Abstract

The lexemes ‘fruit’ and ‘stone’ are known as the origins of the numeral classifiers for small round objects in many Tibeto-Burman languages. This paper employs a correlation-based network construction method to investigate the colexification networks of the two concepts in 58 + 68 Tibeto-Burman languages. A total of 104 concepts colexified with ‘fruit’ and 99 concepts colexified with ‘stone’ are organized into macro semantic classes. Semantic networks on the basis of the similarities in colexification patterns of concepts, as well as languages networks on the basis of the similarities in colexification patterns of languages, are constructed for ‘fruit’ and ‘stone’, respectively. The results indicate that classifiers for small round objects evolved from either ‘fruit’ or ‘stone’ are directly colexified with class terms in compound nouns denoting varieties of fruits/stones and the shape class of small round objects, indicating that they are diachronically related. However, ‘fruit’ and ‘stone’ differ significantly in their modes of deriving a classifier. Moreover, languages that have developed classifiers from ‘fruit’ are mostly from the Ngwi subgroup, whereas languages whose classifiers are colexified with ‘stone’ evolved independently.

1 Introduction: the etymology of classifiers for small round objects

Languages from the Tibeto-Burman (TB) family vary in the presence/absence and the degree of grammaticalization of numeral classifier system (Jiang 2009). Some subgroups of TB languages are known for the scarcity of numeral classifiers (e.g. Bodish and Kuki-Chin-Naga), while other subgroups (e.g. Karenic, Baic, Burmic) have full-fledged classifier systems. Numeral classifiers were not part of the proto-Sino-Tibetan language, but evolve individually in quite a few of the languages in the family (LaPolla 2017: 46, cf. Xu 1987, 1989; Dai 1994, 1997a, 1997b). Classifiers are not reconstructed for Proto-Tibeto-Burman (PTB) either (Matisoff 2003). It is thus important to know when and how numeral classifiers were developed in this family, as well as what caused the differences in the degree of grammaticalization.

Like many nearby East and Southeast Asian languages, Tibeto-Burman numeral classifiers are mostly derived from nouns (Aikhenvald 2000, 2022; Bisang 1996; DeLancey 1986). There is a highly frequent type of classifiers attested in almost every classifier language of this family – the wide-spread classifiers for small round or 3-dimensional objects (hereafter 3D-classifier) – were derived from different etymological sources. Despite the absence of a proto-form in PTB, this classifier has been hypothesized to exist in many proto languages in different subgroups of Tibeto-Burman (e.g. Wood 2008; Ebert 1994; Kazuyuki 2009; Malla 1990; Genetti 2007, 2017; Sun 1993; Post and Sun 2017; Bradley 1979, 2012; Hansson 2017; Luangthongkum 2013, inter alia).

The etymology of 3D-classifiers in TB is complex. It can be evolved from the concepts of ‘fruit’ (Proto-Bodo-Garo and Proto-Ngwi, cf. Wood 2008; Bradley 1979), ‘stone’ (Proto-Bodo-Garo and Proto-Karen, cf. Wood 2008; Luangthongkum 2013), ‘egg/testicle’ (Classic Newar and Burmic, cf. Kazuyuki 2009; Bradley 2012), ‘round things’ (Proto-Burmic, cf. Bradley 2012), the affix meaning ‘mother/female’ (Ngwi, Zhang 2016), among others. In the grammaticalization of classifiers, nominal compounding is an important historical stage (Aikhenvald 2022; Bisang 1993; DeLancey 1986). Among those concepts, lexemes with the lexical meanings ‘fruit’ and ‘stone’ are identified as two common sources of 3D-classifiers crosslinguistically, including in many Southeast Asian languages, and ‘fruit’ may further develop into a general classifier that classifies all inanimate nouns (Aikhenvald 2000, 2021).

Matisoff (2003) has reconstructed two etyma for the lexeme ‘fruit’ in Proto-Tibeto-Burman (PTB), namely *sey ‘fruit/rose/round object’(#1019[1]) and *b-ras ‘rice/fruit/bear fruit/round object’ (#2071). Both etyma also mean ‘round objects’. *sey is the dominant proto-form for ‘fruit’ throughout the Tibeto-Burman family while *b-ras is only found in Tibetan, Northern and Central Chin,[2] and a few Bodo and rGyalrong languages.

The morpheme ‘fruit’ often appears as a “class term” (CT) (DeLancey 1986) in compound nouns denoting various kinds of fruits. Fruits containing a ‘fruit’ CT mostly have a round shape, involving apple, fig, grape, lime, mango, melon, peach, pear, persimmon, banana, pomegranate, tangerine, and nuts, among others. Table 1 displays languages that employ the CT derived from the PTB *sey ‘fruit’ in compounds denoting fruits.

CT ‘fruit’ < PTB *sey ‘fruit/rose/round object’.

| Subgroup | Language | Word form | Gloss | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ngwi | Lisu | si 35 sɯ 31 | ‘fruit’ | Bradley (2012) |

| tɕhe̱ 31 le̱ 31 sɯ 31 | ‘grape’ | |||

| sɯ 31 lɯ̱ 33 bɯ 33 | ‘persimmon’ | |||

| Burmish | Longchuan Achang | ʂə 31 | ‘fruit’ | Huang (1992); Hill and List (2017) |

| ʂə 31 om 31 | ‘peach’ | |||

| Deng | Yidu | ɹuŋ 55 ɕi 55 | ‘fruit’ | Huang (1992) |

| ɑ 31 jim 55 ɕi 55 | ‘grape’ | |||

| ɑ 55 mu 55 ɕi 55 | ‘peach’ | |||

| Kiranti | Bahing | siː tsi | ‘fruit’ | Michailovsky (1989) |

| gramu tsi | ‘banana’ | |||

| khɔmal tsi | ‘peach’ | |||

| Jingpho | Jingpho | si 31 ;nam 31 si 31 | ‘fruit’ | Huang (1992) |

| să 55 pjiʔ 55 si 31 | ‘grape’ | |||

| Bodo-Garo | Garo | bi- te | ‘fruit’ | Burling (2003) |

| te •-rik | ‘banana’ | |||

| te •-ga-chu | ‘mango’ |

The etymon *sey is also frequently found in compounds referring to seeds/grains, body parts, small animals, and other small inanimate objects with the round shape. Table 2 presents languages employing the PTB etymon *sey ‘fruit’ in compounds referring to small and round objects.

CT ‘small round object’ < PTB *sey ‘fruit/rose/round object’.

| Subgroup | Language | Word form | Gloss | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ngwi | Lüchun Hani | si 31 | ‘fruit’ | Huang (1992) |

| tshe 55 si 31 | ‘rice (unhusked)’ | |||

| ɣø 31 si 31 | ‘kidney’ | |||

| phe 55 si 31 | ‘button’ | |||

| Kiranti | Bahing | si | ‘fruit’ | Michailovsky (1989) |

| nœgat si | ‘ear’ | |||

| nam si | ‘grain’ | |||

| mo si | ‘hail’ | |||

| Burmish | Rangoon Burmese | ɑ 53 tθi 55 | ‘fruit’ | Huang (1992) |

| mo 55 tθi 55 | ‘hail’ | |||

| Nungic | Dulong | ɕiŋ 55 ɕi 55 ;ɕi 53 | ‘fruit’ | Huang (1992) |

| tɯ31 ɕi 55 | ‘gall bladder’ | |||

| Jingpho | Jingpho | si 31 ;nam 31 si 31 | ‘fruit’ | Huang (1992) |

| tsoʔ 31 si 31 | ‘key’ | |||

| tiŋ 31 si 31 | ‘bell’ | |||

| Bodic | Motuo Menba | se | ‘fruit’ | Huang (1992) |

| toŋ toŋ se | ‘uvula’ | |||

| Bodo-Garo | Garo | bi- te | ‘fruit’ | Burling (2003) |

| sil- te | ‘hail’ |

The etymon *sey may develop into a sortal classifier for small and round objects or a mensural classifier, which is mostly from the sub-branches of Ngwi and Burmish. Examples in Table 3 illustrate that the Lüchun Hani cognate si 31 ‘fruit’ (< PTB *sey) and the Mojiang Hani cognate ɕi 31 ‘fruit’ can serve to classify small round objects like eggs, stones, grain of rice, and bowls. The Zaiwa (Atsi) cognate ʃi 21 ‘fruit’ is used as a standard measure classifier meaning ‘fingersbreath’; ‘fruit’ in the Lüchun and Mojiang dialects of Hani can be used as a measurement of time, meaning ‘month’s (work)’.

Sortal/mensural classifier < PTB *sey ‘fruit/rose/round object’.

| Subgroup | Language | Word form | Gloss | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ngwi | Lüchun Hani | si 31 | ‘fruit’ | Huang (1992) |

| si 31 | ‘CL:eggs/stones’ ‘CL:month’s work’ |

|||

| Mojiang Hani | ɔ 31 ɕi 31 | ‘fruit’ | Huang (1992) | |

| ɕi 31 | ‘CL:eggs/grain of rice’ ‘CL:month’s work’ |

|||

| Burmish | Zaiwa (Atsi) | ʃi 21 | ‘fruit’ | Huang (1992) |

| ʃi 21 | ‘CL:fingersbreath’ |

The etymon *b-ras referring to ‘fruit’ and ‘rice’ may appear in the root of both concepts, as in Old Tibetan (Tibetan) (e.g. ɦbras bu ‘fruit’ and ɦbras ‘rice’) (Sun 1991; Huang 1992). However, unlike *sey, this etymon has limited productivity in deriving nouns in Old Tibetan. Except for ‘rice’, none of the aforementioned shape classes contain the morpheme ɦbras. Lushai is the other language has the etymon *b-ras. But the Lushai rah ‘fruit’ did not derive any nouns referring to small round objects (cf. Bhaskararao 1996; VanBik 2009).

It should be noted that there exists another etymon *si(ŋ/k) (#2658) in PTB, glossed as ‘tree/wood/firewood’ (Matisoff 2003), that is colexified with ‘fruit’ in several sub-groups of TB, as presented in Table 4. The lexeme ‘fruit’ is frequently found in compound nouns with reference to plants/plant parts and the related wood and wood products. For example, the Bahing and Hayu cognate si is most plausibly a root meaning ‘plant’, which is found in concepts with reference to ‘fruit’, ‘tree’, and plant parts. The root sî ‘tree’ in old Burmese also appears in the root for ‘fruit’, marking ‘fruit’ as a part of plant. In Xide Yi and old Tibetan, the cognates sɿ̄ 33 and ɕiŋ appear in nouns meaning ‘fruit’, ‘tree’, and wood products. It is posited that *si(ŋ/k) is a general class term for ‘plant’ that covers both ‘fruit’ and ‘tree’. It was narrowed down to ‘fruit’ in some languages (e.g. Yi) but in others it remained as a morpheme meaning ‘plant’ (Qumutiexi 2010).

Colexification of PTB *sey ‘fruit/rose/round object’ and PTB *si(ŋ/k) ‘tree/wood/firewood’

| Subgroup | Language | Word form | Gloss | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kiranti | Bahing | si | ‘fruit’; ‘tree’ | Michailovsky (1989) |

| dhɛk si | ‘tree’ | |||

| toː si | ‘pine tree’ | |||

| prypt si | ‘bud’ | |||

| Hayu | si | ‘fruit’ | Michailovsky (1989) | |

| dõː si | ‘plant’ | |||

| kok si | ‘fodder tree’ | |||

| Burmish | Old Burmese | ə- sî | ‘fruit’ | Benedict (1976) |

| sî | ‘kind of tree’ | |||

| Ngwi | Xide Yi | sɿ̄ 33 dzɑ 33 lu̱ 33 mɑ 33 | ‘fruit’ | Sun (1991); Huang (1992) |

| sɿ̄ 33 bo 33 | ‘tree’ | |||

| sɿ̄ 33 ḷ(u̱) 33 sɿ̄ 33 tɕe 33 | ‘wood’ | |||

| sɿ̄ 33 phi 21 | ‘plank/board’ | |||

| Tibetan | Old Tibetan | ɕiŋ tog | ‘fruit’ | Sun (1991) |

| ɕiŋ ɦdzer | ‘wedge’ | |||

| ɕiŋ | ‘wood’ | |||

| gȵaɦ ɕiŋ | ‘yoke’ |

Three etyma are reconstructed for ‘stone’ in Matisoff (2003), including *r-lu(ŋ/k) (#1269), *b-rak (#2166), and *suaŋ (#4677). *r-lu(ŋ/k) prevails the entire Tibeto-Burman family. *b-rak is a salient feature of Central and Southern Ngwi.[3] It is also a common etymon of ‘stone/rock’ in many Tibetan languages. In addition to Ngwi and Tibetan, this proto-form is found in a few languages from the subgroups of Tani, Garo, Jingpho, Tibeto-Kanauri, Kiranti, rGyalrong, Nungic, and Tujia. *suaŋ is much rarer, only attested in Peripheral Chin.

The morpheme ‘stone’ regularly occurs as a class term (CT) in the compound nouns with reference to different varieties of rocks and stones, ranging from rocks and stones in the nature (i.e. boulder, cave, cliff, pebble, coral, limestone) to products made of stone/rock (i.e. millstone, whetstone, hearth-stone, wall, flight of steps). The etymon *r-lu(ŋ/k) (#1269) is the most productive form found in compounds for varieties of rocks and stones and *b-rak (#2166) is much less frequent. Table 5 gives examples from different subgroups that contain the CT ‘stone’ in compounds for various types of stones and rocks.

CT ‘stone’ < PTB *r-lu(ŋ/k)/*b-rak ‘stone/rock’.

| Etymon | Subgroup | Language | Word form | Gloss | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| *r-lu(ŋ/k) | Western Tani | Bokar | ɯ lɯŋ | ‘stone’ | Huang (1992); Sun (1993) |

| lɯŋ -duŋ | ‘boulder/huge rock/cliff’ | ||||

| lɯŋ pɯk | ‘cave(mountain)’ | ||||

| lɯŋ -reː | ‘pebble’ | ||||

| Nungic | Dulong | luŋ 55 | ‘stone’ | Huang (1992) | |

| ɑ 31 pɹɑʔ 55 luŋ 55 | ‘rock’ | ||||

| luŋ 55 pɑŋ 55 | ‘cave/hole’ | ||||

| tɕɑ 31 mɑʔ 55 luŋ 55 | ‘flint’ | ||||

| Ngwi | Lisu | lo̱ 33 | ‘stone’ | Huang (1992) | |

| ɕo 31 lo̱ 33 | ‘coral’ | ||||

| tɕhɛ 35 dʑɯ̱ 31 lo̱ 33 | ‘flint’ | ||||

| lo̱ 33 kho 31 | ‘valley’ | ||||

| *b-rak | Tujia | Tujia | ɣa 21 (pa 21 ) | ‘stone’ | Sun (1991) |

| ɣa 21 kho 21 | ‘rock/cliff’ | ||||

| Ngwi | Lancang Lahu | xɑ 35 pɯ 33 ɕi 11 | ‘stone’ | Huang (1992) | |

| xɑ 35 pɯ 33 | ‘rock’ | ||||

| xɑ 35 pɯ 33 go 33 | ‘flight of steps’ | ||||

| xɑ 35 tshi 33 | ‘cliff’ | ||||

| ɑ 31 mi 11 xɑ 33 pɯ 33 | ‘flint’ |

The etymon for ‘stone’ also frequently appears in compound nouns with reference to small round animals, body parts, and inanimate objects. The etymon *r-lu(ŋ/k) (#1269) is the most productive etymon found in this type of compounds, whereas *b-rak (#2166) is less productive in deriving nouns of small round shape (Table 6).

CT ‘small round object’ < PTB *r-lu(ŋ/k)/*b-rak ‘stone/rock’.

| Etymon | Subgroup | Language | Word form | Gloss | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| *r-lu(ŋ/k) | Western Tani | Bokar | ɯ lɯŋ | ‘stone’ | Sun (1993) |

| jup- lɯŋ -ki-bo | ‘caterpillar’ | ||||

| lɯŋ guŋ | ‘neck/throat’ | ||||

| lɯŋ ɕuk | ‘trivet’ | ||||

| Nungic | Dulong | luŋ 55 | ‘stone’ | Huang (1992) | |

| luŋ 55 dʑin 53 | ‘ginger’ | ||||

| ɑm 55 luŋ 55 | ‘(unhusked) rice’ | ||||

| nɯ 31 lɛŋ 31 luŋ 55 | ‘testicle’ | ||||

| Kiranti | Limbu | luŋ | ‘stone’ | Michailovsky (1989) | |

| luŋ si | ‘maggot’ | ||||

| luŋ ma | ‘heart’ | ||||

| Ngwi | Lisu | lo̱ 33 | ‘stone’ | Sun (1991); Huang (1992) | |

| bo̱ 31 lo̱ 33 | ‘ant’ | ||||

| o 55 go̱ 31 lo̱ 33 | ‘pillow’ | ||||

| po 44 lo 44 | ‘bullet’ | ||||

| *b-rak | Tibetan | Batang Tibetan | tshɑʔ 53 | ‘pit/stone’ | Huang (1992) |

| tshɑʔ 53 | ‘sieve / sifter’ | ||||

| tɕa 13 tshɑʔ 53 gẽ 55 mo 53 | ‘locust’ | ||||

| Ngwi | Lancang Lahu | xɑ 35 pɯ 33 ɕi 11 | ‘stone’ | Huang (1992) | |

| xɑ 35 pɯ 33 qɑ 11 | ‘turtledove’ | ||||

| xɑ 35 pɯ 33 ɕi 35 ɣɤ 21 | ‘coal’ |

Like ‘fruit’, the etymon *r-lu(ŋ/k) (#1269) ‘stone’ has derived a handful of numeral classifiers classifying small round objects in several Tibeto-Burman languages, as shown in Table 7. However, Burmic languages (i.e. mostly Ngwi) did not derive 3D-classifiers from ‘stone’ but rather from ‘fruit’. ‘Stone’ and ‘fruit’ are in complementary distribution in forming numeral classifiers in the Burmic subgroup. Concepts classified by a classifier evolved from *r-lu(ŋ/k) ‘stone’ typically have the round shape, ranging from stones/rocks, eggs, bowls, to grains. No evidence in the available sources shows that the other etymon *b-rak for ‘stone’ has derived numeral classifiers in Tibeto-Burman.

Sortal classifier < PTB *r-lu(ŋ/k)/PTB *b-rak ‘stone/rock’.

| Subgroup | Language | Word form | Gloss | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Karenic | Karen | lø 31 | ‘stone’ | Huang (1992) |

| ph lø 31 | ‘CL:eggs/grain (of rice)/ rocks/stones’ | |||

| Nungic | Dulong | luŋ 55 | ‘stone’ | Huang (1992) |

| luŋ 55 | ‘CL:eggs/grain (of rice)/ rocks/stones’ | |||

| Nung | ḷuŋ 55 | ‘stone’ | Huang (1992) | |

| (thi 31 ) ḷuŋ 55 | ‘CL:eggs/rocks/stones’ | |||

| Bodo-Garo | Garo | roŋ | ‘stone’ | Benedict (1972); Wood (2008) |

| roŋ -brak | ‘rock’ | |||

| roŋ- | ‘CL: round objects’ |

Both etyma for ‘stone’ may derive nouns with the denotation of human beings and gods. It is found in a handful of lexical forms for adult, man, girl, and grandchild. For example, the morpheme lʊ̃ ‘stone’ (< PTB *r-lu(ŋ/k)) is seen in lʊ̃ːtso ‘man/male’ in Hayu (Kiranti) (Michailovsky 1989); both ‘stone’ and ‘man’ are lụ in Tangut (rGyalrongic, Li 1997). Similar extension has been attested in Lyuzu, Naxi, and Limbu too (cf. Huang 1992; Michailovsky 1989). The occurrence of *b-rak in nouns referring to humans/gods is found in Batang Tibetan (e.g. tshɑʔ 53 ‘stone’, mba 13 tshɑʔ 53 ‘person with pockmarked face’, cf. Huang 1992) and Lancang Lahu (e.g. xɑ 35 ‘stone’, xɑ 35 ɯ 11 phɑ 53 ‘adult’, ʑa 53 mi 53 xɑ 35 ‘girl’).

Occasionally, the etyma for ‘stone/rock’ are found in nouns encoding directions and predicates encoding process/property. For example, lɯm 55 ‘stone’ in Taraon Darang (Deng) is a part of the compound lɯm 55 koŋ 55 ‘inside’ (Sun 1991); in Old Burmese (Burmish), the noun kyok ‘stone’ is also used as the verb for ‘kick’ or ‘push off (boat)’ (Benedict 1976; Hansson 1989).

From the data presented above, we may conclude that though ‘fruit’ and ‘stone’ were etymologically distinct nouns, they seem to evolve into the same shape-based numeral classifier via a highly identical path in semantic extension. Nevertheless, the above generalizations are primarily based on empirical data collected from individual languages. It is not known to what extent patterns of semantic extension from the same noun origin converge in languages with and without such a classifier, and under what condition a noun for ‘fruit’ or ‘stone’ will develop into a classifier. In this study, two questions are addressed with respect to this. The first question concerns the mechanism behind the evolution of numeral classifier: is there any salient path of semantic extension associated with the derivation of a classifier for 3-dimensional objects from ‘fruit’ and ‘stone’? Second, if yes how effective it is in predicting the presence/absence of a classifier in a particular language? Tibeto-Burman languages diverge largely in the grammaticalization of a classifier, making them an ideal objective to examine the similarity/divergence in semantic extension of a concept and the result of it.

With this research objective, the approach of semantic network (§2.2) is used to construct the colexification network (Jackson et al. 2019) of the lexeme ‘fruit’ and ‘stone’ in over 60 Tibeto-Burman languages. By examining the structure of the colexification network of ‘fruit’/ ‘stone’, we aim to 1) identify any semantic colexification patterns of ‘fruit’/‘stone’ that are indicative of the development of a classifier in Tibeto-Burman languages from distinct subgroups, and 2) evaluate the effectiveness of the colexification patterns in explaining the presence/absence of a classifier in a particular language.

In the sections below, we will first outline the methods in §2, including the data sampling procedure and a network-based approach that generates the colexification networks of ‘fruit’ and ‘stone’. The result of the network analysis will be presented in §3. The crosslinguistic colexification patterns of ‘fruit’ and ‘stone’ will be carefully examined in this section. Specific paths of semantic extension from nouns to 3D-classifiers in each concept network will be inspected in §4. In §5, we will discuss the common path of semantic extension from a noun to a numeral classifier, as well as distinct colexification patterns governing the derivation of a classifier from ‘fruit’ and ‘stone’. §6 concludes the paper.

2 Methods

2.1 Dataset

A sample of 58 + 68 languages are collected on the basis of Sagart et al. (2019) to study the colexification patterns of ‘fruit’ and ‘stone’, respectively (i.e. see Appendix 1). Data collection and curation followed the following steps:

By querying the concepts ‘the fruit’ and ‘the stone’ in the database of Sagart et al. (2019),[4] (https://dighl.github.io/sinotibetan/), two lists of languages containing the concepts ‘the fruit’ and ‘the stone’ in a sample of 117 Tibeto-Burman languages are compiled. The two lists are comprised of 19 cognate sets involving the lexeme ‘the fruit’ and 26 cognate sets involving the lexeme ‘the stone’ within the family of Tibeto-Burman. They are used as the starting points of the analysis. 104 languages are identified containing the concept ‘the fruit’ and 116 languages containing the concept ‘the stone’.

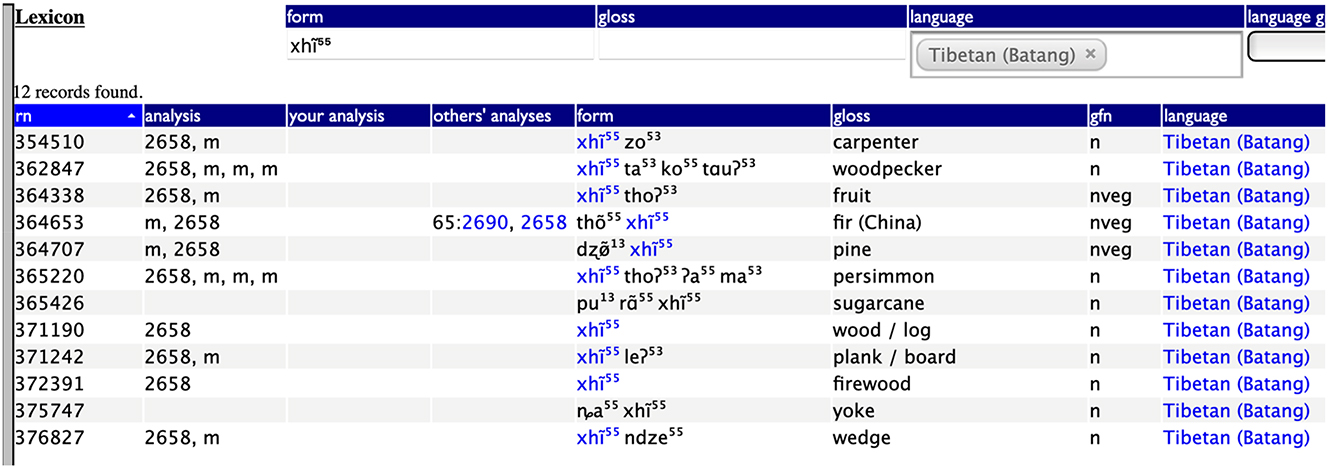

To ensure that word forms in a particular semantic network are derived from the same etymon, we use the database of STEDT[5] (Matisoff 2015) (https://stedt.berkeley.edu/∼stedt-cgi/rootcanal.pl) as the reference point.[6] Based on the word forms for the concepts ‘the fruit’ and ‘the stone’ in the two lists of languages, we searched words containing the morpheme(s) glossed as ‘fruit’ and ’stone’ in STEDT for each sampled language. Concepts that are colexified with ‘fruit’ and ‘stone’ in all sampled languages are gathered through this procedure. Since compounding is a productive strategy of word formation in the Tibeto-Burman family, the lexemes ‘fruit’ and ‘stone’ can be monosyllabic or disyllabic. The selection criteria is: if a word shares at least one syllable with the word ‘the fruit’/ ‘the stone’, it is included in the dataset for further analysis. By way of illustration, to compile the colexified word forms of ‘fruit’ in Tibetan (Batang), we first search the word(s) glossed as ‘fruit’ in STEDT. ‘Fruit’ in this language is a compound xhĩ 55 thoʔ 53 in which the first morpheme xhĩ 55 is derived from the etymon ‘TREE/WOOD/FIREWOOK’(#2658) in PTB. Word forms in STEDT containing either xhĩ 55 or thoʔ 53 are then obtained. Table 8 shows the word forms containing the form xhĩ 55 in Tibetan (Batang).

Word forms colexified with xhĩ 53 in Tibetan (Batang).

Manually annotate the proto-form and the etyma tag of the colexified lexical forms of ‘fruit’ and ‘stone’ for each language on the basis of the etyma tag (e.g. #2658 in Table 8) and the corresponding proto-form in STEDT.

Among the languages that are initially collected from step 1, languages in which the cognate set of ‘fruit’ and ‘stone’ is undetermined (Cog ID = 0) are excluded, except for languages with apparent cognates (e.g. Ngwi-Burmish languages all have the cognate of *sey for ‘fruit’). Consequently, the sample contains 58 languages for ‘fruit’ and 68 languages for ‘stone’.

Since colexification network only concerns polysemy (i.e. senses that are related), it is necessary to filter out homonyms (i.e. senses that are unrelated). A practical solution is to filter the spurious links on a colexification network, as they appear in only one or two languages (Di Natale and Garcia 2023; List et al. 2018; Rzymski et al. 2020). For this reason, we first sort the concepts by frequency in the language sample and remove the concepts that only occur in one language in the entire dataset.

Table I and Table II in Appendix 1 present the sampled languages and their subgroups, the word forms of ‘fruit’ and ‘stone’ in each language, the cognate set ID and the etymon tag in STEDT of each word form, and the number of concepts that have the same form as ‘fruit’ and ‘stone’ (i.e. colexify) in a particular language.

2.2 A network-based methodology

Network-based approaches, increasingly popular due to recent advancements in computational science and graph theory, have found wide application in diverse fields such as physics, psychology, and knowledge engineering (Castro and Siew 2020; Kenett and Faust 2019; Siew 2020). In semantics, these methods have proven especially beneficial. A semantic network, as outlined by Steyvers and Tenenbaum (2005), consists of nodes representing words/concepts, and links portraying the relationships between them. Semantic networks constructed within or across languages have thus facilitated investigations into a range of phenomena including semantic changes across the lifespan and bilingualism (Borodkin et al. 2016; Wulff et al. 2022), organization of nouns and verbs in the mental lexicon (Qiu et al. 2021), and cross-linguistic colexification (List et al. 2013).

There are several benefits to using semantic networks to analyze word meaning. First, network representation provides a powerful tool for visualizing semantic relations and dynamics, allowing researchers to easily identify patterns and structures that may not be apparent in other forms. In addition, network analysis techniques can help identify important properties and behaviors of semantic networks mathematically using graph theory. For example, network analysis can reveal the properties of individual nodes, as well as clusters, sub-networks, and the overall network. One of the most important node-level properties is the degree, which refers to the number of links a node has. Words/concepts with a high degree are highly connected to other words, and thus have a greater influence on the overall structure of the semantic network. Important cluster/network-level properties include the clustering coefficient (CC; a measure of the local density of links) and average shortest path length (ASPL; the average number of steps along the shortest paths for all pairs of nodes). When semantic networks exhibit high CC and low ASPL, they are considered to have a “small-world” structure. This type of structure is characterized by highly connected clusters of nodes, or “communities”, that are themselves relatively well connected to one another. At the same time, the network as a whole maintains short path lengths between any two nodes, allowing for efficient communication and the spread of information across the network (for a review, see Siew et al. 2019).

2.2.1 Network estimation method

To compute the colexification networks of ‘fruit’ and ‘stone’, we utilized a correlation-based network construction approach. The foundation of this approach is that meaningful semantic relationships can be quantified using measures such as correlation coefficients or cosine similarity, providing a numerical representation of the inherent organization and structure of concepts. This method has been successfully applied in the analysis of semantic relations from verbal fluency data, where each concept is represented as either produced (‘1’) or not produced (‘0’) across a set of participants (Borodkin et al. 2016; Siew and Guru 2023).

Similarly, for our study, we first created separate binary response matrices for ‘fruit’ and ‘stone’. Each column in the matrix denotes a colexified concept, each row represents a language from the Tibeto-Burman family, and each cell indicates whether the concept is present (‘1’) or absent (‘0’) in the respective language. We then calculated a symmetric association matrix by determining the cosine similarity between every pair of concepts.[7]

Following this, we constructed a weighted and undirected network by connecting concepts that had non-zero cosine similarity values. The Triangulated Maximally Filtered Graph (TMFG; Massara et al. 2017) method was then applied to eliminate links with weaker weights (lower cosine similarity values), while preserving the network’s triangulated nature. The TMFG method effectively removes edges that don’t contribute to the maximum degree sequence or to the network’s triangulated property, keeping the crucial structural properties of the original network intact.

Lastly, the resulting TMFG network was simplified further to an unweighted and undirected network by converting all edge weights to 1, which facilitates easier analysis and interpretation. Network estimation and analyses were conducted using the igraph (v1.3.5; Cśardi and Nepusz 2006) and NetworkToolbox (v1.4.2; Christensen 2018) packages in R (v4.2.3; R Core Team 2023). The implementation is publicly accessible on our GitHub repository at https://github.com/mengyangq/semantic_evolution.

2.2.2 Network measures

To evaluate the structural properties of the two colexification networks, we computed common node-level and network-level measures, including the degree distribution, average degree, clustering coefficient (CC), and average shortest path length (ASPL). We compared the CC and ASPL for each network against the same network measures obtained from 1,000 Erdős-Rényi random network simulations (Erdős and Rényi 1960) with the same number of nodes and edges as the colexification networks. A small-world structure is indicated by a CC that is much larger than CCrandom, and an ASPL that is similar to or slightly larger than ASPLrandom. We also conducted a one-sample z-test for the two measures to assess whether the colexification networks were structurally meaningful and significantly different from their corresponding random network simulations.

To further analyze the structure of the colexification networks, we also explored their community or cluster structure. This was achieved by utilizing the cluster_optimal function from the igraph package (Cśardi and Nepusz 2006). This function computes the optimal community structure of a graph, essentially categorizing nodes into groups or communities in a way that maximizes the measure of modularity across all possible partitions. By doing so, we can identify clusters of closely interconnected concepts within the larger network, thereby revealing additional layers of organization and offering further insights into the semantic relatedness of ‘fruit’ and ‘stone’ concepts across different languages.

2.2.3 Network stability

In this study, we also employed a bootstrapping approach to examine and compare the stability and structural characteristics of the ‘stone’ and ‘fruit’ networks (Borodkin et al. 2016). The analysis was grounded in generating 1,000 bootstrap iterations for each network. Each bootstrap iteration involved randomly selecting rows with replacement from the original binary matrices of the networks, followed by constructing a new network for each iteration, using the same network estimation method, as stated in §2.2.1. We then compared two key network metrics for these bootstrapped networks: CC and ASPL. To statistically compare the variability in these metrics between the two networks, we conducted Levene’s tests for homogeneity of variance.

3 Result of network analysis

3.1 Semantic classes colexified with ‘fruit’ and ‘stone’

Using the sampling procedure outlined in §2.1, 104 and 99 concepts are identified in the sampled languages that share at least one morpheme (i.e. colexify) with the lexeme ‘fruit’ and ‘stone’, respectively. Those concepts constitute the crosslinguistic colexification networks of the two nouns in Tibeto-Burman. In the initial sampling of languages, 58 languages are selected for ‘fruit’ and 68 for ‘stone’. Due to the existence of languages that do not colexify with any concept, 52 and 54 languages are eventually included in the network estimation of 'fruit' and 'stone', respectively.[8]

Concepts colexified with ‘fruit’ are subdivided into 11 semantic classes: varieties of fruits, seeds/grains, body parts, small animals, small round objects, plants/plant parts, wood/tree, human/god, process/property, classifiers, and miscellaneous. They can be further grouped into 7 macro semantic classes.[9] Concepts that are found in at least one language in the sample are included for analysis (i.e. Appendix 2, Table III). Table 9 presents the most frequent 10 concepts colexified with ‘fruit’ in the 58 sampled languages.

The frequency rank of concepts colexified with ‘fruit’ in 58 Tibeto-Burman languages.

| Concept | Number of languages | Semantic class |

|---|---|---|

| fruit | 58 | variety of fruits |

| bear fruit | 21 | process/property |

| peach | 18 | variety of fruits |

| persimmon | 15 | variety of fruits |

| rice (unhusked/glutinous/paddy/plant/uncooked) | 14 | seeds/grains |

| grape | 11 | variety of fruits |

| nut, seed (gen.); bead | 11 | seeds/grains |

| plantain, banana | 10 | variety of fruits |

| cucumber | 9 | variety of fruits |

| pear | 9 | variety of fruits |

Concepts colexified with ‘stone’ are also divided into 11 semantic classes: varieties of stones, tools, fabrics, body parts, small animals, small round objects, direction, process/property, human/god, numeral classifiers, and miscellaneous.[10] Table IV in Appendix 2 presents the concepts that are found in at least one language in the sample. Table 10 presents the most frequent 10 concepts containing the morpheme ‘stone’ in the 68 sampled languages.

The frequency rank of concepts colexified with ‘stone’ in 68 Tibeto-Burman languages.

| Concept | Number of languages | Semantic class |

|---|---|---|

| pit/stone/rock | 68 | varieties of stones |

| flint (to make fire) | 22 | varieties of stones |

| coal | 10 | varieties of stones |

| maggot, worm | 10 | small animals |

| pestle (small, stone) | 9 | varieties of stones |

| cliff / rocky outcrop | 7 | varieties of stones |

| heart, liver | 7 | body parts |

| flight of steps | 6 | varieties of stones |

| wall(stone) | 6 | varieties of stones |

| cave | 5 | varieties of stones |

3.2 Colexification networks of concepts

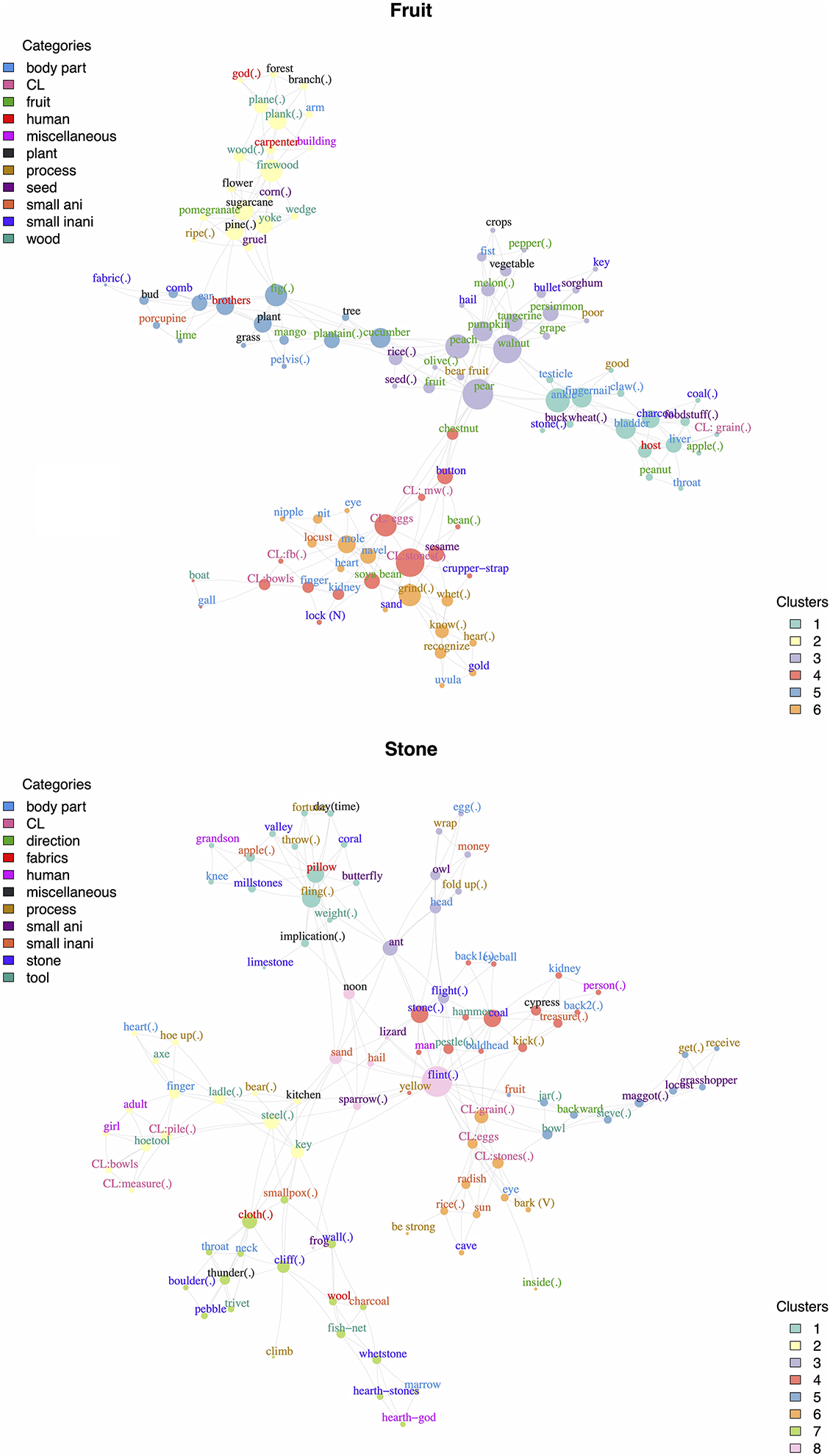

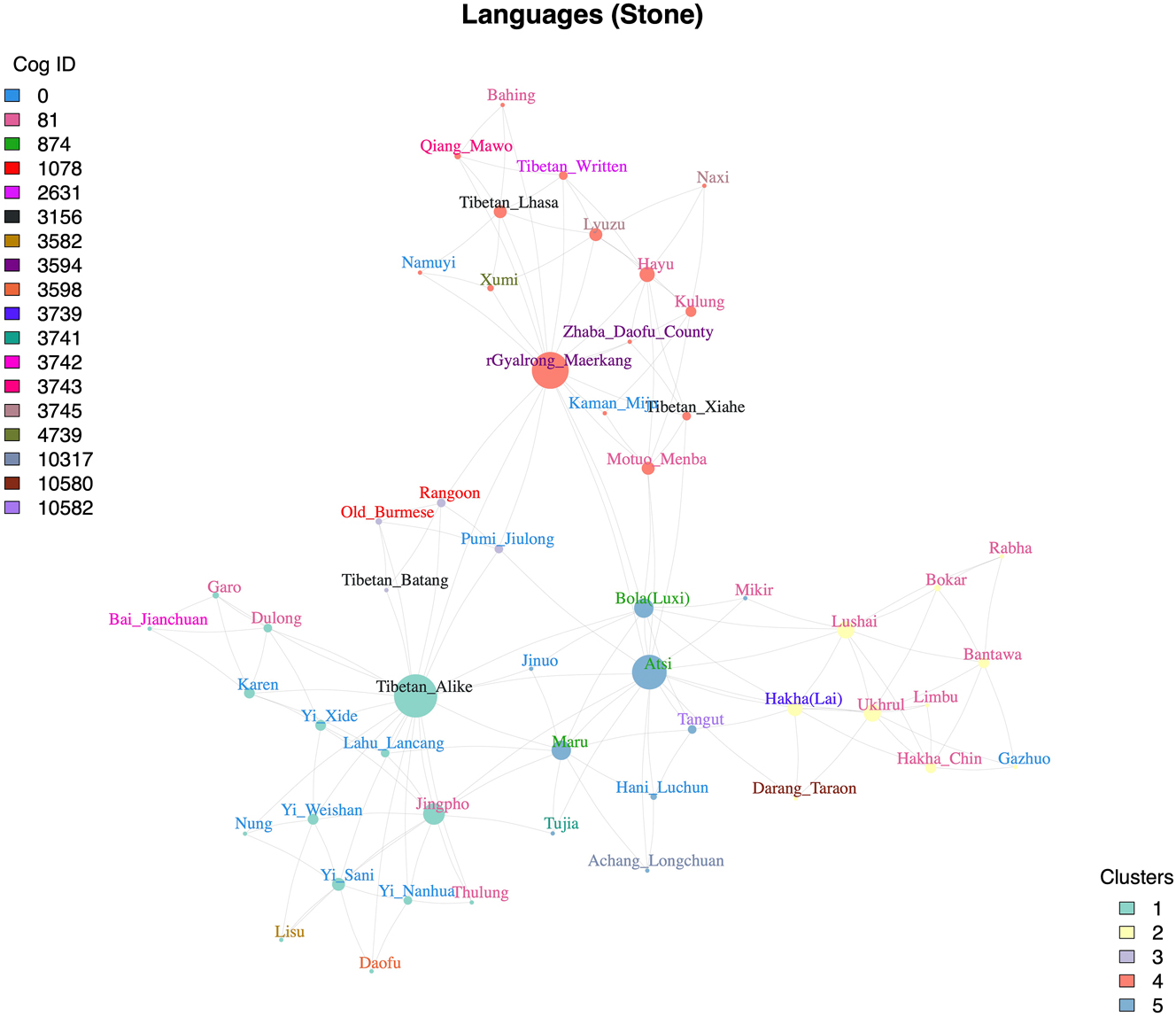

The network approach (§2.2) is applied to concepts colexified with ‘fruit’ (§3.2.1) and ‘stone’ (§3.2.2) to discover the structure of concepts in terms of their colexification similarity. The colexification networks of ‘fruit’ and ‘stone’ are characterized by Figure 1.

Colexification Network of ‘Fruit’ (top panel) and ‘Stone’ (bottom panel). In this visualization, varying text colors denote different semantic classes (§3.1) of concepts. Node colors signify distinct clusters within the network, illustrating how concepts are grouped based on their colexification patterns. The size of each node corresponds to the degree of the concept, with larger nodes indicating concepts that have a higher degree of colexification with other concepts.

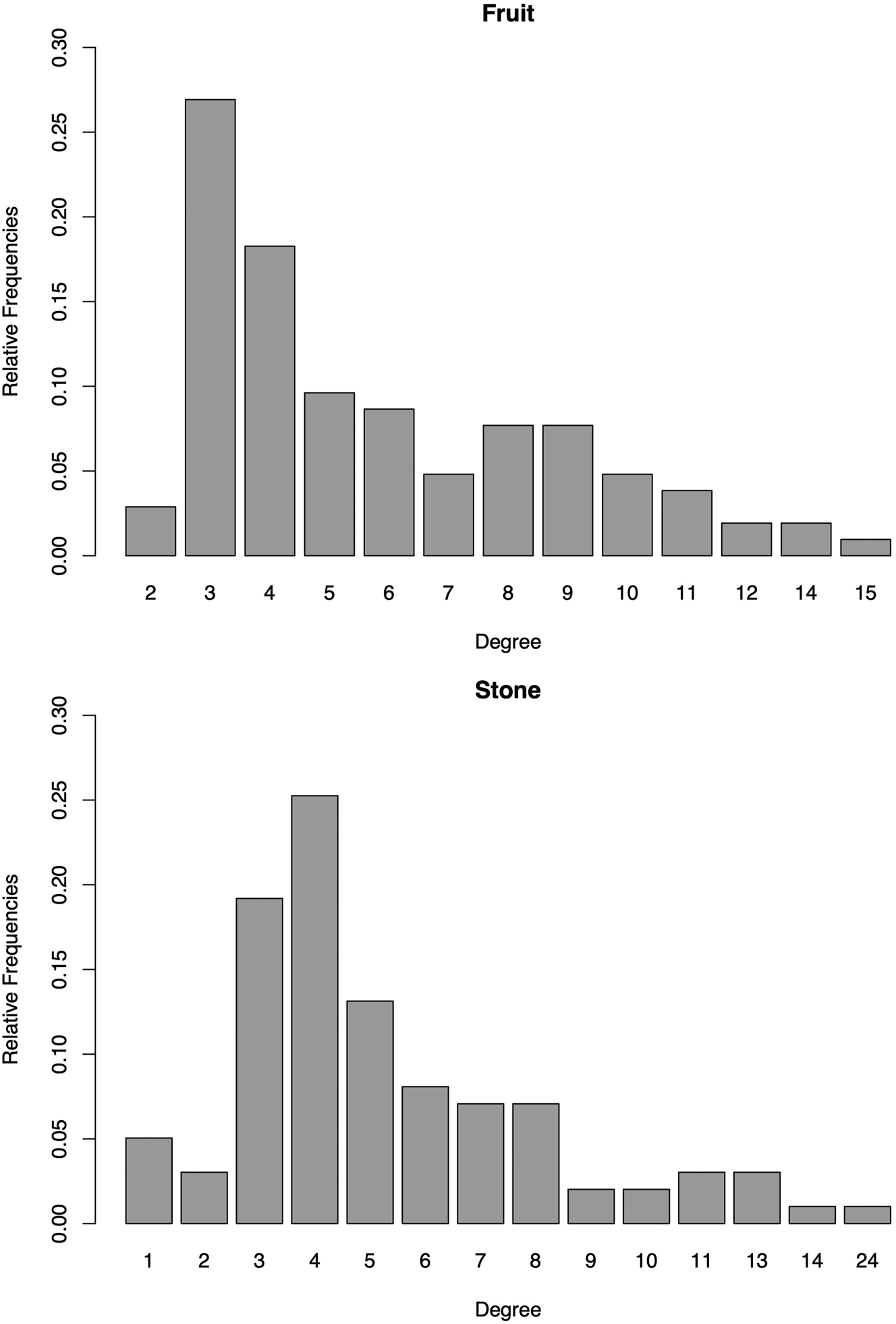

Table 11 presents the network measures for the colexification networks for ‘fruit’ and ‘stone’. Results of the one-sample z-tests between the CC and ASPL of the colexification networks and their corresponding random networks demonstrated that the two colexification networks were significantly different from the simulated random networks (p’s < 0.001), suggesting that the two networks were structurally meaningful and not simply the result of chance. In addition, the two networks exhibited small-world properties (i.e., CC ≫ CCrandom and ASPL ≥ ASPLrandom), which was further supported by the degree distribution, as shown in Figure 2, where a few nodes have a very high number of connections, while most nodes have only a few connections.

Parameters of the ‘fruit’ and ‘stone’ colexification networks.

| Fruit | Stone | |

|---|---|---|

| Nodes | 104 | 99 |

| Edges | 301 | 267 |

| Average degree | 5.79 | 5.39 |

| CC | 0.46 | 0.43 |

| ASPL | 4.31 | 3.77 |

| CCrandom | 0.06*** | 0.05*** |

| ASPLrandom | 2.81*** | 2.88*** |

-

***p < 0.001.

Relative Frequencies of Node Degrees in the ‘Fruit’ (top panel) and ‘Stone’ (bottom panel) Networks. The bar charts show the distribution of node degrees in the two colexification networks, where the x-axis (i.e. degree) represents the number of connections a node has, while the y-axis indicates the relative frequency of each degree. The skewed distribution, with a majority of nodes having few connections and a few nodes having many, is typical of small-world networks.

3.2.1 ‘Fruit’

104 concepts are identified colexified with ‘fruit’ in 58 TB languages. Table 12 presents the 10 concepts of the highest degree.

In the colexification network of ‘fruit’ (i.e. the top panel of Figure 1), ‘pear’ (d = 15) is the highest ranked concept in degree, indicating that its colexified concepts outnumber any other concepts in the network.[11] ‘Walnut’ (d = 14), ‘peach’ (d = 12), ‘pumpkin’ and ‘cucumber’ (d = 10) are additional central concepts for varieties of fruits. Small round body parts form another class of central concepts in the network of ‘fruit’. The concepts ‘ankle’ (d = 12), ‘fingernail’ and ‘bladder’ (d = 10) all exhibit relatively high degree. The two 3D-classifiers exhibit high degree as well, suggesting that this type of classifiers are colexified with many concepts in the sample.

Ranks of concepts in the network of ‘fruit’ in terms of degree.

| Concept | Degree | Cluster |

|---|---|---|

| pear | 15 | 3 |

| CL:rocks,stones | 14 | 4 |

| walnut | 14 | 3 |

| ankle | 12 | 1 |

| peach | 12 | 3 |

| CL: eggs | 11 | 4 |

| fig (tree) | 11 | 5 |

| firewood | 11 | 2 |

| grind (flour) | 11 | 6 |

| bladder; fingernail | 10 | 1 |

| cucumber | 10 | 5 |

| pumpkin | 10 | 3 |

| sugarcane | 10 | 2 |

Overall, the semantic network of 'fruit' in Figure 1 is comprised by six distinct sub-networks of semantics. It represents a “small-world” network and the cluster membership is strongly associated with the semantic category of a particular concept (χ2 = 122.36, df = NA,[12] p < 0.001,Cramer’s V = 0.49). Concept nodes within each sub-network are frequently colexified, while concepts from distinct clusters are rarely colexified and the semantic relationships across sub-networks are weak. The concept ‘fruit’ is most frequently colexified with concepts in Cluster 3 but is more difficult to be colexified with a concept from other sub-networks. Because 3D-classifiers and ‘fruit’ are distributed in distinct clusters, it suggests that the derivation of a 3D-classifier from ‘fruit’ must through some intermediate semantic classes.

Based on the degree of all concepts in the network, Cluster 3 and 1 are the central clusters in the entire network of ‘fruit’ which contain the highest ranked concepts.

Cluster 3 is in the center of the network. Concepts for varieties of fruits predominantly occupy the central area of the entire network, including ‘pear’, ‘walnut’, ‘peach’, ‘pumpkin’, indicating this semantic class serves as the basic meaning. A few concepts for objects with the small round shape, including small inanimate objects (i.e. ‘bullet’, ‘hail’), seeds (i.e. seed), body part (i.e. fist), are closely connected with the concepts for fruits, exhibiting highly identical colexification patterns.

Cluster 1 features the prominent status of body parts and is adjacent to Cluster 3. Three concepts for small round body parts, i.e. ‘ankle’, ‘fingernail’, ‘bladder’, have high degrees. Body parts are not only colexified with many concepts in this sub-network but also have strong links with important concepts in Cluster 3 in the center (i.e. both ‘ankle’ and ‘fingernail’ have multiple links with varieties of fruits in Cluster 3).

Concepts in Cluster 4 form another major cluster in the network of ‘fruit’. Two 3D-classifiers, i.e. ‘CL:rocks, stones’ (d = 14) and ‘CL:eggs’ (d = 11) have the highest degree, suggesting they have most links with other concepts of this sub-network. However, ‘CL:rocks, stones’ and ‘CL:eggs’ are merely local center of this sub-network. The entire sub-network centered around these two classifiers is somewhat split from the center and consists of less important concepts in the overall network.

The remaining three clusters (Cluster 2, 5, 6) form relatively independent sub-networks of the concepts related to ‘fruit’ that are not quite related to the semantic classes in Cluster 1 and 3.

3.2.2 ‘Stone’

99 concepts are colexified with the lexeme ‘stone’ in 68 Tibeto-Burman languages. The degree values in Table 13 reflect the significance of a concept in the network.

Ranks of concepts in the network of ‘stone’ in terms of degree.

| Concept | Degree | Cluster |

|---|---|---|

| flint (to make fire) | 24 | 8 |

| fling/toss | 14 | 1 |

| coal | 13 | 4 |

| pillow | 13 | 1 |

| pit/stone/rock | 13 | 4 |

| ant | 11 | 3 |

| cloth | 11 | 7 |

| steel | 11 | 2 |

| CL:grain (of rice) | 10 | 6 |

| key | 10 | 2 |

| cliff | 9 | 7 |

| sand | 9 | 8 |

In the colexification network of the lexeme ‘stone’ (i.e. the bottom panel of Figure 1), the concept of the highest degree is ‘flint (to make fire)’ (d = 24) in the center of the network, indicating its colexified concepts outnumber any other concepts. Other core concepts in this network include concepts for varieties of stones (i.e. ‘pit/stone/rock’, ‘coal’, ‘cliff’), 3D-classifiers (i.e. ‘CL: grain (of rice)’), small (in)animate objects (i.e. ‘ant’, ‘pillow’, ‘cloth’, ‘key’, ‘sand’), and actions (i.e. ‘fling/toss’).

Eight clusters of concepts can be distinguished. The overall network exhibits the properties of a “small-world” structure. Concepts within the cluster (a “small-world”) are well-connected while each cluster is well distinguished from one another. The cluster membership and the semantic category of a concept are moderately associated (χ2 = 99.43, df = NA, p = 0.01, Cramer’s V = 0.38). Like ‘fruit’, the concept for ‘stone’ and 3D-classifiers are found in distinct clusters, implying the presence of intermediate semantic classes in the semantic extension from ‘stone’ to a 3D-classifier. However, the clustering of concepts from the same semantic class is not as strong as that of ‘fruit’.

The center of the ‘stone’ network (Cluster 8) is a fairly small cluster built around ‘flint’ (d = 24). Next to it is Cluster 4, which is dominated by two concepts for stones and rocks, i.e. ‘pit/stone/rock’ (d = 13) and ‘coal’ (d = 11). Varieties of stones are distributed in at least 4 clusters as the center of the sub-networks. In addition to Cluster 8 and 4, ‘cliff’, ‘flight’ are both central concepts in Cluster 7 (d = 9) and Cluster 3 (d = 8), respectively. In each of these clusters, the ‘stone’-related compounds are colexified with concepts of a variety of semantic classes. No strong colexification pattern within each concept cluster of ‘stone’ can be identified.

3D-classifiers are found in two clusters: Cluster 6 and Cluster 2. Cluster 6 exhibits a strong colexification pattern involving ‘CL:grain (of rice)’, ‘CL: eggs’, ‘CL:stones’. Those 3D-classifiers are not significantly colexified with concepts from other clusters but rather form an independent ‘3D-classifier’ cluster that are most often colexified with objects of the round shape (e.g. ‘rice’). Cluster 2 is more isolated, in which ‘CL:bowls’ is colexified with body parts (e.g. ‘finger’) and small round objects (e.g. hoetool).

Provided the separation of sub-networks between ‘stone’ (and ‘stone’-related compounds) and 3D-classifiers, we still found several direct links between ‘stone’-related compounds and 3D-classifiers. For example, ‘flint’ is directly colexified with all three 3D classifiers in Cluster 6; ‘flight’ is directly colexified with ‘CL:grain (of rice)’. However, given the fact that they pertain to distinct clusters, those colexification links seem to be restricted to a limited number of languages.

3.3 Network stability

The results from Levene’s tests indicated significant differences in the variances for both the CC and ASPL between the ‘stone’ and ‘fruit’ networks. For CC, the test yielded an F-value of 420.48 (p < 0.001), suggesting a significant higher variability of clustering in the ‘stone’ network (SD = 0.03) compared to the ‘fruit’ network (SD = 0.01). Similarly, for ASPL, the test resulted in an F-value of 6.91 (p < 0.05), reinforcing the conclusion of higher variability in the ‘stone’ network (SD = 0.46) than in the ‘fruit’ network (SD = 0.40).

Further, Welch’s t-tests were performed to compare the mean differences of the CC and ASPL between the networks. The t-test for ASPL showed a mean of 4.18 for the ‘stone’ network and 4.66 for the ‘fruit’ network, with a t-value of -24.66, indicating a statistically significant difference in the ASPL between the two networks (p < 0.001). For the CC, the mean values were 0.46 (‘stone’) and 0.48 (‘fruit’), with a t-value of -19.77, also signifying a significant structural difference in terms of clustering (p < 0.001).

These findings suggest notable differences in the stability of network construction between the ‘stone’ and ‘fruit’ networks, with the latter being significantly more stable. The significant variations in both the CC and ASPL imply that the two networks are structurally dissimilar, with the ‘stone’ network exhibiting a shorter average path length and lower clustering coefficient compared to the ‘fruit’ network.

4 Semantic extension from nouns to 3D-classifiers

According to the results of concept network analysis from §3.2 and §3.3, ‘fruit’ exhibits a salient and stable path associated with the semantic evolution of ‘fruit’, while the semantic extension of ‘stone’ is unstable and language-specific. In this section, we will turn to specific paths of semantic extension from nouns to 3D-classifiers in each concept network. A closer examination on the language-specific data shows how ‘fruit’ and ‘stone’ diverge in the mode of semantic extension towards a classifier.

4.1 Semantic extension from ‘fruit’ to 3D-classifiers

The 58 sampled languages can be divided into two classes: languages have a 3D-classifier and languages do not develop a 3D-classifier. Table 14 presents the 9 languages in our sample that employ a 3D-classifier derived from ‘fruit’, most of them are from the Ngwi subgroup.

TB languages that derive ‘CLF: 3D’ from ‘fruit’.

| subgroup | language | ‘fruit’ | 3D-CLF (e.g. fruits, eggs, stones, grains of rice) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Southern Ngwi | Hani_Lüchun | a 55 si 31 | si 31 (eggs; stones) |

| Hani_Mojiang | ɔ 31 ɕi 31 | ɕi 31 (eggs; grains of rice) | |

| Central Ngwi | Jinuo | a 44 sɯ 44 | sɯ 44 (grains of rice) |

| Lahu_Lancang | i 35 ɕi 11 | ɕi 11 (eggs; stones; grains of rice) | |

| Yi_Sani | sz̩ 11 mɒ 33 | sz̩ 11 (grains of rice) | |

| Lisu | si 35 sɯ 31 | sɯ 31 (grains of rice) | |

| Northern Ngwi | Yi_Nanhua | sæ 21 | sæ 21 (grains of rice) |

| Western Tani | Tani_Bokar | a pɯ | pɯ rɯ (bowls) |

| Naxi | Naxi | dzɚ 21 ly 33 | ly 33 (grains of rice; eggs; bowls) |

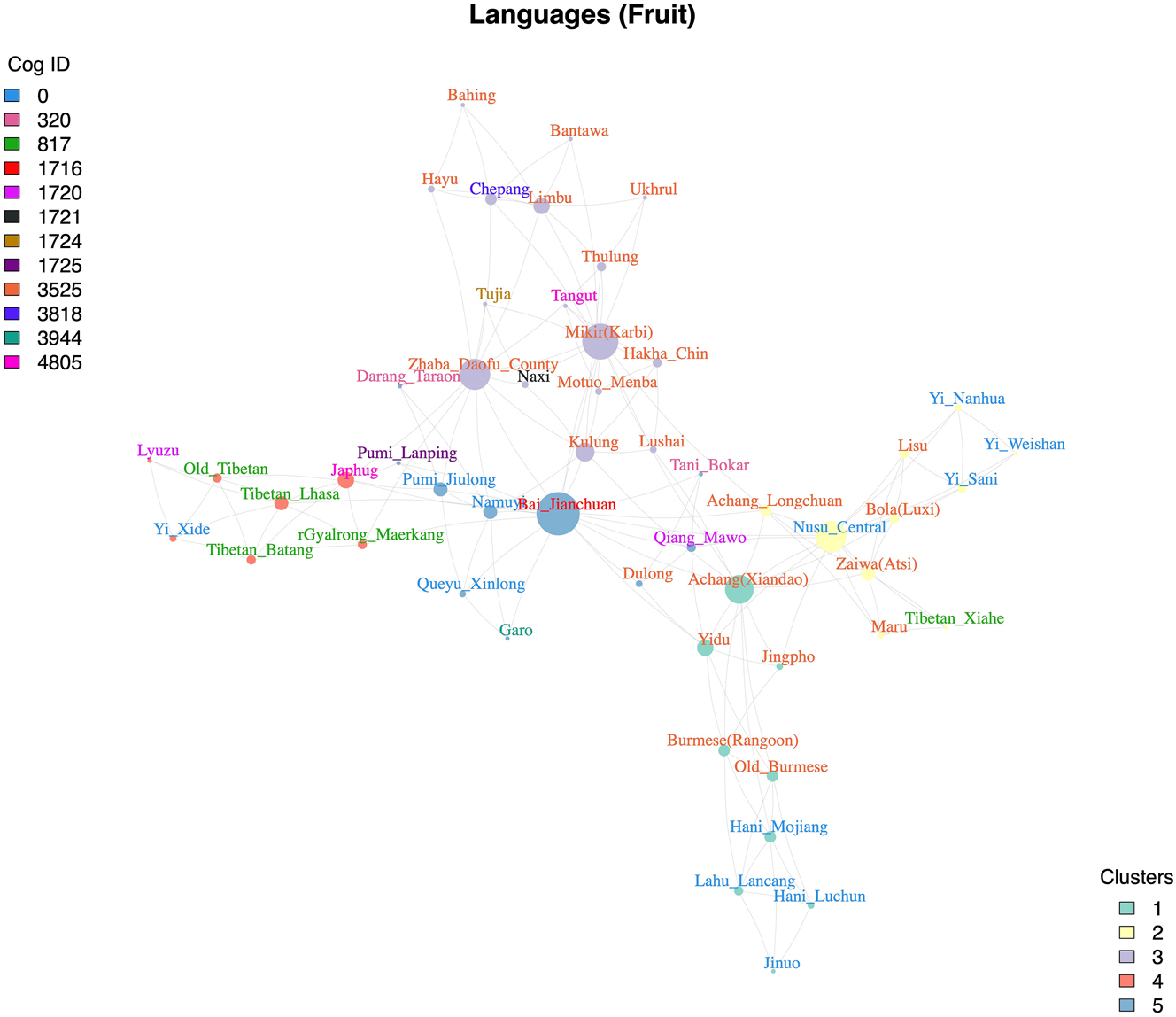

The language clusters[13] in Figure 3 on the basis of the similarity of colexification networks across the sampled languages reveal that the colexification pattern of ‘fruit’ is strongly associated with the subgroup of a particular language (χ2 = 131.85, df = NA,p < 0.001, Cramer’s V = 0.80). It clearly shows the clustering of two groups of Ngwi languages (i.e. Cluster 1 and 2), indicating Ngwi languages are identical in their colexification networks of ‘fruit’. 7 out of the 9 languages employing at least one 3D-classifier are from these two clusters of Ngwi.[14] There is a split between Northern (Yi) and Southern (Hani) Ngwi, and Central Ngwi (i.e. Lahu_Lancang, Jinuo, Yi_Sani, Lisu) in between. We speculate there exists some hidden layers to account for the split that is not relevant to the derivation of 3D-classifiers.

Language Networks of ‘Fruit’. In this figure, distinct text colors correspond to different subgroups for languages. Node colors designate various clusters, showcasing how languages group together based on shared colexification patterns for ‘fruit’. The size of each node represents the degree of the language, with larger nodes indicating languages that have a higher degree of colexification with other languages in the network.

The most salient pattern that colexifies ‘fruit’ and 3D-classifiers in the network analysis (§3.2.1), as characterized in (1), is the shared pattern of Ngwi languages in our sample. Due to the strong colexification of ‘fruit’, compounds for fruits, and small round body parts (i.e. Cluster 3 (varieties of fruits) and Cluster 1 (small round body parts) are the two central concept clusters in the network of ‘fruit’), semantic extension from ‘fruit’ to 3D-classifiers is most likely through the mediation of compounds for varieties of fruits and small body parts.

| the first colexification pattern of ‘fruit’ and 3D-CLF (Ngwi type) |

| ‘fruit’ – CT in compound nouns for varieties of fruit – CT in compound nouns for small round body parts – Shape-based classifier (3D-CLF) |

Diachronically, (1) indicates that the noun ‘fruit’ does not directly derive classifiers. For both languages with and without a classifier, ‘fruit’ usually first developed into a CT in compounds marking varieties of fruits. However, not all languages that involve the CT ‘fruit’ in the fruit compounds have developed a classifier. The CT ‘fruit’ tends to be present in compounds denoting small round body parts from Cluster 1 before developing the use as a classifier.

Table 15 presents four types of languages in our sample that exhibit variation in (1), resulting in the presence/absence of a 3D-classifier.[15]

Languages that colexify ‘fruit’ with varieties of fruits, small round body parts, and 3D-classifiers.

| Type | Language | Subgroup | ‘Fruit’ | Varieties of fruits | Body parts | 3D-CLF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | Jinuo | Central Ngwi | a 44 sɯ 44 | sɯ44 jɛ44 a44 sɯ44 ‘peach’; ŋa42 sɯ44 ‘banana’ |

la55 sɯ44 ‘claw / talon’ (1)a | + |

| Lahu_Langcang | Central Ngwi | i 35 ɕi 11 | ɑ35 vɛ53 ɕi11 ‘peach’; mɑ35 li31 ɕi11 ‘pear’; mɑ35 mɑ31 ku33 ɕi11 ‘walnut’ |

khu33 mɛ54 ɕi11 ‘ankle’ (1); ni11 ɕi11 u33 ‘testicle’ (1); ɔ31 lɑ53 ɕi11 ‘kidney’ (4) |

+ | |

| Yi_Nanhua | Northern Ngwi | sæ 21 | sæ21 ɣɯ21 ‘peach’; sæ21 ‘pear’; sæ21 mi33 ‘walnut’ |

tɕhi33 me̱33 sæ21 ‘ankle’ (1); sɛ21 ‘liver’ (1); də33 xu33 sæ21 ‘testicle’ (1) |

+ | |

| Yi_Sani | Central Ngwi | sz̩ 11 mɒ 33 | z̊33 m̩11 sz̩11 mɒ33 ‘grape’; sz̩11 ɣɯ11 mɒ33 ‘peach’; sz̩11 tʂhʐ̩33 mɒ33 ‘pear’ |

sz̩11 phɒ33 mɒ33 ‘bladder’ (1); sz̩11 ‘liver’ (1) |

+ | |

| Yi_Weishan | Northern Ngwi | sɿ̄ 33 sᴇ 21 ʔlo 33 sᴇ 21 | sᴇ21 ʔy21 ‘peach’; sᴇ21 tʂhɿ55 ‘pear’ |

dᴇ33 sᴇ21 ‘testicle’ (1); di55 sᴇ21 ‘kidney’ (4) |

− | |

| II | Dulong | Nungic | ɕiŋ 55 ɕi 55 | ɹɯŋ31 ɕi53 ‘grape’ | tɯ31 ɕi55 ‘gall/bladder’ (1/4) | − |

| Jingpho | Jingpho | nam 31 si 31 | să33 ŋum33 si31; sum33 wum33 si31 ‘peach’; să55 pjiʔ55 si31 ‘grape’ |

pa̱u33 si31 ‘uvula’ (4) |

− | |

| Bantawa | Kiranti | si;si wa | TaTnamsi ‘grape’ | chuk ku si/chuk-si-ma ‘finger’ (4) | − | |

| Bola_Luxi | Burmish | ʃɿ 35 | pu55 ʃɿ35 ‘walnut’; pui55 ka55 ʃɿ35 ‘persimmon’ | − | − | |

| Burmese (Rangoon) | Burmish | ɑ 53 tθi 55 | tθɑ53 bjiʔ4 tθi55 ‘grape’; mɛʔ4 mũ22 tθi55 ‘peach’; tθiʔ4 tɔ22 tθi55 ‘pear’ |

− | − | |

| Chepang | Kham-Magar-Chepang | sayʔ | ʔay.sayʔ ‘cucumber’ |

dut.sayʔ/ ʔoh.sayʔ ‘nipple’ (6) | − | |

| III | Hani_Mojiang | Southern Ngwi | ɔ 31 ɕi 31 | ɕi31 mu31 ‘peach’; ɕi31 pa31 ‘grape’; ɕi31 phɛ55 ‘pear’ |

− | + |

| Hani_Lüchun | Southern Ngwi | a 55 si 31 | si31 bja̱31 ‘grape’; si31 ɣɔ31 ‘peach’; |

ɣø31 si31 ‘kidney’ (4) la33 si31 ‘mouth’ | + | |

| Lisu | Central Ngwi | si 35 sɯ 31 | tɕhe̱31 le̱31 sɯ31 ‘grape’; sɯ31 lɯ̱33 bɯ33;sɯ31 lɯ33 bɯ44 ‘persimmon’ |

− | + | |

| IV | Tani_Bokar | Western Tani | a pɯ | − | a pɯ ‘gall’ (4) | + |

| Naxi | Naxi | dzɚ 21 ly 33 | − | lɑ21 ly33 ‘finger’ (4); by33 ly33;mby33 ly33 ‘kidney ’(4) |

+ |

-

aNumber in the parenthesis indicates the concept cluster.

The type I languages follow the path in (1) and are primarily from the Ngwi subgroup. Four Ngwi languages that colexify ‘fruit’ with the Cluster 3 fruit compounds as well as the Cluster 1 body part compounds also possess a 3D-classifier. The only exception is Yi_Weishan, which satisfies both conditions in (1) but does not contain a colexified 3D-classifier.

The type II languages colexify ‘fruit’ with the fruit compounds in Cluster 3 but not the body parts from Cluster 1. As expected, they do not develop a 3D-classifier. Languages outside the Ngwi subgroup may colexify ‘fruit’ with fruit compounds but do not contain a classifier. This is probably due to that the ‘fruit’ morpheme is not colexified with body part terms, as demonstrated by Bola_Luxi and Burmese_Rangoon, or the colexified body part term is from clusters other than Cluster 1 (i.e. Cluster 4 or Cluster 6), as in as Dulong, Jingpho, Bantawa, and Chepang.

The type III languages colexify ‘fruit’, fruit compounds and 3D-classifiers but do not colexify ‘fruit’ with body parts from Cluster 1. Those languages involve Lisu, Hani_Mojiang, and Hani_Lüchun. However, taking a closer look at those Ngwi languages, they should not be excluded from the Type I languages. We found an array of Cluster 1 body part compounds that are colexified with ‘fruit’ in different sources.[16] Therefore, the path in (1) still holds for the majority of Ngwi languages.

The type IV languages do not colexify ‘fruit’ with fruit compounds in Cluster 3 nor body parts from Cluster 1 but have developed a 3D-classifier. Naxi and Tani_Bokar in our sample exhibit this pattern.

There are of course other minor paths that derive a 3D-classifier in addition to (1). In Type IV languages, classifiers in Cluster 4 are not derived from ‘fruit’-related concepts but seem to be directly derived from body parts. For example, Naxi has the classifier ly 33 classifying objects like grains, eggs, and bowls. However, ly 33 does not colexify with any compound meaning ‘fruit’ but rather with body parts like ‘finger’ and ‘kidney’. Tani_Bokar uses the classifier pɯ rɯ to classify bowls, which is originally derived from *pɯ ‘egg’ in Proto-Tani (Sun 1993). Like Naxi, it is not found colexified with varieties of fruits but rather is found in ‘gall’.

Based on the above discussion, the presence of a numeral classifier in the colexification network of ‘fruit’ is largely due to that the language is from the Ngwi subgroup. Both Type I and Type III Ngwi languages derive a 3D-classifier via the path in (1). The concept ‘fruit’ may derive the meaning of classifier as a result of shared innovation of Ngwi languages. This is congruent with Bradley (1979), in which the proto *si 2 is reconstructed for both ‘fruit’ and the classifier ‘CLF: fruit’ in Proto-Ngwi.

4.2 Semantic extension from ‘stone’ to 3D-classifiers

The 68 sampled languages can be divided into two groups depending on the presence/absence of a 3D-classifier. Table 16 presents the 7 languages in our sample that employ a 3D-classifier derived from ‘stone’. In contrast to ‘fruit’, which is highly biased to Ngwi languages, languages deriving a 3D classifier from ‘stone’ are distributed over 6 subgroups. The subgroup (χ2 = 108.36, df = NA, p = 0.04) of a particular language is marginally associated with the colexification pattern of ‘stone’.

TB languages that derive ‘3D-CLF’ from ‘stone’.

| Subgroup | Language | ‘Stone’ | 3D-CLF (e.g. stone, egg, bowl) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nungic | Dulong | luŋ 55 | luŋ 55 (classify stones, eggs, grains of rice) |

| Nung | ḷuŋ 55 | (thi 31 ) ḷuŋ 55 (classify stones and eggs) | |

| rGyalrongic | Daofu | rgə ma | (a) rgə (classify bowls) |

| Bodo-Garo | Garo | roŋ | roŋ- (classify round objects)a |

| Tibetan | Written Tibetan | rdo | rdog (gtɕig) (classify grains of rice) |

| Bai | Bai_Jianchuan | tso̱ 21 khue 55 ; tso 42 khui 55 | (ke 55 sẽ̱ 21 ɑ 21 ) khue 55 (classify eggs); kʰou 33 (classify grains of rice)b |

| Karenic | Karen | lø 31 | phlø 31 (classify stones, eggs, grains of rice) |

-

aThe specific nouns that can be classified by the 3D-classifier roŋ-in Garo is not explicit. However, based on descriptions in Burling (2003) and Wood (2008), it is provisionally assumed that all types of round/globular objects, including grain of rice, egg, stone/rocks, and bowls are classified by roŋ-in Garo. bIn Huang (1992), the entry for the classifier for grain of rice is recorded as (me44ɑ21)o44. While in other sources, this classifier is recorded as kho 33 (Sun 1991) or kʰou 33 in Jianchuan Bai (Allen 2007), and reconstructed as *qʰɔ 2 in Proto-Bai (Wang 2012). None of the Bai dialects in Wang (2012) has the o 44 form and only one dialect in Allen (2007) (i.e. Qiliqiao Bai) has the form of ɔ 33 . In this paper, we adopt the form kʰou 33 in Jianchuan Bai from Allen (2007) for the classifier ‘CLF:grain of rice’.

According to Figure 1, no salient path from ‘stone’ to 3D-classifiers can be identified in the concept network of ‘stone’, since the sub-networks of classifiers are diverse and somewhat isolated from the stone-related compounds. Compounding involving ‘stone’ as an intermediate stage in the derivation of classifier is not as productive as (1) in TB languages.

Figure 4 shows that at least two groups of languages (i.e. Cluster 1: Garo, Dulong, Karen, Bai_Jianchuan, Nung, Daofu; Cluster 4: Tibetan_Written) that exhibit distinct colexification patterns of ‘stone’ have independently developed 3D-classifiers. Further splits can be made within Cluster 1 once scrutinizing this cluster. It is due to the high variability of the network of ‘stone’, indicating that the path deriving a 3D-classifier from ‘stone’ is very unstable (§3.3). It follows that TB languages exhibit dissimilar colexification networks of ‘stone’, which are ineffective in predicting the presence of classifiers in a particular language. Below we will take a closer look at the 7 languages that possess a 3D-classifier and demonstrate the inability to associate the colexification pattern of ‘stone’ with a 3D-classifier.

Language Networks of ‘Stone’

Table 17 displays the 7 languages that colexify ‘stone’ and 3D-classifiers. ‘Stone’/ ‘stone’-related compounds and 3D-classifier exhibit relatively direct links and shorter path in derivation as the colexified ‘stone’ compounds are confined to a small number of concepts (most prominently ‘flint’). Nung, Dulong, Jianchuan_Bai, Karen, and Written Tibetan all colexify ‘stone’ with compounds for varieties of stones, while the root ‘stone’ is not found in ‘stone’-related compounds in Garo and Daofu. The path ‘Noun – CT in compound nouns – 3D-classifier’ holds for most of those languages. Nevertheless, the concept network result in §3.2.2 shows that ‘stone’ concepts of the same semantic class are not strongly colexified. Notably concepts pertaining to the semantic class of ‘small round objects’ in Table 17 are quite diverse across languages and hence no intermediate stage concerning compounds for ‘small round object’ should be posited between ‘stone’-related compounds and 3D-classifiers. It implies that the overall colexification pattern of ‘stone’ is not strongly related to the presence of a 3D-classifier, as the classifier is more directly derived from ‘stone’ and a limited number of ‘stone’-related compounds.

Languages that colexify ‘stone’ with varieties of stones, small round objects, and 3D-classifiers.

| Language | Language cluster | ‘Stone/rock’ | Varieties of stones | Small round objects | 3D-CLF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nung | 1 | luŋ 55 | xo31 bi31 luŋ55 ‘flint’ (8) | thi31 vɛn31 luŋ55 ‘hail’ (8) luŋ55 ‘bark’ (6) ȵi55 luŋ55 ‘eye’ (6) |

(thi31) ḷuŋ55 ‘CL:eggs’ (6) (thi31) ḷuŋ55 ‘CL:stones’ (6) |

| Dulong | 1 | luŋ 55 | tɕɑ31 mɑʔ55 luŋ55 ‘flint’ (8) luŋ55 pɑŋ55 ‘cave’ (6) |

ɑŋ31 luŋ55 kɑn55 ‘radish’ (6) ɑm55 luŋ55 ‘rice’ (6) nam31 luŋ55 ‘sun’ (6) |

luŋ55 ‘CL:grain’ (6) |

| Bai_Jianchuan | 1 | tso̱ 21 khue 55 | pa̱21 tsa55 tso̱21 ‘flint’ (8) |

mi55 tso̱21 ‘ladle’(2) tso̱33 ŋue33 khue55‘steel’ (2) tso̱21 kə55 ‘key’ (2) |

(ke 55 sẽ̱ 21 ɑ 21 ) khue 55 ‘CL:eggs’ (6) kʰou 33 ‘CL:grains of rice’(6) |

| Karen | 1 | lø 31 | lø31 me̱31 ‘flint’ (8) lø31 tθui31 la̱55 ‘coal’ (4) lø31 bi̱31 ba̱31 ‘flight’ (3) |

me33 khua55 phlø31 ‘bowl’ (5) dă31 lø31 tha55 ‘trivet’ (7) |

phlø31 ‘CL:stones’(6) phlø31 ‘CL:eggs’ (6) |

| Written Tibetan | 4 | rdo | rdo sol ‘coal’ (4) rdo skas ‘flight’ (3) me rdo ‘flint’ (8) rdo.? ‘pebble’ (7) |

rdo lo ‘pestle’ (4) rgja rdo ‘weight’ (1) ɦbru rdog ‘rice’ (6) |

rdog (gtɕig) ‘CL:grain’ (6) |

| Garo | 1 | roŋ | − | − | roŋ- ‘CL:eggs’ (6) roŋ- ‘CL:grain’ (6) roŋ- ‘CL:stone’ (6) roŋ- ‘CL:bowl’ (2) |

| Daofu | 1 | rgə ma | − | lo ma ‘finger’ (2) ma phjo ‘ladle’ (2) bji ma ‘sand’ (8) ɬtɕɑ mar ‘steel’ (2) |

(a) rgə ‘CL:bowls’ (2) |

Combining the network instability (§3.3), the language clustering in Figure 4, and the language-specific data in Table 17, 3D-classifiers seem to be derived from ‘stone’ independently in individual languages and cannot be uniformly accounted for by semantics.

5 Discussion

In this discussion, we attempt to address the two research questions in the beginning of the article on the basis of the findings drawn from the concept networks: 1) Is there any salient path of semantic extension associated with the derivation of classifiers for 3-dimensional objects from ‘fruit’ and ‘stone’? 2) How effective the colexification patterns can predict the presence/absence of a classifier in a particular language? Regarding the first question, the path of “Noun – Class term (CT) in compound nouns - Shape-based classifier” has been identified as a common pattern in the semantic extension towards a 3D-classifier in Tibeto-Burman, in which generic-specific compound nouns play a critical role (§5.1). With respect to the second question, only the colexification pattern of ‘fruit’ but not ‘stone’ can effectively predict the presence/absence of a 3D-classifier (§5.2). An implicational universal is proposed based on that. The important role played by body part concepts in noun categorization is briefly reviewed in §5.3.

5.1 Generic-specific compound nouns in the semantic extension towards 3D-classifiers

There is a strong tendency of grammaticalization of numeral classifiers from nouns in Tibeto-Burman and worldwide (Aikhenvald 2000; Corbett 1991; Evans 2022; Huang 2022; Post 2022; Grinevald 2000, 2002; Seifart 2010). Results from the colexification networks of concepts in this study (§3.2) point to that compound nouns serve as a critical semantic class in this process. Among the TB languages that have developed 3D-classifiers classifying small round objects such as ‘egg’, ‘grain of rice’ and ‘stones, rocks’, 3D-classifiers are indirectly colexified with the nouns for ‘fruit’ and ‘stone’ because 3D-classifiers and ‘fruit’/ ‘stone’ are distributed in distinct clusters in both networks. The centrality and high degrees of compound nouns containing the morpheme ‘fruit’/ ‘stone’ in both concept networks strongly indicate that compounds are colexified with more concepts than 3D-classifiers. It follows that compounding is an intermediate stage in the derivation of 3D-classifiers from nouns in Tibeto-Burman langauges. This finding can be empirically supported by crosslinguistic data.

Classifier systems typically emerge in two distinct contexts (Little et al. 2022): the context of counting individual items which are of particular cultural importance (Bisang 1999:158), such as Chinese and Japanese; the context of taxonomic or meronomic compounding process, which is prominent in Tai, Hmong-Mien, and Tibeto-Burman languages (Bisang 1999; DeLancey 1986; Enfield 2004; Vittrant and Allassonnière-Tang 2021). ‘Class noun’ (or class term) as a part of the noun root is conceived as an important stage in the process of deriving a “classifier-for-noun” (Little et al. 2022). (2) through (4) illustrate distinct types of classified nouns in Mandarin Chinese, Hmong, and nDrapa.

| Classical Chinese (Sinitic) |

| 竹竿万个。(《史记·货殖列传》) (汉) | ||

| zhúgān | wàn | gè |

| bamboo_rod | ten_thousand | CLF:general |

| ‘Ten thousand bamboo rods’ (Shiji-huozhi liezhuan, Han Dynesty) (Zhang 2012: 310) | ||

| Hmong (Mon-Khmer) | |

| ib-tug | tub-sab |

| one-CLF:ANIM | CN:PERSON-thief |

| ‘A thief’ (White 2019:231) | |

| nDrapa (Tibeto-Burman) | |

| láɕheʂtsʊji | tɛ-jî |

| apprentice | one-CLF:GEN |

| ‘An apprentice’ (Huang 2022: 231) | |

The general classifier gè in Classical Chinese was not evolved from any generic terms in compounds but initially used as a general classifier, whose occurrences as a numeral classifier can be dated back to as early as Han Dynasty (Zhang 2012). In Hmong, by contrast, there are class terms like ntoo ‘tree’, txiv ‘fruit’, tub ‘son’, etc. (Bisang 1999: 167), which serve as generic nouns specifying a superordinate level concept. They are the lexical origin of numeral classifiers, as in (3). The small set of numeral classifiers in the Tibeto-Burman language nDrapa are also grammaticalized from compound nouns that hold a generic-specific relationship between the classifying morpheme and the host noun. The ji coda of the noun ‘apprentice’ in (4) means ‘man/human’ and serves as a class term specifying the superordinate class of láɕheʂtsʊ ‘pupil’. It further developed into a general classifier jî (Huang 2022: 231).

Findings of the present quantitative study support the claim that compound nouns play a critical role in the grammaticalization of TB classifiers. We propose the path in (5) to characterize the semantic extension of 3D-classifiers from the nouns for ‘fruit’ and ‘stone’, in which the lexeme ‘fruit’ or ‘stone’ serve as a class term (CT) in compound nouns before turning into a pure classifier. The CT and the other part of the compound hold a generic-specific semantic relationship.

| Path of semantic extensions of ‘fruit’ and ‘stone’ |

| Noun – CT in compound nouns - Shape-based classifier |

This grammaticalization cline is not only widespread in TB languages that have rich classifiers, such as Ngwi-Burmish and Tani languages (Bradley 2012; Post 2022), but also common in languages with limited number of classifiers, as in nDrapa (Qiangic, see Shirai 2022; Huang 2022).

‘Fruit’ first developed into a bound morpheme (CT) in compounds for varieties of fruits, such as ‘pear’, ‘peach’ and ‘walnut’. The CT ‘fruit’ was extended to compounds of the same shape as fruits and finally became a shaped-based classifier. As illustrated by Figure 1, ‘CLF: eggs’, ‘CLF: stones, rocks’, ‘CLF: bowls’ and ‘CLF: grain (of rice)’ all have direct links with compound nouns for types of fruits or small round objects, but none of them are directly colexified with the noun ‘fruit’. Taking Lisu (Central Ngwi) as an example. Table 18 presents words colexified with the lexeme ‘fruit’, including the classifier ‘CLF: grain (of rice)’ (Sun 1991;Huang 1992). sɯ 31 initially appeared in the disyllabic generic noun for ‘fruit’ (Stage 1); it then developed as a class term in compound nouns for types of fruits (Stage 2); in Stage 3, sɯ 31 occurred in compounds for grains, seeds, body parts, and other round-shaped objects; it finally became a sortal classifier for grains (Stage 4).

Colexified concepts of ‘fruit’ in Lisu.

| Word form | Gloss |

|---|---|

| Stage 1: | |

| si 35 sɯ 31 | ‘fruit’ |

| Stage 2: | |

| tɕhe̱ 31 le̱ 31 sɯ 31 | ‘grape’ |

| sɯ 31 lɯ 33 bɯ 44 | ‘persimmon’ |

| Stage 3: | |

| tɕhɯ̱ 33 sɯ 31 | ‘rice’ |

| dze̱ 31 sɯ 31 | ‘seed’ |

| miɛ 44 sɯ 31 | ‘Eye’ |

| tsɯ 55 sɯ 31 | ‘charcoal’ |

| Stage 4: | |

| sɯ 31 | ‘CLF: grain (of rice)’ |

In the case of ‘stone’, as shown in Figure 1, it is not directly linked with the classifiers ‘CLF: stones, rocks’, ‘CLF: grain (of rice)’, and ‘CLF: eggs’ but rather derived those classifiers via compound nouns for varieties of stones and other round things. The compounds for ‘flint (to make fire)’, ‘flight (of steps)’, and ‘coal’ are most important nouns that derived classifiers in an array of languages (§4.2.2). The morpheme ‘stone’ appears as a class term in those compounds before turning into a classifier. Table 19 presents the colexified concepts of ‘stone’ in Dulong (Nungic, Huang 1992). The noun root luŋ 55 ‘stone’ (Stage 1) first appears in the compounds for different types of stones and rocks (Stage 2), holding a specific-generic relationship between the basic and the superordinate level concept; luŋ 55 then developed into a class term accompanying inanimate round objects that are small in size (Stage 3). Finally, it became a 3D-classifier (Stage 4).

Colexified concepts of ‘stone’ in Dulong.

| Word form | Gloss |

|---|---|

| Stage 1: | |

| luŋ 55 | ‘stone’ |

| Stage 2: | |

| lɯ 31 ka 55 luŋ 55 paŋ 55 | ‘cave’ |

| tɕɑ 31 mɑʔ 55 luŋ 55 | ‘flint (to make fire)’ |

| Stage 3: | |

| nɯ 31 lɛŋ 31 luŋ 55 | ‘egg/testicle’ |

| ɑŋ 31 luŋ 55 kɑn 55 | ‘radish’ |

| ɑm 55 luŋ 55 | ‘rice’ |

| nam 31 luŋ 55 | ‘sun’ |

| Stage 4: | |

| luŋ 55 | ‘CLF:stones,rocks’ |

| luŋ 55 | ‘CLF:eggs’ |

| luŋ 55 | ‘CLF:grain (of rice)’ |

Shape is considered the most important semantic parameter in noun categorization, including numeral classifiers (Adams and Conklin 1973; Aikhenvald 2000; Senft 1996). The semantic colexification pattern of ‘fruit’ and ‘stone’ of the sampled Tibeto-Burman languages demonstrates a crosslinguistic tendency that before this parameter comes into play, the “shape” lexeme is a taxonomical classifying morpheme that classifies nouns according to their superordinate level category.

5.2 The effectiveness of colexification patterns in predicting 3D-classifiers

‘Fruit’ and ‘stone’ diverge in the mode of deriving 3D-classifiers from compounds. The significant difference in their network structure and stability (§3) and the language-specific data (§4) strongly suggest that only ‘fruit’ but not ‘stone’ exhibits a stable and salient path in semantic extension from nouns to 3D-classifiers. Only the colexification pattern of ‘fruit’ but not ‘stone’ can effectively predict the presence/absence of a 3D-classifier.

The most salient path of semantic extension from ‘fruit’ to 3D-classifiers in Tibeto-Burman experiences the 4 stages characterized in (1) in §4.1 (i.e. repeated below), as illustrated by the Lisu example in Table 18.

| the first colexification pattern of ‘fruit’ and 3D-CLF (Ngwi type) |

| ‘fruit’ – CT in compound nouns for varieties of fruit – CT in compound nouns for small round body parts – Shape-based classifier (3D-CLF) |

(1) is a path attested in most Ngwi languages in our sample. Ngwi languages that developed 3D-classifiers from ‘fruit’ tend to colexify ‘fruit’ with the body part compounds ‘testicle’, ‘fingernail’, ‘ankle’, ‘claw’, ‘bladder’, ‘liver’, and ‘throat’ (Cluster 1) in Stage 3. A 3D-classifier is commonly absent in languages in which ‘fruit’ does not colexify with those body part concepts (i.e. Type II languages in Table 15). An implicational universal can be formulated to predict the presence/absence of a 3D-classifier based on their distributions in TB (i.e. Table 15):

(6) If a TB language colexifies ‘fruit’ with the ‘fruit’ CT in fruit compounds from Cluster 3 and the shape morpheme in body part concepts from Cluster 1, the language tends to have a 3D-classifier.[17]

The four types of languages investigated in Table 15 (§4.1) empirically support the prediction in (6). The path in (1) turns out to be fairly in Tibeto-Burman that accounts for half of the languages that possess a 3D-classifier and is highly skewed toward Ngwi.

‘Stone’, to the contrary, does not exhibit any crosslinguistic salient path of semantic extension like ‘fruit’. The high variability of the network of ‘stone’(§3.3) and the weak colexification patterns of the ‘stone’-related concepts (§3.2.2), together with the language clustering in Figure 4 and the language-specific data in Table 17 (§4.2), all indicate that the path deriving a 3D-classifier from ‘stone’ is very unstable. The shorter average path length and the direct links between individual ‘stone’ concepts (e.g. ‘flint’) and 3D-classifiers in the network of ‘stone’ (§3.3) suggest that the semantic extension ‘stone’ – ‘stone’related compounds- 3D-classifiers is incidental. Such extension is not semantically motivated as ‘fruit’ but rather the result of semantic extension of invidual nouns.

Indeed, the evolutionary situations from ‘stone’ to classifier are incidental and language-specific. Among the 7 languages that develop a 3D-classfier from ‘stone’, only Garo (Bodo-Garo) and Karen (Karenic) have reconstructed classifiers in the proto languages. In Karen (Karenic), lø 31 ‘stone’ is colexified with the classifier phlø 31 , which classifies stones, eggs, and grain of rice (Huang 1992). This classifier has already existed in the Proto-Karen (i.e. *phloŋ B ‘CLF: stones/rocks’), which was colexified with the proto form for stones (i.e. *loŋ B ‘stone/rock’) (Luangthongkum 2013). In other languages, the colexification of ‘stone’ and classifier is absent in the their corresponding proto languages. Classifiers are a part of Proto-Bodo-Garo (Wood 2008), Proto-Tani (Post and Sun 2017), and Proto-Ngwi (Bradley 1979). But none of the classifier roots in those proto languages are related to ‘stone’. Some languages have experienced replacement of the 3D -classifier in history, resulting in the colexification of ‘stone’ and 3D-classifier in modern languages. Proto-Boro-Garo (PBG) has a handful of numeral classifiers (Wood 2008), among which the PBG classifier of round objects has the same proto form as the lexeme of ‘fruit’ (i.e. *thái)[18] but later in some languages this classifier was replaced by the lexeme of ‘stone’ (*roŋ-). This is what has been observed in Garo (Wood 2008:75).

Given the above facts, we may conclude that though ‘fruit’ and ‘stone’ both derive classifiers via an intermediate stage of compound nouns, their colexification networks strongly imply two distinct modes of deriving classifiers from nouns. The colexification network of ‘fruit’ but not that of ‘stone’ can effectively predict the occurrence of a 3D-classifier in a particular language, which is highly correlated with the subgroup of the language.

5.3 Body part concepts in noun categorization

The essesntial status of body part compounds in the derivation of 3D-CLF in TB highlights the importance of body part concepts in noun categorization. The close relationship between body parts and the small round shape has been characterized in many noun categorization systems. For example, the gender assignment in New Guinea (Aikhenvald 2012) is associated with the shape of the body part (i.e. round or long). In Nilo-Saharan languages, body parts typically categorize nouns in terms of their shape (Blench 2015). Body parts appear to be a common lexical source for shape-based numeral classifier in Asian classifier languages (Aikenvald 2000; Bisang 1996) as well as noun classes/gender in other parts of the world, as in Bahnar (Adams 1989), Kana (Ikoro 1996), and Gumuz (Blench 2015) in Africa, and Palikur in Amazon (Aikhenvald and Green 1998). Findings of this paper suggest that body part compounds serve as a critical stage in the development of 3D-classifiers in Tibeto-Burman languages. However, it is noteworthy that only a specific subset of body part concepts, including ‘testicle’, ‘fingernail’, ‘ankle’, ‘claw’, ‘bladder’, ‘liver’, and ‘throat’(Cluster 1), are relevant to the derivation of a 3D-classifier. There is another small set of body part concepts, such as ‘eye’, ‘heart’, and ‘naval’, in Cluster 6 that do not play a role in the derivation of 3D-classifiers. Colexification with those body parts is not a sufficient condition of the presence of a classifier.

6 Conclusions

In this study, we adopt a network-based approach to explore the semantic evolution of 3D-classifiers from ‘fruit’ and ‘stone’ in 58 + 68 Tibeto-Burman languages by examining their semantic colexification networks and evaluating the effectiveness of the colexification patterns of the two nouns in predicting the presence/absence of a classifier in a particular language.

Findings of the present study confirm that ‘fruit’ and ‘stone’ are frequent sources of the 3D-classifiers in Tibeto-Burman. The colexification networks of ‘fruit’ and ‘stone’ support the claim that compound nouns play a critical role in the grammaticalization of TB classifiers (Aikhenvald 2022; Bisang 1999; DeLancey 1986; Vittrant and Allassonnière-Tang 2021). We postulate that numeral classifiers for small round objects in a substantial number of TB languages were originated from the noun roots such as ‘fruit’ and ‘stone’. They were then developed into class terms in compound nouns denoting varieties of fruits/stones and the shape class of small round objects. Finally, those noun roots lost their concrete meanings and derived into shape-based classifiers. The recurrent cline of semantic change ‘fruit > round > generic’ (Aikhenvald 2000) is attested in Tibeto-Burman languages, in which shape serves as a critical semantic basis in the semantic evolution of a classifier.

Nevertheless, ‘fruit’ and ‘stone’ differs significantly in their specific mode of semantic extension in Tibeto-Burman. The colexification pattern of ‘fruit’ but not that of ‘stone’ can effectively predict the occurrence of a 3D-classifier in a particular language, as the latter is more unstable. An implicational universal is proposed to predict the occurrence of a ‘fruit’-related classifier in Tibeto-Burman. The colexification network of ‘fruit’ represents a well-established cross-linguistic pattern that derives 3D-classifiers following the path ‘fruit-compounds for fruits-compounds for round body parts-3D-CLF’. This pattern is strongly associated with the subgroup of languages and is most prominent in Ngwi. To the contrary, the colexification network of ‘stone’ is somehow language-specific. No salient cross-linguistic semantic extension pattern can be generalized to account for the derivation of classifier from ‘stone’ in Tibeto-Burman languages.

One remaining issue that is not fully addressed in the paper is the role of language contact in the semantic evolution from nouns to 3D-classifiers. It is generally agreed that classifiers are readily to be borrowed across languages (Allassonnière-Tang et al. 2021; Greenhill et al. 2017; Her and Li 2023). Indeed, contact-induced classifier borrowings are common among TB languages. Classifiers in Bodo-Garo, Newar, Tani, and Burmic languages all developed under the influences from the classifier systems in the nearby Tai languages and Mandarin Chinese (Bradley 2012; Evans 2022; Hyslop 2008; Post 2022; Weidert 1984). From the results of network analysis, we have seen that provided the common grammaticalization path shared by both ‘fruit’ and ’stone’, the effect of language contact is evident quantitatively in the distinct modes of semantic evolution of the two nouns. The instability of the network of ‘stone’ strongly points to a contact effect that may result in language-specific borrowings of a ‘stone’-related 3D-classifier.

Funding source: National Social Science Fund of China (NSSFC)

Award Identifier / Grant number: 22BYY063

-

Research funding: This study is supported by the research grant of The National Social Science Fund of China (NSSFC) entitled “A variationist study of the endangered multilingualism in Yunnan Zauzou”「云南若柔人濒危多语状态下的语言变异研究」(Grant No. 22BYY063).

Abbreviations

- ANIM

-

animate

- CLF

-

classifier

- CN

-

class noun

- GEN

-

genitive

- PERSON

-

person