Abstract

The controlling shareholder of a company has the potential to extract private benefits of control (PBC). In contrast to shared benefits, PBC are proceeds that accrue only to the majority shareholders. They can take a variety of forms that range from outright theft to a (covert) compensation for private costs incurred in controlling the company. It is notoriously difficult to measure PBC and the literature only provides a rough guidance based on two methods: the control premium method and the voting premium method. These two methods are based on the logic that PBC must be the reason why the controlling shareholder pays a premium over the market price for a controlling block or why voting and non-voting shares are priced differently. This paper introduces a third method to estimate the PBC. We look at the discount (compared to a baseline valuation made at the controlling level) that minority shareholders ask to invest in a company. In the context of private companies, we find a discount of 16.72 % that translates into estimated PBC of 20.08 % (premium per share). We argue that the discount for lack of control can be explained as a discount for private benefits.

Exhibit A: Court Cases and Observations

| # | Date | Case | Obs. | Reporter |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3-May-2021 | Estate of Jackson v. Comm’r | 1 | T.C. Memo 2021-48 *; 2021 Tax Ct. Memo LEXIS 74 **; 121 T.C.M. (CCH) 1320 |

| 2 | 27-Oct-2020 | Lucero v. United States | 1 | 2020 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 199605 *; 2020 WL 6281591 |

| 3 | 10-Jun-2020 | Nelson v. Comm’r | 2 | T.C. Memo 2020-81 *; 2020 Tax Ct. Memo LEXIS 79 ** |

| 4 | 2-Mar-2020 | Grieve v. Comm’r | 2 | T.C. Memo 2020-28 *; 2020 Tax Ct. Memo LEXIS 28 ** |

| 5 | 19-Aug-2019 | Estate of Jones v. Comm’r | 2 | T.C. Memo 2019-101 *; 2019 Tax Ct. Memo LEXIS 108 ** |

| 6 | 26-Mar-2019 | Kress v. United States | 3 | 372 F. Supp. 3d 731 *; 2019 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 49850 **; 2019-1 U.S. Tax Cas. (CCH) P60,711 |

| 7 | 24-Oct-2018 | Estate of Streightoff v. Comm’r | 1 | T.C. Memo 2018-178 *; 2018 Tax Ct. Memo LEXIS 179 **; 116 T.C.M. (CCH) 437 |

| 8 | 9-Dec-2015 | Redstone v. Comm’r | 1 | T.C. Memo 2015-237 *; 2015 Tax Ct. Memo LEXIS 242 **; 110 T.C.M. (CCH) 564 |

| 9 | 11-Feb-2014 | Estate of Richmond v. Comm’r | 1 | T.C. Memo 2014-26 *; 2014 Tax Ct. Memo LEXIS 26 **; 107 T.C.M. (CCH) 1135 |

| 10 | 18-Oct-2013 | Estate of Tanenblatt v. Comm’r | 1 | T.C. Memo 2013-263 *; 2013 Tax Ct. Memo LEXIS 273 ** |

| 11 | 8-Apr-2013 | Estate of Koons v. Comm’r | 1 | T.C. Memo 2013-94 *; 2013 Tax Ct. Memo LEXIS 98 **; 105 T.C.M. (CCH) 1567 |

| 12 | 7-Feb-2013 | Estate of Kite v. Comm’r | 1 | T.C. Memo 2013-43 *; 2013 Tax Ct. Memo LEXIS 43 **; 105 T.C.M. (CCH) 1277 |

| 13 | 28-Jun-2011 | Estate of Gallagher v. Comm’r | 1 | 2011 Tax Ct. Memo LEXIS 150 *; T.C. Memo 2011-148; 101 T.C.M. (CCH) 1702 |

| 14 | 22-Jun-2011 | Estate of Giustina v. Comm’r | 1 | 2011 Tax Ct. Memo LEXIS 141 *; T.C. Memo 2011-141; 101 T.C.M. (CCH) 1676 |

| 15 | 13-May-2010 | Pierre v. Comm’r | 1 | 2010 Tax Ct. Memo LEXIS 143 *; T.C. Memo 2010-106; 99 T.C.M. (CCH) 1436 |

| 16 | 2-Oct-2009 | Estate of Murphy v. United States | 3 | 2009 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 94923 *; 2009-2 U.S. Tax Cas. (CCH) P60,583; 104 A.F.T.R.2d (RIA) 2009-7703 |

| 17 | 29-Jan-2009 | Estate of Marjorie deGreeff Litchfield v. Comm’r | 2 | 2009 Tax Ct. Memo LEXIS 21 *; T.C. Memo 2009-21; 97 T.C.M. (CCH) 1079 |

| 18 | 22-Jul-2008 | Bergquist v. Comm’r | 2 | 131 T.C. 8 *; 2008 U.S. Tax Ct. LEXIS 20 **; 131 T.C. No. 2 |

| 19 | 27-May-2008 | Holman v. Comm’r | 3 | 130 T.C. 170 *; 2008 U.S. Tax Ct. LEXIS 12 **; 130 T.C. No. 12 |

| 20 | 5-May-2008 | Astleford v. Comm’r | 3 | 2008 Tax Ct. Memo LEXIS 129 *; T.C. Memo 2008-128; 95 T.C.M. (CCH) 1497 |

| 21 | 28-Sep-2006 | Dallas v. Comm’r | 2 | 2006 Tax Ct. Memo LEXIS 216 *; T.C. Memo 2006-212; 92 T.C.M. (CCH) 313 |

| 22 | 9-May-2006 | Huber v. Comm’r | 1 | 2006 Tax Ct. Memo LEXIS 97 *; T.C. Memo 2006-96; 91 T.C.M. (CCH) 1132; RIA TM 56510 |

| 23 | 10-Mar-2006 | Temple v. United States | 4 | 423 F. Supp. 2d 605 *; 2006 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 16171 **; 2006-1 U.S. Tax Cas. (CCH) P60,523; 97 A.F.T.R.2d (RIA) 2006-1649 |

| 24 | 11-Oct-2005 | Estate of Kelley v. Comm’r | 1 | 2005 Tax Ct. Memo LEXIS 236 *; T.C. Memo 2005-235; 90 T.C.M. (CCH) 369 |

| 25 | 31-May-2005 | Estate of Jelke v. Comm’r | 1 | 2005 Tax Ct. Memo LEXIS 128 *; T.C. Memo 2005-131; 89 T.C.M. (CCH) 1397 |

| 26 | 15-Mar-2005 | Estate of Bongard v. Comm’r | 2 | 124 T.C. 95 *; 2005 U.S. Tax Ct. LEXIS 8 **; 124 T.C. No. 8 |

| 27 | 26-Jul-2004 | Estate of Thompson v. Comm’r | 1 | 499 F.3d 129 *; 2007 U.S. App. LEXIS 20066 **; 2007-2 U.S. Tax Cas. (CCH) P60,546; 100 A.F.T.R.2d (RIA) 2007-5792 |

| 28 | 29-Dec-2003 | Estate of Green v. Comm’r | 1 | 2003 Tax Ct. Memo LEXIS 348 *; T.C. Memo 2003-348; 86 T.C.M. (CCH) 758; RIA TM 55384 |

| 29 | 25-Sep-2003 | Peracchio v. Comm’r | 1 | 2003 Tax Ct. Memo LEXIS 279 *; T.C. Memo 2003-280; 86 T.C.M. (CCH) 412 |

| 30 | 3-Sep-2003 | Lappo v. Comm’r | 2 | 2003 Tax Ct. Memo LEXIS 257 *; T.C. Memo 2003-258; 86 T.C.M. (CCH) 333 |

| 31 | 20-Aug-2003 | Hess v. Comm’r | 1 | 2003 Tax Ct. Memo LEXIS 250 *; T.C. Memo 2003-251; 86 T.C.M. (CCH) 303 |

| 32 | 13-Jun-2003 | Estate of Deputy v. Comm’r | 1 | 2003 Tax Ct. Memo LEXIS 174 *; T.C. Memo 2003-176; 85 T.C.M. (CCH) 1497 |

| 33 | 14-May-2003 | McCord v. Comm’r | 1 | 120 T.C. 358 *; 2003 U.S. Tax Ct. LEXIS 16 **; 120 T.C. No. 13 |

| 34 | 23-Aug-2002 | Okerlund v. United States | 2 | 53 Fed. Cl. 341 *; 2002 U.S. Claims LEXIS 221 **; 2002-2 U.S. Tax Cas. (CCH) P60,447; 90 A.F.T.R.2d (RIA) 2002-6124 |

| 35 | 1-Aug-2002 | Dunn v. Comm’r | 1 | 301 F.3d 339 *; 2002 U.S. App. LEXIS 15453 **; 59 Fed. R. Serv. 3d (Callaghan) 529 |

| 36 | 17-Jun-2002 | Estate of Bailey v. Comm’r | 1 | 2002 Tax Ct. Memo LEXIS 159 *; T.C. Memo 2002-152; 83 T.C.M. (CCH) 1862; T.C.M. (RIA) 54788 |

| 37 | 9-Apr-2002 | Estate of Mitchell v. Comm’r | 1 | 2002 Tax Ct. Memo LEXIS 100 *; T.C. Memo 2002-98; 83 T.C.M. (CCH) 1524; T.C.M. (RIA) 54715 |

| 38 | 5-Feb-2002 | Estate of Heck v. Comm’r | 1 | 2002 Tax Ct. Memo LEXIS 38 *; T.C. Memo 2002-34; 83 T.C.M. (CCH) 1181; T.C.M. (RIA) 54639 |

| 39 | 3-Oct-2001 | Estate of Elma Middleton Dailey v. Comm’r | 2 | 2001 Tax Ct. Memo LEXIS 299 *; T.C. Memo 2001-263; 82 T.C.M. (CCH) 710 |

| 40 | 24-Aug-2001 | Adams v. United States | 1 | 2001 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 13092 *; 2001-2 U.S. Tax Cas. (CCH) P60,418; 88 A.F.T.R.2d (RIA) 2001-6057 |

| 41 | 6-Jul-2001 | Estate of H.A. True v. Comm’r | 9 | 2001 Tax Ct. Memo LEXIS 199 *; T.C. Memo 2001-167; 82 T.C.M. (CCH) 27 |

| 42 | 9-May-2001 | Estate of Marcia P. Hoffman v. Comm’r | 1 | 2001 Tax Ct. Memo LEXIS 136 *; T.C. Memo 2001-109; 81 T.C.M. (CCH) 1588 |

| 43 | 27-Mar-2001 | Wall v. Comm’r | 1 | 2001 Tax Ct. Memo LEXIS 97 *; T.C. Memo 2001-75; 81 T.C.M. (CCH) 1425 |

| 44 | 6-Mar-2001 | Estate of Jones v. Comm’r | 2 | 116 T.C. 121 *; 2001 U.S. Tax Ct. LEXIS 11 **; 116 T.C. No. 10; 116 T.C. No. 11 |

| 45 | 2-Feb-2001 | Janda v. Comm’r | 1 | 2001 Tax Ct. Memo LEXIS 34 *; T.C. Memo 2001-24; 81 T.C.M. (CCH) 1100; T.C.M. (RIA) 54231 |

| 46 | 30-Nov-2000 | Knight v. Comm’r | 1 | 115 T.C. 506 *; 2000 U.S. Tax Ct. LEXIS 88 **; 115 T.C. No. 36 |

| 47 | 18-Aug-2000 | Estate of Borgatello v. Comm’r | 1 | 2000 Tax Ct. Memo LEXIS 309 *; T.C. Memo 2000-264; 80 T.C.M. (CCH) 260; T.C.M. (RIA) 54013 |

| 48 | 4-Aug-2000 | Godley v. Comm’r | 4 | 2000 Tax Ct. Memo LEXIS 284 *; T.C. Memo 2000-242; 80 T.C.M. (CCH) 158; T.C.M. (RIA) 53984 |

| 49 | 27-Jun-2000 | Estate of Klauss v. Comm’r | 1 | 2000 Tax Ct. Memo LEXIS 228 *; T.C. Memo 2000-191; 79 T.C.M. (CCH) 2177; T.C.M. (RIA) 53923 |

| 50 | 11-Apr-2000 | Estate of Maggos v. Comm’r | 1 | 2000 Tax Ct. Memo LEXIS 154 *; T.C. Memo 2000-129; 79 T.C.M. (CCH) 1861 |

| 51 | 20-Mar-2000 | Gow v. Comm’r | 4 | 2000 Tax Ct. Memo LEXIS 108 *; T.C. Memo 2000-93; 79 T.C.M. (CCH) 1680 |

| 52 | 15-Feb-2000 | Estate of Weinberg v. Comm’r | 1 | 2000 Tax Ct. Memo LEXIS 58 *; T.C. Memo 2000-51; 79 T.C.M. (CCH) 1507 |

| 53 | 5-Nov-1999 | Estate of Smith v. Comm’r | 2 | 1999 Tax Ct. Memo LEXIS 425 *; T.C. Memo 1999-368; 78 T.C.M. (CCH) 745 |

| 54 | 14-Oct-1999 | Estate of Marmaduke v. Comm’r | 2 | 1999 Tax Ct. Memo LEXIS 397 *; T.C. Memo 1999-342; 78 T.C.M. (CCH) 590 |

| 55 | 23-Aug-1999 | Estate of Hendrickson v. Comm’r | 1 | 1999 Tax Ct. Memo LEXIS 318 *; T.C. Memo 1999-278; 78 T.C.M. (CCH) 322; T.C.M. (RIA) 99278 |

| 56 | 29-Jul-1999 | Gross v. Comm’r | 1 | 1999 Tax Ct. Memo LEXIS 290 *; T.C. Memo 1999-254; 78 T.C.M. (CCH) 201; T.C.M. (RIA) 99254 |

| 57 | 10-Mar-1999 | Desmond v. Comm’r | 1 | 1999 Tax Ct. Memo LEXIS 84 *; T.C. Memo 1999-76; 77 T.C.M. (CCH) 1529; T.C.M. (RIA) 99076 |

| 58 | 17-Nov-1998 | Barnes v. Comm’r | 2 | 1998 Tax Ct. Memo LEXIS 410 *; T.C. Memo 1998-413; 76 T.C.M. (CCH) 881; T.C.M. (RIA) 98413 |

| 59 | 8-Aug-1998 | King v. Comm’r (Estate of Brookshire) | 1 | 1998 Tax Ct. Memo LEXIS 370 *; T.C. Memo 1998-365; 76 T.C.M. (CCH) 659 |

| 60 | 30-Jun-1998 | Estate of Davis v. Comm’r | 1 | 110 T.C. 530 *; 1998 U.S. Tax Ct. LEXIS 35 **; 110 T.C. No. 35 |

| 61 | 30-Apr-1998 | Furman v. Comm’r | 2 | 1998 Tax Ct. Memo LEXIS 158 *; T.C. Memo 1998-157; 75 T.C.M. (CCH) 2206 |

| 62 | 19-Mar-1998 | Dockery v. Comm’r | 2 | 1998 Tax Ct. Memo LEXIS 114 *; T.C. Memo 1998-114; 75 T.C.M. (CCH) 2032 |

| 63 | 27-Oct-1997 | Estate of Fleming v. Comm’r | 1 | 1997 Tax Ct. Memo LEXIS 566 *; T.C. Memo 1997-484; 74 T.C.M. (CCH) 1049; 3 U.S. Tax Cas. (CCH) P45,035 |

| 64 | 5-Feb-1997 | Gray v. Comm’r | 1 | 1997 Tax Ct. Memo LEXIS 66 *; T.C. Memo 1997-67; 73 T.C.M. (CCH) 1940 |

| 65 | 26-Aug-1996 | Estate of Barudin v. Comm’r | 1 | 1996 Tax Ct. Memo LEXIS 403 *; T.C. Memo 1996-395; 72 T.C.M. (CCH) 488 |

| 66 | 11-Mar-1996 | Kosman v. Comm’r | 3 | 1996 Tax Ct. Memo LEXIS 107 *; T.C. Memo 1996-112; 71 T.C.M. (CCH) 2356 |

| 67 | 4-Dec-1995 | Wheeler v. United States | 1 | 1995 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 21432 *; 77 A.F.T.R.2d (RIA) 96-1405 |

| 68 | 7-Aug-1995 | Estate of McCormick v. Comm’r | 4 | 1995 Tax Ct. Memo LEXIS 367 *; T.C. Memo 1995-371; 70 T.C.M. (CCH) 318 |

| 69 | 12-Jun-1995 | Mandelbaum v. Comm’r | 1 | 1995 Tax Ct. Memo LEXIS 256 *; T.C. Memo 1995-255; 69 T.C.M. (CCH) 2852 |

| 70 | 28-Mar-1995 | Estate of Frank v. Comm’r | 1 | 1995 Tax Ct. Memo LEXIS 178 *; T.C. Memo 1995-132; 69 T.C.M. (CCH) 2255 |

| 71 | 27-Oct-1994 | Estate of Luton v. Comm’r | 2 | 1994 Tax Ct. Memo LEXIS 550 *; T.C. Memo 1994-539; 68 T.C.M. (CCH) 1044 |

| 72 | 19-Oct-1994 | Estate of Lauder v. Comm’r | 1 | 1994 Tax Ct. Memo LEXIS 535 *; T.C. Memo 1994-527; 68 T.C.M. (CCH) 985 |

| 73 | 11-May-1994 | Estate of Simpson v. Comm’r | 2 | 1994 Tax Ct. Memo LEXIS 217 *; T.C. Memo 1994-207; 67 T.C.M. (CCH) 2938 |

| 74 | 8-Dec-1993 | Estate of Ford v. Comm’r | 6 | 1993 Tax Ct. Memo LEXIS 595 *; T.C. Memo 1993-580; 66 T.C.M. (CCH) 1507 |

| 75 | 10-Nov-1993 | Estate of Jung v. Comm’r | 1 | 101 T.C. 412 *; 1993 U.S. Tax Ct. LEXIS 69 **; 101 T.C. No. 28 |

| 76 | 1-Feb-1993 | Estate of Bennett v. Comm’r | 1 | 1993 Tax Ct. Memo LEXIS 47 *; T.C. Memo 1993-34; 65 T.C.M. (CCH) 1816 |

| 77 | 30-Aug-1990 | Estate of Murphy v. Comm’r | 1 | 1990 Tax Ct. Memo LEXIS 520 *; T.C. Memo 1990-472; 60 T.C.M. (CCH) 645; T.C.M. (RIA) 90472 |

| 78 | 1-Aug-1990 | Estate of Lenheim v. Comm’r | 5 | 1990 Tax Ct. Memo LEXIS 420 *; T.C. Memo 1990-403; 60 T.C.M. (CCH) 356; T.C.M. (RIA) 90403 |

| 79 | 31-May-1990 | Estate of Dougherty v. Comm’r | 1 | 1990 Tax Ct. Memo LEXIS 292 *; T.C. Memo 1990-274; 59 T.C.M. (CCH) 772; T.C.M. (RIA) 90274 |

| 80 | 28-Feb-1990 | Estate of Newhouse v. Comm’r | 1 | 94 T.C. 193 *; 1990 U.S. Tax Ct. LEXIS 9 **; 94 T.C. No. 14 |

| TOTAL NUMBER OF OBSERVATIONS | 137 | |||

Exhibit B: Descriptive Statistics

A. Dependent Variable (DLOC)

A.1. Sample Including Controlling Stakes

| N | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Std. deviation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DLOC | 137 | 0.00 | 62.87 | 13.79 | 9.27 |

A.2. Sample Excluding Controlling Stakes

| N | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Std. deviation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DLOC | 106 | 3.30 | 62.87 | 16.72 | 7.89 |

B. Independent Variables

We report descriptive statistics (frequencies) for the main independent variable below. The missing information corresponds to the cases and observations for which there is no information available or for which the independent reviewers came to conflicting conclusions

| Categorical variables | 1 | 0 | Missing | Total (N) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 26 | 106 | 5 | 137 |

C. Control Variables

We report key statistics for the continuous and categorical control variables below. The missing values correspond to the observations for which the independent reviewers could not determine the value in an unequivocal way.

The regression results have been checked on the absence of multicollinearity. This situation occurs when the predictor variables are highly correlated with each other; in this case, the regression model would not be able to accurately associate variance in the outcome variable with the correct predictor variable, leading to muddled results and incorrect inferences. Multicollinearity has been checked using the variance inflation factor values (not reported).

| Continuous variables | N | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Std. deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Company size ($M) | 137 | 0.20 | 3,141.98 | 120.27 | 372.02 |

| Size of interest (%) | 133 | 0.12 | 100.00 | 35.84 | 28.63 |

| Spread (0–200) | 137 | 3.28 | 200.00 | 64.23 | 34.62 |

| Categorical variables | 1 | 0 | Missing | Total (N) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Audit | 22 | 115 | 0 | 137 |

| Profitable | 117 | 14 | 6 | 137 |

| Board | 85 | 50 | 2 | 137 |

| Operating | 80 | 57 | 0 | 137 |

| Division | Industry | SIC range | Number of observations |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | Agriculture, forestry, & fishing | 01–09 | 7 |

| B | Mining | 10–14 | 2 |

| C | Construction | 15–17 | 4 |

| D | Manufacturing | 20–39 | 14 |

| E | Transportation & public utilities | 40–49 | 9 |

| F | Wholesale trade | 50–51 | 5 |

| G | Retail trade | 52–59 | 8 |

| H | Finance, insurance, & real estate | 60–67 | 76 |

| I | Services | 70–89 | 12 |

| J | Public administration | 91–98 | 0 |

| K | Non classifiable establishments | 99 | 0 |

| TOTAL | 137 | ||

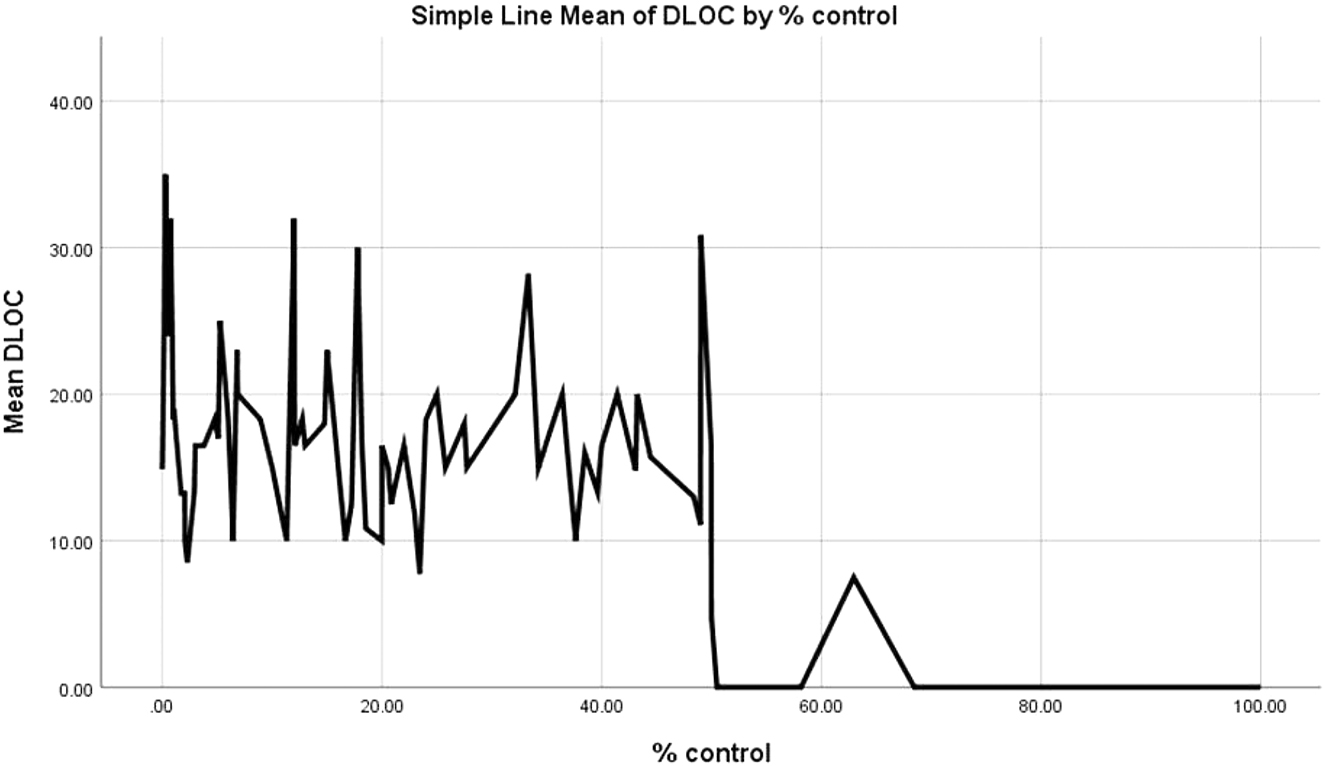

Exhibit C: Impact of Control Rights on DLOC

We observe that in exceptional cases, a DLOC is applied to a controlling stake. For example, in Gray v. Commissioner (66 T.C.M. (CCH) 254 (1993)), the Tax Court applied a discount on a stake that represented 50.487 % of the voting stock of a corporation. The court pointed to the “substantial size of the minority interest and the potential for dissension and legal complications in the event of a liquidation…” (Id.).

Exhibit D: Robustness Test – Regression Results Excluding Controlling Stakes

As we have found, unsurprisingly, that control has a major impact on the DLOC, we run a separate test for all observations in which a non-controlling stake is valued (i.e., we exclude 26 observations for controlling stakes and 5 observations for which the reviewers could not unequivocally confirm that the valuation subject had 50 % or more of the control rights). The second regression is thus based on 106 observations for which we retain the same independent variables (to the exclusion of the dummy for control which makes no sense in this test).[32]

The purpose of the second exercise is twofold: first we want to check whether our conclusions hold for the non-controlling stakes only and second we want to check the R-squared of the model. We do expect a significant drop in R-squared (as we take out the controlling stakes for which we have nearly consistent zero DLOC observations as shown in Exhibit C). However, we hope to retain an acceptable R-squared for the second model with variables that remain statistically relevant. These effects will allow us to verify that the DLOC is impacted by other factors than control and that DLOC and PBC share common determinants (thus allowing us to validate our central hypothesis that the DLOC can be seen as the mirror image of the PBC and used as an alternative method to estimate their size).

| Model | B | Std. error | Beta | t | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 14.173 | 3.109 | 4.559 | 0.000 | |

| Logsize | −1.177 | 0.440 | −0.257 | −2.674 | 0.009 |

| % Cash flow rights | −0.044 | 0.031 | −0.139 | −1.414 | 0.161 |

| Audit | −2.032 | 2.227 | −0.086 | −0.913 | 0.364 |

| Profit | 2.249 | 2.341 | 0.095 | 0.961 | 0.339 |

| Operating | 7.412 | 1.611 | 0.462 | 4.602 | 0.000 |

| Board | −2.456 | 1.742 | −0.152 | −1.410 | 0.162 |

| Spread | 0.052 | 0.021 | 0.234 | 2.446 | 0.016 |

| R-squared | 30.4 % | ||||

| Adjusted R-squared | 25.2 % |

The second model confirms the decisive impact of control on the DLOC (as shown by the difference in R-squared between the two models). However, the model also shows that the DLOC is impacted by the same variables as the first model: the spread and the operating character of the company. In addition, the (log)size becomes relevant at the 5 % level. As the coefficient is difficult to interpret because of the log transformation, we find it sufficient to report a negative relationship between size and PBC, as also found by Zingales (1995), Nenova (2003) and Luo et al. (2012).

The other variables are not relevant at the 5 % level but have all the sign expected by theory. We point to the negative impact of cash flow rights on the DLOC. We believe that an increased equity stake might incentivize the shareholders to step up their monitoring efforts (a suggestion raised by Gilson and Schwartz 2012: 35). We also note that the presence of a board of directors tends to reduce the DLOC. It seems thus that, to a certain extent, minority shareholders rely on the board to counter tunneling attempts by the controlling shareholder(s).

The other variables have P-values that are far above conventional relevance levels. These statistically irrelevant items include, counterintuitively, the variable “audit” for which we have no ready explanation. Indeed, we would expect that minority shareholders rely rather on an external audit to expose possible expropriation by the controlling shareholders than on board members that are supposedly appointed by or with the implicit approval of the controlling shareholders. A possible explanation (in line with arguments set out by Dyck and Zingales 2004) is that shareholders rely rather on tax compliance and enforcement, especially in a country with a sophisticated administration such as the United States.

Exhibit E: Dealing with Selection Bias

The sample of court cases used in our study might be subject to a selection bias in that only a limited number of cases are finally decided by a court of law and that an undefined number of cases are settled before that stage.

We present below our view on this potential bias (A), implement a strategy to test whether the exclusion of settlements has an impact on our conclusions (B), and summarize our findings (C).

A. The Exclusion of Settlements is Unlikely to Have an Impact on the DLOC

The dependent variable in our regression is the Discount for Lack of Control (DLOC) applied to a minority stake in a private company. We see no obvious reason why the DLOC in a settlement would be materially different from the DLOC in a court decision.

On the contrary: the published DLOCs decided by courts are likely to be the main source of information for settlement discussions. The parties know that the alternative to a settlement is a court decision, and thus a DLOC in a settlement is presumably informed and inspired by the average DLOC decided by courts.

B. What is the Possible Impact of Excluding Settled Cases?

The expected payoff from litigation for parties depends on the amount at stake, the win probability, and the litigation cost (Hylton and Kim 2023). In other words, parties will only prefer litigation over a settlement if the expected award (payoff) justifies the cost of litigation.

We have collected metadata to estimate the cost of ligation (in particular the number of attorneys, the complexity of the case as proxied by the length of the court opinion and the time in litigation). Eventually we decided to only retain the first two elements in a truncated regression with unobserved and stochastic settlement thresholds as proposed by Hylton and Kim (2023). The Hylton & Kim model also uses these two variables and our results showed that the third variable (time in litigation) was not relevant.[33]

| Regression model | OLS | MLE |

|---|---|---|

| Constant | 13.487*** (2.861) | 12.215*** (3.912) |

| Logsize | −0.596 (0.363) | −1.327** (0.551) |

| Control | −15.214*** (2.001) | −43.073*** (7.745) |

| % Cash flow rights | −0.035 (0.028) | −0.057 (0.038) |

| Audit | −3.743* (1.898) | −3.886 (2.610) |

| Profit | 1.496 (2.103) | 3.027 (2.796) |

| Operating | 5.371*** (1.394) | 8.341*** (2.066) |

| Board | −1.251 (1.458) | −2.248 (2.038) |

| Spread | 0.050** (0.020) | 0.060** (0.026) |

-

Standard errors in parentheses. *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1.

The maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) regression results allow us to confirm the impact of the operating character and the spread on the DLOC. We note that in this model, the size of the effect is even accentuated. Interestingly, we note that the (log)size of the company becomes significant and that there is a clear and important negative relation between the size of the company and the DLOC (see also the results of the robustness check presented in Exhibit D). All coefficients in the MLE model retain the positive or negative sign predicted by theory.

C. Conclusions

We acknowledge the concern that court decisions by definition are limited to cases that fail to settle at some point in the dispute resolution process.

In the case of our dataset and research question, we believe that this concern is mitigated by the nature of our dependent variable, being a percentage discount for which settled cases are most likely informed and inspired by court decisions.

Additionally, we applied the methodology proposed by Hylton and Kim (2023) to verify whether a maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) regression would lead to different results. This is not the case. The MLE coefficients confirm the conclusions of our paper. Indeed, we note that the same variables remain relevant, thus allowing us to confirm the interpretation and conclusions we set out in the body of our text.

References

Albuquerque, R., and E. Schroth. 2010. “Quantifying Private Benefits of Control from a Structural Model of Block Trades.” Journal of Financial Economics 96: 33–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2009.12.003.Suche in Google Scholar

Albuquerque, R., and E. Schroth. 2015. “The Value of Control and the Costs of Illiquidity.” The Journal of Finance 70 (4): 1405–55. https://doi.org/10.1111/jofi.12207.Suche in Google Scholar

Barak, R., and B. Lauterbach. 2011. “Estimating the Private Benefits of Control from Partial Control Transfers: Methodology and Evidence.” International Journal of Corporate Governance 2 (3/4): 183–200. https://doi.org/10.1504/ijcg.2011.044374.Suche in Google Scholar

Barclay, M. J., and C. G. Holderness. 1989. “Private Benefits from Control of Public Corporations.” Journal of Financial Economics 25 (2): 371–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-405x(89)90088-3.Suche in Google Scholar

Bruner, R., and M. Palacios. 2004. “Valuing Control and Marketability.” Batten Institute Working Paper, available at SSRN.10.2139/ssrn.553562Suche in Google Scholar

Choi, A. 2018. “Concentrated Ownership and Long-Term Shareholder Value.” Harvard Business Law Review 8: 53–99.Suche in Google Scholar

de Fontenay, E. 2017. “The Deregulation of Private Capital and the Decline of the Public Company.” Hastings Law Journal 68: 445–502.Suche in Google Scholar

Doidge, C. 2004. “U.S. Cross-Listings and the Private Benefits of Control: Evidence from Dual-Class Firms.” Journal of Financial Economics 72: 519–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0304-405x(03)00208-3.Suche in Google Scholar

Dyck, A., and L. Zingales. 2004. “Private Benefits of Control: An International Comparison.” The Journal of Finance 59 (2): 537–600. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2004.00642.x.Suche in Google Scholar

Gilson, R. J., and A. Schwartz. 2012. “Contracting About Private Benefits of Controls.” Columbia University Center for Law & Economics Studies, Research Paper No. 436, 1–42.10.2139/ssrn.2182781Suche in Google Scholar

Gregoric, A., and C. Vespro. 2008. “Block Trades and the Benefits of Control in Slovenia.” The Economics of Transition 17: 175–210. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0351.2009.00332.x.Suche in Google Scholar

Grossman, S., and O. Hart. 1988. “One Share/One Vote and the Market for Corporate Control.” Journal of Financial Economics 20: 175–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-405x(88)90044-x.Suche in Google Scholar

Holmen, M., and J. D. Knopf. 2004. “Minority Shareholder Protections and the Private Benefits of Control for Swedish Mergers.” Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 39 (1): 167–91. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0022109000003938.Suche in Google Scholar

Hylton, K. N., and S. Kim. 2023. “Trial Selection and Estimating Damages Equations.” Review of Law & Economics: 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1515/rle-2023-0020.Suche in Google Scholar

Johnson, S., R. La Porta, F. Lopez-de-Silanes, and A. Shleifer. 2000. “Tunneling.” The American Economic Review 90 (2): 22–7. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.90.2.22.Suche in Google Scholar

Leacock, S. 2016. “Lack of Marketability and Minority Discounts in Valuing Close Corporation Stock: Elusiveness and Judicial Synchrony in Pursuit of Equitable Consensus.” William and Mary Business Law Review 7: 683.Suche in Google Scholar

Lease, R. C., J. J. McConnel, and W. Mikkelson. 1983. “The Market Value of Control in Publicly-Traded Corporations.” Journal of Financial Economics 11: 439–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-405x(83)90019-3.Suche in Google Scholar

Lee, H.-C. 2004. “The Hidden Costs of Private Benefits of Control: Value Shift and Efficiency.” The Journal of Corporation Law 29 (4): 719–34.Suche in Google Scholar

Luo, J.-H., D.-F. Wan, and D. Cai. 2012. “The Private Benefits of Control in Chinese Listed Firms: Do Cash Flow Rights Always Reduce Controlling Shareholders’ Tunneling?” Asia Pacific Journal of Management 29: 499–518. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-010-9211-y.Suche in Google Scholar

Massari, M., V. Monge, and L. Zanetti. 2006. “Control Premium in Legally Constrained Markets for Corporate Control: The Italian Case (1993–2003).” Journal of Management & Governance 10: 77–110. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10997-005-3560-9.Suche in Google Scholar

Matthews, G. E. 2017a. “Statutory Fair Value in Dissenting Shareholder Cases: Part I.” Business Valuation Review 36 (1): 15–31, https://doi.org/10.5791/0882-2875-36.1.15.Suche in Google Scholar

Matthews, G. E. 2017b. “Statutory Fair Value in Dissenting Shareholder Cases: Part II.” Business Valuation Review 36 (2): 54–66, https://doi.org/10.5791/bvr-d-17-0005.1.Suche in Google Scholar

Mikkelson, W., and H. Regassa. 1991. “Premiums Paid in Block Transactions.” Managerial and Decision Economics 12 (6): 511–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/mde.4090120612.Suche in Google Scholar

Milosevic, D. 2014. “Private Benefits from Control of Public Corporations.” Journal of Financial Economics: 371–9.Suche in Google Scholar

Muravyev, A., I. Berezinets, and Y. Ilina. 2014. “The Structure of Corporate Boards and Private Benefits of Control: Evidence from the Russian Stock Exchange.” International Review of Financial Analysis 34: 247–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irfa.2014.03.008.Suche in Google Scholar

Nenova, T. 2003. “The Value of Corporate Voting Rights and Control: A Cross-Country Analysis.” Journal of Financial Economics 68: 325–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0304-405x(03)00069-2.Suche in Google Scholar

Nicodano, G., and A. Sembenelli. 2004. “Private Benefits, Block Transaction Premiums and Ownership Structure.” International Review of Financial Analysis 13: 227–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irfa.2004.02.006.Suche in Google Scholar

Pérez-Soba, I., A. Martinez-Canete, and E. Marquez-de-la-Cruz. 2021. “Private Benefits from Control Block Trades in the Spanish Stock Exchange.” The North American Journal of Economics and Finance 56: 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.najef.2020.101338.Suche in Google Scholar

Pratt, S. P. 2008. Valuing a Business, 5th Edition: The Analysis and Appraisal of Closely Held Companies. New York: McGraw Hill Professional.Suche in Google Scholar

Reilly, R., and A. Rotkowski. 2007. “The Discount for Lack of Marketability: Update on Current Studies and Analysis of Current Controversies.” Tax Lawyer 61 (1): 241–86.Suche in Google Scholar

Rydqvist, K. 1996. “Takeover Bids and the Relative Prices of Shares that Differ in Their Voting Rights.” Journal of Banking & Finance 20: 1407–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-4266(95)00042-9.Suche in Google Scholar

Sauerwald, S., P. Heugens, R. Turturea, and M. van Essen. 2019. “Are All Private Benefits of Control Ineffective? Principal–Principal Benefits, External Governance Quality, and Firm Performance.” Journal of Management Studies 56: 725–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12420.Suche in Google Scholar

Trojanowski, G. 2008. “Equity Block Transfers in Transition Economies: Evidence from Poland.” Economic Systems 32: 217–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecosys.2007.11.002.Suche in Google Scholar

Van den Cruijce, J. 2022. “The Impact of Control on the Discount for Lack of Marketability.” Tax Notes Federal 175 (4).Suche in Google Scholar

Weifeng, H., Z. Zhaoguo, and Z. Shasha. 2008. “Ownership Structure and the Private Benefits of Control: An Analysis of Chinese Firms.” Corporate Governance: International Journal of Business in Society 8 (3): 286–98. https://doi.org/10.1108/14720700810879178.Suche in Google Scholar

Wertheimer, B. 1998. “The Shareholders’ Appraisal Remedy and How Courts Determine Fair Value.” Duke Law Journal 47: 613–712. https://doi.org/10.2307/1372911.Suche in Google Scholar

Zingales, L. 1995. “What Determines the Value of Corporate Votes?” Quarterly Journal of Economics 110 (4): 1047–73. https://doi.org/10.2307/2946648.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Laudatio: Christoph Engel

- Articles

- Pre-Emptive Rights – A Theoretical and Empirical Examination

- The Value of Control in Private Companies

- The Direct Incidence of Product Liability on Wages

- The Hard Pursuit of Optimal Vaccination Compliance in Heterogeneous Populations

- Revival Churches Abuses and Well-Being in Cameroon

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Laudatio: Christoph Engel

- Articles

- Pre-Emptive Rights – A Theoretical and Empirical Examination

- The Value of Control in Private Companies

- The Direct Incidence of Product Liability on Wages

- The Hard Pursuit of Optimal Vaccination Compliance in Heterogeneous Populations

- Revival Churches Abuses and Well-Being in Cameroon