Abstract

This article presents a bibliometric analysis of metaphor research in Translation and Interpreting Studies (TIS) from 1964 to 2023. An ad-hoc database of 1,023 publications was built based on bibliographic records retrieved from Bibliography of Interpreting and Translation and Translation Studies Bibliography. Descriptive analyses of historical development, cognitive theoretical frameworks adopted, authorship patterns, and publication patterns were conducted to map the general landscape of the field. Furthermore, a four-layer coding frame was applied to conduct fine-grained analyses of empirical studies, classifying them according to their mediation of communication, research orientation, and research method. The results show that the potential overlap between metaphor research and Cognitive Translation and Interpreting Studies (CTIS), a growing sub-field of TIS, is yet to be substantial. Much remains to be done to incorporate metaphor research into CTIS. Following recent theoretical and methodological advancements in Metaphor Studies and CTIS, this article ends with suggestions of how the unfinished cognitive turn of metaphor research in TIS could be brought to completion.

1 Introduction

Metaphor is traditionally considered a practical problem in Translation Studies (Dagut 1976; Newmark 1980; Nida 1964; Snell-Hornby 1988). As a result, the earlier discussions on metaphor translation tend to focus on its rhetorical and linguistic aspects, thereby sanctioning more prescriptive research topics, such as the translatability and translation procedures of metaphor. The game-changing proposal of Conceptual Metaphor Theory (Lakoff and Johnson 1980; hereafter CMT) by Cognitive Linguistics has brought to light the conceptual potential of metaphor, putting a cognitive spin on the linguistic analysis of metaphorical expressions identified in language. This cognitive-linguistic approach has proven to be influential in many fields of study. For example, integrating the new conceptual analysis into more traditional rhetorical analysis has given rise to new approaches to textual analysis, such as cognitive stylistics (Semino and Culpeper 2002) and cognitive poetics (Stockwell 2002). Despite the popularity of CMT, Metaphor Studies as a whole has continued to evolve and go beyond discussions on the conceptual dimension of metaphor as illustrated in Cognitive Linguistics. These new directions include, for example, the discourse nature of metaphor, such as metaphor in specialised discourse (Cameron 2003), the effects of discourse properties on metaphor comprehension (Steen 2004), and the textual patterning of metaphor in discourse (Dorst 2017; Goatly 2011; Semino 2008). More recently, the communicative function of metaphor has also received increasing interest (Gola and Ervas 2016; Musolff et al. 2015; Steen 2008; Thibodeau 2017).

Based on the above sketch, the landscape of Metaphor Studies is vibrant and versatile. However, when it comes to the discussions on metaphor from a translation angle, the impression is that Translation and Interpreting Studies (TIS) lag far behind advancements in Metaphor Studies and still largely focus on cognitive-linguistic approaches that are directly influenced by Conceptual Metaphor Theory (He 2021; Kövecses 2014; Schäffner 2004). The pervasiveness of cognitive-linguistic approaches to metaphor research in TIS becomes particularly glaring when seen from the perspective of Cognitive Translation and Interpreting Studies (Halverson and Muñoz 2021; hereafter CTIS) because studies based on CMT usually bear the label of “cognitive study/approach”, seemingly conjoining with CTIS on the cognitive inquiry of translation and interpreting. Against this backdrop, this bibliometric study sets out to study the intersections of metaphor research and TIS and the extent to which metaphor research in TIS could be said to overlap with CTIS. Moreover, this bibliometric study also arises in part to verify some “folk wisdom” in contemporary literature on metaphor translation: CMT was first introduced to TIS in the 1990s (Schäffner 2017: 249); although probably not the best framework for metaphor research in TIS, it is the most adopted one (Shuttleworth 2014: 59–60); CMT has brought about a cognitive turn of metaphor research in TIS (Hong and Rossi 2021). It is also driven by recent empirical and theoretical advancements in Metaphor Studies, particularly Deliberate Metaphor Theory (Cuccio 2018; de Vries et al. 2018; Reijnierse et al. 2019; Steen 2023; Werkmann Horvat et al. 2023; Wong 2024; hereafter DMT), which prompt us to address them from the perspective of CTIS. Perhaps the time has come to take stock of how far we have come so we can reconceptualise the field.

2 Metaphor research in CTIS and beyond

Before presenting our methodology and the data, we face two difficulties of delimitation: defining metaphor and determining when metaphor research in TIS can be considered to overlap with CTIS. To start with, we take a broad definition of metaphor without restricting it to that of CMT in Cognitive Linguistics: metaphor is “understanding one conceptual domain in terms of another conceptual domain” (Kövecses 2002: 4), i.e., cross-domain mapping. This cognitive-linguistic definition of metaphor is equivalent to conceptual metaphor (see the glossary of metaphor in Kövecses 2002: 251), while metaphors that one can identify in language are treated as metaphorical linguistic expressions of conceptual metaphor. Adopting a broader definition seems more practical because not all publications adopt a CMT understanding of metaphor. We therefore embrace a bottom-up and inductive rather than a top-down and deductive approach to defining metaphor, although the emergence of the category [metaphor], as with other categories in this research, is likely to be dialectical. Essentially, we look at relevant publications in the two databases to see how metaphor is indexed as one of their keywords and how their areas of interest relate to metaphor.

As a result, the not-too-short list of metaphor-related interests we identified in TIS includes but is not limited to metaphor (be it novel, conventional, deliberate, alive, dead, etc.), simile (as directly expressed metaphor), idiom (those that are conventionalised metaphorical expressions), metonymy (as within- instead of cross-domain mapping, if adopting a cognitive-linguistic definition), imagery, neologism (e.g., newly created terms in internet through catachresis), terminology (terminological metaphor in specialised fields), and even normalisation (grammatical metaphor in Systemic Functional Linguistics). The crux is that there is always something figurative involved, whether the figurative meaning is considered in stark contrast to the literal meaning or they are considered on a continuum. Therefore, following the tendency of figurative language research outside of TIS, it seems that metaphor is also considered the umbrella term in TIS for different types of figurative language because metaphor arguably enjoys the most popularity among all kinds of figurative language.

Concerning CTIS, its core is to probe into “the cognitive processes mediating translation, interpreting and any other form of cross-linguistic, cross-cultural, or multilectal mediated communication” (Marín and Halverson 2022: 3). One of the main approaches to examining theoretical constructs such as cognitive load, control, expertise, and emotion is through experimental studies. While it has been suggested that constructs in CITS “are often little more than ill-understood metaphors” (Xiao and Muñoz 2020: 17), metaphor itself, with its relatively strong tangibility in text and speech, does not seem to receive much attention from CTIS researchers (but see Heilmann et al. 2018; Koglin 2015; Zheng and Xiang 2013 for some rare exceptions).

As for the second difficulty, the condition under which metaphor research in TIS could be said to overlap with CTIS may vary significantly depending on how the “cognitive” dimension of metaphor research is understood. On the one hand, much text-based research adopting CMT to study metaphor translation usually bears the label of “cognitive approach/study”. However, the label “cognitive” actually stands for the first element in “cognitive-linguistic” rather than being the base word. In other words, experimental studies are not involved in most cases, and cognitive constructs (e.g., conceptual metaphor) are rarely critically examined. That is, a cognitive-linguistic approach is largely deductive rather than inductive (see also Dąbrowska 2016). On the other hand, it may well be that by “cognitive”, one is indicating more of the empirical, inductive lines of research, which, although not necessarily defining CTIS, do seem to characterise it. In this study, we are leaning towards exploring the conceptualisation reflected by the latter. This is not because the latter is always superior to a cognitive-linguistic approach but because we believe the latter is the crux of developing a more diversified profile of metaphor research in TIS.

3 Methodology

3.1 Data collection and screening

The main objective of this study is to dissect the characteristics of metaphor research in TIS, especially when it overlaps with CTIS, and point out future avenues of this research area. Specifically, we aim to address the following issues:

The evolution of research

Theoretical/conceptual frameworks

Authorship patterns

Publication trends

Characteristics of empirical research

The data in this study was retrieved from two TIS-specific databases – Bibliography of Interpreting and Translation (BITRA; Franco 2001–2024) and Translation Studies Bibliography (TSB; Gambier and van Doorslaer 2024). As of July 2024, BITRA comprises over 94,000 entries and TSB 40,000 entries in total, representing the most holistic TIS bibliographic records and allowing researchers to compile comprehensive literature representing a given area of knowledge. Both databases cover various types of publications – including monographs, book chapters, and journal articles, as well as a broad spectrum of geographical and language origins – such as English, Spanish, French, Italian, Portuguese, and Chinese.

To obtain relevant bibliographic records, we utilised the embedded functions of both databases to perform a keyword search by selecting the term metaphor. As of 18 May 2024, 756 entries from BITRA and 570 from TSB were gathered from 1964 to 2023. The records were then exported and converted into two separate spreadsheet files under the categories of publication year, title, journal, author, and abstract.[1]

Each item in both files was separately screened by the two authors to exclude irrelevant and invalid records based upon the title, the abstract, and, at times, the body of the text. The screening process abides by the following criteria: (1) whether the entry is pertinent to metaphor and translation/interpreting; (2) whether the entry is in the form of a research paper; (3) whether the entry is complete (e.g., some items are indexed with only author information and publication year but without titles); (4) whether there are duplicate items within each database. Considering metaphor is a relatively small research strand in the broader TIS, we decided to take an inclusive approach to data treatment. That is, we kept records devoted to theoretical/conceptual and empirical investigations of metaphor in TIS, as well as comparative studies across cultures and languages. No limits concerning the publication languages were set during the screening process. The authors screened the results separately, and divergences were resolved by meticulously reviewing the documents and discussion before reaching a joint decision. Subsequently, both screened files were combined to remove duplicate records across databases. Eventually, we obtained 1,023 valid records.

3.2 Coding

With the ad-hoc database, we manually coded each valid record – based on the title, abstract, and body of the text – to unveil the characteristics of these publications and address the research issues.[2] A mixture of deductive and inductive coding approaches was adopted (Kuckartz 2014): deductive categories were driven by our research objective and issues and complemented by inductive categories in the course of the coding process. We first determined two main categories: framework (the research or conceptual framework adopted) and research type (whether the research is empirical or not). Sub-categories were enriched and refined based on specific patterns found in the coding process (see Table 1).

General coding frame.

| Main categories | Sub-categories | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Framework | CMT | Conceptual Metaphor Theory |

| DMT | Deliberate Metaphor Theory | |

| CBT | Conceptual Blending Theory | |

| RT | Relevance Theory | |

| SFL | Systemic Functional Linguistics | |

| Others | Other frameworks from Literary Studies, Philosophy, Linguistics, and Translation Studies | |

| Research type | Empirical | Empirical studies focusing on various aspects of metaphor in TIS |

| Others | Theoretical/conceptual accounts; Cross-cultural and cross-linguistic comparative studies;a Metaphor of translation |

-

aThough cross-cultural or cross-linguistic comparison can be seen as a way to study translation and interpreting, we put emphasis on the translational nature of translation and interpreting rather than general comparison.

For a closer look at the topics of empirical metaphor research in TIS, we further developed a coding frame using the same approach. The main categories include mediation of communication, research orientation, and research method, while the sub-categories emerged from the data (see Table 2).

Coding frame for empirical studies.

| Main categories | Sub-categories | Description | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mediation of communication | Translation | Written | Translation mediated by written elements (e.g., novels, news) |

| Multimodal | Translation mediated by verbal and non-verbal elements (e.g., theatre translation, subtitling, audio description, etc.) | ||

| Machine | Translation involving the use of machine (e.g., machine translation and post-editing) | ||

| Interpreting | Oral | Interpreting mediated by spoken language | |

| Sign | Interpreting mediated by sign language | ||

| Research orientation | Product | Focusing on the translation/interpreting final outputs | |

| Process | Focusing on the translation/interpreting process | ||

| Participant | Focusing on the translator/interpreter or recipient of the translation/interpreting product | ||

| Research method | Text measures | Analysis based on the source and translated texts (e.g., qualitative close reading) | |

| Corpus measures | Analysis based on/assisted by/driven by corpus (e.g., quantitative analysis of a large collection of digitalised texts) | ||

| Behavioural measures | Analysis tracking the participants’ behaviours (e.g., eye-tracking, keylogging, think-aloud protocol, screen recording, reaction time analysis) | ||

| Introspective measures | Analysis soliciting responses from the participants’ self-reports (e.g., retrospection, survey, questionnaire, interview) | ||

| Psycho-physiological measures | Analysis measuring the participants’ psycho-physiological responses (e.g., heart rate) | ||

The coding process was conducted on the combined spreadsheet. Each author performed the first coding attempt with nonidentical categories in the coding frame. Ambiguous entries and questionable categorisations were highlighted during the individual coding process, followed by a joint discussion for further confirmation. When the first attempt was completed, both authors cross-checked all codes before finalisation. We eventually imported the completed spreadsheet into the visualisation software Tableau for data presentation.

4 Results

4.1 Historical development

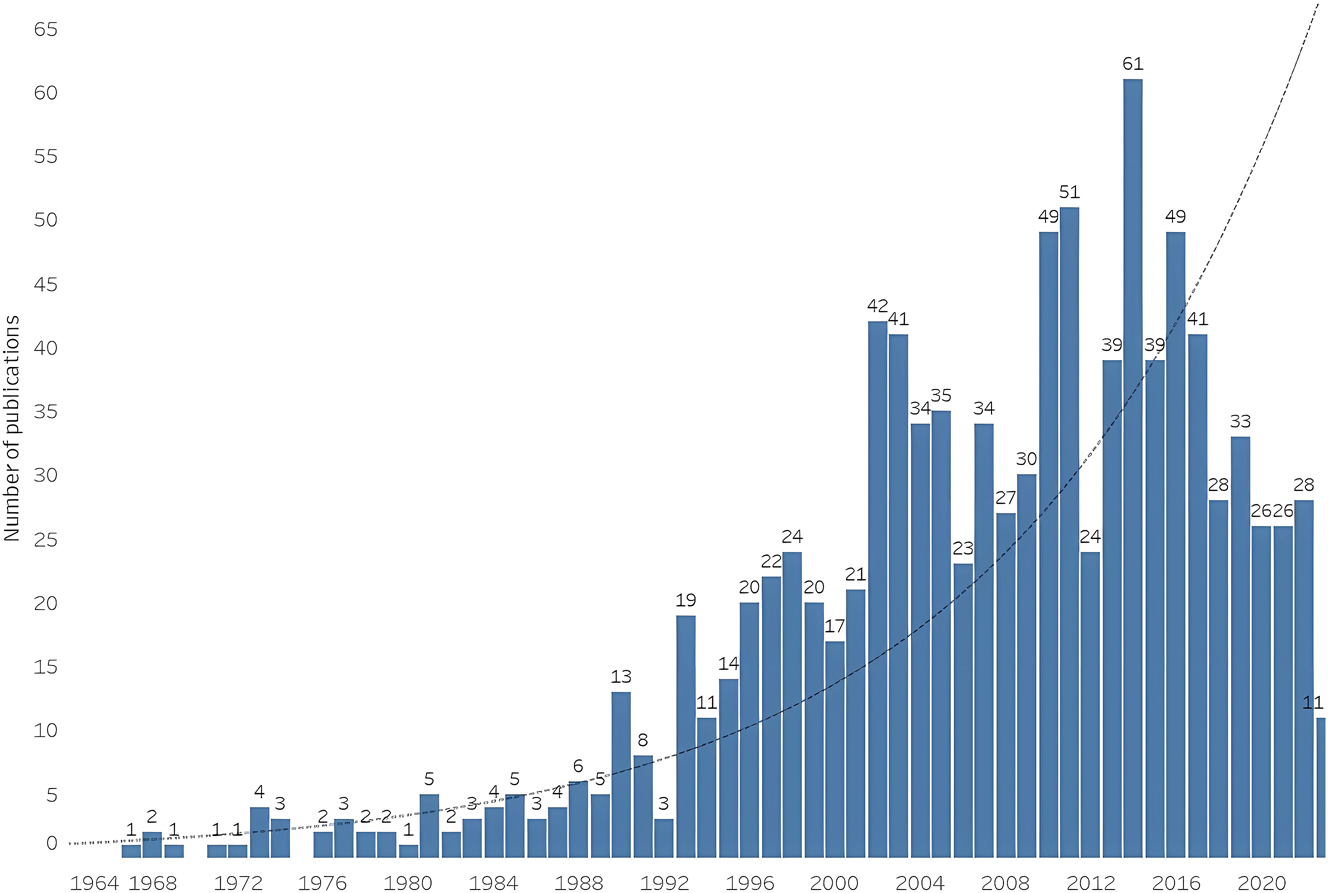

Although we are aware that one of the earliest (though minimal) discussions on metaphor translation in the modern era scholarship can be found in Nida’s seminal work on translation (1964: 219–221), the above bibliometric analysis shows that the first metaphor research in TIS did not appear until 1967 (Beekman 1967), judging by records indexed in the two databases under analysis (see Figure 1). In fact, no publications earlier than 1967 were found in the two databases. The nearly sixty years of development captured by the databases, which have seen steady growth over the years, can be roughly and conveniently divided into two stages: the initial stage (from 1964 to 1993) and the rising stage (from 1994 to 2023). During the initial stage, metaphor research in TIS was relatively scarce, mostly registering fewer than ten publications per year, except in 1990 (13 records) and 1993 (19 records). As for the rising stage, the number of publications per year mostly reaches above 20, and almost half of the years even go above 30. The exponential trendline created by Tableau’s built-in function (log-transformed data fitting in a linear regression model; R 2 = 0.80, p < 0.001) further suggests that the publication number per year has risen at increasing rates over the years. In other words, the growth is exponential rather than linear or logarithmic. Although the number seems to have peaked in 2014 (61 records) and dropped gradually, this does not suggest that researchers are moving out of the field after 2014. Firstly, databases’ collection of bibliographical data through online mining generally experiences certain degrees of delay, an effect reflected in a slight drop common to much bibliometric research when approaching the present period. Secondly, the relatively high volume of publications in 2014 was mainly due to the publication of an edited volume on translating figurative language (Miller and Monti 2014), which single-handedly contributed 24 records for that year to our dataset. This is to say, whether metaphor research in TIS will reach new heights depends on, for example, whether there will be more concentrated efforts or new theoretical advancements that lead to surging interests in the field.

Number of metaphor research outputs in TIS by year (with a dotted trendline).

On the other hand, a closer look at how publication year intersects with the theoretical framework confirms that Schäffner may be correct in saying that CMT “entered Translation Studies only in the 1990s” (2017: 249) because the earliest research adopting the CMT framework was only found as late as 1990 (Königs 1990). However, CMT does not seem to be the major reason for the exponential growth of metaphor research in TIS around the turn of the millennium. Convenience sampling from several intermediate peaks before 2000, namely 1990, 1993, and 1998, reveals that the share portion of CMT in the frameworks adopted was not particularly significant: only 15.38 % (2 out of 13 records), 15.79 % (3 out of 19 records), and 29.17 % (7 out of 24 records) of publications adopted the CMT framework in 1990, 1993, and 1998, respectively. The proliferation of metaphor research in TIS starting from the 1990s possibly has more to do with the increasing establishment of TIS as an independent discipline and the overall expansion of higher education in different disciplines. As a result, there was simply more research produced in any field overall, including research on translating figurative language.

4.2 Theoretical frameworks

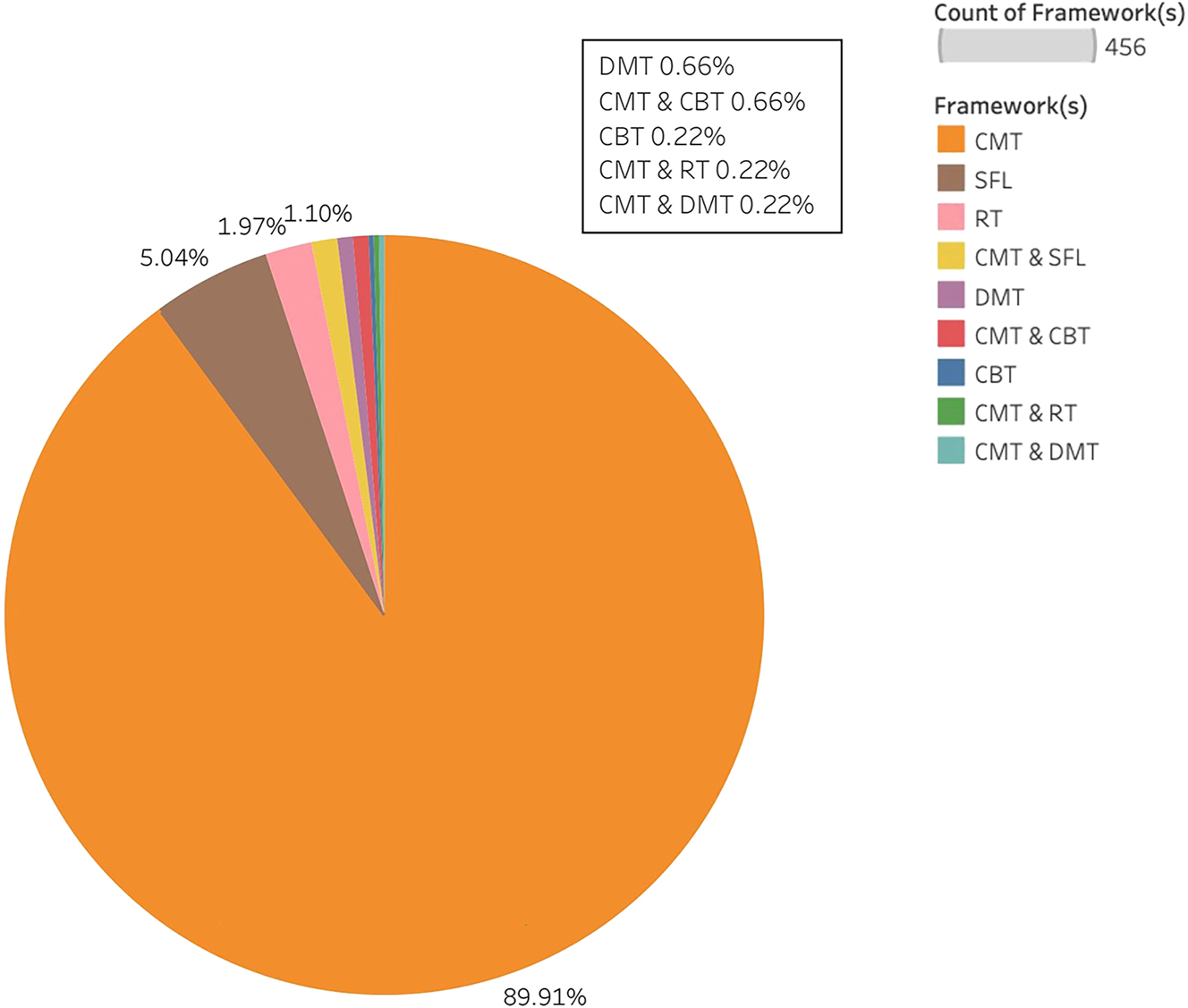

Only 44.57 % of publications (456 out of 1,023 records) adopt cognitively informed (metaphor) theories as their framework(s) of metaphor research in TIS. These theories are defined and coded here in a limited fashion as CMT (Conceptual Metaphor Theory), DMT (Deliberate Metaphor Theory), CBT (Conceptual Blending Theory), RT (Relevance Theory), and SFL (Systemic Functional Linguistics). On the other hand, 55.43 % of publications (567 out of 1,023 records) adopt miscellaneous frameworks from Literary Studies, Philosophy (e.g., Benjamin, Derrida), and various branches of Linguistics (e.g., lexicography, phraseology, terminology, contrastive linguistics), to name a few; a considerable number of publications also draw on frameworks within Translation Studies (e.g., those by Newmark and Snell-Hornby) without invoking any metaphor-related theories. These latter groups of frameworks coded as Others are excluded from the analysis of theoretical frameworks in this study not because of their demerits but because of our focus on modern-day theories with a cognitive edge.

Prior to analysis, we need to clarify how these theories could be said to be “cognitive”. CMT defines the cognitive label for (conceptual) metaphor. CMT claims that understanding metaphor always involves understanding one conceptual domain in terms of another (Kövecses 2017: 13). However, defining metaphor as cross-domain mapping does not mean that, in reality, processing metaphor always involves a specific cognitive process. Bringing in psycholinguistics’ perspectives of metaphor processing (e.g., Bowdle and Gentner 2005) to the development of a new metaphor theory, DMT restricts CMT’s claim on cross-domain mapping to a particular class of metaphor (i.e., deliberate metaphor) and can “be interpreted as an extension of CMT” (Steen 2015: 71). On the other hand, although not developed as a metaphor theory, CBT is also cognitively relevant to the study of metaphor. CBT proposes conceptual blending as a general cognitive operation underlying human cognition. The mechanism of conceptual blending involves the projection of two mental spaces onto a third space called generic space and the subsequent emergence of a fourth space called blended space (Fauconnier and Turner 2002: 39–50). Mental spaces in CBT are understood as “small conceptual packets constructed as we think and talk, for purposes of local understanding and action” (Fauconnier and Turner 2002: 40). Suffice it to say, CMT’s notion of conceptual metaphor, if contextualised in CBT’s understanding of the blending operation of human cognition, can be understood as involving a single-scope blend (Dancygier 2017: 32).

Furthermore, RT is also not a metaphor theory but can be cognitively relevant to metaphor research in TIS. As a theoretical approach to understanding human communication and cognition, RT proposes the cognitive principle that “[h]uman cognition tends to be geared to the maximisation of relevance” (Sperber and Wilson 1995: 260) and the communicative principle that “[e]very act of ostensive communication communicates a presumption of its own optimal relevance” (Sperber and Wilson 1995: 260). Within this relevance-theoretic approach, metaphor is but one kind of loose use in communication that can achieve optimal relevance in some situations but that requires “no mechanisms or processes specific to the recognition and comprehension” (Carston 2017: 43).

Lastly, being the odd one out, SFL is a general approach to Linguistics rather than an independent theory. However, it is included in this list because publications in our dataset have exclusively used it to study the grammatical metaphor in translation and interpreting (nominalisation and denominalisation).

Figure 2 shows the distribution of cognitively informed theories adopted by metaphor research in TIS. Noticeably, CMT alone contributed to almost 90 % of the publications, even if discounting the 2.19 % of publications that combine CMT and other theories as their frameworks. This confirms the claim that CMT is “the most frequently adopted theoretical framework for research into metaphor in translation” (Shuttleworth 2014: 60). One of the reasons for this is that, proposed in 1980, CMT has had a long history of more than four decades of theoretical development, attaining high levels of maturity and divisionalisation. As a result, CMT is relatively easy to apply when conducting case studies in TIS. Besides, it is possibly the only cognitive metaphor theory that comes to mind for most people and has been the go-to theory for a cognitive approach.

Percentage of cognitively informed theories adopted by metaphor research in TIS.

On the other hand, DMT, with less than 1 % of the total share, has yet to receive much exploration from TIS scholars. This is partly because, despite early theoretical proposals in the 2000s (Steen 2008), DMT only gradually established itself as a metaphor theory over the years, as late as the label was coined in 2015 (Steen 2015). As a rule of thumb, the introduction of a theory to TIS can take as long as ten years, as in the case of CMT. Besides, CBT and RT, as theories of cognition and pragmatics (respectively), have only occasionally drawn the attention of TIS scholars, even when their histories can be traced to the late 20th century. This is probably because their theorisation did not focus exclusively on metaphor.

4.3 Authorship and top productive authors

Our bibliometric analysis of publication authorship reveals that the majority of publications are single-authored (80.84 %). In contrast, publications with two, three, and four authors only amount to 15.54 %, 3.13 %, and 0.49 %, respectively. No publications have more than four authors. Contrary to our initial anticipation, the relatively low level of collaboration between scholars does not seem to sanction a network analysis. Besides, if the maturity of a field is partly determined by the degree of collaboration between scholars, it is not unfair to say that metaphor translation as a field (19.16 % co-authorship as of 2023) lags slightly behind CTIS as a whole (24.6 % co-authorship in CTIS as of 2015, according to Olalla-Soler et al. 2020).

Furthermore, Table 3 presents a count of the top 11 productive authors of metaphor research in TIS, ranked according to the number of publications in which they are the first author (also mostly the sole author). Their total number of single-authored and co-authored works is also included in the table but is for reference only. This ranking of publication volume should not be directly taken as their relative impact and influence on the field because metrics such as their total citation were not taken into account given the incompleteness of citation metrics in BITRA and their unavailability in TSB. Still, several interesting patterns could be identified. Firstly, scholars usually either work on the translation of metaphor (e.g., Popescu, Samaniego, Schäffner, Shuttleworth) or on metaphor of translation (Guldin, St. André). Secondly, except for a few who primarily work on theoretical and conceptual issues, scholars usually specialise in metaphor translation in one particular type of discourse and work almost exclusively on that: for example, political discourse (Schäffner), popular science (Shuttleworth), and business and economic discourse (Dobrota, Fernández, Popescu, Silaški). No scholars have been found to specialise in literary discourse. Thirdly, there are yet to be scholars working on metaphor and interpreting who make it onto the list. Last but not least, no scholars, if judging by the research orientation of their publications indexed in the dataset, are primarily associated with CTIS (except perhaps Martín, who is now much engaged with CTIS, but her earlier publications on metaphor in the 2000s are mainly theoretical ones).

Top 11 productive authors of metaphor research in TIS.

| Ranking | Author | No. of first-author publications (if including co-author ones) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Eva Samaniego Fernández | 14 (15) |

| 2 | Christina Schäffner | 11 (11) |

| 3 | Teodora Popescu | 9 (10) |

| Peter Newmark | 9 (9) | |

| James St. André | 9 (9) | |

| 4 | Mark Shuttleworth | 8 (10) |

| 5 | Aurea Fernández Rodríguez | 7 (8) |

| Nadežda Silaški | 7 (8) | |

| Corina Dobrota | 7 (7) | |

| Rainer Guldin | 7 (7) | |

| Celia Martín de León | 7 (7) |

4.4 Journals that publish the most metaphor research

Metaphor studies are usually published in journals such as Cognitive Linguistics, Journal of Pragmatics, Metaphor and Symbol, and, since the last decade, Metaphor and the Social World. As for metaphor research in TIS, its publication patterns will probably be less straightforward. We have identified 239 journals from our database that have published metaphor research, accumulating 555 journal articles. To determine the journals that publish the most metaphor research, we counted the number of articles published in each journal and their proportions. Table 4 presents the results with some basic statistics.

11 journals that publish the most metaphor research in TIS.

| Ranking | Journal (since) | Articles | Proportion |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Babel (1955–) | 36 | 6.49 % |

| 2 | Meta (1956–) | 31 | 5.59 % |

| 3 | Perspectives (1993–) | 14 | 2.52 % |

| Target (1989–) | 14 | 2.52 % | |

| 4 | Notes on Translation (1962–2001)a | 11 | 1.98 % |

| 5 | The Journal of Specialised Translation (JoSTrans) (2004–) | 10 | 1.80 % |

| 6 | The Bible Translator (1950–) | 9 | 1.62 % |

| 7 | Translation and Interpreting Studies (2006–) | 8 | 1.44 % |

| 8 | Terminology (1994–) | 7 | 1.26 % |

| Translation Journal (1997–2019) | 7 | 1.26 % | |

| Traduction Terminologie Rédaction (TTR) (1988–) | 7 | 1.26 % | |

| The Translator (1995–) | 7 | 1.26 % |

-

aThis journal is no longer active. As we cannot find other sources specifying this journal’s exact active period, this time range is based on the earliest and latest records found in BITRA.

Babel (36; 6.49 %) and Meta (31; 5.59 %) take the lead, contributing more than 30 articles throughout the investigated timespan. This looks reasonable, as both journals dedicate many, if not all, of their publications to literary translation, which was a central focus in the early stages of TIS. This may also explain why time-honoured journals, including Notes on Translation (11; 1.98 %; though no longer active) and The Bible Translator (9; 1.62 %) – both focusing on Bible translation – are also included in this list, contributing a combined total of 20 articles. As Translation Studies started off by looking into translating literary and religious texts, the importance or difficulty of translating metaphorical expressions within such genres may have attracted much scholarly attention at the initial stage.

Next come the leading TIS journals Perspectives (14; 2.52 %) and Target (14; 2.52 %), contributing around 30 articles combined. These two journals are well-established in publishing both theoretical and empirical research in different kinds of linguistic and cultural mediation. Our database also shows a variety of metaphor-related topics in the two journals, ranging from theoretical modelling of metaphor translation (e.g., Dickins 2005), the metaphorical conceptualisation of translation (e.g., Cheung 2005), to practical techniques for undertaking metaphor translation (e.g., Al-Zoubi 2009), and empirical investigations in specific texts, genres, and contexts (e.g., Grave 2016).

In addition, journals commenced after the millennium, such as JoSTrans (10; 1.80 %) and Translation and Interpreting Studies (8; 1.44 %), also published quite a few articles on metaphor research. While Translation and Interpreting Studies embraces all areas of language mediation like the journals mentioned above, JoSTrans emphasises non-literary translation and interpreting in subject-specific fields. Most of the publications in these two journals appear after the 2010s, which seems to coincide with the then-changing landscape of TIS driven by “the emergence and proliferation of multimodal texts and digital technology” (Munday et al. 2022: 232). For example, we can find innovative endeavours to explore metaphors in legal translation using large corpora (Božović 2022), audiovisual translation (Pedersen 2015), and machine translation and post-editing (Koglin and Cunha 2019).

4.5 Mediation of communication

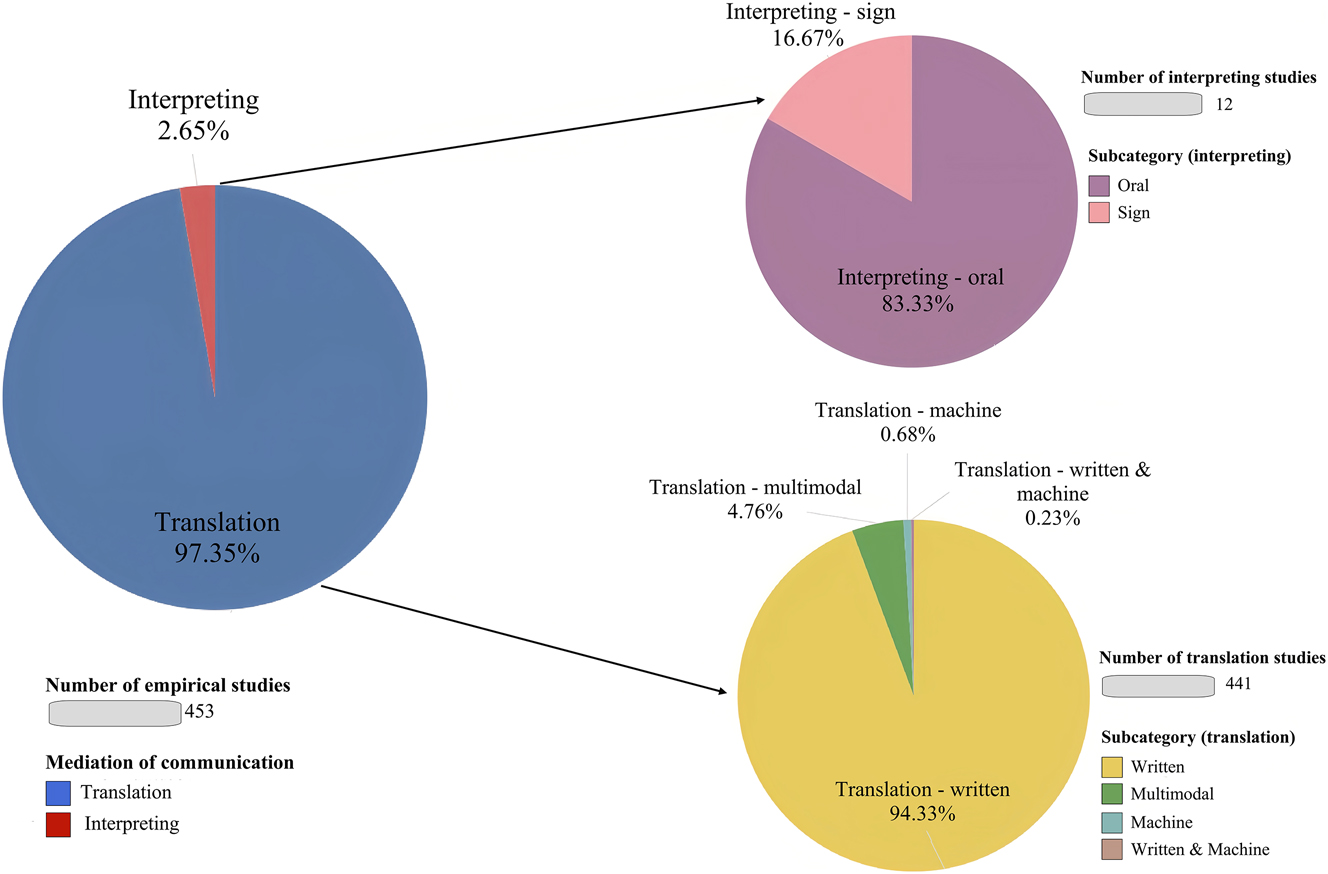

Zooming in on empirical studies, we have identified 453 valid records from our database. In the following, we will explore how metaphor research unfolds in the contexts of various types of mediated communication.

Mediated communication takes various forms, especially for those involving multiple languages (or “multilectal mediated communication”; see Halverson and Muñoz 2021). For this study, we streamlined the classification of mediation and grouped the research into two main categories based on their research subjects: translation and interpreting. Translation and interpreting here are operationalised as a translational activity that involves cross-linguistic and non-linguistic transfer; the difference is that interpreting deals with a “one-time presentation” (Pöchhacker 2022: 11) of the (non-)linguistic elements while translation does not.

To gain a deeper understanding, we further sub-categorised the two main categories by assigning codes to crystallise the mediation. Translation research papers involving only written texts were coded as written; when they additionally involved non-verbal elements, the code was multimodal; when they addressed machine translation, they were labelled machine. For interpreting research, oral and sign were distinguished. The distributions of translation- and interpreting-dedicated research and their sub-categories are visualised in Figure 3.

Distribution of empirical metaphor translation and interpreting research.

Several prominent trends are depicted in Figure 3. From a bird’s eye view, metaphor is investigated more dominantly in translation research than in interpreting research, with the former accounting for more than 97 % of the total empirical studies. Within translation research, written translation occupies the lion’s share (94.33 %), followed by multimodal translation (4.76 %); only a few studies look at metaphor in the context of machine translation. As for interpreting research, spoken language interpreting (83.33 %) is the main area where metaphor is probed, though sign language interpreting also captures some attention.

The small proportion of metaphor interpreting research could be accounted for from several aspects. Firstly, the community of researchers investigating metaphors in interpreting is arguably smaller than that engaged in translation research, leading to a comparatively small number of publications. Secondly, interpreting studies is often plagued by methodological constraints: an intricate challenge for interpreting scholars is to obtain (transcribed) in-the-field texts, and there are only a few options of publicly available recordings (Pöchhacker 2022: 225). Since metaphor is primarily text- or discourse-embedded, interpreting scholars, without acquiring such textual data, may have fewer choices but to rely on simulated texts in a somewhat restricted fashion.

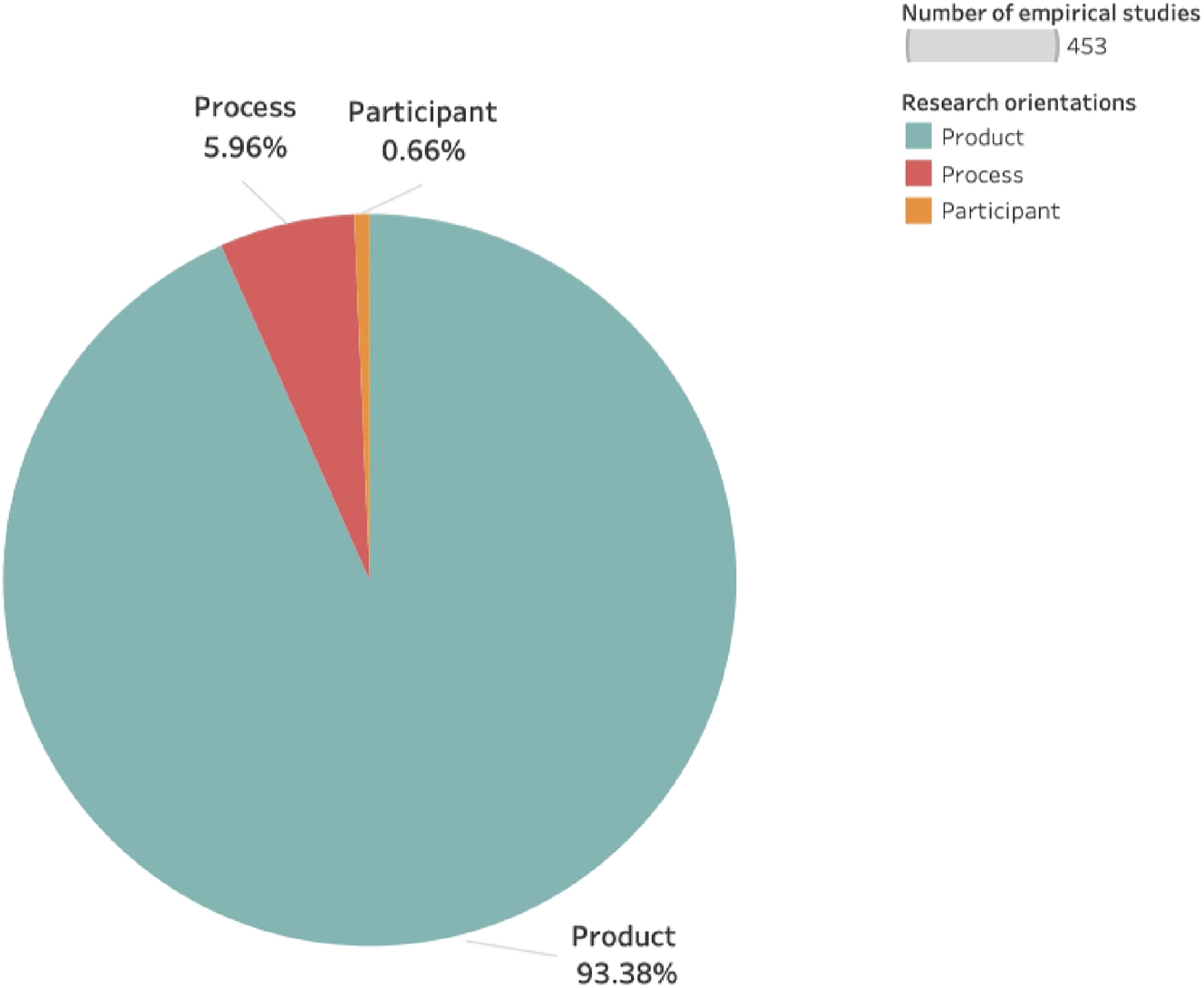

4.6 Research orientation and method

The categorisation of research orientation is based on how the empirical data is acquired and analysed. We have identified three orientations from the 453 empirical studies: product-oriented, process-oriented, and participant-oriented research. Product-oriented research focuses on translation and interpreting final outputs; process-oriented research highlights the translators’ or interpreters’ online processing when the task is performed in situ; participant-oriented research emphasises the translators’ and interpreters’ own general feelings of the process and the reception of translation and interpreting products.[3]

Figure 4 encapsulates the distribution of the three research orientations in empirical studies. Noticeably, product-oriented research takes up the most significant proportion (93.38 %) of all empirical studies, overshadowing process-oriented research (5.96 %) and participant-oriented research (0.66 %). The dominance of product-oriented research may be explained by the deductive tradition of the cognitive-linguistic approach to metaphor (our database shows that 46.68 % of product-oriented studies adopt the CMT framework).

Distribution of research orientations in empirical studies.

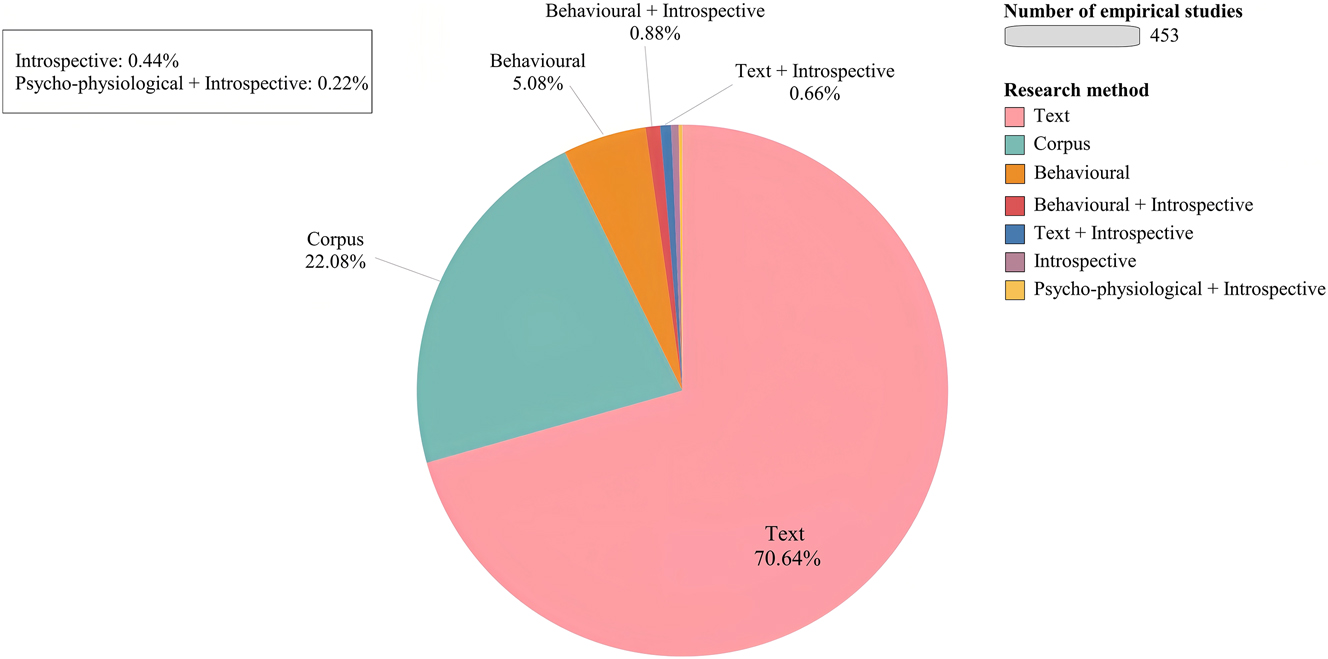

Departing from the research orientations mentioned above, we further examined the research methods used in these empirical studies. Figure 5 depicts the methodological landscape of all empirical studies.

Distribution of specific research methods used in empirical studies.

As shown in Figure 5, text-based research constitutes the majority of all empirical studies, accounting for around 71 %. This prevalence likely reflects the long-standing tradition of metaphor research using textual data. Research that leverages corpora, comprising approximately 22 %, ranks second. This seems to suggest a growing interest in utilising a large amount of (digital) textual data in complementary to the traditional textual analysis approach.

Research that adopts behavioural measures comes third, representing 5.08 % of the total. Research using only introspective measures (0.44 %) is noticeably scarce. The small proportions hint that these two measures are less frequently used in metaphor research in TIS.

Furthermore, a few studies integrate behavioural, text-based, and psycho-physiological measures with introspective measures. Though they hold a minimal share (1.76 %), their use of combined measures in metaphor research in TIS suggests an emerging trend toward methodological triangulation.

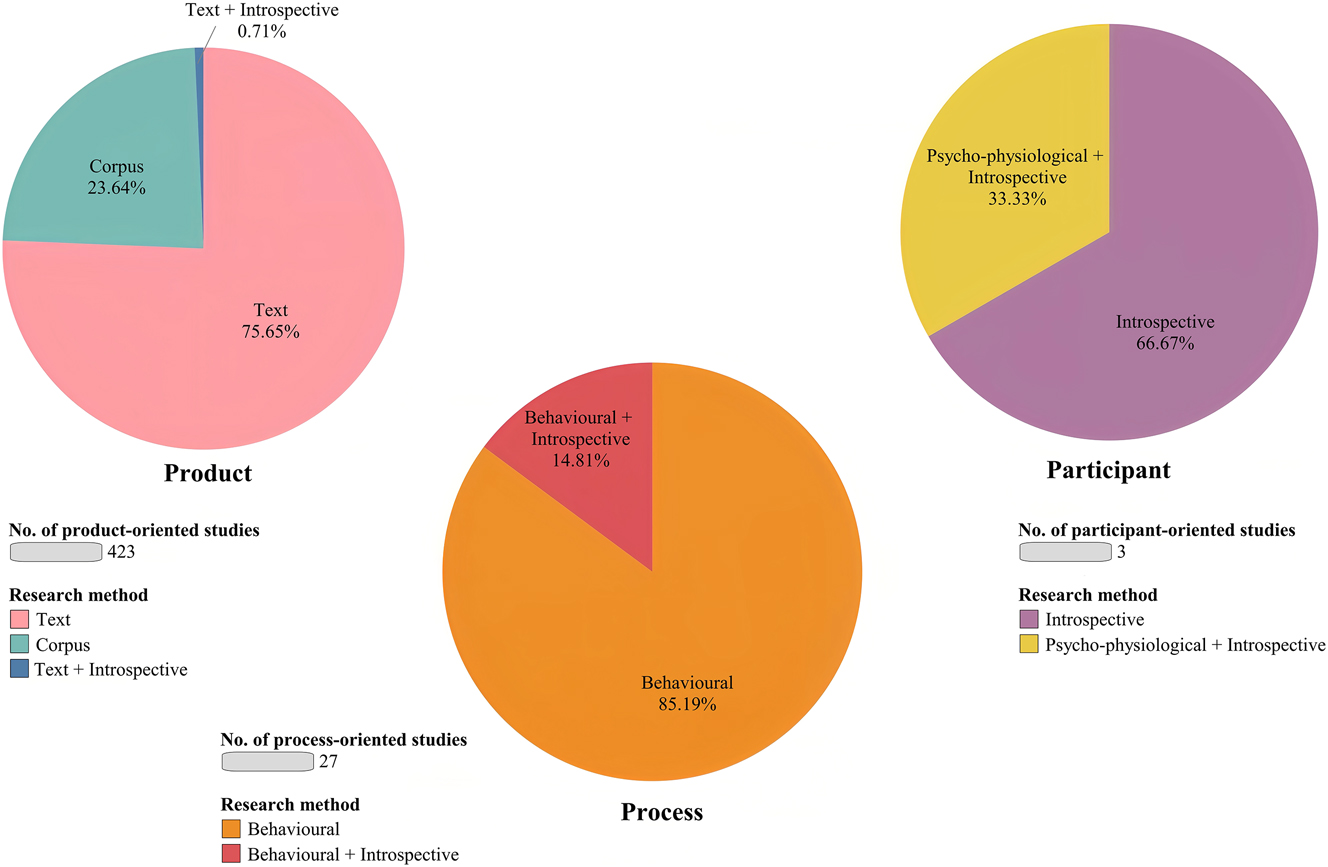

To better understand how different methods are applied and distributed, we aligned them with the three research orientations. Figure 6 shows the methodological landscape across three research orientations.

Distribution of methods used in the three research orientations.

Among the 423 product-oriented studies, text-based analysis (75.65 %) is the dominant method, followed by corpus analysis (23.64 %). Even though product-oriented research enjoys the largest number of studies, the exploration of metaphor still focuses on linguistic features, whether the analysis is based on a single source or a large amount of textual data. There is also a tiny proportion of studies combining text and introspective measures (0.71 %). One example is exploring translation trainees’ strategies for translating linguistic metaphors with/without the existence of comparable conceptual metaphors through mixed methods, i.e., quantitative output rating and qualitative interview (Chen 2017).

Within a small pool of 27 studies, it is evident that process-oriented research is dominated by behavioural measures, including eye-tracking, keylogging, think-aloud protocol, screen recording, and reaction time analysis, to link the translator’s behavioural patterns with underlying cognitive processing. While behavioural measures are mainly employed without incorporating other measure types (85.19 %), this does not indicate that process-oriented research always uses one method at a time. There are plenty of studies adopting a combination of behavioural measures. A typical example would be an integration of eye-tracking and keylogging to investigate translators’ cognitive effort in translating metaphors (e.g., Koglin 2015; Sjørup 2013). Moreover, behavioural measures are sometimes used in conjunction with introspective measures (14.81 %). For example, a common choice of methods would be to combine eye-tracking, keylogging, and retrospective interviews (e.g., Schmaltz 2018; Wang 2021). These endeavours can be considered attempts to enhance methodological rigour through multi or mixed methods research.

When it comes to participant-oriented research, only three studies have been identified. These studies utilised introspective measures, such as questionnaires and interviews, to understand the participants’ subjective feelings towards metaphor while translating, interpreting, and consuming the translated/interpreted product. Additionally, psycho-physiological measures, exemplified by heart rate and facial expression variation, may provide a more objective angle for this purpose (see Ramos Caro 2016).

In summary, metaphor has been examined in various stages of translation and interpreting. However, while product-oriented research still takes the lead in the quantity of research output, process-oriented and participant-oriented research is catching up with methodological rigour, adding a more cognitive profile to metaphor research in TIS.

5 Discussion

Our study finds that metaphor research in TIS demonstrates the prevalence of text measures in the dominant number of product-oriented studies. While process-oriented (and, though scarce, participant-oriented) research exhibits a tendency towards methodological rigour in exploring translators’ and interpreters’ cognitive processing, it is still too early to say that metaphor research has developed a diversified profile in TIS. Moreover, it seems that the existing product-oriented and process-oriented metaphor research in TIS are two separate worlds: one centres around properties of (authentic) texts to make inferences about the translator’s and interpreter’s behaviours; the other taps into cognitive processes by observing behaviours through laboratory manipulation. Internal dialogue between product-oriented and process-oriented research, namely cross-referencing each other’s findings, is lacking.

In recent epistemological reflections on CTIS, discontent was voiced that although CTIS research on empirical problems has grown increasingly sophisticated, scholars often “did not take the opportunity to revisit the constructs they tested” (Marín and Halverson 2022: 3). Correspondingly, our bibliometric analysis of metaphor research in TIS suggests to us that effort to put metaphor-related constructs (e.g., conceptual metaphor) to theoretical testing has so far been very moderate in number. Most of the time, these constructs are taken for granted as theoretical grounds for conducting product-oriented research. This may be because metaphor theories (e.g., CMT) have traditionally been accepted without question and are predominantly applied in text-based analyses. As a result, there has been a notable lack of critical reflections on their theoretical claims, and empirical-experimental studies aimed at (in)validating them remain conspicuously absent. It is, therefore, not unfair to say that metaphor research in TIS lags behind CTIS in terms of theoretical and methodological scepticism. Without a proportionate amount of this, metaphor research in TIS may remain an applied branch of other disciplines (e.g., Cognitive Linguistics) from which they unidirectionally inherit the theoretical framework.

On the other hand, recent theoretical reflections in Metaphor Studies may open up new possibilities for CTIS researchers to engage with cognitive aspects of metaphor in translation and interpreting. These new possibilities powered by DMT arise from recognising the paradox that not all metaphors studied in a cognitive-linguistic framework are processed by cross-domain mapping according to psycholinguistic findings (Steen 2008). Moreover, the cognitive-linguistic account of metaphor may demonstrate a structure-process fallacy that mistakes conceptual structures (i.e., conceptual metaphor) abstracted from linguistic data by researchers for the online cross-domain processing that can be observed in language use (Steen 2017: 5). Decoupling conceptual structures of metaphor from the actual processing of metaphor by language users, DMT holds promise for making a cognitive turn of metaphor research in TIS that is more thorough than simply adopting a cognitive-linguistic framework for comparative analysis of translation and interpreting data. This is because, drawing from the career of metaphor hypothesis (Bowdle and Gentner 2005), online metaphor processing is embedded in DMT’s conceptualisation of when a metaphor could be said to be metaphorical. Only when a metaphor requires the slower processing mechanism of cross-domain mapping in comprehension could it be said to be metaphorical. DMT predicts this to be an effect of deliberate metaphor, “the intentional use of a metaphor as a metaphor” (Steen 2015: 67).

According to Bolognesi, this new variable of metaphor deliberateness (deliberate vs. non-deliberate) “offers a wide range of open empirical questions that can be addressed from a theoretical perspective as well as from an experimental perspective” (2022: 237). Recent experimental works in Metaphor Studies have started to pick up this line of thought and provide supporting evidence for the psychological reality of deliberate versus non-deliberate metaphor in utterance comprehension (de Vries et al. 2018; Werkmann Horvat et al. 2023). Furthermore, it has been suggested that this psychological reality may also hold for translators’ and interpreters’ comprehension of metaphor in the source language and requires further experimental testing in different scenarios of translation and interpreting (Wong 2024). It would be interesting to test, for example, whether translating deliberate metaphor is indeed more cognitively taxing than translating non-deliberate metaphor; if yes, which stage of translation and interpreting (comprehension, production, or both) imposes higher cognitive load on translators and interpreters; and how translation directions (L1-L2, L2-L1) and language combinations interact with the corresponding cognitive load.

Moving on to methodology, we have not identified a single study from our database that adopts both product-oriented and process-oriented approaches to investigate the cognitive aspects of metaphor in TIS. This situation speaks to the recent call for multimethod approaches to (re)visit cognitive constructs in CTIS in an epistemically plural way (Serbina and Neumann 2022). A systematic product-process integration can elucidate and contrast the representation of a construct in authentic and experimental conditions. Combining product-oriented and process-oriented data in a single research design may open avenues for a more comprehensive understanding of how “cognitive” metaphor can be. Following the previous connection between deliberate metaphor and cognitive load, it would be intriguing to first construe patterns of translated deliberate metaphor as cognitive load indicators with the help of corpora and then conduct post-hoc analysis to (in)validate those patterns in simulated translation and interpreting tasks by aligning behavioural data (e.g., eye-tracking, keylogging). Another insightful approach would be to gather a large amount of behavioural and textual data in translating and interpreting deliberate metaphors for corpus annotation and statistical modelling. This may help reveal cognitive load from both behavioural-psychological and textual-linguistic perspectives within a single dataset. Such product-process collaboration may not only bolster methodological robustness but also tap into the interdisciplinary potential of metaphor research in (C)TIS.

Nevertheless, this study is limited in several aspects. Firstly, both BITRA and TSB databases periodically update their bibliographic records through online mining. As a result, some entries added after our data collection period might not have been retrieved, potentially leading to gaps in coverage. Consequently, this study may not be able to cover all metaphor research in TIS within the investigated period, and the generalisation of the findings should be taken with caution. Future research can set a five-year interval to obtain and analyse bibliometric data to mitigate the mining effect of the databases. Moreover, more bibliographic data could be retrieved to enhance the comprehensiveness of an ad-hoc database if future endeavours incorporate more databases such as the Social Science Citation Index and the broader Web of Science. Secondly, despite the indiscriminate approach to data screening, an overwhelming number of publications in western languages are documented in our database, leaving those in eastern languages less well represented. This seems to be an entrenched weakness in using western-based international databases for bibliographic study (see also Olalla-Soler et al. 2020). More concerted efforts can be made to align eastern-based databases with western-based ones to produce a more comprehensive picture. Thirdly, given the existing anecdotal records of metaphor research within CTIS, it would be difficult to reveal any meaningful evolution within the investigated timespan. Future bibliometric studies could benefit from conducting time series analyses to track the growth of metaphor research within CTIS. Lastly, we note that by taking the percentage of process-oriented and participant-oriented research as an (indirect) indicator of the potential overlap between metaphor research and CTIS, we risk not having completely reflected the nuances of CTIS, which has gone beyond the translation process and included different aspects of communication. Future research could overcome this limitation by developing more sophisticated ways of operationalisation that allow for a case-by-case approach to examining bibliographical data.

6 Conclusions

Contrary to the received opinion, our bibliometric analysis has suggested that the so-called cognitive turn that CMT is said to have brought about in TIS may have been overstated. It is not denied here that CMT pioneered drawing the connection between metaphor and cognition. However, CMT is not the only theory attempting this. On the other hand, our bibliometric research has shown that, above all, only 6.62 % of the empirical studies are process-oriented and participant-oriented. Therefore, metaphor research not overlapping with CTIS does seem to be the rule rather than the exception. Such a situation is interesting yet alarming enough to make sense of. If we consider metaphor a cognitive phenomenon rather than a rhetorical device, why is most empirical research still text-based and rarely experimental? We are faced with a crack between reality and our beliefs. It is hoped that this bibliometric study and our theoretical and methodological suggestions may serve as a starting point for bridging that gap. To conclude, metaphor research in TIS can indeed be “cognitive” and potentially become a core part of CTIS, but we have to be epistemologically careful about what we mean by that.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Ricardo Muñoz Martín and the two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments. Our thanks are also due to Mark Shuttleworth for commenting on an earlier draft. Any remaining errors are ours.

-

Funding information: This work was supported by a University Grant (UG) Studentship awarded to the first author for his PhD study at Hong Kong Baptist University.

References

Al-Zoubi, Mohammad. 2009. The validity of componential analysis in translating metaphor. Perspectives 17(3). 151–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/09076760902957181.Search in Google Scholar

Beekman, John. 1967. Metonymy and synecdoche. Notes on Translation 23. 12–25.Search in Google Scholar

Bolognesi, Marianna. 2022. Metaphors in intercultural communication. In Istvan Kecskes (ed.), The Cambridge handbook of intercultural pragmatics, 216–244. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/9781108884303.010Search in Google Scholar

Bowdle, Brian F. & Dedre Gentner. 2005. The career of metaphor. Psychological Review 112(1). 193–216. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295x.112.1.193.Search in Google Scholar

Božović, Petar. 2022. How are metaphors rendered in legal translation? A corpus-based study of the European Court of Human Rights judgments. The Journal of Specialised Translation 38. 277–297.10.26034/cm.jostrans.2022.092Search in Google Scholar

Cameron, Lynne. 2003. Metaphor in educational discourse. London & New York: Continuum.Search in Google Scholar

Carston, Robyn. 2017. Relevance theory and metaphor. In Elena Semino & Zsófia Demjén (eds.), The Routledge handbook of metaphor and language, 42–55. Oxon & New York: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Chen, Yi-Chen. 2017. An investigation into EFL learners’ translations of metaphors from cognitive and cultural perspectives. International Journal of Comparative Literature and Translation Studies 5(3). 32–43. https://doi.org/10.7575/aiac.ijclts.v.5n.3p.32.Search in Google Scholar

Cheung, Martha P. Y. 2005. ‘To translate’ means ‘to exchange’? A new interpretation of the earliest Chinese attempts to define translation (‘fanyi’). Target 17(1). 27–48. https://doi.org/10.1075/target.17.1.03che.Search in Google Scholar

Cuccio, Valentina. 2018. Attention to metaphor: From neurons to representations. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.10.1075/milcc.7Search in Google Scholar

Dąbrowska, Ewa. 2016. Cognitive Linguistics’ seven deadly sins. Cognitive Linguistics 27(4). 479–491. https://doi.org/10.1515/cog-2016-0059.Search in Google Scholar

Dagut, Menachem. 1976. Can “metaphor” be translated? Babel 22(1). 21–33. https://doi.org/10.1075/babel.22.1.05dag.Search in Google Scholar

Dancygier, Barbara. 2017. Figurativeness, conceptual metaphor, and blending. In Elena Semino & Zsófia Demjén (eds.), The Routledge handbook of metaphor and language, 28–41. Oxon & New York: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

de Vries, Clarissa, W. Gudrun Reijnierse & Roel M. Willems. 2018. Eye movements reveal readers’ sensitivity to deliberate metaphors during narrative reading. Scientific Study of Literature 8(1). 135–164. https://doi.org/10.1075/ssol.18008.vri.Search in Google Scholar

Dickins, James. 2005. Two models for metaphor translation. Target 17(2). 227–273. https://doi.org/10.1075/target.17.2.03dic.Search in Google Scholar

Dorst, Aletta G. 2017. Textual patterning of metaphor. In Elena Semino & Zsófia Demjén (eds.), The Routledge handbook of metaphor and language, 178–192. Oxon & New York: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Fauconnier, Gilles & Mark Turner. 2002. The way we think: Conceptual blending and the mind’s hidden complexities. New York: Basic Books.Search in Google Scholar

Franco Aixelá, Javier. 2001–2024. BITRA: Bibliografía de interpretación y traducción. https://doi.org/10.14198/bitra.Search in Google Scholar

Gambier, Yves & Luc van Doorslaer (eds.). 2024. Translation studies bibliography. https://doi.org/10.1075/tsb.Search in Google Scholar

Goatly, Andrew. 2011. The language of metaphors, 2nd edn. Abingdon & New York: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Gola, Elisabetta & Francesca Ervas (eds.). 2016. Metaphor and communication. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.10.1075/milcc.5Search in Google Scholar

Grave, Isobel. 2016. Mediating metaphor in English translations of Dante’s Inferno, Canto 13. Perspectives 24(3). 393–416. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676x.2015.1113999.Search in Google Scholar

Halverson, Sandra L. & Álvaro Marín García (eds.). 2022. Contesting epistemologies in cognitive translation and interpreting studies. Oxon & New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781003125792Search in Google Scholar

Halverson, Sandra L. & Ricardo Muñoz Martín. 2021. The times, they are a-changin’: Multilingual mediated communication and cognition. In Ricardo Muñoz Martín & Sandra L. Halverson (eds.), Multilingual mediated communication and cognition, 1–17. London: Routledge.10.4324/9780429323867-1Search in Google Scholar

He, Sui. 2021. Cognitive metaphor theories in translation studies: Toward a dual-model parametric approach. Intercultural Pragmatics 18(1). 25–52. https://doi.org/10.1515/ip-2021-0002.Search in Google Scholar

Heilmann, Arndt, Tatiana Serbina & Stella Neumann. 2018. Processing of grammatical metaphor: Insights from controlled translation and reading experiments. Translation, Cognition & Behavior 1(2). 195–220. https://doi.org/10.1075/tcb.00009.hei.Search in Google Scholar

Hong, Wenjie & Caroline Rossi. 2021. The cognitive turn in metaphor translation studies: A critical overview. Journal of Translation Studies 5(2). 83–115.Search in Google Scholar

Koglin, Arlene. 2015. An empirical investigation of cognitive effort required to post-edit machine translated metaphors compared to the translation of metaphors. Translation & Interpreting 7(1). 126–141.Search in Google Scholar

Koglin, Arlene & Rossana Cunha. 2019. Investigating the post-editing effort associated with machine-translated metaphors: A process-driven analysis. The Journal of Specialised Translation 31. 38–59.10.26034/cm.jostrans.2019.176Search in Google Scholar

Königs, Frank G. 1990. ‘Die Seefahrt an den Nagel hängen’? Metaphern beim Übersetzen und in der Übersetzungswissenschaft [‘Give up seafaring’? Metaphors in translation and translation studies]. Target 2(1). 97–113. https://doi.org/10.1075/target.2.1.06kon.Search in Google Scholar

Kövecses, Zoltán. 2002. Metaphor: A practical introduction. New York: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780195145113.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Kövecses, Zoltán. 2014. Conceptual metaphor theory and the nature of difficulties in metaphor translation. In Donna R. Miller & Enrico Monti (eds.), Tradurre figure/Translating figurative language, 25–39. Bologna: Bononia University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Kövecses, Zoltán. 2017. Conceptual metaphor theory. In Elena Semino & Zsófia Demjén (eds.), The Routledge handbook of metaphor and language, 13–27. Oxon & New York: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Kuckartz, Udo. 2014. Qualitative text analysis: A guide to methods, practice and using software, 2nd edn. London: Sage.10.4135/9781446288719Search in Google Scholar

Lakoff, George & Mark Johnson. 1980. Metaphor we live by. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.Search in Google Scholar

Marín García, Álvaro & Sandra, L. Halverson. 2022. Introduction: Scientific maturity and epistemological reflection in cognitive translation and interpreting studies (CTIS). In Sandra, L. & Álvaro, Marín (eds.), Contesting epistemologies in cognitive translation and interpreting studies, 1–8. Oxon & New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781003125792-1Search in Google Scholar

Miller, Donna R. & Enrico Monti (eds.). 2014. Tradurre figure/Translating figurative language. Bologna: Bononia University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Munday, Jeremy, Sara Ramos Pinto & Jacob Blakesley. 2022. Introducing translation studies: Theories and applications, 5th edn. London: Routledge.10.4324/9780429352461Search in Google Scholar

Musolff, Andreas, Fiona MacArthur & Giulio Pagani (eds.). 2015. Metaphor and intercultural communication. London: Bloomsbury.10.5040/9781472593610Search in Google Scholar

Newmark, Peter. 1980. The translation of metaphor. Babel 26(2). 93–100. https://doi.org/10.1075/babel.26.2.05new.Search in Google Scholar

Nida, Eugene A. 1964. Toward a science of translating: With special reference to principles and procedures involved in Bible translating. Leiden: E. J. Brill.10.1163/9789004495746Search in Google Scholar

Olalla-Soler, Christian, Javier Franco Aixelá & Sara Rovira-Esteva. 2020. Mapping cognitive translation and interpreting studies: A bibliometric approach. Linguistica Antverpiensia, New Series – Themes in Translation Studies 19. 25–52.10.52034/lanstts.v19i0.542Search in Google Scholar

Pedersen, Jan. 2015. On the subtitling of visualised metaphors. The Journal of Specialised Translation 23. 162–180.10.26034/cm.jostrans.2015.344Search in Google Scholar

Pöchhacker, Franz. 2022. Introducing interpreting studies, 3rd edn. London: Routledge.10.4324/9781003186472Search in Google Scholar

Ramos Caro, Marina. 2016. La traducción de los sentidos: audiodescripción y emociones [Translating the senses: Audio description and emotions]. Munich: Lincom.Search in Google Scholar

Reijnierse, W. Gudrun, Christian Burgers, Tina Krennmayr & Gerard Steen. 2019. Metaphor in communication: The distribution of potentially deliberate metaphor across register and word class. Corpora 14(3). 301–326. https://doi.org/10.3366/cor.2019.0176.Search in Google Scholar

Schäffner, Christina. 2004. Metaphor and translation: Some implications of a cognitive approach. Journal of Pragmatics 36(7). 1253–1269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2003.10.012.Search in Google Scholar

Schäffner, Christina. 2017. Metaphor in translation. In Elena Semino & Zsófia Demjén (eds.), The Routledge handbook of metaphor and language, 247–262. Oxon & New York: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Schmaltz, Márcia. 2018. Problem solving in the translation of linguistic metaphors from Chinese into Portuguese: An empirical-experimental study. In Callum Walker & Federico M. Federici (eds.), Eye tracking and multidisciplinary studies on translation, 121–144. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/btl.143.07schSearch in Google Scholar

Semino, Elena. 2008. Metaphor in discourse. Cambridge & New York: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511816802.015Search in Google Scholar

Semino, Elena & Jonathan Culpeper (eds.). 2002. Cognitive stylistics: Language and cognition in text analysis. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.10.1075/lal.1Search in Google Scholar

Serbina, Tatiana & Stella Neumann. 2022. Translation product and process data: A happy marriage or worlds apart? In Sandra L. Halverson & Álvaro Marín García (eds.), Contesting epistemologies in cognitive translation and interpreting studies, 131–152. Oxon & New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781003125792-9Search in Google Scholar

Shuttleworth, Mark. 2014. Translation studies and metaphor studies: Possible paths of interaction between two well-established disciplines. In Donna R. Miller & Enrico Monti (eds.), Tradurre figure/Translating figurative language, 53–65. Bologna: Bononia University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Sjørup, Annette C. 2013. Cognitive effort in metaphor translation: An eye-tracking and key-logging study. Frederiksberg: Copenhagen Business School Doctoral thesis.Search in Google Scholar

Snell-Hornby, Mary. 1988. Translation studies: An integrated approach. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/z.38Search in Google Scholar

Sperber, Dan & Deirdre Wilson. 1995. Relevance: Communication and cognition, 2nd edn. Oxford: Blackwell.Search in Google Scholar

Steen, Gerard. 2004. Can discourse properties of metaphor affect metaphor recognition? Journal of Pragmatics 36(7). 1295–1313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2003.10.014.Search in Google Scholar

Steen, Gerard. 2008. The paradox of metaphor: Why we need a three-dimensional model of metaphor. Metaphor and Symbol 23(4). 213–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926480802426753.Search in Google Scholar

Steen, Gerard. 2015. Developing, testing and interpreting deliberate metaphor theory. Journal of Pragmatics 90. 67–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2015.03.013.Search in Google Scholar

Steen, Gerard. 2017. Deliberate metaphor theory: Basic assumptions, main tenets, urgent issues. Intercultural Pragmatics 14(1). 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1515/ip-2017-0001.Search in Google Scholar

Steen, Gerard. 2023. Slowing metaphor down: Elaborating deliberate metaphor theory. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.10.1075/celcr.26Search in Google Scholar

Stockwell, Peter. 2002. Cognitive poetics: An introduction. London & New York: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Thibodeau, Paul. 2017. The function of metaphor framing, deliberate or otherwise, in a social world. Metaphor and the Social World 7(2). 270–290. https://doi.org/10.1075/msw.7.2.06thi.Search in Google Scholar

Wang, Yifang. 2021. The impact of directionality on cognitive patterns in the translation of metaphors. In Ricardo Muñoz Martín, Sanjun Sun & Defeng Li (eds.), Advances in cognitive translation studies, 201–220. Singapore: Springer.10.1007/978-981-16-2070-6_10Search in Google Scholar

Werkmann Horvat, Ana, Marianna Bolognesi & Nadja Althaus. 2023. Attention to the source domain of conventional metaphorical expressions: Evidence from an eye tracking study. Journal of Pragmatics 215. 131–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2023.07.011.Search in Google Scholar

Wong, Sum. 2024. Deliberate metaphor (use) in translation and interpreting: Is there such a thing? Metaphor and the Social World 14(2). 322–328. https://doi.org/10.1075/msw.24016.won.Search in Google Scholar

Xiao, Kairong & Ricardo Muñoz Martín. 2020. Cognitive translation studies: Models and methods at the cutting edge. Linguistica Antverpiensia, New Series – Themes in Translation Studies 19. 1–24.10.52034/lanstts.v19i0.593Search in Google Scholar

Zheng, Binghan & Xia Xiang. 2013. Processing metaphorical expressions in sight translation: An empirical-experimental research. Babel 59(2). 160–183. https://doi.org/10.1075/babel.59.2.03zhe.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Cognitive translation and interpreting studies – an evolving research area and a thriving community of practice

- Research Articles

- Reader differences in navigating English–Chinese sight interpreting/translation

- How does interpreting training affect the executive function of switching? A longitudinal EEG-study of task switching

- Stress and accent in community interpreting

- Many roads lead to Rome: an empirical study of summarizing translation processes

- Dancing with words: the emotional reception of creative audio description in contemporary dance

- Mapping metaphor research in translation and interpreting studies: a bibliometric analysis from 1964 to 2023

- Spotlight on the reader: methodological challenges in combining translation process, product, and translation reception

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Cognitive translation and interpreting studies – an evolving research area and a thriving community of practice

- Research Articles

- Reader differences in navigating English–Chinese sight interpreting/translation

- How does interpreting training affect the executive function of switching? A longitudinal EEG-study of task switching

- Stress and accent in community interpreting

- Many roads lead to Rome: an empirical study of summarizing translation processes

- Dancing with words: the emotional reception of creative audio description in contemporary dance

- Mapping metaphor research in translation and interpreting studies: a bibliometric analysis from 1964 to 2023

- Spotlight on the reader: methodological challenges in combining translation process, product, and translation reception