Abstract

The variety of Basque characteristic of Getxo exhibits a form of coronal palatalisation that takes place intervocalically within and across words, triggered by a preceding [i] or [j]. This system in particular is interesting because it sets up a paradox as it both applies and does not apply at the word-level. The rule is sensitive to the leftward phonological context within the word-level and the rightward phonological context at the phrase level since in Getxo the trigger and target of palatalisation must come from the same word, yet the process only occurs if this sequence precedes a vowel-initial juncture: /in##V/, /il##V/. A previous solution involves stating palatalisation as a lexical rule and invoking a Duke-of-York Derivation to generate the masses of lexical exceptions attested largely in loanwords. This account misses a crucial generalisation, which is that, loanwords or not, there are no lexical exceptions across morphemes. We capture this generalisation and resolve the ordering paradox by relating palatalisation to the positional distribution of place features general in the language. This analysis involves positional underspecificaiton of nasals/laterals and a coronal default place of articulation. Underspecified nasals and laterals need place when they “become onsets” across word-boundaries, including through palatal spreading. In the reanalysis there are no “lexical exceptions” since these are underlyingly specified for place; neither is there need for word-level versus post-lexical phonology.

1 Introduction: the phenomenon

This paper focuses on the palatalisation pattern of Getxo Basque. Getxo is a town situated on the right side of the mouth of the Nervión river, fourteen kilometres north of Bilbao in the province of Biscay, in the Basque Country of Spain. Though it retains a distinct identity, the town is currently part of the Greater Bilbao metropolitan area.

Palatalisation is a common feature across Basque dialects, however, its extent as well as its triggers and targets vary significantly depending on the dialect. Broadly, these are classified by Hualde (1991: 108) as (a) Restrictive (e.g., Baztan), (b) Intermediate (e.g., Donostia), and (c) General (e.g., Northern Biscayan). Small dialectal differences can reflect very different phonological systems. For instance, the palatalisation recorded in Getxo Basque (and referred to in Hualde and Bilbao (1992)’s work; henceforth: HB) is very different from that recorded in Gernika (although both belong to the Northern Biscayan dialect area) and appears to be an ongoing phenomenon currently under innovation (Itxaso Rodriguez p.c.). The traditional Basque variety of Getxo in the form analysed in the present paper is, to a certain extent, still spoken in at least one neighbourhood of this town, but the great majority speak Standard Basque, not the variety described in HB. Nevertheless, each variety needs and deserves to be investigated fully, and continue to be investigated as it evolves by whatever speakers use them. Therefore, we assume the form of the variety as documented in HB and set out to comprehensively characterise the type of palatalisation it exhibits.

In Getxo Basque (henceforth: Getxo), HB report a fascinating case of lateral and nasal palatalisation, exhibiting alternations in the following contexts. The consonants /n/ and /l/ are replaced with [ɲ] and [ʎ], respectively, in intervocalic position when the leftward phonological context is constituted by /i/ or the /j/ offglide of diphthongs (for the vowel system of Getxo, see Section 3.4).

|

||||

| Uninfl | ABS.SG | |||

| min | [mín] | miñe | [miɲ-é] | ‘pain’ |

| oin | [ójn] | oñe | [oɲ-é] | ‘foot’ |

| suin | [sújn] | suñe | [suɲ-é] | ‘son-in-law’ |

| mutil | [mutíl] | mutille | [mutiʎ-é] | ‘boy’ |

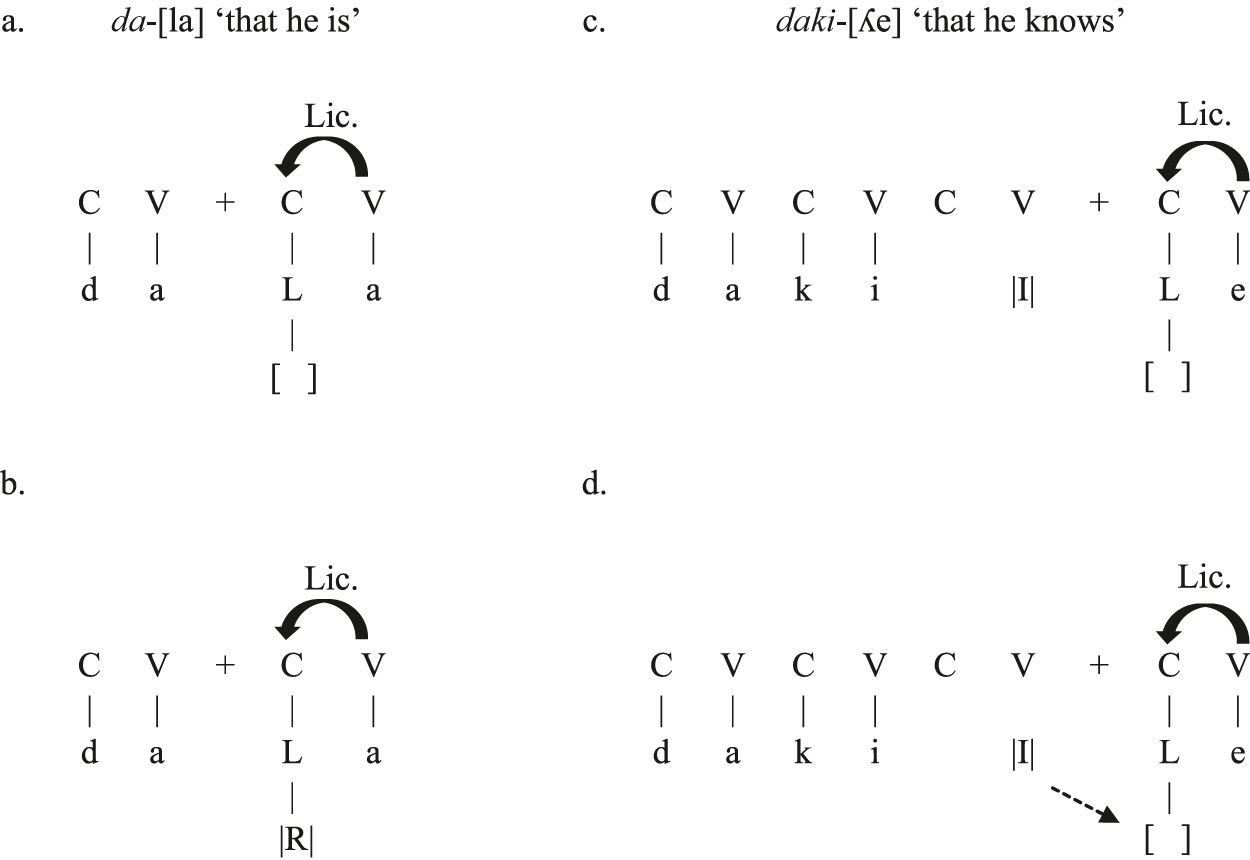

There is also palatalisation of the initial consonant of a suffix or clitic, e.g., the genitive -na/-ne (2a), the distributive -nan/-nen (2b) and the complementisers in (2c).

| Morpheme-initial palatalisation (HB pp. 22–23) |

| Mári-[ɲe] | ‘of Mary’ | cf. | gizona-[na] | ‘of the man’ |

| mendi-[ɲe] | ‘of the mountain’ | baso-[na] | ‘of the forest’ | |

| txarri-[ɲe] | ‘of the pig’ | buru-[ne] | ‘of the head’ |

| bi-[ɲen] | ‘two by two’ | ba-[nan] | ‘one by one’ |

| daki-[ʎe] | ‘that he knows’ | da-[la] | ‘that he is’ |

| du-[le] | ‘that we have’ | ||

| daki-[ɲe] | ‘what he knows’ | da-[na] | ‘what he is’ |

| du-[ne] | ‘what we have’ | ||

| daki-[ʎekon] | ‘because he knows’ | da-[lakon] | ‘because he is’ |

| du-[lekon] | ‘because we have’ |

As shown in (1) above, after /i/ and the j-final diphthongs, palatalisation applies identically. Also note that in all these cases the palatalising vowel/glide appears to the left of the target sonorant (rather than to its right, as in more widely known examples of palatalisation in Slavic or English). In Getxo (unlike other varieties) the offglide alternates with zero within the word: it is present when no palatalisation takes place (see the uninflected forms in (1)) but disappears when the palatal is produced (see the second column in (1)) – this is what HB call the “absorption” of the preceding glide. However, the outcome is the unabsorbed form when palatalisation occurs across word boundaries, see (3b).

| Palatalisation before V-initial words (across prosodic words) (HB p. 23) |

| with [i] as trigger: | ||

| min in | [míɲ in] | ‘to hurt’ |

| arin etor nas | [ariɲ etor nás] | ‘I came fast’ |

| mutil andi | [mutiʎ andí] | ‘big boy’ |

| il árten | [iʎ árten] | ‘until dying’ |

| with surface diphthongs as triggers, no absorption: | ||

| oin andi | [ojɲ andí] | ‘big foot’ |

| o(ra)in ori da | [ojɲ orí ða] | ‘now, it is that’ |

| áin ósten | [ájɲ ósten] | ‘behind them’ |

| bein urten badot | [bejɲ urtem báðot] | ‘if I left once’ |

| orain asi dire | [orájɲ asi diré] | ‘now they have started’ |

Crucially, on this postlexical level, the trigger vowel and the target sonorant are in the same prosodic word (see, e.g., min in (3a) or oin in (3b)) and it is only the rightward vocalic environment that comes from the second word in the string (ultimately creating the intervocalic context for the target consonant).

Inside words, the status of palatalisation is rather ambiguous: on the one hand, there are a number of loans and historical forms that have shown sporadic palatalisation (see in (8) below); on the other hand however, very many lexical exceptions are to be found where no palatalisation has occurred (and these are not all recent borrowings) (4a), and even include at least one native root (4b).

| Palatalisation exceptions (HB pp. 23–24 – underlining added for highlight)[2] |

| arrúina | ‘to ruin’ | pepíno | ‘cucumber’ |

| klínika | ‘clinic’ | abilidoso | ‘clever’ |

| gabardína | ‘raincoat’ | ilusiño | ‘illusion’ |

| gasolína | ‘gasoline’ | jubilasiño | ‘retirement’ |

| famíli | ‘family’ | milágru | ‘miracle’ |

| mineral | ‘mineral’ | ||

| makinísta | ‘machine-driver’ | but: mákiña | ‘machine’ |

| isilik | ‘silent’[3] |

In this paper, we will show that the significance of the pattern sketched out lies in its architecture, which leads the classical, rule-based Lexical Phonological account to an ordering paradox and to masses of “lexical exceptions” (Section 2). Instead, we propose to relate the palatalisation facts to the positional distribution of place features of nasals and laterals, as well as the process of nasal place assimilation across word boundaries, which are overall characteristics of Getxo (and, in fact, Basque in general). Our reanalysis (in Section 3) will be formalised in the framework of Strict CV (or CVCV) Phonology (Lowenstamm 1996; Scheer 2004), armed with a Coda Mirror style theoretical toolkit (Ségéral and Scheer 1999, 2001), and accompanied by Element Theory (Backley 2011; KLV 1985), which we introduce for the unfamiliar reader in Section 3.1.

In this analysis we argue that palatalisation within the prosodic word and across words are both driven by the mechanism to derive place for nasals and laterals, and the apparent differences do not justify the word-level versus post-lexical distinction but result from two different autosegmental configurations of empty skeletal positions readily captured by Strict CV structures. The presentation is organised in such a way that the complexities of the derivations unfold gradually, in a step-by-step fashion: the distributional facts of place and the conditions on place licensing are explained first (Section 3.2), and the palatalisation process itself as it affects lexically placeless root-final sonorants is modelled next (Section 3.3).

Then Section 3.4 adds to the discussion the extra complication that comes from the representation of the palatalising vowels and leads to the vocalic alternation (absorption vs. the absence thereof). The claim is made that not only does Getxo neutralise bipositional structures of identical melodies (geminates) for length on the surface in consonants but it also does so in vowels; the trigger is always a diphthong offglide, phonologically a floating melodic prime. Accordingly, we revisit all subcases previously analysed and give the full analysis to each. Finally, Section 4 concludes.

2 Significance of the pattern

2.1 Architecture of the process

Getxo is of particular theoretical interest because HB’s analysis of the facts creates something of a paradox. HB note that Getxo palatalisation both seems to apply and not apply at the phrasal level; this is because the palatalisation rule is sensitive to both the leftward phonological context within the word-level and the rightward phonological context of the phrase level. As shown in (5), the trigger and the target of palatalisation need to belong to the same word /in##V/ and /il##V/. If the trigger and target belong to different words (5b) the process does not occur.

| /in##V/ and /il##V/ (key examples repeated from (3)) | ||

| oin + andi | [ojɲ andí] | ‘big foot’ |

| mutil + andi | [mutiʎ andí] | ‘big boy’ |

| /i##n/ and /i##l/ (HB p. 23) | ||

| saldi + naiko | [saldi najko] *[saldi ɲajko] | ‘enough horses’ |

| mendi + luse | [mendi luse] *[mendi ʎuse] | ‘long mountain’ |

The data in (5) seem to suggest that the process does not occur above the word level; however, information about the next word is still needed to determine the outcome: it is palatal when followed by vowel-initial words (as in (3) and (5a)), but a homorganic nasal (6a) or a coronal lateral (homorganic or default) (6b) when followed by consonant-initial ones. So the rule does not appear to be wholly lexical.

| /in##C/ and /il##C/ (HB p. 23) |

| sein + gure (dosu) | [séjŋ ɡure] | *[séjɲ ɡure] | ‘which one do you want’ |

| agin + betek | [aɣim beték] | *[aɣiɲ beték] | ‘a tooth’ |

| il + san | [il sán] | *[iʎ sán] | ‘he died’ |

| mutil + bet | [mutil βét] | *[mutiʎ βét] | ‘a boy’ |

The solution HB propose is effective, though it involves a complex derivation. They assume that [ɲ, ʎ] are synchronically allophonic and always derived from UR /in, il/ (cf. non-alternating [ɲ, ʎ] such as /troinu/ [troɲu] ‘knot’ and /akuilu/ [akuʎu] ‘stable’). Then they claim that the palatalisation rule is actually lexical. This accounts for the non-application of the rule when the trigger and target do not come from the same word (5b). Naturally however, this wrongly predicts that all lexical /in/, /jn/ or /il/, /jl/ should palatalise, although there are many lexical exceptions, both old and young loans and even the occasional native item (see back in (4)) (e.g., [arrujna] *[arrujɲa] ‘ruin’, [isilik] *[isiʎik] ‘quiet’).

Moreover, since HB’s rule palatalises all /n/ and /l/ after /i, j/ inside words, it also wrongly predicts the underapplication of palatalisation across words before C-initial words /in##C/ and /il##C/ (shown in (6b)) (e.g., /mutil + bet/ [mutil βet]*[mutiʎ βet]) ‘a boy’).

In order to account for the many lexical exceptions HB simply state that these are lexical exceptions. This is a perfectly common approach, but naturally it is an analysis which is subject to improvement if the exceptions can be explained in some way.

Meanwhile, to explain the underapplication of palatalisation before C-initial words, HB are forced to propose a Duke-of-York derivation. As illustrated in (7), the lexical rule applies palatalisation to these forms only to be corrected by a post-lexical nasal place assimilation and neutralisation rule.

| Derivation for /agin/ ‘tooth’ → *agiɲ and agin + bari → *agiɲ bari (part of HB p. 24) | ||

| /agin/ | /agin bari/ | |

| Palat. | agiɲ | agiɲ |

| N. Assim. | -- | agim bari |

| N. Neutr. | agin | -- |

| [aɣin] ‘tooth’ | [aɣim bari] ‘new tooth’ | |

2.2 Areas to improve on previous analysis

The HB account, we claim, misses two observations. Firstly, if analysed correctly, the palatalisation rule is actually exceptionless. There are in fact no exceptions in any loanwords young or old when it comes to word-final /in##/ and /il##/, across Basque morpheme boundaries. All the so called “exceptions” are word-internal. This fact is not captured if they are simply lexical exceptions.

| fusil ∼ fusille | [-ʎe] | ‘rifle’ | (uninfl ∼ ABS.SG) |

| guárdasibil ∼ guárdasibille | [-ʎe] | ‘Civil Guard’ | (uninfl ∼ ABS.SG) |

| fasil ∼ fasille | [-ʎe] | ‘easy’ | |

| automóbil ∼ automóbille | [-ʎe] | ‘car’ |

Secondly, and relatedly, the palatalisation rule can in fact be linked to the positional distribution of place features of nasals and laterals, as well as the process of nasal place assimilation across word boundaries.

An alternative account is possible based on the positional underspecification of nasals and laterals, and the spreading of place into derived onsets, those created by bipositional spreading of word-final codas into rightward vowel-initial morphemes (a.k.a. resyllabification). This analysis makes the place-feature distributions that result from the palatalisation alternations and relates them to Getxo Basque’s general rules of nasal place assimilation. The present paper argues that the advantage of such an analysis is that it can fully unify the so called “lexical exceptions”, as well as avoid HB’s Duke-of-York derivation and their necessary ordering stipulations between palatalisation and nasal place assimilation. Moreover, on this account, this process of Getxo palatalisation will no longer require a division between word- and phrase-level phonology; instead, it exploits other general phonological facts about the variety.

In the reanalysis we will show that palatalisation arises in a number of different contexts, but always results in the same bipositional palatal structure. Since Basque does not express phonological quantity as phonetic length, this bipositionality does not result in a phonetic geminate; instead, it is what has been referred to as a “virtual geminate” (see, e.g., Lowenstamm 1996; Ségéral and Scheer 2011). This structure has parallels in the palatalisation of other languages, and we will argue that once the full motivations are elucidated, the process is in fact exceptionless in Getxo Basque.

3 Reanalysis

3.1 Introduction to the framework

Since this analysis is couched in Strict CV (a strand within Government Phonology, GP – Charette 1991; KLV 1985, 1990) and Element Theory, we will present the tools of these frameworks for the unfamiliar reader.

3.1.1 Element theory

Element Theory (Backley 2011; Harris and Lindsey 1995; KLV 1985) is the theory of melodic representations operating with unary/monovalent/privative primes, primarily applied in GP, Dependency Phonology and Strict CV. Melodic primes are called elements, and they are generally seen as unorganised sisters beneath skeletal slots (though there are plenty of other analyses, some of which involve feature geometric organisation – see Balogné Bérces and Honeybone 2020: 4.1). The same feature set applies to both consonants and vowels (e.g., |I| can mark a natural class encompassing both /i, e/ as well as /j, ʎ, ɲ …/, while the element |U| can group together /u, o/ as well as /m, f …/). Depending on the model, consonants may have more internal structure: source features (|L|/|H| for voiced/voiceless, resp.) and manner features (e.g., the edge element |ʔ| or, in certain varieties of the model, nasality |N| – see, e.g., Harris and Lindsey 1995; Nasukawa 2005). A few illustrations are given below.

To the upcoming analysis, the most relevant aspect of Element Theory lies in its uniform treatment of palatality with reference to element |I|. Here we show the palatal set contrasted with the “coronal” set.

| Laterals, nasals and the triggers of palatalisation | |||||||

| C | C | C | C | C | V | ||

| | | | | | | | | | | | | ||

| R | I | R | I | I | I | ||

| ʔ | ʔ | N | N | ||||

| ʔ | ʔ | ||||||

| [l] | [ʎ] | [n] | [ɲ] | [j] | [i] | ||

Those familiar with Element Theory will notice that we represent coronality with rather “conservative” |R| (from the system typically associated with Harris and Lindsey 1995), rather than more recent |A| of “Revised Element Theory”. For the present analysis, it is of no theoretical significance which symbol one chooses as long as it is set apart from palatality, and |R| (referring to a consonant with a common coronal phonetic realisation) may be more transparent for readers less familiar with the framework. What is crucial to see, however, is that Element Theory identifies palatality in both consonants and vowels as the same melodic material (symbolised by |I|), and palatalisation will henceforth be modelled as the autosegmental spreading of this |I| from a V to a C.

3.1.2 Strict CV

Strict CV (Lowenstamm 1996; Scheer 2004; etc.) is an autosegmental framework where representations are composed of two main tiers, a melodic tier that holds segments/feature bundles and a skeletal tier. The skeletal tier is made up of strictly alternating C and V slots. The two tiers are connected by association lines.

Free combination of these two independent tiers yields the combinations in (10). These are the main shapes that exponents can take – according to the theory.

| Shapes of exponents | ||||||||||

| a. | Fixed | b. | Floating melody | c. | Empty skeleton | d. | Unfixed | |||

| C | V | C | V | C | V | |||||

| | | | | |||||||||

| α | β | α | α | Β | ||||||

Some of these possibilities might seem to be relatively abstract, however, these configurations follow from general autosegmental principles; namely, the independence of the tiers. If one wants to exclude any of these options it must be marked explicitly in UG. However, as Zimmermann (2017) observes, there is no reason to a priori exclude these configurations if they are useful in linguistic analyses. Very much in line with this, GP/CVCV as representational/autosegmental frameworks have utilised these devices ever since their inception, providing evidence of their theoretical inevitability: floating final consonants in French (e.g., Charette 1991) and English (e.g., Harris 1994); the floating melody of L1 suffixes (Balogné Bérces 1997; Newell 2021); an empty CV unit representing the word-boundary (Lowenstamm 1999) or stress (Larsen 1995); unfixed vowels (i.e., lexically specified vowels that are potential deletion targets – see (12) below) (Scheer 1998, 2004: 87–93 for Slavic; Polgárdi 2000 for Hungarian).

Our analysis will crucially rely on the configurations in (10b), (10c) and (10d): floating melody/floating segments (10b) and empty categories (10c), as well as unfixed/unlinked (10d), the combination of these two in which floating elements come with empty skeletal slots to which they are not associated. If a feature is not associated to the skeleton, it will not receive phonetic interpretation and be effectively “deleted”.

The strict contiguity of C and V slots means that vowel-initial and consonant-final words, long vowels, geminate consonants and consonant clusters all involve some kind of empty skeletal slot (see (11) below, with hypothetical examples). The interpretation of empty positions is constrained by universal principles and some parametric variation. Empty V-slots at the end of domains (FEN – “final empty nuclei”) and within domains are subject to different parameter settings since they can behave differently across languages (Charette 1990). Crucially to our analysis, certain languages, with Basque among them, license FEN by system-specific parametric choice, as a result of which they have surface consonant-final words (similar to the hypothetical form in (11a)).

|

Several types of clusters are distinguished in GP – the one that is relevant to the discussion below is the traditional “heterosyllabic”, “coda-onset” cluster, which in GP terms is the manifestation of right-to-left government between C1, the dependent/governee, and C2, the head of cluster/the governor. In (11c) above, such a cluster is illustrated, with the government relation between the consonants indicated by ←. Please note that for ease of reference, we continue to use some of the notions of traditional syllabic theory (in quote marks), e.g., “coda”, but those are only meant as descriptive, shorthand labels referring to the Strict CV equivalents (e.g., the “coda” is an (unlicensed) consonant followed by an empty V-slot – cf. /n/ in (11a) and /k/ in (11c)).

The structure in (12) illustrates the basic mechanism silencing empty V positions: V-to-V government (also called Proper Government – PG). In the most wide-spread form of GP it proceeds right-to-left, emanating from an unsilenced/filled V and having the result of satisfying the phonological Empty Category Principle (ECP) for the V-slot it hits.

|

Government is in Strict CV (to be precise, in a subtheory called Coda Mirror – Ségéral and Scheer 1999, 2001, etc.) conceived as a force that inhibits segmental expression of its target: in the case of nuclear positions, this amounts to granting it non-expression in phonetic realisation. In the Hungarian example in (12), V2 is an unfixed vowel: its empty V-slot can only remain empty (leaving the floating melody unlinked and hence phonetically unrealised) if the following V3 is filled and able to govern it (12b). Elsewhere, as in (12a), it is not silenced by government and will therefore need the floating melody to attach to it. Our analysis of the alternation between the absence and the presence of what HB call “glide absorption” (see the unabsorbed forms in (3) versus absorption in (1)) interprets the phenomenon as a case of vowel∼zero alternation similar to the Hungarian data, as such vitally hinging on the governing capacities of the following vowel.

According to Coda Mirror, the second of two antagonistic forces in phonology is licensing, whose function is just the opposite: to comfort segmental expression of its target (both definitions cite those in Ségéral and Scheer 1999: 20). In the analysis below, it will be crucial that filled/nonempty vowels are able to both govern and license (therefore, the preceding consonant will be licensed, and a preceding empty V may remain phonetically unexpressed – see V2 in bokrot in (12)), while the FEN (in Basque) is unable to either license or govern.

3.2 Distributional facts of place in Getxo Basque

We take the following facts and observe that place features are highly asymmetrically distributed in Basque. Word-final consonants are restricted to coronals (sonorants and voiceless obstruents)[4] – we interpret this as implying that word-final consonants are underspecified for place and coronal is the default specification. In addition, closed syllables in general do not permit place contrasts: “coda” laterals and nasals show strong place of articulation agreement effects with ensuing consonants (e.g., asal + ɟana [asaʎ ɟana] ‘eaten peel’, gison + barri [gisom bari] ‘new man’). This again indicates place underspecification, this time of “coda” laterals and nasals.

Place features of laterals and nasals are subject to many further asymmetries. As we have seen, the two coronal sonorants that are affected by palatalisation in Getxo are /n/ and /l/. Their palatal variants, [ɲ] and [ʎ] have this highly asymmetric place distribution. For historical reasons, as they developed from historical /n/ and /l/, they are vanishingly rare in word-initial position (with a few marginal counter-examples, e.g. interjection ño with [#ɲ] and the one single word with [#ʎ] lloba ‘nephew; grandchild’, which in fact alternates with illoba, see HB p. 7) or post-consonantally. Moreover, word-finally, the place of articulation of both /n/ and /l/ is neutralised to coronal, whereas, syllable-finally (incl. across words) both /n/ and /l/ take the place of articulation from the following consonant.

The syllable-final place assimilation process is somewhat more extensive for the nasal than for the lateral, which assimilates only to coronals (il + san [il san] ‘he died’) and palatals (asal + ɟana [asaʎ ɟana] ‘eaten peel’), but preserves its PoA before a labial or velar (mutil + bet [mutil βet] ‘a boy’; Algorta [alɡorta] ‘ibid. (place)’). This may be because the lateral is complex for place (see Backley 2011; Polgárdi 2019) – as this issue is beyond our present scope, we will take no stance regarding this aspect of melodic representation; we simply observe that only |I| and |R| (palatality and coronality) spread to the lateral, and it acts as a non-assimilating consonant when followed by a labial or velar.[5]

Therefore, these asymmetries make both sonorants restricted in their occurrence to the VCV environment, in which, accidental gaps aside, laterals and nasals are contrastive on the surface: [ama] ‘mother’, [sana] ‘vein’, [troɲu] ‘knot’.

As a consequence of the defective distribution and the palatalisation facts, HB chose to analyse the palatal nasal in every [Vɲ] sequence as deriving from underlying /Vin/, and every [VʎV] as derivable from /VilV/. As noted above, this leads to many “lexical exceptions” (recall the examples in (4) and the discussion in Section 2.2). However, from a surface perspective there are onset palatal laterals and nasals (e.g., [troɲu] ‘knot’). This fact is important since we link it to our reanalysis of palatalisation. Specifically, we note an apparently unnoticed generalisation in the so called “exceptions”: recall that word-finally there are no exceptions, not even in loanwords. All /in+V/, /il+V/ contexts produce alternations: /makin/ [makin] versus [makiɲa] uninflected versus ‘machine-ABS.SG’ and /fusil/ [fusil] versus [fusiʎ-e] uninflected versus ‘rifle-ABS.SG’.

We take this to mean that the exceptions (all exponent-medial and in onset/prevocalic position) are actually underlyingly palatal, whereas all /l/ and /n/ in non-prevocalic position (including all exponent-final instances) are underlyingly placeless and only gain coronality through it being the default place of articulation. This is expressed in Strict CV terms beneath, showing that in order to have a place feature, /n/ and /l/ must be licensed (i.e., hit from the right by the supportive/comforting force, as explained in Section 3.1.2 above).

| Place in /l/ and /n/ |

| Place distribution | |

| Place in LAT and NAS needs to be +Lic | |

| Or: Spread from a position that is +Lic | |

| Well-formedness requirement | |

| If LAT or NAS are +Lic, they need a place feature | |

| The default for both +Lic and −Lic: COR | |

These conditions mean that in Getxo the word-internal intervocalic position requires nasals and laterals with a place feature. In fact, all three place features are licensed in this position: bilabial /m/, alveolar /n/ and palatal /ɲ/ (e.g., ama ‘mother’, sana ‘vein’, troñu ‘knot’). The consonant (whose melodic make-up we ignore here and simply symbolise with N, a placeless nasal) is in +Lic position and is therefore able to maintain any of the available place elements: |U|, |R|, |I| – see (14).

| Place contrasts in licensed positions[6] |

|

In “coda” position, the nasal and lateral would not be able to be licensed because they precede an empty V-slot: the nasal (symbolised by N) and the lateral (symbolised by L) are underspecified for Place lexically – see (15a), where we indicate placelessness with empty brackets [ ]. However, in these positions, where possible, the nasal and lateral would obtain a place feature from place assimilation with the ensuing consonant (15b), which itself is in a licensed position. The only place of articulation available in coda position that does not result from spreading is the default place: Coronal, which eventually fills the underlyingly empty place [ ] (compare (15a) and (15c)).

Place in “coda” positions[7] |

Note that meanwhile, word-finally, the nasal and lateral would be before an empty nucleus, which cannot provide licensing to the position. As such, no underlying contrast in this (or in “coda” position) is permitted. The resultant effect is that word-finally all nasal and lateral consonants are underlyingly placeless.

The place they obtain will depend on their phonological environment, and it is these contexts that drive the alternations. In fact, from this perspective, the whole of cross-morphemic palatalisation is driven by the various ways in which these positions derive place.

3.3 Palatalisation across morphemes

Across morphemes these placeless word-final nasals and laterals are derived in various ways resulting in various phonological contexts. Returning to the cases that we list in Section 1, cross-morphemic palatalisation occurs in the following environments: with clitics and certain suffixes (within the word) and across words (before a vowel).

3.3.1 Clitics and suffixes

It is a commonly held view in representational (morpho)phonology that the exponents of functional items are structurally incomplete: they contain underspecified, unfixed or floating material, which very often accounts for the behaviour they exhibit and the modifications they impose on the root. As is apparent below, the present analysis heavily draws on this idea.

We start with vowel-initial clitics and suffixes (i.e., the data in (1) above). These vowel-initial forms contain floating melody, which docks to the final V-slot of the stem. Consonant-final stems have their final empty V-slot filled by this operation, whereas vowel-final roots (which contain an underlying vowel in their final V-slot), fuse with the suffix into the stem’s final V-slot, as in /neska + a/ [nesk-e] ‘girl-ABS.SG’. These suffixes are, in a sense, internal to the stem. We propose that the Strict CV mechanism for vowel-initial clitics and suffixes in Getxo is very similar to that used by, e.g., Balogné Bérces (1997) and more recently by Newell (2021) for L1 affixes in English.

The fact that V-initial suffixes float into the final V-slot of stems has a particular significance for Getxo given the place asymmetries described above because it means that the root-final /n/ and /l/ that are underlyingly placeless due to (13) go from being −Lic to +Lic and, consequently, now need a place feature. We propose that in these cases they gain it through palatalisation from the local palatal vowel and through the spreading of |I|. This process is shown beneath, taking [oɲé] ‘the foot-ABS.SG’ as a representative example. As shown in this derivation, the root vowel is a diphthong (a long vowel, regularly occupying a VCV sequence, i.e., two CV units, in Strict CV) whose second term is lexically floating (therefore C2V2 is underlyingly empty) – this floating palatal element is fully absorbed into the nasal or lateral’s C-slot upon palatalisation leading to “glide absorption” (16c and d).

|

As shown in (16a and b), a word-final nasal (an underspecified N) remains unlicensed and its place (lexically empty [ ]) is filled by default with the coronal element (the |R|). In contrast, when the affix is attached to the root-final V-slot (16c), the nasal finds itself in a +Lic position and, according to (13), it is now able to receive the |I| spreading from the left (16d). A more detailed exposition of glide absorption (and where it does not occur) will be discussed in Section 3.4.

The data in (2) illustrate that consonant-initial suffixes also participate in this cross-morpheme palatalisation process. We must propose that the initial consonants of these affixes are underspecified for place, unlike root-initial /n/ and /l/.[8] Whenever no other PoA source is available, the default will grant coronality eventually (17a and b); however, the consonant now sitting in a +Lic position can gain place by spreading from the left if an |I| is there (17c and d).

What is clear from both (16) and (17) is that the default mechanism supplying the coronal feature is indeed – as the name indicates – default, meaning that it is a last resort mechanism (default phonetic interpretation) and is unavailable as long as other modes of acquiring place are accessible. When the preceding vowel, however, does not contain |I|, this (originally) final/placeless sonorant is still doomed to remain placeless and be interpreted with the default PoA.

3.3.2 Place and palatalisation across words

Post-lexically, palatalisation only occurs before vowel-initial words because the consonant in C-initial words imposes its place feature on the root-final sonorant through the regular process of place assimilation whenever it can, i.e., for three places in nasals (spreading |U|, |R|, |I|) and two for laterals (|R| and |I|). Recall from Section 3.1.2 that according to our model, a “coda-onset” cluster involves a dependency relation between the two consonants: there is a dependent and the head of the cluster. The head of the cluster is in the licensed (prevocalic) position. In Getxo (and in many languages) this head imposes its Place feature on its dependent, leading to partial gemination/place assimilation – i.e., a bipositional configuration. In most cases, this relationship provides the placeless nasal and lateral with a place feature; as such it does not require one from palatalisation.

As long as the root-final consonant is followed by a FEN and then a filled C-slot, palatalisation is blocked even when the preceding vowel is palatal. When the lateral is unable to receive the place of the second consonant in a potential “coda-onset” cluster (as in (19)), it remains placeless – eventually filled with coronal by default.

| Preconsonantal palatalisation blocking |

| /mutil + bet/ → [mutil βet] (cf. *[mutiʎ βet]) „a boy‟ |

|

As we will see later, the representation in (19) is incomplete: part of the explanation of why palatalisation does not take place in such cases concerns the inability of the |I| to attach anywhere else but its V-slot. See (22) and (26) below.

Now we turn to vowel-initial words (see the data in (3) above). What makes a crucial difference is that vowel-initial words start with an empty C-slot. We assume that this forms a bipositional structure with the previous consonant: the ensuing configuration has the same properties as a “coda-onset” cluster (it is effectively a geminate – though Basque does not interpret it by phonetic duration), whose head is an empty C-slot. Being empty, it has no place of articulation, and neither does the final /n/ or /l/ have one underlyingly. In these cases, if an |I| element is available, it will spread into the bipositional construct, whose place feature comes from the palatalisation.

|

In (20), “Resyllabification” creates the same structure as the previous C1 and C2 in (18), a bipositional structure where the consonant now occupies a +Lic position. As a result, it cannot remain placeless: the palatalising feature |I| will spread into the bipositional complex. This unifies nasal and lateral place assimilation and cross-word palatalisation with the same structure, having the distinctive property of bipositionality. In Basque, bipositionality may produce underlying geminates because in this language (with the sole exception of Arbizu dialect), neither vowels nor consonants contrast phonetically for length.[11]

A significant element of the analysis lies in the drive that motivates the alternations: the unlicensed sonorants need Place and the one they obtain depends on their phonological context. As a result, the whole of cross-morphemic palatalisation (as well as, in fact, nasal/lateral place assimilation) is driven by the various ways in which these positions derive place.

In addition, it is worthy of note that under the present analysis, the differences in phonological behaviour of affixes and words as they are concatenated with the root is fully encoded in the phonological representation without any non-modular reference or diacritic. Following previous proposals like Balogné Bérces (1997) or Newell (2021) for English, Level 1 clitics and suffixes are marked by their phonological structure. On their left edge, the vowel is floating or the consonant is underspecified. In GP/Strict CV, V-initial words are also special, as they start with an empty onset. Given these representations, it comes as no surprise that such morphemes act as triggers of morpho-phonological processes.

3.4 The representation of vowels/diphthongs and glide absorption

Getxo Basque has a five vowel system, with /i, e, a, o, u/. In addition, it is said to contain four i-final diphthongs (/ai, ei, oi, ui/, which we represent as [aj, ej, oj, uj]) and two u-final ones (/au, eu/) (HB p. 9). From the perspective of the palatalisation process under discussion here, the relevant (trigger) vowels are /i/ (seemingly a short monophthong) and the i-final diphthongs.

HB argue that the diphthongs are derived by a rule that makes an unstressed high vowel into a glide immediately after another vowel (/Vi/ > [Vj]). In what follows, we accept this analysis: element |I| in an unstressed postvocalic V position is phonetically interpreted as a [j] offglide. We also make use of the following crucial facts (generally true in Basque): (i) the fifth i-final diphthong /ii/ (= [ij]) seems to be missing from surface forms; and (ii) neither vowels nor consonants contrast phonetically for length. These two facts are significant because, as shown in (21), a preceding /i/ triggers palatalisation in exactly the same way as [j]-final diphthongs do.

| Palatalisation by diphthongs and /i/ | ||||||

| UNINFL | ABS.SG | ‘big ADJ’ | ||||

| /oin/ | [ójn] | /oin-e/ | [oɲ-é] | /oin + andi/ | [ojɲ andí] | ‘foot’ |

| /mutil/ | [mutíl] | /mutil-e/ | [mutiʎ-é] | /mutil + andi/ | [mutiʎ andí] | ‘boy’ |

Consequently, we assume that the two have identical compositions: /i/ also has an offglide, i.e., it is also a long vowel (diphthong): /ii/ (the missing i-final vowel of the inventory).

In Strict CV terms, this means that all palatalising vowels share two common properties: (i) all occupy two V-slots (that is, a VCV sequence); and (ii) all have the second V occupied by an |I| element which serves as the second term of palatalising diphthongs as well as of the bipositional structure of the long /ii/. The examples in (21) can accordingly be modified as (21′). The apparent difference between (a) and (b) comes from the fact that in Basque, bipositionally linked melody is never interpreted phonetically as long. Underlying /ii/ is realised as [i]. Note, however, that phonologically the trigger vowels comprise the natural class of all V1CV2’s where V2 contains |I|.

| Palatalisation by diphthongs and /ii/ | ||||||

| UNINFL | ABS.SG | ‘big ADJ’ | ||||

| /oin/ | [ójn] | /oin-e/ | [oɲ-é] | /oin + andi/ | [ojɲ andí] | ‘foot’ |

| /mutiil/ | [mutíl] | /mutiil-e/ | [mutiʎ-é] | /mutiil + andi/ | [mutiʎ andí] | ‘boy’ |

Another apparent difference is found in how palatalisation is accompanied by glide absorption, which seems to follow either of two routes: if the vowel before the /n, l/ is /i/, plain palatalisation happens in all contexts (21/21′b); if it is any one of the i-final diphthongs, palatalisation takes place with absorption before a suffix/clitic and without absorption across words (21/21′a). If, however, glide absorption is conceived as i∼zero alternation, the difference disappears since both /i/ and /ii/ are interpreted as [i] so ii+L/N sequences as in /mutiil-e/ can undergo glide absorption without a visible trace on the surface.

Glide absorption, then, is but a form of vowel∼zero alternation, as it is understood in the GP tradition (and illustrated in (12) above) involving a floating element |I|. Therefore, we assume that glide /i/ is a floating |I| element, whose phonetic interpretation depends on whether its designated V-slot is silenced by Proper Government (in which case it is unable to dock onto it) or is left ungoverned (in which case |I| links to it to satisfy its ECP). This latter is what happens when the following consonant is word-final, as in (22). Since the FEN is unable to govern, |I| links to V2; the final sonorant remains monopositional and receives COR by default.

|

Moving now to the boundary between words where the second begins with a vowel, we see that in these strings, V2 is ungoverned just as it is in (22). This is because the V-slot that corresponds to VFEN in this string is silenced by V3 (a filled V-slot). The inability to silence V2 leads to the floating |I| surfacing in that position and the interpretation of a glide. For this reason, glide-absorption is blocked again.

|

As shown in (23b), since the second word starts with an empty C-slot (C3), a bipositional structure is created by spreading the final (palatalised) sonorant into C3.

In both these contexts, where a floating |I| is preceded by a FEN or a vowel-initial word, the V2 that would host the glide fails to be silenced. Crucially, this is different in affixation/cliticisation. As we have explained already in Section 3.3.1, we assume that suffixation involves the linking of a floating vowel to the final V-slot of the stem. If the stem is consonant-final (as with all the stems that undergo palatalisation), suffixation changes the status of the final V-slot. It goes from being a FEN to being a filled V-slot.

This change of status allows the final V-slot of the stem (when suffixed) to silence V2, the position that hosts the glide. This means that when a stem undergoes affixation, the V-slot that allows the glide to surface is silenced. The surface effect of this will be glide absorption but only in cases of suffixation.

|

It needs to be pointed out that, as argued above, /ii/ and the i-final diphthongs have parallel underlying representations, and as a result they contribute to the derivation of the output structures identically (compare /ii/ in (22) and /oi/ in (23–24)), therefore no separate illustrations are needed for the mechanisms leading to or preventing absorption with the two vowel classes. Also, the discussion above aims to shed light on the rather enigmatic earlier representations of the palatalising vowel with a floating |I| in (16) and/or [i] as VCV in (17), (19) and (20a) in the previous sections.

A further observation to make is that the palatal output is always a shared/bipositional structure (a virtual geminate),[12] but it comes in two different forms: it either branches to the right (on the initial empty onset of V-initial words – e.g., (20), (23)) and there is no absorption, or to the left (on the C-slot accessible because V2 was vacated by PG – (24)) and absorption ensues. It may even be claimed that the motor of the entire phenomenon is the government that determines the fate of the floating |I|.[13]

There is in fact one more situation in which this left-branching construction is derived: the palatalisation that takes place with [i/j]-final roots and underspecified initial sonorants in affixes. In (25) we give the updated version of (17c and d).

|

For a final illustration, let us consider cross-word place assimilation. As normal, in the cross-word situation, |I| links to V2 because this V-slot is not silenced. This leads to pronunciation of the glide (the lack of glide absorption).

In cases like /mutil + bet/ → [mutil βet] ‘a boy’ (cf. (19) above), where C-to-C place assimilation cannot happen but a palatalising vowel is available, nevertheless palatalisation will not take place (*[mutiʎ βet]) and instead we get a default. As shown in (26), the floating |I| cannot dock to the underspecified nasal or lateral in C3.

| Across a word before a non-assimilating consonant[14] |

|

This is because it would lead to a place of articulation in a non-licensed position (since V3 is silenced by government). Place of articulation is not permitted before a silenced V-slot (such as V3). Moreover, since (for independent reasons) the lateral does not assimilate to the Labial or Dorsal PoA, this source of Place is also denied to the consonant in C3 (shown with the blunted arrow end). As such, in this context the only option is the default PoA: coronal.

Instead, in this same context, where place assimilation is allowed (such as with a nasal and an ensuing stop), this is how the consonant in C3 obtains Place. This is possible because the Place of the ensuing stop is in a +Lic position and allowed to be part of the representation (which is not the case with rightward spreading into C3 from V2, so long as V3 is silenced). This outcome is shown in (27).

|

4 Conclusions

In this paper, we show that it is possible to produce an analysis of Getxo Basque palatalisation without invoking an architectural distinction between levels of the grammar (word, phrase) and the complications that this involves: many lexical exceptions and a Duke-of-York derivation. We identified a subregularity by noticing that although there are many exceptions within morphemes, there are no exceptions to palatalisation at the edges of morphemes. We proposed therefore to reanalyse the special pattern of palatalisation in Getxo Basque as one of the licensing of place of articulation. We proposed a general restriction on the distribution of Place features in the language, and the obligation for placeless consonant to gain PoA when in a +Licensed position (effectively an “onset”). The representations we proposed did not require a special word-level and phrase-level phonology, instead the surface outcomes only vary depending on what representations are computed by the phonology. The distribution of place that we propose holds generally in the language, and, from that, we correctly predicted the difference between vowel- and consonant-initial words in the language; as well as the contexts in which glide absorption applies and underapplies. This all led to an analysis of Getxo Basque palatalisation without lexical exceptions, without extrinsic rule ordering or a Duke-of-York derivation and without dedicated word-level and phrase-level phonological strata.

References

Backley, Phillip. 2011. An introduction to element theory. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.10.1515/9780748637447Search in Google Scholar

Balogné Bérces, Katalin. 1997. An analysis of shortening in English within Lowenstamm’s CV framework. In Zoltán Kiss, Ágnes Lukács, Balázs Surányi & Péter Szigetvári (eds.), The odd yearbook 1997. ELTE SEAS undergraduate papers in linguistics, 23–36. Budapest: Eötvös Loránd University (ELTE).Search in Google Scholar

Balogné Bérces, Katalin & Patrick Honeybone. 2020. Representational models in the current landscape of phonological theory. Acta Linguistica Academica 67(1). 3–27. https://doi.org/10.1556/2062.2020.00002.Search in Google Scholar

Charette, Monik. 1991. Conditions on phonological government. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511554339Search in Google Scholar

Faust, Noam, Nicola Lampitelli & Shanti Ulfsbjorninn. 2018. Articles of Italian unite! Explaining the shapes of Italian definite articles without allomorphy. Canadian Journal of Linguistics 63(3). 359–385. https://doi.org/10.1017/cnj.2018.8.Search in Google Scholar

Harris, John. 1994. English sound structure. Cambridge, Mass. and Oxford: Blackwell.Search in Google Scholar

Harris, John & Geoff Lindsey. 1995. The elements of phonological representation. In Jacques Durand & Francis Katamba (eds.), Frontiers of phonology: Atoms, structures and derivations, 34–79. Harlow, Essex: Longman.Search in Google Scholar

Hualde, José I. 1991. Basque phonology. London & New York: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Hualde, José I. & Xabier Bilbao. 1992. A phonological study of the Basque dialect of Getxo (Supplement 29 of Anuario del Seminario de Filología Vasca ‘Julio de Urquijo’). Donostia-San Sebastián: Diputación Foral de Gipuzkoa.Search in Google Scholar

KLV 1985 = Kaye, Jonathan, Jean Lowenstamm & Jean-Roger Vergnaud. 1985. The internal structure of phonological elements: A theory of charm and government. Phonology Yearbook 2. 303–328.10.1017/S0952675700000476Search in Google Scholar

KLV 1990 = Kaye, Jonathan, Jean Lowenstamm & Jean-Roger Vergnaud. 1990. Constituent structure and government in phonology. Phonology 7. 193–231.10.1017/S0952675700001184Search in Google Scholar

Larsen, Uffe Bergeton. 1995. Vowel length, Raddoppiamento Sintattico and the selection of the definite article in Modern Italian. In Léa Nash, Georges Tsoulas & Anne Zribi-Hertz (eds.), Actes du deuxiéme colloque Langues et Grammaire, vol. 8, 110–124. Paris: Université Paris.Search in Google Scholar

Lowenstamm, Jean. 1996. CV as the only syllable type. In Jacques Durand & Bernard Laks (eds.), Current trends in phonology: Models and methods, 419–442. Salford, Manchester: European Studies Research Institute, University of Salford.Search in Google Scholar

Lowenstamm, Jean. 1999. The beginning of the word. In John Rennison & Klaus Kühnhammer (eds.), Phonologica 1996. Syllables!?, 153–166. The Hague: Holland Academic Graphics.Search in Google Scholar

Nasukawa, Kuniya. 2005. A unified approach to nasality and voicing. Berlin & New York: Walter de Gruyter.10.1515/9783110910490Search in Google Scholar

Newell, Heather. 2021. Deriving level 1/level 2 affix classes in English: Floating vowels, cyclic syntax. Acta Linguistica Academica 68(1–2). 31–76. https://doi.org/10.1556/2062.2021.00501.Search in Google Scholar

Oñederra, Miren Lourdes. 1990. Euskal fonologia: Palatalizazioa. Asimilazioa eta hots sinbolismoa [Basque phonology: Palatalization. Assimilation and sound symbolism]. Leioa: Univ. del Pals Vasco.Search in Google Scholar

Polgárdi, Krisztina. 2000. A magánhangzó∼zéró váltakozás a magyarban és a “csak CV”-elmélet [Vowel∼zero alternation in Hungarian and the “strict CV” approach]. In László Büky & Márta Maleczki (eds.), A mai magyar nyelv leírásának újabb módszerei IV, 229–243. Szeged: SZTE.Search in Google Scholar

Polgárdi, Krisztina. 2019. Darkening and vocalisation of /l/ in English: An element theory account. English Language and Linguistics 24(4). 745–768. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1360674319000315.Search in Google Scholar

Scheer, Tobias. 1998. Governing domains are head-final. In Eugeniusz Cyran (ed.), Structure and interpretation: Studies in phonology, 261–285. Lublin: Wydawnictwo Folium.Search in Google Scholar

Scheer, Tobias. 2004. A lateral theory of phonology. Vol 1: What is CVCV, and why should it be? Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.10.1515/9783110908336Search in Google Scholar

Ségéral, Philippe & Tobias Scheer. 1999. The coda mirror. Ms: Université de Paris 7 & Université de Nice.Search in Google Scholar

Ségéral, Philippe & Tobias Scheer. 2001. La Coda-Miroir. Bulletin de la Société de Linguistique de Paris 96. 107–152.10.2143/BSL.96.1.503739Search in Google Scholar

Ségéral, Philippe & Tobias Scheer. 2011. Abstractness in phonology: The case of virtual geminates. In Katarzyna Dziubalska-Kołaczyk (ed.), Constraints and preferences, 311–338. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.10.1515/9783110881066.311Search in Google Scholar

Zimmermann, Eva. 2017. Morphological length and prosodically defective morphemes. (Oxford Studies in Phonology and Phonetics.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780198747321.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

© 2022 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Articles

- Cross-morphemic palatalisation in Getxo Basque: empty positions, bipositionality and place licensing

- Silent lateral actors: the role of unpronounced nuclei in morpho-phonological analyses

- On the properties of null subjects in sign languages: the case of French Sign Language (LSF)

- On the why of NP-Deletion

- Pre-field phobia – About formal and meaning-related prohibitions on starting a German V2 clause

- Embedded-complement and discontinuous pseudogapping in Hybrid Type-Logical Grammar: a rejoinder to Kim and Runner (2022)

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Articles

- Cross-morphemic palatalisation in Getxo Basque: empty positions, bipositionality and place licensing

- Silent lateral actors: the role of unpronounced nuclei in morpho-phonological analyses

- On the properties of null subjects in sign languages: the case of French Sign Language (LSF)

- On the why of NP-Deletion

- Pre-field phobia – About formal and meaning-related prohibitions on starting a German V2 clause

- Embedded-complement and discontinuous pseudogapping in Hybrid Type-Logical Grammar: a rejoinder to Kim and Runner (2022)