Abstract

In this corpus-informed cross-linguistic study, we focus on (1) ‘phraseology markers’ (PMs), which are recurrent and fixed word combinations used to demarcate instances of linguistic prefabrication, and (2) novelty markers (NMs), which are conventional expressions that mark novel phrasings of either new or familiar conceptualizations. Both classes of expressions have been largely neglected in phraseological studies conducted to date. Using selected corpora of general and spoken English and Polish, we study the use and discoursal functions of three pairs of loosely equivalent pre-selected phraseology markers and attempt to determine the amount of prefabricated language demarcated by those linguistic items. We found that the PMs and NMs perform opposing primary and secondary functions. By default, they are used to mark either prefabricated or supposedly novel expressions. In many contexts, however, PMs are used to break phraseology, that is, to mark expressions or phrases that represent unusual, unconventional, idiosyncratic phrasings unattested or rarely used in native texts.

1 Introduction

One of the challenges faced by many sub-disciplines of linguistics, such as phraseology, lexicography, natural language processing or machine translation, is to devise better methods of identification, extraction and recording of phraseological expressions (henceforth PEs) found in texts. Generally, the criteria used to extract instances of linguistic prefabrication from texts are varied, as they include formal-linguistic, frequency-driven or distributional and psycholinguistic ones, which also correspond with various perspectives on formulaic language (Forsyth and Grabowski 2015; Gałkowski 2006; Nelson 2018; Pęzik 2018; Schmitt and Carter 2004; Trklja and Grabowski 2021; Wray 2002, 2008; Wood 2015). Formal-linguistic criteria (or, in other words, language system-oriented ones) are grounded in linguistic theory and they include phonological, morphological, syntactic, semantic and pragmatic criteria while frequency-driven criteria, grounded in language use and distribution of linguistic items (hence, text-oriented or language use-oriented criteria), include raw and normalized frequency of use, frequency distributions, measures of lexical attraction/repulsion or collocational strength etc. In studies dealing with processing, storage and retrieval of formulaic language, researchers use a wide range of text processing metrics, e.g., reaction times, eye-tracking methods etc., which are grounded in cognitive linguistics and psychology.[1] Given the vast array of extraction criteria, Schmitt and Carter (2004: 3) argue that PEs should be treated in an inclusive way so that multiple types of linguistic units fall under a cover-all term formulaicity.

In practice, the quest for PEs involves the application of selected operationalized criteria to text fragments or to word combinations (contiguous or non-contiguous ones) that are candidates for PEs. However, it is also possible to undertake an attempt at identification of PEs using other linguistic items found in co-text or punctuation marks found in near proximity to instances of PEs, which can be treated as potential signals of prefabricated language. Such a method may be treated as a complementary one with respect to system-oriented, usage-oriented or cognitive-based criteria mentioned above. Thus, in this paper, we focus on the ways formulaic language is marked or signalled in texts.

According to Čermák (2005), Chlebda (2010), Rozumko (2011), Ruiz-Gurillo (2015), Rojo (2019), there are many orthographic and linguistic devices that can function as textual indicators of prefabricated expressions. More specifically, Chlebda (2010: 21–27) argues that textual operators signalling the use of prefabricated language in Polish can encompass punctuation marks (e.g., quotation marks introducing quotations or winged words) as well as conventionalized routine formulas, e.g., że tak powiem ‘so to speak’, by tak rzec ‘so to say’, jak to się mówi ‘as it were’, jak mawiają ‘as they say’, jak to się zwykło określać ‘as it used to be called’, jak to się przyjęło nazywać ‘as it used to be called’, tak zwany ‘so called’, przysłowiowy ‘the proverbial n’ studied by Pęzik (2018),[2] jak mawiają w ‘as they say in’, jak mawia klasyk ‘in the words of’, jak powiedział znany [ktoś] ‘as somebody famous once said’, co określano mianem ‘as it used to be called’, jak mówi mądrość ludowa ‘popular wisdom has it that’, jak głosi znane porzekadło ‘as the (well-known) adage goes’, zgodnie ze starą maksymą ‘as an old saying goes’ etc.). Likewise, Čermák (2005: 58) claims that many idioms or phrases are signalled “by certain phrases or words” that may be referred to as introducers (e.g., so to speak in English or abych tak řekl in Czech). In a similar vein, Rozumko (2011: 316–317) explores so-called proverb introducers, also called metalinguistic tags, in English (e.g., according to the proverb, as the old saying goes, they say) and Polish (e.g., jak mówi przysłowie, zgodnie z przysłowiem, zgodnie ze starym powiedzeniem), which are “words and phrases used by speakers to signal that they are going to use a proverb or that they have just used it” (ibid.), while Rojo (2019) refers to linguistic items that are used to introduce phraseological units as metatextual indicators (e.g., as the saying goes). Such expressions are typically fixed, socially conditioned and their primary textual function is to introduce or demarcate various types of PEs in speech or writing, and help identify those narration fragments that constitute the common knowledge of a sender and addressee as well as of their discourse communities (Chlebda 2010: 21). It seems, however, that we do not have exhaustive knowledge as to how such textual indicators of PEs are used in discourse, notably with respect to discoursal functions other than marking instances of formulaic language.

Hence, in this cross-linguistic corpus-informed study, we undertake an attempt at investigating recurrent phrases whose main textual function is to signal or mark the use of prefabricated idiomatic expressions (idioms, proverbs, sayings, clichés, winged words etc.), and that is why we call such items ‘phraseology markers’ (Pęzik 2018), henceforth PMs. Furthermore, we look at the same expressions used to achieve the opposite objective of marking compositional wordings. We also assume that the patterns of use of PMs may provide new insights into the variability of PEs, which are often “transformed, compressed and partly edited, in order to be marked as prefabricated” (Pęzik 2018: 214). In other words, we believe that apart from marking canonical forms of PEs, PMs may be also used to mark novel, innovative uses of PEs where syntactic and semantic properties of multi-word expressions conflict with more general usage norms. From a different perspective, such conscious or subconscious uses where the fixed, canonical form of PEs is broken, and their new variants are employed in certain contexts may be construed as phraseological errors (Bąba 1989, 2009). However, Andrejewicz (2015: 48–49), who conducted a corpus-informed study of the use of selected PEs in Polish, argues that their use in texts, which very often deviates from the canonical forms recorded in dictionaries, should not be automatically considered as erroneous but rather as an alternative way of using PEs, underscoring such features of PEs as the lack of their absolute fixedness or their elastic stability (cf. Chlebda 2003: 181). This observation also aligns with the Theory of Norms and Exploitations (TNE) put forward by Hanks (2013) whereby there is a set of rules that govern normal and conventional language use and a second-order set of rules that govern exploitation of those usage norms and conventions resulting in incremental innovation and, eventually, in language change (ibid., 411).

Since phraseology and linguistic prefabrication is also grounded in culture, that is, they are treated by many researchers as repositories of cultural or ethnolinguistic knowledge (e.g., Sandomirska 2000; Bartmiński 2002; Wierzbicka 2015 [3]), it is possible to study the use of PMs cross-linguistically. Thus, we focus on English and Polish languages, as we believe that the findings of cross-linguistic studies of PMs may be useful for foreign or second language learners in their pursuit of fluent and idiomatic language use. Furthermore, the identification of prefabricated language through PMs may also supplement other methods (formal, distributional etc.) used to extract PEs and formulas from texts. Also, the linguistic material obtained thanks to the PMs may facilitate development of more comprehensive descriptions of phraseological profiles of individual speakers or discourse communities. Finally, we believe the PMs may also come in useful as a complementary method for measuring the degree of formulaicity or phraseological prefabrication in texts.[4]

2 Phraseology markers and their functions

In the context of this study, the term ‘phraseology markers’ (PMs) can be related to broader concepts of ‘discourse markers’ (e.g., Schiffrin 1987/1996) or ‘pragmatic markers’ (e.g., Fraser 1996), which have been defined in various ways and explored from multiple perspectives (Lenk 1998; Ranger 2018). For example, Fraser (1999: 931–932) argues that discourse markers include “discourse connectives, discourse operators, pragmatic connectives, sentence connectives, and cue phrases”, a large heterogeneous functional class of linguistic items responsible for the flow of discourse (in terms of coherence, cohesion etc.). In other words, discourse markers are “linguistic expressions of varying length which carry pragmatic and/or propositional meaning, occur in both speech and writing, and facilitate rather than disrupt discourse” (Siepmann 2005: 43). Some researchers investigate discourse markers (also called ‘discourse particles’ or ‘discourse-linking devices’) primarily but not exclusively in spoken language and focus on routine speech formulas performing conversational management functions (rather than contributing to propositional content of utterances), e.g., helping express speaker’s stance and shape the relationships between the speaker and listener, among others (Lenk 1998: 37; Stede and Schmitz 2000: 125). In that respect, what we call in this paper as PMs are in fact linguistic expressions that are attested primarily in spoken language and that facilitate management of conversations and dialogue flow, notably by explicitly and purposefully signalling the use of PEs.

Although phraseological competence, measured by knowledge and use of PEs, varies between language speakers, there is also cumulative shared knowledge of a given discourse community regarding how to use language in particular communicative situations. In other words, every use of a PE arises from individual experience of members of discourse communities as well as from the common knowledge base of the discourse community, an idea which is also reflected in the lexical priming theory (Hoey 2005, 2007). To put it simply, language speakers use PEs to a varying degree yet when they do so, they also appeal to the common knowledge base of their interlocutors in the hope that they also share a basic intuition about idiomaticity and prefabrication in language use. According to Pęzik (2018: 214), there are situations, however, when language speakers purposefully mark the use of prefabricated or formulaic expressions, which may be due to, for example, their lack of confidence about the conventionality of a PE,[5] a peculiar stylistic use of language or a specific pragmatic effect (an appeal to conventional wisdom, irony, humour, emphasis, recollection from memory, filling a pause during a conversation etc.). The linguistic items which are recalled from collective memory of language users and whose function is to explicitly mark the use of PEs (encapsulating the whole variety of prefabricated phrases, routine formulas, proverbs, sayings, clichés etc.) in speech or writing are referred to in this paper as PMs.

Those PMs which happen to be multiword units can be positioned within many typologies of phraseological items developed in Polish, Russian or British research tradition. For example, PMs can be assigned to a peculiar subclass of speech formulas called commentaries (Baranov and Dobrovolskij 2008), which are used to comment on various aspects of communicative situations, e.g., дай бог памяти ‘God give (me) memory’ (Polish: jeśli mnie pamięć nie myli/zawodzi, English: if my memory serves me well/right/correctly). Furthermore, a custom-designed class of such items may be found within a broad concept of ‘reproducts’ (Chlebda 2010), where the textual operators signalling the use of prefabricated expressions are called phraseological indicators ‘wskaźniki frazeologii’ (p. 21). As such, PMs can be also considered as a peculiar subcategory of pragmatemes or routine formulas, which comprise “conventional expressions used in recurrent situations” primarily in spoken language (Szerszunowicz 2020: 173), and which “tend to be neglected in phraseological analyses” (ibid.). According to Mel’cuk and Milicevic (2020: 112), pragmatemes are in fact clichés with fixed meaning and fixed form, which are restricted in terms of their use by a speech act situation (e.g., Hold the line, please; Sincerely yours). As for PMs, their form is also fixed (e.g., so to speak, as it were), yet their use is not restricted to a particular extralinguistic situation (e.g., answering a telephone call). On the contrary, PMs may be used at any point during a conversation and their pragmatic meanings may also vary from context to context, e.g., appealing to conventional wisdom, signalling irony, softening a message, emphasizing metaphorical language use in a particular communicative situation.

The motivation behind exploring PMs in greater detail is manifold. Apart from providing insights into language users’ intuitions regarding the use of prefabricated expressions, the exploration of PMs may help us understand the ways prefabricated language is marked in texts. For example, we may attempt to determine whether and to what extent quotations or winged words are typically accompanied by PMs. We may also endeavour to find out whether there are any other types of PEs (idioms, routine formulas, sayings etc.) signalled by individual PMs. Is it the case that PMs are only used to mark formulaic and prefabricated expressions, or do they perform any other textual functions? These are only a few problems that remain largely underexplored with respect to the use and discoursal functions of PMs.

3 Methodology

Broadly speaking, we adopt a corpus-based perspective in this study focusing on the exploration of the use of PMs. More precisely, we preselect a set of textual operators described as PMs in specialised literature (Čermák 2005; Chlebda 2010; Rojo 2019; Rozumko 2011; Ruiz-Gurillo 2015; Pęzik 2018) and, by consulting large language corpora of English and Polish, we attempt to, first, describe frequency distributions and pervasiveness of PMs in texts, and second, to verify what types of PEs (fixed expressions, idioms, proverbs, sayings, quotations, winged words etc.) are introduced in texts by the PMs under scrutiny. It is hoped that the present study will enable us to identify and describe patterns or tendencies of PMs’ use as labels foregrounding various types of PEs across modalities (spoken and written). Particularly, we will focus on spoken language as we believe that PMs are found in transcripts of conversations in a broader spectrum of functions than in written texts. This is simply because spoken language use happens in real time and it is therefore subject to temporal constraints, unlike the production of most genres of written texts, which can be ‘edited out’ as redundant. Similarly, Rojo (2019) argues that knowledge of how metatextual indicators (i.e. PMs) are employed to signal PEs may be of utmost importance when immediacy is a crucial factor, which is the case of interpreting or conversational language use (or spoken language in general). In what follows, we describe in greater detail the units of analysis, research material (study corpora), research questions and hypotheses as well as the tools and study stages.

3.1 Units of analysis

As mentioned earlier, PMs are typically fixed, socially conditioned and their major discoursal function is to facilitate the management of conversation flow by explicit and purposeful signalling the use of prefabricated phrases and formulas in speech or writing. Due to space constraints, we selected 1 group of formally, semantically and pragmatically similar PMs found in Polish and English, which will be explored in terms of their frequency distributions and patterns of use, with particular emphasis on their specific discoursal functions and the ways they introduce or demarcate prefabricated phrasings in texts.

by tak rzec, że się tak wyrażę, że tak powiem (Pol.),

so to speak, so to say, as it were (Eng.)

The above items[6] represent a set of loosely equivalent PMs, which – as we intuitively believe – are used in speech and writing mainly to signal emphasis or humour, to explicitly mark that a speaker or writer recollects something from memory, to fill a pause during a conversation etc. However, it can be hypothesised that their more fine-grained discourse functions may vary across contexts of use, text types, genres and modalities (spoken and written), let alone across different languages, which may also have implications for the types of PEs that they introduce or demarcate in texts.

3.2 Research material

As the units of analysis come from texts written in two languages, we use large general-language corpora of contemporary Polish and English for a quantitative and qualitative study. As for the Polish language, we use the balanced multi-genre component of the National Corpus of Polish (NKJP), which includes 240,192,461 words found in texts published predominantly in the years 1989–2011 (Przepiórkowski et al. 2012). Importantly, around 10 % of the texts in the NKJP represent spoken or to-be-spoken texts, including parliamentary debates held in the Polish parliament; more precisely, the spoken sub-corpus of the NKJP, which is called Other Conversational Data (Inne dane mówione, henceforth NKJP Spoken), contains 27.2 million words (Pęzik 2012: 39). We also use Spokes, a conversational corpus of Polish with 2.3 million words representing transcriptions of spontaneous conversations (Pęzik 2015). Also, for further verification of the use of certain expressions in general-Polish, we additionally consult a larger 7.7-billion-word Polish Web 2012 corpus, called plTenTen12 (Jakubíček et al. 2013), which has been made available via the SketchEngine platform (Kilgarriff et al. 2014) and the 8-billion-word MoncoPL corpus as the most up-to-date monitor corpus of Polish covering the period of 2010–2023 and updated on a daily basis (Pęzik 2020).

As for the English corpora, we use the first edition of the British National Corpus (BNC), with 96 million words (BNC Consortium 2007), the Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA) with more than 450 million words (Davies 2008), the British National Corpus Spoken demographic component, with 10,495,185 words, a newer BNC Spoken 2014 (Love et al. 2017), with over 10 million words of audio-recordings of face-to-face conversations collected between 2014 and 2016, as well as a larger opportunistic English Web corpus 2015, called enTenTen15 (Jakubíček et al. 2013), with more than 13.2 billion words (the latter two are made available via SketchEngine).

3.3 Research hypotheses, research questions and study stages

This primarily descriptive study is based on certain assumptions. First, we believe that many PMs constitute a universal textual device whose function is mirrored in many languages. That is why we expect that they will perform similar discursive functions, e.g., signalling similar types of PEs, across texts written in two languages under scrutiny, that is, English and Polish. In other words, it is reasonable to assume that the PMs’ discursive functions and discourse practices facilitated by those textual operators will be relatively commonplace across cultures that are fairly comparable, as it is the case in this study. Second, we assume that PMs are more typical of spoken genres and registers rather than written ones, where it is often not necessary to explicitly signal or foreground the use of PEs. Third, we assume that since PMs may signal various types of prefabricated expressions, we will identify instances of language use showing high variety and high degree of internal variability of the PEs or formulas explicitly marked by PMs under scrutiny.

In view of the above, this paper aims to provide answers to the following research questions:

How frequent are the PMs under scrutiny in general and spoken language?

What types of phraseological/prefabricated expressions do PMs mark? Do they perform any other discoursal functions?

Are there any cross-linguistic similarities or differences in terms of the use and discoursal functions of the PMs under scrutiny in English and Polish?

How much prefabricated language is marked by PMs?

In order to provide answers to the research questions, this study will be conducted – using both quantitative and qualitative methods of data analysis – in the following stages. First, we will use the reference corpora of English and Polish to verify frequency distributions of the PMs under scrutiny, also across spoken and written modalities in both languages. More precisely, we will pay particular attention to the PMs patterns of use in spoken language as we believe that the investigated items are more typical of speech than writing. Second, we will conduct a qualitative analysis of concordances in order to determine discoursal functions of the PMs and to study the ways in which they mark prefabricated language in texts. Then, we will compare English and Polish data in order to identify any similarities and differences with respect to obtained results. Furthermore, we will undertake an attempt at estimating the amount of prefabricated language marked by the PMs. Finally, we will discuss the findings and consider their implications for other subfields of linguistics, such as bilingual lexicography, computer-assisted translation or language teaching.

4 Results

In this section, we will present the results of quantitative and qualitative analysis of the PMs under scrutiny, followed by a case study related to the use of the English PM ‘so to speak’.

4.1 Phraseology markers in contrast

The PMs under scrutiny can be characterized as parenthetic expressions, are typically used to indicate that a speaker intends to say something in an unusual or even surprising way yet still adequate in referring to what the speaker wants to say (cf. Great Dictionary of Polish, henceforth WSJP, entry: by tak rzec). Other Polish phrases, marked in WSJP as quasi-synonyms, that perform a similar pragmatic function include że się tak wyrażę and że tak powiem (cf. WSJP: ‘a speaker indicates that an expression that is not completely adequate to what is being said in a particular situation represents a peculiar way to express a particular content’). Hence, the definitions underscore that those PMs perform pragmatic functions of phraseology breakers or novelty markers, among others.

A semantically and pragmatically similar English phrase (so to speak) has similar definitions in English dictionaries, e.g., ‘used to highlight the fact that one is describing something in an unusual or metaphorical way (also so to say)’ (Oxford English Dictionary, henceforth OED), ‘used to explain that what you are saying is not to be understood exactly as stated’ (Cambridge Dictionary, henceforth CaD), ‘used to indicate that one is using words in an unusual or figurative way rather than a literal way’ (Merriam-Webster Dictionary, henceforth Mer-Web). In English, the same pragmatic function is also performed by the following phrases: so to say (marked as an equivalent phrase to so to speak in the aforementioned dictionaries), as it were (CaD: ‘sometimes said after a figurative (= not meaning exactly what it appears to mean) or unusual expression’; OED: ‘In a way (used to be less precise)’).

4.1.1 Quantitative analysis of frequency distributions across language corpora

As mentioned earlier, in our study we focus on the following PMs: by tak rzec, że się tak wyrażę, że tak powiem (Polish); so to speak, so to say, as it were (English). Our selection is based on the assumption that these phrases are either formally or semantically (based on the aforementioned dictionary definitions) similar and they represent a promising point for a preliminary study like this one. The frequency distributions of the PMs in the selected study corpora are presented below.

by tak rzec (NKJP: 288: NKJP Spoken: 0; Spokes: 0; plTenTen12: 2,595; MoncoPL: 1078)

że się tak wyrażę (NKJP: 147: NKJP Spoken: 1; Spokes: 6; plTenTen12: 4,383, MoncoPL: 415)

że tak powiem (NKJP: 2811: NKJP Spoken: 206; Spokes: 415; plTenTen12: 32,374, MoncoPL: 7671)

so to speak (BNC: 353, BNC Spoken: 39; BNC Spoken 2014: 32; enTenTen12: 34,574)

so to say (BNC: 19, BNC Spoken: 4; BNC Spoken 2014: 3; enTenTen12: 3,959)

as it were (BNC: 1009; BNC Spoken: 426; BNC Spoken 2014: 77; enTenTen12: 28,050)

From among the investigated Polish phrases, the most frequently used one is że tak powiem, that is, in general (NKJP, plTenTen12, MoncoPL) and spoken language (NKJP Spoken, Spokes). The analysis of normalized frequency distributions across text types in the National Corpus Polish (NKJP) confirms our hypothesis that this phrase is indeed more typical of spoken language, both conversational (116 occurrences pmw) and quasi-spoken (87 occurrences pmw).

As for the English phrases, two of them (so to speak, as it were) are considerably more frequently used than the phrase so to say, in both general (BNC, enTenTen12) and spoken language (BNC Spoken, BNC Spoken 2014). Also, a cursory inspection of normalized frequencies (per 1,000 sentences) revealed that the phrase as it were is more typical of spoken language (0.41 vs 0.11) while so to speak is more frequent in written texts (0.03 vs. 0.06), at least in the BNC. Interestingly, both phrases are relatively infrequent in the newer edition of BNC Spoken 2014, where so to speak occurs 32 times (2.7 pmw) and as it were 77 times (6.5 pmw).

4.1.2 Qualitative analysis of the PMs’ pragmatic functions

Next, we conducted a qualitative analysis of the occurrences of two most frequent PMs (że tak powiem, so to speak) in the Polish and English corpora in order to verify what discoursal functions they perform and, in addition, to verify to what extent they signal phraseological prefabrication in spoken texts. The analysis focuses on spoken corpora as we assume that the examined phrases are more typical of spoken language. Also, a relatively smaller size of spoken corpora, as compared with national corpora of general language, is more conducive to manual qualitative analysis.

The Polish phraseme że tak powiem performs multiple discoursal functions across different contexts of use in NKJP Spoken corpus (206 occurrences) and Spokes (415 occurrences). In particular, it tends to be used in its dictionary meaning, i.e. to signal that what a speaker says is in fact an unusual expression to use in a given situation, e.g., instead of a typical expression toczyć się swoim/utartym torem ‘to take/run its (normal) course’, a peculiar phrasing to run its good course is used (Example 1). In other words, the data[7] show that the PM że tak powiem tends to be used in Polish as a marker of phraseological variation, breaking conventional phraseology by modifying canonical forms of phraseologisms, and hence performing the function of a ‘phraseology breaker’ (Examples 1–3):

| wszystko się toczyło dobrym torem że tak powiem gdyby nie to że się zaplątał do do takiej organizacji tajnej (PELCRA_7203010000374) |

| (“everything run its good course, so to say, if it wasn’t for the fact that he had got entangled in a secret organization”) |

| życie mnie że tak powiem ustawiło tak że straciłem ładnych parę zakoli włosów (id=JK8L8&text_id=g0Eg) |

| (“life got me, so to say, so that I lost a good number of receding hairlines”) |

| takie ekstra z zewnątrz jak się idzie to takie to okno że tak powiem razi swoją nowością i czystością. (PELCRA_7203010000472) |

| (“it looks special from the outside, as you walk past then such a window, so to speak, dazzles you with novelty and cleanliness”) |

Furthermore, we identified a large number of examples (Examples 4–7) where the phrase że tak powiem is also used to mark prefabricated, conventional expressions, be it proverbs, sayings or habitual collocations, and in such contexts, it performs the function of a ‘phraseology marker’, e.g.,:

| I tutaj trzeba by się mocno i głęboko zastanowić może by się dało upiec że tak powiem dwie pieczenie na jednym ogniu że tu by się wzięło kredyt na mieszkanie (PELCRA_7203010000052) |

| (“and here it is necessary to think carefully and deeply so that maybe it would be possible to kill, so to say, two birds with one stone, so that here a mortgage would be taken out”) |

| oprócz ludzi takich czujących blusa że tak powiem są po prostu takie dewoty też nie? (PELCRA_7203010000410) |

| (“apart from people who got the blues, so to say, there are also such bigots, aren’t they?”) |

| a jak gdzieś jedziesz to właśnie zwiedzasz czy raczej leżysz że tak powiem do góry brzuchem (id=xG9rrR&text_id=luz_zg) |

| (“and when you go somewhere, do you visit places or rather, so to say, laze around”) |

| czyli ii yy że tak powiem jedziemy na jednym wózku (id=Rp6yxE&text_id=luz_8e) |

| (“so uh-huh, so to say, we are in the same boat”) |

There are also examples, however, when the phrase under scrutiny is used to break formulaicity in that it marks an unusual word combination, that is, unattested in dictionaries and/or language corpora or considered to be idiosyncratic according to native speaker’s linguistic intuition. We refer to such pragmatic function as a ‘novelty marker’. In other words, we identified several spoken text fragments with the phrase że tak powiem, where formulaic language is used in atypical ways, e.g., when its fixed form is broken, and new variants of prefabricated expressions (with novel and innovative internal variation) are used to convey speakers’ intended meanings. In the analysed material, the fixed or conventional form of formulaic language is broken with a specific purpose in mind, e.g., to allude to something, to emphasize that what is being said is not completely adequate in a situation etc. In Example 8, instead of a typical phrase być niespełna rozumu ‘to be out of sb’s mind/to have a screw loose’, the phrase że tak powiem is used to emphasize its unusual variant, namely być niespełna sił psychicznych ‘to be out of psychological strength’, e.g.,

| wiesz Binia mama jest niespełna że tak powiem sił fizycznych i psychicznych do tego żeby zajmować się dzieckiem (PELCRA_7203010000487) |

| (“you know Binia, mother is, so to say, out of her physical and psychological strength necessary to take care of a baby”) |

Likewise (Example 9), instead of a typical word combination towarzystwo wzajemnej adoracji ‘a mutual admiration society’, a peculiar word combination kółko adoracyjne ‘a circle of admiration’ (unattested in NKJP) is used, e.g.,:

| to mówiła mi że on w ogóle wiesz. ma takie kółko. że tak powiem adoracyjne w którym jest tam parę osób (PELCRA_7203010000169) |

| (“she told me that in general he has a circle, so to say, of admiration, with a few people in it”) |

Next, we studied the use of the English phrase so to speak in the BNC Spoken (39 occurrences) and BNC Spoken 2014 (32 occurrences) in order to verify if its patterns of use and discoursal functions are similar to the corresponding Polish phrase. First, many of its occurrences (Examples 10–14) are used to highlight that a speaker is describing something in an unusual (idiosyncratic) or metaphorical way, hence we can call them ‘novelty markers’, often used to show that what the speaker says is not to be understood exactly as stated, which corresponds with the dictionary definitions found in OED and CaD, e.g.,:

| Sorry, this is pretty mind-blowing, but he has got himself into difficulties because he things that beauty is not, so to speak , a logical construction that allows us to talk about particular objects in the world. (Ideas in Action programmes: radio broadcast) |

| yeah he’s just the boss in charge and he yeah had these cars at his command so to speak yeah and yes well he worked oh I suppose now he’s gone back again (Utterance ID: 1621 in BNC Spoken 2014) |

| cos it’s only cottages up there and they they looked at this house as the big house so to speak (Utterance ID: 1252 in BNC Spoken 2014) |

| it would be at least and not just killing people but when the shit goes down so to speak once you know the the fire’s on or you would have thought (Utterance ID: 46 in BNC Spoken 2014) |

| she had a few patients who were erm trapped in their own bodies so to speak so they were completely paralysed (Utterance ID: 153 in BNC Spoken 2014). |

Furthermore, we identified contexts (Examples 15–20), where the phrase so to speak was used to signal prefabricated expressions (phraseology marker), including habitual collocations, idioms and conventional sayings, e.g.,

| I think first part to it, but then er it seemed to go downhill so to speak (Tutorial lesson) |

| So er they ’ve put me out to grass so to speak (Talk on fire prevention) |

| so rather than just prop up the status quo, which is what is would be very easy to do if one just kept the pot boiling so to speak by giving a few grants to artists here (South East Arts Face the Media course: lecture.) |

| I should point out that in one of the features of adhesions is that it takes two to tango, so to speak ! (Newcastle University: lecture on microbiology) |

| go back in because there was a big queue I thought well just have to grin and bear it so to speak so it’s some issue (Utterance ID: 1365, BNC Spoken 2014) |

| a sort of important job but not the he’s not the secretary of edu but not really in in the thick of it so to speak (Utterance ID: 202 in BNC Spoken 2014) |

We also found an instance of language use (Example 21) in the full version of the BNC corpus, where the phrase so to speak was creatively employed (as a ‘phraseology breaker’) in the context of golf game, namely to introduce a peculiar variation of an idiom of Biblical origin, namely rise from the dead (CaD): ‘to be successful or popular again after a period of not being successful or popular’), e.g.,

| Harley is news here, although it’s mainly because of his caddie’s death. But he was risen from the golfing dead,[8] so to speak , and my friend is interested in what an agent can achieve for minor stars, as well as superstars. (BNCdoc.id: CS4) |

A closer inspection of a larger enTenTen15 corpus revealed that there are more variants of this particular idiom adopted to specific contexts of use, e.g., risen from the near dead, risen from the freaking dead, and risen from the political dead, notably in political discourse. Although none of them was marked by the phrase so to speak, the above example (risen from the golfing dead) shows that the PMs have potential to mark such unusual variants of prefabricated expressions.

The findings presented above show that the analysed PMs used in Polish and English texts perform various textual functions, ranging from marking to breaking formulaic language, with a goal to emphasize that a given expression is indeed metaphorical or unusual when referring to something in the course of a spoken communicative situation. As for marking formulaic language, it still remains unclear to what extent the PMs mark prefabricated language, and that is why in the following section we undertake an attempt at estimating whether the PMs can be used as a complementary method of identification of formulaic language.

4.2 Phraseology markers in use: the case of English so to speak

At this stage, we are interested in measuring the PMs potential as a complementary method used to detect traces of prefabricated language in texts. More precisely, we aim to verify how much prefabricated language is marked by a particular PM as compared with its total frequency of use in a corpus. As a case in point, we will focus on a single PM, namely the English phrase so to speak as used in the spoken component of the British National Corpus (BNC) as well as in a more up-to-date COCA 2020 corpus of contemporary American English. In total, the entire COCA 2020 corpus includes 1 billion words and contains texts written up to the year 2020; its spoken component includes 127,396,932 words found in 44,803 texts, which are primarily unscripted conversations from American TV and radio programmes broadcast on NPR, PBS, ABC etc.[9] More precisely, we will attempt to assess how many instances of prefabricated language (idioms, proverbs, sayings, routine formulas recorded in English dictionaries, such as the OED, CaD and Mer-Web[10]) are marked by the phrase so to speak in a sample of total occurrences in both corpora. Importantly, the use of BNC and COCA 2020 – both containing a balanced spoken sub-corpus – will enable us to compare the PMs’ patterns of use across two varieties of English (British English vs. American English).

First, we inspected the BNC Spoken corpus, where the phrase so to speak occurs 39 times, and found that in an overwhelming majority of cases, so to speak is ‘used to highlight the fact that one is describing something in an unusual or metaphorical way’ (OED). However, we found 2 contexts (Examples 22–23) where the said PM marks the use of prefabricated expressions, namely to keep the pot boiling[11] and it takes two to tango, e.g.:

| (…) which is what is would be very easy to do if one just kept the pot boiling so to speak by giving a few grants to artists here and sitting at the centre of a spider ’s web in Tunbridge Wells (…). (id: M0RXgzss, text_BNC_id: KS4) |

| I should point out that in one of the features of adhesions is that it takes two to tango, so to speak ! (id: KnRmVnss, text_BNC_id: F8S) |

Nevertheless, a relatively small size of the corpus and low number of occurrences of the phrase therein is – as we believe – not sufficient to arrive at any estimate of formulaic language marking. That is why we additionally looked into the spoken component of COCA 2020 corpus, where the analysed phrase occurs 1,321 times, and extracted two random samples[12] with 100 occurrences for a manual qualitative analysis to identify any traces of prefabricated expressions. In the first sample of 100 random occurrences of so to speak, we found 15 examples of prefabricated idiomatic expressions recorded in dictionaries of contemporary English (OED, CaD, MWeb), namely tread the boards (OED, CaD, MWeb), push the envelope (OED, CaD, MWeb), get under someone’s skin (OED, CaD, MWeb), rally the troops (MWeb), (laugh) under someone’s breath (OED, CaD, MWeb), (to be) below the belt (OED, CaD, MWeb), through the back door (OED, MWeb), (reach) the end of the road (OED, CaD, MWeb), till the cows come home (OED, CaD), (win) the brass ring (OED, MWeb), hit the road (OED, CaD, MWeb), take something in one’s own hands (OED, CaD, MWeb), a stitch in time saves nine (OED, CaD, MWeb), take the bull by the horns (OED, CaD, MWeb), (pay) a house call (OED, CaD, MWeb). Selected examples (24–27) are presented below:

| So I had n’t really sort of, you know, trodden the boards, so to speak . (id: 236092_141, text_BNC_id: 236092) |

| Until the -- the cows come home, so to speak , that will not happen. (id: 232798_205, text_BNC_id: 232798) |

| (…) as reflected again today, is that a little bit of preventive medicine, a stitch in time, so to speak , saves nine. (id: 240498_308, text_BNC_id: 240498) |

| And they ’ve taken the bull by the horns, so to speak , and really addressed the issue (id: 240699_127, text_BNC_id: 240699) |

In order to obtain an insight into the potential of the phrase under scrutiny to mark prefabricated idiomatic expressions, we extrapolated the result in the sample to the entire population of texts, where so to speak occurs 1,321 times. To that end, we used Corpus Frequency Wizard (Hoffmann et al. 2008: 80; Baroni and Evert 2009),[13] which enables one to measure the precision of the estimate by calculating a confidence interval at the level of 95 % (i.e. there is a 5 % risk that at a given confidence interval the phrase so to speak performs another discourse function than marking prefabricated idiomatic expressions). Based on the analysis of a random sample of 100 concordances (as above), where so to speak marks prefabricated language 15 times, we found that the 95 % confidence interval ranges from 8.91 % to 23.85 % of the total number of occurrences (1,321). In other words, this means that so to speak marks prefabricated language 118–315 times in the analysed dataset.

As such a confidence interval is wide and imprecise, and that in any other sample the obtained figures would be different, we decided to use another random sample and subsequently merge both samples in order to lower the confidence interval and neutralize the impact of data variability in the samples. Hence, we inspected one more sample of 100 random occurrences of the phrase so to speak in the COCA 2020 Spoken, and found as many as 24 examples of prefabricated phrasings marked by the said phrase, namely brotherly love (OED), love interest (OED), take a break (MWeb), turn the tide (OED), fall into wrong hands (OED, CaD, MWeb), (take somebody) over the cliff (CaD), (walk) the middle path (OED, CaD, MWeb), get somebody by the short hairs (CaD), fall on one’s own sword (OED, MWeb), clear the air (OED, CaD), kick the tires (OED, CaD), make the grade (OED, CaD, MWeb), clean up one’s act (OED, MWeb), come to someone’s rescue (OED, CaD, MWeb), cut ones’s teeth on something (OED, CaD), (get) ahead of the curve (OED, CaD, MWeb), brain drain (OED, CaD, MWeb), pass the buck (OED, CaD, MWeb), (to be) an average Joe (OED), (to be) off the books (OED, CaD, MWeb), (to have someone) under someone’s nose (OED, CaD, MWeb), a top dog (OED, CaD, MWeb), to go out of business (CaD, MWeb), to weep about spilled milk (OED, CaD, MWeb[14]). Selected examples (28–30) are presented below:

| I think that certainly, after the votes are certified in Florida, somebody should step forward and fall on their sword, so to speak , and concede. (id: 110493_41, BNC_text_id: 110493) |

| Now in the 1990s, only because we ’re left with such a dire consequence of misuse in every area, that we ’re starting to clean up the act, so to speak . (id: 220986_535, BNC_text_id: 220986) |

| He trained and cut his teeth, so to speak , on assassination attempts first as a street thug, as a teenager, in his hometown of Tikrit, went off to Baghdad, joined the party. (id: 148784_100, BNC_text_id: 148784) |

It was revealed that after merging two data samples, the 95 % confidence interval was lowered to 14.39–25.81 % of the total number of occurrences (1,321), which stands for 190–341 occurrences in the full dataset. Hence, we obtained preliminary evidence showing that in 14–25 % of cases, the phrase so to speak marks prefabricated idiomatic expressions in COCA 2020 Spoken corpus (with a 5 % risk that the estimate is incorrect).

5 Discussion and conclusions

In this paper, we attempted, first, to describe the use of semantically and pragmatically similar, according to dictionary definitions, recurrent phrases labelled under an umbrella term ‘phraseology markers’ (PMs), and second, to measure the PMs’ capacity to demarcate prefabricated idiomatic expressions in texts.

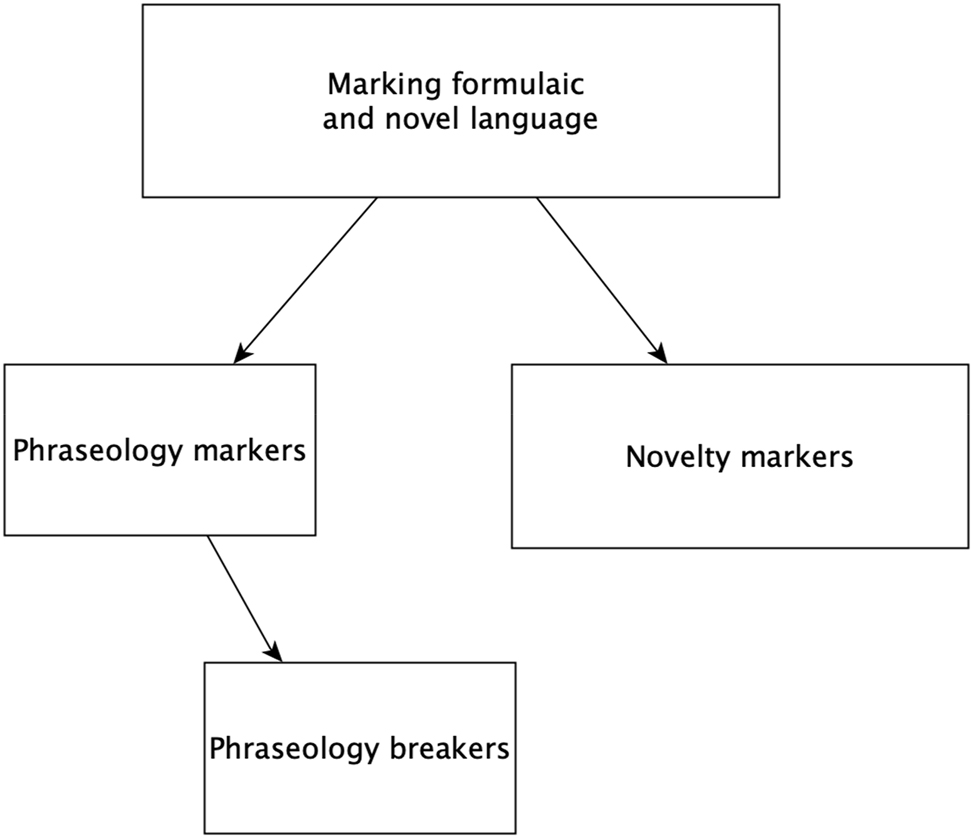

The study findings revealed that apart from marking the use of metaphorical or unusual phrasings in particular situations of language use, the investigated PMs perform important roles with respect to marking prefabricated expressions in spoken language, be it English and Polish. More precisely, we found that the PMs under scrutiny perform two opposing functions with respect to the use of formulaic language. On the one hand, they are used to mark conventional, prefabricated expressions that contribute to formulaicity of speaker’s utterances. On the other hand, we identified contexts where the same PMs are used to mark expressions or phrases that represent unusual, unconventional, idiosyncratic phrasings unattested or rarely used in native texts. We believe that some of those phrases represent so-called phraseological innovations[15] (Bąba 1989) as they do not conform with the established – at a given point in time – phraseological norm (ibid.). Based on our findings, we put forward a hypothesis that breaking the fixed or stereotypical form of formulaic language and/or conventions of its use may be facilitated by certain phrases that in this paper (and in specialized literature, cf. Section 1 and 2) are referred to as ‘phraseology markers’. Hence, paradoxically, the phrasings usually referred to as phraseology markers occasionally perform the function of ‘phraseology breakers’, where the fixed or canonical form of a phraseological unit is modified yet it is still possible for speakers or writers to intuitively trace back to its very source, i.e. the canonical form. In addition, those phrasings may also be used to signal novel and idiosyncratic, unconventional word combinations, rarely or never attested in language corpora, and hence, we may also refer to them as ‘novelty markers‘. In short, the findings showed that phrasings, such as so to say, so to speak, as it were etc., are pragmatically multifunctional as in different contexts of use they may perform the roles of ‘phraseology markers’ (i.e. marking phraseological prefabrication or idiomaticity), ‘phraseology breakers’ (i.e. marking phraseological innovations or variability) and ‘novelty markers’ (i.e. marking highly-individualized, idiosyncratic phrasings). This concise typology of expressions used to explicitly mark linguistic units as either formulaic or compositional is outlined in Figure 1, where phraseology breakers are shown as a subtype of phraseology markers.

A conceptual outline of devices used to explicitly mark formulaic and compositional expressions.

Based on the results, we also hypothesize that ‘breaking phraseology’ or’ breaking formulaicity’, as facilitated by the PMs, should not be treated as an instance of habitual and unconscious language use; neither should it be treated as an optional, conscious and regular language use that can account for speaker’s or writer’s idiolectal style. Conversely, we put forward the claim that ‘breaking formulaicity’, through phrases such as so to say, so to speak, as it were etc., is an optional and conscious choice on the part of language speakers yet, at the same time, it represents irregular and idiosyncratic language use (i.e. the means of signalling one-off occurrences of linguistic novelty or idiosyncrasy). With respect to such idiosyncratic language use, Taylor (2014: 278–279) argues that instead of drawing a binary distinction between regular and irregular language use, we should consider it as a cline between creativity and innovative extensions, the latter standing for those cases where syntactic and semantic properties of a linguistic expression, including prefabricated phrases, conflict with more general usage norms. Thus, we assume that such innovative extensions may also encompass situations when formulaic language is used in atypical ways, e.g., when its fixed form is broken, and new variants of phraseological expressions (with novel internal variation) are used, and that such atypical forms can be signalled explicitly using phraseology breakers. In a similar vein, Miller (2014: 19) argues that creativity is the ability to “break formulaicity and re-form patterns” of language use, and that is precisely what we deal with when we inspect how phraseology markers/breakers are used in texts. More precisely, the phrases such as że tak powiem and so to speak have the capacity to mark the use of novel and idiosyncratic word combinations, which include one-off occurrences specific to situations of language use, often hardly attested in reference corpora and not recorded as lexical entries in dictionaries of contemporary English and Polish. Such lexical items, however, may provide valuable data for upgrading lexicographic resources with novel phraseological innovations.

Next, taking the English phrase so to speak as a case in point, we focused on its pragmatic function of phraseology marker and attempted to measure how much prefabricated language that English phrase marks when used in the Spoken component of the COCA 2020 corpus. It was found to be in the range of 14–25 % of its total number of occurrences. On the one hand, we can argue that phraseology markers such as so to speak can, in general, be treated as complementary methods of identification of idiomatic expressions in texts, and that their potential in that respect is still underexplored. As a matter of fact, one of the important discourse functions of such items, which is not explicated in dictionaries of contemporary English and Polish, is to mark instances of prefabricated language, which can be used with various purposes in mind (for emphasis, irony, unusual stylistic effect etc.) across various contexts of use. This finding may be particularly useful for foreign or second language learners as it may help them improve fluency and naturalness of their spoken language. On the other hand, the finding that the phrase so to speak marks prefabricated language only in the range of 14–25 % of its occurrences in the COCA 2020 Spoken corpus implies that its function of a phraseology marker is not a central one and that in the range of 75–86 % of its occurrences it may perform the function of phraseology breaker or novelty marker, among other more fine-grained discoursal functions. This claim, however, should be further verified in future studies.

This study has its limitations which primarily pertain to methodology. First, we investigated only a small subjective selection of phraseology markers and compared their use and discourse functions in various yet not fully comparable corpora of English and Polish, including general-language and spoken corpora. Second, an attempt at measuring the amount of prefabricated language signalled by phraseology markers was made taking only one item, the English phrase so to speak, as a case in point, which leaves us with the question whether our observations should be directly transferred to Polish phraseology markers. It therefore seems that future studies should be conducted using more balanced and comparable corpora (e.g., register-specific) where more units of analysis could be explored in greater detail in order to arrive at more precise estimates and more comprehensive descriptive findings. In a similar vein, it may be worthwhile exploring in greater detail the extent to which phraseology markers, similar to the ones studied in this paper, signal prefabricated language across different languages, also across various text types, genres and modalities (spoken and written). Also, it might be interesting to study sentence-positions of phraseology markers across languages as they may precede, occur inside or follow phraseologisms or phraseological innovations. Finally, more sophisticated statistical methods (e.g., regression models) may be employed to determine contextual conditions impacting the ways speakers or writers typically use phraseology markers. We hope, however, that our study is a good starting point for such future research.

Funding source: The research described in this paper was facilitated by the project titled "CLARIN – Common Language Resources and Technology Infrastructure", which is financed under the 2014–2020 Smart Growth Operational Programme

Award Identifier / Grant number: POIR.04.02.00-00C002/19

-

Research funding: The research described in this paper was facilitated by the project titled “CLARIN – Common Language Resources and Technology Infrastructure”, which is financed under the 2014–2020 Smart Growth Operational Programme, POIR.04.02.00-00C002/19.

Dictionaries

OED (lexico.com, until August 27, 2022).

Oxford English Dictionary = Oxford English Dictionary, https://lexico.com (until August 27, 2022, afterwards: https://oed.com).

Cambridge Dictionary of English.

Cambridge Dictionary = Cambridge Dictionary, https://dictionary.cambridge.org/.

Merriam-Webster Dictionary.

Merriam-Webster = Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary.

Wielki słownik języka polskiego PAN.

WSJP = Żmigrodzki, Piotr, (ed). 2006–. Wielki słownik języka polskiego PAN. Kraków: IJP PAN. https://wsjp.pl/.

Corpora

British National Corpus (BNC), accessed at: http://pelcra.clarin-pl.eu/SlopeqBNC/.

BNC Consortium. 2007. The British National Corpus, XML Edition, Oxford Text Archive, http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12024/2554.

British National Corpus 2014 Spoken (BNC Spoken 2014), accessed at: https://www.sketchengine.eu/british-national-corpus-2014-spoken/.

Love, Robbie, Claire Dembry, Andrew Hardie, Vaclav Brezina & Tony McEnery. 2017. The Spoken BNC2014: designing and building a spoken corpus of everyday conversations. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics 22(3). 319–344. DOI: 10.1075/ijcl.22.3.02lov.

Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA) 2020, accessed at: https://www.english-corpora.org/coca/.

Davies, Mark. 2008. The corpus of contemporary American English (COCA). Available at: https://www.english-corpora.org/coca/.

enTenTen15, accessed at: https://www.sketchengine.eu/ententen-english-corpus/.

Jakubíček, Milos, Adam Kilgarriff, Vojtech Kovář, Pavel Rychlý & Vit Suchomel. 2013. The TenTen corpus family. In Andrew Hardie & Robbie Love (eds.), Abstract Book. Corpus Linguistics 2013. Lancaster: UCREL, 125–127. https://ucrel.lancs.ac.uk/cl2013/doc/CL2013-ABSTRACT-BOOK.pdf.

Narodowy Korpus Języka Polskiego (National Corpus of Polish, NKJP), accessed at: http://www.nkjp.uni.lodz.pl/.

Przepiórkowski, Adam, Mirosław Bańko, Rafał Górski & Barbara Lewandowska-Tomaszczyk (eds.). 2012. Narodowy Korpus Języka Polskiego. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN.

Spokes, accessed at: http://spokes.clarin-pl.eu/.

Pęzik, Piotr. 2015. Spokes – a search and exploration service for conversational corpus data. In Selected Papers from the CLARIN 2014 Conference, October 24–25, 2014, 99–109. The Netherlands: Soesterberg.

MoncoPL, accessed at: http://monco.frazeo.pl/.

Pęzik, Piotr. 2020. Budowa i Zastosowania Korpusu Monitorującego MoncoPL. Forum Lingwistyczne 7. 133–150.

plTenTen12, accessed at: https://www.sketchengine.eu/pltenten-polish-corpus/.

References

Andrejewicz, Urszula. 2015. Koń się śmieje, czyli czy istnieją błędy frazeologiczne? Poradnik Językowy 2. 44–50.Search in Google Scholar

Baranov, Anatoli & Dmitrij Dobrovolskij. 2008. Аспекты теории фразеологии [Aspects of the Theory of Phraseology]. Moscow: Znak.Search in Google Scholar

Baroni, Marco & Stefan Evert. 2009. Statistical methods for corpus exploitation. In Anke Lüdeling & Merja Kytö (eds.), Corpus linguistics. An International handbook, 777–803. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.10.1515/9783110213881.2.777Search in Google Scholar

Bartmiński, Jerzy. 2002. Etnolingwistyka. Wielka Encyklopedia Powszechna PWN, vol. 8. Warszawa: PWN.Search in Google Scholar

Bąba, Stanisław. 1989. Innowacje frazeologiczne współczesnej polszczyzny. Poznań: Wydawnictwo Naukowe UAM.Search in Google Scholar

Bąba, Stanisław. 2009. Frazeologia polska. Studia i szkice. Poznań: Wydawnictwo Naukowe UAM.Search in Google Scholar

BNC, Consortium. 2007. The British national corpus, XML edition. Oxford Text Archive. Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12024/2554.Search in Google Scholar

Čermák, František. 2005. Text introducers of proverbs and other idioms. Jezikoslovije 6(1). 57–77.Search in Google Scholar

Chlebda, Wojciech. 2003. Elementy frazematki: Wprowadzenie do frazeologii nadawcy. Łask: Oficyna Wydawnicza Leksem.Search in Google Scholar

Chlebda, Wojciech. 2010. Nieautomatyczne drogi dochodzenia do reproduktów wielowyrazowych. In Wojciech Chlebda (ed.), Na tropach reproduktów: w poszukiwaniu wielowyrazowych jednostek języka, 15–35. Opole: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Opolskiego.Search in Google Scholar

Davies, Mark. 2008. The corpus of contemporary American English (COCA). Available at: https://www.english-corpora.org/coca/.Search in Google Scholar

Forsyth, Richard & Łukasz Grabowski. 2015. Is there a formula for formulaic language? Poznań Studies in Contemporary Linguistics 54(1). 511–549. https://doi.org/10.1515/psicl-2015-0019.Search in Google Scholar

Fraser, Bruce. 1996. Pragmatic markers. Pragmatics 6(2). 167–190. https://doi.org/10.1075/prag.6.2.03fra.Search in Google Scholar

Fraser, Bruce. 1999. What are discourse markers? Journal of Pragmatics 31(7). 931–952. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0378-2166(98)00101-5.Search in Google Scholar

Gałkowski, Błażej. 2006. Kompetencja formuliczna a problem kultury i tożsamości w nauczaniu języków obcych. Kwartalnik Pedagogiczny 4. 163–180.Search in Google Scholar

Hanks, Patrick. 2013. Lexical analysis: Norms and exploitations. Cambridge Mass.: MIT Press.10.7551/mitpress/9780262018579.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Hoey, Michael. 2005. Lexical priming: A new theory of words and language. London: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Hoey, Michael. 2007. Lexical priming and literary creativity. In Michael Hoey, Michaela Mahlberg, Michael Stubbs & Wolfgang Teubert (eds.), Text, discourse and corpora, 7–30. London: Bloomsbury.Search in Google Scholar

Hoffmann, Sebastian, Stefan Evert, Nicholas Smith, David Lee & Ylva Berglund Prytz. 2008. Corpus linguistics with BNCweb: A practical guide. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.Search in Google Scholar

Jakubíček, Milos, Adam Kilgarriff, Vojtech Kovář, Pavel Rychlý & Vit Suchomel. 2013. The TenTen corpus family. In Andrew Hardie & Robbie Love (eds.), Abstract book. Corpus linguistics 2013, 125–127. Lancaster: UCREL. https://ucrel.lancs.ac.uk/cl2013/doc/CL2013-ABSTRACT-BOOK.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

Kilgarriff, Adam, Vit Baisa, Vojtech Bušta, Milos Jakubícek, Vojtech Kovář, Michelfeit Jan, Pavel Rychlý & Vit Suchomel. 2014. The sketch engine: Ten years on. Lexicography 1(1). 7–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40607-014-0009-9.Search in Google Scholar

Lewicki, Andrzej Maria. 2003. Studia z teorii frazeologii. Łask: Oficyna Wydawnicza Leksem.Search in Google Scholar

Lenk, Uta. 1998. Marking discourse coherence: Functions of discourse markers in Spoken English. Berlin: Gunter Narr Verlag.Search in Google Scholar

Love, Robbie, Claire Dembry, Andrew Hardie, Vaclav Brezina & Tony McEnery. 2017. The Spoken BNC2014: Designing and building a spoken corpus of everyday conversations. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics 22(3). 319–344. https://doi.org/10.1075/ijcl.22.3.02lovSearch in Google Scholar

MacKenzie, Ian & Martin Kayman (eds.). 2019. Formulaicity and creativity in language and literature. London: Routledge.10.4324/9781315194295Search in Google Scholar

Mel’čuk, Igor & Jasmina Milićević. 2020. An advanced introduction to semantics. A meaning-text approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/9781108674553Search in Google Scholar

Miller, Gary. 2014. English Lexicogenesis. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199689880.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Nelson, Robert. 2018. How ‘chunky’ is language? Some estimates based on Sinclair’s Idiom Principle. Corpora 13(3). 431–460. https://doi.org/10.3366/cor.2018.0156.Search in Google Scholar

Pęzik, Piotr. 2012. Język mówiony w NKJP. In Adam Przepiórkowski, Miroslaw Bańko, Rafał Górski & Barbara Lewandowska-Tomaszczyk (eds.), Narodowy Korpus Języka Polskiego, 37–47. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN.Search in Google Scholar

Pęzik, Piotr. 2015. Spokes – a search and exploration service for conversational corpus data. In Selected Papers from the CLARIN 2014 Conference, October 24–25, 2014, 99–109. The Netherlands: Soesterberg.Search in Google Scholar

Pęzik, Piotr. 2018. Facets of prefabrication. Perspectives on modelling and detecting phraseological units. Łódź: Wydawnictwo UŁ.Search in Google Scholar

Pęzik, Piotr. 2020. Budowa i Zastosowania Korpusu Monitorującego MoncoPL. Forum Lingwistyczne 7. 133–150. https://doi.org/10.31261/fl.2020.07.11.Search in Google Scholar

Piirainen, Elisabeth, Natalia Filatkina, Sören Stumpf & Christian Pfeiffer (eds.). 2020. Formulaic language and new data. Berlin & Boston: De Gruyter.10.1515/9783110669824Search in Google Scholar

Przepiórkowski, Adam, Mirosław Bańko, Rafał Górski & Barbara Lewandowska-Tomaszczyk (eds.). 2012. Narodowy Korpus Języka Polskiego. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN.Search in Google Scholar

Ranger, Graham. 2018. Discourse markers: An enunciative approach. Berlin: Springer.10.1007/978-3-319-70905-5Search in Google Scholar

Rojo, Jorge Leiva. 2019. Metatextual indicators and phraseological units in a multimodal corpus. Delimitation and essential characteristics of As the Saying Goes and implications for interpreting. Translation and Translanguaging in Multilingual Contexts 5(3). 241–258. https://doi.org/10.1075/ttmc.00034.lei.Search in Google Scholar

Rozumko, Agata. 2011. Proverb introducers in a cross-linguistic and cross-cultural perspective. A contrastive study of English and Polish tags used to introduce proverbs. In Joanna Szerszunowicz, Bogusław Nowowiejski, Katsumasa Yagi & Kanzaki Takaaki (eds.), Research on phraseology in Europe and Asia: Focal issues of phraseological studies, 315–330. Białystok: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu w Białymstoku.Search in Google Scholar

Ruiz-Gurillo, Leonor. 2015. Phraseology of humor in Spanish: Types, functions and discourses. Lingvisticae investigaciones: International Journal of Linguistics and Language Resources 38(2). 191–212. https://doi.org/10.1075/li.38.2.01rui.Search in Google Scholar

Sandomirska, Irina. 2000. O metaforach życia i śmierci w stałych związkach wyrazowych w języku rosyjskim. In Anna Dąbrowska & Janusz Anusiewicz (eds.), Językowy obraz świata i kultura, 355–367. Wrocław: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Wrocławskiego.Search in Google Scholar

Schiffrin, Deborah. 1987/1996. Discourse markers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511611841Search in Google Scholar

Schmitt, Norbert & Ronald Carter. 2004. Formulaic sequences in action: An introduction. In Norbert Schmitt (ed.), Formulaic sequences: Acquisition, processing and use, 1–22. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/lllt.9.02schSearch in Google Scholar

Siepmann, Dirk. 2005. Discourse markers across languages: A contrastive study of second-level discourse markers in native and non-native text with implications for general and pedagogic lexicography. London: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Stede, Manfred & Birte Schmitz. 2000. Discourse particles and discourse functions. Machine Translation 15. 125–147. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1011112031877.10.1023/A:1011112031877Search in Google Scholar

Szerszunowicz, Joanna. 2020. New pragmatic Idioms in Polish: An integrated approach in pragmateme research. In Elisabeth Piirainen, Natalia Filatkina, Sören Stumpf & Christian Pfeiffer (eds.), Formulaic language and new data, 173–196. Berlin: De Gruyter.10.1515/9783110669824-008Search in Google Scholar

Taylor, John. 2014. The mental corpus: How language is represented in the mind. Oxford: OUP.Search in Google Scholar

Trklja, Aleksandar & Łukasz Grabowski (eds.). 2021. Formulaic language: Theories and methods. Berlin: Language Science Press.Search in Google Scholar

Wierzbicka, Anna. 2015. A whole cloud of culture condensed into a drop of semantics: The meaning of the German word Herr as a term of address. International Journal of Language and Culture 2(1). 1–37. https://doi.org/10.1075/ijolc.2.1.01wie.Search in Google Scholar

Wood, David. 2015. Fundamentals of formulaic language. London: Bloomsbury.Search in Google Scholar

Woźniak, Michał. 2017. Jak znaleźć igłę w stogu siana? Automatyczna ekstrakcja wielosegmentowych jednostek leksylalnych z tekstu polskiego. Kraków: IJP PAN.Search in Google Scholar

Wray, Alison. 2002. Formulaic language and the lexicon. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511519772Search in Google Scholar

Wray, Alison. 2008. Formulaic language. Pushing the boundaries. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- The production of English monophthong vowels by Saudi L2 speakers

- Cartographic architecture of DP

- Parasitic gap patterns and hierarchy preservation in German

- Marking and breaking phraseology in English and Polish: a comparative corpus-informed study

- A tale of two tool(kit)s: from canonical antonymy to non-canonical opposition in the Qur’anic discourse

- The role of lexical context and language experience in the perception of foreign-accented segments

- From verb to epistemic marker: bini in Hamedanian Persian

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- The production of English monophthong vowels by Saudi L2 speakers

- Cartographic architecture of DP

- Parasitic gap patterns and hierarchy preservation in German

- Marking and breaking phraseology in English and Polish: a comparative corpus-informed study

- A tale of two tool(kit)s: from canonical antonymy to non-canonical opposition in the Qur’anic discourse

- The role of lexical context and language experience in the perception of foreign-accented segments

- From verb to epistemic marker: bini in Hamedanian Persian