Abstract

Taking Miyagawa’s (2022. Syntax in the treetops. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press) discussion as a point of departure, I examine the properties of the formal politeness markers in Japanese and Korean, namely, -mas/-des and -(su)pni. Besides being markers of formal politeness (or allocutive agreement), these elements are parallel in that they are all limited to Emonds’ (1970. Root and structure-preserving transformations. Ph.D. dissertation, MIT) root contexts and are able to license special interrogative particles, which according to Miyagawa (2022. Syntax in the treetops. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press) is a consequence of their head-to-head φ-feature movement. In addition to the systematic similarities, there is an important difference concerning their base-generation in TP-internal and TP-external positions, which I suggest reflects a general pattern of grammaticalization in these languages. In addition to providing support for Miyagawa’s analysis, the discussion in this paper also shows that aspects of the behavior of Japanese and Korean, such as the formal politeness markers -mas/-des and -(su)pni, can generally be better understood when they are analyzed side-by-side rather than in isolation.

1 Introduction

Several researchers discuss phenomena where the form of agreement encodes some aspects of the relation between speaker and addressee such as levels of politeness and/or formality. In the literature, this phenomenon is called allocutive agreement (Alok 2020; Antonov 2015; Ceong and Saxon 2020; Kaur and Yamada 2022; Miyagawa 2012; Miyagawa 2017; Miyagawa 2022; Oyharçabal 1993; Portner et al. 2019; Portner et al. 2022; Yamada 2019 among others). In his recent work, Miyagawa (2022) examines the properties of the formal politeness markers -mas and -des in Japanese, as illustrated in (1) and (2), arguing that these elements instantiate allocutive agreement.

| Hanako-wa | piza-o | tabe-ru. |

| H.-top | pizza-acc | eat-prs [1] |

| ‘Hanako will eat pizza.’ (colloquial) | ||

| Hanako-wa | piza-o | tabe-mas-u. |

| H.-top | pizza-acc | eat-mas-prs |

| ‘Hanako will eat pizza.’ (formal) | ||

| (Miyagawa 2022: 39) | ||

| Hanako-wa | sensee-da. |

| H.-top | teacher-cop |

| ‘Hanako is a teacher.’ (colloquial) | |

| Hanako-wa | sensee-des-u. |

| H.-top | teacher-des-prs |

| ‘Hanako is a teacher.’ (formal) | |

| (Miyagawa 2022: 64) | |

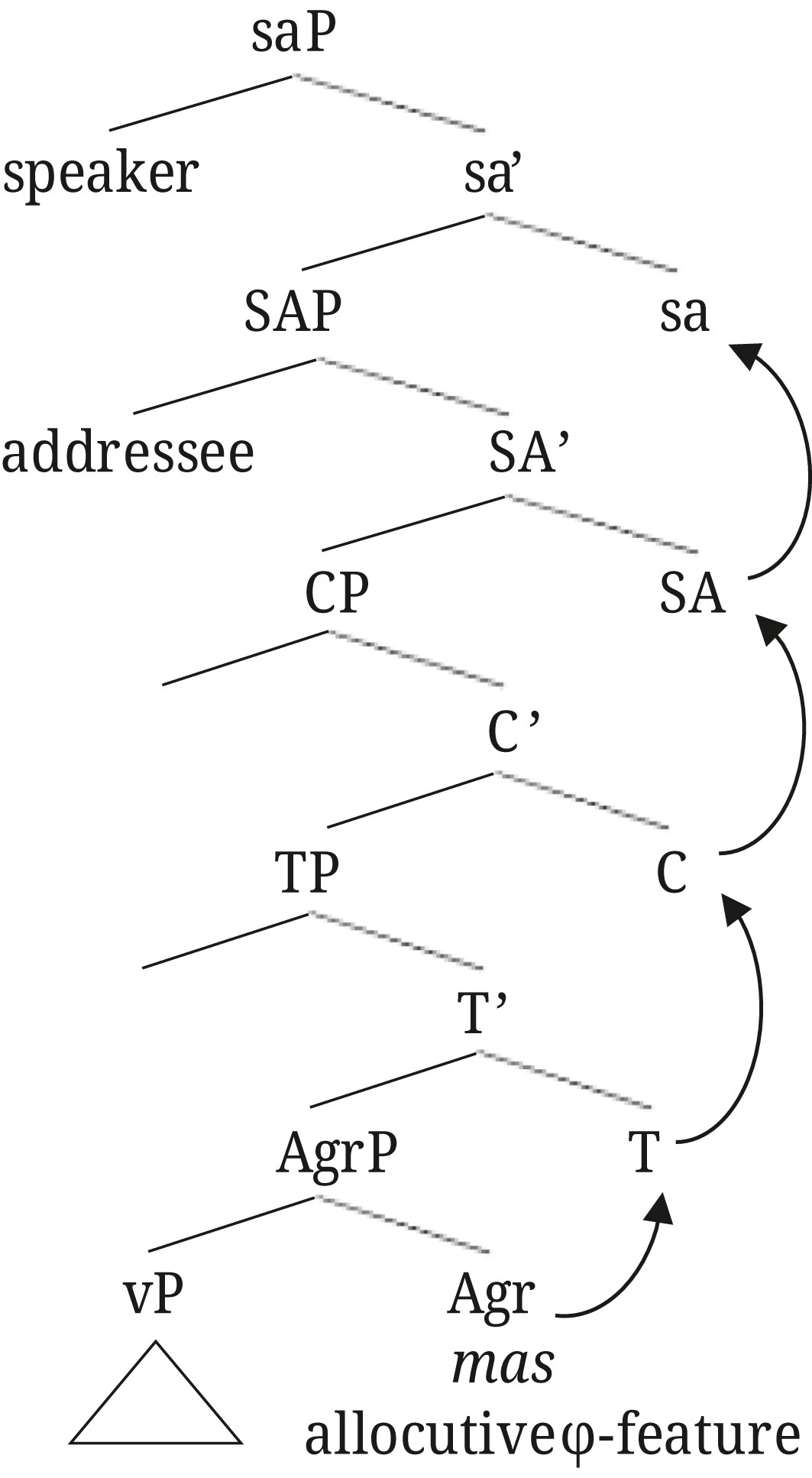

Miyagawa argues that the allocutive φ-feature of -mas and -des has to undergo head-to-head feature movement to a special functional projection at the top of the clause, namely, the SAP,[2] to have the entire utterance in its scope and mark it as being in the formal registry. More specifically, the allocutive φ-feature of -mas and -des is assumed to move up to the sa head, where it c-commands the addressee element and have its φ-feature valued.

|

As evidence for the head-to-head feature movement, Miyagawa points out that certain heads are only licensed in the presence of -mas or -des. For instance, the occurrence of the interrogative particle ka depends on the occurrence of -mas and -des, as shown in (4) and (5).

| Dare-ga | ki-mas-u | ka? |

| who-nom | come-mas-prs | q |

| ‘Who will come?’ | ||

| *Dare-ga | kuru | ka? |

| who-nom | come | q |

| ‘Who will come?’ | ||

| (Miyagawa 2022: 41) | ||

| Dare-ga | sensee-des-u | ka? |

| who-nom | teacher-des-prs | q |

| ‘Who is a teacher?’ | ||

| *Dare-ga | sensee-da | ka? |

| who-nom | teacher-cop | q |

| ‘Who is a teacher?’ | ||

| (Miyagawa 2022: 41) | ||

Similarly, in (6a), negation takes the form -en unlike the regular form in (6b). In fact, this is the only environment in which negation is realized as -en, i.e., the form -en only shows up in the presence of the formal politeness marker -mas.

| Hanako-wa | piza-o | tabe-mas-en. |

| Hanako-top | pizza-acc | eat-mas-neg |

| ‘Hanako will not eat formal pizza.’ | ||

| Taroo-wa | piza-o | tabe-na-i. |

| Taro-top | pizza-acc | eat-neg-prs |

| ‘Taro doesn’t eat pizza.’ | ||

| (Miyagawa 2022: 52–53) | ||

Furthermore, once -mas is inserted, all relevant heads must undergo allomorphy for politeness.

| Nimotu-wa | todoki-mas-en-desita/*datta | desyoo/*daroo | ka? |

| package-top | arrive-mas-neg-cop.pst | interjection | q |

| ‘Didn’t the package arrive?’ | |||

Miyagawa argues that the properties in (4)-(7) are all due to the fact that the allocutive φ-feature of -mas and -des moves up through all head positions on its way to the SAP, licensing the relevant elements.

Against this background, I examine in this paper the Korean counterparts of -mas and -des – namely, -supnita and -ipnita, shown in (8).

| Hana-nun | phica-lul | mek-ess-supnita. | (Cf. (1b)) |

| H.-top | pizza-acc | eat-pst-supnita | |

| ‘Hana ate pizza.’ (formal) | |||

| Hana-nun | sensayngnim-ipnita. | (Cf. (2b)) |

| H.-top | teacher-ipnita | |

| ‘Hanako is a teacher.’ (formal) | ||

Similarly to -mas and -des, -supnita and -ipnita are markers of formal politeness. They are normally inappropriate when speaking to one’s own child or close friend. I show below that there are several aspects where the behavior of -supnita and -ipnita can be better understood when they are analyzed in comparison with -mas and -des than when they are examined in isolation. Of course, the same goes for -mas and -des, i.e., some aspects of Miyagawa’s analysis of -mas and -des receive further support from the behavior of -supnita and -ipnita. I also point out a potentially general parametric difference in grammaticalization in Japanese and Korean that can only be revealed when these languages are examined together. The discussion in this paper clearly illustrates the merits of conducting comparative research on Japanese and Korean, languages that often show systematic similarities and differences, providing an ideal ground for uncovering deeper properties of human language.

2 Basic properties of the formal politeness markers in Korean

As is well-known, Korean is an agglutinative language. Many suffixes, usually assumed to be independent functional heads, attach to the verb stem. In Korean grammar, these verbal suffixes are referred to as emi ‘word ending’, often translated simply as “ending”. The verb stem (or root) in Korean is always morphologically dependent and can never be used in isolation without an appropriate ending. In particular, Kang (1988) introduces the notion of morphological closure, meaning that a verb stem has to combine with an appropriate ending to close it off to be a well-formed independent word. For instance, in (9), several endings are attached to the verb stem o- ‘come’. Among the endings, the last element, i.e., the declarative clause type marker -ta, is classified as a “word-final ending” in Korean grammar literally because of its position within the word. Here, -ta also functions as a “morphological closer”. Basically, any element that is used as a word-final ending on a verb also functions as a morphological closer. Other elements that come between the verb stem and the word-final ending, such as the honorification marker -si and the past tense marker -ess in (9), are classified as “pre-final endings”. From a morphological point of view, the word-final ending is the only obligatory element among all the endings that can attach to a verb stem.

| Sensayngnim-kkeyse | o-(si)-(ess)-*(ta). |

| teacher-nom.hon | come-hon-pst-dec |

| ‘The teacher has arrived.’ | |

With this basic knowledge of Korean verbal morphology and the terminology for it, let us look into the basic properties of the formal politeness endings -supnita and -ipnita below.

2.1 -Supnita

As mentioned above, -supnita is a formal politeness ending in Korean, corresponding to -mas in Japanese. Thus, an utterance like (10b) is used in formal and polite situations. Normally, speakers would not utter (10b) to their own children or close friends, while (10a) is perfectly fine in those situations.

| Hana-nun | phica-lul | mek-ess-ta. | (Cf. (1)) |

| H.-top | pizza-acc | eat-pst-dec | |

| ‘Hana ate pizza.’ (colloquial) | |||

| Hana-nun | phica-lul | mek-ess-supnita. |

| H.-top | pizza-acc | eat-pst-for.dec |

| ‘Hana ate pizza.’ (formal) | ||

In the literature, researchers often treat -supnita as a monomorphemic portmanteau element, assuming that it indicates the formal polite speech style as well as the declarative clause type at the same time (Brown 2015; Hong 2022; Park 2019; Portner et al. 2019, 2022, among others). I suspect that might be because the internal structure of this element happens not to be crucial for their discussion at hand. But, -supnita actually consists of two elements, i.e., the pre-final ending -supni and the word-final ending -ta (see also Ceong and Saxon 2020 for arguments to this effect).[3] Thus, the internal structure of the verb in (10b) should be more precisely represented as in (11). (Henceforth, I gloss -supni and related elements as ssp ‘speech style particle’.)

| mek-ess-supni-ta |

| eat-pst-ssp-dec |

Here, the word-final ending -ta is used productively as a declarative clause type marker, as already shown in (9) and (10a). As expected, in an interrogative sentence, a different clause type marker, namely, -kka, attaches to -supni, which supports the decomposition.

| Hana-nun | phica-lul | mek-ess-supni-kka? |

| H.-top | pizza-acc | eat-pst-ssp-q |

| ‘Did Hana eat pizza?’ (formal) | ||

Crucially, this shows that the formal polite speech style interpretation stems from the pre-final ending -supni alone. The word-final endings -ta and -kka simply indicate the type of the clause. Furthermore, -supni has to follow the tense marker, which indicates that it is higher than TP, i.e., -supni is TP-external. Note however that -supni has to precede the clause type markers. The clause type markers are usually assumed to be located high in the structure, i.e., in the periphery of the CP domain as the head of ForceP or MoodP. Given that -supni comes before the clause type markers, it should be lower than the projection that hosts the clause type markers, whatever the label, and definitely below the SAP, which is at the top of the structure. Thus, from the point of view of Miyagawa (2022), -supni is actually not high enough, though it is higher than -mas.[4] (See Section 4 for further discussion).

Another thing to note about -supni is that it alternates with its allomorph -pni depending on its phonological environment. The former shows up when the immediately preceding element ends with a consonant, while the latter shows up when the preceding element ends with a vowel. For instance, in (13a), the formal politeness marker attaches to the verb stem which ends with a vowel. Therefore, it is realized as -pni. In (13b), even though the verb stem remains constant, the formal politeness marker is realized as -supni because what immediately precedes it is the past tense marker that ends with a consonant. In (13c), there is no past tense marker, but the verb stem ends with a consonant, so that the formal politeness marker is realized as -supni again.

| Hana-nun | hakkyo-ey | ka-pni-ta.[5] |

| H.-top | school-to | go-ssp-dec |

| ‘Hana goes to school.’ | ||

| Hana-nun | hakkyo-ey | ka-ss-supni-ta. |

| H.-top | school-to | go-pst-ssp-dec |

| ‘Hana went to school.’ | ||

| Salam-i | cwuk-supni-ta. |

| person-nom | die-ssp-dec |

| ‘A person dies.’ | |

Given that -supni occurs after a consonant in present tense and in all cases of past tense utterances (as the past tense marker always ends with a consonant), it is reasonable to assume that -supni has a wider distribution than -pni. Therefore, I assume that -supni is the unmarked form.

2.2 -Ipnita

Korean also has a formal polite form for utterances involving the copula, an environment where -des in Japanese occurs. The form used in such situations is -ipnita, as shown in (14).

| Hana-nun | sensayngnim-ipnita. | (= (2b)) |

| H.-top | teacher-for.dec | |

| ‘Hanako is a teacher.’ | ||

Note however that unlike -des, the form -ipnita can be decomposed into smaller parts. That is, it contains the copula -i, the formal politeness marker -pni,[6] discussed in the previous section, and the declarative clause type marker -ta, as shown in (15).

| Hana-nun | sensayngnim-i-pni-ta. |

| H.-top | teacher-cop-ssp-dec |

| ‘Hana is a teacher.’ | |

Similarly to -(su)pni, it can also be used with the interrogative clause type marker -kka, as shown in (16).

| Hana-nun | sensayngnim-i-pni-kka? |

| H.-top | teacher-cop-ssp-q |

| ‘Is Hana a teacher?’ | |

In non-formal situations, -pni of course does not show up, so that only the copula and the clause type marker are used, as shown in (17). The fact that -pni can be separated from these elements provides support for the decomposition of -ipnita as suggested above.

| Hana-nun | sensayngnim-i-ta. | (cf. (2a)) |

| H.-top | teacher-cop-dec | |

| ‘Hana is a teacher.’ | ||

Note further that in situations like (17), the past tense marker -ess can be inserted between the copula and the clause type marker, as in (18a). Now, when the utterance in (18a) becomes formal, the formal politeness ending will be inserted. However, unlike in (15), its form should be -supni, not -pni, as shown in (18b). This is because the element immediately preceding the formal politeness ending, i.e., the past tense marker -ess, ends with a consonant.

| Hana-nun | sensayngnim-i-ess-ta. |

| H.-top | teacher-cop-pst-dec |

| ‘Hana was a teacher.’ | |

| Hana-nun | sensayngnim-i-ess-supni-ta. |

| H.-top | teacher-cop-pst-ssp-dec |

| ‘Hana was a teacher.’ (formal) | |

In conclusion, unlike the initial impression, -ipnita does not directly correspond to -des. In the surface form -ipnita, only -i is the copula, and this element has nothing to do with expressing politeness. The remaining elements, i.e., -pni and -ta, are productively used as the formal politeness marker and the declarative clause type marker, respectively. The crucial point from this observation is that Korean has just one element for marking formal politeness, namely, the pre-final ending -(su)pni.

| Unlike Japanese, Korean has only one marker of formal polite speech style, namely, -(su)pni. |

Therefore, in both regular verb sentences and copula sentences, -(su)pni is used for marking formal politeness. In this respect, Korean differs from Japanese, which uses at least two different elements for marking formal politeness, i.e., -mas and -des.

3 The interrogative clause type marker -kka

Recall that according to Miyagawa (2022), all the relevant heads on the path of the φ-features of -mas and -des undergo allomorphy to be in polite form. In particular, Miyagawa argues that the φ-features of -mas and -des can license the interrogative particle -ka. He argues these phenomena to provide support for the head-to-head feature movement analysis. In Korean, there is no comparable allomorphy phenomena. Thus, even if we follow Miyagawa and assume that the formal politeness marker should have the entire utterance in its domain by undergoing head-to-head feature movement to the SAP at the top of the structure, it is difficult to show it directly. Still, as shown in (12), repeated here as (20), Korean has an interrogative clause type marker, namely, -kka, that is used in sentences involving -(su)pni, similarly to -ka in Japanese.

| Hana-nun | phica-lul | mek-ess-supni-kka? |

| H.-top | pizza-acc | eat-pst-ssp-q |

| ‘Did Hana eat pizza?’ | ||

A formal question involving the copula also licenses -kka arguably due to the presence of -(su)pni, as shown in (16), repeated here as (21).

| Hana-nun | sensayngnim-i-pni-kka? |

| H.-top | teacher-cop-ssp-q |

| ‘Is Hana a teacher?’ | |

Furthermore, an interrogative sentence involving -kka becomes ungrammatical if -(su)pni is omitted, confirming that the former depends on the latter for its licensing.

| *Hana-nun | phica-lul | mek-ess-kka? | (cf. (20)) |

| H.-top | pizza-acc | eat-pst-q | |

| ‘Did Hana eat pizza?’ | |||

| *Hana-nun | sensayngnim-i-kka? | (cf. (21)) |

| H.-top | teacher-cop-q | |

| ‘Is Hana a teacher?’ | ||

Of course, in such contexts, i.e., without -(su)pni, other interrogative endings than -kka can be used, as shown below.[7]

| Hana-nun | phica-lul | mek-ess-ni/-nya/-eyo? |

| H.-top | pizza-acc | eat-pst-q |

| ‘Did Hana eat pizza?’ | ||

| Hana-nun | sensayngnim-i-ni/-nya/-eyo? |

| H.-top | teacher-cop-q |

| ‘Is Hana a teacher?’ | |

However, in the presence of -(su)pni, the interrogative ending must be -kka.

| *Hana-nun | phica-lul | mek-ess-supni-ni/-nya/-eyo? | (cf. (20)) |

| H.-top | pizza-acc | eat-pst-ssp-q | |

| ‘Did Hana eat pizza?’ | |||

Given this, it is clear that there is a dependency between the interrogative ending -kka and the formal politeness marker -(su)pni.[8] Recall that Miyagawa argues that ka can be licensed by -mas/-des in the course of their feature movement to the SAP (or via selection by some particular type of verb in the main clause). This may be extended to Korean to the effect that -kka is licensed by -(su)pni in the course of its feature movement. Note incidentally that -kka can also be licensed in the presence of a modal, as shown in note 8. Given that the modal precedes -kka, just like -(su)pni, it may be necessary to assume that the modal undergoes feature movement, though where and why it moves require further investigation. Alternatively, it may be that -kka selects for the projection of -(su)pni and that of a modal. If this is the case, there may be a slight difference between Korean and Japanese regarding the licensing of the interrogative endings. For the moment, I remain open between these possibilities. Note however that whichever option is taken, head-to-head feature movement of -(su)pni to the SAP is independently motivated.

4 The positions of -mas, -Des, and -(Su)pni

Recall that one important assumption that Miyagawa adopts regarding the position of -mas and -des is that these elements should have the entire utterance in their scope at some point in the derivation. With that in mind, I turn in this section to the structural positions of the formal politeness markers in Japanese and Korean and show that there are interesting similarities and differences among them.

4.1 TP-internal position of -Mas and -Des1

Note that both -mas and -des are below tense and above the main predicate, as the data in (25) and (26) show.

| Hanako-wa | piza-o | tabe-mas-u. |

| H.-top | pizza-acc | eat-mas-prs |

| ‘Hanako will eat pizza.’ | ||

| (Miyagawa 2022: 39) | ||

| Peter-wa | hataraki-mas-ita. |

| P.-top | work-mas-pst |

| ‘Peter worked.’ | |

| (Miyagawa 2012: 86) | |

| Hanako-wa | sensee-des-u. |

| H.-top | teacher-des-prs |

| ‘Hanako is a teacher.’ | |

| (Miyagawa 2022: 64) | |

| Hanako-wa | sensee-des-ita. |

| H.-top | teacher-des-pst |

| ‘Hanako was a teacher.’ | |

Miyagawa (2022) argues that these elements are inserted in an agreement projection between vP and TP and that only their allocutive φ-feature undergoes head-to-head movement to the SAP, as discussed above.

Given this, recall that various suffixal elements (or endings) can be attached to the verb stem in Korean.

| Sensayngnim-kkeyse | o-si-ess-supni-ta. |

| teacher-nom.hon | come-hon-pst-ssp-dec |

| ‘The teacher has arrived.’ | |

Note that the subject honorification marker -si occurs between the verb stem o- and the tense marker -ess, which is very similar to the position that -mas and -des occupy. It is also noteworthy that many researchers argue that subject honorification in Korean involves φ-feature agreement (Chung 2009; Choi 2010; Choi and Harley 2019; Kim 2012; but see also Choe 2004; Kim and Sells 2007). Furthermore, these elements are similar in that they all express politeness in some way. Given this, I propose that -mas, -des, and -si all occur in an agreement projection between vP and TP.

It should be pointed out however that there is one crucial difference between -mas, -des, and -si. That is, while the φ-feature agreement relation involving -si makes reference to the subject of the clause, the φ-feature agreement relation involving -mas/-des makes reference to the addressee element in the SAP.[9] This actually leads to another important difference between these elements, to which I return in Section 5.

4.2 TP-external position of -Des2 and -Supni

In all the examples involving -des so far, e.g., (26), -des is used with a noun as the copula. Miyagawa (2022) points out that there is another type of -des that is used with adjectives, as shown in (28). (For ease of exposition, I will refer to the first type of -des as “-des1” and the second type of -des as “-des2”).

| Ano | piza-wa | taka-i | desu.[10] |

| that | pizza-top | expensive-prs | des2 |

| ‘That pizza is expensive.’ | |||

| Ano | piza-wa | taka-katta | desu. |

| that | pizza-top | expensive-pst | des2 |

| ‘That pizza was expensive.’ | |||

| (Miyagawa 2022: 65) | |||

Note, crucially, that -des2 follows tense and never inflects for tense itself, as shown below. (See also (28)).

| *Ano | piza-wa | taka-(i) | desita. |

| that | pizza-top | expensive-prs | des2.pst |

| ‘That pizza was expensive.’ | |||

| (Miyagawa 2022: 66) | |||

It is also noteworthy that -des2 can license -ka just like -mas and -des1.

| Ano | piza-wa | taka-i | desu | ka? |

| that | pizza-top | expensive-prs | des2 | q |

| ‘Was that pizza expensive?’ | ||||

| (Miyagawa 2022: 66) | ||||

| Ano | piza-wa | taka-katta | desu | ka? |

| that | pizza-top | expensive-pst | des2 | q |

| ‘Was that pizza expensive?’ | ||||

Given this, Miyagawa argues that -des2 is inserted in a position higher than TP unlike -mas and -des1 and that it also undergoes the same kind of head-to-head feature movement to the SAP, licensing ka in the course of the movement.

Now, let us turn to -(su)pni. In (11) and (18b), repeated below as (31a) and (31b), it is shown that in both regular verb and copula sentences, -(su)pni occurs above the tense marker and below the clause type marker.[11] While there is some disagreement in the literature regarding the precise category label for the clause type markers, e.g., Force0, Mood0, C0, etc., it is clear that they are in the highest position in the CP domain below the SAP, considering that they are always the last element in the sequence of functional heads (or endings) that attach to the verb stem.

| Hana-nun | phica-lul | mek-ess-supni-ta. |

| H.-top | pizza-acc | eat-pst-ssp-dec |

| ‘Hana ate pizza.’ | ||

| Hana-nun | sensayngnim-i-ess-supni-ta. |

| H.-top | teacher-cop-pst-ssp-dec |

| ‘Hana was a teacher.’ | |

It is also worth pointing out that -(su)pni occurs above the modal of volition, possibility, or prediction, namely, -keyss, which in turn occurs above tense.

| Ce-nun | phica-lul | mek-kyess-supni-ta. |

| I.pol-top | pizza-acc | eat-mod-ssp-dec |

| ‘I will eat pizza.’ | ||

| Ce-ka | phica-lul | mek-ess-keyss-supni-kka? |

| I.pol-nom | pizza-acc | eat-pst-mod-ssp-q |

| ‘Would I have eaten pizza?’ | ||

Even when it is used with an adjective, the position of -(su)pni remains the same as in regular verb and copula sentences, i.e., it is above tense and modal and below the clause type marker. This again confirms that Korean just has one formal politeness marker, i.e., -(su)pni.[12]

| I | cha-nun | pissa-pni-ta. |

| this | car-top | expensive-ssp-dec |

| ‘This car is expensive.’ | ||

| I | cha-nun | pissa-ss-supni-ta. |

| this | car-top | expensive-pst-ssp-dec |

| ‘This car was expensive.’ | ||

| I | cha-nun | pissa-keyss-supni-ta. |

| this | car-top | expensive-mod-ssp-dec |

| ‘This car may be expensive.’ | ||

| I | cha-nun | pissa-ess-keyss-supni-ta. |

| this | car-top | expensive-pst-mod-ssp-dec |

| ‘This car may have been expensive.’ | ||

As pointed out above, -(su)pni is not itself in the highest position in CP unlike what its usual treatment as a portmanteau morpheme would suggest. However, this element is still fairly high in the structure, i.e., it is TP-external, unlike -mas and -des1. In this respect, -(su)pni appears to be similar to -des2. Concerning the position of -des2, Miyagawa (2022: 66) assumes, following Koizumi (1991, 1993, that it occurs in a modal phrase (ModP) above TP. However, given that -(su)pni can occur even above a modal, it is not clear if we can extend Miyagawa/Koizumi’s assumption to -(su)pni at face value. It is also worth mentioning that in An (2022), it is argued that the evidentiality marker po- in Korean is a TP-external functional category located in MoodPevidential in Cinque’s (2004) cartographic hierarchy. In particular, An points out that po- occurs higher than the modal -keyss, as (34) shows.

| Koki-nun | mos | mek-kyess-na | po-(*keyss)-ta. |

| meat-top | cannot | eat-mod-epst | evid-mod-dec |

| ‘It seems that (he) cannot eat meat.’ | |||

| (An 2022: 787) | |||

Interestingly, as (35) shows, -(su)pni occurs even higher than evidential po-. This further indicates that -(su)pni is higher than ModP.

| Hana-ka | wa-ss-na | po-pni-ta. |

| H.-nom | come-pst-epst | evid-ssp-dec |

| ‘It seems that Hana has arrived.’ | ||

Givent this, it is clear that the position of -(su)pni is higher than TP and ModP at least. If -des2 is equivalent to -(su)pni, then it might not be located in ModP either, though further investigation on the Japanese facts is necessary at this point to verify it.[13]

5 The distribution of the formal politeness markers and their root sensitivity

Several researchers note that the distribution of -(su)pni (as well as several other speech style particles in Korean) is limited to root clauses, i.e., they cannot be embedded (Hong 2018, 2022; Park 2019; Portner et al. 2019, 2022). Their analyses converge on the idea that the unembeddability of the speech style particles stems from the fact that they have to be in a local relation with the SAP, which is assumed to occur at the top of the utterance, i.e., at the root only.

| *Inho-ka | [ecey | pi-ka | o-ass-supni-ta-ko] | malha-ss-supni-ta. |

| I.-nom | yesterday | rain-nom | come-pst-ssp-dec-comp | say-pst-ssp-dec [14] |

| ‘Inho said that it rained yesterday.’ | ||||

| (Portner, Pak, and Zanuttini 2019: 3) | ||||

In this respect, -mas is not different, i.e., it cannot occur in a complement clause.

| *Hanako-wa | [minna | ki-mas-u | to] | omott-ta. |

| H.-top | everyone | come-mas-prs | comp | think-pst |

| ‘Hanako thought that everyone will come.’ | ||||

| (Miyagawa 2022: 58) | ||||

However, Miyagawa (2022) points out that the distribution of -mas is not entirely limited to main clauses either. This is illustrated by the availability of sentences like (38b) and (38c).

| Highest S | |

| Hanako-wa | ki-mas-u. |

| H.-top | come-mas-prs |

| ‘Hanako will come.’ | |

| S dominated by highest S | ||||

| Hanako-ga | ki-mas-u | kara, | ie-ni | ike-kudasai. |

| H.-nom | come-mas-prs | because | home-at | be-please |

| ‘Because Hanako will come, please be at home.’ | ||||

| Reported S in direct discourse | ||||

| Taroo-wa | Hanako-ga | ki-mas-u | to | itta. |

| T.-top | H.-nom | come-mas-prs | comp | said |

| ‘Taro said that Hanako will come.’ | ||||

| (Miyagawa 2022: 48) | ||||

Miyagawa points out that the contexts in (38) correspond to what Emonds (1970) defines as the root in (39).

| Root |

| A root will mean either the highest S in a tree, an S immediately dominated by the highest S, or the reported S in direct discourse. |

| (Emonds 1970: 6) |

Interestingly, Park (2019) also notes that the distribution of -(su)pni fits into Emonds’ definition of the root, as shown in (40).[15] Note in particular that (40b) and (40c) show that -(su)pni can in fact occur in some non-root environments.

| Highest S | |||

| Sensayngnim, | Cheli-ka | hakkyo-ey | ka-ss-supni-ta. |

| teacher.pol | C.-nom | school-to | go-pst-ssp-dec |

| ‘Sir, Chelswu went to school.’ | |||

| S dominated by highest S | |||

| Sensayngnim, | Cheli-ka | hakkyo-ey | ka-ss-supni-ta-manun, |

| teacher.pol | C.-nom | school-to | go-pst-ssp-dec-though |

| ku-eykey | mwela | cenha-l-kka-yo? | |

| he-dat | what | tell-mod-q-pol | |

| ‘Sir, though Chelswu went to school, what should I tell him?’ | |||

| Reported S in direct discourse | ||||

| Yengi-nun | Sensayngnim, | Cheli-ka | hakkyo-ey | ka-ss-supni-ta-lako |

| Y.-top | teacher.pol | C.-nom | school-to | go-pst-ssp-dec-comp |

| taytapha-ess-ta. | ||||

| answer-pst-dec | ||||

| ‘Yenghi answered, “Sir, Chelswu went to school”.’ | ||||

| (Park 2019: 31–32, n.3) | ||||

Finally, recall that I pointed out in Section 4.1 that the formal politeness markers -mas and -des1 in Japanese and the subject honorification marker -si in Korean are similar in that they are base-generated in an agreement projection between vP and TP and undergo φ-feature agreement with the relevant elements. But, one crucial difference is that the former elements need to establish a local relation with the addressee representation in the SAP in the root, which leads to their restricted distribution, while the latter only needs a local relation with the subject of the clause. As expected, -si is not confined to root environments, i.e., there is no problem for -si to be used in a complement clause, as shown in (41).

| Hana-nun | [sensayngnim-kkeyse | o-si-ess-(*supni)-ta-ko] |

| H.-top | teacher-nom.hon | come-hon-pst-ssp-dec-comp |

| malha-ess-ta. | ||

| say-pst-dec | ||

| ‘Hana said that the teacher has arrived.’ | ||

To summarize, the discussion in this section shows that the formal politeness markers in Japanese and Korean, namely, -mas, -des1, -des2, and -(su)pni, all behave in the same way in that they are restricted to Emonds’ root environments. According to Miyagawa (2022), Emonds’ root contexts are those environments that allow the occurrence of the SAP. Given that the formal politeness markers are required to establish a local relation with the addressee element in the SAP, their root sensitivity follows. This is where Japanese and Korean facts align perfectly. One point of difference though is that while -mas, -des1, and -si are all inserted in an agreement projection between vP and TP, -si is free to be embedded, as it does not depend on the SAP.[16]

6 Differences in grammaticalization

At the end of Section 4, I briefly mentioned An’s (2022) work where it is argued that the evidentiality marker po- in Korean is a TP-external functional category. Evidential po- basically means something like ‘seem’ in English. It indicates that the speaker has some reasons, if not direct evidence, to believe that the proposition of the clause is true. Usually, the speaker makes an observation about the situation and makes inferences based on it. For instance, (42) can be uttered when the speaker sees Hana’s car parked in front of her house, though the speaker did not actually see her arrive.

| Hana-ka | wa-ss-na | po-ta. |

| H.-nom | come-pst-epst | evid-dec |

| ‘It seems that Hana came.’ (or ‘I guess that Hana came.’) | ||

Japanese has a similar expression—namely, sooda, as discussed by An and Maeda (2023). Sooda has more than one uses, but in one use, it means something like ‘seem’ and indicates that the speaker has some reasons to believe the proposition to be true. That is, just like evidential po-, the speaker makes an inference based on his/her observation of the situation.

| Hanako-ga | ki-sooda. |

| Hanako-nom | come.inf-seem |

| ‘Hanako seems to come.’ | |

Evidential po- and sooda are also similar in that they are functional categories, as indicated by the fact that they are unable to introduce their own arguments.

| *Na-nun | Toto-ka | o-ass-na | po-ta. |

| I-top | T.-nom | arrive-pst-epst | evid-dec |

| *Toto-ka | o-ass-na | na-eykey | po-ta. |

| T.-nom | arrive-pst-epst | I-dat | evid-dec |

| *Toto-ka | o-ass-na | na-lul | po-ta. |

| T.-nom | arrive-pst-epst | I-acc | evid-dec |

| (An 2022: 781) | |||

| *Boku-wa/ga/ni | Ken-ga | tuki-soodat-ta. |

| I-top/nom/dat | K.-nom | arrive-seem-pst |

| ‘(Intended) To me, Ken seems to come.’ | ||

| (An and Maeda 2023) | ||

Interestingly, however, there is a clear difference in their structural positions. That is, evidential po- is above TP, as can be seen from the fact that the tense marker is attached to the main verb and shows up before po- in (42). Attaching the tense marker to evidential po- leads to ungrammaticality, regardless of whether the main verb tensed or not, as shown in (46). Note further that the impossibility of tense-marking po- also indicates that it is not the matrix verb in a biclausal structure unlike seem.

| *Hana-ka | wa-(ss)-na | po-ass-ta. |

| H.-nom | come-pst-epst | evid-pst-dec |

| ‘It seems that Hana has arrived.’ | ||

Being TP-external, it is also impossible for evidential po- to occur below negation.

| Hana-ka | o-ci | ahn-ass-na | po-ta. |

| H.-nom | come-nml | not-pst-epst | evid-dec |

| ‘It seems that Hana didn’t come.’ | |||

| *Hana-ka | wa-ss-na | po-ci | ahn-ta. |

| H.-nom | come-pst-epst | evid-nml | not-dec |

| ‘It doesn’t seem that Hana came.’ | |||

In contrast, sooda can be tense-marked, based on which An and Maeda (2023) argue that it is below T and is thus TP-internal.

| Hanako-ga | ki-sooda. |

| Hanako-nom | come.inf-seem.prs |

| ‘Hanako seems to come.’ | |

| Hanako-ga | ki-soodat-ta. |

| Hanako-nom | come.inf-seem-pst |

| ‘Hanako seemed to come.’ | |

Furthermore, sooda can occur below negation, which is consistent with the proposal that it is TP-internal.

| Ame-ga | huri-sooni-mo-nakat-ta. |

| rain-nom | fall.inf-seem-also-not-pst |

| ‘It didn’t seem to rain.’ | |

The interesting observation here is that evidential po- and sooda have equivalent functions and meanings, while their structural realizations are different. That is, evidential po- is TP-external, while sooda is TP-internal. This looks quite similar to the situation of -(su)pni and -mas. That is, while -(su)pni and -mas have equivalent functions and meanings, the former is TP-external and the latter is TP-internal. In other words, in each pair, the Korean counterpart is realized in a higher position in the TP-external domain, while the Japanese counterpart is realized in a lower position in the TP-internal domain. Of course, this may simply be a coincidence and does not reveal anything significant. An alternative possibility is that there exists a systematic difference in the way certain linguistic functions are grammaticalized in Japanese and Korean. That is, while the relevant elements are realized as high functional categories in Korean, their Japanese counterparts are realized in lower positions. If that is the case, it becomes necessary and also intriguing to see how pervasive and how systematic this parametric difference is between Japanese and Korean and perhaps, cross-linguistically and why such a difference exists, though that task has to await future research.

7 Conclusions

Taking as a point of departure Miyagawa’s (2022) recent discussion on the properties of the formal politeness marker (or the allocutive agreement marker) -mas and -des in Japanese, I have examined in this paper the properties of their Korean counterpart -(su)pni. I have shown that there are systematic differences and similarities between -mas/-des and -(su)pni. First, given that the their allocutive φ-features require valuation by the addressee element in the SAP, the distributions of -mas/-des and -(su)pni are perfectly identical. More specifically, both -mas/-des and -(su)pni are restricted to Emonds’ (1970) root contexts, which according to Miyagawa are environments that involve the SAP. Second, -mas/-des and -(su)pni are also similar in that certain elements, such as the special interrogative particles -ka and -kka, require their presence to be licensed, which according to Miyagawa (2022) is due to the head-to-head feature movement of -mas/-des (and -(su)pni). On the other hand, I have also shown that there is a crucial difference in the structural positions of -mas/-des and -(su)pni to the effect that -mas and -des1 are TP-internal and occupy the head position of an agreement projection that I argue also hosts the subject honorification marker -si in Korean, while -(su)pni occupies a position between TP and CP. Furthermore, I have pointed out that the difference in the structural height of -mas/-des and -(su)pni appears to be parallel to the difference in the structural height of evidential sooda and evidential po-, which may potentially be revealing the tendency where Japanese elements are realized in lower structural positions than their Korean counterparts. How general or pervasive this parametric difference is between the languages in question and cross-linguistically and also why such a pattern exists require further research. Finally, I should note that honorification and politeness markers in Japanese and Korean have been studied quite extensively by numerous researchers, which I cannot begin to do justice to in this short paper. Here, I have almost exclusively focused on Miyagawa’s analysis, but interested readers are referred to Portner et al. (2019, 2022), Yamada (2019), Hong (2022) for relevant discussion and references.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments. Special thanks are due to Akitaka Yamada for kindly providing a detailed explanation of some of the Japanese data. I also thank Harry van der Hulst for his generous support during the review process. Portions of the discussion in this paper were presented at the 17th Workshop on Altaic Formal Linguistics (Ulaanbaatar, September 2023) and the 16th Brussels Conference on Generative Linguistics (Brussels, October 2023). I thank the organizers and audiences at these events. This paper was supported by Konkuk University in 2023.

References

Alok, Deepak. 2020. Speaker and addressee in natural language: Honorificity, indexicality, and their interaction in Magahi. Ph.D. dissertation. The State University of New Jersey, Rutgers.Search in Google Scholar

Alok, Deepak. 2021. The morphosyntax of Magahi addressee agreement. Syntax 24(3). 263–296. https://doi.org/10.1111/synt.12213.Search in Google Scholar

An, Duk-Ho. 2022. A cartographic approach to the right periphery: The dual status of Italian sembrare and its Korean counterpart. Studia Linguistica 76(3). 772–790. https://doi.org/10.1111/stul.12195.Search in Google Scholar

An, Duk-Ho & Masako Maeda. 2023. A cartographic approach to evidential markers in Korean and Japanese. Presented at Workshop on Altaic Formal Linguistics 17, National University of Mongolia, Ulaanbaatar. September 28, 2023.Search in Google Scholar

Antonov, Anton. 2015. Verbal allocutivity in a crosslinguistic perspective. Linguistic Typology 19(1). 55–85. https://doi.org/10.1515/lingty-2015-0002.Search in Google Scholar

Boeckx, Cedric & Fumikazu Niinuma. 2004. Conditions on agreement in Japanese. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 22(3). 453–480.10.1023/B:NALA.0000027669.59667.c5Search in Google Scholar

Boeckx, Cedric. 2006. Honorification as agreement. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 24(2). 385–398. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-005-1825-2.Search in Google Scholar

Bobaljik, Jonathan & Kazuko Yatsushiro. 2006. Problems with honorification-as-agreement in Japanese: A reply to Boeckx & Niinuma. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 24(2). 355–384. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-005-1511-4.Search in Google Scholar

Brown, Lucien. 2015. Revisiting ‘‘polite’’ -yo and ‘‘deferential’’ -supnita speech style shifting in Korean from the viewpoint of indexicality. Journal of Pragmatics 79. 43–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2015.01.009.Search in Google Scholar

Ceong, Hailey Hyekyeong & Leslie Saxon. 2020. Addressee honorifics as allocutive agreement in Japanese and Korean. In Angelica Hernández & M. Emma Butterworth (eds.), Proceedings of the 2020 annual conference of the Canadian Linguistic Association, 1–15.Search in Google Scholar

Choe, Jae-Woong. 2004. Obligatory honorification and the honorific feature. Studies in Generative Grammar 14(4). 545–559.Search in Google Scholar

Choi, Jaehoon & Heidi Harley. 2019. Locality domains and morphological rules: Phases, heads, node-sprouting and suppletion in Korean honorification. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 37(4). 1–47.10.1007/s11049-018-09438-3Search in Google Scholar

Choi, Kiyong. 2010. Subject honorification in Korean: In defense of Agr and Head-Spec agreement. Language Research 46(1). 59–82.Search in Google Scholar

Chung, Inkie. 2009. Suppletive verbal morphology in Korean and the mechanism of vocabulary insertion. Journal of Linguistics 45(3). 533–567. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0022226709990028.Search in Google Scholar

Cinque, Guglielmo. 2004. “Restructuring” and functional structure. In Adriana Belletti (ed.), Structures and beyond: The cartography of syntactic structures, Volume 3, 132–191. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780195171976.003.0005Search in Google Scholar

Emonds, Joseph. 1970. Root and structure-preserving transformations. Ph.D. dissertation, MIT.Search in Google Scholar

Haegeman, Liliane & Virginia Hill. 2013. The syntacticization of discourse. In Raffaella Folli, Christina Sevdali & Robert Truswell (eds.), Syntax and its limits, 370–390. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199683239.003.0018Search in Google Scholar

Hill, Virginia. 2007. Vocatives and the pragmatics-syntax interface. Lingua 117(12). 2077–2105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2007.01.002.Search in Google Scholar

Hong, Yong-Tcheol. 2018. Mwuncangcongkyelemiuy naypho kanungsengkwa hwahayng thwusapemcwu [Embeddability of sentence end particles in Korean and speech act projections]. Studies in Generative Grammar 28(3). 527–552. https://doi.org/10.15860/sigg.28.3.201808.527.Search in Google Scholar

Hong, Yong-Tcheol. 2022. Hankuwkeuy sangtay nophimpep [Remarks on addressee honorification in Korean]. Studies in Generative Grammar 32(1). 195–220.Search in Google Scholar

Huidobro, Susana. 2022. Non-argumental clitics in Spanish and Galician: A case study of the distribution of solidarity and ethical clitics. Ph.D. dissertation. City University of New York.Search in Google Scholar

Kang, Myung-Yoon. 1988. Topics in Korean syntax: Phrase structure, variable binding, and movement. Ph.D. dissertation, MIT.Search in Google Scholar

Kaur, Gurmeet & Akitaka Yamada. 2022. Honorific (mis)matches in allocutive languages with a focus on Japanese. Glossa 7. 1–38. https://doi.org/10.16995/glossa.7669.Search in Google Scholar

Kim, Jong-Bok & Peter Sells. 2007. Korean honorification: A kind of expressive meaning. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 16(4). 303–336. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10831-007-9014-4.Search in Google Scholar

Kim, Yong-Ha. 2012. Noun classes and subject honorification in Korean. Linguistic Research 29(3). 563–578. https://doi.org/10.17250/khisli.29.3.201212.005.Search in Google Scholar

Koizumi, Masatoshi. 1991. Syntax of adjuncts and the phrase structure of Japanese. Columbus, OH: Ohio: State University MA thesis.Search in Google Scholar

Koizumi, Masatoshi. 1993. Modal phrase and adjuncts. In Clancy Patricia (ed.), Proceedings of Japanese/Korean linguistics 2, 409–428. Stanford, CA: Center for the Study of Language and Information.Search in Google Scholar

McFadden, Thomas. 2020. The morphosyntax of allocutive agreement in Tamil. In Peter W. Smith, Johannes Mursell & Katharina Hartmann (eds.), Agree to agree: Agreement in the minimalist programme, 391–424. Berlin: Language Science Press.Search in Google Scholar

Miyagawa, Shigeru. 2012. Agreements that occur mainly in the main clause. In Lobke Aelbrecht, Liliane Haegeman & Rachel Nye (eds.), Main clause phenomena. New horizons, 79–111. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/la.190.04miySearch in Google Scholar

Miyagawa, Shigeru. 2017. Agreement beyond phi. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.10.7551/mitpress/10958.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Miyagawa, Shigeru. 2022. Syntax in the treetops. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.10.7551/mitpress/14421.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Oyharçabal, Bernard Beñat B. 1993. Verb agreement with nonarguments : On allocutive agreement. In José Ignacio Hualde & Jon Ortiz de Urbina (eds.), Generative studies in Basque linguistics, 89–114. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing.10.1075/cilt.105.04oyhSearch in Google Scholar

Park, So-Young. 2019. Korean independent words and the syntactic representation of discourse information [Hankwuke toklipsengpwunkwa hwayong cengpouy thongsakwuco phyosang]. Kwukehak 89. 25–62. https://doi.org/10.15811/jkl.2019.89.002.Search in Google Scholar

Portner, Paul, Miok Pak & Raffaella Zanuttini. 2019. The speaker-addressee relation at the syntax-semantics interface. Language 95(1). 1–36. https://doi.org/10.1353/lan.2019.0008.Search in Google Scholar

Portner, Paul, Miok Pak & Raffaella Zanuttini. 2022. Dimensions of honorific meaning in Korean speech style particles. Glossa 7. 1–33. https://doi.org/10.16995/glossa.8182.Search in Google Scholar

Ross, Robert. 1970. On declarative sentences. In Roderick A. Jacobs & Peter S. Rosenbaum (eds.), Readings in English transformational grammar, 222–272. Waltham: Xerox College Publishing.Search in Google Scholar

Sohn, Ho-Min. 1999. The Korean language. New York: Cambridge University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Speas, Margaret & Carole Tenny. 2003. Configurational properties of point of view roles. In Anna Maria Di Sciullo (ed.), Asymmetry in grammar, 315–344. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/la.57.15speSearch in Google Scholar

Ura, Hiroyuki. 2000. Checking theory and grammatical functions in generative grammar. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780195118391.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Yamada, Akitaka. 2019. The syntax, semantics and pragmatics of Japanese addressee-honorific markers. Ph.D. dissertation, Georgetown University.Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Articles

- A comparative syntax of the formal politeness markers in Japanese and Korean: -Mas/-Des and -(Su)pni

- Negative concord by phase: multiple downward agree and the parametrization of edge features

- Complex weight distinctions in Harmonic Serialism

- A footless stroll through Italian stress

- Proleptic objects as complex-NPs

- Specifier-to-head reanalysis: evidence from mandarin and Cantonese

- The interaction between modality and negation in Turkish

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Articles

- A comparative syntax of the formal politeness markers in Japanese and Korean: -Mas/-Des and -(Su)pni

- Negative concord by phase: multiple downward agree and the parametrization of edge features

- Complex weight distinctions in Harmonic Serialism

- A footless stroll through Italian stress

- Proleptic objects as complex-NPs

- Specifier-to-head reanalysis: evidence from mandarin and Cantonese

- The interaction between modality and negation in Turkish