Abstract

Despite the disparity in unemployment rates across gender, race and provinces, no study has captured the influence of military spending on unemployment rates among these groups in South Africa (SA). Thus, this study investigated the effects of military spending on total, gender, racial and provincial unemployment in SA over 2008Q1 to 2023Q4. The study applied Autoregressive distributed lag model (ARDL), Dynamic ARDL and Kernel-based Regularized Least Squares (KRLS), to predict the counterfactual shocks of unemployment rates based on a ±1 % change in military spending. From the ARDL, a rise in military spending reduced total, male, female, black race, and Gauteng, Eastern Cape, Mpumalanga Kwazulu Natal and Northwest provinces’ unemployment rates, in the short- and long run, but increased it among the Coloured, White and the Indian/Asian races and the Western Cape, Northern Cape and Free State provinces, in the short and long run. The DARDL simulation and the KRLS showed that a 1 % decrease (increase) in military spending increased (reduced) total, male, female, Black and North West, Gauteng, Eastern Cape, Mpumalanga, KwaZulu Natal and Limpopo unemployment rates in the short run before flattening in the long run. Conversely, a 1 % decrease (increase) in military spending reduced (increased) the unemployment rates in the Coloured, White and Indian/Asian Races, Western Cape, Northern Cape and Free State Provinces, in the short run while flattening it in the long run. The effect of military spending in SA are not homogeneous among the Races and Provinces. Therefore, government policies aimed at curbing unemployment should recognise the peculiarities of the races and provinces.

1 Introduction

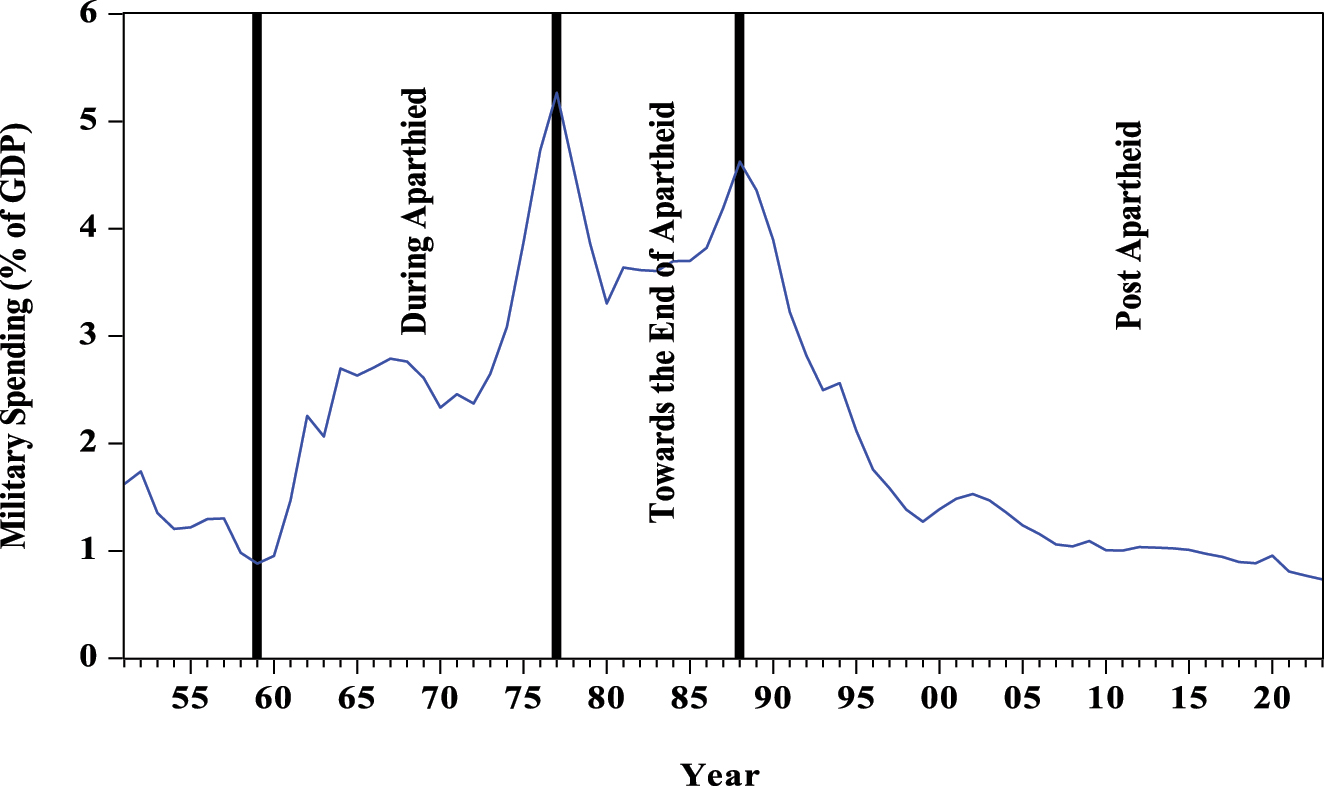

Historically, military spending in South Africa has been characterised by cyclical patterns, marked by periods of heavy investment in military capabilities leading to surges in expenditure, followed by significant declines (Gopaul, Van der Lingen, and Oosthuizen 2024). This trend is illustrated in Figure 1, which depicts military spending as a percentage of GDP since the 1950s. As shown in the figure, historical trends in military spending can be divided into three key periods: the apartheid era, the late apartheid transition period and the post-apartheid era.

Historical trend of military spending (% of GDP) in South Africa.

The apartheid era was characterised by a significant surge in military spending, rising from 0.90 % of GDP in 1959 to 5.3 % in 1977. This increase has been attributed to both internal and external factors, including uprisings against the apartheid regime, regional conflicts within the Southern African region, the global Cold War rivalry between superpowers, as well as international isolation and arms embargoes imposed on the country. Additionally, South Africa’s efforts to maintain military superiority within the region further fuelled the rise in military spending (Eita et al. 2022). As the end of apartheid approached, military spending declined by 2 % from 5.3 % in 1977 to 3.3 % in 1980 before the rise to 4.6 % in 1988. After 1988, the military spending as a percentage of GDP has persistently declined. The transition from apartheid to democracy in 1994 marked the beginning of a steady but further decline in military spending, as national priorities shifted towards social and economic development. Post-apartheid economic constraints or needs, reduced external threats, and growing demands for public expenditure in other sectors led to a continued reduction in military budgets.[1]

From the perspective of defence economics, a decline in military spending is generally viewed as beneficial to economic growth. Theoretically, it has been submitted that sustained increases in military expenditure can have detrimental effects on the economy. This occurs because financial resources that could otherwise be allocated to productive sectors – such as education, healthcare or infrastructure – are diverted towards strengthening military capabilities, which typically exhibit limited direct linkages to broader economic development (Benoit 1978; Brzoska 1983; Deger and Sen 1990). This notwithstanding, some defence economists argued that increased military spending could be beneficial to the economy and employment. According to these defence economists (Sandler and Hartley 1995; Smith 2010; Hartley 2011), increasing the military spending directly creates defence-related jobs among military personnel and administrative responsibilities within the military departments (Smith 2010; Hartley 2011). Michael and Stelios (2017) submitted military spending lowers unemployment rates, particularly in countries that have military equipment manufacturing companies. Dunne and Uye (2010) also argued that an increase in military spending indirectly stimulates economic growth and employment, particularly through the multiplier effect, because increased demand for military goods and services would boost production, resulting in more employment in related sectors such as manufacturing, construction and technology. Ruttan (2006) further submitted that increased military spending might stimulate research and development, with a potential spillover effect on the civilian economy and employment.

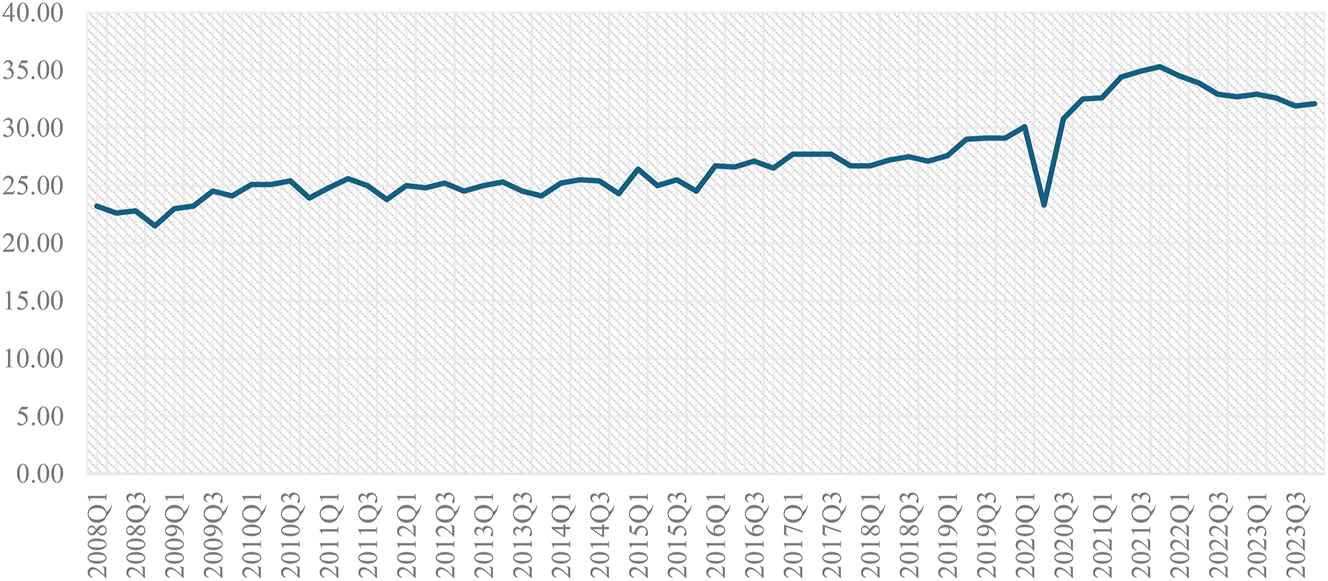

The South African government’s persistent reduction in military expenditure, aimed at reallocating resources towards pressing socioeconomic needs, has not yielded the expected improvements in key development or macroeconomic indicators. As evidenced by labour market data, the country continues to face structural unemployment despite these fiscal reallocations. Figure 2 presents unemployment rate data from 2008 to 2023, a post-apartheid period characterised by consistently reduction in military expenditure. The data reveals an upward trajectory, with unemployment rising from 23.2 % in Q1 2008 to 32.1 % by Q4 2023. This aggregate trend obscures even more severe disparities when examined through demographic lenses. Gender disaggregation shows female unemployment (34.4 % in Q4 2023) substantially exceeding male unemployment (30.1 %). Racial disparities are particularly pronounced, with unemployment rates varying dramatically across population groups: 36.1 % among Black South Africans compared to 21.7 % for Coloured citizens, 11.7 % for Asian/Indian populations and 8.5 % for White South Africans. Also, geographic analysis reveals additional disparity in unemployment among the provinces, with provincial unemployment rates ranging from 20.3 % in the Western Cape to 41.9 % in the Eastern Cape as of Q4 2023.

Total unemployment in South Africa (2008Q1-2023Q4).

In light of this, the purpose of this study is to examine the impact of military spending on unemployment in South Africa. Precisely, the study assesses the impact of military spending on unemployment across total, gender, races and provinces in South Africa is crucial for promoting inclusive and effective labour market policies. Given the country’s deep-rooted structural inequalities – persisting since apartheid, as discussed by Banerjee et al. (2008) and Heinecken (2009) – military expenditure may not have the same employment effects across different demographic groups. Research has shown that unemployment rate varies significantly by gender and races, with women and historically disadvantaged racial groups facing higher and more persistent unemployment. Furthermore, disparities in provincial unemployment levels indicate that military spending could have regionally distinct effects, shaping economic opportunities differently across provinces (Raifu and Afolabi 2023a). Understanding these variations is essential for designing policies that ensure equitable employment benefits, whether through targeted military investments or strategic reductions in military spending. A nuanced analysis can help policymakers allocate resources more effectively and address labour market disparities (Raifu et al. 2024).

Based on the foregoing analysis, the key research question is: does reduced (increased) military spending attenuate South Africa’s structural employment challenges across gender, races and provinces?

The corresponding null hypothesis goes as follows:

Reduced (increased) military spending does not reduce (worsen) unemployment across gender, races and provinces

While numerous studies have explored the relationship between military expenditure and unemployment (or employment) across various countries, including South Africa (see Malizard 2014; Azam et al. 2016; Sanso-Navarro and Vera-Cabello 2015; Qiong and Junhua 2015; Michael and Stelios 2017; Bagchi and Paul 2018; Anoruo et al. 2018; Kollias et al 2020; Lee and Park 2021; Raifu et al 2022; Raifu and Afolabi 2023a, 2023b), this study builds on the work of Raifu and Afolabi (2023a), who analysed the effect of military spending on aggregate unemployment using ARDL and NARDL estimation methods. The present study extends their research in two ways. First, rather than limiting the analysis to aggregate unemployment, it also examines the effects of military spending on unemployment across gender, racial, and provincial dimensions. This distinction is crucial, as previous studies, such as Kollias et al. (2020), have demonstrated that unemployment effect of military spending in the U.S. varies by gender and age group, while Abell (1992) investigated racial disparities in military spending’s impact on unemployment among Black and White populations in the U.S. Additionally, this study incorporates the provincial dimension of unemployment, recognising that unemployment rates differ across South African provinces. As a result, the impact of military spending on unemployment may vary between provinces with high unemployment rates and those with relatively lower levels of unemployment rates.

Second, the study investigates whether a reduction (an increase) in military spending (as shown in Figure 1) benefits (worsens) employment across gender, races, and provinces in South Africa. This analysis involves simulating the effect of a certain percentage decrease (increase) in military spending on various categories of unemployment. To achieve this, the study employs the Dynamic Autoregressive Distributed Lag (DARDL) estimation method developed by Jordan and Philips (2018). This method is used to simulate the impact of a 1 % increase or decrease in military spending on overall, gender, racial and provincial unemployment levels. By incorporating graphical visualization, the study effectively traces the dynamic effects of policy changes – such as shifts in military spending – on unemployment. This approach provides valuable insights for designing and implementing policies aimed at reducing unemployment disparities in South Africa.

After the introduction, Section 2 presents the literature review. Section 3 focuses on the methodology and data sources and Section 4 presents the empirical findings. Section 5 concludes with policy recommendations.

2 Literature Review

The relationship between military expenditure and unemployment has been extensively debated in economic research, with varying viewpoints on its effects. Some assert that military spending enhances employment, while others argue that it reallocates resources from more productive sectors, therefore worsening unemployment.

Military Keynesianism based on Keynesian economic theory posits that military expenditure can serve as an economic stimulus by augmenting aggregate demand, resulting in higher employment. Government spending in defence sectors creates employment opportunities and the resultant revenue increases consumer expenditure, further invigorating economic activity. The counter-cyclical function of military expenditure is especially evident during economic recessions, where augmented public spending helps alleviate unemployment (Dunne 2011; Cypher 2015).

In contrast, the crowding out theory emphasises possible adverse consequences. Augmented military spending, typically funded by taxation or debt, may result in higher interest rates, consequently deterring private sector investment. The allocation of capital to defence-related industries may limit job development in more labour-intensive sectors. Moreover, higher taxes diminish disposable income, undermining consumer demand and employment in consumption-oriented sectors (Ikegami and Wang 2023).

Furthermore, the sectoral shifts hypothesis propounded by Akerlof and Yellen (1985) states that military industries are capital intensive, depending more on technology and specialised skills than on extensive labour inputs. Reallocating resources from labour-intensive sectors such as manufacturing and services to defence industries may result in employment losses in the former that could counterbalance job increases in the latter. The degree of employment generation is contingent upon the economic structure and the allocation of military spending.

The idea of technological spillovers from the modern growth theory introduces an additional facet to the discourse. Military Research and Development (R&D) have traditionally facilitated civilian technical progress, exemplified by the internet and GPS, which have stimulated employment across multiple sectors. If these technologies improve productivity and generate new industries, military expenditure may indirectly promote long-term employment development (Yildirim and Öcal 2016).

Several research efforts have been made to understand the dimension of association between military expenditure and unemployment with real world data; however, these efforts have provided mixed evidence. Some studies suggest that military spending intensifies unemployment by reallocating resources away from economic industries. Qiong and Junhua (2015) discovered that higher military expenditure in China correlated with increasing unemployment, while increased non-military spending corresponded with a decrease in unemployment. Comparable results have been documented in France (Malizard 2014), the United States (Kollias et al. 2020), Nigeria (Raifu, Obijole, and Nnadozie 2022), Turkey (Yildirim and Sezgin 2003), and several Asian countries (Azam et al. 2015). Korkmaz's (2015) panel data analysis of Mediterranean economies corroborated the detrimental employment impacts of military expenditure, ascribed to the capital-intensive characteristics of the defence industry.

Conversely, other studies contend that military expenditure can alleviate unemployment by generating employment in defence-related sectors. Azam et al. (2015) discovered that military expenditure in India, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka reduced unemployment rates. Hanif et al. (2023) observed a comparable tendency in Bangladesh, wherein increased defence expenditure markedly diminished unemployment in the short term. Similarly, Raifu et al. (2022) discovered that military expenditure exerted a short-term adverse impact on unemployment in Nigeria, but job increases were noted in logistics and defence production.

Analyses unique to countries indicate that the effect of military expenditure on unemployment is contingent upon economic models and institutional contexts. Paul (1996) discovered that in 18 OECD countries, the impacts were inconsistent: military expenditure decreased unemployment in Germany and Australia, while exacerbating it in Denmark. Michael and Stelios (2017) identified negative associations in Portugal and Greece, a positive connection in Spain, and no significant long-term effect in Italy.

Some studies have addressed the issue of causality between military expenditure and unemployment. Some studies found no causal association (Sanso-Navarro and Vera-Cabello 2015), while others submitted either unidirectional or bidirectional causality, contingent upon the country. Zhong et al. (2015) discerned diverse trends among G7 countries, noting that military expenditure induced unemployment in Canada, Japan, and the United States, although a bidirectional relationship was seen in Italy and the United Kingdom. Raifu and Afolabi (2023b) discovered that in the United States, causality patterns varied according on the estimation method employed; the Toda-Yamamoto test indicated unidirectional causation, while time-varying analysis suggested bidirectional causality. Notwithstanding comprehensive investigation, major deficiencies persist. Most studies concentrate on overall unemployment without accounting for demographic differentiation.

This study builds upon Kollias et al. (2020) by investigating the varying impacts of military expenditure on unemployment, differentiated by gender, races and provinces in South Africa, a dimension that has been generally neglected. Furthermore, although Raifu and Afolabi (2023a) investigated the symmetric and asymmetric effects of military expenditure on total unemployment in South Africa, no research in the country has assessed its dynamic influence through simulation models. Utilising a dynamic ARDL paradigm, our study seeks to address this gap by examining the impact of fluctuations in military expenditure on long-term employment outcomes, thereby providing pertinent policy insights.

3 Methodology and Data Sources

The purpose of this study is to answer a simple research question using a combination of estimation techniques. The research question is: Does a decline or increase in military spending favour (or disfavour) job creation in South Africa? We examine this research question by taking into account various categories of unemployment data, including total, gender, province, and race data. To answer the research questions, the study begins by using the Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) estimation method. This is followed by Dynamic Autoregressive Distributed Lag (DARDL) and Kernel Recursive Least Squares (KRLS). We use the ARDL as a baseline estimation to investigate the short- and long-term impacts of military spending on unemployment, the DARDL to model the impact of a 1 % (of GDP) increase or decrease in military spending on unemployment and the KRLS, a machine learning algorithm, to investigate the causal relationship between military spending and unemployment.

Following Pesaran et al. (2001), the baseline model of ARDL (p, q) is specified as follows:

Where y t is a dependent variable at time t. x t denotes a set of independent variables which contains the main independent variables and other control variables. φ i is autoregressive (AR) coefficient for lagged y t , β j is the distributed lag (DL) coefficients for x t , ε t is white noise error term. Following existing studies (Raifu and Afolabi 2023a Malizard 2014; Azam et al. 2016), we respecify equation (1) as an unemployment equation where unemployment depends on the lagged unemployment, military spending, nonmilitary spending and other control variables

Where UN represents various types of unemployment. In this study, we consider total unemployment, gender unemployment, racial unemployment and provincial unemployment. This is considered to examine how military spending affects different categories of unemployment in South Africa. This approach could be useful for policy formulation geared towards addressing the issue of unemployment in the country. UN t−1 is the lagged unemployment which shows the time persistence of unemployment. In other words, past unemployment influences present unemployment – if unemployment was high in the past, it is likely to remain high in the present. MS denotes military spending expressed as a percentage of GDP. NMS is non-military spending expressed as a percentage of GDP. X ′ s are other control variables that serve as determinants of unemployment; they include GDP growth rate, foreign direct inflows (% of GDP), and inflation rate. Given this, equation (2) is re-specified as follows:

In equation (3) β 0 represents a constant which shows the unemployment rate without accounting for the effects of military spending, nonmilitary spending and the control variables. β 1, β 2, β 3, β 4, β 5 and β 6 are the coefficient parameters which show the effects of lagged unemployment, military spending, nonmilitary spending, GDP growth rate, foreign direct investment and inflation rate on unemployment in the long run respectively. ε t is an error term assumed to be normally distributed with zero mean and constant variance. It is a white noise that captures other factors held constant that could have affected unemployment. Based on the theoretical arguments mentioned above, military spending could have either a positive or negative effect on unemployment. Nondefense spending, particularly health, education and infrastructure spending, is usually considered a productive expenditure that, if properly channelled, can spur economic growth and thereby reduce unemployment (Badmus et al. 2024). As a result, we expect nondefense spending to have a negative effect on unemployment, i.e. reducing unemployment. With regard to the effect of economic growth on unemployment, Okun’s law postulates that there is an inverse relationship between economic growth and unemployment (Raifu and Afolabi 2023a, 2023b). This means an increase in economic growth should a priori reduce unemployment; hence, we expect a negative effect of the economic growth rate on unemployment. According to the Phillips curve theory, there is also an inverse relationship between the unemployment rate and the inflation rate (Phillips 1958). Thus, the effect of inflation on unemployment should be negative. In the case of the relationship between FDI and unemployment, we expect a negative relationship. This is because FDI inflows lead to the establishment of firms or companies that employ the citizens of the host countries, thereby reducing the unemployment rate.

For the ARDL implementation, we first extracted the long-run coefficients from equation (1), then specified the complete ARDL model based on equation (3). From equation (1), the long-run equation is usually obtained by dividing the sum of the estimated coefficients of the independent variables by the coefficient of lagged dependent variables. We begin by normalizing the coefficients of the steady state relationship in equation (1) which yields the following equation.

Using equations (1) and (4), the long-run coefficient is derived as follows.

Where θ denotes the long-run multiplier of military spending (and others) on unemployment.

To specify the full ARDL model, we follow religiously the procedures for implementing the ARDL method in STATA by Sarkodie and Owusu (2020). According to Sarkodie and Owusu (2020), the first step in the procedures is to conduct the unit root test, aimed at determining the stationarity properties of the variables we used in this study. We used the Phillips-Perron (Phillips and Perron 1988) and the KPSS unit root tests (Kwiatkowski et al. 1992). While PP assumes that the variables contain a unit root, KPSS assumes that variables do not. Another important step is to determine whether the variables combined in a model are cointegrated, that is, have a long-run relationship even though they may experience short-term disequilibrium or fluctuations. This study uses the ARDL bounds testing approach to ascertain the cointegration among the variables. We utilise the crucial value established by Kripfganz and Schneider (2020), which derives its p-value from response surface regression. The KS critical value has been determined to outperform the methodologies of Pesaran et al. (2001) and Narayan and Narayan (2005) as well as Narayan (2005) in making statistical inferences concerning cointegration (Kripfganz and Schneider 2023). According to the prior research by Raifu, Aminu, and Folawewo (2020), determining cointegration requires the computation of an unconstrained error correction model, specified as follows from equation (2).

From equation (6), Δ is a difference operator. β 0 denotes a constant representing the drift components of equation (3). β i (i = 1,…,6) denotes the long-run effect multipliers which depict the effect of each independent variable on unemployment in the long run. α i = (1,…,6) represents the short-run multiplier effect, showing the effect of each independent variable on unemployment in the short run. The maximum lag length is selected using the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). The selected lag length varies across the models, but it ranges from 2 to 4 lag lengths. After the estimation, we tested the null hypothesis of no long-run relationship in equation (6). The null hypothesis is specified as follows: θ:β 1 = β 2 = β 3 = β 4 = β 5 = β 6 = 0 and it is tested against the alternative hypothesis specified as follows: θ:β 1 ≠ β 2 ≠ β 3 ≠ β 4 ≠ β 5 ≠ β 6 ≠ 0. An F-statistic test based on Kripfganz and Schneider’s (2020) critical value was used to determine the existence of cointegration.

The short-run error correction model, which captures the adjustment from short-run disequilibrium to long-run equilibrium, is derived from equation (5) and specified as follows.

Where ϑ is the coefficient of the error correction term (ect), showing the speed of adjustment from the short-term disequilibrium towards the long-term equilibrium. On a priori, it is expected to be negative, less than one and statistically significant.

In line with recommendations by Sarkodie and Owusu (2020), we conducted some diagnostic tests to test the reliability of our ARDL model. This is important before applying the dynamic ARDL. The diagnostic tests include the Breusch-Pagan/Cook-Weisberg test for heteroskedasticity, White’s test for heteroscedasticity, the Breusch-Godfrey LM test for autocorrelation, Durbin’s alternative test for autocorrelation, skewness and kurtosis for normality and the CUSUM test for model stability.

The main goal of this study is to simulate the effect of a one percent increase or decrease in military spending on unemployment. In other words, we address a central question: whether an increase or a decrease in military spending is pro or anti-job provision in South Africa. To answer this question, we used DARDL, which was created by Jordan and Phillips (2018). The method enables us to test the effects of counterfactual changes in military spending on unemployment through graphical visualisation of dynamics of change in unemployment over some time horizons (Dimitraki and Emmanouilidis 2023).

Finally, we employed Kernel Recursive Least Squares (KRLS), a machine learning algorithm, to examine the causal-effect relationships between military spending and unemployment in South Africa. This KRLS offers some advantages over the Ordinary Least Squares Regression method. For instance, KRLS provides closed-form estimates for predicted values, variances, and partial derivatives, which offer insight into the marginal effects of one variable on another variable without having to rely on OLS assumptions such as additive or linearity assumptions. Apart from this, KRLS also provides a flexible alternative to ordinary least squares, accommodating nonlinearities, interactions, and heterogeneous effects (Raifu et al. 2024). Furthermore, it gives pointwise marginal effects and variances for each data point, ensuring unbiasedness, consistency, and asymptotic normality under general conditions (Ferwerda et al. 2017). As a result, the KRLS method is useful in determining the marginal impact of military spending on unemployment, allowing for some distribution effects across different percentiles.

Having established the justification for employing KRLS, we now present its mathematical framework. As previously stated, KRLS extends ordinary least squares (OLS) or generalized linear models (GLM) by integrating kernel methods to model nonlinear relationships while mitigating overfitting. Following Hainmueller and Hazlett (2014), we formalise the core optimization problem of KRLS as follows.

Where K represents the kernel matrix, defined as K ij = K(x i ,x j ) for a chosen kernel function K(x,x ′), α is the vector of coefficients, Y denotes response vector and λ is the regularisation parameter to prevent overfitting. If the closed-form solution is used. KRLS estimates α can be obtained as follows:

The final predicted function can be specified as:

Where the kernel function K(x,x i ) is a Gaussian (RBF) polynomial. It can also be any types of Gaussians which is allowed to capture complex nonlinear patterns in the data.

All the other variables used except unemployment, military spending and nonmilitary spending are selected from the Reserve Bank of South Africa, and they are quarterly data from 2008 Q1 to 2023 Q4. While military spending (% of GDP) is obtained from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (2023) database, unemployment and nonmilitary spending data are extracted from the Statistics South Africa (https://www.statssa.gov.za/) and World Development Indicators (WDI). We converted the annual military spending and nonmilitary spending data to quarterly data using a quadratic approach in EVIEW 10. All variables are naturally logged except the inflation rate.

4 Empirical Findings

4.1 Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 presents a descriptive analysis of the unemployment rate across gender, race, province and other variables including military spending (% of GDP) in South Africa. During the period of analysis, the average unemployment rate in South Africa was 27 %. The gender unemployment rate showed that female unemployment rate was higher than that of male. While the female unemployment rate, on average, stood at 29 %, the male unemployment rate stood at 25 %. Among the races, the black unemployment rate in South Africa was the highest, with an average of 31 %, a maximum of 39 %, and a minimum rate of 25 %. This was followed by coloured and Asian/Indian unemployment rates, which averaged 23 and 13 % respectively. The unemployment rate was lowest among the white people with an average of 7 %. With regard to provinces, unemployment was more prevalent among the people of Eastern Cape Province. In this province, the unemployment rate averaged 33 %. This province was followed by Mpumalanga province with an average unemployment rate of 30 % and Northwest and Gauteng provinces with each having unemployment rates of 28 %. The Western Cape Province has the lowest unemployment rate with an average unemployment rate of 22 %.

Descriptive statistics.

| Variable | Obs | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total unemployment | |||||

|

|

|||||

| Total unemployment | 64 | 27.206 | 3.61 | 21.5 | 35.3 |

|

|

|||||

| Unemployment by race | |||||

|

|

|||||

| Black unemployment | 64 | 30.852 | 3.755 | 25.4 | 39.1 |

| Coloured unemployment | 64 | 23.166 | 2.369 | 17.6 | 30.3 |

| Asians/Indians unemployment | 64 | 12.605 | 3.153 | 7.7 | 27.5 |

| White unemployment | 64 | 6.788 | 1.365 | 3 | 10 |

|

|

|||||

| Unemployment by provinces | |||||

|

|

|||||

| Western Cape unemployment | 64 | 21.608 | 2.249 | 16.4 | 28 |

| Eastern Cape unemployment | 64 | 33.211 | 6.637 | 24.2 | 47.9 |

| Northern Cape unemployment | 64 | 27.436 | 2.859 | 21.2 | 34.8 |

| Free state unemployment | 64 | 31.9 | 4.042 | 22 | 38.5 |

| KwaZulu Natal unemployment | 64 | 23.767 | 4.276 | 18.3 | 33.2 |

| Northwest unemployment | 64 | 28.403 | 4.304 | 21.6 | 39 |

| Gauteng unemployment | 64 | 28.553 | 4.154 | 20.4 | 37 |

| Mpumalanga unemployment | 64 | 30.252 | 4.618 | 13.3 | 39.7 |

| Limpopo unemployment | 64 | 23.337 | 5.605 | 15.9 | 36.3 |

|

|

|||||

| Unemployment by gender | |||||

|

|

|||||

| Female unemployment | 64 | 29.483 | 3.556 | 24.8 | 38.2 |

| Male unemployment | 64 | 25.334 | 3.671 | 18.8 | 33 |

|

|

|||||

| Other variables | |||||

|

|

|||||

| Military spending (% of GDP) | 64 | 0.950 | 0.103 | 0.72 | 1.10 |

| Non-military spending (% of GDP) | 64 | 29.12 | 2.194 | 24.24 | 33.85 |

| GDP growth rate | 64 | 4,330,377.1 | 259,839.87 | 3,815,385 | 4,650,164 |

| FDI (% of GDP) | 64 | 0.471 | 1.142 | −0.322 | 9.059 |

| Inflation rate | 64 | 4.392 | 5.615 | −17.391 | 12.139 |

-

Authors’ Computation.

Military spending and non-military spending (as a percentage of GDP) averaged 0.95 and 29 % respectively. Other variables, such as real GDP, FDI (% of GDP), and inflation, had averages of 4,330,377.1 Rand, 0.5 and 4 % respectively.

4.2 Unit Root Test Results

Stationarity tests are critical in determining and applying an appropriate estimation method in time series analysis as well as guiding against potential spurious regression. Thus, we conducted stationarity tests using both the Phillip Perron (PP) and the Kwiatkowski, Phillips, Schmidt, and Shin (KPSS) unit roots tests. For PP, the null hypothesis is that the variable has a unit root, whereas for KPSS, the null hypothesis is stationarity. For an estimation with an ARDL model, it is expected that all independent variables must be either integrated of order zero I(0) or order one I(1). Table 2 displays the unit root test results. Based on PP unit root test results, we reject the null hypothesis of unit roots for some variables at the first difference, however, for some variables, we could not reject the null hypothesis at level. Similarly, the null hypothesis of stationarity is rejected for some variables at levels and not rejected at first difference under the KPSS. This means that the variables are integrated of mixed orders. Hence, we can use the ARDL estimation method since all the variables are either I(0) and I(1).

Unit root tests.

| Variables | PP | KPSS | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level | Fist difference | Level | Fist difference | |||||

| t-Statistic | Prob. | t-Statistic | Prob. | t-Statistic | Prob. | t-Statistic | Prob. | |

| Total unemployment | −1.319 | 0.6157 | −14.889*** | 0.0000 | 0.9020 | *** | 0.1153 | no |

| Black unemployment | −1.388 | 0.5827 | −15.268*** | 0.0000 | 0.8555 | *** | 0.1700 | no |

| Coloured unemployment | −3.061** | 0.0348 | −9.4756*** | 0.0000 | 0.4569 | * | 0.1619 | no |

| Asians/Indian unemployment | −3.098** | 0.0318 | −11.328*** | 0.0000 | 0.6233 | ** | 0.0953 | no |

| White unemployment | −2.293 | 0.1774 | −14.180*** | 0.0000 | 0.8454 | *** | 0.0398 | no |

| Western Cape unemployment | −3.319** | 0.0181 | −10.126*** | 0.0000 | 0.2060 | no | 0.1885 | no |

| Eastern Cape unemployment | −0.737 | 0.8293 | −10.575*** | 0.0000 | 0.8893 | *** | 0.1164 | no |

| Northern Cape unemployment | −4.758*** | 0.0002 | −28.068*** | 0.0001 | 0.2602 | no | 0.3128 | no |

| Free state unemployment | −2.84* | 0.0586 | −20.804*** | 0.0001 | 0.8311 | *** | 0.3858 | * |

| KwaZulu Natal unemployment | −1.915 | 0.3237 | −14.667*** | 0.0000 | 0.8620 | *** | 0.1761 | no |

| Northwest unemployment | −2.656* | 0.0875 | −16.706*** | 0.0000 | 0.8556 | *** | 0.1406 | no |

| Gauteng unemployment | −1.495 | 0.5297 | −11.108*** | 0.0000 | 0.8977 | *** | 0.0627 | no |

| Mpumalanga unemployment | −4.208*** | 0.0014 | −24.771*** | 0.0001 | 0.7866 | *** | 0.2573 | no |

| Limpopo unemployment | −1.618 | 0.4677 | −10.708*** | 0.0000 | 0.3321 | no | 0.3995 | * |

| Female unemployment | −1.493 | 0.5305 | −14.120*** | 0.0000 | 0.8724 | *** | 0.0997 | no |

| Male unemployment | −1.477 | 0.5387 | −14.485*** | 0.0000 | 0.9163 | *** | 0.2560 | no |

| Military spending (% of GDP) | 0.3895 | 0.9810 | −4.584*** | 0.0004 | 0.8749 | *** | 0.2167 | no |

| Nonmilitary spending (% of GDP) | −2.2 | 0.2083 | −4.170*** | 0.0016 | 0.9479 | *** | 0.1406 | no |

| GDP growth rate | −1.866 | 0.3460 | −16.763*** | 0.0000 | 0.8651 | *** | 0.1632 | no |

| FDI (% of GDP) | −8.251*** | 0.0000 | −61.078*** | 0.0001 | 0.1660 | no | 0.1821 | no |

| Inflation rate | −3.182* | 0.0257 | −7.289*** | 0.0000 | 0.0978 | no | 0.0549 | no |

-

Authors’ Computation. a, (*) significant at the 10 %; (**) significant at the 5 %; (***) significant at the 1 % and (no) not significant. b, lag length based on AIC. c, probability based on MacKinnon (1994) one-sided p-values.

4.3 Bounds Testing Results

A criterion for establishing a long-run relationship is the existence of a cointegration relationship among the underlying variables in a model. For an ARDL analysis, the underlying variables must be of mixed orders of integration, i.e. I(0) and I(1) (Moawad 2019). Furthermore, the null hypothesis of no cointegration or cointegration is rejected or accepted, if the value of the calculated F-statistics of the ARDL bound test is higher or lower than the upper or lower critical bounds value, and inconclusive if the critical value falls in between the I(1) and I(0) values at 5 % significance level (Qamruzzaman and Wei 2018). Table 3 below presents the results of the bound tests of the various unemployment models. All the models, except for the Eastern Cape unemployment rate under the province unemployment category, demonstrate cointegration and exhibit long-term relationships. Hence, there is a need to show the estimated short and long coefficients of the variables in the models using the ARDL. The test statistic for the Eastern Cape unemployment rate model lies between the I(0) and I(1) critical value bounds, so it is interpreted as inconclusive at the 5 % significance level. These results and the subsequent ARDL results are based on the lag structure of the ARDL in Table 3 below which are generated automatically.

ARDL bounds testing results.

| Variables | F-Statistics (5 % Significance level) | Decision | Lag length | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Critical value | I(0) | I(1) | ||||

| Total unemployment | Total unemployment | 8.332 | 2.830 | 4.154 | Cointegrated | ARDL(1,0,2,1,0,0) |

| Gender unemployment | Female unemployment | 9.266 | 2.806 | 4.181 | Cointegrated | ARDL(2,0,2,2,1,0) |

| Male unemployment | 8.566 | 2.845 | 4.135 | Cointegrated | ARDL(1,0,0,1,0,0) | |

| Race unemployment | Black unemployment | 6.436 | 2.845 | 4.135 | Cointegrated | ARDL(1,0,0,1,0,0) |

| White unemployment | 13.895 | 2.837 | 4.145 | Cointegrated | ARDL(1,0,0,0,2,0) | |

| Coloured unemployment | 6.574 | 2.806 | 4.181 | Cointegrated | ARDL(1,0,2,1,3,0) | |

| Asia/India unemployment | 9.693 | 2.814 | 4.172 | Cointegrated | ARDL(1,0,0,4,1,0) | |

| Province unemployment | Western Cape unemployment | 7.658 | 2.806 | 4.181 | Cointegrated | ARDL(1,0,2,1,3,0) |

| Eastern Cape unemployment | 3.053 | 2.845 | 4.135 | Inconclusive | ARDL(1,0,0,1,0,0) | |

| Northern Cape unemployment | 10.235 | 2.853 | 4.126 | Cointegrated | ARDL(1,0,0,0,0,0) | |

| Free state unemployment | 7.135 | 2.830 | 4.154 | Cointegrated | ARDL(1,0,0,1,2,0) | |

| KwaZulu Natal unemployment | 5.037 | 2.830 | 4.154 | Cointegrated | ARDL(1,0,2,1,0,0) | |

| Northwest unemployment | 5.379 | 2.814 | 4.172 | Cointegrated | ARDL(1,0,1,2,2,0) | |

| Gauteng unemployment | 6.157 | 2.845 | 4.135 | Cointegrated | ARDL(1,0,0,1,0,0) | |

| Mpumalanga unemployment | 7.103 | 2.837 | 4.145 | Cointegrated | ARDL(2,0,0,1,0,0) | |

| Limpopo unemployment | 7.348 | 2.806 | 4.181 | Cointegrated | ARDL(2,0,0,1,0,0) | |

-

Authors’ Compilation/Computation.

4.4 Main Results

The analysis of the unemployment effects of military spending in South Africa was carried out using three methods, the ARDL, DARDL and KRLS.

4.4.1 ARDL Results

Tables 4 and 5 present both the short and long term ARDL results. Military spending exerts negative and statistically significant impacts on total and gender unemployment, both in the short run and the long run periods, suggesting that an increase in military spending would lead to a reduction in total, male and female unemployment rates. When Race unemployment rates are considered, increased military spending reduced significantly the black unemployment Rate in the short and long run, but pushed up significantly the rate of unemployment among the Coloured Race in both periods. Similar positive relationships were also obtained among the White and Asian/Indian populations, but only in the short run. The negative impact of military spending on the Black Race unemployment rate could be attributed to the Assertive Affirmative action (AA) and Equal Opportunities (EO) programme[2] of the African National Congress (ANC) after its election in 1994 which abolished the hitherto racial, ethnic and gender segregation in the South African armed forces thereby increasing the population of the Black race in the South African Defence Force (SANDF) to about 70 %, (Heinecken and Van der Waag-Cowling 2013; Heinecken 2009). Therefore, increased budgetary expenditure for the South African military, especially for recruitment purposes, negatively affected the rate of unemployment in the Black Race while increasing that of others.

Unemployment effects of military spending in South Africa: Short run result.

| Variable | lmil_gdp | lnms_gdp | lgdpr | fdi_gdp | Infl | ECT | Adj. R squared |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total unemployment | |||||||

|

|

|||||||

| Total unemployment | −0.267*** | 1.009*** | 0.949*** | 0.007** | 0.001* | −0.558*** | 0.79 |

|

|

|||||||

| (0.084) | (0.355) | (0.170) | (0.003) | (0.000) | (0.094) | ||

|

|

|||||||

| Gender unemployment | |||||||

|

|

|||||||

| Women unemployment | −0.291*** | 1.201*** | 0.958*** | 0.009*** | 0.001 | −0.669*** | 0.83 |

| (0.103) | (0.337) | (0.176) | (0.003) | (0.001) | (0.120) | ||

| Men unemployment | −0.267*** | 0.559*** | 1.240*** | 0.009** | 0.001 | −0.500*** | 0.74 |

|

|

|||||||

| (0.090) | (0.107) | (0.156) | (0.004) | (0.001) | (0.088) | ||

|

|

|||||||

| Race unemployment | |||||||

|

|

|||||||

| Black unemployment | −0.285*** | 0.430*** | 1.183*** | 0.007* | 0.001 | −0.482*** | 0.75 |

| (0.097) | (0.094) | (0.155) | (0.003) | (0.001) | (0.097) | ||

| White unemployment | 0.237 | 0.977*** | 1.823*** | 0.023** | −0.005* | −0.874*** | 0.57 |

| (0.188) | (0.291) | (0.386) | (0.011) | (0.002) | (0.098) | ||

| Coloured unemployment | 0.309*** | 0.507 | 0.777*** | 0.018*** | −0.005 | −0.525*** | 0.62 |

| (0.107) | (0.581) | (0.254) | (0.005) | (0.001) | (0.099) | ||

| Asia/India unemployment | 0.394 | 2.238*** | 0.800 | 0.035** | 0.01*** | −0.729*** | 0.56 |

|

|

|||||||

| (0.244) | (0.484) | (0.597) | (0.014) | (0.003) | (0.104) | ||

|

|

|||||||

| Province unemployment | |||||||

|

|

|||||||

| Western Cape unemployment | 0.176 | 0.075 | 0.785*** | 0.015*** | 0.002 | −0.497*** | 0.62 |

| (0.109) | (0.635) | (0.279) | (0.006) | (0.001) | (0.085) | ||

| Eastern Cape unemployment | −0.103 | 0.801*** | 0.76*** | 0.007 | 0.002 | −0.339*** | 0.31 |

| (0.113) | (0.221) | (0.234) | (0.006) | (0.001) | (0.096) | ||

| Northern Cape unemployment | 0.462** | −0.395 | 0.932*** | −0.004 | 0.001 | −0.930*** | 0.48 |

| (0.177) | (0.238) | (0.325) | (0.009) | (0.002) | (0.124) | ||

| Free state unemployment | 0.048 | 0.182 | 2.056*** | 0.015** | 0.001 | −0.664*** | 0.71 |

| (0.112) | (0.154) | (0.246) | (0.006) | (0.001) | (0.114) | ||

| Kwazulu Natal unemployment | −0.236 | 2.052*** | 1.215*** | −0.01 | 0.002 | −0.461*** | 0.65 |

| (0.156) | (0.726) | (0.338) | (0.007) | (0.002) | (0.111) | ||

| North West unemployment | −0.804*** | 2.225*** | 1.624*** | 0.005 | 0.004* | −0.613*** | 0.62 |

| (0.198) | (0.757) | (0.377) | (0.008) | (0.002) | (0.129) | ||

| Gauteng unemployment | −0.200** | 0.512*** | 1.05*** | 0.008* | −0.001 | −0.436*** | 0.58 |

| (0.099) | (0.122) | (0.182) | (0.004) | (0.001) | (0.090) | ||

| Mpumalanga unemployment | −0.534*** | −0.377* | 4.056*** | 016** | 0.001 | −0.600*** | 0.90 |

| (0.153) | (0.194) | (0.300) | (0.006) | (0.001) | (0.108) | ||

| Limpopo unemployment | 0.288 | 1.514*** | −0.216 | −0.02* | 0.001 | −0.419*** | 0.45 |

| (0.624) | (0.289) | (0.474) | (0.012) | (0.003) | (0.103) | ||

-

Standard errors are in brackets; ***p < 0.01, **p < 0<.05, *p < 0.1.

Unemployment effects of military spending in South Africa: long run result.

| Variable | lmil_gdp | lnms_gdp | lgdpr | fdi_gdp | Infl |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total unemployment | |||||

|

|

|||||

| Total unemployment | −0.478*** | −0.478*** | −0.374*** | 0.012*** | 0.002 |

| (0.107) | (0.182) | (0.208) | (0.006) | (0.001) | |

|

|

|||||

| Gender unemployment | |||||

|

|

|||||

| Women unemployment | −0.434*** | 0.996*** | −0.265 | 0.025*** | 0.001 |

| (0.099) | (0.170) | (0.161) | (0.007) | (0.001) | |

| Men unemployment | −0.535*** | 1.120*** | −0.31 | 0.017** | 0.002 |

| (0.130) | (0.210) | (0.260) | (0.007) | (0.002) | |

|

|

|||||

| Race unemployment | |||||

|

|

|||||

| Black unemployment | −0.591*** | 0.892*** | −0.436* | 0.014* | 0.001 |

| (0.129) | (0.213) | (0.244) | (0.007) | (0.001) | |

| White unemployment | 0.271 | 1.118*** | 2.086*** | 0.073*** | −0.005* |

| (0.216) | (0.305) | (−0.376) | (0.023) | (0.003) | |

| Coloured unemployment | 0.589*** | 0.864*** | 0.174 | 0.082*** | 0.002 |

| (0.192) | (0.296) | (0.377) | (0.022) | (0.002) | |

| Asia/India unemployment | 0.540 | 3.069*** | −0.719 | 0.13*** | 0.014*** |

| (0.348) | (0.612) | (0.651) | (0.028) | (0.004) | |

|

|

|||||

| Province unemployment | |||||

|

|

|||||

| Western Cape unemployment | 0.354 | 0.574* | −0.576 | 0.109*** | 0.004 |

| (0.219) | (0.333) | (0.431) | (0.025) | (0.003) | |

| Eastern Cape unemployment | −0.304 | 2.363*** | −0.383 | 0.02 | 0.006 |

| (0.298) | (0.460) | (0.561) | (0.017) | (0.004) | |

| Northern Cape unemployment | 0.497*** | −0.425 | 1.002*** | −0.004 | 0.001 |

| (0.172) | (0.255) | (0.31) | (0.010) | (0.0020 | |

| Free state unemployment | 0.072 | 0.275 | 1.461*** | −0.003 | 0.001 |

| (0.165) | (0.228) | (0.317) | (0.019) | (0.002) | |

| Kwazulu Natal unemployment | −0.513* | 1.755*** | −0.173 | −0.021 | 0.005 |

| (0.275) | (0.487) | (0.501) | (0.016) | (0.003) | |

| North West unemployment | −1.312*** | 0.567* | −1.271*** | −0.037 | 0.006* |

| (0.240) | (0.337) | (0.448) | (0.027) | (0.003) | |

| Gauteng unemployment | −0.459** | 1.172*** | −0.168 | 0.019* | −0.002 |

| (0.180) | (0.289) | (0.352) | (0.011) | (0.002) | |

| Mpumalanga unemployment | −0.891*** | −0.628** | 0.662* | 0.027** | 0.001 |

| (0.178) | (0.276) | (0.352) | (0.011) | (0.002) | |

| Limpopo unemployment | −1.02** | 3.615*** | −4.817*** | −0.049 | 0.027*** |

| (0.499) | (0.948) | (0.796) | (0.03) | (0.008) | |

-

Standard errors are in brackets; ***p < 0<0.01, **p < 0<0.05, *p < 0.1.

Among the provinces, increased military spending caused significant reductions in North West, Gauteng, and Mpumalanga unemployment rates, both in the short run and the long run and also in the Kwazulu Natal province unemployment rate in the long run only. There was also a negative, but insignificant, relationship between military spending and the Eastern Cape Province unemployment rate. These provinces are dominated by Black South Africans whose employment in the SANDF increased to about 70 % after the AA and EO policies (Heinecken and Van der Waag-Cowling 2013; Heinecken 2009). The results show that unemployment rates in Black dominated Provinces reduced. The implication of the negative coefficients of military spending on unemployment rates is that an increase in military spending leads to a reduction in the rates of unemployment. Yildirim and Sezgin (2003) find a similar outcome for Turkey. They argue that military spending increases employment or reduces unemployment when military-related operations allow the employment of vast numbers of workers either directly or indirectly through ancillary or supporting roles. On the contrary, increased military spending positively affected unemployment rates in the provinces of Western Cape, Northern Cape, and Free State in both the short and long run, and the Limpopo Province only in the short run. Only the relationship with the unemployment rate in the Northern Cape Province was significant, at 5 % in the short run and 1 % in the long run. These provinces, comprising mostly the coloured, India/Asian and White Races, experienced a dramatic drop in the SANDF, after the AA and EO programme which abolished their pre-SANDF favour in military recruitments (Heinecken and Van der Waag-Cowling 2013). Generally, this result showed that military spending has heterogeneous effects on unemployment rate among the races and provinces in South Africa. In other words, military spending impacts unemployment rates differently in the different Races and provinces that make up South Africa.

The results of the relations between total, gender, Race and provincial unemployment rates and the control variables are also presented in Tables 4 and 5. The result shows that non-military spending, real GDP, and FDI positively impacted significantly on total, women, men, black, White, Coloured, Asian/Indian, Eastern Cape, Kwazulu Natal, North West, Gauteng and Limpopo unemployment rates. In other words, increases in non-military spending, real GDP, and FDI increased significantly the rate of unemployment in total, women and men, black, White, Coloured and Asian/Indian, Eastern Cape, Kwazulu Natal, North West, Gauteng and Limpopo populations in both the short and long periods. The results show that while military spending reduces unemployment rates, the reverse is the case for non-military spending.

The results of the error correction model for all the models are presented in the Appendix. The results showed that the range of correction for the disequilibrium between the variables considered in the models is between 41.9 and 91.0 %. This suggests that in the long run, the speeds of adjustments or convergences towards equilibrium are rather rapid. The adjusted R2 of the different models are on the average high. Apart from Eastern Cape and Limpopo provinces models, which are 31 and 45 %, others are above 50 %, suggesting high interpretation powers of the variables that make up each model.

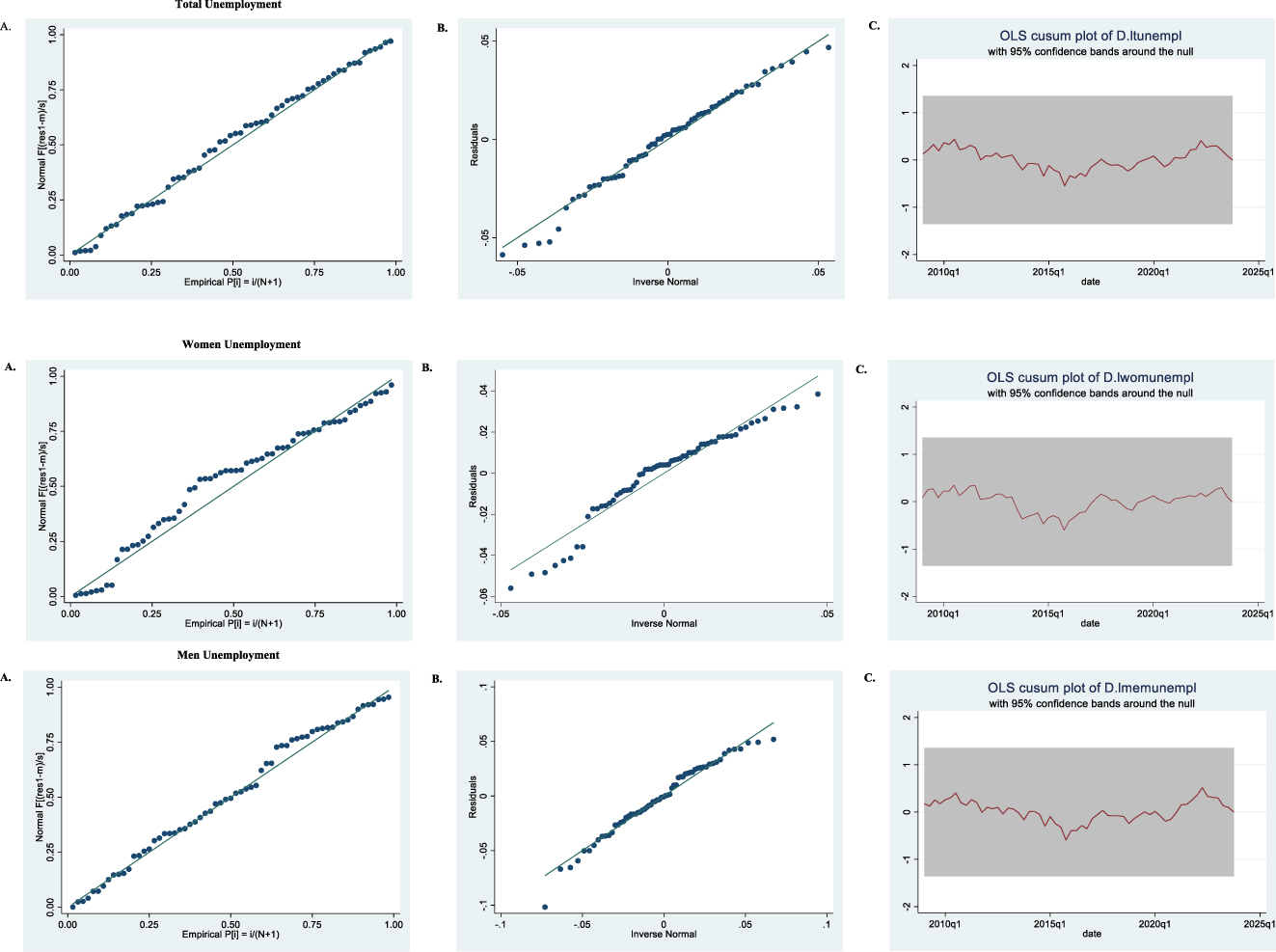

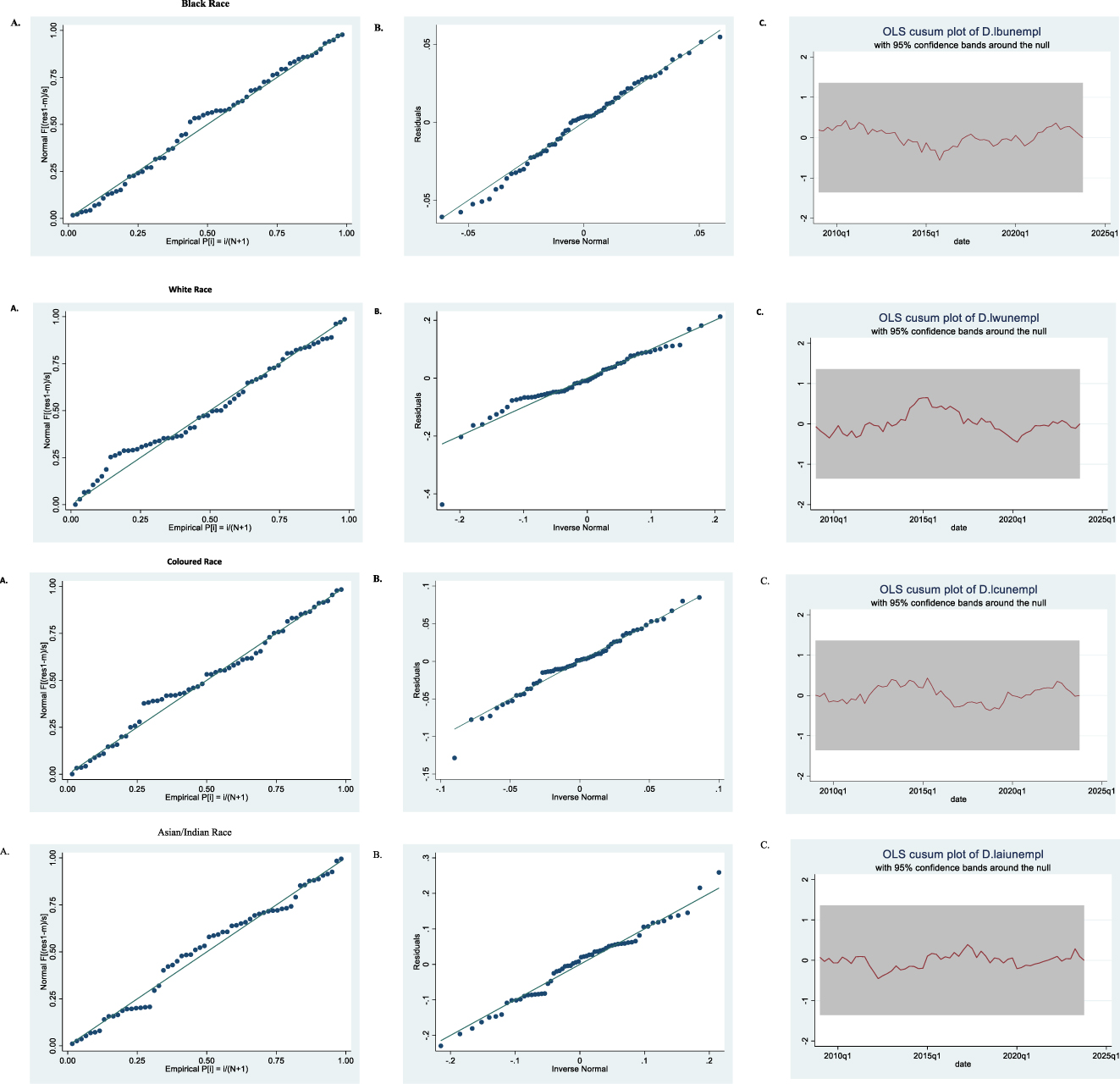

4.4.2 Diagnostic Test

The validity of the ARDL results is examined using different diagnostic tests. We conducted the Breusch-Pagan/Cook-Weisberg Heteroskedasticity test, Breusch-Godfrey LM Autocorrelation test, Durbin’s alternative Autocorrelation test, White Heteroscedasticity test, Cameron & Trivedi’s Decomposition IM-test, Skewness and Kurtosis Normality tests, as well as the Cumulative Sum test for parameter stability using OLS CUSUM plot. The results presented in Table 6 show the absence of heteroskedasticity (see Columns 2 & 5) and autocorrelation (see Columns 3 & 4). The table shows that, at a probability of 5 %, all models reject the null hypothesis of heteroskedasticity, and autocorrelation, except for the total unemployment rate model and the Black race unemployment models. The study also addressed the potential problem of heteroskedasticity by applying natural logarithms to the variables. Cameron & Trivedi’s decomposition of the IM-test in column 6 also failed to reject the null hypothesis of homoskedasticity at the 5 % significance level. This suggests that the residuals of the different models are homoskedastic.

Diagnostics tests.

| Variable | Heteroskedasticity: Breusch–Pagan/Cook–Weisberg test | Autocorrelation: Breusch–Godfrey LM test | Autocorrelation: Durbin’s alternative test | White heteroskedacticiy test | Decomposition: Cameron & Trivedi’s IM-test | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F-stat. | Prob. | F-stat. | Prob. | F-stat. | Prob. | F-stat. | Prob. | F-stat. | Prob. | |

| Total unemployment | 0.01 | 0.93 | 5.10 | 0.03 | 4.56 | 0.04 | 55.96 | 0.40 | 63.18 | 0.51 |

|

|

||||||||||

| Gender unemployment | ||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

| Female unemployment | 0.00 | 0.96 | 0.01 | 0.92 | 0.01 | 0.93 | 60.00 | 0.44 | 79.89 | 0.25 |

| Male unemployment | 0.09 | 0.76 | 3.00 | 0.09 | 2.68 | 0.11 | 30.80 | 0.67 | 38.87 | 0.65 |

|

|

||||||||||

| Race unemployment | ||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

| Black unemployment | 0.38 | 0.54 | 6.25 | 0.02 | 5.93 | 0.02 | 31.51 | 0.64 | 41.33 | 0.54 |

| White unemployment | 0.00 | 0.99 | 0.39 | 0.53 | 0.33 | 0.57 | 44.79 | 0.44 | 49.04 | 0.63 |

| Coloured unemployment | 0.22 | 0.64 | 1.52 | 0.22 | 1.19 | 0.28 | 60.00 | 0.44 | 73.72 | 0.42 |

| Asia/India unemployment | 1.25 | 0.26 | 1.52 | 0.22 | 1.22 | 0.28 | 60.00 | 0.44 | 63.50 | 0.72 |

|

|

||||||||||

| Province unemployment | ||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

| Western Cape unemployment | 0.06 | 0.80 | 0.08 | 0.78 | 0.06 | 0.81 | 60.00 | 0.44 | 65.96 | 0.68 |

| Eastern Cape unemployment | 0.06 | 0.80 | 0.16 | 0.69 | 0.13 | 0.72 | 40.36 | 0.25 | 48.06 | 0.28 |

| Northern Cape unemployment | 0.65 | 0.42 | 1.17 | 0.28 | 1.04 | 0.31 | 26.86 | 0.47 | 31.21 | 0.61 |

| Free state unemployment | 0.01 | 0.92 | 0.07 | 0.79 | 0.06 | 0.81 | 58.56 | 0.31 | 67.51 | 0.36 |

| Kwazulu Natal unemployment | 0.17 | 0.68 | 1.86 | 0.18 | 1.57 | 0.22 | 58.60 | 0.31 | 71.83 | 0.23 |

| North West unemployment | 0.45 | 0.50 | 1.07 | 0.31 | 0.85 | 0.36 | 0.60 | 0.44 | 71.58 | 0.46 |

| Gauteng unemployment | 0.46 | 0.50 | 0.63 | 0.43 | 0.54 | 0.47 | 41.79 | 0.20 | 51.84 | 0.17 |

| Mpumalanga unemployment | 0.28 | 0.59 | 1.16 | 0.29 | 0.98 | 0.33 | 43.32 | 0.50 | 49.53 | 0.61 |

| Limpopo unemployment | 0.01 | 0.93 | 0.00 | 0.96 | 0.00 | 0.97 | 0.60 | 0.44 | 64.12 | 0.73 |

-

Authors’ Computation.

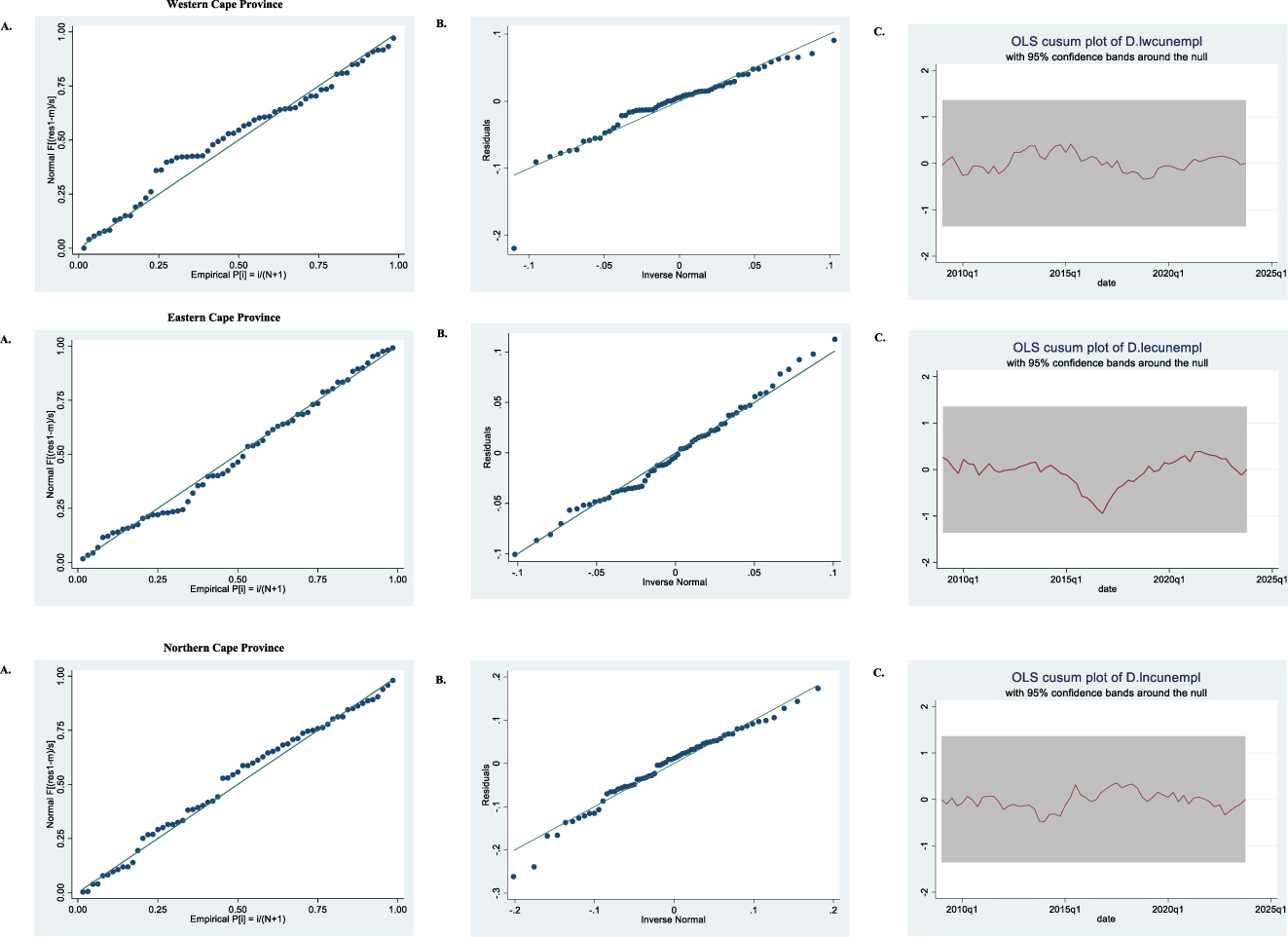

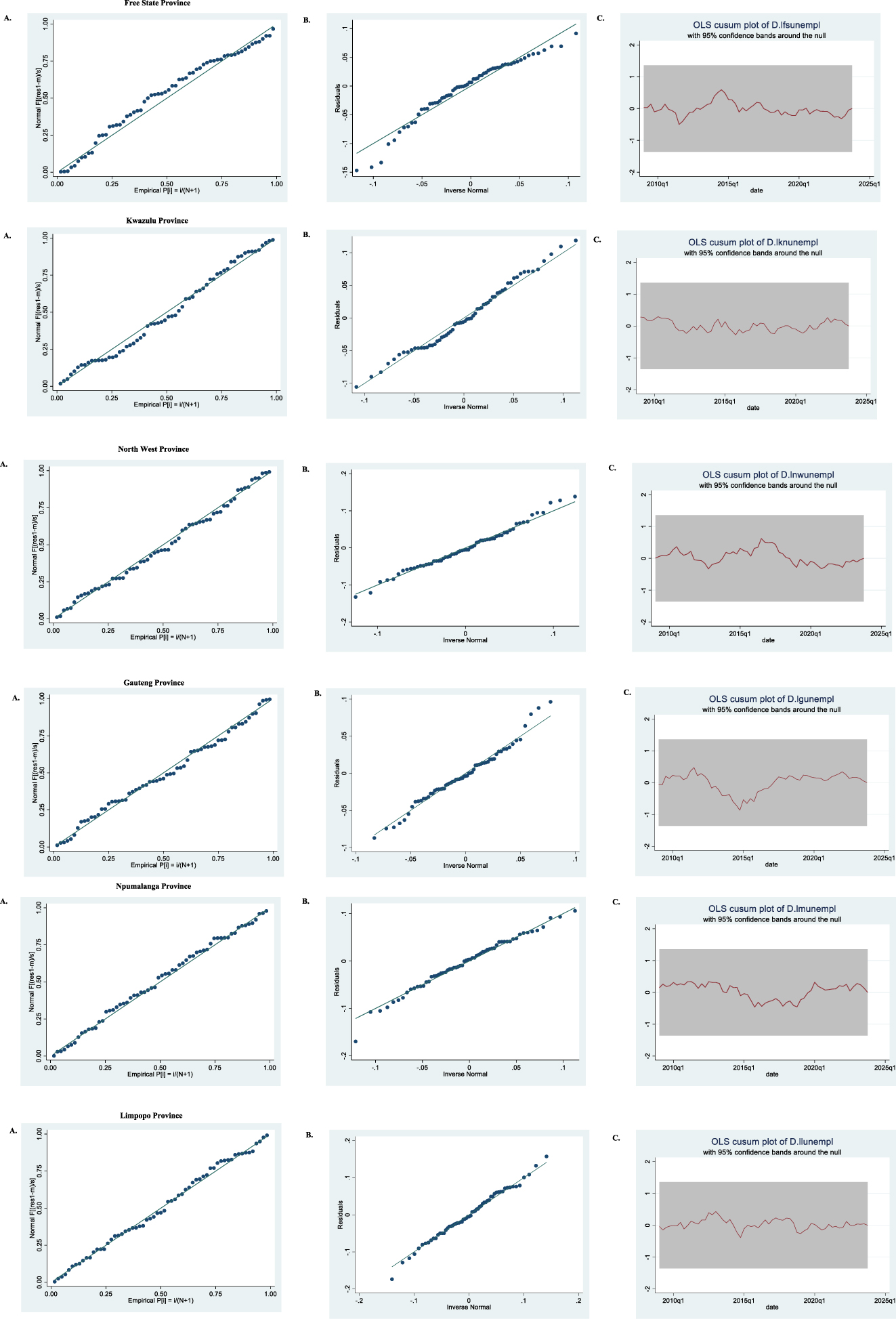

Standardized normal probability graphs (Figures 3As) as well as that of quantiles of residuals against quantiles of normal distribution (Figures 3Bs) estimates, were also plotted to further validate the distribution of the data series applied in the models. The figures in the different ARDL models confirm normal distributions using both figures. Also, the null hypothesis of structural breaks or the assumption that the time series swiftly changed in ways not predicted, examined with the OLS CUSUM plots (See Figures 3Cs), were debunked, the tests statistics of the plots aligned within the 5 % significance levels of the plots or within the 95 % confidence interval bands. The outputs of the diagnostic tests show that the models are well-fitted and satisfy the screening procedures.

(A) Standardized Normal Probability Graphs. (B) Quantiles of Residuals against Quantiles of Normal distribution. (C) OLS CUSUM Plots of Types of Unemployment Rate for Parameter Stability. NB: The recursive cusum plots within the 95% confidence bands confirm the stability of the estimated models.

4.4.3 Dynamic ARDL Results

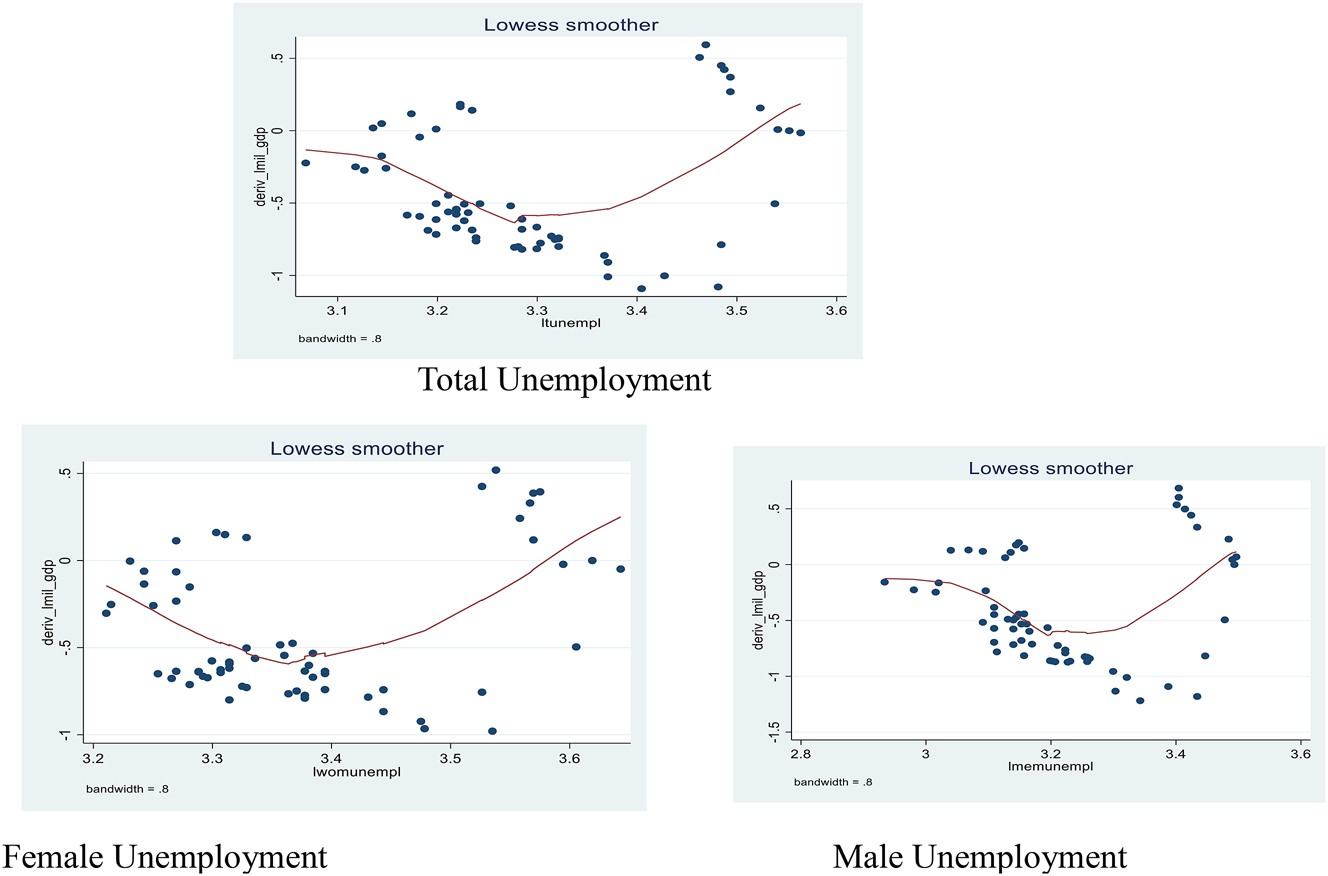

Our goal in this section is to answer a simple question: Does an increase or decrease in military spending by a certain amount favour unemployment reduction in South Africa? In other words, we investigate the counterfactual impact of military spending on all the unemployment categories. To answer this question, we employed DARDL. As previously mentioned, DARDL is useful for this kind of analysis because it captures the effect of a counterfactual change in the main regressor on the dependent variable and thus, allows for an easy way to trace the effect of the regressor on the independent variable through a graphical visualisation interface (Sarkodie and Owusu 2020). Thus, we simulate the effect of shocks to military spending on all the categories of unemployment, considering a scenario of a 1 % reduction or increase in military spending. This is important for policy formation regarding addressing the issue of the relationship between government expenditure, especially military spending and unemployment in the country. The results of this exercise are presented through the graphical visualisation interface.

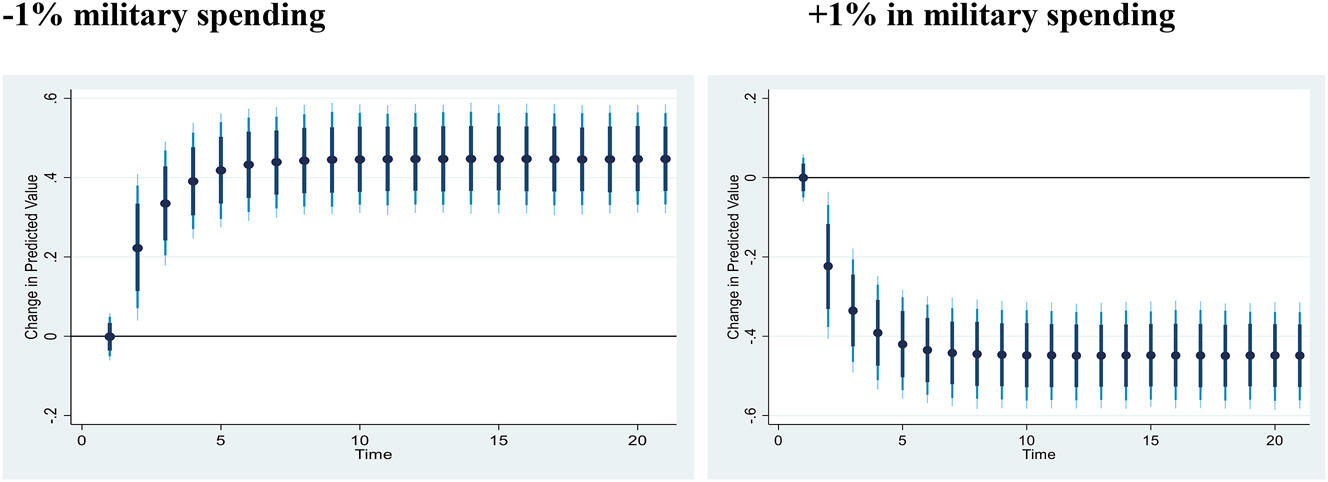

Starting with Figure 4ia and b, we can see that a 1 % reduction in military spending leads to a temporary worsening of the total unemployment rate, lasting up to 5 quarters. Conversely, an increase in military spending leads to a reduction in unemployment within the same quarters. This suggests both increased and decreased military spending have a temporary effect on unemployment in South Africa because, as shown in the figure, after declining and increasing unemployment, the effect of military spending flats out or remains constant. This suggests that the long-term effect has been established. This finding demonstrates that addressing the unemployment issue in South Africa is not linked to military spending alone. This result is consistent with the findings Raifu and Aminu (2023a), who observed that unemployment in South Africa is primarily a structural issue stemming from limited access to higher-paying sectors and skill development, as well as challenges related to poverty, inequality, and limited economic prospects among certain racial groups.

Total Unemployment Rate: Counterfactual shock in predicted military spending using dynamic ARDL simulations. A 1 % decrease and increase in military spending and its influence on total unemployment rate, where dots specify the average prediction value. However, the dark blue to light blue line denotes 75 %, 90 %, and 95 % confidence intervals, respectively.

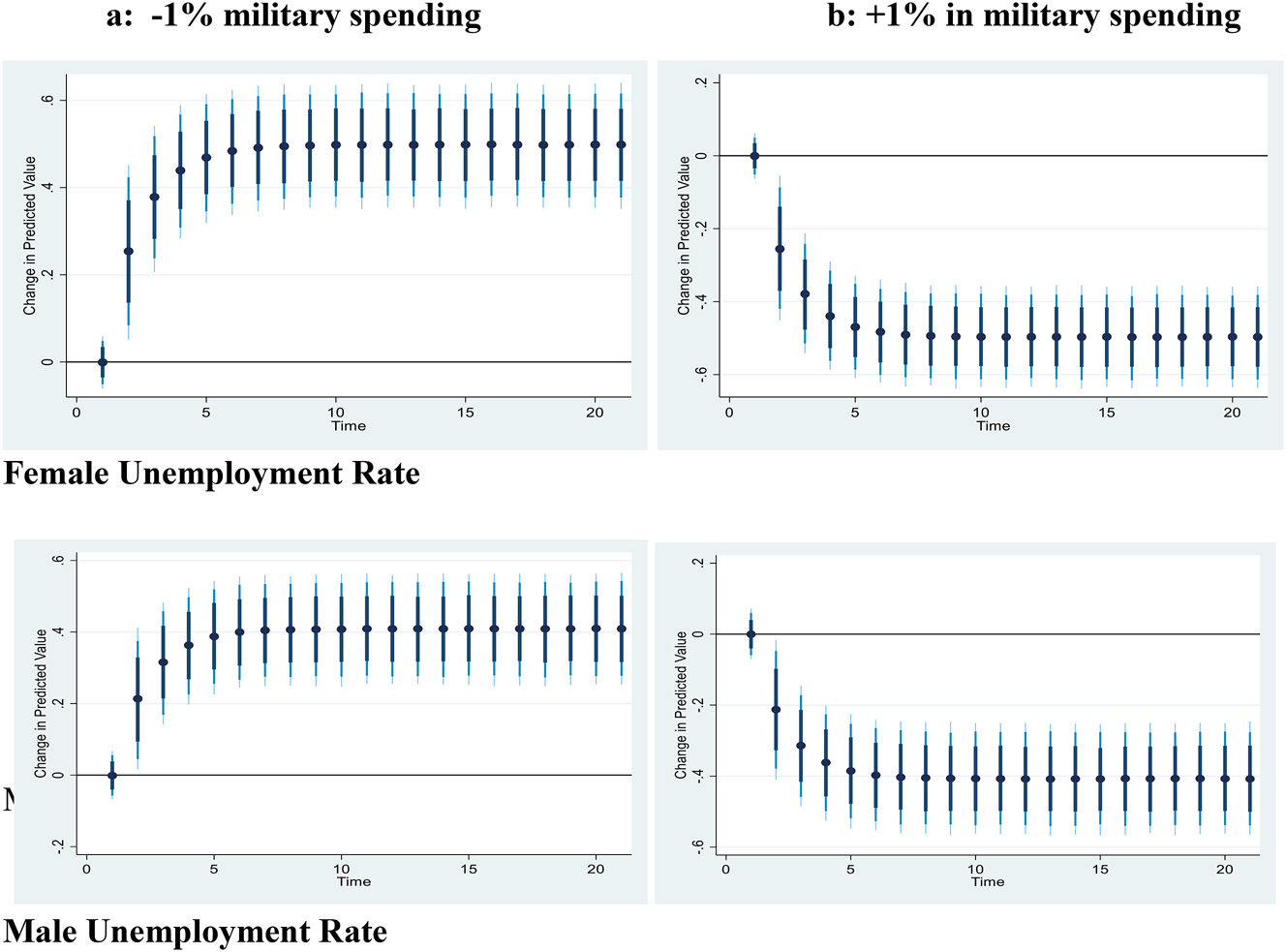

4.4.3.1 Gender Unemployment

The response of gender unemployment, (female and male), to a shock in military spending, is similar to the response of total unemployment. As illustrated in Figures 4iia and b, a shock that leads to a 1 % reduction (increase) in military spending in South Africa causes a short-term increase (decrease) in both male and female unemployment. However, over time, these rates tend to flatten out, much like the overall unemployment rate does. This suggests that reduced military spending initially worsens male and female unemployment rates. Adjustments in military spending cause short-term changes in male and female unemployment rates.

Gender Unemployment Rates: Counterfactual shock in predicted military spending using dynamic ARDL simulations. A 1 % decrease and increase in military spending and its influence on gender unemployment rates, where dots specify the average prediction value. However, the dark blue to light blue line denotes 75 %, 90 %, and 95 % confidence intervals, respectively.

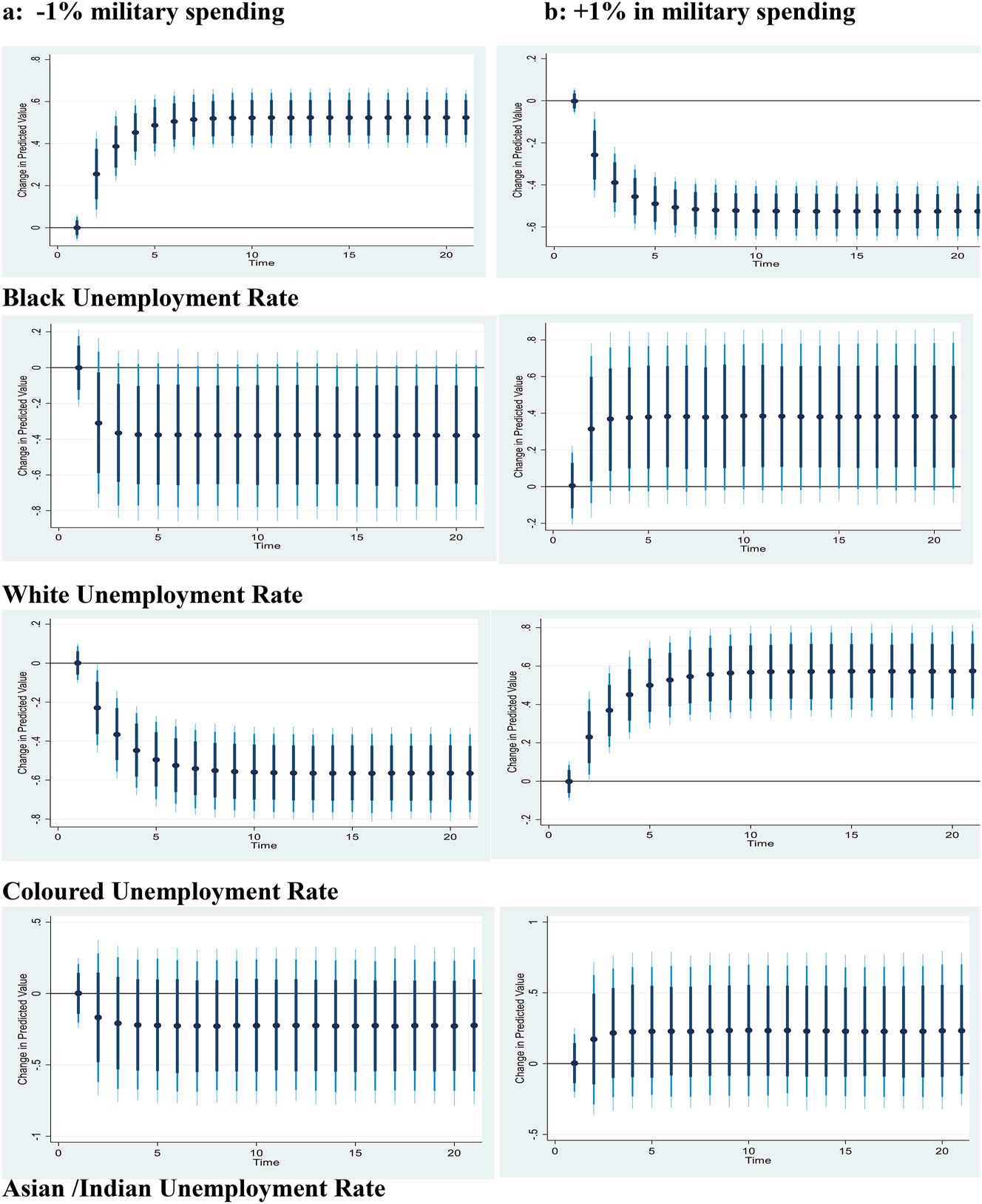

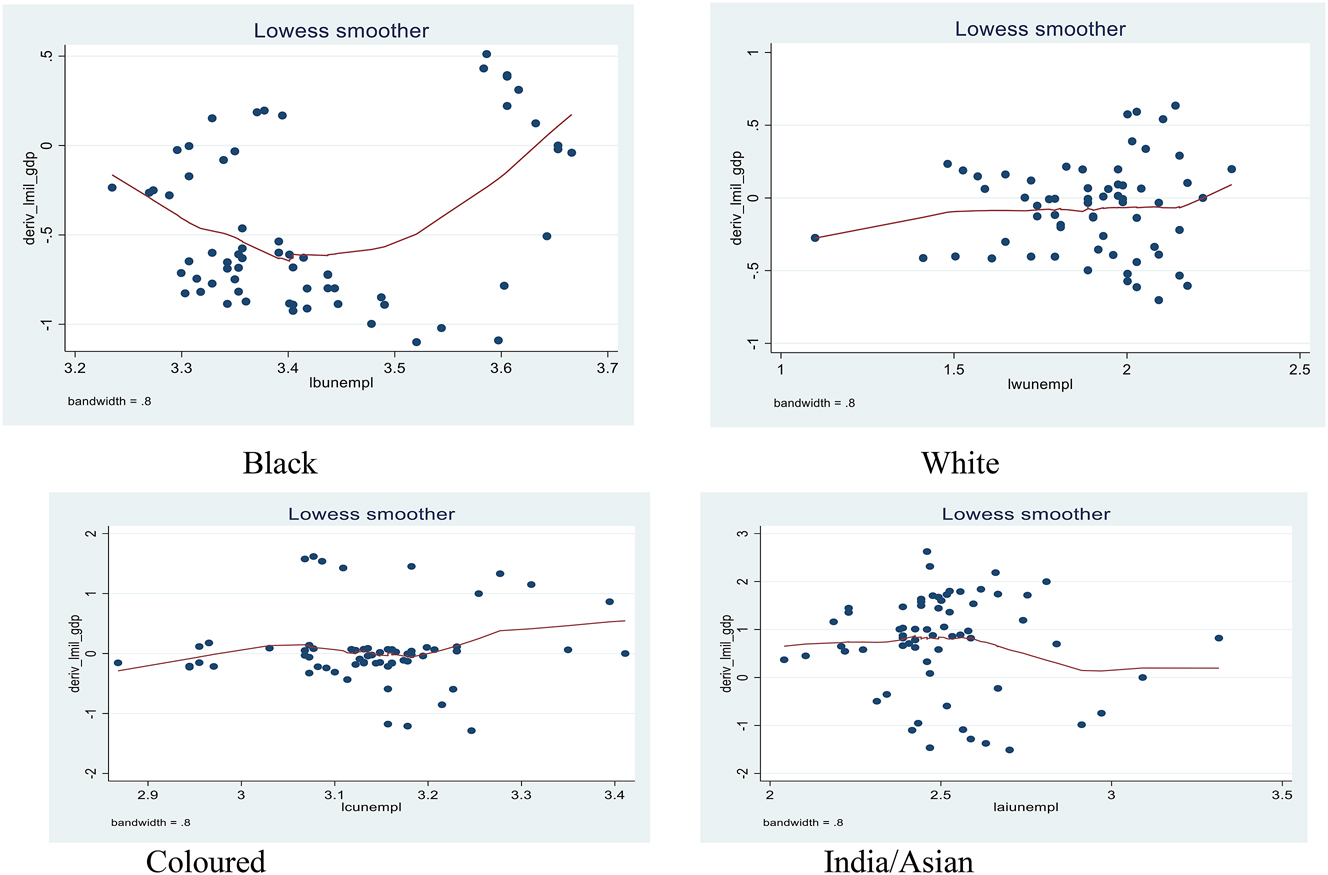

4.4.3.2 Race Unemployment Rate

In this section, we examined how racial unemployment rates respond to shocks to military spending. As shown in Figures 4iiia and b, the response of the black race unemployment to either a decrease or an increase in military spending by 1 % aligned with the responses of total and gender unemployment rates. Specifically, a shock that leads to reducing or increasing military spending by 1 % results in an increase or a decrease in black race unemployment in the short run but stabilises in the long term. For the white race unemployment rate, the graphs depict that increased or decreased military spending by 1 % does not have a discernible impact. The findings for the Asian/Indian race were similar to that of the white race. Therefore, based on DARDL, an increase in military spending does not significantly impact the unemployment rates of the whites and the Asians/Indians. The response of the coloured race’s unemployment rate to a shock to military spending is the opposite of that of the black race. Specifically, a shock that results in a 1 % decrease or increase in military spending would cause a corresponding decrease or increase in the unemployment rate among the coloured population, implying that a reduction in military spending would lead to a decrease in unemployment among the coloured people in South Africa. Increased military spending in South Africa favours the Blacks who constituted about 80 and 70 % of the population of the SANDF since 1994 (Heinecken and Van der Waag-Cowling 2013; Heinecken 2009). Given these statistics, any military expenditure, especially for recruitment purposes into the SANDF grants more opportunities to the Blacks than to other Races. The implication is that the reduction in the rate of unemployment reduces with increased military spending in the Black Race. On the contrary, a decrease in military spending, channelled to other sectors of the economy reduces the unemployment rate in the White, Indian/Asian and Coloured Races, who are now up-skilling or migrating to skilled jobs in the country.

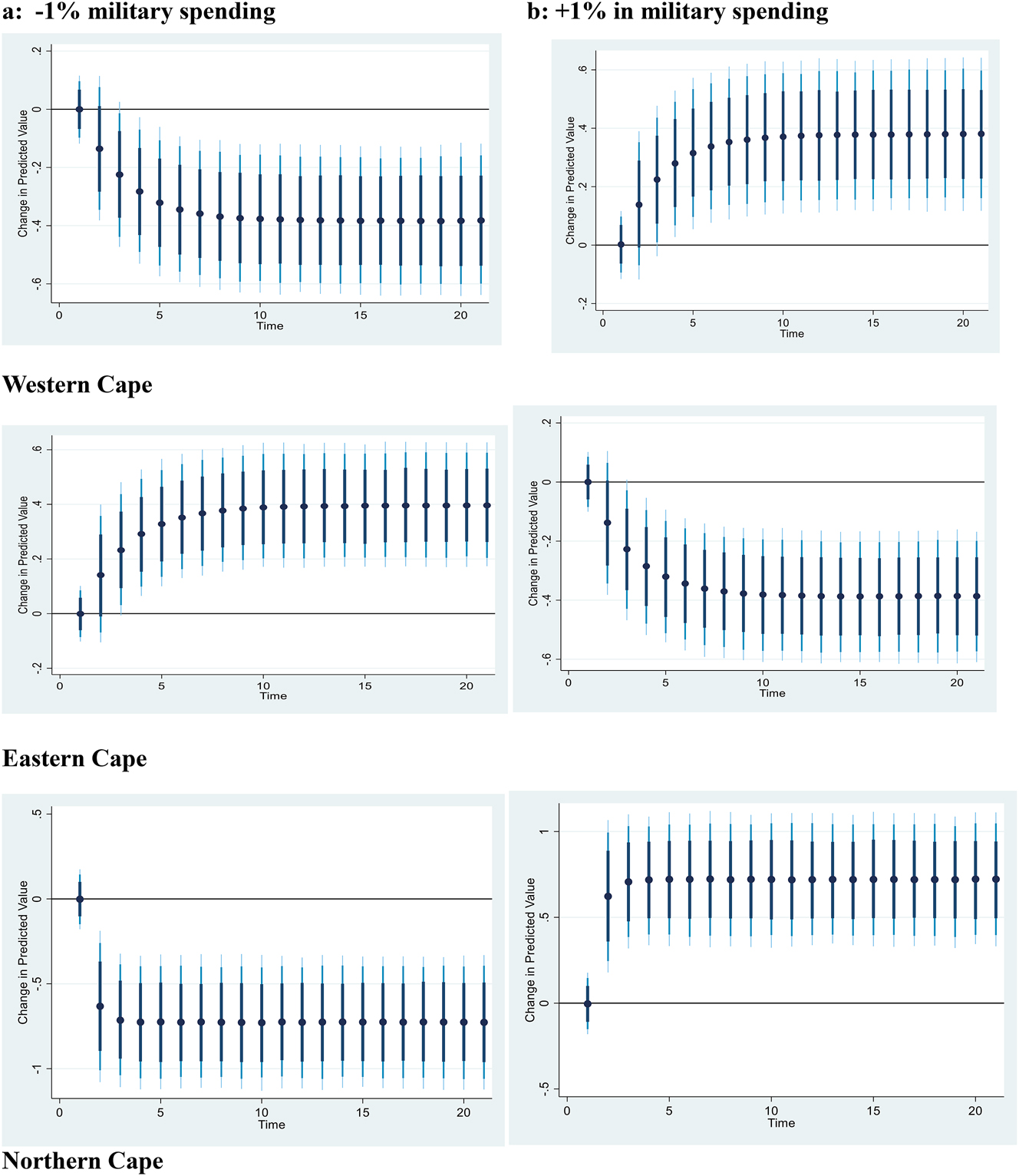

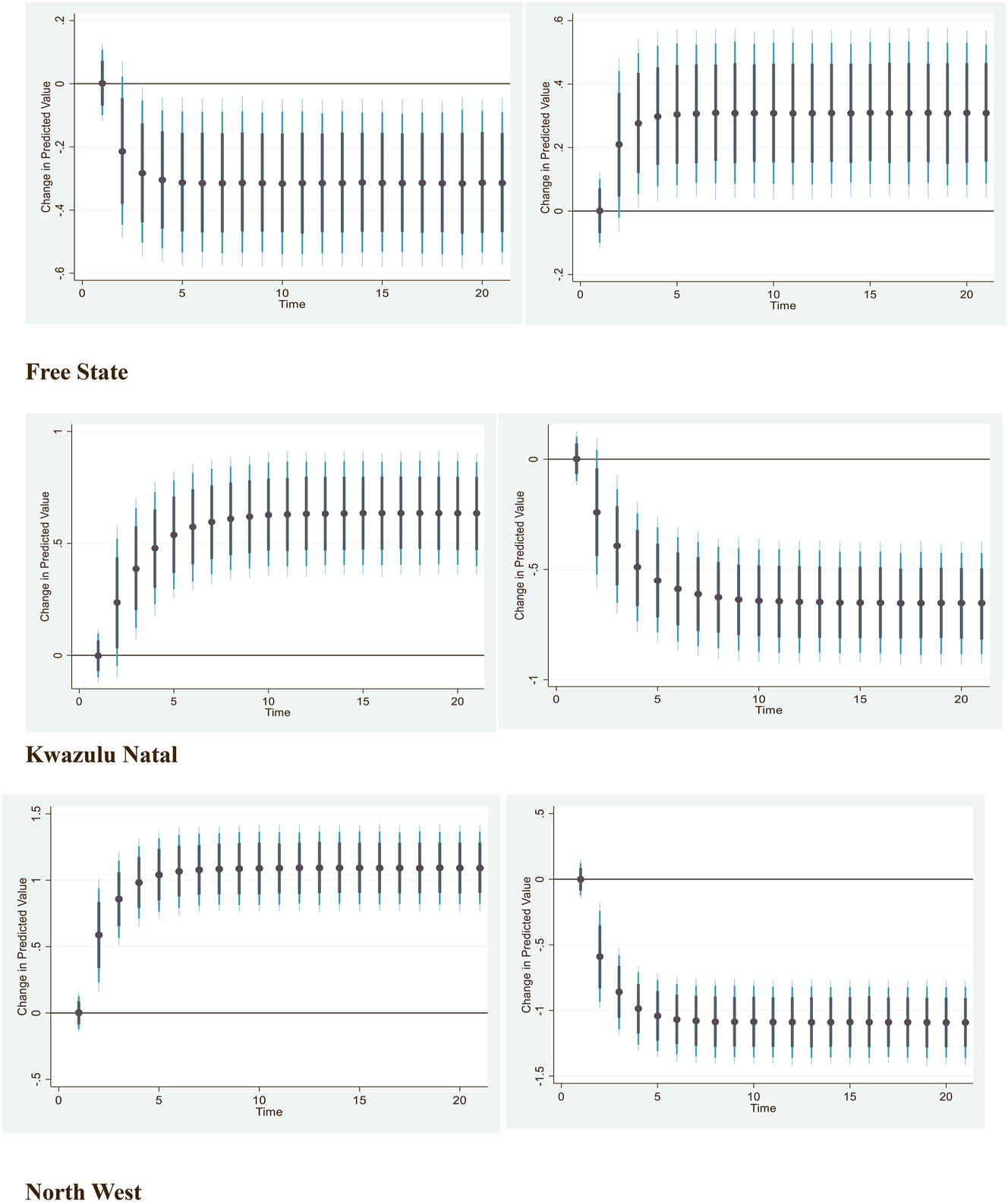

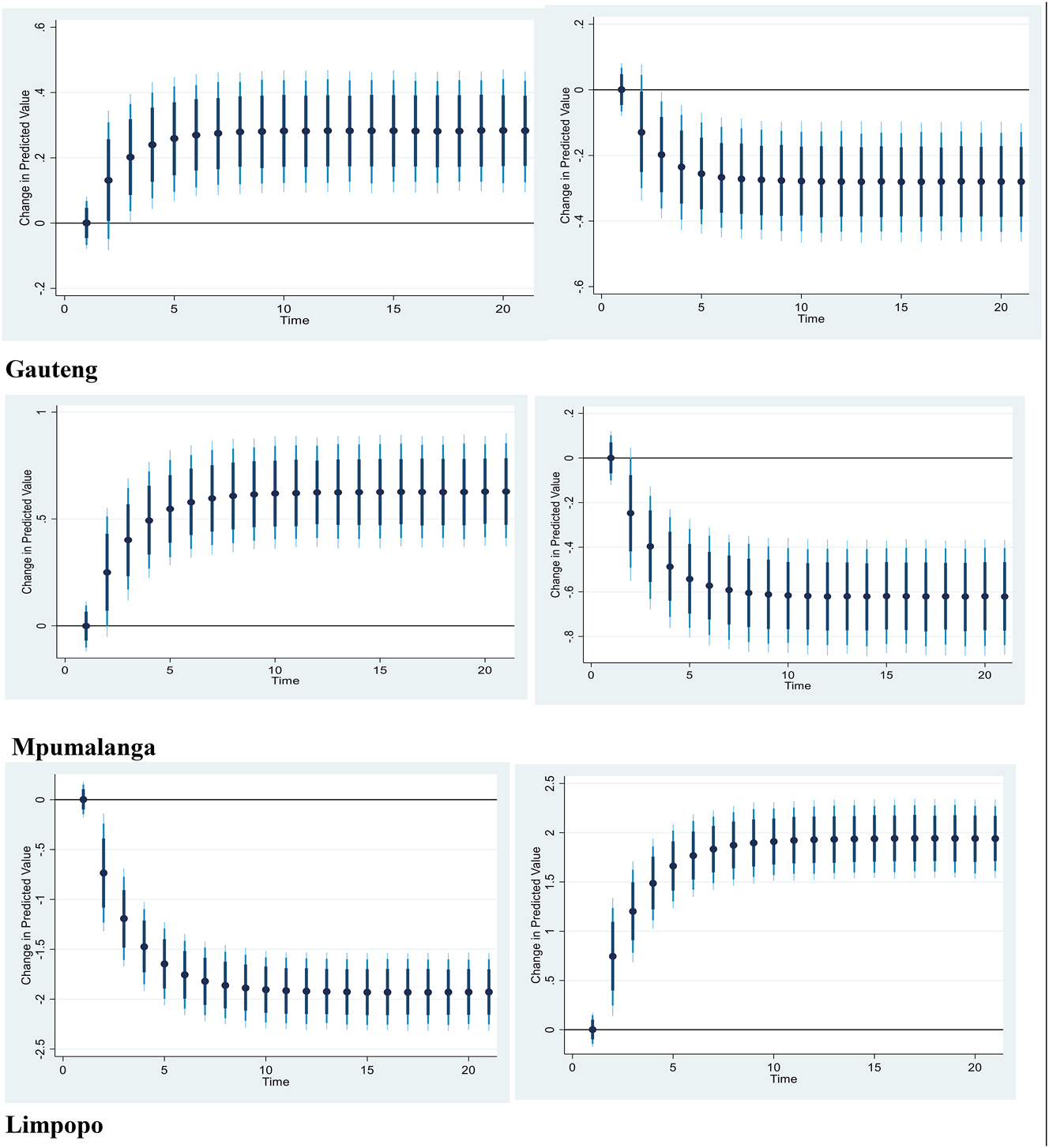

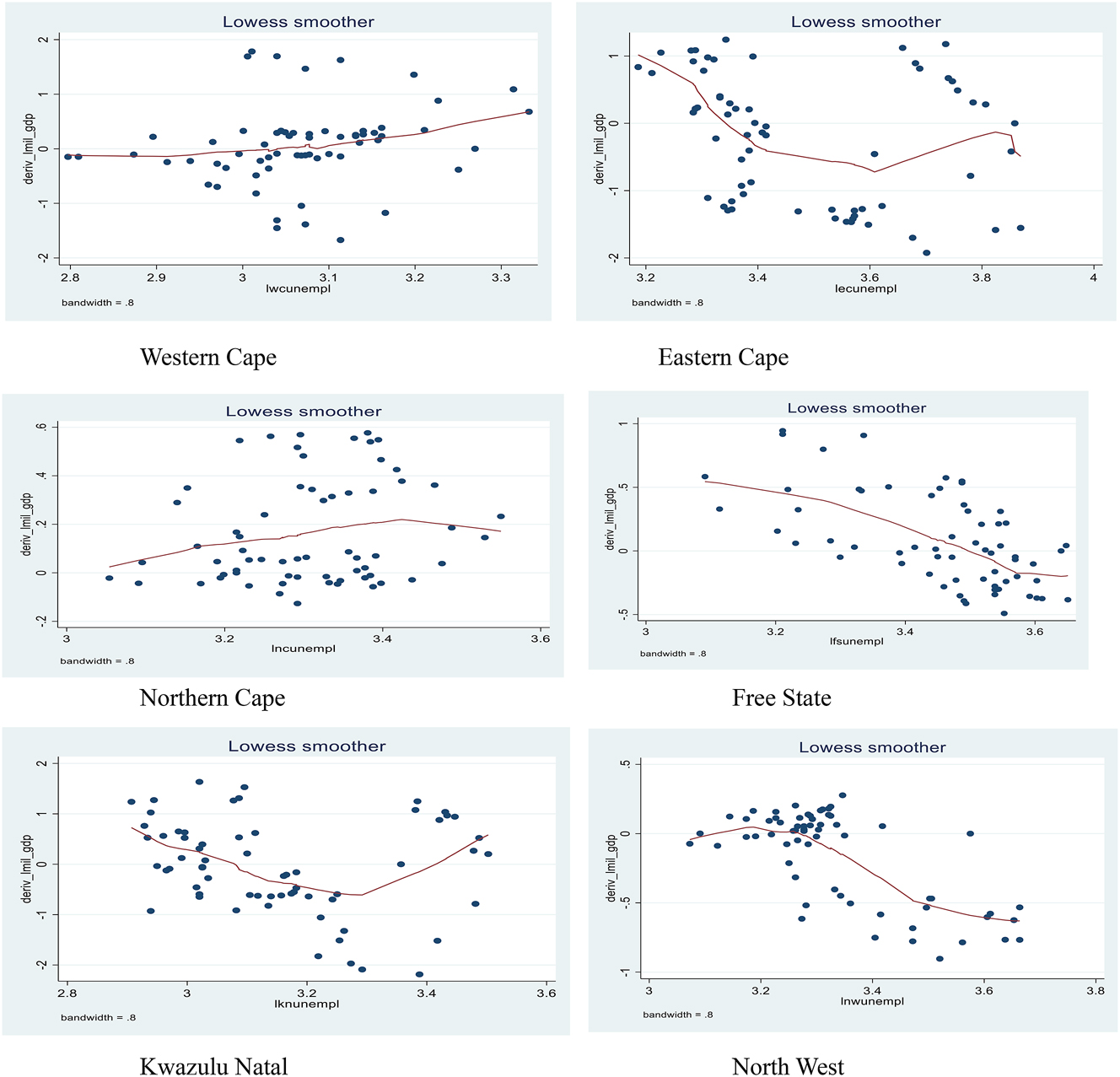

4.4.3.3 Province Unemployment Rates

Figures 4iva and b showed the results of the counterfactual change in military spending on unemployment rates across the provinces. From the figure, the shock to military spending yields similar effects in three provinces among the nine provinces. Precisely, a shock that leads to a decrease (increase) in military spending leads to a decrease (increase) in the unemployment rate in provinces such as Western Cape, Free State, and Limpopo provinces. However, such an effect is a short-term phenomenon, as it only lasts 5 quarters before it flattens out and stabilises for the rest of the quarters. As a result, our findings suggest that reducing military spending will reduce unemployment rates in these provinces, whereas increasing it will worsen it. The reverse is the case for five provinces. In provinces such as the Eastern Cape, KwaZulu Natal, Northwest, Gauteng, and Mpumalanga, a shock that results in a decrease (increase) in military spending is likely to cause a corresponding increase (decrease) in those provinces. This suggests that these provinces would benefit if the government increased military spending, but would be worse off if the government continued to reduce military spending. Furthermore, we discovered that a shock that leads to an increase or a decrease in military spending has no discernible effect on unemployment in the Northern Cape Province. In other words, an increase or decrease in military spending does not have a significant effect on the province’s unemployment rate (Figure 4iv).

Race Unemployment Rates: Counterfactual shock in predicted military spending using dynamic ARDL simulations. A 1 % decrease and increase in military spending and its influence on race unemployment rates. The dots specify average prediction value, while the dark blue to light blue lines denote 75 %, 90 %, and 95 % confidence intervals, respectively.

Province Unemployment Rates: Counterfactual shock in predicted military spending using dynamic ARDL simulations. A 1 % decrease and increase in military spending and its influence on total unemployment rate, where dots specify the average prediction value. However, the dark blue to light blue line denotes 75 %, 90 %, and 95 % confidence intervals, respectively.

4.4.4 Kernel-Based Regularized Least Squares (KRLS) Results

The pointwise derivatives of the estimated KRLS that show the causal-effect relationship between military spending and unemployment in the different models are presented in Table. Precisely, Table 7 shows that the mean pointwise marginal effects of military spending on total and gender (female and male) unemployment rates are 0.42 %, 0.41 %, and 0.42 %, respectively. This implies that the total female and male unemployment rates are reduced by the above percentages. This also serves as evidence that the negative impact of military spending on both total and female unemployment rates remains consistent across all percentiles. In terms of race groupings, the marginal effects of military spending on the unemployment rates of Black, White, Indian/Asian, and Coloured races are 0.46 %, 0.7 %, 0.74 %, and 0.5 %, respectively. However, the effect, despite being negative, was statistically significant only for the Black race, both on average and across all percentiles. Thus, military spending reduces black race unemployment compared to other races. Table 7 also presents the marginal effects of military spending on provincial unemployment. Focusing on the statistically significant ones, the table provides evidence that military spending reduces unemployment in provinces like the Eastern Cape and Gauteng, while it exacerbates it in the Northern Cape. The explanatory variables explain between 50 and 99 % of the models’ variability, which ranges from 50 to 99 %. Hence, the variables are important in explaining both aggregated and disaggregated unemployment rates in South Africa (Table 7). Full result of the KRLS involving all the explanatory variables are displayed in Table 8 in the appendix.

Pointwise derivatives with KRLS.

| Variables | Average | P25 | P50 | P75 | R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total unemployment | −0.418*** (0.065) | −0.744 | −0.564 | −0.007 | 0.972 | |

| Gender | Female | −0.412*** (0.069) | −0.694 | −0.588 | −0.063 | 0.970 |

| Male | −0.418*** (0.072) | −0.821 | −0.525 | 0.053 | 0.969 | |

| Race | Black | −0.464*** (0.068) | −0.809 | −0.629 | −0.036 | 0.969 |

| White | −0.073 (0.164) | −0.346 | −0.019 | 0.112 | 0.852 | |

| Coloured | 0.053 (0.118) | −0.173 | −0.023 | 0.084 | 0.836 | |

| Asian/Indian | 0.740 (0.298) | 0.350 | 0.876 | 1.518 | 0.755 | |

| Province | Western Cape | 0.063 (0.133) | −0.222 | 0.095 | 0.313 | 0.822 |

| Eastern Cape | −0.231* (0.132) | −1.256 | −0.092 | 0.648 | 0.972 | |

| Northern Cape | 0.162** (0.074) | −0.016 | 0.063 | 0.340 | 0.501 | |

| Free state | 0.073 (0.119) | −0.232 | 0.011 | 0.326 | 0.908 | |

| KwaZulu Natal | −0.056 (0.167) | −0.632 | −0.060 | 0.626 | 0.958 | |

| North West | −0.157 (0.137)\ | −0.486 | −0.003 | 0.105 | 0.858 | |

| Gauteng | −0.842*** (0.091) | −1.411 | −0.829 | −0.384 | 0.956 | |

| Mpumalanga | −0.015 (0.230) | −1.507 | −0.072 | 0.860 | 0.990 | |

| Limpopo | 0.166 (0.304) | −2.292 | −0.109 | 2.221 | 0.984 | |

-

The average marginal effects are the figures in the first rows of the model, while the standard errors are in parentheses, ***p < 0<.01, **p < 0<.05, *p < 0<.1; Authors’ Computation.

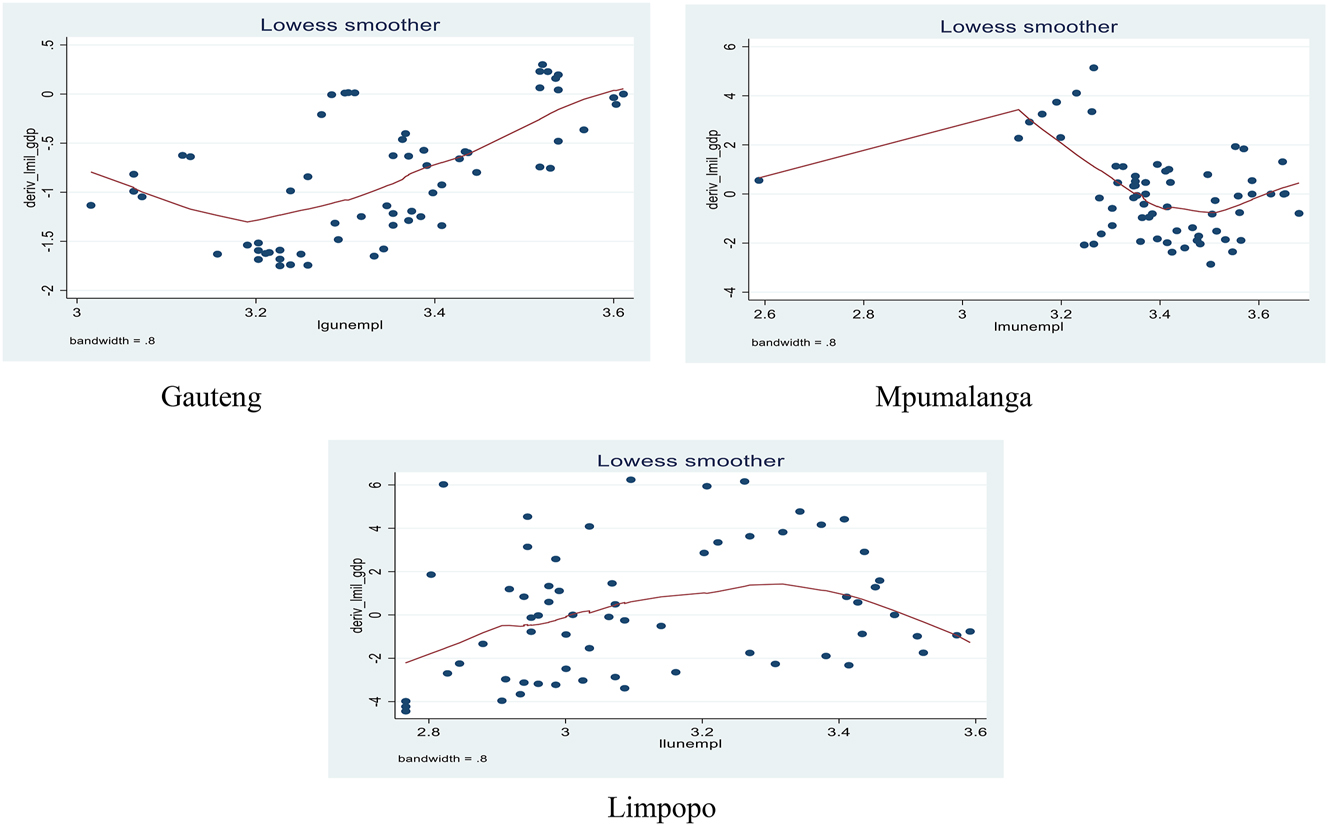

The study further explored the marginal effects of a change in military spending on unemployment rates in the different models by plotting the pointwise derivative of military spending against unemployment rates. The figures show that higher levels of military spending decrease unemployment rates up to a certain level where further increases in military spending begin to accelerate unemployment rates in the total and gender unemployment rate groupings. In other words, military spending has decreasing marginal effects on total, female and male unemployment rates up to a certain threshold before upsurges in the unemployment rates continue (See Figure 5i).

Pointwise plot of marginal effect of military spending against total, gender unemployment rates.

In the racial unemployment rates, the pointwise derivative plotting of military spending against unemployment rates indicates also a decreasing marginal effect on the Black unemployment rate in the short term, a negative level in the mid-term and a positive level in the long-term. In other words, military spending decreases the Black Race unemployment rate up to a certain level before it increases again. Figure 5ii also shows that higher levels of military spending increase unemployment rates in the White, Coloured and Indian/Asian Races at the lower levels. However, the rate of change decreases with time in the Indian/Asian Race. This suggests that military spending has increasing marginal returns on White and Coloured Races unemployment rates and decreasing marginal returns on unemployment rate in the Indian/Asian Race. In other words, military spending leads to higher unemployment rates in White and coloured Races but reduces it Indian/Asian Race.

Pointwise plot of the marginal effect of military spending against race unemployment rates.

In Figure 5iii, the pointwise plots of the marginal effects of military spending against unemployment rates in the different Provinces in South Africa are depicted. The figure indicates that military spending has increasing marginal returns on the Western Cape and northern Caper unemployment rates. This is because higher levels of military spending produced higher levels of unemployment rates in the Provinces. Therefore, military spending worsens unemployment rates in the provinces. Conversely, higher levels of military led to reductions in the rates of unemployment in the Free State, North West and Limpopo Provinces. Hence, there are decreasing marginal effects of military spending on unemployment rates in the Provinces. In the Provinces of Eastern Cape, Kwazulu Natal and Gauteng, the initial reaction of military spending on unemployment rates was a decline up to a certain level before an increase in the rates in the long term. In the case of Mpumalanga Province, there was an initial increase, which peaked at a certain level in the mid-term before declining in the long-run. While military spending has decreased marginal returns on Eastern Cape, Kwazulu Natal and Gauteng Provinces’ unemployment rates only to certain levels, it also has increased marginal returns on the unemployment rate in Mpumalanga Province only to a certain level too.

Pointwise plot of the marginal effect of military spending against province unemployment rates.

5 Concluding Remark and Policy Recommendations

The study examines the effect of military spending on the aggregate and disaggregated unemployment rate in South Africa for the period 2008 to 2023. The study employed ARDL to capture short and long-run relationships, as well as the novel estimated techniques such as novel dynamic ARDL and Kernel-based Regularized Least Squares (KRLS) to capture the impacts of counterfactual shocks in military spending on total, gender, Race and Provinces unemployment rates. The results established that all the variables are integrated of either order zero and one, i.e. I(0) and 1(I) and that the models are cointegrated, thereby satisfying the conditions for an ARDL estimation. The outputs of the diagnostics tests show that the models are well-fitted and in line with the screening procedures. From the results, a rise in military spending implies a reduction in total and gender (male and female) unemployment rates in both the short-run and long-term. However, among the Races, military spending reduced the unemployment rate amongst the Black Race and increased it among the Coloured, White and Indian/Asian Races. Similarly, military spending brought down unemployment rates amongst the Northwest, Gauteng, Eastern Cape and Mpumalanga populations both in the short run and the long run, and in the KwaZulu Natal province in the long run, only. The reverse was the case for Western Cape, Northern Cape and Free State Provinces in both short and long-run periods, and in the Limpopo Province in the short run where military spending does not have any unemployment quashing effect.

The DARDL simulation and KRLS, which predicted the counterfactual shocks of the unemployment rate based on a 1 % reduction and addition military spending, are also presented in the analysis. The result showed that decreasing or increasing military spending by 1 % reduced total and gender unemployment rates, and also unemployment rates among the Black Race and Provinces of the Northwest, Gauteng, Eastern Cape, Mpumalanga, KwaZulu Natal and Limpopo population. The average impact of a 1 % reduction or additional to military spending could not trickle down to unemployment rates in the Coloured, White and Indian/Asian Races and to the Western Cape, Northern Cape and Free State Provinces, where it caused upsurges in the unemployment rates. This suggests that the average impact of military spending on unemployment rates in South Africa is very restrictive, given its inability to trickle down or reduce unemployment in all Races and Provinces. The DARDL results were confirmed by the KRLS plots which show the directions of effects or the pointwise marginal effects of military spending on total, gender, Race and Province unemployment rates. While military spending caused decreasing marginal effects on total, female, male, Black, Northwest, Gauteng, Eastern Cape, Mpumalanga, KwaZulu Natal and Limpopo populations, it led to increasing marginal effects on Coloured, White and Indian/Asian, Western Cape, Northern Cape and Free State unemployment rates. The positive impacts of military spending on employment on the Black Race and its dominated Provinces of Gauteng, Eastern Cape, Mpumalanga, KwaZulu Natal and Limpopo follows the assertive AA and EO legislation which has seen the Blacks surpass their target in the SANDF to about 70 %, while that of the Whites and the Indians/Asians, dropped to about 16 % and 1 %, respectively, from 2009 (Heinecken and Van der Waag-Cowling 2013; Heinecken 2009). This has positively affected the impact that increased military spending could make in the unemployment rates of the White and Indian/Asian dominated provinces of Western Cape, Northern Cape and Free State.

The above results show that the consequences of a rise in military spending are not homogeneous among the Races and Provinces in the two periods. The outcome suggests that military spending policies aimed at reducing the rate of unemployment in South Africa should be Race and Province specific, or at most re-investigated using disaggregated defence spending data devoted to the different genders, Races and provinces, to fully appreciate how such spending impacts the different groups. It also elucidated the importance of increased military spending in reducing the unemployment rate among the majority of the South African population both female and male. Hence, this study advocates for increased military spending in South Africa in other to accommodate vast numbers of workers who may be engaged directly in military roles or in ancillary or supporting activities. Such increased budgetary provision will also help the military personnel for skills acquisition for both the members of the armed forces and chosen members of the civilian population. The skills will make the recipients self-employed. The increased military spending will also make available resources for the maintenance of peace and stability, allow law-abiding citizens and investors the enabling environment to meaningfully engage in their chosen lawful vocations, thereby reducing the rate of unemployment in South Africa. Specifically, while it is important to increase military spending to reduce the unemployment rates in the Black Race and its dominated Provinces of Gauteng, Eastern Cape, Mpumalanga, KwaZulu Natal and Limpopo, there is need to retool the population of the Coloured, White and Indian/Asian Races and the Western Cape, Northern Cape and Free State Provinces, in other to meet the demands of the prevailing job opportunities in South Africa.

See the appendix Table 8.

Pointwise derivatives with KRLS.

| Variable | MIL_GDP | Non_MIL_GDP | GDPGR | FDI_GDP | INF | P25 | P50 | P75 | R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Total | −0.418*** | 0.596*** | −0.332** | −0.007 | 0.004* | −0.744 | −0.564 | −0.007 | 0.97 |

| −0.065 | −0.094 | −0.139 | −0.007 | −0.002 | ||||||

| Gender | Female | −0.412*** | 0.440*** | −0.340** | −0.01 | 0.004** | −0.694 | −0.588 | −0.063 | 0.97 |

| −0.069 | −0.101 | −0.156 | −0.008 | −0.002 | ||||||

| Male | −0.418*** | 0.729*** | −0.341** | −0.002 | 0.003 | −0.821 | −0.525 | 0.053 | 0.97 | |

| −0.072 | −0.102 | −0.149 | −0.009 | −0.002 | ||||||

| Race | Black | −0.464*** | 0.533*** | −0.457*** | −0.007 | 0.004** | −0.809 | −0.629 | −0.036 | 0.97 |

| 0.068 | 0.533 | 0.1499 | 0.008 | 0.002 | ||||||

| White | −0.073 | 0.917*** | 0.561* | 0.045* | −0.000 | −0.346 | −0.019 | 0.112 | 0.85 | |

| 0.164 | 0.232 | 0.286 | 0.024 | 0.005 | ||||||

| Coloured | 0.053 | 0.495*** | −0.553** | −0.000 | 0.002 | −0.173 | −0.023 | 0.084 | 0.84 | |

| 0.118 | 0.167 | 0.243 | 0.015 | 0.0045 | ||||||

| Asian/Indian | 0.740** | 1.512*** | −1.478*** | −0.069* | 0.009 | 0.350 | 0.876 | 1.518 | 0.76 | |

| 0.298 | 0.42 | 0.603 | 0 0.038 | 0.009 | ||||||

| Province | Western Cape | 0.063 | 0.611*** | −1.021*** | 0.021 | 0.008** | −0.222 | 0.095 | 0.313 | 0.82 |

| 0.133 | 0.189 | 0.28 | 0.016 | 0.004 | ||||||

| Eastern Cape | −0.231* | −0.004 | 0.553* | −0.001 | −0.007* | −1.256 | −0.092 | 0.648 | 0.97 | |

| 0.132 | 0.202 | 0.324 | 0.013 | 0.004 | ||||||

| Northern Cape | 0.162** | 0.042 | 0.252** | 0.000 | −0.003 | −0.016 | 0.063 | 0.340 | 0.50 | |

| 0.074 | 0.118 | 0.119 | 0.011 | 0.002 | ||||||

| Free state | 0.073 | 0.072 | 1.057*** | 0.023 | 0.005 | −0.232 | 0.011 | 0.326 | 0.91 | |

| 0.119 | 0.169 | 0.247 | 0.015 | 0.004 | ||||||

| KwaZulu Natal | −0.056 | 0.107 | 0.583 | −0.037** | 0.016*** | −0.632 | −0.060 | 0.626 | 0.96 | |

| 0.167 | 0.263 | 0.43 | 0.015 | 0.004 | ||||||

| North West | −0.157 | 0.726*** | 0.40 | −0.01 | 0.011*** | −0.486 | −0.003 | 0.105 | 0.86 | |

| 0.137 | 0.191 | 0.265 | 0.018 | 0.004 | ||||||

| Gauteng | −0.842*** | 0.932*** | −0.805*** | −0.015 | −0.002 | −1.411 | −0.829 | −0.384 | 0.96 | |

| 0.091 | 0.129 | 0.189 | 0.011 | 0.003 | ||||||

| Mpumalanga | −0.015 | −1.294*** | 0.586 | 0.000 | −0.002 | −1.507 | −0.072 | 0.860 | 0.99 | |

| 0.23 | 0.357 | 0.505 | 0.014 | 0.004 | ||||||

| Limpopo | 0.166 | 1.685*** | −4.410*** | 0.019 | −0.008 | −2.292 | −0.109 | 2.221 | 0.98 | |

| 0.304 | 0.471 | 0.706 | 0.02 | 0.005 | ||||||

-

The average marginal effects are the figures in the first rows of model, while the standard errors are in the second, ***p < 0<0.01, **p < 0<0.05, *p < 0.1.

References

Abell, J. D. 1992. “Defense Spending and Unemployment Rates: An Empirical Analysis Disaggregated by Race and Gender.” The American Journal of Economics and Sociology 51 (1): 27–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1536-7150.1992.tb02504.x.Suche in Google Scholar

Akerlof, G. A., and J. L. Yellen. 1985. “A Near-Rational Model of the Business Cycle, with Wage and Price Inertia.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 100 (Supplement): 823–38. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/100.supplement.823.Suche in Google Scholar