetrator, official mobilisation can also have unintended effects: Around 40 %[15] said that they had been held jointly responsible for the incident after making an official complaint. On the one hand, complaining is risky because it can lead to an unwanted transfer to another department, or to the loss of previously acquired privileges. On the other hand, complaints often have no consequences, especially in cases where staff are accused: For 2019, official data show that only 3 % of complaints against staff led to prosecution, and in only one case was the perpetrator convicted (BMAEIA 2020). The available data suggest that little effort is made to clarify allegations and arrive at a nuanced assessment of the conflict (Hofinger & Fritsche 2021: 279). However, satisfying, accurate and effective official handing of violent conflicts would be particularly important as ineffective complaint mechanisms (e.g., if not dealt with in time) or perceptions of procedural injustice can not only undermine a person’s sense of entitlement but may also contribute to more violence (Bierie 2013: 23).

The role of extralegal mobilisation

Although these findings suggest that recourse to institutional mechanisms is not the most promising choice for prisoners, other studies conclude that, despite low success rates, legal mobilisation in prison does take place extensively due to the lack of other forms of redress (Calavita & Jenness 2013: 70). Therefore, a second perspective must be considered to explain the low rates of official claims in cases of violence. As outlined above, violence in prisons not only “happens” but serves an important purpose: it establishes or stabilises hierarchies and often constitutes a rather normalised means of conflict resolution among prisoners. Some explanations for the reluctance to make official claims can be found in subcultural laws themselves, which could also be understood as a particular form of “higher law” or “law above the law” (Halliday & Morgan 2013: 18). Responses to the question of why victims did not report incidents reveal the importance of subculture as a barrier to making an official claim: Around one-third of those who provided detailed information about an incident of psychological or physical violence that had not been officially reported explicitly cited subcultural norms: Reasons for not reporting included statements such as “you don’t do that in prison” or “so I wouldn’t be considered a traitor” or “I was threatened not to tell anyone”. These responses refer to subcultural norms against snitching, a norm closely linked to stereotypical masculine culture, but also to the rather strict boundary between staff and inmates. To snitch implies to be unable to help oneself, to be weak and to need help from the prison system which is often framed as “the other”. For some inmates, beating someone up is less morally repugnant than snitching because the latter jeopardises the basis of solidarity, as one interviewee explained: “I think one of the most reprehensible things that people do (…) is betrayal and snitching. (…) you try to get along with your fellow sufferers, also in the sense that you kind of stick together”. Official reporting of violent incidents not only goes against such in-group solidarity, but also carries real risks of exclusion, defamation and even violent sanctions by fellow inmates.

Subcultural norms not only explain why prisoners often refrain from making official claims, but also help to broaden the perspective on other forms of claiming. To fully understand mobilisation behaviour in prison, forms of extralegal claiming (Morrill et al. 2010: 655) must also be considered. As outlined above, prisoners quite often inform fellow inmates, prison officers, but also social services, friends or family about the incidents. These informed actors can either act as “mediating agents” (Albiston et al. 2014: 115), selecting promising cases from unpromising ones, or they can become addressees for complaints in their own right. Although in some cases official claims accompany or follow such informal complaints, this is not the norm. Rather, data suggest that responses to violence often do not go beyond such unofficial forms of redress. While informing others without making an official claim may be seen as constructive conflict resolution, other subcultural ways of resolving conflict are more worrying: As figure 1 above shows, “dyadic conflict resolution” (Hanak et al. 1989: 27) such as defending oneself or fighting back, i.e., responses that do not involve third parties, seems to be particularly prominent in cases of violence between prisoners. Fighting back is also aimed at preventing further victimisation, as according to respondents, life in prison is more dangerous for the weak, for those who have not yet established a position within the subculture, and those who are unable to defend themselves (Hofinger & Fritsche 2021: 78).

In analysing the reluctance of victims of discrimination to complain, Bumiller points to the role of the relationship between victim and offender as one explanation, arguing that “the bonds between the perpetrator and the discrimination victim drive the conflict to self-destructive or explosive reactions” (Bumiller 1987). Even if Bumiller developed her concept in the context of discrimination, her argument can be adapted to the situation in prison: Co-inmates are a significant reference group for the individual. Complex inter- and intragroup hierarchies lead to multifaceted dependencies. Although relationships between prisoners, particularly among different subgroups, cannot generally be characterised as intimate, bonds are most often closer than those with staff. Consequently, insights from the legal mobilisation literature suggesting that official avenues are less frequently pursued in conflicts involving socially close adversaries (Blankenburg 1995: 43) appear to be applicable to prison violence among inmates. Similarly to Bumiller’s second explanation regarding the reluctance of victims of discrimination to complain, prisoners also often seem to be hesitant to use official channels for conflict resolution, “because they shun the role of the victim, and they fear legal intervention will disrupt the delicate balance of power between themselves and their opponents” (Bumiller 1987: 438). Even though official law or procedures can in general be a powerful and efficient means of conflict resolution, from the prisoners’ perspective this does not seem to be fully true for official complaint mechanisms in prisons. Filing official claims carries the risk of losing control over one’s situation (Bumiller 1987) and requires the claimants to reconcile what Merry calls the “double subjectivity” (Merry 2006: 181) – as rights holders and claimants fighting against rights violations, and as victims with notions of powerlessness and subcultural rejection. Extralegal paths can, particularly for victims of violence, people in precarious situations and for conflicts in complex social relations, appear more helpful and less demanding (Bumiller 1987: 433f.; Levine & Mellema 2001).

Our data suggest that recourse to subcultural mechanisms of conflict resolution can also mean opting for an “ethic of survival” (Bumiller 1987: 438) or the “relative normalcy of day-today life” (Bumiller 1987: 437). Using Albiston et al.’s notion of the conflict tree (Albiston et al. 2014), defensive behaviour could then be understood as a particular “branch” of conflict resolution with different outcomes – depending on the perspective: From the prisoner’s point of view, this subcultural form of extralegal claiming can bring recognition and increased prestige within the prison’ population: Being able to defend oneself autonomously can then be translated into strength, masculinity and loyalty – in the words of Albiston “flowers”, such as status rewards from fellow inmates, or even produce “fruits”, such as receiving scarce goods like cigarettes, etc. From an external perspective though, the “fruits” and “flowers” of these extralegal claiming mechanisms are different: Counterassaults, stricter, opaque and perhaps ungovernable hierarchies, and the oppression of already marginalised groups can exacerbate conflicts and contribute to a cycle of violence.

Conclusio: Accessible and fair procedures, constructive ways of extralegal claiming

Theoretically framed by a legal mobilisation perspective, the article puts selected findings from an empirical study on violence in Austrian prisons (Hofinger & Fritsche 2021) into a new perspective. While the scarce existing literature on legal mobilisation in prisons often neglects the specific type of problem in mobilisation choices, we discussed the particular characteristics of violence in prisons and their role in conflict transformation processes. Whereas existing literature on legal mobilisation in prison concludes that, unlike in everyday life outside prison, the use of legal mechanisms and administrative grievance procedures is rather common in prison (Dâmboeanu et al. 2021: 132; van der Valk et al. 2022: 280; Calavita & Jenness 2013: 51), the Austrian data shows that in the case of violence, official complaints are only filed in a limited number of cases. The handling and consequences of official complaints by the prison system are not always appropriate and can be risky for the individual; access to official claiming is not always effectively supported: Specialised staff and social services that could mediate conflict transformation or facilitate access to independent complaints bodies are scarce; lack of resources, comparatively high rates of prisoners with low levels of education, different backgrounds in legal culture, legal and linguistic capacities, and insufficient opportunities for low-threshold complaints can hinder access to justice.

All in all, we did not find a general “rights claims atmosphere” (Dâmboeanu et al. 2021: 129) in cases of violence in Austrian prisons. In addition to socio-economic and structural barriers, explanations for the rather low rates of claiming were found in particular in the prisoner subculture. Definitions of violence are contested; the normality of violence, but also the fact that only specific forms of violence are enforceable under criminal law, implies a rather high triviality threshold. The stigma of victimhood in a stereotypically male environment, the strict boundaries between staff and inmates and associated expectations of solidarity within the prison population, as well as risks of defamation, exclusion or counter-violence, if experiences of violence are made public, inhibit naming, promote self-blame, and also hinder official claiming. Since the dynamics of violence are largely determined by subcultural norms, its management largely escapes institutional mechanisms.

Nevertheless, the analysis showed that legal mobilisation in prisons must be considered in its multi-dimensional and dynamic nature, and can only be fully understood by applying a broad definition that includes quasi-legal and, above all, extralegal mobilisation.

One explanation in studies that find high rates of legal mobilisation is that in prison, unlike in everyday life, the law is not subtextual but explicit, and “an unavoidable master text” (Calavita & Jenness 2013: 73). It thus influences processes of naming, blaming, and claiming, and may ultimately increase prisoners’ mobilisation of the law (Calavita & Jenness 2013: 52). However, given the normality of violence in prison and the often overriding relevance of subcultural norms that can amount to a “higher law” or “law above the law” (Halliday & Morgan 2013: 18), we suggest that, in the case of violence. extralegal forms of conflict resolution are more relevant than formal legal mobilisation. Whereas in other forms of conflicts, redress mechanisms other than official procedures may be lacking (Calavita & Jenness 2013: 69), the “living law” (Ehrlich 1936: 486–506) in prison, i.e., subcultural norms and dynamics, seems to provide an alternative path to conflict resolution in the case of violence.

In addition to inaction, i.e., “lumping” in the words of Morrill (2010: 655), solutions are often found in extralegal responses, when non-legal or non-institutional actors are informed or inmates opt for direct, i.e., dyadic conflict resolution. Such extralegal claiming is not in itself problematic. But only as long as the dyadic conflict resolution is constructive and does not, as in many cases, culminate in violent self-defence that feeds the cycle of violence.

Albiston et al.’s metaphor of the “dispute tree” (Albiston et al. 2014) facilitates a clearer understanding of approaches that can both improve access to justice and strengthen constructive ways of dealing with violence. Branches of official complaints procedures and extralegal, subculturally oriented ways of conflict resolution exist side by side. While the former are often difficult to access, demanding or risky, the latter can only be constructive if the addressees of informal complaints – such as social services, fellow inmates, but also prison staff – are aware of their role as “mediating agents” (Albiston et al. 2014: 115) or “agents of transformation” (Felstiner et al. 1980–81: 639–649). As such, they could act as gatekeepers to constructive – formal-, quasi- or extralegal – forms of conflict resolution and facilitate the flourishing of those branches that do not reinforce counter-violence.

Findings on barriers to naming violence, but also on subcultural notions of victimhood, suggest that in order to contribute to the “overall health of the forest” (Albiston et al. 2014: 109) in prison, preliminary stages of claiming – i.e., naming and blaming – also have to be considered in addressing responses to violence. Additionally, challenges in reconciling conflicting subjectivities – as rights holders or claimants, victims of violence but also as respectable fellow prisoners – can influence claiming behaviour. Given the dynamics and interdependence of different forms of violence, but also the intersections between the social climate, the pains of imprisonment and personal violence, less severe forms of violence that do not exceed the threshold for criminal sanction must also be taken into account. In line with van der Valk and Rogan, it must be emphasised firstly that formal procedures “do not replace the need for decent conditions, fair treatment and good relations, which make the use of complaints procedures unnecessary in the first place” (van der Valk & Rogan 2023: 9). Secondly, further discussion is needed on how to alter existing subcultural meanings of victimhood and the “prestige” associated with some forms of violence. According to these findings, not only easy access to good quality institutional legal procedures seems necessary. Unless destructive forms of extralegal claims are channelled to extra- or quasi-legal ways of conflict resolution that provide safe or even empowering spaces for victims, violence will remain an important means to establish and uphold prison hierarchies and “solve” conflicts.

References

Albiston, Chatherine R., Edelman, Lauren B. & Milligan, Joy (2014) The Dispute Tree and the Legal Forest. The Annual Review of Law and Social Science 10: 105–131.10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-110413-030826Search in Google Scholar

Auty, Katherine M. & Liebling, Alison (2020) Exploring the Relationship between Prison Social Climate and Reoffending. Justice Quarterly 37: 358–381.10.1080/07418825.2018.1538421Search in Google Scholar

Baer, Susanne (2021) Rechtssoziologie: Eine Einführung in die interdisziplinäre Rechtsforschung. Baden-Baden: Nomos.10.5771/9783748903079Search in Google Scholar

Baier, Dirk & Bergmann, Marie Christine (2013) Gewalt im Strafvollzug – Ergebnisse einer Befragung in fünf Bundesländern. Forum Strafvollzug 62: 76–83.Search in Google Scholar

Bereswill, Mechthild (2004a) Gewalt als männliche Ressource? Theoretische und empirische Differenzierungen am Beispiel junger Männer mit Hafterfahrungen, S. 123–140 in Siegfried, Lamnek & Manuela Boatca (Eds.), Geschlecht – Gewalt – Gesellschaft. Opladen: Leske & Budrich.10.1007/978-3-322-97595-9_7Search in Google Scholar

Bereswill, Mechthild (2004b) “The Society of Captives” – Formierungen von Männlichkeit im Gefängnis. Aktuelle Bezüge zur Gefängnisforschung von Gresham M. Sykes. Kriminologisches Journal 36: 92–108.Search in Google Scholar

Bereswill, Mechthild (2006) Männlichkeit und Gewalt. Empirische Einsichten und theoretische Reflexionen über Gewalt zwischen Männern im Gefängnis. Feministische Studien 24: 242–255.10.1515/fs-2006-0207Search in Google Scholar

Bieneck, Steffen & Pfeiffer, Christian (2012) Viktimisierungserfahrungen im Justizvollzug. KFN-Forschungsberichte Nr. 119.Search in Google Scholar

Bierie, David M. (2013) Procedural justice and prison violence: Examining complaints among federal inmates (2000–2007). Psychology, Public Policy, and Law 19: 15–29.10.1037/a0028427Search in Google Scholar

Blackstone, Amy, Uggen, Christopher & McLaughlin, Heather (2009) Legal Consciousness and Responses to Sexual Harassment. Law & Society Review 43: 631–668.10.1111/j.1540-5893.2009.00384.xSearch in Google Scholar

Blankenburg, Erhard (1995) Mobilisierung des Rechts: Eine Einführung in die Rechtssoziologie. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer.10.1007/978-3-642-57870-0Search in Google Scholar

Boxberg, Verena & Bögelein, Nicole (2015) Junge Inhaftierte als Täter und Opfer von Gewalt – Subkulturelle Bedingungsfaktoren. Zeitschrift für Jugendkriminalrecht und Jugendhilfe 3: 241–247.Search in Google Scholar

Boxberg, Verena, Fehrmann, Sarah, Häufle, Jenny, Neubacher. Frank & Schmidt, Holger (2016) Gewalt und Suizid als Anpassungsstrategien? Zum Umgang mit Belastungen im Jugendstrafvollzug. Monatsschrift für Kriminologie und Strafrechtsreform: 428–449.10.1515/mks-2016-990567Search in Google Scholar

Bumiller, Kristin (1987) Victims in the Shadow of the Law. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 12: 421–439.10.1086/494337Search in Google Scholar

Calavita, Kitty & Jenness, Valerie (2013) Inside the Pyramid of Disputes: Naming Problems and Filing Grievances in California Prisons. Social Problems 60: 50–80.10.1525/sp.2013.60.1.50Search in Google Scholar

Calavita, Kitty & Jenness, Valerie (2014) Appealing to Justice: Prisoner Grievances, Rights, and Carceral Logic. Berkeley: University of California Press.Search in Google Scholar

Caravaca-Sánchez, Francisco, Aizpurua, Eva & Wolff, Nancy (2023) The Prevalence of Prison-based Physical and Sexual Victimization in Males and Females: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Trauma, violence & abuse 24: 3476–3492.10.1177/15248380221130358Search in Google Scholar

Chong, Vanessa (2014) Gewalt im Strafvollzug. Tübinger Schriften und Materialien zur Kriminologie.Search in Google Scholar

Clemmer, Donald (1968 [1940]) The Prison Community. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.Search in Google Scholar

Crewe, Ben (2011) Depth, weight, tightness: Revisiting the pains of imprisonment. Punishment & Society 13: 509–529.10.1177/1462474511422172Search in Google Scholar

Crewe, Ben & Liebling, Alison (2015) Staff Culture, authority and prison violence. Prison Service Journal. Special Edition: Reducing Prison Violence 221: 9–14.Search in Google Scholar

Currie, Ab (2009) The Legal Problems of Everyday Life: The Nature, Extent and Consequences of Justiciable Problems Experienced by Canadians.10.1108/S1521-6136(2009)0000012005Search in Google Scholar

Dâmboeanu, Cristinav, Pricopie, Valentina & Thiemann, Alina (2021) The path to human rights in Romania: Emergent voice(s) of legal mobilization in prisons. European Journal of Criminology 18: 120–139.10.1177/1477370820966575Search in Google Scholar

Day, Andrew, Newton, Danielle, Cooke, David & Tamatea, Armon (2022) Interventions to Prevent Prison Violence: A Scoping Review of the Available Research Evidence. The Prison Journal 102: 745–769.10.1177/00328855221136201Search in Google Scholar

Dollinger, Bernd & Schmidt, Holger (2015) Zur Aktualität von Goffmans Konzept “totaler Institutionen”. Empirische Befunde zur gegenwärtigen Situation des “Unterlebens” in Gefängnissen, S. 245–259 in M. Schweder (Ed.), Handbuch Jugendstrafvollzug. Weinheim, Basel: Beltz Juventa.Search in Google Scholar

Ehrlich, Eugen (1936) Fundamental Principles of the Sociology of Law. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Engel, David M. & Munger, Frank W. (2003) Rights of Inclusion: Law and Identity in the Life Stories of Americans with Disabilities. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.10.7208/chicago/9780226208343.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Ewick, Patricia & Silbey, Susan S. (1998) The Common Place of Law: Stories from Everyday Life. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.10.7208/chicago/9780226212708.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Felstiner, William L. F., Abel, Richard L. & Sarat, Austin (1980–81) The Emergence and Transformation of Disputes: Naming. Blaiming. Claiming. Law & Society Review 15: 631–654.10.2307/3053505Search in Google Scholar

Fuchs, Gesine (2021) Rechtsmobilisierung: Ein Systematisierungsversuch. Zeitschrift für Rechtssoziologie 41: 21–43.10.1515/zfrs-2021-0003Search in Google Scholar

Gadon, Lisa, Johnstone, Lorraine & Cooke, David (2006) Situational variables and institutional violence. A systematic review of the literature. Clinical psychology review 26: 515–534.10.1016/j.cpr.2006.02.002Search in Google Scholar

Galtung, Johann (1975) Strukturelle Gewalt. Beiträge zur Friedens- und Konfliktforschung. Reinbek bei Hamburg: Rowohlt.Search in Google Scholar

Genn, Hazel, Beinart, Sarah, Finch, Steven, Korovessis, Christos & Smith, Patten (1999) Paths to justice: What people do and think about going to law. Oxford, Portland: Hart Publishing.Search in Google Scholar

Glaser, Barney G. & Strauss, Anselm (1998 [1967]) Grounded Theory: Strategien qualitativer Forschung. Bern: Huber.Search in Google Scholar

Goffman, Erving (1973) Asyle. Über die soziale Sitaution psychiatrischer Patienten und anderer Insassen. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.Search in Google Scholar

Gramatikov, Martin, Barendrecht, Maurits, Laxminarayan, Malini, Verdonschot, Jin Ho, Klaming, Laura & van Zeeland, Corry (2010) A Handbook for Measuring the Costs and Quality of Access to Justice. Apeldoorn, Antwerpen, Portland: Maklu.Search in Google Scholar

Grant-Hayford, Naakow & Scheyer, Victoria (2016) Strukturelle Gewalt verstehen. Eine Anleitung zur Operationalisierung.Search in Google Scholar

Halliday, S. & Morgan, B. (2013) I Fought the Law and the Law Won? Legal Consciousness and the Critical Imagination. Current Legal Problems 66: 1–32.10.1093/clp/cut002Search in Google Scholar

Hanak, Gerhard, Stehr, Johannes & Steinert, Heinz (1989) Ärgernisse und Lebenskatastrophen: Über den alltäglichen Umgang mit Kriminalität. Bielefeld: AJZ.Search in Google Scholar

Hofinger, Veronika & Fritsche, Andrea (2020) “Ich bin stark und mir passiert nichts“ – Forschungspraktische und methodische Erkenntnisse aus einer quantitativen Opferbefragung im Gefängnis. Monatsschrift für Kriminologie und Strafrechtsreform 103: 15–27.10.1515/mks-2020-2037Search in Google Scholar

Hofinger, Veronika & Fritsche, Andrea (2021) Gewalt in Haft: Ergebnisse einer Dunkelfeldstudie in Österreichs Justizanstalten. Wien, Münster: LIT.Search in Google Scholar

Holder, Robyn L. (2017) Victims, Legal Consciousness and Legal Mobilisation in A. Deckert & R. Sarre (Eds.), The Palgrave Handbook of Australian and New Zealand Criminology, Crime and Justice. London: Palgrave Macmillan.10.1007/978-3-319-55747-2_43Search in Google Scholar

Huebner, Beth M. (2003) Administrative determinants of inmate violence: A multilevel analysis. Journal of Criminal Justice 31: 107–117.10.1016/S0047-2352(02)00218-0Search in Google Scholar

Ireland, Jane L. & Ireland, Carol A. (2008) Intra-Group Aggression Among Prisoners: Bullyiing Intensity and Exploration of Victim-Perpetrator Mutuality. Aggressive Behaviour 34: 76–87.10.1002/ab.20213Search in Google Scholar

Irwin, John & Cressey, Donald R. (1962) Thieves, convicts and inmate culture. Social Problems 10: 142–155.10.2307/799047Search in Google Scholar

Jungnitz, Ludger, Puchert, Ralf & Walter, Willi (2004) Gewalt gegen Männer in Deutschland: Pilotstudie. Online: https://www.bmfsfj.de/blob/84590/a3184b9f324b6ccc05bdfc83ac03951e/studie-gewalt-maenner-langfassung-data.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

Kapella, Olaf, Baierl, Andreas, Rille-Pfeiffer, Christiane, Geserick, Christine & Schmidt, Eva Maria (2011) Gewalt in der Familie und im nahen sozialen Umfeld. Österreichische Prävalenzstudie zur Gewalt an Frauen und Männern.Search in Google Scholar

Klatt, Thimna, Suhling, Stefan, Bergmann, Marie Christine & Baier, Dirk (2017) Merkmale von Justizvollzugsanstalten als Einflussfaktoren von Gewalt und Drogenkonsum – Eine explorative Studie. Monatsschrift für Kriminologie und Strafrechtsreform 100: 250–271.10.1515/mkr-2017-1000403Search in Google Scholar

Kompetenzstelle Rechtsschutz der Generaldirektion für den Strafvollzug und den Vollzug freiheitsentziehender Maßnahmen (2019) Auswertung Beschwerdemanagement: 2. Halbjahr 2019.Search in Google Scholar

Lamott, Franziska (2014) Gewaltdynamiken in hierarchischen Welten. Gruppenpsychotherapie und Gruppendynamik 49: 316–330.10.13109/grup.2013.49.4.316Search in Google Scholar

Lehoucq, Emilio & Taylor, Whitney K. (2020) Conceptualizing Legal Mobilization: How Should We Understand the Deployment of Legal Strategies? Law & Social Inquiry 45: 166–193.10.1017/lsi.2019.59Search in Google Scholar

Lenz, Hans-Joachim (2012) Die kulturelle Verleugnung der männlichen Verletzbarkeit als Herausforderung für die Männerbildung, S. 317–328 in T. Tholen, S. M. Baader & J. Bilstein (Eds.), Erziehung, Bildung und Geschlecht: Männlichkeiten im Fokus der Gender-Studies. Jahrestagung 2009 der Kommission “Pädagogische Anthropologie” in der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Erziehungswissenschaft. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.10.1007/978-3-531-19112-6_18Search in Google Scholar

Levine, Kay & Mellema, Virginia (2001) Strategizing the Street: How Law Matters in the Lives of Women in the Street-Level Drug Economy. Law & Social Inquiry 26: 169–207.10.1111/j.1747-4469.2001.tb00175.xSearch in Google Scholar

Liebling, Alison (2011) Moral performance, inhuman and degrading treatment and prison pain. Punishment & Society 13: 530–550.10.1177/1462474511422159Search in Google Scholar

Liebling, Alison & Arnold, Helen (2004) Prisons and their moral performance: A study of values, quality, and prison life. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press.10.1093/oso/9780199271221.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Merry, Sally Engle (2003) Rights Talk and the Experience of Law: Implementing Women’s Human Rights to Protection from Violence. Human Rights Quarterly 25: 343–381.10.1353/hrq.2003.0020Search in Google Scholar

Merry, Sally Engle (2006) Human rights and gender violence: translating international law into local justice. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.10.7208/chicago/9780226520759.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Miller, Richard E. & Sarat, Austin (1980) Grievances, Claims, and Disputes: Assessing the Adversary Culture. Law & Society Review 15: 525.10.2307/3053502Search in Google Scholar

Morrill, Calvin, Edelman, Lauren B., Tyson, Karolyn & Arum, Richard (2010) Legal mobilization in schools: the paradox of rights and race among youth. Law & Society Review 44: 651–694.10.1111/j.1540-5893.2010.00419.xSearch in Google Scholar

Morrill, Calvin, Feddersen, Mayra & Rushin, Stephen (2015) Law, Mobilization of, S. 590–597 in J. D. Wright (Ed.), International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences. Amsterdam: Elsevier.10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.86059-6Search in Google Scholar

Mosser, Peter (2015) Erhebung (sexualisierter) Gewalt bei Männern, S. 177–190 in, Forschungsmanual Gewalt. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.10.1007/978-3-658-06294-1_10Search in Google Scholar

Neubacher, Frank & Boxberg, Verena (2018) Gewalt und Subkultur, S. 195–216 in S. Maelicke & B. Suhling (Eds.), Das Gefängnis auf dem Prüfstand. Zustand und Zukunft des Strafvollzugs. Wiesbaden: Springer.10.1007/978-3-658-20147-0_10Search in Google Scholar

Neubacher, Frank, Boxberg, Verena, Ernst, André, Fehrmann, Sarah E. & Schmidt. Holger (2018) Abschlussbericht zum Forschungsprojekt “Gewalt und Suizid unter weiblichen und männlichen Jugendstrafgefangenen – Entstehungsbedingungen und Entwicklungsverläufe im Geschlechtervergleich”.Search in Google Scholar

Neuber, Anke (2009) Die Demonstration kein Opfer zu sein. Biographische Fallstudien zu Gewalt und Männlichkeitskonflikten. Baden-Baden: Nomos Verlag.10.5771/9783845212517Search in Google Scholar

Neuber, Anke (2014) “Die Demonstration kein Opfer zu sein” – Ein geschlechtertheoretischer Blick auf Opferschaft, S. 75–91 in F. Leuschner & C. Schwanengel (Eds.), Hilfen für Opfer von Straftaten. Ein Überblick über die deutsche Opferhilfelandschaft. Wiesbaden.Search in Google Scholar

Pleasence, Pascoe, Balmer, Nigel J. & Sandefur, Rebecca L. (2013) Paths to Justice: A Past, Present and Future Roadmap. Report prepared under a grant from the Nuffield Foundation (AJU/39100).Search in Google Scholar

Pound, Roscoe (1910) Law in Books and Law in Action. American Law Review XLIV: 12–36.Search in Google Scholar

Puchert, Ralf & Scambor, Christian (2012) Gewalt gegen Männer. Erkenntnisse aus der Gewaltforschung und Hinweise für die Praxis. Polizei & Wissenschaft: 25–38.Search in Google Scholar

Rechnungshof Österreich (2024) Resozialisierungsmaßnahmen der Justiz: Bericht des Rechnungshofes.Search in Google Scholar

Rocheleau, Ann Marie (2015) Ways of coping and involvement in prison violence. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology 59: 359–383.10.1177/0306624X13510275Search in Google Scholar

Ross, Michael W., Diamond, Pamela M., Liebling, Alison & Saylor, William G. (2008) Measurement of prison social climate: A comparison of an inmate measure in England and the USA. Punishment & Society 10: 447–474.10.1177/1462474508095320Search in Google Scholar

Rowe, Abigail (2007) Importation model, S. 130–131 in Y. Jewkes & B. Jamie (Eds.), Dictionary of Prisons and Punishment. Cullompton: Wilian.Search in Google Scholar

Sandefur, Rebecca L. (2008) Access to Civil Justice and Race, Class, and Gender Inequality. The Annual Review of Sociology 34: 339–358.10.1146/annurev.soc.34.040507.134534Search in Google Scholar

Schröttle, Monika (2016) Methodische Anforderungen an Gewaltprävalenzstudien im Bereich Gewalt gegen Frauen (und Männer), S. 101–119 in C. Helfferich, B. Kavemann & H. Kindler (Eds.), Forschungsmanual Gewalt: Grundlagen der empirischen Erhebung von Gewalt in Paarbeziehungen und sexualisierter Gewalt. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.10.1007/978-3-658-06294-1_6Search in Google Scholar

Sexton, Lori (2015) Penal subjectivities: Developing a theoretical framework for penal consciousness. Punishment & Society 17: 114–136.10.1177/1462474514548790Search in Google Scholar

Silberman, Matthew (2001) Resource mobilization and the reduction of prison violence, S. 313–334 in R. K. Schutt & S. W. Hartwell (Eds.), The organizational response to social problems. Amsterdam, New York: JAI Press.10.1016/S0196-1152(01)80015-6Search in Google Scholar

Skar, Mette, Lokdam, Nicoline, Liebling, Alison, Muriqi, Alban, Haliti, Ditor, Rushiti, Feride & Modvig, Jens (2019) Quality of prison life, violence and mental health in Dubrava prison. International journal of prisoner health 15: 262–272.10.1108/IJPH-10-2017-0047Search in Google Scholar

Snacken, Sonja (2005) Forms of violence and regimes in prison: report of research in Belgian prisons, S. 306–340 in A. Liebling & S. Maruna (Eds.), The Effects of Imprisonment. London: Willan.Search in Google Scholar

Sparks, Richard & Bottoms, Anthony E. (2008) Legitimacy and imprisonment revisited: Some notes on the problem of order ten years after, S. 91–104 in J. M. Byrne, D. C. Hummer & F. S. Taxman (Eds.), The Culture of Prison Violence. Boston: Pearson/Allyn and Bacon.Search in Google Scholar

Sparks, Richard, Bottoms, Anthony E. & Hay, Will (1996) Prisons and the problem of order. Oxford: Clarendon.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198258186.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Steiner, Benjamin & Wooldredge, John (2020) Understanding and Reducing Prison Violence. An Integrated Social Contral-Opportunity Perspective. Understanding and Reducing Prison Violence.10.4324/9781315148243Search in Google Scholar

Straus, Murray A., Hamby, Sherry L., Boney-McCoy, Sue & Sugarman, David B. (1996) The revised conflict tactics scales (CTS2) development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues 17: 283–316.10.1177/019251396017003001Search in Google Scholar

Sykes, Graham (2007 [1958]) The Society of Captives: A Study of a Maximus Security Prison. Princeton University Press.10.1515/9781400828272Search in Google Scholar

Toman, Elisa L. (2019) The Victim–Offender Overlap Behind Bars: Linking Prison Misconduct and Victimization. Justice Quarterly 36: 350–382.10.1080/07418825.2017.1402072Search in Google Scholar

Trubek, David M., Grossman, Joel B., Felstiner, William L. F., Kritzer, Herbert M. & Sarat, Austin (1983) Civil Litigation Research Project: Final Report. Madison, Wisconsin.Search in Google Scholar

van der Valk, Sophie, Aizpurua, Eva & Rogan, Mary (2022) “[Y]ou are better off talking to a f****** wall”: The perceptions and experiences of grievance procedures among incarcerated people in Ireland. Law & Society Review 56: 261–285.10.1111/lasr.12603Search in Google Scholar

van der Valk, Sophie & Rogan, Mary (2023) Complaining in Prison: ‘I suppose it’s a good idea but is there any point in it?’. Prison Service Journal: 3–10.Search in Google Scholar

van Ginneken, Esther F. J. C. & Wooldredge, John (2024) Offending and victimization in prisons: New theoretical and empirical approaches. International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice 77: 100667.10.1016/j.ijlcj.2024.100667Search in Google Scholar

van Velthoven, Ben C. J. & Voert, Marijke ter (2005) Legal Aid in the Wider Government Context: Needs Assessment and the Impact of Legal Aid, S. 231–254 in B. C. J. van Velthoven & M. J. ter Voert (Eds.), Paths to Justice in the Netherlands: Conference Reports And Papers. Killarney.Search in Google Scholar

Vanhala, Lisa (2012) Legal Opportunity Structures and the Paradox of Legal Mobilization by the Environmental Movement in the UK. Law & Society Review 46: 523–556.10.1111/j.1540-5893.2012.00505.xSearch in Google Scholar

Witzel, Andreas (2000) Das problemzentrierte Interview. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung Qualitative Social Research 1.Search in Google Scholar

World Justice Project (2019) Measuring the Justice Gap: A People-Centered Assessment of Unmet Justice Needs Around the World. Online: https://worldjusticeproject.org/sites/default/files/documents/WJP_Measuring%20the%20Justice%20Gap_final_20Jun2019_0.pdf, Accessed 11/29/2023.Search in Google Scholar

Wortley, Richard K. (2002) Situational prison control: Crime prevention in correctional institutions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511489365Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Dieses Werk ist lizenziert unter der Creative Commons Namensnennung - Nicht kommerziell - Keine Bearbeitung 4.0 International Lizenz.

Articles in the same Issue

- Titelseiten

- Wege zur Solidarität – Konzeptionelle Wurzeln des modernen Sozialstaats in Frankreich und Deutschland

- Dokumentationen

- Die konzeptionellen Wurzeln des Sozialstaates in Frankreich und in Deutschland

- Solidarität als verfassungsrechtliches Argument

- Zur Bedeutung des vertraglichen Solidarismus in Frankreich

- Abhandlungen

- Legal mobilisation in detention – the case of victims of violence in Austrian prisons

- Sozialrecht zwischen Parlament, Straße und Gericht

- Rezensionen

- Eugen Ehrlich. Kontexte und Rezeptionen, herausgegeben von Marietta Auer und Ralf Seinecke, Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck 2024, 575 Seiten, ISBN 978-3-16-162173-4, € 49,-

- Leo Merlin Eichele – Wo steht dem Recht der Kopf? Zur radikalen Demokratietheorie des Rechts, Weilerswist, Velbrück, 2025, 416 Seiten, ISBN 978-3-95832-395-7, 44,90€.

Articles in the same Issue

- Titelseiten

- Wege zur Solidarität – Konzeptionelle Wurzeln des modernen Sozialstaats in Frankreich und Deutschland

- Dokumentationen

- Die konzeptionellen Wurzeln des Sozialstaates in Frankreich und in Deutschland

- Solidarität als verfassungsrechtliches Argument

- Zur Bedeutung des vertraglichen Solidarismus in Frankreich

- Abhandlungen

- Legal mobilisation in detention – the case of victims of violence in Austrian prisons

- Sozialrecht zwischen Parlament, Straße und Gericht

- Rezensionen

- Eugen Ehrlich. Kontexte und Rezeptionen, herausgegeben von Marietta Auer und Ralf Seinecke, Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck 2024, 575 Seiten, ISBN 978-3-16-162173-4, € 49,-

- Leo Merlin Eichele – Wo steht dem Recht der Kopf? Zur radikalen Demokratietheorie des Rechts, Weilerswist, Velbrück, 2025, 416 Seiten, ISBN 978-3-95832-395-7, 44,90€.