Abstract

Background and Objectives

Concomitant septic and crystal-induced arthritis is a rare condition. Failure to diagnose this condition can result in significant harm to the patient. This study aims to investigate the prevalence and characteristics of concomitant septic and crystal-induced arthritis.

Methods

A retrospective study included patients diagnosed with concomitant septic and crystal-induced arthritis confirmed by positive bacterial culture and intracellular crystals in synovial fluid of the same joint, from January 1, 2015, to July 31 ,2024.

Results

A total of 45 cases were defined as having the prevalence of concomitant septic and crystal-induced arthritis among patients with crystal-induced arthritis of 4% (45/1116). Demographic characteristics showed male predominance (73.3%) with a mean ± SD age of 62.8 ± 14.4 years. Acute monoarthritis (66.7%, n = 30), which primarily affected the knee (68.9%, n = 31), was the most common presentation. Fever was present in 95.6% of cases. The median synovial white blood cell (WBC) count was 61, 478 cells/μL (interquartile range: 33, 600–131, 030). The mean ± SD C-reactive protein (CRP) level was 215 ± 96.7 mg/L. Monosodium urate crystals were found in 80% (n = 36) of the cases. The predominant bacteria were Staphylococcus (48.9%, n = 22), with Methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) being the most common (28.9%, n = 13), followed by Streptococcus dysgalactiae (15.6%, n = 7) and gram-negative bacilli (15.6%, n = 7). The mortality rate was 15.6% (n = 7).

Conclusion

The prevalence of concomitant septic and crystal-induced arthritis was 4% among patients with crystal-induced arthritis, especially among those with acute fever and high synovial WBC counts. The chance of concomitant septic and crystal-induced arthritis is very low in cases with synovial WBC < 12,000 cells/μL.

Introduction

Crystal-induced arthritis is a common form of arthritis encountered in clinical practice, with gouty arthritis being the most prevalent. Its prevalence ranges from 0.9%–5.2%, with higher rates observed in Western countries.[1,2] The gold standard for diagnosing gout is the detection of intracellular monosodium urate (MSU) crystals in synovial fluid.[3] Calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate crystal deposition disease (CPPD) represents one of the most prevalent forms of crystal-induced arthritis, and is diagnosed by the detection of calcium pyrophosphate (CPP) crystals.[4] The exact prevalence of CPPD is unknown due to there being a variety of clinical subtypes, including asymptomatic chondrocalcinosis; however, the incidence increases with age. One study in the UK showed that the prevalence of knee CPPD was 7%–10% in patients > 60 years of age.[5] Septic arthritis occurs less frequently than crystal-induced arthritis; however, it is associated with a higher mortality rate of 11.5%.[6] As a rheumatological emergency, this condition exhibits an incidence rate of approximately 2–10 cases per 100,000 person-years in the general population. In particular, this rate increases significantly to 30–100 cases per 100,000 person-years among individuals with certain risk factors, including older adults, immunocompromised hosts, patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and those with prosthetic joints.[7, 8, 9, 10]

Diagnosis of septic arthritis can be challenging due to its symptoms and laboratory findings, such as acute monoarthritis or oligoarthritis with or without fever, high synovial fluid white blood cell (WBC) count, and leukocytosis, which are symptoms similar to those observed in crystal-induced arthritis.[11] Delayed diagnosis and treatment of septic arthritis can lead to joint damage and increased mortality, significantly impacting both short- and long-term quality of life.[12]

Differentiating between septic arthritis and crystal-induced arthritis presents a notable challenge, particularly when patients with existing crystal-induced arthritis may also develop concomitant septic arthritis.[11,13,14] The detection of crystals in synovial fluid does not exclude the possibility of concomitant septic and crystal-induced arthritis.[11,13, 14, 15]

Research surrounding concomitant septic and crystal-induced arthritis remains sparse, underscoring our motivation for this study. In this study, we aimed to investigate the prevalence and characteristics of concomitant septic and crystal-induced arthritis.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Study Populations

We conducted a retrospective study at Khon Kaen Hospital, a tertiary care center in the northeastern region of Thailand, focusing on patients with concomitant septic arthritis and crystal-induced arthritis between January 1, 2015 and July 31, 2024.

All patients who underwent synovial fluid analysis during the study period were included. Septic arthritis was defined as positive synovial fluid bacterial cultures and crystal-induced arthritis was identified by the presence of at least one intracellular crystal in the synovial fluid visualized under light or polarized light microscopy. Concomitant septic and crystal-induced arthritis indicates the simultaneous occurrence of both septic and crystal-induced arthritis in the same joint.

Study Processes

Our study consisted of three distinct steps.

First, eligible patients were selected from three data sources: I) the hospital’s electronic database, using the International Classification of Diseases 10th revision (ICD-10) codes M00, M10, and M11 for pyogenic arthritis, gout, and other crystal-induced arthropathies, respectively. II) The hospital laboratory database contained information regarding individuals who had undergone synovial fluid analysis. III) The Division of Rheumatology Service Database containing the results of light or polarized light microscopy examinations.

In the second step, septic and crystal-induced arthritis cases were identified from three databases for further analysis.

Finally, in the third step, we conducted a detailed analysis to determine the prevalence and characteristics of concomitant septic and crystal-induced arthritis.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Khon Kaen Hospital (protocol code: KEXP65061).

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using STATA software (Stata Corp, v. 13). Descriptive statistics were used based on data characteristics. Categorical variables such as sex, underlying disease, joint distribution, and mortality are presented as numbers and percentages. Continuous variables, including age, duration of pain, WBC count, and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels, were expressed as means with standard deviation (SD) or medians with interquartile ranges (IQR), depending on the distribution of the data.

Results

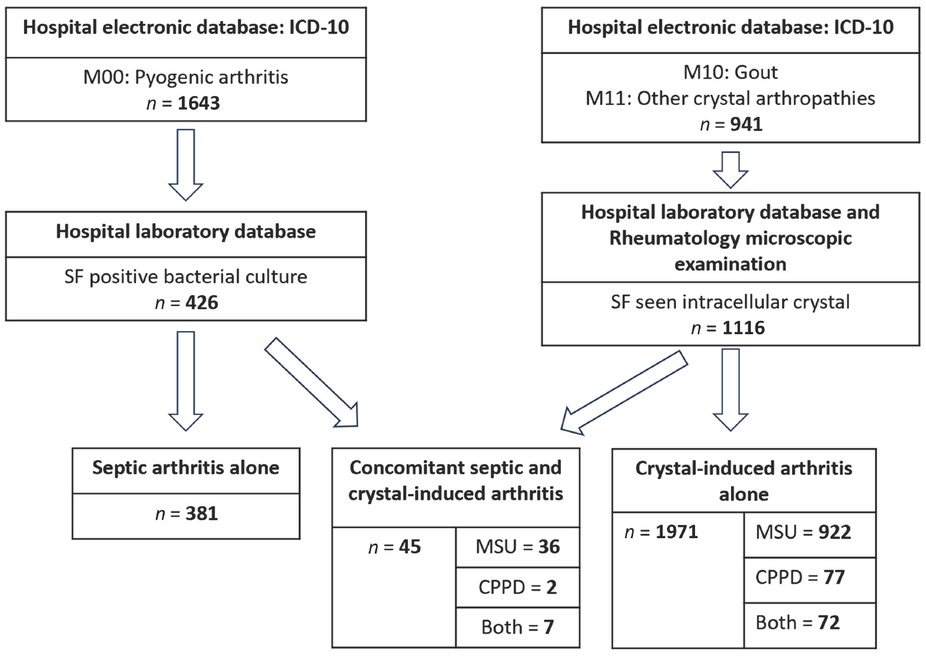

Initially, 2, 584 individuals were selected from the hospital’s electronic database based on the ICD-10 codes M00, M10, and M11. Subsequently, 426 patients with septic arthritis and 1116 with crystal-induced arthritis were identified from the hospital laboratory database. Among them, 50 patients initially showed positive findings for synovial fluid bacterial cultures and intracellular crystals; however, after excluding five patients due to probable contamination of the bacterial culture, 45 patients with concomitant septic and crystal-induced arthritis remained for inclusion in the study, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Patients enrollment. CPPD, calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate; ICD-10, International Classification of Diseases 10th Revision; MSUC, monosodium urate crystal; SF, synovial fluid.

Prevalence of Concomitant Septic and Crystal-induced Arthritis

The prevalence of concomitant septic and crystal-induced arthritis was 4% (45/1116).

Patient Baseline Clinical Characteristics

Table 1 summarizes the patient baseline characteristics, revealing that the majority of patients were male (73.3%) with a mean age (± SD) of 62.8 ± 14.4 years. Pre-existing gout was the most prevalent among underlying diseases (53.3%), with other conditions detailed in Table 1. The characteristics of each patient are presented in Table 2

Patient baseline characteristics

| Characteristics | Percent (Number) |

|---|---|

| Number of patients | 45 |

| Age, mean (SD)-years | 62.8 (14.4) |

| Male sex | 73.3 (33) |

| Duration of joint pain, median (IQR)-days* | 3 (2–7) |

| Fever | 95.6 (43) |

| Prior crystal attack | 53.3 (24) |

| Number of joints | |

| Monoarthritis | 66.7 (30) |

| Oligoarthritis | 31.1 (14) |

| Polyarthritis | 2.2 (1) |

| Joint involvement | |

| Knee | 68.9 (31) |

| Ankle | 28.9 (13) |

| Wrist | 15.6 (7) |

| Others; elbow, hip, shoulder | 13.3 (6) |

| SF WBC, median (IQR) [range]- cells/μL | 61, 478 (33,600–131,030) [12,095–463,220] |

| SF WBC | |

| ≤ 20, 000 cells/μL | 13.2 (5/38) |

| 20, 001–50, 000 cells/μL | 26.3 (10/38) |

| 50, 001–100, 000 cells/μL | 26.3 (10/38) |

| > 100, 000 cells/μL | 34.2 (13/38) |

| SF PMN, mean (SD)-% | 85.9 (12.6) |

| Blood WBC, mean (SD)- cells/μL | 16, 046 (8702) |

| CRP, mean (SD) [range]-mg/L | 215 (96.7) [82.2–379.8] |

| SF gram stain positive | 35.6 (16) |

| GPC | 39.5 (15/38) |

| GNB | 14.3 (1/7) |

| SF culture | |

| GPC | 84.4 (38) |

| Staphylococcus | 48.9 (22) |

| MSSA | 28.9 (13) |

| MRSA | 2.2 (1) |

| Streptococcus | 31.1 (14) |

| Streptococcus dysgalactiae | 15.6 (7) |

| Streptococcus agalactiae | 11.1 (5) |

| GNB | 15.6 (7) |

| SF crystal | |

| MSU | 80 (36) |

| CPPD | 4.4 (2) |

| Both | 15.6 (7) |

| Hemoculture | 15.6 (7) |

| GPC | 13.2 (5/38) |

| GNB | 28.6 (2/7) |

| Underlying disease before admission | |

| Pre-existing gout | 53.3 (24) |

| Hypertension | 48.9 (22) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 37.8 (17) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 22.2 (10) |

| Cirrhosis | 13.3 (6) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 11.1 (5) |

| Osteoarthritis | 6.7 (3) |

| Surgical drainage | 60 (27) |

| Outcome | |

| Death | 15.6 (7) |

| Recovery | 84.4 (38) |

CPPD: Calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate deposition disease, GNB: C-reactive protein (CRP), GPC: gram-negative bacilli, gram-positive cocci, IQR: interquartile range, MRSA: methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, MSSA: methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus, mg/L: milligrams per liter, MSU: monosodium urate crystal, PMN: polymorphonuclear leukocyte, SD: standard deviation, SF: synovial fluid, WBC: white blood cell. *Defined as the time from joint pain onset to the initial detection of either intra cellular crystal or microorganism (by culture) in the synovial fluid.

Characteristics of each patient

| No | Sex | Age | Fever | Onset (Day) | Joint | Underlying disease | SF - cells/WBC μL (%PMN) | Synovial fluid culture | Crystal | Positive HC | CRP (mg/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | 63 | Yes | 1 | Ankle | Gout, AF, HT | 141,900 (65) | MSSA | MSU | No | 252.2 |

| 2 | M | 65 | Yes | 1 | Ankle | Gout, AF, HT, MI | TNTC | MSSA | MSU | No | N/A |

| 3 | M | 49 | Yes | 2 | Ankle | Gout, HT | TNTC | MSSA | MSU | No | N/A |

| 4 | F | 55 | Yes | 2 | Knee | ITP, RA | 338,000 (65) | MSSA | Both | No | N/A |

| 5* | M | 76 | Yes | 3 | Knee | HT, CKD4 | 31,530 (46) | MSSA | MSU | No | N/A |

| 6 | M | 44 | Yes | 4 | Knee | - | 463,220 (72) | MSSA | MSU | No | 221 |

| 7 | M | 45 | Yes | 4 | Ankle, Knee | Gout, ESRD, HT | 33,338 (95) | MSSA | MSU | No | N/A |

| 8 | M | 67 | Yes | 5 | Wrist | CKD3 | TNTC | MSSA | MSU | No | N/A |

| 9 | F | 65 | Yes | 5 | Knee | Cirrhosis, DM, HT | 42,129 (89) | MSSA | MSU | No | N/A |

| 10 | M | 23 | Yes | 7 | Polyarthritis | Lamellar ichthyosis | 55,550 (93) | MSSA | MSU | No | 379.8 |

| 11 | M | 50 | Yes | 14 | Knee | Gout, alcoholic cirrhosis | TNTC | MSSA | MSU | No | N/A |

| 12 | M | 51 | Yes | 30 | Knee | Gout, HT | 110,400 (94) | MSSA | MSU | No | N/A |

| 13* | M | 79 | Yes | 2 | Wrist Knee | OA knees | N/A | MSSA | Both | Yes | N/A |

| 14 | M | 66 | Yes | 30 | Knee | DM, cirrhosis, CVA, AF | 61,254 (97) | MRSA | Both | Yes | N/A |

| 15 | F | 61 | Yes | 1 | Knee | DM, HT, Old CVA | 186,840 (90) | Streptococcus dysgalactiae | CPPD | Yes | N/A |

| 16 | M | 55 | Yes | 2 | Knee | Gout | 41,878 (95) | Streptococcus dysgalactiae | MSU | No | N/A |

| 17 | M | 46 | Yes | 5 | Knee | Gout | 197,110 (90) | Streptococcus dysgalactiae | MSU | No | N/A |

| 18* | F | 80 | Yes | 2 | Polyarthritis | Old CVA | 171,830 (83) | Streptococcus dysgalactiae | MSU | No | N/A |

| 19* | M | 52 | Yes | 2 | Knee | Gout, DM, alcoholic cirrhosis | 75,330 (56) | Streptococcus dysgalactiae | MSU | Yes | N/A |

| 20* | M | 71 | Yes | 3 | Knee | Gout, CKD4, DM, HT | 43,015 (94) | Streptococcus dysgalactiae | MSU | No | N/A |

| 21* | M | 68 | Yes | 7 | Knee, Ankle | Gout, alcoholic cirrhosis | 14,483 (94) | Streptococcus dysgalactiae | MSU | No | N/A |

| 22 | M | 76 | Yes | 1 | Knee | Gout, CKD3, DM, HT, DLP | 85,826 (95) | Streptococcus agalactiae | CPPD | No | N/A |

| 23 | M | 74 | Yes | 3 | Shoulder | HT | N/A | Streptococcus agalactiae | MSU | No | N/A |

| 24 | M | 48 | Yes | 4 | Knee | Epilepsy | 158,705 (81) | Streptococcus agalactiae | MSU | No | 226.9 |

| 25 | M | 49 | Yes | 7 | Ankle | Gout, CKD2 | 131,030 (85) | Streptococcus agalactiae | MSU | Yes | N/A |

| 26 | M | 36 | Yes | 9 | Ankle | - | 120,500 (92) | Streptococcus agalactiae | MSU | No | N/A |

| 27 | F | 82 | Yes | 2 | Wrist, 1st MTP | Gout, CKD3, DM, HT | 65,420 (84) | Streptococcus pyogenes | MSU | No | 177 |

| 28 | M | 59 | Yes | 3 | Ankle | Gout, DM, HT, DLP | 39,530 (96) | Streptococcus pyogenes | Both | No | N/A |

| 29 | F | 73 | Yes | 30 | Knee, Ankle | HT, DLP | 66,980 (94) | Staphylococcus haemolyticus | Both | No | 100 |

| 30 | F | 82 | Yes | 7 | Knees | HT, OA knees | 59,382 (94) | Staphylococcus haemolyticus | Both | No | N/A |

| 31 | F | 69 | No | N/A | Knee | Gout, RA, HT, OA knees | N/A | Staphylococcus warneri | MSU | No | N/A |

| 32 | M | 70 | Yes | 10 | Knees | Gout, CKD3, DM, HT | 20,000 (79) | Staphylococcus hominis | Both | No | N/A |

| 33 | M | 84 | Yes | 1 | Wrist, Elbow | Gout, CKD3 | 101,200 (90) | Staphylococcus epidermidis | MSU | No | N/A |

| 34 | M | 74 | Yes | 1 | Knee, Ankle | RA, CKD3 | 47,050 (96) | CONS | MSU | No | N/A |

| 35 | M | 42 | Yes | 1 | Knee | Gout | 77,660 (98) | CONS | MSU | No | N/A |

| 36 | M | 56 | Yes | 1 | Knee | Gout, ESRD | 15,170 (76) | MRCONS | MSU | No | N/A |

| 37 | M | 85 | No | 4 | Knee | Gout, CKD3, BPH | 29,450 (93) | Enterococcus faecium | MSU | No | 282 |

| 38 | F | 83 | Yes | 5 | Knees, Ankles | Gout | 33,600 (90) | Lactococcus garvieae | MSU | No | N/A |

| 39 | M | 64 | Yes | N/A | Knee | Multiple myeloma, CKD3 | 31,873 (95) | Escherichia coli | MSU | No | N/A |

| 40 | M | 52 | Yes | 14 | Hip | MTB lymphadenitis | 12,095 (91) | Salmonella group B and C | MSU | No | N/A |

| 41 | F | 74 | Yes | 8 | Knee | Gout, CKD4, RA, HT | 61,702 (97) | Salmonella group D | MSU | No | 82.2 |

| 42 | M | 66 | Yes | 1 | Knee | ESRD, HT, DM | 17,363 (89) | Sphingomonas paucimobilis | MSU | No | N/A |

| 43 | M | 62 | Yes | 7 | Ankle | Gout, HT | 355,740 (80) | Burkholderia pseudomallei | MSU | Yes | N/A |

| 44 | F | 55 | Yes | 1 | Knee | - | 193,280 (90) | Acinetobacter baumannii | MSU | Yes | N/A |

| 45* | F | 82 | Yes | 3 | Knee, Wrist | CKD4, HT, Cirrhosis | 51,000 (71) | Acinetobacter baumannii | MSU | Yes | N/A |

*AF: Patient with dead. Atrial fibrillation, BPH: benign prostatic hyperplasia, CPPD: calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate deposition disease, CVA: cerebrovascular accident, CKD: chronic kidney disease, CONS: coagulase negative Staphylococcus, CRP: C-reactive protein, DM: diabetes mellitus, DLP: dyslipidemia, ESRD: end stage renal disease, F: female, HC: hemoculture, HT: hypertension, ITP: immune thrombocytopenia, M: male, MI: myocardial infarction, MRCONS: methicillin-resistant coagulase negative Staphylococci, MRSA: methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, MSSA: methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus, mg/L: milligrams per liter, MSU: monosodium urate crystal, MTB: Mycobacterium Tuberculosis, MTP: metatarsophalangeal joint, N/A: not available, OA: osteoarthritis, PMN: polymorphonuclear leukocyte, RA: rheumatoid arthritis, SD: standard deviation, SF: synovial fluid, TNTC: too numerous to count, WBC: white blood cell.

Clinical Presentations

Fever was observed in 95.6% of patients. Most patients presented with acute monoarthritis (66.7%), followed by acute oligoarthritis (31.1%), with acute polyarthritis being uncommon (2.2%). The knee was the most commonly affected joint (68.9%). The median (IQR) duration from joint pain onset to the diagnosis of either septic or crystal-induced arthritis was 3 (2–7) days.

Laboratory Findings

The median synovial WBC count (IQR) was 61,478 (33,600–131,030) cells/μL. The mean (± SD) blood WBC count was 16,046 ± 8702 cells/μL. Monosodium urate crystals were detected in 80% of cases, whereas CPP crystals were identified in 4.4% of cases. CRP results were available for only 17.8% of patients. For these patients, the mean (± SD) CRP level was 215 ± 96.7 mg/L, and no patient recorded a CRP level below 82.2 mg/L.

The predominant organism identified was Staphylococcus, found in 48.9% of cases. Within this group, methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) accounted for 28.9%. Streptococcus was identified in 31.1% of culture-positive patients. Among these, Streptococcus dysgalactiae accounted for 15.6%. Gram-negative bacilli were identified in 15.6% of culture-positive patients. Positive synovial Gram staining was observed in 35.6% of the culture-positive patients, whereas positive blood culture was observed in only 15.6% of patients.

Management and Outcomes

Surgical treatment was performed in 60% of cases. The mortality rate was 15.6%.

Discussion

Despite the rarity and limited research concerning concomitant septic and crystal-induced arthritis among patients with crystal-induced arthritis, our study identified a prevalence rate of 4%. Previous studies in the United States reported lower rates, ranging from 1.5%–1.8%,[11,16] whereas Australia documented a higher rate of 5.2%.[14]

The majority of patients were male (73.3%), with a mean age of 62.8 years. Gout was the most common underlying condition, present in 53.3% of patients. Fever was present in 95.6% of patients. The most common joint presentation was acute monoarthritis (66.7%), with the knee being the most frequently affected joint (68.9%). The median duration of arthritis was 3 days. The median synovial fluid WBC count was 61,478 cells/μL. The majority of patients (86.8%) had synovial WBC counts exceeding 20,000 cells/μL. The mean CRP level was 215 mg/L, and none of the patients had a CRP level < 82.2 mg/L. The most common crystals detected were monosodium urate crystals (80%). Gram-positive cocci were the most frequently isolated organisms and were identified in 84.4% of culture-positive patients. Among these cases, Staphylococcus was the most common (48.9%), and gram-negative bacilli were present in 15.6% of culture-positive patients. Among patients with positive cultures, synovial Gram staining was positive in 35.6%, while blood cultures were positive in only 15.6%.

We conducted a literature review and compared our results to those of previous studies. Owing to the rarity of concomitant septic and crystal-induced arthritis, our findings consisted mainly of case reports and four case series as noted in Table 3.[13, 14, 15,17]

Compare the data from literature review

| Country, publish year | Taiwan, 2003[13] | Taiwan, 2009[15] | Australia, 2012[14] | Spain, 2019[17] | Thailand, 2024 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year of study | 1987–2001 | 1998–2008 | 2004–2009 | 1985–2015 | 2015–2024 | |||||

| Primary objective | Assess clinical features and outcomes of concomitant gout and septic arthritis. | Assess characteristic features of patients with coexistence of gout and septic arthritis. | Identify frequency of coexistence of crystal and septic arthritis. To compare these with regard to SF microscopy, CRP, HC. | Assess the characteristics of concomitant septic and crystal-induced arthritis. | Study the prevalence and characteristics of patients with concomitant septic and crystal-induced arthritis. | |||||

| Prevalence of concomitant arthritis | N/A | N/A | 5.2% | N/A | 4% | |||||

| Number of patients | 30 | 14 | 22 | 25 | 45 | |||||

| Age, mean (SD)-years | 52.8 (12.5) | 63.7 (10.9) | 76 (N/A) | 67 (14) | 62.8 (14.4) | |||||

| Septic arthritis diagnosis | Positive bacterial culture in synovial fluid | Positive bacterial culture in synovial fluid | Positive bacterial culture in synovial fluid | -Positive culture in synovial fluid (22/25) -Positive HC but negative SF culture (3/25) | Positive bacterial culture in synovial fluid | |||||

| Crystal induced arthritis diagnosis | Seen intracellular crystal in synovial fluid or intraarticular tophi | Seen intracellular crystal in synovial fluid | Seen intracellular crystal in synovial fluid | Deposition of microcrystals | Seen intracellular crystal in synovial fluid | |||||

| Type of crystal MSU, % (n) | 100 (30) | 100 (14) | 41.9 (13) | 68 (17) | 80 (36) | |||||

| Calcium, % (n) | 0 | 0 | CPPD | 58.1 (19) | CPPD 20 (5) HA 12 (3) | CPPD 4.4 (2) | ||||

| Both, % (n) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 15.6 (7) | |||||

| Male sex, % (n) | 86.7 (26) | 92.9 (13) | 77.3 (17) | 68 (17) | 73.3 (33) | |||||

| Duration, mean (SD)-days | 6.5 | 6.5 (4.0) | N/A | 14 (13) | 6 (7.4) | |||||

| Fever, % (n) | 66.7 (20) | 71.4 (10) | N/A | 48 (12) | 95.6 (43) | |||||

| Number of joint, % (n) | Monoarthritis | 90 | Monoarthritis | 14.3 | N/A | Monoarthritis | 92 | Monoarthritis | 66.7 (30) | |

| Oligoarthritis | 10 | Oligoarthritis | 78.6 | Oligoarthritis | 8 | Oligoarthritis | 31.1 (14) | |||

| Polyarthritis | - | Polyarthritis | 7.1 | Polyarthritis | - | Polyarthritis | 2.2 (1) | |||

| Distribution of joint, % (n) | Knee | 80 | Ankle | 78.6 | N/A | Knee | 48 | Knee | 68.9 (31) | |

| Ankle | 20 | Knee | 57.1 | MTP | 12 | Ankle | 28.9 | |||

| Shoulder | 3.3 | Elbow | 21.4 | Hip | 12 | (13) | ||||

| Wrist | 3.3 | Ankle | 8 | Wrist | 15.6 (7) | |||||

| Shoulder | 8 | Elbow | 6.7 (3) | |||||||

| Hip 4.4 (2), shoulder 2.2 (1) | ||||||||||

| WBC, mean (SD)- cells/μL | 18,290 (11,059) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 16,046 (8,702) | |||||

| CRP, mean (SD) [range]-mg/L | N/A | N/A | 224 (N/A) | 137.16 (138.83) | 215 (96.7) [82.2–379.8] | |||||

| SF WBC, mean (SD) | 59,470 (55,330) | 44,102 (30,306) | N/A | 23,057 (22,903) | 99,535 (101,228) | |||||

| [range]- cells/μL | [3200–154,500] | [11,610–85,000] | [4000–75,000] | [12,095–463,220] | ||||||

| SF PMN, % | 95.7 | 93.3 | N/A | 85.9 | ||||||

| SF Bacterial culture | ||||||||||

| GPC, % (n) | 73.3 (22) | 85.7 (12) | N/A | 100 (17) | 84.4 (38) | |||||

| Staphylococcus, % (n) | 53.3 (16) | 71.4 (10) | 48 (12) | 48.9 (22) | ||||||

| MRSA, % (n) | 23.3 (7) | 7.1 (1) | 12 (3) | 2.2 (1) | ||||||

| GNB, % (n) | 30 (9) | 14.2 (2) | 0 | 15.6 (7) | ||||||

| Positive SF gram stain, % (n) | 56.3 (9/16) | 71.4 (10/14) | 54.5 (12/22) | N/A | 35.6 (16) | |||||

| Positive HC, % (n) | 36.7 (11/30) | 50 (7/14) | 43.8 (7/16) | N/A | 15.6 (7) | |||||

| Comorbidities, % (n) | DM | 16.7 | Gout | 92.2 | DM | 24 | N/A | Gout | 53.3 (24) | |

| Cirrhosis | 6.7 | CKD | 78.6 | CKD | 16 | HT | 48.9 (22) | |||

| Hemodialysis | 3.3 | DM | 21.4 | KT | 16 | CKD | 37.8 (17) | |||

| TKR | 6.7 | HT | 8 | DM | 22.2 (10) | |||||

| Cirrhosis | 13.3 (6) | |||||||||

| Surgical management, % | Debridement | 46.7 | Debridement | 35.7 | N/A | Debridement | 36 | Debridement | 60 (27) | |

| Amputation | 3.3 | Amputation | 7.1 | |||||||

| Dead, % (n) | 6.7 (2) | 28.6 (4) | N/A | 8 (2) | 15.6 (7) | |||||

AF: Atrial fibrillation, CPPD: calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate, CVA: cerebrovascular accident, CKD: chronic kidney disease, CRP: C-reactive protein, DM: diabetes mellitus, DLP: dyslipidemia, ESRD: end stage renal disease, HC: hemoculture, HA: hydroxyapatite, HT: hypertension, ITP: immune thrombocytopenia, KT: kidney transplantation, MTP: metatarsophalangeal joint, MTB: Mycobacterium Tuberculosis, mg/L: milligrams per liter, MRSA: methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, MSU: monosodium urate crystal, N/A: not available, OA: osteoarthritis, PMN: polymorphonuclear leukocyte, RA: rheumatoid arthritis, SD: standard deviation, SF: synovial fluid, TKR: total knee replacement, WBC: white blood cell.

Given the similarities in symptoms, such as acute monoarthritis or acute oligoarthritis with or without fever, and shared laboratory findings, such as elevated synovial fluid WBC counts and leukocytosis, diferentiating between septic arthritis and crystal-induced arthritis presents a significant challenge. This dificulty is further compounded in cases of concomitant septic arthritis and crystal-induced arthritis that occur in patients with crystal-induced arthritis. Even with the presence of crystals in synovial fluid, a diagnosis of concomitant septic arthritis and crystal-induced arthritis cannot be ruled out.[11,13, 14, 15, 16, 17] Delayed diagnosis and treatment of septic arthritis can result in joint damage and increased morbidity and mortality. According to our literature review, the mortality rate associated with concomitant septic and crystal-induced arthritis ranges between 6.7%–28.6%.[12, 13, 14, 15,17]

Several studies have aimed to differentiate concomitant septic and crystal-induced arthritis from crystal-induced arthritis. Gram staining demonstrates high specificity and positive predictive value (PPV) in the diagnosis of septic arthritis.[14] However, due to its low sensitivity, it produced a positive result in only 35.6% of the cases in our study. A synovial WBC count ≤ 10, 000 cells/μL and CRP level ≤ 100 mg/L were unlikely to indicate concomitant septic and crystal-induced arthritis, with negative predictive values (NPV) of 98.5% and 98.7%, respectively. In contrast, elevated synovial WBC counts > 10,000 cells/μL or increased CRP levels > 100 mg/L were suggestive of concomitant septic and crystal-induced arthritis, demonstrating a sensitivity of 86.4% and specificities of 48.3% and 54.6%, respectively.[14] Compared to our findings, synovial WBC counts < 12,000 cells/μL and CRP levels < 80 mg/L were indicative of a lower likelihood of concomitant septic and crystal-induced arthritis. Elevated synovial WBC count > 85,000 cells/μL strongly indicates concomitant septic and crystal-induced arthritis with a specificity of 100%, although with a low PPV of 12.0%.[16] This is consistent with our study, where 86.8% of patients had synovial WBC counts > 20,000 cells/μL, and 60.5% had synovial WBC > 50,000 cells/μL. Procalcitonin is a biological laboratory marker of bacterial infection that may be useful for diagnosing septic arthritis and acute osteomyelitis.[18] A recent diagnostic study demonstrated that a procalcitonin level of ≥ 1.36 μg/L is highly specific for distinguishing septic arthritis from gouty arthritis, with a sensitivity of 70.4%, specificity of 99.5%, and a PPV of 97.4%. Conversely, a procalcitonin level of < 0.4 μg/L unlikely to be septic arthritis, with a sensitivity of 96.3%, specificity of 67.8%, and a NPV of 98.5%.[19]

Practitioner Points: In medical practice, we would like to suggest that the use of basic investigation to rule out concomitant septic and crystal-induced arthritis is easier than diagnosing such conditions, if synovial WBC < 12,000 cells/μL and CRP < 80 mg/L, or procalcitonin level < 0.4 ng/μL, the chance of concomitant septic and crystal-induced arthritis is very low. In contrast, if the synovial fluid Gram stain is positive, it has high specificity and PPV for the diagnosis of concomitant septic and crystal-induced arthritis. However, in typical cases where excluding this diagnosis is challenging, such as when synovial WBC > 20,000 cells/μL with fever or WBC > 85,000 cells/μL or procalcitonin level ≥ 1.36 ng/μL, it could be best to initially manage the condition as septic arthritis until further evidence allows a definitive exclusion of concomitant septic arthritis.

The strength of our study is that it encompasses the largest concomitant septic and crystal-induced arthritis population ever studied to date. One limitation of this study is that it was retrospective; it may lack some data, and the observed distribution of afected joints might be biased towards those more easily accessible for aspiration by physicians.

Conclusions

The prevalence of concomitant septic and crystal-induced arthritis was 4% among patients with crystal-induced arthritis. Most patients presented with acute monoarthritis, fever, and elevated WBC counts in synovial fluid. The chance of concomitant septic and crystal-induced arthritis is very low in cases with synovial WBC counts < 12,000 cells/μL.

Funding statement: This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

We thank the laboratory staff and the medical electronic database team for their crucial support in successfully completing this research.

-

Author contributions

K. D.; designed the study, developed the proposal, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript, P. S.; contributed to designing the study project, developing the proposal, contacting the Institutional Review Board, collecting data, and analyzing the initial data.; K.D., P.S., P.T., Y.S., and T. P. writing—review and editing.; all authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

-

Ethical approval

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Khon Kaen Hospital (protocol code KEXP65061 and date of approval 12 October 2022).

-

Informed consent

The inform consent is waved due to retrospective study.

-

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

-

Use of large language models, AI and machine learning tools

None declared.

-

Data availability statement

Not applicable.

-

Additional disclosure

This study was previously presented as a poster presentation at the 25th Asia-Pacific League of Associations for Rheumatology (APLAR) Congress, held from December 7-11, 2023, in Thailand. The current manuscript presents an updated version of the study with minor modifications to the title and reanalysis of some data. The original poster presentation can be accessed at: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1756-185X.14982

References

[1] Chen-Xu M, Yokose C, Rai SK, et al. Contemporary Prevalence of Gout and Hyperuricemia in the United States and Decadal Trends: The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2007–2016. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71:991–999.10.1002/art.40807Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[2] Dehlin M, Jacobsson L, Roddy E. Global epidemiology of gout: prevalence, incidence, treatment patterns and risk factors. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2020;16:380–390.10.1038/s41584-020-0441-1Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Neogi T, Jansen TL, Dalbeth N, et al. 2015 Gout classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:1789–1798.10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-208237Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[4] Zhang W, Doherty M, Bardin T, et al. European League Against Rheumatism recommendations for calcium pyrophosphate deposition. Part I: terminology and diagnosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:563–570.10.1136/ard.2010.139105Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Neame RL, Carr AJ, Muir K, et al. UK community prevalence of knee chondrocalcinosis: evidence that correlation with osteoarthritis is through a shared association with osteophyte. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:513–518.10.1136/ard.62.6.513Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[6] Weston VC, Jones AC, Bradbury N, et al. Clinical features and outcome of septic arthritis in a single UK Health District 1982–1991. Ann Rheum Dis. 1999;58:214–219.10.1136/ard.58.4.214Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] Margaretten ME, Kohlwes J, Moore D, et al. Does this adult patient have septic arthritis? JAMA. 2007;297:1478–1488.10.1001/jama.297.13.1478Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Jinno S, Sulis CA, Dubreuil MD. Causative Pathogens, Antibiotic Susceptibility, and Characteristics of Patients with Bacterial Septic Arthritis over Time. J Rheumatol. 2018;45:725–726.10.3899/jrheum.171115Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Landewé RB, Günther KP, Lukas C, et al. EULAR/EFORT recommendations for the diagnosis and initial management of patients with acute or recent onset swelling of the knee. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:12–19.10.1136/ard.2008.104406Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Mathew AJ, Ravindran V. Infections and arthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2014;28:935-959.10.1016/j.berh.2015.04.009Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Shah K, Spear J, Nathanson LA, et al. Does the presence of crystal arthritis rule out septic arthritis? J Emerg Med. 2007;32:23–26.10.1016/j.jemermed.2006.07.019Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Cho H, Burke L, Lee M. Septic Arthritis. Hosp Med Clin. 2014;3:494–503.10.1016/j.ehmc.2014.06.009Search in Google Scholar

[13] Yu KH, Luo SF, Liou LB, et al. Concomitant septic and gouty arthritis--an analysis of 30 cases. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2003;42:1062–1066.10.1093/rheumatology/keg297Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Papanicolas LE, Hakendorf P, Gordon DL. Concomitant septic arthritis in crystal monoarthritis. J Rheumatol. 2012;39:157–160.10.3899/jrheum.110368Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] C-T Weng, M-F Liu, L-H Lin, et al. Rare coexistence of gouty and septic arthritis: a report of 14 cases. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2009;27:902–906.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Luo TD, Jarvis DL, Yancey HB, et al. Synovial Cell Count Poorly Predicts Septic Arthritis in the Presence of Crystalline Arthropathy. J Bone Jt Infect. 2020;5:118–124.10.7150/jbji.44815Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] Prior-Español Á, García-Mira Y, Mínguez S, et al. Coexistence of septic and crystal-induced arthritis: A diagnostic challenge. A report of 25 cases. Reumatol Clin. 2019;15:e81-e85.10.1016/j.reumae.2017.12.004Search in Google Scholar

[18] Maharajan K, Patro DK, Menon J, et al. Serum Procalcitonin is a sensitive and specific marker in the diagnosis of septic arthritis and acute osteomyelitis. J Orthop Surg Res. 2013;8:19.10.1186/1749-799X-8-19Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[19] Guillén-Astete CA, García-García V, Vazquez-Díaz M. Procalcitonin Serum Level Is a Specific Marker to Distinguish Septic Arthritis of the Knee in Patients With a Previous Diagnosis of Gout. J Clin Rheumatol. 2021;27:e575–e579.10.1097/RHU.0000000000001215Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2025 Kittikorn Duangkum, Pattawee Saengmongkonpipat, Pimchanok Tantiwong, Yada Siriphannon, Thida Phungtaharn, published by De Gruyter on behalf of NCRC-DID

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Editorial

- How will we treat systemic lupus erythematosus in the next 5 years?

- Guideline

- 2025 Chinese guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus

- Review

- Proceedings of cell-free noncoding RNA biomarker studies in liquid biopsy

- Original Article

- Investigating the role of tripartite motif containing-21 and interleukin-6 in pro-Inflammatory symptom-associated heterogeneity within primary Sjögren’s syndrome

- Reevaluating risk assessment in connective tissue disease-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension: The prognostic superiority of stroke volume index

- Prevalence and characteristics of concomitant septic and crystal-induced arthritis: A hospital database and literature review

- Association of HLA-B and HLA-DR gene polymorphisms with rheumatoid arthritis: A cross-sectional study in Yunnan Chinese Han population

- Letter to the Editor

- Association of ficolin single nucleotide polymorphism with systemic lupus erythematosus in the Chinese Han Population

- Images

- The storm inside: Abdominal and urinary complications in lupus

Articles in the same Issue

- Editorial

- How will we treat systemic lupus erythematosus in the next 5 years?

- Guideline

- 2025 Chinese guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus

- Review

- Proceedings of cell-free noncoding RNA biomarker studies in liquid biopsy

- Original Article

- Investigating the role of tripartite motif containing-21 and interleukin-6 in pro-Inflammatory symptom-associated heterogeneity within primary Sjögren’s syndrome

- Reevaluating risk assessment in connective tissue disease-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension: The prognostic superiority of stroke volume index

- Prevalence and characteristics of concomitant septic and crystal-induced arthritis: A hospital database and literature review

- Association of HLA-B and HLA-DR gene polymorphisms with rheumatoid arthritis: A cross-sectional study in Yunnan Chinese Han population

- Letter to the Editor

- Association of ficolin single nucleotide polymorphism with systemic lupus erythematosus in the Chinese Han Population

- Images

- The storm inside: Abdominal and urinary complications in lupus