Abstract

The effectiveness of vaccination programmes depends on high levels of public trust in political, scientific and health-related institutions, but public trust in vaccines can waver. This article explores aspects of public trust and mistrust on a web media platform about the MMR (measles-mumps-rubella) vaccine through the statements of a doctor and an anonymised ‘anti-vaxxer’. Thematic analysis identifies commonalities and divergences in both perspectives. Both trust and mistrust of MMR vaccination are presented as moral, reasoned stances by their proponents; they are connected to the individual’s experiences and situations, but are associated with very different trust attitudes to scientific and political institutions. Moreover, both the trustworthiness of the speakers themselves and the (un)trustworthiness of authorities are emphasised. Trust and mistrust are also thematised in relation to contextual matters such as the role of social media and the historical MMR controversy. Further research towards identifying common ground between trust positions is recommended.

1 Introduction

Vaccination programmes are central components of global public health endeavours and save millions of lives every year (WHO 2023c). Measles is a particularly contagious and potentially very serious disease, but it can be prevented by MMR (measles-mumps-rubella) vaccination. WHO (2023b) states that the measles vaccination is estimated to have averted 56 million deaths between 2000 and 2021 and that an estimated 128,000 measles deaths occurred globally in 2021 mostly among unvaccinated or under-vaccinated children below five years of age.

Vaccine uptake rates reflect levels of public confidence or trust in vaccines (Larson et al. 2011, 2021; Wheelock and Ives 2022). However, vaccine confidence levels waver; in 2022, the vaccination rate worldwide for children’s first dose of the measles vaccine was at its lowest since 2008 (WHO 2023b), and many European countries have recently experienced a resurgence in measles (Wilder-Smith and Qureshi 2020). A major contributor to public mistrust in the MMR vaccine was an article written by Andrew Wakefield and colleagues, which was published in 1998 by The Lancet and subsequently retracted by the journal, that incorrectly made links between the MMR vaccine and autism. Despite resounding scientific proof of the MMR vaccine’s safety, public trust in the MMR vaccine has not completely recovered since Wakefield’s controversial article (Wilder-Smith and Qureshi 2020).

Not surprisingly, given the importance of the MMR vaccine to global health, there has been considerable research interest in MMR vaccination uptake and how it might be improved. Among the recommended solutions to vaccine hesitancy and trust-building are community-specific immunisation services and interventions, public health campaigns and web-based decision aid tools (Thompson et al. 2023). Regular opinion polling to document tendencies has also been suggested as a strategy (Motta and Stecula 2021). Besides concerns about the lingering global impact of the Wakefield article, there is also broad awareness of the need to understand the impact of the new media context (internet and social media) due to concerns that “the Internet, and specifically social media, may be facilitating the spread of anti-vaccination misinformation” (Hoffman et al. 2019, 2217). This is in part because the clustering of social media users in communities of interest can foster “confirmation bias, segregation, and polarization” (Del Vicario et al. 2016, 558), and anxieties about perceived serious adverse effects of vaccines can spread quickly on these media through “emotional contagion” (Larson et al. 2021, 3). However, social media and the internet also provide valuable insights into the public discourse around vaccines as well as constitute an increasingly important medium through which public health authorities can engage publics (Larson et al. 2021).

Larson et al. (2011, 527) acknowledge the challenges of communicating to the public about vaccines and that clear evidence-based information is not enough, as one must also bear in mind the complex array of “scientific, economic, psychological, sociocultural, and political factors” that influence parents’ decisions to vaccinate their children (or not) against MMR. Similar insights into sociocultural aspects of vaccination were identified in the recent literature review of Wilder-Smith and Qureshi (2020) and in previous work by health anthropologists Leach and Fairhead (2007) on vaccine anxieties.

Building on the insights of the aforementioned literature on the significance of the online setting to vaccine debates and sociocultural aspects of vaccine anxieties and concerns, this article explores how trust and mistrust in relation to the MMR vaccine are expressed by those who adopt stances that are either ‘for’ or ‘against’ MMR vaccination in online communication. The research question explored is: How are the divergent perspectives regarding trust and mistrust of the MMR vaccine presented and legitimised? The empirical contribution of this article, then, is the identification of expressions of trust and mistrust on “the surface of discourse”, as Foucault (1972) described it (p. 95).

After providing a brief overview of the historical background to MMR vaccine scepticism (see also Fage-Butler et al. 2022) and discussing the role of traditional media and social media in shaping vaccine debates, this article explores data from an article on a web media platform directed at young people, called Refinery29 (Gil 2019) that juxtaposed the opposing perspectives of two individuals on MMR vaccination – a doctor and an anonymised so-called ‘anti-vaxxer’. Thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke 2006, 2014) of what meanings and values people associate with trust and mistrust on the MMR vaccine was used as it indicates the arguments that are used to validate these positions. It is hoped that close qualitative empirical analysis will enrich current theoretical understandings of trust and mistrust of the MMR vaccine, and demonstrate the value of using qualitative methods to analyse discursive traces of vaccine trust and mistrust.

2 The Role of Different Media Types in the MMR Vaccine Debate

The combined MMR vaccine was developed by vaccine pioneer Dr. Maurice Hillemann in 1971 for use against measles, mumps and rubella (WHO 2023a). For maximum protection, it should be administered in two doses: the first dose at around 12–15 months of age, and the second dose between 4 and 6 years of age. Measles, in particular, is a serious disease as it can result in complications such as deafness, blindness, encephalitis and death. The MMR vaccine, administered twice, prevents these diseases and associated complications, and if sufficient numbers are vaccinated, populations can achieve herd immunity so that those who are unable to have or have not yet had the vaccine are protected.

In 1998, Wakefield and colleagues published an article in The Lancet suggesting a link between MMR vaccination and autism; the link was emphatically disproven in other epidemiological studies, and Wakefield’s paper was retracted. However, the posited links between the MMR vaccine and autism resulted in large drops in immunisation rates, and some doubts in the vaccine have persisted despite clear scientific evidence of its safety and efficacy (Larson et al. 2011). This has meant that many countries have lost their measles-free status (Leong and Wilder-Smith 2019), and WHO (2019) has recently identified vaccine hesitancy as one of the 10 greatest threats to public health.

The media have played a decisive role in the wavering of public trust in the MMR vaccine. ‘Traditional’ media such as newspapers have “previously served as a moderating force, filtering scientific information and fact-checking, however imperfectly, for their audience” (Burki 2019, 258) – essentially, aligning their messages with scientific consensus. However, Lewis and Speers (2003) suggested that the usual journalistic practice of presenting two sides of the story for balance may have encouraged the spread of mistrust in the MMR vaccine among the British public, as the principle of balanced journalism gave too much credence to Wakefield, particularly as the weight of evidence for both sides was not equal (Dobson 2003). Other contextual factors noted by Lewis and Speers (2003) include the fact that British journalists’ own mistrust of governmental advice had already been elevated by the UK government’s previous poor handling of the bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) outbreak. The British public were also concerned about news reports that the prime minister, Tony Blair, had refused to state definitively whether his infant son had received the MMR vaccine. Lewis and Speers (2003, 916–917) further asserted that the MMR controversy gained a hold on the public imagination through Wakefield’s effective PR and “well-organised anti-vaccination lobby groups that were keen to provide moving testimonies from parents who made themselves available to journalists”, highlighting the impact of affective personal narratives on public trust. Lewis and Speers (2003, 916) also noted that scientists failed to communicate clearly to the public both about the spurious links made between MMR vaccination and autism, and their concerns about the potential risks of rejecting the combined MMR vaccine in favour of administering vaccination against the three diseases separately, an idea that had emerged as “the most popular alternative” to the combined MMR.

The MMR case is historic, but the impact of Wakefield still resonates today (Motta and Stecula 2021), not just in the UK but also globally, as his paper is still referred to in online discussions about the vaccine (Fage-Butler et al. 2022). While groups organising resistance to vaccination have long existed (Hobson-West 2007), the new media environment provides space for the dissemination of alternative perspectives on vaccines. Websites that promote vaccine scepticism have previously been examined and a range of effective persuasive strategies including appeals to scientific knowledge and personal testimonies have been identified; Moran et al. (2016, 159) summarised their main findings on such persuasive strategies in web communication in the following, highlighting the importance of knowledge, and connecting with people’s values and lifestyle norms:

Many pages used what they represented as scientific evidence to support an anti-vaccination message. Anecdotal evidence in the form of stories or personal testimonials supplemented these ‘scientific’ arguments. […] Additionally, many pages appealed to readers’ underlying values and ideologies – for example, many pages connected anti-vaccine sentiment to one’s sense of individuality or freedom of choice. Pages also frequently connected anti-vaccine sentiment to broader lifestyle norms, such as using alternative or non-western medicine, homeopathy, and healthy eating.

Social media such as Facebook and online parent forums that take up the MMR vaccine debate can lead to greater polarisation (Schmidt et al. 2018) and amplify emotive aspects (Zummo 2017), both of which are likely to harden opposing trust positions, while algorithms curate social media environments so one is less likely to encounter opposing perspectives on vaccination (Nuwarda et al. 2022). Smith and Graham (2019, 1310) note that conspiracy-style discourses of “moral outrage and structural oppression by institutional government and the media” are evident on anti-vaccination networks on Facebook. While there are concerns that the new digital environments may be deepening rifts between those who hold different trust perspectives, there is also growing recognition of the need for greater awareness of others’ trust perspectives and the value of openness and dialogue (Thomas and Silva 2022).

3 Theories of Trust and Mistrust

In this section, I provide an overview of trust and mistrust theories, emphasising the complex, contextualised nature of trust and mistrust, as well as their cultural and values-related qualities in discursive instantiations.

Although focusing on a different topic, climate change, a recent systematic meta-narrative review that I undertook with colleagues (Fage-Butler, Ledderer, and Hvidtfelt Nielsen 2022) demonstrated the complexity of trust and mistrust in academic literature, as trust and mistrust of climate science have been narrativised as attitudinal, cognitive, affective, contingent, contextual and communicated (discursive). The same review article also noted that while empirical studies may investigate ‘trust’, they often do not define what they mean by it. The fact that ‘trust’ as a “broad-spectrum concept” (Baghramian 2019, 1) is often used without clarification or definition is problematic. As Castelfranchi and Falcone (2010, 10) explain, ‘trust’ is a complex signifier; it “is a layered notion, used to refer to several different (although interrelated) meanings” and thus warrants specification as well as investigation, which this article attends to through close qualitative analysis of discourse.

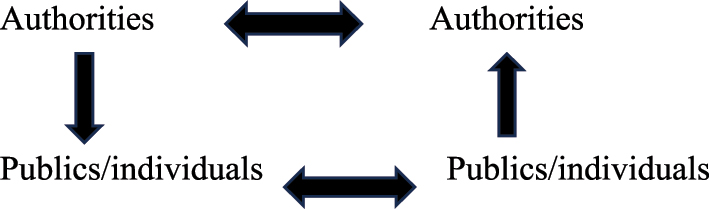

Trust has many spheres of application, often in situations of risk or dependence: for example, it can relate to a belief held by one individual that another will honour a commitment (Svendsen 2018), or broad societal conviction that authorities are able to manage a challenge such as a pandemic (Dohle, Wingen, and Schreiber 2020). Relations of trust and mistrust can prevail between individuals (Earle and Cvetkovich 1995), between the individual/publics and state institutions (Sønderskov and Dinesen 2016), and between the state and its citizens (Petersen 2021). Offe (1999) usefully conceptualises trust between the public and authorities along various axes, which I represent in Figure 1.

Trust between publics/individuals and authorities, drawing on Offe (1999).

This article is mainly concerned with one of these axes: the trust of the public in authorities, reflected by the vertical arrow that extends from publics/individuals to authorities in Figure 1.

While intrapersonal trust exists in the form of self-trust (see, e.g., Govier 2014; Lippitt 2013), trust is generally understood to be interpersonal or relational (Pedersen 2022; Teymouri Niknam 2019), and thus is inevitably social. Social trust has been defined by Offe (1999, 44) as “the presumption of generally benign or at least nonhostile intentions on the part of partners in interaction”. The expression “nonhostile intentions” here links to two important aspects of social trust: its normative quality and its future orientation, as trust typically pertains where A trusts B to do C. Govier (2014, 6) explains trust in relation to the truster’s expectations that the trustee will behave ethically towards them in the future; this also presumes that the trustee has the competence to act in ways that will not harm the truster:

Trust is in essence an attitude of positive expectation about other people, a sense that they are basically well intentioned and unlikely to harm us. To trust people is to expect that they will act well, that they will take our interests into account and not harm us. A trustworthy person is one who has both good intentions and reasonable competence.

Thus, social trust also often involves an epistemic dimension.

Indeed, the epistemic dimension is also evident when members of the public trust authorities to take decisions (govern) on their behalf, which is central to the contract between citizens and democratically represented politicians whose decisions are expected to reflect the most up-to-date scientific knowledge (Turner 2013). Public trust may be even more required when authorities recommend that citizens undertake actions to avert potential future dangers (risks) as then they need the explicit commitment of the public for completion of those actions, as is the case in the present article which explores public trust in the context of MMR vaccination. In this case, trust can be described as ‘two-way relational’: publics need to trust authorities’ recommendations, and authorities need to trust the public to follow up with the recommended action.

Sociological and political studies of trust in civil society show that social trust promotes societal cohesion (Castelfranchi and Falcone 2010), leading to reductions in complexity (Luhmann 1979) as well as greater effectiveness and economic prosperity (Fukuyama 1996; Svendsen 2020). Offe (1999) notes that academic interest in trust reflects an interest in how society works, with trust considered to function like an “oil” that lubricates societal transactions (Van der Meer and Zmerli 2017, 7). This means that trust becomes a topic of particular interest when it comes under pressure. Mistrust is often seen as disrupting the smooth running of society. Trust and mistrust are not straightforward opposites or antonyms, however. For example, both trust and mistrust share the presumption of relatively high levels of confidence (Lewicki, McAllister, and Bies 1998), whereas scepticism, which mistrust is sometimes conflated with, involves lower levels of confidence. It is also important to note that trust and mistrust are not mutually exclusive; Lewicki, McAllister, and Bies (1998), for example, show that both often occur simultaneously, and that too much trust can also be problematic.

As already mentioned, trust and mistrust are social and relational, and thus scholarly attention must be directed to context (Lewicki, McAllister, and Bies 1998). Studies of trust often pay attention to national context (Fage-Butler, Ledderer, and Hvidtfelt Nielsen 2022), but cultures of trust and mistrust may exist across national borders or be much more local. One way of gaining traction on such cultures of trust and mistrust is by exploring expressions of trust and mistrust in context using qualitative methods and identifying the underpinning values. The understanding of ‘values’ adopted in this article is drawn from Williams (1967) who understood values as guiding or justifying behaviours, including future-related behaviours. Williams (1967, 23) defined values as “those conceptions of desirable states of affairs that are utilized in selective conduct as criteria for preference or choice or as justifications for proposed or actual behaviour” (p. 23). The focus on values reflects trust’s role as a value-laden cultural reserve, as Offe (1999, 43) asserts: “Trust is a prime example of the cultural and moral resources that provide for […] informal modes of social coordination”. In terms of values, judgements of trustworthiness (where an authority or individual is considered to have qualities that make them worthy of being trusted) have been associated with perceptions of the benevolence, integrity and expertise of the trustee (Hendriks, Kienhues, and Bromme 2015; Mayer, Davis, and Schoorman 1995), qualities that are evident at the level of discourse and that can be analysed accordingly (Fage-Butler 2011).

The approach to trust and mistrust adopted in this article is thus not psychological, like much of trust literature (Fage-Butler, Ledderer, and Hvidtfelt Nielsen 2022), but instead sees trust and mistrust as thematised in communication, reflecting value judgements on the part of the (mis)truster, as benevolence, integrity and expertise (Hendriks, Kienhues, and Bromme 2015; Mayer, Davis, and Schoorman 1995) can be communicated discursively. Indeed, the two aspects are interrelated: trust is underpinned by values, and values can be expressed discursively (Fage-Butler 2022). This is all the more so if the trustworthiness of authorities is challenged in statements of mistrust, which can catalyse counterarguments for why it is a good idea to trust authorities. As such, overt statements of trust in authorities are often employed in relation to topics that have previously been associated with controversy, such as the MMR vaccine. Otherwise, trust is more likely to function as a silent facilitator of relations.

4 Data and Methods

Quantitative methods have often been applied to study trust, particularly in psychological surveys (Fage-Butler, Ledderer, and Hvidtfelt Nielsen 2022) where trust is regarded as the expectation of an entity to deliver good outcomes, and mistrust is understood as the stance or expectation regarding the likelihood of negative outcomes. Often, ‘trust’ and ‘mistrust’ are deemed to be binary opposites, measured by Yes/No questions (Fage-Butler, Ledderer, and Hvidtfelt Nielsen 2022). However, there is increasing awareness of qualitative methods as the most appropriate to use when investigating cultural, contextual or process-related matters associated with trust (Lyon, Möllering, and Saunders 2015), and where trust and mistrust as complex sociocultural phenomena are evident at the level of language, as explained in the last section. These very different ontologies of trust and mistrust which are associated with very different methods highlight the intricate relations between theoretical approaches to trust and mistrust and the methods used to analyse them.

The data (Gil 2019) explored in this article come from a web media platform directed at young people that juxtaposes the perspectives of two individuals on MMR vaccination: a pro-vaccination doctor and an anonymised so-called ‘anti-vaxxer’. This source was selected as it juxtaposes and presents transcripts of opposing perspectives on interview questions relating to the MMR vaccine. The two interviewees do not interact: what we encounter is the juxtaposition of their responses to the same questions. Besides the two interviewees, there is also a third voice that features at the start: the editorial voice that prefaces the interview material with comments on how social media have facilitated anti-vaccine content, and that due to the Wakefield controversy, there has been a sharp rise in the potentially life-threatening disease of measles in some communities. While this editorial voice explicitly underlines the importance, value and safety of the MMR vaccine, it also stresses that “shouting down anti-vaxxers online is doing little to help the situation. So we decided to try and understand why someone would be against vaccinations.” Thus, juxtaposing these opposing perspectives (pro-vaccination and anti-vaccination) represents an attempt to promote greater understanding of the motivations of those who hold anti-vaccination perspectives. The authorial voice also proceeds to state that the aim of the webpage is “to better understand the thinking of anti-vaxxers”; and that the overall ambition is to “see if there’s anything we can take from her [the ‘anti-vaxxer’s’] interaction to promote a 100 % pro-vaccine world going forward.” The authorial voice does not return to this second point, and without conducting a study of the effects of the article on readers, one cannot, of course, conclude on this issue. I return again to this point in the Discussion.

As the concern of this article is to capture the nuanced meanings of trust and mistrust and the rationales that underpin statements of trust and mistrust related to the MMR vaccine, this article uses Braun and Clarke’s (2006) method of thematic analysis, as it supports the analysis of (value-laden) themes relating to trust and mistrust on “the surface of discourse” (Foucault 1972, 95). Previous literature also indicates the appropriateness of thematic analysis in this context. For example, Wilder-Smith and Qureshi (2020) in their literature review of research undertaken on parental attitudes and beliefs towards the MMR vaccine found that thematic analysis was often used to explore parental perspectives on the MMR vaccine expressed in interview and focus group studies – again, qualitative data and smaller data sets.

Braun and Clarke (2006, 82) define a theme as a meaning unit that “captures something important about the data in relation to the research question, and represents some level of patterned response or meaning within the data set”. As such, in this article, thematic analysis supports the identification of salient meanings associated with trust and mistrust of MMR vaccination in the data set. Braun and Clarke’s (2006) approach to thematic analysis has two other advantages for the present study. First, it supports the analysis of both overt semantic meanings and latent meanings that indicate ideological positions, which are often associated with value-laden discourses. Second, it also makes it possible to combine inductive and deductive approaches. This was useful as I wanted to explore the data in the light of existing theoretical understandings of trust while being open to new meanings – for another example of an inductive/deductive approach to thematic analysis, see Fage-Butler and Nisbeth Jensen (2013).

According to Braun and Clarke (2006), thematic analysis involves the following six steps, which involve iterative processes: 1) reading through the data carefully to ensure thorough familiarisation, 2) generating initial codes, 3) going through all the data to add new codes if appropriate and refining the initial codes, 4) comparing the codes to identify themes that are checked against the data, 5) reviewing the themes, and 6) writing the report, selecting passages from the data to illustrate the themes. These steps were applied when analysing the data; the findings are presented in the next section.

5 Analysis

The main themes in the thematisation of trust and mistrust of the MMR vaccine in the data (Gil 2019) are presented in this section. In what follows, P1 refers to the anonymous ‘anti-vaxxer’, and P2 refers to the doctor. Reflecting theories on the complex and multi-layered nature of trust, outlined in Section 3, I found trust themes coalescing around two main areas: statements relating to personal trust and mistrust in authorities, and societal trust and mistrust. I have therefore reflected this in the presentation of the findings below. Note that the analysis reflects the final product of much iterative analysis between text, codes and themes, following Braun and Clarke’s (2006) six steps. The quotations included in the analysis provide examples of the main themes and are included for exemplification purposes and transparency.

PERSONAL TRUST AND MISTRUST IN AUTHORITIES

Theme 1:

The epistemic basis of the conflicting positions on trust in the MMR vaccine

The theme of knowledge features in the statements of both P1 and P2. Both P1 and P2 make claims to expert knowledge:

From the various research and reading that we’ve done, both since and before being pregnant […] (P1)

As an intensive care doctor […] (P2)

These quotes indicate the broad societal ‘currency’ of scientific knowledge and research. Both speakers underline their familiarity with the facts, and thus their trustworthiness. P1, however, challenges the trustworthiness of ‘experts’, specifically with respect to their knowledge and integrity, with ‘experts’ seen as being in collusion:

I understand that “professionals” state that there isn’t enough evidence to link MMR with autism (of course, why would they admit it does? Pharmaceutical companies are some of the largest money-making businesses going). (P1)

Another concern of ours is that when doctors are asked what’s in each of these vaccines, they’re unable to answer. Is it not their job as health professionals to know the answer to this simple question? And to know what each ingredient does? (P1)

Interestingly, other forms of knowledge – such as experiential knowledge gained through work or through acquaintances – are also used to validate the trust positions of both P1 and P2:

I’ve worked in the care industry for many years: from elderly care to childcare to mental health, autism and Asperger’s. In particular when it comes to autism, which is in my own family, and after speaking to several parents with autistic children, I’ve concluded that, despite general practitioners’ disagreement, parents noticed an immediate change in their child’s character, and the signs of autism first appeared almost moments after they received the MMR vaccine. (P1)

A healthy diet, vigilant monitoring of her health and regular exercises will be enough to boost her immune system to fight any infection she may get, including measles, mumps and rubella, which a number of close relatives and friends have contracted and got over perfectly well with the right treatment. (P1)

Seeing a child suffer needlessly from the complications of an illness which could have been prevented by vaccines is not something you ever forget. (P2)

Theme 2:

Moral values motivating decision-making in relation to the vaccine

Another recurrent theme in the statements of both P1 and P2 is that moral values motivate their decision-making in relation to the MMR vaccine. Both P1 and P2 use emotive arguments about being a responsible parent. In the case of P2, her child cannot be vaccinated, so she relies on parents whose children can get vaccinated to protect her child:

The idea of vaccinating a child with the same dose that an adult would receive at the age of 12 months is preposterous to me. (P1)

I was vaccinated as a child and I was, my mother told me, a very sickly child, often with sickness and diarrhoea, which is usually brushed under the carpet by doctors as a normal part of a child’s development, as well as rashes, a continued snotty nose and asthma. If these side effects are what’s to come for my child once she’s vaccinated then I will not be responsible for that. (P1)

Seeing a child suffer needlessly from the complications of an illness which could have been prevented by vaccines is not something you ever forget. It’s heartbreaking and soul-destroying. (P2)

I felt so helpless as a mother knowing I couldn’t protect him, and relied desperately on other mothers to provide him with herd immunity knowing it was out of my hands. (P2)

BROADER SOCIETAL DIMENSIONS OF TRUST AND MISTRUST

Both P1 and P2 also include statements that go beyond accounting for their own trust and mistrust of the MMR vaccine, highlighting the societal dimensions of trust and mistrust.

Theme 3:

A tendency towards growing public distrust of institutions

For P1, her ability to make up her own mind on scientific matters reflects greater public and professional empowerment:

People are becoming wiser and braver, linking the side effects and symptoms to their current circumstances. Even health professionals are now starting to challenge the education given to them, doing their own research and not just relying on what they are being taught directly. (P1)

P2, on the other hand, laments this societal development of increasing anti-expert sentiment, linking it to the Wakefield controversy:

Sadly, some of the blame for the anti-vaccination movement has to lie squarely at the door of former British doctor Andrew Wakefield, whose research linked the MMR vaccination to autism; this has now been widely debunked and discredited. […] I would say: please don’t think of us as “experts”, people like me are just ordinary doctors, who witness firsthand the impact of not vaccinating children, and desperately want to protect our patients. Trust us. (P2)

Theme 4:

The new media environment facilitating mistrust of the MMR vaccine

Both P1 and P2 reflect on the role of social media in the apparently increasing societal tendency to question expert recommendations to parents to vaccinate their children against measles, mumps and rubella. For example, P2 states that social media can bring about a toxic, polarising environment that leads to a one-sided discourse and attacks on scientific experts who are proponents of the vaccine:

Social media has given a platform to those spreading false information about vaccination and undoubtedly this will have contributed to many parents’ decision not to vaccinate their child. Several “anti-vaxx” Facebook groups are highly active and entirely one-sided, not allowing anyone, let alone doctors, to give an alternative view or have a reasoned conversation with those thinking about not vaccinating their children. We’ve recently seen reports of doctors being hounded on social media in what appears to be a coordinated attack, when trying to address some of the concerns around vaccination. This just isn’t right […]. (P2)

P1, on the other hand, is grateful for the possibilities for the dissemination of other perspectives (i.e., freedom of speech) that social media provide, reflecting a discourse of institutional oppression also found in a study of anti-vaccination networks on Facebook (Smith and Graham 2019):

It’s disturbing knowing that I may be told that the research I did for myself on the pro- and anti-vaccination arguments could be completely dismissed. As long as I choose to do not what the government tells me to do, I could be considered a bad or neglectful parent. The people who post the articles that are against vaccination have every right to share their thoughts and “evidence” via social media, as well as the pro-vaccination activists. (P1)

Notably in these two quotations, concern is expressed about what those who hold the opposite trust position on MMR vaccination may be using online communication for. P2 is concerned about those “spreading false information” on Facebook, while P1 refers to those with a pro-vaccination stance as “activists”.

Overall, thematic analysis reveals that both trust and mistrust of MMR vaccination are presented as moral, reasoned stances by their proponents, where knowledge claims play a central role. Both speakers identify with knowledge and research, though they contrast with respect to the perceived trustworthiness of scientific institutions and science-related institutions such as the pharmaceutical industry.

Both the doctor and the ‘anti-vaxxer’ connect their positions on trust in the MMR vaccines with the value of safeguarding health and life, despite reaching very divergent conclusions on the merits of the MMR vaccine. The main difference lies in their conclusions: the ‘anti-vaxxer’ expresses concern about the safety of the vaccine, while the doctor is concerned about the dangers of measles to public health if vaccination is declined. In terms of public trust in institutions, thematic analysis identified the following commonalities in statements of trust and mistrust towards MMR vaccination that are used to legitimise both perspectives: moral arguments (e.g., justifying the decision to vaccinate or not with respect to the need to safeguard life and health), personal experience and knowledge. There is a tendency to emphasise personal aspects in the interviewees’ accounts of their trust in the MMR vaccine – (mis)trust in political institutions is deeply personal and is often expressed via personal narratives.

Trust is also thematised in the data as a societal phenomenon. For both P1 and P2, social media are emphasised, either as being deleterious to trust (P2) or as permitting a space that benefits alternative trust perspectives (P1). Both speakers share the idea that trust in scientific institutions is susceptible to challenges on social media.

6 Discussion and Conclusion

This article shows how trust and mistrust of the MMR vaccine are expressed discursively. Focusing on discursive expressions of trust and mistrust is highly relevant given the significance of the online context for communication about vaccines, described in an earlier section, and the growing awareness of the value of examining cultural aspects of trust, noted by Lyon, Möllering, and Saunders (2015), for example.

Analysis reveals three striking commonalities in the argumentation strategies used by the pro- and anti-vaccine interviewees. Both P1 and P2 backed up their stances using personal narratives and anecdotes, emphasised that they had sufficient knowledge in the area to make their trust claims, and underpinned their stances through affective argumentation and appeals to moral values. In other words, both interviewees underlined their personal context, knowledge and values when accounting for their trust stance on the MMR vaccine. This finding could be used in a follow-up study that applied a participatory approach to bringing together people who have very different perspectives on the MMR vaccine whose aim is to foster greater understanding of the respective positions. In that case, it would be important to consider how these three aspects could be navigated sensitively, considering how both parties would, for example, want to defend their values and save face (Goffman 1955) in relation to their knowledge and thus may be inclined to distrust others. Such a participatory approach would mean rejecting the webpage’s stated ambition of seeing “if there’s anything we can take from [the] interaction to promote a 100 % pro-vaccine world going forward” as that would require ensuring that one perspective trumped another, shutting down dialogue and potentially hardening existing rifts. Instead, all parties would need to be able to share their perspectives on the basis that they were not only heard, but they were also listened to and understood (Waller, Dreher, and McCallum 2015). This would involve a Habermasian commitment to public participation – one that also was open “to renovative impulses from the periphery” (Habermas 1996, p. 357), though where the aim is not consensus per se (which Habermas believed could be achieved through the application of reason), but fostering mutual understanding.

Similarly, as noted in the Data and Methods section, two aims are provided by the editorial voice that prefaces the perspectives of P1 and P2. The first one relates to promoting better understanding of “the thinking of anti-vaxxers”. The promotion of this goal – greater understanding of the perspectives not only of the interviewee who projects anti-vaccine sentiment but also of the interviewee who is pro-vaccine – is certainly an achievable outcome of the juxtaposition of the two perspectives in Gil (2019). The second aim is expressed more as a hope: to “see if there’s anything we can take from her [the ‘anti-vaxxer’s’] interaction to promote a 100 % pro-vaccine world going forward.” This outcome is broadly considered to be unachievable by vaccine experts (Larson et al. 2011). However, focus on the outer edges of the “anti/pro continuum” (Peretti-Watel et al. 2015) may be valuable, as algorithms mean that we less frequently encounter positions online that are dissimilar to our own, and awareness of opposing positions is necessary for understanding (Thomas and Silva 2022). Positive results from participatory projects such as the Citizens’ Assembly in Ireland (Devaney et al. 2020) that physically brought together those who held contrasting and not necessarily dichotomous perspectives suggest that participatory approaches that promote respectful dialogue and listening may be more beneficial to the promotion of mutual understanding across trust-mistrust rifts than online communication, given that the online context, particularly social media, may be putting trust in vaccines under strain globally (Wheelock and Ives 2022).

Theoretically, this article furthers understandings of trust and mistrust in the context of the MMR vaccine. As the analysis shows, trust and mistrust stances to authorities are bolstered by knowledge claims and moral values and are defined in relation to individuals’ personal histories and situations, whereas societal trust relates mainly to the historical and media context of vaccine (mis)trust. Interestingly, the two forms of trust did not really intersect in the data – though in making this observation, it must be borne in mind that the data set is small. The two layers are not so interrelated, so the findings seem out of step with Castelfranchi and Falcone’s (2010, 10) characterisation of trust as a “layered notion, used to refer to several different (although interrelated) meanings [my emphasis]”. Instead, the findings suggest that people present their trust perspective as highly individual to them, when in fact it is directly impacted by their cultural environment, as anthropologists and sociologists of trust and mistrust have amply demonstrated (Carey 2017; Mühlfried 2018; Sztompka 1999). Considering the implications of this finding in relation to a potential follow-up participatory project, it could be valuable to emphasise to a greater extent the cultural bases of perspectives on trust and mistrust to lift discussions beyond the level of personal conviction. It could likewise be important to inform about the cultural and social aspects of trust in educational contexts.

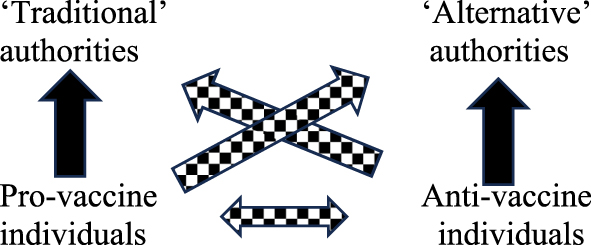

Another finding relates to the interrelationships between trust and mistrust. Both interviewees indicate awareness of claims that would typify each other’s perspectives, and mistrust in the MMR vaccine, for example, is linked to other trust relations, which I represent in Figure 2. Here I build on Offe’s (1999) relational theory of public trust, presented earlier in this article, showing a combination of trust and mistrust relations. Note that by ‘traditional’ authorities, I mean governmental bodies, healthcare authorities etc., while by ‘alternative’ authorities, I mean social media that support anti-vaccination perspectives, anti-vaccine websites etc. In Figure 2, mistrust represented by the chequered arrows indicates mistrust, e.g., from anti-vaccine individuals to traditional authorities, and between those who hold pro- and anti-vaccine sentiments. Note that the arrows reflect findings from the analysis and can only reflect the findings from the perspective of the public – more arrows, including double-headed arrows, would need to be added if the perspectives of the authorities had been included.

Visual representation of findings, drawing on Offe (1999).

Another important dimension revealed by the analysis is that both proponents and opponents of MMR presented themselves as trustworthy. Thus, trust did not only pertain to whether the healthcare authorities who recommended the MMR vaccine were perceived as trustworthy; the interviewees also presented themselves as trustworthy. This may have something to do with the rhetorical aspect of the communication, with both interviewees aiming to come across as trustworthy in relation to their stance on the MMR vaccine as they represented a particular perspective. As such, statements of trust in the vaccine not only have to do with the expertise, benevolence and integrity (Hendriks, Kienhues, and Bromme 2015; Mayer, Davis, and Schoorman 1995) of healthcare authorities; the trustworthiness of the speakers – also in terms of their own expertise, benevolence and integrity – may also be at stake. Reflecting this, the knowledge and value bases of their own claims were underlined in both cases. Thus, trust is relational with respect to the object one trusts, known as the “‘trust in’ factor” (Larson et al. 2018, 1603) as well as one’s own trustworthiness in relation to the reader – what we might call ‘trust in the eyes of the beholder’, a finding that thematic analysis of the data made apparent.

Methodologically, as noted earlier, the theoretical understanding of trust as discursive and value-laden (as opposed to a psychological attitude, for example) underpinned the selection of data and method of analysis; other approaches to trust would involve very different decisions about data and method – and thus impact the findings. Given the different ontological understandings of trust, research needs to reflect this diversity.

A potential weakness of this qualitative paper is the smaller data set. However, the data ideally set up the contrasting perspectives on the MMR vaccine which this article aimed to explore. The polarised nature of the online debate is clearly indicated in the juxtaposition of the two perspectives. One of the advantages of the dichotomous data set is that it minimises the risk of social desirability in interview responses that can otherwise negatively impact the quality of data on trust (Lyon, Möllering, and Saunders 2015, 17). However, a potential disadvantage of the juxtaposition is that is leads to oversimplification, as research shows that mistrust and trust can be (and typically are) held simultaneously (Lewicki, McAllister, and Bies 1998), leading to complex ambivalences. It would therefore be advantageous with a data set that included more complex trust positions in a future study. Also, due to the nature of the data, there is not the possibility of further contextualisation or follow-up questions. Qualitative research facilitating interactions with individuals along these lines would be valuable to understand better the role of context in relation to trust and mistrust of authorities.

In conclusion, this article characterised the thematic features of trust and mistrust perspectives on the MMR vaccine and found them largely related to legitimising the speakers’ stances. The remarkable similarities in the moral argumentation used by both speakers may help to indicate a way of connecting the two perspectives. Both interviewees desired the same outcomes – greater health and safety – but ended up with opposing perspectives on the vaccine. Perhaps awareness of common values in opposing positions of trust and mistrust can provide a starting point for meaningful dialogue? The mistrust between those individuals/groups who represent polarised positions on MMR could at least potentially be addressed that way. The empirical insights presented in the article could also potentially inform authorities’ communication to the general public about the MMR vaccine such as community-specific immunisation services and interventions, public health campaigns and web-based decision aid tools (Thompson et al. 2023). However, further research is needed; as Lyon, Möllering, and Saunders (2015) point out, small-scale in-depth empirical studies of trust and mistrust shed light on particular aspects, but their relevance is maximised when they are connected to the larger picture.

Funding source: Aarhus University Research Foundation

Award Identifier / Grant number: AUFF-E-2019-9-13

-

Research funding: The author disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This publication was supported by funding from Aarhus University Research Foundation, Grant No. AUFF-E-2019-9-13.

References

Baghramian, Maria. 2019. “Introduction.” In From Trust to Trustworthiness, edited by M. Baghramian, 1–4. Abingdon: Routledge.10.4324/9780429060724-1Search in Google Scholar

Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3: 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.Search in Google Scholar

Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2014. “What Can “Thematic Analysis” Offer Health and Wellbeing Researchers?” Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being 9: 26152. https://doi.org/10.3402/qhw.v9.26152.Search in Google Scholar

Burki, Talha. 2019. “Vaccine Misinformation and Social Media.” The Lancet Digital Health 1: e258. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2589-7500(19)30136-0.Search in Google Scholar

Carey, Matthew. 2017. Mistrust: An Ethnographic Theory. Chicago: Hau Books.Search in Google Scholar

Castelfranchi, Christiano, and Rino Falcone. 2010. Trust Theory: A Socio-Cognitive and Computational Model. Chichester: Wiley.10.1002/9780470519851Search in Google Scholar

Del Vicario, Michela, Alessandro Bessi, Fabiana Zollo, Fabio Petroni, Antonio Scala, Guido Caldarelli, H. Eugene Stanley, and Walter Quattrociocchi. 2016. “The Spreading of Misinformation Online.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113: 554–9. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1517441113.Search in Google Scholar

Devaney, Laura, Diarmuid Torney, Pat Brereton, and Martha Coleman. 2020. “Ireland’s Citizens’ Assembly on Climate Change: Lessons for Deliberative Public Engagement and Communication.” Environmental Communication 14: 141–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2019.1708429.Search in Google Scholar

Dobson, Roger. 2003. “Media Misled the Public Over the MMR Vaccine, Study Says.” BMJ 326: 1107. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.326.7399.1107-a.Search in Google Scholar

Dohle, Simone, Tobias Wingen, and Mike Schreiber. 2020. “Acceptance and Adoption of Protective Measures during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Role of Trust in Politics and Trust in Science.” Social Psychological Bulletin 15: 1–23. https://doi.org/10.32872/spb.4315.Search in Google Scholar

Earle, Timothy C., and George Cvetkovich. 1995. Social Trust: Toward a Cosmopolitan Society. Wesport: Greenwood Publishing Group.Search in Google Scholar

Fage-Butler, Antoinette. 2011. Towards a New Kind of Patient Information Leaflet? Risk, Trust and the Value of Patient Centeredness (PhD). Aarhus: Aarhus University.Search in Google Scholar

Fage-Butler, Antoinette. 2022. “A Values-Based Approach to Knowledge in the Public’s Online Representations of Climate Change.” Frontiers in Communication 7: 978670. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2022.978670.Search in Google Scholar

Fage-Butler, Antoinette, Loni Ledderer, and Kristian Hvidtfelt Nielsen. 2022. “Public Trust and Mistrust of Climate Science: A Meta-Narrative Review.” Public Understanding of Science 31 (7): 832–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/09636625221110028.Search in Google Scholar

Fage-Butler, Antoinette, Kristian Hvidtfelt Nielsen, Loni Ledderer, Marie Louise Tørring, and Kristoffer Laigaard Nielbo. 2022. “Exploring Public Trust and Mistrust Relating to the MMR Vaccine in Danish Newspapers Using Computational Analysis and Framing Analysis.” In Digital Humanities in the Nordic and Baltic Countries Conference (DHNB 2022). Uppsala. https://ceur-ws.org/Vol-3232/paper18.pdf.10.5617/dhnbpub.11289Search in Google Scholar

Fage-Butler, Antoinette M., and Matilde Nisbeth Jensen. 2013. “The Interpersonal Dimension of Online Patient Forums: How Patients Manage Informational and Relational Aspects in Response to Posted Questions.” Hermes 51: 21–38. https://doi.org/10.7146/hjlcb.v26i51.97435.Search in Google Scholar

Foucault, Michel. 1972. The Archaeology of Knowledge. New York: Pantheon.Search in Google Scholar

Fukuyama, Francis. 1996. Trust: The Social Virtues and the Creation of Prosperity. London: Hamish Hamilton.Search in Google Scholar

Gil, Natalie. 2019. “An Anti-vaxxer & a Doctor Argue Their Case on the Vaccine ‘debate’.” https://www.refinery29.com/en-gb/2019/03/228147/pro-anti-vaccination-arguments (accessed October 28, 2023).Search in Google Scholar

Goffman, Erving. 1955. “On Facework: An Analysis of Ritual Elements in Social Interaction.” Psychiatry 18: 213–231, https://doi.org/10.1162/15241730360580159.Search in Google Scholar

Govier, Trudy. 2014. Dilemmas of Trust. Montréal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Habermas, Jürgen. 1996. Between Facts and Norms: Contributions to a Discourse Theory of Law and Democracy. Cambridge: Polity Press.10.7551/mitpress/1564.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Hendriks, Friederike, Dorothe Kienhues, and Rainer Bromme. 2015. “Measuring Laypeople’s Trust in Experts in a Digital Age: The Muenster Epistemic Trustworthiness Inventory (METI).” PLoS One 10: e0139309. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0139309.Search in Google Scholar

Hobson-West, Pru. 2007. “‘Trusting Blindly Can Be the Biggest Risk of All’: Organised Resistance to Childhood Vaccination in the UK.” Sociology of Health & Illness 29: 198–215. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9566.2007.00544.x.Search in Google Scholar

Hoffman, Beth L., Elizabeth M. Felter, Kar-Hai Chu, Ariel Shensa, Chad Hermann, Todd Wolynn, Daria Williams, and Brian A. Primack. 2019. “It’s Not All About Autism: The Emerging Landscape of Anti-Vaccination Sentiment on Facebook.” Vaccine 37: 2216–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.03.003.Search in Google Scholar

Larson, Heidi J., Richard M. Clarke, Caitlin Jarrett, Elisabeth Eckersberger, Zachary Levine, Will S. Schulz, and Pauline Paterson. 2018. “Measuring Trust in Vaccination: A Systematic Review.” Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics 14: 1599–609. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2018.1459252.Search in Google Scholar

Larson, Heidi J., Louis Z. Cooper, Juhani Eskola, Samuel L. Katz, and Scott Ratzan. 2011. “Addressing the Vaccine Confidence Gap.” The Lancet 378: 526–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(11)60678-8.Search in Google Scholar

Larson, Heidi J., Isabelle Sahinovic, Madhava Ram Balakrishnan, and Clarissa Simas. 2021. “Vaccine Safety in the Next Decade: Why We Need New Modes of Trust Building.” BMJ Global Health 6: e003908. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003908.Search in Google Scholar

Leach, Melissa, and James Fairhead. 2007. Vaccine Anxieties: Global Science, Child Health and Society. London: Earthscan.Search in Google Scholar

Leong, Wei-Yee, and Annika Beate Wilder-Smith. 2019. “Measles Resurgence in Europe: Migrants and Travellers are Not the Main Drivers.” Journal of Epidemiology and Global Health 9: 294–9. https://doi.org/10.2991/jegh.k.191007.001.Search in Google Scholar

Lewicki, Roy J., Daniel J. McAllister, and Robert J. Bies. 1998. “Trust and Distrust: New Relationships and Realities.” The Academy of Management Review 23: 438–58. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1998.926620.Search in Google Scholar

Lewis, Justin, and Tammy Speers. 2003. “Misleading Media Reporting? The MMR Story.” Nature Reviews. Immunology 3: 913–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/nri1228.Search in Google Scholar

Lippitt, John. 2013. Kierkegaard and the Problem of Self-Love. New York: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9781139565110Search in Google Scholar

Luhmann, Niklas. 1979. Trust and Power. New York: Wiley.Search in Google Scholar

Lyon, Fergus, Guido Möllering, and Mark N. K. Saunders. 2015. “Introduction. Researching Trust: The Ongoing Challenge of Matching Objectives and Methods.” In Handbook on Research Methods on Trust, edited by F. Lyon, G. Möllering, and M. N. K. Saunders, 1–24. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.10.4337/9781782547419.00009Search in Google Scholar

Mayer, Roger C., James H. Davis, and F. David Schoorman. 1995. “An Integrative Model of Organizational Trust.” The Academy of Management Review 20: 709–34. https://doi.org/10.2307/258792.Search in Google Scholar

Moran, Meghan Bridgid, Melissa Lucas, Kristen Everhart, Ashley Morgan, and Erin Prickett. 2016. “What Makes Anti-Vaccine Websites Persuasive? A Content Analysis of Techniques Used by Anti-Vaccine Websites to Engender Anti-Vaccine Sentiment.” Journal of Communication in Healthcare 9: 151–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/17538068.2016.1235531.Search in Google Scholar

Motta, Matthew, and Dominik Stecula. 2021. “Quantifying the effect of Wakefield et al. (1998) on Skepticism About MMR Vaccine Safety in the U.S.” PLoS One 16: e0256395. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0256395.Search in Google Scholar

Mühlfried, Florian. 2018. Mistrust: Ethnographic Approximations. Bielefeld, transcript.10.1515/9783839439234Search in Google Scholar

Nuwarda, Rina Fajri, Iqbal Ramzan, Lynn Weekes, and Veysel Kayser. 2022. “Vaccine Hesitancy: Contemporary Issues and Historical Background.” Vaccines 10: 1595. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10101595.Search in Google Scholar

Offe, Claus. 1999. “How Can We Trust Our Fellow Citizens?” In Democracy and Trust, edited by M. E. Warren, 42–87. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511659959.003Search in Google Scholar

Pedersen, Esther Oluffa. 2022. “An Outline of Interpersonal Trust and Distrust.” In Anthropology and Philosophy: Dialogues on Trust and Hope, edited by S. Liisberg, E. O. Pedersen, and A. L. Dalsgård, 104–17. New York: Berghahn Books.10.1515/9781782385578-013Search in Google Scholar

Peretti-Watel, P., H. J. Larson, J. K. Ward, W. S. Schulz, and P. Verger. 2015. “Vaccine Hesitancy: Clarifying a Theoretical Framework for an Ambiguous Notion.” PLoS Currents 7. https://doi.org/10.1371/currents.outbreaks.6844c80ff9f5b273f34c91f71b7fc289.Search in Google Scholar

Petersen, Michael Bang. 2021. “COVID Lesson: Trust the Public with Hard Truths.” Nature 598: 237. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-021-02758-2.Search in Google Scholar

Schmidt, Ana Lucía, Fabiana Zollo, Antonio Scala, Cornelia Betsch, and Walter Quattrociocchi. 2018. “Polarization of the Vaccination Debate on Facebook.” Vaccine 36: 3606–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.05.040.Search in Google Scholar

Smith, Naomi, and Tim Graham. 2019. “Mapping the Anti-Vaccination Movement on Facebook.” Information, Communication & Society 22: 1310–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118x.2017.1418406.Search in Google Scholar

Sønderskov, Kim Mannemar, and Peter Thisted Dinesen. 2016. “Trusting the State, Trusting Each Other? The Effect of Institutional Trust on Social Trust.” Political Behavior 38: 179–202. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-015-9322-8.Search in Google Scholar

Svendsen, Gert Tinggaard. 2018. Trust. Aarhus: Aarhus University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Svendsen, Gert Tinggaard. 2020. “Danmarks verdensrekord i tillid hjælper os i kampen mod corona [Denmark’s World Record in Trust Helps Us in the Fights against Corona].” https://videnskab.dk/kultur-samfund/forsker-danmarks-verdensrekord-i-tillid-hjaelper-os-i-kampen-mod-corona (accessed October 28, 2023).Search in Google Scholar

Sztompka, Piotr. 1999. Trust: A Sociological Theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Teymouri Niknam, Arman. 2019. “Mary Wollstonecraft’s Divergent Attitudes Towards Trust.” Journal of Gender Studies 28: 802–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/09589236.2019.1660148.Search in Google Scholar

Thomas, Merlyn, and Marco Silva. 2022. “Climate Change: How to Talk to a Denier.” https://www.bbc.com/news/blogs-trending-61844299 (accessed October 28, 2023).Search in Google Scholar

Thompson, Sarah, Johanna C. Meyer, Rosemary J. Burnett, and Stephen M. Campbell. 2023. “Mitigating Vaccine Hesitancy and Building Trust to Prevent Future Measles Outbreaks in England.” Vaccines 11: 288. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11020288.Search in Google Scholar

Turner, Stephen P. 2013. The Politics of Expertise. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781315884974Search in Google Scholar

Van der Meer, Tom W. G., and Sonja Zmerli. 2017. “The Deeply Rooted Concern with Political Trust.” In Handbook on Political Trust, edited by S. Zmerli, and T. W. G. van der Meer, 1–16. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.10.4337/9781782545118.00010Search in Google Scholar

Waller, Lisa, Tanja Dreher, and Kerry McCallum. 2015. “The Listening Key: Unlocking the Democratic Potential of Indigenous Participatory Media.” Media International Australia 154: 57–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/1329878x1515400109.Search in Google Scholar

Wheelock, Ana, and Jonathan Ives. 2022. “Vaccine Confidence, Public Understanding and Probity: Time for a Shift in Focus?” Journal of Medical Ethics 48: 250–5. https://doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2020-106805.Search in Google Scholar

WHO. 2019. “Ten Threats to Global Health in 2019.” https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019 (accessed October 28, 2023).Search in Google Scholar

WHO. 2023a. “History of the Measles Vaccine.” https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/history-of-vaccination/history-of-measles-vaccination?topicsurvey=ht7j2q)&gclid=CjwKCAjwjaWoBhAmEiwAXz8DBSCCWrV1BpLVEXTrcURFkwBTVjLR3iu8NTcaJaXKUsXfXKTcxaGQoRoCM6sQAvD_BwE (accessed October 28, 2023).Search in Google Scholar

WHO. 2023b. “Measles.” https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/measles (accessed October 28, 2023).Search in Google Scholar

WHO. 2023c. “Vaccines and Immunization.” https://www.who.int/health-topics/vaccines-and-immunization#tab=tab_1 (accessed October 28, 2023).Search in Google Scholar

Wilder-Smith, Annika B., and Kaveri Qureshi. 2020. “Resurgence of Measles in Europe: A Systematic Review on Parental Attitudes and Beliefs of Measles Vaccine.” Journal of Epidemiology and Global Health 10: 46–58. https://doi.org/10.2991/jegh.k.191117.001.Search in Google Scholar

Williams, Robin M. 1967. “Individual and Group Values.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 371: 20–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/000271626737100102.Search in Google Scholar

Zummo, Marianna. 2017. “A Linguistic Analysis of the Online Debate on Vaccines and Use of Fora as Information Stations and Confirmation Niche.” International Journal of Society, Culture & Language 5: 44–57.Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Introduction

- Understanding Contemporary Societal Challenges with Philosophy of Trust

- Articles

- Public Trust in Technology – A Moral Obligation?

- A Panoramic View of Trust in the Time of Digital Automated Decision Making – Failings of Trust in the Post Office and the Tax Authorities

- Journalists Gaining Trust Through Silencing of the Self

- Between Virtuous Trust and Distrust: A Model of Political Ideologies in Times of Challenged Political Parties

- Trust and Mistrust in the MMR Vaccine: Finding Divergences and Common Ground in Online Communication

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Introduction

- Understanding Contemporary Societal Challenges with Philosophy of Trust

- Articles

- Public Trust in Technology – A Moral Obligation?

- A Panoramic View of Trust in the Time of Digital Automated Decision Making – Failings of Trust in the Post Office and the Tax Authorities

- Journalists Gaining Trust Through Silencing of the Self

- Between Virtuous Trust and Distrust: A Model of Political Ideologies in Times of Challenged Political Parties

- Trust and Mistrust in the MMR Vaccine: Finding Divergences and Common Ground in Online Communication