Abstract

Before 1900, there were few foreign banks in the Ottoman Empire. The most important foreign bank was the Imperial Ottoman Bank. Many rival foreign banks established a presence over time, which could have undermined the power of the Imperial Ottoman Bank due to greater competition. This article examines how rival foreign banks affected the Imperial Ottoman Bank branches, using data on profits of these branches between 1895 and 1914. Empirical findings do not indicate that rival bank branches were related to lower profits for Imperial Ottoman Bank branches in the respective markets.

1 Introduction

As foreign bank entry gathered pace especially in emerging economies, the impact of foreign banks on the profitability of the existing banks has been often questioned in the banking literature. Recent research shows a decrease in interest rates due to higher competition as foreign banks enter the market, leading to lower profits for the existing banks (Bresnahan and Reiss 1991; Claessens, Demirguc-Kunt, and Huizinga 2001; Unite and Sullivan 2003; Jeon, Olivero, and Wu 2011; Xu 2011). Another strand of the literature states that foreign bank entry can increase the profits of the existing banks through an efficiency improvement channel (Hermes and Lensink 2001; Xu 2011).

In the early nineteenth century, the Ottoman economy remained a traditional agricultural economy, and modern banking practices [1] were not highly developed. Moneylenders had conducted almost all financial transactions. Even the Ottoman state obtained loans from the moneylenders in İstanbul on unfavourable terms. There were few foreign banks, such as the Bank of Smyrna and the Ottoman Bank, but they were short-lived with a small branch network (Cottrell 2008, 65; Toprak 2008, 145, 148–9). Thanks to the improvements in communication technology and growth of international trade over time, by 1914 banks from financially developed countries gradually established their presence in the Ottoman Empire. Additionally, foreign banks offered loans to the governments of less developed countries (Baster 1934, 76; Jones 1990; Cottrell 2008, 71).

In this setting, the Imperial Ottoman Bank (IOB) was founded by a group of British and French financiers in 1863. [2] IOB was primarily established to carry out the functions of a state or central [3] bank in the Ottoman Empire (Ferid 1918, 40; Clay 1994; Eldem 1999a, 276; Pamuk 2000a, 204). This is the reason why Clay (1990) names the bank as multinational “national” bank.

The IOB provided loans to the Ottoman Treasury on more favourable terms than the local moneylenders did. There were also other operations carried out by IOB on behalf of the Ottoman state, such as issuing notes. This led to a strong relationship between IOB and the Ottoman state. On the other hand, IOB also enjoyed a near-monopoly position in commercial banking operations (Thobie 1991, 407, 421; Clay 1990, 142; Clay 1994; Eldem 1997, 115–8; Frangakis-Syrett 1997, 268–9; Eldem 2005; Autheman 2002, 82, 2008, 99–106; Clay 2008).

Clay (1994, 602) states that the bank’s strong position started to decline after 1900, arguably due to the increase in the number of rival foreign banks [4] competing against IOB, as reflected by decreasing IOB profits. However, Thobie (1991, 425) argues that IOB was in a better position than any of its competitors in terms of market power, which could imply a limited impact of the competition on the IOB profits.

Based on the arguments of Clay (1994) and Thobie (1991), this article focuses on the impact of rival foreign banks on the profits of IOB branches from an econometric perspective. The article uses dataset of the net profits for IOB and the number of rival foreign bank branches that operated in 64 local banking markets over the period 1895–1914. The data on the competing bank branches were manually collected from the British journal The Banking Almanac. This article represents the first attempt to empirically examine foreign banking competition in the Ottoman Empire. Moreover, none of the previous studies on banking competition examines whether there is a change in the effect of rival banks with respect to the length of time that the rival banks were present in a market. In agreement with Thobie (1991), the results do not show lower profits of IOB branches in the areas affected by the rival banks. Also, results do not show that the length of time a rival bank has been present matters.

The rest of the article is organized as follows: The next section outlines the historical and theoretical contexts of the foreign banking competition in the Ottoman Empire. Section 3 describes the empirical strategy used to tackle the arguments in the historical literature. Section 4 presents the empirical results and robustness tests. Section 5 concludes. Detailed information on the unique dataset, the descriptive statistics, and the control variables in the econometric model are given in the Appendix.

2 Foreign Bank Entry and the Imperial Ottoman Bank

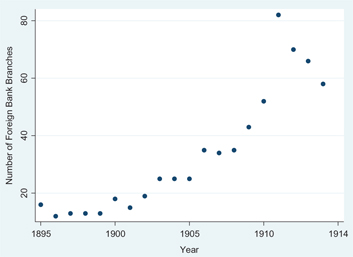

In 1899, the Deutsche Bank opened branches in Jerusalem, Jaffa, and Haifa. Similarly, in 1905, the Banque de Salonique, Bank of Athens, and the Banque d’Orient opened branches in İstanbul and İzmir. Additionally, in 1907, the Deutsche Palastina Bank and Banca di Roma set up branches in Beirut and Tripoli, respectively (Thobie 1991, 421–4; Frangakis-Syrett 1997, 269–70). As shown in Figure 1, the number of rival bank branches operating in the Ottoman Empire increased from 16 in 1895 to 58 in 1914.

The number of foreign bank branches, 1895–1914.

There were several reasons for foreign banks entry to the Ottoman Empire. First, the economic recovery and the high level of international trade with Europe after 1899 attracted foreign firms with banks to provide modern banking facilities (Clay 1994, 590; Thobie 1991, 421; Cottrell 2008, 71–2). Another reason was the intense competition among the major European powers [5] to extend their economic and political control over the Ottoman Empire via their investments (Baster 1934; Geyikdağı 2011, 54–5). Finally, growing budget deficits of the Ottoman state encouraged the entry, to facilitate the availability of new financial resources (Toprak 2008, 148).

In the literature on banking competition, bank entry is expected to decrease the profitability in the respective markets, if there is no collusion among banks and the size of the financial sector is fixed. As the entrant banks need to cover the costs of entry, they attract customers through decreasing interest margins, which leads to lower interest rates in the respective markets and, as a result, the profits of the existing banks decrease (Bresnahan and Reiss 1991; Cetorelli 2002; Unite and Sullivan 2003; Jeon, Olivero, and Wu 2011; Xu 2011).

Similarly, the rival banks competed against the IOB by offering competitive terms of contracts to their customers (Thobie 1991, 424–5; Frangakis-Syrett 1997, 272). Thobie (1991, 424–5) argues that increasing competition forced IOB to follow interest rates set by other foreign banks. For instance, after German banks had entered the Ottoman Empire in 1906, they offered a 3.5% interest rate for deposits, whereas IOB offered a 1% interest rate (Toprak 2008, 158). By 1914, IOB had increased its interest rate for deposits in order not to lose its customers, arguably due to the increasing presence of other foreign banks (Ferid 1918, 217–8; Eldem 1997, 119, 146–7; Eldem 1999a, 277; Autheman 2002, 181–2). Additionally, increasing competition led to a decrease in the interest rate on IOB’s credits (Clay 1994).

Clay (1994, 593, 602) argues that because of increasing competition, profits of several branches of IOB (e.g. Salonika and İzmir branches) decreased in the 1900s. The places where the number of rival bank branches increased gradually – such as İstanbul, Salonika, İzmir, and Beirut – were the ones affected most by the competition (Clay 1994, 593–4; Autheman 2002, 181).

There is not much information on operation fields of IOB and the rival banks. A very high proportion of IOB’s profits were obtained from operations with the Ottoman state (Clay 1994; Eldem 1999a, 291–2). Notably, however, IOB increasingly became a commercial bank after 1890. Its net profit from commercial banking operations became 70% of its total profit in 1913 (Autheman 2008, 101–6) with the It bank mainly funding the commercial sector rather than the agricultural one (Clay 1994; Eldem 1999a, 275–304).

A certain part of the historical literature argues that rival banks competed against IOB in credit and deposit markets. In addition, some of them discounted commercial papers on more favourable rates than those of IOB (Ferid 1918, 218; Thobie 1991, 424–5; Frangakis-Syrett 1997, 271–2; Autheman 2008, 101). Moreover, several foreign banks provided loans to the Ottoman State so it could finance infrastructure investments and wars (Eldem 1999b, 54; Cottrell 2008, 83). These imply that rival banks offered services to the same customers of IOB. Another side of the historical literature argues that the primary aim for many rival banks was to support their countries’ entrepreneurs in the Ottoman Empire, and then to expand their activities. For instance, the Deutsche Bank, the Deutsche Palastina Bank, and the Societa Commerciale d’Oriente opened branches in İstanbul, Aleppo, Haifa, Jaffa, and Jerusalem to serve German and Italian merchants (Frangakis-Syrett 1997, 271–2; Cottrell 2008, 71–5; Geyikdağı 2011, 104).

This historical fact is parallel to the argument of the previous literature on toehold entry, showing that the association between competition and rival banks would be positively related to the amount of time that the rival banks are present in the respective market. Rival banks’ only aim is to target a niche market in the short run, as they are not mature to directly compete against the existing banks. They would expand their activities and attract a higher number of customers in the long run (Reid 1995; Malueg and Schwartz 1991; Berger and Ostromogolsky 2006).

3 Methodology

In order to test the arguments of the historical literature on foreign banking competition, the following regression is used:

where i, c, p, and t index branch, county, province, [6] and year, respectively. The dependent variable is ln(Gicpt), which is the natural logarithm of the net profits for IOB branch i, located in county c of province p, in year t. There were losses of IOB branches in several local banking markets and years, which are dropped because the use of the log specification in the model.

Ficpt is the number of other foreign bank branches operating where IOB branch i operated in year t. The equation also includes the interaction of Ficpt with time trend (Trendit), which allows for examining that the association between competition and rival bank branches would be positively related to the amount of time the bank branches were present in the respective market. [7]Trendit starts when IOB branch i was affected by at least one rival bank branch in year t. β1 and β2 are the coefficients of interest for examining the foreign banking competition in the Ottoman Empire.

In order to mitigate concerns of omitted variables bias, – such as shares of the short- and long-term deposits in total assets – three control variables are included: ln(Ricp) is the natural logarithm of the distance between each IOB branch and railroads in a year t; [8] ln(Ticp) is the natural logarithm of the distance between each IOB branch and trade routes; ln(Pp) refers to the natural logarithm of the total population at province level in 1893. [9]

Additionally, the interaction of ln(Ticp) and ln(Pp) with year fixed effects (γt) allows the local banking markets with different initial characteristics (such as economic and financial development, and market size) to have different time trends. ρi is the branch fixed effects to control for time-invariant branch characteristics (e.g. location, size, funding structure, and strategies) while uicpt is the error term.

As the number of rival bank branches increased in a location, the profits of the IOB branch in the respective market decreased due to higher competition, which implies β1<0. A negative coefficient estimate of β2 implies that the other foreign banks attracted a higher number of customers over time, as they matured and built their market share.

4 Results

The equation in Section 1 is estimated by OLS. The result is reported in column (1) of Table 1. Column (1) indicates a negative coefficient estimate for the effect of the number of rival bank branches. In addition, the coefficient estimate for the number of rival bank branches-time trend interaction variable is negative. However, the point estimates are not statistically different from zero. Ultimately, there is no evidence in Table 1 to indicate that rival foreign bank branches in a market led to higher competition in the respective market.

The impact of rival banks on profits of IOB branches, 1895–1914.

| Dependent variables: ln(profits), profits, and probability of loss | |||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| The number of rival bank branches | –0.05 | 0.01 | –97.67 | –0.09 | –0.08 |

| (0.07) | (0.01) | (181.64) | (0.07) | (0.09) | |

| The number of rival bank branches × Trendij | –0.00 | –0.00 | 2.56 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (12.57) | (0.00) | (0.00) | |

| ln(Distance to railroads) | –0.03 | 0.01 | –2.79 | –0.05 | –0.02 |

| (0.04) | (0.01) | (4.01) | (0.07) | (0.04) | |

| ln(Distance to trade routes) | –0.58*** | 0.24*** | –9.52* | –0.61*** | –0.62*** |

| (0.09) | (0.05) | (10.18) | (0.15) | (0.11) | |

| ln(Population in provinces) | –0.73 | 0.31** | –0.01** | –1.15 | – |

| (0.55) | (0.14) | (0.00) | (0.85) | ||

| Constant | 17.56** | –3.97** | 8242.79*** | 23.04* | 10.07*** |

| (7.11) | (1.81) | (2259.39) | (11.27) | (0.77) | |

| Branch fixed effects | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| ln(Distance to trade routes) × Year fixed effects | YES | YES | NO | YES | YES |

| ln(Population in provinces) × Year fixed effects | YES | YES | NO | YES | NO |

| Distance to trade routes × Year fixed effects | NO | NO | YES | NO | NO |

| Population in provinces × Year fixed effects | NO | NO | YES | NO | NO |

| No. of obs. | 623 | 704 | 704 | 385 | 385 |

| R2 | 0.68 | 0.44 | 0.74 | 0.67 | 0.67 |

Interestingly, column (1) provides no evidence that population [10] and railroads are associated with the profits of an IOB branch. The coefficient estimates for the effect of distance from trade routes are statistically significant at 1%. The point estimate suggests that a 1% decrease in the distance from trade routes increases the profits in an IOB branch by 0.58%. This implies profits of an IOB branch would be high, if they were located close to places that had easy access to roads. The finding is consistent with Table 3, showing large profits of IOB branches in economically developed areas, which had ports or were located along roads.

Taking the natural logarithm of the profits of an IOB forces the omission of observations with negative profits. To examine whether using the log specification is problematic, column (2) examines the impact of rival bank branches on the probability of observing a loss for an IOB branch.

The dependent variable in column (2) is a dummy variable that takes 1 if an IOB branch reported a loss in a given year, and zero otherwise. The point estimates are not statistically different from zero. This suggests that there was no heavy competition which led to losses for IOB branches. This is not surprising, as there were no competing bank branches in many places that IOB branches reported losses. It is important to note that the findings are not sensitive to using the level of profits in IOB branches in terms of statistical significance (column (3)). Therefore, the exclusion of IOB branches that reported losses in column (1) does not constitute a big problem.

Because of the other two reasons, this paper prefers taking the natural logarithm of the profits in IOB branches rather than using the level of profits as a dependent variable. First, the log makes the estimates less sensitive to extreme observations on the profits. As profits only take non-negative values, standard deviation is larger than mean in column (2) of Table 2, which raises the issues of outliers. [11] Second, classical linear model assumptions, such as homoskedasticity and no serial correlation, are likely to hold after using the natural logarithm of the profits.

The competition between IOB and rival banks was more intense especially in places with high numbers of rival bank branches. Over the sample period, the number of rival bank branches was constant in more than half of the counties in the sample. In many of these counties, there were no rival foreign banks. In column (4), this study runs the same regression for a sample without these counties. In addition, many rival bank branches operated in very large urban centres (Table 4). In column (5), regression is re-estimated without places whose population was smaller than the population mean (i.e. 831,692). The point estimates are larger than that in column (1) in magnitude. The results do not change in terms of statistical significance. This means that the baseline results are valid even where large numbers of rival bank branches were existent.

5 Conclusion

The results indicate higher profits for IOB branches which operated along trade routes. This confirms that production, financial, and commercial activities were intense in these places. As a result, the demand for banking services of operating branches was strong, leading to significant profits.

There was an absence of statistically significant correlation between the profits of IOB branches and rival bank branches, even in the presence of large numbers of rival banks. Furthermore, the relationship between rival bank branches and the profits of IOB branches did not depend on the length of time that the rival bank branches were present in the respective market. This non-effect does not necessarily mean that the IOB and rival banks operated in separate markets in the Ottoman Empire.

This study could be refined by future research if a balance sheet data for costs, market shares, and assets of banks can be found as this information gives further insight for the relationship between profits and competition. For example, if cost data for IOB branches were available, the non-effect could be attributed to the potential positive effect of rival banks on efficiency due to the positive spillover effects. Frangakis-Syrett (1997, 271–2) argues that rival foreign banks introduced new financial services and technologies to the Ottoman Empire. This could have counterbalanced the negative impact of competition on the IOB profits. In addition, it would be possible to address a potential bias in the OLS estimates due to reverse causality and measurement error, which could be responsible for this non-effect. However, it is difficult to obtain historical data on banking in the Ottoman Empire, compared with that of other European countries.

Appendix 1: Data

The net profits for 64 branches of IOB operated in 64 counties of 27 provinces [12] for the period 1895–1914 are used. These data come from Eldem (1999a, 510–2). This is the only available information for performance indicators of IOB branches. Therefore, different from previous literature on banking, the net profits are not divided by the total assets of IOB branches. [13] All values are expressed in gold liras. [14] Prices remained stable between 1844 and 1914 because of the gold standard (Pamuk 2004). In addition, the metal content of the Ottoman lira did not change between 1844 and 1923, as the Ottoman state did not debase the lira (Pamuk 2000a, 208). Moreover, the baseline results do not change, after profits were deflated by the İstanbul consumer price index, which is the only available price data. [15] For these reasons, the net profit data in this study could be treated as constant prices.

The data for rival foreign bank branches are extracted from the Banking Almanac of 1895–1914, which was a specialised journal, published annually by Waterlow and Sons since 1844. The Banking Almanac contained detailed information on the names and numbers of British and foreign banks, such as German, French, Italian, and Russian banks, operating in a county within the border of the Ottoman Empire in a given year. [16]

There is no available digital map of the railway lines and the trade routes in the Ottoman Empire. Several sources [17] provide detailed information on the establishment and opening dates of railroad lines, location of each station, where construction of each line was planned, and which places had access to railroads in a given year. In addition, in different sources there is detailed information on start and end points of the trade routes that were in use for the carrying of people and goods. [18]

There is no information on the addresses of IOB branches in a county. Instead, this study uses the distance from the county centre to the nearest railroad line (R) and trade route by creating a map for railroad networks and trade routes [19] in the Ottoman Empire. The branches of IOB were more likely to be in the county centre, so this variable is a good proxy for the proximity of each branch to the nearest railroad line and trade route. Another point worth mentioning is that since there is no reliable data for road networks in the Ottoman Empire, geographic distance, rather than travel distance, is used, which is measured in kilometres. [20]R is a time-varying measure of distance to the railroads, as the Ottoman railroad networks were gradually extended with new tracks from the Balkans to Hejaz, until 1914 (Issawi 1980, 183; Geyikdağı 2011, 88–9).

Finally, the Ottoman province-level population data comes from the 1881/82–93 census. [21] The data gives detailed information on the total numbers of people who lived in each province in 1893. Notably, however, the 1881/82–93 census does not provide detailed information on the population of the Hicaz, Yemen, and Trablusgarp provinces. [22]

Table 2 provides summary statistics of the variables in sample. The average net profit of IOB branches was 3,283 gold liras. On average, there was only one rival bank branch in a county where IOB had one branch. An IOB branch was 114 km away from the trade routes and 110 km from a railroad line on average. The average number of individual residents in each province was 831,692.

Descriptive statistics, 1895–1914.

| Variable | N. of obs. | Mean | Std. dev. |

| Profits | 623 | 3,283 | 3,713 |

| Number of rival bank branches | 623 | 1.02 | 2.20 |

| Distance to railroads | 623 | 109.90 | 211.24 |

| Distance to trade routes | 623 | 114.34 | 130.45 |

| Population | 623 | 831,692 | 400,767 |

Table 3 shows that İstanbul, İzmir, Aleppo, Salonika, and Beirut branches were the most profitable branches of IOB. Their profits range between 13,494 and 5,489 gold liras, on average. These branches were located in places where commercial, production, and financial activities were concentrated. In addition, a high proportion of profits in the İstanbul branch was obtained from operations with the Ottoman state (Clay 1994, 596). The least profitable branches of IOB were in Sandıklı, Diyarbekir, Van, Serres, and Urfa counties. Their profits ranged from 330 to 91 gold liras, on average. Some of these branches (i.e. Diyarbekir, Van, and Urfa branches) were opened to promote financial development in less-developed regions at the request of the Ottoman state. Other branches were primarily opened to make commercial profits (Clay 1994, 607–6).

Summary statistics for profits of several IOB branches, 1895–1914.

| IOB branches | Mean | Std. dev. |

| İstanbul | 13,494 | 7,326 |

| İzmir | 11,370 | 4,824 |

| Salonika | 7,076 | 3,199 |

| Aleppo | 6,531 | 2,723 |

| Beirut | 5,489 | 3,230 |

| Baghdad | 5,445 | 3,146 |

| Damascus | 4,926 | 2,887 |

| Bassorah | 4,507 | 2,798 |

| Sandıklı | 330 | 36 |

| Diyarbekir | 249 | 175 |

| Van | 133 | 159 |

| Serres | 108 | – |

| Urfa | 91 | – |

Table 4 shows the number of rival bank branches in several places and years. Some urban areas, such as Jerusalem, Jaffa, Adana, and Bursa counties, received their first rival bank branch after 1902. Table 4 highlights that there were excessive numbers of rival bank branches in very large urban centres such as Beirut, İzmir, and Salonika counties. Although Table 4 does not show, many counties in the sample, such as Mossul county, did not have any rival bank operating between 1895 and 1914.

The number of rival bank branches in several counties and years, 1895–1914.

| IOB branches | Rival bank branches | |||||

| 1895 | 1898 | 1902 | 1906 | 1910 | 1914 | |

| Adana | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Aleppo | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Beirut | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 6 |

| Bursa | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Çanakkale | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Damascus | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Drama | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | – |

| Edirne | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Giresun | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Haifa | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| İzmir | 2 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 9 |

| Jaffa | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Jerusalem | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 | – |

| Kavala | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | – |

| Mersin | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Mitylini | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | – |

| Monastır | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | – |

| Nazilli | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Pera | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| Salonika | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 5 | – |

| Samsun | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 7 |

| Sandıklı | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Serres | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | – |

| Skopje | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | – |

| İstanbul | 6 | 6 | 7 | 11 | 12 | 15 |

| Trabzon | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Tripoli of Syria | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Xanthi | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | – |

At this point, it should be noted that in case of a possible measurement error in rival foreign bank branch data, the coefficient estimates may be biased downward. Additionally, rival bank branches mainly operated in places where the average profits of IOB branches were high, such as İstanbul, İzmir, and Salonika branches (Tables 3 and 4). This indicates reverse causality and upward bias in the point estimates. Due to data constraints, it is difficult to find a strong and statistically significant instrumental variable for regressors of interest, to mitigate concerns of biased coefficients.

Appendix 2: Control Variables

In the Ottoman Empire, transportation costs were high, as its existing road networks were not in a good condition. Building railroad lines decreased transportation costs. This led to an increase in trade, production, and financial development in places that gained access to railroads over time, as compared with other places that did not have railroads (Eldem 1994, 94; Quataert 1995, 813–4). Higher economic and financial outcomes could have increased the activities of IOB branches that operated in places along the railroads (Clay 1994, 600), which would lead to an estimate of α1<0.

The railroad networks of the Ottoman Empire were not well developed. Trade routes remained important for transportation of goods and people. Commercial, production, and financial activities were still located in places along trade routes. Accordingly, a significant demand for banking services was present in the places along trade routes in comparison with other places (Quataert 1995, 817–9; Eldem 1999, 278, 291–2), which would imply a negative α2.

The Ottoman financial sector grew massively from the 1850s to the Empire’s demise. That means that the profits of IOB could have risen, even as the number of competing banks increased. So, this article controls for market size. The market size can be measured by population, as well as other variables, such as income or GDP (Amel and Liang 1997; Berger et al. 2000; Cohen and Mazzeo 2007). Due to current data availability, this article uses the population of each province in 1893. In the light of findings in previous literature, profits of IOB branches might be high in places where market size was large, which would imply a positive α3.

Acknowledgment

I am grateful for the support and help by Rowena Gray, Elmas Yaldız Hanedar, Timothy Hatton, Vu Minh Hien, Şevket Pamuk, Katharine Rockett, Joao M. C. Santos Silva, Erdost Torun, Ali Coşkun Tuncer, Patrick J. Nolen, Lorna Woollcott, Seçkin Yıldırım, and Ragıp Yılmaz. I would also like to thank the staff of the Albert Solomon Library at the University of Essex and the LSE library. In this article, Imperial Ottoman Bank branch, county, and province names are given in the form in which they appear in the sources from which the information comes.

References

Amel, D. F., and J. N. Liang. 1997. “Determinants of Entry and Profits in Local Banking Markets.” Review of Industrial Organization 12: 59–78.10.1023/A:1007796520286Suche in Google Scholar

Autheman, A. 2002. The Imperial Ottoman Bank. İstanbul: Ottoman Bank Archives and Research Centre.Suche in Google Scholar

Autheman, A. 2008. “A General Survey of the History of the Imperial Ottoman Bank.” In East Meets West Banking, Commerce and Investment in the Ottoman Empire, edited by I. L. Fraser, M. Pohle, and P. L. Cottrell, 97–109. Hampshire: Ashgate Publishing Limited.Suche in Google Scholar

Baster, A. 1934. “The Origins of British Banking Expansion in the Near East.” The Economic History Review 5: 76–86.10.2307/2589918Suche in Google Scholar

Berger, A. N., S. D. Bonime, L. G. Goldberg, and L. J. White. 2000. “The Dynamics of Market Entry: The Effects of Mergers and Acquisitions on Entry in the Banking Industry.” Journal of Business 77: 797–834.10.1086/422439Suche in Google Scholar

Berger, A. N., and P. Ostromogolsky. 2006. “Effects of Banks on ‘Debt-Sensitive’ Small Businesses.” Journal of Financial Economic Policy 1: 44–7.10.1108/17576380910962385Suche in Google Scholar

Bresnahan, T. F., and P. C. Reiss. 1991. “Entry and Competition in Concentrated Markets.” Journal of Political Economy 99: 977–1009.10.1086/261786Suche in Google Scholar

Cetorelli, N. 2002. “Entry and Competition in Highly Concentrated Banking Markets.” Economic Perspectives 26: 18–27.10.2139/ssrn.377741Suche in Google Scholar

Claessens, S., A. Demirguc-Kunt, and H. Huizinga. 2001. “How Does Foreign Entry Affect Domestic Banking Markets?” Journal of Banking and Finance 25: 891–991.10.1016/S0378-4266(00)00102-3Suche in Google Scholar

Clay, C. 1990. “The Imperial Ottoman Bank in the Later Nineteenth Century: A Multinational ‘National’ Bank.” In Banks as Multinationals, edited by G. Jones, 149–57. London: Routledge.Suche in Google Scholar

Clay, C. 1994. “The Origin of Modern Banking in the Levant: The Branch Network of the Imperial Ottoman Bank, 1890–1914.” International Journal of Middle East Studies 26: 589–614.10.1017/S0020743800061122Suche in Google Scholar

Clay, C. 2008. “State Borrowing and the Imperial Ottoman Bank in the Bankruptcy Era (1863–1877).” In East Meets West Banking, Commerce and Investment in the Ottoman Empire, edited by I. L. Fraser, M. Pohle, and P. L. Cottrell, 109–23. Hampshire: Ashgate Publishing Limited.Suche in Google Scholar

Cohen, A., and M. J. Mazzeo. 2007. “Market Structure and Competition Among Retail Depository Institutions.” The Review of Economics and Statistics 89: 60–74.10.1162/rest.89.1.60Suche in Google Scholar

Cottrell, P. L. 2008. “A Survey of European Investment in Turkey, 1854–1914: Banks and the Finance of the State and Railway Construction.” In East Meets West: Banking, Commerce and Investment in the Ottoman Empire, edited by P. L. Cottrell, M. Pohle, and I. L. Fraser, 54–97. Hampshire: Ashgate Publishing Limited.Suche in Google Scholar

DeYoung, R., and I. Hasan. 1998. “The Performance of de novo Commercial Banks: A Profit Efficiency Approach.” Journal of Banking and Finance 22: 565–87.10.1016/S0378-4266(98)00025-9Suche in Google Scholar

Dölek, D. 2007. “Change and Continuity in the Sivas Province, 1908–1918.” MA diss., Middle East Technical University.Suche in Google Scholar

Eldem, V. 1994. Osmanlı İmparatorluğu’nun iktisadi şartları hakkında bir tetkik. İstanbul: Türk Tarih Kurumu Yayınları.Suche in Google Scholar

Eldem, E. 1997. 135 yıllık bir hazine Osmanlı Bankası arşivinde tarihsel izler. İstanbul: Osmanlı Bankası A. Ş.Suche in Google Scholar

Eldem, E. 1999a. A History of the Ottoman Bank. İstanbul: Ottoman Bank Historical Research Centre.Suche in Google Scholar

Eldem, E. 1999b. “The Imperial Ottoman Bank: Actor or Instrument of Ottoman Modernization?” In Modern Banking in the Balkans and West-European Capital in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries, edited by K. P. Kostis, 50–61. Hants: Ashgate Publishing Limited.10.4324/9780429451256-4Suche in Google Scholar

Eldem, E. 2005. “Ottoman Financial Integration with Europe: Foreign Loans, the Ottoman Bank and the Ottoman Public Debt.” European Review 13: 431–45.10.1017/S1062798705000554Suche in Google Scholar

Ferid, H. 1918. Nakid ve i’tibar-i mali, bankacılık. Volume 3. İstanbul: Matbaa-i Amire.Suche in Google Scholar

Frangakis-Syrett, E. 1997. “The Role of European Banks in the Ottoman Empire in the Second Half of the Nineteenth and in the Early Twentieth Centuries.” In Banking, Trade and Industry in Europe, edited by A. Teichova, G. Kurgan-Van Henteruk, and D. Ziegler, 263–67. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Geyikdağı, V. N. 2011. Foreign Investment in the Ottoman Empire: International Trade and Relations, 1854–1914. London: Tauris Academic Studies.10.5040/9780755692910Suche in Google Scholar

Hermes, N., and R. Lensink. 2001. “The Impact of Foreign Bank Entry on Domestic Banking Markets: A Note.” Research Report 01E62, University of Groningen.Suche in Google Scholar

Hermes, N., and R. Lensink. 2004. “Foreign Bank Presence, Domestic Bank Performance and Financial Development.” Journal of Emerging Markets Finance 3: 207–29.10.1177/097265270400300206Suche in Google Scholar

Issawi, C. P. 1980. The Economic History of Turkey, 1800–1914. London: The University of Chicago Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Jeon, B. N., M. P. Olivero, and J. Wu. 2011. “Do Foreign Banks Increase Competition? Evidence from Emerging Asian and Latin American Banking Markets.” Journal of Banking & Finance 35: 856–75.10.1016/j.jbankfin.2010.10.012Suche in Google Scholar

Jones, G. 1990. Banks as Multinationals. London: Routledge.Suche in Google Scholar

Karkar, Y. N. 1972. Railway Development in the Ottoman Empire, 1856–1914. New York: Vantage Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Karpat, K. H. 1985. Ottoman Population, 1830–1914: Demographic and Social Characteristics. Wisconsin: The University of Wisconsin Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Kolars, J., and H. J. Malin. 1970. “Population and Accessibility: An Analysis of Turkish Railroads.” The Geographical Review 60: 229–46.10.2307/213682Suche in Google Scholar

Lensink, R., and N. Hermes. 2004. “The Short-Term Effects of Foreign Bank Entry on Domestic Bank Behaviour: Does Economic Development matter?” Journal of Banking & Finance 28: 553–68.10.1016/S0378-4266(02)00393-XSuche in Google Scholar

Malueg, D. A., and M. Schwartz. 1991. “Preemptive Investment, Toehold, and the Mimicking Principle.” The RAND Journal of Economics 22: 1–13.10.2307/2601004Suche in Google Scholar

Owen, R. 2002. The Middle East in the World Economy, 1800–1914. London: Tauris and Co. Ltd.10.5040/9780755612246Suche in Google Scholar

Pamuk, Ş. 2000a. A Monetary History of the Ottoman Empire. New York: Cambridge University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Pamuk, Ş. 2000b. İstanbul ve diğer kentlerde 500 yıllık fiyatlar ve ücretler, 1469–1998. Ankara: Devlet İstatistik Enstitüsü.Suche in Google Scholar

Pamuk, Ş. 2004. “Prices in the Ottoman Empire, 1469–1914.” International Journal Middle East Studies 36: 451–68.Suche in Google Scholar

Quataert, D. 1995. “The Age of Reforms, 1812–1914.” In An Economic and Social History of the Ottoman Empire, 1300–1914, edited by H. İnalcık and D. Quataert, 759–934. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Reid, G. C. 1995. “Early Life-Cycle Behaviour of Micro-Firms in Scotland.” Small Business 7: 89–95.10.1007/BF01108684Suche in Google Scholar

Schoenberg, P. E. 1977. “The Evolution of Transport in Turkey (Eastern Thrace and Asia Minor) under Ottoman Rule, 1856–1918.” Middle Eastern Studies 13: 359–72.10.1080/00263207708700358Suche in Google Scholar

Thobie, J. 1991. European Banks in the Middle East. In International Banking, 1870–1914, edited by R. Cameron and V. I. Bovykin, 406–43. New York: Oxford University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Toprak, Z. 2008. “The Financial Structure of the Stock Exchange in the Late Ottoman Empire.” In East Meets West: Banking, Commerce and Investment in the Ottoman Empire, edited by P. L. Cottrell, M. Pohle, and I. L. Fraser, 143–61. Hampshire: Ashgate Publishing Limited.Suche in Google Scholar

Unite, A. A., and M. J. Sullivan. 2003. “The Effect of Foreign Entry and Ownership Structure on the Philippine Domestic Banking Market.” Journal of Banking & Finance 27: 23–45.10.1016/S0378-4266(02)00330-8Suche in Google Scholar

Xu, Y. 2011. “Towards a More Accurate Measure of Foreign Bank Entry and Its Impact on Domestic Banking Performance: The Case of China.” Journal of Banking & Finance 35: 886–90.10.1016/j.jbankfin.2010.10.011Suche in Google Scholar

©2015 by De Gruyter

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Foreign Bank Entry in the Late Ottoman Empire: The Case of the Imperial Ottoman Bank

- Is Bigger Better for Egyptian Banks? An Efficiency Analysis of the Egyptian Banks during a Period of Reform 2000–2006

- Provisioning, Bank Behavior and Financial Crisis: Evidence from GCC Banks

- New Coincident and Leading Indexes for the Lebanese Economy

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Foreign Bank Entry in the Late Ottoman Empire: The Case of the Imperial Ottoman Bank

- Is Bigger Better for Egyptian Banks? An Efficiency Analysis of the Egyptian Banks during a Period of Reform 2000–2006

- Provisioning, Bank Behavior and Financial Crisis: Evidence from GCC Banks

- New Coincident and Leading Indexes for the Lebanese Economy