Abstract

In Malayic languages, prefixes derived from Proto-Malayic *(mb)AR- are characterized by an unusual multifunctionality pattern. On the one hand, continuators of *(mb)AR- may encode functions that are typical of middle markers across languages. On the other hand, they are used as denominal verb formatives. The aim of this article is to provide a diachronic explanation for such an unusual combination of functions. The denominal verbalizing function of *(mb)AR- appears to be primary, and a diachronic scenario can be sketched through which a denominal verb formative has extended to cover a portion of the functional space cross-linguistically encoded by middle markers.

1 Introduction: the “middle” prefix in Malayic languages

The continuators of the verbal prefix reconstructed as *(mb)AR- [1] to Proto-Malayic (Adelaar 1984, 1992), the common ancestor of Malayic languages, have various functions in the daughter languages. These functions are partly co-extensive with the valency-reducing functions encoded by middle markers across languages (as described in the classical work by Klaiman (1991) and Kemmer (1993)). Moreover, some of the verbs carrying the prefixes in question fall within the verb classes that are typically marked as middles when a language has a non-oppositional middle, to be intended, following Inglese (2022; see also Inglese and Verstraete 2023), as a marker obligatory with some monovalent verbs that lack an active counterpart. Finally, one of the functions of the continuators of *(mb)AR- falls outside the middle domain proper: Across Malayic languages, continuators of *(mb)AR- are used to derive intransitive verbs with various meanings from entity-denoting (and in some cases also property-denoting) bases.

The multifunctionality of the continuators of this verbal prefix can be illustrated by Standard Malay. In Standard Malay, the prefix bər- (<Proto-Malayic *(mb)AR-) can combine with property-denoting bases, producing verbs meaning “to be or become (adjective), to act in such a way as to get the feeling or become (adjective)” (Adelaar 1984: 411; cf. 1a). This use can be qualified as anticausative, and is not limited to adjectival bases, as shown by (1b). Anticausative must be intended here as encompassing both decausative states of affairs (i.e. those in which there is a change of state of a non-agentive subject without the influence of an external agent), and autocausative states of affairs (i.e. those in which the subject has some control over the onset of the change of state; cf. Creissels 2006: 10). Such situations (called spontaneous events in Kemmer’s 1993 semantic map of middle voice) are consistently marked as middle in languages with an oppositional middle voice marker (i.e., a marker that derives intransitive verbs from transitive ones, as in Italian scioglier-si ‘melt’ (intr.) versus sciogliere ‘melt’ (tr.)). When added to transitive verbs, bər- produces intransitive verbs with possible nuances of reciprocity and/or antipassive,[2] two more functions that are often conveyed by oppositional middle markers across languages, cf. (1c). The prefix bər- is also compulsory with some intransitive verbs denoting, among other things, translational motion events and body posture (cf. 1d), two types of verbs that are often middle-marked in languages with non-oppositional middle markers. The prefix in question is also used as a denominal verb formative when added to nouns, producing verbs with the meaning ‘to have, contain, use, produce, wear, get n’, cf. (1e). This latter function of bər- does not belong to the set of typical functions of middle markers, which makes the distribution of this prefix rather unusual cross-linguistically:[3]

| Standard Malay |

| [Adelaar 1984: 411–413; D. M. Karaj, personal knowledge] |

| siap ‘ready’ > bərsiap ‘make preparations/get ready | (autocausative) |

| uban ‘grey hair’ > bəruban ‘turn grey’ | (decausative) |

| bantah ‘contradict (someone)’ > bərbantah ‘quarrel (with each other)’ | (reciprocal) |

| buru ‘hunt’ > bərburu ‘be hunting’ | (antipassive) |

| bərenaŋ ‘swim’ | (translational motion/body posture verbs) |

| bəraŋkat ‘depart, leave’ | |

| bərdiri ‘stand’ | |

| suami ‘husband’ > bərsuami ‘have a husband/be married’ | (denominal verb formative) |

| sepatu ‘shoe’ > bərsepatu ‘wear shoes’ | |

| telor ‘egg’ > bərtelor ‘lay an egg’ | |

In other Malayic languages, too, the continuators of *(mb)AR are used under similar conditions, displaying functions that fall both within (i and ii) and outside (iii) the array of situation types covered by middle markers cross-linguistically; in particular:

they cover typical functions of oppositional middles such as anticausative, reciprocal, and antipassive;

they mark predicates belonging to semantic classes usually marked by non-oppositional middle markers: body care/grooming, (non-)translational motion, body posture, etc.;

they are used as denominal verb formatives (when added to nouns).

In Minangkabau, for instance, ba-/bar- (<*(mb)AR-) covers two functions typically encoded by middle markers in languages with an oppositional middle, namely anticausative, cf. (2a), and reciprocal, cf. (2b). Moreover, the same prefix is said by Crouch (2009: 162) to be used with a reflexive function. At closer inspection, however, the ba-marked reflexive verbs she discusses fall within a restricted set of cognition predicates such as ‘think’, ‘be cogitating’, ‘meditate’, cf. (2c). This class is one of the semantic classes that are frequently middle-marked across languages, both by oppositional and non-oppositional middle markers (Kemmer 1993: 134–135).[4] Besides the middle functions, ba-/bar- produces intransitive verbs meaning ‘to have n’ when added to nouns (cf. 2d):

| Minangkabau | [Crouch 2009: 199, 166, 162–163] |

| ubah ‘change (tr.)’ > barubah ‘change (intr.)’ | (anticausative) |

| ma-ambuih ‘blow (on sth)’ > barambuih ‘blow (intr.)’ | |

| cakak ‘fight’ > bacakak ‘fight each other’ | (reciprocal) |

| pikia ‘think’ > bapikia ‘think to oneself’ | (cognition verbs) |

| ubuangan ‘connection’ > baubuangan ‘to have a connection’ | (denominal verb formative) |

| anak ‘child’ > baanak ‘to have a child’ | |

In Mualang, the continuator of Proto-Malayic *(mb)AR- is ba- (Tjia 2007: 44, 160–167). This prefix is described by Tjia (2007: 160–164) as an antipassive prefix: in clauses containing ba-marked predicates, the patient, though behaving syntactically in various ways, is never an argument, and the clause itself is intransitive and describes “the situation of an agent carrying out an activity” (Tjia 2007: 161). Ba- can be prefixed to verbs and nouns. With verbs, it depicts the agent subject as engaged in an activity in which the patient “is not an issue in the description of the situation, or […] is irrelevant” (Tjia 2007: 161; cf. (3a)). With some transitive bases, ba- also denotes reciprocal activities, cf. (3b). Similarly to what happens in other Malayic languages, some ba-marked verbs (with or without an unmarked counterpart) belong to specific classes that are frequently middle-marked across languages, among which translational motion, body posture and body care verbs (cf. 3c).[5] Ba- is also productively used with nouns, noun phrases, and nominal compounds, with the meaning ‘produce, possess, spend, have a relationship to n’ (cf. 3e), or, more generally, “that the actor-subject carries out an activity that is habitually or generally done on or associated with the noun base” (Tjia 2007: 164):

| Mualang | [Tjia 2007: 161–165] |

| ba-bunuh (<bunuh ‘kill’) ‘be engaged in X-killing’ | (antipassive) |

| ba-tunu (<tunu ‘burn’) ‘be engaged in X-burning’ | |

| ba-tim’ak (<tim’ak ‘shoot’) ‘be engaged in X-shooting’ | |

| sida’ | ba-temu | (reciprocal) |

| 3pl | ba-meet | |

| ‘They met each other.’ | ||

| ba-lepa (<lepa ‘rest’) ‘rest oneself’ | |

| (translational motion/body posture/body care verbs) | |

| ba-ren’am ‘soak oneself’ | |

| ba-diri, (<diri ‘stand’), ‘stand’ | |

| ba-pina ‘move, move oneself’ | |

| ba-telu’ (<telu’ ‘egg’), ‘produce eggs’ | (denominal verb formative) |

| ba-pala’ (<pala’ ‘head’) ‘have a head, be headed’ | |

| ba-malam (<malam ‘night’) ‘spend the night’ | |

| ba-uma (<uma ‘dry rice field’) ‘do cultivation in the field’ | |

In Iban, bǝ- (<*(mb)AR-) can be attached to either verbal or nominal bases (Omar 1969: 93); in the former case, it produces intransitive verbs with reciprocal (cf. 4a) and antipassive meanings (cf. 4b, where the object is demoted to an oblique position), while in the latter it carries the meaning of ‘possess/make/work with n’ (cf. 4c):

| Iban | [Omar 1969: 93] |

| tikiʔ ‘to visit’ > bǝtikiʔ ‘to visit one another’ | (reciprocal) |

| bǝ-munsoǝh | paŋan diri |

| bǝ-enemy | each other |

| ‘regard one another as enemies’ | |

| bǝ-bǝrap | ʔŋgaw | ʔija | (antipassive) |

| bǝ-embrace | with | 3sg | |

| ‘embraces her’ | |||

| isi ‘content’ > bǝʔisi/bisi ‘to have content or capacity’ | (denominal verb formative) |

| ʔaiʔ ‘water’ > bǝraiʔ ‘(be) watery’ | |

| umaj ‘rice field’ > bǝʔumaj ‘to have or to work in the rice field’ |

The aim of this article is to tease out the diachronic mechanisms that have produced the multifunctionality of the prefixes derived from Proto-Malayic *(mb)AR- in Malayic languages. To do so, we will consider the antecedents of this prefix starting from the immediate ancestor of Proto-Malayic, the Malayo-Sumbawan sub-group within Malayo-Polynesian languages,[6] up to Proto-Austronesian.

After discussing the patterns of multifunctionality of these prefixes in Malayic and its ancestors, we will propose that they are manifestations of a Proto-Malayo-Polynesian (and possibly late Proto-Austronesian) denominal verbalizer *ma-, which derived agent-oriented intransitive verbs from nouns and other bases, with an additional element *R- possibly of an aspectual nature. The likelihood of this diachronic scenario leading from a denominal verb formation strategy to the multifunctional markers in question will be weighed against the available cross-linguistic evidence concerning denominal verb formatives and the emergence of middle systems.

The article is organized as follows. In Section 2, we will trace the history of the prefix in question by looking at its antecedents in Malayo-Sumbawan languages, while in Section 3, we will discuss previous reconstructions of the form and meaning of the prefix, which should be possibly reconstructed to as early as Proto-Austronesian, by highlighting the elements shared by these reconstructions. Finally, in Section 4, we will sketch a diachronic scenario accounting for the emergence of the cross-linguistically unusual multifunctionality of the continuators of the prefix in question, and in Section 5, we draw some general conclusions.

2 Tracing the history of the prefix

The evidence provided by Malayo-Sumbawan languages, the larger group to which Malayic languages can be ascribed within Malayo-Polynesian, for the functions of the prefix in question is not conclusive. There are, however, reasons to assume that the reflexes of the Proto-Malayo-Polynesian (henceforth PMP) prefix *(m)AR- had in these languages more or less the same distribution of the reflexes of *(mb)AR- in the languages of the Malayic sub-group discussed in Section 1.

In Balinese, the prefix me-, as discussed by Clynes (1995: 186–187), marks (i) anticausative situations, e.g. spontaneous/uncontrolled movement, as in (5a); (ii) “stative verbs with the meaning ‘U[ndergoer] be in a state of having been verb-ed” (Clynes 1995: 260), as in (5b); (iii) and some verbs that do not have an active counterpart, denoting body action, natural body processes, and motion, as in (5c). The same prefix is also attached to nouns with verbalizing functions (cf. 5d):

| Balinese (Singaraja dialect) | [Clynes 1995: 264, 187] |

| me-kebyos ‘to spill over (of liquids)’ | (anticausative) |

| me-jagur ‘be in a state of having been punched’ | (passive/stative) |

| me-suah ‘to comb’ | (body action/natural body process/motion verbs) |

| me-kecuh ‘to spit’ | |

| me-tengkéém ‘to clear throat’ | |

| me-bangkes ‘to sneeze’ | |

| me-laib ‘to walk’ | |

| bo ‘odor’ > me-bo ‘have odor, smell’ | (denominal verb formative) |

| bulu ‘feather, fur’ > me-bulu ‘have feathers/fur/body hair’ | |

| adan ‘name’ > me-adan ‘have a name’ | |

In Sasak, the prefix ber- is described as an intransitivizer, deriving one-place predicates from two-place predicates by removing the patient (cf. 6a); when attached to nouns, it has possessive meaning (‘to have n’, cf. 6b):

| Sasak | [Austin 2001: 130, 2013: 54] |

| harus=m | iaq | ber-ajah | nani | (antipassive) |

| must=2 | proj | intr-study | now | |

| ‘You have to study now.’ | ||||

| elong ‘tail’ > ber-elong ‘have a tail’ | (denominal verb formative) |

| bulu ‘hair’ > be-bulu ‘be(ing) hairy (having hair)’ | |

The Sumbawa prefix ba(r)- is described as a detransitivizer yielding agentive intransitive verbs in which the object is not present (cf. 7a) and as a strategy to mark reciprocal situations (cf. 7b). It also carries the meaning of ‘to have’ in combination with nouns (cf. 7c).

| Sumbawa |

| [Jonker 1904: 274; Seken et al. 1990: 17, 25; Sumarsono et al. 1986: 19] |

| ba-sura-mo | datu | (antipassive) |

| ba-order-emph | prince | |

| ‘The prince ordered’ | ||

| bareto ‘to know each other’ | (reciprocal) |

| barotak ‘(be/being) smart’ (lit. ‘have/having brain’) |

| (denominal verb formative) |

The prefix meu- in Acehnese is functionally similar to Indonesian/Malay ber-, and according to Asyik (1987: 67) it is also etymologically cognate with it. As shown in (8), meu- marks reciprocal situations, cf. (8a), and is used with some verbs denoting body action (as in (8b)) and involuntary actions, cf. (8c). When prefixed onto nominals it carries the meanings of ‘to produce n’, ‘to call someone n’, ‘to use n’, ‘to have n’, etc. (cf. (8d)), (Asyik 1987: 67–71).

| Acehnese | [Asyik 1987: 68, 70–71, 81–82, 109] |

| poh ‘to beat’ > meupoh ‘to beat each other’ | (reciprocal) |

| meuʔeunthö (<eunthö ‘to rub’) ‘to rub oneself on sth’ |

| (body action verbs) |

| meutulak ‘to push s/o by accident’ | (involuntary action) |

| sira ‘salt’ > meusira ‘to make salt’ | (denominal verb formative) |

| bang ‘elder brother’ > meubang ‘to call someone elder brother’ | |

| meugeulitan angen ‘to ride a bicycle’ | |

| asap ‘smoke’ > meuasap ‘smoky’ (lit. ‘having smoke’) | |

| boh ‘fruit’ > muboh ‘having fruit’ | |

To sum up, the prefixes originating from Proto-Malayic *(mb)AR- and PMP *maR are readily recognizable from both their shape and their function. In all the languages discussed above, they have verbalizing functions when combined with nouns, deriving intransitive verbs from them. From among the possible meanings, in six out of eight languages discussed above (no evidence for Balinese and Sasak) the prefix in question marks reciprocal situations. Another common function of these prefixes is the marking of antipassive situations (i.e. situations in which the object is irrelevant/stereotypical/unindividuated). Other less common functions are the marking of spontaneous processes that imply a change of state (anticausative), the marking of involuntary actions, and the marking of stative situations with a passive overtone, as in Balinese. The multiplicity of the meanings of the prefix is summed up in Table 1.

The situation types conveyed by reflexes of *(mb)AR-/*maR- in Malayic and Malayo-Sumbawan languages.

| Group | Language | Verbalizer | Reciprocal | Antipassive | Anticausative | Passive/stative | Involuntary action | Specific verb classes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Malayic | Standard Malay bər- | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Minangkabau ba-/bar- | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Mualang ba- | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Iban bə- | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Malayo-Sumbawan | Balinese me- | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Sasak ber- | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Sumbawa ba- | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Acehnese meu- | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

The distribution in Table 1 shows that the verbalizing function of *(mb)AR-/*maR- is attested in all the languages discussed in this and the previous section. This fact confirms its primacy in diachronic terms, which is also postulated by previous reconstructions of the function of these prefixes (see Section 3). The question now arises through which mechanisms a verbalizer has become a marker of situation types falling within the functional domain of middle voice. Before discussing the diachronic scenario behind this development, however, it is necessary to discuss previous reconstructions of this prefix. It is to this task that we now turn.

3 Previous reconstructions

Adelaar (1984, 1992 reconstructs Proto-Malayic *(mb)AR- as a prefix

used to form intransitive verbs, […] which occurred at least with intransitive verbs and nouns. Used with nouns, it must have meant ‘possess, contain, wear, use, produce, get (noun)’, or, if the noun referred to a profession or a mutual relationship, ‘assume the quality of (noun)’ (Adelaar 1984: 418).

The prefix is not a Proto-Malayic (or Proto-Malayo-Sumbawan) innovation: There is evidence that it can be reconstructed to PMP and to Proto-Austronesian (PAn) as well. All the existing reconstructions of the PAn ancestor of this prefix are based on the assumption that *maR- can be decomposed into smaller formatives. Less clear, however, are the details of the original functions of these formatives.

According to Ross (2002: 49–50), PMP *maR- (derived from the combination of the PMP prefix *paR- ‘durative’ + actor voice *<um>, Ross 2002: 49–50) is a durative verbalizer in that it originally described “events regarded as ongoing or repetitive, as opposed to events regarded as punctual or viewed in their entirety” (Ross 2002: 49). As Ross cautiously warns, however, such a semantic label should be considered as “very tentative” (Ross 2002: 49).

According to Kaufman (2009) *maR- was a (late) PAn innovation involving a combination of *ma- (<*p<um>a- ‘causative + actor voice’) with a middle marker -R-, based on data from Formosan languages discussed in Zeitoun (2002), where *maR- displays reciprocal and anticausative functions (e.g. Southern Paiwan mar-‘a-tjeŋeLay, recp-pl-love, ‘love each other’; Nanwang Puyuma marə-kataguin, recp-spouse, ‘to get married’; Pazeh maxa-tulala, mid-blossom, ‘to blossom, to bloom’).[7]

Blust (2013: 376) reconstructs a ‘stative’ prefix *ma- to PAn. This prefix combines with other formatives yielding two prefixes that are the ancestors of Standard Malay meŋ- and ber- – *maŋ- and *maR- respectively. These two prefixes are glossed as ‘actor voice’ markers (Blust 2013: 378–379). Blust notes that *maR- marked one type of intransitive verb (the other type being marked by *-um-),[8] while the function of *maŋ- is more difficult to characterize in terms of transitivity, since the vast majority of meŋ- marked Malay verbs requires an object, while the ber- prefixed verbs present the exact opposite situation – a great share of them constitutes intransitive units (Blust 2013: 379). As to the functions of the presumed building blocks of Pan *maR-, Blust (2013) hypothesizes that alongside ‘stative’ *ma-, the original function of *-ar- was to indicate some sort of plurality. With respect to the latter, there is evidence that the kind of plurality marked by *-ar- has to do with pluractionality/collective action: in Central Tagbanwa, for instance, -Vr- marks collective action, which can be easily interpreted as reciprocal with some predicates (n<ur>unut ‘accompany each other’; Blust 2013: 390); in Sundanese -ar-/-al- are used to mark verb plurals, i.e. plural agents or patients, as in di-b<ar>awa, pass-carry<plur>, ‘be carried (of more than one)’ versus di-bawa, pass-carry, ‘be carried’, s<ar>are, sleep<plur>, ‘to sleep (of more than one)’ versus sare ‘to sleep’ (Blust 2013: 392).

A point on which Ross (2002) and Kaufman (2009) agree is the presence of the actor voice infix *<um> in *ma(R-) (<*p<um>a(R-)). This infix would be ultimately responsible for the development of (mostly intransitive or at least transitivity-neutral) agent-oriented verbs from different bases. Blust (2013: 379), on the contrary, reconstructs *ma- as a PAn stative prefix without discussing the possible presence of an actor voice infix. The three reconstructions discussed in this section, however, agree on the primacy of the verbalizing function of *ma-, and stipulate, more or less explicitly, that the prefix in question is not a general verbalizing morpheme, but one with specific semantic effects: the three reconstructions agree that *-R- adds a specific nuance to the agent-oriented verbalizer *ma-, characterizing it in terms of voice (middle, cf. Kaufman 2009) or in terms of aspect (durativity, cf. Ross 2002; pluractionality, cf. Blust 2013) respectively.

Given these reconstructions, as well as the data from modern Austronesian languages, in the next section, we will provide a diachronic scenario through which continuators of *maR- have ended up covering functions falling within the middle domain, based on comparative evidence regarding the emergence and development of middle systems across languages.

4 From verbalizer to middle marker: a diachronic scenario

In the diachronic scenario to be reconstructed, the source is sufficiently clear: the middle marker of Malayic languages can be ultimately traced back to a verbalizing morpheme. But how did such a diachronic source expand to cover a wide array of typically middle functions? It is this question that we try to answer in this section.

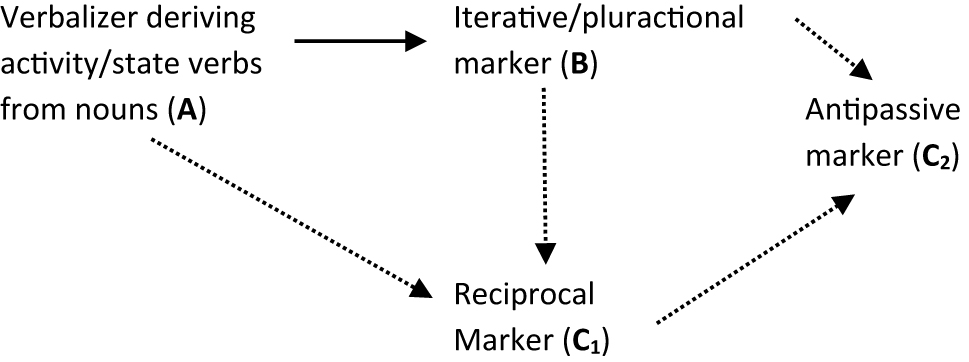

The first question to be addressed is the specific semantic contribution of *-R-. We might venture the hypothesis that the plural meaning of *-R- mentioned above had possibly aspectual implications, referring to non-telic or iterative configurations such as ongoing activities or states involving more than a single agent/action. As a result, the combination of *maR- with nominal bases yielded intransitive activity verbs infused with overtones of iterativity/pluractionality (‘to do X repeatedly’) or habituality, and stative verbs denoting a state holding of two entities (‘to have X’/‘to be with X’). When the prefix started being added to transitive verbal bases, its special semantic nuances yielded intransitive iterative/pluractional verbs.[9] These early stages of the diachronic development at stake can be summarized as follows:

| Stage A: *maR- as a verbalizer deriving activity/state verbs from nouns > Stage B: *maR- as a strategy to derive iterative/pluractional verbs from transitive verbal bases |

Stages A and B are possibly responsible for subsequent extensions. There are two possible pathways, which do not necessarily exclude one another:

the reinterpretation of iterative/pluractional verbs as reciprocal predicates might have to do with the inherent iterativity of reciprocal configurations (X & Y hit each other implies repeated hitting events in which X and Y alternate as agents);

alternatively, a reciprocal reading might have been fostered by the inherent reciprocity of stative verbs derived from relational nouns indicating reciprocal relations such as husband, friend, enemy etc.; these nouns are turned into verbs by means of a verbalizer and acquire an inherent reciprocity when the resulting verb has a plural subject (friend > be friend with X [V < N] > be in a mutual friendship relation [with plural subjects]).

These two possibilities are represented in (10):

| Stage B: *maR- as a strategy to derive iterative verbs > Stage C1: *maR- as a reciprocal marker |

| Stage A: *maR- as a verbalizer deriving stative verbs from relational nouns > Stage C1: *maR- as a reciprocal marker |

Denominal verbs are also characterized by the non-individuation of the object: an object may be implied (e.g. ‘plant rice’ or ‘have hair’) but is not a distinguishable argument (in the terms of Kemmer 1993) in the conceptual structure of the event. Combined with the iterative/pluractional meaning component of *maR- discussed above, this semantic peculiarity of the source might be responsible for the development of *maR- as an antipassive marker (cf. Sansò 2017, 2018 for the iterative/habitual overtones of antipassive constructions and how these overtones are diachronically connected with the sources of these constructions). This is schematized in (11):

| Stage B: *maR- as a strategy to derive iterative/pluractional verbs > Stage C2: *maR- as an antipassive marker |

The diachronic scenario schematized in (11) is corroborated by what we know about the diachrony of antipassive constructions. There are cases in which a verbalizer develops into an antipassive marker, possibly by virtue of implying a non-individuated object that coincides with the base to which the verbalizer applies. A case in point is provided by Algonquian languages, where the formatives indicating “action on a general goal” (Wolfart 1973: 72) that derive from Proto-Algonquian *-ke: (among which Ojibwe -ige:, Rhodes 1976: 125, and Plains Cree -kē/-ikē) are possibly related to a formative with similar shape used as a denominal suffix that attaches to nouns to form activity verbs (cf. Ojibwe dehmin-ke ‘pick strawberries’ < dehmin- ‘strawberry’; cf. Valentine 2001: 418–419).

There is, however, a further theoretical possibility. As argued in Sansò (2017), reciprocal markers may develop into antipassive markers if they have collective semantics, i.e. if they indicate multiple action effected by different participants that act alternatively as agents and patients. The key notion motivating the reinterpretation of a reciprocal construction as an antipassive construction is the notion of co-participation, intended as a semantic feature of “constructions that imply a plurality of participants in the event they refer to, without assigning them distinct roles” (Creissels and Voisin-Nouguier 2008: 261). This process involves two stages: The reciprocal (X and Y hit each other) is first reinterpreted as an antipassive with plural subjects (X and Y hit), and only later with singular subjects (X hits). Therefore, it cannot be excluded that the reciprocal semantics of the reconstructed prefix be the forerunner of its antipassive uses, as represented in (12):

| Stage C1: *maR- as a reciprocal marker | > | Stage C2: *maR- as an antipassive marker |

| (X and Y hit each other | > | X and Y hit > X hits) |

The following Figure 1 represents all the possible diachronic semantic relations leading from the verbalizing function of *maR- to the reciprocal/pluractional/antipassive cluster of functions:

Possible diachronic semantic relations of ∗maR-.

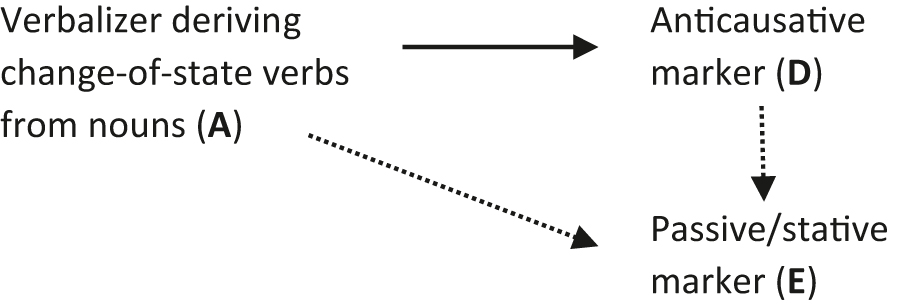

Possibly on a different pathway is the development of anticausative functions from the original verbalizing function. The semantic effects of verbalizers when combined with a base are generally quite unpredictable and idiosyncratic, from both a semantic and an aspectual point of view. In Uto-Aztecan languages, for instance, the reconstructed denominal verbal suffix *-tu(-a) displays a number of functions in the daughter languages ranging from stative ‘be n’ or anticausative ‘become n’ to ‘make n’ and ‘wear n’ (Haugen 2008; Langacker 1976: 170); cf. (13):

| Serrano (Californian Uto-Aztecan) | [Haugen 2008: 455] |

| ki:c-u’ |

| house-vblz |

| ‘build a house’ |

| ni:htavÿ-tu’ |

| old.woman-vblz |

| ‘become an old woman’ |

| chi:naru’-tu’ |

| Spanish-vblz |

| ‘speak Spanish’ |

In Seri (Hokan; cf. Marlett 2008) and Halkomelem (Salishan; cf. Gerdts and Hukari 2008: 502ff.; cf. 14), the same prefixes may yield (non-telic) stative verbs with the meaning ‘have n’ and (telic) change-of-state verbs meaning ‘get n’:

| Halkomelem (Salishan) | [Gerdts and Hukari 2008: 490] | |

| c- ‘have, get, make, do’: | ||

| kwəmləxw ‘root’ | > | c-kwəmləxw ‘get roots’ |

| s-tal̓əs ‘spouse’ | > | c-tal̓əs ‘get a spouse’ |

| s-q̓wqwəm ‘ax’ | > | c-q̓wqwm ‘have an ax’ |

| s-c̓əpxwən̓ ‘wart’ | > | c-c̓əpxwən̓ ‘have a wart’ |

The semantic underspecification of verbalizers, and their unpredictability in terms of the Aktionsart and transitivity of the resulting verb are well-known features of verbalization, and have been discussed in studies on denominal verbs since at least Clark and Clark (1979) and Aronoff (1980), who pointed out the context-dependent semantics of these verbs. It cannot therefore be excluded that with some non-verbal bases *maR- yielded telic predicates involving a change of state (to become n/adj). This function might have been exploited to obtain inchoative/change-of-state derived verbs from simple verbal bases, as in Standard Malay (cf. 1b), and possibly in Acehnese, with the additional involuntary meaning that represents a predictable semantic development of anticausatives (cf. 8c).

The passive overtones found for the prefix me- in Balinese deserve some discussion. These overtones might be hypothesized to result from the anticausative meaning: anticausative > passive is indeed a very common development across languages (cf. Heine and Kuteva 2002: 44–45). The anticausative function of me-, however, does not seem to be attested in Balinese, which weakens the hypothesis that the anticausative is an intermediate stage between the original verbalizing function and the passive/stative function. An alternative explanation for the emergence of passive-like meanings of the prefixes in question is that the relevant examples do not represent real passives: Thus, me-jagur ‘be punched’ in (5b) might simply represent an original ‘get a punch (jagur)’, and in the following Standard Malay cases the function of bər- might be the original verbalizing one, with the passive/stative meaning being somehow parasitic to it (‘get an answer’ ≅ ‘get answered’; ‘have a writing’ ≅ ‘be written over’):

| Standard Malay | [personal knowledge] |

| bər-tulis (<tulis ‘write’) ‘written over’ or ‘having a writing (on it)’ |

| doa-nya | tak | bər-jawab |

| prayer-3sg | neg | bər-answer |

| ‘His prayer hasn’t been answered’ (lit.: ‘does not have an answer’) | ||

Cases like these are quite common in the languages discussed. The development of anticausative (and passive functions) from the original verbalizing function can thus be represented as in Figure 2:

Development of anticausative from the verbalizing function.

Although the diachronic details might not be as neat as in Figures 1 and 2, there is little doubt that a marker with the typical distribution of a middle marker would have its ultimate origin in a verbalizer primarily forming agent-oriented intransitive verbs from nominal bases.

5 Conclusions

This article has dealt with a cross-linguistic unusual multifunctionality pattern whereby one and the same marker is used as (i) a denominal verb formative deriving intransitive verbs from nouns, (ii) as a “middle” marker, covering an array of valency-reducing functions including reciprocal, antipassive, and anticausative, and (iii) as an obligatory marker on some verbs that often lack an unmarked counterpart, and that fall within verb classes that are typically middle-marked in languages displaying a non-oppositional middle marker. Such an unusual multifunctionality pattern is consistently attested throughout the Malayic sub-group and in the larger Malayo-Sumbawan group.

Extant reconstructions of the history of this prefix agree on the following facts: (i) its origin must be sought for in Proto-Malayo-Polynesian and possibly in late Proto-Austronesian, (ii) its verbalizing function is primary in diachronic terms, and (iii) there is an element of possibly an aspectual nature in the reconstructed formative. This paper has sketched a few diachronic scenarios through which a denominal verbalizer with aspectual nuances might have evolved into a reciprocal and an antipassive marker. These scenarios capitalize on certain features of the denominal verbs formed with the formative in question, including its pluractional/iterative character and the presence of an unindividuated object. Similarly, it has been shown that it is not uncommon for denominal verb formatives to display dynamic, change-of-state functions (become n /get n ) along with more stative functions (be n /have n ), in often unpredictable ways. This possibility might explain why one of the typically middle functions of the prefixes in question, namely the anticausative, is attested in some of the languages discussed.

The diachronic scenarios sketched in Figures 1 and 2 have not answered the question as to when the prefixes in question have spread to specific classes of verbs that are among those that are consistently middle-marked in languages in which there are non-oppositional middles, and thus the data discussed in this article cannot contribute to the debate on the directionality of the development oppositional > non-oppositional (cf. Inglese and Verstraete, 2023). It must be remarked, however, that the anticausative functions of verbs marked by these prefixes might have played a role in their extension to specific classes of verbs independently from the other developments discussed in this section. This is an issue that we leave for further research.

Abbreviations

- 1, 2, 3

-

1st, 2nd, 3rd person

- adj

-

adjective

- emph

-

emphatic

- intr.

-

intransitive

- intr

-

intransitivizer

- mid

-

middle

- n

-

noun

- neg

-

negation

- obj

-

object

- pan

-

Proto-Austronesian

- pmp

-

Proto-Malayo-Polynesian

- pass

-

passive

- pl

-

plural

- plur

-

pluractional marker

- proj

-

projective

- recp

-

reciprocal

- sg

-

singular

- tr.

-

transitive

- vblz

-

verbalizer

References

Adelaar, K. Alexander. 1984. Some proto-Malayic affixes. Bijdragen tot de Taal-Land- en Volkenkunde 140(4). 402–421. https://doi.org/10.1163/22134379-90003406.Search in Google Scholar

Adelaar, K. Alexander. 1992. Proto Malayic: The reconstruction of its phonology and parts of its lexicon and morphology. Canberra: Australian National University.Search in Google Scholar

Adelaar, K. Alexander. 2005. Malayo-Sumbawan. Oceanic Linguistics 44(2). 357–388. https://doi.org/10.1353/ol.2005.0027.Search in Google Scholar

Aronoff, Mark. 1980. Contextuals. Language 56. 744–758. https://doi.org/10.2307/413486.Search in Google Scholar

Asyik, Abdul Gani. 1987. A contextual grammar of Acehnese sentences. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan PhD Dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Austin, Peter K. 2001. Verbs, valence, and voice in Balinese, Sasak, and Sumbawan. In Peter, K. Austin, Barry, J. Blake & Margaret, Florey (eds.), Explorations in valency in Austronesian languages, 47–71. Melbourne: La Trobe University.Search in Google Scholar

Austin, Peter K. 2013. Tense, aspect, mood and evidentiality in Sasak, eastern Indonesia. In John Bowden (ed.), Tense, aspect, mood and evidentiality in languages of Indonesia, 41–56. Jakarta: Universitas Atma Jaya.Search in Google Scholar

Blust, Robert. 2013. The Austronesian languages. Canberra: Asia-Pacific Linguistics.Search in Google Scholar

Clark, Eve V. & Herbert H. Clark. 1979. When nouns surface as verbs. Language 55. 767–811. https://doi.org/10.2307/412745.Search in Google Scholar

Clynes, Adrian. 1995. Topics in the phonology and morphosyntax of Balinese based on the dialect of Singaraja, North Bali. Canberra: Australian National University PhD Dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Creissels, Denis. 2006. Syntaxe générale, une introduction typologique, Tome 1: Catégories et constructions. Paris: Lavoisier.Search in Google Scholar

Creissels, Denis & Sylvie Voisin-Nouguier. 2008. Valency-changing operations in Wolof and the notion of co-participation. In Ekkehard König & Volker Gast (eds.), Reciprocals and reflexives: Theoretical and typological explorations, 293–309. Berlin & New York: De Gruyter.10.1515/9783110199147.289Search in Google Scholar

Crouch, Sophie Elizabeth. 2009. Voice and verb morphology in Minangkabau, a language of West Sumatra, Indonesia. Perth: University of Western Australia MA Dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

DeBusser, Rik L. J. 2009. Towards a grammar of Takivatan Bunun. Selected topics. Melbourne: La Trobe University PhD Dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Gerdts, Donna B. & Thomas E. Hukari. 2008. Halkomelem denominal verb constructions. International Journal of American Linguistics 74. 489–510. https://doi.org/10.1086/595575.Search in Google Scholar

Haugen, Jason D. 2008. Denominal verbs in Uto-Aztecan. International Journal of American Linguistics 74. 439–470. https://doi.org/10.1086/595573.Search in Google Scholar

Heine, Bernd & Tania Kuteva. 2002. World lexicon of grammaticalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511613463Search in Google Scholar

Inglese, Guglielmo. 2022. Towards a typology of middle voice systems. Linguistic Typology 26(3). 489–531. https://doi.org/10.1515/lingty-2020-0131.Search in Google Scholar

Inglese, Guglielmo & Jean-Christophe Verstraete. 2023. Evidence against unidirectionality in the emergence of middle voice systems – Case studies from Anatolian and Paman. STUF/Language Typology and Universals 76(2). 235–265.10.1515/stuf-2023-2010Search in Google Scholar

Jonker, Johann Christoph Gerhard. 1904. Eenige verhalen in talen, gesproken op Sumbawa, Timor en omliggende eilanden. Bijdragen tot de Taal-Land- en Volkenkunde van Nederlandisch-Indië 56. 245–289. https://doi.org/10.1163/22134379-90002004.Search in Google Scholar

Kaufman, Daniel. 2009. On *pa-, *pa<R>- and *pa<ŋ>-. Paper presented at the ICAL 11, Aussois.Search in Google Scholar

Kemmer, Suzanne. 1993. The middle voice. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.10.1075/tsl.23Search in Google Scholar

Klaiman, M. H. 1991. Grammatical voice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Langacker, Ronald W. 1976. Non-distinct arguments in Uto-Aztecan. Berkeley: University of California Press.Search in Google Scholar

Marlett, Stephen A. 2008. Denominal verbs in Seri. International Journal of American Linguistics 74. 471–488. https://doi.org/10.1086/595574.Search in Google Scholar

Omar, Asmah Haji. 1969. The Iban language of Sarawak: A grammatical description. London: University of London PhD dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Rhodes, Richard Alan. 1976. The morphosyntax of the Central Ojibwa verb. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan PhD Dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Ross, Malcolm. 2002. The history and transitivity of western Austronesian voice and voice-marking. In Fay Wouk & Malcolm Ross (eds.), The history and typology of western Austronesian voice systems, 17–62. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics.Search in Google Scholar

Sansò, Andrea. 2017. Where do antipassive constructions come from? Diachronica 34(2). 175–218. https://doi.org/10.1075/dia.34.2.02san.Search in Google Scholar

Sansò, Andrea. 2018. Explaining the diversity of antipassives: Formal grammar versus (diachronic) typology. Language and Linguistics Compass 12(6). e12277. https://doi.org/10.1111/lnc3.12277.Search in Google Scholar

Seken, I Ketut, Sumaryono Basuki, I Made Gosong & I Gusti Putu Antara. 1990. Morfologi Bahasa Sumbawa. Jakarta: Pusat Pembinaan dan Pengembangan Bahasa Departemen Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan.Search in Google Scholar

Sumarsono, Made Nadera, Sumaryono Basuki, Nyoman Merdhana & Nengah Mertha. 1986. Morfologi dan sintaksis Bahasa Sumbawa. Jakarta: Pusat Pembinaan dan Pengembangan Bahasa Departemen Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan.Search in Google Scholar

Tjia, Johnny. 2007. A grammar of Mualang: An Ibanic language of Western Kalimantan, Indonesia. Leiden: University of Leiden PhD Dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Valentine, J. Randolph. 2001. Nishnaabemwin reference grammar. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.Search in Google Scholar

Wolfart, H. Christoph. 1973. Plains Cree: A grammatical study. Transactions of the American Philological Society 63(5). 1–90. https://doi.org/10.2307/1006246.Search in Google Scholar

Zeitoun, Elizabeth. 2002. Reciprocals in the Formosan languages: A preliminary study. Paper presented at the ICAL 9, Canberra.Search in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Introduction: towards a diachronic typology of the middle voice

- From (semi-)oppositional to non-oppositional middles: the case of Spanish reír(se)

- The Turkic middle voice system: deponency and paradigm reorganization

- Middle voice in Bantu: in- and detransitivizing morphology in Kagulu

- From verbalizer to middle marker: the diachrony of middle voice in Malayic

- Evidence against unidirectionality in the emergence of middle voice systems

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Introduction: towards a diachronic typology of the middle voice

- From (semi-)oppositional to non-oppositional middles: the case of Spanish reír(se)

- The Turkic middle voice system: deponency and paradigm reorganization

- Middle voice in Bantu: in- and detransitivizing morphology in Kagulu

- From verbalizer to middle marker: the diachrony of middle voice in Malayic

- Evidence against unidirectionality in the emergence of middle voice systems