Abstract

Summary translation is a regular practice in the government, commercial, and industrial sectors, yet it has received little attention in Translation Studies. Summary translation differs from “normal full translation” in the level of deliberate semantic reduction and linguistic compression or expansion relative to the source text (ST), the extent of ST–target text (TT) correspondence and the differential weighing of content. This qualitative study investigated the cognitive processes involved in summarizing translation. For this study, keystroke logging data were collected from 26 third-year BA students of Applied Linguistics who were asked to translate a Spanish opinion piece into Dutch by reducing the ST word count by more than 50 %. An analysis of the keystroke logging data, the researcher’s observational notes and paper copies of the ST showed that summarization takes place in all the phases of the translation process. During the pre-writing phase, ST content weighing and selection could be observed in the highlighting of keywords, phrases and/or sentences in the ST. Moreover, outline planning could be observed, indicating a hierarchical organisation of the discourse. These ST markings and TT outlines seemed to serve as cognitive artefacts, since the students used them both to start and to guide their TT drafting. During the TT drafting, two major translation strategies could be observed: literal patchwork translation and paraphrasing. Summarization during TT drafting was carried out through omission, deletion (through online revision), generalization, and construction strategies – the latter two being especially present among those students who employed the paraphrasing strategy. Interestingly, eight students did not engage directly in summarization but started to translate the first ST paragraphs in full, although they subsequently switched to a more summarizing approach. Summarization through the deletion of TT content and/or the reduction of the TT word count was also observable in the post-writing phase. A certain interplay could be observed between planning and TT production strategies.

1 Introduction

In recent years, several scholars (e.g., Dam-Jensen et al. 2019) have called for more comparative research on writing and translation to gain insight into the ways in which various acts pertaining to the superordinate category of text production (Dam-Jensen and Heine 2013) differ and coincide with regard to cognitive processing. A form of translation in which writing and translation appear to converge is summary translation. The act of summarizing written, oral, and multimodal texts is a regular practice across the government, commercial, and industrial sectors. However, in the realm of Translation Studies, this practice has not been researched extensively. In his paper titled “Integration of Translation and Summarization Processes in Summary Translation”, Gregory Shreve explains that accurately conveying semantic content is crucial to both summary translation and what is commonly termed “full translation”. However, summary translation is distinctly guided by a “clearly articulated request for information” (RFI) (Shreve 2006: 91), which instructs the translator to search for specific information in a single text or a corpus and to rephrase it for particular communicative objectives and intended recipients, often with specified length constraints.[1] Consequently, summary translation not only comprises the process of summarizing but also entails the identification of one or more pertinent source texts (ST) for translation.

Apart from its query-driven nature, summary translation is distinguished by four key characteristics, as outlined by Shreve (2006: 91–93): (1) the degree of semantic reduction; (2) the degree of linguistic compression or expansion; (3) the level of ST or target-text (TT) correspondence, and (4) the differential weighting of semantic content. The weighting or determination of which content units or semantic levels in the ST are appropriate to include in the TT is influenced by both the RFI and the intrinsic features of the ST itself. Less relevant ST content may be omitted or condensed or even amalgamated with other less-significant features through generalization and construction strategies (Shreve 2006: 92). This linguistic compression, resulting from semantic omission and condensation, is more extreme than the typical contraction observed in full translation, which stems primarily from linguistic differences between the source language and the target language. Consequently, the correspondence between ST and TT in summary translation is more limited, both semantically and formally. Furthermore, the sequencing of information units may not adhere to a strictly linear progression, as certain content units are combined with others mentioned before or after in the ST.

Semantic reduction and linguistic compression that are not caused by the linguistic differences of the language pairs involved in the translation task are evident in other forms of translation too. Following the functionalist approaches to translation, each translation task could possibly involve semantic reduction contingent upon whether the skopos calls for it. For instance, translation in the domain of news writing often involves the summarization of information alongside activities akin to those in summary translation, such as omitting extraneous details and reorganizing paragraph sequences (van Doorslaer 2010: 182). Moreover, specific technical constraints inherent in certain translation modalities may induce semantic reduction. In subtitling, for example, the restriction on the number of characters per line, together with the required reading speed and the pace of speech in the source material, often leads to the condensation and omission of ST content (Díaz Cintas and Remael 2007). This usually happens more at the phrase and sentence level rather than at the discourse level, the latter being more characteristic of summary translation.

Summary translation shares similarities with other text-producing activities that entail condensing STs, such as source-based writing, précis-writing, and generic summarization. In the realm of writing research, various terms are employed to describe the process of crafting a concise rendition of one or multiple written texts in the same or a different language. These terms include “source-based writing”, “summary writing”, “synthesis writing”, “reading-to-write”, and “integrated writing” (Chan 2017; Gebril and Plakans 2016; Spivey 1997). In source-based writing, there is a significant emphasis on avoiding all forms of plagiarism, whereas in summary translation, “textual borrowing” through translation is permissible (Chau et al. 2022). Précis-writing is the writing of a précis, which Russell (1988: 20) defines as “a written text, of prescribed length, that accurately summarizes a larger passage”. Whereas Russell (1988) emphasizes its use in educational settings, Schjoldager et al. (2008) relate précis-writing to a particular professional setting; they define it as the creation of concise written renditions (such as minutes and summary records) of the conferences and meetings conducted in international organizations (e.g., European Commission, UN, WHO, ITU), either for documentation purposes or in relation to policymaking. However, for educational purposes, they also propose a broader interpretation, describing précis-writing as “the summarization of information found in scientific papers, technical reports, surveys, proposals, questionnaires, articles, etc., as well as the drafting of minutes and summary records for conferences and meetings organized by certain larger companies and organizations – both within the same language and across languages (i.e., summarizing translation)” [emphasis added] (Schjoldager et al. 2008: 805). As a result, précis-writing can encompass both intralingual and interlingual approaches (the latter being termed “interlingual précis-writing” by Russell (1988)). However, it differs from source-based writing in its more concise nature, its typical focus on a single ST and the absence of integration of the précis-writer’s personal opinions. Précis-writing is employed in translator training as an exercise aimed at enhancing students’ writing proficiency and synthetical skills (Petrocchi 2020), increasing their translation speed (Bowker and McBride 2017), and helping them to differentiate between primary and secondary pieces of information in preparation for consecutive interpretation (Meyer and Russell 1988). In Shreve’s (2006: 104) article, précis-writing is mentioned casually as a form of reductive text processing, but he does not compare précis-writing and summary translation directly. Instead, he contrasts summary translation with generic summary, suggesting that, whereas the former involves representing the most significant content of the ST in the TT using a specific perspective (as articulated in the RFI) and including varying degrees of detail, the latter focuses solely on the salient content of the ST. Given that précis-writing, as defined by Bowker and McBride (2017) and Schjoldager et al. (2008), closely resembles generic summarization, this difference may serve as one of the distinguishing factors between summary translation and précis-writing too. Furthermore, the identification of one or more pertinent STs for translation also sets summary translation apart from précis-writing and generic summary, which depart from one or more given sources.

Research into the cognitive processes of summary translation is rare. The only exception, to this author’s knowledge, is the product-based study by Shreve (2006), which examines an English summary and a verbatim translation of a Chinese telephone transcript. He suggested that, in summary translation, cognitive strategies prioritize the identification of relevant content units and the exclusion of irrelevant units (2006: 93). This phenomenon is likely to be evident in the reading of the ST (2006: 103). In summary translation, reading the ST seems to encompass ST comprehension, the identification of its theme-rheme structure, the identification of primary and secondary blocks of information (called “orders of informativity” by Shreve 2006), the assessment of their relevance to the TT, considering the RFI, and an evaluation of their cohesion (Petrocchi 2020, in reference to précis-writing). Shreve anticipates that “future research will show that summary translators create a hierarchical discourse organization online to cue memory retrieval using the discourse structure of the text they are processing and the discourse relationship cues it contains” (2006: 103). Examples of such formal cues are “headings, formatting, structural layout, key phrases, position in paragraphs” (2006: 105). Shreve associates this cognitive process with Seleskovitch’s de-verbalization process, even though it is augmented by “semantic reduction through aggressive omission and integration strategies grounded in discourse processing macro-rules” (2006, p. 94). Regarding the TT formulation, Shreve points at the prevalent use of deletion, construction and generalization strategies. Construction and generalization both imply the “collapse” of semantic levels, which “implies the integration and target language expression of lower level propositional content, generally allotted their own surface representations in verbatim translation, into semantically “denser” higher level target structures” (Shreve 2006: 92). Whereas generalization focuses on combining various propositions, construction implies creating new macro-propositions from longer sequences of propositions (Shreve 2006: 99).

Empirical research that relies on process data rather than product data is essential to elucidating various aspects of the summary translation process. These include determining the process phase(s) when summarization occurs, examining the way hierarchical discourse organization takes place, exploring the way in which the integration of selected ST units during TT production takes places, analysing the interaction between planning and composition strategies, and identifying what Shreve (2006: 107) terms “the loci of failure in the cognitive processing sequence”.

2 Research questions

The present article reports on an exploratory study of the cognitive processes that occur during summarizing translation by translation students. The aim of this qualitative study was to examine when and how summarization takes place in the translation process. In this article, the term “summarizing translation” is used rather than “summary translation” because the translation task employed in our study did not entail the selection of relevant source material based on an RFI, as per Shreve’s conceptualization of summary translation.

3 Methodology

3.1 Data collection

In the academic year 2021–2022, 35 third-year undergraduate students studying Applied Linguistics (University of Anon) who were enrolled in the Translation course Spanish > Dutch 2 were asked to produce a summarizing translation of an article by Manuel Villoria Mendieta (2021) titled Rendir cuentas para transformar y renovar España, published in the Spanish newspaper El País (see Appendix I). The central topic or main theme of this article is how well Spain scores in the quality of its democracy and which measures can and need to be taken to improve this quality. This ST contained 1,170 words, which had to be reduced to 500 in the TT for publication in a Dutch newspaper. The students were provided with an electronic and a paper copy of the ST; they were allowed to make notes on the ST handout. They could work on this task in class for 3 hours, using MS Word and any digital sources and tools of their choosing, except MT systems, social media and e-mail. These changes were introduced to create a working environment that resembled the normal classroom setting (i.e., no MT) and students’ personal preferences (i.e., a paper copy of the ST). These students had already produced several other summarizing translations in this translation course and general summaries in their language courses. To increase the motivation for this particular task, individual product and process feedback was given after wards.

The translation processes of the students were registered using the unobtrusive computer keystroke logging software Inputlog (Leijten and Van Waes 2013). The course teacher (i.e., the author of this paper) also observed and noted down the students’ interactions with the paper copies of the ST. All the paper copies of the ST, including the students’ names, were collected afterwards.

3.2 Data analysis

The level of data attrition, owing to technical challenges, was 26 %, which led to a total sample of 26 students. The data analysis focused on process data. For the analysis of the keystroke logging data, both the general and source analysis files and the process graphs that Inputlog automatically generates were used. The general analysis file gave insight into what the students had typed, when and how long they paused, what and when they revised, and when they consulted external sources, among other activities. The source analysis provided information on the external sources that the students used, when and how long they used them, and also when and how frequently they switched between different windows (i.e., of the ST, the TT, and external sources). The process graphs yielded an insightful visual impression of the evolving text-production process, that is, the interaction between the number of keystrokes produced during the process and the number of keystrokes that the product contains, text movements, and consultation of sources outside the TT environment. The general file and process graph, in combination with an analysis of markers on the ST paper copies (e.g., handwritten notes, schematic overviews, arrows) and the researcher’s observational notes constituted the primary sources with which to identify strategies and, if possible, certain process commonalities between students. A qualitative process analysis of each participant was carried out using the annotation scheme presented in Table 1.

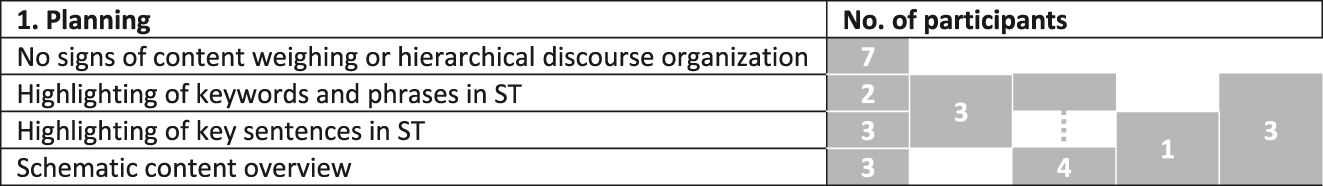

Annotation scheme of the planning, TT production, and revision strategies used in the summarizing translation processes.

| 1. Planning | 2. TT production | 3. Revision |

|---|---|---|

| No signs of content weighing or hierarchical discourse organization | “Full” translation of ST paragraphs | Online revision involving substantial content deletion and/or TT word count reduction |

| Highlighting keywords and phrases in ST | Literal and linear translation of previously highlighted phrases and sentences | Online revision primarily focused on TT accuracy and adequacy rather than content deletion and/or TT word count reduction |

| Highlighting key sentences in ST | Paraphrasing translation of previously highlighted phrases and sentences | End revision primarily focused on content deletion and/or TT word count reduction |

| Schematic content overview | Literal and linear translation of a selection of ST phrases and sentences | End revision primarily focused on TT accuracy and adequacy |

| Paraphrasing translation of a selection of ST phrases and sentences | ||

| Filling-in or elaboration of schematic content overview |

4 Results and discussion

In translation process research, the translation process is generally divided into three phases: (1) pre-writing phase; (2) writing phase; (3) post-writing (or revision) phase. In Sections 4.1 and 4.2, the summarization that could be observed in the pre-writing and writing phases respectively is discussed; the summarization in online and/or end revision is the topic of Section 4.3.

4.1 Summarization taking place during the pre-writing phase

The first phase of the translation process is called the pre-writing stage (Jääskeläinen 1999), the pre-writing phase (Englund-Dimitrova 2005), or the initial orientation phase (Jakobsen 2003). Englund Dimitrova (2005: 86) provides the following definition of the pre-writing phase: “[it] begins when the participant has received the ST and the oral information about the translation brief, and finishes when the participant starts to write down the TT as an integral text. Making notes about word meanings etc. while reading the ST for the first time is not considered as a start of the writing phase.” In the present study, the average duration of the pre-writing phase was 13.38 % [range: 0.98–65.32 min] of the total process time.

Although the students were provided with an electronic and a paper copy of the ST, most of them used the latter, on which they highlighted sentences, phrases, and words and made notes. These activities were not registered by Inputlog but could be reconstructed through the triangulation of the researcher’s observational notes, analysis of the handouts, and instances in the keystroke logging data where “nothing” happened. As shown in Table 2, the logging data, paper copies of the ST, and observational notes of 7 out of the 26 students revealed no discernible indications of weighing ST content units or the creation of a discourse hierarchy during the pre-writing phase. In contrast, the other 19 students displayed behaviour that could indicate relevant content selection and/or hierarchical discourse organization, sometimes even combining different strategies.

Frequency of content weighing strategies and hierarchical discourse strategies in the pre-writing phase.

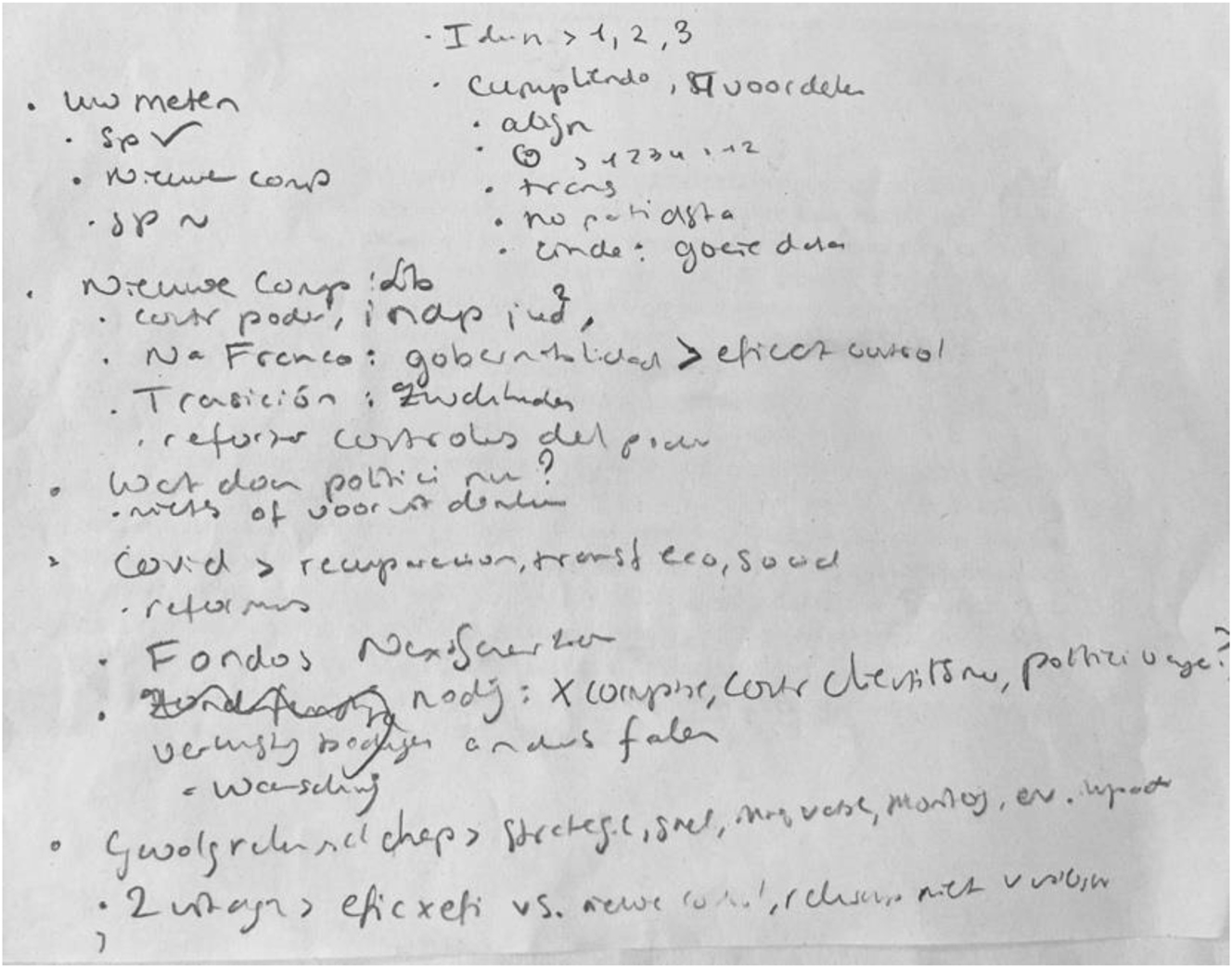

Of these 19 students, 11 developed a schematic outline of the content units that should be featured in the TT, to varying degrees of detail (see Figure 1 for an example, in which the student anticipates 7 paragraphs in the Dutch TT, almost all of them with a number of talking points). Ten of these 11 students drafted this schematic outline in the target language.

TT outline drafted in the pre-writing phase.

Of these 11 students who drafted a schematic outline, three developed the content outline without highlighting ST elements while reading the ST, whereas eight others adopted this planning strategy after having highlighted ST keywords and phrases (four students; see Figure 2 for an example) or entire ST sentences (one student; see Figure 3 for an example).

Highlighting of ST keywords and phrases in the pre-writing phase.

Highlighting of ST sentences in the pre-writing phase.

Three students employed a combination of strategies: they highlighted keywords, phrases (including discourse markers), and entire sentences in the ST, and manually recorded the main ideas of each paragraph in the ST margin, followed by drafting a concise schematic overview of the TT content in MS Word (see Figure 4 for an example).

Highlighting ST keywords, phrases, and sentences in the pre-writing phase.

The eight students who did not draft a TT outline performed semantic reduction by highlighting elements in the ST. While the systematic highlighting of entire sentences was slightly more common (three students) than that of keywords and phrases (two students), there were also instances (three students) where both strategies were employed.

Whereas the highlighting of keywords and phrases suggests that salient ST content-detection and weighing took place, it cannot be ruled out, based on the data-collection methods used, that those students who highlighted sentences or words, phrases, and sentences actually used the highlighting strategy as a means of comprehending the ST content in depth. Yet the use of different colours for highlighting shown in Figure 4 might indicate both content weighing and hierarchical discourse organization: the discourse markers are underlined in blue, the (numerical) details are underlined in green, the main points are signalled by a red line, and there is also a consistent use of purple (enumerations). The pre-writing phases of “full translation” processes may entail this strategy, but do not generally do so. The same is true for the TT outline strategy, yet it is a typical planning strategy observed in writing research. Previous research by Galbraith et al. (2005) and Kellogg (1988, 1994) has suggested that drafting an outline before writing enables writers to execute higher-level problem-solving more effectively than doing so without pre-planning; and that it is consequently typically associated with the production of higher-quality texts. As is shown in Section 4.2, these ST markings and TT outlines appear to have served as cognitive artefacts, “physical objects made by humans for the purpose of aiding, enhancing, or improving cognition” (Hutchins 1999: 126). They help to perform the cognitive task of TT production, serving as a memory cue and/or a guide as to which content to integrate into the TT.

4.2 Summarization taking place during the writing phase

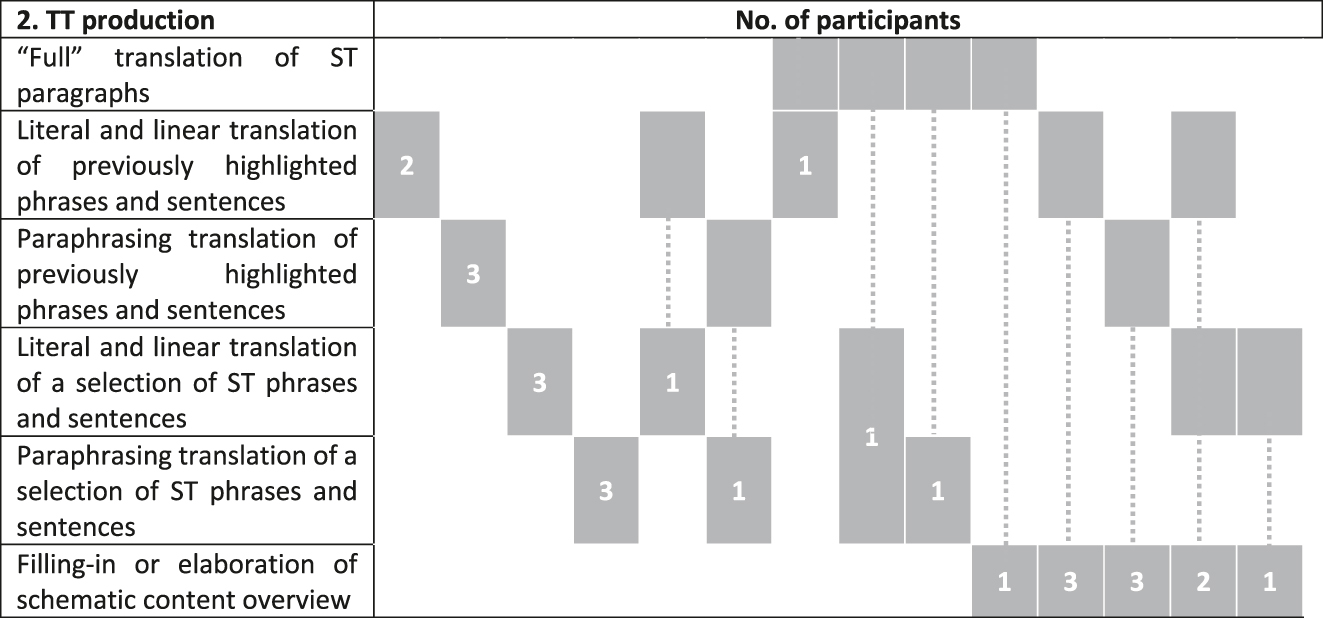

The writing phase of the translation process “begins when the participant starts to write down the TT and finishes when (s)he has written down an integral version of it” (Englund Dimitrova 2005: 86). As shown in Table 3, a minority of the students – 11 out of 26 – used a single TT production strategy consistently throughout the writing phase. However, most of the students combined several strategies for TT production, even though they did have a specific strategy as a starting point (e.g., translating the first ST paragraphs in full or using the TT outline they had previously drafted).

Frequency of drafting strategies in the writing phase.

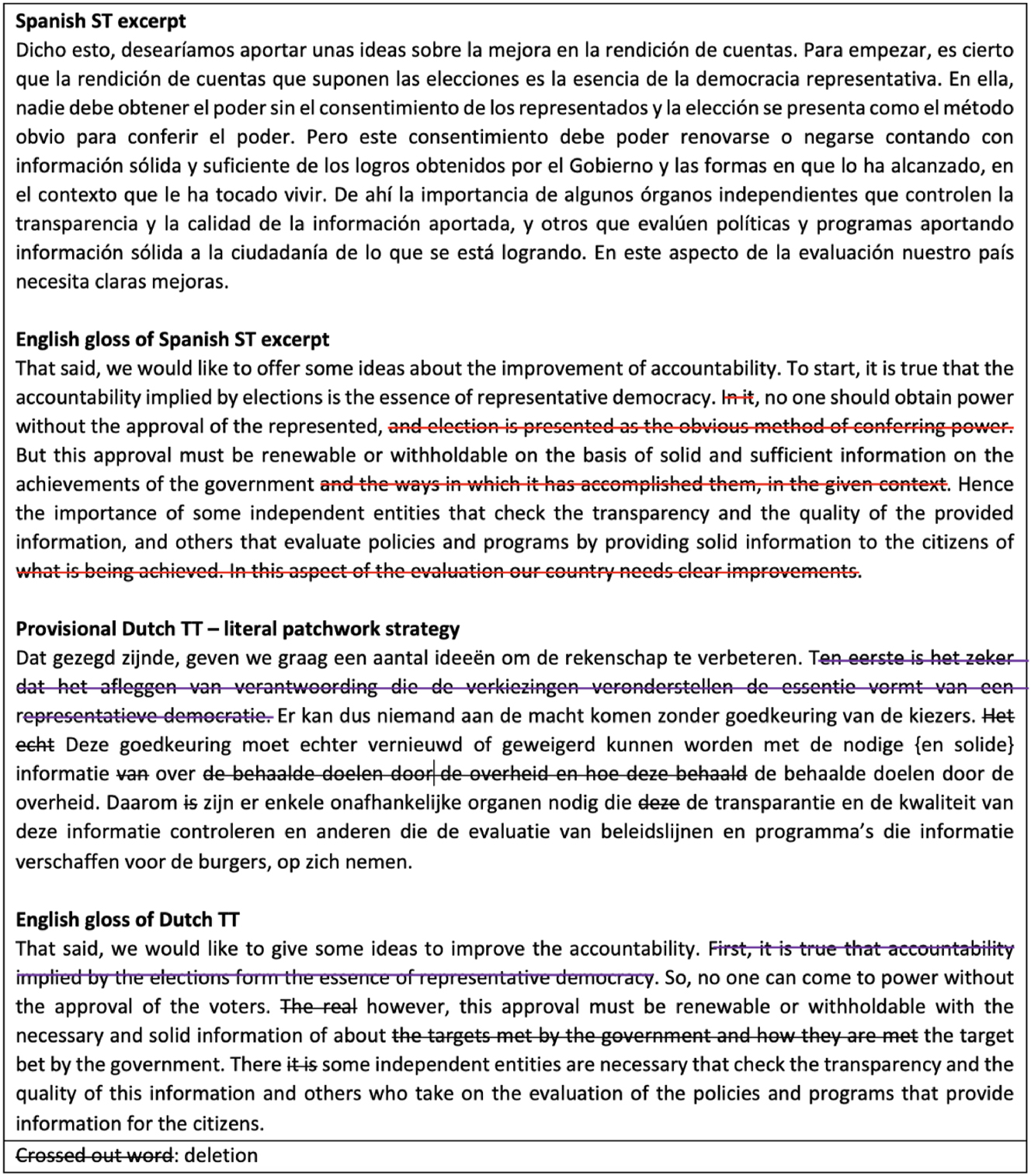

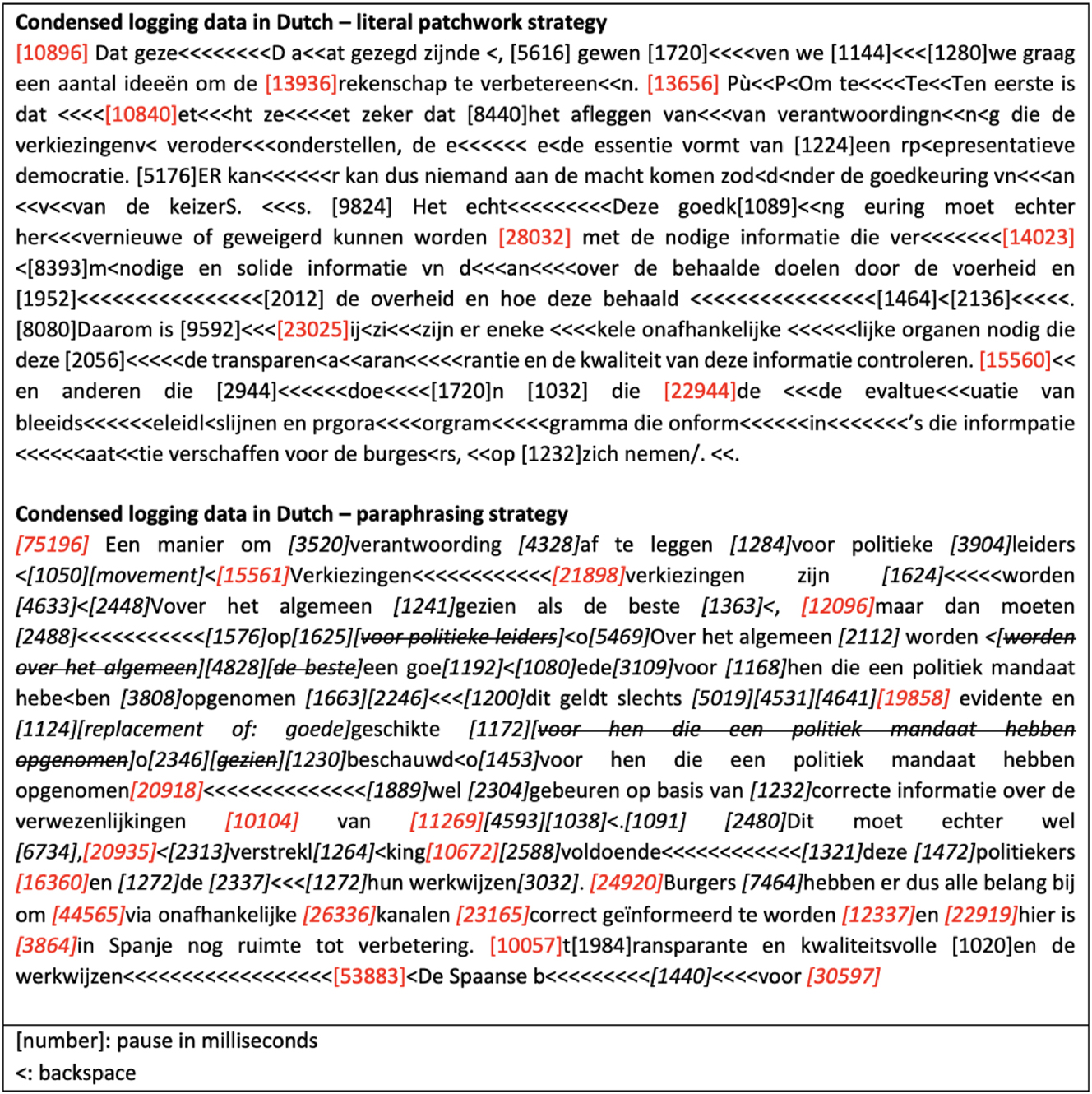

The students who used a single TT production strategy differed in the strategy they opted for: some used literal patchwork translation, while others used paraphrasing. The literal patchwork translation strategy entails employing a default literal translation strategy for ST sentences and/or specific words and for phrases from one or multiple ST sentences and combining these to form a coherent TT sentence. The translation and integration of ST units is generally approached in a linear manner, following the order of ST sentence(s). Seldom are units from different ST paragraphs combined in a single TT sentence or paragraph. As shown in Figure 5, this literal patchwork strategy implies omitting certain words and/or phrases from the ST sentence. These are represented by the units crossed out with the red line in the English gloss of the Spanish ST excerpt in Figure 5. The remaining ST words and phrases are then translated in a literal manner. Occasionally, additional semantic reduction by way of deletion can be observed when the students revised the TT sentence they had just produced, as is the case in Figure 5 with “and how they are met”, and/or when they revised the TT paragraph they had just drafted, as illustrated by the revision represented by the purple line.

Example of the literal patchwork strategy.

The words, phrases, and sentences that were translated literally were in almost all cases those that the students had highlighted if they had used the highlighting strategy during the pre-writing phase. This suggests that there was an interplay between the planning and the TT production strategies. Only four out of the 16 students who had used the highlighting strategy translated additional ST items that they had not highlighted before.

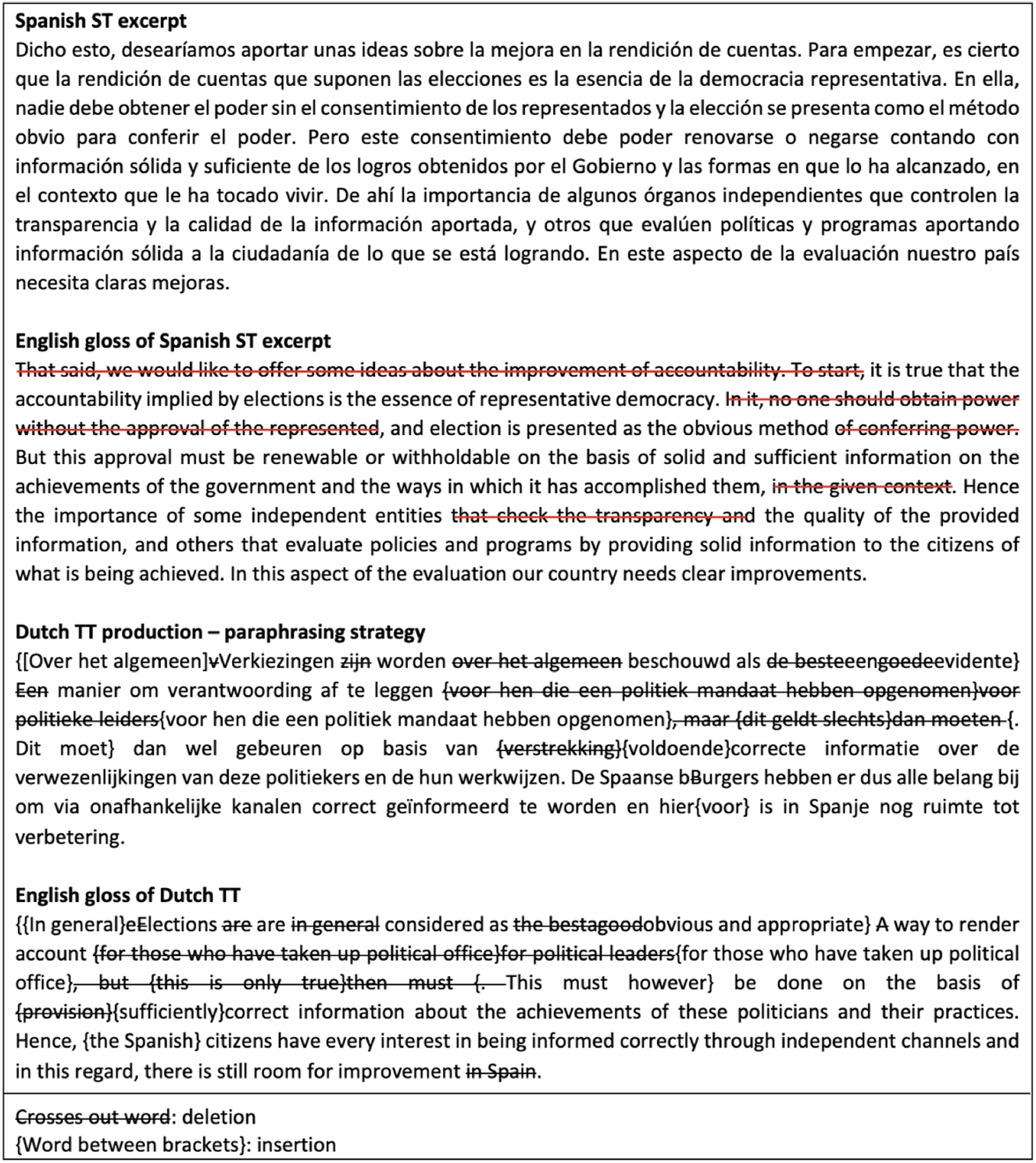

The other frequently employed TT production strategy was paraphrasing: here, the translator verbalizes the ST in their own words in the target language. This strategy implies not only translating the ST content less literally but also integrating content from the ST units in a less linear way, jumping back and forth in the same ST paragraph or even between ST paragraphs.

As illustrated by the example in Figure 6, summarization via paraphrasing may encompass several strategies:

the omission of ST units, as represented by the red lines;

linguistic reduction via generalization, as occurs, for example, with “this must however be done”, instead of the literal translation “must be renewed or withholdable”, or “their practices” versus “the ways in which it has accomplished them”;

linguistic expansion, as can, for example, be observed in “the Spanish citizens have every interest in being informed” instead of the more literal option, “the importance of”;

construction, which is described by Shreve (2006) as creating new macro-propositions from longer sequences of propositions. This is exemplified by “elections are considered as an obvious and appropriate way to render account for those who have taken up a political office”, which is constructed based on “the accountability implied by elections”, “representative democracy”, and “election is presented as the obvious method”.

Example of the paraphrasing strategy.

The paraphrasing strategy often involves a more pronounced focus on TT cohesion. In the example shown in Figure 6, the translation student in question established cohesion with the final sentence of the preceding TT paragraph, which had emphasized the necessity of implementing control mechanisms that strengthen rather than paralyse government. Moreover, this immediate foregrounding of elections helped her to ease into an explanation of the accountability model proposed by the ST author. This highlighted the need for accurate information about the government’s feats, albeit without explicitly stating that the ST author has some ideas for improving the political accountability methods (as indicated in the first sentence of this ST paragraph).

The paraphrasing strategy, especially when employed in combination with the outline planning strategy, might to a certain extent resemble the knowledge-constituting strategy found in writing research, whereas the literal patchwork strategy might hint at a knowledge-telling strategy (Bereiter and Scardamalia 1987). As explained by Baaijen and Galbraith (2018): “Knowledge-telling involves the linear production of ideas in the order that they are retrieved from memory and the spontaneous translation of these ideas into words. Knowledge-transforming, by contrast, involves modifying the order in which ideas are produced, and deliberating over how to formulate these ideas to satisfy rhetorical goals”. In the present study, the highlighted ST units appear to have served as memory cues; and when the literal patchwork translation strategy was adopted, the ideas represented in these units were produced linearly and without semantic transformation, resembling knowledge-telling. In contrast, those students who started from a TT outline and paraphrased the (previously highlighted) ST units seemed to evaluate, reorganize, and rephrase these ideas to satisfy rhetorical goals, as writers whose approach is characterized as following a knowledge-constituting strategy do. The decision to adopt a literal patchwork translation strategy or a paraphrasing strategy might have been influenced by the way the translation students perceive summarizing translation, how static or dynamic their concept of translation is, and/or the way they conceptualize their role as translator (Chodkiewicz 2020).

A comparison of the pausing behaviour pertaining to the examples above provides some insights into how cognitively demanding each strategy might be. As shown in Figure 7, the TT production by the student employing the literal patchwork strategy is characterized by frequent short and longer pauses (30 in total; predefined pause threshold of 1,000 ms), the latter primarily preceding clauses and sentences and the former preceding lower-level units such as phrases and words, or following them in the case of typos. This is a typical pausing pattern previously found, for example, by Immonen and Mäkisalo (2010) and Puerini (2023). The student employing the paraphrasing strategy follows the same pattern but pauses much more frequently (74 times in total) and the number of pauses of more than 10,000 ms (highlighted in red in Figure 7) are more frequent too. Although the TT production of the student employing the literal patchwork translation strategy is not completely linear due to the many typo corrections, the non-linearity of the drafting process of the other student is more substantial: there is more iterative online revision within sentences. These indicators seem to suggest that the paraphrasing strategy is more cognitively demanding than the literal patchwork strategy. However, more in-depth quantitative analysis of pauses and text-production bursts is necessary to establish whether this is indeed a characteristic difference between the two strategies or rather idiosyncratic of these two translation students.

Pausing in keystroke logging data of literal patchwork translation strategy and paraphrasing strategy.

Not all of the students immediately summarized the ST content in their writing phase. In fact, the TT production strategy typically found in translation process research, in which translators translate entire ST paragraphs in a linear fashion – starting with the first paragraph, then the second, the third and so on – could be observed partially in the writing phase of four students as they translated all of the sentences of several ST paragraphs. It appears that these students, after having employed this strategy for several ST paragraphs (the first 2, 4, 6, and 7 paragraphs, respectively), recognized its time-intensive nature, which prompted them to change their strategy. The rationale behind this shift cannot be inferred from the available data, but the increasing semantic complexity of subsequent ST paragraphs and/or the dwindling task time might have been influential factors.

During the writing phase, nine students used the schematic TT content overview as a starting point for their TT production. Seven either “filled in” the TT outline or initiated TT production based on the outline by translating previously highlighted words, phrases, and/or sentences in a predominantly literal manner (three students) or through paraphrasing (three students). Two other students adopted a default literal translation approach for the ST units that they had highlighted in the ST and their concise TT outline, but also applied the same strategy for other previously unselected ST elements. The student who had not highlighted any ST units during their ST reading but had developed a detailed schematic overview of the ST ideas that should be included produced the TT based on this outline. Then, during the TT production, they transformed the outline items into full sentences while omitting certain content points. Since these TT sentences correspond to a literal translation of certain ST sentences, it is likely that during this verbalization stage this student also used the ST, although this cannot be verified using the available data.

From the previous results it can be deduced that there is a certain interaction between the planning and the TT production strategies. As shown in Table 4, 12 of the 16 students who had used the highlighting strategy in the pre-writing phase translated the highlighted ST units during the writing phase. However, no clear preference could be observed for the literal patchwork strategy or the paraphrasing strategy among these students who had shown signs of content weighing and/or hierarchical discourse organization in the pre-writing phase. Four of them also translated additional ST items. These four differed in the type of ST units they had highlighted. Moreover, three of them translated the previously highlighted ST units in a literal patchwork manner, whereas the other preferred the paraphrasing strategy.

Frequency of planning and TT production strategy combinations.

| Planning | TT production | No. of participants |

|---|---|---|

| Highlighting keywords and phrases in ST | Literal and linear translation of previously highlighted keywords and phrases + literal and linear translation of a selection of ST phrases and sentences |

|

| Highlighting keywords and phrases in ST | Paraphrasing translation of previously highlighted keywords and phrases |

|

| Highlighting key sentences in ST | Literal and linear translation of previously highlighted sentences |

|

| Highlighting key sentences in ST | Paraphrasing translation of previously highlighted sentences |

|

| Highlighting key sentences in ST | Paraphrasing translation of previously highlighted sentences + paraphrasing translation of a selection of ST phrases and sentences |

|

| Highlighting keywords, phrases + sentences | “Full” translation of ST paragraphs + literal and linear translation of previously highlighted keywords, phrases and sentences |

|

| Highlighting keywords, phrases + sentences | Literal and linear translation of previously highlighted keywords, phrases and sentences |

|

| Highlighting keywords, phrases + sentences | Paraphrasing translation of previously highlighted keywords, phrases and sentences |

|

| Highlighting keywords and phrases in ST + schematic content overview | Literal and linear translation of previously highlighted keywords and phrases + filling-in or elaboration of schematic content overview |

|

| Paraphrasing translation of previously highlighted keywords and phrases + filling-in or elaboration of schematic content overview |

|

|

| Literal and linear translation of previously highlighted keywords and phrases + literal and linear translation of a selection of ST phrases and sentences + filling-in or elaboration of schematic content overview |

|

|

| Highlighting key sentences in ST + schematic content overview | Literal and linear translation of previously highlighted sentences + filling-in or elaboration of schematic content overview |

|

| Highlighting keywords, phrases + sentences + schematic content overview | Paraphrasing translation of previously highlighted keywords, phrases and sentences + filling-in or elaboration of schematic content overview |

|

| Literal and linear translation of previously highlighted keywords, phrases and sentences + literal and linear translation of a selection of ST phrases and sentences + filling-in or elaboration of schematic content overview |

|

The same is true for the four students who started their writing phase by translating several ST paragraphs “in full”. Two of them had not displayed any content weighing behaviour, such as highlighting, during the pre-writing phase. This implies that they may initially have deliberately postponed semantic reduction to a later stage (i.e., to the end revision). When they altered their approach during the writing phase, one of these students adopted a hybrid approach, switching between literal translation and paraphrasing for specific phrases and sentences, whereas the other student opted resolutely to paraphrase. In contrast, the other two students had exhibited semantic reduction behaviour prior to TT production, with one highlighting ST keywords, phrases, and sentences and the other drafting a TT outline. However, it can be argued that these strategies, which were initially considered to be planning strategies, could rather have served as comprehension strategies, since these students proceeded to translate the first six and seven paragraphs in full. To formulate the remaining TT paragraphs, both students adopted a literal patchwork strategy by translating ST phrases and sentences that they had previously highlighted or by simply integrating what they had already written in the content overview, respectively.

As stated in Section 4.1, 11 of the students had displayed an outline planning strategy, but only nine of them later used the TT outline in their writing phase. The two students who did not use the TT outline they had previously produced displayed different behaviour. One of them started translating the ST in full; the other had drawn up an extremely concise TT content overview, characterized by unclear cohesion between prominent content features and a mixture of source-language and target-language words. Moreover, entire paragraphs were not integrated in this outline. The quality of the outline (or the lack of it) may have prompted the student to re-initiate the ST content selection from scratch. Indeed, he proceeded by copy-pasting the ST in MSWord and started to transfer specific ST phrases and sentences into the target language, using a default literal translation strategy and deferring further content reduction by way of deletions in the end revision phase.

The seven students who did not exhibit any ST-content weighing behaviour in the planning phase also varied considerably in their drafting strategies. As mentioned above, two of these students started translating the first ST paragraphs in full, subsequently adopting either a literal translation strategy or a combined literal–paraphrasing approach. Among the remaining five students, three produced the TT using the paraphrasing strategy and verbalizing parts of the ST in their own words. They integrated content units from various ST sentences into highly idiomatic propositions in the target language, continually refining the TT formulation to ensure cohesion and coherence between sentences and paragraphs. In contrast, the other two students focused on specific ST phrases and translated them literally, with minimal attention being given to cohesion between propositions.

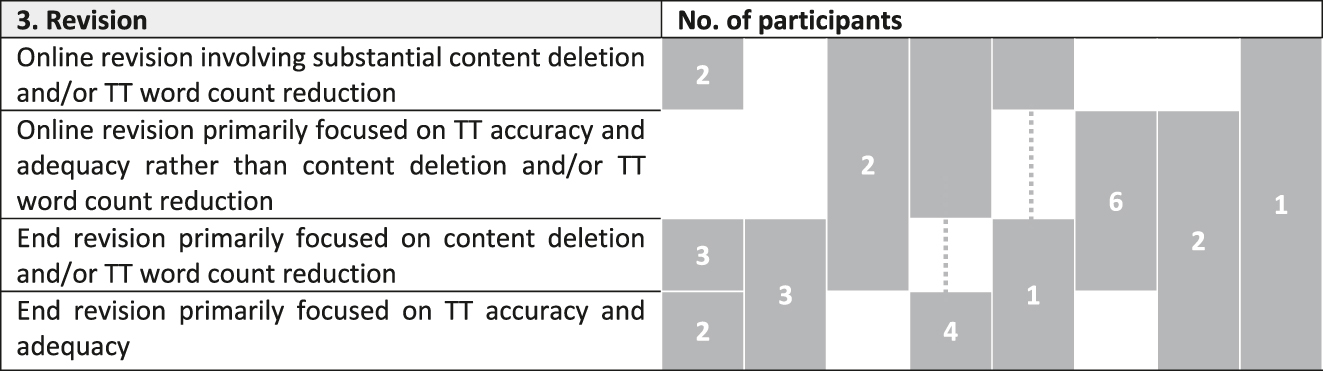

4.3 Summarization taking place during revision

The post-writing phase, which starts immediately after the writing phase and finishes when the participant ends the Inputlog logging session, is characterized by self-revision of the TT (Englund Dimitrova 2005). However, self-revision is not limited to this phase; it can also be performed during the writing phase of the TT produced so far (i.e., online revision) (Dragsted and Carl 2013). In fact, the examples illustrating the literal patchwork strategy and the paraphrasing strategy (Figures 5 and 6) have shown that summarization may also take place during online revision, primarily in the form of deletion. In the case of this study, it is therefore important to consider online revision as entailing ST semantic reduction and/or TT word-count reduction.

As shown in Table 5, 18 out of 26 student translators indeed already engaged in substantial revision during TT production. Of these 18 students, 16 also did end revision, whereas the remaining two did not (with the subsequent absence of a post-writing phase). In contrast, eight students exhibited extensive revision behaviour exclusively in the post-writing stage of the translation process. The revisions captured in the logging data suggest that half of the students (13 out of the 26) had a double revision focus when they were revising their TT during the writing phase or the post-revision phase, namely, both on summarizing (mainly aimed at TT reduction) and on possible ST interpretation and TT formulation considerations (e.g., spelling mistakes).

Frequency of online and end revision strategies.

Among the 18 students who engaged in substantial revision during the writing phase, 10 engaged in semantic reduction by deleting a significant number of TT propositions. Seven of them combined this online revision focus on deletion with dealing with matters related to ST interpretation and TT formulation. No clear preference was observed in the TT production and online revision strategies that were adopted: five of those 10 students who focused on reducing the TT word count by way of deletion in their writing phase had employed the literal patchwork strategy (exclusively or in combination with the “full” translation strategy or the strategy of filling in the TT outline); the other five students had used the paraphrasing strategy.

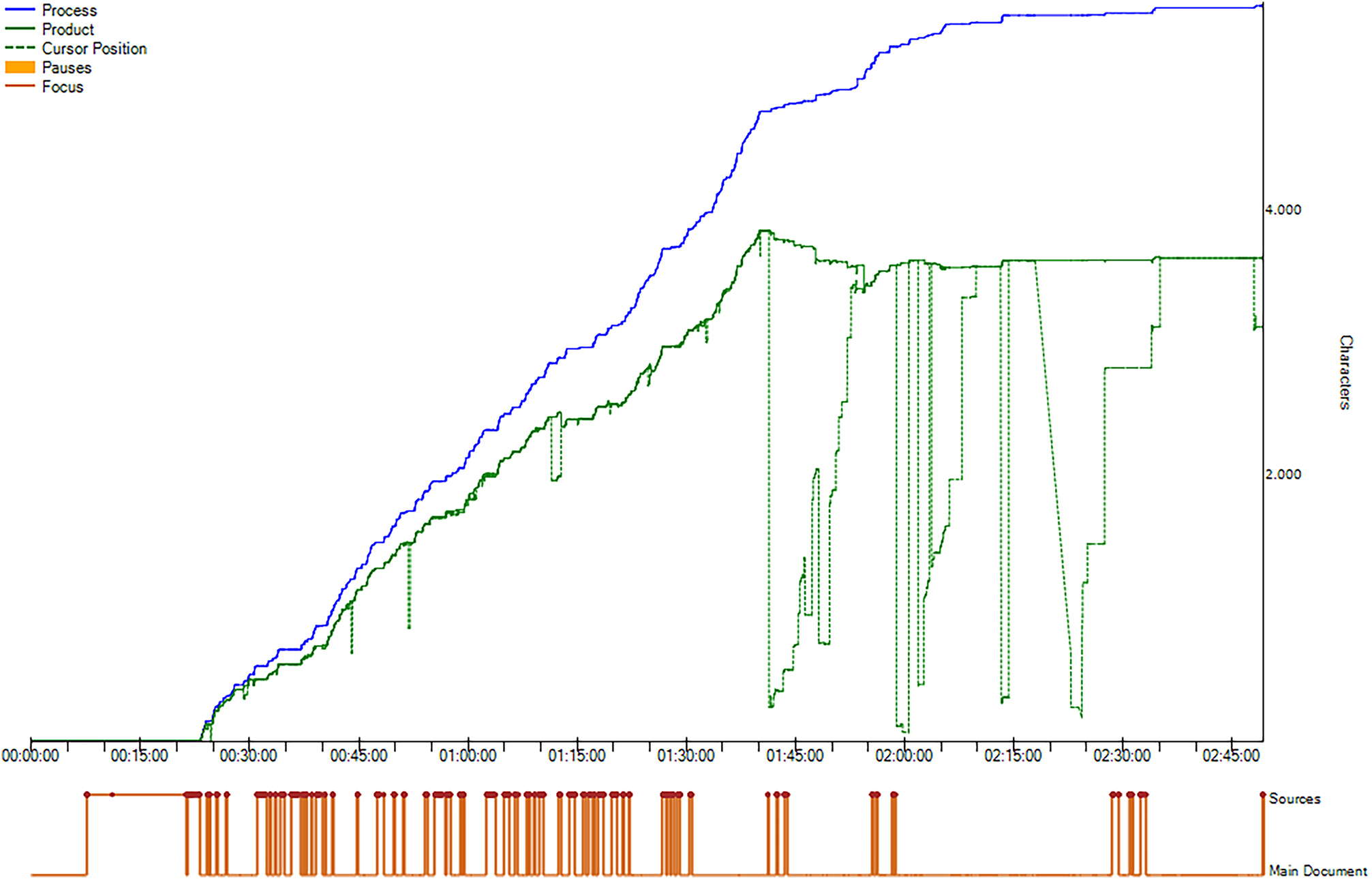

Sixteen of the 18 students who engaged in online revision also conducted one or more rounds of end revision. Among them, 12 students also engaged in summarization in the post-writing phase. In fact, most of them engaged in multiple rounds of end revision, each round focused exclusively on a specific issue. Figure 8 shows an example of a translation process with multiple rounds of end revision. In Figure 8, the post-writing phase starts at about 1h40, as is observable in the drop of the dotted green line (representing cursor movements); this means that the student moved from the end of the TT to the beginning. It is also observable in the slight decrease in the solid green line, which suggests the deletion of TT characters. An interpretation of the solid and dotted green lines indicates that multiple revision rounds can be observed after 1h40 – the first and third of which were concentrated on shortening the TT to adhere to the prescribed word count. Conversely, the second loop seemed to prioritize the idiomatic expression of the TT, albeit with fewer revisions having been conducted compared to those in the initial revision loop.

Process graph of summarizing translation process with several end revision rounds.

In contrast, four students had already focused on deletion during online revision and concentrated instead on revising the ST interpretation and TT formulation matters during the post-writing phase. Two of them were literal patchwork translators, the other two paraphrased consistently during the TT production.

A similar finding was observed for the eight students who engaged exclusively in end revision: three focused on both TT reduction and revision, whereas three primarily deleted TT items while continuously monitoring the TT word count. Interestingly, those three students who focused exclusively on TT reduction in the post-writing phase had all employed the literal patchwork translation strategy (exclusively or together with the “full” translation strategy or the strategy of filling in the TT outline). No clear preference in TT production and revision strategy combinations could be established for the other three, who did not focus on summarization in their end revision. The same is true for the remaining two students, who focused exclusively on resolving ST interpretation and TT formulation problems in their end revision.

5 Conclusions

Research into summary translation is rare, the exception being Shreve’s 2006 product-based study. The present study was a qualitative micro-cognitive exploration of summarizing translation processes; it focused on the way summarization takes place during the different process phases. The analysis of the keystroke logging data, observational notes, and ST paper copies suggests that many roads lead to Rome in summarizing translation tasks: there is considerable variety in the strategies employed during the pre-writing, writing, and post-writing phases. Most of the students showed signs of detecting and assessing the salient ST content by way of highlighting ST units before initiating the TT draft, but the degree of elaboration varied considerably among them. Outline planning, which is uncommon in traditional “full translation” processes but frequently found in writing processes, could also be observed in this study; this suggests that summarizing translation might cognitively resemble writing. Moreover, the ST markings and the draft of the TT outline may have served as cognitive artefacts (Hutchins 1999), because these seemed to influence significantly the way this cohort of students approached the writing phase. A certain interaction between planning and TT production strategies could be observed, since most of those who employed the highlighting strategy tended to prioritize and take these elements as a starting point when formulating their TT. However, the way in which they translated these ST units varied: some students employed a literal patchwork strategy by translating various ST units literally and employing connectors to link them together; in contrast, others opted for a more distanced approach from the ST, paraphrasing the essence of the ST message in their own words. The same is true for those students who drafted a TT outline in the pre-writing phase: most of them used this outline to guide their TT drafting, but some showed themselves to be literal patchwork translators whereas others preferred the paraphrasing strategy. The pausing data seem to suggest that the paraphrasing strategy might be more cognitively demanding than the literal patchwork translation strategy, but further quantitative research is needed to examine this in detail. Summarization may also take place during online revision, primarily through deletion. Although an exclusive focus on summarization in online revision was seldom observed, most of the students engaged (solely) in TT content deletion and/or reduction in their post-writing phase in order to adhere to the TT word count. No clear preference could be observed in the combination of the drafting and revision strategies the students adopted.

This study has not been without its limitations, which should be considered when evaluating the results. The primary limitation is the relatively small sample size of 26 participants. Whereas this exceeds the number of participants commonly used in micro-cognitive translation process studies, it remains insufficient to enable broad generalization of the findings. Another limitation of this study is that the participants were translation students rather than professional translators. A third limitation concerns the single text and the single language combination that were studied. While summary translation can be performed on a single text, it might be worthwhile to focus in future research on multiple texts in various source languages, which will enable further comparisons to be made regarding the cognitive aspects of source-based writing.

Despite its limitations, though, the present study is a first step towards unveiling the cognitive processes that underlie summarizing translation. It has revealed that there can be variety in the strategies that are employed in the various phases of summarizing translation processes in addition to indicating the resemblance of some of those strategies to the strategies found in writing and research on writing. Future research might include the quantitative analysis of pauses and revisions plus signs of non-linearity and the use of external resources to provide us with greater insight into that cognitive processes which take place during summarizing translation. Such an analysis, together with a more fine-grained analysis of the summarization taking place during TT drafting, might enable distinct process profiles to be identified. Additional data-collection methods, such as think-aloud or retrospective interviews, could yield additional insights. Such insights could include those into the nature of specific strategies (e.g., whether highlighting is used as a content-weighing and/or a comprehension strategy), into cognitive control (e.g., the deliberate postponement of deletion to the post-writing phase), and into the manner in which beliefs about (summarizing) translation influence the employment of a strategy.

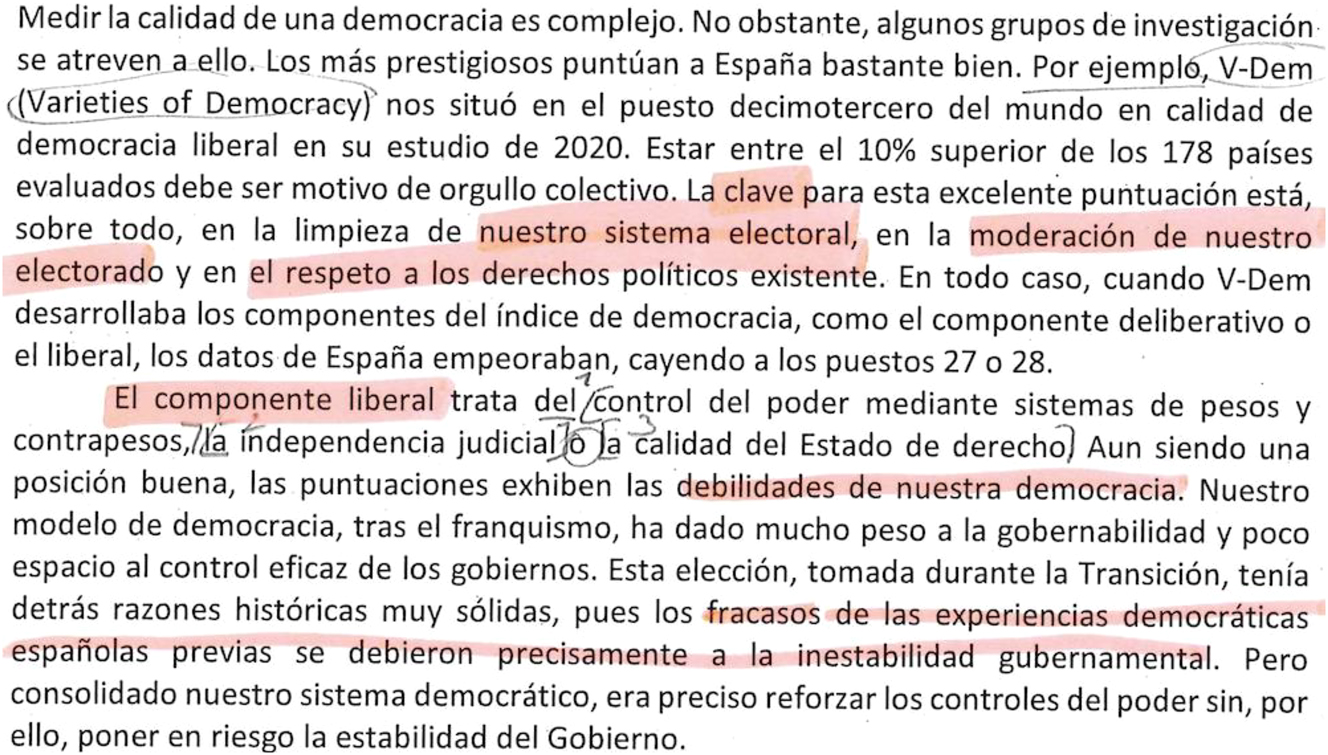

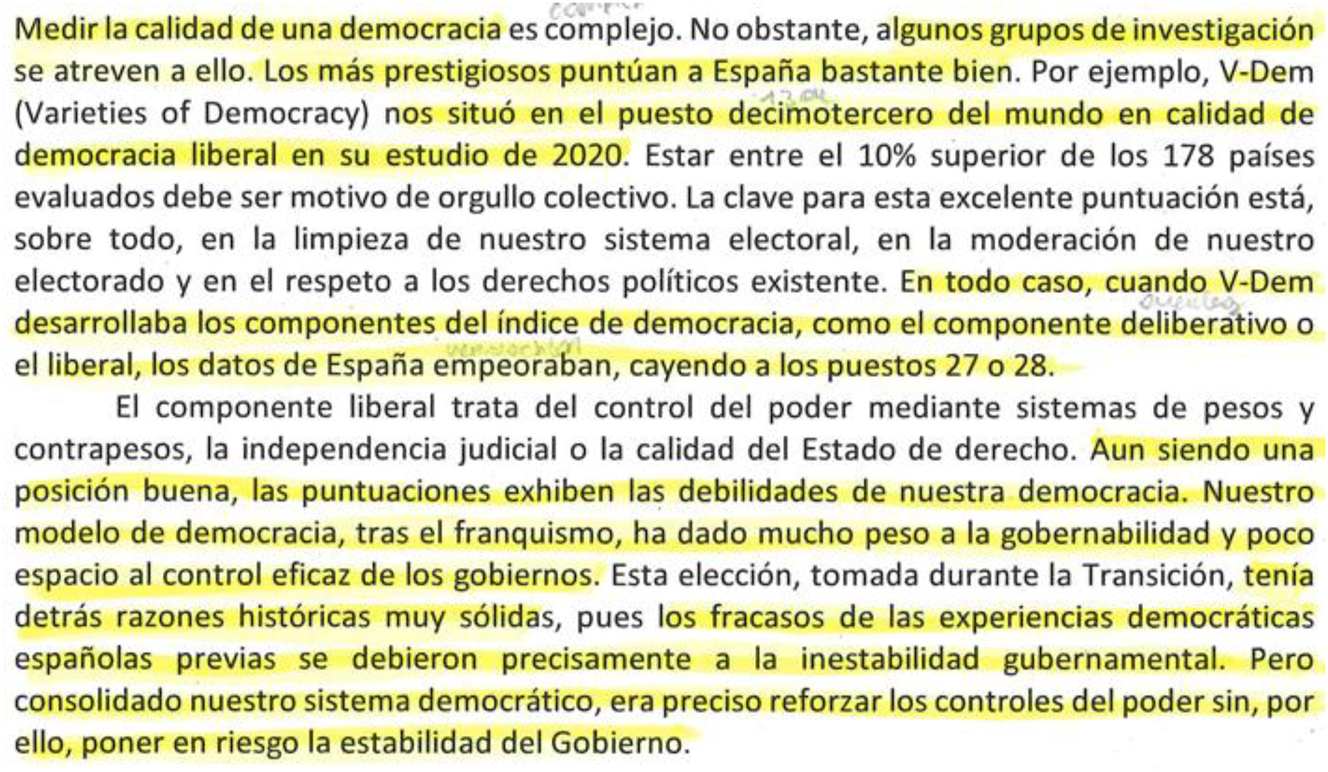

Appendix I: Source text

RENDIR CUENTAS PARA TRANSFORMAR Y RENOVAR ESPAÑA

Manuel Villoria Mendieta

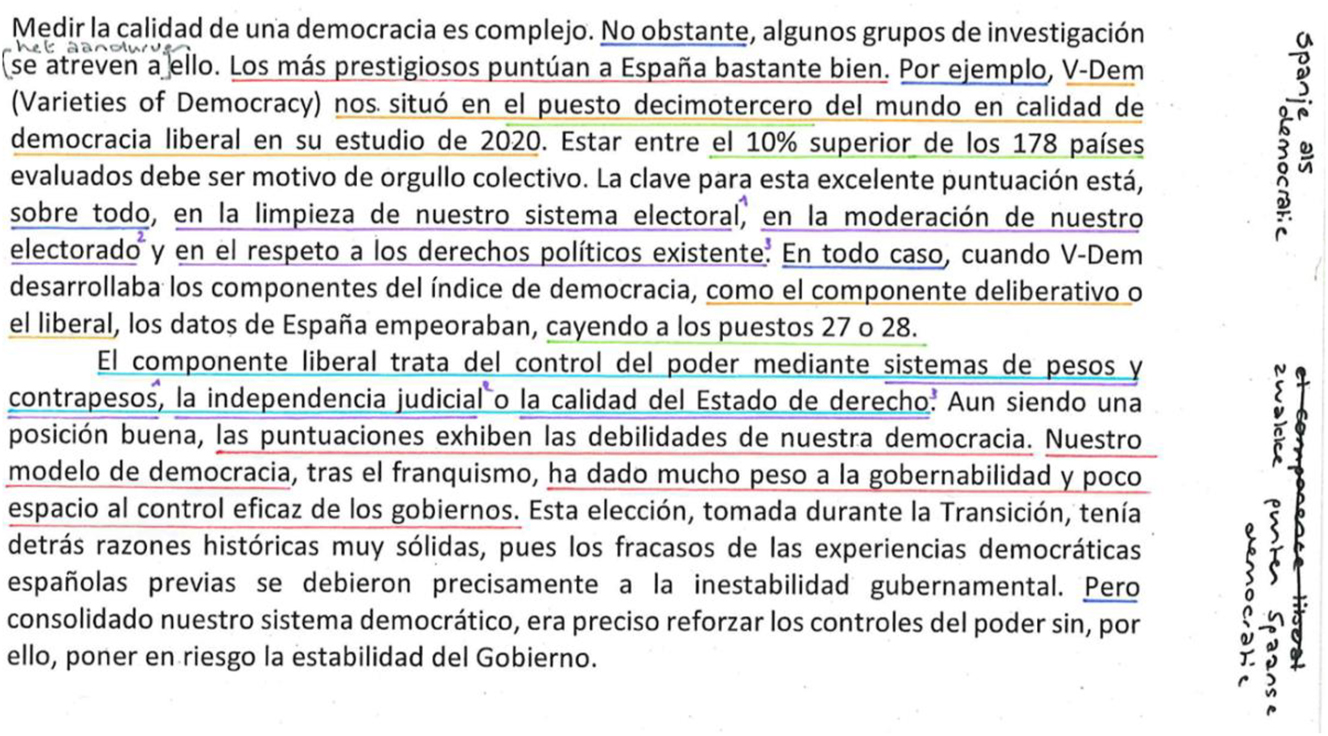

Medir la calidad de una democracia es complejo. No obstante, algunos grupos de investigación se atreven a ello. Los más prestigiosos puntúan a España bastante bien. Por ejemplo, V-Dem (Varieties of Democracy) nos situó en el puesto decimotercero del mundo en calidad de democracia liberal en su estudio de 2020. Estar entre el 10 % superior de los 178 países evaluados debe ser motivo de orgullo colectivo. La clave para esta excelente puntuación está, sobre todo, en la limpieza de nuestro sistema electoral, en la moderación de nuestro electorado y en el respeto a los derechos políticos existente. En todo caso, cuando V-Dem desarrollaba los componentes del índice de democracia, como el componente deliberativo o el liberal, los datos de España empeoraban, cayendo a los puestos 27 o 28.

El componente liberal trata del control del poder mediante sistemas de pesos y contrapesos, la independencia judicial o la calidad del Estado de derecho. Aun siendo una posición buena, las puntuaciones exhiben las debilidades de nuestra democracia. Nuestro modelo de democracia, tras el franquismo, ha dado mucho peso a la gobernabilidad y poco espacio al control eficaz de los gobiernos. Esta elección, tomada durante la Transición, tenía detrás razones históricas muy sólidas, pues los fracasos de las experiencias democráticas españolas previas se debieron precisamente a la inestabilidad gubernamental. Pero consolidado nuestro sistema democrático, era preciso reforzar los controles del poder sin, por ello, poner en riesgo la estabilidad del Gobierno.

Los avances en este ámbito han existido, sin duda, pero a unos niveles de desarrollo que no han conseguido evitar una profunda desafección ciudadana. Ante esta situación, los responsables políticos pueden situarse en el confort de ver que la democracia en general funciona y no hacer nada o, por el contrario, anticiparse a los deterioros que nuestras debilidades generan y generarán y construir un modelo de rendición de cuentas acorde a la calidad que los otros componentes del índice de democracia demuestran.

Todo ello, además, en un momento clave para nuestro país, pues tras la tragedia de la COVID-19 es el momento de la recuperación y transformación económica y social; una recuperación para la que se han generado 212 medidas, con 110 grandes inversiones y 102 reformas, que movilizarán 70.000 millones de euros en inversiones públicas entre 2021–2023. Los fondos europeos Next Generation nos aportan gasolina para la recuperación, pero es preciso, al tiempo, preparar el vehículo para este difícil viaje.

No es catastrofista sostener que, sin reducir las posibilidades de corrupción, sin controlar fuertemente el clientelismo, sin evitar la captura interesada de las políticas y sin domeñar el despilfarro, esos fondos tienen grandes posibilidades de fracasar en el cumplimiento de sus fines. Al contrario, es una advertencia sensata y basada en cifras y hechos bien documentados del pasado reciente.

En consecuencia, reforzar la rendición de cuentas sin, por ello, paralizar el Estado es una de las medidas de resiliencia esenciales que nuestro país tiene que afrontar. Tenemos una Administración que ha ayudado a alcanzar muchos logros, pero que presenta debilidades serias ante un mundo profundamente complejo, dominado por tecnologías disruptivas y, en el caso español, como consecuencia de la pandemia, sometido a una prueba de resiliencia que exige visión estratégica, celeridad en la gestión, innovación, monitoreo permanente y evaluación de los impactos. En suma, que el reto es doble: por una parte, reforzar la eficacia y la eficiencia; por otra, consolidar nuevas formas de control y rendición de cuentas que refuercen el Estado de derecho y, al tiempo, no paralicen.

Dicho esto, desearíamos aportar unas ideas sobre la mejora en la rendición de cuentas. Para empezar, es cierto que la rendición de cuentas que suponen las elecciones es la esencia de la democracia representativa. En ella, nadie debe obtener el poder sin el consentimiento de los representados y la elección se presenta como el método obvio para conferir el poder. Pero este consentimiento debe poder renovarse o negarse contando con información sólida y suficiente de los logros obtenidos por el Gobierno y las formas en que lo ha alcanzado, en el contexto que le ha tocado vivir. De ahí la importancia de algunos órganos independientes que controlen la transparencia y la calidad de la información aportada, y otros que evalúen políticas y programas aportando información sólida a la ciudadanía de lo que se está logrando. En este aspecto de la evaluación nuestro país necesita claras mejoras.

Llegados a este punto, creemos que, sin olvidar otras reformas necesarias, es preciso dar un salto adelante y mejorar el sistema de rendición de cuentas vertical mediante un modelo que incentive (incluso obligue) al Gobierno, desde sus más altas instancias, a rendir cuentas de forma sistemática a la ciudadanía sobre el cumplimiento del programa electoral y los compromisos asumidos en el marco de la actividad gubernamental.

Es esencial que este sistema evite tres riesgos esenciales: el primero es que se convierta en un sistema de propaganda oficial, por lo que, para evitarlo, debe ser un sistema que por su rigor y objetividad dé información sin narrativa. El segundo es que pretenda convertirse en un sucedáneo de la evaluación de las políticas o programas gubernamentales. La evaluación exige unos requisitos de rigor científico, temporalidad y participación activa de los afectados que no son asumibles en periodos cortos. El tercero es que se pretenda obviar o sustituir el control parlamentario por este sistema, dejando al Congreso relegado.

Este nuevo modelo de rendición de cuentas, del que por iniciativa del propio presidente Pedro Sánchez ya se ha generado una primera experiencia denominada Cumpliendo y hecha pública en diciembre de 2020, ofrece enormes ventajas para el buen gobierno del país. Para empezar, contribuye a alinear el trabajo de las diferentes organizaciones públicas del Estado con la estrategia del conjunto del Gobierno, comprobando en qué medida contribuyen al cumplimiento del programa y de los objetivos de país asumidos, por ejemplo, en el Plan de Recuperación, Transformación y Resiliencia.

Segundo, exige al Gobierno “dar la cara” y tener que explicar semestralmente a la ciudadanía, a la prensa, al resto de partidos políticos y, por extensión, a las instituciones en las que estos participan, cómo se van cumpliendo los objetivos nacionales y gubernamentales, con datos que son comprobables y que están a disposición de la gente.

Tercero, refuerza la transparencia, aportando información para que la ciudadanía pueda hacerse una idea de si merece confirmar o no a un Gobierno en las próximas elecciones. Finalmente, se puede consolidar como una iniciativa transversal, no partidista, de mejora institucional que sobreviva a cambios de Gobierno y se inserte en un proceso permanente de profundización democrática. En suma, creemos que, con la ayuda de aportes tecnológicos de nueva generación para hacer más visibles, amigables y comprobables los datos, esta rendición de cuentas política y directa puede ser un pilar más en la mejora de nuestra democracia. Para que se consolide, será preciso el esencial aporte de una prensa exigente y constructiva y de una oposición que se implique en el reto de construir una España mejor. Confiemos en ello.

References

Baaijen, Veerle M. & David Galbraith. 2018. Discovery through writing: Relationships with writing processes and text quality. Cognition and Instruction 36(3). 199–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/07370008.2018.1456431.Search in Google Scholar

Bereiter, Carl & Marlene Scardamalia. 1987. The psychology of written composition. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.Search in Google Scholar

Bowker, Lynn & Cheryl McBride. 2017. Précis-writing as a form of speed training for translation students. The Interpreter and Translator Trainer 11(4). 259–279. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750399X.2017.1359758.Search in Google Scholar

Chan, Sathena. 2017. Using keystroke logging to understand writers’ processes on a reading-into-writing test. Language Testing in Asia 7(10). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40468-017-0040-5.Search in Google Scholar

Chau, Tuyen Luan, Mariëlle Leijten, Sarah Bernolet & Lieve Vangehuchten. 2022. Envisioning multilingualism in source-based writing in L1, L2, and L3: The relation between source use and text quality. Frontiers in Psychology 13. 914125. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.914125.Search in Google Scholar

Chodkiewicz, Marta. 2020. Changes in undergraduate students’ conceptual knowledge of translation during the first years of translation/interpreting- and foreign language-related education. Perspectives 29(3). 371–390. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676X.2020.1720257.Search in Google Scholar

Dam-Jensen, Helle & Carmen Heine. 2013. Writing and translation process research: Bridging the gap (Introduction). Journal of Writing Research 5(1). 89–101.10.17239/jowr-2013.05.01.4Search in Google Scholar

Dam-Jensen, Helle, Carmen Heine & Iris Schrijver. 2019. The nature of text production – Similarities and differences between writing and translation. Across Languages and Cultures 20(2). 155–172. https://doi.org/10.1556/084.2019.20.2.1.Search in Google Scholar

Díaz Cintas, Jorge & Aline Remael. 2007. Audiovisual translation: Subtitling. Manchester: St. Jerome.Search in Google Scholar

Dragsted, Barbara & Michael Carl. 2013. Towards a classification of translator profiles based on eye-tracking and keylogging data. Journal of Writing Research 5(1). https://doi.org/10.17239/jowr-2013.05.01.6.Search in Google Scholar

Englund Dimitrova, Birgitta. 2005. Expertise and explicitation in the translation process. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.10.1075/btl.64Search in Google Scholar

Galbraith, David, Sheila Ford, Gillian A. Walker & Jessica Ford. 2005. The contribution of different components of working memory to knowledge transformation during writing. L1-Educational Studies in Language and Literature 15. 113–145. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10674-005-0119-2.Search in Google Scholar

Gebril, Atta & Lia Plakans. 2016. Source-based tasks in academic writing assessment: Lexical diversity, textual borrowing and proficiency. Journal of English for Academic Purposes 24. 78–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2016.10.001.Search in Google Scholar

Hutchins, Edwin. 1999. Cognitive artifacts. In Robert. A. Wilson & Frank C. Keil (eds.), The MIT encyclopedia of the cognitive sciences, 126–128. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.Search in Google Scholar

Immonen, Sini & Jukka Mäkisalo. 2010. Pauses reflecting the processing of syntactic units in monolingual text production and translation. HERMES - Journal of Language and Communication in Business 23(44). 45–61. https://doi.org/10.7146/hjlcb.v23i44.97266.Search in Google Scholar

Jääskeläinen, Riitta. 1999. Tapping the process: An explorative study of the cognitive and affective factors involved in translating. Joensuu: Joensuun Yliopisto.Search in Google Scholar

Jakobsen, Arnt Lykke. 2003. Effects of think aloud on translation speed, revision and segmentation. In Fabio Alves (ed.), Triangulating translation: Perspectives in process oriented research, 69–95. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.10.1075/btl.45.08jakSearch in Google Scholar

Kellogg, Ronald T. 1988. Attentional overload and writing performance: Effects of rough draft and outline strategies. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition 14(2). 355–365. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-7393.14.2.355.Search in Google Scholar

Kellogg, Ronald T. 1994. The psychology of writing. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Leijten, Mariëlle & Luuk Van Waes. 2013. Keystroke logging in writing research: Using Inputlog to analyse and visualize writing processes. Written Communication 30(3). 358–392. https://doi.org/10.1177/074108813491692.Search in Google Scholar

Meyer, Ingrid & Pamela Russell. 1988. The role and nature of specialized writing in a translation-specific writing program. TTR: Traduction, Terminologie, Rédaction 1(2). 114–124. https://doi.org/10.7202/037025ar.Search in Google Scholar

Petrocchi, Valeria. 2020. Précis-writing: A forgotten pedagogic tool in translation training programmes and a highly professional skill in the language-service industry. Poli-Femo (19). https://www.academia.edu/104790266/Précis_writing_A_Forgotten_Pedagogic_Tool_in_Translation_Training_Programmes_and_a_Highly_professional_Skill_in_the_Language_service_Industry.Search in Google Scholar

Puerini, Sara. 2023. Text-production tasks at the keyboard. Linguistic and behavioral contrasts. Translation, Cognition & Behavior 6(1). 29–59. https://doi.org/10.1075/tcb.00075.pue.Search in Google Scholar

Russell, Pamela. 1988. How to write a précis. Ottawa: University of Ottawa.10.1515/9780776608983Search in Google Scholar

Schjoldager, Anne, Kirsten Wølch Rasmussen & Christa Thomsen. 2008. Précis-writing, revision and editing: Piloting the European Master in Translation. Meta 53(4). 798–813. https://doi.org/10.7202/019648ar.Search in Google Scholar

Shreve, Gregory M. 2006. Integration of translation and summarization processes in summary translation. Translation and Interpreting Studies 1(1). 87–109. https://doi.org/10.1075/tis.1.1.06shr.Search in Google Scholar

Spivey, Nancy Nelson. 1997. The constructivist metaphor: Reading, writing and the making of meaning. San Diego: Academic Press.10.2307/358470Search in Google Scholar

Van Doorslaer, Luc. 2010. Journalism and translation studies. In Handbook of translation studies, 180–184. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.10.1075/hts.1.jou1Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Cognitive translation and interpreting studies – an evolving research area and a thriving community of practice

- Research Articles

- Reader differences in navigating English–Chinese sight interpreting/translation

- How does interpreting training affect the executive function of switching? A longitudinal EEG-study of task switching

- Stress and accent in community interpreting

- Many roads lead to Rome: an empirical study of summarizing translation processes

- Dancing with words: the emotional reception of creative audio description in contemporary dance

- Mapping metaphor research in translation and interpreting studies: a bibliometric analysis from 1964 to 2023

- Spotlight on the reader: methodological challenges in combining translation process, product, and translation reception

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Cognitive translation and interpreting studies – an evolving research area and a thriving community of practice

- Research Articles

- Reader differences in navigating English–Chinese sight interpreting/translation

- How does interpreting training affect the executive function of switching? A longitudinal EEG-study of task switching

- Stress and accent in community interpreting

- Many roads lead to Rome: an empirical study of summarizing translation processes

- Dancing with words: the emotional reception of creative audio description in contemporary dance

- Mapping metaphor research in translation and interpreting studies: a bibliometric analysis from 1964 to 2023

- Spotlight on the reader: methodological challenges in combining translation process, product, and translation reception