Abstract

The water matrix plays a complex and significant role in photocatalytic degradation by influencing several factors, including dissolved anions and cations, the presence of natural organic matter, dissolved oxygen, suspended particles, turbidity, pH, and temperature. Optimizing photocatalytic processes for practical water treatment applications necessitates understanding these relationships. The efficiency and efficacy of photocatalytic water treatment systems in degrading organic contaminants can be enhanced by carefully considering and manipulating the water matrix. Based on literature published between 2000 and 2024, this review aims to comprehend the effects of contaminants and water quality on the photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants. Researchers have employed various water matrices and reaction conditions to understand the interactions and impacts of different water matrix pollutants on photodegradation. The literature analysis revealed that when chloride and sulfate ions interact with reactive oxygen species and photocatalysts, their effects are predominantly inhibitory, thereby reducing the photocatalytic activity of the catalysts. Conversely, nitrate ions can exhibit an inhibitory effect under certain conditions by scavenging hydroxyl radicals while promoting photodegradation in other scenarios by generating more reactive oxygen species. The degree of inhibition varies according to the concentration of these factors.

1 Introduction

One revolutionary method for addressing the increasing problems associated with water pollution is the photocatalytic degradation of organic contaminants. Its efficiency in degrading various pollutants and its environmental and economic advantages make it a key technology in contemporary water treatment and environmental preservation initiatives. The motivation to develop a review on the effect of the water matrix on photodegradation arose during the submission of a research paper in which reviewers inquired about the effects of dissolved ions on photodegradation. Since then, it was planned to produce a comprehensive review covering dissolved ions and all other factors affecting the photodegradation process. A literature search revealed only a few articles discussing the matrix effect. The available literature primarily focused on specific components of the water matrix or specific pollutants.

Water pollution is frequently caused by organic pollutants, which include industrial chemicals, pesticides, dyes, and medications. These pollutants tend to persist in the environment. Photocatalysis can break down these complex contaminants into less dangerous or benign chemicals. A significant number of organic pollutants are harmful, carcinogenic, or mutagenic. Photocatalysis can effectively decompose these toxic substances into innocuous byproducts, such as carbon dioxide, water, and inorganic ions, thereby mitigating their negative effects on ecosystems. Photocatalysis can target a wide range of newly discovered pollutants that traditional water treatment techniques may not be able to address pollution from new and unknown sources. Photocatalytic degradation helps ensure drinking water safety by removing contaminants from water sources and reducing health risks associated with exposure to organic pollutants. Numerous organic contaminants contribute to the spread of diseases in aquatic environments. By indirectly slowing the spread of waterborne illnesses, photocatalytic activities can aid in controlling these pollutants. Photocatalysis can be more economical than older techniques for treating low concentrations of contaminants, as it often requires fewer chemicals and less energy. Additionally, photocatalytic systems typically require less maintenance and operation, making their long-term installation in water treatment plants more appealing. Many photocatalytic reactions are powered by solar energy, making them environmentally friendly and sustainable. Utilizing a renewable energy source aligns with international initiatives to reduce dependency on fossil fuels.

The components of the water matrix include inorganic cations and anions, dissolved and suspended organic matter, dissolved oxygen, and the breakdown products of organic contaminants. Water conditions include pH, temperature, and the type of light irradiation. Less reactive chlorine species are formed when hydroxyl radicals and chloride ions interact (Liou and Dodd 2021). When anions and reactive oxygen species (ROS) interact, some anions can produce reactive intermediates that may contribute to further pollutant breakdown or decrease overall efficiency. Br-ions can also form bromine radicals (Br·) and other reactive bromine species. Phosphate ions can adsorb onto TiO2 surfaces, obstructing active sites and hindering the breakdown of phenolic compounds. Anions can react with ROS, such as hydroxyl radicals (·OH), reducing their ability to attack and degrade organic contaminants. Cations can alter the surface charge of photocatalysts through ionic interactions or surface complex formation. This modification may affect the surface charge of photocatalysts, impacting both the adsorption behavior of the cations and the organic contaminants.

2 Photodegradation pathways

Water matrix composition is key in determining which photodegradation pathways will dominate when a contaminant is exposed to light. The possible pathways are as follows:

2.1 Direct photolysis

The contaminant itself absorbs light and breaks down. Direct photolysis is more effective in clear water with low dissolved organic matter (DOM) and few interfering substances because the light reaches the contaminant without being absorbed or scattered by other materials.

2.2 Indirect photolysis

Light is absorbed by other substances in the water (like nitrate, nitrite, or DOM), which then generate reactive species (such as hydroxyl radicals ·OH, singlet oxygen, or triplet excited states). These reactive species attack and degrade the pollutant. Under UV light irradiation, the nitrate/nitrite ions can produce hydroxyl radicals that oxidize pollutants. DOM can absorb light and transfer energy to pollutants or oxygen, generating ROS that drive degradation. Conversely, DOM can also absorb light that would otherwise activate the pollutant, reducing direct photolysis. The net effect depends on balancing DOM’s photosensitizing ability and its light-screening effect.

2.3 Photo-Fenton and metal-catalyzed pathways

In waters with significant iron or other transition metals, light can drive reactions (like the photo-Fenton reaction) where these metals, along with hydrogen peroxide (which might be naturally present or added), generate powerful oxidizing radicals (·OH) that break down pollutants. Water matrices rich in iron or other catalytic metals favor these pathways. The pH of the water is also critical here, as it affects metal speciation and the overall reaction efficiency.

2.4 Impact of other factors

Water’s acidity or alkalinity can change the chemical form of both the pollutant and the reactive species, influencing which photodegradation reactions can occur. Particles in water can scatter or absorb light, reducing the effective dose of light that reaches the pollutant and altering the photodegradation pathways. In clear water with minimal interfering substances, direct photolysis is more likely. In waters with significant amounts of nitrate or DOM, indirect photolysis dominates through the formation of reactive intermediates. In water matrices with high iron content (or other catalytic metals) and under appropriate pH conditions, photo-Fenton or metal-catalyzed pathways become significant. This interplay means that the overall photodegradation mechanism in any given water body will depend on its specific chemical composition and physical characteristics.

There are several water matrix constituents and characteristics that impact photocatalytic activity. These include inorganic anions and cations, turbidity, naturally occurring organic materials, pH, irradiation light type and intensity, temperature, and dissolved oxygen as shown in Figure 1. Figure 2 illustrates some factors affecting photodegradation and their relative effects. Researchers’ findings regarding how certain water contents affect the photocatalytic breakdown of organic pollutants are compiled in Table 1.

Illustration showing the water matric constituents and conditions that affect the degradation activity of the photocatalysts.

Illustration of some factors that affect photodegradation and their relative effects (Rocha et al. 2024). Reproduced with permission from Elsevier.

Effects of anions, cations, and organic matter in the water matrix on the photodegradation process.

| Reaction | Effect on the photodegradation |

|---|---|

| Br− + ·OH → Br· + OH− | Br− decreased the degradation of organic dyes by forming bromine radicals that were less effective in degrading pollutants |

| Cl− + ·OH → Cl· + OH− | Cl− inhibited the photocatalytic degradation of phenol and bisphenol A by forming less reactive chlorine species |

| HCO3− + ·OH → CO3·− + H2O | HCO3− reduced the degradation rate of pesticides by forming less reactive carbonate radicals |

| NO3− + hν → NO2· + O· | NO3− enhanced degradation in some systems by generating additional ROS but inhibited it in others by scavenging hydroxyl radicals |

| SO42− + h+ → SO4·− | SO42− showed a slight enhancement of degradation for certain pollutants due to sulfate radical generation |

| Ca2+ + pollutant → Ca-pollutant complex (insoluble) | Ca2+ inhibited the phenol degradation by forming calcium phenoxide, reducing active sites on the photocatalyst |

| Mg2+ + OH− → Mg(OH)2 (precipitate) | Mg2+ reduced the degradation efficiency of dyes by forming magnesium hydroxide on the photocatalyst surface |

| Al3+ + pollutant → Al-pollutant complex (strong interaction) | Al3+ significantly inhibited the degradation of organic dyes by forming strong complexes and altering the photocatalyst’s surface properties |

| Humic substance + ·OH → stable product | Humic acids reduced the degradation efficiency of organic dyes by competing for adsorption sites and scavenging ROS |

| Fulvic acid + ·OH → fulvic acid-·OH complex | Fulvic acids reduce the degradation of pesticides by absorbing UV light and scavenging ROS |

Gamelas et al. (2024) evaluated the photocatalytic efficacy of non-immobilized and immobilized porphyrins in the photodegradation of organic contaminants for wastewater treatment applications. This paper describes significant advances in the photocatalytic oxidation of water pollutants using simple porphyrin derivatives as well as porphyrins linked to various organic or inorganic materials, including polymers, fibers, carbon nanostructures, ZnO, SiO2, and TiO2 (or combinations of these supports), under UV, visible, and/or solar light irradiation. The inclusion of different metals in the porphyrin core resulted in varying photocatalytic activity, with Cu(II) porphyrin derivatives exhibiting the highest degradation rates. Furthermore, by sensitizing TiO2 or SiO2 supports with porphyrins, photocatalytic activity was significantly increased due to a decrease in the material’s band gap and absorption of visible light. This sensitization can occur via covalent or non-covalent interactions. It is vital to note that the photocatalytic mechanism is based on porphyrin excitation, followed by electron transfer to the support’s conduction band. Photogenerated holes and excited electrons can react with O2 or H2O to produce ROS that degrade pollutants. In some circumstances, adding H2O2 is required to achieve high levels of pollutant degradation. The light source (UV, visible, or solar light) is also significant. When solar/white light is employed, the support can be activated alongside the porphyrin, but UV light only excites the porphyrin moiety somewhat or not at all. Solar light is a significant advantage in photocatalysis because it reduces costs while utilizing the entire solar spectrum. It is also worth noting that almost all the photocatalysts covered here can be reused without substantial activity loss. In some cases, the photocatalyst is specific to a particular pollutant. While the photocatalytic studies in this review appear promising, there is a notable lack of research on identifying degradation products.

Deba et al. 2022 investigated the photocatalytic destruction of four micropollutants namely diclofenac (DCF), iopamidol (INN), methylene blue (MB), and metoprolol (MTP), using a photocatalytic ceramic membrane. The photodegradation studies were conducted on multiple water matrices by varying the feed composition of micropollutants (MPs) in the mixture, adding different amounts of inorganic compounds (NaHCO3 and NaCl), and using tap water. A micropollutant mixture in tap water at environmentally relevant feed concentrations (1–6 μg/L) resulted in maximum degradation of 97 % for DCF and MTP, 85 % for INN, and 86 % for MB in an MPs mixture [1–3 mg/L] with 100 mg/L of NaCl. Adding anions, such as bicarbonate, commonly reported as a degradation inhibitor, improved the degradation efficiency of positively charged MPs, highlighting the importance of surface charge interactions between the MP and the photocatalytic surface. The presence of chloride also had a favorable effect on MP degradation, more so at low concentrations than at high ones. Chloride ions can scavenge photogenerated holes, preventing electron–hole recombination; however, at high chloride concentrations, the number of available hydroxyl radicals decreases proportionally to the number of available holes. The results of mixes at environmentally relevant concentrations were equally surprising, demonstrating better degradation of MPs in tap water, with degradation rates of 97 % for DCF, 85 % for INN, and 97 % for MTP.

Petala et al. (2021) conducted a study of published data on the effect of water matrix on pharmaceutical photocatalytic degradation. Data collected under realistic settings are thought to be useful in guiding future photocatalytic technology development, bridging the gap between basic science and industry. The efficiency of photocatalysis appears to be significantly affected by (i) the nature of the materials and, consequently, the different ROS and reaction mechanisms, (ii) the nature and concentration of pharmaceuticals, and (iii) the organic and inorganic contents, making the extrapolation of ultrapure water (UPW) results into real effluents hazardous and unrealistic. Based on the evidence presented thus far, the method is most likely to be a green integrated solution for tertiary wastewater treatment, including disinfection, micropollutant destruction, and organic loading reduction in the context of wastewater reuse. It is, therefore, critical that future studies proceed with a comprehensive evaluation of process performance, including, in addition to the removal of micropollutants, microorganisms, organic matter, and color, as well as the change in overall toxicity from by-products of both pharmaceuticals and water matrices.

3 Influence of water matrix ingredients affecting the photodegradation

This review presents the effects of contaminants found in water, wastewater, tap water, and other types of water, as well as the properties of water, such as pH, turbidity, and temperature, on photocatalysis and photolysis. These contaminants include various anions and cations, natural organic matter, suspended particles/turbidity, and dissolved oxygen. The pH and temperature of the solutions are among the conditions that affect the photodegradation process. The type and intensity of radiation also have a marked effect on the photodegradation process. These elements are discussed in more detail in the following section.

3.1 Influence of inorganic anions (Cl−, NO3−, SO42−, PO43−, HCO3−, CO32−, Br−, F−)

The ions present in water significantly impact the photocatalytic breakdown of organic pollutants. Ions such as chloride, nitrate, sulfate, phosphate, bicarbonate, and bromide interact differently with ROS and photocatalysts. Their effects can be either promotive, by creating more reactive species, or inhibitory, by competing for active sites and scavenging ROS. The type of anions, their concentrations, and the specific photocatalytic system all affect the overall effect. Wastewater contains a variety of anions, including bicarbonate (HCO3−), carbonate (CO32−), phosphate (PO43−), nitrate (NO3−), sulfate (SO42−), and bromide (Br−). Wastewater may also contain less common anions, like fluoride (F−). These anions can significantly influence the photocatalytic degradation of organic contaminants through their interactions with photocatalysts and ROS. Depending on the composition and concentration of the anions, these interactions can either accelerate or slow down the degradation process. By adsorbing onto the active sites of photocatalysts, anions can reduce the surface area available for degradation by competing with organic contaminants. Less reactive species, such as hypochlorous acid (HOCl) and chlorine radicals (Cl·), can be formed when Cl− reacts with hydroxyl radicals. The activity of the catalyst can be altered by Cl− forming complexes with photocatalysts or other elements in the reaction mixture (Alegre et al. 2000). Typically, the production of less reactive species leads to inhibition. As shown in the equation below, Cl− ions prevented the photocatalytic degradation of phenol and bisphenol A by producing less reactive chlorine species: OH + Cl− → Cl· + OH−. A summary of the results of some studies showing the effects of water matrix contents on the photocatalytic degradation of pharmaceutical pollutants present in different water types is shown in Table 2.

Summarized results of some studies showing the effects of water matrix contents on the photocatalytic degradation of pharmaceutical pollutants in different water types.

| Catalysts | Target pollutants | Radiation and water type | Contaminants | Effects | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ag2S/BiVO4@a-Al2O3 | MNZ (10 mg/L) | Visible; TW | Cl−, SO42−, HCO3−, Ca2+, Mg2+ | Inhibiting effects: SO42− | Fakhravar et al. (2020) |

| Ag3PO4/NP-CQDs/rGH | TC (10 mg/L) | Visible; TW, | Cl−, SO42− | Inhibiting effect: Cl−, SO42− | Chen et al. (2020) |

| CNT-TiO2 | Carbamazepine (10 mg/L) | UV, solar; WW, RW | NOM | Inhibiting effect: NOM | Awfa et al. (2020) |

| Cu3P/BiVO4 | SMX (0.5 mg/L) | Solar; WW, BW | Cl−, HCO3−, HA | Inhibiting effects: WW, HA, Cl−, promoting effects: ВW, HCO3− | Ioannidi et al. (2020) |

| Crystalline-C3N4 | NPX (20 mg/L) | Visible; TW, RW, seawater, WW | Cl−, SO42− | Zero effect: Cl−, SO42− | Zebiri et al. (2024) |

| CeO2/I, K-co-doped C3N4 | Acetaminophen (10 mg/L) | Visible; TW | Cl−, SO42−, PO43−, NO3− | Inhibiting effect: Cl_, SO42− | Paragas et al. (2021) |

| g-C3N4/NiO/ZnO/Fe3O4 | Esomeprazole (30 mg/L) | Visible; BW, RW, TW | Cl−, SO42− | Inhibiting effect: Cl−, SO42− | Raha and Ahmaruzzaman (2020) |

| Carbon dots/g-C3N4 | NPX (10 mg/L) | Visible; TW, RW, WWTP | Cl−, SO42− | Zero effect: Cl−, SO42− | Wu et al. (2020) |

| Inverse opal (IO) | LVX, NOR (10 mg/L) | Visible; UW SHW | Cl−, SO42− | Inhibiting effect: Cl−, SO42− | Lei et al. (2020) |

| S@C3N4/B@C3N4 | CMP (10 mg/L) | Visible, solar; DW, TW | Cl−, NO3−, Na+, Ca2+ | Zero effect: Na+; inhibiting effect: Cl−; promoting effect: NO3− | Kumar et al. (2020) |

-

BW, bottle water; DW, drinking water; NOM, natural organic matter; RW, raw water; TW, tap water; UPW, ultrapure water; WW, wastewater.

Table 3 summarizes the findings of several studies investigating the impact of water matrix components on the photocatalytic degradation of organic dye contaminants in tap water. Evaluating the effect of mineral ions in TW on the photodegradation of organic contaminants is critical for the process’s practical application. TW has a low concentration of inorganic salts and a pH of 7–8, which can promote the production of ·OH radicals. The pH range and inorganic ions present in TW can either increase or decrease the photodegradation rate. Similarly, the presence of inorganic and metal ions in TW can reduce the photodegradation rate by competing for photocatalyst active sites and lowering photocatalytic activity. Saleh and Taufik (2019) reported the photodegradation of MB using an AuFe3O4/graphene composite in the presence of several salts, namely NaCl, Na2SO4, NaH2PO4, NaNO3, and Na2CO3. They concluded that CO32−, H2PO4−, NO3−, Cl−, and SO42− anions had an inhibitory effect on the degradation of MB.

Summarized results of some studies showing the effects of water matrix contents on the photocatalytic degradation of organic dye pollutants present in tap water.

| Catalysts | Target pollutants | Contaminants | Effects | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ag/Mn3O4 and Ag/Mn3O4/graphene with persulfate | MB | H2PO4−, CO32−, SO42−, Cl−, NO3− | All ions have negative effects on the order H2PO4− > CO32− > SO42− > Cl− > NO3− |

Rizal et al. (2021) |

| AuFe3O4/graphene composite | MB | NaCl, Na2SO4, NaH2PO4, NaNO3, Na2CO3 | CO32−, H2PO4−, NO3−, Cl−, SO42− had negative effect, Na + negligible effect |

Saleh and Taufik (2019) |

| CuO–Cu2O | MB and MO | NO3−, Cl−, SO42− | Cl− had a positive effect on MB, SO42− negative effect on MB, Cl− on MO | Tavakoli et al. (2022) |

| NiS/CuS–CdS Composites | MB and MO | NaCl, K3PO4, Na2CO3 | K3PO4 positive effect on MO, but a negative effect on MB; NaCl and Na2CO3 negative effect for MB and MO | Zheng et al. (2020) |

| ZnFe2O4 | MB | CO32−, NO3−, Cl−, SO42− | All ions had negative effect | Gupta et al. (2020) |

| ZnO nanorods | MB, Acid red, Remazol red, RhB | PO43−, Cl−, SO42−, NO3− | All ions had negative effects on the order PO43− > Cl− > SO42− > NO3− |

Mohammed et al. (2020) |

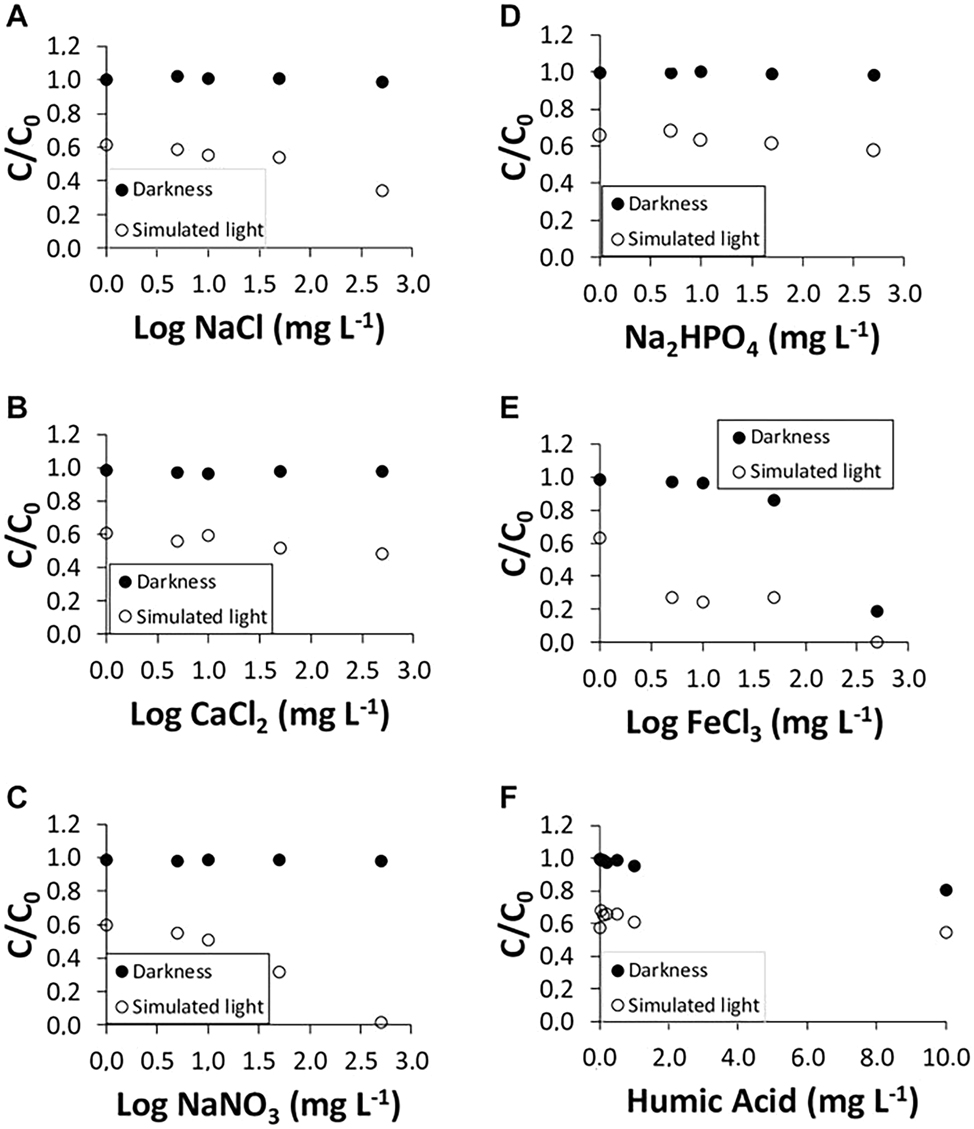

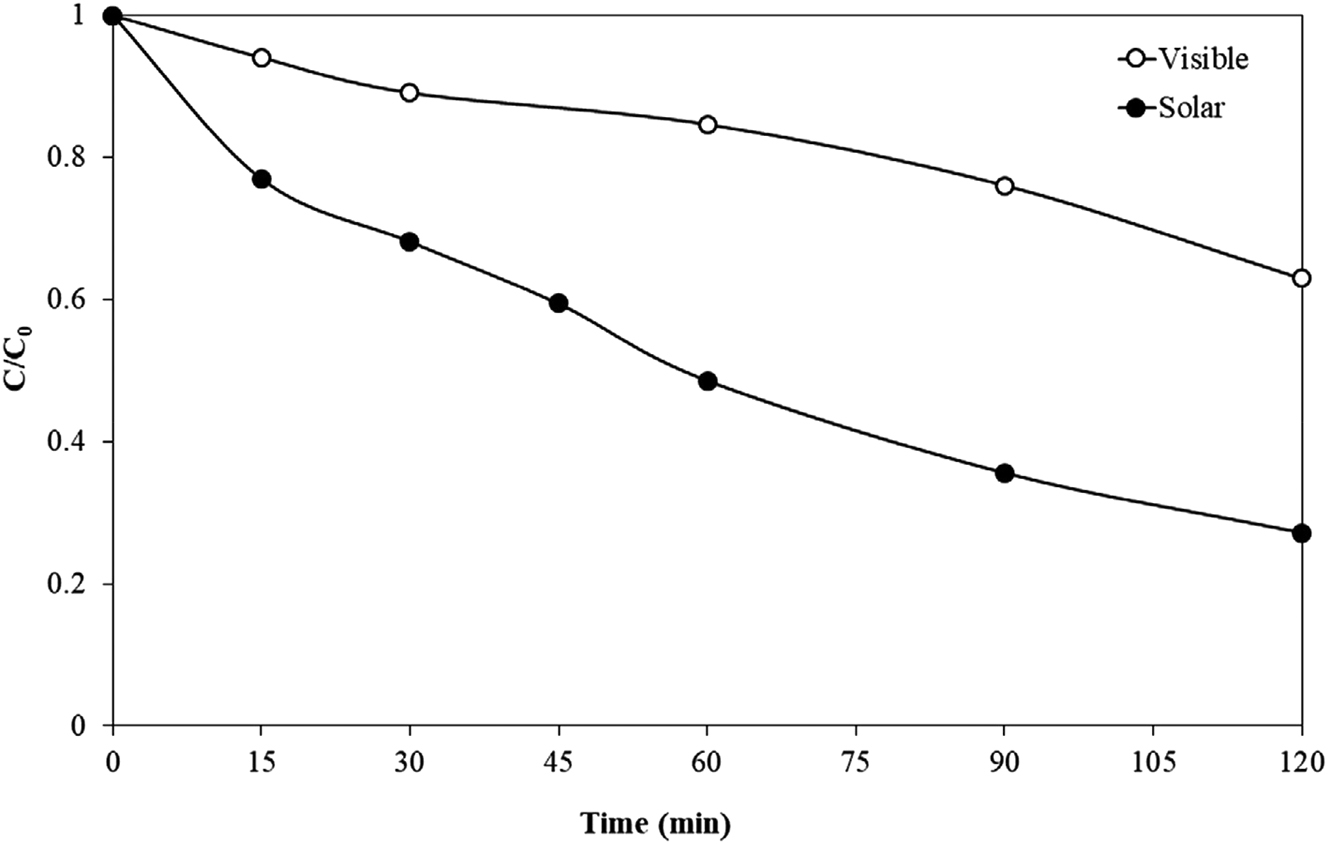

The efficient breakdown of AMX in the presence of humic acids and other inorganic salts under simulated sunlight was documented by Lucía et al. (Rodríguez-López et al. 2022). Under simulated sunlight and in the absence of light, AMX exhibited complete degradation in the presence of 500 mg/L of FeCl3. Because AMX adsorbs onto humic acids, the presence of humic acids may have somewhat accelerated AMX’s degradation in both the dark and under simulated sunlight. Rocha et al. (2024) evaluated the effect of pH, salinity, and the presence of humic substances or ROS scavengers on the photodegradation of AMX under simulated solar radiation. The photodegradation of AMX was observed to be faster at higher pH levels of 8 and 9. Conversely, photolysis was slower at high NaCl salinity. It was concluded that the main pathway for AMX photodegradation in phosphate buffer solution (PBS) is indirect photolysis via ·OH. Freshwater and brackish water were also studied to evaluate matrix effects on photodegradation, and they were found to be significantly faster than in PBS. Figure 3 shows the breakdown of AMX in the presence of humic acids and inorganic salts, both in the dark and under artificial sunlight. NaCl, Na2HPO4, and CaCl2 did not affect AMX degradation in the dark; however, when 500 mg/L of FeCl3 and NaNO3 were used to simulate sunlight exposure, AMX degradation reached 100 %.

AMX degradation under simulated sunlight and in the dark using inorganic salts: (A) NaCl; (B) CaCl2; (C) NaNO3; (D) Na2HPO4; (E) FeCl3; and (F) humic acids (Rodríguez-López et al. 2022).

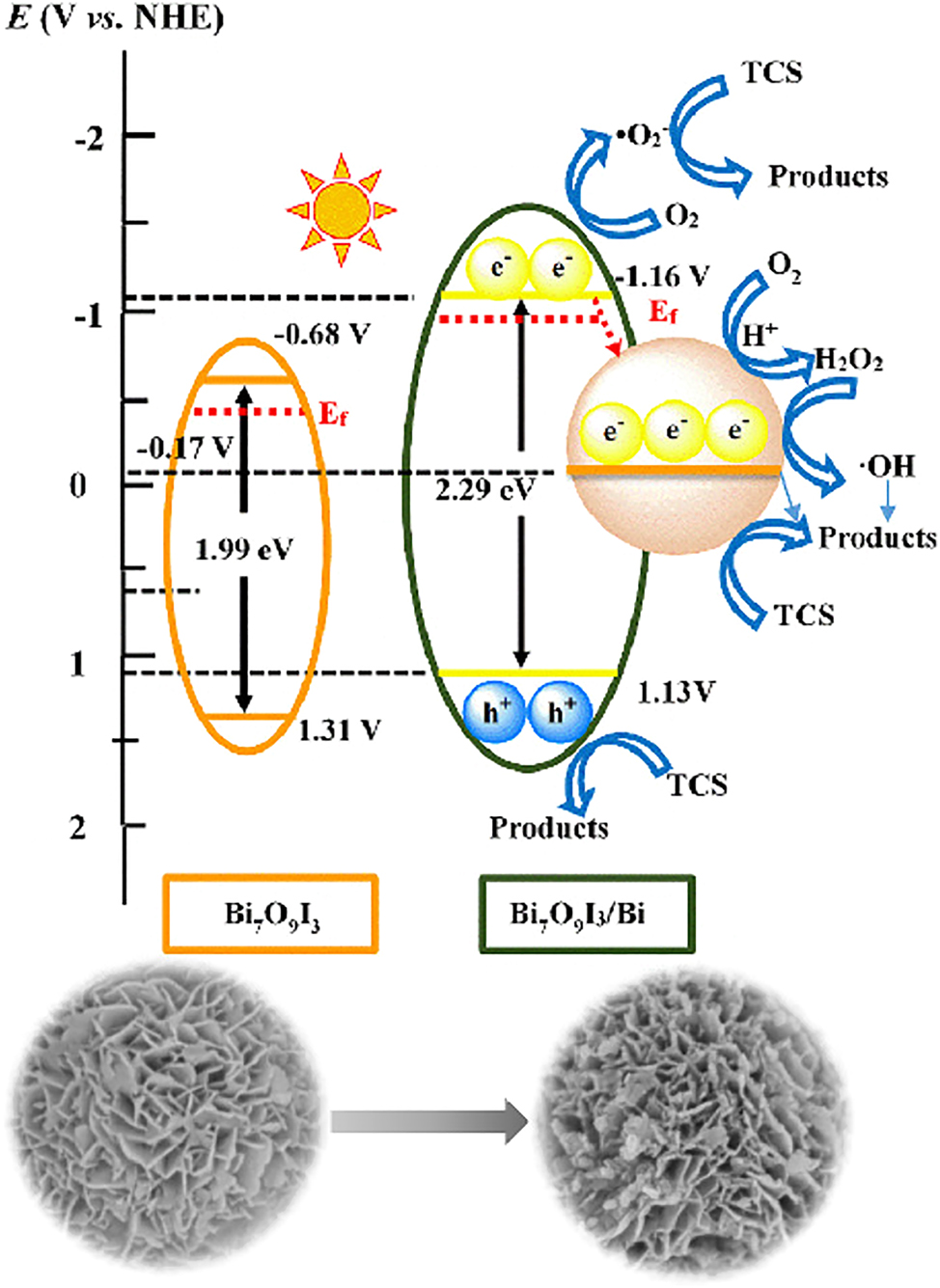

Chang et al. (2021) studied the impacts of inorganic anion and cation addition on the photocatalytic degradation of triclosan catalyzed by heterostructured Bi7O9I3/Bi. They observed that the presence of NO3−, SO42−, and Cl− anions hindered the photodegradation of triclosan, while HCO3−, Ca2+, and Mg2+ cations inhibited or promoted it depending on their concentrations. Figure 4 shows the proposed mechanism for separating and transferring photo-generated charge carriers in the Bi7O9I3/Bi nanocomposites.

Proposed mechanism for separating and transferring photogenerated charge carriers in the Bi7O9I3/Bi nanocomposites (Chang et al. 2021). Reproduced with permission from Elsevier.

When anions Cl−, SO42−, PO43−, and NO3− were added to various synthetic water matrices in UPW, Paragas et al. (2021) observed that the rates of acetaminophen degradation were reduced. TiO2 was used by Delarmelina et al. (2023) to study the impact of chlorides on the photocatalytic degradation of phenol. It was determined that solubilized chlorides reduced photodegradation activity and the production of hydroxyl radicals when employing the TiO2 photocatalyst. A notable decrease in the rate of phenol conversion was noted when anatase TiO2 was used. Conversely, under identical reaction conditions, the presence of solubilized chlorides led to an increase in rutile TiO2 activity. Anions such as phosphate, sulfate, nitrate, carbonate, and chloride are common in water, according to Wang and Wang (2021). They produce chlorine, carbonate, nitrate, phosphate, and sulfate radicals when they react with hydroxyl and sulfate radicals generated during advanced oxidation processes (AOPs). These radicals significantly impact the breakdown of organic contaminants. Most researchers agree that the primary factor affecting AOP performance is the quenching effect of inorganic anions on reactive species generated in AOPs. However, not all outcomes can be explained by this cause. Furthermore, the majority of research conducted thus far has only examined how inorganic anions affect the removal efficiency of specific organic contaminants from the environment. It is essential to thoroughly assess the impact of inorganic anions on AOPs to understand how these anions influence AOP performance. This review paper provides a systematic summary and review of the impact of inorganic anions (e.g., chloride, carbonate, phosphate, sulfate, and nitrate) on the activity of AOPs, including the transformation of reactive species, stability of oxidants, catalytic activity of catalysts, and degradation products. After discussing their impact on the creation and modification of reactive species, the effects on the stability of catalysts and oxidants (persulfate and H2O2) are presented. Additionally, the impact on the catalytic activity of catalysts is examined. Lastly, a summary of the impact of organic pollutants on the breakdown of their intermediate products is provided. To thoroughly assess the impact of inorganic anions on the functionality of AOPs, this review offers insight into the underlying influence mechanisms of inorganic anions on AOPs. A z-scheme Ag2S/BiVO4@Al2O3 configuration was proposed by Fakhravar et al. (2020) for the removal of MNZ in water matrices. Their findings demonstrated slower degradation rates in tap water when SO42−, HCO3−, Ca2+, and Mg2+ ions were present. Tap water contains several cations and ions. Studies have shown that the photodegradation efficiency of catalysts in tap water is lower compared to deionized water due to the presence of several ions that compete for the active sites of the photocatalyst. Table 4 provides a summary of some of these studies.

Comparison of photodegradation studies of dyes conducted in deionized water and tap water.

| Photocatalyst and dye | Degradation in deionized water | Degradation in tap water | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ag/P@BC; Rhodamine B(RhB) | 83.1 % using visible radiation | 75.8 % using visible radiation | Mu et al. (2021) |

| Ag NPs/TiO2/Ti3C2Tx; MB and RhB | 100 % in 15 min under UV radiation | Lower than 100 % in 15 min under UV radiation | Othman et al. (2021) |

| Cuo/NC NPs and CuO NPs; Methyl Orange (MO) | 97.2 % by Cuo/NC NPs and 68.2 % by CuO NPs in 4 min using UV radiation | 47.3 % by Cuo/NC NPs and 23.4 % by CuO NPs in 4 min using UV radiation | Khan et al. (2020b) |

| Fe–TiO2 nanotubes; Congo red(CR) | 86 % using visible radiation | 74 % using visible radiation | Zafar et al. (2021) |

| SnO2/SiO2 NPS and SnO2 NPS; Orange II (O ll) | 94.6 % by SnO2/SiO2 NPS and 65.9 % by SnO2 NPS in 30 min using UV radiation | 8.9 % by SnO2/SiO2 NPS and 22.8 % by SnO2 NPS in 30 min using UV radiation | Khan et al. (2020a) |

Additional ROS, including nitrogen dioxide radicals (NO2·) and peroxynitrite (ONOO−), can be produced by NO3− ions and contribute to degradation when exposed to UV light. The ·OH can also be scavenged by NO3−, which lowers the radical’s availability for pollutant breakdown. Depending on the circumstances, the effect can be either promotive or inhibitory (Alegre et al. 2000). As demonstrated by the subsequent reaction, NO3−, for instance, increased degradation in certain systems by producing more ROS but inhibited it in others by scavenging hydroxyl radicals: hv + NO3− → NO2· + O·.

When SO42− ions react with hydroxyl radicals or photogenerated holes, they can produce sulfate radicals (SO4·−), which are highly reactive and can accelerate degradation. Ao et al. (2004) reported that SO42− can adsorb onto the movement of contaminants toward the photocatalyst and compete with pollutants for active sites. The reaction where SO42− exhibited slight enhancement of degradation for specific pollutants due to sulfate radical generation (Xia et al. 2020) indicates that the effects are generally neutral or slightly promotive due to sulfate radical formation: SO42− + h+ → SO4·−.

Using a laboratory photoreactor, Pérez-Lucas et al. (2024) evaluated the efficiency of UV/S2O82− against heterogeneous photocatalysis employing UV/TiO2 processes on the breakdown of two widely used herbicides (terbuthylazine and isoproturon) in aqueous solutions. Furthermore, an investigation was conducted on the impact of the UV wavelength on the effectiveness of herbicide degradation. Even though the rate of degradation was higher under UV (254 nm)/S2O82− than under UV (365 nm)/S2O82−, it only took 30 min under UV-365 nm to completely degrade the herbicides (0.2 mg/L) when applying a 250 mg/L Na2S2O8 dosage in the absence of inorganic anions.

The individual and combined impacts of sulfate (SO42−), bicarbonate (HCO3−), and chloride (Cl−) were assessed to determine the impact of the water matrix. These can combine with sulfate (SO4·−) and hydroxyl (HO·) radicals produced during AOPs to generate new radicals with a lower redox potential. The findings indicated that SO42− had very little influence and that the decline in herbicide removal effectiveness observed when dealing with complex matrices was primarily due to the interaction between HCO3− and Cl−. The primary intermediates found during the photodegradation process are finally identified, and possible pathways, including dealkylation, dechlorination, and hydroxylation, are suggested and examined.

Strong adsorption of PO43− ions onto photocatalyst surfaces can obstruct active sites. According to Wang and Wang (2021), PO43− can form compounds with photocatalysts, altering their activity and potentially reducing the generation of ROS. Strong adsorption onto active sites typically causes inhibitory effects. For example, PO43− hindered dye degradation by adsorbing onto TiO2 and reducing active site availability. The effects of NaF and NaH2PO4 on rutile photocatalysis were studied by Sheng et al. (2013) These anions were detrimental to phenol degradation in aqueous solution, and the tendency was opposite to that observed with anatase, brookite, and P25 (a mixture of anatase and rutile). However, these anions were advantageous after rutile was deposited with 0.5 % Pt; the pattern was comparable to that seen for Pt-deposited anatase and P25. Interestingly, fluoride was about three times more active than phosphate at the same quantities on Pt/rutile, as noted for Pt/anatase. However, as phosphate’s adsorption increased at a surface covering more than 90 %, its beneficial effects decreased. Phosphate and fluoride promoted the hole oxidation of phenol while inhibiting the adsorption and reduction of O2, according to an independent measurement using a rutile film electrode. A tenable mechanism is proposed that involves the hole oxidation of phosphate into anion radicals and the fluoride-induced enhancement of bridged oxygen/hydroxyl radical formation.

For the breakdown of tetracycline (TC) in various aqueous conditions, a photocatalyst utilizing N and P co-doped carbon quantum dots (CQDs)-modified Ag3PO4 unified graphene hydrogel showed only a slight reduction in photocatalytic efficacy. Bicarbonates were the most effective in inhibiting the TC breakdown of the anions tested. Zeta potential measurements of photocatalysts in different electrolytes suggest a likely correlation with blocking mechanisms (Chen et al. 2020).

When esomeprazole was removed using a g-C3N4/NiO/ZnO/Fe3O4 nanohybrid photocatalyst, it was observed that nitrate and sulfate ions had more limiting effects, whereas Cl− decreased removal efficiency. Phosphate ions, carbonate, bicarbonate, and fluoride all exhibited inhibitory effects. The impact of metal cations on the breakdown of esomeprazole was investigated. When Na+, Ca2+, or Al3+ were added to UPW, the removal efficiency of the reported system decreased. An investigation into the effects of organic matter in water was carried out in UPW using isopropanol, acetone, sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), and humic acid sodium salt (HAS). The organic materials delayed decomposition, possibly due to photosensitization, except for acetone (Raha and Ahmaruzzaman 2020). Tolosana-Moranchel et al. (2020) investigated the impact of an organic water matrix on the photodegradation of four phenolic compounds – phenol, 4-nitrophenol, 4-chlorophenol, and methyl-p-hydroxybenzoate, using two commercial TiO2 catalysts (Aeroxide® P25 and Hobbikat UV-100) that have very different physicochemical characteristics. To compare the two TiO2 photocatalysts, slight variations in the photodegradation rates of these four aromatic compounds were noted. HO is added to the aromatic ring in two steps to initiate the photocatalytic reaction (addition-elimination). The second phase is rate-determining, with electron-withdrawing substituents lowering the reaction rate, as demonstrated by Hammett linear free energy equations. When HOMBIKAT® TiO2 was added to tap water, a photo process mediated by HO radicals created from the photogenerated holes was the most significant. However, in the photocatalytic degradation process using TiO2 P25, conduction band electrons and ROS produced from CB electrons were crucial. The primary reason for the activity loss observed when P25 was used in the presence of Na2CO3 or NaHCO3 was the pH shift, as there was no discernible impact on the production of HO radicals. Conversely, HOMBIKAT® TiO2 showed faster HO radical production and increased photoactivity when ions were present. These notable distinctions can be attributed to the fact that HOMBIKAT® TiO2 has demonstrated a higher surface area and a more negatively charged surface than P25, which inhibits the strong adsorption of anions. The Br− can react with ROS to produce hypobromous acid (HOBr) and bromine radicals (Br·), which can then participate in additional reactions. Br− can change the routes of degradation by forming complexes with contaminants or ROS. Less reactive bromine species are typically formed as a result of inhibitory actions. Because the bromine radicals produced by the Br− ions were less efficient at breaking down the contaminants, the degradation of organic dyes was reduced: Br· + OH− → Br− + ·OH.

The overall photocatalytic efficiency can also be impacted by the synergistic or antagonistic interactions between several anions (Türkyılmaz et al. 2017). The complex interactions between Cl− and SO42− resulted in a net decrease in photocatalytic effectiveness, with Cl− inhibiting degradation and SO42− providing a modest increase. Anions can alter a photocatalyst’s surface charge, hydrophilicity, and electrical characteristics, affecting the catalyst’s overall activity. It was discovered that high concentrations of Cl− and NO3− altered the photocatalyst’s surface characteristics of TiO2, influencing how it interacted with contaminants and produced ROS.

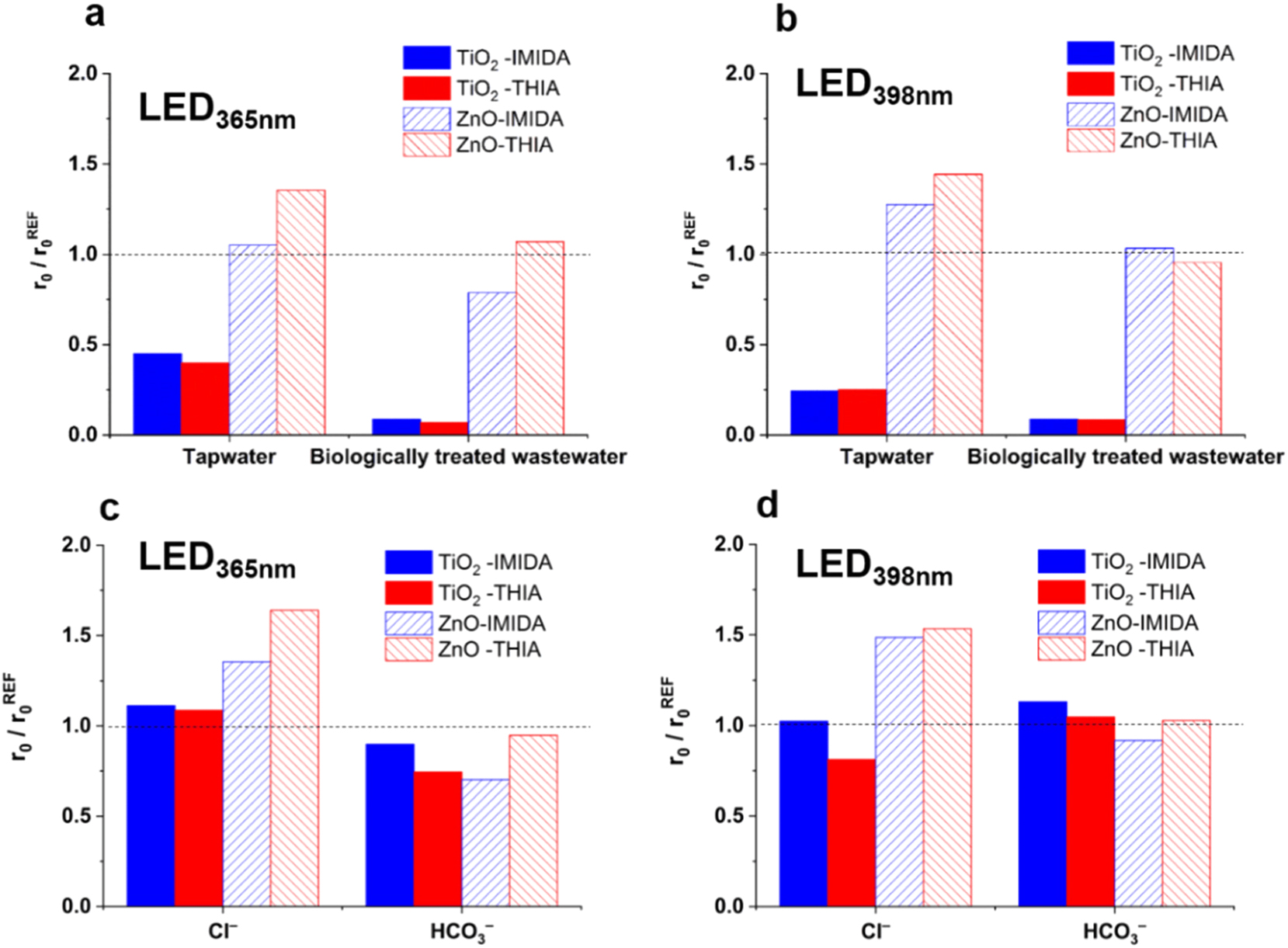

The use of commercial, low-cost LED398nm and high-power LED365nm for heterogeneous photocatalysis with TiO2 and ZnO photocatalysts was investigated by Náfrádi et al. (2021), with particular attention paid to the effects of matrices and components on radical formation, as well as light intensity, photon energy, and quantum yield. The effects of various LEDs, matrices, and inorganic ions were examined using two neonicotinoids: imidacloprid (IMIDA) and thiacloprid (THIA). In genuine matrices employing both light sources, the transformation rates of imidacloprid IMIDA and THIA for TiO2 were significantly decreased; however, for ZnO, matrices had no effect on removal rates and increased them (Figure 5a and b). While Cl-had no effect on TiO2, using ZnO significantly accelerated the transformation rate (Figure 5c and 5d).

Relative initial transformation rates of IMIDA and THIA measured (a, b) in different water matrices and (c, d) in the presence of Cl− and HCO3− (Náfrádi et al. 2021).

Guo et al. examined key elements and processes influencing the photodegradation of organic micropollutants (OMPs) in the aquatic environment (Guo et al. 2024). Photochemical reactions widely occur in the aquatic environment and play fundamental roles in aquatic ecosystems. Solar-induced photodegradation is extremely effective for many organic micropollutants, particularly those that cannot be hydrolyzed or biodegraded, thus helping to reduce chemical pollution. According to recent research, photodegradation may play a more significant role than biodegradation in several OMP conversions in aquatic environments.

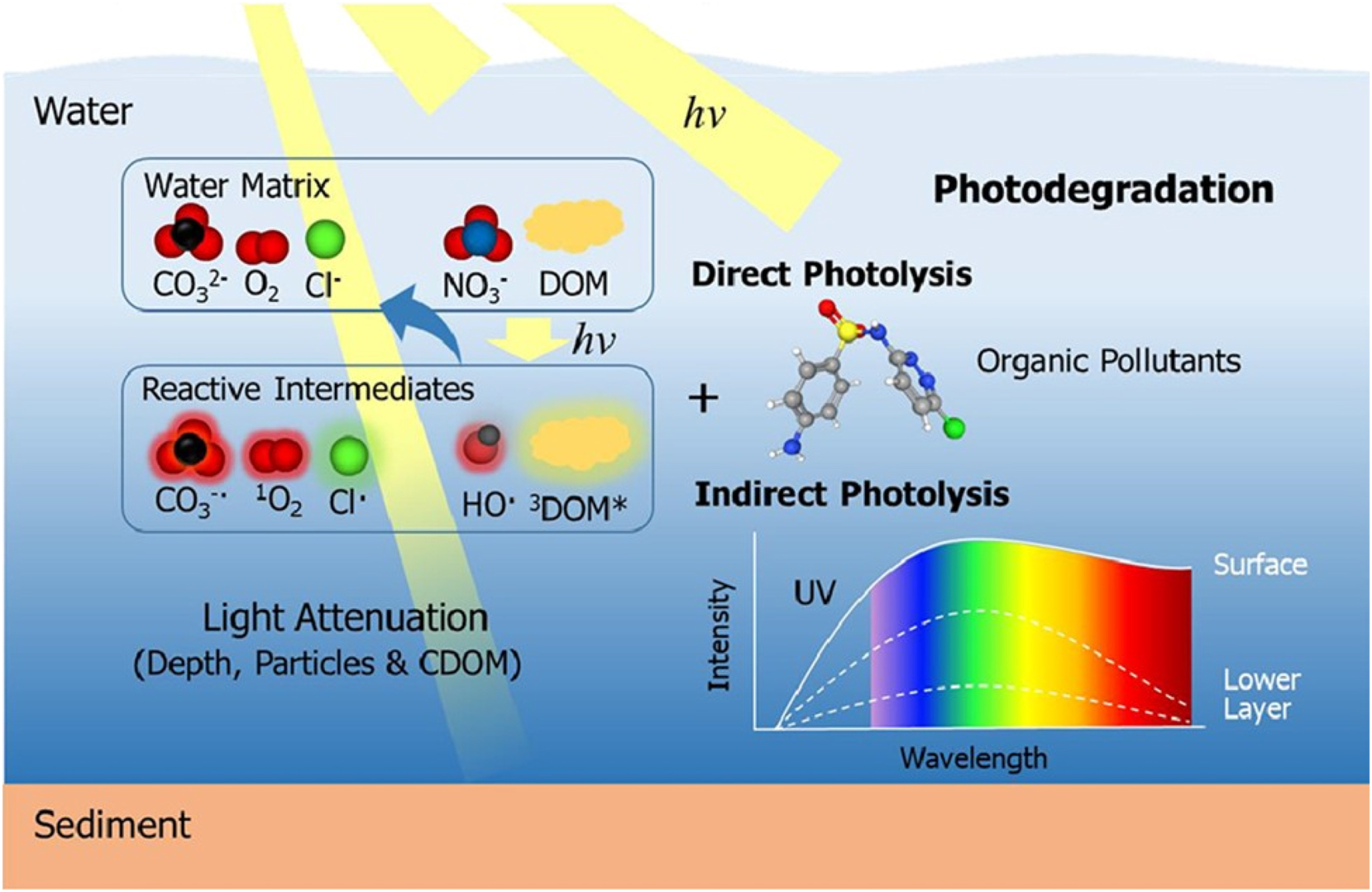

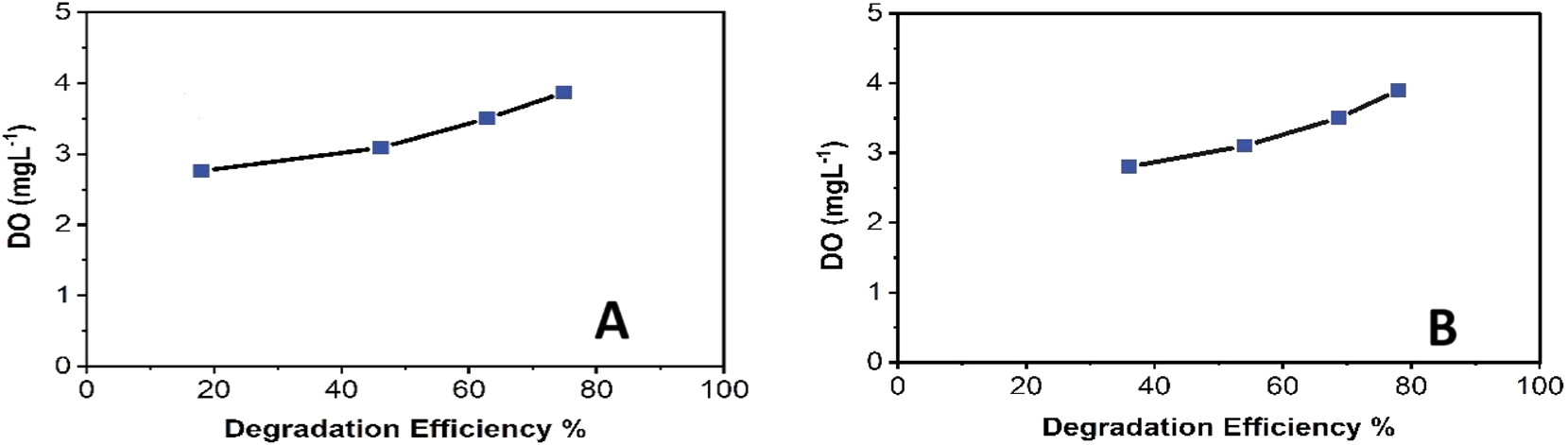

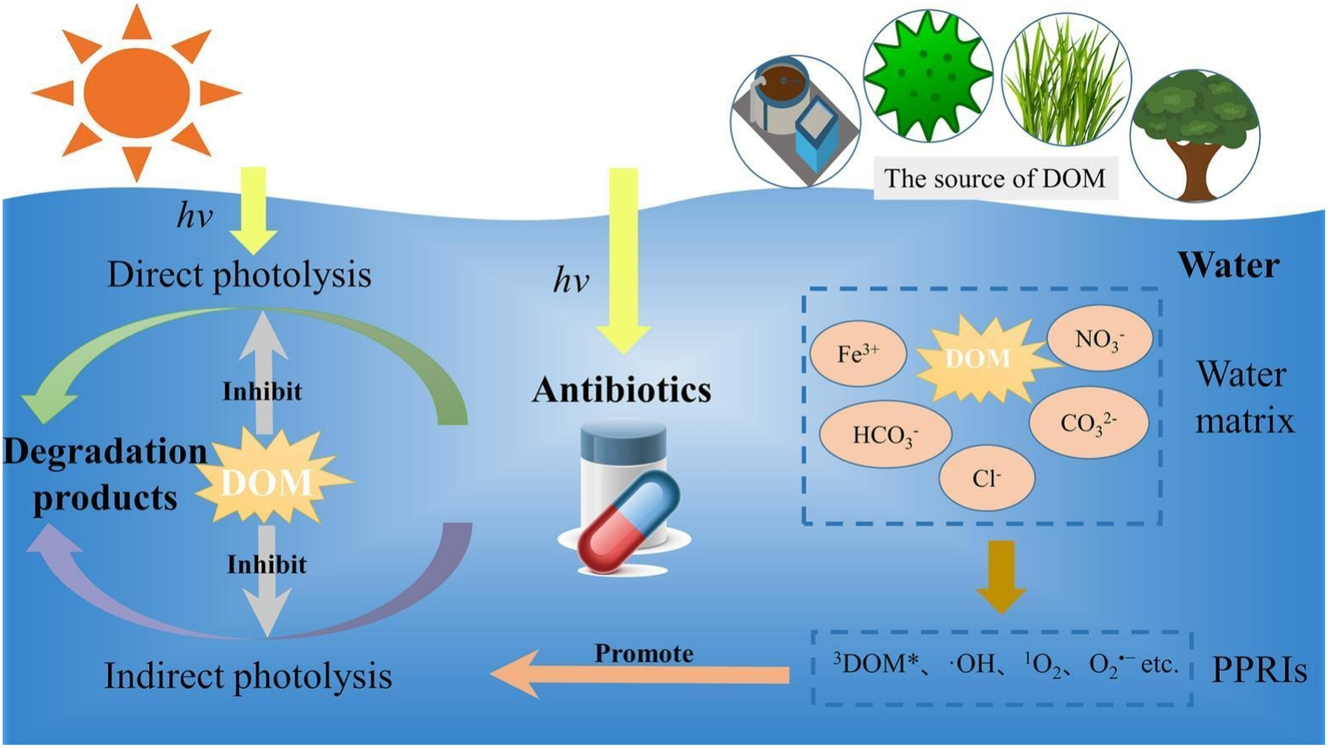

The water matrix, including pH, inorganic ions, and DOM, can all affect photodegradation. The effect of the water matrix, such as DOM, on photodegradation is complex, and fresh findings on the diverse impacts of DOM have just been published. Furthermore, physical elements such as latitude, water depth, and temporal fluctuations in sunlight all impact the photodegradation process since they control the lighting conditions. However, understanding the significance of photodegradation in the aquatic environment remains challenging due to the variety and complexity of the processes involved. As a result, this study provides a succinct explanation of the relevance of photodegradation and the various processes involved in OMP photodegradation, focusing on recent advances in primary DOM reactions. In addition, important knowledge gaps in environmental photochemistry are identified. Figure 6 depicts the direct and indirect photolysis of organic contaminants in the presence of a water matrix and reactive intermediates.

Direct and indirect photolysis of organic pollutants in the presence of a water matrix and reactive intermediates (Guo et al. 2023). Reproduced with permission from Elsevier.

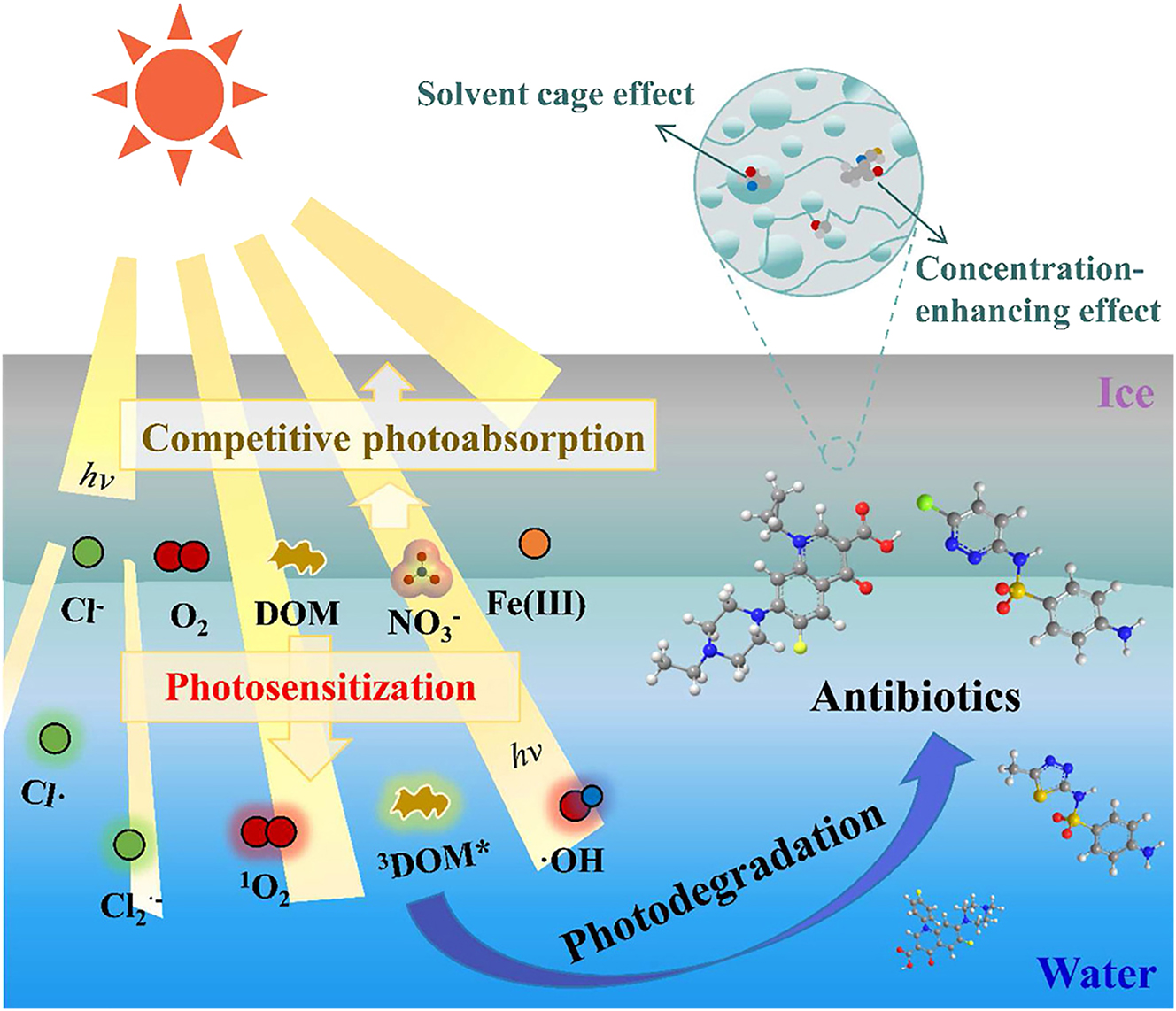

Ge et al. investigated the photodegradation and impacts of the major dissolved components on the photolytic kinetics of sulfonamides (SAs) and fluoroquinolones (FQs) in ice/water under simulated sunlight (Ge et al. 2024). The results revealed that the photolysis of sulfamethizole (SMT), sulfachloropyridazine (SCP), enrofloxacin (ENR), and difloxacin (DIF) in ice/water followed pseudo-first-order kinetics. Individual antibiotics exhibited varying photodegradation rates in ice and water. This difference was attributable to the concentration-enhancing and solvent cage effects during the freezing procedure. Furthermore, the principal elements (Cl−, HASS, NO3−, and Fe(III)) demonstrated varied degrees of promotion or inhibition on the photodegradation of SAs and FQs in the two phases, depending on the individual antibiotics and the matrix. The extrapolation of laboratory results to field circumstances yielded a fair estimate of environmental photolytic half-lives (t1/2, E) between midsummer and midwinter in cold locations. The estimated t1/2, E values varied between 0.02 h for ENR and 14 h for SCP, depending on the reaction phases, latitudes, and seasons. These findings highlighted parallels and variations in the ice and aqueous photochemistry of antibiotics, which is critical for accurately assessing the fate and risk of these novel contaminants in freezing environments. Figure 7 shows the competitive photoabsorption, photosensitization, and photodegradation of antibiotics in the presence of anions, dissolved oxygen, and organic matter.

Competitive photoabsorption, photosensitization, and photodegradation of antibiotics in the presence of anions, dissolved oxygen, and organic matters (Ge et al. 2024). Reproduced with permission from Elsevier.

3.2 Influence of inorganic cations (Ca2+, Mg2+, Na+, K+, Al3+)

Wastewater contains a variety of cations, including calcium (Ca2+), magnesium (Mg2+), sodium (Na+), potassium (K+), and aluminum (Al3+) ions. Even in typical drinking water, alkali and alkaline earth metal cations are highly prevalent and can significantly impact the photocatalytic breakdown of organic contaminants. Their interactions with contaminants and photocatalysts determine the extent of their influence. Through surface charge alteration, complexation, precipitation, and ionic strength changes, water cations substantially affect the photocatalytic degradation of organic contaminants. The effects of calcium, magnesium, sodium, potassium, and aluminum ions vary from neutral to inhibitory, depending on their interactions with pollutants and photocatalysts. Understanding these impacts is essential for improving photocatalytic processes in water treatment applications.

Through ionic interactions or surface complex formation, cations can alter the adsorption behavior of both the cations and the organic contaminants. For instance, Ca2+ can modify the surface potential of TiO2, impacting the kinetics of pollutant adsorption. Certain cations can combine with organic contaminants or photocatalysts to form insoluble complexes or precipitates, blocking active sites or removing pollutants from the solution. Certain organic acids and magnesium ions can precipitate, reducing the amount of these contaminants available for degradation. The aggregation state of photocatalysts can also be influenced by cations, altering the effective surface area and light-absorbing capabilities. TiO2 nanoparticle aggregation can be induced by Na+ ions, which can induce the nanoparticles’ water dispersion and overall photocatalytic activity. This section discusses specific ions.

The photocatalyst surface may absorb Ca2+ ions, changing the surface charge and potentially generating calcium oxide. When combined with organic contaminants or photocatalysts, Ca2+ can precipitate, obstructing active sites or eliminating pollutants from the mixture. By forming calcium phenoxide and reducing active sites on the photocatalyst, Ca2+ hinders the breakdown of phenol.

Pollutant + Ca2+ -> Ca-pollutant complex (insoluble).

Using crystalline carbon nitride (CCN) as a photocatalyst has positively affected the degradation of naproxen (NPX) in tap water, river water, seawater, and wastewater. Research indicates that adding Ca2+ and Mg2+ ions to aqueous media enhances the breakdown of NPX by increasing the amount of pollutants adsorbed on the surface of the photocatalyst. Copper cations (Cu2+) may inhibit the removal of NPX by interacting with photogenerated electrons in the conduction band of CCN (Wang and Wang 2021). Lei et al. (2020) studied the degradation of levofloxacin (LVX) and norfloxacin (NOR) in groundwater and simulated hospital effluent using inverse opal potassium-doped carbon nitride photocatalysts, observing only a slight reduction in efficiency. A slight reduction in the photocatalytic degradation of NPX was noted when using carbon dot-adorned hollow porous carbon nitride nanospheres (Wu et al. 2020).

Magnesium hydroxide (Mg(OH)2) may form on the surface of the photocatalyst as a result of Mg2+ adsorption, altering the surface charge. Similar to Ca2+, Mg2+ can precipitate or form insoluble complexes with contaminants adsorbed on the catalyst’s surface. The degradation efficiency of dyes was decreased by MgO due to the formation of magnesium hydroxide on the photocatalyst’s surface. Reaction: Mg(OH)2 → Mg2+ + OH− (precipitate).

Na+ ions can change the solution’s ionic strength, affecting the electrostatic interactions between contaminants and the photocatalysts. Na+ ions can cause photocatalyst particle aggregation, altering the particles’ reactivity and dispersion. Due to potential aggregation and ionic strength-related effects, the effects of Al3+ ions are often neutral or slightly inhibitory. The aggregation of TiO2 nanoparticles has been found to cause a slight suppression of the breakdown of organic contaminants by Na+ ions. K+ similarly influences electrostatic interactions and ionic strength in the solution. Through surface charge modification, K+ can affect the adsorption of contaminants on the photocatalyst. Ionic strength and adsorption effects generally result in neutral or slightly inhibitory outcomes. Like Na2O, K2O does not significantly affect the degradation of drugs due to its role in regulating ionic strength. Al2O3 has a considerable capacity to adsorb onto the surface of the photocatalyst, significantly altering the surface charge and potentially generating aluminum oxide (Al2O3). Al2O3 and organic pollutants can form strong complexes, which may limit the degradation potential of organic pollutants. Due to significant surface adsorption and complex formation, the effects are often inhibitory. Through the formation of strong complexes and the modification of the surface characteristics, Al3+ ions significantly impede the degradation of organic dyes. Pollutant + Al3+ -> Al-pollutant complex (strong interaction).

Depending on their cumulative effects on surface characteristics and pollutant interactions, various cations can interact in ways that either enhance or decrease photocatalytic efficiency. A combination of Ca2+ and Na+ had a complex effect, with the inhibitory actions of Ca2+ being somewhat mitigated by the presence of Na+ due to competition for adsorption sites. Cations influence the surface charge and reactivity of the photocatalyst, altering the pH and total ionic strength of the solution. Elevated levels of Ca2+ and Mg2+ can change the ionic strength, affecting the electrostatic interactions between pollutants and the photocatalyst and resulting in varying degradation efficiencies.

3.3 Influence of natural organic matter

The photocatalytic breakdown of organic pollutants is significantly aided by natural organic matter (NOM) in water, including fulvic acids, biogenic organic compounds, and humic materials. Pollutants and photocatalysts can interact with NOM, producing various effects on the degradation process. Organic matter in water has a major impact on the photocatalytic destruction of organic pollutants by modulating pH and ionic strength, scavenging ROS, forming complexes, competing for adsorption sites, and absorbing light. The overall effect of NOM can vary based on the type of organic matter and the specific photocatalytic system, ranging from neutral to inhibitory. Understanding these interactions is imperative for optimizing photocatalytic water treatment systems. An extensive study of these consequences is presented below: Target organic contaminants and NOM compete for adsorption sites on the photocatalyst surface, resulting in fewer active sites available for pollutant degradation. For instance, humic acids can adsorb onto TiO2 surfaces, occupying positions typically occupied by contaminants like phenol, thereby reducing degradation efficiency. NOM can scatter and absorb light, particularly in the UV-visible spectrum, which decreases the number of photons available to activate a photocatalyst. This phenomenon is referred to as the “inner filter effect.” High concentrations of fulvic acid can absorb UV radiation, diminishing TiO2’s activation and, consequently, its capacity to produce ROS. This leads to lower degradation rates and reduced photocatalyst activation. Awfa et al. (2020) employed a CNT-TiO2 catalyst to photodegrade carbamazepine (10 mg/L) in raw water and wastewater when exposed to UV and solar radiation, discovering that NOM surrogates impeded the degrading process. ROS produced during photocatalysis, such as hydroxyl radicals (·OH) and superoxide anions (O2·−), can react with NOM, reducing the availability of these radicals for breaking down contaminants. Since humic materials can scavenge hydroxyl radicals, the availability of these radicals for degrading pharmaceuticals is diminished, thereby reducing the effectiveness of ROS (Klein et al. 2021). NOM can alter the reactivity and solubility of metal ions or contaminants by forming complexes with them, potentially changing the degradation pathways of contaminants or sequestering them away from the photocatalyst. Fulvic acids can combine with metal ions and other contaminants to create complexes that alter the free concentration of the pollutants available for degradation, thus changing the efficiency and pathways of degradation (Nikishina et al. 2022). The ionic strength and pH of the water are influenced by NOM, which can impact the ionization state of contaminants and the surface charge of photocatalysts. Humic acids can buffer pH, changing TiO2’s surface charge and interactions with ionizable contaminants. When acids and acids were added, humic acid exhibited buffering behavior, with significant buffering capacity observed when NaOH was introduced. According to Jingcheng et al. (Xu et al. 2021) humic acid demonstrates buffering activity between pH 5.5 and 8.0, with a maximal buffer capacity at pH 6.0. Humic compounds exhibit notable characteristics such as strong competitive adsorption onto photocatalyst surfaces, substantial absorption of UV-visible light, robust hydroxyl radical scavenging, and stable complex formation with pollutants. Due to these mechanisms, the effects are often inhibitory. By scavenging ROS and competing for adsorption sites, humic acids decrease the breakdown efficiency of organic dyes (Lee et al. 2023). ZnO nanoparticles were used by Makropoulou et al. (2020) for UV photodegradation of SMX, and the results indicated that the water matrix influences SMX removal. However, due to its sensitivity, humic acid significantly increased the removal of SMX in surface water. Materials with significantly higher activity are produced when copper phosphide (Cu3P) is dispersed across the BiVO4 surface. SMX was the target pollutant in bottled water (BW) and WW, and the water matrix effect was thoroughly examined using this information. BW did not influence removal at all, but WW kept SMX from being eliminated. Further investigations were conducted in synthetic water matrices employing suitable amounts of HA, bicarbonates, or chlorides in UPW to elucidate this phenomenon. In the case of HA, there was a considerable decrease in SMX clearance, suggesting the inhibitory effect of organic matter; however, in the case of NaCl, the decline was not as significant. Conversely, bicarbonates have been associated with positive results (Ioannidi et al. 2020). Compared to humic acids, fulvic acids exhibit weaker competitive adsorption onto active sites, absorb UV light (producing the inner filter effect), and react, albeit to a lesser extent than humic acids, with hydroxyl radicals. By absorbing UV radiation and scavenging ROS, fulvic acids slow down the breakdown of pesticides (Burrows et al. 2002).

In addition to competitive adsorption and contesting for adsorption sites, biogenic organic matter (BOM) also reacts with produced ROS, lowering their availability. It may release nutrients that impact microbial activity in the water, indirectly affecting photocatalysis. In addition to extra indirect effects from nutrient release, the overall effects are inhibitory. By scavenging ROS and competing for adsorption sites, BOM from algal blooms inhibited the breakdown of synthetic organic compounds (Paulino et al. 2023). The competitive adsorption of algal organic matter (AOM) causes it to adsorb onto photocatalysts and react with ROS, decreasing its effectiveness. Similar to BOM, which can release nutrients that influence microbial processes, resulting in comparable nutritional impacts. Because of adsorption competition and ROS scavenging, the effects are often inhibitory. By scavenging hydroxyl radicals and occupying photocatalyst surfaces, AOM diminishes the degradation of pharmaceuticals (Pivokonsky et al. 2021). Pollutants and NOM can combine to create complex mixtures that may affect degradation efficiency in beneficial and detrimental ways. The potent ROS scavenging and competitive adsorption of humic compounds and pharmaceuticals result in decreased degradation efficiency. NOM can modify the surface characteristics of photocatalysts, including their charge, aggregation state, and hydrophilicity, thereby impacting their overall activity. The photocatalytic effectiveness of TiO2 was affected by high concentrations of humic acids due to changes in its surface charge and dispersion state. The creation of secondary pollutants as a result of the interaction between NOM and ROS may exacerbate the degradation process. Fulvic acids and hydroxyl radicals can react to produce byproducts that are pollutants in and of themselves, necessitating further treatment. High amounts of dissolved organic carbon (DOC) absorb ROS, limiting their availability for degrading contaminants. Pollutants and DOC compete for the same adsorption sites on the photocatalyst. High levels of DOC often inhibit photocatalytic processes. According to Dong S. et al. (2023) elevated DOC from urban runoff inhibited the photocatalytic breakdown of pharmaceuticals.

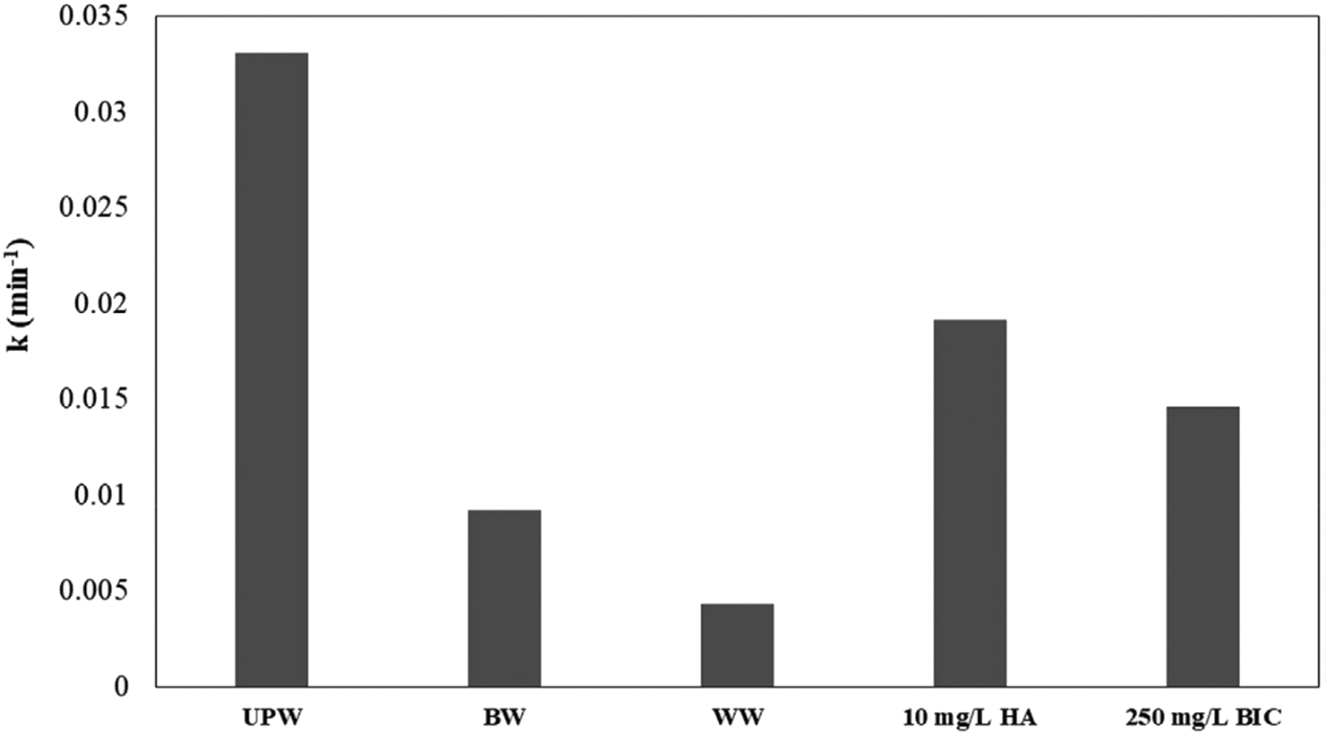

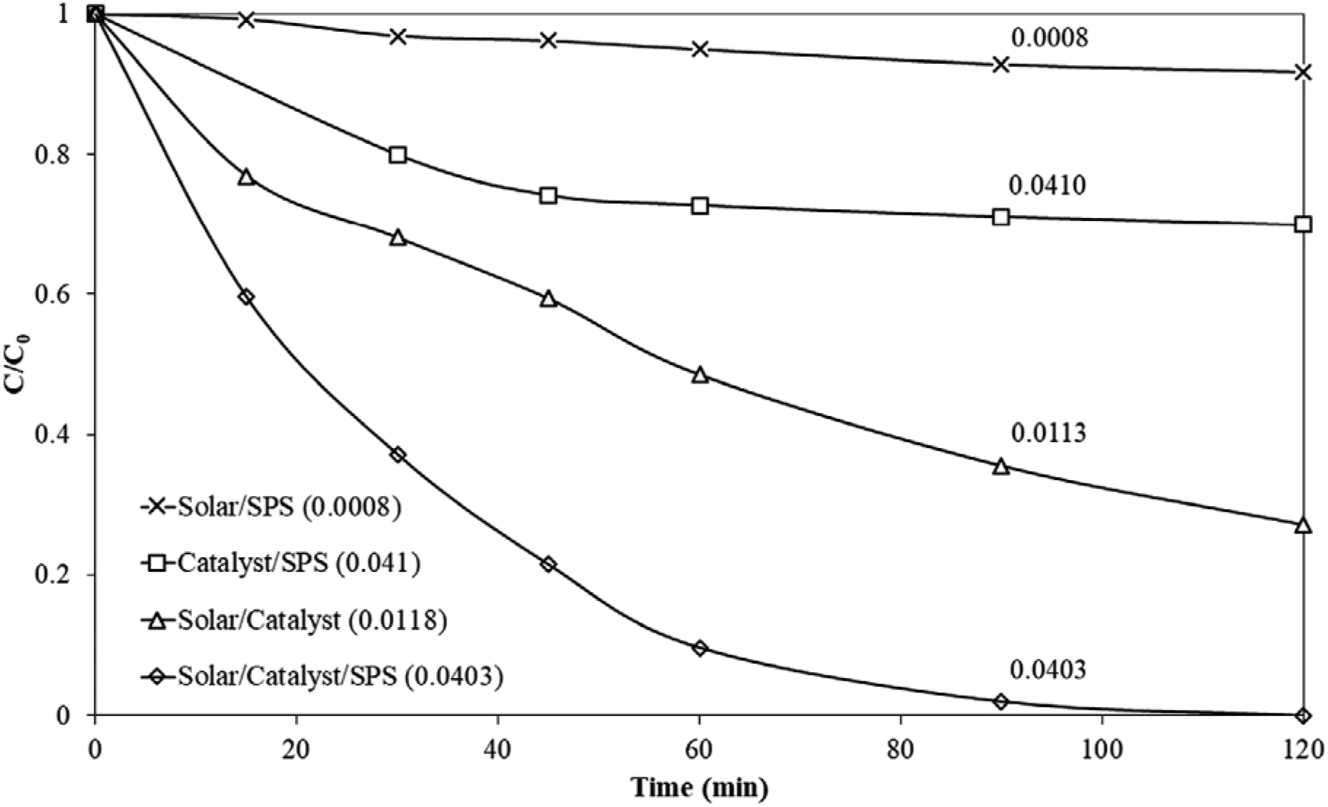

When compared to UPW, Figure 8 demonstrates a significant decrease in the apparent kinetic constant of methylparaben (MeP) degradation by a factor of about 4 and 8, respectively, in the BW and secondary treated WW matrix. The presence of organic and inorganic materials competing for reactive radicals, the slightly alkaline nature of BW and WW, and the effect of solution pH all contribute to the matrices’ detrimental effects on MeP degradation. The drop in MeP over time for the several systems under evaluation is depicted in Figure 9. After 120 min, little MeP was eliminated when the Solar/SPS (sodium persulfate) system was exposed to solar light, suggesting that S2O8− was not significantly activated. MeP elimination in the dark (Catalyst/SPS system) is limited to about 30 %, indicating that the catalyst only slightly activates the oxidant. MeP degradation was greatly enhanced by adding SPS to the Solar/Catalyst system compared to the original setup. MeP was completely degraded after the addition of SPS within 60–90 min of treatment. Compared to the photocatalytic process alone, the combined process (Solar/Catalyst/SPS) exhibited an apparent rate constant that was four times greater (Arvaniti et al. 2020).

Rate constants of 125 μg/L methylparaben (MeP) degradation with g-C3N4 in actual water matrices and UPW spiked with non-target substances at various concentrations (Arvaniti et al. 2020). Reproduced with permission from Wiley.

Effect of sodium persulfate (SPS) (250 mg/L) on the catalytic photodegradation of 500 μg/L MeP with 100 mg/L g-C3N4 under solar irradiation in UPW. Numbers next to lines show the apparent rate constant, k/min (Arvaniti et al. 2020). Reproduced with permission from Wiley.

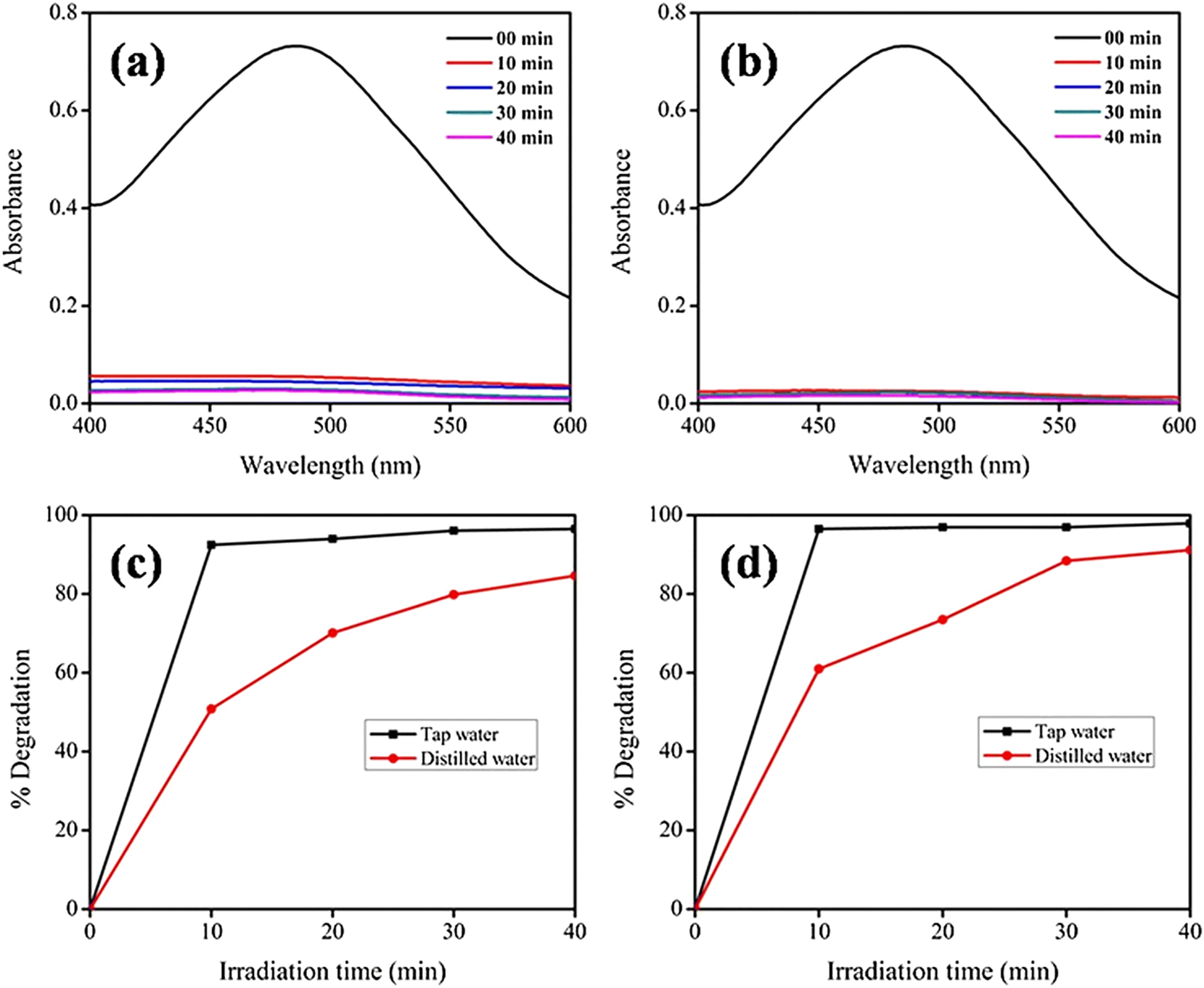

Ahmad S. et al. conducted a literature analysis to assess the effect of tap water contents on the photodegradation of organic pollutants such as dyes, pharmaceuticals, and pesticides (Ahmad et al. 2023). The TW had a variety of effects on organic pollutant photodegradation, which may have increased or decreased photodegradation effectiveness. TW contains carbonates, bicarbonates, chlorides, oxides, sulfates, and phosphates of various metal ions such as Fe2+, Mg2+, Ca2+, and Si2+ (Bathla et al. 2022). The photocatalysts Fe3O4 NPs and Fe3O4/ZrO2 degraded methyl red dye more efficiently in TW than distilled water, as shown in Figure 10 (Khan I. et al. 2020c). Inorganic ions such as SO42−, HCO3−, and Cl− have a dual effect on the photodegradation of organic pollutants, depending on photocatalyst types and ion concentrations (Khan et al. 2022). In a Fe(III)/chlorine degradation system for reactive green 12, Cl2·− was found to be primarily responsible for a significant decrease in dye concentrations, whereas Cl· and ·OH contributed to only ∼5 % of the overall removal efficiency. Mineral ions, including SO42−, NO32−, HCO3−, and CO32−, negatively impacted photocatalytic decolorization when mineralizing Reactive Orange 16 with TiO2 NPs. Similarly, cations in wastewater influence organic dye photodegradation. BiOI microspheres destroyed 84 % of oxytetracycline in pure water and 92 % in TW after 5 h of visible light exposure. The greater rate of degradation in TW employing bismuth oxyiodide may be due to dissolved components such as nitrate ions. The photolysis of nitrate can significantly increase the formation of hydroxyl radicals, which are highly reactive in the photodegradation of organic contaminants. Adding Na2SO4 suppresses the photodegradation of sulfonamides by TiO2. Inorganic anions in water had no significant effect on the breakdown of sulfadiazine with N-doped coconut-shell biochar as a catalyst. Similarly, DOM, phosphate, and ferrous ions inhibit the degradation of DCF, with inhibition becoming stronger as the concentrations of DOM, phosphate, and ferrous ions increase (Gao et al. 2020).

UV/Vis spectra of methyl red dye in tap water before and after reaction using (a) Fe3O4 NPs, (b) Fe3O4/ZrO2 NPs, (c) % degradation comparison of methyl red dye in distilled and tap water photodegraded by Fe3O4 NPs, and (d) % degradation comparison of methyl red dye in distilled and TW photodegraded by Fe3O4/ZrO2 NPs (Khan, I. et al. 2020c). Reproduced with permission from Springer Nature.

CaCO3 has also been extracted from TW as a white powder sintered at 900 °C and applied for the efficient adsorption/degradation of rhodamine B dye (Bathla et al. 2022). Inorganic cations, such as Na+, K+, Ca2+, and Mg2+, are also present in natural waters and affect the photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants (Ahmad et al. 2023).

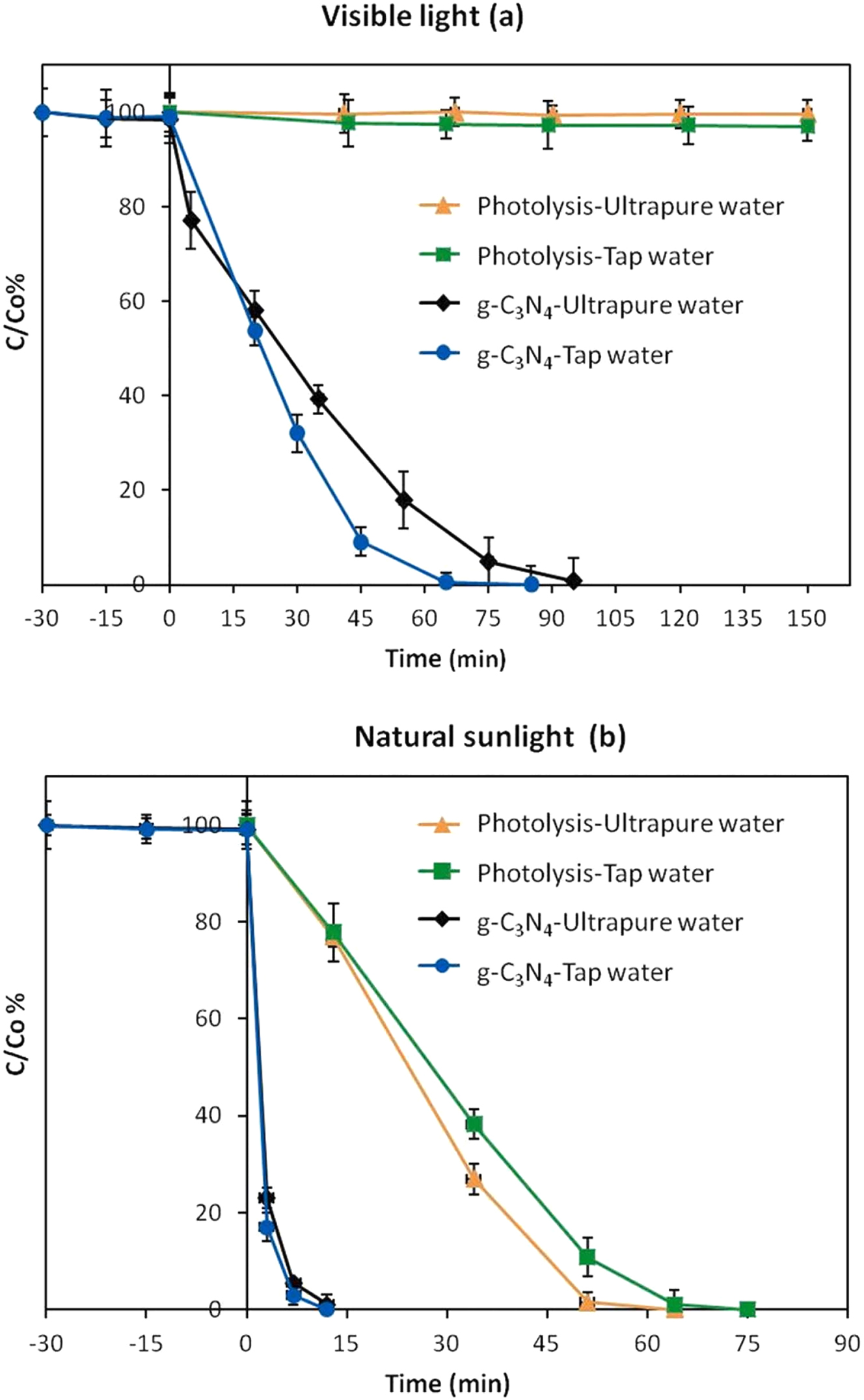

Jiménez-Salcedo et al. conducted the photodegradation of naproxen under visible light radiation and natural sunlight in tap water and ultrapure water using a g-C3N4 photocatalyst and without any catalyst (Jiménez-Salcedo et al. 2022). Figure 10 shows higher degradation of naproxen using g-C3N4 photocatalyst compared to the absence of a catalyst. Moreover, tap water shows reduced degradation of naproxen compared to ultrapure water due to the various ions present in tap water that interact with naproxen (Figure 11).

Photodegradation of naproxen through g-C3N4 under (a) visible light radiation, (b) natural sunlight (Jiménez-Salcedo et al. 2022). Reproduced with permission from Elsevier.

3.4 Influence of pH

pH is a crucial factor that significantly affects the photocatalytic breakdown of organic contaminants. It influences the photocatalyst’s surface charge, the ionization state of pollutants, the generation of ROS, and the adsorption-desorption equilibria. By affecting the surface charge of the photocatalyst, the ionization state and availability of pollutants, the production of ROS, and the adsorption-desorption equilibria, pH plays a substantial role in the photocatalytic destruction of organic pollutants. In practical applications, optimizing pH can enhance photocatalytic effectiveness by avoiding the drawbacks and advantages of acidic, neutral, and basic pH environments. An extensive examination of how pH affects photocatalytic degradation is provided below: The pH level at which there is no charge on the photocatalyst surface is known as the point of zero charge (PZC). The surface is negatively charged above the PZC and positively charged below it, affecting the charge-dependent adsorption of contaminants. With a PZC of around 6.8, TiO2 exhibits a positively charged surface that attracts anionic pollutants in acidic conditions (pH < 6.8) and a negatively charged surface that attracts cationic pollutants in basic settings (pH > 6.8). The results adjust the adsorption effectiveness according to the pH and pollutant charge to the PZC. Pollutants and the photocatalyst interact electrostatically, which depends on the surface charge, which changes with pH. These interactions can promote or prevent adsorption and subsequent degradation. Strong electrostatic attraction to positively charged TiO2 surfaces enhances the degradation of anionic dyes at acidic pH values. Depending on the pH, various organic contaminants can exist in distinct ionization states, influencing their solubility, reactivity, and adsorption on the photocatalyst surface. The ionization of phenol fluctuates with pH, impacting the effectiveness of phenol adsorption and degradation in TiO2-based photocatalysis. When the pH exceeds neutral, phenol exists as phenolate ions with different adsorption properties. Pollutant solubility and dissociation are influenced by pH, affecting their availability for photocatalytic destruction. Under basic conditions, weak organic acids become more soluble and more accessible for breakdown. One important ROS in photocatalysis, hydroxyl radicals (·OH), develop in a pH-dependent manner. Generally, basic conditions facilitate the production of ·OH radicals from hydroxide ions or water. In ZnO photocatalysis, the breakdown of pollutants such as atrazine was boosted by the increased production of hydroxyl radicals in basic conditions (pH > 7). pH also affects the creation of superoxide anions (O2·−). Basic conditions enable the production of O2·− from dissolved oxygen. Under basic conditions, there was a greater formation of superoxide anions, which improved the degradation of organic dyes in TiO2 photocatalysis. By changing the surface charge and ionization state of the contaminants, pH modifies their adsorption isotherms on the photocatalyst surface. Because TiO2 has a negative surface charge, it was discovered that basic dyes like MB absorb more at basic pH and can influence the desorption of intermediate degradation products, affecting the degradation process as a whole. In ZnO photocatalysis, faster desorption of acidic intermediates at basic pH reduced surface fouling and increased overall degradation efficiency. Extremely high or low pH levels can compromise the stability of the photocatalyst, causing it to degrade or become inactive. In highly acidic circumstances (pH < 3), TiO2 demonstrated decreased stability and activity, reducing catalyst degradation efficiency. The photocatalyst’s band gap and activation can be influenced by pH, impacting the photocatalytic activity of the catalyst. ZnO’s photocatalytic activity was modified by slight variations in its band gap at different pH levels, which could either increase or decrease activity. Anionic pollutants are drawn to positively charged photocatalyst surfaces in acidic environments, promoting adsorption and degradation. Increased anionic dye degradation rates in TiO2 photocatalysis were observed at acidic pH levels. Oxygen radicals and superoxide anions are examples of ROS that can be produced less frequently in acidic environments. Degradation rates of neutral contaminants were lowered by reduced hydroxyl radical formation at acidic pH in ZnO photocatalysis, which consequently reduced degradation efficiency since fewer ROS were generated. A balanced surface charge may be produced by neutral pH levels, maximizing the adsorption of both cationic and anionic contaminants. TiO2 photocatalysis demonstrated balanced adsorption of cationic and anionic dyes at neutral pH, resulting in moderate degradation rates. Ideal conditions for the formation of ROS are frequently found at neutral pH without causing drastic changes in surface charge. Optimal production of hydroxyl radicals at a pH close to neutral enhanced the degradation effectiveness of various contaminants in ZnO photocatalysis. Basic conditions improve the effectiveness by promoting the generation of ROS, such as superoxide anions and hydroxyl radicals. In basic conditions (pH > 7), higher rates of hydroxyl radical generation enhanced phenol degradation rates in TiO2-based photocatalysis. Under standard circumstances, anionic pollutants are repelled from negatively charged photocatalyst surfaces, decreasing adsorption. Lower degradation rates for these contaminants resulted from reduced anionic dye adsorption at basic pH in TiO2 photocatalysis. The effectiveness of photocatalysis can be increased by adjusting pH to match the ideal conditions for adsorption and degradation for a given set of contaminants. The best conditions for adsorption and degradation were achieved by adjusting pH to 5–6 for the degradation of anionic dyes in TiO2 systems. Buffering agents can maintain stable pH conditions during photocatalysis to avoid fluctuations that could lower efficiency. Buffering solutions were utilized to maintain a neutral pH and maximize the breakdown of mixed contaminants by ZnO photocatalysis.

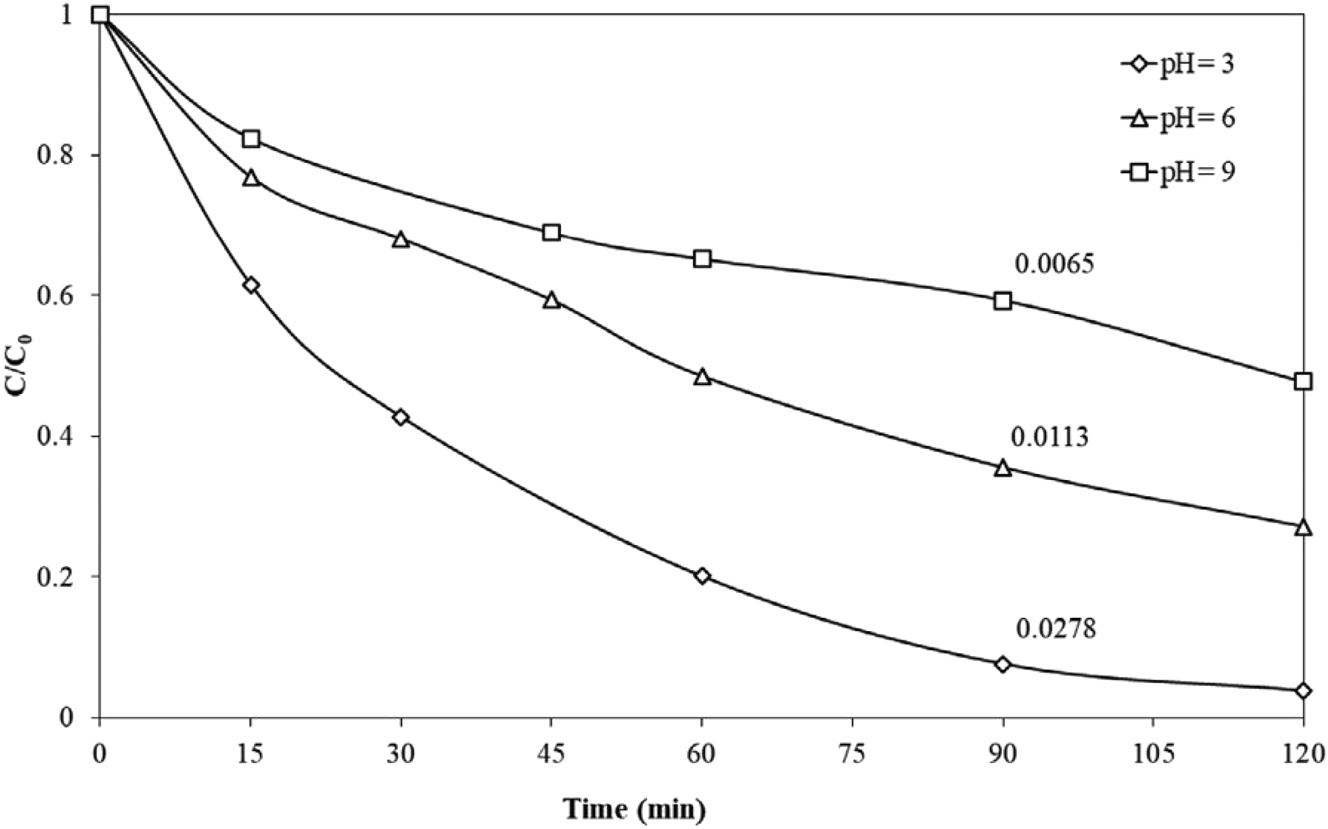

The pH dependence of the MeP degradation rate is illustrated in Figure 12. MeP degrades more quickly and is almost eliminated after 90 min of radiation when the initial pH is 3. Degradation was less effective in an alkaline atmosphere despite intrinsic conditions producing a reasonable elimination percentage. After a 120-min treatment, 52 % and 73 % of 500 μg/L MeP were eliminated at pH 6 and 9, respectively (Arvaniti et al. 2020).

Effect of initial pH on 500 μg/L MeP degradation with 100 mg/L g-C3N4 under solar irradiation in UPW. Numbers next to lines show the apparent rate constant, k min−1 (Arvaniti et al. 2020). Reproduced with permission from Wiley.

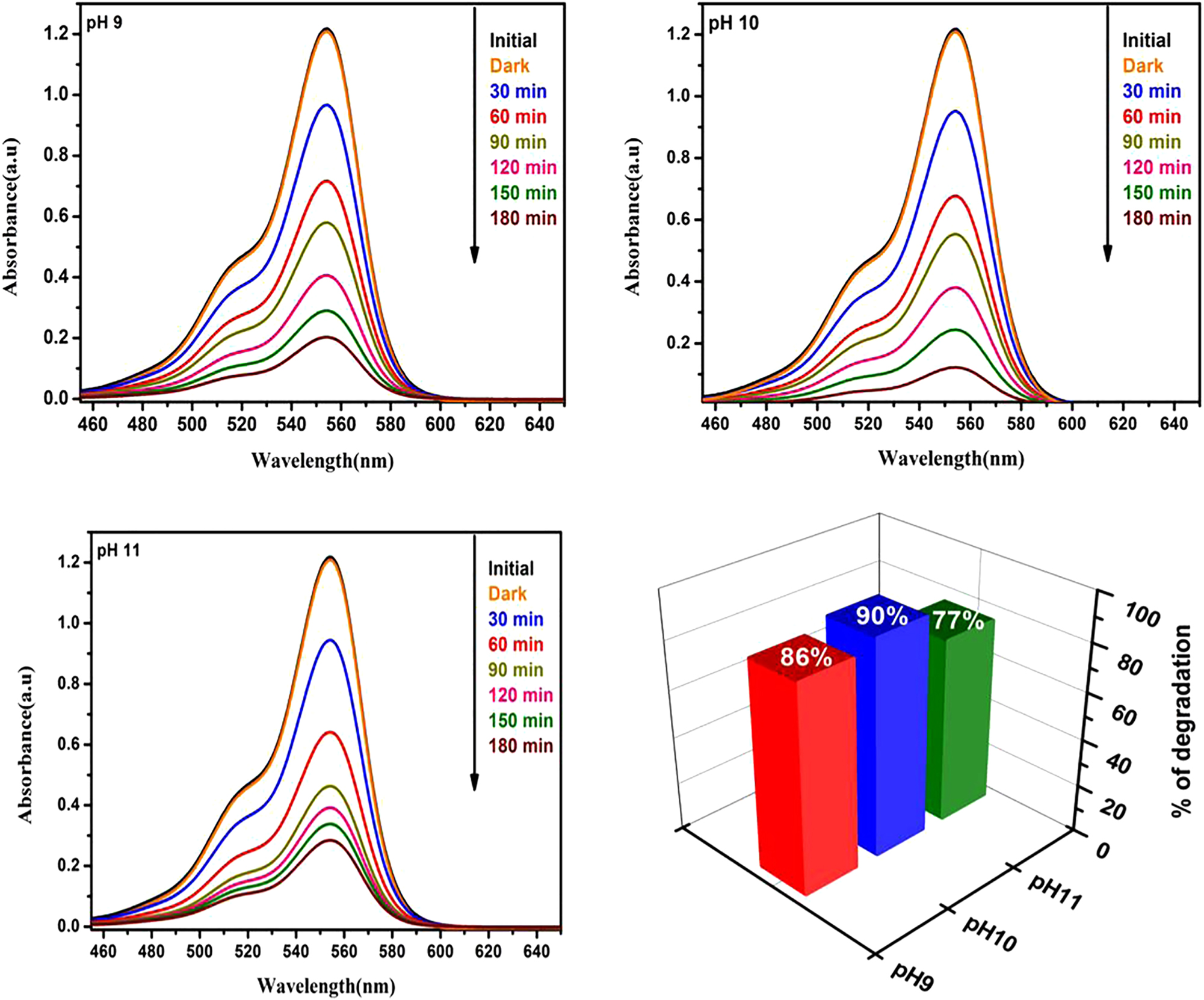

The efficacy of water treatment can be enhanced by combining pH correction with photocatalytic treatments, as this will hasten the elimination of pollutants. Pre-treatment with acidity followed by TiO2 photocatalysis improved the rates at which pharmaceuticals broke down in wastewater. When photocatalytic devices are adjusted to the local pH values of industrial and natural waters, good performance can be achieved without requiring large pH modifications. Pollutant degradation rates were higher in photocatalytic systems that operate well in naturally occurring waters with varying pH values. The nanoparticles of bismuth vanadate (BiVO4) were produced at various pH levels (9, 10, and 11) using a simple co-precipitation technique. Raman spectra provided additional evidence that the produced nanoparticles were identified as monoclinic single-phase BiVO4 based on the XRD patterns. The optical absorption demonstrated broad absorption in the visible range, with a prominent emission at 520 nm. The effectiveness of the samples and the effect of pH on photodegradation were assessed using RhB dye photocatalytic degradation. Figure 13 displays the percentage of degradation and time-dependent spectrum shift for RhB dye using BiVO4 nanoparticles at pH levels of 9, 10, and 11 (Josephine et al. 2020).

Time-dependent spectral change and percentage degradation of using BiVO4 nanoparticles at pH levels of 9, 10, and 11 for RhB dye (Josephine et al. 2020).

3.5 Influence of temperature

Temperature is a critical factor affecting the photocatalytic breakdown of organic contaminants. It influences the speed of the photocatalytic reaction, the characteristics of the photocatalyst, the interactions between the photocatalyst and contaminants, and the overall effectiveness of the degradation process. Temperature affects mass transfer, ROS dynamics, adsorption–desorption equilibria, photocatalyst characteristics, and reaction kinetics, all crucial to the photocatalytic destruction of organic pollutants. By balancing these variables, ideal temperature ranges can dramatically increase degradation efficiency, but extremes in either direction can have complex and occasionally detrimental consequences. Practical applications often involve temperature control or adaptation to local environmental conditions to maximize photocatalytic effectiveness. This is a thorough examination of the effects of temperature on photocatalytic degradation:

Increasing temperature raises the kinetic energy of molecules, lowering the activation energy barrier for processes. This can be lowered by promoting more successful collisions between reactants and the photocatalyst surface. In a TiO2 photocatalytic system, the phenol degradation rate increased with temperature, indicating that the degradation process requires less activation energy at higher temperatures. Temperature increases led to faster degradation and increased reaction rates. According to the Arrhenius equation, the rate constant, k, for a reaction rises exponentially with temperature. Temperature-dependent increases in the rate constant for photocatalytic dye degradation resulted in more efficient degradation. The adsorption isotherms of pollutants on the surface of the photocatalyst are influenced by temperature, which can impact the availability of pollutants for degradation. Elevated temperatures can decrease the surface concentration of contaminants by reducing adsorption due to desorption. At higher temperatures, organic contaminants such as MB lost some ability to adsorb on TiO2, resulting in a lower surface concentration for photocatalytic destruction. This potential decrease in surface-bound contaminants impacts the degradation rate. Elevated temperatures can enhance the desorption of intermediate products generated during degradation, preventing surface poisoning and encouraging further degradation. Continuous pollutant degradation was possible in ZnO photocatalysis without significant catalyst deactivation due to faster desorption of intermediates at higher temperatures, leading to increased efficiency. The band gap energy of semiconductors can be affected by temperature. Higher temperatures typically cause the band gap to shrink slightly, influencing photoexcitation efficiency. As the temperature increased, TiO2’s band gap marginally shrank, improving photocatalytic activity and photon absorption. The mobility and recombination rates of electron–hole pairs in photocatalysts are influenced by temperature. The advantages of improved reaction kinetics may be offset by higher temperatures, which can increase recombination rates. Elevated temperatures in ZnO resulted in greater electron–hole pair recombination rates, somewhat countering the advantages of higher reaction rates and decreasing overall efficiency. The production rate of hydroxyl radicals in TiO2 photocatalysis increased with temperature, leading to faster degradation of pollutants like atrazine. Higher temperatures can enhance the generation rates of ROS, such as hydroxyl radicals (·OH) and superoxide anions (O2·−), which are crucial for the degradation of organic pollutants. Increased ROS generation results in improved degradation efficiency. However, high temperatures can also impact the stability and lifespan of ROS. Certain ROS may decompose rapidly at elevated temperatures, reducing their ability to degrade contaminants. The potency of hydroxyl radicals diminishes at extremely high temperatures, which can reduce the overall effectiveness of organic molecule breakdown. The effects of elevated temperatures can vary, and efficiency may be decreased by a potential decrease in ROS stability. Warmer temperatures generally lead to faster diffusion of molecules in water, facilitating the surface of the photocatalyst surface and increasing the rate of contact. The breakdown rates of contaminants such as bisphenol A were accelerated in a photocatalytic reactor due to improved diffusion rates at higher temperatures. Elevated temperatures improved degradation efficiency by enhancing mass transfer. In open systems, higher temperatures can increase evaporation rates, concentrating pollutants and potentially increasing their availability for degradation. Larger ambient temperatures in outdoor photocatalytic systems concentrated contaminants, increasing degradation rates due to higher local concentrations. Because of concentration effects, elevated temperatures may enhance degradation rates. Degradation rates slow down at lower temperatures due to reduced reaction kinetics. Pollutants are degraded by photocatalysis at much slower rates in cold water because of slower reaction kinetics and less molecular mobility. Consequently, degradation efficiency was decreased at lower temperatures.

Lower temperatures can increase surface concentration by improving the adsorption of contaminants on the photocatalyst. Slower kinetics may result in somewhat improved degradation rates due to higher local concentrations caused by increased adsorption of organic contaminants on TiO2 at lower temperatures. This complex impact might lead to a local increase in pollutant concentration but a slower overall degradation rate. An ideal temperature range exists when reaction kinetics are sufficiently high without causing significant desorption or recombination losses. For TiO2 photocatalysis, the ideal temperature was found to be 35 °C, as it provided the optimum reaction rate and adsorption, resulting in the highest degradation efficiency of pollutants like dyes. The equilibrium between ROS generation and stability occurs within this range, enhancing overall degradation efficiency. In a ZnO system, moderate temperatures were optimal for ROS formation and stability, allowing for the effective degradation of pollutants such as pharmaceuticals (Hwang et al. 2022).

Because ROS dynamics are balanced at high temperatures, degradation efficiency is enhanced. However, extremely high temperatures can introduce challenges such as recombination and desorption, in addition to increasing reaction speeds. Reaction rates may rise alongside electron–hole pair recombination rates above 50 °C, decreasing net efficiency. While higher reaction rates are beneficial, they may also be offset by increased recombination and desorption. High temperatures can negatively impact degradation efficiency due to significant increases in contaminant desorption and decreased ROS stability. Elevated temperatures led to removing contaminants from TiO2 and reduced the stability of hydroxyl radicals, thereby lowering overall degradation efficiency. The combined effects of degradation. Desorption and reduced ROS stability result in decreased efficiency. Maintaining temperature within an ideal range can enhance degradation efficiency in photocatalytic reactors. Reactors with controlled temperatures demonstrated higher degradation rates for organic contaminants such as pesticides than systems with temperature fluctuations.

3.6 Influence of irradiation type and intensity