Abstract

This commentary paper is a response to the target article by Andreas Trotzke and Anastasia Giannakidou, who argue that neither exclamatives like How smart Anya is!, nor declarative exclamations like Anya is so smart! have a special, exclamatory illocutionary force, but instead are both semantically equivalent to declaratives that assert propositions about the speaker’s attitude like I am amazed at how smart Anya is with respect to not only their compositional structure, but even what is at-issue and what is presupposed. In this response, I defend a specific version of the more traditional view under which exclamatives express affect about presupposed content, declarative exclamations assert the content of the declarative with expression of affect “on the side”, and neither assert propositions about one’s attitude. I do so by challenging Trotzke and Giannakidou’s claims about the behavior of these different types of sentences in the discourse and by looking at a wider typology of exclamations within and across languages, with special focus on their prosody and more fine-grained aspects of meaning.

1 Introduction

In their thought-provoking target article, Trotzke and Giannakidou (hf. TG) argue that exclamatives like (1a) do not have a special illocutionary force, but, in fact, both exclamatives like (1a) and declarative exclamations like (1b)[1] are semantically equivalent to (1c) with respect to not only their compositional structure, but even what is at-issue and what is presupposed. Specifically, they argue that in all three cases, the speaker asserts a proposition about their attitude towards the presupposed proposition that Anya is smart to a high degree.

| How smart Anya is! |

| Anya is so smart! |

| I am amazed at how smart Anya is. |

In this response paper, I will challenge these claims and will defend the “standard” view – or rather a specific version thereof based on my own prior work (Esipova 2024a, 2024c, 2024d), whereby exclamatives like (1a) express affect about presupposed content, declarative exclamations like (1b) assert the content of the declarative with expression of affect “on the side”, and only sentences like (1c) assert propositions about one’s attitude. I start by laying out the conceptual and analytical underpinnings of this view in Section 2.

I then challenge the claims TG make about how exclamatives and declarative exclamations behave in the discourse, focusing on how they can be responded to (Section 3.1) and how they themselves can be used in responses (Section 3.2).

More specifically, I show that, contrary to what TG predict, the affect-related component of exclamatives like (1a) or declarative exclamations like (1b) does not behave in the discourse in the same way as the affect-related component of declaratives that assert propositions about attitude like (1c) – a comparison that TG simply don’t make. Under the “standard” view, these contrasts are expected because of the expressive nature of the affect-related component in (1a) and (1b) – in contrast to (1c), where it’s truth-conditional.

Regarding the ‘(the speaker/attitude holder believes that) Anya is very smart’ component, TG predict that it should behave as a presupposition in the discourse in all three cases, while the “standard” view predicts that it is asserted in (1b) and presupposed in (1a) and is technically neutral on (1c) (but it is in general common to assume that it is presupposed). However, instead of trying to show that this component behaves as presupposed, TG seem to want to show that it behaves like what is typically assumed for at-issue content, i.e., that it can be directly denied (at least by some denial forms) and can sometimes address questions. Once again, no systematic comparison is drawn with (1c). My ultimate conclusion is that while some of the “tests” they use can distinguish between expressive and truth-conditional content, they simply don’t do a very good job distinguishing between presupposed truth-conditional content and at-issue truth-conditional content.

Next, in Section 4, I look at a broader taxonomy of exclamations within and across languages, focusing on the distinction between exclamations that are subject to the degree constraint (i.e., they have to be about degrees) and those that aren’t, with special focus on their prosody and fine-grained meaning differences. Here I rely primarily on prior work in Nouwen and Chernilovskaya (2015) and especially Esipova (2024d). While I did myself claim in Esipova (2024d) that the second type of exclamations, i.e., those that are not subject to the degree constraint, are instances of embedding under a mirative predicate, I show here that the whole speech act in this case still cannot be treated as an assertion about attitude akin to I am amazed/surprised…, as the two don’t behave in the same way in the discourse either. I also conclude that careful investigation of prosody and fine-grained meaning differences is imperative for building descriptively and explanatorily adequate analyses of exclamations.

I then add a few further notes about intensity and affect in Section 5 and wrap up in Section 6.

2 In search of an exclamatory illocutionary force

One of the criticisms TG level against illocutionary operator approaches to exclamatives is that “they could not establish exactly what the exclamative illocutionary force might be”. So let’s try to clarify that. Rett (2011) defines the exclamatory illocutionary force operator as “a function from propositions to expressive speech acts”. While I depart from Rett’s work in various ways in Esipova (2024c, 2024d), I also maintain that in “true exclamatives”, the primary speech act is that of expression of affect. The notions of expressive and expression here need to be understood precisely, as non-truth-based expression of affect – and not just as any kind of affect-related meaning. The intuitive distinction between an expressive speech act versus an assertion of some affect-related meaning (“emotive assertion” in TG’s terms) is, thus, that of expressing one’s feelings versus talking about them, as illustrated in (2).

| {Ouch! / Damn! / Fuck! / Wow!} |

| {I am frustrated. / I am in pain. / I don’t like this. / I am surprised.} |

In both cases, we convey some kind of affect-related meaning. However, in (2a), we are expressing our feelings, while in the second case, we are communicating some factual information about them. Among other things, the utterances in (2a) cannot be intuitively thought about in terms of something that can be true or false while those in (2b) can. This, of course, affects how they function in the discourse.

In particular, the assertions in (2b) can be meaningfully contested despite their highly subjective nature; they are part of “cooperative information exchange”. Thus, it is natural to model the meanings of utterances like in (2b) in terms of their truth conditions and the part of the discourse they participate in as an interactive endeavor that trades in questions under discussion, proposals that can be accepted or rejected, etc. In Esipova (2024a), I therefore use the term “truth-conditional content” to refer to the type of meaning expressed in such utterances and will continue to do so here; TG use the term “descriptive content” to talk about the same thing.[2]

In contrast, the expressive utterances in (2a) cannot be contested. We can accuse someone of pretending to be in pain, angry, surprised, etc. in those cases, but we cannot accuse them of lying or saying something false. Despite that, the issue of how to model the meanings of utterances like in (2a) has been a subject of some debate.

Potts (2007) takes this intuitive distinction in (2) seriously, talks about its various empirical consequences, and aims to reflect it in his formal account, whereby expressives are a special kind of context-shifting expressions, which specifically alter the expressive parameter of the context. This expressive parameter c ɛ is essentially a ledger that tracks the affective states of the conversation participants of the input context of interpretation c (which itself is modeled as a tuple that also includes at least the speaker, time, world, and judge). Note that the entries in this ledger (called expressive indices) do not take the form of propositions or anything truth-based; they are instead modeled as triples, one element of which is a numeric value on an interval [−1, 1], reflecting the affective state of the judge towards some source.[3] Whether or not the exact formal set-up in Potts (2007) is the most optimal way to cash out the intuitions above is immaterial for the purposes of this paper; what matters is that this semantics makes expressive meanings fundamentally distinct from truth-conditional meaning.

Potts (2007) is in this respect a departure from Potts (2005), which treats expressives in the same way as supplements (such as appositives and “high” adverbs), namely as “conventional implicatures”. Importantly, “conventional implicatures” in Potts (2005) are a special kind of propositions, whose semantic type ends in a truth value – of a special, “CI” kind, but a truth value nonetheless. There have been subsequent attempts to reduce expressive meanings to some kind or other of truth-conditional, but not-at-issue[4] meanings, including “expressive presuppositions” in Schlenker’s (2007) response to Potts (2007). However, these attempts at reductionism are, to my mind, misguided. In Esipova (2024a), I provide further conceptual and architectural arguments[5] for maintaining the analytical separation between truth-conditional and expressive meaning, which I will not rehash here, but which inform my desire to maintain this analytical distinction as reflective of an actual cognitive distinction. I will thus presuppose this distinction throughout the rest of the paper.

Note that much of the literature on expressives, including Potts (2007) and Esipova (2024a), doesn’t focus on purely expressive utterances like in (2a), but on utterances with expressives that seem ostensibly integrated into the syntactic structure of larger utterances. In particular, in Esipova (2024a), I focus quite a lot on the distinction between expressives like damn or fucking integrated into larger utterances and evaluative, but truth-conditional modifiers like lovely or disgusting:

| Lea might bring her {fucking / damn} dog. |

| Lea might bring her {lovely / disgusting} dog. |

Once again, without rehashing any of the empirical arguments from that paper, if we use a Potts (2007)-like set-up, the analytical distinction between (3a) and (3b) is that modifiers like lovely or disgusting are regular properties of individuals, albeit subjective,[6] that contribute to the truth conditions of the whole utterance, even if their contribution can be vacuous in a given context (e.g., for (3b) that will be the case if Lea only has one dog), making these modifiers not-at-issue (see Esipova (2019a) on my take on such not-at-issue – non-restricting – modifiers, where the restricting versus non-restricting distinction is argued to be purely pragmatic). In contrast, expressives like fucking or damn in (3a) simply alter the expressive parameter of the context without affecting the truth-conditional content at all.

Now, let’s go back to exclamatives. In Esipova (2024c), I explicitly “distinguish between exclamatives as a special sentence type, which have a specialized syntax and constitute expressive speech acts”, as in (4a), “and a broader descriptive category of exclamations, which are utterances of any type that appear to express affect, whether it is their primary purpose or not”, as in (4b) – a distinction that I will maintain throughout this paper.

| How smart Anya is! |

| Anya is very smart! |

Rett (2011) also makes a similar terminological distinction. However she pushes back against the idea, brought up by a reviewer, that in exclamations like (4b), the primary speech act is that of assertion, but there is also a secondary speech act of “exclamation or expression”. She specifically seems to take issue with the idea that in exclamations like (4b), exclamation is an “indirect speech act”, similar to how Can you pass me the salt? is interpreted as a request. Her point is that the force of exclamation is necessarily signaled intonationally in (4b), and without the relevant prosodic pattern(s), it would just be a regular assertion.

While I agree that the exclamation component of cases like (4b) is likely not equivalent to the interpretation of Can you pass me the salt? as a request,[7] and I certainly agree that this expression of affect is in no way “indirect”, I do maintain that the primary function of exclamations like in (4b) is that of assertion, and the various affect-signaling prosodic modifications are not unlike fucking or damn in (3a) in that they make expressive contributions “on the side”, in a way, “parasitizing” on the “host” utterance. One difference between the two is that expressives like fucking or damn do seem to be syntactically integrated into their “host” utterances,[8] while the prosodic modifications like in (4b) are ostensibly only integrated into the “host” utterance prosodically – although this distinction doesn’t matter much for our current purposes.

We can now operationalize this distinction between exclamatives like (4a) and declarative exclamations like (4b), using the Potts (2007)-style set-up described above. The exclamation in (4b) asserts the proposition ≈‘She is very smart’, and the prosodic modifications alter the expressive parameter of the context to reflect the speaker’s affective state, similarly to how fucking or damn do in (3a). The exclamative in (4a) then has a left periphery operator – an illocutionary force operator, one might say – which takes its sister as an argument and alters the expressive parameter of the context to reflect the speaker’s affect with the denotation of the sister being the source of said affect.

Now, so far, this is largely compatible with Rett’s (2011) idea that I started this section with that the exclamatory illouctionary force operator, E-Force, is “a function from propositions to expressive speech acts”.[9] However, in Esipova (2024d), I argue that in exclamatives like (4a), the argument of the E-Force operator is not a proposition, but a definite description of degrees. In fact, I argue that wh-exclamatives like (4a) are instances of expressive degree intensification, akin to (5a) – and, perhaps even more obviously, (5b), where intensification is done prosodically and/or via facial expressions and potentially other types of gesture, as well as (5c), where the expressive intensifier appears to have been promoted to the left periphery with its expressive component ostensibly becoming the primary speech act.

| Anya is damn smart! |

| ≈‘Anya is very smart + I am expressing feelings on the side’ |

| Anya is [sssmmmaaart]prosody+face-intensification! |

| ≈‘Anya is very smart + I am expressing feelings on the side’ |

| Damn {Anya is / is Anya} smart!10 |

| ≈‘I am expressing feelings about the very high degree to which Anya is smart’ |

- 10

Note that this utterance is meant to be prosodified as a single Intonational Phrase.

I discuss expressive intensification (across channels) at length in Esipova (2019a, 2019b, 2024a), but the main idea is that expressive intensifiers like damn have both a truth-conditional component (the degree intensification proper) and an expressive component (they still express affect performatively, i.e., by virtue of being produced). I furthermore propose a demonstration-based[11] analysis of the intensification component in expressive intensifiers, whereby, e.g., damn as an expressive intensifier combines with a property of degrees and modifies it by essentially saying that an instantiation of the degrees it describes would warrant the use of the form “damn”.

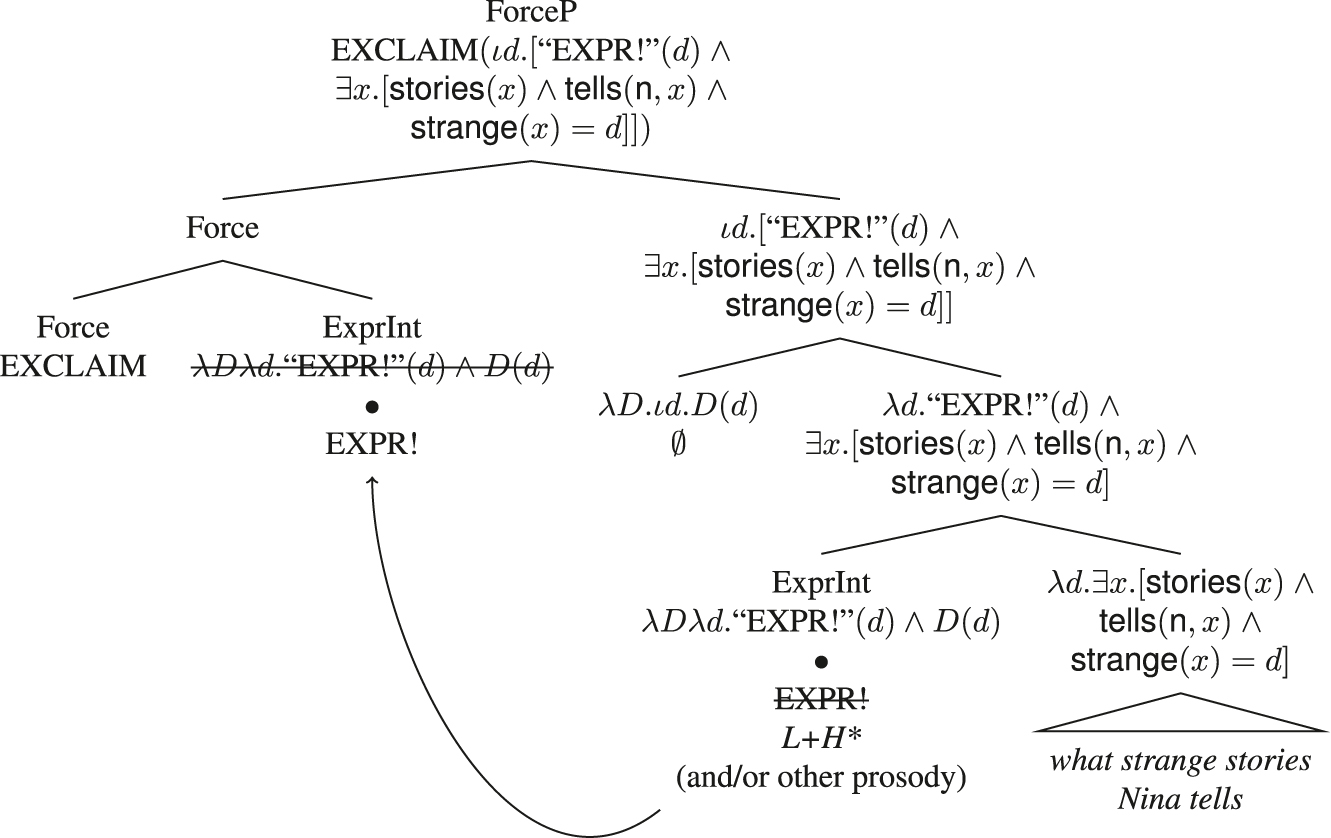

The specific implementation of the idea that exclamatives are instances of expressive intensification that I sketch in Esipova (2024d) is very simplistic. In Esipova (2024c), I propose a more detailed implementation[12] of compositional derivations of English versus Russian wh-exclamatives, Russian counterparts of (5a) versus (5c), as well as English nominal exclamatives – with an explanation of why Russian does not have English-style nominal exclamatives. I will not rehash the full analysis here, but in (6), I provide a derivation of the exclamative What strange stories Nina tells! from Esipova (2024c) (once again, the term “expressive speech act” needs to be understood within the Potts (2007)-style set-up described above).

|

| (An expressive speech act about the “EXPR!”-worthy degree to which some stories that Nina tells are strange. ExprInt moves into the Force projection, and the act of producing its prosodic exponent performatively realizes the EXCLAIM force. EXPR! = “expressive speech act”; “EXPR!”(d) means that an instantiation of d warrants an “EXPR!” reaction.) |

The derivation in (6) is explained in further detail in Esipova (2024c), but the gist is as follows. The wh-constituent in English wh-exclamatives denotes a property of degrees (here, it’s degrees to which some stories that Nina tells are strange). Then it combines with an ExprInt projection, which hosts a prosodically exponed expressive intensifier that has both a truth-conditional intensification component, as well as an expressive speech act component. The d variable is then bound by the iota operator, and eventually, the ExprInt head moves into the Force projection on the left periphery to make the expressive component of the expressive intensifier the primary speech act, while the intensification component remains interpreted low. The final result is thus an expressive speech act about the exclamation-worthy degree to which some stories that Nina tells are strange (≈‘! at the “!”-worthy degree to which some stories that Nina tells are strange’).

One of the motivations for adopting the expressive intensification analysis of exclamatives is to account for the degree constraint from Elliott (1974) and Rett (2011) (a.o.), i.e., the requirement that exclamatives be about degrees, as well as the fact that those degrees have to be “extreme”, in an at least somewhat explanatory way. Note that under the analysis in Rett (2011), there is no obvious reason why the proposition argument of E-Force has to be about degrees, let alone extreme ones. TG stipulate the presence of a degree intensifier in exclamatives, but in a way that I believe is insufficiently explanatory – an issue that I briefly come back to in Section 5.

The upshot of this section is that the exclamatory illocutionary force can, in fact, be grounded in a principled way in the notion of expressiveness. The question is, however, if it should be. In the rest of this paper, I will respond to the discussion in TG of how different types of exclamations function in the discourse and will look at a broader typology of exclamations – all in the context of the conceptual and analytical underpinnings laid out in this section.

Before we proceed, let me briefly go back to the terminological note I made at the outset in fn. 1 and reiterate it in view of the discussion above. Throughout the paper, I will continue using the term exclamation in the broad, descriptive, theory-neutral sense to refer to “utterances of any type that appear to express affect, whether it is their primary purpose or not”, encompassing, in particular, both How smart she is! and She’s so smart!. I will reserve the term exclamative for the special sentence form type (in contrast to declarative, interrogative, etc.), as in How smart she is!, but not She’s so smart!. And, as has been clarified in this section, I will maintain that exclamatives do, in fact, have expression of affect as their primary purpose – which aligns with their specialized syntax. I will similarly keep using the term declarative exclamation for sentences like She’s so smart!, even though I think their primary purpose is assertion of propositional content, not expression of affect.

3 Exclamations in the discourse

Under the view laid out in the previous section, exclamatives constitute expressive speech acts, but these are expressive speech acts about some truth-conditional content (a.k.a. “descriptive content”, which, again, is the term used by TG). However, this truth-conditional content is packaged as a presupposition (under the view in Esipova (2024c, 2024d), it is more specifically the existence presupposition of the definite degree description – i.e., that there exists a “!”-worthy degree described by the prejacent). This should affect how they function in the discourse. In particular, the expressive part itself is non-truth-conditional and should, therefore, be unable to make proposals/address questions or be reacted to in a way truth-conditional content can. The presupposed part is truth-conditional, but not-at-issue and should, thus, have a limited ability to make proposals/address questions or be directly denied in comparison to at-issue truth-conditional content, although this contrast is not always categorical (see, e.g., Koev (2018) for an overview).

TG claim that exclamatives like (7a) do not meaningfully differ from either declarative exclamations like (7b) or declaratives with embedding under an emotive predicate like (7c) with respect to their discourse behavior – and, therefore, there is no evidence that they meaningfully differ in their semantics.

| How smart Anya is! |

| Anya is so smart! |

| I am amazed at how smart Anya is. |

In this section, I will discuss TG’s claims by challenging either the claims themselves or the conclusions drawn from them. Most importantly, I will show that the affect-related component of exclamatives like (7a) or declarative exclamations like (7b) does not, in fact, behave in the discourse in the same way as the affect-related component of declaratives about attitude like (7c) – a comparison that TG simply don’t make. With respect to the ‘Anya is very smart’ component from (7), the discussion is more involved, but ultimately, I will conclude that the tests TG use simply don’t do a very good job distinguishing between presupposed truth-conditional content and at-issue truth-conditional content.

3.1 Denials

Under the “standard” view, neither the affect-related, nor the truth-conditional content of exclamatives like (7a) can be directly denied – the former being expressive and the latter being presupposed. As for declarative exclamations, their affect-related content can’t be directly denied either, also by virtue of being expressive (whether it’s primary or secondary is irrelevant), but, under my version of the “standard” view as laid out in the previous section, their truth-conditional content should be able to be directly denied. In Section 2.2 of their paper, TG agree with the common consensus regarding the affect-related content, but challenge it with respect to the truth-conditional content. Let’s review both claims in turn.

First, it is actually entirely unclear why, under TG’s proposal, it would be impossible to directly deny the affect-related content of either exclamatives or declarative exclamations, as illustrated in (8), considering that they claim that’s exactly what is being asserted in these cases. They write, following Castroviejo Miró (2008), that this must be because “the speaker’s emotional state cannot be denied”. But the problem is that the speaker’s “emotional state” can very well be denied in response to assertions that contain regular truth-conditional predicates like amazed or surprised, as shown in (9). B’s responses in (9) might sound rude or overstepping, but they are by no means infelicitous in the same way as they are in (8).

| {How smart Anya is! / Anya is so smart!} |

| #{That’s not true, you’re not emotional. / You’re lying, you’re not emotional. / No, you aren’t emotional.} |

| I am {amazed at / surprised by} how extremely smart Anya is. |

| {That’s not true, you’re not {amazed / surprised}. / You’re lying, you’re not {amazed / surprised}. / No, you aren’t {amazed / surprised}.} |

Of course, since the emotive predicate TG posit in exclamatives is phonologically null,[13] denial forms that rely on the presence of an overt predicate like No, you aren’t <amazed> would be expected to be out, but why would other denial forms be infelicitous? Note that it also doesn’t matter how exactly we formulate the continuation of those denials (You’re not emotional, You don’t have strong feelings about how smart Anya is, etc.) – as I already noted in Section 2, you can accuse one of pretending in response to expressive speech acts (or any expressive acts, like punching a wall), but you can’t accuse them of lying or saying something false.

As for TG’s claim that the truth-conditional content of exclamatives (e.g., that Anya is very smart in (7a)) can be denied, let me simply point out that under both the “standard” and TG’s views, this content is presupposed. TG specifically claim that this is a subjective veridicality presupposition, the same one that emotive predicates have, i.e., that the attitude holder/experiencer, not the speaker, believes the content of the complement to be true – but since in exclamatives the speaker is always the attitude holder/experiencer, this does not really matter. Thus, both approaches actually make the same predictions, so I am not entirely sure what TG’s argument here is: either both approaches are incorrect, or we simply have to admit that at least some presuppositions (and some types of not-at-issue content more broadly) can, in fact, be targeted by some direct denial forms – which, in principle, they can be. It could be, of course, that there is a substantial difference in the felicitousness of B’s response in (10)[14] versus (11) (there isn’t for me, both sound OK-ish), but then both approaches have some explaining to do.

| Lea’s bringing her dog. |

| No! Lea doesn’t have a dog. |

| How smart Anya is! |

| No! She’s not smart. |

In this respect, it is also worth noting that the denials TG look at in Section 2.2 of their paper feature simple No/Nah! utterances (and their Greek counterparts), followed by some kind of correction. TG themselves admit that these are general-purpose denials and can be used, e.g., in response to imperatives – so it stands to reason that they can also be used to deny at least some types of presuppositions.

Note also that under the “standard view”, exclamatives do not have an at-issue meaning component – in contrast to, e.g., utterances like A’s assertion in (10), which has both a not-at-issue and an at-issue component, so if there is a difference between (10) versus (11) or for more direct denials, as in (12) versus (13) (which there isn’t for me), it could be simply because there is a preference to interpret a denial as targeting the at-issue part of the utterance, but in the absence of one, there is no competition.

| Lea’s bringing her dog. |

| That’s not true! Lea doesn’t have a dog. |

| How smart Anya is! |

| That’s not true! She’s not smart. |

Let me also note that I am quite confused about what TG write at the end of Section 2.2: “Additionally, why should we postulate a factivity presupposition to account for the descriptive content of exclamatives (…)? Since no one to date has proposed that we need factivity presuppositions to account for the descriptive contribution of declarative exclamations (…), such an approach would also be on the wrong track.” But they do, in fact, treat the descriptive a.k.a. truth-conditional content of both exclamatives and declarative exclamations as presupposed (again, the difference between the factivity and the subjective veridicality presuppositions is immaterial here, as the experiencer is always the speaker themself) – even though they have been trying to show that both can be directly denied throughout the subsection. So I am not entirely sure how to interpret this passage or indeed what we are supposed to conclude from the whole subsection.

Regardless, if there is no meaningful difference between, say, (10) and (11), the point is moot: such denials are simply not an appropriate “test” then to distinguish between presupposed truth-conditional content and at-issue truth-conditional content.

3.2 Addressing questions

Next, let’s turn to whether exclamatives can be used to address questions – which is another common way to conceptualize and “test for” at-issueness (again, see Koev (2018) for an overview). What exactly it means to address a question is debatable, but let’s assume for simplicity something like the notion of relevance to a question from Simons et al. (2010), whereby a proposition p is relevant to a question Q iff, when assumed to hold true, p modifies the likelihood of at least one alternative in the denotation of Q.

As I said above, under the “standard” view, the affect-related content of an exclamative should not be able to address any questions by virtue of being expressive, and its truth-conditional content should have a limited (but again, not completely zero) ability to do so by virtue of being presupposed. Note, once again, that with respect to the latter, the “standard” view and TG’s view actually make the same predictions. With respect to the former, TG actually predict that the affect-related content of their exclamatives should be able to address questions to the same extent as that of declaratives with truth-conditional emotive predicates like amazed.

Before we assess these predictions, let’s first acknowledge that there are various ways to react to questions that would likely be judged coherent/felicitous by many speakers that do not actually address the question. In fact, TG mention it themselves and bring up rhetorical questions used as felicitous responses to questions, but this just reminds us that we should exercise caution when drawing any conclusions from the “question–answer test”. Thus, B’s response in (14) doesn’t actually address A’s question. Instead, B expects A to do some pragmatic reasoning by recognizing that the answer to B’s rhetorical question is ‘yes’ and that it is, furthermore, obvious – and then, by presumably evoking ‘Be relevant!’, A should establish that this is also the case for A’s question.

| Is Axel late? |

| {Does a bear shit in the woods? / Is the Pope Catholic? / Is the sky blue?} |

Similarly, if someone asks you about your emotional state, you directly address their question by asserting a relevant proposition, like in (15B), or you can respond to it indirectly by expressing your feelings, in a “show, don’t tell” kind of fashion, like in (15B′). There is no reason to believe that there is any proposition being asserted in (15B′) that could address any question (the demonstration-based mechanism of turning expressive content into truth-conditional content I mentioned above is not without its limits), but all these seem like coherent responses to A’s question, as A can presumably infer how B is feeling based on their expressive acts (speech or otherwise).

| How are you feeling? |

| I am frustrated. |

| {Screw this! / AAAAAAAAAAAAA! / *punches a wall*} |

With this in mind, it wouldn’t be surprising if an exclamative in response to a question about one’s emotional state was at least somewhat felicitous, even if it doesn’t actually address the question. Even with that in mind, I still do get a pretty strong contrast between (16B) and (16B′). (16B″) sounds like it is just confirming the antecedent assertion, perhaps with extra emphasis, but it doesn’t actually address the question about B’s feelings.

| Ivy is extremely strong. How do you feel about this? |

| I am amazed at how strong she is. |

| ??How strong she is! |

| ??She’s {very / so / damn} strong! |

Puzzlingly enough, TG do not look at cases like (16B) versus (16B′) versus (16B″), even though they predict that they should be equivalent.

Instead, they look at questions about the truth-conditional content of exclamatives and declarative exclamations. Now, again, they treat the truth-conditional content of exclamatives – e.g., that Ivy is strong to an extreme degree in (16B′) – as presupposed, so they do, in fact, make the same predictions here as the “standard” analysis, namely, that its potential to address questions should be limited in the same way as that of presuppositions.

The fact of the matter is, however, that some presuppositions can be used to address questions to at least some extent, so we’re once again dealing with an imperfect “test”. Thus, what ostensibly happens in both (17) and (18) is that B packages answers to A’s question as presuppositions (that B had smoked prior to stopping and that Ash has a spouse, respectively) – presumably, in hopes that A will be able to easily globally accommodate these presuppositions, so B can already make new at-issue proposals in their responses.

| Have you ever smoked? |

| I stopped last year. |

| Is Ash married? |

| They are bringing their spouse to my party tomorrow. |

Now, TG claim there is an empirical difference between questions about the degree (e.g., How fast was Eliud Kipchoge?) and broader questions (e.g., Tell me, how did Eliud Kipchoge do in the race?) – which they claim follows from their analysis. Setting aside their empirical claims for now, I am not sure I see how this contrast follows from their analysis, under which the whole proposition ‘Eliud Kipchoge was fast to an extreme degree’ would be presupposed by the exclamative How fast Eliud Kipchoge was! and should, thus, behave similarly to other presuppositions with respect to its potential to address questions – a prediction that is once again shared with the “standard” account. Why would there be a difference between the narrower and the broader question?

Now, let me note that I do, in fact, think that answering questions about degrees with expressive intensifiers is in general a marked strategy – perhaps because they are highly subjective, even more so than something like very or extremely, and, thus, not particularly informative and/or because you need to justify the expressive component (even if it’s secondary) in response to a neutral question – or at least prepare the addressee for it somehow. However, I still do not share TG’s intuitions for their (16′), repeated below with some adjustments as (19) – and neither do the native English speakers I asked. According to our judgements, contrary to what is reported in TG, the answer in (19B′) is not as degraded as in (19B), as long as they are prosodified appropriately (which includes, in particular, prominence on so), and the one in (19B″) is perfectly fine. And, of course, there is nothing wrong with (19B′′′), even if it is produced with “exclamatory intonation”.

| How tall is John? |

| ??How tall he is! |

| He is SO tall! |

| Oh boy… SO tall! |

| He is very tall! |

By the way, now is also a good time to note that I was in general confused by TG’s discussion of information-structure-related issues. In addition to the purported contrast between “broad” and “narrow” questions above, which I do not know how it follows from their analysis, on p. 40 of their paper, they also write that in exclamatives, “the speaker’s amazement is not given, but asserted, according to our analysis, via the underlying syntactic structure”. But just because the speaker’s amazement is not necessarily given does not mean that it can’t be. In fact, if exclamatives have the same semantics as declaratives with emotive predicates, the speaker’s amazement should be able to be given. Both the exchange in (21) (the speaker’s amazement is new information) and the one in (20) (the speaker’s amazement is given) are entirely felicitous.

| How do you feel about Anya being extremely smart? |

| I am amazed {that Anya is so smart / at how smart Anya is}. |

| What is it that you’re amazed about? |

| I am amazed {that Anya is so smart / at how smart Anya is}. |

The main overarching conclusion of this whole section is, thus, that TG failed to show that the affect-related component of exclamatives and declarative exclamations is truth-conditional and at-issue and behaves in the discourse in the same way as the affect-related component of utterances like I am amazed at… – which is the main prediction that sets their proposal apart from the “standard” analysis. In fact, it appears like the opposite is the case empirically. Instead, TG focused primarily on the truth-conditional component of exclamatives (with respect to which they make the same predictions as the “standard” analysis) and declarative exclamations. They predict this component to behave as presupposed in the discourse in both cases. However, if anything, the empirical picture they paint in their Section 2 suggests that this component behaves as at-issue – although the more accurate interpretation of their data is that the “tests” they use simply are not always appropriate for distinguishing between at-issue truth-conditional content and presupposed truth-conditional content.

Wrapping up this section, I would also be amiss not to note that one of the standard conceptions of at-issueness is based on projective behavior, i.e., the potential or lack thereof of a given piece of content to interact with the semantic operators in whose syntactic scope it appears. Of course, exclamatives cannot be embedded in the same way that I am amazed/surprised/etc. that/at… can.[15] Thus, the examples in (22) (which show that the speaker’s amazement is indeed at-issue or at least can be) cannot be replicated with exclamatives – which remains unexplained under TG’s account, but which is expected if they constitute expressive speech acts.

| It’s not true that I am amazed at how smart Anya is. |

I am amazed (at how smart Anya is). I am amazed (at how smart Anya is). |

| Cas {wants to know if / doubts that} I am amazed at how smart Anya is. |

I am amazed (at how smart Anya is). I am amazed (at how smart Anya is). |

| Whenever I am amazed at how good a movie is, I stay till the end of the credits. |

I am amazed (at how good a movie is). I am amazed (at how good a movie is). |

Declarative exclamations like It is snowing! cannot be embedded either, presumably because they are still carrying secondary expressive speech acts. That said, declaratives with at least some expressive intensifiers can be emdedded to at least some extent. In fact, in Esipova (2019a, 2019b, 2024a), I use this to argue that their intensification component is typically at-issue, which is a general property of degree modifiers (see more examples, including naturalistic ones in the papers cited). For example, in (23), all the intensifiers non-vacuously affect the truth conditions of the utterance.

| Whenever a movie is {very good / damn good / ggoood}, I stay till the end of the credits. |

Whenever a movie is good, I stay till the end of the credits. Whenever a movie is good, I stay till the end of the credits. |

TG could say that the reason why exclamatives cannot be embedded is because the attitude predicate they posit is null, but it’s not like null elements cannot occur in embedded environments in general, so ideally, they would need to show that (i) other independently motivated cases of what they call “null CPs” exist, (ii) they are similarly unembeddable.

4 Typological complexity of exclamations

On pp. 18–19 of their paper, TG write: “we would like to point out that our main goal in this paper is not to highlight cross-linguistic differences between various ways of how languages express exclamations. Quite the contrary. We discuss the Greek patterns (and later in Section 4 data from German) because we think that the morphosyntax of exclamations in those languages overtly instantiates relevant features of exclamations that, according to our approach, tell us something about the domain of exclamations more generally and across languages”.

I will have to disagree with what I take to be the spirit of this passage. I believe that “morphosyntactic” and other observable differences between different types of exclamations within a single language and across languages can very well indicate that the exact syntactic and semantic structure of these different types of exclamations is actually different. In this section, I will specifically focus on a contrast that TG gloss over at several different points in their paper, illustrated in (24). This contrast instantiates the degree constraint (Elliott 1974; Rett 2011), briefly mentioned above, which says that exclamatives have to be about degrees, i.e., positions on an ordered scale, supplied overtly or covertly. In other words, you can exclaim (24a) to express affect about the very high degree to which she is smart or the very high degree the story you are talking about has on some implicit scale. However, you cannot exclaim (24b) to express affect about the person who came or the fact that they came.

| {How smart she is! / What a story!} |

| * Who came! |

| It is surprising who came to the party. |

| Look who came to the party! |

Overall, TG say a few confusing things about this constraint throughout the paper. On the one hand, they seem to want to account for it, although how they do that appears stipulative to me (more on this in Section 5). On the other hand, they downplay it, by saying, for instance, the following in fn. 20 of their paper about the acceptability of (24d): “[t]hese speak to our earlier point in 2.3 that in richer contexts the data improves”. But the contrast between (24b) and (24d) is not that of a “richer context” – the latter clearly involves embedding under look, and if (24a) has a similar structure to (24c) (or (24d) for that matter) in English or in any other language where wh-exclamatives obey the degree constraint, it is entirely unclear why (24b) is bad.

Nouwen and Chernilovskaya (2015) claim that in some languages, such as Dutch, you can, in fact, exclaim segmental strings like ‘Who came!’ (TG cite this paper, but do not engage with this claim). Interestingly enough, they also claim that in Dutch, while exclamations like ‘How smart she is!’ can have either V2 or verb-final word order, associated with matrix and embedded clauses, respectively, exclamations like ‘Who came!’ can only be verb-final. This at the very least suggests two different syntactic structures for exclamations. One (Type 1) (i) does not ostensibly involve embedding and (ii) is subject to the degree constraint and is, thus, only available for exclamations like ‘How smart she is!’ and unavailable for exclamations like ‘Who came!’. The second one (Type 2) (i) does ostensibly involve embedding and (ii) is not subject to the degree constraint and is, thus, available to both ‘How smart she is!’ and ‘Who came!’. Nouwen and Chernilovskaya (2015) also review the use of the different wh-items in Dutch and German in both types of exclamations and eventually conclude that “syntactically, type 1 exclamatives involve non-standard wh-constructions, whereas type 2 exclamatives more accurately resemble questions” (note that they call both types “exclamatives”, because they are not willing to commit to the idea that only Type 1 exclamations are “true exclamatives”).

While Nouwen and Chernilovskaya (2015) also claim that German has both types, they do not provide detailed word order data.[16] It is, thus, quite puzzling to me that TG do not talk about the Type 1 versus Type 2 distinction in German at all. They do bring up that there is word order variation in German exclamations, but they claim that “unambiguous exclamatives in German always feature embedded (i.e., verb-final) word order”, because the alternative word order is also attested in matrix wh-questions. I find this point very confusing, because, first, as far as I can tell, even the surface strings aren’t actually ambiguous – the segmental material might be, but exclamations and matrix wh-questions have different prosody, which cannot and should not be swept under the rug. Note that TG write that “the only syntactic configurations that unambiguously express the exclamation” are with the “embedded” word order, but what they mean is segmental strings, not syntactic configurations: different prosodic contours can and presumably do in this case correspond to different syntactic structures. Second, why would the fact that the same segmental string can be used in matrix wh-questions matter? Just because a segmental string is compatible with being a matrix wh-question does not mean that it can’t also be compatible with being an exclamative. Is the claim here that these exclamations are actually syntactically and, therefore, semantically matrix wh-questions? It does not seem like it, so why should this case be ignored?

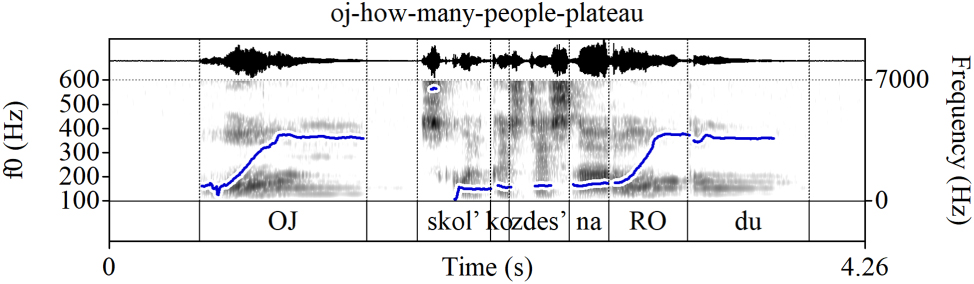

Going back to Type 1 versus Type 2 exclamations cross-linguistically, in Esipova (2024d), I look at this distinction in Russian. More specifically, I look at two aspects of this distinction that were (expressly) overlooked in Nouwen and Chernilovskaya (2015) – as well as in TG: differences in prosody and more fine-grained differences in meaning, specifically, (i) the epistemic status of the prejacent, and (ii) the nature of the affect expressed. I will not rehash the whole discussion here, but I will summarize the main points, repeating the key examples.

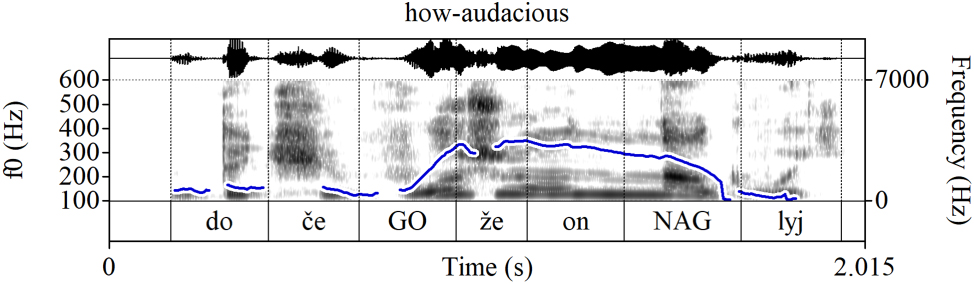

Regarding prosody, Type 1 exclamations (which are, once again, subject to the degree constraint, so only ‘How smart she is!’-like exclamations can be this type) have some version of the “hat contour”, illustrated in (25),[17] i.e., they have a falling boundary contour and an L*+H pitch accent on the wh-item. There can also be additional prominence on the predicate associated with the wh-item (a single high tone or also bitonal, placing extra emphasis on the predicate). More gradient aspects of prosody, e.g., voice quality or intensity, and gesture (including facial expressions) convey the specific flavor of the affect.

| Do | čego | (že) | on | naglyj!18 (how-audacious.wav) |

| to | what.n.gen | (že) | he | audacious |

| ≈‘Damn he’s audacious!’ | ||||

|

(Type 1 contour) | |||

- 18

See Esipova (2024d) on the role of the že particle.

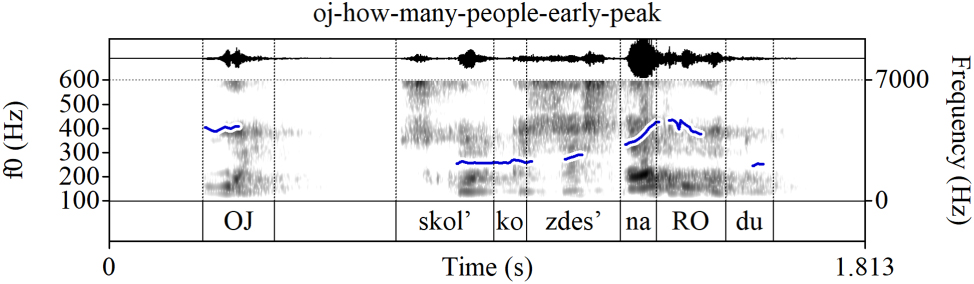

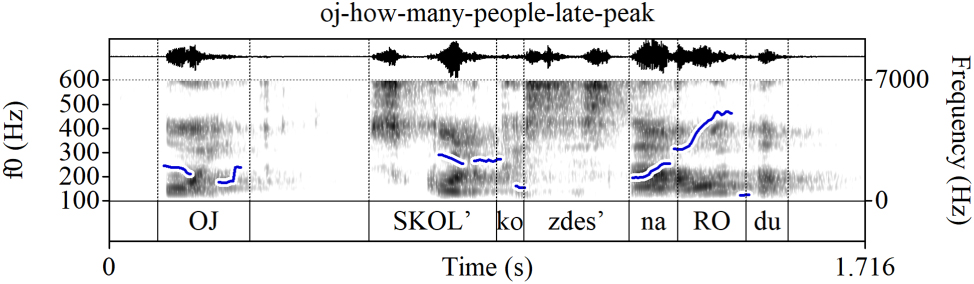

In contrast, Type 2 exclamations (which are not subject to the degree constraint, thus, either ‘How smart she is!’-like or ‘Who came!’-like exclamations can be this type) can be produced with a variety of contours (all distinct from Type 1 prosody), with further differences in meaning. In Esipova (2024d), I focused on three contours, exemplified in (26): Early Peak, Late Peak, and Plateau.

| (Oj!) | Skol’ko | zdes’ | narodu! | (oj-how-many-people-….wav) |

| (oj) | how.much | here | people | |

| ≈‘[I can’t believe / You won’t believe / Look] how many people there are here!’ | ||||

|

(Early Peak) |

|

(Late Peak) |

|

(Plateau) |

As for the more fine-grained differences in meaning, in Type 1 exclamations, the prejacent has to encode old information, but it has to be recent enough or reactivated to trigger the affect (e.g., ‘How smart she is!’ can be exclaimed if the speaker has long believed that the referent of ‘she’ is very smart, but now they see yet another display of that). Relatedly, Type 1 sentences can’t express the speaker’s immediate surprise as a reaction to some new information. Even if this information was introduced recently, it first must be added to the speaker’s beliefs. Type 1 exclamations are then used to express some other type of affect about it, such as admiration, anger, annoyance, awe, etc. These two properties are connected, as these types of affect are indeed veridical in the sense that in order for you to experience, say, anger about something, you need to first accept its truth/existence.

In contrast, Type 2 sentences are always uttered in information acquisition contexts, with further differences across the three contours, which I already partially reflected in my approximate English paraphrases in (26). Early Peak indicates information acquisition by the speaker; such exclamations are a reaction to something new and convey genuine surprise. Late Peak indicates information acquisition by the addressee; it conveys that the speaker is about to tell the addressee something that they themselves find noteworthy/exciting and expect the same sentiment from the addressee. Plateau exclamations can be used either as a reaction to something or in ‘I’m about to tell you something exciting’ contexts (although they seem to have a strong attention-drawing component either way). They do not convey genuine surprise on behalf of the speaker, though, but are typically used either ironically or in child-directed speech.

The paradigm below illustrates this difference between Type 1 and Type 2 exclamations. In both (27) (degree wh-item) and (28) (non-degree wh-item), I react to something new and unexpected, with Early Peak being the appropriate contour (Plateau is possible, too, but would convey irony and at best mild amusement rather than genuine surprise).

| Scenario A1: I am hosting a party that starts in an hour. I need to run out and grab something from a nearby store. I open the door on my way out and see Anya, one of my guests. | |||||

| Oj! | Kak | rano | ty | prišla! | (Early Peak; oj-how-early-early-peak.wav) |

| oj | how | early | you | came | |

| ≈‘Oh wow! [I can’t believe] how early you came!’ | |||||

| Scenario B1: The party is on. The doorbell rings announcing the arrival of another guest. I open the door and see Anya, who I did not expect to come. | |||||

| Oj! | Kto | k | nam | prišël! | (Early Peak; oj-who-came-early-peak.wav) |

| oj | who | to | us | came | |

| ≈‘Oh wow! [I can’t believe] who came to us!’ | |||||

(29) is a continuation of scenario A1, in which Anya’s early arrival is no news to either me or my addressee (no information acquisition), and I am expressing my annoyance about it via a Type 1 exclamation. However, I cannot do a similar thing in (30), with a non-degree wh-item. In fact, (30) is quite hard to produce and can be at best read as a frustrated wh-question (≈‘Who came to us then?!’), although the intonation would be a little off for the question reading. In (31), however, we have an addressee-oriented information acquisition context, and we can, thus, felicitously produce the target string with the Late Peak contour. We, thus, see that Type 1 exclamations are indeed subject to the degree constraint, but Type 2 sentences aren’t.

| Scenario A2: I am annoyed that Anya showed up so early, it really disrupted my preparation process. I am now in a different room, talking to my partner, who also saw her come in. | |||||

| Kak | že | Anja | rano | prišla! | (Type 1 contour; how-early-type1.wav) |

| how | že | Anya | early | came | |

| ≈‘Damn Anya came early!’ (I’m expressing my annoyance at how early Anya came.) | |||||

| Scenario B2: I am annoyed that Anya showed up; I didn’t even invite her, because I don’t like her. I am now in a different room, talking to my partner, who also saw her come in. | |||||

| *Kto | že | k | nam | prišël! | (Type 1 contour; who-came-type1-attempt.wav) |

| who | že | to | us | came | |

| Intended: ≈‘Damn that Anya came to us!’ (I’m expressing my annoyance that this person came.) | |||||

| Scenario B3: I am excited that Anya showed up, it was a pleasant surprise. I run to a different room to tell my partner, who didn’t see her come in; I expect them to be excited, too. | |||||

| Oj! | Kto | k | nam | prišël! | (Late Peak; oj-who-came-late-peak.wav) |

| oj | who | to | us | came | |

| ≈‘[You won’t believe] who came to us!’ | |||||

Based on all this and some additional evidence that I will not rehash here, in Esipova (2024d), I then proposed to analyze Type 1 exclamations as instances of expressive intensification, thus, capturing both the degree constraint they are subject to and the fact that said degree has to be high. The specific implementation of this insight was then refined in Esipova (2024c).

As for Type 2 exclamations, I proposed in Esipova (2024d) that they “involve embedding under a mirative predicate – or rather a family of complex related mirative predicates” (note again the meaning differences across the three contours discussed above) – “that get exponed prosodically (and perhaps partially via gesture) and can operate on propositions”, hence the lack of the degree constraint. While I didn’t provide a detailed semantic analysis for those, I did note that by mirative I meant that “all these predicates have the information acquisition meaning component and convey some surprise-related affect”. I also claimed that Russian ‘Who came!’ is then structurally akin to English Look/I can’t believe/You won’t believe who came!, with the difference between Russian and English being that the latter just doesn’t have these prosodically expressed mirative predicates in its lexicon (although I don’t necessarily believe that the (un)availability of such predicates is just an accident). Thus, English wh-exclamatives can only be Type 1 exclamations, although Russian and English Type 1 exclamations still have different compositional structures (but with the same final result), as I argue for independent reasons in Esipova (2024c).

So one might then conclude that TG’s story is correct, but only for Type 2 exclamations. Except having now thought about the issues discussed in Section 3, I don’t think that it is. Whatever predicate or operator is involved in Type 2 exclamations, and whether or not they involve actual embedding,[19] the whole structure still cannot be semantically equivalent to ‘I am amazed/surprised/etc. that/at…’, because Russian Type 2 exclamations do not behave in the discourse like assertions with emotive predicates at all. In fact, all meaning components of Russian Type 2 exclamations are aggressively allergic to being directly denied. Thus, I simply cannot imagine any way of denying (26)–(28) or (31) – in fact, I would not even know what there is to deny there, as there aren’t even any presuppositions for me to try to object to. At least, in (25) or (29), I can object to the presupposition that there exists an exclamation-worthy degree of him being audacious or of the earliness of Anya’s arrival, respectively:

| {Da | ne(t), | on | ne | naglyj. | / | Da | ničego | on | ne |

| advers | no/nah | he | not | audacious | / | advers | nothing | he | not |

| naglyj. | / | Da | ne | nastol’ko | už | on | naglyj.} | ||

| audacious | / | advers | not | that.much | already | he | audacious | ||

| ≈‘No/nah, he’s not (that) audacious.’ | |||||||||

| {Da | ne(t), | ne | rano. | / | Da | ničego | ne | rano. | / |

| advers | no/nah | not | early | / | advers | nothing | not | early | / |

| Da | ne | nastol’ko | už | rano.} | |||||

| advers | not | that.much | already | early | |||||

| ≈‘No/nah, not (that) early.’ | |||||||||

And to the extent that you can felicitously use Type 2 exclamations in response to any questions, it is only to very broad questions and probably only Late Peak ones, in a way that is very obviously a case of indirectly relevant reactions, which do not actually address the question:

| Kak | prošla | konferencija? |

| how | went | conference |

| ‘How did the conference go?’ | ||

| Oj! | Kogo | ja | videla! | (produced with Late Peak) |

| oj | who.acc | I.nom | saw | |

| ≈‘Oh, [you won’t believe] who I saw!’20 | ||||

- 20

I also asked a non-linguist native speaker of Russian about (32a) and (33) (the other Russian data in this paper come from my earlier work and have been verified with multiple Russian speakers). For (32a), they said that these responses feel less appropriate in response to someone exclaiming ‘How audacious he is!’ than in response to someone asserting ‘He is very audacious’, because unlike the latter case, in the former case, the speaker “isn’t trying to start a discussion”. Similarly, when I asked them if B is “answering A’s question” in (33), they said that technically no, but it’s still a possible way to react to A’s question.

This does not necessarily undermine the similarities with the English Look who came! – and to some extent, the cases of embedding under interjections (Zyman 2018), illustrated in (34) (all examples from Zyman 2018), both of which do not seem to function in the discourse like assertions about one’s attitude either and, thus, shouldn’t be analyzed as such.

| …wow with the level of idiocy the Angel baserunners have shown… |

| …wow that they already have copies… |

| …Damn with your fucking fly ass… |

| Also, damn that I missed it. |

| …yuck with the Amber Rose pictures… |

| Cool that you have deer, yuck that they poop. |

The bottom line is that the taxonomy of exclamations within and across languages is very complex in a way that, I believe, should be highlighted, not obscured in our analyses. Furthermore, careful investigation of prosody and more fine-grained meaning distinctions of these different exclamation types is imperative for building descriptively and explanatorily adequate analyses.

5 More on intensity and affect

Before I wrap up, let me add a quick note on intensity, as I was somewhat confused by the relevant discussion in TG. For instance, on p. 23 of their paper, TG write: “When the complement concerns a degree, counter-expectation is responsible for producing intensity” – and they make similar claims throughout the paper. However, it is not always clear to me when they talk about intensity of affect versus intensity of the degree in the prejacent and what the link between them is supposed to be.

Let us first note that, in principle, intensity of affect and intensity of the degree in the source of the affect are two separate things, even if there is sometimes an intuitive link between the two. For instance, when it comes specifically to counter-expectation,[21] it stands to reason that in the case of normally or close-to-normally distributed values, extreme degrees (i.e., degrees close to the ends of the distribution) will trigger counter-expectation more often because they have low probability. However, one can experience strong affect about a non-extreme degree, and conversely, an extreme degree can yield only mild affect. This separation is maintained in declaratives with emotive predicates like amazed or surprised:

| I am mildly {amazed at / surprised by} how extremely tall Eva is. |

| I am extremely surprised that Eva is 165cm tall – she looks much taller in the pictures.22 |

- 22

165 cm is around the average height for women in many English-speaking countries, which is what I was shooting for here, although the global average is below that.

It is true that without a degree modifier, (36a) is completely degree-neutral while, at least by default, (36b) will be interpreted as being about a fairly high degree, and I believe that in (36c), to the extent that this effect exists, it is fairly easy to override.

| I know how tall Eva is. |

| I am amazed at how tall Eva is. |

| I am surprised by how tall Eva is. |

Whether these default interpretations should be analyzed as pragmatic (more explanatory by default) or by positing something extra in the compositional structure (less explanatory by default) – the point above still stands: even in the case of counter-expectation, the intensity of affect and the intensity of the degree in its source do come apart easily in the case of truth-conditional emotive predicates.

Now, in the case of expressive intensification, of which I claim exclamatives to be a sub-case, the two do indeed seem to come together, and in my demonstration-based account of expressive intensification at large, the link is explicit: the truth-conditional intensification component makes reference to the expressive form (specifically, saying that the degree is such that it would warrant the use of this form) while producing the expressive form itself still serves as expression of affect.

However, TG explicitly argue against the idea that exclamatives constitute expressive speech acts; they maintain that not only is the affect-related component in exclamatives truth-conditional, but it is, in fact, asserted. Furthermore, as I noted above, there is no principled reason why, if TG’s null emotive predicate takes a proposition argument, which they claim it does, should that proposition argument contain a degree, let alone an intensified one (again, TG share this issue with Rett 2011). Truth-conditional emotive predicates in and of themselves don’t require degrees, let alone intensified ones, and TG write this about the Greek pu complementizer on p. 31 of their paper: “pu can also appear without the expression of extreme degree – the only licensing condition being that pu is embedded by an emotive predicate in the matrix clause”. They then continue: “In other words, the degree phrase contributes to the emotive interpretation (adding intensity…), but it does not constitute emotivity”. The degree phrase they are talking about here is ti grigora ‘what fast’, and they argue that ti in this case is actually an intensifier they label SO. But why does there have to be a degree phrase in exclamatives in the first place, if embedding under pu does not require it in and of itself? And how exactly does this degree phrase “contribute to the emotive interpretation”? When they say “adding intensity”, do they mean to the affect? But how does it do that, in view of the examples in (35)? I must admit that neither the core conceptual insight nor its compositional implementation are clear to me here.

6 Conclusion

I, thus, conclude that an approach that fully assimilates exclamatives to declaratives that assert propositions about attitudes like I am amazed {at / that}… is unjustified. It is, in my mind, still uncontroversial that we need a distinction between expressing and asserting affect, and that the primary purpose of exclamatives is, in fact, to express, not assert affect about some presupposed content. That said, the taxonomy of exclamatives and other types of exclamations within and across languages is complex and needs to be investigated further, without ignoring any aspects of their form or meaning. Similarly, the phenomenon of primary and secondary speech acts co-existing within one utterance, as well as the proper ways to operationalize this phenomenon architecturally should be explored further.

References

Castroviejo Miró, Elena. 2008. An expressive answer: Some considerations on the semantics and pragmatics of wh-exclamatives. CLS 44(2). 3–17.Search in Google Scholar

Clark, Herbert H. 2016. Depicting as a method of communication. Psychological Review 123. 324–347. https://doi.org/10.1037/rev0000026.Search in Google Scholar

Davidson, Kathryn. 2015. Quotation, demonstration, and iconicity. Linguistics and Philosophy 38. 477–520. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10988-015-9180-1.Search in Google Scholar

Davidson, Kathryn. 2022. Depictive versus patterned iconicity and dual semantic representations. Talk given at The 96th Annual Meeting of the LSA. Washington, DC.Search in Google Scholar

Dingemanse, Mark. 2015. Ideophones and reduplication: Depiction, description, and the interpretation of repeated talk in discourse. Studies in Language 39. 946–970. https://doi.org/10.1075/sl.39.4.05din.Search in Google Scholar

Elliott, Dale E. 1974. Toward a grammar of exclamations. Foundations of Language 11. 231–246.Search in Google Scholar

Esipova, Maria. 2019a. Composition and projection in speech and gesture. New York University Dissertation. Available at: https://ling.auf.net/lingbuzz/004676.10.3765/salt.v29i0.4600Search in Google Scholar

Esipova, Maria. 2019b. Towards a uniform super-linguistic theory of projection. In Julian J. Schlöder, Dean McHugh & Floris Roelofsen (eds.), Proceedings of the 22nd Amsterdam colloquium, 553–562. Available at: https://ling.auf.net/lingbuzz/004905.Search in Google Scholar

Esipova, Maria. 2023. The silence of the slurs: Inferences about prejudice under ellipsis. Ms., in revision for Glossa. Available at: https://ling.auf.net/lingbuzz/007109.Search in Google Scholar

Esipova, Maria. 2024a. Composure and composition. Ms., under revision. Available at: https://ling.auf.net/lingbuzz/005003.Search in Google Scholar

Esipova, Maria. 2024b. Prosody across sentence types. SALT 34. 68–87.10.3765/pe3dtd58Search in Google Scholar

Esipova, Maria. 2024c. The things that we can(not) exclaim. Proceedings of the Linguistic Society of America 9(1). 5723. https://doi.org/10.3765/plsa.v9i1.5723.Search in Google Scholar

Esipova, Maria. 2024d. What I will tell you about “matrix” wh-“exclamatives”. WCCFL 39. 519–527.Search in Google Scholar

Kaplan, David. 1999. The meaning of ouch and oops: Explorations in the theory of meaning as use. Ms. UCLA.Search in Google Scholar

Koev, Todor. 2018. Notions of at-issueness. Language and Linguistic Compass 12(12). e12306. https://doi.org/10.1111/lnc3.12306.Search in Google Scholar

Nouwen, Rick & Anna Chernilovskaya. 2015. Two types of wh-exclamatives. Linguistic Variation 15. 201–224. https://doi.org/10.1075/lv.15.2.03nou.Search in Google Scholar

Potts, Christopher. 2005. The logic of conventional implicatures. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199273829.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Potts, Christopher. 2007. The expressive dimension. Theoretical Linguistics 33. 165–198. https://doi.org/10.1515/TL.2007.011.Search in Google Scholar

Rett, Jessica. 2011. Exclamatives, degrees and speech acts. Linguistics and Philosophy 34. 411–442. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10988-011-9103-8.Search in Google Scholar

Saab, Andrés. 2020. On the locus of expressivity. Deriving parallel meaning dimensions from architectural considerations. In Eleonora Orlando & Andrés Saab (eds.), Slurs and expressivity, 17–44. Lanham:Lexington Books.10.5040/9781978728059.ch2Search in Google Scholar

Schlenker, Philippe. 2007. Expressive presuppositions. Theoretical Linguistics 33. 237–245. https://doi.org/10.1515/TL.2007.017.Search in Google Scholar

Simons, Mandy, Judith Tonhauser, David Beaver & Craige Roberts. 2010. What projects and why. SALT 20. 309–327.10.3765/salt.v20i0.2584Search in Google Scholar

Zyman, Erik. 2018. Interjections select and project. Snippets32. 9–11.10.7358/snip-2017-032-zymbSearch in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Target Article: Andreas Trotzke and Anastasia Giannakidou; Issue Editor: Hans-Martin Gärtner

- Exclamation, intensity, and emotive assertion

- Comments

- Empirical and theoretical arguments against equating exclamatives and emotive assertions

- Exclamations as emotive assertions: more questions (than answers)

- In defense of exclamatory force

- Exclamation, epistemic assertion and interlocutor’s subjectivity

- Challenging exclamations!

- Exclamatives, try to be a bit more assertive!

- Not all exclamatives behave the same

- Reply

- The landscape of exclamations: brief musings on emotive language

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Target Article: Andreas Trotzke and Anastasia Giannakidou; Issue Editor: Hans-Martin Gärtner

- Exclamation, intensity, and emotive assertion

- Comments

- Empirical and theoretical arguments against equating exclamatives and emotive assertions

- Exclamations as emotive assertions: more questions (than answers)

- In defense of exclamatory force

- Exclamation, epistemic assertion and interlocutor’s subjectivity

- Challenging exclamations!

- Exclamatives, try to be a bit more assertive!

- Not all exclamatives behave the same

- Reply

- The landscape of exclamations: brief musings on emotive language