Abstract

Remittances from Kerala’s migrant workers and professionals constitute a vital financial inflow, surpassing their relative significance in most other Indian states. With public debt nearing 60 % of NSDP, these transfers offer a potential buffer for debt sustainability. Applying Oates’ theory within Bohn’s debt-sustainability framework using an FMOLS model, and validated through Johansen testing, this study examines the remittance–debt nexus from 1980 to 2023. FMOLS results indicate a deterioration of debt sustainability despite substantial remittance inflows. The findings emphasize the need to reduce market borrowings, enhance the fiscal role of remittances, and promote policies supporting formal transfer channels, source diversification, remittance-linked investment, and financial literacy among migrant households to strengthen Kerala’s long-term fiscal resilience and enable more productive use of remittances.

1 Introduction

The introduction of liberalization policies by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) marked a turning point for many economies, as it facilitated the relaxation of trade regulations. This policy shift created enhanced employment opportunities and improved living standards in several emerging economies, which in turn led to increased migration of both formal and informal labour from less-developed regions in pursuit of better economic prospects. Consequently, foreign remittances have become a notable outcome of this labour migration.

For Kerala’s unemployed youth, these developments presented a promising avenue for better livelihoods, marking the beginning of the state’s history of mass labour migration. The economic conditions in Kerala, characterized by an abundant labour supply, matched the increasing demand for workers in Gulf countries. This interplay between demand and supply culminated in one of the largest labour migrations recorded in India. Thus, the socio-economic constraints within Kerala served as a critical push factor driving its workforce to seek opportunities overseas.

Given the significance of remittance inflows, the state of Kerala is selected for this study as it records the highest share of remittances in household income, according to the Reserve Bank of India’s (RBI) Inward Remittances Survey. Despite substantial remittance receipts, Kerala grapples with high debt liabilities. According to the Reserve Bank of India, the state’s public debt has accumulated significantly, with major contributions from market borrowings. However, research suggests that remittances have played an important role in mitigating this debt burden (Zachariah and Rajan 2004). Although remittances are received at the household level rather than directly by the state, they can indirectly support public finances. This occurs through channels such as increased household disposable income, which leads to higher savings, reduces reliance on government-sponsored welfare programs, and ultimately lowers public borrowing requirements. Additionally, enhanced consumption resulting from remittance inflows contributes to greater tax revenues, thereby reducing the state’s dependence on debt-financed expenditures (Dina Hendiyani and Zainuddin Iba 2023; Joseph et al. 2019).

Kerala, which holds the highest remittance-to-GDP ratio in India-the world’s top remittance-receiving country-has likely experienced improved debt sustainability as a result of these inflows. With 7.5 % of Kerala’s population involved in migration (Rajan 2024), the state serves as a pertinent context for examining region-specific migration trends. Nevertheless, a critical gap remains in the existing literature: while the broader developmental impacts of remittances are widely acknowledged, little empirical work has been done to explore the specific mechanisms through which remittances influence public debt sustainability. In particular, the question of whether remittances directly contribute to the state’s capacity to manage its debt obligations remains underexplored.

This study addresses that gap by applying Oates theory in the Bohn’s debt sustainability framework and the Fully Modified Ordinary Least Square(FMOLS) model to empirically evaluate the relationship between remittances and Kerala’s debt sustainability. Considering that remittances represent one of Kerala’s most significant financial resources, their inclusion in a debt sustainability analysis is both timely and essential. By doing so, the study seeks to offer new insights into the macroeconomic role of remittances in a regional economy burdened with high debt, while also informing more targeted policy responses. Thus here, this study aims to examine the effect of remittances on the debt sustainability of Kerala’s economy.

2 Literature Review

2.1 Country-Specific Policies and Reforms Enabling Remittances and Debt Management

Over time, foreign remittances have evolved into a critical element of globalization, significantly boosting labour mobility across borders. India has emerged as the largest global recipient of international remittances, with these inflows contributing approximately 3.4 % of the country’s Gross Domestic Product, as per the World Bank Report in 2021. The liberalization of the Indian economy, though regarded as an inevitable development (Ghosh 2006), opened up significant avenues for economic growth and catalysed a substantial increase in remittance inflows through labour migrations. However, Kerala had already experienced large-scale migration prior to the advent of globalization in India, driven by the Gulf migration wave that commenced in the 1970s. This migration was characterized by individuals crossing international borders in search of employment, education, career advancement, and improved living standards. Over time, the migration network expanded beyond the Gulf region to other parts of the world, as individuals pursued better economic opportunities and quality of life (Rajan and Zachariah 2018; Shah 2024).

Within India, Kerala has consistently stood out as a leading beneficiary, receiving remittances equivalent to 8 % of its Net State Domestic Product (NSDP), the highest share among Indian states according to Reserve Bank of India in 2021. The onset of large-scale external migration from Kerala in the 1970s can be primarily attributed to rising unemployment and high population density during that era (Prakash 1998). The absence of significant industrial development in the state forced a substantial portion of the population to rely on agriculture, resulting in widespread disguised unemployment (Zachariah and Rajan 2011). This socio-economic scenario coincided with the oil boom in Gulf countries, which created a surge in employment opportunities abroad (Prakash 1998). While this explanation is commonly accepted, few studies critically interrogate whether structural underdevelopment within Kerala’s economy has been persistently addressed or merely masked by the outward flow of labour and accompanying remittances-a key oversight in the existing literature.

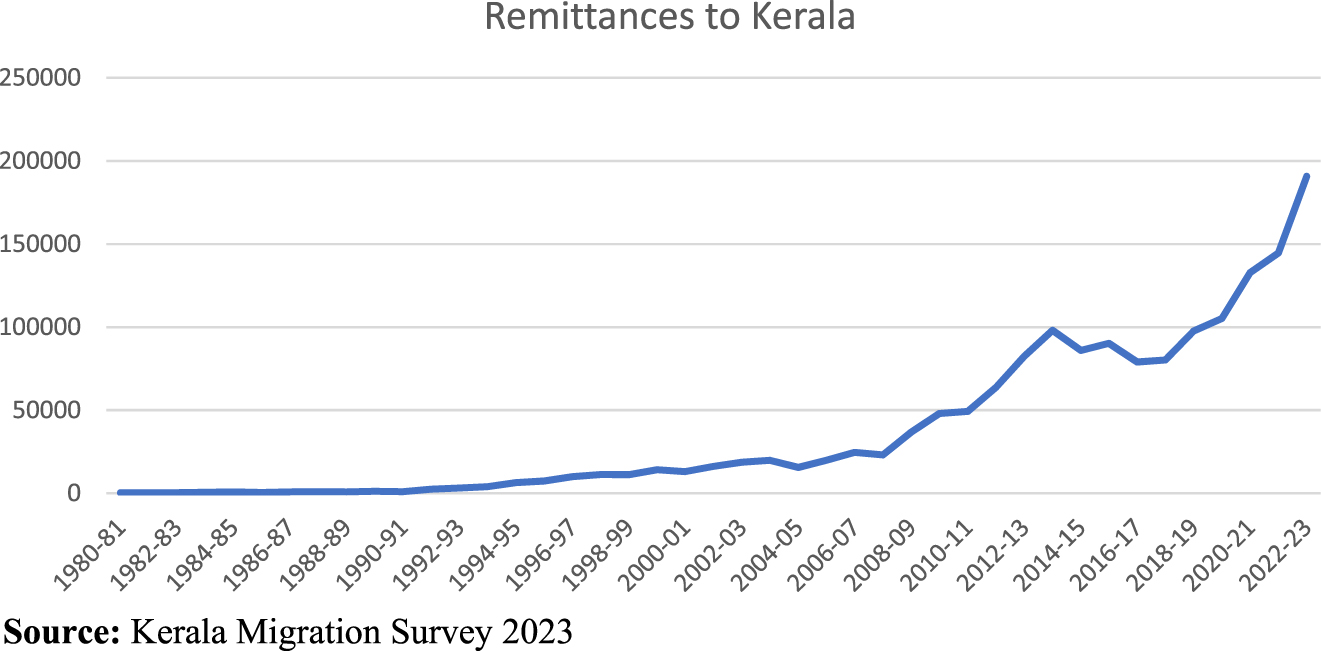

Nonetheless, the initial phases of migration were hindered by bureaucratic obstacles and regulatory constraints. The liberalization of the Indian economy, coupled with policy reforms, gradually addressed these issues by streamlining migration processes and reducing institutional barriers. These changes facilitated smoother migration, resulting in a marked increase in remittance inflows to home countries, particularly Kerala, thereby reinforcing its economic growth trajectory. However, much of this literature tends to assume a linear relationship between liberalization and remittance growth, without adequately considering how migration policies, visa regimes, and bilateral labour agreements also shape remittance flows. Thus, the upward trend in remittances to Kerala since the 1980s, as illustrated in Figure 1, calls for a more nuanced analysis beyond the conventional liberalization narrative. The figure highlights Kerala’s increasing dependence on remittance inflows, highlighting the growing significance of these transfers in the state’s economic landscape.

Foreign remittances to Kerala from 1980 to 2023 in crores. Source: Kerala migration survey 2023.

This sustained migration trend significantly boosted the inflow of international remittances to Kerala. In addition to remittances, the state experienced the introduction of new goods and technological innovations. These changes were not limited to the goods sector but extended to services such as banking and investment (Azeez and Begum 2009). The growth in remittances facilitated the expansion of banking infrastructure, reflected in Kerala’s notable progress in financial inclusion (Sethy and Goyari 2018). However, the assumption that financial inclusion is a direct consequence of remittances remains contested. There is limited empirical scrutiny into how far these banking services penetrate rural or economically weaker migrant households, or whether the financial inclusion is broad-based or skewed toward the remittance-receiving class.

Although the immediate effects of these remittances may not be readily apparent, their long-term impact becomes increasingly clear over time. This is consistent with Romer’s (1986) endogenous growth theory, which underscores the significance of human capital investment for sustainable economic growth. In countries receiving substantial remittances, improvements in human capital are noticeable. For example, in El Salvador-an economy with similarities to Kerala and substantial remittance inflows-there was significant growth in education and leisure activities (Acosta et al. 2009). In Kerala, remittances similarly exert a positive influence on the service or tertiary sector (Sunny et al. 2020), reinforcing the view that remittances contribute to enhancing human capital. However, this assumption often overlooks the quality and equity of such investments. The concentration of remittance spending on private education and health, often at the expense of public systems, raises critical questions about whether remittances reinforce or reduce socio-economic inequalities-an aspect underexplored in current literature.

Similarly, numerous studies have examined the effect of remittances on a country’s debt level. For instance, Mohapatra and Ratha (2010) found that the level of external debt incurred by governments significantly decreased due to the inflow of remittances. The addition of remittances to total income contributed to reducing external debt over time. This study analysed the combined effect of remittances on debt across various countries, including El Salvador, Ethiopia, Nepal, the Philippines, Rwanda, and Sri Lanka. While these cross-country analyses offer broad insights, they tend to aggregate effects and overlook context-specific fiscal structures, governance issues, and debt servicing capacity-all critical for understanding subnational contexts like Kerala.

Furthermore, Mijiyawa and Oloufade (2022) and Ratha (2007) observed that the slower pace of increase in external debt during 2016–17 could be attributed to the positive impact of remittance inflows. Yet, this perspective often fails to critically engage with countervailing evidence showing that increased remittance inflows may also encourage consumption-based expenditure and reduce fiscal discipline, thus indirectly sustaining unsustainable debt levels (Williams 2021). This duality warrants greater attention.

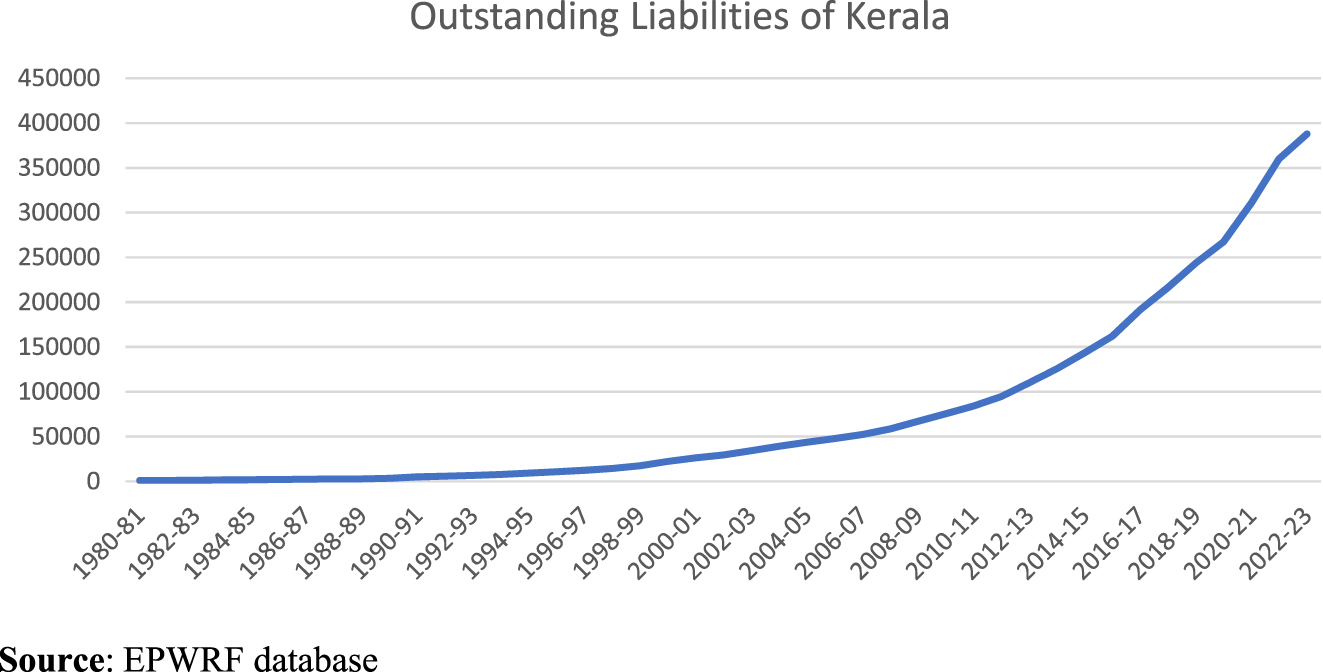

Kerala is currently facing a significant debt crisis (Government of Kerala 2022), with the state’s liabilities steadily increasing over the years, as illustrated in Figure 2 which has been extracted from Economic and Political Weekly Research Foundation database. This indicated the debt vulnerability of the state. Despite this, the substantial remittance inflows provide a potential solution to stabilize the state’s debt (Gapen et al. 2009). These remittances could significantly contribute to Kerala’s development, as they amount to 1.2 times the state’s revenue according to the Kerala Migration Survey of 2014. In fact, the remittances could potentially cover up to 60 % of Kerala’s outstanding state debt (Zachariah and Irudaya Rajan 2015). However, this proposition rests on an optimistic assumption that remittances are fungible and can be channelled into debt servicing or productive investment-despite evidence to the contrary, suggesting that remittances are primarily used for household consumption and social expenditures. This gap between theoretical potential and actual usage is insufficiently addressed in the current body of work.

Outstanding liabilities of Kerala from 1980 to 2023 in crores. Source: EPWRF database.

Certain post-COVID studies claim that although remittances experienced a temporary decline, they eventually rebounded to normal levels in small economies (Shimizutani and Yamada 2021). Thus, the trend shown in Figure 2 remains unchanged after 2020. While these findings are encouraging, they fail to consider the potential long-term vulnerabilities that external shocks such as pandemics and geopolitical crises pose to remittance-dependent economies like Kerala. A more critical exploration is needed to assess the resilience of remittance inflows under such conditions.

To gain a clearer understanding of debt sustainability, Bohn’s framework provides a straightforward approach. Bohn (1998) developed a model designed to assess an economy’s capacity to manage its debt by examining the relationship between the primary surplus and the debt-to-income ratio. If a positive correlation exists, public debt is considered sustainable. Although this framework offers important insights, it remains rooted in macroeconomic assumptions that may not fully apply to sub-national entities like Indian states, where fiscal autonomy and policy instruments are significantly constrained (George et al. 2023). Therefore, applying Bohn’s model to Kerala without accounting for these contextual limitations may oversimplify the debt-remittance dynamic.

Debt sustainability denotes an economy’s capacity to manage its debt without jeopardizing financial stability. According to a working paper by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), remittances play a crucial role in enhancing societal economic well-being (Gapen et al. 2009). The study emphasizes the potential of remittances to positively influence state debt levels. However, the optimistic tone of this argument overlooks the empirical reality that sustained fiscal deficits in Kerala co-exist with high remittance inflows. Thus, further research is necessary to disentangle this paradox and explore the causal mechanisms underpinning the relationship in specific contexts-particularly in major remittance-receiving economies such as Kerala.

2.2 Empirical Studies on the Impact of Remittances on the Economy

Remittances, primarily individual-to-individual or group transfers, have multifaceted effects across sectors of the economy. While their initial impact may appear limited, these funds often catalyze long-term economic growth through reinvestment (Azeez and Begum 2009). However, the notion of remittances as a linear driver of development merits scrutiny. For instance, while reinvestment through education can boost productivity-as seen post-COVID in smaller economies (Spahiu and Spahiu 2022)-this trajectory assumes efficient intersectoral linkages, which may not uniformly exist across contexts like Kerala.

Kerala consistently ranks highest among Indian states in terms of remittance-to-GDP ratios, with inflows contributing nearly 8 % to the state’s economy (Tewari and Mishra 2022). Kannan and Hari (2020) employed time-series analysis to estimate sectoral remittance flows, which offers methodological strength through empirical rigor. However, the study falls short in capturing remittance-induced structural changes beyond the short term. This review builds on their framework, aiming to contextualize Kerala’s remittance dependency more critically, especially in terms of vulnerability to external shocks.

Several studies argue that remittances facilitate financial development and economic growth (Azizi 2020; Mehta et al. 2021; Pandikasala et al. 2022; Saungweme et al. 2024). Post-pandemic shifts from informal to formal remittance channels (Mbiba and Mupfumira 2022) are often viewed positively. Yet, this optimistic reading often underplays persistent inequalities in access to these formal financial services. Furthermore, the positive correlation between remittances and development is not automatic. In Kerala, a substantial share of remittances goes toward consumption rather than entrepreneurship or public investments (Gapen et al. 2009), which raises concerns about the sustainability and transformative potential of these inflows.

Some studies underline the growth of Kerala’s service sector, attributing it to increased household disposable income and corresponding demand for health, education, and financial services (Lartey 2019; Azeez and Begum 2009). However, this analysis may overlook the risk of remittance-induced service sector inflation and underinvestment in productive sectors like manufacturing. While sectors such as banking and education have seen notable growth (Valatheeswaran 2015; Abraham 2024), it remains unclear whether these gains are inclusive or primarily concentrated among certain socio-economic groups.

Despite a decline in the number of emigrants from Kerala (Kannan and Hari 2020), remittance inflows remain stable due to higher overseas earnings (Aneja and Praveen 2022). This points to a quality-over-quantity shift in migration. However, this stability could mask deeper vulnerabilities; the COVID-19 pandemic forced many workers to return home, highlighting the fragility of remittance-dependence (Rajan 2024). As such, long-term reliance on high-wage remitters might not be sustainable.

The composition of Kerala’s emigrant labour force-largely daily wage earners in the Gulf (Gapen et al. 2009) also shapes the remittance economy. These earnings are often funnelled into consumption-heavy households, which boosts imports and suppresses industrial productivity. Olney (2015) argues that remittances can reduce labour supply and deter productive investment-an important but underexplored theme in Kerala’s context. Given that remittances are private transfers, their macroeconomic impact depends heavily on recipient behaviour (Ait Benhamou and Cassin 2021), a factor often sidelined in structural assessments. Behavioural analyses (Rahim et al. 2022; Sunny et al. 2020) suggest that unless aligned with policy incentives, remittance use may reinforce consumption traps rather than development pathways.

In Sub-Saharan Africa, remittances have been shown to mitigate COVID-related shocks and promote economic resilience (Nathaniel Oladunjoye 2022). While analogous lessons might apply to Kerala, such comparisons should be made cautiously, as differences in fiscal autonomy, social safety nets, and governance structures may mediate outcomes. Nonetheless, remittances could aid debt sustainability in Kerala by enabling households to meet obligations and reducing pressure on public welfare systems (Seshan 2020). Although studies (Rajan 2024; Misra et al. 2023) suggest that remittances can ease government debt burdens, the lack of consensus on long-term sustainability underscores the need for contextualized research. The existing literature highlights the substantial role of remittances in shaping Kerala’s economy, notably through the enhancement of household income, stimulation of the service sector, and reinforcement of human capital.

Nevertheless, two key research gaps remain. First, while the macroeconomic advantages of remittances are well-documented, there is a paucity of empirical research investigating their direct influence on Kerala-level debt sustainability, with Kerala representing a particularly understudied case. Most existing analyses tend to overlook the fiscal implications of remittance inflows at the subnational level. Second, the relationship between household-level remittance utilization and broader macroeconomic outcomes. This study seeks to address these gaps by empirically examining the influence of remittance inflows on Kerala’s debt dynamics, with a view to assessing their potential role in enhancing the state’s long-term debt sustainability.

3 Theoretical Framework

Oates (2005) second-generation theory of fiscal federalism highlights the role of external grants from the central government and their impact in creating soft budget constraints. The theory argues that such grants weaken subnational fiscal discipline by reducing incentives for responsible budgeting. Bohn (1998, 2008) developed a widely recognized methodology to assess debt sustainability by modelling the primary fiscal surplus as a function of the debt-to-income ratio-commonly referred to as the fiscal policy reaction function. A modified version of this framework remains in use today. While Bohn originally applied the model to national governments with full control over fiscal policy, this study adapts it to a subnational context by integrating it with the Oates theory. Kerala’s persistent reliance on remittances and borrowing to finance expenditures-more so than most other Indian states-makes the question of debt sustainability particularly relevant. This adaptation presume full fiscal autonomy at the subnational level and evaluates whether Kerala’s observed debt dynamics are consistent with the policy tools available to the state, in line with the intertemporal budget constraint. Similar applications of this methodology include the study by Renjith and Shanmugam (2020), which assessed the debt sustainability of Indian states individually and concluded that Kerala’s debt path was unsustainable. However, their analysis did not account for remittances in the NSDP, overlooking their potential role in influencing fiscal sustainability. Research that explicitly incorporates remittances into debt sustainability models remains scarce, with a notable exception being an IMF working paper by Gapen et al. (2009), which examined the impact of remittances on Lebanon’s debt dynamics.

Debt sustainability is determined when the primary balance-to-income ratio is dependent on the debt-to-income ratio. Bohn (1998) introduced a fiscal reaction function to describe this relationship, illustrating how a country’s fiscal balance influences debt dynamics. This function specifically analyses the impact of changes in the fiscal balance on the debt-to-GDP ratio. Furthermore, the reaction function incorporates additional factors, such as economic growth and fiscal policy, that can affect this dynamic. If a government accrues debt in the current period, it must increase the primary surplus in subsequent periods to maintain debt sustainability (Bohn 2008). Thus, the fiscal policy function can be articulated as follows:

Above equation depicts the primary debt sustainability fiscal reaction function derived by Bohn (1998).

In this research, we utilize Bohn’s (1998) fiscal framework to evaluate the debt sustainability of Kerala’s economy, while incorporating remittances as a key factor in the analysis.

3.1 Stylized Facts and Gap

However, as Figure 2 illustrates, the state’s liabilities and debt levels have been steadily increasing over the years. According to the RBI Report of 2023, Kerala is considered one of the most debt-vulnerable states in the country. Despite this, the Kerala economy does not fulfil the conditions outlined in Bohn’s sustainability framework for debt sustainability (Renjith and Shanmugam 2020), suggesting that it is not currently on a sustainable debt path. Given the steady flow of remittances, it is essential to investigate how these financial transfers influence the state’s debt situation. A thorough debt analysis will provide valuable insights into the role of remittances in maintaining Kerala’s fiscal stability. However, the financial support provided by remittances has the potential to manage these liabilities in a sustainable manner. By alleviating the debt burden on households and the state economy, remittances play an essential role in addressing fiscal challenges. Given these circumstances, it becomes essential to investigate whether remittances could play a role in enhancing the debt sustainability of Kerala’s economy.

3.2 Fiscal Policy Function

The primary objective of this research is to examine the effect of remittances on the debt sustainability of Kerala’s economy. To achieve this, the study adopts a model based on the framework developed by Gapen et al. (2009) in an IMF working paper. This framework, along with the incorporation of remittances, allows for the formulation of the following equation.

The equation above assesses the relationship between remittances and debt sustainability in Kerala’s economy over the period from 1981 to 2023. In this equation, remittances have been incorporated (Gapen et al. 2009; Kannan and Hari 2002). Remittances, offers a more holistic view of the economic resources available to the state. Also integrating the fiscal policy function with (Oates 2005), the variable central grants (CG) has been included representing the grants from central government to Kerala (regional) government. The whole adjustment into the model enhances the precision of our assessment of the role of remittances in supporting the debt sustainability of Kerala’s economy.

4 Data Sources and Methodology

This research is based on data concerning annual international remittances, central grants to state, Net State Domestic Product (NSDP), liabilities, aggregate expenditure, and the primary surplus of Kerala’s economy. The dataset spans from 1980 to 2023, with data from subsequent years including the post COVID-19 period. The time-series data used in this study is based on the Kerala Migration Survey 2018, which provides data up until 2020 and Kerala Migration Report 2023, consisting time series data till 2023. The data has been sourced from various institutions, including the working papers of the Centre for Development Studies (CDS), the International Institute of Migration and Development (IIMAD), the EPWRF Kerala Economic Review database, and the Economic and Statistics Department of the Kerala government. Additionally, the Reserve Bank of India’s (RBI) Inward Remittances Survey provides insights into the state’s current remittance trends. The remittance data is drawn using the time-series methodology developed by Kannan and Hari (2020) and as well as the data is available in Kerala migration report (Rajan 2024). The other all variables are extracted from the Reserve Bank of India statistics. While this approach enhances robustness, inherent assumptions may introduce potential errors. Validity is maintained through credible data sources; however, fluctuations in estimates may arise due to policy shifts, exchange rate fluctuations, and broader economic conditions (Kannan and Hari 2020). All monetary variables were expressed in crore rupees and adjusted to constant prices using the 2011–12 base year to ensure temporal comparability. To address potential distortions from atypical observations, log transformation was applied for variables other than ratios. Winsorization technique was also used to variables to limit the limit of extreme outliers. Winsorization is a statistical method used to stabilize data by reducing the undue impact of extreme values, wherein observations beyond specified percentile thresholds are replaced with the nearest values within those limits.

While global financial crises, such as those in 1991 and 2008 are known to have significantly influenced macroeconomic variables across many regions, their impact on Kerala’s remittance inflows and debt profile appears to be minimal. As illustrated in Figures 1 and 2, both remittances and the state’s outstanding liabilities followed a broadly consistent trajectory during and after these periods, with only marginal and temporary deviations. Moreover, the structural factors driving migration from Kerala, particularly the sustained demand for labour in Gulf economies continued to exhibit steady growth. There were no major policy reversals or disruptions in remittance governance or public finance management. To statistically examine the presence of any structural breaks, the study employs the Bai-Perron test (Bai and Perron 1998), thereby validating the observed trends and underlying explanations.

4.1 Variables Used

This study uses data on remittances, Net State Domestic Product (NSDP), liabilities, aggregate expenditure, and primary surplus. The analysis is based on the following four core variables:

PM (Primary Surplus to Modified Income Ratio): This ratio represents the relationship between the primary surplus and NSDP plus remittances. PM measures the fiscal balance in relation to the income available in the economy, factoring in remittances.

DM (Debt to Modified Income Ratio): This ratio evaluates the relationship between the state’s debt and NSDP plus remittances. The debt liability of Kerala serves as a proxy for debt, with remittances incorporated to assess the state’s debt relative to its comprehensive income, to include remittance inflows.

EXPD (Aggregate Expenditure): This variable reflects the total expenditure by the Government of Kerala, covering all spending activities across various sectors.

NSDP (Net State Domestic Product): NSDP measures the total income produced within Kerala’s economy after accounting for depreciation, acting as an indicator of the state’s overall economic output.

CG (Central Grants): This variable explains the grants provided by the central government to the Kerala government.

This study examines how the inclusion of remittances in the economy impacts debt sustainability. Debt sustainability is measured by two key ratios: the primary surplus to modified income (PM) and the debt to modified income (DM). Government expenditure (EXPD) and net state domestic product (NSDP) are transformed using logarithmic linear specifications to stabilize the data and reduce skewness, making the dataset more suitable for analysis. The ratios PM (primary surplus relative to remittances plus NSDP) and DM (debt relative to remittances plus NSDP) remain central in the model.

Within this framework, the PM ratio serves as the dependent variable representing fiscal health, while DM, EXPD, CG (central grants), and NSDP are the explanatory variables. Remittances significantly enhance Kerala’s net domestic product, so including them in fiscal ratios yields a more realistic assessment of the state’s debt management capacity. An increase in DM, indicating a higher debt burden relative to income, typically leads to a decline in PM, reflecting a worsening budget balance. Higher central grants (CG), which also capture the state’s dependence on the central government for fiscal support, can improve the primary surplus (PM) by providing additional non-debt resources. Thus, the model demonstrates that Kerala’s debt sustainability is influenced not only by its own production and fiscal policies but also by remittance inflows, external fiscal support, and its reliance on central government transfers.

4.2 Empirical Model

Based on the review of the theoretical and empirical literature, the following functional relationship was framed:

Here, PM is the ratio of primary surplus- NSDP plus remittances. This model regresses the PM with its lags and a set of explanatory variables, including the debt- NSDP plus remittances.

4.3 FMOLS Model

The Fully Modified Ordinary Least Squares (FMOLS) model is an non-parametric approach, introduced by (Phillips and Hansen 1990)is employed to examine long-term relationships among variables within a time-series framework. Its adoption in this study is justified by several key advantages. First, FMOLS accommodates variables integrated of order one, allowing the analysis of first-difference stationary series. Second, it addresses endogeneity, which is particularly relevant here, as remittances are likely endogenous to fiscal dynamics. Third, FMOLS performs well with small sample sizes, making it suitable for studies with limited data points. Fourth, it offers advantages over Dynamic Ordinary Least Square (DOLS) by more effectively adjusting for endogeneity, heteroscedasticity, and autocorrelation, including better handling of lags and leads (Kao and Chiang 2001; Pedroni 2001).

Initially the study uses the Zivot Andrews, Perron and Augmented Dicky Fuller (ADF) tests to check the presence of unit root or the degree of integration of each variable. If all the variables appear stationary at first difference but not at level the study proceeds with the help of Johansen cointegration method to check if the variables are cointegrated. If the variables are found out to be cointegrated, it confirms the presence of long-run relationship (Johansen 1995).

Initially the cointegration is established to ensure the long run relation should through Johansen cointegration technique. The vector error correction model thus obtained can be represented as.

This also can be written as:

where,

Where q is the total no of variables in the model, the matrix П captures the long-run relation between the variables. in the Trace test in Johansen test of cointegration gives the number of cointegrating vectors. The study conducts the stability tests like Ramsey RESET, CUSUM and diagnostic test for serial correlation, heteroskedasticity for FMOLS model using its OLS residuals. OLS residuals are taken for diagnostic analysis, as FMOLS involves non-linear corrections resulting in the non-standard character of the residuals (Phillips 1995).

4.4 FMOLS Specification

Developed a model which stands superior among many models at any integration order. It corrects the simultaneity and small sample bias through the inclusion of different leads and lags. The specification of the FMOLS model can be specified as follows:

where, Z t is the vector of explanatory variables ω i are the long run multipliers, coefficients represented as β the short run dynamics, ‘Δ’ is the first difference operator, ω 0 is the drift and ε t is the white noise error term.

5 Results and Discussion

The study’s analysis is conducted using EViews software which spans from year 1980–2023, including the years of COVID-19 pandemic. This study primarily aims to evaluate the influence of remittances on the debt sustainability of Kerala’s economy, employing Oates fiscal federalism theory into the Bohn’s fiscal reaction function as the analytical framework.

In the model, the dependent variable, PM, is defined as the ratio of the primary surplus to Modified Income (MI), where MI includes remittance inflows. The explanatory variables are DM, the debt-to-Modified Income ratio; EXPD, CG, the grants from central to regional government; the aggregate government expenditure of Kerala; and NSDP, the state’s gross domestic product. PM and DM are derived from Bohn’s framework with the same denotations above, and this helps in analysing the debt sustainability status of Kerala due to the remittance inclusion. The NSDP is included so that the State’s revenue fluctuations are included. Thus, while doing the analysis, the deviation from remittances will be automatically detected (Kaur et al. 2018). The variable EXPD explains the government expenditure interaction in the debt sustainability concept (Kaur et al. 2018). There can be a change in government spending patterns with the inclusion of remittances into the scenario.

5.1 Stationarity Test

The stationarity of both the dependent and explanatory variables was assessed using a combination of first-generation and second-generation unit root tests, including the Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) test, the Zivot-Andrews test, and the Perron test. These tests were employed to determine the order of integration of the variables. The null hypothesis in all three tests posits the presence of a unit root, indicating non-stationarity. A p-value <0.05 leads to the rejection of the null hypothesis, suggesting that the series is stationary. Conversely, a p-value > 0.05 implies the presence of a unit root, and the variable is tested at the next level of differencing.

The results revealed that the variables, Primary Surplus to Modified Income (PM), Debt to Modified Income (DM), Government Expenditure (EXPD), Central Grants (CG), and Net State Domestic Product (NSDP), are stationary at first difference, indicating they are integrated of order one, I(1). Based on these findings, the study employed the Johansen cointegration approach to test for long-run relationships, followed by the FMOLS (Fully Modified OLS) method for model estimation.

Table 1 presents the detailed stationarity results for each variable, showing the critical values for both the level and first-difference tests. The corresponding p-values are reported in brackets, indicating the statistical significance of the test results.

Stationarity tests.

| Variable | Zivot-andrews unit root test | Perron unit root test | ADF unit root test | Decision | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level | 1st diff. | Level | 1st diff. | Level | 1st diff. | ||

| PM | −5.08 | −5.08 | −3.63 | −3.63 | −2.95 | −2.95 | Stationary at 1st |

| (0.09) | (0.016) | (0.1) | (<0 .05) | (0.98) | (0.004) | difference | |

| DM | −5.08 | −5.08 | −3.41 | −3.41 | −3.52 | −3.52 | Stationary at 1st |

| (0.125) | (0.015) | (>0.99) | (0.05) | (0.95) | (0.005) | difference | |

| CG | −5.08 | −5.08 | −3.44 | −3.44 | −3.52 | −3.52 | Stationary at 1st |

| (0.094) | (0.012) | (0.99) | (0.01) | (0.06) | (0) | difference | |

| NSDP | −5.08 | −5.08 | −3.76 | −3.76 | −3.52 | −3.52 | Stationary at 1st |

| (0.071) | (0.023) | (>0.50) | (0.01) | (0.09) | (0) | difference | |

| EXPD | −5.08 | −5.08 | −3.76 | −3.76 | −3.52 | −3.52 | Stationary at 1st |

| (0.246) | (0.044) | (>0.50) | (0.01) | (0.07) | (0.0001) | difference | |

-

Zivot-Andrews, Perron and ADF unit root tests. Bracket implies the p-value. p-value <0.05 is significant.

5.2 Bai -Perron Breakpoint Test

Given the presence of 42 time-series observations, the likelihood of one or more structural breaks occurring over the period is considerable. To identify the potential breakpoint, the study employed the Bai and Perron (1998) multiple structural break test, which identified 2000 as a statistically significant break year.

To validate this finding, the Chow Breakpoint Test was conducted, which rejected the null hypothesis of no structural break at 2007. This result confirms the presence of a structural shift in that year. As shown in Table 2, the F-statistic > critical value, indicating that the break at 2007 is statistically significant. The Chow test F-statistic is also significant, further reinforcing the evidence of a structural break in the model during that period.

Breakpoint tests Bai-Perron and Chow breakpoint test.

| Bai perron break test | F-statistic | Scaled F-statistic | Critical value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 vs. 1 * | 5.676084 | 28.38042 | 18.23 |

| 1 vs. 2 | 2.45935 | 12.29675 | 19.91 |

|

|

|||

| Break date | 2000 (Sequential & repartition) | ||

|

|

|||

| Chow test | F-statistic | P-value | |

|

|

|||

| 5.676084 | 0.0007* | ||

-

* Significant at the 0.05 level.

The Kerala Economic Review (2000–2009) notes that the disruption in the state’s revenue and expenditure patterns led to increased reliance on market borrowings even before the implementation of the Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management (FRBM) Act. This shift was influenced by the People’s Plan Campaign, which devolved 40 % of the state’s plan budget to local governments, resulting in a structural transformation in budget allocation and fiscal balance (Isaac and Harilal 1997). The FRBM Act of 2003 further constrained state finances by reducing central grants. This in short implies decentralisation within decentralization which might have acted adversely. These changes highlight how national fiscal reforms and global shocks together reshaped Kerala’s debt sustainability and the evolving role of remittances in maintaining fiscal balance.

5.3 Cointegration for Long-Term Relationships

After confirming the stationarity of the variables, the Johansen cointegration test was employed to assess the presence of a long-run equilibrium relationship among them. The results are presented in Table 3 and include both the Trace test and the Maximum Eigenvalue test to determine the number of cointegrating vectors. If the Trace or Max-Eigen statistics exceed their respective 5 % critical values, the null hypothesis of no cointegration (r = 0) is rejected, indicating a statistically significant long-run relationship. As shown in Table 3, the Trace test identifies at least five cointegrating equation at the 5 % significance level. Similarly, the Maximum Eigenvalue test also supports the presence of two cointegrating equations. In short the cointegration test indicates the long-relationship of the debt sustainability of Kerala.

Johansen cointegration, cointegration results, unrestricted cointegration rank test (trace and maximum eigenvalue).

| Hypothesized no. of CE(s) | Eigenvalue | Trace | Maximum eigen value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trace statistic | Critical value | P-value | Max-eigen statistic | Critical value | P-value | ||

| None | 0.877252 | 281.6843 | 197.3709 | 0.0000 | 86.00244 | 58.43354 | 0.0000 |

| At most 1 | 0.746629 | 195.6819 | 159.5297 | 0.0001 | 56.28891 | 52.36261 | 0.0188 |

| At most 2 | 0.587464 | 139.3930 | 125.6154 | 0.0055 | 36.30274 | 46.23142 | 0.3801 |

| At most 3 | 0.517321 | 103.0902 | 95.75366 | 0.0142 | |||

| At most 4 | 0.499292 | 73.22570 | 69.81889 | 0.0261 | |||

-

Source: Author’s estimation from EViews software output. Trace test indicates 5 cointegrating eqn(s) at the 0.05 level. Max-eigenvalue test indicates 2 cointegrating eqn(s) at the 0.05 level.

5.4 FMOLS Regression Results

The equation is estimated by incorporating a structural break through interaction dummies using FMOLS, capturing the regime shift that occurred after 2000, as shown in Table 4. Notably, the coefficient for DM, reflecting the impact of remittances on debt sustainability, is statistically significant and positive in the pre-2000 period (p-value = 0.001; p < 0.05). However, when interacted with the post-2000-time dummy (DMD20), the coefficient becomes negative, indicating a structural change in the relationship. The interactive term (DMD20) captures this shift. The coefficient of −0.236 reflects the impact of the People’s Plan Campaign for decentralised planning and increased borrowing post-FRBM, to such an extent that even remittances could not offset the rising debt burden (Thekkedath et al. 2022). In other words, a 1-unit increase in the debt-to-income plus remittances ratio led to a 23.6 % decline in the primary surplus-to-income plus remittances ratio, whereas before the shift, a 1-unit increase in the same led to a 17.6 % rise in the primary surplus ratio. Notably, in the pre-2000 period, the coefficient was significant and positive, indicating that remittances previously supported debt sustainability. Along with post-FRBM effects, the People’s Plan Campaign for decentralised planning led to increased borrowings that reversed this trend, which is a serious concern. This can be attributed to a surge in borrowings that escalated liabilities.

FMOLS results. Dependant variable: PM.

| Variable | Coefficient | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| DM | 0.179909 | 0.0013* |

| CG | −0.005772 | 0.3408 |

| EXPD | 0.021333 | 0.0895 |

| NSDP | −0.078562 | 0* |

| DM*D20 | −0.236686 | 0.0002* |

| CG*D20 | 0.000376 | 0.9639 |

| EXPD*D20 | 0.085596 | 0* |

| NSDP*D20 | −0.06244 | 0* |

| C | 0.320301 | 0* |

| R-squared | 0.727434 | |

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.661357 |

-

* Significant at the 0.05 level.

Aggregate expenditure and state income remained statistically significant both before and after 2000. The continued insignificance of central grants in both periods can be interpreted through Oates’ second-generation theory of fiscal federalism. This perspective posits that central transfers have the potential to weaken fiscal discipline among subnational governments, particularly before 2000, by reducing incentives for prudent budget management. In the post-2000 era, central grants continued to be insignificant. Following the People’s Plan Campaign for decentralized planning (fiscal federalism within fiscal federalism) and Kerala’s increasing dependence on market borrowings, necessitated by FRBM Act which resulted in decreased central grants, this insignificance persisted.

The R-squared value is 0.727, indicating that the independent variables explain 72.7 % of the variation in the dependent variable. Moreover, the state’s income (NSDP) shows a negative relationship with debt sustainability both before and after 2000, indicating that the high and persistent debt burden overshadowed income growth.

Appendix 1 also presents the DOLS results with an R-squared of 98 %. It shows a similar outcome as FMOLS, but FMOLS is preferred in the study due to the factors discussed in the methodology.

5.5 VECM Results

The Error correction vector model used to check short-run dynamics in the FMOLS estimation is given in Table 4. The ECM for FMOLS model is depicted as:

The VECM captures the short-run dynamics of the system. Consistent with theoretical expectations, the negative sign of the coefficient indicates the system’s capacity to revert to long-run equilibrium after a short-run deviation. The statistical significance and magnitude of the coefficient imply a 30.49 % speed of adjustment toward equilibrium, confirming the presence of a stable long-term relationship among PM, DM, EXPD, CG, and NSDP. The detailed VECM estimation results are provided in the Appendix 2. The results from VECM also confirms the long-run relationships.

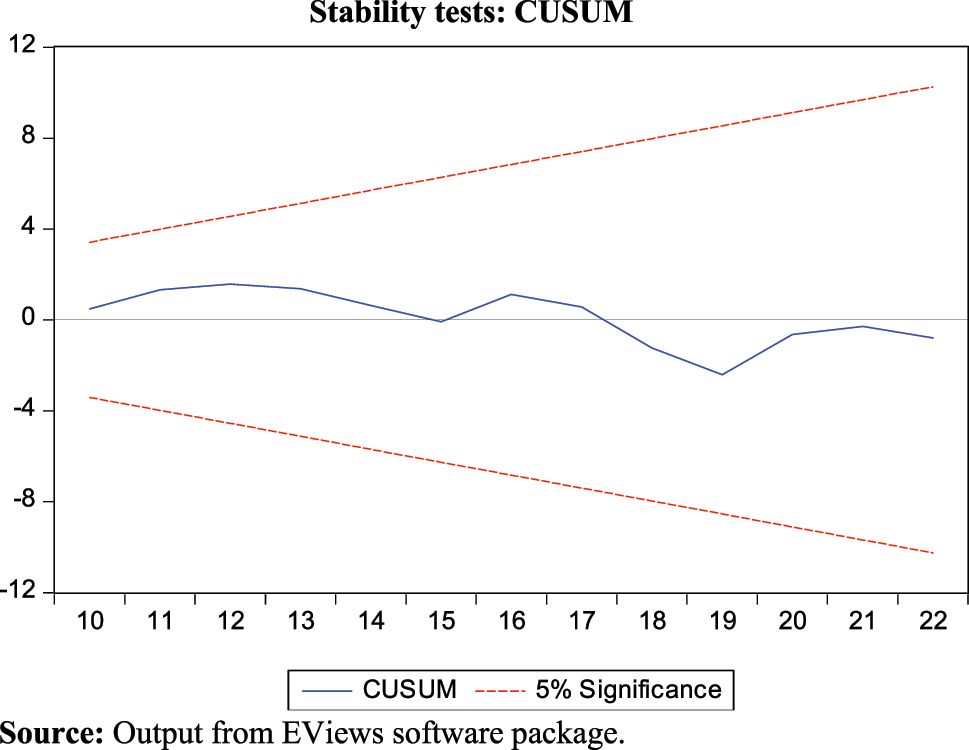

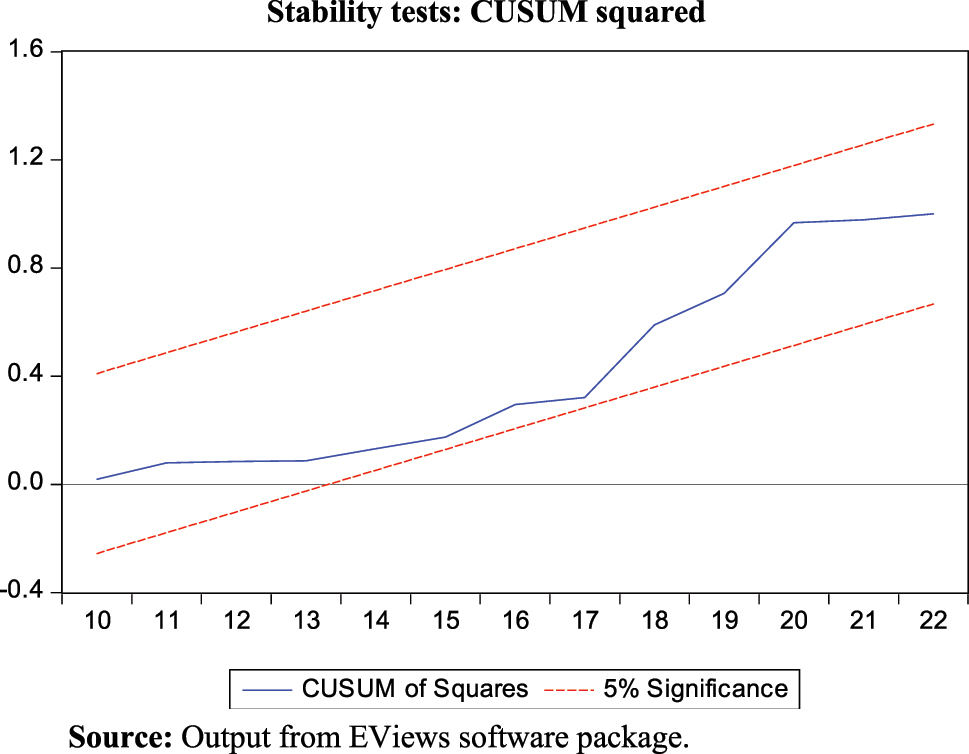

Both the VECM and FMOLS results acknowledge the presence of stable long-run relationship aligning with previous findings that emphasize the role of remittances in easing fiscal pressures in remittance-dependent economies (Ratha 2007; Zachariah and Rajan 2004). The diagnostic tests confirm the overall stability of the model. The residuals satisfy key assumptions normality, homoscedasticity, and absence of autocorrelation. The Ramsey RESET test further supports the absence of functional misspecification. CUSUM and CUSUMSQ stability tests were conducted. Both the CUSUM test and CUSUM square test indicates stability, with the plot remaining within the 5 % significance bounds. All diagnostic test results are provided in the Appendix 3.

Despite substantial remittance inflows, which enter the economy indirectly through households, the state’s reliance on market borrowings remained high. This was a result of declining central grants and Kerala’s shift to a new pattern of fiscal devolution under the People’s Plan (Antony and Renjith 2023). This transformation underscores the unintended consequences of fiscal federalism, where excessive dependence on centrally allocated grants can erode state autonomy and constrain fiscal discretion.

6 Concluding Remarks and Policy Implications

Based on the results, the inclusion of remittances, despite their high volume, does not appear to benefit the system significantly. Additionally, the deterioration in debt sustainability can largely be attributed to central transfers, which, under the existing framework of fiscal federalism, undermine the fiscal health of subnational governments. The formulation of policies that strategically channel international remittances could play a crucial role in enhancing debt sustainability moving forward. This study seeks to evaluate the extent to which remittances influence Kerala’s debt sustainability. Gaining an understanding of this relationship will offer critical insights that can inform government strategies and lead to the development of policies designed to optimize the use of remittances, contributing to better fiscal management and more sustainable debt levels(Pande 2018).

The analysis of debt sustainability in the context of remittances suggests that while Kerala’s economy has strong potential for long-term stability, the growing reliance on borrowings has offset the fiscal benefits of increased remittance inflows. Despite substantial remittances, debt sustainability has deteriorated, highlighting the need for a more prudent fiscal strategy especially the non-strategic devolution of budget.

To fully harness the advantages of remittance inflows, the government must reduce its dependence on market borrowings. This requires a multifaceted approach focused on strengthening non-debt revenue sources. First, enhancing tax buoyancy is essential-this includes broadening the state GST base and improving the efficiency of property and professional tax collection, particularly at the local government level. Second, mobilizing non-tax revenues is crucial. This can be achieved by monetizing underutilized public assets through mechanisms such as leasing, or by promoting public–private partnerships (PPPs). Third, the state should explore the monetization of high-potential sectors like tourism, where strategic investment planning can generate sustainable revenues without resorting to borrowing. Overall, by aligning fiscal management with the state’s remittance advantage, Kerala can work toward a more resilient and sustainable debt profile.

To strengthen the impact of remittances on Kerala’s fiscal health, a key strategy is to promote formal remittance channels. By improving digital payment infrastructure and offering incentives such as lower transaction costs, more remittances can be brought under government supervision. This enables the state to channel these funds into productive investments, creating broader economic benefits. A second recommendation is to encourage targeted investment and savings schemes for Non-Resident Keralites (NRKs). Given the high rate of permanent residency among migrants, schemes like remittance-linked diaspora or NRK bonds can attract long-term capital for sectors such as infrastructure, healthcare, and research. These instruments not only retain migrant contributions but also turn them into tools for public development. Additionally, remittances can be pooled into designated development funds, matched with public-private investments to finance essential projects in high-migration regions. This is especially useful in countering the decline in remittances from traditional sources like the Gulf. To ensure effective use, the government must also promote financial literacy among migrant households-training them to move beyond saving and toward strategic investing, insurance, and wealth-building. By enabling remittances to grow professionally, Kerala can both replace lost inflows and stimulate sustainable economic growth. In doing so, the state can enhance economic resilience and gradually reduce dependence on debt and volatile remittance trends. Yet, the study is not without limitations. Its findings are specifically applicable to Kerala, a subnational economic system operating within a framework of fiscal federalism. Therefore, the results cannot be generalized to other contexts. Another limitation is that, although Winsorization reduces the influence of outliers, it may slightly diminish data variability. However, this trade-off enhances the reliability and stability of the results without significantly compromising the overall representativeness of the dataset.

In conclusion, while the study’s findings indicate the deterioration of the Kerala’s current debt sustainability, they also highlight the need for policymakers to pivot towards investment-driven growth by leveraging remittances as capital for public development, especially when devolving budgets to local governments. Adopting such policies can promote long-term economic stability and sustainability, enabling Kerala to move beyond its historical reliance on remittances and to address the adverse effects of fiscal federalism.

-

Author contribution: Anjana Sabu is the first author. All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, methodology and first draft were prepared by Anjana Sabu. The analysis of the manuscript was written by Vineeth M and the same person commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: There is no conflict of interest, from our part, to disclose.

-

Research funding: We have not received any financial support for the publication of this manuscript.

-

Data availability: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the EPWRF repository, https://epwrfits.in/ and from data generated in Kannan and Hari (2020), https://doi.org/10.1007/s41027-020-00280.

Abbreviations

- GDP

-

Gross Domestic Product

- IMF

-

International Monetary Fund

- RBI

-

Reserve Bank of India

- NSDP

-

Net State Domestic Product

DOLS results

| Dependant variable: PM | ||

|---|---|---|

| Variable | Coefficient | Prob. |

| DM | 0.464682 | 0.0197* |

| CG | −0.010252 | 0.498 |

| EXPD | 0.063662 | 0.027* |

| NSDP | −0.200033 | 0.0048* |

| TRM*D20 | −0.539776 | 0.0141* |

| CG*D20 | 0.021655 | 0.292 |

| EXPD*D20 | 0.111855 | 0.0024* |

| NSDP*D20 | −0.089944 | 0.0008* |

| C | 0.775496 | 0.0047* |

| R-squared | 0.98306 | |

| Adj R-squared | 0.905618 |

-

*significant at 0.05.

VECM short run results

| Cointegrating eq: | Coeff | t -stats* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PM(-1) | 1.000000 | ||

| DM(-1) | 0.148718 | [−28.1139] | |

| CG(-1) | 0.003161 | [5.91340] | |

| EXPD(-1) | 2.79E-05 | [ 0.02780] | |

| NSDP(-1) | −0.035697 | [28.0618] | |

| DM(-1)*D20(-1) | −0.173830 | [31.2116] | |

| CG(-1)*D20(-1) | 0.003105 | [3.80960] | |

| EXPD(-1)*D20(-1) | −0.078998 | [−65.9510] | |

| NSDP(-1)*D20(-1) | −0.056543 | [ 86.5981] | |

| C | −0.179227 | ||

|

|

|||

| Error correction | |||

| D(PM) | −0.3049591 | [−2.02435] | |

|

|

|||

| R-squared | 0.715919 | Adj R-squared | 0.446043 |

| F-statistic | 2.6527(0.017) | DW stat | 2.025657 |

-

* Significant if t -stats >|1.96|

Diagnostic and stability tests

VEC residual test results

| Correlation LM test | Normality test | Heteroskedasticity test | Ramsey RESET | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LM-stat | Prob | Component | Jarque-bera | Df | Prob. | Chi-sq | Df | Prob. | t-stats | Df | Prob. |

| 63.995 | 0.92 | Joint | 12.38514 | 18 | 0.83 | 1,244.238 | 1,224 | 0.337 | 1.777133 | 33 | 0.0848 |

Stability tests: CUSUM

Source: Output from EViews software package.

Stability tests: CUSUM squared

Source: Output from EViews software package.

References

Abraham, A. 2024. “Role of Household Socio-economic Status in Determining the Impact of Remittances on Human Capital Investment.” In India Migration Report 2023: Student Migration, 231–51. Taylor and Francis.10.4324/9781003490234-13Search in Google Scholar

Acosta, P. A., E. K. Lartey, and F. S. Mandelman. 2009. “Remittances and the Dutch Disease.” Journal of International Economics 79 (1): 102–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2009.06.007.Search in Google Scholar

Ait Benhamou, Z., and L. Cassin. 2021. “The Impact of Remittances on Savings, Capital and Economic Growth in Small Emerging Countries.” Economic Modelling 94 (December 2019): 789–803. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2020.02.019.Search in Google Scholar

Aneja, R., and A. Praveen. 2022. “International Migration Remittances and Economic Growth in Kerala: an Econometric Analysis.” Journal of Public Affairs 22 (1). https://doi.org/10.1002/pa.2411.Search in Google Scholar

Antony, S., and P. S. Renjith. 2023. “Does Increased Borrowing Lead to Higher Development Spending in Kerala?” Kerala Economy 4 (4): 42–50.Search in Google Scholar

Azeez, A., and M. Begum. 2009. “Gulf Migration, Remittances, and Economic Impact.” Journal of Social Sciences 20 (1): 55–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/09718923.2009.11892721.Search in Google Scholar

Azizi, S. S. 2020. “Impacts of Remittances on Financial Development.” Journal of Economic Studies 47 (3): 467–477, https://doi.org/10.1108/JES-01-2019-0045.Search in Google Scholar

Bai, J., and P. Perron. 1998. “Estimating and Testing Linear Models with Multiple Structural Changes.” Econometrica 66 (1): 47. https://doi.org/10.2307/2998540.Search in Google Scholar

Bohn, H. 1998. “The Behaviour of US Public Debt and Deficits.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 113 (3): 949–63. https://doi.org/10.1162/003355398555793.Search in Google Scholar

Bohn, H. 2008. “The Sustainability of Fiscal Policy in the United States.” Sustainability of Public Debt (15): 15–49.10.7551/mitpress/7756.003.0003Search in Google Scholar

Gapen, M. T., M. Y. Abdih, M. A. Mati, and M. R. Chami. 2009. “Fiscal Sustainability in Remittance-dependent Economies.” International Monetary Fund. https://ssrn.com/abstract=1475520.Search in Google Scholar

George, J., A. Menon, and N. Thomas. 2023. “From Fiscal Crisis to the Creation of off-budget and Contingent Liabilities in Kerala.” Economic and Political Weekly 58 (44): 49–58.Search in Google Scholar

Ghosh, A. 2006. “Pathways Through Financial Crisis: India.” Global Governance 12 (4): 413–29, https://doi.org/10.1163/19426720-01204006.Search in Google Scholar

Government of Kerala. 2022. Kerala Economic Review 2022. State Planning Board, Thiruvananthapuram.Search in Google Scholar

Hendiyani, Dina, and Zainuddin Iba. 2023. “Does Foreign Direct Investment Reduce Growth Government Debt?” International Journal of Economics (IJEC) 2 (1): 151–61. https://doi.org/10.55299/ijec.v2i1.438.Search in Google Scholar

Isaac, T. M. Thomas, and K. N. Harilal. 1997. “Planning for Empowerment: People’s Campaign for Decentralised Planning in Kerala.” Economic and Political Weekly 32 (1/2): 53–8.Search in Google Scholar

Johansen, S. 1995. “A Statistical Analysis of Cointegration for I(2) Variables.” Econometric Theory 11 (1): 25–59. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266466600009026.Search in Google Scholar

Joseph, R., M. Potocky, C. Girard, P. Stuart, and B. Thomlison. 2019. “Concurrent Participation in Federally-Funded Welfare Programs and Empowerment Toward Economic Self-Sufficiency.” Journal of Social Service Research 45 (3): 319–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/01488376.2018.1480558.Search in Google Scholar

Kannan, K. P., and Hari, K. S. 2002. “Kerala’s Gulf Connection: Emigration, Remittances and their Macroeconomic Impact 1972–2000,” Centre for Development Studies, Trivendrum Working Papers 328, Centre for Development Studies: Trivendrum, India.Search in Google Scholar

Kannan, K. P., and K. S. Hari. 2020. “Revisiting Kerala’s Gulf Connection: Half a Century of Emigration, Remittances and their Macroeconomic Impact, 1972–2020.” Indian Journal of Labour Economics 63 (4): 941–967, https://doi.org/10.1007/s41027-020-00280-z.Search in Google Scholar

Kao, C., and M. H. Chiang. 2001. “On the Estimation and Inference of a Cointegrated Regression in Panel Data.” In Nonstationary Panels, Panel Cointegration, and Dynamic Panels, 179–222. Emerald Group Publishing Limited.10.1016/S0731-9053(00)15007-8Search in Google Scholar

Kaur, B., A. Mukherjee, and A. P. Ekka. 2018. “Debt Sustainability of States in India: an Assessment.” Indian Economic Review 53 (1–2). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41775-018-0018-y.Search in Google Scholar

Lartey, E. K. 2019. “The Effect of Remittances on the Current Account in Developing and Emerging Economies.” Economic Notes: Review of Banking, Finance and Monetary Economics 48 (3): e12149. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecno.12149.Search in Google Scholar

Mbiba, B., and D. Mupfumira. 2022. “Rising to the Occasion: Diaspora Remittances to Zimbabwe During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” World Development Perspectives 27 (C): 100452, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wdp.2022.100452. 35966611.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Mehta, A. M., M. Qamruzzaman, A. Serfraz, and A. Ali. 2021. “The Role of Remittances in Financial Development: Evidence from Nonlinear ARDL and Asymmetric Causality.” The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business 8 (3): 139–54.Search in Google Scholar

Mijiyawa, A. G., and D. K. Oloufade. 2022. “Effect of Remittance Inflows on External Debt in Developing Countries.” In Open Economies Review (Issue 0123456789). Springer US.10.1007/s11079-022-09675-5Search in Google Scholar

Misra, S., K. Gupta, and P. Trivedi. 2023. “Sub-National Government Debt Sustainability in India: an Empirical Analysis.” Macroeconomics and Finance in Emerging Market Economies 16 (1): 57–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/17520843.2021.1948171.Search in Google Scholar

Mohapatra, S., and D. Ratha. 2010. Impact of the Global Financial Crisis on Migration and Remittances. Washington, DC: World Bank.10.1596/10210Search in Google Scholar

Nathaniel Oladunjoye, O. 2022. “Remittance Inflow and the Sustainability of Selected Sub-saharan African Countries During Covid-19 Pandemic.” African Journal of Business and Economic Research 1 (1): 7–25. https://doi.org/10.31920/1750-4562/2022/Sina1.Search in Google Scholar

Oates, W. E. 2005. “Toward A Second-Generation Theory of Fiscal Federalism.” International Tax and Public Finance 12 (4): 349–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-005-1619-9.Search in Google Scholar

Olney, W. 2015. “Remittances and the Wage Impact of Immigration.” Journal of Human Resources 50 (3): 694–727, https://doi.org/10.3368/jhr.50.3.694.Search in Google Scholar

Pande, A. 2018. “India’s Experience with Remittances: a Critical Analysis.” The Round Table 107 (1): 33–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/00358533.2018.1424078.Search in Google Scholar

Pandikasala, J., I. Vyas, and N. Mani. 2022. “Do Financial Development Drive Remittances? Empirical Evidence from India.” Journal of Public Affairs 22 (1). https://doi.org/10.1002/pa.2269.Search in Google Scholar

Pedroni, P. 2001. “Fully Modified OLS for Heterogeneous Cointegrated Panels.” In Nonstationary Panels, Panel Cointegration, and Dynamic Panels, 93–130. Emerald Group Publishing Limited.10.1016/S0731-9053(00)15004-2Search in Google Scholar

Phillips, P. C. B. 1995. “Fully Modified Least Squares and Vector Autoregression.” Econometrica 63 (5): 1023. https://doi.org/10.2307/2171721.Search in Google Scholar

Phillips, P. C. B., and B. E. Hansen. 1990. “Statistical Inference in Instrumental Variables Regression with I(1) Processes.” The Review of Economic Studies 57 (1): 99. https://doi.org/10.2307/2297545.Search in Google Scholar

Prakash, B. A. 1998. “Gulf Migration and its Economic Impact: the Kerala Experience.” Economic and Political Weekly: 3209–13.Search in Google Scholar

Rahim, S., S. Ali, and S. Wahab. 2022. “Does Remittances Enhances Household’s Living Standard? Evidence from Pre- and Post Crisis.” Journal of Public Affairs 22 (2): e2442, https://doi.org/10.1002/pa.2442.Search in Google Scholar

Rajan, S. I. 2024. “Migration and Development: New Evidence from the Kerala Migration Survey 2023.” Migration and Development 13 (2): 139–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/21632324241306512.Search in Google Scholar

Rajan, S. I., and K. C. Zachariah. 2018. “Kerala Migration Survey 2016: New Evidences.” In India Migration Report 2017, 289–305. India: Routledge.10.4324/9781351188753-18Search in Google Scholar

Ratha, D. 2007. “Leveraging Remittances for Development.” Policy Brief 3 (11): 1–16.Search in Google Scholar

Renjith, P. S., and K. R. Shanmugam. 2020. “Dynamics of Public Debt Sustainability in Major Indian States.” Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy 25 (3): 501–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/13547860.2019.1668138.Search in Google Scholar

Romer, P. M. 1986. “Increasing Returns and long-run Growth.” Journal of Political Economy 94 (5): 1002–37. https://doi.org/10.1086/261420.Search in Google Scholar

Saungweme, T., G. Maluleke, and N. M. Odhiambo. 2024. “Asymmetric Impact of Financial Development on Economic Growth in Mauritius.” Statistics, Politics, and Policy 15 (2): 221–43. https://doi.org/10.1515/spp-2023-0019.Search in Google Scholar

Seshan, G. 2020. “Migration and Asset Accumulation in South India: Comparing Gains to Internal and International Migration from Kerala.” In India Migration Report 2020, 326–58. Routledge India.10.4324/9781003109747-18Search in Google Scholar

Sethy, S.K., and P. Goyari. 2018. “Measuring Financial Inclusion of Indian States: An Empirical Study.” Indian Journal of Economics and Development 14 (1): 111, https://doi.org/10.5958/2322-0430.2018.00012.4.Search in Google Scholar

Shah, I. A. 2024. “The Effect of Remittances on the Indian Economy.” International Economics and Economic Policy 21 (4): 771–785, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10368-024-00611-1.Search in Google Scholar

Shimizutani, S., and E. Yamada. 2021. “Resilience Against the Pandemic: the Impact of COVID-19 on Migration and Household Welfare in Tajikistan.” PLoS One 16 (9): e0257469. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0257469.Search in Google Scholar

Spahiu, M. J., and B. J. Spahiu. 2022. “The Factors Influencing Gross Domestic Product Growth in the Post-pandemic Period: the Case of Kosovo.” Journal of Liberty and International Affairs 8 (2): 136–49. https://doi.org/10.47305/JLIA2282136s.Search in Google Scholar

Sunny, J., J. K. Parida, and M. Azurudeen. 2020. “Remittances, Investment and New Emigration Trends in Kerala.” Review of Development and Change 25 (1): 5–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/0972266120932484.Search in Google Scholar

Tewari, S., and R. Mishra. 2022. “Headwinds of COVID-19 and India’s Inward Remittances.” RBI Bulletin 75 (7): 137–159.Search in Google Scholar

Thekkedath, R., M. Dileepkumar, A. Babu, and C. Haritha. 2022. “Public Debt of Kerala State and Related Risk Analysis: an Econometric Study.” Journal of Economic Policy and Research 18 (1): 1–23.Search in Google Scholar

Valatheeswaran, C. 2015. “International Remittances and Household Expenditure Patterns in Tamil Nadu.” Indian Journal of Labour Economics 58 (4): 631–652, https://doi.org/10.1007/s41027-016-0042-3.Search in Google Scholar

Williams, K. 2021. “Do Remittances Condition the Relationship Between Trade and Government Consumption?” Applied Economics Letters 28 (18): 1571–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504851.2020.1834072.Search in Google Scholar

Zachariah, K. C., and S. I. Rajan. 2011. “Impact of Remittances of Non-resident Keralites on Kerala’s Economy and Society.” Indian Journal of Labour Economics 54 (3): 503–26.Search in Google Scholar

Zachariah, K. C., and S. Irudaya Rajan. 2015. “Dynamics of Emigration and Remittances in Kerala: Results from the Kerala Migration Survey 2014”.Search in Google Scholar

Zachariah, K. C., and S. I. Rajan. 2004. “Gulf Revisited Economic Consequences of Emigration from Kerala: Emigration and Unemployment”.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editors Note

- Editors’ Note

- Special Issue: Emotional Dynamics of Politics and Policymaking; Guest Editors: Georg Wenzelburger and Beatriz Carbone

- Bringing Emotions into the Study of Responsiveness: The Case of Protective Policies

- Emotional Reactions to Protective Policies on the Political Spectrum

- Regular Articles

- Determinants of Political Instability in ECOWAS (1991–2022)

- The Impact of International Remittances on Public Debt Sustainability in Kerala: Evidence from the FMOLS Approach

- Bayesian Analysis of Tuberculosis Cases in Bolgatanga Municipality, Ghana–West Africa

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editors Note

- Editors’ Note

- Special Issue: Emotional Dynamics of Politics and Policymaking; Guest Editors: Georg Wenzelburger and Beatriz Carbone

- Bringing Emotions into the Study of Responsiveness: The Case of Protective Policies

- Emotional Reactions to Protective Policies on the Political Spectrum

- Regular Articles

- Determinants of Political Instability in ECOWAS (1991–2022)

- The Impact of International Remittances on Public Debt Sustainability in Kerala: Evidence from the FMOLS Approach

- Bayesian Analysis of Tuberculosis Cases in Bolgatanga Municipality, Ghana–West Africa