Abstract

This review explores the potential of gravity-driven ultrafiltration (GDU) systems as a sustainable solution to global drinking water challenges. Leveraging hydrostatic pressure instead of external energy inputs, GDU systems offer a low-maintenance, cost-effective approach well-suited for decentralized and resource-constrained settings. The paper provides a detailed analysis of the fluid dynamics and transport mechanisms that underpin GDU operation, emphasizing the influence of biofilm formation, membrane morphology, and material selectivity on system performance. Recent advancements in membrane materials have demonstrated significant improvements in antifouling performance, flux stability, and contaminant removal. Innovative membrane designs are also reviewed for their potential to enhance adaptability and multifunctionality. Real-world case studies highlight the operational feasibility and economic advantages of GDU systems, while identifying key barriers such as long-term reliability, feedwater variability, and limited community-based monitoring capacity. Socio-economic considerations, including modular design strategies and institutional engagement, are examined to support scalable implementation. This comprehensive review offers interdisciplinary insights to inform future research, technology development, and policy planning aimed at advancing sustainable water purification solutions worldwide.

1 Introduction

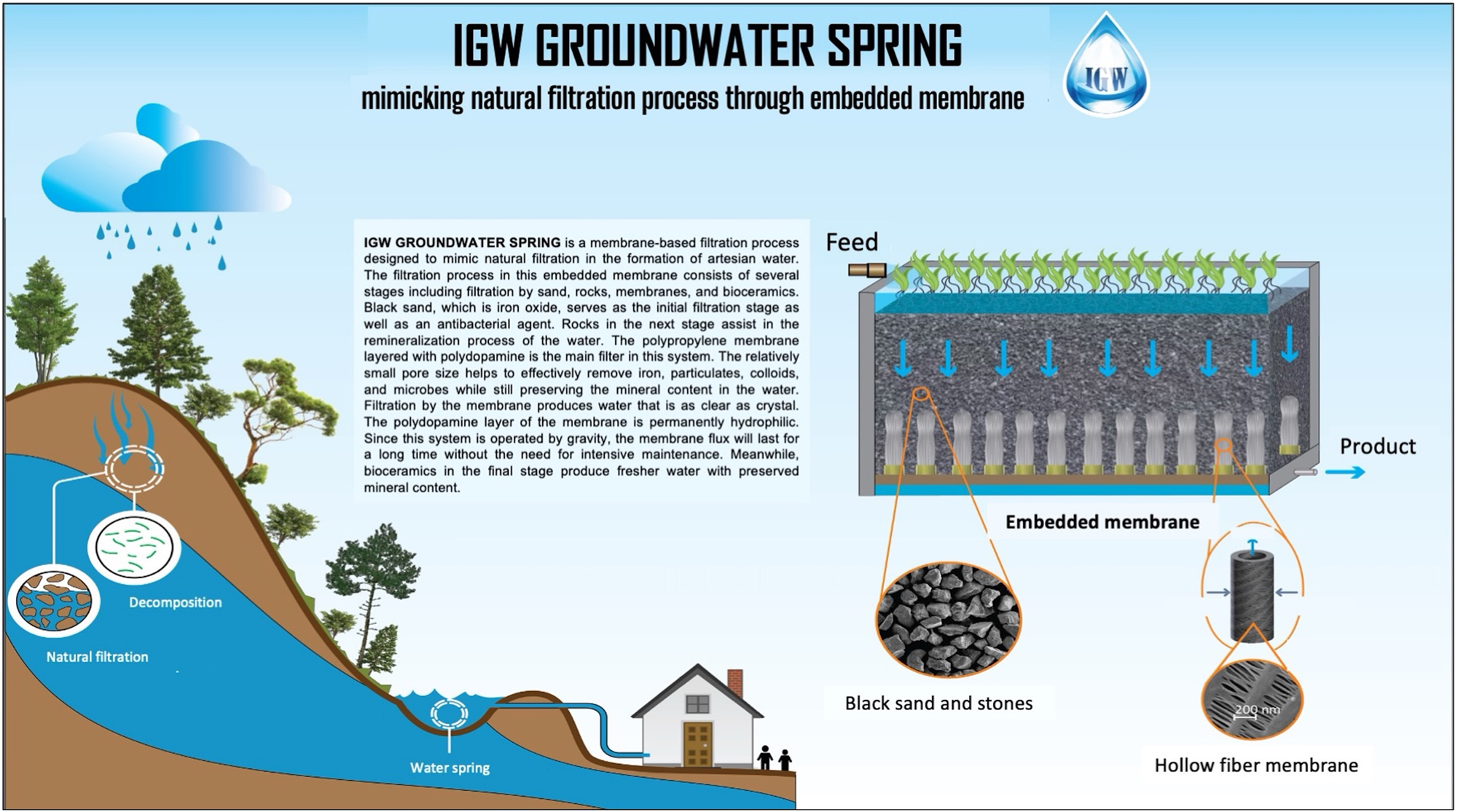

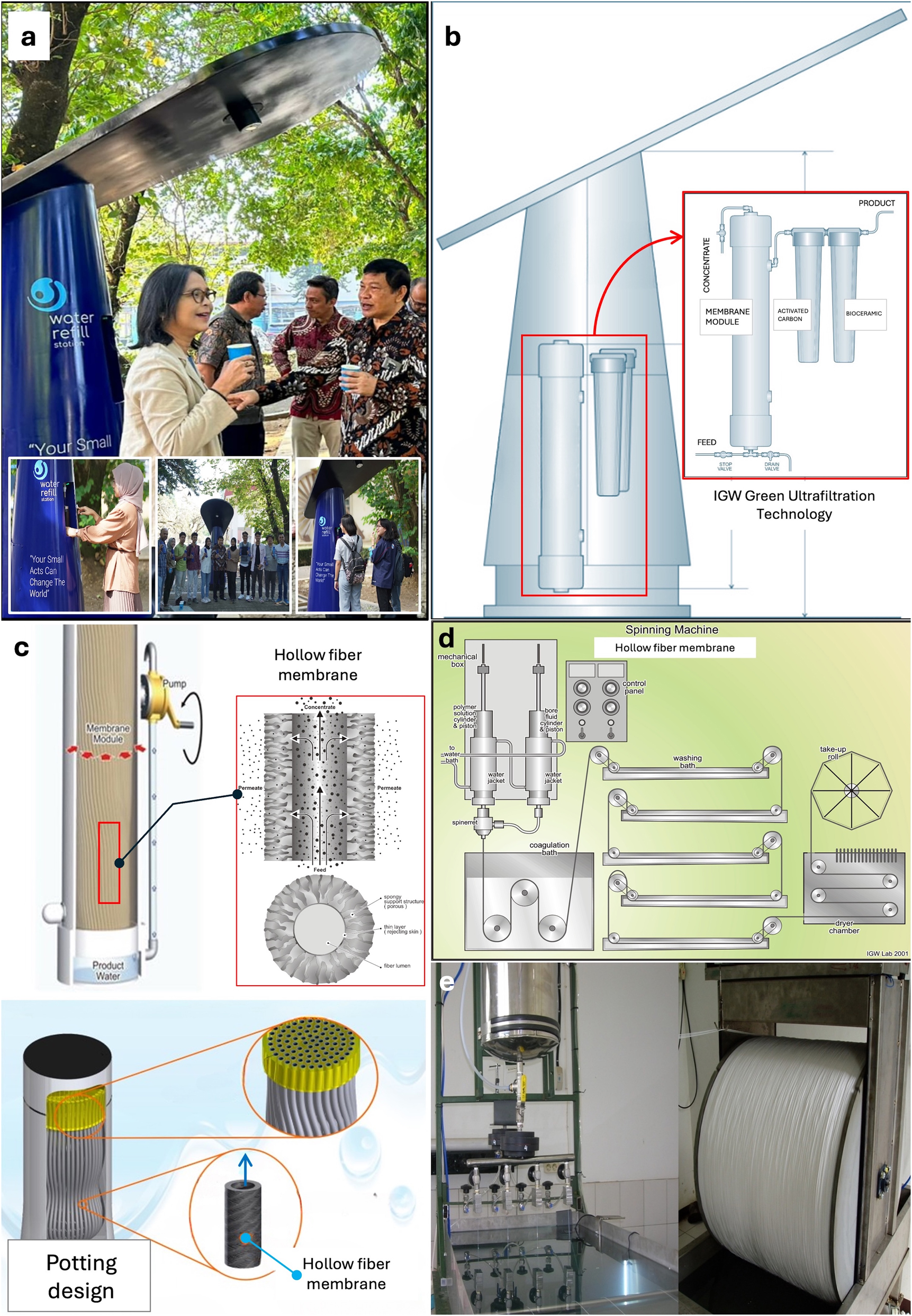

Access to clean and safe drinking water remains a pressing global challenge (Jayawardena 2021). According to the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations (UN), billions of people globally face water scarcity and contamination, posing severe health risks, hindering socio-economic development, and threatening environmental sustainability. While conventional water treatment technologies are effective, their high energy demands and infrastructure requirements often render them impractical in resource-limited settings. Ultrafiltration has emerged as a compelling alternative due to its ability to remove pathogens and contaminants at the molecular level while maintaining high flow rates. In particular, gravity-driven membrane (GDM) or gravity-driven ultrafiltration (GDU) systems offer an energy-efficient, low-maintenance solution well-suited for decentralized and off-grid applications. By utilizing gravity rather than external pressure to drive filtration, GDU systems significantly reduce energy consumption and operational complexity. Their design promotes biofilm formation on the membrane surface, which stabilizes flux and enhances long-term performance, making them especially viable for sustainable drinking water provision in remote areas (Derlon et al. 2014).

Moreover, GDU systems offer a practical solution for treating nutrient-rich water bodies prone to cyanobacterial blooms, a challenge increasingly intensified by climate change. Blooms dominated by Microcystis aeruginosa produce hepatotoxins associated with liver cancer and are often inadequately addressed by conventional treatment methods. GDU provides an affordable, electricity-free alternative capable of effectively removing pathogens and suspended solids. Notably, biofilms formed on GDU membranes have demonstrated the ability to degrade cyanotoxins, further improving water quality and system efficacy (Kohler et al. 2014).

The effectiveness of GDM systems is well-documented across a range of environmental conditions. Biofilm formation – a hallmark of GDU operation – plays a key role in stabilizing water flux by modulating hydraulic resistance (Desmond et al. 2018b). To further improve performance and manage biofilm-related fouling, techniques such as the pre-deposition of porous materials onto membranes have been explored, although issues like particle clogging persist (Song et al. 2020). The inherent adaptability, low operational cost, and energy independence of GDU systems position them as an ideal solution for small-scale, decentralized water treatment. Their successful implementation in diverse settings, from Europe to Africa, underscores their potential to support global water safety objectives (Boulestreau et al. 2012).

However, the detrimental effects of particle clogging and biofilm formation on ultrafiltration performance remain significant. Particle clogging – caused by the accumulation of solutes and colloidal matter – leads to decreased permeate flux and elevated transmembrane pressure, thereby undermining operational efficiency (Dmitrenko et al. 2021; Li et al. 2019). Additionally, the sieving effect and subsequent cake layer formation intensify membrane fouling, further reducing filtration capacity and increasing maintenance demands (Álvarez-Arroyo et al. 2023; Scutariu et al. 2020).

Biofilm formation, while stabilizing hydraulic resistance, poses challenges for membrane durability and filtration efficiency. The extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) produced by biofilms increase resistance to water flow, causing a decline in permeate flux over time (Javier et al. 2022). Additionally, biofilm growth can alter the surface properties of membranes, leading to mechanical degradation and reduced lifespan (Pu et al. 2022). Operational strategies, such as optimizing hydraulic conditions and incorporating antifouling surface modifications, are critical to mitigating these effects (Aronu et al. 2019; Beril Melbiah et al. 2019).

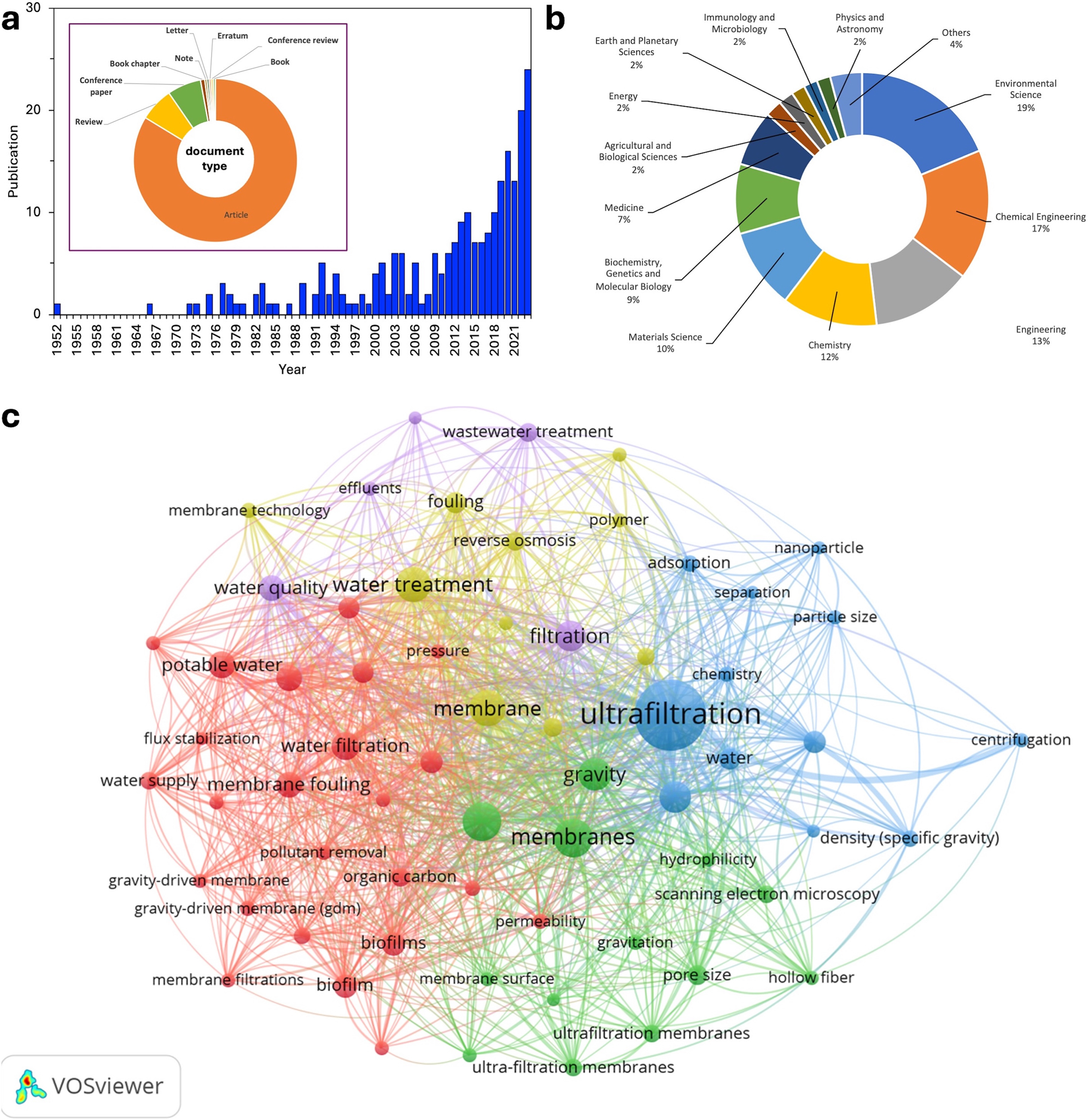

The historical development of GDU research underscores its rising importance, fueled by advances in membrane technology and the global demand for sustainable water treatment solutions. Since the first publication in 1952, the field has experienced steady growth, with a marked acceleration from the mid-1990s and a notable peak of 24 publications in 2023 (Figure 1a). This surge reflects both a deepening understanding of gravity-driven systems and an alignment with global priorities for energy-efficient, environmentally sustainable purification technologies. The increasing research momentum is largely driven by the escalating global water crisis and the pressing need for innovative, accessible treatment approaches, positioning GDU as a critical focus in water research. GDU research is inherently interdisciplinary. Environmental science (19 %) and chemical engineering (17 %) dominate, highlighting the field’s relevance to water treatment and process design (Figure 1b). Engineering and chemistry collectively contribute 25 %, reflecting the technical innovation driving the field, while materials science (10 %) and biochemistry (9 %) focus on novel filtration materials and bio-interfacial dynamics. Beyond water treatment, GDU applications extend to medical, energy, and geosciences, underscoring its broad impact. The research landscape, illustrated in Figure 1c, reveals four key thematic clusters: the red cluster centers on “water treatment” and “membrane fouling”; the blue cluster emphasizes “hydrophilicity” and “pore size”; the yellow cluster highlights material innovation; and the green cluster focuses on “organic carbon” and “pollutant removal.” These interconnected themes demonstrate the collaborative, evolving nature of GDU research.

Bibliographic analysis on publications related to gravity driven ultrafiltration. (a) Annual publication: (b) publication by subject; (c) keyword network generated by VOSviewer. Data source: scopus; queries: TITL-ABS-KEY; date: 19 February 2024.

Ultrafiltration research encompasses a wide range of applications aimed at addressing global water challenges. Studies have investigated adsorptive ultrafiltration membranes for the removal of heavy metals and organic compounds, with a focus on mitigating fouling (Yu et al. 2022). Reviews on oily wastewater treatment emphasize membrane synthesis techniques and separation efficiencies, while also identifying fouling and material durability as ongoing limitations (Baig et al. 2022). Emerging hybrid approaches, such as magnetic ion exchange coupled with ultrafiltration, show potential for estrogen removal, though issues with retention efficiency remain (Imbrogno et al. 2017). Maggay et al. (2021) highlighted the importance of high porosity and controlled pore size in functionalized porous media for effective oil–water separation, and Pronk et al. (2019) underscored the advantages of GDM systems, particularly in terms of flux stabilization and low energy consumption for decentralized applications. This review presents a novel perspective by focusing on GDU as a sustainable solution to the global water crisis. In contrast to previous studies centered on specific technologies, it integrates theoretical insights and molecular-level interactions to advance membrane selectivity and permeability. The review evaluates recent innovations in materials and design strategies aimed at reducing fouling and extending membrane lifespan, while also assessing the economic and environmental advantages of GDU systems in resource-constrained environments. By offering a comprehensive analysis, this review seeks to inform and guide future research directions, underscoring the critical role of GDU in advancing global water security.

2 Fluid dynamics in gravity-driven systems

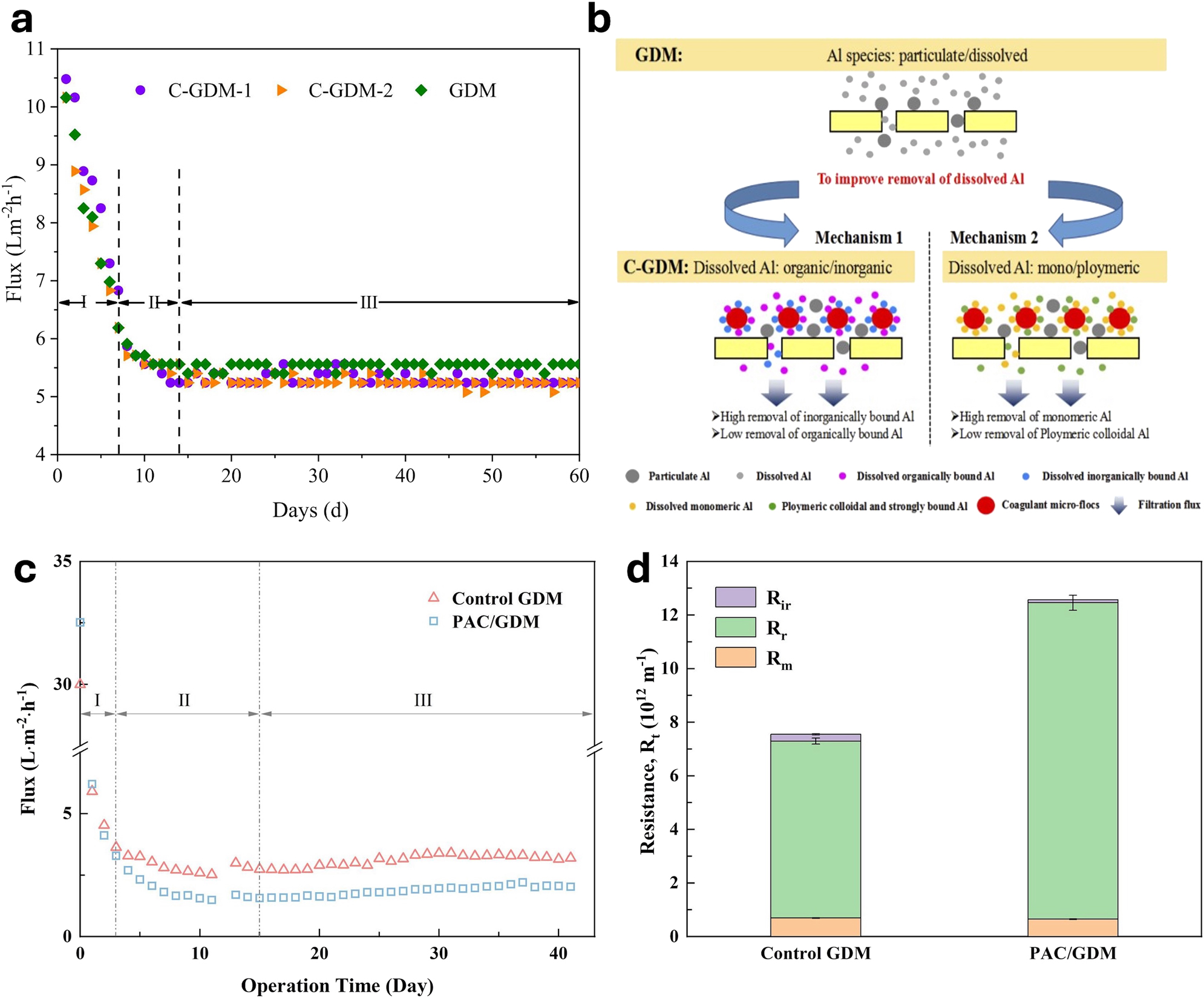

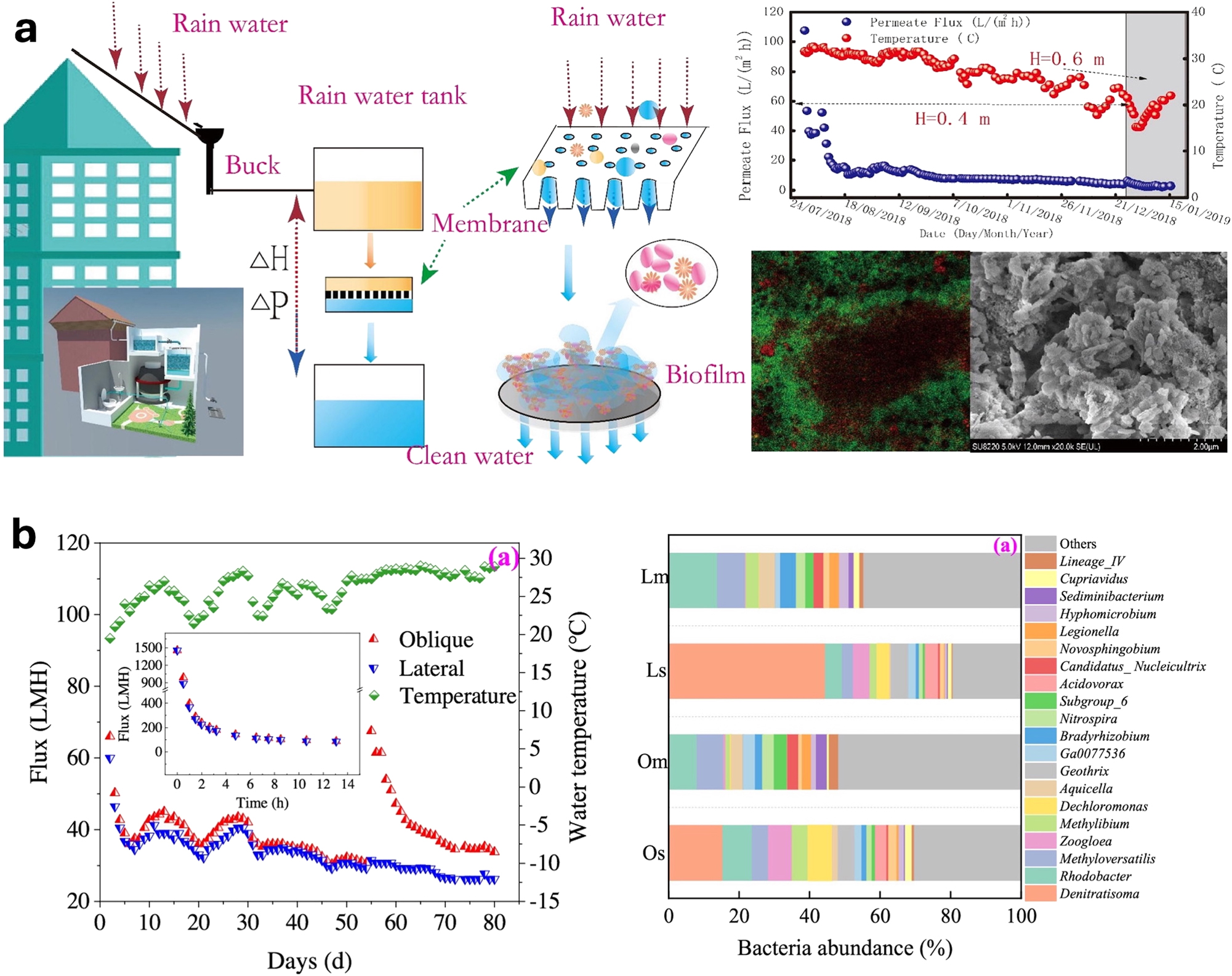

GDU systems operate based on fundamental principles of fluid dynamics, where gravity serves as the driving force for filtration, eliminating the need for external energy inputs. A comprehensive understanding of fluid behavior – including flow regimes, pressure gradients, and fluid properties – is essential for optimizing system efficiency. Pilot-scale studies, such as those by Yue et al. (2021), have demonstrated the operational viability of micro-flocculation/GDM (C-GDM) systems over extended periods without backwashing (Figure 2a and b). Their findings show a flux decline from over 10 to ∼5.3 L m−2 h−1 within six days, stabilizing thereafter under 70 mbar pressure. Notably, polyferric sulfate (PFS) outperformed FeCl3 as a coagulant, achieving over 75 % total aluminum removal and meeting WHO water quality standards. However, the application of FeCl3 may increase total dissolved solids and iron levels, requiring post-treatment. Moreover, relatively low flux rates in the current setup limit its applicability for high-demand scenarios, highlighting the need for further optimization of coagulant dosing and membrane performance.

Flux profile of GDU. (a) Flux trends in C-GDM-1 (using FeCl3 as a coagulant), C-GDM-2 (using PFS as a coagulant), and a GDM system without any coagulant, all operating at a pressure of 70 mbar; reproduced from (Yue et al. 2021) with permission from Elsevier. (b) Mechanism of Al removal by GDM and by micro-flocculation-based C-GDM; reproduced from (Yue et al. 2021) with permission from Elsevier. (c) Flux and (d) membrane resistance during filtration in the standard GDM and PAC/GDM systems; reproduced from (Huang et al. 2023) with permission from Elsevier.

Fluid dynamics within GDU systems critically influence membrane performance, fouling behavior, and water flux. These systems utilize gravitational pressure to drive water through membranes, making fluid flow characteristics essential for optimizing efficiency without external energy inputs. Studies employing computational fluid dynamics and optical coherence tomography have revealed that hydrodynamic conditions within the dual-layer system – comprising the biofilm and membrane – significantly impact mass transfer and fouling dynamics. For instance, flow simulations in systems incorporating pre-deposited powdered activated carbon-manganese oxide (PAC-MnOx) layers demonstrate that biofilm integrity and flow uniformity affect manganese removal and membrane resistance (Wang et al. 2024). Porous biofilms modulate shear stress and solute transport, influencing pollutant degradation efficiency. Furthermore, the inclusion of open slot modules enhances internal flushing by maintaining flow velocities that prevent contaminant buildup in dead zones, thereby sustaining permeability and reducing fouling (Lee et al. 2024). These insights underscore the necessity of tailoring fluid dynamics through structural and operational design to optimize GDM ultrafiltration performance in diverse water treatment scenarios.

Biofilm development plays a central role in GDU operation, influencing flux stabilization and fouling resistance. Derlon et al. (2022) reported that while shear frequency alters the initial cohesion and elasticity of biofilms, the final stabilized flux converges across conditions to 12–15 L m−2 h−1, with hydraulic resistances ranging from 2.1 × 1012 to 2.4 × 1012 m−1. These findings suggest that biofilms adapt to hydraulic conditions, limiting the feasibility of engineering membranes with custom permeability profiles. Nonetheless, uncontrolled biofilm growth can impair membrane throughput, increase fouling resistance, and damage membrane integrity through bacterial activity. Strategies such as enhanced cleaning, antifouling surface modifications, and incorporation of antimicrobial agents are vital for mitigating these effects.

Transmembrane pressure is another key parameter influencing GDM performance. Increasing pressure from 50 to 150 mbar has been shown to enhance normalized permeability and reduce overall membrane resistance, thereby improving filtration efficiency (Wu et al. 2024). Additionally, the integration of powdered activated carbon (PAC) contributes to the removal of dissolved organic matter and modulates biofilm structure, leading to decreased hydraulic resistance (Huang et al. 2023). Figure 2c and d demonstrate how PAC simultaneously mitigates and aggravates fouling by altering cake layer resistance and promoting cleaner membrane pores via adsorption of small molecules.

Advanced monitoring techniques offer valuable insights into membrane behavior and fouling dynamics. In-situ tools such as optical coherence tomography (OCT) and confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) provide high-resolution visualization of biofilm development. For instance, OCT measurements revealed biofilm thicknesses reaching 150 µm, correlating with increased hydraulic resistance and decreased flux (Derlon et al. 2022). Complementary molecular-level analyses using Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) have identified protein and polysaccharide signatures within fouling layers, confirming their organic composition and elucidating interactions between foulants and membrane surfaces (Huang et al. 2023).

3 Transport mechanisms in ultrafiltration

Ultrafiltration membranes function through a variety of interconnected transport mechanisms that regulate the movement of solvents and solutes across the membrane. Additionally, the morphology of the membrane significantly influences these transport processes.

3.1 Solvent and solute transport

Convective transport is a key mechanism in ultrafiltration, driven by the pressure differential across the membrane. Both the solvent flux (J v ) and solute flux (J s ) through the membrane are described using a phenomenological transport model, represented by the following equations (Park and Cho 2008):

Here, L p denotes pure water permeability, Δπ is the osmotic pressure, ΔP shows trans-membrane pressure, σ represents the reflection coefficient (selectivity), and P m refers to solute diffusive permeability. In Equation (2), C m , and C p represent the concentration at the membrane surface and the permeate concentration, respectively, while C* is the logarithmic mean difference of C m and C p .

In gravity-driven systems, this pressure differential (ΔP) is primarily generated by gravitational forces instead of external pressure provided by a pump, facilitating the movement of the solvent through membrane pores. This process is particularly important for the transfer of larger molecules or particles, and its efficiency is strongly influenced by membrane properties and operational parameters, such as flow rate and the composition of the feed solution. For instance, a study employing a two-dimensional model effectively predicted permeate fluxes, quantitatively demonstrating the significant impact of variables such as feed velocity and initial solute concentration (Paris et al. 2002).

In contrast, diffusion plays a complementary role in ultrafiltration, particularly for smaller solute molecules. This mechanism involves the migration of solutes from regions of higher concentration to lower concentration across the membrane, driven by the concentration gradient. Quantitative findings show that the diffusivity of natural organic matter decreases with the membrane’s molecular weight cutoff (MWCO), underscoring the importance of the sieving effect in controlling diffusive transport (Park and Cho 2008).

Osmotic pressure (Δπ), arising from solute concentration differences across the membrane, imposes a significant limitation on solvent transport in ultrafiltration systems. In gravity-driven configurations, the osmotic pressure often counteracts the driving force provided by hydrostatic pressure, making such systems impractical for high-solute concentrations. A detailed model incorporating electrostatic interactions and steric hindrance (Menon and Zydney 1999) highlights the challenges posed by osmotic pressure in ultrafiltration, highlighting the need for additional driving forces, such as applied pressure, to overcome this limitation.

The transport of solutes and the mechanisms underlying fouling in ultrafiltration systems involve a complex interplay of physical, chemical, and biological interactions. Classical and extended interaction theories, combined with molecular-level modeling approaches, offer critical insights into these processes. The Derjaguin–Landau–Verwey–Overbeek (DLVO) theory provides a foundational framework for understanding colloidal stability and particle-membrane interactions by quantifying the total interaction energy (Vtotal) as the sum of attractive van der Waals forces (Vtotal) and repulsive electrostatic double-layer forces (Vᴇᴅʟ). Elevated ionic strength compresses the electrostatic double layer, thereby reducing Vᴇᴅʟ and enhancing particle adhesion and fouling (Henry et al. 2011; Hupka et al. 2010). In contrast, lower ionic strength increases electrostatic repulsion, mitigating fouling potential (Kumar and Biswas 2010).

The extended DLVO (XDLVO) theory expands upon this by incorporating acid-base interactions (Vᴬᴮ), accounting for hydrophilic and hydrophobic effects. This extension enables a more comprehensive evaluation of fouling behavior. For example, XDLVO analyses have shown that hydrophilic surface modifications increase repulsive interactions, thereby reducing the membrane’s fouling tendency (Ma et al. 2021; Sun et al. 2023). Additionally, operational variables such as pH and ionic strength can modulate Vtotal, offering practical strategies for fouling control.

At the molecular scale, density functional theory (DFT) provides a powerful computational approach for modeling membrane–solute interactions through calculations of electronic structures and interaction potentials. The Kohn–Sham formulation of DFT is particularly effective for determining binding energies and electrostatic interactions, which are essential for elucidating adsorption mechanisms (Huang and Carter 2011). Classical DFT (cDFT) has been employed to examine solute concentration effects on transport phenomena, informing the development of more effective fouling and cleaning strategies (Ramos and Pavanello 2016). Furthermore, advancements in embedding theories enhance the ability to analyze localized interactions, reinforcing DFT’s value in optimizing ultrafiltration membrane performance (Manby et al. 2012).

3.2 Membrane properties and transport mechanisms

The performance of ultrafiltration is largely determined by their physical and chemical properties, such as pore size distribution, surface charge, and hydrophobicity/hydrophilicity of the membrane. Quantitative analysis in (Nguyen and Neel 1983) evaluates how modifications by polyelectrolytes can improve rejection capabilities and diffusion permeability, showing how membrane characteristics can be tuned to enhance separation processes.

Figure 3a and b illustrate the diverse mechanisms governing mass transport through membranes, spanning dense polymers and porous structures, and their application in both gas and liquid separations. In dense membranes, transport is primarily described by the solution-diffusion model, wherein solutes dissolve into the membrane matrix and diffuse across it. This process is governed by the solute’s physicochemical interactions with the membrane material as well as the structural attributes of the solute itself.

Transport mechanims in membrane. (a) Membrane transport mechanisms by length scales. The diagram on the bottom left shows the relative sizes of gas and water molecules, hydrated ions, and the average free path of gas molecules. Key factors such as Q for flux, D for diffusivity, S for the sorption coefficient, m for molecular mass, and μ for viscosity are included; reproduced from (Wang et al. 2017) with permission from Springer Nature. (b) Mechanisms of mass transport in water separation, illustrated across an expanding length scale (from left to right); reproduced from (Lim et al. 2022) with permission from Royal Society of Chemistry.

In contrast, porous membranes rely on molecular sieving as the principal separation mechanism. As shown in Figure 3a; (Wang et al. 2017), nano-sized pores selectively permit smaller molecules to pass while rejecting larger species. For gas transport, the dominant mechanism is pore-size dependent: Knudsen diffusion governs transport in sub-micron pores, favoring lighter gases with higher kinetic energy, whereas Poiseuille (viscous) flow dominates in micron-scale pores, allowing bulk flow without molecular selectivity.

Figure 3b further illustrates how nanoconfinement alters mass transport behavior, deviating from classical fluid dynamics. At sub-micron scales, hydrodynamic filtration enables size-based exclusion of solutes. As pore diameters approach the nanometer and sub-nanometer range, molecular sieving becomes increasingly dominant, often modulated by interfacial phenomena. These include electrostatic interactions such as the Donnan exclusion effect, where charged membrane surfaces repel ions of like charge, enhancing selectivity.

At the ångström scale, transport is predominantly governed by the solution-diffusion mechanism, in which solute partitioning into and diffusion through the membrane material dictate permeation. This multi-scale framework underscores the intricate interplay between membrane morphology, pore size, and surface chemistry in controlling selective separation performance across a broad range of applications.

4 Membrane selectivity: molecular and nano-scale perspectives

The selectivity and performance of ultrafiltration membranes are primarily determined by their structural characteristics, which encompass material composition, pore morphology, and stability under operational conditions. A comprehensive understanding of how these factors influence membrane behavior is crucial for optimizing filtration efficiency.

4.1 Structural design

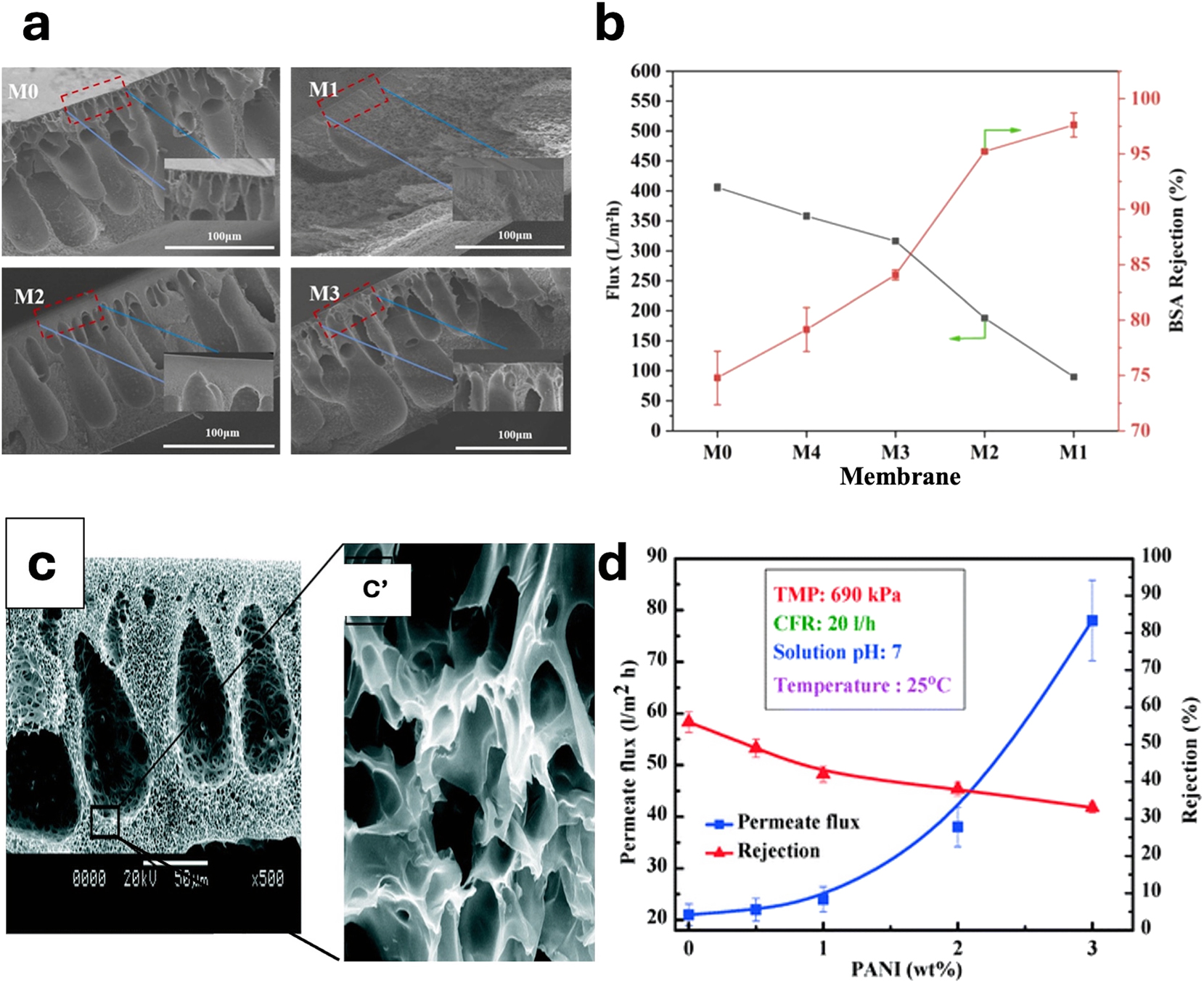

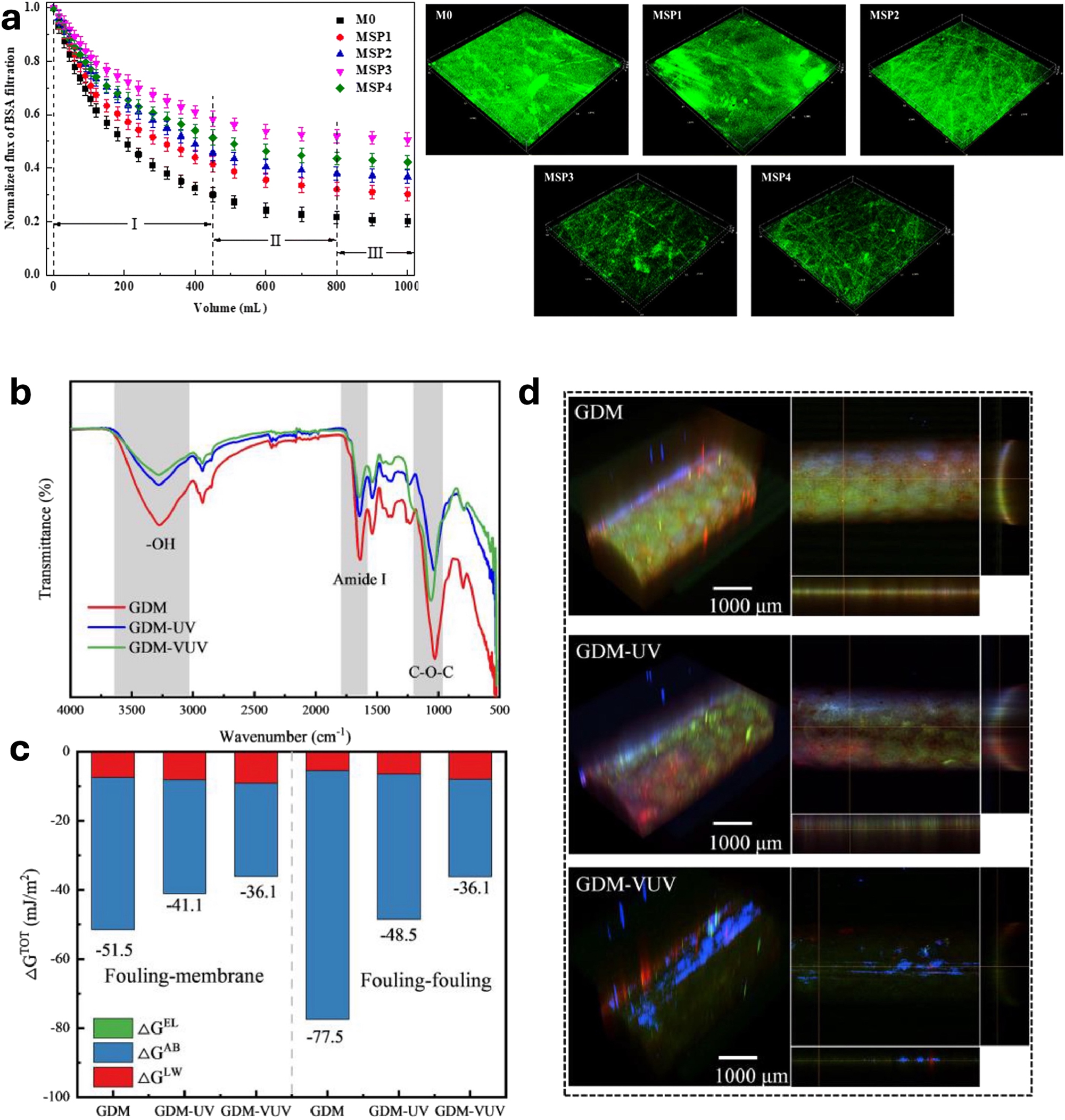

The physical structure of ultrafiltration membranes, particularly their pore architecture and material composition, is critical in determining transport properties and separation efficiency. Numerous studies have shown that solvent composition and fabrication techniques significantly influence membrane morphology. For instance, cellulose acetate (CA) ultrafiltration membranes, fabricated by varying the ratio of N,N-dimethylacetamide (DMAc) to methyl acetate (MAC) (Lin et al. 2023), demonstrated significant enhancements in performance. Specifically, membranes with an optimized solvent ratio achieved a pure water flux of 188.0 L/m² h and a bovine serum albumin (BSA) rejection ratio of 95.2 %, indicating an approximate 20 % improvement over the control (Lin et al. 2023). Figure 4a illustrates the cross-sectional topography of CA membranes fabricated with varying solvent ratios (Lin et al. 2023). Variations in the solvent mixture result in distinct membrane structures, which in turn affect permeate flux and BSA rejection (Figure 4b). The M0 membrane, characterized by its sponge-like structure, exhibited the highest BSA rejection.

Membrane morphologies and performances. (a) Cross section of the membranes with different solvent ratios. (b) Pure water flux and BSA rejection; reproduced from (Lin et al. 2023) with permission from Elsevier. (c) SEM image of membrane with PANI particles (2 %-wt). (d) Effect of PANI concentration on flux and rejection of UF membrane; reproduced from (Mukherjee et al. 2015) with permission from RSC Publications.

Further investigation into the influence of membrane structure on performance is presented in a study of cellulose acetate–silica asymmetric membranes (Cunha et al. 2022). This research utilized advanced NMR techniques to correlate the confinement effects of the porous matrix with water dynamics. The findings revealed that smaller pore sizes in the less permeable membranes induced a significant orientational order among the water molecules. This molecular ordering influenced the ultrafiltration permeation characteristics, indicating how structural features at the nano-scale can impact macro-scale performance (Cunha et al. 2022).

Material innovation is essential for improving membrane functionality. For example, ceramic ultrafiltration membranes produced through a co-sintering process exhibited a mean pore size of approximately 5 nm and a water permeance of 72 L/m2h bar (Zou et al. 2022). These membranes demonstrated the ability to reject nearly 99 % of dyes while allowing over 99 % of salts to pass through. This highlights the effectiveness of gradient pore structures in optimizing membrane performance (Zou et al. 2022).

4.2 Enhancing membrane selectivity through material innovations

Membrane selectivity is influenced by pore size distribution, surface charge, and solute-membrane interactions. Although smaller pore sizes improve rejection efficiency through size exclusion, they also increase resistance to flow. To mitigate this trade-off, researchers have investigated advanced nanocomposite materials and various surface modifications (Wang et al. 2018). Research has investigated various strategies to improve membrane selectivity while ensuring sufficient permeability. For example, the development of nanocomposite membranes with novel additives, such as MXene-MOF nanolaminates, has been investigated to enhance pollutant filtration performance and address the challenge of balancing permeability and selectivity (Zhang et al. 2023).

Another strategy for enhancing ultrafiltration membrane efficiency involves modifying surface chemistry through electrostatic interactions. Research has demonstrated that negatively charged membranes improve salt rejection by repelling anions, thereby increasing selectivity. A notable example is the study reported in (Mukherjee et al. 2015), which incorporated polyanilinei (PANI) nanoparticles into polysulfone (PSF) membranes to enhance both performance and selectivity. The incorporation of polyaniline (PANI) nanoparticles resulted in a threefold enhancement in permeability, increasing from 8 × 10−12 to 16 × 10−12 m3 m−2 Pa−1 s−1, while concurrently elevating porosity from 20 % to 64 %. As depicted in Figure 4c, the structural modifications induced by the incorporation of PANI nanoparticles facilitated pore expansion, acting as a porogen and leading to an increase in membrane density. These alterations significantly enhanced the hydrophilicity of the membranes, as evidenced by a reduction in the surface contact angle from 82° to 69°. Furthermore, zeta potential analysis revealed that the negative surface charge of the PANI-modified membranes increased from −4 mV to −28 mV at pH 7, which contributed to improved ion rejection capabilities. Figure 4d illustrates the effect of varying PANI concentrations on both flux and sodium sulfate (Na2SO4) rejection. While the increase in PANI content from 0 wt% to 3 wt% enhanced permeability, it also resulted in a gradual decline in salt rejection, highlighting the trade-off between convective transport and electrostatic exclusion.

Overall, these studies underscore the critical importance of the structural characteristics of ultrafiltration membranes, which range from the molecular to the macro-scale, in influencing their performance. Recent advancements in material science and membrane technology have effectively leveraged these structural features to achieve substantial improvements in filtration efficiency. Such innovations are vital for facilitating the wider adoption of ultrafiltration technology across a variety of applications and industries.

5 The role of membrane morphology and surface chemistry

The performance of ultrafiltration membranes in gravity-driven membrane (GDM) systems is governed by membrane morphology and surface chemistry. These characteristics determine key functional outcomes including fouling resistance, flux stability, and contaminant rejection. Recent advances in material synthesis and modification strategies have enabled the development of membranes with enhanced operational robustness for passive filtration applications.

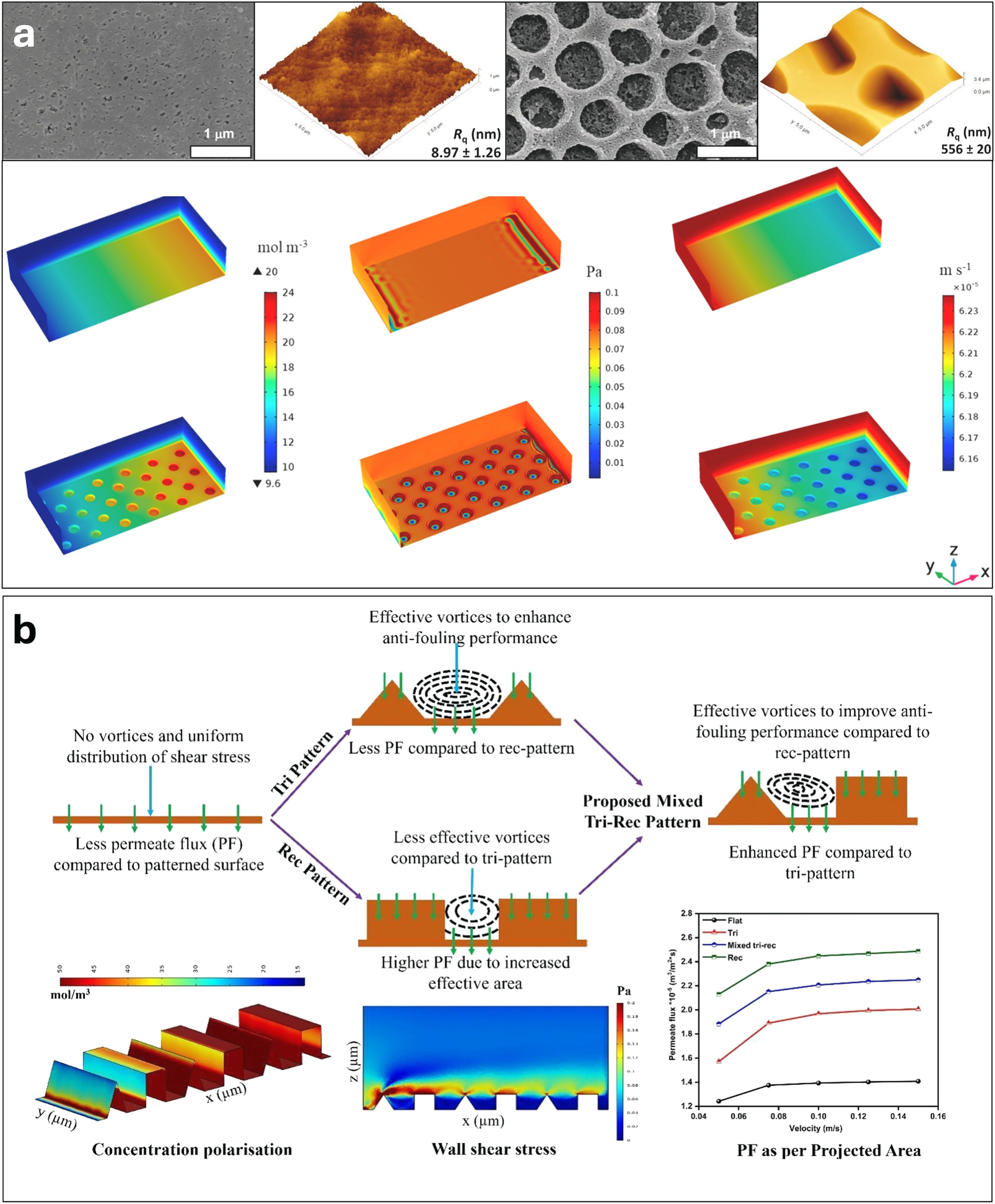

Membrane morphology, defined by pore size, distribution, and porosity, directly influences hydraulic resistance and solute transport. High porosity reduces resistance to flow and increases flux, while narrow pore size distributions improve selectivity and reduce fouling susceptibility. Zhang et al. reported that membranes with controlled pore architectures demonstrated improved permeability and rejection compared to those with heterogeneous structures (Zhang et al. 2016).

Emerging fabrication methods offer improved control over membrane structure. Lin et al. achieved enhanced rejection and antifouling properties in cellulose acetate membranes by adjusting solvent composition during casting (Lin et al. 2023). Incorporation of nanomaterials, including graphene oxide (GO) and metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), has been shown to improve flux and fouling resistance in hybrid membranes, particularly under high fouling loads (Yan et al. 2022).

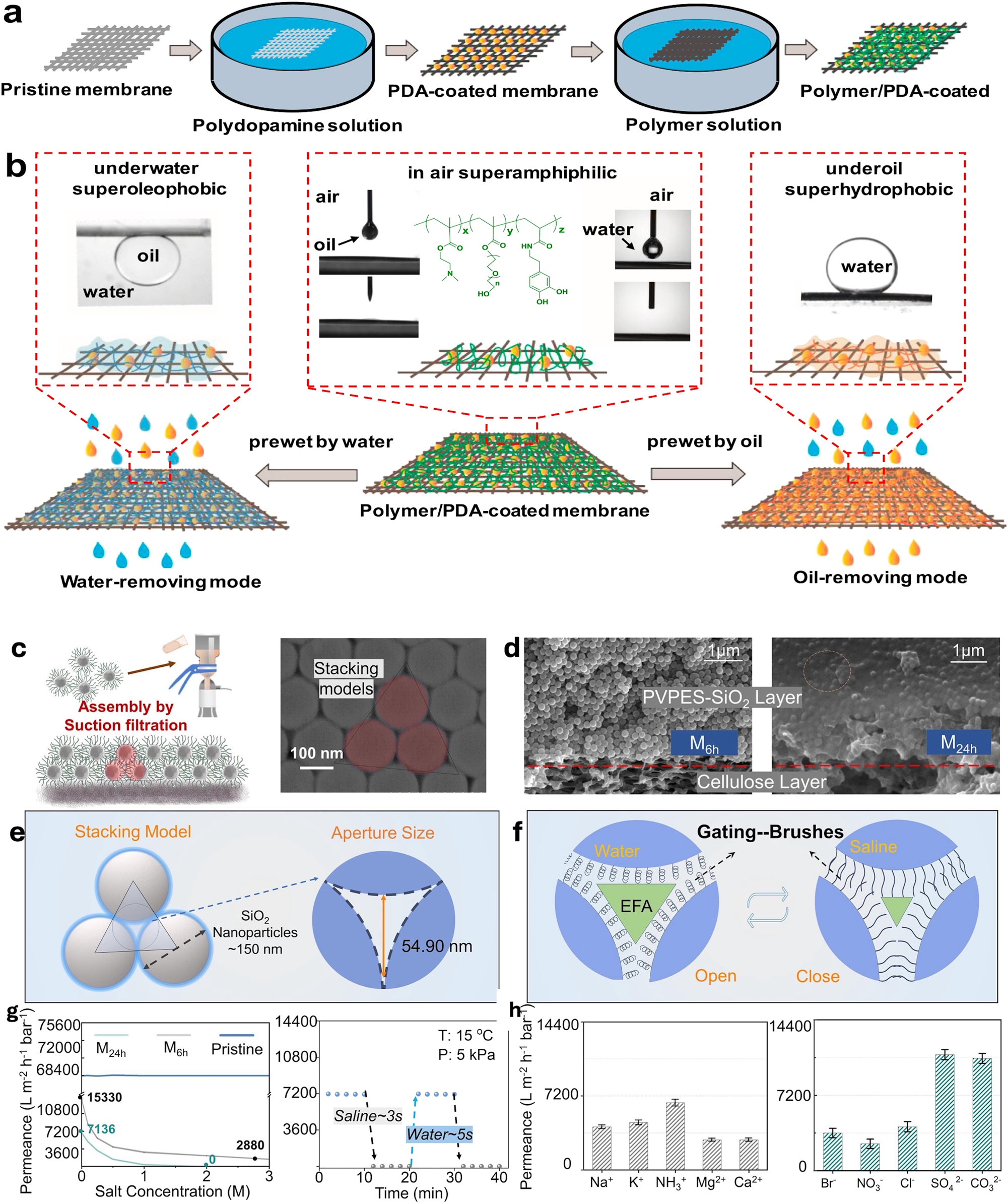

Surface chemistry modulates interactions at the membrane–solution interface. Enhanced hydrophilicity reduces fouling by promoting hydration layer formation, which acts as a barrier to foulant adhesion. Tong et al. showed that surface hydrophilization altered foulant accumulation dynamics (Tong et al. 2021). Functional coatings such as GO or polyelectrolytes increase hydration and repel hydrophobic contaminants (Plisko et al. 2023; Yan et al. 2022).

Nanoparticle functionalization further augments surface properties. TiO2 nanoparticles enhance hydrophilicity and impart antimicrobial activity (Razmjou et al. 2011). Under UV irradiation, TiO2 promotes in-situ degradation of organic foulants, extending membrane lifespan (Rahimpour et al. 2008). Other strategies, such as polydopamine or hydrous manganese dioxide functionalization, improve fouling resistance and flux recovery (Vetrivel et al. 2019).

Flux stability correlates with hydrophilicity and structural integrity. Al-Shaeli et al. demonstrated that polysulfone membranes modified with hydroxyl additives maintained 97 % flux recovery over extended operation (Al-Shaeli et al. 2021). Ceramic membranes, due to their mechanical durability, offer long-term flux stability and chemical resistance (Meng et al. 2019).

Contaminant rejection is essential for water quality. Membranes incorporating TiO2 or zeolite reject >95 % of bovine serum albumin and maintain high flux (Asadollahi et al. 2020). Hybrid membranes with carbon nanotubes and TiO2 exhibit superior antifouling and rejection performance relative to conventional polymers (Dmitrenko et al. 2021).

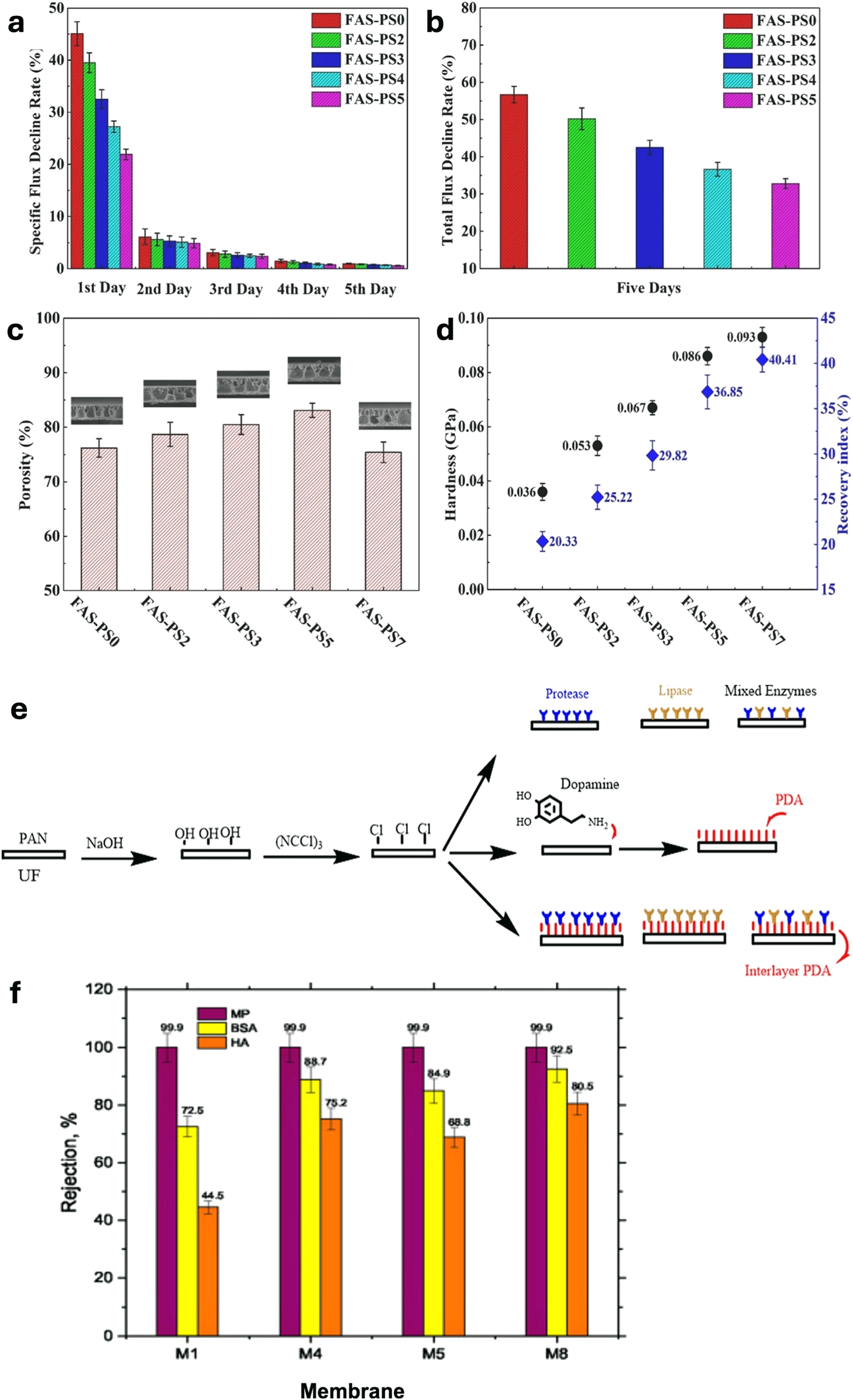

Jiang et al. developed PVDF membranes modified with four-arm star polystyrene microspheres (Figure 5a–d), achieving a fivefold increase in flux and reduced fouling (Jiang et al. 2022). Asadi et al. introduced a membrane functionalized with dopamine, protease, and lipase (Asadi et al. 2023). This enzyme-functionalized membrane showed improved surface hydrophilicity and charge repulsion, yielding high removal rates for bovine serum albumin (92.5 %), milk powder (99.9 %), and humic acid (80.5 %) (Figure 5e–f). The membrane also exhibited antibacterial activity against Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus, supporting enhanced biofouling resistance.

Modified UF membranes and performance improvements. (a) Flux decline rate and (b) total flux decline of PVDF and PVDF@FAS-PS membranes. (c) Membrane porosity upon the introduction of FAS-PS copolymer. (d) Membrane hardness and recovery index data; panels (a–d): reprinted from (Jiang et al. 2022) with permission from Elsevier. (e) UF membrane modified by dopamine, protease, and lipase. (f) NOM rejection by modified UF membranes; reproduced from (Asadi et al. 2023) with permission Elsevier).

Membrane morphology and surface chemistry remain central to improving GDM system performance. Ongoing development of nanostructured and biofunctional materials holds promise for scalable, high-efficiency water treatment technologies.

6 Molecular dynamics of water and contaminants

Water molecules exhibit intrinsic physicochemical properties – most notably, their polarity and capacity to form extensive hydrogen-bonding networks – that govern their interactions with membrane materials. These interactions are critical in dictating the transport behavior of water across membrane layers and, by extension, the efficiency of filtration processes. Structural features of the membrane, such as pore size, geometry, hydrophilicity, and surface roughness, modulate these interactions and thereby influence permeability and selectivity. For example, the dynamic hydrogen-bond network among water molecules plays a key role in mediating intra-membrane fluid transport and can facilitate proton conduction, enhancing filtration performance under hydrated conditions (Paparo et al. 2009).

The selectivity of ultrafiltration membranes, defined by their ability to discriminate among solutes based on physicochemical size and interaction potential, is central to their utility in removing a broad spectrum of contaminants, including organic molecules, inorganic ions, and microbial agents. This selectivity is inherently linked to the membrane’s microstructure and chemical composition. The complex interplay between water, solutes, and membrane surfaces presents a formidable challenge to experimental characterization. To address this, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have emerged as a powerful tool for probing hydration structures, solute–membrane interactions, and transport phenomena at atomistic resolution (Kalra et al. 2003; Mohammadi et al. 2020). These computational methods enable predictive modeling of membrane performance across varying operational conditions and offer a rational basis for the design of next-generation filtration materials optimized for water purification.

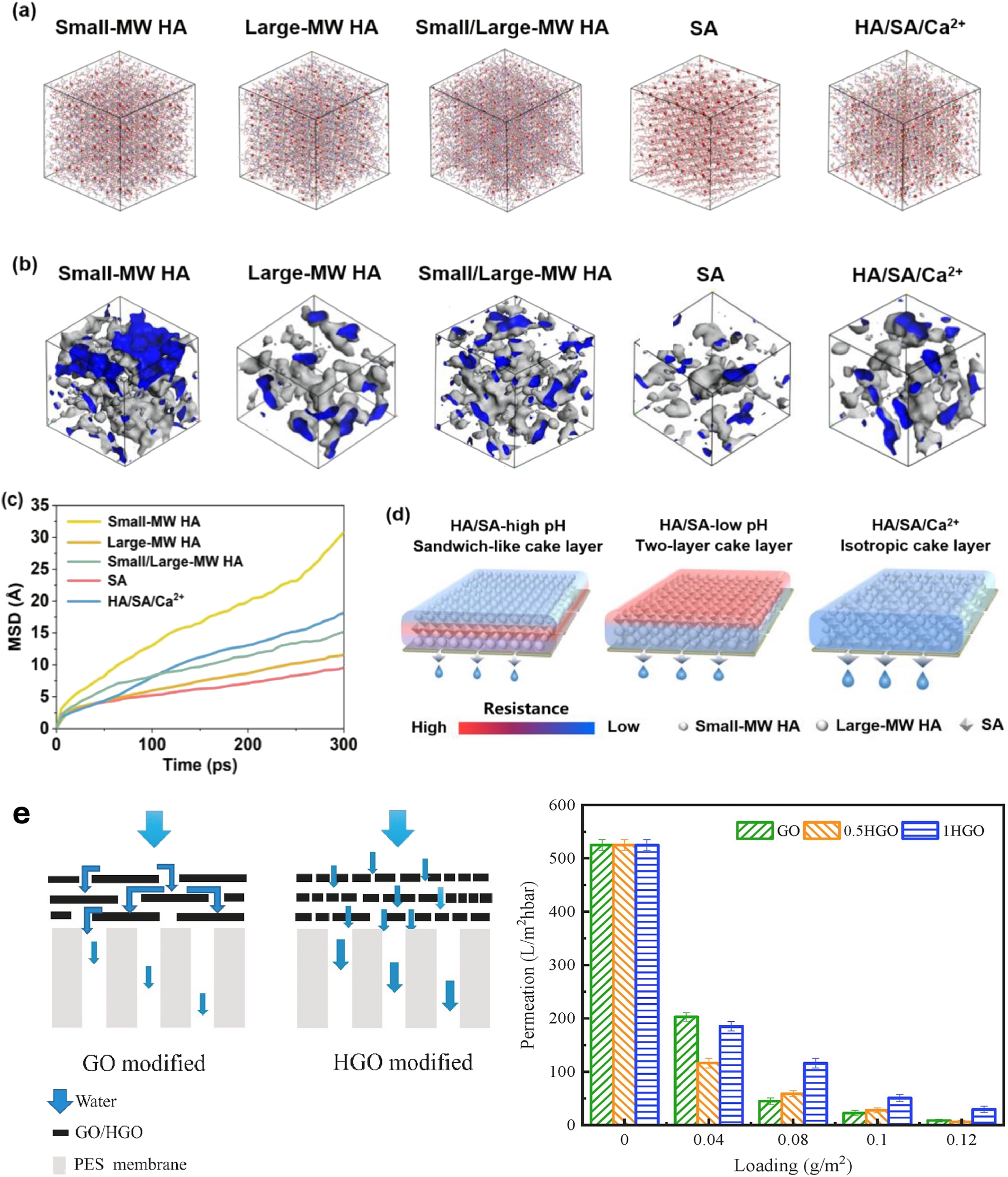

In a recent study, Wu et al. investigated the role of water quality factors – specifically the presence of divalent calcium ions (Ca2+) – on the structural organization of cake layers and the subsequent implications for water transport (Wu et al. 2023). Their results showed that Ca2+ ions induce a transition from a sandwich-like to an isotropic configuration of the cake layer by promoting cross-linking between sodium alginate (SA) and humic acid (HA) molecules (Figure 6a–d). This reorganization enhances the spatial distribution of macromolecules, thereby increasing void volume and forming additional water channels. The isotropic architecture yielded a 147 % increase in water transport coefficient, a 60 % reduction in resistance, and a 21 % improvement in membrane-specific flux. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations revealed that cake layers composed of high-molecular-weight HA contained 65.6 % fewer water channels compared to those formed with low-molecular-weight HA. The mixed-molecular-weight configuration exhibited a 31.8 % increase in the mean-square displacement of water molecules and a 59.2 % enhancement in transport coefficient, highlighting a distinct structure–property relationship.

Water transport in ultrafiltration membrane. (a) Water molecules with solute contents; (b) free volume or voids in water molecular dynamic simulation; (c) the mean-square displacement (MSD) of water molecules. (d) Distribution of water filtration resistance in various cake layer structures; panels (a–d) reproduced from (Wu et al. 2023) with permission from Elsevier. (e) Water molecule transport through graphene oxide coated UF membrane; reproduced from (Ding et al. 2021) with permission from Elsevier.

Design strategies for high-performance membranes increasingly focus on tailoring pore structure and surface functionality to control fouling and enhance selectivity. Isoporous membranes fabricated via micro- and nanoengineering provide well-defined transport pathways and have shown superior contaminant removal efficiency across a range of particle sizes (Warkiani et al. 2013). These membranes are particularly beneficial for water treatment applications where precise solute separation is essential (Maru et al. 2024; Mohammadi et al. 2020). Advances in material chemistry have further enabled the incorporation of metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), graphene oxide (GO), and other nanomaterials to improve surface reactivity and mechanical stability. In one such example, Ding et al. introduced holey graphene oxide (HGO), derived by hydrothermal etching of GO, to enhance ultrafiltration performance (Ding et al. 2021). Membranes modified with HGO at a loading of 0.08 g m−2 exhibited more than double the water permeability of their GO-modified counterparts, with corresponding improvements in rejection rates for HA (92 %), SA (72 %), and bovine serum albumin (85 %). This enhancement was attributed to increased porosity (∼10.2 %) and the formation of ∼3 nm in-plane nanopores, which facilitated greater water flux and improved hydrophilicity, as evidenced by a reduction in contact angle from 71° to 35° (Figure 6e).

Solute–solvent interactions are an additional layer of complexity in UF processes. The solubility, diffusivity, and molecular size of dissolved species influence their transport through and interactions with the membrane matrix. In multicomponent systems, these interactions can either promote or inhibit the separation of specific contaminants, depending on the chemical environment (Banerjee 1984). Such considerations necessitate the use of predictive tools to evaluate system-level behavior under variable water chemistries.

Surface functionalization remains a prominent route for improving antifouling behavior. Functional groups such as hydroxyl (–OH) and carboxyl (–COOH) enhance membrane hydrophilicity and facilitate the formation of hydration layers that deter foulant adhesion. Wu et al. demonstrated that the inclusion of hydroxyl-functionalized additives in mixed-matrix membranes suppressed HA-induced fouling and preserved flux stability (Wu et al. 2023). Similarly, carboxyl-rich surfaces promote electrostatic repulsion and hydrogen bonding with hydrophilic solutes, yielding membranes with higher resistance to organic fouling (Wu et al. 2023).

Material innovations extend beyond polymer chemistry to include ceramic and hybrid platforms. Silicon-based membranes functionalized with silica nanoparticles exhibit improved hydrophilicity and reduced foulant adhesion, largely due to enhanced surface charge and hydration effects (Tomina et al. 2019). Kaolinite-based ceramic membranes provide similar advantages through intrinsic surface hydroxylation, enabling effective mitigation of biofouling and organic accumulation (Li et al. 2022). These materials also offer superior mechanical and thermal stability, essential for sustained operation in harsh environments. Composite structures that integrate kaolinite into silicon matrices further improve mechanical robustness, ensuring long-term integrity under elevated pressure and temperature (Li et al. 2022).

Surface pretreatments, particularly oxidative conditioning, have been shown to amplify membrane performance by modifying surface energy and functional group density. Agoudjil et al. reported that oxidized silicon-based membranes demonstrated enhanced antifouling characteristics and higher flux recovery rates across diverse operational settings (Agoudjil et al. 2015). Analogous improvements were observed in kaolinite-ceramic membranes subjected to oxidative treatments, which increased their rejection of organic pollutants and reduced irreversible fouling.

Beyond antifouling, these advanced materials also exhibit improved mechanical and thermal stability. The integration of kaolinite into silicon-based membranes provides additional structural reinforcement, enabling these membranes to maintain their integrity under high-pressure or high-temperature conditions (Ravishankar et al. 2018). This combination of chemical and structural advantages positions silicon-based and kaolinite-ceramic membranes as promising candidates for long-term, sustainable GDM applications.

Membrane fouling, where contaminants accumulate on the membrane surface, poses a significant challenge in filtration systems. It results from the complex interactions between water constituents and the membrane surfaces. To combat this issue, the development of antifouling membranes and enhancements in membrane materials, such as the incorporation of PVDF nanofibre layers, have been explored. These innovations improve the membranes’ permeability and wettability, which are essential for maintaining high levels of filtration efficiency over time (Roche and Yalcinkaya 2018). Furthermore, the hierarchical porous structure of some nanofibrous membranes offers excellent flexibility and high permeate flux, which are beneficial for efficient molecular separation (Shan et al. 2017).

The intricate relationship between the composition and structure of membranes and their interaction with water molecules and contaminants is fundamental to understanding and improving the filtration process. Continued advancements in materials science and membrane technology are critical for developing more effective filtration systems. These efforts are directed towards creating membranes that not only meet stringent requirements for water permeability and mechanical stability but also demonstrate superior selectivity and efficiency in removing a wide range of contaminants.

GDM systems rely solely on gravitational force, offering an energy-efficient and practical solution for decentralized water treatment, particularly in areas with limited resources. These systems provide clean drinking water with minimal infrastructure and energy requirements, making them a viable strategy to combat global water scarcity. GDM filtration operates through the hydrostatic pressure generated by gravity, driving water or other liquids through the membrane. This simplicity makes GDM systems especially suitable for rural and emergency water treatment scenarios, as they function without relying on external energy sources (Kota et al. 2012; Lee et al. 2020).

The transmembrane pressures (TMPs) utilized in GDM studies, as summarized in Figure 7, illustrate the feasibility of ultralow-pressure operation sustained by the hydrostatic head of feed water. Figure 7 highlights notable differences between membranes based on polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) and polyethersulfone (PES). PVDF membranes demonstrate superior performance, with flux values ranging from 10 to 140 LMH across TMPs of 10–150 mbar, outperforming PES membranes, which cluster at flux values below 50 LMH and TMPs under 5 mbar. Permeability measurements further highlight the superior performance of PVDF membranes, with values ranging from 200 to 3,000 LMH/bar, significantly surpassing the 100 to 1,200 LMH/bar range observed for PES membranes.

(a) Flux, transmembrane pressure (TMP), and permeabilities of (b) PES and (c) PVDF membranes used in GDM studies. Sources: (Akhondi et al. 2015; Chang et al. 2022; Chomiak et al. 2014; de Souza et al. 2023; Derlon et al. 2016, 2013; Desmond et al. 2018a; Ding et al. 2017; Huang et al. 2023; Ishak et al. 2022; C. Liu et al. 2020; Peter-Varbanets et al. 2010; Shao et al. 2017; Shi et al. 2020; Stoffel et al. 2023; Wu et al. 2017, 2016, 2024; Zhang et al. 2022).

To address challenges such as fouling and to further enhance GDM performance, researchers are actively developing innovative materials. Recent advancements include the incorporation of nanomaterials, advanced polymers, and bio-inspired coatings, which have collectively improved permeability, fouling resistance, and selectivity. These advancements will be explored in greater detail in the subsequent section.

7 Fouling and its mitigation

Fouling remains a major challenge in membrane filtration systems, involving a combination of organic, inorganic, colloidal, and biological mechanisms that collectively diminish filtration efficiency and overall system performance. Organic fouling typically arises from the accumulation of natural organic matter (NOM), proteins, and polysaccharides, whereas inorganic fouling is driven by the scaling of salts and minerals. Biofouling, characterized by microbial colonization and the production of extracellular polymeric substances (EPS), and colloidal fouling, caused by fine particulate matter, further contribute to the decline in membrane performance. These mechanisms often act synergistically, presenting complex operational challenges (Jensen et al. 2014; Liao et al. 2004).

Recent advances have improved our understanding of fouling processes at the molecular level (Figure 8). Membrane properties such as pore size distribution, surface charge, and hydrophilicity significantly influence fouling susceptibility (Wu et al. 2024). Molecular dynamics simulations have provided insights into how interactions among water molecules, solutes, and foulants contribute to membrane fouling. For instance, divalent cations such as calcium can promote EPS aggregation, resulting in denser biofilm formation and increased resistance to cleaning (Chen et al. 2024). Additionally, the irreversible adsorption of NOM on hydrophobic membrane surfaces underscores the need for hydrophilic surface modifications to mitigate fouling (Wang et al. 2017).

Fouling characterizations. (a) Flux profile and foulant layer on the membranes taken by CLSM; reproduced from (Wang et al. 2024) with permission from RSC publications. (b) ATR-FTIR spectra, (c) Gibbs free energy of fouling-membrane and fouling-fouling interactions, and (d) CLSM images of component distribution on membrane surface; panels (b–d) reproduced from (Feng et al. 2023) with permission from Elsevier.

Effective fouling mitigation requires material innovation, operational adjustments, and system design optimization. Advances in membrane materials have yielded significant improvements in antifouling performance. For instance, membranes grafted with zwitterionic polymers exhibit enhanced hydrophilicity and resistance to both organic and biofouling. Studies (Liu et al. 2020) showed that such modifications maintained stable flux over 30-day operations using wastewater, outperforming conventional membranes.

Material innovations have also enabled the development of hybrid membranes incorporating advanced materials such as graphene oxide, silicon nanoparticles, and kaolinite ceramics. These additives enhance not only antifouling performance but also mechanical strength and thermal stability – properties essential for long-term operational reliability (Ravishankar et al. 2018). Nanoparticles such as titanium dioxide (TiO2), zirconium dioxide (ZrO2), and silver (Ag) have demonstrated notable antifouling capabilities. For example, ZrO2–LiCl-modified polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes exhibited enhanced hydrophilicity, with a contact angle reduction to 64°, and achieved a flux recovery rate (FRR) of 96.9 %, alongside a total organic carbon (TOC) rejection rate of 96 % (Aryanti et al. 2024). Similarly, silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) synthesized via in-situ methods improved membrane hydrophilicity and antimicrobial activity, achieving a remarkable 98.64 % FRR and over 99.99 % bacterial inhibition (Jiang et al. 2024). Additionally, graphene oxide (GO) and cerium-doped TiO2 composites (GO/Ce–TiO2) exhibited synergistic effects, reducing fouling through photocatalytic degradation (97.4 % BSA degradation) and enhancing flux recovery to 82.38 % (Ma et al. 2024).

Polymeric additives, such as poly(ethylene glycol)-block-poly(propylene glycol) (PEG-PPG) and polyzwitterionic hydrogels, significantly enhance membrane hydrophilicity. The combination of PEG-PPG with nitrogen-doped TiO2 (N–TiO2) resulted in a 499 % increase in water flux and reduced fouling through photocatalytic activity (Wang et al. 2024). Zwitterionic coatings, such as l-cysteine-functionalized halloysite nanotubes (Cys-PDA-HNTs), effectively reduced irreversible fouling by 18.5 % and improved flux recovery to 81.5 % due to enhanced surface hydration (Zhang et al. 2023). However, it is important to note that such coatings may exacerbate inorganic fouling, highlighting the trade-offs inherent in membrane design (Lin et al. 2024).

Photocatalytic nanoparticles, including bismuth vanadate (BiVO4) combined with reduced graphene oxide (rGO) and silver@bismuth oxychloride (Ag@BiOCl), utilize light to degrade organic contaminants and mitigate fouling. BiVO4/rGO membranes achieved over 99 % TOC removal and 89 % flux recovery under visible light (Esmaili et al. 2023). Ag@BiOCl composites expanded light absorption to 508 nm, enabling visible-light-driven self-cleaning and achieving an FRR of 85.98 % (Gao et al. 2025). These materials also generate reactive oxygen species that disrupt the adhesion of foulants.

Bio-inspired approaches, such as the use of magnetotactic bacteria (MTB), have been shown to reduce transmembrane pressure (TMP) by 5 kPa under magnetic fields while enhancing chromium (Cr6+) removal by 20.10 % (Lu et al. 2025). Hybrid systems, such as sulfonated graphene oxide-zinc oxide (SGO-ZnO), created interlayer pathways that significantly boosted water flux to 601 L/m² h−¹ while maintaining over 98 % BSA rejection (Ding et al. 2025). Additionally, zeolite nanoparticles (S-β) improved flux recovery to 100 % at 50 ppm oil through optimized pore structures (Mousavi et al. 2024).

Innovative fabrication methods, such as dual-casting for PVDF-PAN membranes, have preserved interconnected microchannels, achieving a water permeance of 640 LMH·bar−1 – four times higher than that of commercial membranes (Güldiken et al. 2025). Non-solvent-induced phase separation (NIPS) with UiO-66-NH2@GO mixed-matrix membranes (MMMs) combined high flux (591.25 L/m² h−1) with 94.74 % antifouling efficiency (Wang et al. 2024).

Multifunctional nanomaterials are revolutionizing ultrafiltration membranes by integrating multiple properties, such as enhanced adsorption, antimicrobial activity, and improved mechanical strength. Magnesium-aluminum-titanium (Mg–Al–Ti) ternary oxides incorporated into polysulfone membranes have demonstrated the ability to adsorb heavy metals (e.g., 256.6 mg/g As) while resisting biofouling, achieving a 92.5 % FRR and inhibiting microbial growth (Banerjee et al. 2024). These materials demonstrate the trend toward multifunctionality in the design of UF membranes, addressing multiple challenges simultaneously.

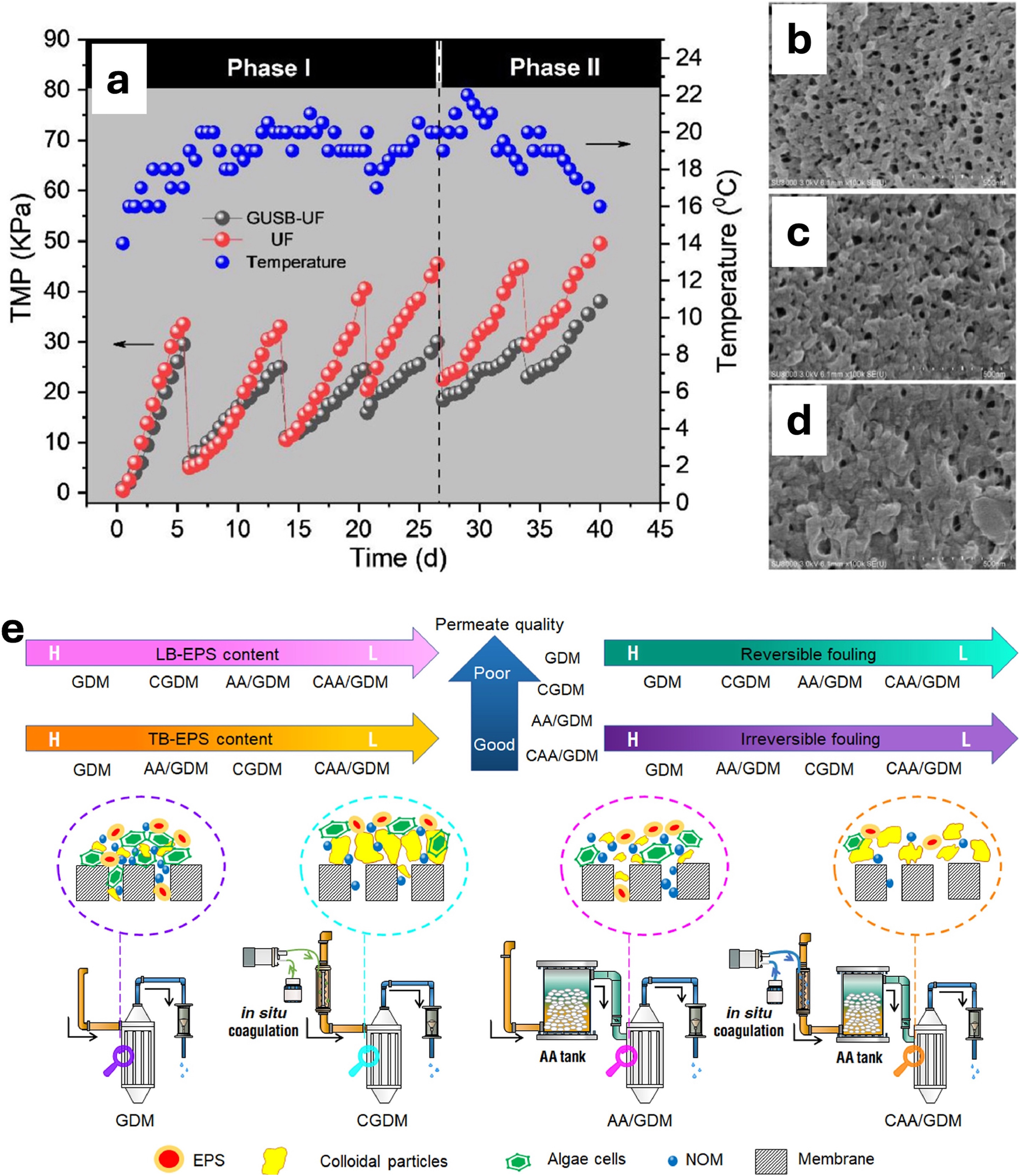

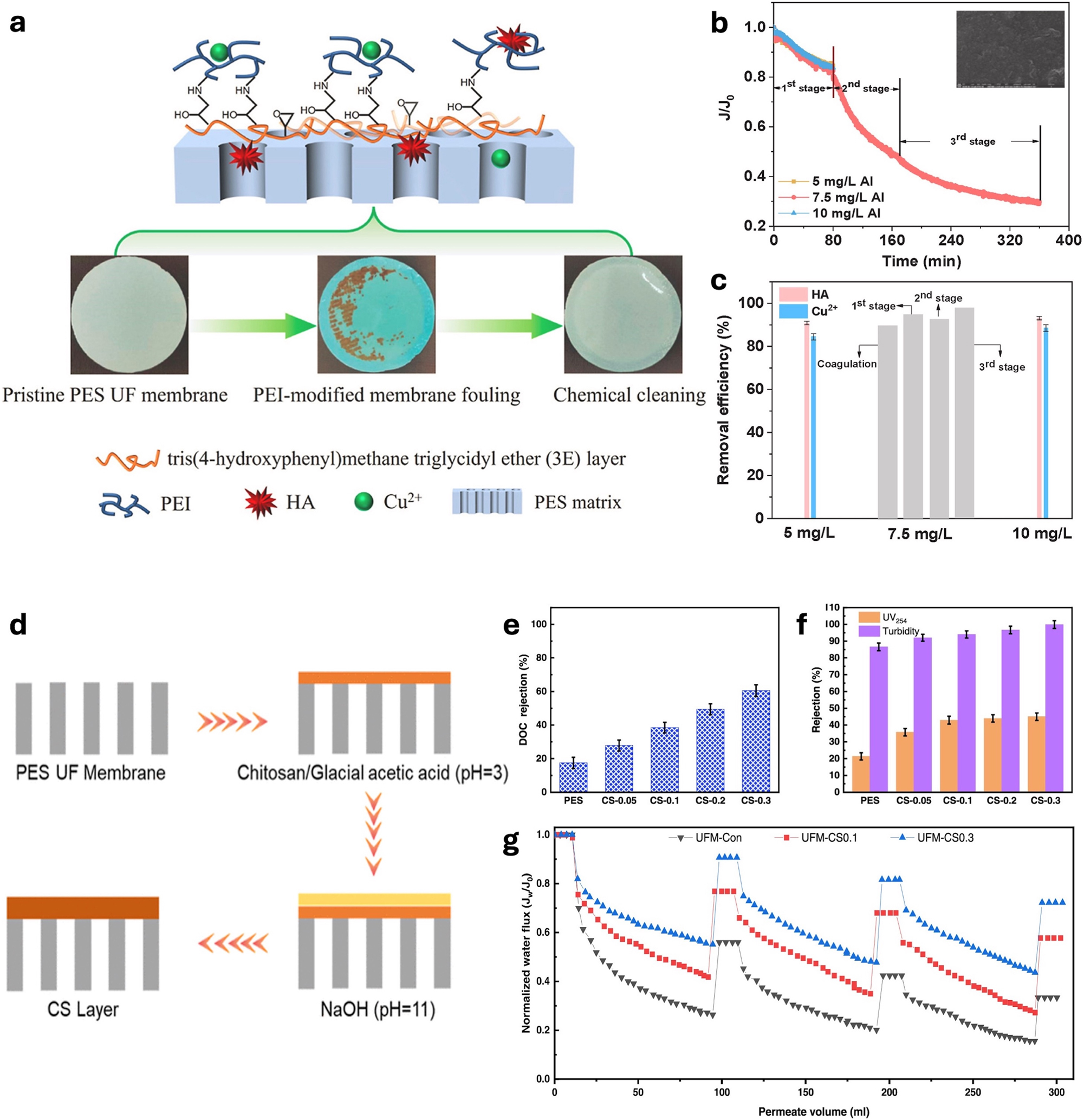

Pretreatment methods such as coagulation and granular upflow slow biofilters (GUSB) are other alternatives to fouling mitigation strategies. Coagulation encapsulates NOM into larger flocs, minimizing pore blockage and facilitating easier removal during cleaning. GUSB systems effectively reduce biopolymer concentrations, slowing fouling progression and extending membrane life (Xu et al. 2021). These methods are particularly effective when combined with gravity-driven systems, which inherently operate at lower pressures, reducing fouling rates (Figure 9a–d). Du et al. (2022) investigated fouling mitigation in GDM systems through coagulation and adsorption techniques. The combined coagulation and anionic adsorption/GDM (CAA/GDM) system reduced irreversible fouling by promoting loose floc formation, which created a porous biofouling layer on the membrane surface. This porous layer allowed for improved flux stability and reduced fouling resistance compared to control systems. Their findings highlighted the critical role of microbial community dynamics in fouling mitigation, with specific bacteria such as Bdellovibrio effectively removing EPS and low-molecular-weight organics and reducing overall fouling rates (Figure 9e). Pre-oxidation treatments, including ozonation and permanganate application, have also been shown to reduce fouling by altering foulant chemistry and improving membrane surface wettability (Feng et al. 2023).

Fouling mitigations. (a) TMP progression in GDU with gravity-driven up-flow slow biofilter GUSB-UF and UF systems during both operational phases. Surface morphology of (b) the pristine membrane, and the membranes from (c) GUSB-UF and (d) UF systems after cleaning; panels (a–d) reproduced from (Xu et al. 2021) with permission from Elsevier. (e) Mechanisms behind flux stabilization and water quality in the four systems. L denotes low level, H denotes high level; reproduced from (Du et al. 2022) with permission from Elsevier.

Operational parameters such as feed water composition, flow rate, and TMP significantly influence fouling dynamics. Intermittent operation, allowing for relaxation and cleaning cycles, has proven effective in stabilizing flux and reducing fouling resistance. Chemical cleaning protocols targeting specific foulants, including caustic agents for organic deposits and acids for inorganic scaling, are essential components of maintenance regimens (Chawla et al. 2017).

To realize the full potential of GDU systems in resource-limited settings, fouling mitigation strategies (Table 1) must prioritize operational simplicity, low energy demand, and minimal chemical use, as complex procedures and frequent dosing undermine accessibility and sustainability. While pretreatment methods such as prefiltration, coagulation, chemical injection, they introduce chemical inputs and added complexity that may limit decentralized implementation. Passive membrane modifications – such as incorporating advanced nanomaterials – offer energy-free antifouling benefits but require careful consideration of fabrication costs and long-term stability. Operational optimizations, including passive hydraulic control and relaxation protocols, are particularly promising for maintaining flux and mitigating fouling without chemicals or energy-intensive equipment. Though cleaning remains necessary, methods must balance effectiveness with ease of use and durability; solid-state disinfectants like sodium dichloroisocyanurate provide practical handling advantages but still demand user intervention.

Strategies for fouling mitigation in gravity driven membrane.

| Mitigation technique | Effectiveness | Cost implications | Scalability potential | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Membrane modification | ||||

|

|

||||

| Multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) membrane modification | Flux recovery rate (FRR) 98.5 %, 12.4 % flux increase | Commercial-grade MWCNTs cost ∼$1.0/g, increasing membrane cost by 7.7–13.7 % | Industrially scalable | Chen et al. (2025) |

| Blending PVDF membranes with polyacrylonitrile (PAN) via dual-casting technique | FRR improved to 71 %; protein adsorption was reduced | PAN is a low-cost hydrophilic additive | Fabrication method is straightforward and suitable for large-scale membrane production | Güldiken et al. (2025) |

| Sandwich-like sulfonated graphene oxide (SGO)-ZnO composite in polysulfone ultrafiltration membrane | FRR improved from 60 % to >80 %; irreversible fouling was reduced from ∼40 % to ∼10 % | ZnO is inexpensive | Fabrication method is straightforward and suitable for large-scale membrane production | Ding et al. (2025) |

| Pre-deposition of biochar (BC) and iron-modified biochar (FBC) | BC increased stable flux and pollutant removal; FBC enhanced pollutant removal but decreased flux | Biochar costs ∼1/10 of commercial activated carbon; low-cost agricultural waste source reduces costs | Scalability implied | Liu et al. (2024) |

| Pre-coating with aluminum-based flocs (ABF) | Stable flux at low hydrostatic pressure (60 mbar) comparable to higher pressure (100 mbar) | 38.5 % energy savings (compared to GDM) | Scalable for larger capacity | Sun et al. (2025) |

| Manganese oxide (MnOx) film coating on membranes | Increased stable flux by ∼16.3 % | Simple, cost-effective approach | Scalable for larger capacity; possibility of particle detachment | Luo et al. (2024) |

| Pre-deposition of powdered activated carbon-manganese oxide (PAC-MnOx) | Biofilm integrity influenced flux and removal trends | Cost not mentioned | Scalable for larger capacity; possibility of particle detachment | Wang et al. (2024) |

|

|

||||

| Improvement of hydrodynamic and operating conditions | ||||

|

|

||||

| Fluidized ceramsite in fixed-bed ceramic membrane filtration (GDFBCM) | Reduced membrane fouling by 29 % | Continuous fluidization with high-pressure gas | Limited scalability due to operational costs | Lin et al. (2025a) |

| Continuous aeration to fluidize birnessite in ceramic membranes | Maintained high flux (∼34 L/m2 h), improved permeability by scouring effect | Low energy demand; reduced treatment costs compared to conventional methods | Suitable for small-scale rural; modular installation promising for decentralized use | Song et al. (2024) |

| Relaxation strategies (varying durations and frequencies) | Up to 528 % flux enhancement; up to 80 % reduction in irreversible fouling; thinner fouling layers and fewer foulants | Reduced maintenance cost | Scalable for larger scale; required intensive operation control | Lee et al. (2025) |

|

|

||||

| Integration of pre-treatment system | ||||

|

|

||||

| Pre-chlorination of feedwater | Reduced EPS content, formed thinner, looser fouling layers | Inexpensive chlorine use | Scalable in resource-limited settings; widely applicable; possibility of disinfection by product generation | Miwa et al. (2025) |

| Biological ion exchange (BIEX) resin pre-treatment | BIEX pre-treatment doubled stabilized flux; removed ∼74 % DOC before membrane filtration | Kaolin-based ceramic membranes cost-effective; BIEX reduces chemical use and waste, lowering expenses | Good scalability potential for decentralized small water treatment systems | Rasouli et al. (2024b) |

| Gravity-driven up-flow slow biofilter (GUSB) pre-treatment | Reduced membrane fouling by removing natural organic matter and biopolymers; improved effluent quality | Additional cost for biofilter | Scalable for larger scale | Xu et al. (2021) |

|

|

||||

| Hybrid system | ||||

|

|

||||

| Electro-functionalization: in-situ electro-oxidation (ISEO) | Increased permeability by 22 % | SEC = ∼0.13 kWh/m3; increased energy cost | Scalable for larger scale | Lin et al. (2025b) |

| Electro-functionalization: ex-situ electro-coagulation (ESEC) | Membrane flux nearly 4.8 times that of GDM | SEC = 3.47 × 10−3 kWh/m3; increased energy cost | Scalable for larger scale | Lin et al. (2025b) |

| Electro-functionalization: KMnO4-enhanced electro-oxidation | Facilitated active chlorine oxidation of ammonia and algal toxins; fouling layer more porous | SEC = ∼0.14 sun kWh/m3; increased energy cost | Scalable for larger scale | Lin et al. (2025b) |

| In-situ coagulation combined with activated alumina filtration (CAA) | Enhanced GDM flux (from 2.0 to 8.3 L/(m2 h)) and stable water production | GDM: 0.32 CNY/m3; GDM + in-situ coagulation (CGDM) = 0.97 CNY/m3; GDM + activated alumina filtration (AA-GDM) = 0.12 CNY/m3; combination of them (CAA-GDM) = 0.54 CNY/m3 | Scalable for larger scale | Du et al. (2022) |

| Biological pretreatment (tubular fillers, fiber bundles, aeration) | Improved stabilized flux (e.g., 3.69 ± 0.89 L/m2 h) and organic contaminant removal (COD 59.7 %, DOC 48.3 %) | Reduced operation and maintenance costs | Applied in decentralized wastewater treatment; scalability not explicitly evaluated | Gong et al. (2024) |

| Octadecyl-quaternium hybrid coagulant (OQHC) pre-coagulation | Achieved 93.45 % microplastic removal, outperforming conventional coagulants; improved GDM stability and permeability | Increased chemical cost; required dosing monitoring | Scalability not evaluated; recommended for future research | Chen et al. (2024) |

|

|

||||

| Membrane cleaning | ||||

|

|

||||

| Passive gravity-driven membrane filtration (PGDMF) | Maintained ∼60 % of initial permeability over 3 years, outperforming systems without hydraulic control | Capital cost ∼$36,000 USD for community-scale system (excluding disinfection) | Scalable for larger scale; required intensive hydraulic control | Wei et al. (2025) |

| Sodium dichloroisocyanurate (NaDCC) tablets for cleaning | Achieved 46.55 % permeability recovery, comparable to sodium hypochlorite (48.29 %), effective for organic fouling | Required chemical consumption | Scalable for larger scale; needs dosage monitoring | Lee et al. (2025) |

| Simple forward flushing with sludge discharge | Quickly restored pressure drop, enabling stable long-term operation without hydraulic or chemical cleaning | Low operational costs; minimal cleaning and low power consumption (1–2 kWh daily) | Scalable for larger scale | Liu et al. (2025) |

| Physical cleaning: air/water backwash | Membranes showed 70–79 % reversible fouling removal; polymeric membranes 57–69 % | Physical cleaning preferred over chemical to reduce operating costs | Scalable for larger scale | Rasouli et al. (2024a) |

| Chemical cleaning: NaOH and NaOCl | Chemical cleaning less effective for irreversible fouling; NaOH increased recovery modestly; NaOCl recovery varied | Chemical cost | Scalable for larger scale; required chemical dosage monitoring | Rasouli et al. (2024a) |

| Disinfection with hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) | Increased flux by ∼15 LMH after initial cycles; oxidized organic matter and microbubble shearing alleviated fouling | Chemical cost | Scalable for larger scale; required chemical dosage monitoring | Fang et al. (2024) |

8 System design and process optimization

GDU systems have evolved significantly, focusing on achieving sustainable and efficient water treatment solutions. The optimization process emphasizes material innovation, biofilm dynamics, modular designs, and operational adaptability to meet diverse global water treatment needs.

Material selection remains essential in improving GDU performance. Polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes, modified with micro-fine powdered activated carbon (MFPAC) or zeolite (MFPZ), have demonstrated enhanced flux behavior and permeate quality by optimizing the cake layer resistance while maintaining cleaner membrane pores (Song et al. 2020). Similarly, advancements in surface chemistry, such as hydrophilic modifications and plasma treatments, have improved the antifouling properties of membranes. Modular innovations, such as the integration of four-arm star polystyrene (FAS-PS) microspheres, have further enhanced water flux and deformation resistance, demonstrating the versatility of design approaches in addressing specific purification needs (Jiang et al. 2022).

Biofilm management is another critical component of GDU optimization. Controlled biofilm formation enhances the degradation of dissolved organics while stabilizing permeate flux. For instance, introducing powdered activated carbon (PAC) into the GDU has shown significant improvements in dissolved organic carbon removal while simultaneously influencing biofilm characteristics (Huang et al. 2023). However, biofilm aging and dynamic interactions with feed water quality necessitate pre-treatment methods, such as slow sand filtration or packed bed biofilm reactors, to maintain high permeate quality and system performance (Derlon et al. 2014). The summarized performance of these strategies across studies is presented in Table 2.

Performances of GDU.

| Study focus | Description | Key results | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Micro fine particles in UF | Application of micro fine particles to enhance UF membrane performance | Flux attenuation differences observed; TOC, NH4+-N, and TN removal increased by 48 %, 93 %, 22 % (MFPAC-PVDF) and 18 %, 89 %, 20 % (MFPZ-PVDF) | Song et al. (2020) |

| Gravity-driven UF with pressure variations | Effects of varying transmembrane pressure on GDU performance | Removal efficiency of UV254 improved by 11.91 % at lower pressure; better DBP control at 50 mbar | Wu et al. (2024) |

| PAC in GDM filtration | Introduction of powdered activated carbon in GDU | Enhanced removal of DOC by 31 %, ammonia nitrogen by a significant margin; permeability reduced by 39 % | Huang et al. (2023) |

| Aluminum removal | Fe-based coagulants compared in a micro-flocculation/GDU system for Al removal | Al removal reached 75 %; particulate Al and dissolved inorganically bound Al removal at 94.9 % and 92.6 % | Yue et al. (2021) |

| Gravity-driven home UF device | Evaluation of in-home gravity UF for microbial removal | Effective removal of all tested microbial indicators; post-treatment contamination observed after 24 h | Chaidez et al. (2016) |

| Gravity-driven UF with rigid pores | Development of a PVDF membrane with rigid pores | Water flux of PVDF@FAS-PS membrane was approximately 5 times that of control; reduced BSA fouling | Jiang et al. (2022) |

| Large-scale GDM UF evaluation | Evaluation of new and second-life UF modules | Stable fluxes around 10 L/m2/h maintained for 142 days; biopolymer removal unaffected by backwash | Stoffel et al. (2023) |

| UF in algae-laden water treatment | Effect of a composite coagulant on GDU performance in algae-laden water | Alleviation of membrane fouling by 23.74 % and 58.80 % compared to control; 98.32 % algae cells removal | Du et al. (2020) |

| Biofilm impact on UF | Influence of biofilm aging on permeate quality in GDM UF | Young biofilms increase AOC degradation >80 %; permeate flux stabilized at 7.5–8.9 L/m2/h | Derlon et al. (2014) |

| Pathogen removal in gravity-driven UF | Efficacy of hollow fiber UF under gravity in removing E. coli from water | E. coli removal up to 97.70–99.03 %; flux recovery up to 94 % after backwashing | Ishak et al. (2022) |

| Performance of biofilm-controlled gravity-driven UF | GDU performance under different pressures for well water treatment | E. coli removal efficiencies at 3-log; average fluxes of 4.4–6.5 L/m2/h | de Souza et al. (2023) |

Operational parameters such as transmembrane pressure (TMP), flow rate, and backwashing frequency are crucial for optimizing system performance. Studies demonstrate that lower TMP levels (e.g., 50 mbar) improve normalized permeability and reduce fouling, offering better control over disinfection by-products (DBPs) formation and humic substance removal (Wu et al. 2024). Regular backwashing schedules, such as daily cleaning, have also been shown to stabilize flux levels, particularly in compact hollow-fiber membrane systems (Stoffel et al. 2023). Mathematical modeling and machine learning techniques are increasingly employed to fine-tune these operational parameters, ensuring consistent performance across varied applications.

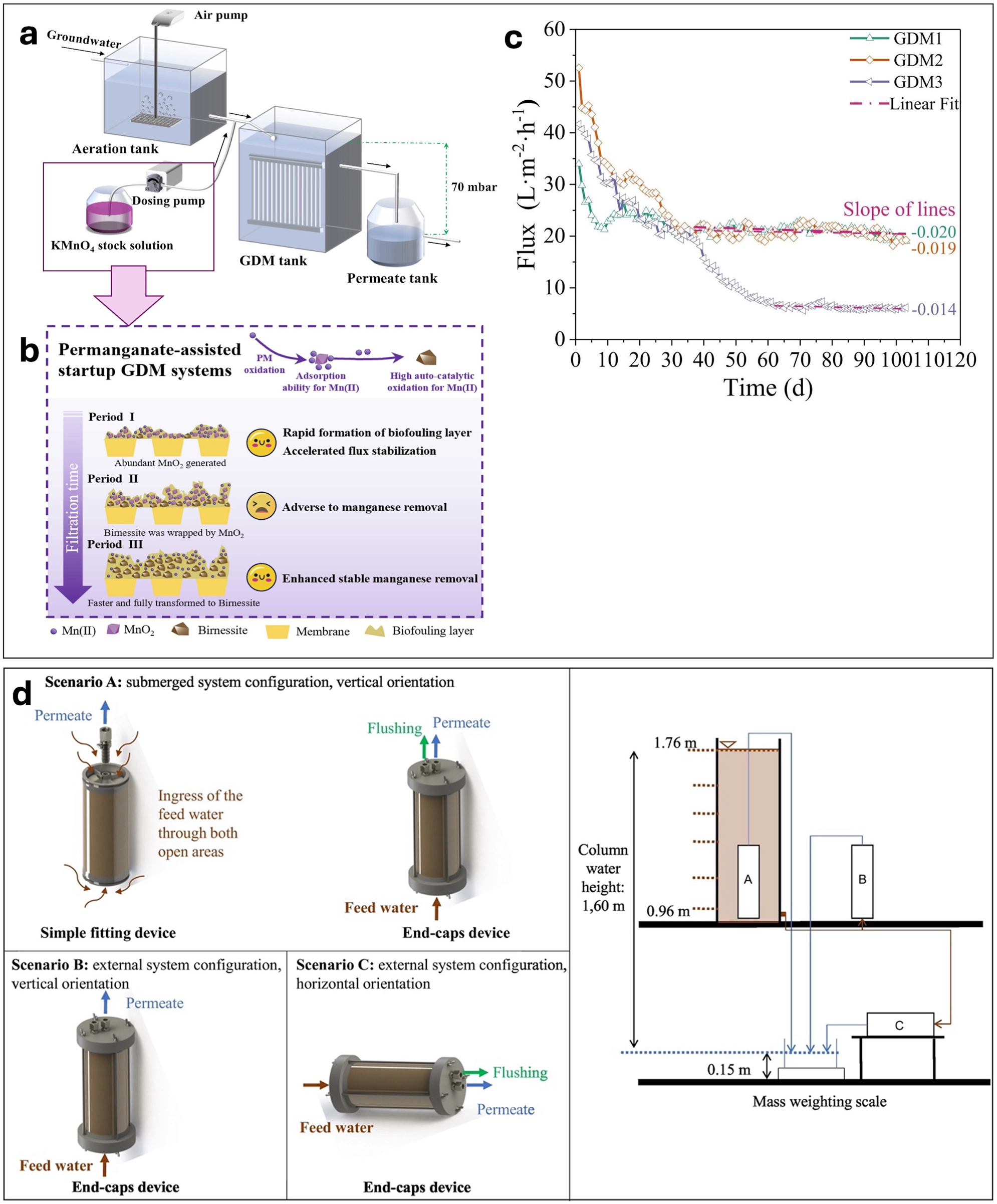

GDU systems are particularly suited for decentralized water treatment applications due to their low energy requirements and minimal dependence on chemical additives. Field studies have validated their effectiveness in treating diverse water sources, including river water, groundwater, and algae-laden water. For example, using GDU systems with intermittent permanganate addition during startup has improved manganese removal and flux stabilization, addressing specific challenges in groundwater treatment (Ke et al. 2024) (Figure 10a–c). Additionally, innovative housing designs, such as spiral-wound modules, have facilitated cost-effective deployment in rural and urban settings, showcasing the scalability of GDU (García-Pacheco et al. 2021) (Figure 10d).

System design and optimization. (a) Schematic of permanganate-assisted GDM. (b) Mechanism in permanganate assisted GDM start up. (c) Flux profile; reproduced from (Ke et al. 2024) with permission from Elsevier. (d) GDM in various set-up; reproduced from (García-Pacheco et al. 2021) with permission from Elsevier.

9 Advancements in ultrafiltration membranes

Recent advancements in ultrafiltration technology have transformed membrane development, shifting from traditional materials to innovative nanocomposites have significantly enhanced membrane performance (Janakiram et al. 2018; Kausar et al. 2022; Shukla et al. 2017). Studies have highlighted the effectiveness of nanocomposite membranes in improving filtration properties, including enhanced water permeability, and resistance to fouling (Khosravi et al. 2023; Liu et al. 2019). These innovations not only increase filtration efficiency but also balance water permeability and contaminant selectivity, surpassing previous limitations.

Nanocomposite membranes represent a significant advancement in membrane technology, leveraging nanoparticles such as metal oxides, carbon nanotubes, and graphene oxide to enhance mechanical strength and chemical resistance. These improvements not only increase filtration efficiency but also contribute to better contaminant removal, reduced membrane fouling, prolonged operational lifespan, and higher water quality.

A notable development in this area is the incorporation of two-dimensional (2D) materials like GO and MXene into UF membranes, marking a transformative step forward. These materials offer exceptional mechanical strength, chemical stability, and antifouling properties, attributed to their atomic-scale thickness and large surface area. The integration of 2D materials enables precise control over pore size and distribution, enhancing separation efficiency and achieving a well-balanced selectivity-permeability ratio, essential for specific molecular separations. Moreover, the chemical inertness of 2D materials helps to mitigate oxidative degradation, a common issue with polymer-based membranes such as PES, thereby extending membrane lifespan. The smooth surface characteristics of GO further reduce fouling potential by minimizing particle adhesion, simplifying cleaning processes, and maintaining consistent performance (Almanassra et al. 2024).

The integration of graphene-based materials into UF membranes has significantly enhanced membrane technology. For example, membranes incorporating quaternized graphene oxide (QGO) demonstrate remarkable enhancements in anti-biofouling performance, hydrophilicity, antibacterial properties, and mechanical strength (Liu et al. 2020). Further advancements include membranes embedded with graphene oxide nanosheets and modified halloysite nanotubes, which exhibit superior hydrophilicity and a record pure water flux of 1340 L/m2 h, achieving 100 % rejection efficiency of olive oil in ultrafiltration tests (Amid et al. 2020). Graphene oxide functionalized with 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane (APTS) has expanded its use from ultrafiltration to nanofiltration, demonstrating high water permeance values and over 95 % rejection of dyes and bovine serum albumin (Luque-Alled et al. 2020).

Significant enhancements in UF membrane performance have been achieved through the integration of GO and its derivatives. For instance, incorporating graphene oxide-polyethylene glycol (GO-PEG) into PVDF membranes has substantially increased water flux to 93 L/m2 h while improving antifouling properties, achieving a flux recovery ratio of 78 % (Ma et al. 2020). Similarly, polysulfone hollow fiber membranes functionalized with zwitterionic graphene oxide have demonstrated high rejection rates for specific dyes, coupled with a pure water flux of 49.6 L/m2 h and a flux recovery ratio of 73 % against bovine serum albumin (BSA) fouling (Syed Ibrahim et al. 2020).

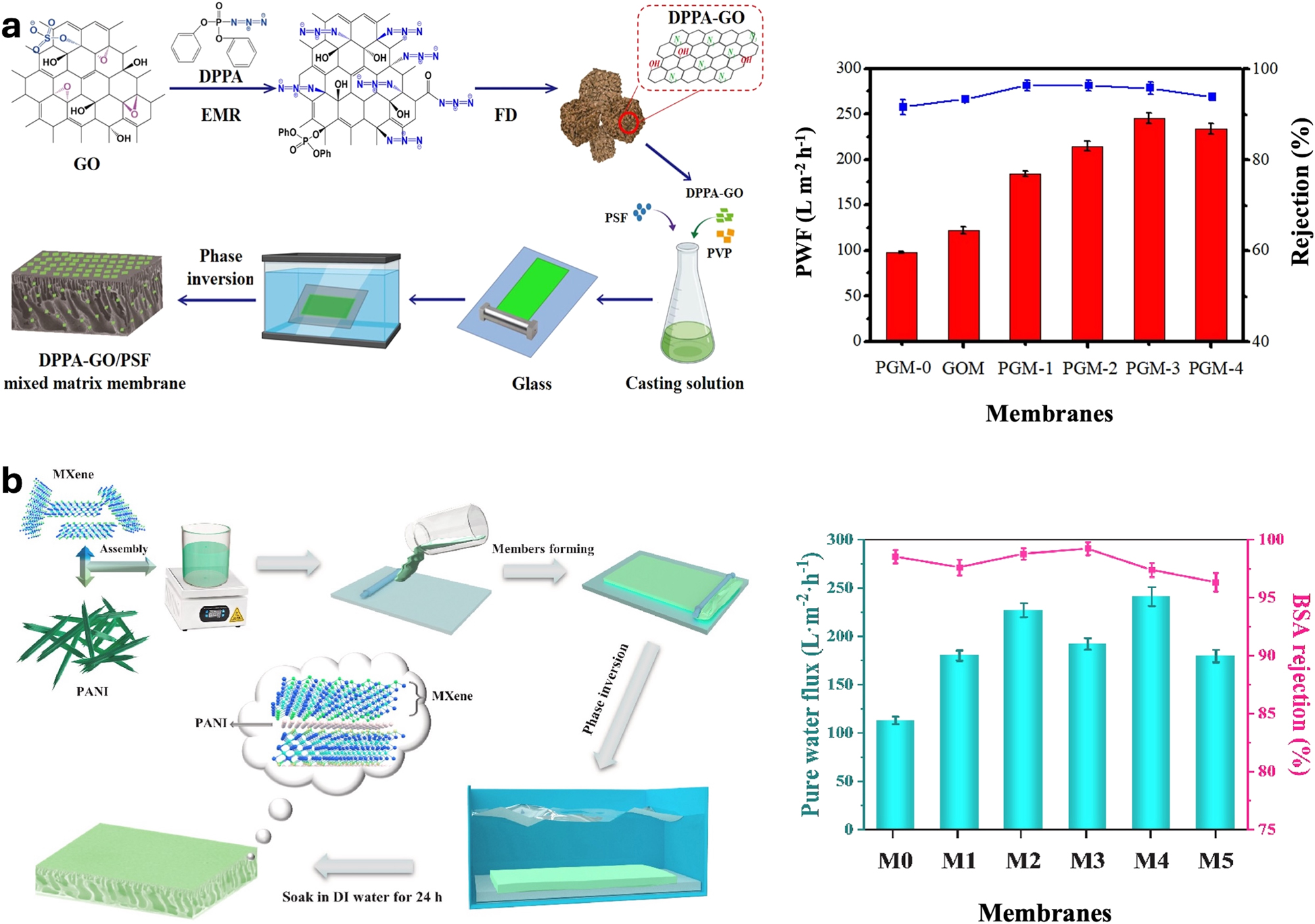

Further advancements include the use of azido-functionalized graphene oxide (AGO) in polysulfone membranes, yielding an impressive pure water flux of 245.1 L/m2 h and a BSA rejection rate of 95.8 % (Figure 11a). Additionally, these membranes exhibit significant long-term antibacterial activity against E. coli and S. aureus, underscoring their potential for extended operational life in water treatment applications (Xu et al. 2022). The inclusion of dodecylamine-functionalized graphene oxide (rGO-DDA) has been shown to enhance antifouling and antibacterial properties while improving flux recovery ratios, effectively preventing fouling and maintaining membrane cleanliness (Alkhouzaam and Qiblawey 2021).

UF membranes incorporated with 2D materials. (a) Graphene oxide; reproduced from (Xu et al. 2022) with permission from Elsevier. (b) Mxene; reproduced from (Li et al. 2023) with permission from Elsevier.

Moreover, polysulfone composite UF membranes incorporating polydopamine-functionalized graphene oxide (rGO-PDA) exhibit a notable improvement in pure water flux, approximately doubling the flux of pristine membranes. The flux recovery ratio after three fouling cycles demonstrates a significant enhancement, reflecting the membrane’s resilience and improved operational efficiency (Alkhouzaam and Qiblawey 2021).

MXene, a two-dimensional material known for its ultrathin structure, mechanical robustness, and thermal stability, provides numerous advantages for ultrafiltration membrane applications. Its high hydrophilicity, derived from abundant surface functional groups, enhances water affinity and imparts superior antifouling properties, essential for maintaining long-term membrane performance. Incorporating MXene into polymeric matrices has demonstrated significant improvements in water flux, oil rejection efficiency, and membrane stability (Nabeeh et al. 2024).

Building on these properties, Li et al. developed composite membranes by integrating polyaniline (PANI) and Ti3C2Tx (MXene) using an electrostatic assembly method (Li et al. 2023). PANI was employed to regulate the interlayer spacing of MXene, creating a conductive network within the membrane structure. The resulting mixed ultrafiltration membranes, fabricated through non-solvent-induced phase separation, exhibited a 200.9 % enhancement in pure water permeation flux (Figure 11b). Additionally, they maintained high retention rates for bovine serum albumin (BSA) (>99 %) and dyes such as Congo Red (99.1 %) and Methyl Blue (98.4 %). The membranes also achieved a conductivity of 0.5 S m−1, enabling electrostatic repulsion to minimize contaminant deposition, resulting in a flux recovery ratio (FRR) of 93.7 %. This study highlights the substantial potential of MXene-based composite membranes in advancing permeability, selective separation, and antifouling properties through improved conductivity and electrostatic repulsion mechanisms.

Graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4), another two-dimensional material with a hexagonal lattice structure, has proven to enhance UF membranes by improving their chemical stability, hydrophilicity, and antifouling capabilities. These benefits are attributed to its high surface area and abundant functional groups (Almanassra et al. 2024). For example, blending g-C3N4 with sulfur-doped nanoparticles in polysulfone membranes increased porosity to 46 % and boosted the BSA rejection rate to 99 %, compared to 84.8 % for unmodified membranes, reflecting significant filtration efficiency gains (Vilakati et al. 2023). Similarly, integrating g-C3N4 into polysulfone (PSF) and polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes significantly enhanced water flux while achieving dye rejection rates exceeding 80 % and chemical oxygen demand (COD) removal efficiency over 45 % (Senol-Arslan et al. 2023).

Further advancements include PVDF nanocomposite membranes modified with dopamine-coated g-C3N4 (PDA@DCN), which achieved a pure water flux of 390 L/(m2 h) and a BSA rejection rate of 95.9 %. These membranes also demonstrated exceptional self-cleaning performance under visible light irradiation, achieving a flux recovery rate of 84.5 %, underscoring their potential for environmentally sustainable water treatment applications (Zhou et al. 2023).

Surface modification techniques have played a critical role in enhancing the performance of ultrafiltration membranes. Methods such as grafting, coating, and plasma treatment have been employed to alter the surface properties of membranes, making them more hydrophilic and less prone to fouling. For example, applying graphene oxide coatings has been shown to improve the antifouling performance of membranes by reducing the adhesion of foulants to the membrane surface. Several studies have investigated different methods to modify ultrafiltration membranes to achieve these objectives. The study by Sun et al. involved UV-assisted graft polymerization of N-vinyl-2-pyrrolidinone onto PES membranes to enhance surface wettability and reduce adsorptive fouling during diafiltration, demonstrating the enhanced antifouling property of PES ultrafiltration membranes by incorporating a silica−PVP nanocomposite additive (Sun et al. 2009). Plisko et al. focused on modifying polysulfone ultrafiltration membranes by introducing an anionic polyelectrolyte (PASA) into the coagulation bath during membrane preparation, aiming to improve antifouling performance in water treatment applications (Plisko et al. 2020). Dobosz et al. highlighted the use of electrospun nanofibers to enhance ultrafiltration membranes, leading to improved flux and fouling resistance, showcasing the potential of nanofiber-enhanced membranes in enhancing overall membrane performance (Dobosz et al. 2017). Yan et al. explored the modification of polyamide 66 ultrafiltration membranes with graphene oxide to enhance anti-fouling performance, involving surface modification with corona air plasma and TiO2 nanoparticles coating to enhance separation efficiency (Yan et al. 2022). These studies collectively demonstrate the critical role of surface modification in improving the performance of ultrafiltration membranes. Techniques such as incorporating nanocomposite additives, enhancing membranes with nanofibers, applying graphene oxide coatings, and utilizing plasma treatments have proven effective in boosting antifouling properties, increasing flux, and enhancing separation efficiency.