Abstract

The paper postulates that the propensity of Polish velar consonants to undergo palatalization is the consequence of the activity of a violable constraint which requires autosegmental place nodes to be associated with one and only one element. Since velars are the only consonants which lack place specification, the spreading of the palatality element |I| onto velars leads to the avoidance of the violation of the relevant constraint. As the palatalizing element |I| must entertain the status of the head, the underapplication of Surface Velar Palatalization before the front mid nasal vowel /ɛ̃/, headed by element |L|, and the vowel /ɛ/ found in some borrowings and headed by element |A|, is enforced by the constraint punishing representations in which more than one element plays the role of the head.

1 Introduction

This paper addresses the nature of consonant-vowel interaction in Polish with a particular focus on the process of Surface Velar Palatalization (SVP). It is argued that SVP is driven by the requirement of autosegmental place nodes to carry unambiguous featural specification. This requirement is formalized as a constraint referred to as the Single Place Element Condition (Spec), presented in (1).

| Single Place Element Condition (Spec): a place node must be specified for one, and only one, element |

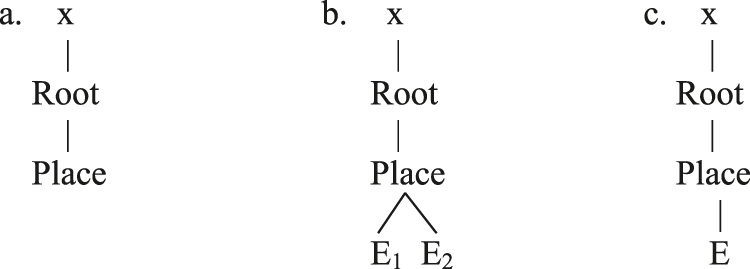

The configurations that violate Spec are presented in (2a–b). The configuration in (2c) does not incur violation of the constraint.

|

Following Rice (1993, 1996, Gussmann (2007), and Cyran (2010), I take configuration (2a), in which a consonant is not specified for any place-defining prime or feature, to be realized as the velar place of articulation. Following Harris (1994), Nasukawa and Backley (2008), and Backley (2011), I assume the configuration in (2b) to be found in affricates as well as consonants with secondary articulation, such as alveo-palatal fricatives, palato-labials but also coronal laterals and mid-vowels. Configuration (2c), which obeys Spec, is the specification of the labial, coronal (dental and alveolar) and palatal place of articulation, as well as, peripheral vowels.

If Spec occupies a privileged position among the constraints of a given system, velars and segments with complex resonance have a marked status in this system. I will argue that this situation obtains in Polish and is the driving force behind Surface Velar Palatalization, which turns the velar consonants /k/, /g/ and /x/ into palato-velar or palatal [c], [ɟ] and [ç].

To be more precise, I will show that assuming the activity of the constraint Spec in Polish allows us to propose an elegant account of the application of SVP in velars as well as the absence of palatalization of labials and coronals in the contexts in which velars are affected. In short, if palatalization involves the augmentation of a place node with the palatality element |I|, the non-application of palatalization to velars and the application of palatalization to labials and coronals give rise to the output representations as in (2a) and (2b) and trigger violation of Spec.

SVP underapplies in two contexts: before the front mid nasal vowel /ɛ̃/ and before the front mid vowel /ɛ/ in certain classes of borrowings. Since element |I| assumes the role of the head in vowels and consonants that share it, the palatalization by |A|-headed /ɛ/ found in certain loanwords, and the |L|-headed /ɛ̃/ are suboptimal for the same reason: they create marked structures with two elements playing the role of the head.

In Section 2.1 I discuss the opaque nature of the palatalization phenomena present in Polish, and argue for a distinction between morpho-lexically conditioned and phonologically conditioned palatalizations. Section 2.2 contains an overview of the data concerning Surface Velar Palatalization that will be analysed in this study. In Section 3 I discuss the approach to the interaction of velars and front vowels proposed in Gussmann (2004, 2007, which was the first such account formulated in the framework of Element Theory and may, therefore, be seen as the direct competitor to the current account. In Section 4 I provide the most important features of the frameworks assumed in this study: the Two-Level Containment version of Optimality Theory and Element Theory. Section 5 provides the OT-Element Theory based analysis of the data discussed in Section 2. Section 6 concludes the article.

2 The nature of consonant-vowel interaction in Polish

2.1 The morpho-lexical and phonological conditioning of Polish palatalizations

Velar consonants in Polish are subject to three regular and productive processes illustrated in (3).

| The 1st Velar Palatalization | |

| tłu/k/-ę ‘I break’ – tłu/t͡ʂ-ɛ/-sz ‘you break’ | ubo/ɡ/-a ‘poor, fem.’ – z-ubo/ʐ-ɛ/-ć ‘become poor’ |

| mó/zɡ/ ‘brain’ – mó/ʐd͡ʐ-ɛ/k ‘dim.’ | karalu/x/ ‘cockroach’ – karalu/ʂ-ɛ/k ‘dim.’ |

| The 2nd Velar Palatalization | |

| rę/k/-a ‘arm’ – rę/͡ts-ɛ/ ‘dat, sg.’ | no/ɡ/-a ‘leg’ – no/d͡z-ɛ/ ‘dat/loc, sg. |

| mu/x/-a ‘fly’ – mu/ʂ–ɛ/ ‘dat, sg.’ | |

| Surface Velar Palatalization | |

| krót-/k/-a ‘short, fem’ – krót-/c-ɛ/ ‘short, pl.’ | sza/x/-y ‘chess’ – sza/ç-i/sta ‘chess player’ |

| dłu/ɡ/-a ‘long, fem.’ – dłu/ɟ-ɛ/go ‘gen, sg, masc.’ | |

The 1st Velar Palatalization (3a) derives post-alveolar retroflex affricates from velar stops, with /ɡ/ undergoing further spirantization to /ʐ/. The velar spirant is turned into the retroflex spirant. The 2nd Velar Palatalization (3b) turns velar stops into dental affricates, while the velar spirant surfaces as the [ʂ]. Finally, Surface Velar Palatalization (3c) derives palatal stops and the palatal fricative.

All of these changes, with the exception of /x/ → /ç/, may be observed in the environment of the front vowel /ɛ/. This fact, as well as the observation that the presence of the front vowel is neither necessary (4a–c) nor sufficient (4d) for the first two processes to apply, convinced many researchers to treat the 1st and 2nd Velar Palatalization (VP) as conditioned by morpho-lexical rather than overtly phonological factors (see Czaplicki 2013; Czaykowska-Higgins 1988; Dressler 1985; Gussmann 1992, 2007; Spencer 1986; Zdziebko 2015). In other words, the 1st and 2nd VP follow from certain idiosyncratic properties of morphological exponents that form the words in which such palatalizations are observed.

| a. no/ɡ/-a ‘leg’ – nó/ʐ-k/-a ‘dim.’ | c. bla/x/-a ‘brass’ – bla/ʂ-an/n-y ‘of brass’ |

| b. tłu/k/-ę ‘I break’ – tłu/t͡s/ ‘break’ | d. su/x/-a ‘dry, fem.’ – su/x-ɛ/go ‘gen, sg, masc.’ |

The current study follows this tradition and recognizes that the 1st and 2nd VP should not be derived without the employment of morphological and lexical devices. Moreover, following the sources quoted above, I take other opaque segmental alternations such as Coronal, Labial and J-Palatalization to also be morpho-lexically conditioned. The opaque nature of the three changes is illustrated in (5) where it is shown that the environment of the front vowel /ɛ/ does not guarantee that the three processes apply. Moreover, Coronal and J-Palatalization derive different outputs of the same coronal consonants in the environment of the same vowel /ɛ/.

| Stem | Palatalization before /ɛ/ | No palatalization before /ɛ/ | ||

| a. | Coronal Palatalization | ko/t/ ‘cat’ | ko/t͡ɕ-ɛ/ ‘loc, sg.’ | ko/t-ɛ/m ‘inst, sg.’ |

| są/d/-y ‘court, pl.’ | są/d͡ʑ-ɛ/ ‘dat, sg.’ | są/d-ɛ/m ‘inst, sg.’ | ||

| pa/s/ ‘belt’ | pa/ɕ-ɛ/ ‘loc, sg.’ | pa/s-ɛ/k ‘dim.’ | ||

| po/z/-a ‘pose’ | po/ʑ-ɛ/ ‘dat, sg.’ | po/z-ɛ/r ‘poser’ | ||

| b. | Labial Palatalization | ra/p/ ‘rap music’ | ra/pʲ-ɛ/ ‘loc, sg.’ | ra/p-ɛ/r ‘rapper’ |

| gru/b/-y ‘thick’ | gru/bʲ-ɛ/j ‘thicker, adv.’ | gru/b-ɛ/j ‘gen, sg, fem.’ | ||

| tra/v/-a ‘grass’ | tra/vʲ-ɛ/ ‘dat, sg.’ | tra/v-ɛ/k ‘dim, gen, sg.’ | ||

| sze/f/ ‘boss’ | sze/fʲ-ɛ/ ‘loc, sg’ | sze/f-ɛ/m ‘inst, sg.’ | ||

| c. | J-Palatalization | po/t/ ‘sweat’ | po/t͡s-ɛ/nie ‘sweating’ | po/t-ɛ/m ‘sweat, inst, sg.’ |

| są/d/-y ‘court, pl.’ | są/d͡z-ɛ/nie ‘judging’ | są/d-ɛ/m ‘court, inst, sg.’ | ||

| pa/s/ ‘belt’ | opa/ʂ-ɛ/ ‘tie up, 3rd sg.’ | pa/s-ɛ/k ‘belt, dim.’ | ||

| wo/z/-y ‘cart, pl.’ | wo/ʐ-ɛ/nie ‘carrying’ | wó/z-ɛ/k ‘cart, dim.’ |

The morphological and lexical conditioning of the changes illustrated in (3a–b), (4) and (5) has taken many guises in the existing literature, from the approaches which completely deny any involvement of phonology (e.g. Czaplicki 2013; Gussmann 2007) to those which treat the relevant palatalizations as the integration of floating palatalizing autosegments (see Gussmann 1992).

This study follows Gussmann (1992) and Zdziebko (2015) in assuming that the morpho-lexically-driven palatalizations involve the integration of floating autosegments into the phonological structure of the stem. The relevant autosegments are part of the lexical representation of the exponents in the environment of which palatalizations take place.

Under this set of assumptions, the presence or absence of the 1st and 2nd VP, as well as Coronal, Labial and J-Palatalization, is independent of the overt segmental environment in which the input consonants are found, e.g. whether they are found in the environment of front or back vowels. Instead, the application of those changes is crucially dependent on the idiosyncratic lexical properties of the morphological exponents involved.

The point of departure of this study is that the nature of Surface Velar Palatalization (3c) is different from that of the morpho-lexically-driven palatalizations. The presence of the surface front vowel in the environment of the velar consonant is a necessary condition for SVP to take place. In fact, this paper argues that the existence of SVP provides certain crucial insights into the interaction of consonants and front vowels. In what follows, I show that once morpho-lexically-driven palatalizations are taken out of the equation, Polish velar consonants show an intriguing propensity to undergo palatalization in the environments in which labial and coronal consonants remain unaffected.

2.2 The data: SVP, fronting, raising and retraction

In Polish, the velar plosives /k/ and /ɡ/ cannot be followed by the front centralized vowel /ɨ/. Thus, when an exponent beginning with the lexical vowel /ɨ/ is concatenated with a stem terminating in a velar stop, the result is the emergence of a palatal stop and the front vowel [i]. For instance, this is the case with the Genitive singular ending (see 6 o–p).

|

The Genitive singular ending is fronted and surfaces as the vowel [i] if the root terminates in a soft consonant, i.e. the semi vowel /j/, a prepalatal, the lateral /l/, palato-labial, as well as a derived palatal stop (see 6j–p). The non-fronted realization [ɨ] is attested if the stem terminates in a hard consonant (see 6a–i).

The table above shows that the velar spirant (see 6i) does not participate in the processes that velar plosives participate in: the Genitive ending concatenated with stems ending in /x/ surfaces as [ɨ] and no palatalization is attested (see e.g. Gussmann 1992: 41, 2007; Laskowski 1975: 116; Rubach 1984: 156 for analyses).

A very similar situation is observed in the case of all endings beginning with the front mid vowel /ɛ/. Thus, the Instrumental singular ending -em /ɛm/, attested in masculine and neuter nouns, provokes the SVP of velar plosives (7g, h) but does not affect other consonants, including the velar spirant /x/ (7d).

|

As illustrated in examples (7e–h), when found after soft consonants the vowel /ɛ/ undergoes raising to the close mid vowel /e/. Vowel raising is a well-known property of the vocalic system of Polish (see Sawicka 1995; Wierzchowska 1980; Wiśniewski 2000). The set of consonants which provoke raising includes the palatalized velars, thus vowel raising is clearly fed by SVP.

Although the process of vowel raising after soft consonants has been included in most descriptions of the phonetic system of Polish, it has not figured very prominently in the phonological analyses of the language.[1] In the analysis presented in Section 5, I will show that the front mid vowel raising is a necessary corollary of SVP to the extent that the blocking of vowel raising leads to the blocking of SVP.

This sort of blocking is observed in the environment of the front nasal vowel /ɛ͂/, which realizes the Accusative singular of feminine nouns and the 1st person singular non-past tense in verbs. The data in (8) illustrate a case of surface opacity, as the nasal vowel /ɛ͂/ normally undergoes a process of denasalization (see Gussmann 2007: 69; Laskowski 1975: 117) and is realized with nasality only in heavily guarded formal speech.

| a. fo/k-ɛ͂/ → fo[kɛ] *fo[ce] ‘seal’ | d. Ry/ɡ-ɛ͂/ → Ry[ɡɛ] *Ry[ɟe] ‘Riga’ |

| b. rę/k-ɛ͂/ → rę[kɛ] *rę[ce] ‘arm’ | e. tłu/k-ɛ͂/ → tłu[kɛ] *tłu[ce] ‘I beat’ |

| c. no/ɡ-ɛ͂/ → no[ɡɛ] *no[ɟe] ‘leg’ | f. mo/ɡ-ɛ͂/ → mo[ɡɛ] *mo[ɟe] ‘I can’ |

Needless to say, coronals, labials and /x/ do not undergo palatalization in the context of the denasalized -ę /ɛ͂/ either.

Turning to the details of the behaviour of the velar spirant /x/, it is not completely immune to Surface Velar Palatalization. (9) presents examples containing the agentive affix -ist-/-yst-, which regularly triggers the change of all velars into palatals.

| SOK /sɔk/ ‘Railroad Guard’ – SOKista [sɔc-ista] ‘member of Railroad Guard’ |

| czołg /t͡ʂɔwɡ/ ‘tank’ – czołgista [t͡ʂɔwɟ-ista] ‘tank driver’ |

| szachy /ʂax-ɨ/ ‘chess’ – szachista [ʂaç-ista] ‘chess player’ |

In the same context, labials usually surface as palato-labials although this generalization admits exceptions (see 10b). Dentals, on the other hand, show more variability than labials. Many stems terminating in dentals retain hard consonants, in which case the vowel in the affix undergoes the retraction to [ɨ] (10c–d), or undergoes a morpho-lexically-driven Coronal Palatalization, which turns dentals into prepalatals (10e–f). In sum, only velars undergo palatalization in the context of the affix -ist-/-yst- regularly and without exceptions.

| Araba [arab-a] ‘Arab, acc, sg.’ – arabista [arabj-ista] ‘Arabist’ |

| lobbować [lɔbb-ɔvat͡ɕ] ‘to lobby’ – lobbysta [lɔbb-ɨsta] ‘lobbyist’ |

| stypendium [stɨpɛnd-jum] ‘scholarship’ – stypendysta [stɨpɛnd-ɨsta] ‘scholar’ |

| Adwent [advɛnt] ‘Advent’ – Adwentysta [advɛnt-ɨsta] ‘adventist’ |

| rekord [rɛkɔrd] ‘record’ – rekordzista [rɛkɔrd͡ʑ-ista] ‘record holder’ |

| klarnet [klarnɛt] ‘clarinet’ – klarnecista [klarnɛt͡ɕ-ista] ‘clarinetist’ |

As pointed out by Rubach (1981: 102), very similar facts are observed in the context of several other derivational affixes attested in Polish. These are -izm-/-yzm-, corresponding to the affix -ism attested in English (cf. parok[s-ɨ]zm ‘paroxysm’ vs. mark[ɕ-i]zm ‘Marxism’ vs. hob[b-ɨ]zm ‘having a hobby’ vs. troc[c-i]zm ‘Trockyism’), and -ik-/-yk- corresponding historically to the affix -ic/-ique (mu[z-ɨ]k-a ‘music’ vs. tech[--i]ka ‘technique’ vs. psy[ç-i]ka ‘psyche’), as well as a much less frequent affix -in-/-yn- (cf. gospo[d-ɨ]ni ‘hostess’ vs. monar[ç-i]ni ‘female monarch’).

The interpretation of the effect of the said affixes is complicated by the attested variation and their status as graphic borrowings.[2] An example of a native affix in front of which velars show different behaviour than all coronals and labials is the Secondary Imperfective suffix -iw-/-yw- /iv/. Here again, velar plosives and the velar spirant undergo SVP and surface as palatals (see 11).

| Perfective Infinitive | Secondary Imperfective | Glosses | |

| a. | poszu[k]-ać | poszu[c-i]w-ać | ‘look for’ |

| b. | wystru[ɡ]-ać | wystru[ɟ-i]w-ać | ‘carve’ |

| c. | przesłu[x]-ać | przesłu[ç-i]w-ać | ‘interrogate’ |

At the same time, labials and coronals do not undergo any changes in the same context, while the vowel in the suffix is retracted to [ɨ] (see 12).

| Perfective Infinitive | Secondary Imperfective | Glosses |

| podszczy/p/-ać | podszczy/p-ɨ/w-ać | ‘pinch’ |

| poka/z/-ać | poka/z-ɨ/w-ać | ‘show’ |

| rozga/d/-ać | rozga/d-ɨ/w-ać | ‘spread the news’ |

| wyg/r/-ać | wyg/r-ɨ/w-ać | ‘win’ |

| przeko/n/-ać | przeko/n-ɨ/w-ać | ‘convince’ |

| obie/t͡s/-ać | obie/t͡s-ɨ/w-ać | ‘promise’ |

The available analyses of SVP typically treat the Secondary Imperfective affix as beginning in the vowel /ɨ/ (see Gussmann 1980; Laskowski 1975; Rubach 1984). This decision is dictated by the view according to which palatalization of consonants in Polish is enforced by the presence of the feature [−back] on the following vowel. According to such traditional analyses, since Coronal, Labial, 1st Velar and 2nd Velar Palatalization do not take place in front of the affix -iw-/-yw-, the vowel in the affix cannot be front, i.e. /i/. It must be marked as [+back], i.e. /ɨ/

If we assume that the SI affix begins with the [+back] vowel, then it is immediately possible to account for the absence of palatalization of labials and coronals in the environment of this affix. At the same time, we are forced to treat the palatalization of the velar spirant /x/ before the affix -iw-/-yw- (see 11c) as unexpected and account for it somehow. This has been achieved by introducing specific clauses into the formulation of the rules of /ɨ/-Fronting or Surface Velar Palatalization, enforcing the extension of those rules to the environment of the SI affix (see Gussmann 1980: 23, 1992: 40; Laskowski 1975: 116; Rubach 1984: 156; Szpyra 1995: 214).

Under the assumption that processes such as Coronal/Labial Palatalization and 1st and 2nd Velar Palatalization have nothing to do with the quality of the vowel that follows the palatalized consonant, as claimed in Dressler (1985), Spencer (1986), Czaykowska-Higgins (1988), Gussmann (1992, 2007, Czaplicki (2013), and Zdziebko (2015) and in this work, the absence of the palatalization of coronals and labials before the affix -iw-/-yw- is also nothing out of the ordinary. Since Coronal/Labial, 1st and 2nd Velar Palatalizations take place in lexically-defined environments, the only thing that has to be said is that the affix -iw-/-yw- does not belong to the set of affixes marked with the relevant kind of (non-)phonological diacritics responsible for triggering the said palatalization processes.

Given the morpho-lexical nature of most palatalization processes attested in Polish, it may well be assumed that the initial vowel of the affix -iw-/-yw- is the front vowel /i/, and if one assumes that the rule of SVP turns all velars into palatals in front of the vowel /i/, then the affix -iw-/-yw- does not have to be treated as special in any way.

The final set of data discussed in this section illustrates the issue of the (non-)application of SVP in words of foreign origin attested in Polish. Many pre-nineteenth-century borrowings (13a–d), as well as very recent post-1950s loanwords (13e–h) resist SVP before the mid vowel /ɛ/ found morpheme-internally (see Boryś 2005; Brückner 1927; Dłuogosz-Kurczabowa and Dubisz 2006; Rubach 2019; Sławski 1952; Stieber 1973 for discussion).

| a. kelner [kɛlnɛr] *[celnɛr] ‘waiter’ | e. hokej [xɔkɛj] *[xɔcej] ‘hockey’ |

| b. gest [ɡɛst] *[ɟest] ‘gesture’ | f. kebab [kɛbab] *[cebab] ‘kebab’ |

| c. ewangelia [ɛvaŋgɛlja] *[ɛvaŋɟelja] ‘gospel’ | g. gem [ɡɛm] *[ɟem] ‘game’ |

| d. kefir [kɛfjir] *[cefjir] ‘yoghurt’ | h genetyka [ɡɛnɛtɨka] *[ɟenɛtɨka] ‘genetics’ |

Importantly, both the old and more recent borrowings show SVP before inflectional endings, e.g. the Instrumental affix -em /ɛm/ (see 14).

| a. gan/ɡ-ɛm/ [ɡaŋɟem] *[ɡaŋɡɛm] ‘gang’ | c. ke/ɡ-ɛm/ [kɛɟem] *[kɛɡɛm] ‘keg’ |

| b. roc/k-ɛm/ [rɔcem] *[rɔkɛm] ‘rock’ | d. Gen/k-ɛm/ [ɡɛŋcem] *[ɡɛŋkɛm] ‘Genk’ |

SVP is not restricted to the environment of morpheme boundaries in native Polish vocabulary (15a). In addition, SVP applies word-internally also in certain borrowings (15b). Loanwords in which a velar plosive is followed by the vowel /i/ undergo SVP regularly (see 15c).

| a. | b. | c. |

| kiedy [cedɨ] ‘when’ | giermek [ɟermɛk] ‘squire’ | kilof [cilɔf] ‘pick’ |

| skiełznąć[scewznɔŋt͡ɕ] ‘slide’ | kaszkiet [kaʃcet] ‘cap’ | kitel [citɛl] ‘overall’ |

| kiełbasa [cewbasa] ‘sausage’ | ogier [ɔɟer] ‘stallion’ | legginsy [lɛɟinsɨ] ‘leggings’ |

| kiełb [cewb] ‘gudgeon’ | lakier [lacer] ‘lacquer’ | girlanda [ɟirlanda] ‘garland’ |

Moreover, SVP may (16a) or may not (16b) be triggered by non-etymological yer vowels, i.e. alternating mid vowels, found in words of foreign origin. Etymological yers always trigger SVP in /k/ and /ɡ/ (see 16c).

| łagier [waɟer] ‘camp’ – łagr-u [wagru] ‘gen, sg.’ |

| singiel [sjiŋɟel] ‘single’ – singl-a [sjiŋɡla] ‘gen, sg.’ |

| cukier [t͡sucer] ‘sugar’ – cukr-u [t͡sukru] ‘gen, sg.’ |

| Hegel [xɛɡɛl] ‘Hegel’ – Hegl-a [xɛɡla] ‘gen, sg.’ |

| Spiegel [ʂpjiɡɛl] ‘Der Spiegel’ – Spiegl-u [ʂpjiɡlu] ‘loc, sg.’ |

| szekel [ʂɛkɛl] ‘shekel’ – szekl-e [ʂɛklɛ] ‘nom, pl.’ |

| kr-a [kra] ‘ice float’ – kier [cer] ‘gen, pl’ |

| okn-o [ɔknɔ] ‘window’ – okien [ɔcen] ‘gen, pl.’ |

| gr-a [ɡra] ‘game’ – gier [ɟer] ‘gen, pl’ |

| ogni-a [ɔɡŋa] ‘fire, gen, sg.’ – ogień [ɔɟe-] ‘fire’ |

To summarize the application of SVP in non-native vocabulary, many words of foreign origin undergo the rule only if the trigger is part of the inflectional affix (cf. kegi-em /kɛɟem/ ‘keg, inst, sg.’). Some undergo SVP when the /ɛ/ is a vocalized alternating vowel (cf. łagier /waɟer/ ‘camp’ – łagr-u /wagru/ ‘gen, sg.), although borrowings which do not show palatalization before the alternating vowel are also attested (cf. Hegel /xɛɡɛl/ ‘Hegel’ – Hegl-a /xɛɡla/ ‘gen, sg.’). At the same time, there are instances of borrowings which show SVP morpheme internally (lakier /lacer/ ‘lacquer’). Words borrowed with the close front vowel /i/ always show SVP (cf. girlanda /ɟirlanda/ ‘garland’).[3] No derived environment effect is attested in native vocabulary.

According to Rubach (2019), the derived environment effect attested in SVP is the consequence of the high ranking of the constraint Derived Environment-PAL (DE-PAL), which requires the consonant and vowel that agree in feature [−back] to be part of different morphemes. Rubach also contends that the floating vowels in Polish are glides and trigger palatalization as a result of the high ranking of the constraint PAL-Glide. The data in (16b) contradict the claim that SVP triggered by yers is ‘… entirely exceptionless and fully productive’ (Rubach 2019: 1439).

To conclude this section, below I formulate five questions that a comprehensive analysis of the interaction of Polish front vowels and consonants should be able to answer:

Why are /k/ and /ɡ/ impossible before the centralized high vowel /ɨ/, while labial and coronal consonants are perfectly grammatical in the same context?

Why do velar plosives undergo palatalization in environments in which coronal and labial segments remain unaffected?

Why do /k/ and /ɡ/ not undergo palatalization before the underlyingly nasal front vowel /ɛ͂/?

Why do /k/ and /ɡ/ undergo palatalization before /ɛ/ as well as /ɨ/ and /i/, while /x/ is palatalized only before the close front /i/?

Why is the palatalization of /k/ and /ɡ/ blocked before /ɛ/ (in non-derived and derived environments) in some words of foreign origin?

The answers to these questions will be provided in Section 5. In what follows I discuss an existing analysis of SVP conducted in Element Theory and put forward in Gussmann’s (2004, 2007.

3 Gussmann’s (2004, 2007 analysis of SVP

Gussmann (2004, 2007 is the first analysis of consonant-vowel interaction in Polish couched within Element Theory.[4] Hence, it may be viewed as a direct competitor to the analysis promoted here. In what follows, I address the most important aspects of Gussmann’s analysis. The discussion will focus on how Gussmann’s approach answers the five questions posed at the end of the previous section.

3.1 Why are /k/ and /ɡ/ impossible before the centralized high vowel /ɨ/, while labial and coronal consonants are perfectly grammatical in the same context?

As in the current study, in Gussmann (2004, 2007 velars are assumed not to be specified for the place-defining element. For Gussmann, this translates into velars not possessing an element playing the role of the head.[5]

The answer provided by Gussmann (2004, 2007 to the question concerning the defective distribution of velar stops vis à vis other consonants is that velars are the only empty-headed segments and that they cannot be followed by /ɨ/ and /ɛ/, the only empty-headed vowels. The constraint Empty Heads (17) prevents headless consonant from being licensed by a headless vowel effectively ruling out sequences such as /kɨ/ and /ɡɨ/.

| Empty Heads (Gussmann 2007:52) |

| An empty-headed nucleus cannot license an empty-headed onset. |

The strong point in favour of Empty Heads is that it accounts for a property of Polish which this article, admittedly, does not address, i.e. the absence of the vowel /ɨ/ word-initially. Polish does not feature native or foreign words beginning with /ɨ/. Gussmann (2004, 2007 follows most of the Government Phonology/Element Theory literature and assumes that vowel-initial words in fact begin with melodically empty onsets. Since empty onsets are treated as empty-headed, they cannot be licensed by an empty-headed vowel. In this way, the Empty Heads constraint accounts for two seemingly unrelated gaps in the distribution of the vowel /ɨ/: it is banned from occurring after velars and empty onsets, both of which form a natural class of headless consonants.

Unfortunately, if the logic by which the melodically empty constituents count as empty-headed is applied consistently, then no words in Polish should ever terminate in a velar. This is because, according to Gussmann’s analysis, all consonant-final words in Polish in fact terminate in melodically empty nuclei. This means that in every word terminating in a velar, the word-final empty-headed consonant is licensed by a melody-less, i.e. empty-headed, vowel. Such a configuration violates Empty Heads. Needless to say, Polish has no dearth of words ending in velars. Thus, the successful and unified analysis of the distribution of /ɨ/ turns out to make wrong predictions concerning the distribution of velars.

3.2 Why do velars undergo palatalization in environments in which coronal and labial segments remain unaffected?

According to Gussmann (2007: 53), when the morphological system of Polish concatenates a stem terminating in a velar plosive with an ending beginning with /ɨ/, the violation of Empty Heads causes the element |I| in the vowel to be promoted to the status of the head. This, in turn, provokes the violation of the I-alignment constraint (18), which results in the element |I|-head spreading from the vowel onto a consonant, i.e. in palatalization.

| I-alignment (Gussmann 2007:52) |

| A nucleus shares I-head with the onset it licenses. |

Thus, only velars undergo palatalization in the relevant environments, as only they are headless and only they require the promotion of element |I| in the vowel /ɨ/ to the status of the head (due to the working of Empty Heads). This activates I-alignment, which is satisfied by palatalization.

The same set of constraints provokes SVP in the context of the front mid vowel /ɛ/, which is analysed by Gussmann (2004, 2007 as a headless expression composed of element |A| and |I|. As such, /ɛ/ cannot license velars due to Empty Heads.

The I-alignment analysis of SVP faces some empirical and theoretical problems. As it stands, the I-alignment constraint predicts that no word in Polish should start with the vowel /i/. Recall that for Gussmann (2004, 2007, vowel-initial words actually begin with empty onsets. If I-alignment is to be followed to the letter, then words which lexically begin with /i/ should in fact share the |I|-element with the preceding onset. Such a configuration would give rise to a word initial [ji] sequence. The presence of [ji] word-initially is highly controversial in Standard Polish.[6]

In order to account for the highly marked status of initial [ji] in Polish, Gussmann postulates a constraint Operators required (see 19), which precludes the presence of the [ji] sequence by requiring the presence of other elements in the onset preceding /i/ or in the nucleus following /j/.

| Operators required (Gussmann 2007: 55) |

| Doubly attached {I} must license operators. |

If applied consistently, Operators required bans the [ji] sequence not only word-initially, but in all positions and contexts. This is certainly not desirable as Polish allows for the [ji] sequence to arise in the context of vowel hiatus (see Gussmann 2007: 54; Rubach 2000: 291 for examples).

In addition, as observed by Scheer (2010) in his in-depth review of Gussmann (2007), constraint Operators required is in conflict with I-alignment: if the former is satisfied by not spreading element |I|-head word-initially, the latter is disobeyed. This is at odds with the very general assumptions of Gussmann’s works. In principle, Gussmann’s (2004, 2007 analysis does not allow constraint conflicts: the constraints proposed there are inviolable and not ranked with respect to each other. Let me note, however, that the conceptual and empirical problems of Gussmann’s analysis pointed out above could be easily avoided if the constraints he postulated were openly treated as violable and ranked. As noted by Scheer (2010: 127) in a footnote, Gussmann categorically rejected such a solution.

3.3 Questions 3 and 5: no palatalization before /ɛ͂/ and /ɛ/ in borrowings

In the case of the front mid vowels which do not provoke Surface Velar Palatalization, Gussmann (2007: 61–72) offers a representational solution: the /ɛ/ found in non-native stems such as [kɛ]lner ‘waiter’ as well as the front mid nasal vowel /ɛ͂/, as in the Accusative singular ending no[ɡ-ɛ͂] ‘leg’, are claimed to be composed of elements |A|-head and |I|-operator, conventionally represented as {A.I}. As such, their presence after velars does not provoke the violation of Empty Heads and does not result in SVP.

3.4 Why do /k/ and /ɡ/ undergo palatalization before /ɛ/ as well as /ɨ/ and /i/, while /x/ is palatalized only before the close front /i/?

Let us recall that no palatalization is observed when the velar fricative /x/ is followed by a morpheme beginning with the high central /ɨ/, or mid front /ɛ/. In order to account for the underapplication of SVP in /x/, Gussmann postulates that the velar fricative is, in fact, composed of the noise element |h| entertaining the status of the head. The presence of headless vowels after |h|-headed consonants does not provoke the violation of Empty Heads, element |I| is not promoted to the status of the head and I-alignment is not violated.

At the same time, the velar spirant undergoes SVP before the affixes such as -ist-/-yst- ‘-ist’ and -izm-/-yzm- ‘-ism’ etc. and before the secondary imperfective affix -iw/yw-. In these cases, Gussmann postulates the usual, i.e. headless representation of the velar. Thus, the phonetic object realized as the voiceless velar fricative [x] is postulated to have two phonological representations: {h} and {h}. The former undergoes SVP before headless vowels, the latter does not.

One fact which causes certain complications for Gussmann’s analysis is that Polish possesses stems in which /x/ does not undergo SVP before inflectional endings beginning with /ɨ/ and /ɛ/, but undergoes the palatalization before the derivational affixes discussed in Sections 2. Some examples of such stems are presented in (20).

| STEM | NO SVP | SVP | |

| a. | szach- /ʂax/ | sza/x-ɨ/ ‘chess’ | sza/ç-i/sta ‘chess player’ |

| b. | słuch- /swux/ | pod-słu/x-ɨ/ ‘wiretapping’ | pod-słu/ç-iv/-ać ‘eavesdrop’ |

| c. |

monarch- /m narx/ narx/ |

monar/x-ɨ/ ‘monarch, gen, sg.’ | monar/ç-i/ni ‘female monarch’ |

Gussmann (2007: 88–89) recognizes the existence of such stems and claims that one and the same stem can terminate in a headless {h} or with a headed {h} depending on the morphophonological context. Gussmann (2007) does not explicitly state how such a morphophonologically driven distinction would be regulated in the case of stems terminating in /x/. However, one might speculate that the alternation between the two flavours of /x/ is triggered by the mechanism of affix specific diacritics, as this is the general mechanism responsible for the morhophonological alternations in Gussmann’s model.

The most important similarity between Gussmann’s (2004, 2007 analysis and the current analysis is the assumption that velars are unspecified for the place element. The most important difference between the two analyses is that the current work takes phonological constraints to be universal and violable. As the discussion in Section 5 unfolds, I will show how the analysis postulated here avoids the problems that Gussmann’s analysis faced.

4 Theoretical preliminaries

This study follows the general Optimality Theoretic assumptions concerning the interaction of phonological constraints and the relationship between the input and the output of the grammar (see Prince and Smolensky 2004). The following sections discuss the relevant aspects of the approach which elaborates on the standard OT architecture and which is employed in the analysis of the SVP data: the Two-Level Containment (Section 4.1). Section 4.2 introduces the relevant aspects of the approach to phonological representations assumed in this study, i.e. Element Theory (ET), and focuses on how ET may be applied to account for those properties of Polish consonants and vowels, which are vital for the analysis of SVP.

4.1 Two-Level Containment

Containment Theory is the name of the approach to the relationship between the input and generated candidates first formulated in McCarthy and Prince (1993) and assumed in Oostendorp (2006, 2007, Revithiadou (2007), Trommer and Zimmermann (2014), and Zimmermann and Trommer (2016) among others. McCarthy and Prince’s original formulation of Containment is presented in (21).

| Containment (McCarthy and Prince 1993: 21) |

| No element may be literally removed from the input form. The input is thus contained in every candidate form. |

The consequence of the Containment assumption which is of particular interest for the current analysis is that literal deletion of a feature, node or segment from representation is not possible, as such a step would mean removing a piece of the input representation. Following Trommer and Zimmermann (2014), I assume that the same holds for association lines. Thus, association lines are never removed from the representation. Instead, they may be marked as invisible to phonetic interpretation.

The specific theory of visibility that I assume here has been laid out in Trommer and Zimmermann (2014) and Zimmermann and Trommer (2016), where it was referred to as Two-Level Containment. According to Trommer and Zimmermann, the generation of candidates may include the addition of epenthetic association lines and the marking of association lines as phonetically invisible. In the latter case, the nodes and features which are located lower in the structure than the marked association lines are unparsed and unrealized. Epenthetic association lines are always visible to phonetic interpretation. Trommer and Zimmermann (2014) and Zimmermann and Trommer (2016) postulate that each markedness constraint has two clones: (i) a clone that refers to the Integrated Structure, i.e. the structure which includes all kinds of association lines, nodes and features regardless of whether they are phonetically visible or invisible; and (ii) the phonetic clone, which refers only to the phonetically visible structure. I will refer to the former as the I-constraints, and to the latter as P-constraints. By convention, I assume the constraints employed in the analysis that follows to be I-constraints, unless they are explicitly claimed to be P-constraints.

As shown by Zimmermann and Trommer (2016), material which is marked as invisible to phonetics may trigger or block phonological processes. In particular, they show that the unrealized intervocalic consonants in Lomongo block the gliding of the preceding vowel: a process which applies in the language before vowels, but not before consonants. In a similar vein, in Section 5.4. I show that the presence of a non-realized element responsible for nasality contributes to the blocking of the process of Surface Velar Palatalization in Polish.

4.2 Element Theory and the phonological system of Polish

The approach to the phonological make-up of segments assumed here is that of Element Theory (see Backley 2011; Cyran 2010, 2014; Gussmann 2007; Harris 1994; Harris and Lindsay 1995; Kaye et al. 1985 and for Polish). Element Theory takes segments as constituting sets of monovalent primes called elements. Elements are conceived of as cognitive primes in that their primary role is to encode phonologically relevant distinctions between segments. Their relation to the physical world is that they are extracted from and mapped onto certain acoustic patterns produced by speakers.

The elements are geometrically arranged into a subsegmental structure (see 22) which I adopt from Harris (1994: 129) and Harris and Lindsay (1995: 76).

|

According to Harris (1994, 1996 and Harris and Lindsay (1995), as well as Backley (2011), the element |A| is found in open and mid vowels as well as coronal and guttural consonants. Element |I| characterizes front vowels and palatal/post-alveolar consonants, while element |U| is attested in back vowels and labial consonants. Element |Ɂ| is correlated with the presence in the acoustic signal of the abrupt and sustained drop in the amplitude typically realized as occlusion in consonants. Element |H| is realized as the VOT lag in consonants, as aperiodic energy characteristic of fricatives and released stops, as well as the high tone in vowels. Element |L| is associated with VOT lead and the low tone in vowels as well as nasality.

I follow Nasukawa and Backley (2008) and Backley (2011) and assume that the autosegmental place nodes of a plosive associated with more than one element must involve a prolonged burst in order to help the listener recover the cues associated with the place of articulation. Thus, the delayed release associated with the pronunciation of affricates is treated as cue enhancement and is not represented phonologically as a contour structure of any kind. In short, affricates are plosives with complex place specification.

It is assumed that a given element may play the role of a head or of an operator. Being a head, as opposed to an operator, is correlated with greater acoustic prominence and typological markedness: the presence of a headed version of an element in a given language implies the presence of an operator version, as well as greater resistance to lenition (for discussion see Backley 2011). By convention, elements that function as heads are presented as underlined. The association of headedness with greater acoustic prominence justifies the analyses of the contrast between the peripheral front high vowel /i/, represented by the headed element |I|, and the centralized /ɨ/, represented as a non-headed structure possessing the |I|-operator in languages such as Polish (see e.g. Gussmann 2007: 43). Such a distinction is reflected in the acoustics of the two vowels: according to Wierzchowska (1980: 88), /i/ and /ɨ/ differ in that the former has F2 in a range from 2,500 to 3,000 Hz, while the F2 of the latter ranges from 2,000 to 2,300 Hz.

This postulated representational distinction between /i/ and /ɨ/ has important consequences for an analysis of the phonotactics of the language. The set of consonants after which the vowel /i/ is found in Polish is restricted to palato-labials, prepalatals, palatals, the semi-vowel /j/ and the lateral /l/. Since it is intuitively correct to claim that phonotactic restrictions of this sort should be represented as agreement or the sharing of a property, it follows that palato-labials, prepalatals, palatals, /j/ and /l/, as well as the vowel /i/, must all be |I|-headed segments. I take the distinction between the |I|-headed and non-|I|-headed consonants to be the major distinction cross-classifying the system of Polish consonants.

(23) summarizes the elemental make-up of Polish consonants that I propose. The segments which are not part of the underlying system of Polish are placed in square brackets ([…]).

| labials | /p/-{U.Ɂ.H} | /b/-{U.Ɂ.H.L} | /f/-{U.H} | /v/-{U.h.L} | /m/-{U.Ɂ.L} |

| palato-labials | /pʲ/-{U.I.Ɂ.H} | /bʲ/-{U.I.Ɂ.H.L} | /fʲ/-{U.I.H} | /vʲ/-{U.I.H.L} | /mʲ/-{U.I.Ɂ.L} |

| dentals | /t/-{A.Ɂ.H} | /d/-{A.Ɂ.H.L} | /s/-{A.H} | /z/-{A.H.L} | /n/-{A.Ɂ.L} |

| dental affricates | /t͡s/-{A.I.Ɂ.H} | /d͡z/-{A.I.Ɂ.H.L} | |||

| retroflexes | /t͡ʂ/-{A.I.Ɂ.H} | /d͡ʐ/-{A.I.Ɂ.H.L} | /ʂ/-{A.I.H} | /ʐ/-{A.I.H.L} | |

| prepalatals | /t͡ɕ/-{A.I.Ɂ.H} | /d͡ʑ/-{A.I.Ɂ.H.L} | /ɕ/-{A.I.H} | /ʑ/- {A.I.H.L} | /ɲ/-{A.I.Ɂ.L} |

| velars | /k/-{_.Ɂ.H} | /ɡ/-{_.Ɂ.H.L} | /x/-{_.H} | /ŋ/-{_.Ɂ.L} | |

| palatals | [c]-{I.Ɂ.H} | [ɟ]-{I.H.L} | [ç]-{I.H} | ||

| sonorants | /r/-{A} | [w] = {U} | /l/-{A.I.Ɂ} | /:/-{A.U.Ɂ} | /j/-{I} |

I also postulate that the mechanism of headedness be employed to represent the distinction between the place of articulation of the dental affricates /t͡s/ and /d͡z/[7] and the retroflex affricates and fricatives /t͡ʂ/, /d͡ʐ/, /ʂ/ and /ʐ/. I follow Backley (2011: 92), who treats retroflexes as |A|-headed consonants.

The third relevant distinction which depends on the notion of headedness concerns the contrast between nasal resonance and voicedness. The representations outlined above conform to the established tradition of encoding the nasality and voicing in obstruents by means of one and the same prime: the ‘low tone’ |L|. Some thorough arguments for the conflation of these two properties have been adduced in Ploch (1999, 2000 and Nasukawa (1998, 2005. This work follows Ploch (1999, 2000 and treats the element |L|-head to be interpreted as the voicing in consonants and nasality in vowels, and |L|-operator as nasality in consonants.[8]

I take it that elemental representations not attested in Polish are eliminated by segmental inventory constraints that refer directly to particular combinations of elements. Thus, segmental representations such as {U.ʔ}, {A.H}, {I.H}, etc. are eliminated by the prominent status of constraints *{U.ʔ}, *{A.H}, *{I.H} etc.

Similarly to Backley (2011: 200), I allow more than one element in a given segment to function as the head. Such a configuration is, however, marked and leads to the violation of constraint *Hydra, whose nature is further discussed in Section 5.4 below.

(24) presents postulated ET representations of Polish vowels.

| Vowel | Representation | Examples | Glosses |

| /i/ | {I} | /i/gła, l/i/tr, dług/i/ | ‘needle’, ‘litre’, ‘long’ |

| /ɨ/ | {I} | r/ɨ/ba, t/ɨ/p | ‘fish’, ‘type’ |

| /ɛ/ | {I.A} | t/ɛ/n, s/ɛ/r, | ‘this’, ‘cheese’, |

| /ɛ/ | {A.I} | k/ɛ/lner, Heg/ɛ/l | ‘waiter’, ‘Hegel’ |

| [e] | {I.A} | si[e]rp, ki[e]dy | ‘sickle’, ‘when’ |

| /a/ | {A} | t/a/ma, cz/a/s | ‘dam’, ‘time’ |

| /ɔ/ | {U.A} | r/ɔ/k, /ɔ/ko | ‘year’, ‘eye’ |

| /u/ | {U} | n/u/ta, c/u/d | ‘note’, ‘miracle’ |

| /ɛ͂/ | {I.A.L} | k/ɛ͂/s, r/ɛ͂/ka | ‘bit’, ‘hand’ |

| /ɔ͂/ | {U.A.L} | s/ɔ͂/, w/ɔ͂/ż | ‘they are’, ‘snake’ |

This paper follows the majority of the phonological literature on Polish and treats the vowels /i/ and /ɨ/ as part of the underlying inventory of the language despite the fact that their distribution is complementary.[9]

Following Gussmann (2007), I assume the existence of two objects corresponding to the vowel /ɛ/, the headless {A.I} found in the native vocabulary and those non-native words which show SVP, and the |A|-headed /ɛ/ found in those words of foreign origin which resist SVP. Although the raised versions of the vowels that follow soft consonants are completely predictable from the context and should not be treated as part of the underlying inventory of Polish, (24) includes the raised [e] as its representation is important for the details of the analysis presented in Section 5.

As can be seen in (23), I assume velar consonants to be unspecified for resonance or place elements (I use the underlining notation: ‘_’ to represent that). Many arguments supporting the claim that the velar place of articulation is the phonetic realization of non-specified place nodes can be found in Rice (1993, 1996. Rice (1993, 1996 argues that in many languages both coronal and velar consonants are represented with bare place nodes in the Underlying Representation. The two series are distinguished in the course of the derivation: the former undergoes the Coronal default rule, which results in the insertion of the sub-node Coronal. If the Coronal default rule is blocked, the unspecified place node is phonetically interpreted as the velar place of articulation. Moreover, Rice (1993, 1996 argues that in some languages the Coronal default rule does not apply and coronal specification is present underlyingly. Rice (1993: 120–121, 1996: 533–534) explicitly mentions Polish as an example of such a language. She quotes Czaykowska-Higgins (1992), who points to the existence of two classes of nasal consonants in Polish: one of the two classes possesses fully specified place of articulation nodes. The other class is underspecified for place and obtains it in the course of assimilation to the following non-continuant consonant or else is supplied with features DORSAL and [+back] by default. Rice claims that the latter option is actually the interpretation of the bare place node as the velar place of articulation. Thus, the claim that the velar place of articulation is the interpretation of the unmarked place node in Polish has been explicitly argued for – at least for some nasals.

In Element Theory literature, representing all Polish velars as not equipped with resonance elements is an established practice. The most widely quoted Element Theory-based accounts of Polish, i.e. Gussmann (2007) and Cyran (2010), assume exactly that. I follow the established analyses of Polish velars presented in Rice (1993, 1996, as well as Gussmann (2007) and Cyran (2010), and treat the velar place of articulation as the realization of the unspecified place node.[10]

5 Deriving surface velar palatalization

5.1 The constraints and the basic constraint ranking

Surface Velar Palatalization derives the palatal plosives [c] and [ɟ] from velar plosives when the latter find themselves in the context of the front high vowel /i/, the front centralized /ɨ/, as well as the front mid /ɛ/. The palatalization of velars before /ɨ/ is accompanied by the fronting of the vowel to [i], while SVP triggered by /ɛ/ is accompanied by the raising of the vowel to [e].

The velar spirant is not affected before /ɨ/ and /ɛ/ and surfaces as the palatal spirant [ç] only before /i/; a situation which systematically accompanies the concatenation of stems with certain affixes of foreign origin, including -ist-/-yst- ‘-ist’, -izm-/-yzm- ‘-ism’ and -ik-/-yk- ‘-ic/-ique’, and verbal stems with the Secondary Imperfective affix -iw-/-yw-.

The pervasive propensity of Polish velars to undergo palatalization is directly related to the ranking of the Single Place Element Condition (Spec). Spec is a general markedness constraint which requires segments to be associated with one, and only one, place element. I repeat its formulation in (25).

| Single Place Element Condition (Spec): a place node must be specified for one, and only one, element |

Spec favours segments which carry optimal, i.e. unambiguous, place specification. Hence, it punishes the presence of segments in which the place node is not associated with any element and segments in which a single place node hosts more than one element. In the architecture outlined in Section 4.2 this translates into penalizing velars as well as palato-labials, all affricates, post-alveolar and prepalatal fricatives, the lateral, and mid vowels. On the assumption that the relevant version of Spec is an I-constraint, i.e. it is violated by phonetically visible and invisible material, the violation of Spec can never be avoided by the ‘delinking’ of an element.

Given the autosegmental architecture assumed in this paper, one obvious repair strategy that may be employed to avoid the violation of Spec by velars, which do not host any resonance element, is the spreading of an element from the following vowel.[11] Polish does indeed exploit this strategy, but only if the following vowels contain the element |I|. As a result /k/ and /ɡ/ followed by /i/, /ɨ/ and /ɛ/ are realized as palatals. In the environment of vowels which do not possess the element |I|, velars surface unaltered. This situation is due to the ranking of Spec relative to the ranking of the Dep Link(F)-family constraints as proposed in Torres-Tamarit (2016: 699). In short, Dep Link(F) constraints assign violations to instances of newly established links between particular features and root nodes if a given node and the feature are present in the input. (26) is the formulation of the Dep Link(F) constraint adjusted to the element-based architecture.[12]

| Dep Link |E| – assign violation for every instance of a link which is present in the output but not present in the input, and which connects element |E| with a root node |

| Dep Link |A|; Dep Link |U| > Spec > Dep Link |I|[13] |

Given the ranking (27), elements |A| and |U| do not spread onto velars from the following vowels. That is, sequences such as /ku/, /ɡu/ and /xu/ do not surface as [pu], [bu] and [fu], respectively. Such a spreading would satisfy the constraint Spec, at the cost of the violation of the higher ranked Dep Link |U|. Note also, that the violable nature of Spec allows us to avoid the ban on the word-final velars, wrongly predicted by Gussmann’s analysis, which employed the inviolable Empty Heads constraint. Under the current assumptions, word-final velars are expected to surface as such despite the violation of Spec. At the same time, input sequences such as /ki/, /kɨ/, /kɛ/, are expected to result in the transfer of the element |I|, which violates Dep Link |I| but satisfies Spec.

Nevertheless, the spreading of |I| derives the desired outputs directly only if the input sequence consists of the velar consonant and the front high vowel /i/. This is the case as palatals and the vowel /i/ contain element |I|-head (see 23 and 24 above). (28) illustrates the mapping that gives rise to the palatal stop in the environment of the vowel /i/. The symbol ‘<<<’ represents spreading.

| Place | Place | → | Place | Place | |

| | | | | | | | | ||

| (_) | I | I | <<<<<<<< | I | |

| /k/ | /i/ | [kʲ] | [i] |

On the other hand, the vowel /ɨ/ and /ɛ/ contain element |I| in the status of an operator. Hence, the derivation of the palatalized velars by the spreading of element |I| from /ɨ/ and /ɛ/, must also involve the switch in the headedness status of the element. This switch is the consequence of the interaction of two classes of constraints. The first such class are the inventory constraints presented in (29).

| *{I.ʔ.H}: do not be a segment composed of elements {I.ʔ.H} |

| *{I.ʔ.H.L}: do not be a segment composed of elements {I.ʔ.H.L} |

| *{I.H}: do not be a segment composed of elements {I.H} |

The inventory constraints in (29) are violated by the outputs derived by the spreading of element |I|-operator onto velars. Although inventory constraints seem an ad hoc device, they are the necessary consequence of the assumption that constraints may refer to combinations of elements. In short, the position taken in this work is that it is the absence of inventory constraints such as (29a–c), rather than their presence that requires explanation. The inventory constraints found in (29) are ranked higher than Spec.

Although the ranking of inventory constraints in (29) prevents the spreading of element |I| as an operator, it does not prevent the mapping in which the spreading element plays the role of the head in the target consonant, but retains the status of an operator in the vowel. The unattested mapping of this kind is illustrated in (30).

| Place | Place | → | Place | Place | |

| | | | | | | | | ||

| (_) | I | I | <<<<<<<< | I | |

| /k/ | /ɨ/ | [c] | [ɨ] |

The absence of the sequence [cɨ] in Polish is not an isolated gap but rather follows from the general set of restrictions on the distribution of vowels /i/ and /ɨ/. These restrictions are the consequence of the high ranking of the two constraints presented in (31).

| Agree |I|CV: if a vowel contains a place node marked for element |I|-head the place node of the preceding consonant must also possess element |I|-head |

| Agree Head/Operator |I| (Agr H/O |I|): element |I| cannot play a different head/operator role in the vowel and the preceding consonant |

While constraint (31a) makes sure that the consonants preceding the vowel /i/ are |I|-headed, constraint (31b) rules out the sequences of |I|-headed consonants and /ɨ/. Mapping (30) is ruled out by the high ranking of constraint (31b). The ranking of Agr H/O |I|, the inventory constraints (29) and Spec above Dep Link |I| leads to the convergence of the mapping in (32), where the element |I| found in the vowel switches its headedness status. As a result, the lexical /ɨ/ surfaces as [i].

| Place | Place | → | Place | Place | |

| | | | | | | | | ||

| (_) | I | I | <<<<<<<< | I | |

| /k/ | /ɨ/ | [c] | [i] |

The constraints in (31) have a similar effect to Gussmann’s I-alignment (see 18). However, since constraint Agree |I|CV refers to autosegmental place nodes rather than to segments, the current analysis avoids making the problematic prediction concerning the ungrammaticality of the word-initial /i/, which Gussmann’s (2004, 2007 analysis was forced into. On the assumption that word-initial empty onsets are not equipped with place nodes, the sequence of an empty onset and /i/ simply does not violate (31a) and is not expected to give rise to a word-initial [ji] sequence.

The same set of constraints derives the correct mapping between the sequences of velar stops and the vowel /ɛ/. The element |I| is shared between the vowel and the velar. This satisfies Spec. The inventory constraints and constraint Agr H/O |I| (31b) require the element |I| to be promoted to the status of the head. This results in the derivation of the phonological expression {I.A} realized as the raised [e]. (33) illustrates the relevant mapping.

| Place | Place | → | Place | Place | |

| | | | | | | | | ||

| (_) | I.A | I | <<<<<<< | I.A | |

| /k/ | /ɛ/ | [c] | [e] |

The switch in the headedness status of element |I| leads to the violation of the faithfulness constraint IdentHead |I| (34).

| IdentHead |I|: do not change the head/operator status of element |I| |

The constraint ranking that derives the basic SVP facts is summarized in (35).

| *{I.ʔ.H}; *{I.ʔ.H.L}; *{I.H}; Agree |I|CV; Agr H/O |I| > Spec > IdentHead |I| > Dep Link |I| |

The ranking of IdentHead |I| above Dep Link |I| will be shown to derive SVP in the cases of the concatenation of stems terminating in the velar fricative with the front close vowel /i/.

5.2 The high vowel affix environment

This section discusses the derivations in which velar plosives, the velar spirant and hard and soft anterior consonants find themselves in the environment of affixes composed of vowels /i/ and /ɨ/.

5.2.1 Affixes of foreign origin

In Section 2 we saw that the affixes -ist-/-yst- ‘-ist’, -izm-/-yzm- ‘-ism’ and -ik-/-yk- ‘-ic/-ique’ in Polish may or may not trigger Coronal and Labial Palatalization (see 36).

| ara[bj-i]sta ‘Arabist’ vs. lob[b-ɨ]sta ‘lobbyist’ |

| rekor[d͡ʑ-i]sta ‘record holder’ vs. stypen[d-ɨ]sta ‘scholar’ |

| parok[s-ɨ]zm ‘paroxysm’ vs. mark[ɕ-i]zm ‘Marxism’ |

| hob[b-ɨ]zm ‘having a hobby’ vs. sno[bj-i]zm ‘snobbery’ |

| mu[z-ɨ]ka ‘music’ vs. tech[--i]ka ‘technique’ |

Stems ending in velars, on the other hand, undergo palatalization in the environment of the said affixes without any exceptions.

In order to account for these facts, I will assume that each of the affixes presented above begins with a close high vowel /i/ and that each of them has two allomorphs: one equipped with the floating element |I|-head that linearly precedes the vowel /i/, and one that does not possess such a floating element. The allomorphs of the affixes are presented below.

| -ist/-yst- ‘-ist’ | -izm-/-yzm- ‘-ism’ | -ik-/-yk- ‘-ic/-ique’ |

| /ist/ | /izm/ | /ik/ |

| /I ist/ | /I izm/ | /I ik/ |

According to the findings presented in Czaplicki (2021), the situation in which stems palatalize in the context of the affix -ist/-yst- is more common than the situation in which palatalization is not observed. Let me, therefore, postulate that it is the allomorph /ist/ whose insertion is conditioned, while the allomorph /I ist/ is the default or elsewhere case. According to Gussmann (2007), who refers to Kreja (1989), the palatalization in the environment of the affix -izm-/-yzm- is much less common than in the case of the affix -ist/-yst-. The same is true about the affix -ik-/-yk-. I will, therefore, assume that, in the case of the two latter affixes, the exponents with floating autosegments are the conditioned variants, while the exponents /izm/ and /ik/ are the elsewhere cases. The insertion statements formulated in the spirit of the theory of Distributed Morphology (Embick 2010; Embick and Noyer 2007; Halle and Marantz 1993) are provided below.

| n [+hum, +class X] ↔ | /ist/ / List X = {√stypend, √lobb etc.} __ |

| /I ist/ elsewhere |

| n [+abstract, +class Y] ↔ | /izm / elsewhere |

| /I izm/ List Y = {√ras, √snob etc.} __ |

| n [+ class Z] ↔ | /ik/ / elsewhere |

| /I ik/ List Z = {√techn, √graf etc.} __ |

Since -ist-/-yst- ‘-ist’ is used to create nouns that name humans, I take it to realize the nominal head n marked for the feature [+human]. At the same time, -ist-/-yst- ‘-ist’ is not the only exponent of the feature [+human], so the head it realizes must also be specified for the arbitrary feature [class X]. The exponent /ist/ must be inserted in the environment of a list of roots that includes items such as √stypend, √lobb. The exponent that contains the floating element |I|-head is the elsewhere case. It is inserted after the roots that are not members of LISTX.

The insertion of the allomorphs of the affix -izm-/-yzm- ‘-ism’ (38b) is conditioned in a similar manner. Since the affix in question is not the only realization of abstract nouns in Polish, the reference to [class Y] is necessary. Again, the reference to the list of roots is required, although this time it is the exponent without the floating element that is the default. The insertion of -ik-/-yk- ‘-ic/-ique’ also calls for reference to a specific class, while the environment of the insertion of the exponent with the floating element is defined as LISTZ (38c).

The concatenation of exponents (37a) with stems terminating in hard consonants must result in the retraction of the vowel /i/. This is illustrated by the evaluation in (39).

| stypen/d-i/sta → stypen[dɨ]sta ‘scholar’ |

| sa/d-i/zm → sa[dɨ]zm ‘sadism’ |

| meto/d-i/ka → meto[dɨ]ka ‘methodology’ |

|

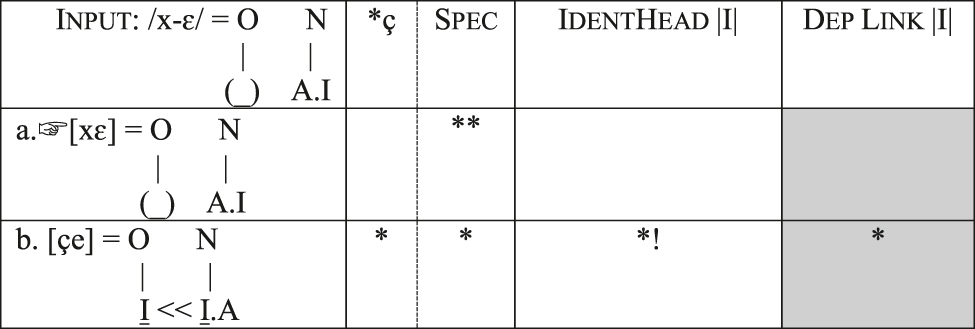

The winning candidates (39b) violate the constraint IdentHead |I|, which penalizes the shift in the headedness of element |I|. Candidates which do not change the headedness status of the element violate constraint Agree |I| CV (see 39a), as the vowel containing element |I|-head follows a consonant that does not contain |I|-head. Candidates that enforce spreading end up with segments with more than one element associated with the place node and are eliminated by Spec (39c).

The analysis of the concatenation of the exponents equipped with the floating element |I| involves the activity of two additional constraints: *Float and NoTauMorDoc (Wolf 2005):

| *Float: assign a violation for any instance of a floating segment found in the output |

| NoTauMorDoc: assign a violation for every instance of a floating autosegment which anchors onto the material which is the exponent of the same morpheme |

In the Containment architecture assumed in this work, *Float ensures that the floating feature is linked since the deletion of the lexical material is not available. (41) summarizes the evaluation.

| rekor/d-I i/sta → rekor[d͡ʑi]sta ‘record holder’ |

| ra/s-I i/zm → ra[ɕi]zm ‘racism’ |

| elekro/n-I i/ka → elektro/ɳi/ka ‘electronics’ |

|

Candidates in (41a) represent a fully faithful mapping, which violates *Float. In candidates (41b), the floating elements dock onto the affix. This results in the violation of NoTauMorDoc. Candidates (41c) win despite the violation of Spec and Dep Link |I|.

The vocabulary items in (38) do not indicate which allomorphs of -ist-/-yst- ‘-ist’, -izm-/-yzm- ‘-ism’ and -ik-/-yk- ‘-ic/-ique’ is found with stems in velars. In fact, however, the concatenation of either of them will produce the correct output: the palatalization of the velar. If the stem terminating in a velar is concatenated with the affix equipped with a floating element, the winning candidate violates only the constraint against the epenthetic linking of element |I| (see 42c).

| psy/x-I i/ka → psy[çi]ka ‘psyche’ |

|

If the allomorph without the floating feature is selected, the evaluation will proceed as in (43).

| czoł/ɡ-i/sta → czoł[ɟi]sta ‘tank driver’ |

| monar/x-i/zm → monar[çi]zm ‘monarchism’ |

|

The faithful candidates (43a) violate Agree |I| CV and Spec. This violation of Agree |I| CV may be avoided by switching the status of the element |I| in the vowel. In surface terms, this would result in vowel retraction (see candidates 43b). Since velars lack place specification, candidates (43b) are eliminated by the fatal violation of Spec. The optimal candidates, (43c), violate only the constraint against the spreading of |I|.

To sum up, under the analysis postulated in this section the palatalization of coronals and labials is possible only if the palatalization is triggered by a floating element. This is illustrated by the evaluations found in (39) and (41), and follows from the ranking of Spec above IdentHead |I| and *Float and NoTauMorDoc above Spec. The palatalization of coronal and labial consonants in the context of the vowel /i/ is blocked by the relative high ranking of Spec, which penalizes the spreading of an element onto place nodes which already carry one element. In the case of velars, the ranking of Spec above Dep Link |I| enforces the spreading of element |I| found in the vowel. This results in Surface Velar Palatalization (see 43).

5.2.2 The context of vowel /ɨ/: the genitive singular

In this section, I demonstrate how the relatively high ranking of the constraint Spec and the relatively low ranking of constraints Dep Link |I| and IdentHead |I| derive the interaction of consonants and the vowel /ɨ/ found in the Genitive singular ending of Polish nouns. The tableau in (44) illustrates the derivation of the Genitive singular of the word ręka /rɛŋka/ ‘arm’.

| rę/k-ɨ/ → rę[ci] ‘arm, gen, sg.’ |

|

Candidate (44b) is suboptimal due to the violation of Spec, while candidate (44c) is eliminated by Agree |I| CV. Candidate (44d), in which element |I|-operator spreads, gives rise to a combination of elements which is unattested in Polish and which is eliminated by the high ranking of the relevant inventory constraint. Candidate (44e) fatally violates Agr H/O |I|: it contains the element |I|, which functions as the head in the consonant and as an operator in the adjacent vowel. The winning candidate involves the transfer of the element |I| which functions as the head in both the vowel and the consonant. This results in the fronting of the vowel and the palatalization of the consonant.

The analysis presented above obviously extends to sequences of the voiced velar plosive /ɡ/ and /ɨ/. Much less desirably, it also extends to instances of the velar spirant. As shown in Section 2, sequences of /x/ and /ɨ/ do not trigger the fronting of /ɨ/ or the palatalization of /x/.

Let me postulate that the exceptional behaviour of the velar spirant is due to the activity of the inventory constraint *ç (‘Do not be a palatal fricative’). The tableau in (45) illustrates the derivation of the Genitive singular of the word mucha ‘fly’.

| mu/x-ɨ/ → mu[xɨ] ‘fly, gen, sg.’ |

|

Based on the assumption that the constraint *ç is ranked together with Spec, the optimal status of the candidates which violate either of them will be decided on the basis of the violation of the lower ranked constraints. Thus, candidate (45b) is suboptimal as it violates the faithfulness constraint against the switch of the headedness status of element |I|. The winner is the faithful candidate (45a).

The faithful mapping is also the optimal one for stems terminating in hard consonants, including labials and dentals. The following tableau illustrates the derivation of the Genitive singular of the noun map-a ‘map’. The faithful candidate (46a) does not violate any of the relevant constraints.

| ma/p-ɨ/ → ma[pɨ] ‘map, gen, sg.’ |

|

Finally, let us consider the application of the relevant ranking to a stem which terminates in a soft consonant. Let us recall that in such cases the Genitive ending is fronted to [i]. It turns out that the proposed constraint ranking is also adequate in such cases provided that it is augmented by a high-ranked constraint which protects the headedness status of elements in consonants (47).

| IdentHead;C: do not change the head/operator status of an element in a consonant |

(48) illustrates the derivation of the Genitive singular of the word nać ‘parsley’ that terminates in a prepalatal affricate headed by element |I|.

| na/t͡ɕ-ɨ/ → na[t͡ɕi] ‘parsley, gen, sg.’ |

|

The faithful candidate (48b) violates constraint Agr H/O |I|, while the candidate which changes the status of the element |I| in the consonant violates IdentHead;C.

In sum, the Genitive singular ending /ɨ/ must be fronted after consonants which possess element |I|-head: underlying soft stems and palatals, the latter of which are derived from velars as a strategy of avoiding the violation of Spec. To account for the exceptional status of /x/, I propose an inventory constraint *ç. In the following section I will show that the presence of constraint *ç does not block the derivation of the palatal spirant before the underlying vowel /i/.

5.2.3 The secondary imperfective affix -iw-/-yw-

As illustrated by the data in (11) and (12) is Section 2.2, the Secondary Imperfective affix triggers the palatalization of velar consonants, but not of coronals and labials. The existing accounts of the behaviour of the SI suffix assumed that it actually contains the vowel /ɨ/. Such accounts were forced to postulate a condition that blocks the rule of /ɨ/-Fronting after /x/ everywhere except before the SI affix (see e.g. Gussmann 1980: 11), or to propose an affix-specific rule that derives the palatalization of velar spirants only before the affix -iw/-yw- (see e.g. Gussmann 1992: 40). On the assumption that the SI affix lexically begins with the close vowel /i/, the current analysis accounts for the behaviour of the SI affix without employing affix-specific rules or conditions.

(49) illustrates the mapping resulting from the concatenation of the stem of the verb poszu/k/-ać ‘look for’, terminating in a voiceless velar plosive, with the Secondary Imperfective affix.

| poszu/k-iv/-ać → poszu[civ]-ać ‘look for, SI’ |

|

As expected, the evaluation results in SVP: the winning candidate (49c) is the one in which element |I|-head is shared between the vowel and the preceding consonant.

(50) illustrates how the same constraint ranking that selected the faithful mapping of the Genitive singular of the noun mucha ‘fly’ in (45) derives the palatalization of the velar spirant in the Secondary Imperfective of the verb zako/x/-ać (się) ‘fall in love’.

| zako/x-iv/-ać → zako[çiv]-ać ‘fall in love, SI’ |

|

Since the vowel in the SI affix lexically contains the element |I|-head, the ranking of constraint IdentHead |I| above constraint Dep Link |I| eliminates the mapping which involves retraction (50b). The candidate (50c), featuring the SVP of the velar fricative /x/, is the optimum.

As anticipated above, the SI affix is another environment which clearly points to a different nature of the interaction of high vowels with velars on the one hand, and coronals and labials on the other. As has already been shown in Section 5.2.1, the constraint ranking assumed in this work correctly derived the retraction of the vowel /i/ in the context of hard anterior consonants. This is confirmed by the evaluation of the SI form of the verb wyga/d/-ać ‘blab’, summarized in (51).

| wyga/d-iv/-ać → wyga[dɨv]-ać ‘talk a lot, SI’ |

|

As noted earlier, the strategy according to which element |I|-head propagates from the vowel to the consonant is promoted in the case of underlying velars, but triggers a violation of Spec in the case of stems with underlying labials and dentals (see candidate (51c) above). It is the violation of the constraint Spec that decides between candidates (51a) and (51c).

A completely analogical evaluation to that in (51) would be postulated for stems with other hard consonants except for those involving complex resonance, i.e. the dental and retroflex affricates /t͡s/, /d͡z/ /t͡ʂ/, /d͡ʐ/, and the retroflex fricatives /ʂ/ and /ʐ/, which contain element |I|-operator (e.g. obie/t͡s-i/w-ać → o-bie[t͡sɨ]w-a-ć ‘promise). In the case of these segments, the high ranking of IdentHead;C (47), which prevents the change in the headedness status of elements in consonants, crucially contributes to the retraction.

To sum up the analysis of the interaction of high vowels with consonants in Polish, due to the relatively low ranking of constraint Dep Link |I| and the relatively high ranking of constraint Spec, velars are expected to be prone to palatalization much more readily than coronals and labials. Moreover, due to the high ranking of constraint Agree |I| CV and the low ranking of constraint IdentHead |I|, hard consonants are expected to provoke the retraction of the front vowel /i/ to /ɨ/ (see (39) and (51) above), while soft, |I|-headed consonants, are expected to provoke the fronting of the vowel /ɨ/ to /i/ (see (48) above). Under the current approach, no affix-specific statements regulating the behaviour of the SI affix -iw-/-yw- are necessary. The affix behaves in a completely regular manner.

5.3 Surface velar palatalization before the vowel /ɛ/

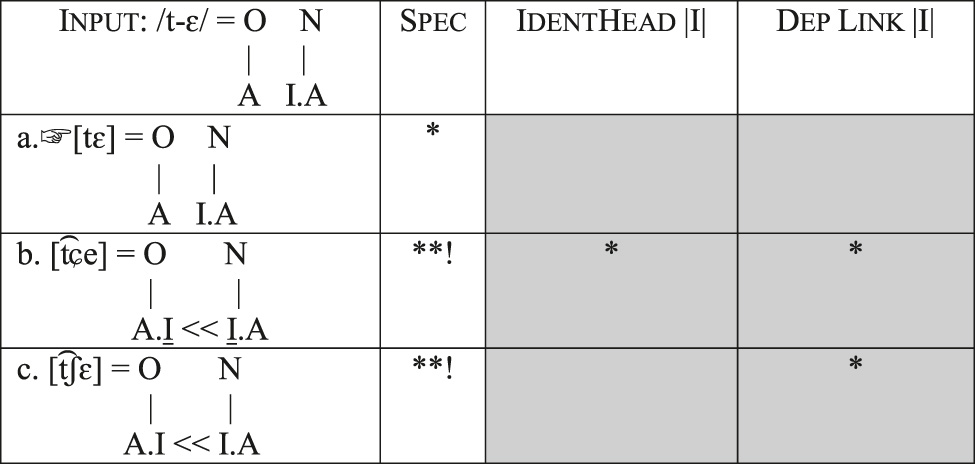

Surface Velar Palatalization affects velar stops before inflectional endings beginning in the front mid vowel /ɛ/. The evaluation of the concatenation of the word rok ‘year’ with the Instrumental singular affix -em /ɛm/ is presented in (52).

| ro/k-ɛm/ → ro[cem] ‘year, instr, sg.’ |

|

The faithful mapping (52a) violates Spec twice, as the consonant has no specification associated with its place node and the vowel has complex resonance. The spreading of the element |I|-operator from the vowel either violates Agr H/O |I| (candidate 52b) or the inventory constraint (52c), depending on whether the spreading element anchors as a head or as an operator. The winner, (52d), involves the promotion of the element |I| to the status of the head and the spreading of the element |I| onto the place node of the velar. This results in /ɛ/ being raised to [e], as well as the palatalization of the velar.

The relevant aspects of the mapping that results from the concatenation of the stem terminating in the velar spirant and the Instrumental singular desinence are summarized in (53).

| du/x-ɛm/ → du[xɛm] ‘ghost, instr, sg.’ |

|

Candidate (53b), which derives palatalization and raising, violates the segment inventory constraint *ç and the faithfulness constraint IdentHead |I|. The winner is the faithful candidate, which violates Spec.

The palatalization of hard coronal and labial consonants before the affix -em /ɛm/ cannot result in palatalization due to the high ranking of Spec. Thus, in the case of the Instrumental singular of stems such as ko/t/ ‘cat’, the faithful mapping is optimal (see 54).

| ko/t-ɛm/ → ko[tɛm] ‘cat, inst, sg.’ |

|

In the case of the stems terminating in |I|-headed consonants, e.g. goś/t͡ɕ/ ‘guest’, the mapping is analogous to the one we saw for stems such as nać ‘parsley’ in (48). The faithful mapping is suboptimal due to the ranking of the consonant Agr H/O |I|, while the headedness status of the elements in the consonants is protected by the high ranking of the constraint IdentHead;C. The optimal mapping involves the raising of the vowel /ɛ/ to [e] (goś/t͡ɕ-ɛm/ → goś[t͡ɕem] ‘guest, instr, sg.’).

Having discussed the mechanisms behind SVP, we are in a position to answer three of the five questions pertaining to the interaction of consonants and front vowels formulated in Section 2.

Concerning questions 1 and 2, i.e. the marked status of velar stops before /ɨ/ and their vulnerability to palatalization, there are two details of the analysis that derive these effects (i) the fact that velars are unspecified for place of articulation and (ii) the high ranking of constraint Spec, which punishes the absence of place specification. The ranking of constraint Spec enforces the spreading of element |I| from the vowel. This results in palatalization. Labials and dentals do not violate Spec and their presence does not warrant any repairs in the environment of /ɨ/. While the spreading of element |I| onto a velar prevents the violation of Spec, the same constraint is violated when an element spreads onto the coronal or the labial, as these segments are lexically specified for place. For, this reason coronals and labials resist palatalization.

Concerning question 4, the immunity of the velar spirant to SVP follows from the high ranking of the inventory constraint *ç. The ranking of *ç together with Spec blocks the palatalization of the velar spirant in an environment in which such a palatalization would require the fronting of the vowel /ɨ/ and raising of the vowel /ɛ/. Both the processes involve the switching of the status of element |I| and provoke the violation of the constraint IdentHead |I|. The palatalization triggered by /i/ does not involve the violation of IdentHead |I| and the velar spirant undergoes SVP.

Unlike Gussmann’s (2007) analysis, the analysis presented above does not require postulating two different phonological representations of the velar fricative. The words such as sza[x-ɨ] ‘chess’ and sza[ç-i]sta ‘chess player’ have the same lexical representation of the velar. The absence of the palatalization in the former versus the presence in the latter follow from the lexical representation of the relevant affixes and the relative ranking of the constraints.

5.4 No SVP before the denasalized vowel /ɛ͂/

SVP does not apply in the context of the affix -ę /ɛ͂/, which realizes the Accusative singular as well as the 1st person singular non-past tense (see 8 as well as 55).

| a. fo/k-ɛ͂/ → fo[kɛ] *fo[ce] ‘seal’ | c. no/ɡ-ɛ͂/ → no[ɡɛ] *no[ɟe] ‘leg’ |

| b. tłu/ k-ɛ͂/ → tłu[kɛ] *tłu[ce] ‘I beat’ | d. mo/ɡ-ɛ͂/ → mo[ɡɛ] *mo[ɟe] ‘I can’ |

Note also that the data in (55) illustrate surface opacity, as the nasal vowel undergoes denasalization in unguarded speech. In traditional approaches (e.g. Laskowski 1975), the opacity is dealt with by ordering the denasalization after the level at which SVP is enforced. Since, in the model employed here, the evaluation is strictly parallel no ordering solution may be postulated. Instead, a representational solution will be pursued.

Under the version of Containment assumed in this work, the denasalization does not result in the deletion of the element responsible for nasality as that would mean removing the piece of the input representation. Instead, denasalization is treated as marking the association line that connects the nasality element with the higher subsegmental structure as phonetically invisible. As a consequence, the nasality element |L|-head is unparsed and phonetically unrealized but, crucially, it is not deleted from the representation. Given that SVP involves the promotion of element |I| to the status of the head, the mapping in which the nasal vowel palatalizes the preceding consonant results in a structure in which the nasality element |L| and the palatality element |I| both play the role of the head. Let me postulate that such a configuration violates constraint *Hydra;V, which penalizes vowels in which more than one element plays the role of the head (see 56).

| *Hydra;V: assign a violation whenever more than one element plays the role of the head in a vowel |

Let us further assume that the relevant version of *Hydra;V is an I-constraint, i.e. it is violated by both the phonetically visible and invisible material. The impact of *Hydra;V on the evaluation of the input in which a stem terminating in a velar stop is concatenated with /ɛ͂/ is illustrated in (57).

| fo/k-ɛ͂/ → fo[kɛ] ‘seal, acc. sg.’ |

|

The optimal candidate is (57a), in which no palatalization takes place. Candidate (57b), in which the element |I| is promoted to the status of the head in the vowel, violates the constraint *Hydra;V, which is ranked higher than Spec. The switching of the status of element |L| to that of the operator is prevented by the high ranking of the constraint IdentHead |L| (see 57c).