Abstract

In this paper, I explore the changes in international business cycles with quarterly data for the eight largest advanced economies (US, UK, Germany, France, Italy, Spain, Japan, and Canada) since the 1960s. Using a time-varying parameter model with stochastic volatility for real GDP growth and inflation allows their dynamics to change over time, approximating nonlinearities in the data that otherwise would not be adequately accounted for with linear models [Granger, Clive W.J., Timo Teräsvirta, and Heather M. Anderson. 1991. “Modeling Nonlinearity over the Business Cycle.” In NBER book Business Cycles, Indicators and Forecasting (1993), edited by James H. Stock and Mark W. Watson, University of Chicago Press.; Granger, Clive W.J. 2008. “Non-Linear Models: Where Do We Go Next – Time Varying Parameter Models?” Studies in Nonlinear Dynamics and Econometrics 12 (3): 1–11.]. With that empirical model, I document a period of declining macro volatility since the 1980s, followed by increasing (and diverging) inflation volatility since the mid-1990s. I also find significant shifts in inflation persistence and cyclicality, as well as in macro synchronization and even forecastability. The 2008 global recession appears to have had an impact on some of this. I ground my empirical strategy on the reduced-form solution of the workhorse New Keynesian model and, motivated by theory, explore the relationship between greater trade openness (globalization) and the reported shifts in international business cycle. I show that globalization has sizeable (yet nonlinear) effects in the data consistent with the implications of the model – yet globalization’s contribution is not a foregone conclusion, depending crucially on more than the degree of openness of the international economy.

Appendix A

Flattening of the Phillips Curve

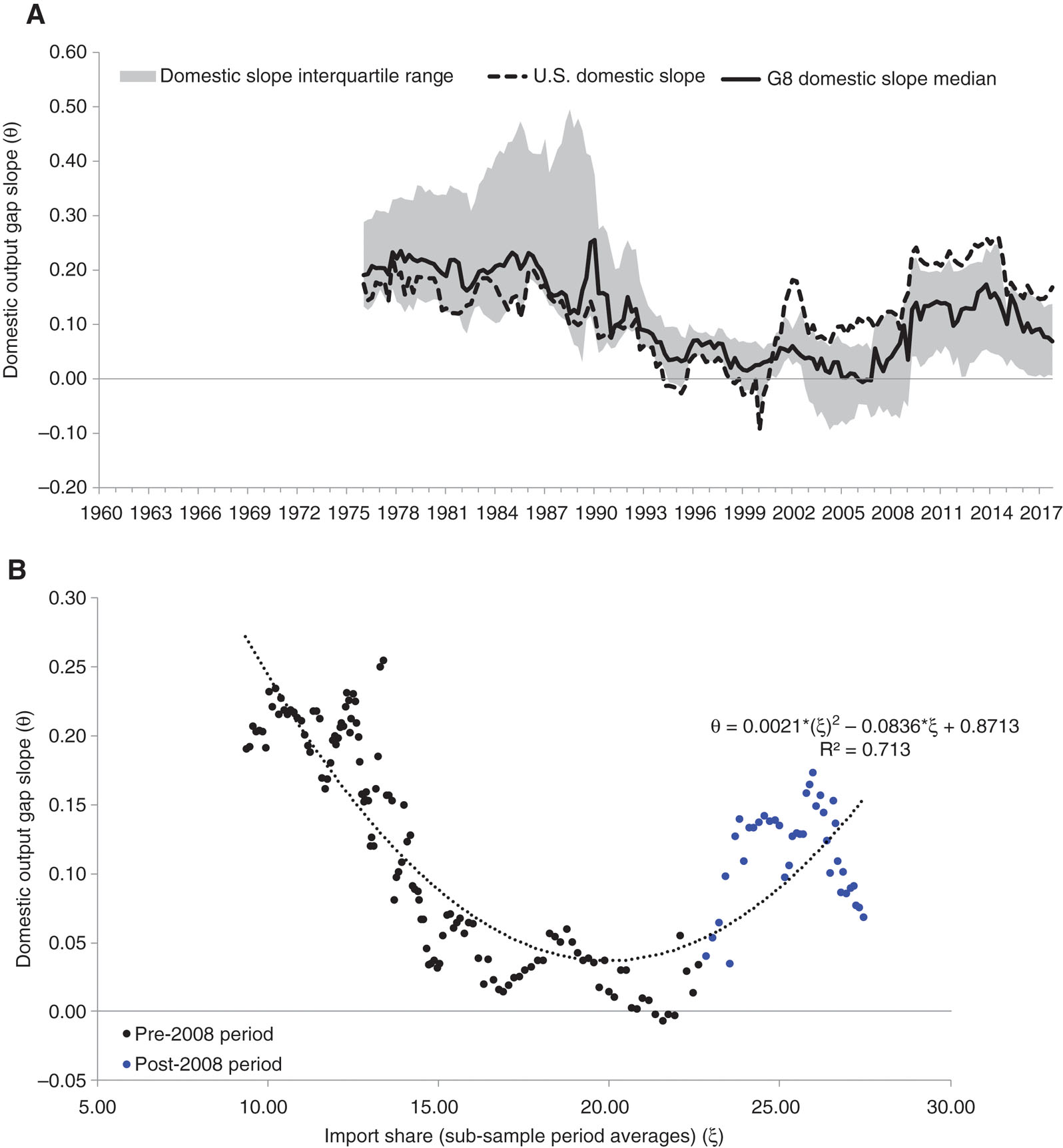

An important part of the debate on globalization has to do with its potential effect on the pricing behavior of firms, on marginal costs, and on the degree of market competition (Sbordone, 2007; Martínez-García & Wynne, 2010; Benigno & Faia, 2016). A key empirical observation that has emerged as central to much of this debate is the perceived “flattening” of the short-run Phillips curve.[16]Roberts (2006), among others, identified a flattening of the Phillips curve for the US starting around 1984 at the onset of the Great Moderation. Figure 10A illustrates the sort of estimates of the coefficient on the domestic output gap that can be found in this strand of the literature, for the eight major advanced economies.

(A) Phillips curve estimated coefficient on domestic output gap.

Note: Median and interquartile range include US, UK, CA, FR, DE, JP, ES, and IT. The figure is based on OLS estimates obtained on a rolling-window basis using the previous 15 years of data and a conventional (closedeconomy) reduced-form Phillips curve specification with four lags on inflation and lagged domestic output gap. The domestic output gap is calculated with the one-sided Hodrick-Prescott filter on log real GDP index in units, expressed in percentages. Sources: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development; author’s calculations.

(B) Slope of the Phillips curve on domestic output gap vs. import share (G8 median).

Note: Includes US, UK, CA, FR, DE, JP, ES, and IT. The OLS estimates for θ are obtained on a rolling-window basis using the previous 15 years of data and a conventional (closed-economy) reduced-form Phillips curve specification with four lags on inflation and lagged domestic output gap. The domestic output gap is calculated with the one-sided Hodrick-Prescott filter on log real GDP index in units, expressed in percentages. The import share is defined as the average over the estimation period of the ratio of real imports of goods and services in percentage over real GDP.

To construct Figure 10A, I use a reduced-form representation of the closed-economy Phillips curve that augments the univariate time series autoregressive specification with domestic output gap (slack), i.e.

In an increasingly more integrated world economy, domestic firms can charge more for their output when they face increases in world demand even if domestic slack remains invariant [a point extensively argued in Martínez-García and Wynne (2010, 2013)]. Therefore, globalization weakens the relationship between inflation and domestic slack. Consistent with that, the empirical evidence shown in Figure 10A indicates that over time inflation has become less responsive to fluctuations in the domestic output gap (θ has declined).[18] The slope estimates appear to have bounced-back since the 2008 global recession – and even earlier for the US.

However, Martínez-García and Wynne (2010) and Martínez-García (2017) as well as the theory laid out in this paper also suggest that one should not expect the flattening of the New Keynesian Phillips curve to be linearly related to measures of increased openness. Interestingly, consistent with the predictions of New Keynesian theory, I find that the estimated slope on the domestic output gap tends to decline with the import share – at least until the data for the post-2008 period gets factored in (as can be seen in Figure 10B).

Inferences based on a reduced-form specification – while often used in practice – are neither very precise nor structural per se and should be taken with a grain of salt. First, data mismeasurement and misspecification problems matter when exploring the relationship between inflation and the output gap [see, e.g. Martínez-García and Wynne (2010) on the impact of filtering output, Ihrig et al. (2010) on trend inflation, Kabukçuoglu and Martínez-García (2016, 2018) on the reliability of global slack indicators, Borio, Disyatat, and Juselius (2017a) on unmodeled shifts in potential, etc.].

For example, using the Hodrick and Prescott (1997) filter on real GDP to compute the output gap – as conventionally done (including for Figure 10A and B) – implicitly imposes a local-linear trend specification on potential and assumes the output gap to be purely transitory white noise.[19] However, those assumptions are inconsistent with the analytic reduced-form solution of the New Keynesian model derived in Section 2. Hence, estimating the flattening of the slope of the Phillips curve poses in practice a joint hypothesis testing problem since it cannot be separated from other modeling assumptions (like those imposed on the unobservable output potential).

Second, there is a body of evidence supportive of the global slack hypothesis both in reduced-form and in more structural settings whereby the relevant trade-off arises between domestic inflation and the global output gap [see, e.g. Borio and Filardo (2007), Binyamini and Razin (2007), Martínez-García and Wynne (2010), Eickmeier and Pijnenburg (2013), Bianchi and Civelli (2015), and Duncan and Martínez-García (2015, 2018) , and Kabukçuoglu and Martínez-García (2016, 2018)]. Hence, to the extent that globalization is a significant force influencing the dynamics of inflation, Phillips-curve-based specifications relying on the domestic output gap alone might be subject to omitted variable biases. Not too surprisingly, Atkeson and Ohanian (2001) and more recently Kabukçuoglu and Martínez-García (2016) and Duncan and Martínez-García (2018) show that backward-looking Phillips curve forecasts of domestic inflation based on domestic output gaps are often found to be inferior against a naïve or univariate time series forecasting benchmark across many different countries – notably during the Great Moderation period.

Third, a number of empirical studies from very early on have challenged the notion that the flattening of the Phillips curve is much related to globalization – reporting mixed results on the relationship between openness and the sensitivity of inflation to the domestic (and even global) output gap over different time periods and across countries [see, e.g. IMF (2006) and IMF (2013), Ball (2006), Pain, Koske, and Sollie (2006), Ihrig et al. (2010), and Milani (2010, 2012)]. Figure 10B illustrates this same point suggesting that the inverse comovement between the import share and the slope of the Phillips curve on domestic slack implied by theory has leveled off or even reversed since 2008.

A more structural approach is warranted because the relationship between the observed variables does not map directly into the slope of the Phillips curve. For instance, the theory laid out in Section 2 suggests a reversal in the correlation between inflation and the output gap can result from a shift towards cost-push shocks (and away from other structural shocks). To conclude, while greater openness can diminish the slope of the Phillips curve on domestic slack as predicted by theory, the nonlinear relationship found in the data is suggestive of other economic forces at play, including possibly shifts in the contribution of the different shocks and even shifts in monetary policy.

References

Ahmed, Shaqhil, Andrew T. Levin, and Beth A. Wilson. 2004. “Recent US Macroeconomic Stability: Good Policies, Good Practices, or Good Luck?” Review of Economics and Statistics 86 (3): 824–832.10.1162/0034653041811662Search in Google Scholar

Amado, Cristina, and Timo Teräsvirta. 2008. “Modelling Unconditional and Conditional Heteroskedasticity with Smoothly Time-Varying Structure.” SSE/EFI Working Paper Series in Economics and Finance 691, Stockholm School of Economics.10.2139/ssrn.1148141Search in Google Scholar

Amado, Cristina, and Timo Teräsvirta. 2013. “Modelling Volatility by Variance Decomposition.” Journal of Econometrics 175 (2): 142–153.10.1016/j.jeconom.2013.03.006Search in Google Scholar

Amado, Cristina, and Timo Teräsvirta. 2017. “Specification and Testing of Multiplicative Time-Varying GARCH Models with Applications.” Journal of Econometrics 175 (2): 142–153.10.1080/07474938.2014.977064Search in Google Scholar

Atkeson, Andrew, and Lee E. Ohanian. 2001. “Are Phillips Curves Useful for Forecasting Inflation?” FRB Minneapolis Quarterly Review (Winter) 25: 2–11.10.21034/qr.2511Search in Google Scholar

Ball, Laurence M. 2006. “Has Globalization Changed Inflation?” NBER Working Papers 12687, National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.10.3386/w12687Search in Google Scholar

Barrell, Roy, and Sylvia Gottschalk. 2004. “The Volatility of the Output Gap in the G7.” National Institute Economic Review 188: 100–107.10.1177/00279501041881008Search in Google Scholar

Benati, Luca, and Paolo Surico. 2008. “Evolving US Monetary Policy and the Decline of Inflation Predictability.” Journal of the European Economic Association 6 (2–3): 634–646.10.1162/JEEA.2008.6.2-3.634Search in Google Scholar

Benati, Luca, and Paolo Surico. 2009. “VAR Analysis and the Great Moderation.” American Economic Review 99 (4): 1636–1652.10.1257/aer.99.4.1636Search in Google Scholar

Benigno, Pierpaolo, and Ester Faia. 2016. “Globalization, Pass-Through, and Inflation Dynamics.” International Journal of Central Banking 2016 (December): 263–306.10.3386/w15842Search in Google Scholar

Bernanke, Ben S. 2004. “The Great Moderation.” speech given at the meetings of the Eastern Economic Association, Washington (DC), February 20. https://www.federalreserve.gov/boarddocs/speeches/2004/20040220/.Search in Google Scholar

Bernanke, Ben S. 2007. “Globalization and Monetary Policy.” speech given at the Fourth Economic Summit, Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research, Stanford, March 2. https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/bernanke20070302a.htm.Search in Google Scholar

Bianchi, Francesco, and Andrea Civelli. 2015. “Globalization and Inflation: Evidence from a Time-Varying VAR.” Review of Economic Dynamics 18 (2): 406–433.10.1016/j.red.2014.07.004Search in Google Scholar

Binyamini, Alon, and Assaf Razin. 2007. “Flattened Inflation-Output Tradeoff and Enhanced Anti-Inflation Policy: Outcome of Globalization?” NBER Working Paper Series (13280).10.3386/w13280Search in Google Scholar

Blanchard, Olivier J., and Jon Simon. 2001. “The Long and Large Decline in US Output Volatility.” Brooking Papers on Economic Activity 2001 (1): 187–207.10.1353/eca.2001.0013Search in Google Scholar

Blanchard, Olivier J., and Jordi Galí. 2007. “The Macroeconomic Effects of Oil Price Shocks: Why Are the 2000s So Different from the 1970s?” In International Dimensions of Monetary Policy, edited by Mark J. Gertler and Jordi Galí, Chicago, USA: University of Chicago Press, 2009.10.2139/ssrn.1008395Search in Google Scholar

Borio, Claudio E. V., and Andrew Filardo. 2007. “Globalisation and Inflation: New Cross-Country Evidence on the Global Determinants of Domestic Inflation.” BIS Working Paper No. 227.10.2139/ssrn.1013577Search in Google Scholar

Borio, Claudio E. V., Piti Disyatat, and Mikael Juselius. 2017a. “Rethinking Potential Output: Embedding Information about the Financial Cycle.” Oxford Economic Papers 69 (3): 655–677.10.1093/oep/gpw063Search in Google Scholar

Borio, Claudio E. V., Piti Disyatat, Mikael Juselius, and Phurichai Rungcharoenkitkul. 2017b. “Why So Low for So Long? A Long-Term View of Real Interest Rates.” BIS Working Papers, no. 685.10.2139/ssrn.3092149Search in Google Scholar

Brock, William A., and Joseph H. Haslag. 2016. “A Tale of Two Correlations: Evidence and Theory Regarding the Phase Shift Between the Price Level and Output.” Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control 67: 40–57.10.1016/j.jedc.2016.03.004Search in Google Scholar

Bry, G., and C. Boschan. 1971. Cyclical Analysis of Time Series: Selected Procedures and Computer Programs. New York, New York: National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER).Search in Google Scholar

Burns, Arthur F., and Wesley C. Mitchell. 1946. Measuring Business Cycles. New York, New York: National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER).Search in Google Scholar

Calvo, Guillermo A. 1983. “Staggered Prices in a Utility-Maximizing Framework.” Journal of Monetary Economics 12 (3): 383–398.10.1016/0304-3932(83)90060-0Search in Google Scholar

Camacho, Maximo, Gabriel Perez-Quiros, and Lorena Saiz. 2006. “Are European Business Cycles Close Enough to Be Just One.” Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control 30 (9–10): 1687–1706.10.1016/j.jedc.2005.08.012Search in Google Scholar

Carlstrom, Charles T., Timothy S. Fuerst, and Matthias Paustian. 2009. “Inflation Persistence, Monetary Policy, and the Great Moderation.” Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 41 (4): 767–786.10.1111/j.1538-4616.2009.00231.xSearch in Google Scholar

Cecchetti, Stephen G., Alfonso Flores-Lagunes, and Stefan Krause. 2005. “Assessing the Sources of Changes in the Volatility of Real Growth.” In The Changing Nature of the Business Cycle, edited by Kent, C. and D. Norman, 115–139. Sydney, Australia: Reserve Bank of Australia.10.3386/w11946Search in Google Scholar

Clarida, Richard, Jordi Galí, and Mark Gertler. 2000. “Monetary Policy Rules and Macroeconomic Stability: Evidence and Some Theory.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 115 (1): 147–180.10.1162/003355300554692Search in Google Scholar

Clarida, Richard, Jordi Galí, and Mark Gertler. 2002. “A Simple Framework for International Monetary Policy Analysis.” Journal of Monetary Economics 49 (5): 879–904.10.1016/S0304-3932(02)00128-9Search in Google Scholar

Crucini, Mario J., and Mototsugu Shintani. 2015. “Measuring International Business Cycles by Saving for a Rainy Day.” Canadian Journal of Economics 48 (4): 1266–1290.10.1111/caje.12146Search in Google Scholar

David, F. N. 1949. “The Moments of the z and F Distributions.” Biometrika 36 (3/4): 394–403.10.1093/biomet/36.3-4.394Search in Google Scholar

Davis, Steven J., and James A. Kahn. 2008. “Interpreting the Great Moderation: Changes in the Volatility of Economic Activity at the Macro and Micro Levels.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 2 (4): 155–180.10.3386/w14048Search in Google Scholar

Duncan, Roberto, and Enrique Martínez-García. 2015. “Forecasting Local Inflation with Global Inflation: When Economic Theory Meets the Facts.” Globalization and Monetary Policy Institute Working Paper no. 235, April.10.24149/gwp235Search in Google Scholar

Duncan, Roberto, and Enrique Martínez-García. 2018. “New Perspectives on Forecasting Inflation in Emerging Market Economies: An Empirical Assessment.” International Journal of Forecasting, Forthcoming. https://www.dallasfed.org/institute/wpapers/2018/0338.Search in Google Scholar

Dynan, Karen E., Douglas Elmendorf, and Daniel Sichel. 2006. “Can Financial Innovation Help to Explain the Reduced Volatility of Economic Activity?” Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy – Journal of Monetary Economics 53 (1): 123–150.10.1016/j.jmoneco.2005.10.012Search in Google Scholar

Eickmeier, Sandra, and Katharina Pijnenburg. 2013. “The Global Dimension of Inflation – Evidence from Factor-Augmented Phillips Curves.” Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics 75 (1): 103–122.10.1111/obes.12004Search in Google Scholar

Fernández, Adriana Z., Evan F. Koenig, and Alex Nikolsko-Rzhevskyy. 2011. “A Real-Time Historical Database for the OECD.” Globalization and Monetary Policy Institute Working Paper no. 96, December.10.24149/gwp96Search in Google Scholar

Fisher, Irving. 1926. “A Statistical Relationship between Unemployment and Price Changes.” International Labor Review 13 (6): 785–792. Reprinted in Fisher, Irving. 1973. “I discovered the Phillips curve: ‘A statistical relation between unemployment and price changes’.” Journal of Political Economy 81 (2): 496–502.10.1086/260048Search in Google Scholar

Galí, Jordi, and Luca Gambetti. 2009. “On the Sources of the Great Moderation.” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 1 (1): 26–57.10.3386/w14171Search in Google Scholar

Granger, Clive W.J. 2008. “Non-Linear Models: Where Do We Go Next – Time Varying Parameter Models?” Studies in Nonlinear Dynamics and Econometrics 12 (3): 1–11.10.2202/1558-3708.1639Search in Google Scholar

Granger, Clive W.J., Timo Teräsvirta, and Heather M. Anderson. 1991. “Modeling Nonlinearity over the Business Cycle.” In NBER book Business Cycles, Indicators and Forecasting (1993), edited by James H. Stock and Mark W. Watson, Chicago, USA: University of Chicago Press.Search in Google Scholar

Grossman, Valerie, Adrienne Mack, and Enrique Martínez-García. 2014. “Database of Global Economic Indicators (DGEI): A Methodological Note.” The Journal of Economic and Social Measurement 39 (3): 163–197.10.3233/JEM-140391Search in Google Scholar

Grossman, Valerie, Adrienne Mack, and Enrique Martínez-García. 2015. “A Contribution to the Chronology of Turning Points in Global Economic Activity (1980–2012).” Journal of Macroeconomics 46: 170–185.10.1016/j.jmacro.2015.09.003Search in Google Scholar

Hamilton, James D. 1994. Time Series Analysis. Princeton: Princeton University Press.10.1515/9780691218632Search in Google Scholar

Harvey, Andrew C., and Albert Jaeger. 1993. “Detrending, Stylized Facts and the Business Cycle.” Journal of Applied Econometrics 8 (3): 231–247.10.1002/jae.3950080302Search in Google Scholar

Hodrick, Robert, and Edward C. Prescott. 1997. “Postwar US Business Cycles: An Empirical Investigation.” Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking 29 (1): 1–16.10.2307/2953682Search in Google Scholar

Ihrig, Jane, Steven B. Kamin, Deborah Lindner, and Jaime Márquez. 2010. “Some Simple Tests of the Globalization and Inflation Hypothesis.” International Finance 13: 343–375.10.1111/j.1468-2362.2010.01268.xSearch in Google Scholar

Inoue, Atsushi, and Barbara Rossi. 2011. “Identifying the Sources of Instabilities in Macroeconomic Fluctuations.” Review of Economics and Statistics 93 (4): 1186–1204.10.1162/REST_a_00130Search in Google Scholar

International Monetary Fund. 2006. “How Has Globalization Affected Inflation? (Chapter 3)” In World Economic Outlook, Spring 2006, 97–134. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2016/12/31/Globalization-and-Inflation.Search in Google Scholar

International Monetary Fund. 2013. “The Dog that Didn’t Bark: Has Inflation Been Muzzled or Was it Just Sleeping?” in World Economic Outlook (Chapter 3), April 2013, 79–96. http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2013/01/.Search in Google Scholar

Keating, John W., and Victor J. Valcárcel. 2017. “What’s So Great About the Great Moderation?” Journal of Macroeconomics 51: 115–142.10.1016/j.jmacro.2016.11.006Search in Google Scholar

Kim, Chang-Jin, and Charles R. Nelson. 1999. “Has the US Economy Become More Stable? A Bayesian Approach Based on a Markov-Switching Model of the Business Cycle.” The Review of Economics and Statistics 81: 608–616.10.1162/003465399558472Search in Google Scholar

King, Mervyn, and Sushil Wadhwani. 1990. “Transmission of Volatility Between Stock Markets.” Review of Financial Studies 3: 5–33.10.1093/rfs/3.1.5Search in Google Scholar

Kydland, Finn, and Edward C. Prescott. 1990. “Business Cycles: Real Facts and a Monetary Myth.” Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review 14 (2): 3–18.10.4324/9780203070710.pt6Search in Google Scholar

Kabukçuoglu, Ayse, and Enrique Martínez-García. 2016. “What Helps Forecast US Inflation? – Mind the Gap!” Koç University-TUSIAD Economic Research Forum Working Papers no. 1615.10.24149/gwp261Search in Google Scholar

Kabukçuoglu, Ayse, and Enrique Martínez-García. 2018. “Inflation as a Global Phenomenon--Some Implications for Inflation Modelling and Forecasting.” Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control 87 (2): 46–73.10.1016/j.jedc.2017.11.006Search in Google Scholar

Lubik, Thomas, and Frank Schorfheide. 2004. “Testing for Indeterminacy: An Application to US Monetary Policy.” American Economic Review 94 (1): 190–217.10.1257/000282804322970760Search in Google Scholar

Martínez-García, Enrique. 2015. “The Global Component of Local Inflation: Revisiting the Empirical Content of the Global Slack Hypothesis.” In Monetary Policy in the Context of Financial Crisis: New Challenges and Lessons, edited by William Barnett and Fredj Jawadi, 51–112. Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.10.1108/S1571-038620150000024016Search in Google Scholar

Martínez-García, Enrique. 2016. “A Quantitative Assessment of the Role of Incomplete Asset Markets on the Dynamics of the Real Exchange Rate.” Open Economies Review 27 (5): 945–967.10.1007/s11079-016-9402-3Search in Google Scholar

Martínez-García, Enrique. 2017. “Good Policies or Good Luck? New Insights on Globalization and the International Monetary Policy Transmission Mechanism.” Computational Economics 1–36: 2017.10.24149/gwp321Search in Google Scholar

Martínez-García, Enrique, and Jens Søndergaard. 2009. “Investment and Trade Patterns in a Sticky-Price, Open-Economy Model.” In The Economics of Imperfect Markets. The Effect of Market Imperfections on Economic Decision-Making, edited by Giorgio Calcagnini and Enrico Saltari. Series: Contributions to Economics. Heidelberg: Springer (Physica-Verlag).10.1007/978-3-7908-2131-4_10Search in Google Scholar

Martínez-García, Enrique, and Mark A. Wynne. 2010. “The Global Slack Hypothesis.” Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas Staff Papers, No. 10, September 2010.Search in Google Scholar

Martínez-García, Enrique, and Jens Søndergaard. 2013. “Investment and Real Exchange Rates in Sticky Price Models.” Macroeconomic Dynamics 17 (2): 195–234.10.1017/S1365100511000095Search in Google Scholar

Martínez-García, Enrique, and Mark A. Wynne. 2013. “Global Slack as a Determinant of US Inflation” In Globalisation and Inflation Dynamics in Asia and the Pacific, edited by the Bank for International Settlements, Vol. 70, 93–98. Basel, Switzerland: Bank for International Settlements.Search in Google Scholar

Martínez-García, Enrique, and Mark A. Wynne. 2014. “Assessing Bayesian Model Comparison in Small Samples.” In Advances in Econometrics, Vol. 34 (Bayesian Model Comparison), edited by Ivan Jeliazkov and Dale Poirier. Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.10.1108/S0731-905320140000034006Search in Google Scholar

Martínez-García, Enrique, Diego Vilán, and Mark A. Wynne. 2012. “Bayesian Estimation of NOEM Models: Identification and Inference in Small Samples.” Advances in Econometrics (DSGE Models in Macroeconomics: Estimation, Evaluation, and New Developments), edited by Nathan S. Balke, Fabio Canova, Fabio Milani, and Mark A. Wynne, Vol. 28, 137–199. Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.10.1108/S0731-9053(2012)0000028007Search in Google Scholar

McConnell, Margaret M., and Gabriel Pérez-Quirós. 2000. “Output Fluctuations in the United States: What Has Changed Since the Early 1980s?” American Economic Review 90 (5): 1464–1476.10.1257/aer.90.5.1464Search in Google Scholar

Milani, Fabio. 2010. “Global Slack and Domestic Inflation Rates: A Structural Investigation for G-7 Countries.” Journal of Macroeconomics 32 (4): 968–981.10.1016/j.jmacro.2010.04.002Search in Google Scholar

Milani, Fabio. 2012. “Has Globalization Transformed US Macroeconomic Dynamics?” Macroeconomic Dynamics 16 (02): 204–229.10.1017/S1365100510000477Search in Google Scholar

Pain, Nigel, Isabell Koske, and Marte Sollie. 2006. “Globalisation and Inflation in the OECD Economies.” Economics Department Working Paper No. 524. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Paris.Search in Google Scholar

Phillips, A. William. 1958. “The Relationship between Unemployment and the Rate of Change of Money Wages in the United Kingdom 1861–1957.” Economica 25 (100): 283–299.10.2307/2550759Search in Google Scholar

Primiceri, Giorgio E. 2005. “Time Varying Structural Vector Autoregressions and Monetary Policy.” The Review of Economic Studies 72 (3): 821–852.10.1111/j.1467-937X.2005.00353.xSearch in Google Scholar

Roberts, John M. 2006. “Monetary Policy and Inflation Dynamics.” International Journal of Central Banking 2 (3): 193–230.Search in Google Scholar

Sargent, Thomas J. 1999. The Conquest of American Inflation. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.10.1515/9780691186689Search in Google Scholar

Sbordone, Argia M. 2007. “Globalization and Inflation Dynamics: The Impact of Increased Competition.” In International Dimensions of Monetary Policy, edited by J. Gali and M. Gertler, 547–579. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.10.7208/chicago/9780226278872.003.0011Search in Google Scholar

Shephard, Neil. 1994. “Partial Non-Gaussian State Space.” Biometrika 81 (1): 115–131.10.1093/biomet/81.1.115Search in Google Scholar

Sims, Christopher A., and Tao Zha. 2006. “Were There Regime Switches in US Monetary Policy?” American Economic Review 96 (1): 54–81.10.1257/000282806776157678Search in Google Scholar

Stock, James H., and Mark W. Watson. 2003a. “Has the Business Cycle Changed and Why?” In NBER Macroeconomics Annual 2002, Vol. 17, edited by Mark Gertler and Kenneth Rogoff. MIT Press.10.1086/ma.17.3585284Search in Google Scholar

Stock, James H., and Mark W. Watson. 2003b. “Has the Business Cycle Changed? Evidence and Explanations.” FRB Kansas City symposium, Jackson Hole, Wyoming, August 28–30, 2003.10.3386/w9127Search in Google Scholar

Stock, James H., and Mark W. Watson. 2007. “Why Has US Inflation Become Harder to Forecast?” Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 39 (1): 3–33.10.1111/j.1538-4616.2007.00014.xSearch in Google Scholar

Summers, Peter M. 2005. “What Caused the Great Moderation? Some Cross-Country Evidence.” Economic Review (Third Quarter) Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, 5–32.Search in Google Scholar

Taylor, John B. 1993. “Discretion versus Policy Rules in Practice.” In Carnegie-Rochester conference series on public policy 39, 195–214.10.1016/0167-2231(93)90009-LSearch in Google Scholar

Taylor, John B. 2016. “The Federal Reserve in a Globalized World Economy.” In The Federal Reserve’s Role in the Global Economy, edited by Michael Bordo and Mark A. Wynne. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9781316493595.006Search in Google Scholar

Teräsvirta, Timo. 2012. “Nonlinear Models for Autoregressive Conditional Heteroskedasticity.” In Handbook of Volatility Models and Their Applications, edited by L. Bauwens, C. Hafner and S. Laurent. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken: NJ, USA.10.1002/9781118272039.ch2Search in Google Scholar

Teräsvirta, Timo, and Heather M. Anderson. 1992. “Characterizing Nonlinearities in Business Cycles Using Smooth Transition Autoregressive Models.” Journal of Applied Econometrics 7 (Issue Supplement S1): S119–S136.10.1002/jae.3950070509Search in Google Scholar

Woodford, Michael. 2003. Interest Rate and Prices. Foundations of a Theory of Monetary Policy. Princeton: NJ, USA: Princeton University Press.10.1515/9781400830169Search in Google Scholar

Woodford, Michael. 2010. “Globalization and Monetary Control.” In NBER book International Dimensions of Monetary Policy, edited by Jordi Galí and Mark J. Gertler. University of Chicago Press. Conference held June 11–13, 2007.10.7208/chicago/9780226278872.003.0002Search in Google Scholar

Supplementary Material

The online version of this article offers supplementary material (DOI: https://doi.org/10.1515/snde-2017-0101).

Article note

I dedicate this work to my father, Valentín Martínez Mira, whose inspiration and unwavering support made it all possible. This document has greatly benefited from the outstanding research assistance of Valerie Grossman, from my ongoing work with María Teresa Martínez García, and from many comments/feedback provided by Nathan S. Balke, Christiane Baumeister, Claudio Borio, William A. Brock, Celso Brunetti, Menzie D. Chinn, Mario J. Crucini, Michael B. Devereux, Charles Engel, Andrew Filardo, Marc P. Giannoni, Joseph H. Haslag, Likka Korhonen, Jae Won Lee, Aaron Mehrotra, Jamel Saadaoui, Chiara Scotti, John B. Taylor, Timo Teräsvirta, Fatih Tuluk, Víctor Valcárcel, and Kenneth D. West. I would also like to thank participants at the 3rd International Workshop on Financial Markets and Nonlinear Dynamics (2017), 2018 Spring Midwest Macro Meetings, and 93rd Western Economic Association International annual conference (2018) for helpful suggestions. I acknowledge the support of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas. All remaining errors are mine alone. The views expressed in this paper are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System.

©2018 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Interview

- An Interview with Timo Teräsvirta

- Research Articles

- Nonlinear and asymmetric pricing behaviour in the Spanish gasoline market

- Testing for misspecification in the short-run component of GARCH-type models

- Closed-form estimators for finite-order ARCH models as simple and competitive alternatives to QMLE

- Time-varying asymmetry and tail thickness in long series of daily financial returns

- Modeling changes in US monetary policy with a time-varying nonlinear Taylor rule

- Financial fragmentation and the monetary transmission mechanism in the euro area: a smooth transition VAR approach

- P-star model for India: a nonlinear approach

- Can a Taylor rule better explain the Fed’s monetary policy through the 1920s and 1930s? A nonlinear cliometric analysis

- Modeling time-variation over the business cycle (1960–2017): an international perspective

Articles in the same Issue

- Interview

- An Interview with Timo Teräsvirta

- Research Articles

- Nonlinear and asymmetric pricing behaviour in the Spanish gasoline market

- Testing for misspecification in the short-run component of GARCH-type models

- Closed-form estimators for finite-order ARCH models as simple and competitive alternatives to QMLE

- Time-varying asymmetry and tail thickness in long series of daily financial returns

- Modeling changes in US monetary policy with a time-varying nonlinear Taylor rule

- Financial fragmentation and the monetary transmission mechanism in the euro area: a smooth transition VAR approach

- P-star model for India: a nonlinear approach

- Can a Taylor rule better explain the Fed’s monetary policy through the 1920s and 1930s? A nonlinear cliometric analysis

- Modeling time-variation over the business cycle (1960–2017): an international perspective