Abstract

This article presents a typological survey of patterns of adnominal possession in 85 Austronesian and Papuan languages of Linguistic Wallacea, providing a more granular picture of possessive constructions in the region than previously available. The features treated are possessive word orders, locus of possessive marking, possessive classification systems, and multifunctionality of adnominal possessive markers. Unlike their relatives to the west, the Austronesian languages of Linguistic Wallacea tend to show Possessor-Possessum ordering and have an alienability distinction, often instantiated through contrastive direct and indirect constructions. In terms of broad typological features, contact with and shift from Papuan languages can be shown to have caused widespread remodeling of the adnominal possessive patterns in Austronesian languages of the area. However, their distribution and formal manifestations make clear that they are not the result of a single Papuan contact event in a single Austronesian common ancestor but must go back to multiple localized contact events across Linguistic Wallacea. Subregional patterns are often found clustered in smaller groups of languages and are the result of local processes of contact and change including morphologization and morphological loss. These become apparent when tracking changes in historically related form-function pairs in possessive constructions.

1 Introduction

Taking in the Papuan and Austronesian languages of eastern Nusantara including the Minor Sundic Islands east of Lombok, Timor-Leste, Maluku, the Bird’s Head and Neck of New Guinea, and the islands and coasts of Cenderawasih Bay, Linguistic Wallacea is a convergence area in its own right and, at the same time, forms the western extreme of the larger area of Linguistic Melanesia (Schapper 2015). This article provides an in-depth survey of the structural characteristics of adnominal possessive constructions in Linguistic Wallacea with reference to the broader Linguistic Melanesian context.

Important early observations by scholars such as Brandes (1884), Kanski and Kasprusch (1931), Schmidt (1900), van der Veen (1915), and van Hoëvell (1877) on possessive constructions in both the Austronesian and Papuan languages of the area have meant that possession has always been prominent in the literature on Linguistic Wallacea. And whilst the broad patterns of basic possessive constructions across the area are well known (see, e.g., Klamer et al. 2008: 116–130 for a typical overview), previous treatments have been limited in a number of ways. First, the focus on the characterization of basic possessive constructions in the broadest of typological terms has resulted in a glossing over of the many subtle variations in possessive constructions across Wallacean languages. Second, the limited availability of descriptive materials for many linguistic groups within Linguistic Wallacea until recently meant that previous discussions could often only bring together scattered individual data points, noting aberrant patterns where they appeared but little more. This resulted in smaller sub-regional patterns in possessive constructions and subtle changes in possessive constructions across neighboring languages being overlooked. The surge in the production of linguistic descriptions in the last 15 years has, however, brought to light more distributional and constructional details of morphosyntax across groups of geographically and genealogically related languages in Linguistic Wallacea.

In this survey, we aim to develop a more granular picture of possessive constructions in Linguistic Wallacea languages than hitherto. In doing so, we treat patterns in adnominal possessive word orders, locus of possessive marking, possessive classification systems, and multifunctionality of adnominal possessive markers. We draw attention to the many subregional patterns in possessive constructions that are of typological interest and, for many, seek to understand them as the result of different processes of diachronic change, with particular reference to the role of contact. Across related languages, we also look for changes in historically related form-function pairs in the possessive domain and use these in order to posit progressive historical changes in the morphosyntax of possessive constructions of Wallacean languages.

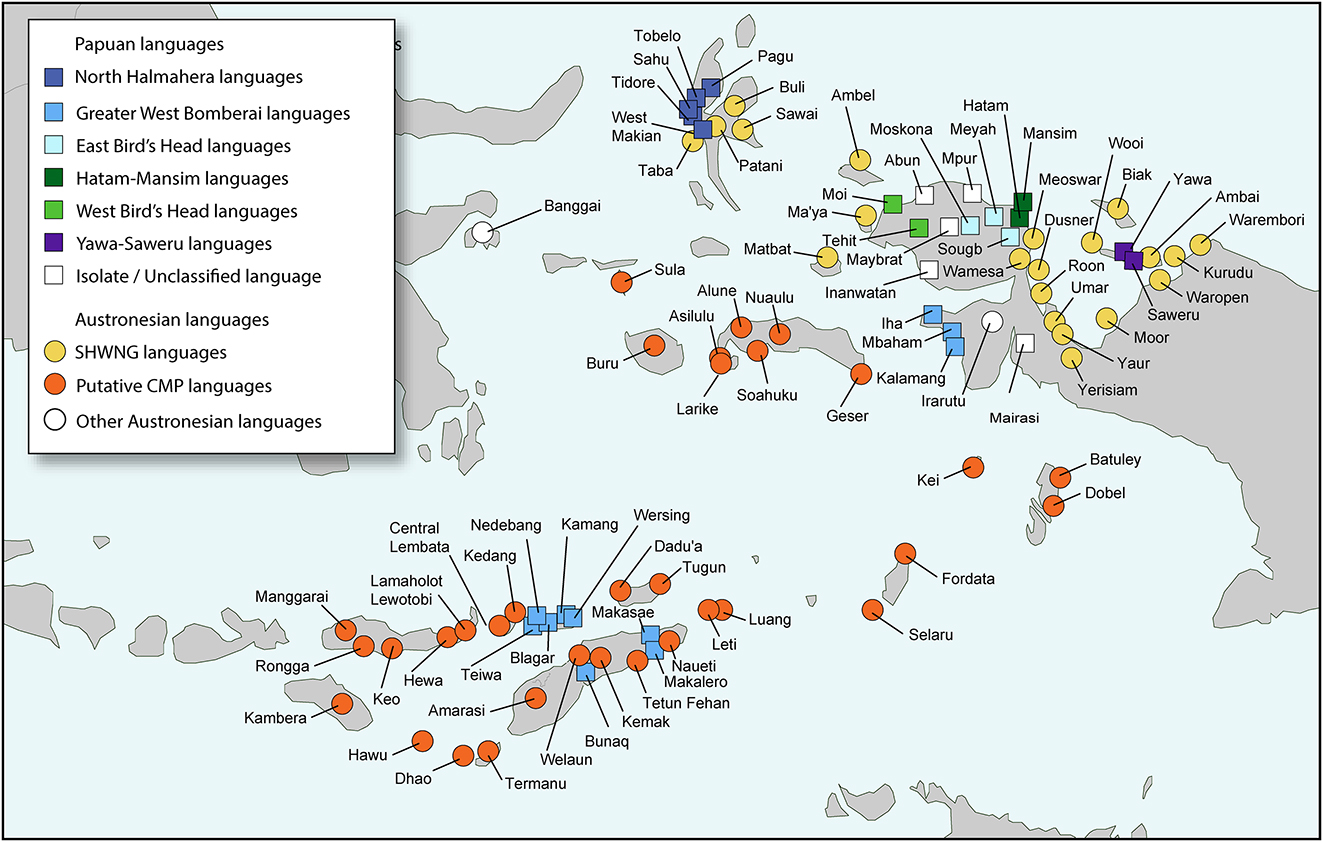

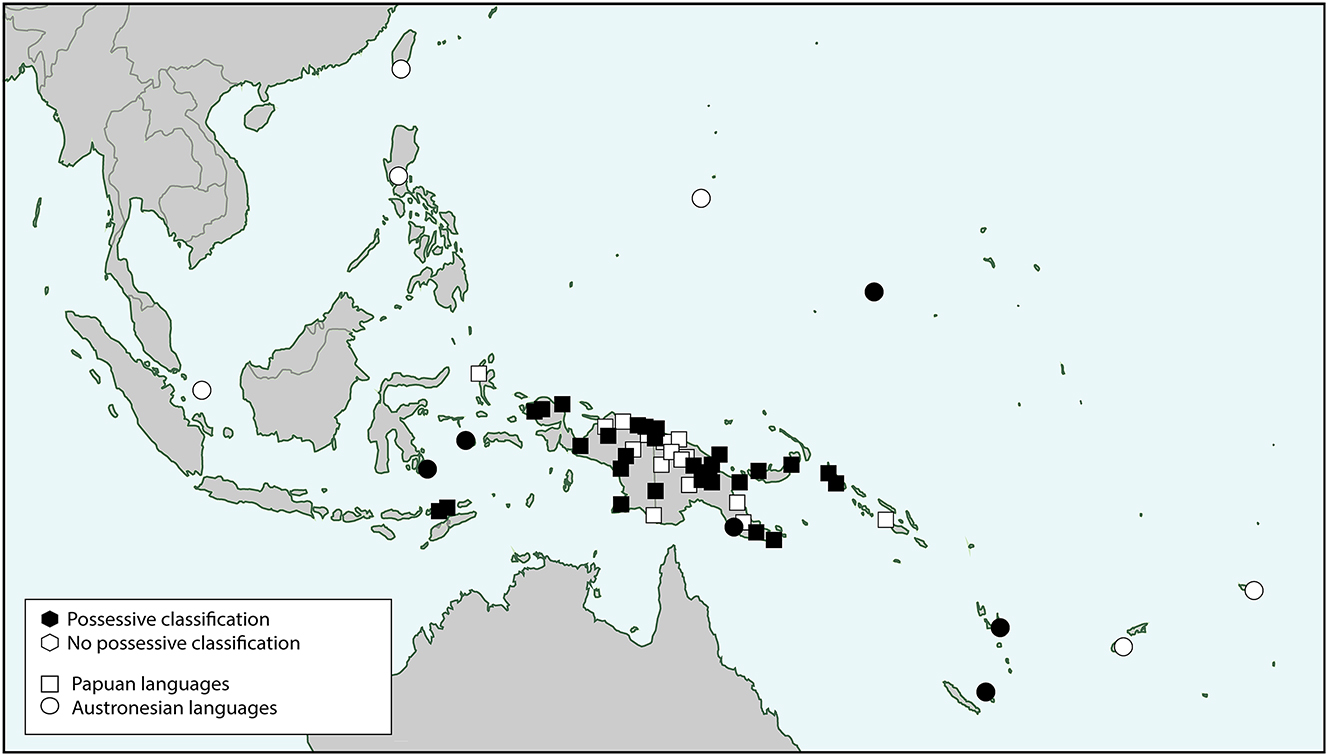

Our survey is based on a sample of 85 languages from across Linguistic Wallacea. The languages have been chosen as representative of the genetic and areal diversity of the area, although the availability of adequate grammatical descriptions also played a role in the compilation of the sample. Map 1 presents an overview of the languages sampled. A full list of languages and the data sources for them is provided in Appendix A.

Languages discussed in this article.

While the higher-order classification of these languages is still largely unsettled, the details of classification are not important to our arguments here, and where we discuss historical developments, we rely only on well-supported family relationships. For the most part, Papuan genealogical classifications in the area, particularly for larger familial groupings that exist in the literature such as West Papuan or Trans New Guinea, have not been subject to rigorous historical analysis and widely agreed upon families are limited to languages with very obvious relationships.[1] In the Austronesian family, the South Halmahera-West New Guinea (SHWNG) branch and its membership are solidly established, but Central Malayo-Polynesian (CMP), while widely cited in the literature, is contested by linguists of different persuasions (see, e.g., debate between Blust 2009; Donohue and Grimes 2008). Proto-SHWNG is a sister language to Proto-Oceanic within the Eastern Malayo-Polynesian subgroup. Proto-Eastern Malayo-Polynesian has, in turn, been classified by Blust (1993) as grouping with CMP to comprise the Central-Eastern Malayo-Polynesian (CEMP) subgroup. The Austronesian language Irarutu is unlikely to be part of the SHWNG subgroup (Kamholz 2014, forthcoming), but has not yet been solidly classified elsewhere. We also include one language belonging to a western subgroup of the Austronesian family ‒ Banggai, spoken on the western edge of Linguistic Wallacea, belongs to the Celebic subgroup, but in terms of its adnominal possessive structures is very much a Wallacean language. The groupings used here should be seen as a convenient shorthand rather than statements of definitive genealogical relationships. Where examples are given in the text, further genealogical classification is given wherever possible.

Throughout this article, we follow the standard practice in the linguistic literature of using the terms “possessive” and “possession” to refer to all kinds of adnominal possessive constructions regardless of whether the semantics is one of literal possession (Lichtenberk 1985: 94; Lynch 1973; Pawley 1973: 153; among many others). We use the terms “possessor” (Psr) for the entity that possesses and “possessum” (Psm) for the entity that is possessed.

The article is structured as follows. The order of possessor and possessum is discussed in Section 2. The locus of bound possessive markers is treated in Section 3. Possessive classification is discussed in Section 4. Patterns of multifunctionality in possessive markers are discussed in Section 5. Section 6 concludes.

2 Adnominal possessive word order

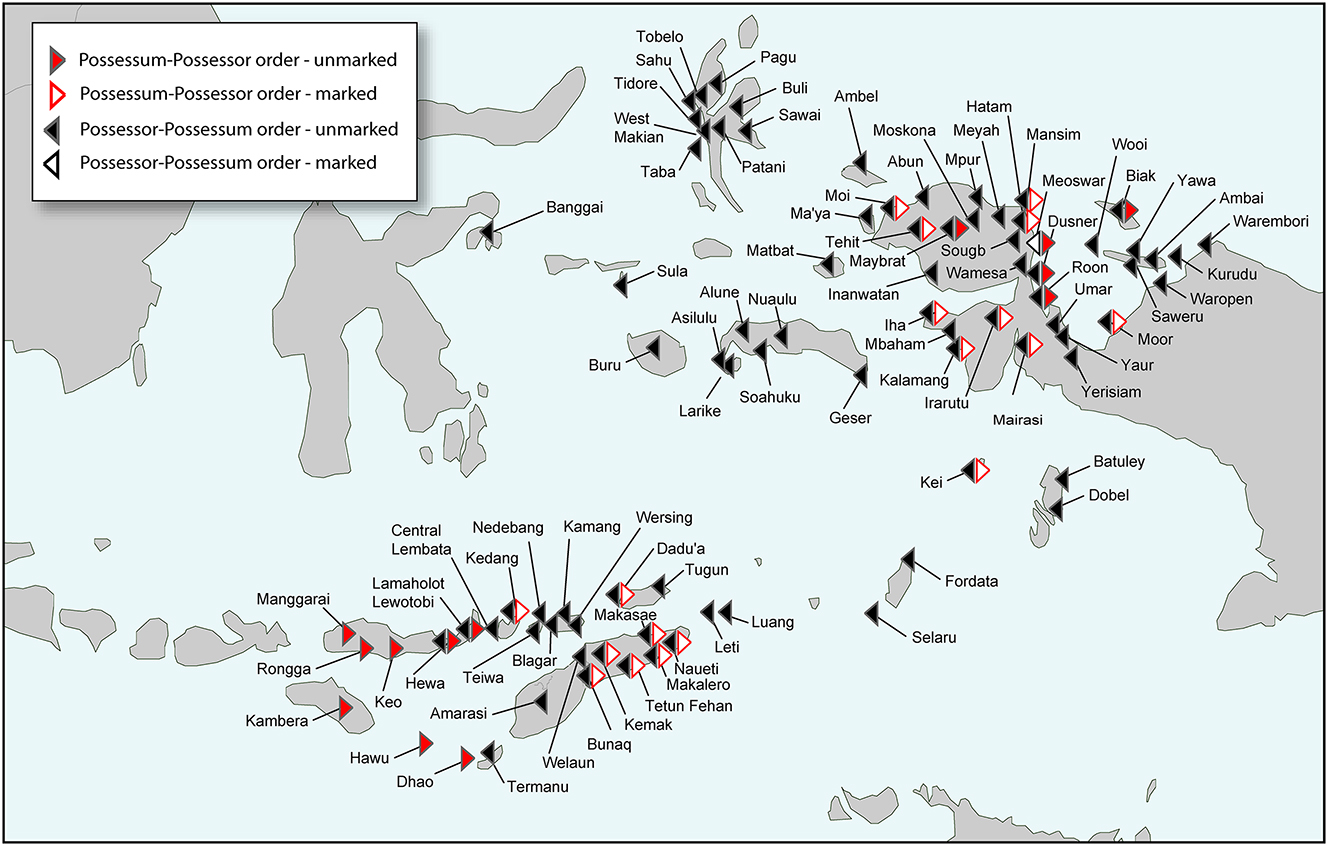

The most famous and perhaps first recognized isogloss delimiting Linguistic Wallacea is the so-called “reversed genitive”. While the possessor typically follows the possessum in languages of western Indonesia and the Philippines, Brandes (1884) observed that the order of the noun and the possessor is “reversed” in the Austronesian (An) languages of Linguistic Wallacea with the possessor preceding the noun it possesses. Map 2 shows that the basic ordering of possessor and possessum across much of Linguistic Wallacea follows the pattern observed by Brandes. At the same time, Map 2 also makes clear that many languages in the region that have a basic preposed possessor also permit a possessor to be postposed in certain contexts.

Ordering of possessor and possessum in the languages of Wallacea.

In Section 2.1, we give an overview of the historical linguistic significance of the preposed possessor in Linguistic Wallacea. In Section 2.2, we discuss the different splits in possessor encoding that are found across Linguistic Wallacea and show that they are geographically and genealogically skewed.

2.1 Basic possessive word order

The basic order of possessor and possessum throughout much of Linguistic Wallacea sees the possessor precede the possessum. A typical example of Psr-Psm order comes from Wamesa, a member of the South Halmahera-West New Guinea branch of Austronesian spoken along the south-western coast of Cenderawasih Bay. Wamesa has three main possessive constructions, all of which see the possessor preceding the possessum: a direct, morphologically marked inalienable construction for most body parts and kin terms (1a); an indirect, default or alienable construction using the verb ne ‘to have’ as a linker (1b); and a third construction with no possessive marking used primarily for part/whole constructions (1c).

| Wamesa (An, SHWNG, Yapen) | |||

| a. | [siate] Psr | [ se - tama - mi =pa-sia] Psm | |

| they | 3pl.hum-father-poss.pl=det-pl.hum | ||

| ‘their fathers’ | |||

| b. | [wonggei] Psr | n <i> e | [ponori=pa-si] Psm |

| cassowary | <3sg>poss | egg=det-pl | |

| ‘the cassowary’s eggs’ | |||

| c. | [ai=pa-i] Psr | [vavo=pa] Psm | |

| tree=det-sg | top=det | ||

| ‘the top of the tree’ | |||

| (Gasser 2014: 220, 241; fieldnotes) | |||

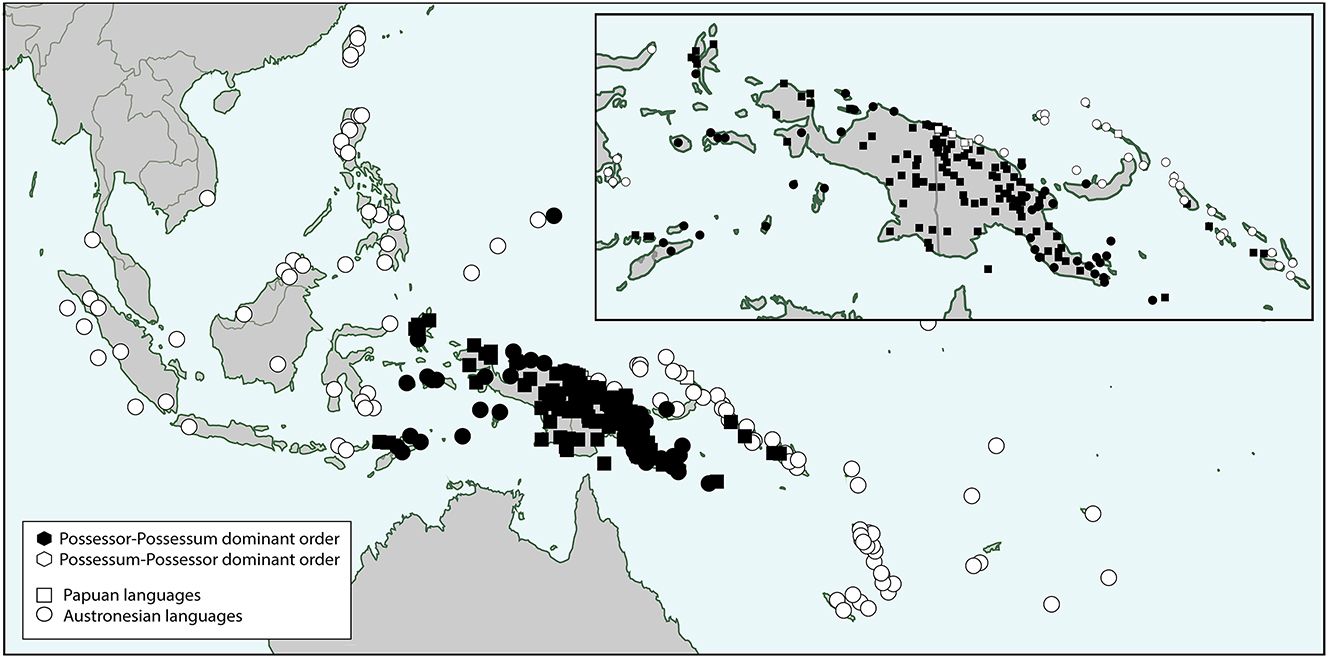

While the Psr-Psm order is typical of all Papuan languages, not just those within Linguistic Wallacea (“the recognised Papuan order” as Reesink 1999: 81 calls it), it is not the typical order of possessor and possessum in Austronesian. For most languages of the Austronesian family, the possessor follows the possessum in the basic possessive construction. It is only in the vicinity of New Guinea that we find a concentration of Austronesian languages that “reverse” the typical ordering to Psr-Psm (Map 3). It is considered so important within the family that Himmelmann (2005) names one of his two major non-Oceanic Austronesian language types “preposed possessor languages.”

Basic ordering of possessor and possessum in the New Guinea area (adapted from Schapper 2020a: 488).

The reversal of the basic possessive order in Austronesian languages is widely agreed to be the result of contact with or shift from Papuan languages (Donohue 2007: 352–355). East of New Guinea it is only the Austronesian languages closest to the New Guinea mainland that have the Papuan possessive order (see inset of Map 3). But the change in possessive ordering in Austronesian languages of Linguistic Wallacea is striking for how far it extends from New Guinea, and speaks to the wide-ranging Papuan influence that underpinned the formation of the linguistic area.

It is important to note that the reversal of possessive ordering in Austronesian languages within Linguistic Wallacea was not a one-time change that occurred in a common ancestor. Rather, it is clear from the distribution of the order over established subgroups that it has erratically diffused into the Austronesian languages of the area. For example, the languages of the Sumba-Hawu subgroup, though they fall within Linguistic Wallacea based on other features, display the conservative Austronesian postposed possessor order, while their closest relatives in the Flores-Lembata subgroup (Fricke 2019: 229–233) have a mixture of preposed and postposed orders (discussed further in Section 2.2.1). At the same time, the preposed possessor order has diffused beyond the boundaries of CEMP languages. Banggai, spoken at the western perimeter of Linguistic Wallacea and subgrouping with western Austronesian languages in Sulawesi, also has preposed possessors (Schapper and McConvell forthcoming).

2.2 Splits in possessive word orders

The basic Psr-Psm order of possessive constructions in Linguistic Wallacea is well known in the literature. What is little discussed are the numerous deviations from this pattern whereby languages may allow the possessor to be postposed in certain contexts. As can be seen in Map 2, most languages with splits in possessive word orders are geographically clustered, which is potentially indicative of local processes of language contact and change. Here we will discuss the splits in possessor posing in Linguistic Wallacea under two broad labels: splits in possessor posing involving nominal versus pronominal possessors (Section 2.2.1); and splits conditioned by the semantics of the possessive relationship (Section 2.2.2).

2.2.1 Noun-pronoun splits in possessor posing

Several languages of Linguistic Wallacea show splits in the ordering of possessor and possessum that interact with whether the possessor is encoded with a noun or a pronoun. Postposed pronominal possessor constructions are highly varied in their function and frequency across languages, but they are united by the fact that in each language it is specifically pronouns (or what have been described as pronouns) and not nouns that occur in the postposed construction. In some languages, the postposed construction is basic in some contexts, while in others it is an infrequent, pragmatically marked alternative to the preposed possessor construction.

These splits appear in two main geographic areas. The first cluster is represented by the closely related Austronesian languages of eastern Flores and the Solor archipelago. As already alluded to in Section 2.1, the languages here are transitional between the preposed and postposed possessor types. At least three lects ‒ Hewa, Lamaholot Lewotobi and Lamaholot Solor ‒ have Psm-Psr order when the possessor is a free pronoun, but Psr-Psm order when it is a lexical noun, as illustrated in (2).

| Lamaholot Lewotobi (An, Flores-Lembata) | |||||

| a. | oto | goʔẽ | b. | Hugo | laŋoʔ=kə̃ |

| car | 1sg.poss | Hugo | house=poss | ||

| ‘my car’ | ‘Hugo’s house’ | ||||

| (Nagaya 2015) | |||||

Kedang, a closely related language spoken in north Lembata, has a basic preposed possessor for both nouns and pronouns (3a), but has a postposed possessive pronoun as a marked alternative that places contrastive focus on the identity of the possessor (3b).

| Kedang (An, Flores-Lembata) | |||||

| a. | koʔ | huna | b. | labur | koʔo |

| 1sg.poss | house | dress | 1sg.poss | ||

| ‘my house’ | ‘my dress’ | ||||

| (Samely 1991: 76‒77) | |||||

See Schapper and McConvell (forthcoming) for more discussion of this pattern.

The second area where splits are found is in Bomberai and the Bird’s Head of New Guinea, with multiple languages attesting marked constructions with postposed possessive pronouns. In Bomberai, postposed possessive pronouns have forms distinct from preposed pronouns. In Kalamang, spoken on and just off the coast of Bomberai, the basic possessive construction has a possessive suffix on the possessum (4a), which can co-occur with a preposed noun referring to the possessor (4b). But in a second, more marked construction, a free possessive pronoun denoting the possessor is postposed to the possessum and the suffix is omitted (4c). Visser (2020) does not provide any information on what motivates use of the postposed possessive pronoun in Kalamang.

| Kalamang (Papuan, Greater West Bomberai) | ||||

| a. | kewe -un | b. | Malik | kewe -un |

| house-3.poss | Malik | house-3.poss | ||

| ‘his/her/their house’ | ‘Malik’s house’ | |||

| c. | kewe | main | ||

| house | 3.poss | |||

| ‘his/her/their house’ | |||||

| (Visser 2020: 181, 237, 250) | |||||

A similar construction with a dedicated postposed possessive pronoun is found in a nearby Austronesian language, Irarutu, also spoken on Bomberai. Normally, possessors are preposed in Irarutu (5a), but a special form of possessor pronoun occurs exclusively in the postposed position (5b). Jackson (2014) states that the postposed construction emphasizes the possessor.

| Irarutu (An, Unclassified) | |||||

| a. | ja | skripsi | b. | skripsi | jari |

| 1sg.poss | thesis | thesis | 1sg.poss | ||

| ‘my thesis’ | ‘my thesis’ | ||||

| (Jackson 2014: 121) | |||||

On the Bird’s Head, several Papuan languages show variable posing of free possessive pronouns. For example, in Hatam, a language of the eastern Bird’s Head, preposed possessors are most frequent (6a), but possessor pronouns can also be postposed (6b) with no apparent change in meaning, though this order is less common (Reesink 1999: 81). An optional possessor NP or pronoun may also precede the possessum, as in (6c). Mansim, Hatam’s only relative, shows the same pattern, but with a preference for the possessor pronoun to follow the possessum (Reesink 2002a: 287).

| Hatam (Papuan, Hatam-Mansim) | |||||

| a. | ni-de | minsien(=nya) | b. | misien | ni-de =nya |

| 3sg-poss | dog(=pl) | dog | 3sg-poss=pl | ||

| ‘his dogs’ | ‘his dogs’ | ||||

| c. | Urbanus | ni-de | ig | ||

| Urbanus | 3sg-poss | house | |||

| ‘Urbanus’ house’ | |||||

| (Reesink 1999: 62, 81) | |||||

The West Bird’s Head languages also allow free possessor pronouns to be preposed or postposed with no apparent change in meaning. For example, Flassy (1991: 13) notes that in Tehit “there does not seem to be a difference in meaning” between the construction with the preposed possessor (7a) and that with the postposed one (7b).[2]

| Tehit (Papuan, West Bird’s Head) | |||||

| a. | teda | mbyele | b. | mbyele | teda |

| 1sg.poss | garden | garden | 1sg.poss | ||

| ‘my garden’ | ‘my garden’ | ||||

| (Flassy 1991: 13) | |||||

The Austronesian languages of the Biakic subgroup, spoken in Cenderawasih Bay and the Raja Ampat Islands, display an apparent split in the placement of nominal and pronominal possessors (Schapper and McConvell forthcoming). Possessors of inalienable nouns in Biakic are introduced by what descriptions refer to as “possessive pronouns” that are inflected for the person/number of the possessor and postposed to the possessum (8). Where a noun is used to express the possessor of an alienable noun, it is preposed, while the so-called pronoun stays in the postnominal position (8b). The “possessive pronoun” cannot be omitted from a possessive construction.

| Dusner (An, SHWNG, Biakic) | |||||||

| a. | wak | yerya | b. | Nelwan | wak | vyerya | |

| wak | y-ve-rya | Nelwan | wak | v<i>e-rya | |||

| boat | 1sg-poss-det.3sg | Nelwan | boat | <3sg>poss-det.3sg | |||

| ‘my boat’ | ‘Nelwan’s boat’ | ||||||

| (Dalrymple and Mofu 2012: 24–25) | |||||||

Though we include them here with other pronominal constructions, Schapper and McConvell (forthcoming) suggest that the apparently unusual possessive word order behavior in Biakic languages reflects poor terminology. They argue that Biakic “possessive pronouns” are not pronominal at all and would be better named “possessive determiners”. This label also fits better with the fact that these items agree with both possessor and possessum. Historically, they seem to have arisen through grammaticalization of a verb ve in an object relative clause (Bach 2021; see also Section 5.2).

In one Biakic language, the postposed possessive determiner seems to be increasingly “dragging” nominal possessors into a postposed position. In Meoswar, a noun encoding a possessor can either occur before the possessum as in other Biakic languages (9a), or following the possessum but preceding the possessive determiner (9b). Bach (2021) argues that this difference is actually the result of the different origins of possessive determiners in Meoswar, where they build on a full pronoun followed by a clitic determiner or demonstrative, versus the other Biakic languages, Biak, Dusner, and Roon, which use ve.

| Meoswar (An, SHWNG, Biakic) | |||

| a. | Agusi | rum | a-i-rirya |

| Agus | house | poss-3sg-det.sg | |

| ‘Agus’ house’ | |||

| b. | rum | Agusi | a-i-rirya |

| house | Agus | poss-3sg-det.sg | |

| ‘Agus’ house’ | |||

| (Bach 2021: 336) | |||

The reader is referred to Gil (this volume) for an in-depth discussion of possessive constructions in the Biakic language Roon.

Reesink (2005: 198–199) attributes the appearance of Psm-Psr word order in Papuan languages of the Bird’s Head to influence from Austronesian languages. However, this suggestion cannot be sustained. The preceding discussion has shown that Austronesian languages as well as Papuan ones show the reversal of basic possessive order in marked constructions across Linguistic Wallacea. In the wider area of Island Southeast Asia, reversals in the order of possessor and possessum are found widely in marked possessive constructions (Schapper and McConvell forthcoming). Whilst marked possessive constructions can represent the diachronic source for changes in possessive word orders over time, the reversals are so common in marked constructions that contact cannot be convincingly invoked to explain simply any word order change in possessive constructions.[3]

2.2.2 Lexico-semantic splits in possessor posing

Splits in the ordering of possessor and possessum can be based on lexico-semantics of the possessive relation. In the Bird’s Head, Maybrat stands out for having possessors of nouns belonging to the inalienable class preposed (10a), and those of nouns belonging to the alienable class postposed (10b). Notice the separate constructions used for encoding possessors with nouns of the different lexical classes.

| Maybrat (Papuan, isolate) | |||||

| a. | Yan | y-asoh | b. | fane | ro- Yan |

| Yan | 3sg.m-mouth | pig | poss-Yan | ||

| ‘Yan’s mouth’ | ‘Yan’s pig’ | ||||

| (Dol 2007: 85, 89) | |||||

The greatest concentration of languages with a split in the possessor ordering based on lexico-semantics is in the languages of eastern Timor. In both Papuan and Austronesian languages here, both inalienable and alienable nouns normally have their possessor preposed. However, the possessor of an alienable noun can also be postposed where the possessor is non-prototypical and the possessive relationship not ownership-like.

Different constructions for pre- and postposed possessors of alienable nouns are used, for example, in Dadu’a, where a preposed possessor is indexed by an agreement prefix (11a), while a postposed possessor is followed by a free possessive marker nii (11b). Penn (2006: 47–48) describes preposed possessors as being more referential and used for possessive relationships that are ownership-like, while postposed possessors are more descriptive attributes than proper possessors. Tetun also has structurally similar postposed possessive structures with these same semantic connotations (van Klinken 1999: 151–152; Williams-van Klinken et al. 2002: 35–36). Similar postposed constructions are also found in Naueti (cf. Veloso 2016: 57) and other languages of the Eastern Timor subgroup, but their functions are not well described.

| Dadu’a (An, Eastern Timor) | ||||||

| a. | Maria | ni- barane | b. | huhu | rare-Timor | nii |

| Maria | 3sg-husband | mountain | land-Timor | poss | ||

| ‘Maria’s husband | ‘mountains of Timor’ | |||||

| (Penn 2006: 48, 59) | ||||||

In Kemak, the same construction is used for both preposed and postposed possessors. The preposed possessor position expresses a typical possessive relationship, where the child is the owner of the maize (12a). The postposed possessor position expresses that the child is the prospective possessor of the maize, but not the person to whom it necessarily belongs (12b).

| Kemak (An, Central Timor) | ||||||

| a. | Preposed possessor | |||||

| au | tere | [ anamugu | siana | no ] Psr | [sele] Psm | |

| 1sg | cook | child | dem | 3sg.poss | maize | |

| ‘I cook this child’s maize (i.e., the maize belonging to the child).’ | ||||||

| b. | Postposed possessor | |||||

| au | tere | [sele] Psm | [ anamugu | siana | no ] Psr | |

| 1sg | cook | maize | child | dem | 3sg.poss | |

| ‘I cook maize for this child.’ | ||||||

| (Schapper 2009) | ||||||

The neighboring Papuan language, Bunaq, a member of the Timor-Alor-Pantar (TAP) family, also allows postposing of possessors in two contexts. The first postposed context is where the “possessor” refers to the entity in connection with which the possessum is intended to be used, as in (13a). A preposed possessor, by contrast, must denote a current possessive relationship in which the possessor is the owner/controller of the possessum (13b). A post-posed ‘destination’ possessor always has a non-specific, hypothetical reference, while a preposed ‘owner’ possessor has a specific referent.

| Bunaq (Papuan, Greater West Bomberai, TAP) | ||||

| a. | tais | pana | gie | ba |

| cloth | female | 3.poss | art.inan | |

| ‘cloth for a woman’ | ||||

| b. | pana | gie | tais | ba |

| female | 3.poss | cloth | art.inan | |

| ‘a/the woman’s cloth’ | ||||

| (Schapper fieldnotes) | ||||

The second context in which postposed possessors occur is where they express an entity in which the possessum originates. For instance, the postposed possessor bei mil ‘ancestors’ in (14) is the origin of the marriage practices that are adhered to. If this possessor were preposed, it would suggest that marriage was the property of the Bunaq people of the past and not those of the present day, i.e., the ancestors are not the origin of an entity in the present day but the owners of an entity that no longer exists.

| Bunaq (Papuan, Greater West Bomberai, TAP) | ||||||

| Tapi | ton | en | bei | mil | gie | h-alolo. |

| but | marriage | person | ancestor | coll | 3.poss | 3.inan-follow |

| ‘But (we) follow the marriage of the ancestors.’ i.e., ‘We conform to the marriage traditions which come from our ancestors.’ | ||||||

| (Schapper fieldnotes) | ||||||

A similar range of functions for postposed possessors is found in the related Papuan language, Makasae (Correia 2011: 81–84) spoken at the eastern tip of Timor.

3 Locus of bound possessive markers

In this section, we discuss possessive markers that take the form of affixes or clitics (collectively, here “bound markers”) and the elements to which they attach. We use the terms “possessor-marking” and “possessum-marking” as shorthand to refer to those markers that are hosted by the possessor and the possessum, respectively.[4] We rely here on the morphological categorizations (prefix, clitic, root) given by the original authors, though in many cases categories such as “clitic” are not defined, and often no justification is given for categorizing a form in a particular way. In instances where sources disagree about the morphological status of a given form, we follow the more recent one.

Despite the congruent terminology, “possessor-marking” and “possessum-marking” constructions are not mirror images of one another but rather represent quite different constructions. The possessor-marking constructions, rare in Linguistic Wallacea, might in some grammatical traditions be referred to as “genitives”:[5] They mark the construction as one of adnominal possession and sometimes have other case-related uses, but have no (co-)referential properties and are invariant within the language. The possessum-marking constructions, by contrast, index features, usually person, number, and sometimes animacy, of the possessor.

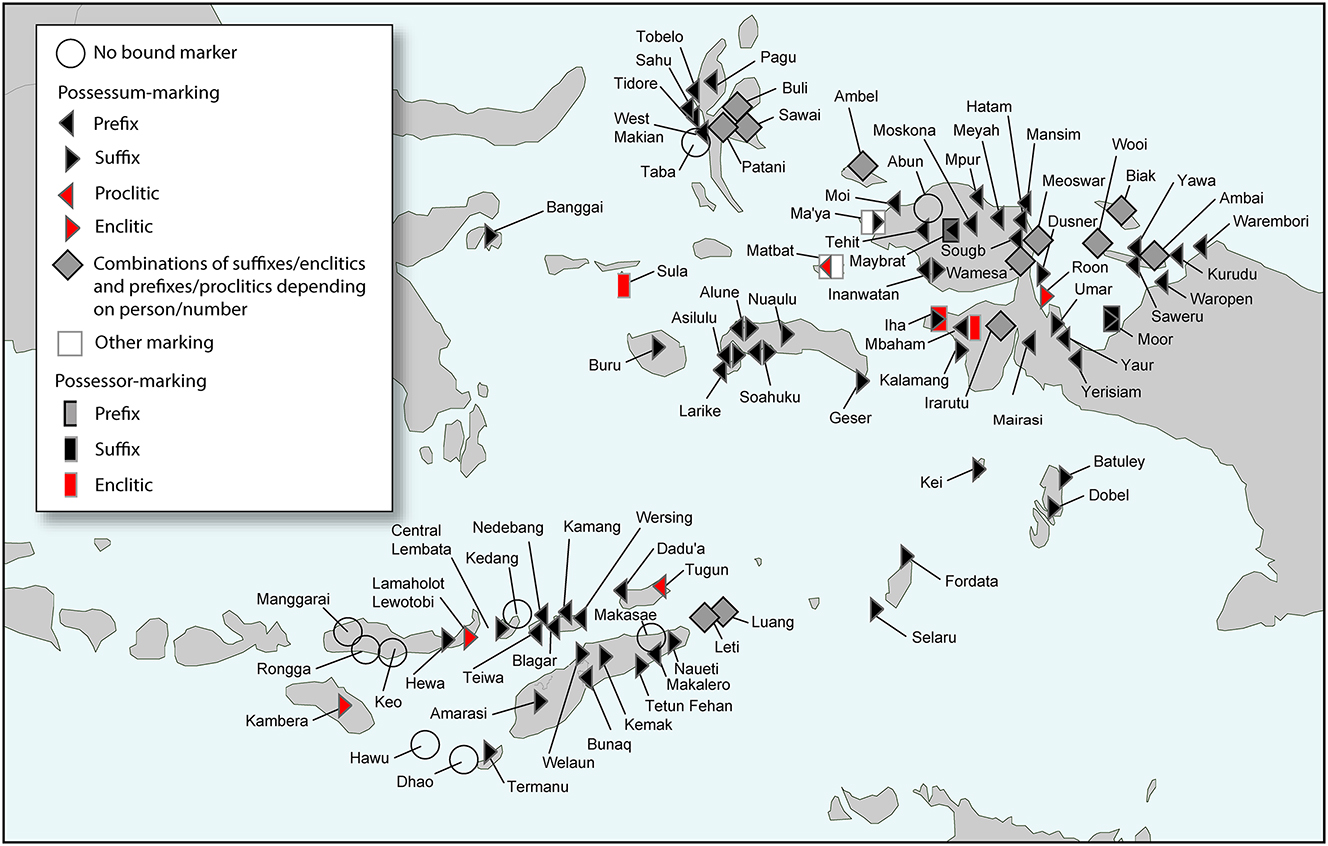

Map 4 gives an overview of the distribution of bound possessive markers in Linguistic Wallacea.[6] With few exceptions, it is the norm in the area for the possessum, rather than the possessor, to host bound possessive markers. This is consistent with the pattern across the wider Island Southeast Asian and Melanesian areas (Schapper and McConvell forthcoming), but it is uncommon elsewhere in the world (Nichols and Bickel 2013a). Only a few languages on the periphery of the area have no bound possessive markers.

Locus of bound possessive markers in Linguistic Wallacea.

Section 3.1 discusses possessum-marking in Linguistic Wallacea, drawing attention to the robust division between Papuan languages, which typically use prefixal markers, and Austronesian languages, which most often use suffixal or enclitic markers. We highlight that deviations from this pattern can be understood as the result of patterns of morphologization. Section 3.2 looks at the small number of cases of possessor-marking found in Linguistic Wallacea.

3.1 Possessum-marking

While possessum-marking is the norm in Linguistic Wallacea, a major divide between Austronesian and Papuan languages is found with respect to where these markers attach to the possessum. In Papuan languages, bound possessive markers are overwhelmingly prefixal or proclitic. In Austronesian languages, bound possessive markers are typically suffixal or enclitic. In both Papuan and Austronesian languages, bound possessum-marking forms are inflectional, agreeing in person and often number with the possessor, typically in the inalienable possessor construction. Map 4 shows that this division is attested quite consistently across much of the region.

Exceptions to the Papuan prefixing pattern are found in Bomberai languages such as Kalamang (already illustrated in 4) and Iha (15). The aberrant suffixal pattern is not found in Iha’s closest relative, Mbaham (16). This seems to be because the Mbaham prefixes are innovative forms originating in personal pronouns marked with the genitive case marker -man (see Section 3.2), which then morphologized, i.e., tam- < *ta-man ‘2sg-gen’.

| Iha (Papuan, Greater West Bomberai, Mbaham-Iha) |

| naan -ko |

| older.sister-2sg |

| ‘your older sister’ |

| (Coenen 1953: 7) |

| Mbaham (Papuan, Greater West Bomberai, Mbaham-Iha) |

| tam- kamen |

| 2sg-hand |

| ‘your hand’ |

| (Cottet 2015: 76) |

The dominance of suffixal markers for possessors in the Austronesian languages is a continuation of the pattern from their ancestor, Proto-Malayo-Polynesian (PMP), whereby pronominal enclitics indexing the possessor, typically known as genitive pronouns or genitive enclitics in the Austronesianist literature, bind to the possessum. Across Linguistic Wallacea, reflexes of the PMP genitive clitics grammaticalized into inflectional suffixes for possessors in inalienable possessor constructions. Deviations from this pattern are largely a result of further grammaticalizations.

In two regions of southern Linguistic Wallacea, we find the emergence in Austronesian of prefixal or proclitic markers for possessors, either in addition to suffixes or in place of them, in two regions. The first is in the languages of Ambon and western Seram, where the majority pattern is for suffixes to be used for the possessor of an inalienable noun (17a) and prefixes to be used to encode the possessor of an alienable noun (17b).

| Alune (An, Central Maluku) | |||

| a. | Suffixal possessor – Inalienable | b. | Prefixal possessor – Alienable |

| ina -ku | auku- luma | ||

| mother-1sg.poss | 1sg.poss-house | ||

| ‘my mother’ | ‘my house’ | ||

| (Laidig 1993: 339) | |||

In a few languages nearby, possessive suffixes have been lost and possessors for all nouns are encoded with prefixes. Larike is an example of a language of this kind (18).

| Larike (An, Central Maluku) | |||

| a. | iridur- ina | b. | irir- luma |

| 2sg.poss-mother | 3pl.poss-house | ||

| ‘your mother’ | ‘their house’ | ||

| (Laidig 1993: 320) | |||

See Florey (2005) for a detailed account of the various processes of affixal decline and loss in Central Maluku possessive constructions.

The second region involves the languages of Southwest Maluku and eastern Timor. As can be seen in Table 1, these show a cline of movement away from possessive suffixes towards prefixes by way of preposed or proclitic possessive markers (Schapper and Zobel forthcoming). In Leti, possessive suffixes for 1st person plural clusivity specifications have collapsed together with 3rd person singular. They are now disambiguated by an additional proclitic possessive marker that is used alongside the possessive suffixes. Closely related Luang has extended the use of the proclitics to all persons, including making their use obligatory for person-number combinations where no ambiguity in the possessive suffixes exists. Tugun has moved further away still from possessive suffixes, with only one suffix -n ‘3sg’ used on a small number of originally inalienable nouns where they have a non-human possessor (Hinton 1991: 70–71). Otherwise, all nouns in Tugun have their possessor encoded with a preposed free possessive marker, some of which have proclitic or prefixal forms (Hinton 1991: 67–68). Dadu’a represents the logical end point of the loss of possessive suffixes and the move to prefixal possessive marking, with all nouns having their possessor encoded with a possessive prefix.

From possessive suffixes to possessive prefixes (adapted from Schapper and Zobel forthcoming).

| Leti | Luang | Tugun | Dadu’a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1sg | -ku | a= … -ʔu | au/u= | a- |

| 2sg | -mu | (o=) … -mu | o | o- |

| 3sg | -nV | (e=) … -ni | ni/ni-/-n | ni- |

| 1pl.incl | ita= … -nV | it=/ita= … –ni | ita/it= | ita- |

| 1pl.excl | ami= … -nV | a= … -mamni | ami/am= | ami-/am- |

| 2pl | -mi | mi= … -mi | mi | mi- |

| 3pl | ira= … -nV | ir= … -ni | hira/hi(r)= | sia-/si- |

In northern Linguistic Wallacea, very few Austronesian languages mark possessors by means of a suffix alone. Complex patterns of possessive affixes, many of which represent innovative forms rather than PMP reflexes, cross-cut areal and genetic subgroupings. Van den Berg (2009: 346–347) reconstructs only possessive suffixes for Proto-SHWNG, suggesting that what he calls the “bewildering variety of forms and positions” (p. 342) found in the present-day SHWNG languages emerged only after the diversification of the family with a multitude of independent, parallel innovations, many of which may be attributable to contact with Papuan prefixing-type languages.

Languages that retain the suffixing type are Moor, Umar (19a), and Maˈya (19b). Patani uses suffixes with optional proclitics. (See Rødvand, this volume, for discussion of Patani.) Sawai (19c) has been reported by some sources (Kamholz 2014: 131–132; van den Berg 2009: 332) to use a combination of prefixes and suffixes, and by others (Whisler 1996: 48; Whisler and Whisler 1995: 663) to only use suffixes; this may indicate dialectal variation. While the suffixing type is conservative, the affixes themselves vary: Those found in Raja Ampat and South Halmahera paradigms are retained from PMP, but the Moor and Umar forms are each independently innovated. In some Maˈya dialects, suffixation is accompanied by tone loss (Remijsen 2001: 155). Superscripts indicate tone.

| a. | Umar (An, SHWNG, Southwest Cenderawasih Bay) | |||||||

| du -vie | ||||||||

| head-1sg | ||||||||

| ‘my head’ | ||||||||

| (Kamholz 2011: 7) | ||||||||

| b. | Maˈya (An, SHWNG, Raja Ampat-South Halmahera) | |||||||

| kaˈut -u 3 k | ||||||||

| head-1sg | ||||||||

| ‘my head’ | ||||||||

| (Remijsen 2001: 115) | ||||||||

| c. | Sawai (An, SHWNG, South Halmahera) | |||||||

| béboko -g | ||||||||

| head-1sg | ||||||||

| ‘my head’ | ||||||||

| (Whisler 1996: 6) | ||||||||

The Biakic and Yapen languages, as well as Ambel, Buli, and neighboring, non-SHWNG Irarutu, have progressed to using a combination of prefixes and suffixes or enclitics. While the systems are quite similar, the forms themselves are again mostly non-cognate – this is another case of multiple parallel innovations. Table 2 gives singular and plural paradigms for Wamesa and Biak. In Wamesa, the enclitics used with first- and third-person singular possessors are actually determiners, and indicate (literal or metaphorical) distance rather than strictly possessor person. (See Gil, this volume, for further discussion.) Biak has distinct inalienable possessive paradigms for kin terms, paired body parts, and non-paired body parts; the one given here is for non-paired body parts. The non-singular prefixes are identical, or nearly so, to the subject-marking prefixes that appear on verbs (see Section 5.1), and mostly non-cognate between branches.

Wamesa and Biak (An, SHWNG; Gasser fieldnotes; van den Heuvel 2006: 238).

| Wamesa (Yapen) | Biak (Biakic) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| sane ‘stomach’ | vru ‘head’ | |||

| sg | pl | sg | pl | |

| 1incl | ta-sane-mi | ko-vru-s-na | ||

| 1excl | sane=ne-i | ama-sane-mi | vru-ri | nko-vru-s-na |

| 2 | sane-mu(i) | me-sane-mi | vru-m-ri | mko-vru-m-s-na |

| 3 | sane=pa-i | se-sane-mi (hum); si-sane-mi (nhum) | vru-ri | si-vru-s-na |

Ambel uses a combination of a suffix and high-tone suprafix with singular possessors, and person/number-marking prefixes combined with a possessive suffix –n with non-singular possessors (3rd person inanimate possessors are indexed by a prefix i- and no suffix, regardless of number). Ambel has several subtly different direct possessive paradigms, one of which is given in Table 3 for the root yói ‘heart’. Diacritics represent tone.

Ambel (An, SHWNG, Raja Ampat-South Halmahera) direct possession with yói ‘heart’ (Arnold 2018: 304).

| sg | du | pc | pl | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1incl | tu- yoi -n | (a)tú- yoi -n | t- yoi -n | |

| 1excl | yói -k\H | um- yoi -n | atúm- yoi -n | ám- yoi -n |

| 2 | yói -m\H | mum- yoi -n | matúm- yoi -n | mim- yoi -n |

| 3an | yoi | u- yoi -n | atú- yoi -n | yoi -n |

| 3inan | i-yoi | i-yoi | i-yoi | i-yoi |

The SHWNG languages of southern and eastern Cenderawasih Bay (except Moor), Kurudu, Yaur, Yerisiam (20a), Waropen (20b), and Warembori (20c), have all lost their suffixes and only use prefixes to mark possession. Given their position, it is unlikely that any of these can be traced back to the PMP possessive enclitics; many are transparently repurposed verbal subject markers. Yaur and Yerisiam are closely related, and their nearest relative, Umar, is strictly suffixing. The other prefixing languages belong to an additional three primary subgroups of SHWNG.

| a. | Yerisiam (An, SHWNG, Southwest Cenderawasih Bay) |

| ne- baki | |

| 1sg-arm | |

| ‘my arm’ | |

| (Kamholz 2011: 6) | |

| b. | Waropen (An, SHWNG) |

| ra- worai | |

| 1sg-head | |

| ‘my head’ | |

| (Held 1942: 48) | |

| c. | Warembori (An, SHWNG) |

| e- rimun | |

| 1sg-head | |

| ‘my head’ | |

| (Donohue 1999: 40) |

Finally, the Raja Ampat language Matbat has dispensed with prefixes and suffixes altogether and relies on a combination of infixes, vowel alternations, and tonal changes on the possessum, which index the person and number of the possessor (with extensive syncretism). The infix appears after the penultimate vowel of the root, or after the single vowel of monosyllabic roots. Only the 1pl.incl form is considered to be a retention, reflecting what used to be a possessive suffix. Table 4 gives paradigms for two Matbat inalienable roots. Superscript numerals represent tone. The inflections shown here appear along with proclitics indexing the possessor, as in (21).

Matbat (An, SHWNG, Raja Ampat-South Halmahera) inalienable possession (Remijsen 2010: 290).

| sabo 21 m ‘back’ | fa 21 ‘husband | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| sg | pl | sg | pl | |

| 1incl | si 3 <n> bo 21 m | fa 3 -n | ||

| 1excl | si 3 <ŋ> bo 21 m | si 3 <m> bo 21 m | fa 3 -ŋ | fa 3 -m |

| 2 | si 3 <m> bo 21 m | si 3 <m> bo 21 m | fa 3 -m | fa 3 -m |

| 3 | sabo 21 m | sabo 21 m | fa 21 | fa 21 |

| Am-lu 12 | ak= nɔ 3 -ŋ | nun-wa 3 y | faya 1 w | yi 1 n. |

| 1pl.excl-two:clf | 1sg=brother-1sg.Psr | clf-small | hunt | fish |

| ‘Me and my younger brother are hunting fish.’ | ||||

| (Remijsen 2010: 288) | ||||

The diversity of forms within SHWNG is unique in Linguistic Wallacea, where most language groups show more internal consistency and developments can be accounted for by discrete innovations in a single branch. In SHWNG, parallel innovations, including the loss of possessive suffixes and the development of possessive prefixes, often by repurposing verbal agreement morphology, occurred independently multiple times throughout the tree, leading to disparate structures in even closely related languages. While contact with and shift from Papuan languages may well provide a partial explanation, the full story is necessarily more complex, and begs further research.

3.2 Possessor-marking

Only five languages that we know of in Linguistic Wallacea have constructions in which the possessor is the locus of possessive marking. In these, it is never the only possessive construction in a language but rather always exists alongside possessum-marking constructions.

Most commonly, the possessor-marking construction is required in certain contexts. We saw already in (10b) that Maybrat makes use of possessor-marking for postposed alienable possessors, but that the inalienable construction is possessum-marking. Iha (22a) has a possessor-marking enclitic and Mbaham (22b) a possessor-marking suffix that are used when the possessor is encoded by a full noun (as opposed to possessum-marking person inflections seen in (15) and (16) above). The Iha and Mbaham markers are described as genitive case markers and each is part of a larger system of case markers.

| a. | Iha (Papuan, Greater West Bomberai, Mbaham-Iha) | ||

| wumbi=ma | wund | |

| bird.of.paradise=poss | egg |

| ‘bird of paradise’s egg’ | ||

| (Coenen 1953: 7) | ||

| b. | Mbaham (Papuan, Greater West Bomberai, Mbaham-Iha) | |

| sorók-man | un | |

| cassowary-poss | egg | |

| ‘cassowary’s egg’ | ||

| (Cottet 2015: 81) | ||

In Sula, whilst 1st and 2nd person possessors are encoded by means of a free pronoun preposed to the possessum noun (23a), a 3rd person possessor, be it nominal or pronominal, must be marked by an enclitic =in (23b). This enclitic likely originates in the PMP genitive case marker *ni.

| Sula (An, Central Maluku) | ||||||||||||

| a. | No marking – 1st and 2nd person possessor | |||||||||||

| ak | pip | |||||||||||

| 1sg | money | |||||||||||

| ‘my money’ | ||||||||||||

| b. | Possessor-marking – 3rd person possessor | |||||||||||

| kiʔi=in | pip | |||||||||||

| 3sg=poss | money | |||||||||||

| ‘his/her money’ | ||||||||||||

| (Bloyd 2020: 285‒286) | ||||||||||||

Moor, an Austronesian language of southern Cenderawasih Bay, has a unique form of split possession marking that coincides – as in Maybrat – with possessor posing. The most frequent possessive construction involves a preposed possessor and a suffix -ío on the possessum signaling the possessive relationship (24a). A second, less common structure has a postposed possessor marked with the suffix -ìjo and an obligatory article on the possessum (24b).

| Moor (An, SHWNG) | ||||||||||||

| a. | Possessum-marking – preposed construction | |||||||||||

| kamuka | gwoʔ-ío | |||||||||||

| friend | canoe-3sg | |||||||||||

| ‘friend’s canoe’ | ||||||||||||

| b. | Possessor-marking | |||||||||||

| gwoʔ-o | kamuka-ìjo | |||||||||||

| canoe-art | friend-3sg | |||||||||||

| ‘friend’s canoe’ | ||||||||||||

| (David Kamholz p.c., in Schapper and McConvell) | ||||||||||||

4 Possessive classification and alienability

Almost all Wallacean languages are described as employing different morphosyntactic constructions to express possession of different nouns. Most linguistic descriptions talk about such splits in semantic terms of “(in)alienability”, referring to the perceived closeness of the relationship between possessum and possessor. Nichols and Bickel (2013b) prefer the term “possessive classification”, because, in most languages, the different possessive constructions are not (or no longer) semantic or grammatical categories but rather represent purely lexical classification of nouns. This is also true of the vast majority of languages with possessive classification in Linguistic Wallacea.

Possessive classification is widespread but not ubiquitous in Papuan languages. As can be seen in Map 5, possessive classification is often lacking in Papuan languages of the central highlands of New Guinea and in those along the north coastal region. However, possessive classification is much more often present in Papuan languages than it is absent, and is found in most Papuan families extending the full length of the Papuan area. For languages of the Austronesian family to the west and north of Linguistic Wallacea, possessive classification is not the norm, though some pockets are found in Borneo (Schapper and McConvell forthcoming). Only in the area around New Guinea are Austronesian languages with possessive classification systems found with any frequency. Papuan contact is widely acknowledged to be the ultimate source of possessive classification in Austronesian languages in these areas (see e.g., Donohue 2007; Klamer et al. 2008: 116–122).

Possessive classification in Melanesia (Nichols and Bickel 2013b).

As Nichols (1988) and Karvovskaya (2018) point out, discussions of “alienable” and “inalienable” possession often conflate distinct morphosyntactic types of possessive constructions. Following Schapper and McConvell (forthcoming), we separate out three primary types of possessive classification that distinguish classes of inalienable and alienable nouns in Linguistic Wallacea: (i) possessive classification encoded with a direct/indirect contrast; (ii) possessive classification where the same inflectional paradigm is used for both alienable and inalienable nouns, but with differences in the obligatoriness of the expression of a possessor, and (iii) possessive classification marked by free possessive linkers. A fourth, somewhat different type of possessive classification occurs in the domain of nouns belonging to the alienable class and involves an edible/general possessive contrast.

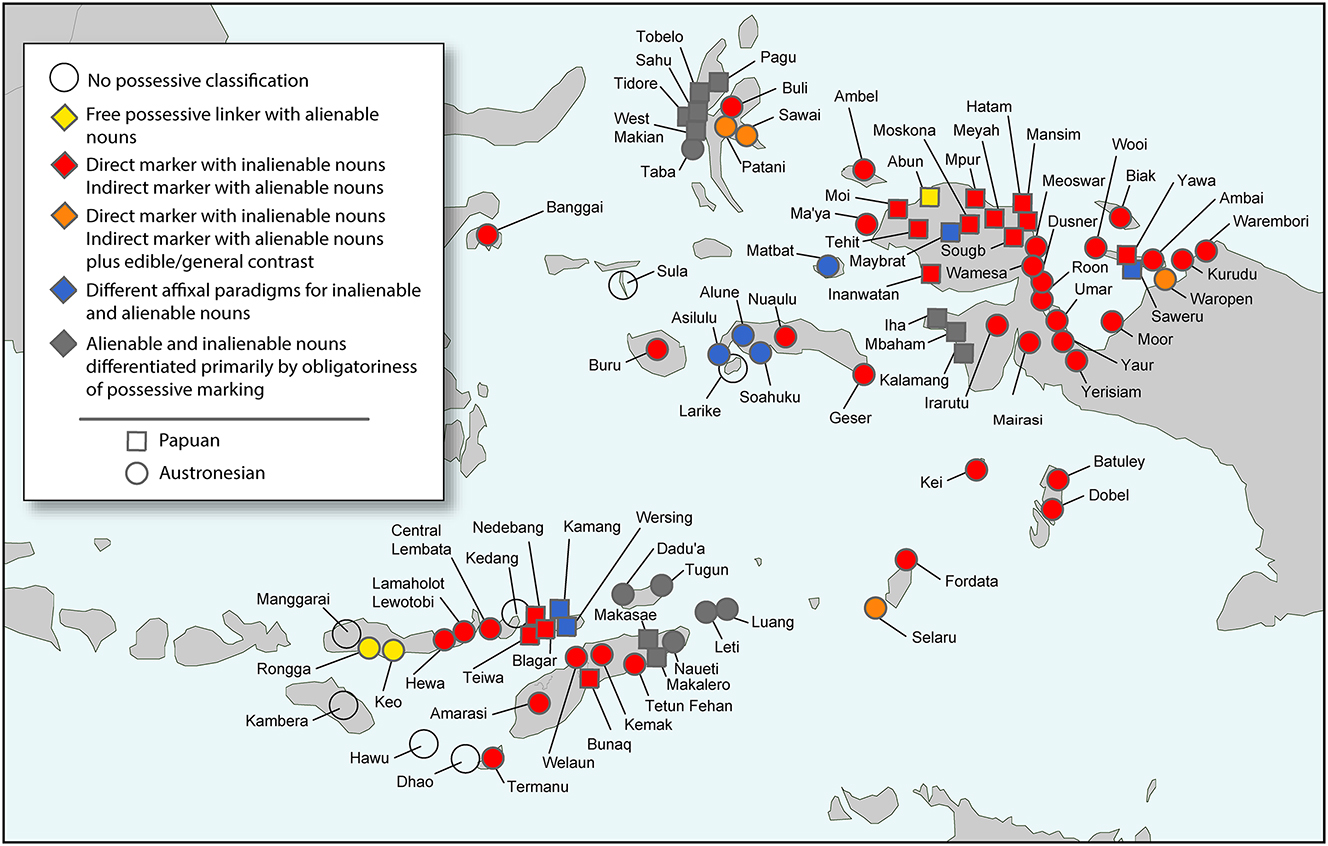

Map 6 presents an overview of the distribution of different types of possessive classification in Linguistic Wallacea. Possessive classification is absent in a variety of languages, mostly at the fringes of the area, the languages of Sumba-Hawu subgroup, in western Flores and parts of eastern Flores and eastern Timor and Sula. We see that the dominant pattern across Linguistic Wallacea is for alienable and inalienable nouns to be distinguished through a direct/indirect possessive contrast. Languages that use different affixes to distinguish alienable and inalienable nouns typically represent morphological developments on earlier direct/indirect systems. Possessive classification without inflectional difference and encoded by means of obligatory possessive markers on a subset of nouns is not uncommon. It is found dispersed through Linguistic Wallacea, but with particular concentrations in Halmahera and around eastern Timor. Languages with obligatory possession usually have lost either their direct or indirect possessive markers but have sought to maintain some form of possessive classification by having a class of nouns obligatorily possessed. Free possessive linkers and the edible/general contrast for alienable nouns are found scattered in a handful of languages throughout Linguistic Wallacea.

Possessive classification in Linguistic Wallacea.

We discuss the different types and their development, where known, in the following sections. Section 4.1 describes the classification of nouns into alienable and inalienable categories, and the flexibility of that categorization. Section 4.2 examines the direct versus indirect system of possessive classification that dominates Linguistic Wallacea. Classification marked by obligatory possession of a set of nouns is discussed in Section 4.3. Section 4.4 gives an overview of the use of free possessive linkers, and Section 4.5 discusses the edibility contrast found in a handful of possessive systems, particularly in the north-eastern part of Linguistic Wallacea.

4.1 Lexicalization and the semantics of inalienability

The range of nouns that are classified inalienable varies from language to language. Nouns denoting body parts are the most typical members of the inalienable class, though frequently not all members of the semantic field will be included. In Wooi, for example, most body parts and products are inalienable, but huhu ‘breast’ and rerawa ‘skin’ are alienable (Sawaki 2017: 140). Kin terms are classified as inalienable in many languages, but in Papuan families of the area in particular it is frequently observed that only a small number of kin terms belong to the inalienable class. For example, in Bunaq, less than a third of kin terms are inalienable (Schapper 2022: 246–247), while in Yawa only ‘mother’ and ‘father’ are inalienable (Jones 1993). Kin terms are also particularly prone to irregular marking or suppletion in their possessive paradigms (Baerman 2014; Schapper and McConvell forthcoming). Many languages additionally treat associative nouns (e.g., ‘voice’, ‘name’, ‘breath’, ‘shadow’, ‘feeling’, ‘friend’), locational nouns (e.g., ‘top’, ‘side’), and parts of wholes (e.g., ‘edge’, ‘fruit’) as inalienable. In some languages, nouns for culturally important items, such as ‘brideprice’, ‘canoe’, and ‘netbag’ are also inalienable, though these are far more variable from language to language.

Lexical classes of inalienable nouns, while generally strict as to their membership, can nonetheless allow some leeway in the possessive marking of some nouns. In our experience, however, the flexibility is usually very limited and does not take away from the basically lexicalized nature of the possessive classification system. (See Grimes’ 1991 description of Buru possession as a fluid possessive classification system for a possible counter-example.) In some languages, a small set of nouns may be used with either alienable or inalienable constructions depending on the semantics of the possessive relationship. For example, in Ambel (Arnold 2018: 320–321), some body, plant, and animal parts appear in inalienable constructions when they are a part of the possessor (e.g., “my bone, which is part of my body”) and in inalienable constructions when the relationship is one of ownership (“my bone, which comes from a pig and which I have in my house”). In some cases, the choice of construction affects the interpretation of the meaning of the possessed noun, for example making the difference between ‘voice’ and ‘story’. (See also Section 4.5 for flexibility with regards to edible possession.)

Elsewhere, categorial leeway may be due to language shift. For example, only a limited set of nouns may be inalienably possessed in Wamesa as it is currently spoken, but any noun, even classic inalienables such as close kin terms and basic body parts, may appear in an alienable construction with no change in meaning (25), and occasionally alienable and inalienable constructions are combined, suggesting lexicalization of the inalienable form and bleaching of its possessive meaning for some speakers. This flexibility is not attested in earlier sources (Saggers 1979; van den Berg 2009), and appears to be a result of declining language use. Florey (2005) describes a similar grammatical restructuring accompanying language shift in the Austronesian languages of Seram in central Maluku.

| Wamesa (An, SHWNG, Yapen) | ||||

| a. | Inalienable construction | b. | Alienable construction | |

| ama-ni | se-ne | ama=pa-sia | ||

| uncle-3sg.poss.inal.kin | 3pl.hum-poss.al | uncle=det-3pl.hum | ||

| ‘his/her uncle’ | ‘their uncles’ | |||

| (Gasser fieldwork) | ||||

A handful of languages have “double” possessive marking strategies that allow morphologically bound, inalienable nouns to occur with a free possessive marker normally used with alienable nouns in contexts where the possessum has been “alienated” from its possessor. An example of this from Blagar is presented in (26). A similar structure is described for the related Papuan language Bunaq (Schapper 2022: 352–354).

| Blagar (Papuan, Greater West Bomberai, TAP) | |||||||

| Na | ipar | nehe | ne | n-oŋ | met=ma | hava=taŋ | mea. |

| 1sg.sbj | dream | people | 1sg.poss | 1sg-head | taken=move | house=on | put |

| ‘I dreamed that people put my head on the house.’ | |||||||

| (Steinhauer 2014: 184) | |||||||

Such cases underline that in many languages, boundness is a strict morphological property of the lexical class of inalienable nouns, irrespective of semantics (cf. the languages of Cenderawasih Bay where this strictness does not exist, Section 4.2.2).

4.2 Direct versus indirect possession

The most widespread pattern for encoding alienability distinctions in both the Papuan and Austronesian languages of Linguistic Wallacea involves contrastive direct/indirect possessive constructions: Inalienably possessed nouns have their possessors marked “directly”, with the person and number of the possessor affixed on the noun expressing the possessum, while alienably possessed nouns have “indirect” possessors indicated by free possessive markers (pronouns, verbs, or particles), often inflected for the person and number of the possessor. An example of the direct/indirect possessive contrast is given for a Papuan and an Austronesian language in (27) and (28), respectively.

| Inanwatan (Papuan, unclassified) | |||||

| a. | Direct ‒ inalienable noun | b. | Indirect ‒ alienable noun | ||

| ná- wiri | órewo | agá | aiba-séro | ||

| 1sg-belly | woman | poss | voice-word | ||

| ‘my belly’ | ‘instructions of the woman’ | ||||

| (de Vries 2004: 30, 64) | |||||

| Ambel (An, SHWNG, Raja Ampat-South Halmahera) | ||||||

| a. | Direct ‒ inalienable noun | b. | Indirect ‒ alienable noun | |||

| tu- su -n | ne | ta-ni-n | wán | pa | ||

| 1du.incl-nose-nsg | art | 1pl.incl-poss-nsg | canoe | art | ||

| ‘our noses’ | ‘our canoe’ | |||||

| (Arnold 2018: 299, 302, p.c.) | ||||||

Cross-linguistically, contrastive direct/indirect possessive constructions to encode inalienability are rare. They are concentrated in two main clusters: Wallacea and Oceania on the one hand, and South and Central America as well the southern part of North America on the other hand (Bugaeva et al. 2021). The concentration of languages with the contrast within Linguistic Wallacea points strongly to it being an areal feature.

Early claims of a genetic explanation for the wide presence of direct/indirect possessive contrast in eastern Austronesian languages cannot be sustained. The absence of the distinction or even its remnants in the Austronesian languages of south-western Linguistic Wallacea and its presence in at least one genetically “Western” language, Banggai (Schapper and McConvell forthcoming) undermine Blust’s (1993: 259) reconstruction of the feature to his Central-Eastern Malayo-Polynesian subgroup of Austronesian. Donohue and Grimes (2008: 142) further show that the diversity of forms by which the contrast is marked in the Austronesian languages of southern Linguistic Wallacea, the putative CMP languages, points to erratic diffusion, rather than inheritance. This point is later conceded in Blust (2009). In the north of Linguistic Wallacea, however, it is widely agreed that the direct/indirect possessive contrast entered the Austronesian languages at an early stage. Van den Berg (2009: 353–354) argues that it was already present in Proto-Eastern Malayo-Polynesian (EMP), the hypothetical ancestor of Proto-SHWNG and Proto-Oceanic spoken in western New Guinea.

The geographic area in which the direct/indirect possessive contrast first appears in Austronesian languages is almost exactly the same area in which Papuan languages displaying similar systems are found. This strongly suggests that the emergence of the direct/indirect possessive contrast in the Austronesian languages was a response to regional norms within Linguistic Wallacea. Donohue and Schapper (2008) point out that the contrast between direct possession for inalienable nouns and indirect possession for alienable nouns can be reconstructed to Proto-Timor-Alor-Pantar and that the presence of such a feature at an early time in a Papuan family in the vicinity of where Austronesian languages first begin to display such typologically unusual systems is hardly likely to be chance. Donohue and Schapper trace the origin of direct/indirect possessive contrasts in Austronesian to Papuan influence, arguing that it arose through calquing Papuan constructions alongside more general pressure from Papuan languages to use preposed possessors (discussed in Section 2). Van den Berg (2009) agrees that Papuan contact was likely responsible for the direct/indirect possessive contrast entering Proto-EMP.

A final point to emphasize is that the direct/indirect contrast crosses genetic lines amongst the Papuan languages in Linguistic Wallacea, and includes members of the East, West, and South Bird’s Head, TAP, Mairasic, and Yawa-Saweru families as well as Papuan isolates such as Mpur. The cross-family presence of this geographically-limited feature supports arguments that Linguistic Wallacea is an ancient linguistic area whose formation predates the Austronesian dispersal (Donohue 2004a; Schapper 2010, 2015). This means also that the direct/indirect possessive contrast in the Austronesian languages of Linguistic Wallacea should be traced back not to a single Papuan source but to several.

Subtopics relevant to the direct/indirect possessive classification are discussed in the following sections. Section 4.2.1 looks at historical changes to direct/indirect systems that give rise to different affixal paradigms marking alienable and inalienable nouns. Section 4.2.2 discusses three types of zero-marked possessive constructions.

4.2.1 Developments on the direct and indirect contrast

The direct/indirect possessive contrast that was present at earlier stages in the history of many Papuan and Austronesian languages in Linguistic Wallacea has, through processes of morphologization, frequently developed into possessive classification systems marked by different sets of bound inflections on alienable and inalienable nouns.

Schapper (this volume) shows that many languages of Alor and some languages in eastern Pantar no longer have the original Timor-Alor-Pantar direct/indirect possessive contrast due to the inflections of the indirect possessive classifier becoming prefixes. The direct/indirect contrast is maintained in many languages of the family (see Schapper this volume), including Bunaq (29). The result is that instead of having different bound versus free possessive markers, different sets of inflectional prefixes are used to mark the possessor of inalienable and alienable nouns. This is illustrated in (30) on the basis of Kamang, a language of Central Alor.

| Bunaq (Papuan, Greater West Bomberai, TAP) | ||||

| a. | Inalienably (directly) possessed | b. | Alienably (indirectly) possessed | |

| g-up | gie | deu | ||

| 3-tongue | 3.poss | house | ||

| ‘his/her/their tongue’ | ‘his/her/their house’ | |||

| (Schapper fieldnotes) | ||||

| Kamang (Papuan, Greater West Bomberai, TAP) | |||||

| a. | Possession of inalienable noun | b. | Possession of alienable noun | ||

| na- lpaŋ | ne- kadii | ||||

| 1sg.poss-nose | 1sg.poss-house | ||||

| ‘my nose’ | ‘my house’ | ||||

| (Schapper fieldnotes) |

The same development can be observed in Saweru. While its sister language Yawa has a direct/indirect possessive contrast (illustrated in 34), both alienable and inalienable possessive classes in Saweru are marked by prefixes of different shapes, as seen in (31).

| Saweru (Papuan, Yawa-Saweru) | |||

| a. | Possession of inalienable noun | b. | Possession of alienable noun |

| ìsa- táni | imàma- tía | ||

| 1du-body | 1du-knife | ||

| ‘our (dual) bodies’ | ‘our (dual) knives’ | ||

| (Donohue 2004b: 4) | |||

Among the Austronesian languages of Linguistic Wallacea, affixes marking the possessor for both alienable and inalienable nouns are concentrated in Central Maluku languages spoken on Ambon Island and in the western parts of Seram. The pattern here is for suffixes to mark possessors on inalienable nouns and prefixes to mark possessors on alienable ones. This is illustrated with Alune in (32). As with the Papuan languages described in this section, these Austronesian languages have seen their preposed indirect possessive markers become prefixal inflections occurring on the possessum.

| Alune (An, Central Maluku) | |||

| a. | Suffixal possessor – Inalienable | b. | Prefixal possessor – Alienable |

| ina -ku | auku- luma | ||

| mother-1sg.poss | 1sg.poss-house | ||

| ‘my mother’ | ‘my house’ | ||

| (Laidig 1993: 339) | |||

Related languages of the Central Maluku subgroup spoken in central Seram maintain indirect possessors for alienable nouns (e.g., Nuaulu “indirect” we topi ‘my hat’ vs. “direct” ana -ku ‘my child’, Bolton 1990: 54–55).

4.2.2 Zero-marked constructions

Often when directly or inalienably possessed nouns are discussed, they are described as being unable to occur without the mention of a possessor. This is true of most languages, particularly in southern Linguistic Wallacea and Raja Ampat. For example, speakers of Ujir in the Aru Islands or Bunaq in central Timor always give directly possessed nouns with an inflectional prefix of one form or another; they are unable to isolate a nominal root for such “bound nouns” (as Bickel and Nichols 2013 refer to them).

Zero-marked possession, where no overt marking is used in a possessive construction, is relatively rarely attested cross-linguistically (Nichols and Bickel 2013a), but a number of examples appear in Linguistic Wallacea. These can be grouped into three types: incidentally unpossessed inalienables, juxtapositional possessive constructions, and zero-marked possession arising from differential animacy marking.

The first type comprises cases where an inalienable noun happens to appear outside of a possessive construction and with no expressed possessor, though this may be dispreferred in the language. This type is illustrated here by Wamesa. Examples (33a) and (33b) show a Wamesa kin term, tapu ‘grandparent, grandchild’, and body part, vara ‘hand/arm’, respectively, with no possessive marking, though the possessors are fully recoverable from context. Both of these are normally inalienable in the language. (See also Rødvand this volume for examples from Patani.)

| Wamesa (An, SHWNG, Yapen) | ||||||||

| a. | Tapu | sem-be-toru. | ||||||

| grandparent/child | 3pl.hum-ess-three | |||||||

| ‘The grandchildren number three; there are three grandchildren.’ | ||||||||

| b. | R<i>ute | nai | na | vara | rawa | sara. | Gelase | nai |

| <3sg>hold | be.at | loc | hand | side | left | glass | be.at |

| nana | vara | vata. | ||||||

| loc | hand | good | ||||||

| ‘She holds [the bottle] in (her) left hand. The glass is in (her) right hand.’ (Gasser fieldnotes) | ||||||||

Examples such as those in (33) underscore the fact that for some languages, the status of a noun as inalienable is decoupled from whether it must appear in a possessive construction. (See also Section 4.3 for more on the interplay of alienability and the optionality of possessive expression.) In most languages of Linguistic Wallacea, inalienable roots cannot appear on their own; a possessor is obligatorily expressed. In languages like Wamesa, and several of its relatives in northwest New Guinea and Halmahera, however, this is not the case, and inalienables may surface (syntactically and morphologically, if not semantically) unpossessed.

A second type of zero-marked possession, found in northwest New Guinea, denotes a separate type of inalienable construction. While in the previous examples nouns that normally appear possessed can exceptionally appear outside of a possessive construction, here the possessive construction is formed by simply juxtaposing the possessor and possessum NPs, with no possessive morphology. In Wamesa, zero-marked juxtapositional constructions are primarily used for part/whole relationships, especially with nouns such as ‘top’, ‘bottom’, ‘inside’, etc. as in (34a), though it is also, though less commonly, attested with other closely associated items such as eggs, nests, and occasionally body parts[7] (34b–c).

| Wamesa (An, SHWNG, Yapen) | ||||

| a. | [anio] Psr | [raro=wa] Psm | ||

| house | inside=det.dist | |||

| ‘inside of the house’ | ||||

| b. | [wonggei=wa-i] Psr | [ponori=pa-si] Psm | ||

| cassowary=det.dist-sg | egg=det-pl | |||

| ‘the cassowary’s eggs’ | ||||

| c. | [kerakera=pa | pau] Psr | [varakiai=pa | pau] Psm |

| spider=det | many | finger=det | many | |

| ‘the many spiders’ many legs’ (Gasser fieldnotes) | ||||

The possibility of intervening determiners and modifiers as in (34b–c) rules out the analysis of these constructions as compounds in Wamesa.[8] Furthermore, compounds are left-headed in the language, and thus would require the order of the nouns to be reversed to maintain a compatible meaning. Very similar constructions, usually involving part/whole or locational relations like those in (34a) are also described for Biak, Ambai, Wooi, and possibly Patani and Irarutu, though they are not all analysed as possessive in the literature (Jackson 2014; Rødvand this volume: Section 4.2.3; Sawaki 2017: 144–145; Silzer 1983: 103–105; van den Heuvel 2006: 251–252). This type can be difficult to distinguish in the literature from cases where the 3sg possessive marker is null but part of a larger overt paradigm, as part/whole relationships in particular are often only documented with 3sg possessors.

These juxtapositional constructions are not limited to the Austronesian languages. In Abun (35), this construction is used for inalienable nouns.

| Abun (Papuan, isolate) | |||||

| [Ndar | sye | ne] Psr | [gwes | de-dari] Psm | fot. |

| dog | big | det | leg | side-back | broken |

| ‘The big dog’s back leg is broken.’ (Berry and Berry 1999: 77) | |||||

Outside of New Guinea, Florey (2005) describes juxtapositional possession as an emerging innovative construction in several Austronesian languages of Seram, including Alune and Soahuku. In these languages, the possessive affixes are increasingly being dropped in favor of a juxtapositional construction for both alienables and inalienables, particularly among younger speakers.

Differential animacy marking can result in a third distinct type of zero-marked possessive construction, found for example in Moskona and Bunaq. This type of zero-marked construction differs from those previously discussed in that it reflects the classification of the possessor rather than the possessum. Moskona has two inalienable constructions, depending on the type of possessor. If the possessor is human, it is indexed by a prefix on the possessed noun, as well as an optional possessive pronoun (36a). If the possessor is non-human, regardless of animacy, no overt possessive marking is used (36b). This is part of a larger pattern in the language: Moskona uses the same set of prefixes to mark possessors and verbal subjects (see also Section 5.1), and verbs likewise appear without an agreement prefix when their subject is non-human. Owoka ‘name’ is inalienable in Moskona.

| Moskona (Papuan, East Bird’s Head) | |||||

| a. | i- osnok | i - ebirorha | |||

| 3pl-person | 3pl-skull | ||||

| ‘people’s skulls’ | |||||

| b. | mes | owoka | Masur | dokun | Masik | |||||

| dog | name | sandfly | and | mosquito | ||||||

| ‘The dogs’ names were Sandfly and Mosquito.’ (Gravelle 2013: 95) | ||||||||||

4.3 Possessive classification without inflectional difference

Possessive classification without inflectional difference is where the possessive markers for the alienable and inalienable classes of nouns are the same. The difference between classes lies in that inalienable nouns must occur with a possessor expressed in some form, whereas alienable nouns can occur without any expression of a possessor. A typical statement linking the expression of a possessor with (in)alienability is found in Bowden’s (2001: 266–267) description of Taba, an Austronesian language of South Halmahera: “[a] differentiation between alienable and inalienable possessive categories is not obligatorily marked by the use of different forms in Taba, as is common in many closely related languages. However, some of what could perhaps be called the most ‘inalienable’ kinds of possessive relationships (e.g., expressions referring to part-whole relationships) are distinguished in Taba by obligatory possessive marking.”

While a difference in the obligatoriness of the grammatical possessive marker is the most typical form taken by this kind of possessive classification, it is not the only type. Members of the “second” inalienable class of nouns in the languages of Alor (discussed further below) obligatorily express a possessor in one of two ways. Either they must occur with a possessive inflection with the same form as used by an alienable noun, or in a possessive compound where the possessor is expressed with a preceding noun. These two constructions are illustrated on the basis of Wersing in (37).

| Wersing (Papuan, Greater West Bomberai, TAP) | ||||

| a. | e-kèlut | b. | bong kèlut | |

| 2sg-skin | tree skin | |||

| ‘your skin’ | ‘bark’ | |||

| (Schapper 2020c) | ||||

In the same vein, van Staden (2000: 125–126) describes some differences in the licensing of person-number prefixes and the reflexive prefix ma- as demarcating the difference between alienable and inalienable nouns in Tidore.

For many cross-linguistic definitions of possessive classification, differences in the obligatoriness of the expression of a possessor without inflectional difference such as described here would not be counted as a form of possessive classification. However, within Linguistic Wallacea, recognizing this obligatory/optional possessive contrast as a form of possessive classification is important for understanding how possessive classification systems change and adapt in the context of paradigm loss. In Linguistic Wallacea, languages with obligatory possession can be found in concentrations in North Halmahera and in the region around eastern Timor. In both regions, the obligatory/optional possessive contrast is shared across proximal Papuan and Austronesian languages, suggesting a role for contact.

Languages with an obligatory/optional possessor contrast are those where either direct or indirect possessive markers are synchronically absent, typically as the result of diachronic loss of one set or the other. In the case of Taba, the direct possessor affixes found in its near relatives have been lost. The modern Taba possessive marker ni is used obligatorily with inalienable nouns and optionally with alienable ones. It is a reflex of the indirect, general possessive classifier that has cognates in its relatives in South Halmahera (Bowden 2001: 233; see Section 4.5 on general possessive classifiers). Nearby in the Papuan languages of North Halmahera, comparison with their likely relatives on the West Bird’s Head suggests that the obligatory/optional possessive contrast has arisen through the loss of the direct possessive prefixes that are still found in West Bird’s Head languages. A similar situation is described by Schapper (this volume, Section 3) for the Timor-Alor-Pantar languages of eastern Timor. In these, the direct/indirect contrast has been lost due to the loss of reflexes of the Proto-TAP direct possessive prefixes. Instead, the original indirect possessive markers have expanded and are now used for nouns denoting both inalienable and alienable nouns, but while inalienable nouns are obligatorily possessed, alienable ones are only optionally so.

The loss of original indirect possessive markers appears to have occurred in other languages where the same set of affixes is used for both alienable and inalienable nouns, with the already described differences in obligatoriness in the appearance of the possessive affix. For instance, all nouns in Kalamang can take a possessive suffix, but one is obligatory on a small set of kin terms and a larger set of nouns used in part-whole relations (Visser 2020: 160–162). Although little is known about the morphological history of West Bomberai languages, it seems likely that these too originally had preposed indirect markers for possessors of alienable nouns ‒ reflected now as prefixal possessive morphology in Mbaham (see Section 3.1), but that these have been lost in Kalamang.

In some languages, however, it is not clear that a direct/indirect contrast was ever present. For example, there is no evidence that Leti or that its relatives in the Leti-Luang subgroup of southern Maluku ever had indirect possessive markers. Still, Leti displays the obligatory/optional form of possessive classification, in this case by means of a possessive suffix on the possessum noun. There are no nouns that cannot host a possessive suffix: Body parts and other nouns denoting typical inalienables are always inflected for a possessor (e.g., iran-nu nose-3sg.poss ‘his/her/its nose’; but *iran), whereas nouns denoting alienables such as vatu ‘stone’ are not required to, but can (e.g., vat-nu stone-3sg.poss ‘his/her/its stone’; vatu ‘stone’).

The repeated (re-)creation of possessive classification systems on the basis of an obligatory/optional contrast, both where paradigms of earlier indirect/direct systems were lost and where no earlier possessive classification system was known to have been in place, speaks to the significant areal pressure exerted on languages in Linguistic Wallacea to differentiate alienable from inalienable nouns. In fact, this pressure can also be observed in languages that still have (extensions of) earlier indirect/direct systems. In the languages of Alor, for example, we see the emergence of a third possessive class from what seems to be a new cycle of grammaticalization of possessive markers on nouns denoting “inalienables”. Illustrated in Schapper (this volume, Section 3), these languages have a small closed class of nouns which are obligatorily possessed like inalienable nouns, but their possessor is expressed with an alienable possessive prefix. This class exists alongside the set of inalienable nouns and the alienable nouns whose possessors are marked with different paradigms of possessive prefixes. Similarly, in Yawa, Jones (1993) describes the direct possessive construction on inalienable nouns denoting body parts and the kin terms ‘mother’ and ‘father’ (38a), while the indirect construction, using possessive pronouns, is considered alienable and applies to all other nouns (38b). However, possessive marking is obligatory with all kinship terms (outside of direct address), even those whose possessor is encoded indirectly (38c).

| Yawa (Papuan, Yawa-Saweru) | ||||||

| a. | Natanyer | apa-jaya | Ø-awabe-to | |||

| Natanyer | 3sg.m-father | 3sg.m-yawn-prf | ||||

| ‘Nathaniel’s father yawned.’ | ||||||

| (Jones 1986: 47) | ||||||

| b. | Nya | tame | mi | ruwim? | ||

| 2sg.poss | name | top | what | |||

| ‘What is your name?” (Jones 1991: 103) | ||||||

| c. | Ruwi | pi | nyo | a-wain-o | nya | ’nuja ? |

| who | top | 2sg | 3sg.obj-call-appl | 2sg.poss | older.sibling.same.sex | |

| ‘Who do you call “older brother”?’ (Jones 1991: 103) | ||||||

Such examples could be taken to suggest that splits of inalienable nouns into different inflectional classes, including potentially those described by Bach (2018: 177–195) and Arnold (this volume), might have arisen through different cycles of grammaticalization of possessive markers to form bound possessive classes with different nouns denoting inalienables at different times.

4.4 Free possessive linkers

A minor strategy for encoding alienability contrasts in Linguistic Wallacea involves a free uninflecting possessive linker between (pro)nouns expressing a possessor and a possessum. As is cross-linguistically common, the possessive linker only appears between a possessor and a possessum where the possessum noun is classified as alienable. These linkers are not inflectional and express no person/number information about the Psr or Psm. This strategy is only known from the Papuan language Abun and the Austronesian languages of the Central Flores subgroup.[9]

In Abun, the possessor of inalienable nouns is introduced without a marker of possessive relationship (39a), as in the juxtapositional zero-marked constructions already discussed in Section 4.2.2. With alienable nouns, the possessor is introduced with an invariant free possessive linker bi (39b).

| Abun (Papuan, isolate) | ||||||||||

| a. | No possessive linker | |||||||||

| Sepenyel | gwes | |||||||||

| Sepenyel | leg | |||||||||

| ‘Sepenyel’s leg’ | ||||||||||

| b. | Free possessive linker | ||||||||

| Rahel | bi | ai | bi | nyom | |||||

| Rachel | poss | father | poss | machete | |||||

| ‘Rachel’s father’s machete’ (Berry and Berry 1999: 79, 82) | |||||||||