Abstract

Here we compare the efficacy of anti-obesity drugs alone or combined with exercise training on body weight and exercise capacity of obese patients. Randomized clinical trials that assessed the impact of any anti-obesity drug alone or combined with exercise training on body weight, body fat, fat-free mass and cardiorespiratory fitness in obese patients were retrieved from Pubmed and EMBASE up to May 2024. Risk of bias assessment was performed with RoB 2.0, and the GRADE approach assessed the certainty of evidence (CoE) of each main outcome. We included four publications summing up 202 patients. Two publications used orlistat as an anti-obesity drug treatment, while the other two adopted GLP-1 receptor agonist (liraglutide or tirzepatide) as a pharmacotherapy for weight management. Orlistat combined with exercise was superior to change body weight (mean difference (MD): −2.27 kg; 95 % CI: −2.86 to −1.69; CoE: very low), fat mass (MD: −2.89; 95 % CI: −3.87 to −1.91; CoE: very low), fat-free mass (MD: 0.56; 95 % CI: 0.40–0.72; CoE: very low), and VO2Peak (MD: 2.64; 95 % CI: 2.52–2.76; CoE: very low). GLP-1 receptor agonist drugs combined with exercise had a great effect on body weight (MD: −3.96 kg; 95 % CI: −5.07 to −2.85; CoE: low), fat mass (MD: −1.76; 95 % CI: −2.24 to −1.27; CoE: low), fat-free mass (MD: 0.50; 95 % CI: −0.98 to 1.98; CoE: very low) and VO2Peak (MD: 2.47; 95 % CI: 1.31–3.63; CoE: very low). The results reported here suggest that exercise training remains an important approach in weight management when combined with pharmacological treatment.

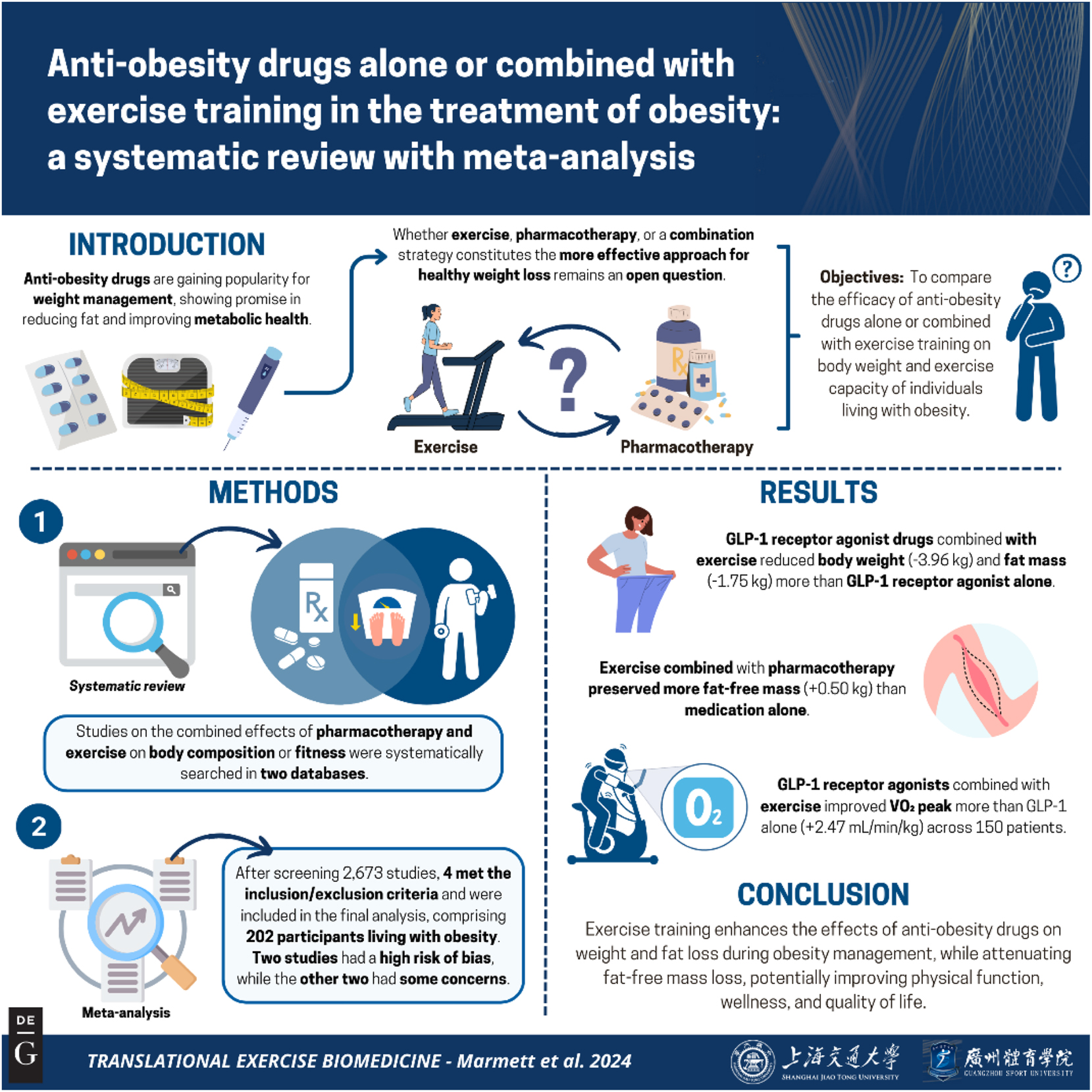

Introduction

The increasing worldwide prevalence of obesity is associated with a range of non-communicable chronic diseases and the development of premature morbidity and mortality [1]. Although genetic background accounts for weight gain susceptibility, lifestyle habits such as high-caloric diet patterns and physical inactivity exert strong influence on obesity development [2]. Weight loss is a major goal to manage excess body weight and prevent the progression of obesity-related diseases [1], 2]. While even a modest 3–5 % weight loss induces positive health impacts by lowering obesity-related risk factors, individuals with coexisting conditions or severe obesity may require a larger reduction of 5–15 % to achieve optimal health outcomes [3].

Non-pharmacological interventions to treat obesity generally focus on lifestyle interventions such as increased physical activity to obtain moderate weight loss [4]. Exercise training adaptations are observed through improved metabolic health and cardiorespiratory fitness. In addition, exercise decreases fat mass and preserves or increases lean mass [5]. However, although lifestyle changes are usually recommended as interventions to treat obesity, their long-term adherence and applicability in modern life are challenging [6], 7].

Anti-obesity drugs, like GLP-1 receptor agonists and inhibitors of gastric and pancreatic lipase, are popular for weight management, showing promised results such as lowered fat mass and improved metabolic health [8], 9]. In this line, a recent meta-analysis showed that semaglutide, a GLP-1 receptor agonist, decreases body weight in order to 11.80 % [9]; and a recent network meta-analysis indicated a range of weight loss between 5 and 15 % of total body weight [10]. However, weight loss induced by pharmacotherapy usually also affects free fat mass; the decrease in lean muscle may poses an additional threat to the health and well-being of people already losing weight [11], 12]. Furthermore, clinical trials failed to identify changes on functional status of physical capacity, measured by questionnaires, after anti-obesity drugs administration [13]. In this line, there are recommendations to use anti-obesity pharmacotherapy as an adjuvant intervention of exercise training in the treatment of obesity, since the ability of the former to prevent or at least attenuate fat-free mass loss [5], 14]. Whether exercise, pharmacotherapy, or a combined strategy constitutes the more effective approach for healthy weight loss remains an open question. Here, we aimed to systematically review the effect of anti-obesity drugs alone or combined with exercise training on body composition of obese individuals. The summary of this review is presented in Figure 1.

Graphical representation of this study. Key points: (1) anti-obesity drug combined with exercise had superior effect on body weight management than pharmacotherapy alone; (2) adding exercise to anti-obesity pharmacotherapy attenuates fat-free mass loss; (3) anti-obesity drug plus exercise may increase VO2Peak but the evidence is very uncertain. These results contribute to translational knowledge of obesity management science by adding new perspectives on the combination of pharmacotherapy and physical exercise. Figure created with BioRender.

Methods

This systematic review was conducted and reported following the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines, respectively [15], 16]. The systematic review protocol (identification number CRD42023479408) was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO).

Eligibility criteria

We included clinical trials considering the following eligibility criteria: adults (aged >18 years) patients diagnosed with obesity (Body mass index [BMI] >30 kg/m2) without type 2 diabetes; and studies evaluating the efficacy of anti-obesity drugs alone interventions compared to anti-obesity drugs combined with exercise training in at least one of the following outcomes: absolute changes of body weight, BMI, fat mass, fat-free mass, and aerobic fitness. We only included randomized clinical trials (RCTs). We did not restrict the type of anti-obesity drug in the eligibility criteria. There were no restrictions on publication status, language, or methodological quality.

Search strategy

Structured searches were performed on Medline (via PubMed), Embase from inception to May 2024 for published studies in indexed journals. We searched for available unpublished results of clinical studies in the clinical trials register (clinicaltrials.gov). The following search terms were used: obesity, obese, overweight, exercise training, anti-obesity drugs, and pharmacotherapy. We combined the specific terms and related synonyms with Boolean operators with appropriate limiters, adapting the terms according to each database requirements. We did not include terms related to the outcomes of interest to enhance search sensitivity. The specific search strategies are referred to in Supplementary Material 1.

Study selection and data extraction

Initially, two independent reviewers assessed the titles and abstracts identified in the search. Studies that failed to satisfy the inclusion criteria were excluded. The remaining citations underwent a full-text review by the same two independent reviewers. Only studies that adhered to the predefined eligibility criteria were included in the final analysis.

Two reviewers independently extracted key data from the included studies using pre-designed tables. The extracted information covered methodological features of the studies and the outcomes of interest. In cases where standard deviations were not reported, they were estimated from p-values or derived from standard deviations provided for the same outcome in other treatment groups within the same study. Any disagreements between the reviewers were resolved through consensus or by involving a third reviewer for arbitration.

Risk of bias and certainty of evidence assessment

Included studies were critically appraised by two independent reviewers using RoB 2.0 [17]. The overall certainty of evidence of each primary outcome was assessed using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) framework [18], 19]. Any discrepancies in the quality assessment were resolved through consensus or, when necessary, by involving a third reviewer. Narrative statements as plain language was used based on GRADE Guidance 26 to communicate results from systematic reviews of interventions [20].

Data analysis

Data were synthesized using both qualitative and quantitative approaches. For qualitative synthesis, a detailed summary table was created, outlining the populations, interventions, comparators, and outcomes. Following data extraction, pooled effect estimates for continuous outcomes were calculated by comparing baseline and study-end changes within each group, applying a random-effects model with the DerSimonian and Laird method for variance estimation. Heterogeneity was evaluated using the I2 statistic, and results were visualized as forest plots displaying point estimates and 95 % confidence intervals. Meta-analyses were performed using R statistical software (version 4.1.2) with the ‘meta’ package (version 6.5-0). Due to the limited number of included studies, publication bias was not assessed [21].

Results

Search results and included studies

We identified 2,673 unique records in our initial search. After the screening of titles and abstracts, 29 publications remained. Of these, 25 were excluded due to the following reasons: intervention (n=14), outcome (n=2), study design (n=2), and duplicate data (n=7). The main reason to exclude intervention was the absence of a group-treated anti-obesity drug without exercise training, or due to a lack of exercise training intervention. A total of four studies [22], [23], [24], [25] met the inclusion criteria, providing data from 202 participants (Figure 1). Details of the studies excluded during full-text screening, along with the reasons for their exclusion, are presented in Supplementary Material 2.

Description of studies

This systematic review included four studies with a total of 202 participants with obesity [22], [23], [24], [25]. The sample sizes of the individual studies ranged from 24 to 98 participants. All studies focused on non-diabetic obese individuals, with a mean BMI ranging from 32.7 to 39.8, and participants’ mean age ranged from 20 to 50 years. Most participants were female in three studies, while Bagherzadeh-Rahmani and coworkers [25] only included male obese patients. Interventions lasted from one month, three months, and 12 months. Two studies used orlistat as an anti-obesity drug (120 mg capsule with each main meal; example: 3 × 120 mg/day) [22], 24]. Lundgren and coworkers [23] used liraglutide, a GLP-1ra, with final dose of 3.0 mg per day. One study [25] administered 2.5 and 5 mg of tirzepatide, a GLP-1ra combined with glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP), as pharmacotherapy to the obesity treatment.

Three studies used supervised endurance training as exercise intervention [22], [23], [24]. Lundgren et al. [23] combined supervised sessions of group exercise (30 min of high-intensity interval- indoor cycling and 15 min of circuit training; 2×/week) and individual moderate-to vigorous–intensity exercise session (outdoor or indoor endurance exercise; 2×/week). Exercise interventions combined with orlistat consisted of endurance training at an anaerobic threshold lasting 35–45 min, three times per week [22], 24]. Bagherzadeh-Rahmani and colleagues [25] combined periodized resistance training with aerobic exercise performed three times a week (resistance training [RT]: four exercises for the upper body and four exercises for the lower body). Endurance training consisted in moderate intensity (45–65 % of heart rate reverse) (Table 1). Regarding diet consumption, Colak and Ozcelik [22], Ozcelik and colleagues [24], and Ludgren and colleagues [23] used hypocaloric diet associated with pharmacological intervention alone or associated with exercise. The study of Bagherzadeh-Rahmani and colleagues [25] analyzed nutrients and dietary intake without any restriction of diet calories.

Methodological characteristics of the included studies.

| Author, year | Study groups | Participants | Age, years | BMI (kg/m2) | Medication dose | Exercise training | Follow-up, weeks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colak and Ozcelik 2004 [22] | Orlistat | 24 adults with obesity | 38.3 (10) | 36.1 (3.6) | 1,200 mg, 3×/day | – | 4 |

| Orlistat + exercise | 37.5 (8) | 39.8 (5.4) | 35–45 min of endurance exercise at anaerobic threshold (3×/week) | ||||

| Ozcelik et al. 2015 [24] | Orlistat | 28 sedentary obese women | NR | 40.1 (2.9) | 1,200 mg, 3×/day | – | 12 |

| Orlistat + exercise | 39.1 (2.5) | 45 min of endurance exercise (3×/week) | |||||

| Lundgren et al. 2021 [23] | Liraglutide | 98 adults with obesity | 43 (12) | 32.7 (3.1) | Starting dose: 0.6 mg/day Weekly increment: 0.6 mg/day; Intended dose: 3.0 mg/day |

– | 48 |

| Liraglutide + exercise | 42 (12) | 32.8 (2.4) | Supervised sessions: 30 min of high-intensity interval- cycling and 15 min of circuit training (2×/week) Individual sessions: moderate-to high–intensity exercise (2×/week) |

||||

| Bagherzadeh-Rahmani, 2024 [25] | Tirzepatide 2.5 mg | 52 adults with obesity | Age between 20 and 32 years. | 36.1 (0.6) | 2.5 mg or 5 mg once a week. | – | |

| Tirzepatide 5 mg | 36.3 (1.1) | – | |||||

| Tirzepatide 2.5 mg + exercise | 36.5 (1.2) | Group exercise (supervised): resistance exercise combined with endurance exercise (moderate intensity: 45–65 % of HR reverse) (3×/week). Session detailed: warmup, main training section and cool-down. Resistance training: four upper body exercises (bench press, lat pull-down, biceps and triceps exercises) and four lower body exercises (squat, leg press, knee extension, and leg curl). |

|||||

| Tirzepatide 5 mg + exercise | 36.3 (1.6) | 6 |

-

Data presented as mean (standard deviation). HR, heart rate; NR, not reported; min, minutes.

Risk of bias

The risk of bias of body weight, fat mass, fat-free mass and exercise capacity of the included studies are presented in Figure 2. For all outcomes, one study was assessed as having a high risk of bias, while two studies raised concerns regarding the randomization process. Two studies were classified as having a high risk of bias, and one study showed concerns regarding deviations from the intended intervention. Additionally, three studies presented concerns about the selection of reported results. The overall risk of bias was characterized as high risk in Colak & Ozcelik [22] and Ozcelik et al. [24], and some concerns in Lundgren et al. [23] and Bagherzadeh-Rahmani et al. [25].

PRISMA flowchart of included studies.

Efficacy outcomes

Here, we presented the efficacy of anti-obesity drugs separated by the type of pharmacological action. Tirzepatide was analyzed with liraglutide as a GLP-1 receptor agonist. Orlistat, an inhibitor of pancreatic lipase, combined with exercise changed body weight (MD: −2.27 kg; 95 % IC: −2.86 to −1.69; I2=94 %; two studies), fat mass (MD: −2.88; 95 % IC: −3.86 to −1.90; I2: 94.6 %; two studies) and fat-free mass (MD: 0.56; 95 % IC: 0.40–0.72; I2: 0 %; two studies) in 52 patients [22], 24]. GLP-1ra drugs, liraglutide and tirzepatide, combined with exercise improve weight management compared to GLP-1ra alone in body mass (MD: −3.96 kg; 95 % CI: −5.07 to −2.85; I2=0 %; two studies) fat mass (MD: −1.75; 95 % IC: −2.24 to −1.27; I2: 0 %; two studies) and fat-free mass (MD: 0.50; 95 % IC: −0.98 to 1.98; one study) in 150 patients [23], 25] (Figure 3).

Risk of bias of the included studies.

Also, one study evaluated the effect of orlistat combined with exercise training vs. only orlistat interventions on VO2Peak (MD: 2.64; 95 % CI: 2.52–2.75) in 24 patients [22]. GLP-1ra combined with exercise training improved VO2Peak more than GLP-1 receptor agonist alone (MD: 2.47; 95 % CI: 1.31–3.63; I2=80.2 %) in 150 patients of three studies [23], 25] (Figures 4 and 5).

Changes on body weight, fat mass and fat-free mass after the treatment of anti-obesity drugs alone or combined with exercise training on obese patients.

The effect of anti-obesity drugs alone or combined with exercise training on cardiorespiratory fitness.

The certainty of the evidence was very low for the assessment of orlistat plus exercise training on body composition and cardiorespiratory fitness (Table 2). The evidence suggests that orlistat plus exercise training has little effect on outcome change compared to orlistat alone, but the evidence is very uncertain. Considering GLP-1 receptor agonists, the certainty of the evidence was low to very low for the assessment of efficacy outcomes (Table 3). This means that GLP-1 receptor agonist plus exercise training may reduce body weight and body fat slightly compared to GLP-1 receptor agonist alone. Furthermore, GLP-1 receptor agonist plus exercise training may increase fat-free mass and VO2Peak compared to GLP-1 receptor agonist alone, but the evidence is very uncertain. The overall judgment of each GRADE’s domain is presented in Supplementary Material 3 and 4.

Overall certainty of the evidence of orlistat plus exercise training in the treatment of obesity.

| Outcome Participants (studies) |

Relative effect (95 % CI) | Anticipated absolute effects (95 % CI) | Certainty | What happened |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Difference | ||||

| Body weight change Number of participants: 52 (2 RCTs) |

– | MD 2.27 kg lower (2.86 lower to 1.69 lower) | ⨁◯◯◯ Very lowa,b |

Orlistat plus exercise training has little effect on body weight change compared to orlistat alone but the evidence is very uncertain. |

| Body fat change Number of participants: 52 (2 RCTs) |

– | MD 2.89 kg lower (3.87 lower to 1.91 lower) | ⨁◯◯◯ Very lowa,b,c |

Orlistat plus exercise training has little effect on body fat change compared to orlistat alone but the evidence is very uncertain. |

| Fat-free mass change Number of participants: 52 (2 RCTs) |

– | MD 0.56 kg higher (0.4 higher to 0.72 higher) | ⨁◯◯◯ Very lowa,b |

Orlistat plus exercise training may increase fat-free mass compared to orlistat alone but the evidence is very uncertain. |

| Peak of oxygen consumption Number of participants: 24 (1 RCT) |

– | MD 2.64 mL/kg/min higher (2.52 higher to 2.76 higher) | ⨁◯◯◯ Very lowb,d |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of orlistat plus exercise training on peak of oxygen consumption compared to orlistat alone. |

-

CI, confidence interval; MD, mean difference. Explanations: aTwo studies presented an overall high risk of bias. bLow number of patients. cLow overlap of point estimate and 95 % CI between studies. dHigh risk of bias in one study. Values in bold denotes the anticipated absolute impact of the intervention.

Overall certainty of evidence of body composition outcomes.

| Outcome Participants (studies) |

Relative effect (95 % CI) | Anticipated absolute effects (95 % CI) | Certainty | What happens |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Difference | ||||

| Body weight change Number of participants: 150 (2 RCTs) |

– | MD 3.96 kg lower (5.07 lower to 2.85 lower) | ⨁⨁◯◯ Lowa,b |

GLP-1 receptor agonist plus exercise training may reduce body weight slightly compared to GLP-1 receptor agonist alone. |

| Body fat change Number of participants: 150 (2 RCTs) |

– | MD 1.76 kg lower (2.24 lower to 1.27 lower) | ⨁⨁◯◯ Lowa,b |

GLP-1 receptor agonist plus exercise training may reduce body fat slightly compared to GLP-1 receptor agonist alone. |

| Fat-free mass change Number of participants: 98 (1 RCT) |

– | MD 0.5 kg higher (0.98 lower to 1.98 higher) | ⨁◯◯◯ Very lowa,b,c |

GLP-1 receptor agonist plus exercise training may increase fat-free mass but compared to GLP-1 receptor agonist alone the evidence is very uncertain. |

| Peak of oxygen consumption Number of participants: 150 (2 RCTs) |

– | MD 2.47 mL kg min higher (1.31 higher to 3.63 higher) | ⨁◯◯◯ Very lowa,b,d |

GLP-1 receptor agonist plus exercise training may increase peak of oxygen consumption compared to GLP-1 receptor agonist alone but the evidence is very uncertain. |

-

CI, confidence interval; MD, mean difference. Explanations: aTwo studies presented overall some concerns of risk of bias. bLow number of patients. cWidth of the 95 % CI suggests different intervention scenarios. dLow overlap of 95 % CI between studies. Values in bold denotes the anticipated absolute impact of the intervention.

Table 4 presents the comparison of anti-obesity drugs plus exercise vs. anti-obesity drugs alone on metabolic parameters of obese individuals. Only two studies [23], 25] presented results of Homeostatic Model Assessment for Insulin Resistance (HOMA-IR), and the serum levels of total and subtypes cholesterol fractions, and triglycerides. Exercise training plus anti-obesity drugs has favorable effects to decrease HOMA-IR (effect estimate: −0.40; 95 % CI: −0.51 to −0.28) and LDL levels (effect estimate: −8.89; 95 % CI: −11.52 to −6.26). Exercise plus anti-obesity drugs also increase HDL levels (effect estimate: 8.44; 95 % CI: 3.63–13.25) more than anti-obesity drugs alone.

Metanalysis results of metabolic parameters.

| Outcome | Number of studies | Sample size | Effect estimates (95 % CI) | p-Value | I2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HOMA-IR | 3 | 150 | −0.40 (−0.51 to −0.28) | <0.001 | 43.2 % |

| Cholesterol, mg/dL | 3 | 150 | −7.40 (−20.60 to 5.79) | 0.27 | 79.5 % |

| HDL, mg/dL | 3 | 150 | 8.44 (3.63–13.25) | <0.001 | 93.4 % |

| LDL, mg/dL | 3 | 150 | −8.89 (−11.52 to −6.26) | <0.001 | 43.3 % |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 3 | 150 | −9.55 (−26.19 to 7.07) | 0.25 | 86.5 % |

-

Metanalysis conducted through Random-effects model. I2, I square; HOMA-IR, Homeostatic Model Assessment for Insulin Resistance; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein.

Discussion

Pharmacotherapy has significantly advanced the management of excess body weight in recent years, contributing to obesity management [4]. However, several issues concerning its compatibility with lifestyle modifications, particularly exercise training, remain to be clarified [26], 27]. In this study, we conducted an up-to-date systematic review with meta-analysis and GRADE certainty of evidence assessment focusing on the role of anti-obesity drugs combined with exercise in weight management. Our findings suggest that exercise training enhances the efficacy of pharmacotherapy, primarily through lowering body weight and fat mass. Furthermore, adding exercise training to pharmacotherapy mitigates the loss of fat-free mass of obese patients. The results of this systematic review were analyzed according to drug type, specifically pancreatic lipase inhibitor Orlistat and GLP-1 receptor agonists.

Few data investigate the effects of pharmacotherapy combined with exercise on body composition to date. Notably, drugs used to treat other metabolic diseases can attenuate the benefits of exercise on obesity-related chronic conditions, such as type 2 diabetes [28], [29], [30]. For example, overweight or obese patients treated with the anti-diabetic drug sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors and engaged to exercise training (12 weeks) showed diminished improvements in insulin sensitivity despite positive adaptations in cardiorespiratory fitness [30]. Similarly, metformin, another anti-diabetic medication, may reduce the effectiveness of exercise on cardiometabolic risk factors in individuals with impaired glucose tolerance [31]. However, none of these studies specifically assessed the combined effects of anti-obesity drugs and exercise training in an obese population.

Our analysis demonstrates that anti-obesity drugs combined with exercise training yield superior results in reducing body weight and fat mass compared to pharmacotherapy alone. For instance, one year of liraglutide treatment combined with exercise training led to an additional reduction in body weight, resulting in a total weight loss of 16 % [23]. In comparison, intensive lifestyle interventions combining exercise and caloric restriction typically reduce body weight by 5–9 % [32], 33]. Exercise may also act synergistically with anti-obesity drugs by stimulating insulin release, suppressing appetite, lowering postprandial blood glucose levels, and slowing gastric emptying [34], 35]. However, the certainty of the evidence regarding reductions in body weight and fat mass was rated as low or very low, indicating that future studies may reveal substantially different effects than those estimated here.

Exercise training combined with anti-obesity drugs also preserves lean mass compared to anti-obesity drugs alone. Clinical trials have shown that a greater proportion of lean mass is generally lost during pharmacotherapy treatment in obesity management compared to placebo arm, mainly after rapid or great-magnitude weight loss [11], 36]. For example, some reports indicate that approximately 40 % of weight lost by obese patients treated with GLP-1ra tend to be lean mass [37]. In the first clinical trial of Semaglutide, the analysis of body composition changes by Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) revealed an average reduction of 17.32 kg of body weight, including a 6.92 kg mean reduction in total lean mass compared to placebo [37]. Similarly, participants treated with tirzepatide in SURMOUNT-1 trial lost 10.9 % of their lean mass in the pooled tirzepatide-treated analysis (5, 10 or 15 mg once weekly) [38]. Pharmacotherapy has the benefit of improving the body weight-to-lean mass ratio compared to conventional lifestyle interventions [39], 40], but the decrease observed in lean mass should be considered in obesity management. The loss of lean body mass associated with weight loss can increase the risk of sarcopenia, as well as impair strength and muscle function [11], 41]. Conversely, exercise training is a recommended strategy to mitigate muscle mass loss during voluntary weight loss and enhance muscle strength in obese adults [42]. A recent narrative review suggested that exercise training should be incorporated as an adjunct strategy of pharmacotherapy to optimize changes in body composition by preserving lean mass [43]. Exercise stimulates the phosphorylation of several intracellular molecular pathways, regulating protein turnover and promoting favorable anabolic responses in muscle tissue [44]. Moreover, exercise induces the release of molecules known as exerkines during muscle contraction, which help prevent muscle weakness and restore physical autonomy [45].

Despite similar point estimates in the subgroup analysis of orlistat and liraglutide treatments, the confidence intervals suggest differences in their efficacy for obesity management. Real-world studies indicate that liraglutide is more effective than orlistat in promoting weight loss and improving metabolic and cardiovascular risk factors associated with obesity [46], 47]. However, differences in trial designs may contribute to these discrepancies. For example, in the S-LITE trial, Lundgren and colleagues [23] initially enrolled adults with obesity in an 8-week low-calorie diet program. Participants were then randomized to one of four strategies for one year: a moderate-to-vigorous intensity exercise program plus placebo (exercise group); liraglutide treatment (3.0 mg per day) plus usual activity (liraglutide group); a combination of exercise and liraglutide therapy (combination group); or placebo plus usual activity (placebo group). In contrast, other trials assigned obese patients to 8-week [22] or 12-week [24] interventions combining a hypocaloric diet with orlistat, with or without exercise. Thus, prior weight loss induced by a low-calorie diet may influence not only weight maintenance and the efficacy of anti-obesity drugs but also exercise-induced adaptations.

Exercise training combined with anti-obesity drugs also improved cardiorespiratory fitness by a mean of 3.05 mL/kg/min compared to anti-obesity drugs alone. While there is evidence of pharmacotherapy negatively impacting exercise-mediated physical fitness adaptations in patients with cardiovascular or metabolic diseases [28], [29], [30], [31, 48], the impact of anti-obesity drugs on exercise adaptations remains underexplored. Our findings suggest that pharmacotherapy for obesity management does not impair exercise training adaptations. Enhancing VO2peak through exercise training in obese individuals provides metabolic benefits, improving both physical and mental health [49]. Obese patients with higher cardiorespiratory fitness levels exhibit similar mortality risks as normal-weight fit individuals, emphasizing the role of exercise adaptations in reducing obesity-associated mortality [50]. Additionally, obese individuals with greater cardiorespiratory fitness show reduced inflammatory mediators and improved immune profiles, mitigating immune dysfunction caused by excess fat mass [51], 52].

We also analyzed the effects of exercise training combined with GLP-1ra treatment on secondary outcomes, mainly cholesterol, HDL, LDL, triglycerides and insulin resistance index. Notably, exercise training combined with anti-obesity pharmacotherapy provides greater benefits on metabolic parameters compared to GLP-1ra treatment alone. These results indicate that exercise exerts synergistic effects with GLP-1ra drugs, directly impacting metabolically active tissues. In fact, Akerstrom and coworkers [53] showed that endurance training improves beta-cell sensitivity to GLP-1 which are related to glucose tolerance of overweight women. In fact, GLP‐1 receptor plays a key role for cardiovascular adaptations to endurance exercise, and the blockade of GLP-1 attenuated acetylcholine‐mediated vasodilation, aortic stiffness and exercise capacity in rats [54]. Unfourtunatelly, there is no data about the role of exercise combined with orlistat on biochemical parameters. However, exercise training remodels subcutaneous adipose tissue and increases the gene expression of lipase and other lipolytic proteins in several tissues [55], [56], [57]. In this context, the indirect evidence obtained here suggests that exercise training likely does not blunt the effects of orlistat treatment. However, clinical trials are needed to directly evaluate the mechanistic interactions between exercise and anti-obesity drugs.

This systematic review has some limitations, primarily due to the small sample sizes in the publications included. Although the limited population analyzed here restricts the generalizability of the results, it highlights the need for further studies focusing exclusively on the combination of physical exercise and pharmacological treatment for obesity. Additionally, our systematic review included two distinct types of anti-obesity drugs – GLP-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1ra) and lipase inhibitors – which may interact differently with exercise training at a physiological level. Although liraglutide and tirzepatide are both injectable medications used to treat diabetes and obesity, they differ in terms of their mechanisms, targets, and clinical effects. Liraglutide is a GLP-1ra that enhances insulin secretion, reducing glucagon release and gastric emptying; these physiological actions are related to the effectiveness to lower Hb1Ac and body weight. On the other hand, tirzepatide is a dual GIP/GLP-1ra, combining the effects and present higher effectiveness on glucose control and weight reduction [10], 11]. Interestingly, the dose of orlistat used in the selected studies was equivalent to those recommended by the World Health Organization. On the other hand, liraglutide and tirzepatide are currently indicated for diabetes treatment by the WHO, and the doses used in the selected clinical studies align with those recommended in studies focusing on weight loss in patients with obesity.

In conclusion, this systematic review and meta-analysis with GRADE assessment is the first to report that exercise training enhances the effects of anti-obesity drugs in obesity management. Notably, exercise training attenuated the loss of fat-free mass typically observed during weight loss induced by pharmacotherapy, contributing to improved physical function and well-being, of individuals with obesity. Moreover, the combination of exercise training and anti-obesity drugs demonstrates superior effects on cardiorespiratory fitness compared to pharmacotherapy alone. However, the certainty of evidence for these outcomes was rated as low to very low. Future clinical trials are essential to address these gaps and provide more robust evidence for obesity management strategies.

Summary and outlook

Here, we systematically reviewed the effect of anti-obesity drug alone or combined with exercise on obesity. Anti-obesity drug combined with exercise had superior effect on body weight management as observed by higher weight loss than pharmacotherapy alone. Furthermore, adding exercise training to anti-obesity pharmacotherapy attenuates fat-free mass loss and increases cardiorespiratory fitness more than anti-obesity drug alone strategies.

Funding source: Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior

Funding source: Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Brazilian agencies CAPES (Finance Code 001), and CNPq through PQ productivity scholarship.

-

Research ethics: The review protocol was registered with PROSPERO under the registration number CRD42023479408.

-

Informed consent: All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Author contributions: All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by GD, BM, IS. The first draft of the manuscript was written by GD and BM, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. FL supervised all steps. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: No.

-

Conflict of interest: No conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: This work was supported by Brazilian agencies CAPES (Finance Code 001), and CNPq through PQ productivity scholarship.

-

Data availability: When requested.

References

1. Heymsfield, SB, Wadden, TA. Mechanisms, pathophysiology, and management of obesity. N Engl J Med 2017;376:254–66. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmra1514009.Search in Google Scholar

2. Gonzalez-Muniesa, P, Martinez-Gonzalez, MA, Hu, FB, Despres, JP, Matsuzawa, Y, Loos, RJF, et al.. Obesity. Nat Rev Dis Prim 2017;3:17034. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2017.34.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

3. Bray, GA, Ryan, DH. Evidence-based weight loss interventions: individualized treatment options to maximize patient outcomes. Diabetes Obes Metabol 2021;23:50–62. https://doi.org/10.1111/dom.14200.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

4. Kheniser, K, Saxon, DR, Kashyap, SR. Long-term weight loss strategies for obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2021;106:1854–66. https://doi.org/10.1210/clinem/dgab091.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

5. Bellicha, A, van Baak, MA, Battista, F, Beaulieu, K, Blundell, JE, Busetto, L, et al.. Effect of exercise training on weight loss, body composition changes, and weight maintenance in adults with overweight or obesity: an overview of 12 systematic reviews and 149 studies. Obes Rev 2021;22:e13256. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.13256.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

6. Binsaeed, B, Aljohani, FG, Alsobiai, FF, Alraddadi, M, Alrehaili, AA, Alnahdi, BS, et al.. Barriers and motivators to weight loss in people with obesity. Cureus 2023;15:e49040. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.49040.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

7. Kebbe, M, Damanhoury, S, Browne, N, Dyson, MP, McHugh, TF, Ball, GDC. Barriers to and enablers of healthy lifestyle behaviours in adolescents with obesity: a scoping review and stakeholder consultation. Obes Rev 2017;18:1439–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12602.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

8. Bessesen, DH, Van Gaal, LF. Progress and challenges in anti-obesity pharmacotherapy. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2018;6:237–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2213-8587(17)30236-x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

9. Dorneles, G, Algeri, E, Lauterbach, G, Pereira, M, Fernandes, B. Efficacy and safety of once-weekly subcutaneous semaglutide in adults with overweight or obesity: systematic review with meta-analysis. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 2024;132:316–27. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-2303-8558.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Shi, Q, Wang, Y, Hao, Q, Vandvik, PO, Guyatt, G, Li, J, et al.. Pharmacotherapy for adults with overweight and obesity: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Lancet 2024;403:e21–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(24)00351-9.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

11. Chakhtoura, M, Haber, R, Ghezzawi, M, Rhayem, C, Tcheroyan, R, Mantzoros, CS. Pharmacotherapy of obesity: an update on the available medications and drugs under investigation. EClinicalMedicine 2023;58:101882. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.101882.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

12. Tak, YJ, Lee, SY. Long-term efficacy and safety of anti-obesity treatment: where do we stand? Curr Obes Rep 2021;10:14–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13679-020-00422-w.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

13. Jobanputra, R, Sargeant, JA, Almaqhawi, A, Ahmad, E, Arsenyadis, F, Webb, DR, et al.. The effects of weight-lowering pharmacotherapies on physical activity, function and fitness: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Obes Rev 2023;24:e13553. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.13553.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

14. Willoughby, D, Hewlings, S, Kalman, D. Body composition changes in weight loss: strategies and supplementation for maintaining lean body mass, a brief review. Nutrients 2018;10:1876. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10121876.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

15. Higgins, JPT, Thomas, J, Chandler, J, Cumpston, M, Li, T, Page, MJ, et al., editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions, version 6.5 (updated August 2024). Cochrane; 2024. Available from: www.training.cochrane.org/handbook.Search in Google Scholar

16. Moher, D, Liberati, A, Tetzlaff, J, Altman, DG, Group, P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009;339:b2535. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2535.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

17. Sterne, JAC, Savovic, J, Page, MJ, Elbers, RG, Blencowe, NS, Boutron, I, et al.. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019;366:l4898. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l4898.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Balshem, H, Helfand, M, Schunemann, HJ, Oxman, AD, Kunz, R, Brozek, J, et al.. GRADE guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:401–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.07.015.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

19. Dorneles, G, Stein, C, Araujo, CP, Parahiba, S, da Rosa, B, Graf, DD, et al.. The impact of an online course on agreement rates of the certainty of evidence assessment using Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation Approach: a before-and-after study. J Clin Epidemiol 2024;172:111407. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2024.111407.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

20. Santesso, N, Glenton, C, Dahm, P, Garner, P, Akl, EA, Alper, B, et al.. GRADE guidelines 26: informative statements to communicate the findings of systematic reviews of interventions. J Clin Epidemiol 2020;119:126–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2019.10.014.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Sterne, JA, Sutton, AJ, Ioannidis, JP, Terrin, N, Jones, DR, Lau, J, et al.. Recommendations for examining and interpreting funnel plot asymmetry in meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2011;343:d4002. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d4002.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

22. Colak, R, Ozcelik, O. Effects of short-period exercise training and orlistat therapy on body composition and maximal power production capacity in obese patients. Physiol Res 2004;53:53–60. https://doi.org/10.33549/physiolres.930279.Search in Google Scholar

23. Lundgren, JR, Janus, C, Jensen, SBK, Juhl, CR, Olsen, LM, Christensen, RM, et al.. Healthy weight loss maintenance with exercise, liraglutide, or both combined. N Engl J Med 2021;384:1719–30. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa2028198.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

24. Ozcelik, O, Ozkan, Y, Algul, S, Colak, R. Beneficial effects of training at the anaerobic threshold in addition to pharmacotherapy on weight loss, body composition, and exercise performance in women with obesity. Patient Prefer Adherence 2015;9:999–1004. https://doi.org/10.2147/ppa.s84297.Search in Google Scholar

25. Bagherzadeh-Rahmani, B, Marzetti, E, Karami, E, Campbell, BI, Fakourian, A, Haghighi, AH, et al.. Tirzepatide and exercise training in obesity. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc 2024;87:465–80. https://doi.org/10.3233/ch-242134.Search in Google Scholar

26. Doggrell, SA. Adding liraglutide to diet and exercise to maintain weight loss - is it worth it? Expet Opin Pharmacother 2022;23:447–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/14656566.2021.2019707.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

27. Oppert, JM, Bellicha, A, Ciangura, C. Physical activity in management of persons with obesity. Eur J Intern Med 2021;93:8–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2021.04.028.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

28. Moreno-Cabanas, A, Morales-Palomo, F, Alvarez-Jimenez, L, Ortega, JF, Mora-Rodriguez, R. Effects of chronic metformin treatment on training adaptations in men and women with hyperglycemia: a prospective study. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2022;30:1219–30. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.23410.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

29. Myette-Cote, E, Terada, T, Boule, NG. The effect of exercise with or without metformin on glucose profiles in type 2 diabetes: a pilot study. Can J Diabetes 2016;40:173–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcjd.2015.08.015.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

30. Newman, AA, Grimm, NC, Wilburn, JR, Schoenberg, HM, Trikha, SRJ, Luckasen, GJ, et al.. Influence of sodium glucose cotransporter 2 inhibition on physiological adaptation to endurance exercise training. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2019;104:1953–66. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2018-01741.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

31. Malin, SK, Nightingale, J, Choi, SE, Chipkin, SR, Braun, B. Metformin modifies the exercise training effects on risk factors for cardiovascular disease in impaired glucose tolerant adults. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2013;21:93–100. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.20235.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

32. Swift, DL, Johannsen, NM, Lavie, CJ, Earnest, CP, Church, TS. The role of exercise and physical activity in weight loss and maintenance. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2014;56:441–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcad.2013.09.012.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

33. Webb, VL, Wadden, TA. Intensive lifestyle intervention for obesity: principles, practices, and results. Gastroenterology 2017;152:1752–64. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2017.01.045.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

34. Jakicic, JM, Rogers, RJ, Church, TS. Physical activity in the new era of antiobesity medications. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2024;32:234–6. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.23930.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

35. Jensen, SBK, Janus, C, Lundgren, JR, Juhl, CR, Sandsdal, RM, Olsen, LM, et al.. Exploratory analysis of eating- and physical activity-related outcomes from a randomized controlled trial for weight loss maintenance with exercise and liraglutide single or combination treatment. Nat Commun 2022;13:4770. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-32307-y.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

36. McCarthy, D, Berg, A. Weight loss strategies and the risk of skeletal muscle mass loss. Nutrients 2021;13:2473. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13072473.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

37. Wilding, JPH, Batterham, RL, Calanna, S, Davies, M, Van Gaal, LF, Lingvay, I, et al.. Once-weekly semaglutide in adults with overweight or obesity. N Engl J Med 2021;384:989–1002. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa2032183.Search in Google Scholar

38. Jastreboff, AM, Aronne, LJ, Ahmad, NN, Wharton, S, Connery, L, Alves, B, et al.. Tirzepatide once weekly for the treatment of obesity. N Engl J Med 2022;387:205–16. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa2206038.Search in Google Scholar

39. Alfaris, N, Waldrop, S, Johnson, V, Boaventura, B, Kendrick, K, Stanford, FC. GLP-1 single, dual, and triple receptor agonists for treating type 2 diabetes and obesity: a narrative review. EClinicalMedicine 2024;75:102782. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2024.102782.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

40. Neeland, IJ, Linge, J, Birkenfeld, AL. Changes in lean body mass with glucagon-like peptide-1-based therapies and mitigation strategies. Diabetes Obes Metabol 2024;26:16–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/dom.15728.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

41. Beavers, KM, Neiberg, RH, Houston, DK, Bray, GA, Hill, JO, Jakicic, JM, et al.. Body weight dynamics following intentional weight loss and physical performance: the look AHEAD movement and memory study. Obes Sci Pract 2015;1:12–22. https://doi.org/10.1002/osp4.3.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

42. Frimel, TN, Sinacore, DR, Villareal, DT. Exercise attenuates the weight-loss-induced reduction in muscle mass in frail obese older adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2008;40:1213–9. https://doi.org/10.1249/mss.0b013e31816a85ce.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

43. Locatelli, JC, Costa, JG, Haynes, A, Naylor, LH, Fegan, PG, Yeap, BB, et al.. Incretin-based weight loss pharmacotherapy: can resistance exercise optimize changes in body composition? Diabetes Care 2024;47:1718–30. https://doi.org/10.2337/dci23-0100.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

44. Lim, C, Nunes, EA, Currier, BS, McLeod, JC, Thomas, ACQ, Phillips, SM. An evidence-based narrative review of mechanisms of resistance exercise-induced human skeletal muscle hypertrophy. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2022;54:1546–59. https://doi.org/10.1249/mss.0000000000002929.Search in Google Scholar

45. Vinel, C, Lukjanenko, L, Batut, A, Deleruyelle, S, Pradere, JP, Le Gonidec, S, et al.. The exerkine apelin reverses age-associated sarcopenia. Nat Med 2018;24:1360–71. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-018-0131-6.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

46. Gorgojo-Martinez, JJ, Basagoiti-Carreno, B, Sanz-Velasco, A, Serrano-Moreno, C, Almodovar-Ruiz, F. Effectiveness and tolerability of orlistat and liraglutide in patients with obesity in a real-world setting: the XENSOR Study. Int J Clin Pract 2019;73:e13399. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcp.13399.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

47. Leventhal-Perek, S, Shani, M, Schonmann, Y. Effectiveness and persistence of anti-obesity medications (liraglutide 3 mg, lorcaserin, and orlistat) in a real-world primary care setting. Fam Pract 2023;40:629–37. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmac141.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

48. Sanchez-Delgado, JC, Jacome-Hortua, AM, Uribe-Sarmiento, OM, Philbois, SV, Pereira, AC, Rodrigues, KP, et al.. Combined effect of physical exercise and hormone replacement therapy on cardiovascular and metabolic health in postmenopausal women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Braz J Med Biol Res 2023;56:e12241. https://doi.org/10.1590/1414-431x2023e12241.Search in Google Scholar

49. Figueiredo, C, Padilha, CS, Dorneles, GP, Peres, A, Kruger, K, Rosa-Neto, JC, et al.. Type and intensity as key variable of exercise in metainflammation diseases: a review. Int J Sports Med 2022;43:743–67. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-1720-0369.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

50. Barry, VW, Baruth, M, Beets, MW, Durstine, JL, Liu, J, Blair, SN. Fitness vs. fatness on all-cause mortality: a meta-analysis. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2014;56:382–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcad.2013.09.002.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

51. Peres, A, Dorneles, GP, Dias, AS, Vianna, P, Chies, JAB, Monteiro, MB. T-cell profile and systemic cytokine levels in overweight-obese patients with moderate to very-severe COPD. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 2018;247:74–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resp.2017.09.012.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

52. Dorneles, GP, da Silva, I, Boeira, MC, Valentini, D, Fonseca, SG, Dal Lago, P, et al.. Cardiorespiratory fitness modulates the proportions of monocytes and T helper subsets in lean and obese men. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2019;29:1755–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.13506.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

53. Akerstrom, T, Stolpe, MN, Widmer, R, Dejgaard, TF, Hojberg, JM, Moller, K, et al.. Endurance training improves GLP-1 sensitivity and glucose tolerance in overweight women. J Endocr Soc 2022;6:bvac111. https://doi.org/10.1210/jendso/bvac111.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

54. Scalzo, RL, Knaub, LA, Hull, SE, Keller, AC, Hunter, K, Walker, LA, et al.. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor antagonism impairs basal exercise capacity and vascular adaptation to aerobic exercise training in rats. Physiol Rep 2018;6:e13754. https://doi.org/10.14814/phy2.13754.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

55. Ahn, C, Ryan, BJ, Schleh, MW, Varshney, P, Ludzki, AC, Gillen, JB, et al.. Exercise training remodels subcutaneous adipose tissue in adults with obesity even without weight loss. J Physiol 2022;600:2127–46. https://doi.org/10.1113/jp282371.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

56. Kersten, S. Physiological regulation of lipoprotein lipase. Biochim Biophys Acta 2014;1841:919–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbalip.2014.03.013.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

57. Seip, RL, Angelopoulos, TJ, Semenkovich, CF. Exercise induces human lipoprotein lipase gene expression in skeletal muscle but not adipose tissue. Am J Physiol 1995;268:E229–36. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpendo.1995.268.2.e229.Search in Google Scholar

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/teb-2024-0039).

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter on behalf of Shangai Jiao Tong University and Guangzhou Sport University

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Section: Integrated exercise physiology, biology, and pathophysiology in health and disease

- Validation of marathon performance model based on physiological factors in world-class East African runners: a case series

- Mitochondrial and cardiovascular responses to aerobic exercise training in supine and upright positions in healthy young adults: a randomized parallel arm trial

- Exercise-induced neurogenesis through BDNF-TrkB pathway: implications for neurodegenerative disorders

- The role of osteoprotegerin (OPG) in exercise-induced skeletal muscle adaptation

- Section: Personalized and advanced exercise prescription for health and chronic diseases

- Impact of early and late morning supervised blood flow restriction training on body composition and skeletal muscle performance in older inactive adults

- Section: Interaction of exercise with diet, nutrition and/or medication

- Anti-obesity drugs alone or combined with exercise training in the management of obesity: a systematic review with meta-analysis

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Section: Integrated exercise physiology, biology, and pathophysiology in health and disease

- Validation of marathon performance model based on physiological factors in world-class East African runners: a case series

- Mitochondrial and cardiovascular responses to aerobic exercise training in supine and upright positions in healthy young adults: a randomized parallel arm trial

- Exercise-induced neurogenesis through BDNF-TrkB pathway: implications for neurodegenerative disorders

- The role of osteoprotegerin (OPG) in exercise-induced skeletal muscle adaptation

- Section: Personalized and advanced exercise prescription for health and chronic diseases

- Impact of early and late morning supervised blood flow restriction training on body composition and skeletal muscle performance in older inactive adults

- Section: Interaction of exercise with diet, nutrition and/or medication

- Anti-obesity drugs alone or combined with exercise training in the management of obesity: a systematic review with meta-analysis