Abstract

Contemporary Iran is estimated to be home to 75 languages. Yet, since the rise of Persian nationalism over the past century, the state’s language management and policies have granted the official status to the Persian language and script alone and led to regulations prohibiting any public use of non-Persian script in formal signage. Against this backdrop, this paper investigates ideological and political indexical meanings of the de jure and de facto policies as well as grassroots practices by ethnic minority groups with respect to writing and choice of script(s) in Iran. We draw on different government policy documents, and samples of writing on social media by different social actors in different parts of the country. We showcase how the state’s monolingual language policies are contested by the indexical meanings ethnic minority speakers evoke through their specific script choices in their writing on social media spaces. We argue that multi-scriptal writing, by indexing translocal and transnational identities, challenges monolingual policies, with strong implications for national unity.

1 Introduction

Iran is a diverse country with various ethnolinguistic groups, including Persians, Azerbaijanis, Kurds, Arabs, Lurs, Gilakis, Turkmens and Mazandaranis. Persians, the politically and socially dominant group, make up the largest ethnic group in Iran. Internal migration (Abrahamian 2008; Moradi 2020) and lack of official statistics which could be otherwise retrieved from the country’s census make it hard to report a reliable number of speakers of different languages associated with ethnic communities. Published sources, however, suggest that the combined population of ethnic minorities in Iran approximately equals that of Persians, with Azerbaijanis comprising 24 %, Gilakis and Mazandaranis 8 %, Kurds 7 %, Arabs 3 %, Lurs 2 %, Baluchis 2 %, Turkmen 2 %, and other groups 1 % (Karimzad 2018; Tohidi 2009).

Notwithstanding the multiethnic and multilingual makeup of the country, the Persian (a.k.a. Farsi) language has been the only official language of the country since 1906 when the language was declared for the first time the official language by Iran’s National Assembly (Abrahamian 2008). The policy mandated Persian for administration, education, and public affairs, coercing compliance and marginalizing diverse ethnic groups (Kia 1998). Since then, particularly under the Pahlavi Dynasty (1925–1997), nationalist movements have intensified. Reza Shah (1925–1941), the founder of the Dynasty, who gained power through a military coup d’état in 1921, aimed to promote a unified Iranian identity. This identity was rooted in pre-Islamic Persian culture and Iranian identity and the Persian language was purged from foreign (non-Persian) influences like Arabic and Turkish (Kia 1998). The king established a centralized government in Tehran and exerted political, economic, and sociocultural control over the rest of the country (Katouzian 2009). Reza Shah’s government imposed linguistic and cultural homogenization, which continued well into his son’s rule (Mohammad Reza, 1941–79), elevating Persian as the sole marker of civilization and outlawing minority languages (Perry 1982). Other minorities, in particular larger groups such as Azerbaijanis, Kurds, and Arabs, were stigmatized for using their mother tongue and pressured to assimilate into Persian culture and give up their ethnic identity (Asgharzadeh 2007; Shaffer 2002). Since then, these policies have reinforced Persian dominance while suppressing Iran’s multiethnic and multilingual reality (Mirvahedi 2016).

The return of Ayatollah Khomeini to Iran in February 1979, after years of exile for opposing Mohammad Reza Pahlavi’s regime, however, marked the culmination of the Iranian Revolution showcasing Islam’s potential as not just a religion, but also a powerful sociopolitical ideology (Mirvahedi 2019). Drawing on Islamic political thought and offering a radically different vision for society and individual life, the revolution ushered in a period of unprecedented change. In terms of language policy, Arabic as the liturgical language of Islam, for instance, was granted particular attention in Article 16 of the new Constitution, making it a compulsory subject in the education system.

Article 16

Since the language of the Qur’an and Islamic texts and teachings is Arabic, and since Persian literature is thoroughly permeated by this language, it must be taught after elementary level, in all classes of secondary school and in all areas of study.

The newly-established Islamic Republic of Iran adopted the ideology of Muslim brotherhood. Under its view that “in Islam … the question of border, color, language and race doesn’t exist” (Paul 1999: 209), attitudes toward ethnolinguistic diversity in Iran were reformed. This perspective is currently reflected in Articles 15 and 19 of the Constitution, which provide a legal basis for protecting the languages of ethnic minorities.

While the Iranian Constitution acknowledges the nation’s diverse linguistic and ethnic composition and outlines a framework for safeguarding human and linguistic rights, it simultaneously establishes Persian as the sole official language and script of the country, a continuation from the 1906 Constitution. This designation mandates the use of Persian in education, official documents, and textbooks (Sheyholislami 2012). However, a shift away from the strictly assimilationist language policies of the monarchy is evident, as non-Persian languages are permitted in media, press, and education as outlined in Articles 15 and 19.

Article 19

All people of Iran, whatever the ethnic group or tribe to which they belong, enjoy equal rights; and color, race, language, and the like, do not bestow any privilege.

Article 15

The official language and script of Iran, the lingua franca of its people, is Persian. Official documents, correspondence, and texts, as well as textbooks, must be in this language and script. However, the use of regional and tribal languages in the press and mass media, as well as for teaching of their literature in schools, is allowed in addition to Persian.

While Articles 15 and 19 of the Iranian Constitution could theoretically form a foundation for institutional support of ethnic minorities and linguistic justice, their practical impact has been limited. The permissive, rather than prescriptive, nature of Article 15 effectively consigns these languages to the vagaries of market forces because it lacks concrete provisions for teaching minority languages as subjects, e.g. in the form of teaching their literature, using non-Persian languages as languages of instruction within a bilingual framework, or for their use in administration and public services. Iran’s centralized, monolingual education system exemplifies this, creating a “sink or swim” environment (May 2012: 172), where non-Persian speakers must rapidly acquire Persian or face academic disadvantage. Consequently, Persian is implicitly positioned as the “ideal” language for education and socioeconomic mobility, for all citizens, regardless of ethnicity (Phillipson 1988: 341–342). This has resulted in the restriction of even widely spoken languages like Azerbaijani and Kurdish to informal spheres (Bani-Shoraka 2009; Mirvahedi 2017). As a result of the homogenizing effects of Persian-centric policies, families felt pressure to invest heavily in Persian to prepare their children for a Persian-medium education, and the literacy rate in Persian has consequently risen to approximately 89 % over the years. Many studies thus report that the participants they surveyed claimed not to be able to read or write their ethnic language such as Azerbaijani and Kurdish commensurate with their literacy in Persian (Mirvahedi and Jafari 2021; Rezaei and Bahrami 2019; Tamleh et al. 2022).

2 The politics of writing

In multilingual and multinational states where questions of national identity and nationhood remain contested, written language cannot be understood merely as transforming speech to orthographic representations; rather graphic representations as a semiotic resource carry sociopolitical and historical connotations (Woolard 2020). Iran is no exception. Iranians use different languages and scripts in their daily lives for various reasons. Yet, there exists a dearth of research on the politics of writing in Iran, shedding light on such questions as script choice in both formal and informal settings and its indexical meaning for both individuals and the government (see Mirvahedi 2016). It is clear that Article 15 of the Constitution, although potentially opening up space for minority language use in media and schools, puts a particular emphasis on writing in Persian. This is reflected in declaring Persian not only as the official language but also recognizing the Perso-Arabic script[1] as the official script of the country. Associating both the Persian language and script with being the lingua franca of the country, Article 15 mandates that similar to the Persian language, the Perso-Arabic script must be used as the common means of communication in formal writing, thus regarding the use of other scripts as a violation of the law. Given that the law stipulates that all official writing be conducted in this language and script, which is reflected and backed by educational policies, the literacy rate in Persian across all the non-Persian ethnic groups, especially among the young, is very high. Thus, Article 15 is not wrong in assuming that the Persian script would function as the common means of writing in the country.

Following Article 15, there have been more detailed policies regarding script choice and writing, strengthening the position of the Persian script. In December 1996, for example, the Iranian Parliament passed the Prohibition of Using Foreign Names, Titles, and Terms Act, the first Article of which states that:

Article 1

In order to maintain the rigor and essence of the Persian (Farsi) language as one of the columns of the Iranian national identity and the second language of the Muslim world and Islamic culture and teaching … using foreign words, names, and terminologies, on all products produced by public and private sectors to be distributed inside the country is prohibited.

As noted in the Article, Persian is considered a pillar of the Iranian national identity as well as Islamic cultural identity. Any use of non-Persian language is therefore viewed as a threat to the rigor and essence of the Persian language, which is strongly linked to both Iranian and Islamic identity. Following such ideology, the other articles of the Constitution also prescribe the script choice with more detailed instructions for bilingual/biscriptal signs:

Article 14

Using signs, symbols or writings in a non-Persian script is prohibited except for international signage. Police are required to prevent the installation and use of such signage.

Note: In cases where using non-Persian script is deemed necessary at the discretion of the Ministry of Islamic Culture and Guidance, it must be one third the size of the Persian script.

According to this Article, non-Persian scripts can appear in public if they meet two conditions. First, they cannot be the sole script used on signage; instead non-Persian script should be accompanied by the Persian script. Second, there must be a valid reason, for instance, an intended international audience for the non-Persian script to be allowed on a sign at all. Because the Note following the Article mandates that on signage the non-Persian script should be one-third of the Persian script in size, it can be concluded that such regulations attempt to effectively ensure the dominance of the Persian script over other scripts in public space by backgrounding non-Persian writing. Although it is not very clear what “international signage” means here, Article 5 of one of the sections of the rules and regulations of advertisement, namely Policies of Naming Streets and Public Places and Organizations, passed in January 1989, implies that using foreign names is allowed provided that such names lead to better cultural, scientific, and political bonds:

Article 5

Private shops, companies, and businesses must avoid using foreign names unless in cases such names are chosen to establish cultural, scientific, and political bonds.

Article 5 and 14, which allow non-Persian scripts to be used if they are used for establishing scientific and cultural bonds with other nations, suggest that the policymaking bodies are aware of the indexical meanings that script choice could have. It is assumed here that using a non-Persian script such as the Latin script could mean something more than communicating a message to foreigners who cannot read Persian script. Thus, the government exclusively holds the discretion as to what script to choose, which would ultimately have important implications for permitting what kinds of cultural relations and bonds with other nations are permissible. The seriousness of the issue at the policy level is reflected in the Notes 8 and 9 stating the penalties for violating the law and determining the responsible government organ to enforce the law:

Note 8: All manufacturers, distributors and shop owners, in case they are found in violation of the rules provided here, shall be subjected to the following penalties:

A written notice shall be served on them by the Ministry of Islamic Culture and Guidance.

Changing the signs, symbols, titles, and names by the Home Office or relevant sectors after issuance of an announcement by the Ministry of Islamic Culture and Guidance. The offender will incur all the costs.

Temporary suspension from work.

Revocation of work permit.

Note 9: Police are required to prevent manufacturing and distribution centers and other businesses from installing and using signs in foreign language and script.

While the rules discussed above appear to be concerned with using non-Persian words belonging to ‘foreign’ languages and non-Persian scripts bringing about international scientific and cultural bonds, Article 6 below addresses the use of ethnic minority languages in public signage:

Article 6

People who, in addition to Persian, speak a language of religious minorities specified in the Constitution or a local and ethnic dialects commonly used in certain regions of Iran are allowed to use proper names belonging to that language or dialect in naming services, products, and institutes and organizations provided that they write the meaning of the proper name in Farsi.

In line with Article 15 of the Constitution, Article 6 also allows ethnic languages – described here as ‘dialects’ – to be used in naming services, products and institutions and organizations. Yet, it is required that the meaning of such proper names should also be provided in Persian (for example, if a product’s name is سو /su/ in Azerbaijani, the meaning in Persian, i.e. آب /aab/ meaning ‘water’, should be provided). The Article does not address script choice when it comes to ethnic minority languages in Iran, thus showing the policymakers’ assumption that the writing would be in the Persian script only. Yet, it still requires a Persian translation which can be taken as a strategy to preserve the lingua franca status of Persian in the society. Having discussed policies about the use of both ethnic minority languages and foreign languages within the same policy document, policy makers seem to regard the non-Persian ethnic minority languages as similar to ‘foreign languages’ such as English. That is, both groups of languages and by implication scripts are foreign, thus there is a need to protect Persian against them.

Building on the aforementioned Articles of the Constitution, and despite the limitations discussed above, the Ministry of Islamic Culture and Guidance seems to endorse publications in some of the minority languages by allowing the publishing of guidelines for orthography and spelling. For example, a reference guidebook on writing Azerbaijani has been published, in which standardized orthographic and spelling rules are described (see Figure 1).

Official writing guidelines are not, nonetheless, entirely mirrored in grassroot activities of individuals from diverse ethnic backgrounds. Many Iranians use non-Persian scripts on social media such as Instagram – banned by the government, yet still one of the most popular social networks among Iranians, arguably contesting such a national identity. Envisioning scripts as “symbols that carry historical, cultural, and politicized meanings” (Woolard and Schieffelin 1994: 65), for policymakers, such adherence to non-Persian scripts could be interpreted as a transgressive social act (Pennycook 2010; Scollon and Scollon 2003) that disrupts social and political order in the Iranian ethnic ecology – an interpretation that is arguably rooted in the one-nation-one-language ideology, suggesting that any form of ethnic ties, including using a non-Persian script, should be weakened, if not completely severed (see Mirvahedi 2018).

In the following section, we illustrate and investigate the script choice by the members of different ethnic communities to show how ordinary people have materialized literacy in their script choice – even idiosyncratically – for different purposes, despite the marginal status of non-Persian languages and scripts in education. We focus on how script choice at the grassroots level stands out as a means of sociolinguistic differentiation. We seek to demonstrate that while using Persian script in writing adheres to the policymakers’ ideals of Iranian identity and bespeaks a good Iranian citizen, using other scripts by speakers of minority languages such as Azerbaijanis could index ethnocentric dispositions through “a metaphorical link to both Western languages and to Turkish by means of shared symbols (here, letters)” (Wertheim 2012: 85). We would argue that this happens as script mediates access to semiotic resources to signify an implicit cultural and political connotation.

Standardized guidebook for Azerbaijani orthography and spelling.

3 Scales, translanguaging, and trans-scripting

To understand the complex, polycentric/polynormative, and power-infused interactions in today’s mobile and globalized world, this study employs Blommaert’s (2010) concept of scale. Scale captures the moves (whether of humans or semiotic/material resources) across different ‘times-spaces’. These moves are power moves as they “involve[s] and presuppose[s] access to particular resources, and such access is often subject to inequality” (Dong and Blommaert 2009: 4). Scalar moves are vertically and hierarchically layered, operating at various vertical levels, e.g. local, regional, national, and transnational. Lower scales, i.e. local, are fleeting, highly contextual, and less powerful (Handsfield and Crumpler 2023), whereas higher scales – national or transnational – are timeless, translocal, and prevail over lower scales (Blommaert 2010). There are different scalar moves, such as upscaling (aligning with the hegemony) and downscaling (flattening the hegemony), where people position themselves or their ideologies in relation to embedded norms and values they experience and/or expect to experience (see Stornaiuolo and LeBlanc 2016 for a comprehensive account of different scalar moves).

The moves across scales are inherently discursive and semiotic in which multilinguals deploy a range of semiotic resources in their repertoire – a practice that has come to be known as translanguaging. Translanguaging bears witness to the endorsement of hybrid multilingualism (MacSwan 2022; Sanjani et al. 2025), allowing social actors to intertwine norms, values, and practices to actively beget new orders of indexicality, transgress the established norms, and normalize new values and practices (Wei 2011). In doing so, translanguaging challenges socially constructed language hierarchies that privilege dominant languages, instead highlighting the fluid and polycentric nature of multilingual communication. This alludes to implicit and complex socioemotional behaviors “where the individual feels a sense of connectedness with others, and that sense of connectedness has an impact on the social behaviours of the [social] actor” (Wei 2011: 1234). The connectedness, however, might not align with the socially and politically sanctioned conventions of the national regulations. Therefore, translanguaging “helps to disrupt the socially constructed language hierarchies” that are long sedimented in a given linguistic ecology (Otheguy et al. 2015: 283). The hierarchical antinomy arises from the fact that traditional prescriptivism, anchored in national language policies, primarily empowers and imposes one or two dominant languages over others, whereas translanguaging emphasizes multiplicity, polycentricity, and the diverse features of multilingual interactions (see MacSwan 2022).

To complement this theoretical framework, we introduce the concept of trans-scripting. Rooted in translanguaging theory, we contend that, like spoken variation, trans-scripting, i.e. orthographic representations that carry fluidity and dynamic practices, can empower social actors to index their agency to invoke a move across scales. While refuting the myth of structurally fixed and rigid scripts, we present examples to introduce and define trans-scripting as the social actors’ creative utilization of linguistic repertoire in written format. This subtly dismantles the strong and durée conventions that designate high-valued scripts (and languages) as the norm, which often epitomizes educated and elite individuals. The prerequisite of such malleable utilizations, however, emanates from being in contact with different writing systems with relatively similar orthographical rules.

In this study, combining scale and trans-scripting offers a heteroglossic perspective that conceptualizes writing as a dynamic, processual social practice – fluid, flexible, and nested within scalar hierarchies. With sample data presented below, we illustrate how writing could be “transnational, transcultural, and translingual” (Jenks 2024: 159). We seek to show how combining trans-scripting with theories of scale becomes an especially useful framework to shed light on how social actors draw on their linguistic repertoires in relation to the different scalar levels at which they interact.

4 Methodology

4.1 Research on social media

Social media as a research site has attracted scholars from various fields of study. For sociolinguistics too, social media have been intriguing as social media appear to affect individuals’ ways of thinking and (re)configuring communication, which ultimately changes their way of life, making it a fertile ground for social studies (Yang 2021). Moreover, data collection is facilitated by anonymous observation of naturally-occurring data and ease with respect to transcription (Bolander and Locher 2014). Nevertheless, the ease of access to such data predisposes researchers to “a great temptation to collect more ethically ambiguous data” which has been a topic of concern for sociolinguists (Sandler 2013: 59). To address professional and ethical concerns, our methodology thus adheres to established ethical guidelines (The British Psychological Society 2021) by focusing exclusively on publicly available data, avoiding traceable quotations,[2] and anonymizing any user-identifiable information in accordance with expectations of online privacy (see Mocanu et al. 2023).

4.2 Data collection and analysis procedure

The online data were collected between April and late May 2025 by systematic and non-participatory observation of Instagram posts. We used keywords in Persian, Azerbaijani, Kurdish, Arabic, and Turkmen, including ethnic names with hashtags (e.g., #Azerbaijani), as well as terms related to culture and language (e.g. ‘ana dili’ in Azerbaijani or ‘zimanê kurdî’ in Kurdish meaning ‘mother tongue’). We also monitored the public posts of popular cultural pages and influencers associated with the four Iranian ethnic minority groups–Azerbaijanis, Kurds, Arabs, and Turkmens–to gather the data. Furthermore, we employ textual analysis on Instagram posts in order to filter out the linguistic patterns that individuals used to represent their voices. The goal is not to conduct discourse analysis or examine the various tones and intentions behind the statements (e.g. debate, praise, critique, advocate). Rather, the choice of script itself (code), as it has important sociopolitical implications, is the main focus of the study. We focus on script choice as a semiotic resource which, in the context of online interactions, can reveal novel configurations of public and private expression. These choices, however, are illustrative of how these ethnic minorities employ “stylistically possible” scripts to exert their social identities (Coupland 2007: 28). It is also crucial to note that these illustrations are not of isolated or idiosyncratic phenomena. The scriptal practices such as the use of the Latin script by Azerbaijani agents below were recurrent patterns observed throughout our larger dataset. Therefore, while we avoid making sweeping generalizations about what all members of these groups ‘typically do,’ the chosen cases are representative of common and prominent practices present within the communities under investigation.

A dataset of 140 Instagram comments and/or captions, all of which were publicly posted was collected. The liminal data was further narrowed down to 60 comments/captions to be closely analyzed as they represent the thematic relevance. These posts and comments were chosen because they most clearly reflected the general patterns of script choice and identity negotiation that are central to our theoretical framework. Based on the framework, two types of data were within the scope of this study: (i) Instagrammers’ pragmatic language use and (ii) their discursive/semiotic practices. While the former made it possible to examine how language is utilized using multilinguals’ linguistic repertories, the latter, with particular attention to scalar dynamics, made it possible to interrogate the ‘how’ and ‘in relation to whom’ these repertoires are co-articulated.

Individuals whose writings on Instagram were analyzed did not consent to have their online identity acknowledged. Hence, following Ess et al.’s (2002) suggestion and similar to Landert and Jucker’s (2011) approach, we made sure to respect user privacy and protect their confidentiality. In doing so, we transcribed the data in the following section without including any direct comment or post from the authors.

5 Data analysis: Grassroots writing practices

Scripts as ‘ideology-laden avenues’ (Sebba 1998) are never treated as neutral in nature; they embody subjective social meanings and identities. This can be seen clearly in how Iranian ethnic minorities adopt scripts as their normative de facto bottom-up practices, to establish online identity (Boyd 2014) and reflect their sociopolitical ideologies. To illustrate, we focus here on their L1 script choices/practices, projecting what variations they enact, and therefore legitimize, in written channels. The languages under investigation are: Azerbaijani, Kurdish, Arabic, and Turkmen. In the following, we elaborate on some representative samples (discussions of each language group are presented after the data is provided). Before that, however, it is important to contextualize the geospatial distribution of these minority groups within a visual framework. This is because the orthographic practices used by minorities sometimes resemble those of co-ethnic communities in neighboring cross-border regions (Figure 2). By illustrating this, the article offers readers a detailed geographical context, foregrounding the influential role of transnational scale, demonstrating how cross-border power dynamics have shaped within-border norms and practices, thereby affecting the local/national scales.

Ethnolinguistic distribution of Iran (Wikipedia 2021)

5.1 Azerbaijani

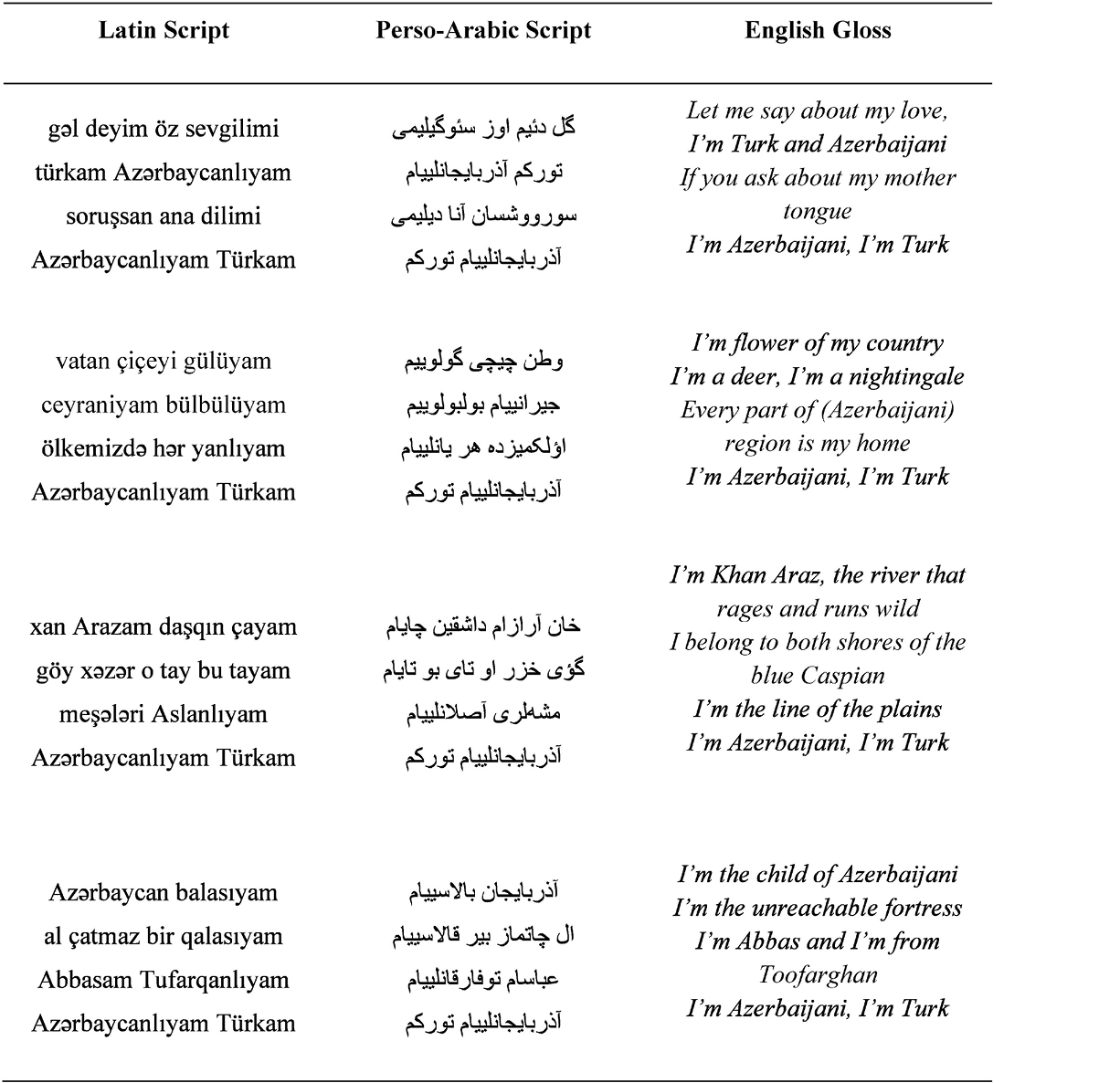

Azerbaijani is spoken primarily in northwestern Iran, especially in the provinces of East Azerbaijan, West Azerbaijan, Ardabil, and Zanjan. The data reveal that through two different orthographic representations, social actors initiated an innovative attempt to de-Persianize the Azerbaijani language. The first Azerbaijani Instagrammer’s post (Transcription 1) shows the bilingual side-by-side use of both Perso-Arabic and Latin scripts. In technical words, the author adopts trans-scripting to make sense, gain a wider audience, and articulate the stored thoughts into scripts. This illuminates that the author is literate in both scripts and renders them legitimate using both. By doing so, they take a neutral and/or in-between social stance towards the two scripts at their disposal. As such, while implying an act of alignment with the broader national scale of legitimized conventions, i.e. the official Perso-Arabic script, the author depicts a sort of semi-oriented impetus (a subtle affinity) towards the Latin script. This manifests the influence of transnational scale as it permeates the national and local scales and renders their norms and conventions in grassroots practices.

All the examples below include an English gloss for an international readership; none of the authors used English as their language choice.

Azerbaijani Instagrammer 1.

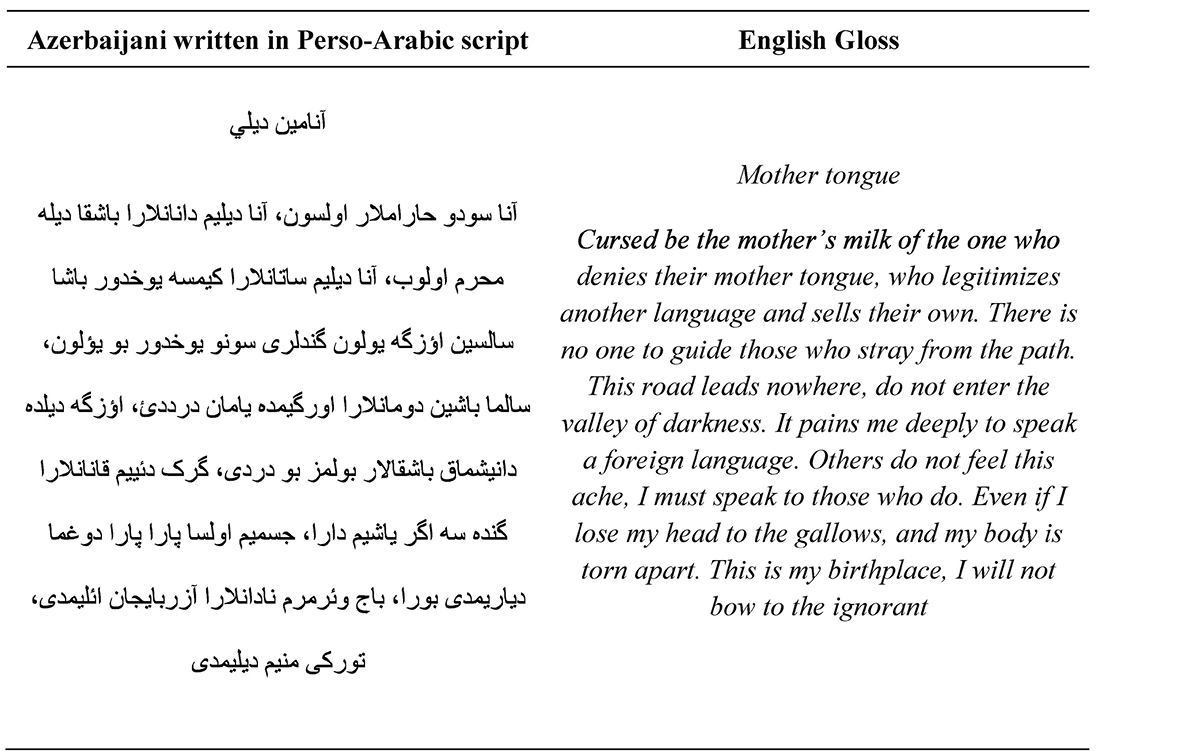

In contrast, in Transcription 2 the author employs a Perso-Arabic script alone despite the content being expressed in the Azerbaijani language, while conveying a sense of belonging and commitment to the Azerbaijani language. The script choice here suggests a full-fledged commitment to the omnipresent official rules regarding writing norms. Acknowledging that online linguistic practices can vary significantly across platforms with different audiences (e.g. Jongbloed-Faber 2021; Lexander and Androutsopulos 2023), the findings here show that Transcription 2 is the most prevalent orthographic choice among the Instagram users in our sample. This suggests that there is a convoluted interplay between identity belonging, emanating from the local scale, and utilization of the Perso-Arabic script, bestowed as the official script of the country. This interplay negates the assumption that scales are one-way-only conceptions, where higher scales always ascertain the superiority, regulations, and norms. Rather, scales are non-linear; there are times when lower scales subjugate times-spaces to exert their structural affordances and invoke local norms to be materialized at higher scale levels. This non-linearity feature of scales is what Blommaert (2010) calls ‘downscaling,’ where norms and expectations from lower scales (here local) are borrowed and expanded to the higher scales (here national). A stronger downscaling is demonstrated in the Kurdish case below.

Azerbaijani Instagrammer 2.

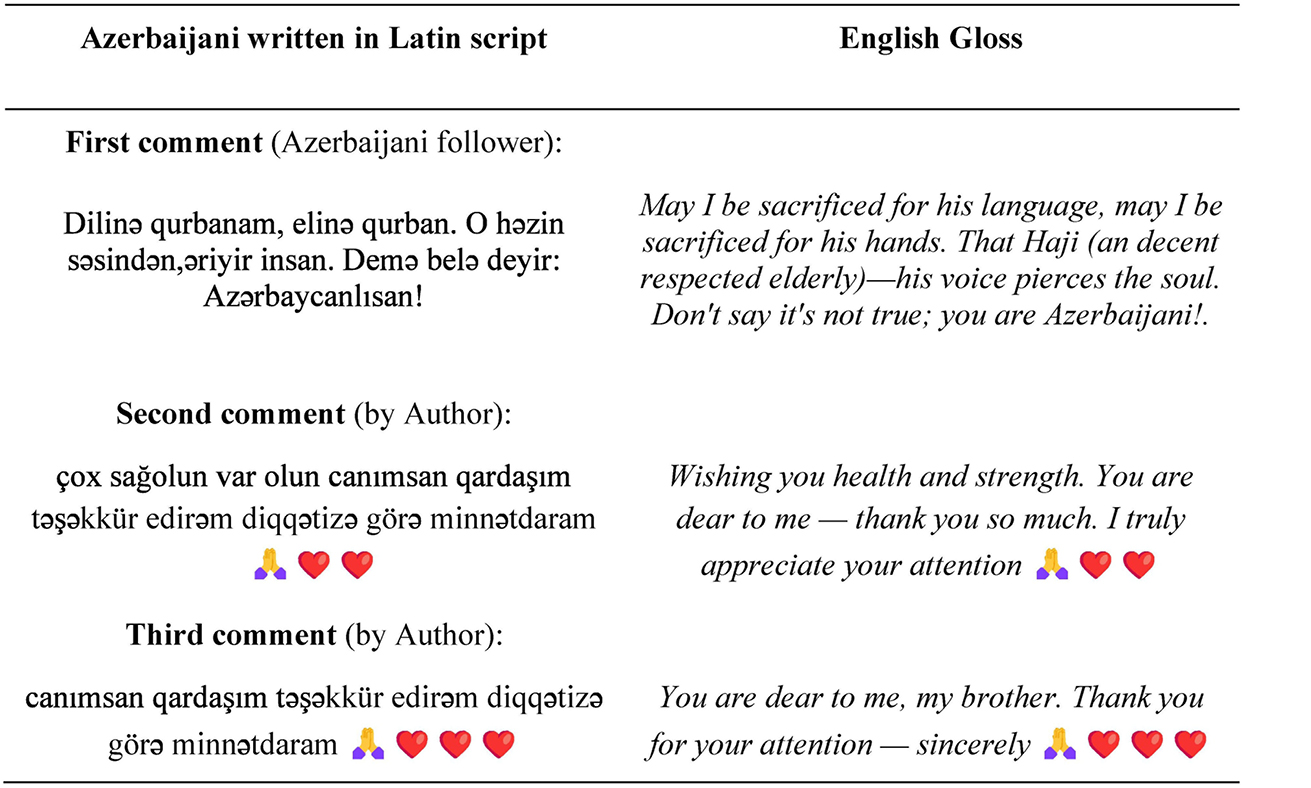

Transcription 3 below, however, projects a clear rupture compared to the previous two Transcriptions. As a response to a comment in Latin script, the author communicates with a fellow Azerbaijani follower in Latin script, which could arguably suggest and construct familiarity.

Azerbaijani Instagrammers 3.

The rupture illuminates a re-scaling process and corroborates Blommaert’s (2010) argument that there is no single, universal, stable scale that applies to all interactions. This use of Latin script also indexes an inclination towards a more formal/prestigious and higher scale; a strategic alignment with the norms and values situated at the transnational scale, through what is known as upscaling (Stornaiuolo and LeBlanc 2016). The upscaling in Transcription 3 is in abject violation of the official narrative, because Latin script is regarded as ‘foreign’ and therefore an illegitimate script. As such, while implying an act of sociolinguistic differentiation from that of mainstream speakers (being Farsi speakers), the Latin script signals the proximity to a united Turkish identity. Using Latin script, in addition, indexes pro-Western orientations where scripts, as metonymic links, enmesh in real-world dynamics by expediting access to Western modernization and civil advancement (Wertheim 2012).

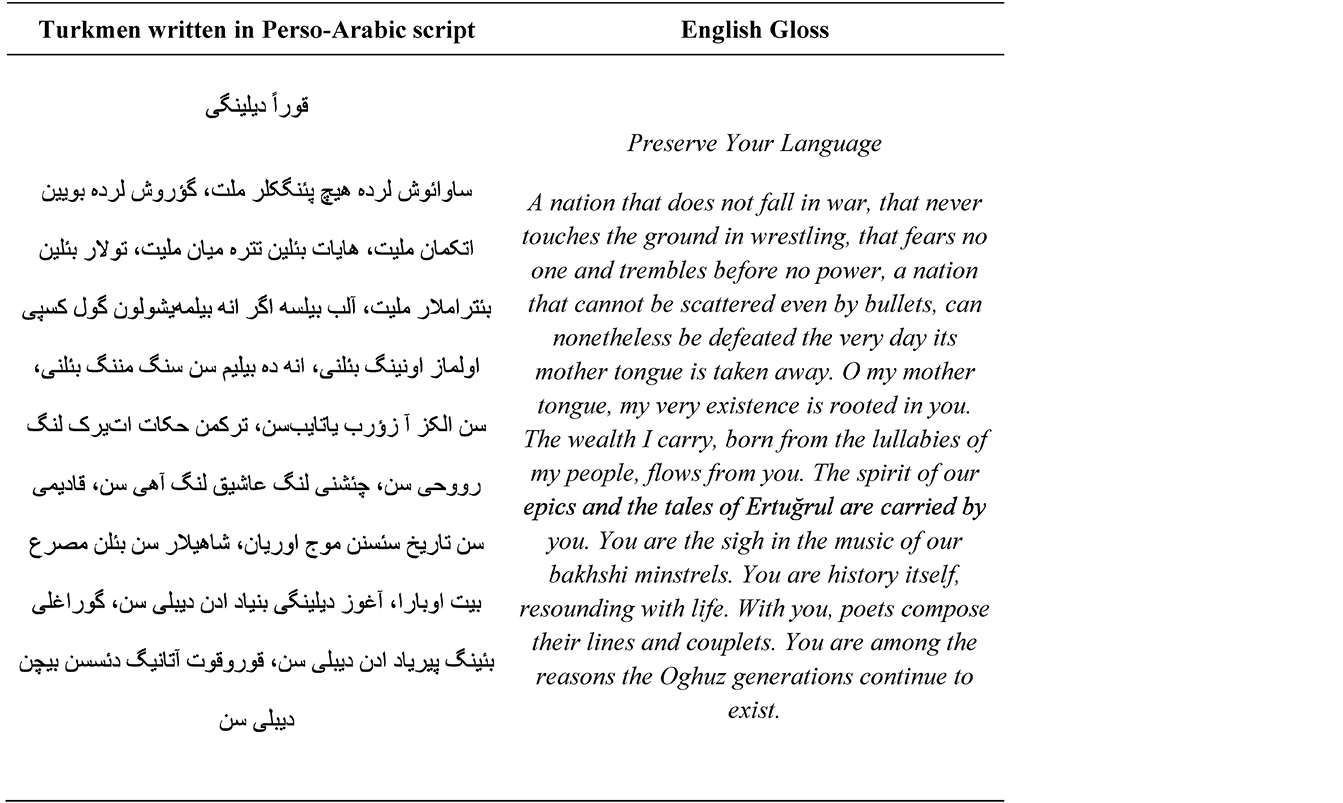

5.2 Turkmen

As the second ethnolinguistic group, and relatively the smallest amongst the other three groups discussed in this article, Turkmens’ grassroots practices show a similar pattern to the Azerbaijani counterparts. Iranian Turkmens reside in the northern and northeastern regions of Iran known as ‘Turkmen Sahra’ encompassing the provinces of Golestan, Razavi Khorasan and North Khorasan, sharing borders with the neighboring country, the Republic of Turkmenistan. Despite sharing some lexical and orthographic similarities with Azerbaijani and both being labeled as a subgroup of the Turkic language family, Turkmen is, to a great extent, different from other Turkic languages of Iran (Bulut 2021). Azerbaijani is a subgroup of the Turkic language family, and speakers share extensive ethnolinguistic features with the Azerbaijanis in the Republic of Azerbaijan (Mirvahedi 2018). Turkmen is an Eastern Oghuz Turkic language spoken by Turkmens in various regions, including Turkmenistan, Iran, Afghanistan, and the North Caucasus (Mirvahedi et al. 2021). The minority languages such as Azerbaijani have, to some extent, been subject to Persian-centric assimilationist policies and ideologies (Mirvahedi 2017). The Turkmen language, sharing borders with and being influenced by language spoken in the Republic of Turkmenistan, has however preserved its traditional features. Religious affiliation is another influential factor in this convoluted process. Most Turkmens are Sunni Muslims while the majority of Iranians, including Azerbaijanis, adhere to Shiite Islam. Shiism is deemed one of the state’s main “ideological pillars” (Kalan 2016: 4), which might have encouraged Turkmens’ sociopolitical separation – a substantial divergence in their linguistic practices – from that of the mainstream government (see Rashidvash 2013). Their scriptal practices, nonetheless, are very similar to their Azerbaijani counterparts. While some use Perso-Arabic script to express their views (Transcription 4 below), others opt for Latin script (Transcription 5 below).

As shown in Transcription 4, Turkmen Instagrammer 4, adopts Perso-Arabic script to voice their heartfelt sentiments about the importance of the Turkmen language. The scriptal model is similar to that of Azerbaijani actors in our representative data. However, they use some words and expressions that reduce Azerbaijani readers’ comprehension of the text. The author is, therefore, exercising a subtle downscaling interactional move from a translocal and general scale to a situated and local one. Their adoption of entrenched lexical patterns demonstrates that, at least, in terms of scripts, they have been less exposed to Persian norms and codes compared to Azerbaijani users.

Turkmen Instagrammer 4.

Turkmen Instagrammer 5 utilizes Latin script (shown in Transcription 5), which is the official script of the Republic of Turkmenistan, Türkiye, and the Republic of Azerbaijan. Thus, they violate the legitimate prevailing norms for writing in Iran’s pro-Perso-Arabic ideology. As such, s/he also invokes a wider audience, arguably other non-Iranian Turks, to be heard. This invocation takes on a social meaning, connecting all Turks and Iranian Turkmens as one ethnolinguistic identity. By doing so, the author metaphorically blurs the geopolitical boundaries that are often demarcated by the choice of script. This blurring, therefore, intertwines distinct Turkic languages and nations to render them as a single, unified pan-Turkic identity.

Turkmen Instagrammer 5.

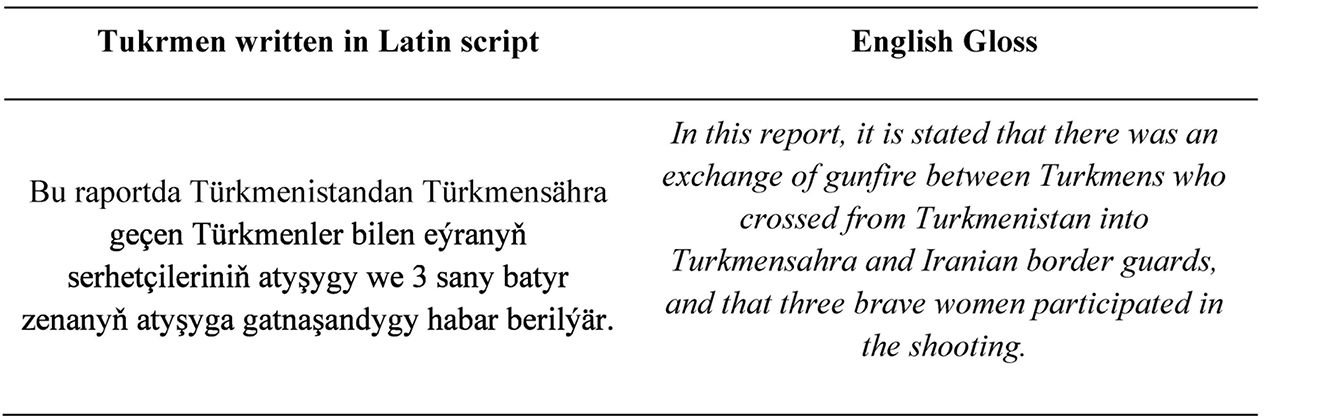

5.3 Kurds

Iranian Kurds reside primarily in western Iran, especially in the provinces of Ilam, Kurdistan, Kermanshah, and parts of West Azerbaijan. Analyzing script choice among Iranian Kurdish Instagrammers reveals a monolithic pattern: the consistent use of a modified Perso-Arabic script. This is not to claim that all Kurds use a unified single script, as literature shows that Kurds residing in Türkiye largely use the Latin-based alphabet, while Kurds in Iran and Iraq continue using an Arabic-based alphabet on the Internet (Sheyholislami 2010). As such, Iranian Kurdish Instagrammers in our dataset debunk trans-scripting, and deploy one variety in writing, which is called the Kurdish alphabet. The Kurdish alphabet is in Perso-Arabic script. However, it has been modified to comprise the letters ڕ /r̠/, ڵ /ɫ/, ۆ /o/, ڤ /v/, وو /uː/, and ێ /eː/ to better represent the Kurdish phonemes that do not exist in Persian.

Transcription 6 below represents three comments from different online identities, all of which are Kurdish speakers. The sample is representative of, almost, all Iranian Kurdish speakers’ orthographical choices on Instagram (see also Sheyholislami 2010). While the Kurds in Türkiye use Latin script to visually express their voices, Kurds in Iraq, Syria, and Iran utilize the ‘Kurdish alphabet’, that is the modified Perso-Arabic orthography (Ahmadzadeh 2018). This orthographical variation might be rooted in the imposition of different institutional policies ratified by each country. While in Iraq, Syria, and Iran, the education system employs (Perso-)Arabic orthography, Türkiye uses Latin script, which has influenced the Kurds residing in the country. For the Iranian Kurds, the modified Perso-Arabic script is the standardized medium for the creation of a written communication channel. Within this channel, there is no space for non-Kurdish alphabets. Their unofficial, indisputable agreement on a Kurdish-only language has two implications: (i) no matter how extensive their linguistic repertoire, interlocutors are encouraged to adopt Kurdish literacy competence; and (ii) a strong downscaling move among Kurds to train individuals to follow localized norms and values. Therefore, for Iranian Kurds, the Kurdish script is a vital discursive representation to express their ideo-political orientations, index their ethnolinguistic identification, and preserve their cultural traditions. For distinction-making purposes from Iranian mainstream Persian speakers, the Kurdish alphabet indexes an indispensable “means of articulating their identity by writing in their language” (Sheyholislami 2010: 302).

Kurdish Instagrammers 6.

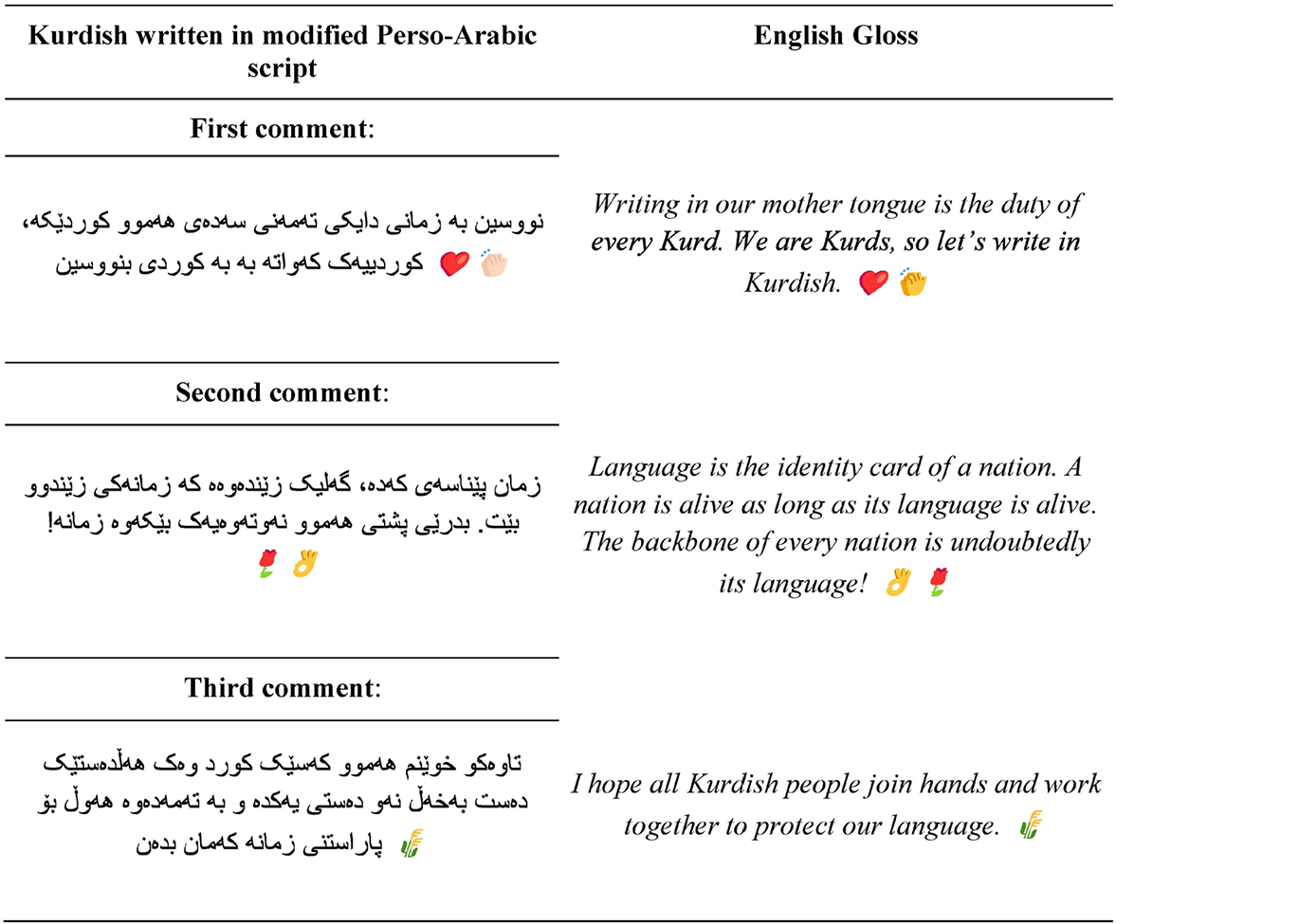

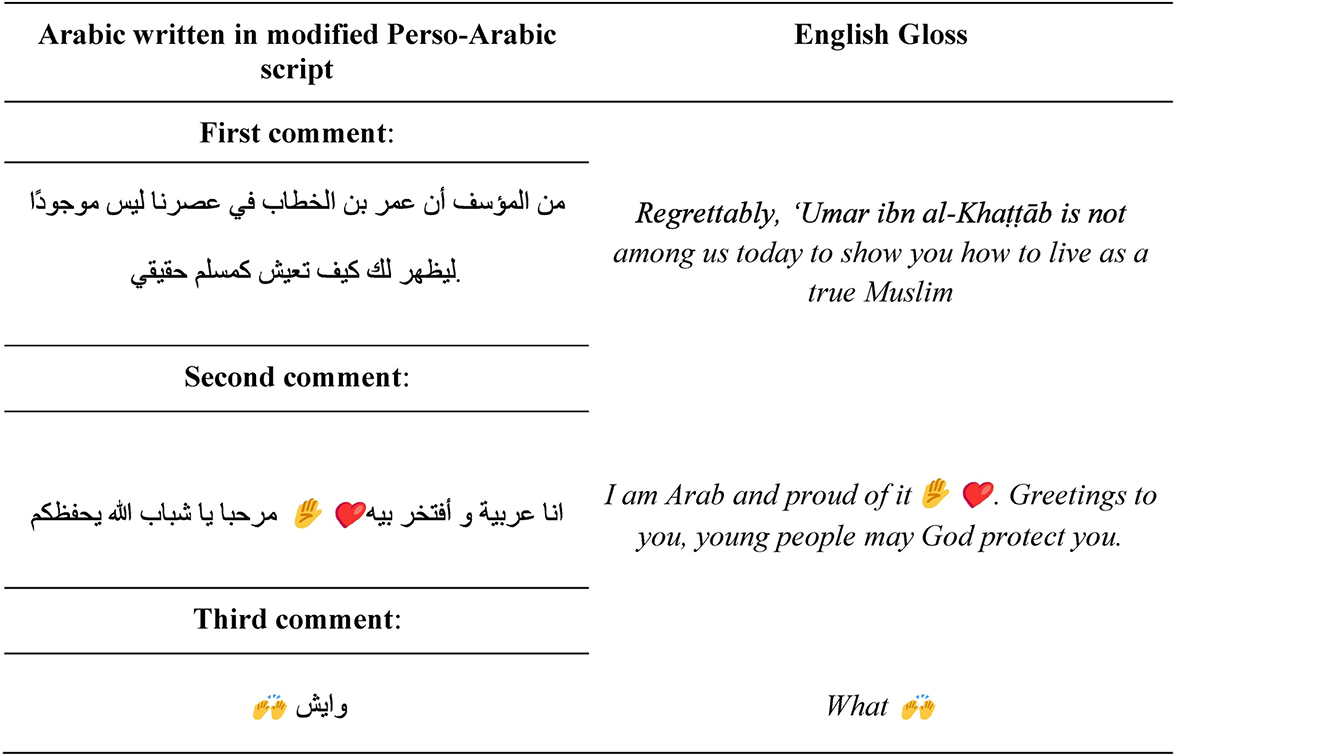

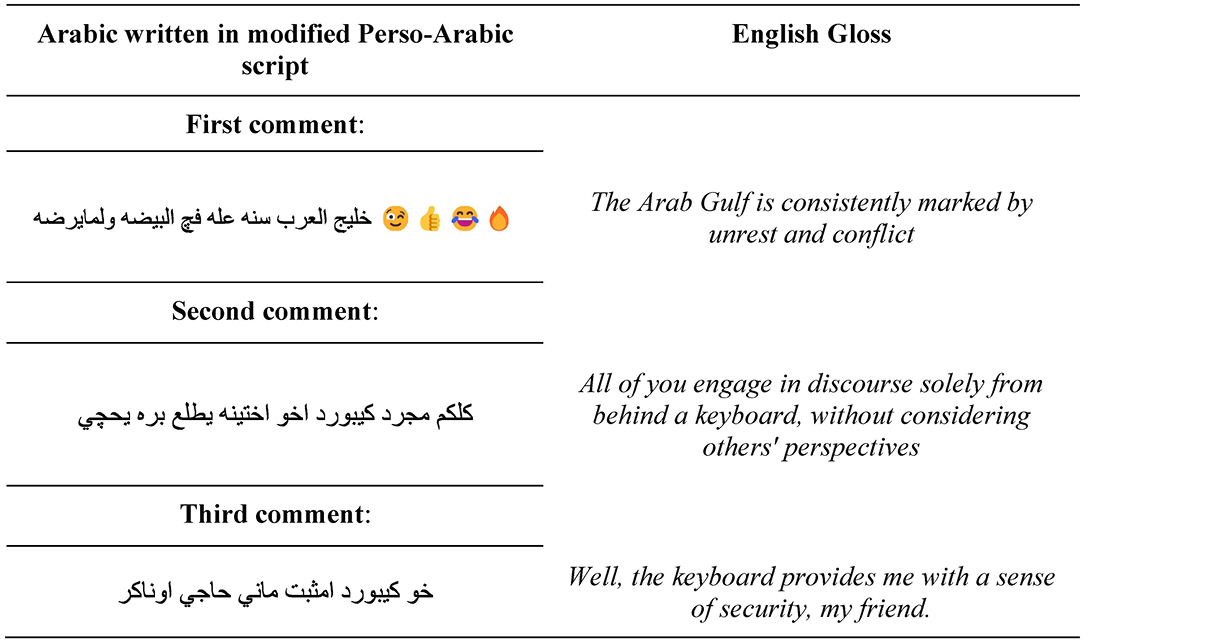

5.4 Arabs

Iranian Arabs, the last group under examination, reside in southwestern Iran, especially in the province of Khuzestan. Iranian Arabs are typically bilingual in Arabic and Farsi. Therefore, when writing, they can write in both languages. When writing in Arabic, however, our analysis of Instagram posts reveals that Iranian Arab users employ two distinct orthographic systems. While the first group adopts the standard Arabic orthographic rules (Transcription 7 below), the second group utilizes a mixture of Arabic and Perso-Arabic rules (Transcription 8 below). Consequently, the second group mixes standard Arabic with the Perso-Arabic letters: پ /p/, چ /tʃ/, ژ /ʒ/, گ /ɡ/, and begets a new self-contracted orthography, a process which we call ‘trans-scripting’.

Arab Instagrammers 7.

As shown in Transcription 7, the Arab Instagrammers in our dataset frequently adhere to the standard Arabic script by omitting the non-Arabic letters: پ /p/, چ /tʃ/, ژ /ʒ/, گ /ɡ/, in their orthographic use. This not only indicates their literacy mastery in the Arabic orthography but also indexes how Iranian Arabs, through the use of the Arabic script, exert their agency to invoke a connection between Iranian Arabs and Arabian Peninsula. They build this connection through access to a linguistic repertoire that belongs to a higher scale–the transnational scale. Therefore, the authors are deliberately performing ‘scale jumping’, meaning that they are shifting from localized and available resources to translocal and scarce resources in order to assert superiority over the nationalized Perso-Arabic script. This invocation takes on social meaning as it differentiates the orthographic practices of Iranian Arabs from those of the Iranian mainstream.

On the other hand, Transcription 8 below is representative of a large number of Iranian Arabs’ self-established norms resulting from the interplay of Arabic and Perso-Arabic writing conventions. Beyond the (un)intentional impairment of both orthographies, this act of conflation among Iranian Arabs calls for a more nuanced scrutiny of the underlying factors behind it. Having said that, literature pinpoints that there is a meaningful link between orthographic variants used and awareness of the users; variants are innately contingent upon the relative state of consciousness (Sebba 2012). This orthographical conflation, however, is ambiguous. It is unclear whether it results from consciousness-induced practices or the repercussions of the intertwined historical developments of the two orthographic systems, compounded by a lack of attempts to make distinctions in the education system. In any case, the current orthographic conflation–whether bewilderment or intentional–warrants further study.

Arab Instagrammers 8.

6 Discussions and conclusion

The current study has provided a historical overview of the politics of writing in Iran, with a particular focus on the orthographic conventions, scriptal choices, and the (un)official orthographic practices. Studying these orthographic practices reveals how language, identity, power, and resistance intertwine in Iran. Through our theoretical frameworks of scale and trans-scripting, we have provided two perspectives – policies implemented and ideal practices envisaged by top-down authorities, and those grassroots practices by bottom-up social actors contesting top-down policies and ideologies through trans-scripting. The significance of this unexplored area is pivotal, particularly with the recognition that diverse language ideologies materialize through orthographic positioning, rendering orthographies as ideologically charged sites for examining how social actors conceptualize language and its confluence with macro factors (Sanei 2022; Schlegel 2012).

A glance at the official policy documents over the past century showed Persian dominance, regardless of what ideo-political orientations Iranian policy-makers hold, is cemented in Iranian society. Despite the official recognition of minority languages and by implication their scripts and orthographies in contemporary Iran, there are still instances of coercive policies preventing the use of minority languages and scripts in official domains (Sheyholislami 2019). Acknowledging that scripts and subjects’ ideological positioning work in tandem, and scripts construct and are constructed by ideologies, we conceptualized scripts as meaning-laden technological tools (Sebba 2012). Hence, focusing on the grassroots practices on Instagram, we presented data from four ethnic minorities, namely Azerbaijanis, Turkmens, Kurds, and Arabs, to depict how local de facto ideologies influence the grassroots orthographical practices.

Across the four groups we analyzed, we found a range of practices in writing, some of which could be arguably interpreted as an act of sociopolitical transgression as they violate the orthographic/scriptal norms envisaged by policymakers. In the case of online actors among Azerbaijanis and Turkmens, for example, Perso-Arabic and Latin alphabets are both commonly used in their writings. As Perso-Arabic delineates a neutral positioning, the choice of Latin, officially used in Türkiye, the Republic of Azerbaijan, and Turkmenistan, “manifests and at the same time constitutes a broader social struggle” (Ahmad et al. 2012: 116), in which all Turks become spatially conflated to establish a united nation. This orthographic act of merging the spatiotemporal boundaries ratifies “a metonymic representative of political and cultural orientation” (Wertheim 2012: 84), wherein abstract ideologies materialize as meaning-laden, thus indexical, orthographies that dismiss and/or collapse the realia of geopolitical distinctiveness. Both groups, despite having difficulties comprehending the other’s words, do so by channeling a nexus between (Turkic) identity, mother tongue, and the symbolic use of the Latin script – associated with westernization, pan-Turkic solidarity, and a form of distancing from Persian or Soviet linguistic legacies (Sebba 2012). These factors function like interlocking components of a mechanism to enable a unified notion of ‘Turkness’. The Latin script, therefore, situates Iranian Azerbaijanis and Turkmens at a transnational scale, evoking a sense of solidarity, ethnolinguistic pride, and belonging for all Turks. Evoking a transnational scale through orthographies, therefore, sidelines local/national scales and their norms and codes, to unite all Turks beyond conventional national borders.

The Kurdish case is interesting as the majority of Iranian Kurds adopt the Kurdish alphabet (i.e. unified Perso-Arabic alphabet) to express their identity (Sheyholislami 2010). Iranian Kurds have formed a standardized Kurdish alphabet whose use is a prerequisite for being verified as a legitimate Kurdish social actor. In other words, adopting historical practices is “linked metaphorically and metonymically to an interest in the cultures, polities, and social realities” of ethnolinguistic identity (Wertheim 2012). In doing so, the majority of Kurdish Instagrammers in this study were found to adopt a counter-hegemonic ideology in which preserving the Kurdish traditions is only viable through contesting or even erasing (Irvine and Gal 2000) the predominant (Persian) nationally circulated discourses. This suggests how the process of identity invocation and valorization is inherently linked to multiple resources–spoken or written–articulated ideologies (Sebba 2012). Deviation from commemorating the old-school norms and practices, here being the adoption of the Kurdish alphabet and language, indexes ‘bad’ Kurdishness, whereas airing and/or policing them bolsters Kurdish identity (Sheyholislami 2010), thereby indexing ‘good’ Kurdishness. Hence, they invoke a sense of sociolinguistic differentiation where non-Kurdish orthography indexes foreignness, whereas Kurdish orthography is a resource that inculcates virtue, glory, and an impeccable ethnolinguistic history (Sheyholislami 2010). In such a ‘Kurdish-laden timespace’, any semiotic deviations from, or attempts to alter, the norms are discredited and illegitimate and, by contrast, the valorization of Kurdish language and identity is regarded as connecting the present generation to an idealized past (Hassanpour 1992).

Finally, we showed how Iranian Arabs are divided into two groups: the first group adheres to the standard Arabic script, while the second group (the majority) adopts trans-scripting, reflecting the second group’s ambiguous positioning between Arabic identity and Persian hegemony. The second group’s orthographic practice also reflects an indexical spectrum, with one end entailing a belonging to Arab identity, and the other end associated with the cross-scalar influence of Persian norms. This spectrum would have remained limited if the social actors did not have access to linguistic repertoires. In other words, through trans-scripting, individuals generate and convert their linguistic repertoires into dynamic written formats as trans-scripts in which several fragments of orthographically similar languages are combined.

Positioning themselves within this contested, norm-disputed complexity, Iranian Arabs on Instagram have improvised a malleable orthography that blurs the boundaries, denaturalizes the omnipresent norms, and merges the deep-seated conventions from both standard Arabic and Perso-Arabic scripts. Trans-scripting delineates how people use their power in specific situations to change how language is used. By doing this, they delicately delegitimize/contravene extant norms to establish new ones, positioning themselves at the center of this new social order. However, conjectures regarding the subjects’ level of awareness in this regard would be a crude, incommensurate treatment. Rather, this unprecedented orthographic manifestation – one might argue, a flexible social practice that undermines canonical understandings of scripts as fixed and discrete codes – can be conceptualized as trans-scripting. In fact, approaching orthographies as insulated social practices, confined as fixed and rigid codes, foregrounds a myopic belief that disempowers the mobility, and descriptive and discursive potential of different orthographical practices employed by fluid social actors. Rooted in translanguaging theory, we contend that, like spoken variation, orthographic representations can reflect fluidity and dynamic practices – what we may term trans-scripting. To borrow Blommaert’s (2010: 95) word, this “localization of normativity” indicates how orthographic norms are not universally fixed but are instead (re)shaped within particular social times-spaces. This challenges the view that scripts are fixed systems and instead presents them as adaptive tools for identity negotiation and political expression. Such practices reflect broader translanguaging ideologies, where writing, like speech, can be dynamic and multi-scalar. This social practice, however, demands more empirically grounded studies to explore its ideological and sociolinguistic underpinnings. By doing so, we might step into the less-explored dimension of orthographic practices to move the field forward and provide a clearer understanding of the underlying reasons behind such reported trans-scripting phenomena.

References

Abrahamian, Ervand. 2008. A history of modern Iran. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Ahmad, Rizwan. 2012. Hindi is perfect, Urdu is messy: The discourse of delegitimation of Urdu in India. Orthography as social action: Scripts, spelling, identity and power 3. 103–133.10.1515/9781614511038.103Search in Google Scholar

Ahmadzadeh, Hashem. 2018. Classical and modern Kurdish literature. In Gülistan Gürbey, Sabine Hofmann & Ferhad Ibrahim Seyder (eds.), Routledge handbook on the Kurds, 90–103. London & New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781315627427-8Search in Google Scholar

Asgharzadeh, Alireza. 2007. Iran and the challenge of diversity: Islamic fundamentalism, Aryanist racism, and democratic struggles. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.Search in Google Scholar

Bani-Shoraka, Helena. 2009. Cross-generational bilingual strategies among Azerbaijanis in Tehran. International Journal of Sociology of Language 198. 105–127.10.1515/IJSL.2009.029Search in Google Scholar

Blommaert, Jan. 2010. The sociolinguistics of globalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo978051184530710.1017/CBO9780511845307Search in Google Scholar

Bolander, Brook & Miriam A. Locher. 2014. Doing sociolinguistic research on computer-mediated data: A review of four methodological issues. Discourse, Context & Media 3. 14–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcm.2013.10.00410.1016/j.dcm.2013.10.004Search in Google Scholar

Boyd, Danah. 2014. It’s complicated: The social lives of networked teens. New Haven: Yale University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Bulut, Christiane. 2021. Turkic languages of Iran. In Lars Johanson & Éva Á. Csató (eds.), The Turkic languages, 287–302. London: Routledge.10.4324/9781003243809-19Search in Google Scholar

Coupland, Nikolas. 2007. Style: Language variation and identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511755064Search in Google Scholar

Dong, Jie & Jan Blommaert. 2009. Space, scale and accents: Constructing migrant identity in Beijing. Multilingua 28(1). 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1515/mult.2009.00110.1515/mult.2009.001Search in Google Scholar

Ess, Charles & the AOIR Ethics Working Committee. 2002. Ethical decision-making and internet research: Recommendations from the AOIR ethics working committee. http://www.aoir.org/reports/ethics.pdf (accessed 29 August 2025).Search in Google Scholar

Handsfield, Lara J. & Thomas P. Crumpler. 2023. Scaling and scalar analysis as a framework for research on teacher learning. The New Educator 19(4). 349–367. https://doi.org/10.1080/1547688x.2023.226925010.1080/1547688X.2023.2269250Search in Google Scholar

Hassanpour, Amir. 1992. Nationalism and language in Kurdistan, 1918–1985. San Francisco: Mellen Research University Press. http://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BA19264216 (accessed 29 August 2025).Search in Google Scholar

Irvine, Judith T. & Susan Gal. 2000. Language ideology and linguistic differentiation. In Paul V. Kroskrity (ed.), Regimes of language: Ideologies, polities, and identities, 35–84. Santa Fe: School of American Research Press.Search in Google Scholar

Jenks, Christopher J. 2024. Circum-Atlantic and global linguistic flows: Language through time and space. Atlantic Studies. 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/14788810.2024.239576210.1080/14788810.2024.2395762Search in Google Scholar

Jongbloed-Faber, Lysbeth. 2021. Frisian on social media. Ljouwert: Fryske Akademy dissertation. https://doi.org/10.26481/dis.20210903lj10.26481/dis.20210903ljSearch in Google Scholar

Kalan, Amir. 2016. Who’s afraid of multilingual education? Bristol: Multilingual Matters.10.21832/9781783096183Search in Google Scholar

Karimzad, Farzad. 2018. Language ideologies and the politics of language: The case of Azerbaijanis in Iran. In Mohammadzaman Djuraeva & François V. Tochon (eds.), Language policy or the politics of language: Re-imagining the role of language in a neoliberal society, 53–75. San Diego: Deep University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Katouzian, Homa. 2009. The Persians: Ancient, mediaeval and modern Iran. New Haven: Yale University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Kia, Mehrdad. 1998. Persian nationalism and the campaign for language purification. Middle Eastern Studies 34(2). 9–36.10.1080/00263209808701220Search in Google Scholar

Landert, Daniela & Andreas H. Jucker. 2011. Private and public in mass media communication: From letters to the editor to online commentaries. Journal of Pragmatics 43. 1422–1434.10.1016/j.pragma.2010.10.016Search in Google Scholar

Lexander, Kristin V. & Jannis Androutsopoulos. 2023. Multilingual families in a digital age: Mediational repertoires and transnational practices. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.4324/9781003227311Search in Google Scholar

MacSwan, Jeff. 2022. Codeswitching and translanguaging. In Salikoko S. Mufwene & Anna M. Escobar (eds.), The Cambridge handbook of language contact, 90–114. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/9781009105965.007Search in Google Scholar

May, Stephen. 2012. Language and minority rights: Ethnicity, nationalism, and the politics of language. London: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Mirvahedi, Seyed Hadi. 2016. Linguistic landscaping in Tabriz, Iran: A discursive transformation of a bilingual space into a monoliqual place. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 242. 195–216.10.1515/ijsl-2016-0039Search in Google Scholar

Mirvahedi, Seyed Hadi. 2017. Exploring family language policy among Azerbaijani-speaking families in the City of Tabriz. In John Macalister & Seyed H. Mirvahedi (eds.), Family language policy in a multilingual world: Challenges, opportunities, and consequences, 92–112. London: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Mirvahedi, Seyed Hadi. 2018. Medical tourism and its niched impact in Tabriz, Iran: Opportunities and challenges for Iranian Azerbaijanis. Linguistic Landscape 4(2). 128–152.10.1075/ll.17032.mirSearch in Google Scholar

Mirvahedi, Seyed Hadi. 2019. Nationalism, modernity, and the issue of linguistic diversity in Iran. In Seyed H. Mirvahedi (ed.), The sociolinguistics of Iran’s languages at home and abroad: The case of Persian, Azerbaijani, and Kurdish, 1–21. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.10.1007/978-3-030-19605-9_1Search in Google Scholar

Mirvahedi, Seyed Hadi & Rasoul Jafari. 2021. Family language policy in the City of Zanjan: A city for the forlorn Azerbaijani. International Journal of Multilingualism 18(1). 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2018.154501910.1080/14790718.2018.1545019Search in Google Scholar

Mirvahedi, Seyed Hadi, Mojtaba Rajabi & Khadijeh Aghaei. 2021. Family language policy and language maintenance among Turkmen-Persian bilingual families in Iran. In Elizabeth Lanza & Ann-Kristin Helland Gujord (eds.), Diversifying family language policy, 191–210. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.10.5040/9781350189928.ch-010Search in Google Scholar

Mocanu, Vasilica, Valeria González & Izaskun Elorza. 2023. The construction of mono- and multilingual identity portrayals on social media: The case of Instagram. Les Cahiers de L’ILCEA 51. https://doi.org/10.4000/ilcea.1725410.4000/ilcea.17254Search in Google Scholar

Moradi, Sanan. 2020. Languages of Iran: Overview and critical assessment. In Stanley D. Brunn & Roland Kehrein (eds.), Handbook of the changing world language map, 1171–1202. Cham: Springer.10.1007/978-3-030-02438-3_137Search in Google Scholar

Otheguy, Ricardo, Ofelia García & Wallis Reid. 2015. Clarifying translanguaging and deconstructing named languages: A perspective from linguistics. Applied Linguistics Review 6(3). 281–307. https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2015-0014.10.1515/applirev-2015-0014Search in Google Scholar

Paul, Ludwig. 1999. “Iranian Nation” and Iranian-Islamic revolutionary ideology. Die Welt des Islams 39(2). 183–217.10.1163/1570060991588551Search in Google Scholar

Pennycook, Alastair. 2010. Language as a local practice. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/978020384622310.4324/9780203846223Search in Google Scholar

Perry, John R. 1982. Āḡā Moḥammad Khan Qājār. Encyclopædia Iranica. http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/aga-mohammad-khan (accessed 29 August 2025).Search in Google Scholar

Phillipson, Robert. 1988. Linguicism: Structures and ideologies in linguistic imperialism. In Tove Skutnabb-Kangas & Jim Cummins (eds.), Minority education: From shame to struggle, 339–358. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.10.2307/jj.33169495.19Search in Google Scholar

Rashidvash, Vahid. 2013. Turkmen status within Iranian ethnic identity (cultural, geographical, political). Research on Humanities and Social Sciences 3(22). 88–93.Search in Google Scholar

Rezaei, Saeed & Ava Bahrami. 2019. Attitudes toward Kurdish in the City of Ilam in Iran. In Seyed H. Mirvahedi (ed.), The sociolinguistics of Iran’s languages at home and abroad: The case of Persian, Azerbaijani and Kurdish, 77–106. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.10.1007/978-3-030-19605-9_4Search in Google Scholar

Sandler, Ronald. 2013. Vignette 3d. Real ethical issues in virtual world research. In Christine Mallinson, Becky Childs & Gerard Van Herk (eds.), Data collection in sociolinguistics: Methods and applications, 58–62. London: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Sanei, Taraneh. 2022. Normativity, power, and agency: On the chronotopic organization of orthographic conventions on social media. Language in Society 51(3). 453–480.10.1017/S0047404521000221Search in Google Scholar

Sanjani, Muhammad Iqwan, Rosalin Gusdian, Nina Inayati & Aniko Hatoss. 2025. Conceptualising a continuum of plurilingual family language policy: A systematic literature review. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2025.250412110.1080/01434632.2025.2504121Search in Google Scholar

Schlegel, Jennifer. 2012. Orthography in practice: A Pennsylvania German case study. In Mark Sebba (ed.), Orthography as social action: Scripts, spelling, identity and power, 177–202. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.10.1515/9781614511038.177Search in Google Scholar

Scollon, Ron & Suzie Wong Scollon. 2003. Discourses in place: Language in the material world. London: Routledge.10.4324/9780203422724Search in Google Scholar

Sebba, Mark. 1998. Phonology meets ideology: The meaning of orthographic practices in British Creole. Language Problems and Language Planning 22(1). 19–47.10.1075/lplp.22.1.02sebSearch in Google Scholar

Sebba, Mark. 2012. Orthography as social action: Scripts, spelling, identity and power. In Mark Sebba (ed.), Orthography as social action: Scripts, spelling, identity and power, 1–19. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.10.1515/9781614511038.1Search in Google Scholar

Shaffer, Brenda. 2002. Borders and brethren: Iran and the challenge of Azerbaijani identity. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.Search in Google Scholar

Sheyholislami, Jaffer. 2010. Identity, language, and new media: the Kurdish case. Language Policy 9. 289–312.10.1007/s10993-010-9179-ySearch in Google Scholar

Sheyholislami, Jaffer. 2012. Kurdish in Iran: A case of restricted and controlled tolerance. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 217. 19–47.10.1515/ijsl-2012-0048Search in Google Scholar

Sheyholislami, Jaffer. 2019. Language as a problem: Language policy and language rights in Kurdistan-Iran. Etudes Kurdes 13. 99–113.Search in Google Scholar

Stornaiuolo, Amy & Robert J. LeBlanc. 2016. Scaling as a literacy activity: Mobility and educational inequality in an age of global connectivity. Research in the Teaching of English 50(3). 263–287.10.58680/rte201728160Search in Google Scholar

Tamleh, Hadis, Saeed Rezaei & Nettie Boivin. 2022. Family language policy among Kurdish–Persian speaking families in Kermanshah, Iran. Multilingua 41(6). 743–767.10.1515/multi-2021-0130Search in Google Scholar

The British Psychological Society. 2021. Ethics guidelines for internet-mediated research. Leicester: The British Psychological Society.Search in Google Scholar

Tohidi, Nayereh. 2009. Ethnicity and religious minority politics in Iran. In Ali Gheissari (ed.), Contemporary Iran: Economy, society, politics, 299–323. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195378481.003.0010Search in Google Scholar

Wei, Li. 2011. Moment analysis and translanguaging space: Discursive construction of identities by multilingual Chinese youth in Britain. Journal of Pragmatics 43(5). 1222–1235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2010.07.035.10.1016/j.pragma.2010.07.035Search in Google Scholar

Wertheim, Suzanne. 2012. Reclamation, revalorization and re-Tatarization via changing Tatar orthographies. In Mark Sebba (ed.), Orthography as social action: Scripts, spelling, identity and power, 65–101. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.10.1515/9781614511038.65Search in Google Scholar

Wikipedia. 2021. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ethnicities_in_Iran (accessed 15 April 2025).Search in Google Scholar

Woolard, Kathryn A. 2020. Language ideology. In James Stanlaw (ed.), The international encyclopedia of linguistic anthropology, 1–21. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell.10.1002/9781118786093.iela0217Search in Google Scholar

Woolard, Kathryn A. & Bambi B. Schieffelin. 1994. Language ideology. Annual Review of Anthropology 23. 55–82.10.1146/annurev.an.23.100194.000415Search in Google Scholar

Yang, Chen. 2021. Research in the Instagram context: Approaches and methods. The Journal of Social Sciences Research 7(1). 15–21. https://doi.org/10.32861/jssr.71.15.2110.32861/jssr.71.15.21Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.