Abstract

This article delves into two intrinsic tensions present in humor and cartoons: funniness-seriousness and repetition-novelty. The focus is on the perspectives of cartoonists regarding the semiotic and rhetorical resources they put into play to create humor and satire. In this way, the study echoes a key question in semiotics, and particularly in multimodal studies: how image and words interplay in meaning-making. With that aim, a questionnaire was designed and filled out by 100 cartoonists from 22 different countries. The responses were analyzed applying mixed methods (content analysis, non-parametric statistical techniques, and network analysis). Based on the findings, four distinct profiles of cartoonists were identified, ranging from those who prioritize multimodality (the largest group) to those who favor the verbal mode. Cartoonists who prioritize the visual mode and skeptics to humor analysis fall in between. The article also discusses the various rhetorical resources that cartoonists declare to use to create humor, with irony and sarcasm being the most frequent ones, while puns are the least common. The results are examined in relation to the cartoonists’ conceptions of humor, satire, and the cartoon genre, as well as the different dimensions they considered when discussing their humor style. The study contributes to gaining a deeper understanding of the ways cartoonists use image and writing to create humor and satire and sheds light on an under-researched area in this field.

1 Introduction

The act of explaining and analyzing humor has often been likened to dissecting a frog, originating from the Preface of A Subtreasury of American Humor (White and White 1941). Since its introduction, this analogy has been frequently employed by skeptics of humor analysis. As White asserted, jokes may perish, but our admiration for a witty, sharp, and inventive mind tends to endure.

Within the vast array of humorous manifestations, this article focuses on cartoons – more precisely – on cartoonists. Despite the extensive attention cartoons have received in research, studies centered on the authors’ perspectives are notably scarce (Best 1986), and except for a few cases (e.g., Ashfaq and Russomanno 2021; Burlerson MacKay 2016), they go back decades (Ammons et al. 1988; Best 1986; Hynds 1977; Lamb 1996; Riffe et al. 1985). In sum, these studies have predominantly analyzed cartoonists’ perceived editorial roles, ideologies, backgrounds, and their stance on various social issues, by focusing mostly on American samples. Burlerson MacKay (2016) delved into the ethical approaches of political cartoonists, including an analysis of how the 2015 Charlie Hebdo shootings in Paris affected the profession. Ashfaq and Russomanno (2021) examined the influencing factors on political cartoonists by comparing the perspectives of selected cartoonists from Pakistan and the US. Lamb (1996) explored cartoonists and editors’ perceptions regarding the function and freedom of expression within cartooning. Best’s work (1986) established a portrait of political cartoonists’ backgrounds, work environments, perceptions of editorial cartooning as a profession, and their societal roles.

Cartoonists’ perspectives on their creative process, particularly regarding the resources put into play to create humor and satire have been remarkably under-considered. Two intertwined reasons could explain this, both linked to the conception of humor. Firstly, humor is often considered an intuitive intellectual activity. Secondly, surprise and therefore novelty are inherent requirements for humor. While intuition lies opposite to deliberateness and explicitness, surprise and novelty challenge regularity. Notwithstanding, we could not agree more with Defays’ (1996: 52) observation of an intrinsic tension in humor, between “pure repetition (useless) and pure creativity (unthinkable).”[1] For more than a decade, our work has sought to develop a multidimensional system for understanding and analyzing cartoons’ functioning (e.g., Pedrazzini 2012; Pedrazzini and Scheuer 2018, 2019) by putting into test the following general hypothesis: beyond personal styles and cultural features, cartoons constitute a discursive genre and thus, present recurrent transcultural patterns (Pedrazzini 2010).

The aim of this study is to bring to light the semiotic aspects involved in the creation of humor, particularly in relation to cartooning, by exploring the perspectives of the authors themselves. Our guiding questions are: What is cartoonists’ general attitude when asked about their creative process? Do they recognize regular patterns in humor? What are their conceptions on the relationship between image and words in cartoons? Are there any resources they consider more useful for achieving their goals? Our data comes from questionnaires obtained from 100 cartoonists from 22 nationalities across five continents.

Prior to delving into our study, the following two sections aim to problematize the notion of humor underlying many of the cartoonists’ responses, and to characterize the semiotic functioning of cartoons by taking into account frequent humorous resources. Subsequently, we provide a detailed account of our methodological approach, including the procedure, the corpus and the analyses performed. Our findings are then presented with a focus on identifying cartoonists’ semiotic conceptions on the cartoon genre, and the different dimensions considered when referring to their unique humor style. Finally, we discuss our results and outline suggestions for future research.

2 Tensions and perspectives on humor and cartoons

Humor is usually used as a generic term to designate a variety of manifestations aimed at eliciting laughter or smiles. The phenomenon has gained the attention of scholars for centuries. Numerous theories have been formulated to understand and explain humor, traditionally grouped into three main axes (Attardo 1994; Martin and Ford 2018; Raskin 1984). The first and oldest axis is social-philosophical and is centered on the relations between the participants of a humorous act. It is based on the superiority (among those who laugh) and the disparagement (the target) principles (hostility, aggression, triumph, derision; Defays 1996). The second axis is psychoanalytical and focuses, above all, on the author of the humorous act. It is based on the principle of psychic release (sublimation, liberation and economy). The third and most recent axis, rooted in a cognitive perspective, shifts attention to the stimuli that trigger laughter, emphasizing the principle of incongruity. These three groups of theories complement each other and provide a wide, though not exhaustive view of the phenomenon. Other contributions address different aspects of humor (for a comprehensive review, see Martin and Ford 2018), such as the ancient rhetorical approach which conceived laughter as a persuasive resource to move and seduce the audience. Cicero and later Quintilian (see Attardo 1994; Llera 2003) explored the potential of humor in making criticisms more acceptable.

Much has been written about the complexity of defining humor, and both wide and restricted conceptions coexist in the literature. While humor is commonly associated with laughter and funniness, certain forms take on a satirical and critical tone, aimed at drawing attention and raising awareness rather than simply eliciting amusement. The oxymoron “serious humor” (Cross 2011; Flores 2000) reflects that tension and can be better understood by bringing to mind Freud’s (1928) definition of humor as the ability to emotionally distance oneself from painful, disturbing situations through a playful attitude (Gray and Ford 2013). Along this line (relief theories), humor is considered an important regulation mechanism that can help cope with stress and adversity (see Martin and Ford 2018).

The aforementioned tension between funniness/entertainment and seriousness/criticism underlying humor also applies to cartoons as a particular humorous manifestation. Some research has indicated that cartoonists and editors agree that cartoonists’ objectives are both to entertain and stimulate thought, to challenge and provoke (Ammons et al. 1988). Nevertheless, where cartoons are placed between these two poles is not equally perceived: “Cartoonists are less likely to perceive the cartoon as needing to be funny, while their editors strongly believe that cartoon humor is more important than precision” (Ammons et al. 1988: 88).

Another factor regarding this tension is the subgenre of cartoons (Pedrazzini and Scheuer 2018). Press cartoons, based on daily news, demand greater accuracy compared to playful, gag cartoons. In a study on political satire, some interviewed French editors and cartoonists highlighted the importance of factual accuracy and rigorous fact-checking. Cartoonist Pétillon stated that “In my opinion, we must have a fair enough point of view of the situation; only then can we exaggerate” (Pedrazzini 2010: 582) whereas a former editor of the French magazine Le Canard enchaîné, Claude Angéli, said that “objectivity does not exist, honesty does.” Linked to the responsibility to adhere to factual accuracy, the ability to conduct a “good political analysis” was also mentioned by cartoonist Cabu (Pedrazzini 2010: 582), one of the victims of the 2015 Charlie Hebdo attack.

Cartoonists’ expertise has often been associated with cleverness and perspicacity, and along with a witty mind, to the ability to find unusual connections between words, images or ideas (Auboin 1948; Evrard 1996). This association of incompatible elements is the basis of the incongruity principle, eliciting cognitive conflict between what is expected and what actually occurs (e.g., Attardo 1997, 2001; Shultz 1976).

3 Cartoon functioning

From a semiotic perspective, cartoons are condensed visual or multimodal texts, in which iconic, plastic (Groupe µ 1992), and often linguistic signs are combined. Verbal-visual interaction remains nowadays as “arguably the most ubiquitous means of communication” (Martinec and Salway 2005: 337; see also Gross 2009). Barthes’ (1964) pioneer distinctions between anchorage, illustration, and relay have been revised and expanded in multiple studies centered in the vast arc of contemporary discourses and genres (Cohn 2013; Gross 2009; Hoek 2002; Liu and O’Halloran 2009; Martinec and Salway 2005; Ventola and Moya Guijarro 2009; among others). In the specific field of multimodal cartoons, a “conjunction” (Hoek 2002) between visual and verbal modes takes place. Unlike a mere juxtaposition, both modes are closely related. The constituted multimodal text means more than the sum of its constituent elements. In cartoons, image and writing accomplish different roles not only to convey meaning but also to create a humorous effect. A few studies have delved into cartoon modal functioning (e.g., El Refaie 2009, 2013; Pedrazzini and Scheuer 2018, 2019; Tsakona 2009), and distinguished four main relations: complementarity, contradiction, visual, and verbal prevalence. In the first two, image and writing convey novel and meaningful information to create humor. Regarding complementarity, visual and verbal modes converge to one or more related ideas. According to El Refaie (2009: 84, 2010, both modes can “convey a sense of hyperbole, which heightens the perception of incongruity and creates additional humorous meanings.” In the case of contradiction, visual and verbal modes convey deliberately divergent information, which creates a humorous effect. With respect to visual prevalence, writing reinforces or expands some visual aspect. In the case of verbal prevalence, the visual mode accomplishes an illustrative role. Redundancy – which could be subsumed within visual or verbal prevalence – occurs when the same information is provided by both modes, although this occurs only partially, since each mode presents semiotic specificities and affordances (Kress 2010). For instance, the verbal mode may be more apt to represent distant and abstract information. As Amit et al. (2014: 345) posit, “one of the most useful aspects of language is that it allows us to communicate and think about things that are not present.” Words may also present a comparative advantage in conducting logical analysis (Martinec and Salway 2005). Images, on the other hand, may be more suited for creating emotional impact (De Houwer and Hermans 1994; Kensinger and Schacter 2006), and can be more easily recognized across cultures. Even if cultural background does intervene in visual communication, codes are not as restricted as in the verbal mode. In the case of iconic signs based on similarity relationships with the referent, representations are more likely to be understood across cultures.

Cartoons combine simplicity and concision with condensation. Events are interpreted and represented through the lens of social frames that categorize them in order to decrease its complexity (Bouko et al. 2017). A few main ideas are condensed “into one pregnant image” (Gombrich 1963: 130). The power of visual condensation in cartoons is considered one of the reasons for its appeal (Davies 1995; Gombrich 1963). Notwithstanding, cartoons are far from being simple texts (El Refaie 2009). They present a high semiotic density as every single element carries meaning (Keren 2018). Latent, apparent, and literal meanings are interwoven into a complex intertextual unity in which multiple perspectives are called forth: the author’s perspective, the politicians/celebrities’ perspective to which the cartoon refers, the media. The echoing of cultural references such as quotations, proverbs, songs, films, and historical events encourages layered meanings in novel, humorous, and satirical ways (Werner 2004).

Cartoonists deploy a wide variety of humorous resources among which rhetorical figures play a key role (Davies 1995; Falardeau 1981, 2015; Pedrazzini and Scheuer 2019; Stewart 2013). Some common resources in cartoons are metaphor, metonymy, and synecdoche among tropes; puns among figures of meaning; antithesis among figures of construction; paradox, irony, sarcasm, and allusion among figures of thought (Beth and Marpeau 2005; Fromilhague 2005). Many studies have claimed that metaphor is the main resource operating in political cartoons (e.g., El Refaie 2010; Keren 2018; Negro Alousque 2014; Schilperoord and Maes 2009; Werner 2004), by means of which features from a “fictional scene are mapped onto the actual people and events in contemporary politics” (El Refaie 2010: 197). Caricature, as the art of exaggerating or diminishing physical features, has been and still remains a common device in cartoons (Gombrich 2000; Tillier 2005).

4 Methodology

4.1 Procedure and corpus

Over the last decade, we have implemented a questionnaire specifically designed to learn about cartoonists’ backgrounds and perspectives regarding four main axes: educational and professional background, working modality, conceptions of cartoons as a genre, and cartoonists’ view of their own work. The questionnaire was distributed via email individually or through cartoonists’ organizations, including the Federation of Cartoonists (FECO), Le Salon International de la Caricature, du Dessin de Presse et d’Humour (France), and the Cartoon Movement, in either English, French, or Spanish. The questionnaire was completed by 100 cartoonists from 22 countries in five continents (51 % from Europe, 34 % from Latin America, 10 % from North America, 3 % from Asia, and 2 % from Africa). Only six cartoonists are women, which is in line with the prevailing gender representation in the profession (Falardeau 2020).

This article addresses the answers obtained to the following five open and closed-ended questions:

Where do you mainly recognize the humor component in your cartoons?

What are you considered to be mainly based on when creating humor?

Mark with a cross.

On the verbal component.

On the visual component.

On both.

Could you try wording the way in which you use the verbal and the visual components?

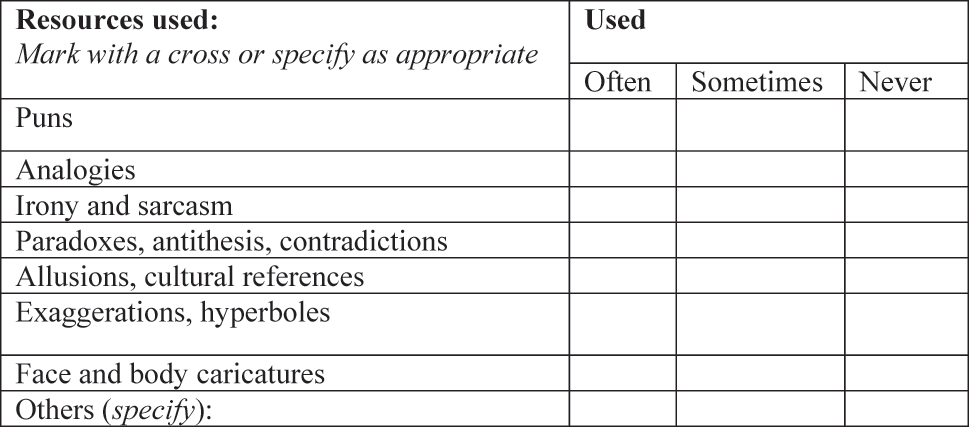

The list below (Figure 1) shows different resources used by cartoonists. Please state how often you use each one of them.

If you use certain resources more frequently, could you write why?

Upon completing the questionnaire, cartoonists were asked to state how they wanted the information provided to be treated: either by authorizing their identification as a cartoonist or by remaining anonymous. Only those who opted to have their identity revealed are identified, while those who chose to remain anonymous have only their country of residence disclosed.

List given to cartoonists to identify resources used.

4.2 Analysis

All participants answered closed-ended question 2 (referred to as Q2), while 99 % of them responded to question 4 (Q4). Open-ended question 1 (Q1) garnered 88 responses (12 participants opted not to answer or provided unrelated responses). Question 3 (Q3) received 86 responses. Question 5 (Q5) was designed as an optional extension of Q4, allowing participants to provide a non-oriented explanation for their chosen resources; 39 cartoonists answered it. Depending on the nature of the questions (either closed- or open-ended) and their content, some specific analyses were applied.

To analyze the responses to open-ended questions 1 and 3, a content analysis was applied combining a deductive and an inductive approach. This involved using theoretical concepts such as modes (visual, verbal, multimodal) and incongruity as a key mechanism, as well as categories from previous studies, such as cartoonist’s motivations (Pedrazzini and Scheuer 2018), to frame some of the information. New categories were created when necessary. The system of categories is presented in the following section.

In order to apply an inter-rater reliability for Q1 and Q3, a set of 20 answers for each question was randomly selected making sure that examples for all categories were present in the sample. A trained coder (Bolognesi et al. 2017) not related to the study was asked to code the 40 answers according to 15 categories (2 categories are specific to Q1, 4 categories are specific to Q3, while 9 are shared categories for both questions: see Table 1). Results were compared and an inter-rater agreement was calculated. For Q1, the agreement was between 85 % and 100 % for 9 out of the 11 coded categories, whereas for Q2, the agreement was 85 % to 100 % for 8 out of the 11 categories. Those categories that obtained a lower inter-rater reliability were revised and their descriptions refined.

Set of all the dimensions and categories identified in the responses analyzed, with their relative frequencies expressed in percentages.

| Dimension | Categories | Q1 (n = 88) | Q3 (n = 86) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conception of humor | 18 % | – | |

| Theme | 26 % | – | |

| Cartoonist’s motivation | 24 % | 6 % | |

| Personal style | 25 % | 21 % | |

| Cartoon profiles | Acknowledging distinctions | 23 % | 23 % |

| Mode | Visual* | 18 % | 8 % |

| Q1: 44 % | Verbal* | 2 % | 8 % |

| Q3: 89 % | Both (multimodal)* | 24 % | 73 % |

| Cartoon attributes | Funny, effective (rapidly and easily understood, concise, simple) | 6 % | 6 % |

| They present a concept, an idea, a message | 13 % | 6 % | |

| Q1: 19 % | An ideal cartoon: solely visual (Un dessin vaut mieux qu’un long discours: ‘A picture is worth a thousand words’) | 2 % | 22 % |

| Q3: 37 % | Visual cartoons are more: international, appealing to the readership, difficult to create when addressing political issues; stronger (impact) | 2 % | 17 % |

| Cartoon functioning | Cartoonists mention specific resources | 25 % | 17 % |

| Q1: 38 % | Incongruity as main mechanism | 15 % | 7 % |

| Q3: 75 % | Visual prevalence | – | 37 % |

| Verbal prevalence | – | 14 % | |

| Complementarity (very rarely, contradiction) | – | 22 % | |

| Difficulty to explain, to analyze | – | 19 % |

-

Except for Mode (see * above), the set of categories are not mutually exclusive. The symbol − expresses the absence of a category in one of the questions. The percentages informed in the column Dimension were calculated considering the identification of at least one of its categories per participant, i.e., even when more than one category from the same dimension was identified in a participant, it was only counted once.

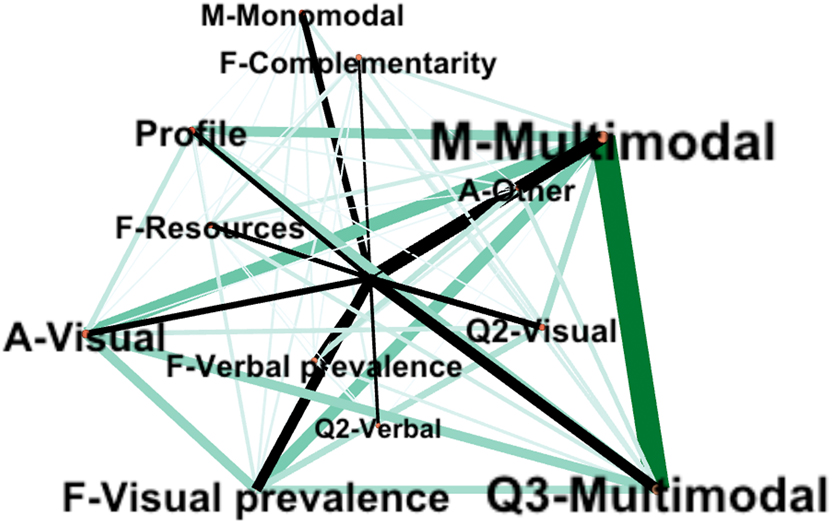

Moreover, a network analysis (Smiraglia 2015) was applied to study the relations between nine categories identified in Q3 corresponding to Cartoon Mode, Functioning, Attributes, and Profiles, and the three categories from Q2 (Verbal, Visual, and Multimodal). A Gephi (open-source and free software) graph was generated.

For Q4, a chi-square test of independence was calculated to examine whether the frequency of resource usage varied depending on the type of resource. Once the null hypothesis was rejected, adjusted residuals (Haberman 1973) were applied to identify cases of under or over-represented resource usage frequencies (≥ +/−2). In the case of Q5, content analysis was applied to identify some recurrent patterns.

5 Results

5.1 Closed-ended questions: use of images, words, and specific resources

With regard to the use of images and words when creating humor (Q2), the large majority of cartoonists (71 %) answered that they were mainly based on both semiotic modes, while 24 % affirmed that they were mainly based on the visual mode and only 5 % on the verbal mode. These results highlight multimodality as the key semiotic trait of cartoons as perceived by cartoonists.

Q4 entailed a more challenging reflection since participants were asked to consider and provide more precise information about the resources used in their work. Figure 2 shows that the most often used resources cartoonists declared to deploy are irony and sarcasm, followed very closely by exaggeration and hyperbole as well as paradox, antithesis and contradictions. It might be surprising that analogy appears only in the sixth place, whereas plenty of empirical studies conceive metaphor as the main resource in political cartoons. This result will be discussed in Section 6.

Frequency in the use of resources declared by the 99 cartoonists that answered Q4. Values are informed in absolute frequencies. The item “no answer” includes those cases in which participants did not select that particular resource.

The chi-square test of independence shows that the frequency in the use of resources declared by cartoonists varies according to the type of resource, χ2 = 61.74, p < 0.001. Adjusted residuals present significant differences in three of them: irony/sarcasm are over-represented in the category Often (Adj. Res. = 2.3), analogy is over-represented in the category Sometimes (Adj. Res. = 2.6), and pun is over-represented in the categories Sometimes (Adj. Res. = 3) and Never (Adj. Res. = 4.26).

Puns are the most common resources linked to verbal humor. This may be one of the reasons for its association to the absence of use (Never) since we have learned that a quarter of the cartoonists expressed that they mainly based their work on visual humor.

Cartoonists had the opportunity to add more resources to the ones listed. Eleven of them mentioned one or two, such as absurd, poetry, symbols, and incongruity (also expressed in terms of “gap” and “counterpoint”).

5.1.1 Detailing the preference for specific resources

After completing the table provided in Q4, those cartoonists who manifested a preference for certain resources were asked to explain why. Out of the 39 cartoonists who answered this question (Q5), 8 (20 %) affirmed not being able to provide a reason or gave an unrelated response. The other 31 responses were classified into five groups. Ranging the responses from the least to the most frequent ones, 8 % referred to the audience, newspaper and context (e.g., “People’s reaction to my cartoons!! and the era I am in,” Luc, France), while another 8 % considered the topic and the cartoonists’ motivation. In 11 % of the answers, cartoonists said that the resources used were adapted to their style or to their conception of humor (e.g., “Because it corresponds to my character,” Hachfeld, Germany; “Because these resources, little by little, become part of a personal language. It’s like using consonants and vowels,” Jarape, Colombia). In 17 % of the cases, the professionals stated that they could not mention specific resources because they varied depending on their intention. An example of this comes from the Dutch cartoonist Van Dam: “It depends on the ‘brainwave’, the idea that suddenly comes into your mind when you’re thinking about a subject/topic/theme. Mostly after you get this idea you realize what kind of humor-resources you’re using.”

The majority of the cartoonists that answered this question (56 %) gave an explanation by referring to the main mechanism of incongruity or by mentioning specific resources. An example of the former is Karry’s response:

When creating, I have to be well informed on the subject. My creative process consists of hunting for figures or elements that have nothing to do with the subject, but that, despite being illogical, they present a logic of their own that produces the visual spark when connecting them. (Peru)

Regarding the reference to specific resources, the reason for using paradox brings Agra (Spain/Venezuela) and Jean-Luc Coudray (France) together, who highlight its thought-provoking quality: “I frequently use contradictions, paradoxes, because it is easier for me to create humorous situations from the confrontation of opposites. To create a confusion, so that once it’s triggered, restlessness remains in the observer” (Agra). “I remain in the paradox because I want my ideas to be meaningful and not just funny. It is not a question of making people laugh but of using humor to think, by means of surprise, of perplexity” (Jean-Luc Coudray).

Cartoonists’ responses often refer to general attributes they recognize in the resources used. For instance, “Irony, sarcasm, contradiction, and exaggeration are tools every satirist uses. This is how we make our points, by proving through reason the other side is wrong” (Morin, US); “I think that exaggeration reaches people very well and cultural references are appreciated because they create identification with those who see my work” (Triana, Colombia). Notwithstanding, cartoonists also reflect on the resources used while referring to their own style:

Irony and sarcasm, when used with a certain subtlety, are a clever game for me. Allusions allow me to satirize about a social fact. Exaggerating the characters’ expressions helps me create a humorous effect. Caricatures are of great entertainment for me and cause surprise and fascination in people. If a joke about a particular event is added, the result can be interesting. (Junior, Argentina)

Reflecting on that, I see that in Catalonia there is a humorous culture in which sarcasm and irony are used a lot, it must be something cultural. On the other hand, personally, I see that I use a lot of contradiction and paradox, often visual. Another resource that works for me is exaggeration, either in the script or in the drawing with very grotesque caricatures of the characters. And cultural references facilitate the most immediate connection with the reader, who recognizes those references in the cartoon. (Kap, Spain)

5.2 Open-ended questions: humor and semiotic modes

As mentioned above, a few of the dimensions proposed in order to analyze cartoonists’ answers to Q1 and Q3 are specific to each of the two questions, whereas the majority of the dimensions refers to shared content from answers to both questions.

Shared dimensions address Style, Mode, Cartoon functioning, Cartoon profiles, Cartoon attributes, and Cartoonist’s motivation. Specific dimensions to Q1 are Conception of humor, and Theme while the only specific dimension to Q3 is Difficulty to explain, to analyze.

Table 1 presents all the dimensions and categories considered and their frequency in the corpus of responses. It is important to clarify that more than one dimension can be present in a single response, as many excerpts will illustrate.

5.2.1 Conception of humor

Focusing on the first question, the formulation presupposed a conception of humor which is worth analyzing. As presented in the literature review, the most common conception links humor to funniness. This is also the case for many cartoonists, and some of them felt the need to clarify it when they did not consider their work as funny and framed it instead within “satire,” or “dark humor.” Marlene Pohle’s and Flavien’s statements are in line with this: “In satire, therefore, humor is relative” (Marlene Pohle, Argentina). “I am not a humorous cartoonist; my drawings are not purely ‘funny’. Let’s say that, mainly, the ‘humorous component’ of my cartoons lies in dark humor, cynicism and the absurd” (Flavien, France).

The notion of “serious humor” (Flores 2000; also Cross 2011) is particularly relevant in this context, since it can condense motives beyond entertainment, such as criticism and provocation. Satire and dark humor are effective tools to raise awareness and stimulate critical thinking.

Other conceptions can be identified in a few cartoonists: humor as “subjective” and humor related to wit and cleverness. The idea that humor is useful to reduce a negative effect due to criticisms – in line with a rhetorical approach as mentioned above – is marginal. The only case is Tom’s assertion: “Humor is for sweetening the message” (Netherlands). In a few responses, such as Morin’s or Zyglis’s (see below), a combination of some of the aforementioned perspectives can be identified. “My job is to make a point using graphic satire. Humor is subjective so I do not concern myself with it. The cartoon must make a point and that’s all” (Jim Morin, US).

Humor is not essential to my work, but it is often central to it. On topics of tragedy and death, humor is often inappropriate – occasionally dark humor can work. The tone of the cartoon can adapt to the topic or message. But when humor is employed, it can often be a different type of humor, such as wit or cleverness. Laugh-out-loud humor is not always the intention. (Adam Zyglis, US)

Another type of response – though extremely rare – that could be linked to the conception of humor is the fact of not being systematic. This prevents authors from providing personal features. A good (and humorous) example of this perspective is Rousso’s:

If I could identify the humorous component of my cartoons, it would mean that it could be identified by certain traits. If it could be identified by ‘constants’ it would be reproducible as needed, it would be trivialized, it would then be so contrary to the trait of humor whose dazzle can sometimes surprise … even its author! (Rousso, France)

5.2.2 Theme

When referring to “the humorous component” in their work (Q1), a quarter of the cartoonists mentioned themes: the news, politicians, characters, tragedies. This often helped them precise the subgenre of cartoons they create, based on the news and/or political events. The fact of considering tragedies, as it is the case in some answers, is due to the will to distance themselves from a conception of humor linked to funniness (see Zyglis’s response presented above). Riham’s answer associates the themes she addresses with her personal style: “When in my cartoons I address women’s subjects such as violence” (Riham, Morocco).

5.2.3 Cartoonist’s motivation

In a quarter of the responses to Q1, cartoonists referenced their motivation: mainly to amuse, or to deride, denounce, and alert. Sometimes, these motivations were linked to a particular conception of humor, either as funny or as serious humor. Gilmar’s response reflects an opposition between these two types of humor: “When I do it simply to entertain, without a heavier burden of social criticism” (Gilmar, Brazil). On the other hand, another cartoonist’s response suggests that amusement is possible even in subjects that are typically considered serious or satirical: “I try to make people laugh (or smile) on all subjects, even the serious ones” (A cartoonist from France). When mentioning a playful motivation, it is usually addressed to amuse the readership (e.g., Gilmar) and only rarely the author himself: “If I laugh while doing it” (Ballouhey, France).

In the case of a more oriented satirical motivation, responses included: to deride, criticize, and unmask: “There is not always a humorous component. Humor comes from the offbeat vision of news that sheds light on something wrong with it” (Delucq, France), “I think I have a way of ridiculing my characters by accentuating their faults” (Placide, France).

In his response to Q1, Matador’s perspective on the role of a cartoonist’s work is noteworthy. He suggested that a cartoonist’s work serves as a reflection of reality, highlighting the ability to capture a particular situation or character worthy of caricature: “I believe that the reflection of reality, the caricature is not made by the cartoonist but rather by the victim or the environment” (Matador, Colombia).

Cartoonist’s motivation is marginal in response to Q3 and fits within the patterns already described. The next two examples focus on the cartoonist’s goal and ability to make people think and capture their attention.

Humor is inherent in human beings, we can laugh, smile, but fundamentally think; if a humorous situation makes us think, then we have achieved the objective that is not only the mechanical act of laughing. To achieve this, cartoonists use tools such as drawing and texts that help transmit an idea in the correct way. (A cartoonist from Peru)

Using both is a good way to create contrasts … which is powerful in making a cartoon funny and that, in turn, is needed to get entrance to the mind of the reader. (Collignon, Netherlands)

5.2.4 Personal style

The reference to a personal style is present in at least 20 % of the answers to each of both questions, including only those cases in which particular traits characterizing cartoonists’ work are considered. A few participants mentioned their stroke or the “big noses” from their characters, focusing on their drawing style. For example, in response to Q1, Lefred Thouron (France) said: “Mainly by the big noses. Even if the cartoon is not successful because the subject is misunderstood or the joke is average, there will always remain the big noses.” In response to Q3, Arcadio Esquivel (Costa Rica) referred to his style but in relation to where his cartoons were published: “The verbal (mode) is not to my liking because my cartoon is published outside my country and in other languages and it’s visual because I need to be understood without having to be read.” This link between a visual prevalence in cartoonists’ style and the need to be understood by an international audience is mentioned by a few cartoonists, such as Marlene Pohle from Argentina and Kristian from France.

5.2.5 Cartoon profiles

This category is identified in 23 % of the responses both to Q1 and Q3. Cartoonists mentioned subgenres of cartoons (caricatures, political cartoons, playful cartoons) and/or established differences among cartoons that imply distinct approaches due to their modal nature (visual, verbal, multimodal).

I usually do political satire without words, I think that the graphic mode should predominate, because that way it can be perceived by any viewer, anywhere in the world. In observational humor, I use both verbal and graphic modes, just like in comic strips. (Miriam, Cuba)

As a cartoonist, I try to make the graphic (mode) prevail and explain itself, but frequently the text must complement it; sometimes, the text is what defines the humorous situation. When a good drawing is enough by itself, I feel fulfilled. But in political cartoons, it is difficult to obtain that result, and due to the changing, convoluted and immediate nature of politics, the text becomes necessary. (Agra, Spain/Venezuela)

5.2.6 Modes

The use of semiotic modes, whether visual, verbal, or both, is frequently mentioned in responses to both Q1 (44 % of the cases) and Q3 (89 %). The reference to both semiotic modes is notably higher in Q3, as it could be expected given that the question specifically asked about the ways in which visual and verbal modes are utilized. This dimension was always discussed in relation to a different aspect, as demonstrated in Miriam’s and Agra’s last examples.

5.2.7 Cartoon attributes

A few cartoonists considered at least one cartoon attribute – 19 % in the answers to Q1 and 37 % in the answers to Q3. Responses addressing attributes can refer to cartoonists’ perspectives on their personal style or to generic traits that they identify in cartoons. Attributes have been grouped in four categories, as informed in Table 1. Two of these categories refer to the visual mode while the other two are more general.

The first category focuses on cartoon funniness and effectiveness, which is related to being rapidly and easily understood, concise and simple. Kristian’s response exemplifies a reference to a personal style with regard to simplicity as a relevant feature of cartoons: “Move towards the greatest possible simplicity” (Kristian, France) while Aurel’s excerpt refers both to funniness and effectiveness as a general requirement of cartoons: “The cartoon is a single and unique message, using two media: drawing and writing. Regardless of the reading direction of the cartoon (text first, drawing first then text …), altogether must create a whole and be as funny, effective (fast reading) as possible” (Aurel, France).

The second category refers to the fact that cartoons present a concept, an idea, a message. Cambon’s answer is an example of the last two categories since it combines the importance of an idea or message in cartoons with funniness: “Either the idea of the cartoon is conveyed by the drawing itself, or the idea needs a verbal support, a caption, a dialogue, to become funny” (Cambon, France).

The third and fourth categories address visual attributes of cartoons, which are more frequent in Q3 than in Q1. The third category encompasses the idea – either explicitly or indirectly – that an ideal cartoon is solely visual. An example is Agra’s excerpt: “When a good drawing is enough by itself, I feel fulfilled.” Many French cartoonists (and a Spanish speaking one) quote the famous phrase “A picture is worth a thousand words” to support their visual preference. It has also appeared once as a way to avoid providing precisions about how visual and verbal modes are used (Q3): “I think a picture is worth a thousand words and I take the liberty of referring you to my blog” (Trax, France).

The fourth category groups four different attributes that cartoonists conferred on visual cartoons. One of these features – which has already been linked to a personal style – is that wordless cartoons are more international. They are also considered – compared to multimodal cartoons – to have a stronger impact and to be more appealing to the readership. Finally, a few cartoonists argued that solely visual cartoons are difficult to create when addressing political issues. Phil’s and Gai’s answers combine two of these attributes: “For me, a good gag or press cartoon is a cartoon that needs no text, so everyone can understand it without translation. It’s not always doable, especially in press cartoons” (Phil, France). “If possible, I try to avoid the verbal (mode), I think it’s generally easier and more restricted in scope. My ideal is to focus on the visual (mode), as it is more universal, challenging, appealing to the reader. But many times, I have to settle for a mixture of both resources, or go back and forth between them” (Gai, Chile). Agra’s response, already quoted, claims that words are often needed in political cartoons, due to the nature of politics: changing, convoluted and immediate. Section 6 will address these findings.

5.2.8 Cartoon functioning

In response to Q1, 38 % of the cartoonists took into account Cartoon functioning by mentioning humorous mechanisms, either the basic incongruity underlying humor or specific resources, such as metaphor, irony, exaggeration, pun and the absurd. They referred to incongruity in terms of opposition, dichotomy, contradiction, contrast, surprise, the unusual and the unexpected. A few examples are: “I try to have a biased look, from an unusual angle, to present an ordinary reality in an unusual way” (Philippe Côté, Canada), “An unexpected perspective, contradiction between what someone in the cartoon says and what the cartoon shows …” (Arendt Van Dam, Netherlands). Among French speaking cartoonists, décalage (gap, mismatch, discrepancy) is a frequent term. “In the visual or the verbal discrepancy, or both. A visual situation that is inappropriate to the context. A gap between the text and the situation or the characters depicted, or a gap between text and image” (Aurel, France).

The reference to incongruity or to specific resources is also present in response to Q3 although in a smaller proportion. Modal relations arise when cartoonists are invited to make the use of words and images explicit (Q3). In line with the literature review (see, for instance, El Refaie 2013; Pedrazzini and Scheuer 2019), three categories mentioned by cartoonists are: visual prevalence, verbal prevalence, and complementarity (rarely contradiction).

Visual prevalence is present in 37 % of the responses. Many cartoonists express their willingness to use as few words as possible, which is in line with the belief that an ideal cartoon is solely visual. Flavien (France) takes position within this perspective:

It is claimed that there are two schools of satirical drawing: one of text and one of drawing. I am clearly part of the second school. I use very little text (bubbles and dialogues, titles, captions, etc.). Most of my drawings – and particularly those that I consider most successful – do not have any of these verbal components. Frequently, I tend to consider that the words of certain drawings interfere with the image, are superfluous or even worse, redundant. However, a drawing without text is not “mute.” Drawing is a form of writing, it speaks, and it doesn’t need words to do it. It has been claimed that “an image is worth a thousand words,” and I think that’s quite true. So I try to avoid doing both at the same time. That being said, I would like to point out that what I am saying is valid for me but not for everyone. It’s a choice. Many cartoonists who use text are obviously excellent!

A few cartoonists also granted that “sometimes words carry the message,” even if “best cartoons are all visual” (Danziger, US). Visual prevalence is often considered to be a bigger challenge: “My production, mainly, is made of drawings without text. Here is an added difficulty because the gag must be in the action. The verbal (mode) is relatively easier, because it supports the image” (Harca, Spain).

Complementarity is mentioned by 22 % of the cartoonists, who referred to a “fine conjunction,” “equation,” or “harmony” between image and writing, and the need to avoid redundancy: “It is a fine conjunction of both. The verbal (mode) should not repeat the drawing, otherwise there is no surprise effect” (Coco, France). “An equation must be found where both the verbal and the visual (modes) have their usefulness; I try to avoid too dense bubbles: a good drawing should, in my opinion, be easily understood at first glance” (A cartoonist from France).

I try to complement them without redundancies, making them talk to each other. The text sometimes only contextualizes, at times I use the journalistic structure of the headline, sub-headline and drawing-text. I try to vary and always try to find new ways, giving priority to visual expression. (Chumbi, Argentina)

Sometimes the idea is born from a visual concept. Other times the idea is born from the writing. Each cartoon takes a different form. It can be a humorous visual metaphor or a clever narrative. The words and images need to work together in harmony no matter what type of concept is used. For instance, even in a visual concept, the few words used must help the message and not detract from the humor. (Adam Zyglis, US)

Verbal prevalence is alluded to by 14 % of the cartoonists. The visual mode is considered to take a secondary role, helping to understand or to lighten the writing. Many professionals from this group declared that puns (or verbal contradictions, for a few of them) play a very important role in their humor, and that their cartoons usually present a dialogue between two or more characters. Here is an example: “My cartoons are like puppets that establish a dialogue or monologue. Verbal humor is made of aphorisms, paradoxes, which collide two statements into one, creating short circuits” (Jean-Luc Coudray, France).

As stated in the category “Cartoon Profiles,” and in line with Zyglis’s answer presented above, even though some cartoonists tended to subscribe to a particular modal functioning, they acknowledged that cartoons might present either a visual/verbal prevalence or a complementarity depending on the intention, theme or modal affordances (Kress 2010). That is the case of Art Molero and Man:

I try to prioritize the visual (mode), and although I don’t consider myself a great draftsman, I admit that several times I have had to resort to the text to make the joke clearer. However, it depends on the work being done. I mean, many times, a topical joke requires the text to be understood. However, ‘the joke for the joke’, humor for humor’s sake, does not require text on many occasions. (Art Molero, Spain)

It is a mysterious alchemy to be analyzed. Basically, we can make press cartoons without words. We can also make politicians speak to make them say things that they think but don’t say in public. This is the principle of caricature, but instead of exaggerating the stroke, we exaggerate the speech. (Man, France)

5.2.9 Difficulty to explain/analyze

Nineteen percent of the cartoonists either expressed difficulty to explain the way in which they use the verbal and the visual components, or they preferred to avoid or reject the request to conceptualize it. Some examples are: “It is easier to do it than to describe it!” (Jarape, Colombia), “It is not really thought out, I do it instinctively. I don’t have a recipe” (Sondron, Belgium), “Frankly no. It’s like trying to explain why or how you breathe, whereas it’s more than natural: it’s a reflex. There you go, I answered …” (Lefred-Thouron, France). Very few of them (see, for instance, Man’s quotation above) used the term “alchemy” as a way of expressing a non-systematic or deliberate creation process.

5.3 Network analysis about Semiotic modes, Cartoon functioning, Attributes and Profile

After focusing on each dimension and its categories separately, we will now analyze and visualize how those categories which are specifically related to Cartoon semiotic functioning and Cartoon attributes are interrelated. Figure 2 graphs the relations between the following four dimensions and their categories identified in Q3, among which a few were fused together because of their conceptual proximity and/or low frequency: Mode (Monomodal – visual or verbal; Both – Multimodal –), Cartoon functioning (Visual prevalence; Verbal prevalence; Complementarity; Resources, which includes Incongruity as the main mechanism), Cartoon attributes (Visual, which includes “An ideal cartoon …” and “Visual cartoons …” detailed in Table 1; Varied, which includes “Funny, effective …” and “They present a concept …”) and Cartoon profiles. Besides, the three categories from Q2 (Visual; Verbal; Both – Multimodal –) were also considered in order to closely study cartoonists’ perspectives on modes, taking into account their answers to open-ended and closed-ended questions.

With regard to semiotic modes, unsurprisingly, Figure 3 shows that the most frequent link between the answers to Q2 and Q3 corresponds to the relation between the visual and the verbal modes (multimodal). Interestingly, this correspondence differs when focusing on modal functioning. Multimodality (both in Q2 and Q3) is more connected to Visual prevalence than to Complementarity. Visual attributes also present a frequent connection with Visual prevalence and with Multimodality. This information highlights that even though cartoonists referred to visual and verbal modes in their answers, they preferred visual cartoons because of their suitability for international audiences, their impact and their potential to catch the attention, among other reasons.

Network graph created using Gephi, in which the links between nine categories from Q3 – Mode (M), Functioning (F), Attributes (A) and Profile – and categories from Q2 are visualized.

Another frequent connection identified is between Multimodality and Cartoon profiles. When cartoonists were asked about the way they use visual and verbal modes, some of those who mentioned both modes in their responses, claimed that it depends on the cartoon profile. As stated above, sub-genres (linked to motivation and themes: Pedrazzini and Scheuer 2018) and modal affordances are the most frequently considered aspects for this selective use of modal resources.

6 Discussion and conclusion: a dissected frog, a mysterious alchemy … or some precisions on humor and cartoons

Humor and cartoons – as a particular humorous manifestation – are a heterogeneous phenomenon marked by many tensions. Two of them were mentioned both in the literature review and by some cartoonists who answered the questionnaire: funniness-seriousness, repetition-novelty.

The first tension focuses on the conception of humor and cartoons. In line with the extended use of the term, cartoonists usually conceive humor as something funny; therefore, many of them who perceived a critical and an engaged stance in their own work felt the need to clarify that their humor was associated with satire or dark humor. In such cases, cartoons are considered as a means to raise awareness and stimulate critical thinking, not only or not necessarily to entertain.

The second tension, repetition-novelty, focuses on the process and mechanisms of humor creation. A guiding question in our research was whether cartoonists identified regular patterns in humor or whether they believed humorous resources vary inextricably from cartoonist to cartoonist. The fact that almost all of them chose a set of resources they used in their cartoons from a list provided in the questionnaire, gives us the clue that they recognize some regularities. However, when they are asked to explain how they use image and writing to create humor, different profiles of cartoonists were identified.

A first profile groups the skeptics to humor analysis: humor is conceived as an intuitive activity, “a mysterious alchemy” as referred to by a few cartoonists. Either professionals find it difficult to theorize (“I am not strong in theory,” said the Polish cartoonist Wozniak) or they reject theorizations altogether. Sixteen percent of the cartoonists could be placed in this group. This percentage might be higher considering that at least a few of the fourteen professionals that did not answer this question share this perspective.

Among those who did reflect upon this semiotic question and provided an explanation, a few gave precise answers. The French cartoonist Flavien claims that two schools can be distinguished in cartoons: the visual school, and the verbal one. According to the results obtained, a third option, which groups more than a half of the sample, is the school of multimodality, in which both visual and verbal modes play an important role in humor creation. Cartoonists fitting within this multimodal profile refer to a “fine conjunction” or harmony between words and images. Redundancy is perceived as a poor modal relation they try to avoid.

Many cartoonists (approximately 24 %) position themselves within the “visual school” and grant the image the most important role in humor creation. This third profile of cartoonists considers that an ideal cartoon is solely visual. It is interesting to note that several cartoonists mentioned that political news are difficult to be addressed only visually. Wordless political cartoons are thus highly appreciated.

A fourth profile, which characterizes 5 % of the cartoonists, confers a major role to writing in cartoons, whereas the image is sometimes considered to lighten the text and enrich the context. The message conveyed by professionals is verbal, often by means of dialogues between characters. Puns are frequent resources this group declared to use.

Cartoonists’ perspectives on the visual mode identified in the second and third profiles align with semiotic specificities and affordances attributed to images in the literature. The challenge of depicting political news solely visually may be linked to the suitability of words for representing distant and abstract information and conducting logical analysis. On the contrary, one of the preferences of many cartoonists for the visual mode obeys to its stronger emotional impact – a finding supported by cognitive studies (e.g., Amit et al. 2014; De Houwer and Hermans 1994; Kensinger and Schacter 2006). The perspective that images are more easily recognized across cultures is linked to the analogic specificities of iconic signs (see, for instance, Kress and van Leeuwen 2006).

In addition, a few cartoonists have referred to the concision and simplicity of cartoons, which is considered to favor being rapidly and easily understood by the readership. As presented in the literature review (e.g., Davies 1995; El Refaie 2009; Gombrich 1963; Keren 2018), concision and simplicity coexist with condensation. The multilayered compacted meanings turn in fact cartoons into complex texts that demand an active and reflective reader.

Turning now to the list of resources that cartoonists considered useful for their goal, our results highlight that the frequency in their use varies depending on the resource. Irony and sarcasm are the most frequent devices mentioned by cartoonists. Indeed, these rhetorical figures can be key mechanisms in cartoons (Charaudeau 2011; Pedrazzini and Scheuer 2019; Stewart 2013) and may function as “effective subversive strategies in newspaper journalism” (El Refaie 2005: 781). Along this line, Stewart (2013) points out that irony addresses dominant discourses by subverting dominant frames and ideologies. Both irony and sarcasm often operate by simultaneously quoting an opinion and taking distance from it. In line with this, Jim Morin (US) claimed that irony and sarcasm, together with contradiction and exaggeration, help cartoonists prove “through reason the other side is wrong.” It is also interesting to consider Glez’s point of view, when he states that “irony allows to personalize humor and turn it more militant” (Glez, Burkina Faso). The prevalence of irony and sarcasm in most cartoonists’ perspectives aligns with a committed motivation – stronger than mere entertainment, see Pedrazzini and Scheuer 2018 – and with the satirical status of cartoons. As a matter of fact, irony is considered as the basic mechanism in satirical discourse (Simpson 2003; Stewart 2013).

Contrary to empirical studies in which metaphors are identified as the most usual resources in cartoons, most cartoonists from this sample declared to use analogies only sometimes (and not as often as irony and sarcasm). The reason for choosing the term “analogy” instead of “metaphor” in the questionnaire is due to the fact that analogy is a more inclusive concept: metaphor is considered as a figure of analogy in several manuals of rhetorical figures (e.g., Bonhomme 1998; Fromilhague 1995). However, one hypothesis for this gap between empirical studies and this cartoonists’ perspective is that analogy might be associated with some particular functioning (e.g., morphological), thus bearing in mind a more restricted idea of the resource. Further studies on this specific matter would shed more light on this result.

Puns are the resources cartoonists declared to use less frequently: only sometimes or never. An explanation for this is that puns are above all verbal (visual puns – Lessard 1991 – are less common). Thus, cartoonists pertaining to the “visual school” and some from the “multimodality school” who privilege the image above writing, do not utilize them or only do so occasionally. A trait that some cartoonists highlight about puns is their playfulness. An example is Adam Zyglis’s response: “I am personally drawn to these three: puns, analogies and ironies. Irony and analogy is the bread and butter of cartooning. And puns are just fun.”

Within a dialectical line of thought, a general conclusion that could be drawn from this study is that the tension repetition-novelty underlies cartoonists’ responses since their perspectives usually interweave conceptualizations about cartoons as a discursive genre, on the one hand, and their own professional experience and personal style, on the other. This conclusion is in line with the understanding of an inextricable relationship between conceptualizations and practice (Verschueren 1999).

This study highlights the rich and diverse nature of cartoonists’ unique profession and art, both from the perspective of considering the creative process of humor and cartoons as a mysterious alchemy, and from the more widespread standpoint of accepting the challenge of dissecting the frog.

Funding source: Universidad Nacional del Comahue

Award Identifier / Grant number: C-162

Acknowledgments

We extend our heartfelt gratitude to the cartoonists who participated in our study by filling out our questionnaire and providing us with valuable information. We would also like to extend a special recognition to all those cartoonists whom we had the honor of meeting and who have since passed away. In addition, we thank Diana Gómez, the trained coder who analyzed part of the data.

-

Competing interests: The author reports there are no competing interests to declare.

-

Research funding: This work was supported by the Universidad Nacional del Comahue under Grant C-162.

References

Amit, Elinor, Sara Gottlieb & Joshua D. Greene. 2014. Visual versus verbal thinking and dual-process moral cognition. In Jeffery W. Sherman, Bertram Gawronski & Yaacov Trope (eds.), Dual-process theories of the social mind, 340–354. New York: Guilford Press.Search in Google Scholar

Ammons, David N., John C. King & Jerry L. Yerick. 1988. Unapproved imagemakers: Political cartoonists’ topic selection, objectives, and perceived restrictions. Newspaper Research Journal 9(3). 79–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/073953298800900308.Search in Google Scholar

Ashfaq, Ayesha & Joseph Russomanno. 2021. Protecting “sacred cows”: A comparative study of the factors influencing political cartoonists. Media Watch 12(2). 208–226. https://doi.org/10.15655/mw_2021_v12i2_160147.Search in Google Scholar

Attardo, Salvatore. 1994. Linguistic theories of humor. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.Search in Google Scholar

Attardo, Salvatore. 1997. Semantic foundations of cognitive theories of humor. Humour 4(10). 395–420.10.1515/humr.1997.10.4.395Search in Google Scholar

Attardo, Salvatore. 2001. Humorous texts: A semantic and pragmatic analysis. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.10.1515/9783110887969Search in Google Scholar

Auboin, Elie. 1948. Les genres du risible. Ridicule, comique, esprit, humour. Paris: Ofep.Search in Google Scholar

Barthes, Roland. 1964. Rhétorique de l’image. Communications 4. 40–51. https://doi.org/10.3406/comm.1964.1027.Search in Google Scholar

Best, James J. 1986. Editorial cartoonists: A descriptive survey. Newspaper Research Journal 7(2). 29–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/073953298600700204.Search in Google Scholar

Beth, Axelle & Elsa Marpeau. 2005. Figures de style. Paris: Flammarion.Search in Google Scholar

Bolognesi, Marianna, Roosmaryn Pilgram & Romy van den Heerik. 2017. Reliability in content analysis: The case of semantic feature norms classification. Behavior Research Methods 49. 1984–2001. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-016-0838-6.Search in Google Scholar

Bonhomme, Marc. 1998. Les figures clés du discours. Paris: Éditions du Seuil.Search in Google Scholar

Bouko, Catherine, Laura Calabrese & Orphée De Clercq. 2017. Cartoons as interdiscourse: A quali-quantitative analysis of social representations based on collective imagination in cartoons produced after the Charlie Hebdo attack. Discourse, Context & Media 15. 24–33.10.1016/j.dcm.2016.12.001Search in Google Scholar

Burlerson MacKay, Jenn. 2016. What does society owe political cartoonists? Journalism Studies 18(1). 28–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670x.2016.1218297.Search in Google Scholar

Charaudeau, Patrick. 2011. Des catégories pour l’humour: Précisions, rectifications, compléments. In María Dolores Vivero García (ed.), Humour et crises sociales: Regards croisés France-Espagne, 9–43. Paris: L’Harmattan.Search in Google Scholar

Cohn, Neil. 2013. Beyond speech balloons and thought bubbles: The integration of text and image. Semiotica 197(1/4). 35–63. https://doi.org/10.1515/sem-2013-0079.Search in Google Scholar

Cross, Julie. 2011. Humor in contemporary junior literature. London: Routledge.10.4324/9780203832943Search in Google Scholar

Davies, Lewis J. 1995. The multidimensional language of the cartoon: A study in aesthetics, popular culture, and symbolic interaction. Semiotica 104(1/2). 165–211. https://doi.org/10.1515/semi.1995.104.1-2.165.Search in Google Scholar

Defays, Jean-Marc. 1996. Le comique: Principes, procédés, processus. Paris: Seuil.Search in Google Scholar

De Houwer, Jan & Dirk Hermans. 1994. Differences in the affective processing of words and pictures. Cognition & Emotion 8(1). 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699939408408925.Search in Google Scholar

El Refaie, Elisabeth. 2005. “Our purebred ethnic compatriots”: Irony in newspaper journalism. Journal of Pragmatics 37. 781–797. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2004.10.017.Search in Google Scholar

El Refaie, Elisabeth. 2009. Multiliteracies: How readers interpret political cartoons. Visual Communication 8(2). 181–205. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470357209102113.Search in Google Scholar

El Refaie, Elisabeth. 2010. Young people’s readings of a political cartoon and the concept of multimodal literacy. Discourse 31(2). 195–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596301003679719.Search in Google Scholar

El Refaie, Elisabeth. 2013. Cross-modal resonances in creative multimodal metaphors: Breaking out of conceptual prisons. Review of Cognitive Linguistics 11(2). 236–249. https://doi.org/10.1075/rcl.11.2.02elr.Search in Google Scholar

Evrard, Franck. 1996. L’humour. Paris: Hachette.Search in Google Scholar

Falardeau, Mira. 1981. Pour une analyse de l’image comique. Communication Information 3(3). 20–51. https://doi.org/10.3406/comin.1981.1108.Search in Google Scholar

Falardeau, Mira. 2015. Humour et liberté d’expression: Les langages de l’humour. Quebec: Presses de l’Université Laval.10.1515/9782763728186Search in Google Scholar

Falardeau, Mira. 2020. A history of women cartoonists. Oakville: Mosaic Press.Search in Google Scholar

Flores, Ana B. 2000. Humor y posmodernidad: el humor serio. In Ana B. Flores & Elena del Carmen Pérez (eds.), La Argentina humorística: Cultura y discurso en los noventa. Córdoba: Ferreyra Editor.Search in Google Scholar

Freud, Sigmund. 1928. Humour. International Journal of Psychoanalysis 9. 1–6.Search in Google Scholar

Fromilhague, Catherine. 1995. Les figures de style. Paris: Nathan.Search in Google Scholar

Gombrich, Ernst H. 1963. The cartoonist’s armory. In Meditations on a hobby horse, 127–142. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.Search in Google Scholar

Gombrich, Ernst H. 2000. Art and illusion: A study in the psychology of pictorial representation. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.10.1353/book.114736Search in Google Scholar

Gray, Jared A. & Thomas E. Ford. 2013. The role of social context in the interpretation of sexist humor. Humor 26(2). 277–293. https://doi.org/10.1515/humor-2013-0017.Search in Google Scholar

Gross, Alan. G. 2009. Toward a theory of verbal–visual interaction: The example of Lavoisier. Rhetoric Society Quarterly 39(2). 147–169. https://doi.org/10.1080/02773940902766755.Search in Google Scholar

Groupe μ. 1992. Traité du signe visual: Pour une rhétorique de l’image. Paris: Seuil.Search in Google Scholar

Haberman, Shelby J. 1973. The analysis of residuals in cross-classified tables. Biometrics 29. 205–220. https://doi.org/10.2307/2529686.Search in Google Scholar

Hoek, Leo. 2002. Timbres-poste et intermédialité: sémiotique des rapports texte/image. Protée 30(2). 33–44. https://doi.org/10.7202/006729ar.Search in Google Scholar

Hynds, Ernest. 1977. Survey profiles editorial cartoonists. Masthead 29. 12–14.Search in Google Scholar

Kensinger, Elizabeth A. & Daniel A. Schacter. 2006. Processing emotional pictures and words: Effects of valence and arousal. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience 6(2). 110–126. https://doi.org/10.3758/cabn.6.2.110.Search in Google Scholar

Keren, Ran. 2018. From resistance to reconciliation and back again: A semiotic analysis of the Charlie Hebdo cover following the January 2015 events. Semiotica 225(1/4). 269–292. https://doi.org/10.1515/sem-2015-0128.Search in Google Scholar

Kress, Gunther. 2010. Multimodality: A social semiotic approach to contemporary communication. London: Taylor & Francis.Search in Google Scholar

Kress, Gunther & Theo van Leeuwen. 2006. Reading images: The grammar of visual design. London: Routledge.10.4324/9780203619728Search in Google Scholar

Lamb, Christopher. 1996. Perceptions of cartoonists and editors about cartoons. Newspaper Research Journal 17(3–4). 105–119. https://doi.org/10.1177/073953299601700309.Search in Google Scholar

Lessard, Denys. 1991. Calembours et dessins d’humour. Semiotica 85(1/2). 73–89. https://doi.org/10.1515/semi.1991.85.1-2.73.Search in Google Scholar

Liu, Yu & Kay O’Halloran. 2009. Intersemiotic texture: Analyzing cohesive devices between language and images. Social Semiotics 19(4). 367–388. https://doi.org/10.1080/10350330903361059.Search in Google Scholar

Llera, José A. 2003. Una aproximación interdisciplinar al concepto de humor. Signa 12. 613–628. https://doi.org/10.5944/signa.vol12.2003.31734.Search in Google Scholar

Martin, Rod A. & Thomas Ford. 2018. The psychology of humor: An integrative approach. London: Academic Press.Search in Google Scholar

Martinec, Radan & Andrew Salway. 2005. A system for image–text relations in new (and old) media. Visual Communication 4(3). 337–371. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470357205055928.Search in Google Scholar

Negro Alousque, Isabel. 2014. Pictorial and verbo-pictorial metaphor in Spanish political cartooning. Círculo de Lingüística Aplicada a la Comunicación 57. 59–84. https://doi.org/10.5209/rev_clac.2014.v57.44515.Search in Google Scholar

Pedrazzini, Ana. 2010. La construction de l’image présidentielle dans la presse satirique : vers une grammaire de l’humour. Jacques Chirac dans l’hebdomadaire français Le Canard enchaîné et Carlos Menem dans le supplément argentin Sátira/12. Paris: Université Paris Sorbonne. https://theses.fr/2010PA040203 (accessed 29 August 2024).Search in Google Scholar

Pedrazzini, Ana. 2012. Dos presidentes bajo la mirada del dibujante satírico: el caso de la caricatura política y sus recursos en dos producciones de Francia y Argentina. Antíteses 5(9). 25–53. https://doi.org/10.5433/1984-3356.2012v5n9p25.Search in Google Scholar

Pedrazzini, Ana & Nora Scheuer. 2018. Distinguishing cartoon subgenres based on a multicultural contemporary corpus. European Journal of Humour Research 6(1). 100–123. https://doi.org/10.7592/ejhr2018.6.1.pedrazzini.Search in Google Scholar

Pedrazzini, Ana & Nora Scheuer. 2019. Modal functioning of rhetorical resources in selected multimodal cartoons. Semiotica 230(1/4). 275–310. https://doi.org/10.1515/sem-2017-0116.Search in Google Scholar

Raskin, Victor. 1984. Semantic mechanisms of humor. Dortrecht: D. Reidel.10.1007/978-94-009-6472-3Search in Google Scholar

Riffe, Daniel, Donald Sneed & Roger Van Ommeren. 1985. How editorial page editors and cartoonists see issues. Journalism Quarterly 62(4). 896–899. https://doi.org/10.1177/107769908506200430.Search in Google Scholar

Schilperoord, Joost & Alfons Maes. 2009. Visual metaphoric conceptualization in editorial cartoons. In Charles Forceveille & Eduardo Urios Aparici (eds.), Multimodal metaphor, 213–240. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.10.1515/9783110215366.3.213Search in Google Scholar

Shultz, Thomas R. 1976. A cognitive-developmental analysis of humor. In Antony J. Chapman & Hugh C. Foot (eds.), Humor and laughter: Theory, research, and applications, 11–36. New York: Transaction.10.4324/9780203789469-2Search in Google Scholar

Simpson, Paul. 2003. On the discourse of satire. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.Search in Google Scholar

Smiraglia, Richard P. 2015. Empirical techniques for visualizing domains. In Richard P. Smiraglia (ed.), Domain analysis for knowledge organization, 51–89. Newland Park: Chandos.10.1016/B978-0-08-100150-9.00004-3Search in Google Scholar

Stewart, Craig O. 2013. Strategies of verbal irony in visual satire: Reading the New Yorker’s “Politics of Fear” cover. Humor 26(2). 197–217. https://doi.org/10.1515/humor-2013-0022.Search in Google Scholar

Tillier, Bertrand. 2005. À la charge! La caricature en France de 1789 à 2000. Paris: Les Éditions de l’Amateur.Search in Google Scholar

Tsakona, Villy. 2009. Language and image interaction in cartoons: Towards a multimodal theory of humor. Journal of Pragmatics 41. 1171–1188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2008.12.003.Search in Google Scholar

Ventola, Eija & Jesús Moya Guijarro (eds.). 2009. The world told and the world shown: Multisemiotic issues. Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.10.1057/9780230245341Search in Google Scholar

Verschueren, Jef. 1999. Understanding pragmatics. London: Arnold.Search in Google Scholar

Werner, Walt. 2004. On political cartoons and social studies textbooks: Visual analogies, intertextuality, and cultural memory. Canadian Social Studies 38(2). 1–11.Search in Google Scholar

White, Elwyn B. & Katharine S. White. 1941. A subtreasury of American humor. New York: Coward-McCann.Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- The semiotic roots of worldviews: logic, epistemology, and contemporary comparisons

- Concept lattice formalisms of Hébert’s “semic analysis” and “analysis by classification”

- AI recommendations’ impact on individual and social practices of Generation Z on social media: a comparative analysis between Estonia, Italy, and the Netherlands

- Varieties and transformations in emic interpretations of Catholic rituals in contemporary Podhale: a semiotic perspective on religious change

- The challenge of dissecting the frog: cartoonists analyze their creative process

- A genealogy of poetry

- Tracing fashion transformations: a comprehensive visual analysis of fashion magazine covers

- A study in scarlet: cultural memory of the tropes related to the color red, female countenance, and onstage makeup in the Sinophone world

- Review Article

- La sémiotique qui étonne toujours: le bilan de l’année 2023

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- The semiotic roots of worldviews: logic, epistemology, and contemporary comparisons

- Concept lattice formalisms of Hébert’s “semic analysis” and “analysis by classification”

- AI recommendations’ impact on individual and social practices of Generation Z on social media: a comparative analysis between Estonia, Italy, and the Netherlands

- Varieties and transformations in emic interpretations of Catholic rituals in contemporary Podhale: a semiotic perspective on religious change

- The challenge of dissecting the frog: cartoonists analyze their creative process

- A genealogy of poetry

- Tracing fashion transformations: a comprehensive visual analysis of fashion magazine covers

- A study in scarlet: cultural memory of the tropes related to the color red, female countenance, and onstage makeup in the Sinophone world

- Review Article

- La sémiotique qui étonne toujours: le bilan de l’année 2023