Abstract

A teacher’s use of classroom space via embodied movement enacts a specific spatial pedagogy and has a significant impact on the nature of teaching and learning that can take place. The ubiquity and large expenditure in renovating university learning environments have not been accompanied by well-informed research due to a tendency to background embodied movement in pedagogic investigations. This paper explores the semiotic potentials and pedagogic functions of one teacher’s embodied movement in an Active Learning Classroom in a tertiary setting. It maps out the interrelationship of embodied movement and space as an entanglement of materiality and practice, which complements existing research that relates movement to space only in terms of layout and composition. By conducting a nuanced multimodal analysis of one teacher’s co-patterns of movement and speech in a tertiary lesson, this paper finds that co-patterns of embodied movement and speech in the classroom can segment phases of pedagogic discourse into five secondary phases and that these phases congruently enact different types of space to modulate the teacher-student relationship and enact different pedagogic roles. The paper concludes with a discussion of the implication of embodied movement on classroom design and pedagogic practice.

1 Introduction

This paper understands a teacher’s use of classroom space via embodied movement as essentially a communicative and meaning-making practice, entangled in the material design of classroom and constituting important designs for spatial pedagogy (Lim et al. 2012). Concurring with Lim et al. (2012), this paper argues that classroom space takes on its full meaning in conjunction with embodied movement, and it is only through a standpoint of movement that an adequate understanding of classroom space can be developed. Under this theorization, classroom space is seen as a material, semiotic, and social ensemble dynamically produced in embodied movement. A practice perspective is significant because it enables us to understand better what we mean in classroom space through embodied movement. It further prompts us to contemplate the pedagogic motivations for movement choices (e.g., positioning space, stasis duration, movement target) that have been made, thus combining nuanced descriptions and interpretations in analyzing classroom space.

Recent years has witnessed an increasing awareness of the pedagogic role of space (i.e., the built environment) in higher education (e.g., Giroux and Giroux 2004; Kuntz 2009; Wu 2022, 2025; Wu and Ravelli 2022). For instance, Gregory and Urry (1985: 3) discuss the mediatory role of space and claim that “spatial structure is now seen not merely as an arena in which social life unfolds, but rather as a medium through which social relationships are produced and reproduced.” Similarly, Jamieson (2003), Oblinger (2005), and Montgomery (2008) all concur that an institution’s physical environment has significant implications for its teaching and learning practices. In other words, it is widely acknowledged among scholars that space matters pedagogically.

University spaces mediate teaching and learning practices, but at the same time, these spaces are jointly shaped by culture, society, and ideology (Matthews et al. 2011; Webb et al. 2008). In the past, the ideology of teaching as a “transmission of information” was so prevalent that universities’ delivery and assessment systems worldwide were built and designed with this goal in mind (Biggs and Tang 1999: 21). However, the growing integration of communication and information technologies, in combination with the shift to what Bernstein (1996) terms a shift from visible pedagogy to invisible pedagogy, is changing teaching and learning spaces in universities. Contemporary educational philosophies encourage universities to provide spaces that enable communication, collaboration, community building, and more closely catering to individual needs. They call for implicit teaching and have a stakeholder perspective that highlights the agency of all participants in the educational setting (Tobin and Roth 2006). Attention thus turns to issues of comfort, aesthetics, fit-out, and layout, with a need for effective teaching and learning environments in the university to be both functional and visceral (Jamieson 2003: 111).

The emergence of the Active Learning Classroom (hereafter ALC) is a testament to the dynamic nature of pedagogic discourses and the evolving needs of higher education. In the 2000s, as class sizes were increasing worldwide, institutions faced the challenge of providing an interactive and student-centered pedagogic experience while accommodating more students in one classroom at the same time (Baepler et al. 2016). ALCs were designed to meet these demands, offering a solution that could both accommodate increased class sizes and facilitate student-centered pedagogic practice. The construction of ALCs on university campuses has thus become a global initiative, showcasing the innovative spirit of leading universities worldwide (Roderick 2021).

Embodied movement and space are closely related, with movement constituting one aspect of embodied practice in space. Following McMurtrie (2013: 5), movement refers to the physical location of the entire body, which involves dynamic transition and static positioning in space. “As people move, they create a span of spatial text called a promenade, which is constituted of one moment of motion straddled by two moments of stasis” (McMurtrie 2013: iii). In the pedagogic context, a teacher’s head and torso often move together with the entire body, so gaze and body orientation are also considered. In other words, movement in this paper entails bodily transition in space, gaze, and body orientation. The employment of multiple embodied resources in the space constitutes pedagogic design and enacts a specific spatial pedagogy (Lim et al. 2012). Although educational scholars already recognized that a teacher’s movement in the classroom contributes significant elements to the spatial and pedagogic experience (e.g., Lim et al. 2012; Ngo et al. 2022), this type of movement is often seen as dependent on spatial designs such as layout and furniture placement, rather than an independent meaning-making practice. In the pedagogic context, the embodied movement has often been on the margins of scholarly attention, so a limited understanding of its semiotic nature and pedagogic function remains. In light of this, this paper conducts an in-depth investigation of one teacher’s embodied movement in an ALC to facilitate an understanding of the meaning potential of a teacher’s movement in the classroom as a step towards a further understanding of how different movement patterns in space function to realize a particular kind of spatial pedagogy.

2 Literature review: space, pedagogy and embodied movement

The articulation of the spatial turn (Foucault 1986) in postmodern experience has engendered a growing interest in space in academic debates (e.g., Giroux and McLaren 1994; Grossberg 1994). A large body of literature on spatial experience has been developed in social sciences, including its relation to education (e.g., Giroux and Giroux 2004). There is an emerging trend to include the role of space in higher education research (Kuntz 2009); in the words of Edward (2000: vii), “university architecture has a higher mission compared with other architectures” as “the university environment is part of the learning experience, and buildings need to be silent teachers.” Within this field, educative space is no longer “a container of teaching and learning practices” but “a dynamic multiplicity that is constantly being produced by simultaneous practices” (Fenwick et al. 2011: 129). Spatiality, the socio-material effect and the relation of time-space, is “a tool for analysis” (Fenwick et al. 2011: 129).

In the context of higher education, several studies have begun to recognize the importance of physical spaces in teaching and learning practices and explore the social relations involved in this process. For instance, Sommer (1977) understands the arrangements and use of physical space as part of the non-verbal communication system of the classroom. The educational mission of the university is supported by extensive capital expenditure in formal and informal learning spaces. However, the need for more empirical research is urgent and crucial to investigate the interactions between such spaces and pedagogic practices. Learning spaces in the university constitute “complex and dynamic assemblages of material, virtual, and social resources,” involving both people and things (Ravelli 2018: 63). They afford and are mainly enacted by teaching and learning practices. The complexity of learning spaces and their relation with practices in the university make it challenging to describe, evaluate, and improve these spaces in terms of their design and use (Ravelli 2018).

Studies into the semiotic potentials of educative spaces and pedagogic practices offer a rich and inspiring landscape. They understand the interactions between educative spaces and pedagogic practices as communicative. The prevalence of digital technology highlights various forms of communication – images, gestures, sound, movement, etc., in the semiotic landscape and has occasioned a boom in multimodal educational research across different levels (primary, secondary and tertiary) and different subjects (History, Math, English, Biology, etc.; e.g., Bezemer and Kress 2008; Collier 2013; Hashemi 2017; Jones et al. 2020; Kenner 2004; Wu 2024). In this context, classrooms have become an essential site for multimodal discourse analysis. Some critical studies explore how language and body language contribute to knowledge building (e.g., Amundrud 2017, 2019, 2022; Hao and Hood 2019; Hood 2011; Lim and Tan-Chia 2022; Ngo et al. 2022; Wu 2024). Some informative studies investigate how materials contribute to meaning-making across various social contexts (e.g., Jewitt 2006; Lim 2011, 2012; Ravelli and Wu 2022; Wu 2022, 2025).

Social semioticians informed by systemic-functional linguistics (e.g., Han 2022; Maiorani 2020; McDonald 2013; McMurtrie 2017; van Leeuwen 2021) have recently developed different semiotic models of movement, highlighting the relationship between movement and space in meaning-making processes. These models emphasize the intertwined nature of movement structure, semiotic meaning, and context of a situation, which contributes to a systematic understanding of the semiotic potentials of movement. However, these studies primarily focus on dance or visitors’ movement in the museum rather than embodied movement in a pedagogic context.

A significant publication that examines the semiotic potential of classroom space via embodied movement is Lim et al. (2012), which further draws on the concepts of semiotic distance (Matthiessen 2010; Ravelli and Stenglin 2008) and proxemics (Hall 1966). More specifically, Hall (1966), Ravelli and Stenglin (2008), and Matthiessen (2010) suggest in their studies that material distance communicates semiotic distance, which establishes the social relationship between interactive participants. Based on the typical distances as well as the degree of visibility and contact experienced by the participants, Hall (1966) proposes the hypothesis of distance sets and develops four sets of space, namely, public, social-consultative, casual-personal, and intimate spaces. Classroom interaction often takes place within the social-consultative space, indicating a formal and professional relationship between the teachers and students. In order to capture the nuance of the teacher-student relationship, Lim et al. (2012) further subdivide the social-consultative space into four types of space based on the functional use of classroom space, namely, authoritative, personal, supervisory, and interactional spaces. For instance, the authoritative space is where the teacher positions themselves to conduct formal teaching, the personal space is where the teacher prepares the next lesson activity, the supervisory space is where the teacher supervises students’ activities, and the interactional space is where the teacher and students collaborate. Later, Amundred (2017, 2022) highlights the role of material designs in the meaning-making of classroom space and proposes to add a classwork space alongside interactional space. These studies (Amundred 2017; Lim et al. 2012) have recognized that patterns of movement can enact different classroom spaces to construct spatial pedagogy and also emphasize that the construction of classroom space in the classroom is contingent upon the nature of pedagogic activities at stake.

Overall, the above review suggests that few studies combine embodied pedagogic practices with the materiality of learning spaces in their investigations. Even fewer studies include the material, the semiotic, and the social aspects of educative spaces and pedagogic practices simultaneously in their discussions, with their attention essentially turning to issues of human activities and social concerns. Therefore, there is a tremendous social and scholarly need to study how the design and use of educative spaces relate to pedagogic practices in all three aspects. Additionally, more empirical studies need to be conducted to adequately address the entangled relationship between educative space and embodied movement. Finally, the existing studies have yet to explore the semiotic affordance of ALC or examine the semiotic interaction between embodied movement and material resources in ALC.

3 Data, theory and method

3.1 ALC classroom design and its semiotic affordance for movement

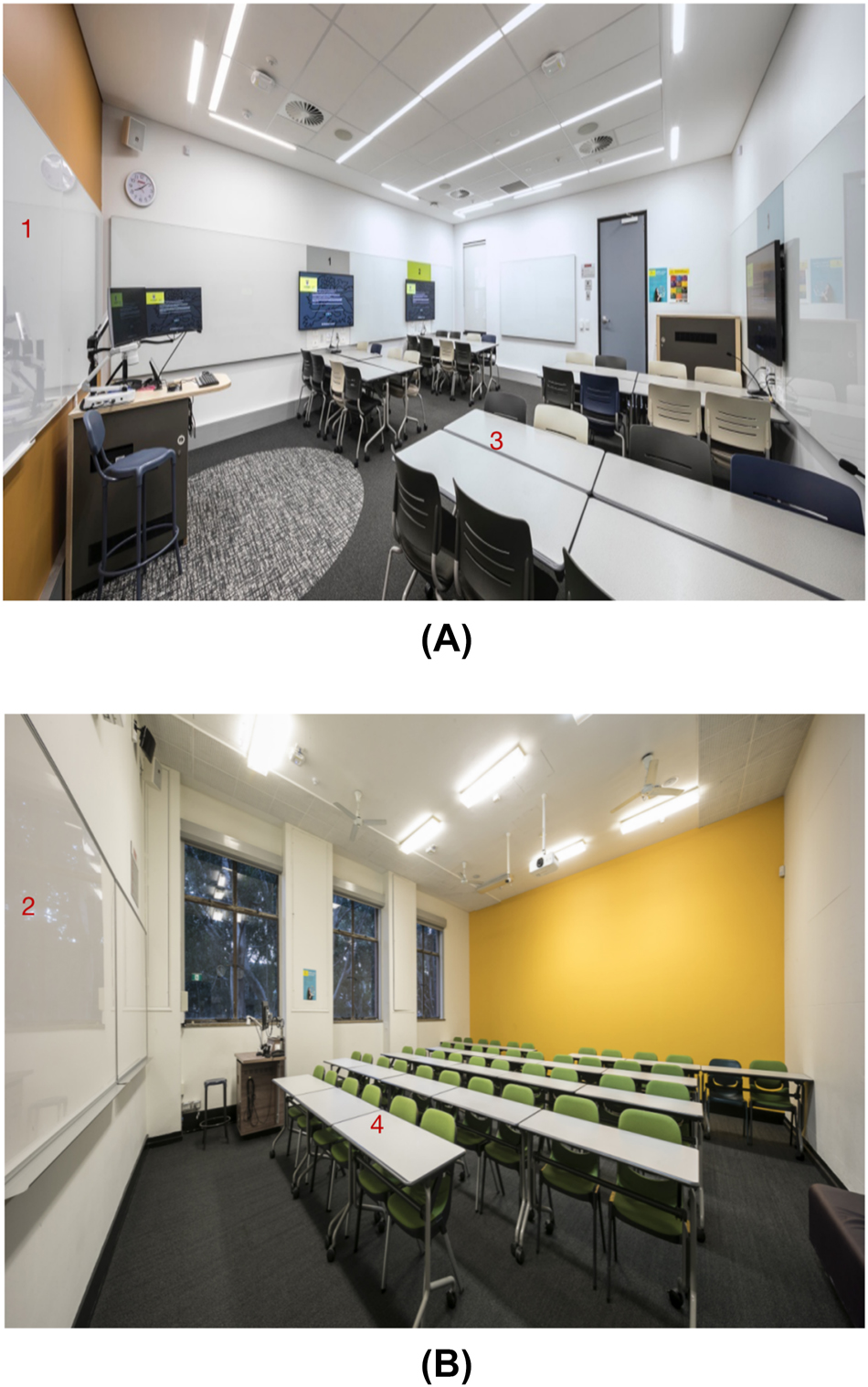

ALC is selected in this paper because, on the one hand, its design reflects a shift in pedagogic discourse at a macro-level to an invisible pedagogy (Bernstein 1996). On the other hand, its spatial designs highlight the movement of people situated in this space. The material design of ALC incorporates digital technology and multimedia facilities, thus demonstrating the potential for a multimodal pedagogy. Compared with traditional teaching classrooms, ALC manifests several specific features. An ALC (see Figure 1 top) typically arranges tables and movable chairs in pods rather than rows as in traditional classrooms (see Figure 1 bottom). This design feature enables the students to sit in groups for collaboration and interaction. In an ALC, the tables are often equipped with whiteboards for brainstorming and are often linked to LED screens. By contrast, a traditional classroom only has one whiteboard and one projector screen placed at the front of the classroom for the teacher’s use. In an ALC, students can project their computer screen to share with the group, or the teacher can select the work of one table to share with the whole class, thus supporting flexible displays of information. There is no clear division of the front or the back to increase mobility for both the teacher and students, again in stark contrast to a traditional teaching classroom with its strong division between the front and the back and between the teacher and students.

Design features of an ALC (top) and a traditional tutorial classroom (bottom). Keys: (1) Interactive whiteboards for both teachers and students; (2) whiteboards only for teachers; (3) nested tables and chairs that support collaboration and bodily movement; (4) tables and chairs in rows.

Because of these design features, it can be quite easy for the teacher to navigate to different places within ALC without any backtracking. The teacher can physically approach all students collectively or individually, regardless of the students’ seating position, and can also face students side-by-side, face-to-face, or face-to-back. However, the teacher cannot face all the students in one pod at once without the students having to turn their bodies. By contrast, in a traditional teaching classroom, the teacher sometimes needs to backtrack through further movements if they want to navigate to different places in the classroom. The teacher can often approach students individually and face them face-to-face or side-by-side, depending on their seating position. Thus, the design of an ALC highlights and supports teacher movement. A comparison of the design features of a traditional classroom and an ALC is given in Figure 1.

This paper focuses on ALC at the University of New South Wales, Sydney (hereafter UNSW). The UNSW ethics committee granted research ethics permission (HC190413) in July 2019, and teachers and students of relevant lessons signed consent forms for their participation in the project, including being filmed in the class. An ALC (see Figure 1) refers to a specific type of physical tutorial classroom at UNSW and is a name[1] given by the Learning Environment Team. So far, 45 million Australian dollars has been invested in this initiative to make invisible pedagogy a norm at UNSW within a few years. Two ALCs were under trial in 2016. There are 85 ALCs out of 220 tutorial classrooms, taking up 38.6 % of tutorial classrooms and covering a wide range of faculties and disciplines, and more are being built. A first-year English course offered by the School of the Arts and Media within the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, as an option within the Bachelor of Arts degree, is chosen for this study because this course is performed in ALCs and based on the researcher’s in situ observations, the teachers and students make full use of the resources afforded in ALCs. The researcher films seven video data documenting teachers’ and students’ use of resources in their pedagogic practice situated in ALCs. Given that analyzing all seven lessons in this paper is not feasible, one filmed lesson is selected. This lesson is dedicated to teaching academic referencing and lasts approximately 80 min. The teacher, John (male), has rich teaching experience and can engage students actively in lesson activities. Information about teaching location and teaching experience is obtained through the UNSW website, and information about student participation and use of resources is obtained through observations in situ.

3.2 Theoretical concepts

One key concept – metafunction, underpinning systemic functional linguistics – is adopted to gain a holistic understanding of the meaning potential made possible by the teacher’s movement in the classroom. The concept of metafunction derives from Halliday (1978), who emphasizes the intrinsic functionality of language, that is, language evolves to satisfy societal needs. This functionality is conceptualized as three types of meaning (Halliday 1978). Ideational meaning involves how individuals construe and interpret reality based on their beliefs, values and assumptions and can be explained in terms of TRANSITIVTY; interpersonal meaning involves social interactions and expressions of emotions, attitudes and norms and can be explained in terms of MOOD and MODALITY; textual meaning refers to the organization of meaning into coherent texts and units, and can be explained in terms of THEME. In addition to language, the concept of metafunction has been widely employed in other semiotic resources such as images (Kress and van Leeuwen 2006), the built environment (Ravelli and McMurtrie 2016; Stenglin 2009), embodied movement (Maiorani 2020; McMurtrie 2017; Wu 2024), etc.

Drawing on curriculum genre theory (Christie 2002) and pedagogic register analysis (Rose 2018), the big and complex lesson is conceptualized as a lesson genre to elucidate that the teachers’ movement in the classroom relates to pedagogy. A lesson genre is realized by lesson stages that are further realized by learning phases. Following Rose (2018), five learning phases constitute a learning cycle: Prepare, Focus, Task, Evaluate, and Elaborate, with Prepare and Elaborate phases being optional. Following Gregory (2002: 321), a phase characterizes a stretch of discourse that exhibits significant consistency and congruity in metafunctional meaning. It is a concept that indicates layers of delicacy, so a primary phase can be segmented into smaller stretches of discourse as secondary and tertiary phases to construe discourse as a process (Gregory 2002). The basis for a phasal analysis is trifunctional information, which includes ideational, interpersonal, and textual meanings (Gregory 2002). Although existing studies (e.g., Gregory 2002) have established the effectiveness of phase in mapping out complex texts and facilitating delicacy of analysis, existing modelling of phase essentially privileges language. This paper proposes that a phase is a multimodal construct and that multiple semiotic resources need to be accounted for when doing a phasal analysis. As such, intersemiotic patterns of movement (entailing gaze and body orientation) and speech are presented, and three types of meaning are discussed in a multimodal phasal analysis in this paper.

3.3 Transcription design

Drawing on Wu (2024), this paper develops transcription designs (see Table 1) to capture semiotic interactions in specific discourse phases, creating an accessible visual experience of co-patterns of movement and speech for the audience. These transcriptions, presented in a tabular layout, with time signified vertically in the columns and semiotic interactions signified horizontally in the rows, are designed to be clear and informative. A diagrammatic visualization technique is devised to signify the formal features of movement, gaze and body orientation. More specifically, a bird’s eye view of the ALC signifies the teacher’s movement trajectory in the classroom. The green arrow signifies motion, with the number signifying the motion duration. The red star signifies the point of stasis, with the number signifying the stasis duration. In addition to the diagrammatic representation, the screenshot is also used, which adds further contextual details to the transcription. In the screenshot, five different arrows signify different features: the pink arrow signifies the student gaze feature, the yellow arrow signifies the body orientation feature of the teacher, the white arrow signifies the teacher gaze feature, the purple arrow signifies the lowering of the teacher’s body, and the blue arrow signifies the occurrence of movement motion. Besides these visualizations, the researcher provides comprehensive verbal explanations in parallel columns, detailing the features of movement, gaze, body orientation and speech within a single phase. These transcription designs aim to allow the audience to clearly “see” how the interaction of different semiotic resources constructs and advances a phase of pedagogic discourse, thereby enlightening them on the intricacies of the process (see Appendix for a list of transcription notations).

Movement realizing the supervising phase.

| Time and phase | Diagrammatic representation and screen-shots | Movement | Gaze and body orientation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 24:37–24:50 supervising |

|

Frequent movements toward the students collectively; brief positioning in student pods | Teacher gaze at the students collectively shifts of body orientation to different groups of students |

|

4 Movement demarcating lesson activities and enacting classroom spaces

This section presents an instance of multimodal analysis, demonstrating the crucial interplay between movement – encompassing gaze and body orientation – and speech in a spatial context. This section meticulously selects one lesson clip conducted in an ALC for an in-depth multimodal analysis, revealing how co-patterns of movement and speech delineate the task phase[2] in this clip into five smaller secondary phases of pedagogic discourse: the supervising phase, the personal phase, the consulting phase, the checking phase, and the conferring phase, each named according to its pedagogic function. Importantly, movement assumes different roles in demarcating the secondary learning phases. In the supervising and personal phases, movement is constitutive; in other words, it is primarily movement patterns that differentiate the two phases. Conversely, movement assumes an ancillary role in the consulting, checking, and conferring phases. In other words, it is primarily the speech patterns that differentiate the different phases.

In addition to delineating a large stretch of pedagogic discourse into five more nuanced lesson activities, these co-patterns of movement and speech also have the potential to enact six types of space: the supervisory space, the personal space, the consulting space, the checking space, the conferring space, and the authoritative space. These spaces dynamically establish and modulate the teacher-student relationship, with each type of space enacting a different teacher role. Notably, although this paper concurs that the semiotic potential of these spaces closely relates to the material designs of the classroom, such as the layout and furniture arrangement (Amundred 2017; Lim et al. 2012), it emphasizes that the nature of learning phases, namely, the pedagogic activities, essentially configures and re-configures the semantics of these spaces. The five secondary learning phases congruently enact five types of classroom space. In other words, the supervising phase enacts the supervisory space, the personal phase enacts the personal space, the consulting phase enacts the consulting space, the checking phase enacts the checking space, and the conferring phase enacts the conferring space. The authoritative space is not enacted in the secondary phases demarcated from the task phase but in the focus and extend phases at a higher level.

This lesson clip revolves around a referencing exercise – Doing Group Exercise on Referencing – in which the teacher encourages the students to actively participate in an academic referencing exercise in groups. This exercise, which forms the core of the lesson, spans approximately 30 min. In the clip, the teacher initiates the activity by dividing the students into groups and providing them with a table to fill in the required information from their readings about American indie films.[3] The students discussed the table together and identified the information required. Students were sometimes unclear about the task or particular concepts in film studies, so they raised their hands and asked the teacher for help. As students were doing the exercises, the teacher moved around each pod to supervise their work. At times, he went to an individual student and provided explanations if requested; at times, he moved to different student groups to verbally check if they were clear about the task or positioned himself around the lectern or the box to drink water or mark essays. So, while the students were completing the task, the teacher was also quite busy with different activities related to this process.

4.1 Movement demarcating the supervising phase and the personal phase and congruently enacting the supervisory space and the personal space

The crux of this section lies in the distinction between the personal and supervising phases, which is primarily based on the unique movement patterns observed. These phases, devoid of language, are not mere supplements to other phases, but rather independent secondary phases that recur in the lesson and consume significant time. Moreover, they seem to serve distinct pedagogic functions. To provide a visual representation, this paper illustrates the movement patterns in the supervising phase and the personal phase in Tables 1 and 2.

Movement realizing the personal phase.

| Time and phase | Diagrammatic representation and screen-shot | Movement | Gaze and body orientation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 24:50–24:58 personal |

|

Movement towards an object and away from the students long positioning around the box | Teacher gaze at objects body orientation remaining oblique to students |

|

As shown in Tables 1 and 2, the supervising and personal phases can be distinguished on a metafunctional basis. Ideationally, in the supervising phase, the teacher frequently moves towards the students as a group, occasionally positioning himself in different student pods. By contrast, in the personal phase, the teacher moves towards objects and positions himself around the box for relatively long periods. Interpersonally, in the supervising phase, the teacher directs his gaze at the students as a group and shifts his body regularly towards different groups of students, which indicates an increase in teacher involvement (Kress and van Leeuwen 2006). By contrast, in the personal phase, the teacher often gazes at an object, and his body remains oblique to students, suggesting a decrease in direct teacher involvement. Textually, in the supervising phase, there is a connection between what the teacher does and what the students do, established through the teacher’s transition around the space and gaze shift. In other words, although the teacher and the students are doing different activities, they are still in the same communicative realm. By contrast, in the personal phase, what the teacher does, such as marking assignments, is often irrelevant to the immediate pedagogic activity at stake. No semiotic resource is enacted to tie the teacher and students together in the same communicative realm, so their connection is temporarily broken.[4] Such differences in the co-instantiated patterns of movement and gaze distinguish these two stretches of discourse as distinct phases.

Building on the work of Lim et al. (2012), we can interpret the teacher’s regular use of classroom spaces in the supervising phase as transforming these sites into a supervisory space, thereby enacting a supervisor role. This phase, characterized by silent supervising activities, does not involve language. Lim et al. (2012) draw on Foucault’s (1995: 195) notion of the “panopticon,” whereby if a silent gaze is coupled with the teacher’s positioning behind the students’ backs, it reinforces the teacher’s authoritative role and increases his power by means of invisible surveillance. Similarly, in the personal phase, the teacher’s regular use of classroom space congruently enacts a personal space, indicating a decrease in direct teacher involvement, since what the teacher is doing is not directly relevant to what the students are doing.

4.2 Movement demarcating the consulting phase and the checking phase and congruently enacting the consulting space and the checking space

The consulting and checking phases stand out from the supervising and personal phases in terms of movement patterns and language involvement. In the consulting phase and the checking phase, the teacher initiates the interaction by moving towards the students first and then positioning himself among the student pods for an extended period. In the supervising phase, the teacher frequently moves towards the students as a group, while in the personal phase, the teacher moves towards the object first and then positions himself in the lectern or around the box for a long time. In the consulting phase and the checking phase, language is actively involved and plays a significant role in shaping the lesson activities, while in the supervising phase and the personal phase, language is not as prominently involved.

The movement patterns are similar in the consulting and the checking phases. There is one slight difference in movement patterns: in the consulting phase, the teacher often moves towards individual students, whereas in the checking phase, the teacher more often moves towards the students as a group. In both phases, the teacher shifts his gaze between the students and the document, and the students shift their gazes between the teacher and the document. In both phases, the teacher lowers his body to minimize the height difference and to enact level gaze, which indicates an effort to reduce power difference (Kress and van Leeuwen 2006). Transcriptions of movement and speech in the consulting and checking phase are illustrated in Tables 3 and 4.

Movement and speech realizing the consulting phase.

| Time and phase | Diagrammatic representation and screen-shot | Movement | Gaze | Speech |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20:37–21:56 consulting |

|

Movement towards an individual student positioning among the student pod | Teacher gaze shifting between the students and the document; student gaze shifting between the teacher and the document teacher lowering his body to minimize height difference and to enact level gaze | S2: So what are we, what are we doing? I don’t really get it. I am sorry T: That’s fine. I will come back … T: So what do you do is the three of you just choose one of these to look up, pre-1970s, xx 1980s Indie… S2: OK. So we are just grabbing information from the source. We are gonna have to source it? T: You need to go to the readings. And you need just to put in the page of it … T: …So you can save this for the main points |

|

||||

|

Movement and speech realizing the checking phase.

| Time and phase | Diagrammatic representation and screen-shot | Movement | Gaze | Speech |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21:56–22:29 checking |

|

Movement towards the students as a group positioning among the student pod | Teacher gaze shifting between the students and the document; student gaze shifting between the teacher and the document the teacher lowering his body to minimize the height difference and to enact level gaze | T: Is everyone clear of the task? Ss: Yes, we are fine T: You are doing good, good T: You know what you are doing? Ss: We understand. T: You understand, yeah, cool |

|

||||

|

Although movement patterns in the consulting and checking phases are quite similar, there are distinct metafunctional differences that distinguish them as separate phases. Ideationally, the consulting phase essentially realizes three types of entity (Hao 2020; Martin and Rose 2007): thing entities – indie film and readings; people entities – I, we, and you (referring to the teacher and students); and semiotic entities – information and main points. The ideational meaning here is realized mainly by material and relational processes and occasionally by mental processes. By contrast, the checking phase primarily realizes two entities: people entities – you and we (referring to the students) and semiotic entity – task. The ideational meaning here is realized mainly by mental and relational processes and occasionally by material processes. These two phases thus display quite distinct ideational meanings. Interpersonally, the students often initiate the consulting phase, construed as secondary knowers demanding information, while the teacher is construed as a primary knower giving information. The checking phase is the reverse, with the students construed as primary knowers and the teacher construed as secondary knowers, with the teacher and students thus displaying opposite roles concerning information status in these two phases. In the consulting phase, the more common mood choice is Wh-interrogative, while in the checking phase, the more common mood choice is Yes/No interrogative. Thus, in the consulting phase, what is being demanded is specific information, while in the checking phase, what is being demanded is affirmation. Textually, the consulting phase is characterized by marked Themes indicating a shift in lesson activities, whereas in the checking phase, Themes are mainly unmarked. These metafunctional differences distinguish these two stretches of discourse as distinct phases. It is worthwhile pointing out that while there are regular movement patterns instantiated in these two phases, which play a role in distinguishing these two phases from the supervising phase and the personal phase, the language plays a significant role in distinguishing these two phases from each other.

In addition, the teacher regularly uses classroom space in the consulting phase to provide guidance and ensure that the students’ tasks are completed, thus congruently enacting a consulting space. Also, the teacher regularly uses classroom space in the checking phase to monitor the progress of students’ work, thus congruently enacting a checking space.

4.3 Movement demarcating the conferring phase and congruently enacting the conferring space

The conferring phase, with its unique characteristics, holds a significant position among all other secondary phases. The pivotal role of language in shaping the pedagogic activity is a key differentiating factor. This is further exemplified in Table 5, which provides transcriptions of movement, gaze, and speech specific to the conferring phase.

Movement and speech realizing the conferring phase.

| Time and phase | Diagrammatic representation and screen-shot | Movement | Gaze | Speech |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 33:30–34:48 conferring |

|

Long positioning in the student pod and few dynamic movements | A collective gazea at the speaker shifts of gaze synchronous with shifts of speaking turn | … T: But I don’t know what elevates the tension S4: Yeah, I have the same idea. It is like one of my subject. My other subject is about how… S1: I Feel like the show is like. I don’t know if it is Indie… S4: I know immediately the first …was S1: And everyone of us… S4: Yeah. Actually… was the most enthusiastic. She is incredible. Yeah, she is amazing but all my…, she is depressed S1: Oh, that makes sense S5: Yeah … T: I am a researcher too S5: …I think media and arts people have that central. In general … |

|

||||

|

-

aIn this context, this means everyone but the speaker.

As indicated in Table 5, ideationally, movement patterns in the conferring phase resemble those in the consulting and checking phases. All three phases are realized by the teacher’s long positioning in the student pods. However, the conferring phase is distinct from the other two in that, while in the consulting and the checking phase, the teacher moves between different student pods, in the conferring phase, the teacher seldom moves but is frequently positioned at one student pod. Textually, in the conferring phase, there is a collective gaze directed at particular speakers, and the shift in gaze is synchronous with the shift in speaking turns, which indicates a constant shift of the centre of attention. In contrast, in other phases, the centre of attention is mainly on the teacher.

Regarding language patterns, ideationally, in the conferring phase, there are three types of entities: thing entities – film and subject; people entities – she (referring to a female scholar), researcher, and media and arts people; semiotic entities – idea and experience. The ideational meaning is mainly about comparing different disciplines and evaluating a specific female scholar, which does not relate directly to the academic referencing exercise. By contrast, the other phases directly discuss the academic referencing exercise. As such, the ideational meanings realized by the conferring phase differ from the other phases. Interpersonally, in the conferring phase, all speakers are construed as primary knowers who give information: in other words, all have the same epistemological status, whereas in the other phases, there is a difference in information status between the teacher and the students. Textually, in the conferring phase, multiple speakers participate simultaneously in verbal communication, and the exchange of information flows quite naturally with almost no trace of institutional protocols or conventions, which resembles the model of casual conversation proposed by Eggins and Slade (1997). In the other phases, exchanges are often structured as pairings of question and answer, while in the conferring phase, the exchanges seem less structured than in the other phases.

In the conferring phase, a conferring space is construed through the teacher’s regular use of the classroom space. Following Hall’s (1966) work on distance sets, the teacher-student relationship is conventionally modelled as social-consultative. However, it could be argued that, in the conferring phase, the nature of the teacher-student relationship is temporarily modulated towards casual-personal. The decrease in the physical distance between the teacher and the students and the lack of difference in information status between them in this phase seems to suggest such.

Another type of classroom space identified by Lim et al. (2012), authoritative space, is also found in the selected clip. However, this space is not enacted in the secondary phases but rather in the focus and extend phases. The authoritative space is also enacted intersemiotically: the teacher moves away from the students and positions himself at the front of the classroom, directs his gaze at the students, and uses speech to extend knowledge or initiate a task. The authoritative space is often mapped onto the front of the classroom or the lectern, which are conventionally associated with teacher authority. Arguably, these movement choices in the focus and extend phases can reinforce the teacher’s authoritative role and his epistemological status.

4.4 Summary

To sum up, a detailed multimodal phasal analysis finds that movement and speech function together in the pedagogic context to demarcate a large stretch of the task pedagogic discourse into five secondary phases: the supervising phase, the personal phase, the consulting phase, the checking phase and the conferring phase. In addition, through movement patterns in the supervising and personal phases, two different spaces are congruently enacted: the supervisory space and the personal space. In the supervisory space, a supervisor role is enacted, and the teacher’s authoritative role is reinforced if the teacher gazes at the students behind their backs in silence. In the personal space, a decrease in direct teacher involvement is signalled. Through co-patterns of movement and speech in the consulting, the checking, and the conferring phases, three other classroom spaces are also congruently enacted – the consulting, the checking, and the conferring spaces. A consultant teacher role is enacted in the consulting space, and a monitor teacher role is enacted in the checking space. In the conferring space, the teacher-student relationship seems to lean towards casual-personal (Hall 1966). Additionally, through co-patterns of movement and speech in the focus or the extended phases, an authoritative space is enacted whereby the authoritative role of the teacher is highlighted. These findings are summarized in Tables 6 and 7 below.

Movement and speech enacting secondary phases.

| Phase distinction | Ideational meaning | Interpersonal meaning | Textual meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| Supervising phase (movement) | Movement: Frequent movements towards the students as a group and occasional positioning in student pods | Movement: Gaze at the students as a group, the shift of body orientations indicating an increase in involvement | Movement: Connection between the teacher and the students via transitions in space and mutual gaze |

| Personal phase (movement) | Movement: Movements towards objects and positioning around the box for a long time | Movement: Gaze at objects and oblique body orientation indicating a decrease in involvement | Movement: Disconnection between the teacher and the students |

| Consulting phase (movement + speech but mainly speech) | Movement: Movement towards individual student first, and then positioning among different student pods for a long time Speech: Three types of entities: Thing entities – indie film and readings; people entities – I, we, and you; semiotic entities – information and main points largely realized by material and relational processes, and occasionally by mental processes |

Movement: Gaze shifting between the students and the document; lowering of the body to minimize height difference and to enact level gaze to reduce power difference Speech: Exchange often initiated by the students; the students as secondary knowers, while the teacher as the primary knower mood choices often realized by Wh-interrogative to demand specific information |

Movement: The center of attention is largely placed on the teacher Speech: A marked theme, pairing of question and answer |

| Checking phase (movement + speech but mainly speech) | Movement: Teacher movement towards students as a group first, and then positioning among different student pods for a long time Speech: Two types of entities: People entities – you and we (referring to students); semiotic entity – task largely realized by mental and relational processes, and occasionally by material processes |

Movement: Gaze shifting between the students and the document; lowering of the body to minimize the height difference and to enact level gaze to reduce power difference Speech: Students as primary knowers while the teacher as the secondary knower often polar mood choices, interrogative to demand affirmation |

Movement: The center of attention largely placed on the teacher Speech: an unmarked theme, pairing of question and answer |

| Conferring phase (movement + speech but mainly speech) | Movement: Long positioning at one student pod Speech: Thing entities – film and subject; people entities – she (referring to a female scholar), researcher, and media and arts people; semiotic entities – idea and experience information not immediately relevant to the academic task at stake |

Movement: A collective gaze at different speakers Speech: all speakers as primary knowers at the same epistemological level |

Movement: The shift of gaze synchronous with the shift of speaking turns Speech: Multiple speakers simultaneously, natural flow in the exchange of information with almost no traces of institutional conventions, resembling a casual conversation (Eggins and Slade 1997) |

Movement and speech enacting classroom spaces, adapting and extending Lim et al. (2012).

| Classroom space | Lesson activities | Movement pattern | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| Supervisory space | Supervising phase | Silent gaze coupled with the teacher’s positioning behind the students’ backs | A supervisor role reinforcing the teacher’s authoritative role and power by means of invisible surveillance |

| Personal space | Personal phase | Movement towards objects and then positioning around the lectern or the box, body orientation remaining oblique to students | A decrease in direct teacher involvement |

| Consulting space | Consulting phase | Movement towards individual student first, and then positioning among different student pods for a long time | A consultant role |

| Checking space | Checking phase | Movement towards the students as a group first, and then positions among different student pods for a long time | A monitoring role |

| Conferring space | Conferring phase | Long positioning at one student pod, and a collective gaze at different speakers | From social-consultative towards casual-personal |

| authoritative space | Focus phase or extend phase | Movement away the students and positioning in the classroom front or the lectern | Reinforcing the teacher’s authoritative role and epistemological status |

5 Discussion and conclusion

Aligning with the increasing demand for studies on the interplay between classroom space and embodied movement, this paper applies the perspective of spatial pedagogy to examine a teacher’s embodied movement in an ALC. Spatial pedagogy underscores the design and use of classroom space in pedagogic practice. The teacher’s choices of co-patterns of movement and speech, entangled in the material resources facilitated in the classroom, are vital to realizing spatial pedagogy. The development of multimodal phasal analysis in this paper provides practical and tangible means for analyzing the complexity and dynamics of meaning-making practices in space. In so doing, this paper provides insights into existing multimodality scholarship, especially the spatial aspects of multimodality, which is still a relatively under-theorized and under-investigated field of research.

By focusing on a specific type of classroom in the tertiary setting – ALCs – this paper deepens our understanding of their usage and potential. The paper also challenges the conventional view of a classroom for active learning that merely focuses on layout and furniture. Instead, it highlights the teacher’s agency in transforming the meanings of these spaces, regardless of their design, thus enabling the enactment of different pedagogies based on the teacher’s multimodal orchestration, namely, the teacher’s capacity to adapt and utilize various semiotic resources in the classroom.

More specifically, through multimodal analyses of the teacher’s bodily movement through space, this paper has demonstrated that co-patterns of movement and speech in the classroom can create different types of meaning and affect pedagogy: (1) movement and speech can demarcate a large stretch of task pedagogic discourse into more specific lesson activities – the supervising phase, the personal phase, the consulting phase, the checking phase, and the conferring phase; (2) movement and speech can enact six types of classroom space to modulate the teacher-student relationship – the supervisory space, the personal space, the consulting space, the checking space, the conferring space and the authoritative space. The above phasal analysis also indicates that phase is a multimodal construct rather than just a linguistic accomplishment. Such an analysis reveals how a non-verbal semiotic resource such as movement in the pedagogic context can play a role in constructing or segmenting phases of pedagogic discourses, which raises questions about the existing modellings of phase on a purely linguistic basis. The analysis also suggests that movement depends on other semiotic resources, such as speech and gaze, to make meaning in the pedagogic context. However, the movement also simultaneously establishes the meaning of speech and gaze, indicating the co-dependent and interactive nature of meaning-making in multimodal texts. The intertwined nature of the movement, speech, gaze, and body orientation in the pedagogic context further mandates the incorporation of intersemiosis, that is, the coordination of different semiotic resources, in investigating multimodal classroom interaction.

These findings align with Jewitt’s (2008: 262) view that how a teacher uses classroom space can produce silent pedagogic discourse. However, they also move it forward by providing systematic descriptive tools to analyze and demonstrate how such silent pedagogic discourse is construed, thus facilitating a more robust analysis of classroom space. Also aligning with Lim et al. (2012) and Amundred (2017), the findings suggest that the teacher’s choices of movement patterns, such as positioning place, stasis duration, and motion orientation, constitute pedagogic design and enact a spatial pedagogy. However, the paper also extends their proposal by demonstrating how movement patterns can enact different pedagogic styles (e.g., interactive, authorial, engaging, etc.) and enable the teacher to realize their diverse pedagogic functions (e.g., knowledge building, tuning student attention, etc.). Additionally, the identification of the consulting, checking, and conferring spaces within Lim et al.’s (2012) interactional space modulates the teacher-student relationship at a more nuanced level, thus adding further delicacy to their modelling of classroom space. Finally, the explicit presentation of the congruent relationship between the secondary learning phase and classroom space in multimodal phasal analysis demonstrates with concrete semiotic evidence how co-patterns of movement, speech and other material resources are entangled and interacting with each other in the enactment of spatial pedagogy. The same material space, for instance, student pods, can be enacted and transformed into different classroom spaces (e.g., the supervisory space, the checking space, the consulting space, etc.) in the unfolding of the learning phases. This paper reinforces Lim et al.’s (2012) and Amundred’s (2017) assertion that the semantics of classroom space are contingent upon the nature of pedagogic practice, highlighting the dynamic and fluid nature of classroom space and the complexity of pedagogic discourse.

The analysis also shows that although the designs of ALC claim to promote a student-centred pedagogy whereby dynamism, equality and engagement are highlighted, the actual use of this classroom in a specific lesson shows that there is still a certain degree of hierarchy between the teacher and students (e.g., the enactment of an authorial pedagogic style at a particular phase of the lesson). To some extent, this type of classroom fails to achieve pedagogic outcomes as anticipated in the institutional promotional discourse. Although this paper does not evaluate the effectiveness of different pedagogic styles, it does suggest an urgent need to attend to the multimodal aspects of communication in the classroom to undermine the multimodal ignorance prevalent in existing design and use of classrooms. The difference between the designed classroom and the performed classroom demonstrates that there is nothing intrinsic about a classroom space that pre-determines its nature of pedagogy. Instead, classroom space is dynamically constructed in pedagogic practice by agentive teachers and students. This difference further suggests that when analyzing classroom space, we cannot simply assign its meaning solely based on its designed feature. Instead, we need to return to the dynamics of practice that is empirically observable, to the agentive role of teachers and students that actively produce space, and to the material entities that underpin the existence of such space.

Movement studies in this paper can also have practical implications, whereby movement is treated as meta-kinetic or meta-signs to inform education. As Wu emphasizes (2024: 26), theorizing movement as choice and making these choices explicitly available to teachers and students can facilitate better pedagogic experience, because once these choices are transformed from subconscious into conscious awareness, teachers and students can develop movement into their lesson design and make more informed and strategic use of movement. The detailed movement analysis above shows the potential to inform pedagogy: (1) movement can enrich the pedagogic experience by demarcating more specific learning activities; (2)movement can adjust the teacher-student relationship and enact multiple pedagogic roles. Based on observations in situ, novice teachers particularly need to fully understand the semiotic potential of movement in the classroom because they often hesitate to move themselves in the classroom (Wu 2024). Additionally, movement often collaborates with other semiotic resources, such as speech, to enact spatial pedagogy. As such, teachers and students need to develop their semiotic capacity not only for movement but also for the multimodal orchestration involved in this process; in other words, they need to pay close attention to the coordination of different semiotic resources in the classroom.

The material design of ALC, in theory, provides similar movement opportunities for the teachers and students in those classrooms. However, in the data collected here, there were few instances of students’ movements, so an expansion of the data analyzed might yield further findings. Nevertheless, the semiotic principles devised in this paper can also be applied to students’ movement. Also, movement in the classroom is conditioned by embodied interaction, and movement involves and extends beyond transitions in space or gaze and body orientation to include other parts of the body, such as the torso, hands, arms, head, etc. Extending the analysis to these other body parts might result in more comprehensive findings. Since embodied movement is closely related to spatial designs, comparing movement in different spaces might also be interesting to investigate how specific spatial arrangements configure movement possibilities and how movement and space mean together.

Funding source: Fundamental Research Fund for the Central Universities

Award Identifier / Grant number: SWU2309714

Funding source: Humanities and Social Science Fund of the Ministry of Education of China

Award Identifier / Grant number: 24XJC740007

Funding source: Southwest University Educational Reform Grant

Award Identifier / Grant number: 2023JY081

Acknowledgment

I want to extend my sincere gratitude to Professor Louise Ravelli, Dr. Robert McMurtrie, Dr. Peter White, Associate Professor Susan Hood, and Associate Professor Helen Caple for their insightful comments on an early draft of this manuscript. I am also grateful to Editor-in-Chief Dr. Jamin Pelkey and the anonymous reviewers whose constructive feedback deepens the discussion in this paper.

-

Research funding: This work was supported by Humanities and Social Science Fund of the Ministry of Education of China, under Grant [24XJC740007]; Southwest University Educational Reform Fund, under Grant [2023JY081]; Fundamental Research Fund for the Central Universities, under Grant [SWU2309714].

-

Competing interests: The author reports there is no competing interest to declare.

Appendix: List of acronyms and notations

| ALC | Active Learning Classroom |

| UNSW | University of New South Wales |

|

The point of stasis and the duration of stasis |

|

The point of motion and the duration of motion |

|

The teacher gaze |

|

The student gaze |

|

The teacher movement |

|

The teacher body orientation |

|

The lowering of the teacher’s body |

References

Amundrud, Thomas. 2017. Analyzing classroom teacher-student consultations: A systemic-multimodal perspective. Sydney: Macquarie University PhD dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Amundrud, Thomas. 2019. Applying multimodal research to the tertiary foreign language classroom: Looking at gaze. In Helen Joyce & Susan Feez (eds.), Multimodality across different classrooms: Learning about and through different modalities, 160–177. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9780203701072-11Search in Google Scholar

Amundrud, Thomas. 2022. Multimodal knowledge building in a Japanese secondary English as a foreign language class. Multimodality & Society 2(1). 64–85. https://doi.org/10.1177/26349795221081300.Search in Google Scholar

Baepler, Paul, J. D. Walker, Christopher Brooks, Kem Saichaie & Christina Petersen. 2016. A guide to teaching in the Active Learning Classroom: History, research, and practice. Sterling: Stylus.Search in Google Scholar

Bernstein, Basil. 1996. Pedagogy, symbolic control, and identity: Theory, research, and critique. London: Taylor & Francis.Search in Google Scholar

Bezemer, Jeff & Gunther Kress. 2008. Writing in multimodal texts: A social semiotic account of designs for learning. Written Communication 25(2). 165–195. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741088307313177.Search in Google Scholar

Biggs, John & Catherine Tang. 1999. Teaching for quality learning at university. Buckingham: Open University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Collier, Dianna. 2013. Relocalizing wrestler: Performing texts across time and space. Language and Education 27(6). 481–497. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2012.727831.Search in Google Scholar

Christie, Francis. 2002. Classroom discourse analysis: A functional perspective. London & New York: Continuum.Search in Google Scholar

Edward, Brian. 2000. University architecture. London: Spon Press.Search in Google Scholar

Eggins, Suzanne & Dianna Slade. 1997. Analyzing casual conversation. London: Cassell.Search in Google Scholar

Fenwick, Tara, Richard Edwards & Peter Sawchuk. 2011. Emerging approaches to educational research: Tracing the sociomaterial. New York: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Foucault, Michel. 1986. Of other spaces, Jay Miskowiec (trans.). Diacritics 16(1). 22–27. https://doi.org/10.2307/464648.Search in Google Scholar

Foucault, Michel. 1995. Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison, Alan Sheridan (trans.). New York: Vintage.Search in Google Scholar

Giroux, Henry & Susan Giroux. 2004. Take back higher education: Race, youth, and the crisis of democracy in the post-civil rights era. New York: Palgrave Macmillian.10.1057/9781403982667Search in Google Scholar

Giroux, Henry & Peter McLaren (eds.). 1994. Between borders. London: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Gregory, Michael. 2002. Phasal analysis within communication linguistics: Two contrastive discourses. In David Lockwood, Peter Fries, William Spruiell & Michael Cumming (eds.), Relations and functions within and across languages, 316–346. New York: Continuum.Search in Google Scholar

Gregory, Derek & John Urry. 1985. Introduction. In Derek Gregory & John Urry (eds.), Social relations and spatial structures, 5–27. London: Macmillan.10.1007/978-1-349-27935-7Search in Google Scholar

Grossberg, Lawrence. 1994. Bringing it all back home – pedagogy and cultural studies. In Henry Giroux & Peter McLaren (eds.), Between borders, 374–390. London: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Hall, Edward. 1966. The hidden dimension. New York: Doubleday.Search in Google Scholar

Halliday, Michael. 1978. Language as social semiotic: The social interpretation of language and meaning. London: Edward Arnold.Search in Google Scholar

Han, Joshua. 2022. A social semiotic framework for music-dance correspondence. Sydney: University of New South Wales PhD dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Hao, Jing. 2020. Analysing scientific discourse from a systemic functional linguistic perspective: A framework for exploring knowledge-building in Biology. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781351241052Search in Google Scholar

Hao, Jing & Susan Hood. 2019. Valuing science: The role of language and body language in a health science lecture. Journal of Pragmatics 139. 200–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2017.12.001.Search in Google Scholar

Hashemi, Sylvana. 2017. Socio-semiotic patterns in digital meaning-making: Semiotic choice as indicator of communicative experience. Language and Education 31(5). 432–448. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2017.1305396.Search in Google Scholar

Hood, Susan. 2011. Body language in face-to-face teaching: A focus on textual and interpersonal meaning. In Shoshana Dreyfus, Susan Hood & Maree Stenglin (eds.), Semiotic margins: Meaning in multimodalities, 31–52. London: Continuum.Search in Google Scholar

Jamieson, Peter. 2003. Designing more effective on-campus teaching and learning spaces: A role for academic developers. International Journal for Academic Development 8(1–2). 119–133. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144042000277991.Search in Google Scholar

Jewitt, Carey. 2006. Technology, literacy, and learning: A multimodal approach. London: Routledge Falmer.Search in Google Scholar

Jewitt, Carey. 2008. Multimodality and literacy in school classrooms. Review of Research in Education 32. 241–267. https://doi.org/10.3102/0091732x07310586.Search in Google Scholar

Jones, Pauline, Annette Turney, Helen Georgiou & Wendy Nielsen. 2020. Assessing multimodal literacies in science: Semiotic and practical insights from pre-service teacher education. Language and Education 34(2). 153–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2020.1720227.Search in Google Scholar

Kenner, Charmian. 2004. Becoming biliterate: Young children learning different writing systems. Stoke: Trentham.Search in Google Scholar

Kress, Gunther & Theo van Leeuwen. 2006. Reading images: The grammar of visual design, 2nd edn. London & New York: Routledge.10.4324/9780203619728Search in Google Scholar

Kuntz, Aaron. 2009. Turning from time to space: Conceptualizing faculty work. In John Smart (ed.), Higher education: Handbook of theory and research, 362–395. Berlin: Springer.10.1007/978-1-4020-9628-0_9Search in Google Scholar

Lim, Victor. 2011. A systemic functional multimodal discourse analysis approach to pedagogic discourse. Singapore: National University of Singapore PhD dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Lim, Victor, O’Halloran Kay & Alexey Podlasov. 2012. Spatial pedagogy: Mapping meanings in the use of classroom space. Cambridge Journal of Education 42(2). 235–251. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764x.2012.676629.Search in Google Scholar

Lim, Victor & Lydia Tan-Chia. 2022. Designing learning for multimodal literacy: Teaching viewing and representing. London: Routledge.10.4324/9781003258513Search in Google Scholar

Maiorani, Arianna. 2020. Kinesemiotics: Modelling how choreographed movement means in space. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9780429297946Search in Google Scholar

Martin, James & David Rose. 2007. Working with discourse: Meaning beyond the clause. London: Continuum.Search in Google Scholar

Matthews, Kelly, Victoria Andrews & Peter Adams. 2011. Social learning spaces and student engagement. Higher Education Research and Development 30(2). 105–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2010.512629.Search in Google Scholar

Matthiessen, Christian. 2010. Multisemiosis and context-based register typology: Registeral variation in the complementarity of semiotic systems. In Eija Ventola & Jesus Moya (eds.), The world told and the world shown: Multisemiotic issue, 11–38. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.Search in Google Scholar

McDonald, Edward. 2013. Embodiment and meaning: Moving beyond linguistic imperialism in social semiotics. Social Semiotics 23(3). 318–334. https://doi.org/10.1080/10350330.2012.719730.Search in Google Scholar

McMurtrie, Robert. 2013. Spatiogrammatics: A social semiotic perspective on moving bodies transforming the meaning potential of space. Sydney: University of New South Wales PhD dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

McMurtrie, Robert. 2017. The semiotics of movement in space. London & New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781315640273Search in Google Scholar

Montgomery, Tim. 2008. Space matters: Experiences in managing static formal learning spaces. Active Learning in Higher Education 9(2). 122–138. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469787408090839.Search in Google Scholar

Ngo, Thu, Susan Hood, James Martin, Claire Painter, Bradley Smith & Michelle Zappavigna. 2022. Modelling paralanguage from the perspective of systemic functional semiotics: Theory and application. London: Bloomsbury.Search in Google Scholar

Oblinger, Dianna. G. 2005. Leading the transition from classrooms to learning spaces. DUCAUSE Quarterly 28(1). 14–18.Search in Google Scholar

Ravelli, Louise. 2018. Towards a social-semiotic topography of university learning spaces: Tools to connect use, users, and meanings. In Robert Ellis & Peter Goodyear (eds.), Spaces of teaching and learning: Integrating perspectives on research and practice, 63–81. Berlin: Springer.10.1007/978-981-10-7155-3_5Search in Google Scholar

Ravelli, Louise & Robert McMurtrie. 2016. Multimodality in the built environment: Spatial discourse analysis. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781315880037Search in Google Scholar

Ravelli, Louise & Maree Stenglin. 2008. Feeling space: Interpersonal communication and spatial semiotics. In Gerd Antos & Eija Ventola (eds.), Interpersonal communication handbook of applied linguistics, Vol. 2, 355–393. Berlin: De Gruyter.10.1515/9783110211399.2.355Search in Google Scholar

Ravelli, Louise & Xiaoqin Wu. 2022. History, materiality, and social practice: Spatial discourse analysis of a contemporary art museum in China. Multimodality & Society 2(4). 333–354. https://doi.org/10.1177/26349795221134982.Search in Google Scholar

Roderick, Ian. 2021. Recontextualising employability in the active learning classroom. Discourse 42(2). 234–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2019.1613020.Search in Google Scholar

Rose, David. 2018. Pedagogic register analysis: Mapping choices in teaching and learning. Functional Linguistics 5(1). 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40554-018-0053-0.Search in Google Scholar

Sommer, Robert. 1977. Classroom layout. Theory Into Practice 16(3). 174–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405847709542694.Search in Google Scholar

Stenglin, Maree. 2009. Space odyssey: Towards a social semiotic mode of 3D space. Visual Communication 8(1). 35–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470357208099147.Search in Google Scholar

Tobin, Kenneth & Wolff-Michael Roth. 2006. Teaching to learn: A view from the field. Rotterdam: Sense.10.1163/9789087901646Search in Google Scholar

van Leeuwen, Theo. 2021. The semiotics of movement and mobility. Multimodality & Society 1(1). 97–118. https://doi.org/10.1177/2634979521992733.Search in Google Scholar

Webb, Kathleen, Molly Schaller & Sawyer Hunley. 2008. Measuring library space use and preferences: Charting a path towards increased engagement. Libraries and the Academy 8(4). 407–422. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.0.0014.Search in Google Scholar

Wu, Xiaoqin. 2022. Space and practice: A multifaceted understanding of the designs and the uses of active learning classrooms. Sydney: University of New South Wales PhD dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Wu, Xiaoqin. 2024. Embodied movement as a stratified semiotic mode: How movement, gaze, and speech mean together in the classroom. Text & Talk. https://doi.org/10.1515/text-2023–0164.10.1515/text-2023-0164Search in Google Scholar

Wu, Xiaoqin. 2025. A multimodal framework of pedagogic practices in space. New York: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Wu, Xiaoqin & Louise Ravelli. 2022. The mediatory role of whiteboards in the making of multimodal texts: Implications of the transduction of speech to writing for the English classroom in tertiary settings. In Sophia Diamantopoulou & Sigrid Orevik (eds.), Multimodality in English language learning, 161–175. London: Routledge.10.4324/9781003155300-12Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Signs and Images

- Computer creates a cat: sign formation, glitching, and the AImage

- Spatial pedagogy: exploring semiotic functions of one teacher’s movement in an Active Learning Classroom

- A semiotic analysis of the canonical image macro meme

- From the Socio-cultural

- The beheading of James Foley: a crossing of gazes between East and West

- An allegory of Fama and Historia: rumor studies, collective memory, and semiotics

- Towards the Cultural

- Pour une approche sémiotique de la traduction de la chanson : l’exemple de La chanson des vieux amants de Jacques Brel et de son adaptation turque Şarap Mevsimi

- Beyond “Made in China”: visual rhetoric and cultural functionality in translating the traditional Chinese totem Loong 龙

- Advertising Semiotics

- La marque comme service ayant une vision propre : une approche sémiotique des architectures de marques

- Advertising fragrance through visual and audible information: a multimodal metaphor analysis of perfume commercials

- Brand identity construction through the heritage of Chinese destination logos

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Signs and Images

- Computer creates a cat: sign formation, glitching, and the AImage

- Spatial pedagogy: exploring semiotic functions of one teacher’s movement in an Active Learning Classroom

- A semiotic analysis of the canonical image macro meme

- From the Socio-cultural

- The beheading of James Foley: a crossing of gazes between East and West

- An allegory of Fama and Historia: rumor studies, collective memory, and semiotics

- Towards the Cultural

- Pour une approche sémiotique de la traduction de la chanson : l’exemple de La chanson des vieux amants de Jacques Brel et de son adaptation turque Şarap Mevsimi

- Beyond “Made in China”: visual rhetoric and cultural functionality in translating the traditional Chinese totem Loong 龙

- Advertising Semiotics

- La marque comme service ayant une vision propre : une approche sémiotique des architectures de marques

- Advertising fragrance through visual and audible information: a multimodal metaphor analysis of perfume commercials

- Brand identity construction through the heritage of Chinese destination logos