Abstract

This paper provides new insights into the analysis of vocative structures that co-occur with a sentence by bridging two previously independent domains of linguistic research: wh-interrogatives and vocatives. More specifically, we investigate in which positions Spanish speakers accept vocatives in wh-interrogatives introduced by different wh-phrases. The results of an acceptability judgment task indicate that our participants highly accept initial and final vocatives in all wh-interrogatives. For middle vocatives, the results differ across wh-phrases. While the participants accept middle vocatives in wh-interrogatives introduced by por qué (‘why’) and d-linked wh-phrases, they reject them in bare wh-interrogatives. These findings require a modification of the syntactic analysis of vocatives. Initial vocatives are placed above ForceP, while middle and final vocatives are analyzed in two different positions, in an upper and a lower VocaddrP in the left periphery.

1 Introduction

This paper contributes to the literature on vocative constructions that co-occur with a sentence and their syntactic analysis. Focusing on Spanish, we explore vocatives that are expressions used to designate the hearer, and the impact that the semantic-pragmatic distinction of vocatives (i.e., calls and addressees: Zwicky 1974) has on the syntax.

The literature on vocatives distinguishes between those that constitute an independent utterance (1a), and others that are part of another utterance (1b). We focus on the latter one here.

| ¡Celia! |

| Celia, | me | dicen | que | te | están | esperando. |

| CeliaVOC | me | tell-3pl | that | you | are-3pl | waiting |

| ‘Celia, they tell me that they are waiting for you.’ | ||||||

Most related studies have analyzed vocative constructions in declaratives. In these clauses, three different positions for vocatives can be identified: initial, middle, and final, as shown in the following examples:

| Celia, | me | dicen | que | te | están | esperando. |

| CeliaVOC | me | tell-3pl | that | you | are-3pl | waiting |

| ‘Celia, they tell me they are waiting for you.’ | ||||||

| Me | dicen, | Celia, | que | te | están | esperando. |

| me | tell-3pl | CeliaVOC | that | you | are-3pl | waiting |

| ‘They tell me they are waiting for you, Celia.’ | ||||||

| Me | dicen | que | te | están | esperando, | Celia. |

| me | tell-3pl | that | you | are-3pl | waiting | CeliaVOC |

| ‘They tell me they are waiting for you, Celia.’ | ||||||

To the best of our knowledge, there is no research on vocatives co-occurring with wh-interrogatives. We believe that this combination provides interesting new insights into the syntactic analysis of vocatives. Before we examine possible vocative positions in wh-interrogatives, we describe some basic characteristics of vocatives and Spanish wh-interrogatives in Section 2 and Section 3. Sections 4 and 5 present the methodology and the results of our acceptability judgment task that we discuss in Section 6. In Section 7, we propose a new syntactic analysis within the cartographic framework that reflects the properties of both wh-interrogatives and vocatives. Finally, Section 8 draws some conclusions and highlights paths for future research.

2 Classification of vocatives

The term vocative comes from the Latin noun vocatīvus which is derived from the verb vocare. The literal meaning of vocare is ‘to invoke, call, name a person or thing personified’ (Brandimonte 2011: 251; our translation). A lot of research has emerged to define vocatives. The Real Academia Española (RAE) propose the following:

[C]onstituyen EXPRESIONES VOCATIVAS los nombres, los pronombres y los grupos nominales que se usan para llamar a las personas o animales (¡Eh, tú!; ¡Papá!, ¿me oís?; Lucera, ven acá), para iniciar un intercambio verbal o para dirigir a alguien un saludo (¡Hola, Clara!), una pregunta (¿Está cansado, don Marcelo?), una petición o una orden (Márchate, niña), una advertencia (Manuel, ten cuidado), una disculpa (Lo siento, caballero), etc. (RAE/ASALE 2009: §32.2g).[1]

Therefore, we use the term vocative to describe nominal expressions that assign the addressee. Vocatives have been characterized from different perspectives: (i) morpho-syntactic perspective (i.e., class of words and phrases, positional mobility), (ii) semantic-pragmatic perspective (i.e., meaning, primordial functions, speaker-listener relationship), and (iii) phonological perspective (i.e., intonation). Concerning the morpho-syntactic perspective, vocatives can appear in three different positions (see [3]), namely: initial, middle, and final (Espinal 2013; Hill 2007, 2013b; Stavrou 2014; Zwicky 1974). These three positions are the topic of our paper.

| a. | Celia, me dicen que te están esperando. |

| b. | Me dicen, Celia, que te están esperando. |

| c. | Me dicen que te están esperando, Celia. |

| ‘(Celia,) they tell me they are waiting for you, (Celia).’ |

Regarding the semantic-pragmatic perspective, vocatives have different functions depending on their positions. According to Zwicky (1974), initial vocatives (3a) are used to attract the attention of the interlocutor (call function), while middle (3b) and final vocatives (3c) maintain the contact between speaker and listener (addressee function). Consequently, middle and final vocatives have the same basic semantic-pragmatic function. However, they differ with respect to the context in which they are used. Middle vocatives are used to express politeness and occur therefore more often in formal speech, while final vocatives are more frequent in informal speech, as shown by Edeso Natalías (2005) and Kleinknecht (2019).

With respect to the phonological perspective, vocatives have their own intonation, regardless of their position or their semantic-pragmatic function. They are interpreted as independent intonation phrases (I). Put differently, their intonation is independent from other constituents or intonational phrases of the utterance (U) (Prieto and Roseano 2010). Their phonic properties are also essential to distinguish them from other elements, such as subjects. In contrast to vocatives, the intonation of the subject is determined by the utterance (Prieto and Roseano 2010):

| [ | [ | Celia | dice | la | verdad | ]I | ]U |

| Celia | tells | the | truth | ||||

| ‘Celia tells the truth.’ | |||||||

| [ | [ | Celia,]I | [di | la | verdad | ]I | ]U |

| CeliaVOC | tell | the | truth | ||||

| ‘Celia, tell the truth.’ | |||||||

3 Word order in wh-interrogatives

In contrast to Spanish declaratives, the word order in wh-interrogatives is fairly restricted (e.g., Francom 2012). The wh-phrase is fronted to the sentence-initial position. This, in turn, triggers the reordering of the verb and an overt subject if it is not identical to the wh-phrase. This phenomenon is known as subject-verb inversion, or inversion, and occurs obligatorily in wh-interrogatives (5a). Therefore, preverbal subjects lead to ungrammaticality (5b) (Barbosa 2001; Dumitrescu 2016; Torrego 1984).

| ¿Qué | compró | Juan | en | el | supermercado? |

| what | bought | Juan | in | the | supermarket |

| ‘What did Juan buy in the supermarket?’ | |||||

| *¿Qué | Juan | compró | en | el | supermercado? |

| what | Juan | bought | in | the | supermarket |

| ‘What did Juan buy in the supermarket?’ | |||||

However, subject-verb inversion is not always obligatory in wh-interrogatives. For Peninsular Spanish, there are at least two cases in which subjects can occupy the preverbal and postverbal position. The first exception concerns causal wh-phrases, such as por qué (‘why’), as already noticed by Torrego (1984) and Suñer (1994):

| ¿Por qué | Juan | quiere | salir | antes? |

| why | Juan | wants | leave | earlier |

| ¿Por qué | quiere | Juan | salir | antes? |

| why | wants | Juan | leave | earlier |

| ‘Why does John want to leave earlier?’ | ||||

| (Torrego 1984: 106) | ||||

Empirical work on this topic confirms this finding and shows that por qué (‘why’) is highly accepted with both preverbal and postverbal subjects (Adli 2010; Goodall 2004; Schmid et al. 2021):

| ¿Por qué | prepara | esta | profesora | el | material | para | la | |||

| why | prepares | this | teacher | the | material | for | the | |||

| clase | de | Matemáticas? | ||||||||

| class | of | Math | ||||||||

| ‘Why does this teacher prepare the lesson material for the Math class?’ | ||||||||||

| ¿Por qué | esta | profesora | prepara | el | material | para | la | |||

| why | this | teacher | prepares | the | material | for | the | |||

| clase | de | Matemáticas? | ||||||||

| class | of | Math | ||||||||

| ‘Why does this teacher prepare the lesson material for the Math class?’ | ||||||||||

| (Kaiser et al. 2019: 79) | ||||||||||

The second exception concerns complex or so-called d-linked wh-phrases (Contreras 1999; Fabregas and Mendívil 2013; Francom 2012; Goodall 2005; Martín 2003). D-linked wh-phrases refer to a set of referents that are familiar from the discourse context. They also allow subjects to occur in the preverbal position:

| ¿A | cuál | de | estas | chicas | María | conoció | en | París? |

| prep | which | of | these | girls | María | met | in | Paris |

| ‘Which of these girls did María meet in Paris?’ | ||||||||

| (Francom 2012: 539) | ||||||||

In addition to preverbal subjects that can occur between the wh-phrase and the verb, other constituents, such as complements (9a), can also intervene between the wh-phrase and the verb in wh-interrogatives introduced by por qué (‘why’) or d-linked wh-phrases (Goodall 1993; Martín 2003; Suñer 1994). This does not apply to interrogatives with argumental wh-phrases (9b).[2]

| ¿Por qué | a | su | padre | le | regaló | ese | libro? |

| why | prep | his | father | him | gave-3sg | this | book |

| ‘Why did he give his father that book?’ | |||||||

| *¿Qué | a | su | padre | le | regaló? |

| what | prep | his | father | him | gave-3sg |

| ‘What did he give his father?’ | |||||

In sum, related literature has shown that in contrast to bare wh-interrogatives, interrogatives introduced by ‘why’ and d-linked wh-elements allow subjects and complements to intervene between the wh-element and the verb, suggesting that the same difference can be observed for middle vocatives. To date, no study has investigated whether vocatives underly the same restrictions as subjects in wh-interrogatives or if they can appear in the initial, middle, and final position, as in declaratives (see [3]). We will fill this gap by answering the following research questions (RQs):

In which position are vocatives accepted in wh-interrogatives? (RQ1)

Do d-linked wh-phrases and por qué (‘why’) pose less restriction on the middle positions of vocatives than bare wh-elements? (RQ2)

Which position(s) do initial, middle, and final vocatives occupy in the left periphery? (RQ3)

4 Methodology

We conducted a web-based acceptability judgment task to investigate the positions in which vocatives are accepted and whether wh-phrases like por qué (‘why’) and d-linked wh-phrases pose less restriction on the position of vocatives than bare wh-elements (RQ1 and RQ2).

4.1 Materials

The task was based on a 3 × 3 factorial design and consisted of 36 items, resulting in nine conditions for each item and 324 experimental stimuli. The two independent variables were wh-phrase and vocative position. For the wh-phrase variable, we selected three levels (wh-phrases) based on previous findings in literature. On the one hand, we included por qué (‘why’) and d-linked wh-phrases which allow for intervening subjects and complements, as mentioned above. On the other hand, for the sake of comparison, we used the typical argumental wh-phrase qué (‘what’). In wh-interrogatives introduced by qué, intervening subjects are not possible. The independent variable vocative position also contains three levels: initial (at the beginning of the interrogative), middle (intervening between the wh-phrase and the verb), and final (at the end of the interrogative). Both factors were manipulated within items and within participants. As illustrated in Table 1, all 36 items were introduced by a brief context and consisted of transitive verbs, the subject, and the complement. In the case of wh-interrogatives introduced by qué, we added an adjunct with additional information to control for the length of stimulus, such as en el texto (‘in the text’).

Example of a test items.

| vocative position | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| wh-phrase | inital | middle | final |

|

|

|||

| por qué (‘why’) | Los alumnos de tercero de la ESO tienen que señalar los párrafos más importantes en el texto de México. Cuando Natalia presenta sus resultados, la profesora le pregunta: ‘The third-year students in ESO have to mark the most important paragraphs in the text about Mexico. When Natalia presents her results, the teacher asks her:’ |

||

| Natalia, ¿por qué has señalado este párrafo? | ¿Por qué, Natalia, has señalado este párrafo? | ¿Por qué has señalado este párrafo, Natalia? | |

| ‘(Natalia), why did you mark this paragraph, (Natalia)?’ | |||

| d-linked | Los alumnos de tercero de la ESO tienen que señalar las clases de palabras en distintos colores: verbos en rojo, sustantivos en verde, adjetivos en azul. Cuando han terminado este ejercicio, la profesora le pregunta a Natalia: ‘The third-year students in ESO have to mark the word classes in different colors: verbs in red, nouns in green, adjectives in blue. When they have finished this exercise, the teacher asks Natalia:’ |

||

| Natalia, ¿con qué color has señalado la palabra “correr”? | ¿Con qué color, Natalia, has señalado la palabra “correr”? | ¿Con qué color has señalado la palabra “correr”, Natalia? | |

| ‘(Natalia), what color did you mark the word “run” with, (Natalia)?’ | |||

| qué (‘what’) | Los alumnos de tercero de la ESO tienen que señalar los párrafos más importantes en el texto de México. Cuando Natalia presenta sus resultados, la profesora le pregunta: ‘The third-year students in ESO have to mark the most important paragraphs in the text about Mexico. When Natalia presents her results, the teacher asks her:’ |

||

| Natalia, ¿qué has señalado en el texto? | ¿Qué, Natalia, has señalado en el texto? | ¿Qué has señalado en el texto, Natalia? | |

| ‘(Natalia), what did you mark in the text, (Natalia)?’ | |||

The experiment is based on the Latin square design, thus we created nine lists so that each participant saw only one of the nine conditions. Each participant was asked to judge four sentences per condition. The test sentences were presented along with 36 fillers. The fillers included polar questions as well as imperatives which also vary in the position of vocatives. In order to control the participants’ attention during the experiment, we used four ungrammatical filler sentences. If more than two of them were rated higher than 4 on the scale, the participant was excluded. This did not apply to any of the participants.

4.2 Participants and procedure

56 speakers from Central Spain (Madrid and Castilla-La Mancha) took part in the experiment. The participants (mean age = 28.3, range = 20–57, 40 female, 16 male) were recruited in universities in Madrid and Ciudad Real. All of them are native speakers of Spanish and participated on a voluntary basis. We did not inform them about the purpose of the study. The participants were well educated since 55 completed high school or had higher education.

The experiment was set up on the online platform SoSci Survey. At the beginning of the task, the participants were asked to rate on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = unnatural [Sp. extraño], 7 = natural [Sp. natural]) and to judge how natural the different questions sounded to them. After this short introduction, the participants completed three practice items. Two of the practice items were constructed identical to the test stimuli, and one similar to the fillers. For each stimulus, participants read a brief context before they listened to the questions which were presented orally.[3] They received instructions to use headphones during the whole experiment to avoid disturbances and to ensure uniform sound quality. During the task, we presented the experimental stimuli in pseudo-randomized order combined with the filler sentences. The last part of the experiment consisted of a background questionnaire with sociolinguistic information. The experiment lasted 25 min on average.

4.3 Statistical analysis

In our study, we elicited ordinal data on a 7-point Likert scale. A challenge when using ordinal ratings is that the underlying scale might not be linear. To address this issue, we followed Baayen and Divjak (2017) and used a Generalized Additive Mixed Model (GAMM, e.g., Baayen and Linke 2019; Wood 2006) which is included in the R package mgcv (Wood 2006). We defined rating as the dependent variable which consisted of discrete values from 1 (unnatural) to 7 (natural). The wh-phrase and the vocative position were the two independent variables of main interest. The statistical model included interaction terms between the wh-phrase and the vocative position, and random effects for participant and item.

5 Results

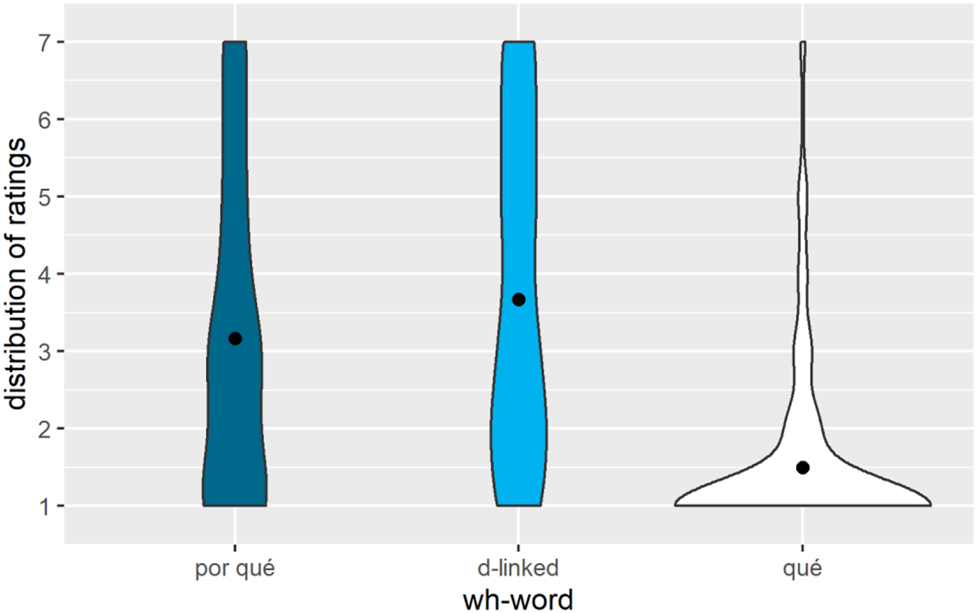

Figure 1 summarizes the results of the acceptability judgment task and plots the mean ratings of the three vocative positions (initial, middle, and final) across the wh-phrases (por qué [‘why’], d-linked wh-phrases and qué [‘what’]). The results suggest that participants, on average, show the highest ratings for the initial vocative position, followed by ratings for the final vocative position. We also observe that these two positions receive similar ratings for all three wh-phrases. The middle vocative position, overall, receives the lowest ratings but shows a remarkably great difference in ratings across the wh-phrases. For por qué (‘why’) and d-linked wh-phrases, participants have higher ratings, and they seem to accept (at least marginally) the middle vocative position. By contrast, for interrogatives with qué (‘what’), this position shows extremely low ratings.

Mean ratings for vocative positions (initial, middle, and final) across wh-phrases with 95% confidence intervals.

We ran a generalized additive mixed model to test which vocative positions participants accept in wh-interrogatives (RQ1) and whether d-linked wh-phrases and por qué (‘why’) pose less restriction on the middle positions of vocatives than bare wh-elements (RQ2). Due to a significant interaction between vocative position and wh-phrase, we could not assess the effect of the two variables and thus calculated a separate generalized additive mixed model for vocative position in combination with each wh-phrase and for wh-phrase in combination with each vocative position. For initial vocatives, we did not observe a difference between the three wh-phrases: wh-interrogatives with d-linked wh-phrases (β = 0.12, SE = 0.21, z = 0.60, p = 0.55) and qué (‘what’) (β = 0.22, SE = 0.21, z = 1.10, p = 0.27) did not differ significantly from those introduced by por qué (‘why’).

The ratings for final vocatives were significantly lower for all wh-phrases (d-linked: β = −1.04, SE = 0.19, z = −5.42, p < 0.001; por qué (‘why’): β = −0.83, SE = 0.19, z = −4.39, p < 0.001; qué (‘what’): β = −0.80, SE = 0.20, z = −4.07, p < 0.001), but did not significantly differ between wh-phrases. Neither wh-interrogatives introduced by d-linked wh-phrases (β = −0.08, SE = 0.17, z = −0.44, p = 0.66) nor by qué (‘what’) (β = 0.26, SE = 0.18, z = 1.43, p = 0.15) deviated significantly from those with por qué (‘why’). This implies that the differences were driven by vocative position and not by wh-phrase.

In the last step, we focused on the middle vocative position. This position also differs significantly from the initial position for all wh-phrases (d-linked: β = −2.83, SE = 0.19, z = −15.00, p < 0.001; por qué (‘why’): β = −3.07, SE = 0.18, z = −16.72, p < 0.001; qué (‘what’): β = −5.60, SE = 0.22, z = −25.73, p < 0.001). For middle vocatives, we also found an effect of wh-phrase. We observe significantly higher ratings for wh-interrogatives with d-linked wh-phrases than for wh-interrogatives with por qué (‘why’) (β = 0.44, SE = 0.16, z = 2.63, p < 0.001). For wh-interrogatives introduced by qué (‘what’), we observe significantly lower ratings (β = −2.21, SE = 0.20, z = −11.20, p < 0.01). This suggests that the differences were not only driven by the vocative position, but also by the wh-phrase, especially by qué (‘what’) (see Figure 1).

6 Discussion

The first research question dealt with the positions that vocatives occupy in wh-interrogatives (RQ1). For the initial and final vocative position, we found a high level of acceptability over all wh-elements. Although the ratings for the final vocative position were significantly lower than for the initial vocatives, the ratings differed only slightly between the two positions. These results indicate that Spanish speakers fully accept vocatives in the initial position, directly before the wh-phrase, as well as in the final position if they occur remotely from the wh-element at the right end of the clause. These results are consistent with literature on vocatives in declaratives, showing that the availability of these two positions in combination with declaratives depends on the intention of the interlocutor, and consequently on the semantic-pragmatic properties of the vocative, as outlined in Section 2.

For a closer analysis of the middle vocative position in wh-interrogatives, i.e., vocatives directly to the right of the wh-phrase, we turn to RQ2. This research question dealt with whether d-linked wh-phrases and por qué (‘why’) pose less restriction on the middle position of vocatives than other wh-elements like qué (‘what’). On average, we found the lowest ratings for middle vocatives in combination with all wh-elements. However, this does not mean that they are unacceptable at all. For por qué (‘why’) and d-linked wh-phrases, middle vocatives obtained mean ratings between 3 and 4, i.e., they seem to be accepted (at least marginally). These comparably lower ratings for middle vocatives are consistent with the results of Kleinknecht’s (2019) corpus study which show an increasing use of middle vocatives in formal speech. However, our items only contain informal situations for which final vocatives are more frequent. In interrogatives with qué (‘what’), middle vocatives received a mean rating of about 1. The violin plot in Figure 2 further confirms these findings since it shows the distribution of the ratings for the middle vocatives in wh-interrogatives introduced by por qué (‘why’), d-linked wh-phrases, and qué (‘what’). For the wh-element qué (‘what’), we did not find much variation. The shape of the graph reveals that besides a few outliers, participants did not accept middle vocatives in this context. However, for por qué (‘why’) and d-linked wh-phrases the silhouette of the plots shows that at least some participants highly accepted middle vocatives.

Distribution of the ratings for the middle vocatives in wh-interrogatives introduced by por qué (‘why’), d-linked wh-phrases, and qué (‘what’).

Taken together, the results for interrogatives with por qué (‘why’) and d-linked wh-phrases clearly differ from those of qué (‘what’).[4] We can conclude that middle vocatives are only ungrammatical in wh-interrogatives introduced by qué (‘what’) and other bare wh-elements, while they are (at least marginally) acceptable in interrogatives introduced by por qué (‘why’) and d-linked wh-phrases:

| *¿Qué, | Natalia, | has | señalado | en | el | texto? |

| what | Nataliavoc | have-2sg | marked | in | the | text |

| ‘What did you mark in the text, Natalia?’ | ||||||

| ¿Por qué, | Natalia, | has | señalado | este | párrafo? |

| why | Natalia voc | have-2sg | marked | this | paragraph |

| ‘Why, Natalia, did you mark this paragraph?’ | |||||

| ¿Con | qué | color, | Natalia, | has | señalado | la | palabra | “correr”? |

| with | what | color | Natalia voc | have-2sg | marked | the | word | run |

| ‘With what color, Natalia, did you mark the word “run”?’ | ||||||||

A similar behavior as for middle vocatives was observed by Cognola and Cruschina (2021) for the use of the particle poi ‘lit. then’ (as a discourse marker) in Italian. Poi in middle position is restricted to interrogatives with perché ‘why’ and is excluded in other wh-interrogatives. For Spanish, we assume the same distribution of the particles pues and entonces (lit. ‘then’) in middle position as we found for middle vocatives. While they can intervene between por qué (‘why’)/d-linked wh-phrases and the verb, they are excluded in middle position in wh-interrogatives with qué (‘what’):[5]

| *¿Qué, | pues | has | hecho | en | el | jardín? | |

| what | part | have-2sg | done | in | the | garden | |

| ‘What have you done in the garden?’ | |||||||

| ¿Por qué, | entonces, | no | buscas | otro | trabajo? |

| why | part | not | find-2sg | another | job |

| ‘Why don’t you search another job?’ | |||||

| Esposito (2021) | |||||

| ¿Con | qué | color, | entonces, | has | señalado | esta | palabra? |

| with | which | color | part | have-2sg | marked | this | word |

| ‘With which color have you marked this word?’ | |||||||

In sum, our results indicate that the occurrence of middle vocatives in interrogatives introduced by d-linked wh-phrases and por qué (‘why’) is less restricted than in interrogatives with other wh-elements like qué (‘what’). In the former group, vocatives can intervene between the wh-phrase and verb, like subjects do, as shown in Section 3. In contrast, interrogatives introduced by qué (‘what’) or other bare wh-phrases do not allow any of these elements to intervene between the wh-word and the verb.

7 Syntactic analysis

7.1 Previous analysis of vocatives within the cartographic framework

In this section, we summarize previous studies that examine the syntactic distribution of vocatives in (declarative) sentences. The vast majority of scholars (Espinal 2013; González López 2019; Hill 2013b; Moro 2003; Slocum 2016) agree that vocatives are situated in the left periphery because of their independent intonation, among other reasons.[6] However, the question still remains as to the position(s) in which they are located in the left periphery.

Basically, we follow Moro (2003), among others, who assume that vocatives project their own phrase: Vocative Phrase (hereinafter: VocP) (see also Espinal 2013; Hill 2007, 2013b; Slocum 2010, 2016; Stavrou 2009, 2014, a.o.). Based on this assumption, different syntactic analyses have been proposed in previous literature. Most of them are based on a cartographic approach (e.g., Rizzi 1997). For example, both Hill (2013a, 2013b) and Moro (2003) assume that vocatives are located above ForceP,[7] while González López (2019), based on Slocum (2010, 2016 for English), proposes two possible vocative positions depending on their semantic-pragmatic function: one phrase for initial vocatives (calls) and another phrase for middle and final vocatives (addressees). The former is placed above ForceP:

| Celia, | me | dicen | que | te | están | esperando. |

| CeliaVOC | me | tell-3pl | that | you | are-3pl | waiting |

| ‘Celia, they tell me they are waiting for you.’ | ||||||

| [Voc(call)P Voccallº Celia [ForceP Forceº [TopP* Topº* [FocP Focº [TopP* Topº* [FinP Finº]]]]]] |

Addressees (i.e., middle and final vocatives) have a different behavior. In contrast to initial vocatives (calls), addressees can follow the topicalized elements in Spanish (González López 2019: 322; see [13a]). Topics preceding an addressee are also found in English (Slocum 2016: 98), as illustrated in (13b), and Greek (Stavrou 2014: 324), as shown in (13c).

| (AnaCall,) esos ejerciciosTop | (AnaAddr,) los puedes encontrar en cualquier libro. | ||||||||

| AnaVOC these exercices | AnaVOC it-PL can-2SG find in any book | ||||||||

| ‘Ana, you can find them in any book.’ | |||||||||

| (BoysCall,) | the | ballTop (, boysAddr ,) (…) | protect | it with your life |

| (Maria Call,) | tin | Eleni Top | (, MariaAddr,) | tha | ti | dis | avrio. |

| MariaVOC | the | Elena | MariaVOC | will | her | see-2SG | tomorrow |

| ‘Maria, you will see Elena tomorrow.’ | |||||||

Hence, González López (2019) and Slocum (2010, 2016 assume that addressees occur in a separate VocaddrP:

| [ForceP Forceº [TopP* Topº* [Voc(addr)P Voc addr ° [FocP Focº [TopP* Topº* [FinP Finº]]]]]] |

The VocaddrP is situated between the highest TopP and the FocP because of two reasons. First, addressees to the left of the focused material are perfectly accepted (see [15a]), while they are only marginally acceptable to the right of focused phrases if a long pause intervenes (see (15b)[8]) (Ashdowne 2002; Slocum 2016: 97).

| Me | dicen, | Celia, | que | te | gusta | la | nataFoc, | no | el | chocolate. |

| me | tell-3pl | Celia voc | that | you | like | the | cream | not | the | chocolate |

| ‘They told me, Celia, that you like cream, not chocolate.’ | ||||||||||

| ?Es | la | nataFoc, | Celia, | lo que | te | gusta, | no | el | chocolate. |

| is-3sg | the | cream | Celia voc | that | you | like | not | the | chocolate |

| ‘It’s cream, Celia, that you like, not chocolate.’ | |||||||||

Second, middle vocatives can be used to underline the semantic meaning of a sentence by marking the edge of the focus domain, as shown in (16). The subject I that is located to the left of the addressee expresses a contrastive topic or background, while the part to the right is new information, as shown in the following example (Slocum 2016: 106; Taglicht 1984):

| Jessica: | I think we should stay in tonight. |

| Paul: | I, Jessica, want to go to a movie. |

| (Slocum 2016: 106) | |

In sum, previous studies on the syntactic distribution of vocatives suggest two different positions for vocatives in the left periphery. Initial vocatives (calls) occur in the VoccallP above ForceP, while middle and final vocatives (addressees) are in VocaddrP between TopP and FocP:

| [ Voc(call)P Voc call ° [ForceP [TopP* [ Voc(addr)P Voc addr ° [FocP [TopP* [FinP]]]]]]] |

7.2 Our analysis

The results presented in Section 5 as well as previous work on vocatives and wh-interrogatives raise the question of the position(s) initial, middle, and final vocatives occupy in the left periphery (RQ3). Since our results particularly provide new insights for middle and final vocatives, we organize this section as follows.

First, in Section 7.2.1, we relate our results on initial vocatives to previous findings of vocatives and wh-interrogatives. Second, in Section 7.2.2, we focus on middle vocatives and account for the asymmetry between wh-interrogatives introduced by bare wh-elements on the one side, and wh-interrogatives introduced by ‘why’ and d-linked wh-elements on the other. Finally, in Section 7.2.3, we consider the position of final vocatives in the left periphery. As shown in the previous section, related studies focus on the properties of initial and middle vocatives. Therefore, the position of final vocatives is usually linked to middle vocatives. It is true that an analysis that includes only one single VocaddrP for middle and final vocatives is appropriate with respect to the economical aspect of language. Nevertheless, the results of our experiment cast doubt over the assumption of one single VocaddrP for both middle and final vocatives. For our line of argument in this chapter, we include the results from our acceptability judgment task as well as other examples that are attested by different speakers of Peninsular Spanish.

7.2.1 Initial vocatives in the left periphery

As we have pointed out in Section 7.1, related literature agrees that the initial vocatives (i.e., calls) are located above ForceP:

| [Voc(call)P Voc call ° [ForceP Forceº [TopP* Topº* [FocP Focº [TopP* Topº* [FinP Finº]]]]]] |

The results of our acceptability judgment task confirm this analysis since initial vocatives are compatible with all kinds of wh-elements, namely bare wh-elements such as qué (‘what’), por qué (‘why’), and d-linked wh-phrases. Although these three types of wh-phrases occupy different positions in the left periphery, all are located below VoccallP. First, qué and other bare wh-elements are moved to the left periphery (Goodall 1993; López 2013; Rizzi 1996; Suñer 1994), more precisely to [Spec, Foc] within the cartographic framework (Rizzi 1997, 2006), to check the [+WH] feature (López 2009):

| [ForceP [TopP [IntP [TopP [FocP qué [TopP [FinP …]]]]]]] |

Rizzi justifies this assumption by showing the incompatibility of bare wh-phrases with other focal elements (see [20]). Put differently, a bare wh-phrase and a fronted contrastive focus are in complementary distribution.

| *¿Qué | a | Mario | le | deberíamos | decir | (, | y | no | a | Juan)? |

| what | prep | Mario | him | should-1pl | say | and | not | prep | Juan | |

| ‘What should we say to Mario and not to Juan?’ | ||||||||||

Rizzi’s (1997) assumption on the position of bare wh-phrases is compatible with previous analyses of initial vocatives (Espinal 2013; González López 2019; Moro 2003). We assume González López’s (2019) analysis for initial vocative and suggest that the VoccallP occurs above these wh-phrases:

| Antonio, | ¿qué | compraste | en | el | supermercado? |

| Antonio voc | what | bought-2SG | at | the | supermarket |

| ‘Antonio, what did you buy at the supermarket?’ | |||||

| [Voc(call)P Antonio [ForceP [TopP [IntP [TopP [FocP qué [TopP [FinP …]]]]]]]] |

Second, por qué (‘why’) is proposed to be directly merged in IntP in the left periphery (e.g., Rizzi 1996, 2001; Stepanov and Tsai 2008; Thornton 2008) or in a position very close to the articulated CP (Shlonsky and Soare 2011). In Section 3, we provided first evidence for this claim by showing that por qué (‘why’) allows preverbal subjects and complements to intervene between the wh-phrase and the verb, while the other bare wh-phrases do not:

| ¿Por qué | Juan | compró | un | coche | nuevo? |

| why | Juan | bought | a | car | new |

| ‘Why did Juan buy a new car?’ | |||||

| *¿Qué | Juan | compró | en | el | supermercado? |

| what | Juan | bought | in | the | supermarket |

| ‘What did Juan buy in the supermarket?’ | |||||

Another argument in favor of a distinct and higher position of ‘why’ comes from the fact that ‘why’ can co-occur with focus in a fixed order. The focal element can only follow the wh-phrase but cannot precede it (Rizzi 2001: 294):

| Perché | QUESTO | avremmo | dovuto | dirgli, | non | qualcos’altro? |

| why | this | have-1pl | should | say-him | not | something-else |

| ‘Why should we have said this to him, not something else?’ | ||||||

| *QUESTO | perché | avremmo | dovuto | dirgli, | non | qualcos’altro? |

| this | why | have-1pl | should | say-him | not | something-else |

| ‘This why should we have said this to him, not something else?’ | ||||||

Such focal elements interact differently with ‘why’-interrogatives than with bare wh-interrogatives (compare [24] and [25]). In ‘why’-interrogatives, the shift of focus to another constituent requires a different answer, while this is not the case for other wh-interrogatives. The questions in (25) can be answered in the same way, regardless of the focus value.

| Why did Adam eat the APPLE? – Because it (the apple) was the only food around. |

| Why did Adam EAT the apple? – Because he couldn’t think of anything else to do with it. |

| When did Adam eat the APPLE? – At 4 p.m. on July 7. |

| When did Adam EAT the apple? – At 4 p.m. on July 7. |

The analysis of a separate position for ‘why’ (Rizzi 2001) is compatible with the analysis on initial vocatives presented in (18), as can be seen in the following example:

| Antonio, | ¿por qué | has | comprado | el | champú | más | caro? |

| Antonio voc | why | have-2SG | bought | the | shampoo | most | expensive |

| ‘Antonio, why did you buy the most expensive shampoo?’ | |||||||

| [Voc(call)P Antonio [ForceP [TopP [IntP por qué [TopP [FocP [TopP [FinP …]]]]]]]] |

Third, as we have shown in Section 3, d-linked wh-phrases also differ from other bare wh-elements and allow preverbal subjects to intervene between the wh-phrase and the verb. To account for this exception, Rizzi (2006) argues that d-linked wh-phrases have a different landing site from other bare wh-elements. More specifically, he assumes that d-linked wh-phrases target a topic position because they can be characterized in the same way as topics (Grewendorf 2002). Both d-linked wh-phrases and topics refer to a referent that is already introduced in the discourse content. However, a simple topic position cannot attract a wh-phrase. Therefore, Rizzi (2006) supposes that this topic position is also endowed with a Q feature as IntQ moves to the higher Top and creates a complex head. This movement converts the topic position into a landing site for d-linked wh-phrases, as shown in the following representation:[9]

| [ForceP [TopP d-linked wh-phrases IntQ+Top [IntP tInt … [FinP …]]]] |

If Rizzi’s (2006) analysis is on the right track, d-linked wh-phrases and previous analyses for initial vocatives are compatible:

| Antonio, | ¿de | qué | marca | has | comprado | el | champú? |

| Antonio voc | from | what | brand | have-2SG | bought | the | shampoo |

| ‘What brand did you buy the shampoo from?’ | |||||||

| [Voc(call)P Antonio [ForceP [TopP de qué marca [IntP [TopP [FocP [TopP [FinP …]]]]]]]] |

To sum up, the syntactic account for initial vocatives is compatible with previous analyses for all three types of wh-phrases regardless of the position they occupy in the left periphery. However, these different positions become crucial for the analysis of middle vocatives, as will be shown in the following section.

7.2.2 An approach to middle vocatives in the left periphery

The results of our acceptability judgment task have shown an asymmetry between wh-interrogatives introduced by bare wh-elements and wh-interrogatives with ‘why’ and d-linked wh-phrases. While middle vocatives are not acceptable in wh-interrogatives with bare wh-elements, they are acceptable (at least marginally) in those introduced by ‘why’ and d-linked wh-phrases. In this section, we present an analysis based on Slocum (2016) and Rizzi (2001, 2006 that accounts for this asymmetry.

Remember that González López (2019) and Slocum (2016) propose an analysis for middle vocatives in declaratives, as shown in (29). They suggest a different position, namely VocaddrP, which differs from the position of initial vocatives due to their diverging semantic-pragmatic characteristics. According to them, the VocaddrP is located between the FocP and the highest TopP, as shown in (29b).

| Yo, | Jessica, | quiero | ir | a | ver | una | película. |

| I | Jessica voc | want-1sg | go | to | see | a | film |

| ‘I, Jessica, want to go to a movie.’ | |||||||

| (Slocum 2016: 108, our translation) | |||||||

| [ForceP Forceº [TopP* Topº* [ Voc(addr)P Voc addr ° [FocP Focº [TopP* Topº* [FinP Finº]]]]] |

This analysis allows for three predictions concerning the grammaticality of middle vocatives in wh-interrogatives. First, wh-interrogatives with bare wh-elements do not allow middle vocatives since bare wh-elements are located below the VocaddrP: in FocP, and the T-to-C movement that carries the wh-feature from T to the left periphery ensures that no other constituent can intervene between the wh-phrase and the verb (Rizzi 1997). The results of our acceptability judgment task show that middle vocatives are indeed unacceptable in wh-interrogatives with qué (‘what’) (30a). Thus, Slocum’s (2016) analysis accounts for this fact, as illustrated in (30b).

| *¿Qué, | Natalia, | has | señalado | en | el | texto? |

| what | Natalia voc | have-2sg | marked | in | the | text |

| ‘What did you mark in the text, Natalia?’ | ||||||

| [ForceP [TopP* [ Voc(addr)P Natalia [FocP qué [TopP* [FinP …]]]]]] |

Second, the co-occurrence of fronted foci and middle vocatives should also be excluded according to Slocum’s (2016) analysis due to similar reasons as for bare wh-interrogatives: Focus fronting does not allow another constituent to intervene between the fronted focus and the verb. For instance, it requires the reordering of subject and verb (Leonetti 2018). Example (31) confirms this prediction and shows that middle vocatives cannot be inserted between the fronted focus and the verb. Recall, a similar behavior has been observed by Ashdowne (2002) for cleft sentences, as shown in (15).

| *El | bocadilloFoc, | María, | he | comido | (y | no | la | ensalada). |

| the | sandwich | María voc | have-1sg | eaten | (and | not | the | salad) |

| ‘I have eaten THE SANTDWICH (and not the salad).’ | ||||||||

Third, if Slocum’s (2016) analysis is correct, we expect that d-linked wh-phrases can co-occur with middle vocatives (see [32a]) because the highest TopP is their final landing side which is already endowed with the wh-feature (see Rizzi 2006 for details). This TopP is located above the VocAddrP and the wh-phrases can directly precede the middle vocative. Our experimental results reveal that Slocum’s (2016) analysis correctly predicts the occurrence of middle vocatives in wh-interrogatives introduced by d-linked wh-phrases, as shown in (32b).

| ¿Con | qué | color, | Natalia, | has | señalado | la | palabra | “correr”? |

| with | what | color | Natalia voc | have-2sg | marked | the | word | run |

| ‘With what color, Natalia, did you mark the word “run”?’ | ||||||||

| [ForceP [TopP* Con qué color [ Voc(addr)P Natalia [FocP [TopP* [FinP …]]]]]] |

Slocum’s (2016) analysis alone is not able to predict the position of por qué (‘why’) relative to the middle vocative in the left periphery, i.e., if middle vocatives can occur in wh-interrogatives introduced by por qué (‘why’). Remember, the literature on ‘why’-interrogatives has shown that ‘why’ allows different elements to precede the verb suggesting that it is also more permissive with respect to middle vocatives. The results of our experiment confirm this hypothesis and show that middle vocatives are accepted to a certain extent. This finding implies that ‘why’ is located higher in the syntactic structure than middle vocatives. The combination of Slocum’s (2016) and Rizzi’s (2001) analysis (see [33]) could explain this order if we assume that IntP is located above VocaddrP, as shown in (34).

| [ForceP [TopP* [IntP [TopP* [FocP [TopP* [FinP … ]]]]] |

| (Rizzi 2001: 289) |

| ¿Por qué, | Natalia, | has | señalado | este | párrafo? |

| why | Natalia voc | have-2sg | marked | this | paragraph |

| ‘Why, Natalia, did you mark this paragraph?’ | |||||

| [ForceP [TopP* [IntP por qué [TopP* [ Voc(addr)P Natalia [FocP [TopP* [FinP …]]]]]] |

This assumption is reinforced by the placement of topics relative to the middle vocative. The middle vocative can be preceded and followed by a topic:

| ¿Por qué | en | ese | lugar, | María, | todo | va | bien? |

| why | in | this | place | María voc | everything | goes | fine |

| ‘Why is everything fine in this place, Maria?’ | |||||||

| ¿Por qué, | María, | en | ese | lugar | todo | va | bien? |

| why | María voc | in | this | place | everything | goes | fine |

| ‘Why is everything fine in this place, Maria?’ | |||||||

This variation of the topic position is also found in wh-interrogatives introduced by d-linked wh-phrases (36). This indicates that VocaddrP is located between the second TopP and the FocP. Therefore, we assume the structure in (37) for the left periphery.

| ¿A | qué | chica | en | ese | lugar, | María, | has | visto? |

| prep | what | girl | in | this | place | María voc | have-2SG | seen |

| ‘Which girl have you seen in this place, María?’ | ||||||||

| ¿A | qué | chica, | María, | en | ese | lugar | has | visto? |

| prep | what | girl | María voc | in | this | place | have-2SG | seen |

| ‘Which girl have you seen in this place, María?’ | ||||||||

| [Voc(call)P [ForceP [TopP [IntP [TopP [ Voc(addr) [FocP [TopP [FinP …]]]]]]]]] |

7.2.3 An approach to final vocatives in the left periphery

For final vocatives, the related literature proposes different syntactic analyses (see Section 7.1). These analyses are mainly based on data with initial and middle vocatives, whereas final vocatives are treated only incidentally. Remember, Slocum (2016) and González López (2019) suppose a single VocaddrP for middle and final vocatives. Their core argument for this single VocaddrP to the left of the FocP is that addressees can only appear to the left of the focal constituent, as described in Section 7.1.

We argue that this analysis is problematic, especially in combination with different wh-interrogatives, and that addressees can indeed appear to the right of the FocP. We illustrate this issue with two examples. First, wh-interrogatives with bare wh-phrases, such as qué, can co-occur with final vocatives (38), as shown by the results of our acceptability judgment task. This result is unexpected in Slocum’s (2016) analysis because wh-elements like qué are moved to the FocP in the left periphery and freeze in this position (Rizzi 1997), so they cannot further be moved above the addressee.

| ¿QuéFoc | has | señalado | en | el | texto, | Natalia? |

| what | have-2sg | marked | in | the | text | Natalia voc |

| ‘What did you mark in the text, Natalia?’ | ||||||

The second piece of evidence against Slocum’s (2016) analysis comes from wh-interrogatives with ‘why’. In these sentences, addressees can precede and follow focal material. The following example shows a focal object in both positions: to the right (see [39a]) and to the left of an addressee (see [39b]). Recall, according to Slocum (2016), the structure in (39b) should be excluded due to the characteristic of middle addressees to lie at the boundary between focus and background and her assumption that middle and final vocatives occupy the same position.

| ¿Por qué, | María, | has | comido | el | bocadillo Foc | ||||

| why | María voc | have-2sg | eaten | the | sandwich | ||||

| (y | no | la | ensalada)? | ||||||

| (and | not | the | salad) | ||||||

| ‘Why did you eat the sandwich (and not the salad), María?’ | |||||||||

| ¿Por qué | has | comido | el | bocadillo Foc | (y | no | la | ||

| why | have-2sg | eaten | the | sandwich | (and | not | the | ||

| ensalada), | María? | ||||||||

| salad) | María voc | ||||||||

| ‘Why did you eat the sandwich (and not the salad), María?’ | |||||||||

Note that this observation is not language-specific for Spanish or even a property of Romance languages. We find final vocatives in ‘why’-interrogatives with a focal object in other languages, such as German (40a) or Italian (40b). Consequently, there are many examples from different languages that remain unexplained.

| Warum | hast | du | das | Brot Foc | gegessen, | Maria? |

| why | have | you | the | sandwich | eaten | Maria voc |

| ‘Why did you eat the sandwich, Maria?’ | ||||||

| Perché | hai | mangiato | il | paninoFoc, | Maria? |

| why | have-2sg | eaten | the | sandwich | Maria voc |

| ‘Why did you eat the sandwich, Maria?’ | |||||

To address these outstanding examples, a modified approach for final vocatives is required. We assume that there is a second VocaddrP in addition to the one proposed by Slocum (2016) and González López (2019): an upper VocaddrP above FocP, as described in Section 7.2.2, and a lower one below the FocP.[10] We suggest that this lower VocaddrP is located between the lowest TopP and the FinP, as shown in (41). The reason for this position is a change in information structure that we observe in the case of final vocatives: the information that was previously interpreted as new (see [42a]), is interpreted as given and especially highlighted, in (42b).

| [ForceP [TopP [IntP [TopP [ Voc(addr)P [FocP [TopP [ Voc(addr)P [FinP …]]]]]]]]]] |

| Hace | frío. |

| makes | cold |

| ‘It’s cold.’ | |

| Hace | frío, | Natalia. |

| makes | cold | Nataliavoc |

| ‘It’s cold, Natalia.’ |

Similar to the declarative sentence in (42b), has comido [el bocadillo] focus in the ‘why’-interrogative (39b) has to be given in the previous context and receives the interpretation of a reproach. The whole IP is the entity about which the reason asked for and can therefore be considered as a topic. Consequently, we assume that the IP underlies remnant topicalization (Belletti 2004) and the final vocative remains in-situ due to its special intonation, as proposed for initial and middle vocatives, as shown in Section 2 (for a similar analysis for Italian final particles, see Munaro and Poletto 2005, 2009). The syntactic analysis for (39b) is shown in the following example:

|

Consequently, our proposal allows for a uniform analysis of final vocatives (44) that are highly acceptable in all wh-interrogatives according to the results of our acceptability judgment task.

| [ForceP [TopP d-linked wh-phrasesk [IntP why [TopP [Voc(addr)P [FocP whatj [TopP […]i [ Voc(addr)P Natalia [FinP … ti tj/tk]]]]]]]]] |

This analysis further addresses the fact that Spanish allows for multiple addressees within one sentence (in contrast to English),[11] as shown in (45a) for wh-interrogatives and (45b) for declaratives.

| ¿Por qué, | Antonio, | has | regalado | este | libro | a | tu | ||

| why | María voc | have-2sg | given | this | book | to | your | ||

| hermano, | hombre? | ||||||||

| brother | man voc | ||||||||

| ‘Why, María, did you give this book to your brother, man?’ | |||||||||

| A | tus | amigas, | Ana, | las | vi | ayer, | cielo. |

| prep | your | friends | Ana voc | them | saw-1sg | yesterday | honey voc |

| ‘Your friends, Ana, I saw them yesterday, honey.’ | |||||||

In the case of multiple addressees, we observe the same change in information structure, as described above. To illustrate this change, we reconsider example (16):

| Jessica: | Creo | que | deberíamos | quedarnos | en | casa | ||

| Jessica | think-1sg | that | should-1pl | stay-ourselves | at | home | ||

| esta | noche. | |||||||

| this | night | |||||||

| ‘Jessica: I think we should stay in tonight.’ | ||||||||

| Paul: | Yo, | Jessica, | quiero | ir | al | cine. | ||

| Paul: | I | Jessica voc | want-1sg | go | to-the | cinema | ||

| ‘Paul: I, Jessica, want to go to a movie.’ | ||||||||

Remember, in this example, the middle vocative marks the edge of the focus domain which is the right part of the sentence. However, if we add a final vocative to Paul’s sentence (see [47]), the information structure of the final part changes. It is no longer considered as new information, instead it is interpreted as given information that Paul reminds her of. Thus, quiero ir al cine receives a topic interpretation.[12] The information structure of the subject Yo does not change and is still considered a contrastive topic.

| Jessica: | Creo | que | deberíamos | quedarnos | en | |||

| Jessica | think-1sg | that | should-1pl | stay-ourselves | at | |||

| casa | esta | noche. | ||||||

| home | this | night | ||||||

| ‘Jessica: I think we should stay in tonight.’ | ||||||||

| Paul: | Yo, | Jessica, | quiero | ir | al | cine, | cielo. | |

| Paul: | I | Jessica voc | want-1sg | go | to-the | cinema | honey voc | |

| ‘Paul: I, Jessica, want to go to a movie, honey.’ | ||||||||

The analysis in (48) reflects the information structure of example (47). The subject Yo moves to the highest TopP and quiero ir al cine undergoes phrasal movement to the specifier of the lowest TopP leaving the middle addressee in between. The final addressee follows the topicalized phrase.

|

In sum, we argue that the analysis of vocatives co-occurring with a sentence has to be revisited and that there are three positions for vocatives in the left periphery: the VoccallP above the ForceP, where initial vocatives are located, and two VocaddrP in the lower part of the left periphery for middle and final vocatives. (49) Provides an example of the left periphery including the three projections and showing the corresponding hierarchy.

| [ Voc(call)P [ForceP [TopP [IntP [TopP [ Voc(addr)P [FocP [TopP [ Voc(addr)P [FinP ]]]]]]]]]] |

7.2.4 The position of vocatives and subjects in wh-interrogatives: a comparison

Although vocatives and (preverbal) subjects are distributed equally in the three types of wh-interrogatives, their syntactic analysis reveals crucial differences. As shown above, ‘why’-interrogatives allow subjects and vocatives to intervene between the wh-phrase and the verb. Despite this parallelism, middle vocatives and preverbal subjects occupy different positions in the syntactic structure. For Italian ‘why’-interrogatives, Bianchi et al. (2017) show that the distribution of subjects depends on information structure (see Leonetti 2018 for a similar line of argumentation for Spanish). ‘Neutral’ (non-focal) subjects occur in preverbal position and are moved from their base position to a higher position in the syntactic structure. The related literature provides different accounts for the final landing sites of preverbal subjects. For example, Cardinaletti (2004) assumes that strong and overt preverbal subjects move to the Subj(ect)P(hrase) and weak or null subjects pronouns move to the Specifier of TP, while Barbosa (1995) and Alexiadou and Anagnostopoulou (1998) suggest that preverbal subjects have the same characteristics as clitic left-dislocated topics.[13] Irrespective of which of these positions the preverbal subject moves to, middle vocatives are merged in the left periphery and occupy a different position, namely the VocaddrP, as shown in Section 7.2.2. In contrast to ‘why’-interrogatives, in bare wh-interrogatives, both preverbal subjects and middle vocatives are excluded. The wh-phrase is adjacent to the verb and the potential intervening subject or vocative has to be displaced. Put differently, wh-movement inhibits that first, the subject moves to a higher position and second, the occurrence of middle vocatives.

Not only the preverbal subject position but also the postverbal subject position differs from the position of vocatives. In Italian ‘why’-interrogatives, focal subjects typically occur in postverbal position and are presumably analyzed in FocP of the lower IP internal periphery (Belletti 2004). However, the assumption that this analysis fully applies to Spanish is problematic because Schmid et al. (2021) show that not only focal subjects, but also non-focal subjects are highly preferred in postverbal position in Spanish ‘why’-interrogatives with unergative verbs. Accordingly, focal subjects can be analyzed in the same way as in Italian. Non-focal postverbal subjects remain either in their merge position (e.g., Suñer 1994) or Spanish displays a further lower subject position that is not available in Italian where these subjects can move to, as proposed by Belletti (2004). In bare wh-interrogatives, postverbal subjects are assumed to remain in their base-position (Bocci and Cruschina 2018; Cardinaletti 2001). Importantly, postverbal subjects and final vocatives crucially differ with respect to their syntactic position. While postverbal subjects remain in the lower part of the syntactic tree, final vocatives occupy a position in the left periphery, as discussed in Section 7.1.

8 Conclusion

In this paper, we brought together two previously independent domains of linguistic research by investigating vocative structures in Spanish wh-interrogatives. To this end, we ran an acceptability judgment task to address the following research questions:

In which position are vocatives accepted in wh-interrogatives? (RQ1)

Do d-linked wh-phrases and por qué (‘why’) pose less restriction on the middle positions of vocatives than bare wh-elements? (RQ2)

Which position(s) do initial, middle, and final vocatives occupy in the left periphery? (RQ3)

Regarding RQ1, we found that initial and final vocatives are highly accepted in wh-interrogatives, regardless of the wh-phrase. This implies that initial and final vocatives are compatible with bare wh-elements, por qué (‘why’), and d-linked wh-phrases. For middle vocatives, the experimental results differed between wh-phrases. While the participants (at least marginally) accepted middle vocatives in wh-interrogatives introduced by por qué (‘why’) and d-linked wh-phrases, they rejected them in wh-interrogatives with bare wh-elements (RQ2). Put differently, d-linked wh-phrases and por qué (‘why’) pose less restriction on the middle positions of vocatives than bare wh-elements.

With respect to RQ3, we follow previous work and assume that the position vocatives occupy in the left periphery depends on their semantic-pragmatic function (González López 2019; Slocum 2016). Initial vocatives that have a call interpretation are located in VoccallP, above ForceP (Espinal 2013; González López 2019; Hill 2013b; Moro 2003, a.o.). For middle and final vocatives that have the sematic-pragmatic function of an addressee, we proposed two VocaddrPs in the left periphery. The upper one includes middle vocatives, and it is placed between the second TopP and the FocP. This extension of previous analyses explains the differences found between por qué (‘why’) and d-linked wh-phrases, on the one hand, and bare wh-elements, on the other. The lower VocaddrP in which final vocatives are placed is located between the lowest TopP and the FinP. We assumed this second VocaddrP for two reasons. First, it addresses the fact that Spanish allows for multiple addressees and second, we have seen that addressees can precede and follow focal constituents.

For future research, interesting follow-up questions would be whether other languages also reveal differences for middle vocatives with respect to wh-phrases and whether they allow for focal constituents preceding and following addressees.

Funding source: German Research Foundation

Award Identifier / Grant number: KA1004/4-2

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the audience of the XLIX Simposio Internacional SEL (Universitat Rovira i Virgili, Tarragona) and the 54th Annual Meeting of Societas Linguistica Europaea (National and Kapodistrian University of Athens) where parts of this paper have been presented. We gratefully thank Ricardo Etxepare, Georg A. Kaiser, Anika Lloyd-Smith, Cristina Sánchez López, Anja Weingart, and two anonymous reviewers for their comments and suggestions, which greatly helped us to improve our work. The research of Svenja Schmid was supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG) as part of the research unit FOR-2111 ‘Questions at the Interfaces’ within the project P2 “The structure of wh-utterances and the interpretation of wh-words in Romance (and Germanic) languages” (PI: Georg A. Kaiser, KA 1004/4-2).

-

Research funding: This work was funded by German Research Foundation (Award Number: KA1004/4-2).

References

Adli, Aria. 2010. The semantic role of the wh-element and subject position in Spanish and Catalan. Sprachtypologie und Universalienforschung 63. 103–117. https://doi.org/10.1524/stuf.2010.0009.Search in Google Scholar

Alexiadou, Artemis & Elena Anagnostopoulou. 1998. Parametrizing AGR: Word order, V-movement and EPP-checking. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 16(3). 491–539. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1006090432389.10.1023/A:1006090432389Search in Google Scholar

Ashdowne, Richard. 2002. The vocative’s calling? the syntax of address in Latin. Working Papers in Linguistics, Philology and Phonetics 7. 143–162.Search in Google Scholar

Baayen, Harald R. & Dagmar Divjak. 2017. Ordinal gamms: A new window on human ratings. In Anastasia Makarova, Stephen M. Dickey & Dagmar Divjak (eds.), Each venture a new beginning. Studies in honor of Laura A. Janda, 39–56. Bloomington: Slavica Publishers.Search in Google Scholar

Baayen, Harald R. & Maja Linke. 2019. An introduction to the generalized additive model. A practical handbook of corpus linguistics. Berlin: Springer.10.1007/978-3-030-46216-1_23Search in Google Scholar

Bañón, Antonio M. 1993. El vocativo en español. Propuesta para el análisis lingüístico. Barcelona: Octaedro SL.Search in Google Scholar

Barbosa, Pillar. 1995. Null subjects. Massachusetts: Massachusetts Institute of Technology PhD thesis.Search in Google Scholar

Barbosa, Pillar. 2001. On inversion in wh-questions in Romance. In Aafke Hulk & Jean-Yves Pollock (eds.), Subject inversion in romance and the theory of universal grammar, 20–60. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780195142693.003.0002Search in Google Scholar

Belletti, Adriana. 2004. Aspects of the low IP area. In Luigi Rizzi (ed.), The structure of CP and IP, 16–51. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780195159486.003.0002Search in Google Scholar

Bianchi, Valentina, Giuliano Bocci & Silvio Cruschina. 2017. Two types of subject inversion in Italian wh-questions. Revue Roumaine de Linguistique 62(3). 233–252.Search in Google Scholar

Bocci, Giuliano & Silvio Cruschina. 2018. Postverbal subjects and nuclear pitch accent in Italian wh-questions. In Roberto Petrosino, Pietro Cerrone & Harry van der Hulst (eds.), From sounds to structures. Beyond the Veil of Maya, 467–494. Berlin: De Gruyter.10.1515/9781501506734-017Search in Google Scholar

Brandimonte, Giovanni. 2011. Breve estudio contrastivo sobre los vocativos en el español y el italiano actual. In Jorge Juan Sánchez Iglesias, Javier de Santiago-Guervós, Marta Seseña Gómez & Hanne Bongaerts (eds.), Del texto a la lengua: la aplicación de los textos a la enseñanza-aprendizaje del español L2–LE, vol. 1, 249–262. Salamanca: Asociación para la Enseñanza del Español como Lengua Extranjera – ASELE.Search in Google Scholar

Camacho, José. 2006. Do Subjects have a place in Spanish? In Chiyo Nishida & Jean-Pierre Y. Montreuil (eds.), New perspectives on romance linguistics. Volume I: Morphology, syntax, semantics, and pragmatics. Selected papers from the 35th Linguistic Symposium on Romance Languages (LSRL), Austin, Texas, February 2005, 51–66. Amsterdam: Benjamins.10.1075/cilt.275.06camSearch in Google Scholar

Cardinaletti, Anna. 2001. A second thought on emarginazione: Destressing vs. ‘right dislocation. In Gugliemo Cinque & Giampaolo Salvi (eds.), Current studies in Italian syntax. Essays offered to Lorenzo Renzi, 117–135. Amsterdam: Elsevier.10.1163/9780585473949_008Search in Google Scholar

Cardinaletti, Anna. 2004. Toward a cartography of subject positions. In Luigi Rizzi (ed.), The structure of CP and IP. The cartography of syntactic structures, vol. 2, 115–165. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780195159486.003.0005Search in Google Scholar

Cognola, Federica & Silvio Cruschina. 2021. Between time and discourse: A syntactic analysis of Italian poi. Annali di Ca’Foscari. Serie Occidentale 55. 87–116.10.30687/AnnOc/2499-1562/2021/09/015Search in Google Scholar

Contreras, Heles. 1999. Relaciones entre las construcciones interrogativas, exclamativas y relativas. In Ignacio Bosque & Violeta Demonte (eds.), Gramática descriptiva de la lengua española, vol. 2, 1931–1962. Madrid: Espasa Calpe.Search in Google Scholar

Dumitrescu, Domnita. 2016. Oraciones interrogativas directas. In Javier Gutiérrez-Rexach (ed.), Enciclopedia de lingüística hispánica, vol. 1, 750–760. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781315713441-66Search in Google Scholar

Edeso Natalías, Verónica. 2005. Usos discursivos del vocativo en español. Español Actual 84. 123–142.Search in Google Scholar

Espinal, María Teresa. 2013. On the structure of vocatives. In Barbara Sonnenhauser & Patrizia Noel Aziz Hanna (eds.), Vocative! Addressing between system and performance, 109–132. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter.10.1515/9783110304176.109Search in Google Scholar

Esposito, Giorgia. 2021. Partículas discursivas y contrastividad: Un estudio sobre ‘pues. Orillas Rivista d’ispanistica 10. 347–377.Search in Google Scholar

Fábregas, Antonio and José Luis Mendívil. 2013. Variación sintáctica por medio de exponentes: Sujetos preverbales en Venezuela. Paper presented at the Sociedad Española de Lingüística. XLII Simposio Internacional. Madrid, 22–25 January.Search in Google Scholar

Francom, Jerid. 2012. Wh-movement: Interrogatives, exclamatives, and relatives. In José Ignacio Hualde, Antxon Olarrea & Erin O’Rourke (eds.), The handbook of hispanic linguistics, 533–556. Malden: Blackwell.10.1002/9781118228098.ch25Search in Google Scholar

Frascarelli, Mara & Roland Hinterhölzl. 2007. Types of topics in German and Italian. In Kerstin Schwabe & Susanne Winkler (eds.), On information structure, meaning and form. Generalizations across languages, 81–116. Amsterdam: Benjamins.10.1075/la.100.07fraSearch in Google Scholar

González López, Laura. 2019. Aspectos gramaticales del vocativo en español. Madrid: Universidad Complutense de Madrid PhD thesis.Search in Google Scholar

González López, Laura & Andreas Trotzke. 2021. ¡Mira! the grammar-attention interface in the Spanish left periphery. The Linguistic Review 38(1). 5–31. https://doi.org/10.1515/tlr-2021-2057.Search in Google Scholar

Goodall, Grant. 1993. Spec of IP and spec of CP in Spanish wh-questions. In William J. Ashby, Marianne Mithun, Giorgio Perissinotto & Eduardo Raposo (eds.), Linguistic perspectives on the romance languages. Selected papers from the 21st Linguistic Symposium on Romance Languages (LSRL XXI). Santa Barbara, California, 21–24 February 1991, 199–209. Amsterdam: Benjamins.10.1075/cilt.103.21gooSearch in Google Scholar

Goodall, Grant. 2002. On preverbal subjects in Spanish. In Teresa. Satterfield, Christina Tortora & Diana Cresti (eds.), Current issues in romance languages. Selected papers from the 29th Linguistics Symposium on Romance Languages (LSRL), Ann Arbor, 8–11 April 1999, 95–109. Amsterdam: Benjamins.10.1075/cilt.220.08gooSearch in Google Scholar

Goodall, Grant. 2004. On the syntax and processing in wh-questions in Spanish. In Vineeta Chand, Ann Kelleher, Angelo J. Rodríguez & Benjamin Schmeiser (eds.), Proceeding from the 23rd West Coast conference on formal linguistics, 237–250. Somerville: Cascadilla Press.Search in Google Scholar

Goodall, Grant. 2005. The limits of syntax in inversion. In Rodney L. Edwards (ed.), Proceedings of meeting of the Chicago Linguistic Society, vol. 41, 161–174. Chicago: Chicago Linguistic Society.Search in Google Scholar

Grewendorf, Günther. 2002. Left dislocation as movement. In Simon Mauck & Jenny Mittelstaedt (eds.), Georgetown university working papers in theoretical linguistics, vol. 2, 31–81.Search in Google Scholar

Hill, Virginia. 2007. Vocatives and the pragmatics-syntax interface. Lingua 117. 2077. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2007.01.002.Search in Google Scholar

Hill, Virginia. 2013a. Features and strategies: The internal syntax of vocative phrases. In Barbara Sonnehauser, Patrizia Noel & Aziz Hanna (eds.), Vocative! Addressing between system and performance, 133–155. Berlin: Mouton Gruyter.10.1515/9783110304176.133Search in Google Scholar

Hill, Virginia. 2013b. Vocatives. How syntax meets with pragmatics. Leiden (Boston): Brill.10.1163/9789004261389Search in Google Scholar

Kaiser, Georg A., Klaus von Heusinger & Svenja Schmid. 2019. Word order variation in Spanish and Italian interrogatives. The role of the subject in ‘why’-interrogatives. In Natascha Pomino (ed.), Proceedings of the IX Nereus International Workshop: “Morphosyntactic and Semantic Aspects of the DP in Romance and Beyond”, 69–90. Konstanz: Fachbereich Linguistik, Universität Konstanz (= Arbeitspapier 131).Search in Google Scholar

Kleinknecht, Friederike. 2019. Der Vokativ und seine Verwendung im gesprochenen Spanisch. München: Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität PhD Dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Leonetti, Manuel. 2018. Two types of postverbal subject. Italian Journal of Linguistics 30(2). 11–36.Search in Google Scholar

López, Luis. 2009. A derivational syntax for information structure. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199557400.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

López, Luis. 2013. Wh-movement. In Silvia Luraghi & Claudia Parodi (eds.), The Bloomsbury Companion to syntax, 311–324. London: Bloomsbury.10.5040/9781472542090.ch-018Search in Google Scholar

Martín, Juan. 2003. Against a uniform wh-landing site in Spanish. In Paula Kempchinsky & Carlos-Eduardo Piñeros (eds.), Theory, practice, and acquisition. Papers from the 6th Hispanic Linguistics Symposium and the 5th Conference on the Acquisition of Spanish and Portuguese, 156–174. Cascadilla: Somerville.Search in Google Scholar

Moro, Andrea. 2003. Notes on vocative case: A case study in clause structure. In Josep Quer, Schroten Jan, Mauro Scorretti, Petra Sleeman & Els Verheugd (eds.), Romance Languages and linguistic theory 2001, 251–265. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/cilt.245.15morSearch in Google Scholar

Munaro, Nicola & Cecilia Poletto. 2005. On the diachronic origin of sentential particles in Nothern-Eastern Italian dialects. Nordic Journal of Linguistics 28(2). 1–17.10.1017/S0332586505001447Search in Google Scholar

Munaro, Nicola & Cecilia Poletto. 2009. Sentential particles and clausal typing in Venetian dialects. In Benjamin Shaer, Philippa Cook, Werner Frey & Claudia Maienborn (eds.), Dislocated elements in discourse, 173–199. New York, London: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Prieto, Pilar & Paolo Roseano. 2010. Introduction. In Pilar Prieto & Paolo Roseano (eds.), Transcription of intonation of the Spanish language, 1–15. Munich: Lincom Europa.Search in Google Scholar

Real Academia Española y Asociación de Academias de la Lengua Española. 2009. Nueva gramática de la lengua española. Morfología y Sintaxis I y II. Madrid: Espasa.Search in Google Scholar

Rizzi, Luigi. 1996. Residual verb second and the wh-criterion. In Adriana Belletti & Luigi Rizzi (eds.), Parameters and functional heads. Essays in comparative syntax, 63–90. New York: Oxford University Press.10.4324/9780203461785-15Search in Google Scholar

Rizzi, Luigi. 1997. The fine structure of the left periphery. In Liliane Haegeman (ed.), Elements of grammar. Handbook in generative syntax, 281–337. Dordrecht: Kluwer.10.1007/978-94-011-5420-8_7Search in Google Scholar

Rizzi, Luigi. 2001. On the position Int(errogative) in the left periphery of the clause. In Guglielmo Cinque & Giampaolo Salvi (ed.), Current studies in Italian syntax offered to Lorenzo Renzi, 287–296. Amsterdam: Elsevier.10.1163/9780585473949_016Search in Google Scholar

Rizzi, Luigi. 2006. Selective residual V-2 in Italian interrogatives. In Patrick Brandt & Erik Fuß (eds.), Form, structure and grammar. A Festschrift presented to Günther Grewendorf on occasion of His 60th birthday, 229–241. Berlin: Akademie Verlag.10.1524/9783050085555.229Search in Google Scholar

Scherre, Maria Marta Pereira & Anthony J. Naro. 1992. The serial effect on internal and external variables. Language Variation and Change 4(1). 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0954394500000636.Search in Google Scholar

Schmid, Svenja, Klaus von Heusinger & Georg A. Kaiser. 2021. On word order and information structure in Peninsular Spanish and Italian ‘why’ interrogatives. Cadernos de Estudos Linguisticos 63. 1–17. https://doi.org/10.20396/cel.v63i00.8661251.Search in Google Scholar

Sheehan, Michelle. 2006. The EPP and null subjects in Romance. Newcastle University PhD thesis.Search in Google Scholar

Shlonsky, Ur & Gabriela Soare. 2011. Where’s ‘why. Linguistic Inquiry 42. 651–669. https://doi.org/10.1162/ling_a_00064.Search in Google Scholar

Slocum, Poppy. 2010. The vocative and the left periphery. Handout presented in Vocative! at the University of Bamberg, Germany. Available at: https://www.uni-bamberg.de/germ-ling1/archiv-veranstaltungen/workshop-vocative-10-11-december-2010.Search in Google Scholar

Slocum, Poppy. 2016. The syntax of address. New York: University of Stony Brook PhD Dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Speas, Peggy & Carol Tenny. 2003. Configurational properties of point of view roles. Asymmetry in Grammar: Syntax and Semantics 1. 315–344.10.1075/la.57.15speSearch in Google Scholar

Stavrou, Melita. 2009. Vocative! Universidad de Thessaloniki: Ms. Aristotle.Search in Google Scholar

Stavrou, Melita. 2014. About the vocative. The Nominal Structure in Slavic and Beyond 116. 299–342. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781614512790.299.Search in Google Scholar

Stepanov, Arthur & Wei-tien Dylan Tsai. 2008. Cartography and licensing of wh-adjuncts: A cross-linguistic perspective. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 26. 589–638. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-008-9047-z.Search in Google Scholar

Suñer, Margarita. 1994. V-movement and the licensing of argumental wh-phrases in Spanish. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 12. 335–372. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00993148.Search in Google Scholar

Taglicht, Josef. 1984. Message and emphasis. On focus and scope in English. London: Longman.Search in Google Scholar

Thornton, Rosalind. 2008. Why continuity. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 26. 107–146. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-007-9031-z.Search in Google Scholar

Torrego, Esther. 1984. On inversion in Spanish and some of its effects. Linguistic Inquiry 115. 103–129.Search in Google Scholar

Wood, Simon N. 2006. Generalized additive models. New York: Chapman & Hall/CRC.10.1201/9781420010404Search in Google Scholar

Zwicky, Arnold. 1974. Hey, whatsyourname. In Michael W. La Galy, Robert Allen Fox & Bruck Anthony (eds.), Papers from the tenth regional meeting of the Chicago Linguistics Society, 787–801. Chicago: Chicago Linguistics Society.Search in Google Scholar

© 2022 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Articles

- Output-conditioned and non-local allomorphy in Armenian theme vowels

- Ablaut in Cairene Arabic

- Vocative, where do you hang out in wh-interrogatives?

- From relative proadverb to declarative complementizer: the evolution of the Hungarian hogy ʻthatʼ

- Optimal place specification, element headedness and surface velar palatalization in Polish

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Articles

- Output-conditioned and non-local allomorphy in Armenian theme vowels

- Ablaut in Cairene Arabic

- Vocative, where do you hang out in wh-interrogatives?

- From relative proadverb to declarative complementizer: the evolution of the Hungarian hogy ʻthatʼ

- Optimal place specification, element headedness and surface velar palatalization in Polish