Abstract

Left-node-raising (LNR), as a mirror image of right-node-raising (RNR), is a phenomenon in which the leftmost constituent is shared by the two conjuncts. In this paper, we empirically and theoretically explore two distinctive properties of LNR in Korean: licensing Case-mismatches of a shared element and the dependent plural marker tul. We argue that the first conjunct Case-licensing of the shared element in LNR is crucial across Case types. We thus confirm the explanatory edge of the scrambling-plus-pro analysis of LNR, nullifying previous symmetric analyses of LNR such as across-the-board scrambling and multidominance. Additionally, we argue that LNR is not a mirror image of RNR in that symmetric analyses may explain the distribution of the dependent plural marker in RNR but not that of the dependent plural marker in LNR. Therefore, we argue against a unified analysis of RNR and LNR. We further show that the island effect of LNR is evidence of the scrambling-plus-pro analysis of LNR.

1 Introduction[1]

Right-node-raising (RNR) is a phenomenon in which the rightmost constituent is apparently shared by the two conjuncts, as shown in (1).

|

John made, and Mary ate, a cake. |

The shared element (i.e., pivot) a cake in (1), semantically belonging in both conjuncts, is pronounced only in the second conjunct.

Following Yatabe (2001), Nakao (2009, 2010 observes that Japanese has a mirror image of RNR, which is called left-node-raising (LNR), as illustrated in (2).

| Keeki-o | John-ga | tukuri, | (soshite) | Mary-ga | tabeta. |

| cake-Acc | John-Nom | makeAcc | (and) | Mary-Nom | ateAcc |

| ‘The cake, John made, and Mary ate.’ (Nakao 2010: 151) | |||||

Chung (2010) also observes that Korean has LNR as in (3).

| Kheyikhu-lul | John-i | mantul-ko, | Mary-ka | mekessta. |

| cake-Acc | John-Nom | makeAcc-and | Mary-Nom | ateAcc |

| ‘The cake, John made, and Mary ate.’ (Chung 2010: 52) | ||||

In LNR, the pivot keeki-o ‘cake-Acc’ in (2) and kheyikhu-lul ‘cake-Acc’ in (3) should be interpreted as the missing argument in each conjunct. Several analyses have been put forward to account for the nature and derivation of LNR in Japanese and Korean (Abe and Nakao 2009; Chung 2010; Kim et al. 2020; Nakao 2009, 2010; Park and Lee 2009; Yatabe 2001).

Among others, Nakao (2009, 2010 proposes that LNR is an instance of across-the-board (ATB) scrambling of the pivot. Nakao claims that the pivot NP must match in Case with the predicate in both conjuncts. She provides the example in (4) as the evidence of her claim:

| ??Mary-ni | John-ga | hana-o | okuri, | Tom-ga | nagusameta. |

| Mary-Dat | John-Nom | flower-Acc | sendDat | Tom-Nom | comfortedAcc |

| ‘Mary, John sent a flower, and Tom comforted.’ (Nakao 2010: 157) | |||||

In (4) the first conjunct predicate okuri ‘send’ assigns dative Case to its indirect object, and the second conjunct predicate nagusameta ‘comforted’ assigns accusative Case to its direct object. According to Nakao’s observation, such a Case-mismatch degrades LNR.

However, Kim et al. (2020) attest, via a formal experiment, that the Case-mismatch in LNR is acceptable when the Case of a pivot is licensed in the first conjunct, as shown in (5):

| Mary-eykey | oppa-ka | kkochtapal-ul | cwu-ko, |

| Mary-Dat | brother-Nom | bouquet-Acc | give-and |

| emma-ka | ttattushakey | macihayssta. | |

| mom-Nom | warmly | welcomed | |

| ‘Mary, her brother gave a bouquet, and her mom welcomed warmly.’ | |||

Having a similar syntactic configuration with (4), the well-formedness presented in the example (5) could be a burden for the symmetric accounts proposed by Nakao (2009, 2010 and Chung (2010). This is one of the disputes we would like to resolve.

In addition, we will settle another dispute of whether the Korean dependent plural marker (DPM) tul within the pivot is allowed in LNR or not:

| (*)Yelsimhi-tul, | John-un | chayk-ul | ilk-ko, | Mary-nun | nonmwun-ul | ilkessta. |

| diligently-DPM | John-Top | book-Acc | read-and | Mary-Top | article-Acc | read |

| ‘Diligently, John read books, and Mary read articles.’ (Chung 2010: 63) | ||||||

Chung (2010) reports that (6) is grammatical and argues that its grammaticality supports his multidominance analysis. By contrast, Kim (2019) reports that (6) is unacceptable via a survey of 30 native speakers’ intuitions.

In this light, this study explores LNR constructions, experimentally resolving two disputes of whether the Case-mismatched LNR is allowed or not and whether the left-node-raised (i.e., LNRed) DPM tul is allowed or not. This paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we discuss the theoretical predictions of our hypotheses on the well-formedness of Korean LNR constructions: Case-mismatches and DPMs. In Section 3, we present two acceptability experiments with a 2 × 2 factorial design. In Section 4, we discuss how our experimental findings impact the three types of syntactic analyses that have been proposed to capture the LNR phenomenon in Japanese/Korean: ATB movement, multidominance, and scrambling-plus-pro. We conclude in Section 5.

2 Theoretical predictions

2.1 Locus

Nakao (2009, 2010 and Chung (2010) argue that the pivot in LNR syntactically belongs to both conjuncts because the pivot is a complement of each predicate simultaneously. More precisely, Nakao obtains this by assuming that the pivot originates as two separate XPs but has undergone ATB movement into one XP position as in (7), while Chung claims that the pivot is multidominated by each predicate and has moved out of the shared position as in (8).

| ATB movement analysis (Nakao 2009, 2010) | |||||

| (*)Mary1-Dat | [brother-Nom | t1 | bouquet-Acc | giveDat-and] | |

| [mom-Nom | t1 | warmly | welcomedAcc] | ||

| multidominance analysis (Chung 2010) |

|

In the symmetric analyses of Japanese/Korean LNR, any Case-mismatch is predicted to be ill-formed. Since the pivot is Case-assigned by each predicate independently, its Case-marker is supposed to be licensed by each predicate. If the predicates assign different Case – dative Case and accusative Case as in (7) and (8) – there would be a derivational crash due to the Case-mismatch, regardless of where the Case-mismatch occurs.

In contrast, Kim et al. (2020) argue that the pivot in Korean LNR belongs to the first conjunct only. As shown in (9), the pivot is the complement of the first conjunct predicate, and the missing complement in the second conjunct is a null pronominal pro:

| scrambling-plus-pro analysis (Kim et al. 2020) | |||||

| (*)Mary1-Dat | [brother-Nom | t1 | bouquet-Acc | giveDat-and] | |

| [mom-Nom | pro | warmly | welcomedAcc] | ||

Under the asymmetric analysis depicted in (9), the pivot is Case-assigned by the first conjunct predicate.

2.2 Case types

Chomsky (1986) proposes that unlike structural Case, inherent Case is related to θ-role assignment. More precisely, Chomsky (1995) argues that structural Case is assigned solely in terms of S-structure configuration whereas inherent Case is associated with θ-assignment. This argument leads us to an interesting hypothesis regarding the Case type of a pivot in Case-mismatched LNR. A dative predicate can assign a goal θ-role along with dative Case (i.e., inherent Case); therefore, the Case-mismatched accusative pivot would pay a penalty if it should function as an argument of a dative predicate because of Case-mismatches. In contrast, an accusative predicate would not give a penalty to the Case-mismatched dative pivot since structural Case is assigned irrespective of θ-assignment. The derivations in (10) schematize this hypothesis:

| Mary-eykey | [oppa-ka | kkochtapal-ul | cwu-ko], | |

| Mary-Dat | brother-Nom | bouquet-Acc | giveDat-and | |

| [emma-ka | ttattushakey | macihayssta] | ||

| mom-Nom | warmly | welcomedAcc | ||

| ‘Mary, her brother gave a bouquet, and her mom welcomed warmly.’ | ||||

| Mary-lul | [emma-ka | tattushakey | maciha-ko], |

| Mary-Acc | mom-Nom | warmly | welcomeAcc-and |

| [oppa-ka | kkochtapal-ul | cwuessta] | |

| brother-Nom | bouquet-Acc | gaveDat | |

| ‘Mary, her mom welcomed warmly, and her brother gave a bouquet.’ | |||

According to this hypothesis, when the pivot is marked with dative Case as in (10a), the accusative predicate macihayssta ‘welcomedAcc’ would interpret the pivot as its (theme) argument. However, when the pivot carries an accusative Case-marker as in (10b), the dative predicate cwuessta ‘gaveDat’ would pay a penalty for the interpretation of the pivot as its (goal) argument. This penalty would attenuate acceptability. In this sense, we hypothesize that Case-mismatches with a dative pivot would be preferred than those with an accusative pivot in terms of acceptability.

2.3 Dependent plural markers

As mentioned in Section 1, the acceptability (or grammaticality) of (6) in which the DPM is attached to the pivot may be an interesting test ground for each of the previous analyses. If Chung’s (2010) observation of (6) being grammatical is attested, then (6) might be nicely accounted for by his multidominance proposal, as schematized in (11).

|

Since the multidominated pivot was c-commanded by the split plural subject John + Mary prior to fronting, the dependent-plural-marked (DPMed) pivot was successfully licensed under the multidominance proposal.

On the other hand, it is not clear how the DPMed pivot might be licensed under either the ATB movement or the scrambling-plus-pro proposal. That is, it is hard to imagine a derivational step in which the DPMed pivot meets a c-commanding (split) plural subject. Notice, however, that Chung’s (2010) multidominance argument only holds as far as the DPMed pivot in LNR such as (7) is acceptable.

Based on these theoretical predictions of LNR, we conduct an experimental and theoretical investigation of Korean LNR.

3 Experiments

In this section, we examine the conflicting predictions from the previous analyses of Korean LNR, concerning whether LNR would be sensitive to the locus of Case-licensing, Case types, and DPMs.

3.1 Experiment 1

In Experiment 1, we replicated Kim et al.’s (2020) experiment.

3.1.1 Participants, materials, and design

Fifty self-reported native Korean speakers (age: mean [SD] = 22.4 [1.79]), who were all undergraduate students at a university in South Korea, were recruited to participate in the experiment online. They were paid 5,000 won (about $4.00) for their participation, which took about 10 min.[2] We excluded the responses from two participants who were not paying attention during the task (by the procedure described below). Accordingly, only the responses from 48 participants (12 for each of the four lists) were included in the analysis.

Experiment 1 employed a 2 × 2 design, crossing LOCUS (1st [conjunct] vs. 2nd [conjunct]) and CASE (Dat[ive] vs. Acc[usative]), as sampled in (12).

| [1st | Dat] | |||

| Mary-eykey | oppa-ka | kkochtapal-ul | cwu-ko, |

| Mary-Dat | brother-Nom | bouquet-Acc | give-and |

| emma-ka | ttattushakey | macihayssta. | |

| mom-Nom | warmly | welcomed | |

| ‘Mary, her brother gave a bouquet, and her mom welcomed warmly.’ | |||

| [1st | Acc] | |||

| Mary-lul | emma-ka | tattushakey | maciha-ko, |

| Mary-Acc | mom-Nom | warmly | welcome-and |

| oppa-ka | kkochtapal-ul | cwuessta. | |

| brother-Nom | bouquet-Acc | gave | |

| ‘Mary, her mom welcomed warmly, and her brother gave a bouquet.’ | |||

| [2nd | Dat] | |||

| Mary-eykey | emma-ka | ttattushakey | maciha-ko, |

| Mary-Dat | mom-Nom | warmly | welcome-and |

| oppa-ka | kkochtapal-ul | cwuessta. | |

| brother-Nom | bouquet-Acc | gave | |

| ‘Mary, her mom welcomed warmly, and her brother gave a bouquet.’ | |||

| [2nd | Acc] | |||

| Mary-lul | oppa-ka | kkochtapal-ul | cwu-ko, |

| Mary-Acc | brother-Nom | bouquet-Acc | give-and |

| emma-ka | ttattushakey | macihayssta. | |

| mom-Nom | warmly | welcomed | |

| ‘Mary, her brother gave a bouquet, and her mom welcomed warmly.’ | |||

In the [1st] condition, the dative or accusative Case of the pivot is licensed in the first conjunct, whereas in the [2nd] condition, the dative or accusative Case of the pivot is licensed in the second conjunct.[3] The full list of experimental items is available online.[4]

Sixteen lexically-matched sets of the four conditions were constructed, and they were counterbalanced across four lists using a Latin square design so that a list has only one item from each set. Each list thus had 16 experimental items, together with 64 filler items (i.e., experimentals:fillers = 1:4) of comparable length but with varying degrees of acceptability. In total, there were 80 sentences in each list.

3.1.2 Procedure

Both Experiment 1 and Experiment 2 employed the same data collection procedure. We conducted the experiments with a web-based experiment platform Ibex (Drummond 2016). Sentences were presented one at a time on a computer screen and participants were asked to make acceptability judgments on the Likert scale of 1 (very unnatural) to 7 (very natural). In addition to test items, there were 16 “gold standard” filler items. These filler items included eight good and eight bad filler items, which showed either the highest or the lowest acceptability most clearly in the previous tests conducted on about 200 participants prior to the experiment. We obtained the expected value of these fillers from the results of these previous tests. For each gold standard item, we calculated the difference between each participant’s response and its expected value (i.e., 1 or 7). In order to compare the size of the differences that were either positive or negative numbers, we squared each of the differences and summed the squared differences for each participant. This gave us the sum-of-the-squared-differences value of each participant. We excluded any participants whose sum-of-the-squared-differences value was greater than two standard deviations away from the mean (cf. Sprouse et al. 2022).

3.1.3 Data analysis

Prior to analyzing the data, the raw judgment ratings, including both experimental items and fillers, were converted to z-scores in order to eliminate certain kinds of scale biases between participants (Schütze and Sprouse 2013). Linear mixed-effects models were used to analyze the data; these models allow the simultaneous inclusion of random participant and item variables (Baayen et al. 2008). Each model was fit using the maximal random effects structure that converged (Barr et al. 2013). These models were run in the R environment R Core Team 2020 using the lme4 package (Bates et al. 2015). P-value estimates for the fixed and random effects were calculated by the Satterthwaite’s approximation, using the lmerTest package (Kuznetsova et al. 2017). A likelihood ratio test (using the anova( ) function in R) was used to compare multiple models and determine the final model that provided the best fit to the data.

3.1.4 Results and discussion

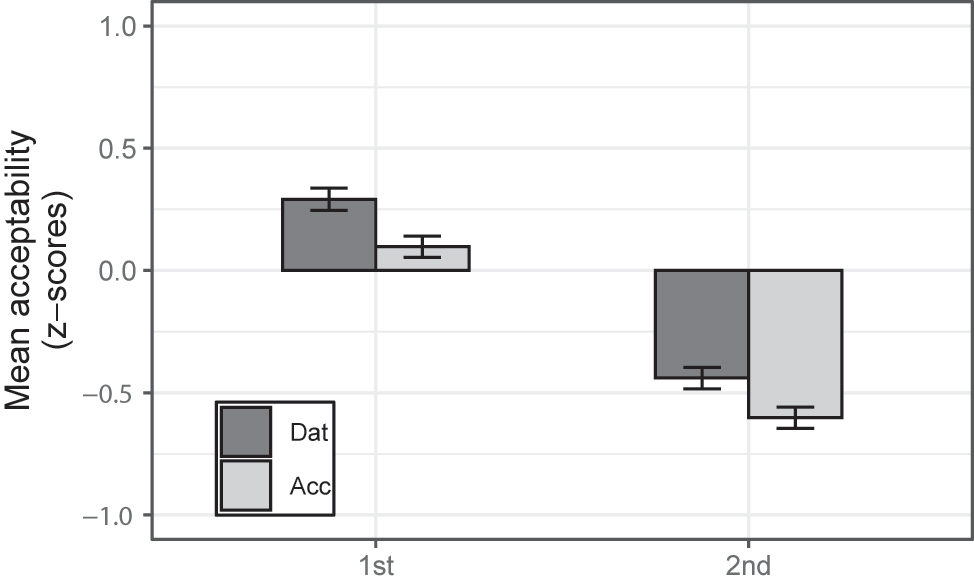

Figure 1 presents the mean z-scores for the acceptability judgments for the four experimental conditions of Experiment 1. The zero represents the overall mean acceptability rating; positive z-scores indicate that conditions are rated towards being acceptable, while negative z-scores indicate that conditions are rated towards being unacceptable.

Mean acceptability of experimental conditions (error bars indicate SE).

The results from the mixed-effects models with LOCUS and CASE as fixed effects, and random intercepts and slopes for participants and items in Table 1 confirmed that the main effect of LOCUS was extremely significant, indicating that the [1st] condition is significantly more acceptable than the [2nd] condition (mean: 0.197 vs. −0.522). The main effect of CASE also proved significant, confirming that the dative condition is significantly more acceptable than the accusative condition (mean: −0.072 vs. −0.252). However, the interaction between the two was not significant (χ2(1) = 0.071, p = 0.789).

Fixed effects summary for Experiment 1.

| Estimate | SE | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 0.107 | 0.065 | 1.640 | 0.106 |

| LOCUS | −0.719 | 0.082 | −8.782 | *** |

| CASE | 0.180 | 0.071 | 2.549 | * |

-

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

The results of Experiment 1 provided two findings. First, Case-mismatches in Korean LNR were conjunct-sensitive. Specifically, the Case-licensing in the first conjunct was more acceptable than that in the second conjunct. Second, the preference for the first conjunct as the Case-licensing locus of pivots was maintained regardless of Case types although Case-mismatched dative pivots were more acceptable than Case-mismatched accusative pivots.

Next, we investigate the effect of the DPM tul on the acceptability ratings of LNR, compared with those of RNR.

3.2 Experiment 2

3.2.1 Participants, materials, and design

Fifty-five self-reported native Korean speakers (age: mean [SD] = 22.65 [2.65]) were recruited. The participants were compensated through the same methods and engaged in the same procedures as in Experiment 1. Three participants were excluded because they did not pay attention during the task. Accordingly, only the responses from 52 participants (13 for each of the four lists) were included in the analysis.

Experiment 2 also employed a 2 × 2 design, crossing SYNTAX (RNR vs. LNR) and PLURALITY (−DPM vs. +DPM). Similar to Experiment 1, 16 lexically matched sets of the four conditions were constructed, as sampled in (13) (parenthesized interpretations added here for clarity):

| [RNR | −DPM] | |||||

| John-i | TOEFL-ul, | Mary-ka | TOEIC-ul, | ||

| John-Nom | TOEFL-Acc | Mary-Nom | TOEIC-Acc | ||

| yelsimhi | kongpwuhayssta. | ||||

| diligently | studied | ||||

| (Maca, | twul | ta | yelsimhi | kongpwuhayssci.) | |

| (right, | both | all | diligently | studied.) | |

| ‘John (studied) TOEFL (diligently), and Mary studied TOEIC diligently.’ | |||||

| [RNR | +DPM] | ||||

| John-i | TOEFL-ul, | Mary-ka | TOEIC-ul, | |

| John-Nom | TOEFL-Acc | Mary-Nom | TOEIC-Acc |

| yelsimhi-tul | kongpwuhayssta. | ||

| diligently-DPM | studied | ||

| (Maca, | twul | ta | yelsimhi | kongpwuhayssci.) |

| (right, | both | all | diligently | studied.) |

| ‘John (studied) TOEFL (diligently), and Mary studied TOEIC diligently.’ | ||||

| [LNR | −DPM] | ||||

| Yelsimhi, | John-i | TOEFL-ul | kaluchi-ko, | |

| diligently | John-Nom | TOEFL-Acc | teach-and | |

| Mary-ka | TOEIC-ul | kongpwuhayssta. | ||

| Mary-Nom | TOEIC-Acc | studied | ||

| (Maca, | yelsimhi | kaluchi-ko | yelsimhi | kongpwuhayssci.) |

| (right | diligently | teach-and | diligently | studied.) |

| ‘Diligently, John taught TOEFL, and Mary studied TOEIC.’ | ||||

| [LNR | +DPM] | ||||

| Yelsimhi-tul, | John-i | TOEFL-ul | kaluchi-ko, | |

| diligently-DPM | John-Nom | TOEFL-Acc | teach-and |

| Mary-ka | TOEIC-ul | kongpwuhayssta. | ||

| Mary-Nom | TOEIC-Acc | studied |

| (Maca, | yelsimhi | kaluchi-ko | yelsimhi | kongpwuhayssci.) |

| (right | diligently | teach-and | diligently | studied.) |

| ‘Diligently, John taught TOEFL, and Mary studied TOEIC.’ | ||||

Regarding the SYNTAX factor, we assessed whether the syntactic difference of RNR conditions and LNR conditions affects the acceptability of the DPM-attached conditions.[5] Regarding the PLURALITY factor, we assessed whether the DPM tul affects the acceptability of RNR and LNR conditions. In each set, we used the most-frequently-used DPM markers such as yelsimhi-tul ‘diligently-DPM’ or kkomkkomhi-tul ‘carefully-DPM’ as sample stimuli, based on Korean Corpus distributed by the National Institute of Korean Language (https://corpus.korean.go.kr).

3.2.2 Results and discussion

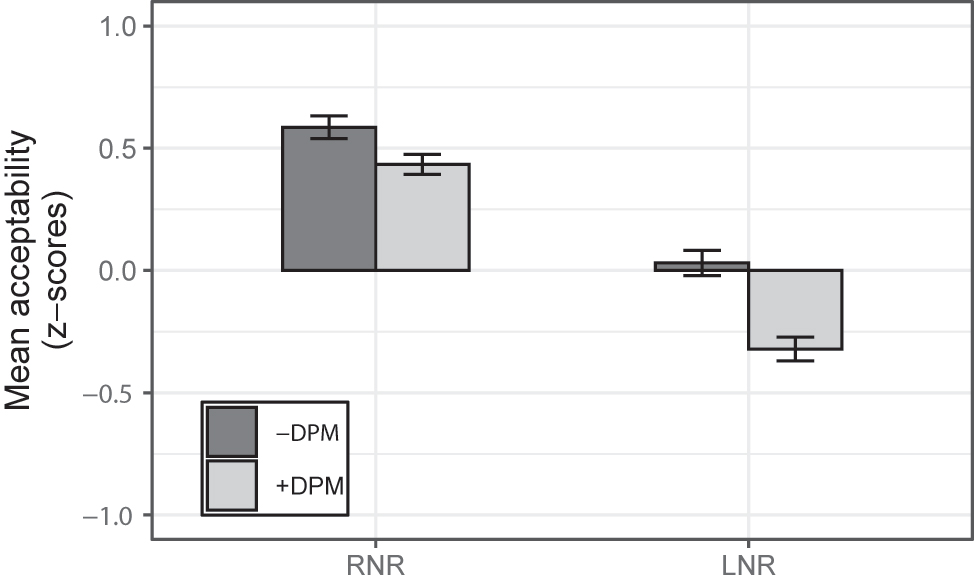

Figure 2 presents the mean z-scores for the acceptability judgments for the four experimental conditions of Experiment 2.

Mean acceptability of experimental conditions (error bars indicate SE).

Table 2 presents the results of the mixed-effects model with SYNTAX and PLURALITY as fixed effects, and random intercepts and slopes for participants and items.

Fixed effects summary for Experiment 2.

| Estimate | SE | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 0.636 | 0.079 | 8.079 | *** |

| SYNTAX | −0.655 | 0.095 | −6.903 | *** |

| PLURALITY | −0.252 | 0.080 | −3.161 | ** |

The main effect of SYNTAX proved significant, confirming that RNR conditions were significantly more acceptable than LNR conditions (mean: 0.510 vs. −0.145). The main effect of PLURALITY was also significant, which confirms that the presence of DPM lowers the rating significantly (mean: 0.308 vs. 0.056). No interaction between the two factors was found (χ2(1) = 1.663, p = 0.197).

However, the results of pairwise comparisons reveal that there was no statistic difference between the [RNR | −DPM] condition and the [RNR | +DPM] condition (β = 0.152, SE = 0.112, t = 1.354, p = 1.000), but the [LNR | −DPM] condition was significantly more acceptable than the [LNR | +DPM] condition (β = 0.352, SE = 0.112, t = 3.140, p < 0.05).[6] More precisely, as seen in Figure 2, the main effect of PLURALITY was produced by a very large difference between the two LNR conditions.

There were two main findings. First, the syntactic difference between RNR and LNR conditions modulated acceptability irrespective of the DPM. That is, RNR conditions were more acceptable than LNR conditions: (13a) was more acceptable than (13c), and (13b) was more acceptable than (13d). Second, the DPM did not modulate the acceptability of RNR conditions but it modulated the acceptability of LNR conditions: the acceptability of (13a) and (13b) was similar, but (13c) was more acceptable than (13d).

4 General discussion and analysis of LNR

The main goal of this study was to investigate the effect of Case-mismatches and DPMs on the acceptability of LNR in Korean. Results from the experiments revealed three things. First, Korean LNR showed a preference for the first conjunct as the Case-licensing locus when pivots were Case-mismatched. Second, this preference was maintained regardless of pivotal Case types: dative or accusative. Third, the DPM within the pivot significantly affected the acceptability of LNR but not that of RNR. Below, we will discuss the theoretical implications of our experimental findings, one by one.

4.1 Case-licensing locus of a pivot

In Korean Case-mismatched LNR, Case-licensing in the first conjunct was more acceptable than Case-licensing in the second conjunct. This conjunct-sensitivity of Case-licensing presents a challenge to the symmetric account of Japanese/Korean LNR (Chung 2010; Nakao 2009, 2010), while supporting the asymmetric account (Kim et al. 2020).

The symmetric account argues that a pivot syntactically belongs to both conjuncts in Japanese/Korean LNR, being simultaneously subcategorized by each conjunct predicate. There are two popular analyses in this approach: the ATB scrambling analysis (Nakao 2009, 2010) and the multidominance analysis (Chung 2010; Nakao 2010).

The ATB scrambling analysis argues that Japanese/Korean LNR is derived via ATB scrambling as in (14).

| ATB scrambling analysis of LNR (Nakao 2009, 2010) | |||||||||||||||

| Keeki1-o | John-ga | t1 | tukuri, | Mary-ga | t1 | tabeta. | (Japanese) | ||||||||

| Kheyikhu1-lul | John-i | t1 | mantul-ko, | Mary-ka | t1 | mekessta. | (Korean) | ||||||||

| cake-Acc | John-Nom | makeAcc-and | Mary-Nom | ateAcc | |||||||||||

| ‘The cake, John made, and Mary ate.’ | |||||||||||||||

In this analysis, as shown in (14), the pivot was base-generated in both conjuncts and has moved simultaneously to the front. Therefore, it should satisfy the requirements for the missing complement position of both predicates, mandating the requirements to be symmetric between the predicates. Aforementioned, one of Nakao’s major arguments for this analysis was the Case-matching effect – the pivot should match with the Case-requirement of both predicates simultaneously, as exemplified again in (15):[7]

| ??Mary-ni | John-ga | hana-o | okuri, | Tom-ga | nagusameta. |

| Mary-Dat | John-Nom | flower-Acc | sendDat | Tom-Nom | comfortedAcc |

According to Nakao’s intuition, (15) is much degraded because the Case of the pivot Mary-ni ‘Mary-Dat’ is not licensed in the second conjunct.

This (apparent but not genuine) Case-matching requirement would also be well captured under the multidominance analysis. As admitted by Nakao herself (2009, 2010), the ATB scrambling analysis of Japanese/Korean LNR may be reformulated from the perspective of multidominance. Nakao (2010) explores this perspective, adopting Citko’s (2005) multidominance analysis of LNR. According to Citko, the pivot is parallelly merged with the predicate in each conjunct, as shown in (16).

| multidominance analysis of LNR |

|

Similar to the ATB scrambling analysis, the pivot in (16) was base-generated as the complement of the predicate in each conjunct, capturing the Case-matching requirement. In this analysis, the pivot must move to a higher position for linearization, obeying Kayne’s (1994) Linear Correspondence Axiom (LCA), which dictates that the precedence in linearization be directly mapped from the c-command relation: XP precedes YP if and only if XP asymmetrically c-commands YP. Accordingly, if a multidominated element stays in-situ, it cannot be linearized.

Above all, our experimental finding suggests that the Case-matching requirement may be violated in certain environments. The symmetric accounts regard the pivot to syntactically originate from both conjuncts, requiring both predicates to assign the same Case to the pivot; thus, any Case-mismatches in LNR would be ruled out. However, this prediction is not compatible with our experimental results:

| Mary-eykey | oppa-ka | kkochtapal-ul | cwu-ko, |

| Mary-Dat | brother-Nom | bouquet-Acc | giveDat-and |

| emma-ka | ttattushakey | macihayssta. | |

| mom-Nom | warmly | welcomedAcc |

| *Mary-eykey | emma-ka | ttattushakey | maciha-ko, |

| Mary-Dat | mom-Nom | warmly | welcomeAcc-and |

| oppa-ka | kkochtapal-ul | cwuessta. | |

| brother-Nom | bouquet-Acc | gaveDat |

In (17), which repeats (12a) and (12c), the accusative predicate macihayssta ‘welcomedAcc’ places a Case requirement that mismatches with the Case morphology of the pivot. The symmetric accounts would invariably rule out both (17a) and (17b), regardless of the location of the mismatching predicate. However, our results showed that the Case-mismatch in the first conjunct as in (17b) was significantly worse than that in the second conjunct as in (17a), demonstrating that Case-licensing in Case-mismatched LNR is conjunct-sensitive.

This conjunct-sensitive finding would be properly explained by an asymmetric account of LNR. In fact, Nakao (2010) explores this possibility. However, she claims that the acceptability of the LNR construction in (18) is different from that of the Null Object Construction (NOC) in (19), and gives up the option of reducing LNR to NOC.

| ??Mary-ni | John-ga | hana-o | okuri, | Tom-ga | nagusameta. |

| Mary-Dat | John-Nom | flower-Acc | sendDat | Tom-Nom | comfortedAcc |

| ‘(To) Mary, John sent a flower, and Tom comforted.’ | |||||

| Mary-ni | John-ga | hana-o | okutta. | Tom-wa | pro | nagusameta. | |

| Mary-Dat | John-Nom | flower-Acc | sentDat | Tom-Top | comfortedAcc | ||

| ‘John sent a flower to Mary. Tom comforted (her).’ (Nakao 2010: 157) | |||||||

Nakao reports that Japanese/Korean NOC as in (19), which resembles LNR as in (18) except that NOC consists of two sentences without coordination, allows the null pronoun pro and its antecedent to have different Case.

Nevertheless, Nakao (2010) adopts a scrambling-plus-resumptive pro analysis, essentially similar to Kim et al.’s (2020) proposal, in accounting for the LNR involving an island, as contrasted in (20) and (21):

| *Ku cikap1-ul | John-i | [t1 cwuwun | salam-ul] | chacass-ko, | |

| the wallet-Acc | John-Nom | pick.up | person-Acc | looked.for-and | |

| Mary-ka | [t1 hwumchin | namca-lul] | ccochassta. | ||

| Mary-Nom | stole | man-Acc | chased | ||

| ‘The wallet, John looked for the person who picked up, and Mary chased the man who stole.’ | |||||

| Ku cikap1-ul | John-i | t1 | cwup-ko, | ||

| the wallet-Acc | John-Nom | picked.up-and | |||

| Mary-ka | [t1 | hwumchin | namca-lul] | ccochassta. | |

| Mary-Nom | stole | man-Acc | chased | ||

| ‘The wallet, John picked up, and Mary chased the man who stole.’ (Kim et al. 2020: 519) | |||||

In (20) the pivot was based-generated within an island in both conjuncts and has scrambled ATB across a relative island, which is ruled out according to her ATB scrambling analysis. Although admitting interspeaker variation, Nakao judges the Japanese counterpart of (21) as being acceptable, where only the second conjunct has a relative island. She claims that (21) does not display the properties of typical LNR, while proposing that this non-typical apparent LNR resorts to a resumptive pro strategy (Ishii 1991) to avoid an island violation. Consider next the example in (22) where the Case-mismatched pivot was base-generated within an island only in the second conjunct:

| Ku yepaywul1-lul | John-i | t1 | wiloha-ko, | |||

| the actress-Acc | John-Nom | comfortAcc-and | ||||

| Mary-ka | [pro | khisuhan | suthokhe-lul] | ccochassta. | ||

| Mary-Nom | kissDat | stalker-Acc | chased | |||

| ‘The actress, John comfortedAcc, and Mary chased the stalker who kissedDat.’ | ||||||

| (Kim et al. 2020: 519) | ||||||

Nakao (2010) first reports that certain speakers including herself accept the Japanese counterpart of (22) and then claims that the second conjunct gap/trace is a null resumptive pronoun, evading an island violation. However, if resumptive pro is not much different from the so-called small pro, the emerging option is that all instances of Japanese/Korean LNR can be accommodated under the umbrella of the NOC proposal: scrambling-plus-pro analysis.[8]

Crucially, Nakao (2010) points out that the Case-mismatched pivot in (22), unlike that in (18), is acceptable. In (22) the first conjunct predicate wiloha ‘comfortAcc’ assigns accusative Case, while the second conjunct predicate khisuha ‘kissDat’ inside the island assigns dative Case. Nakao acknowledges that (22) is as acceptable as (21) for the speakers who accept (21) in spite of the Case-mismatch. This could be well captured by the scrambling-plus-pro analysis. If the apparent pivots ku cicap-ul ‘the wallet-Acc’ in (21) and ku yepaywul-lul ‘the actress-Acc’ in (22) were to move in an ATB fashion, both sentences should have been ruled out. Under the current proposal, the apparent pivots have moved only in the first conjunct via scrambling, and the gap within the island in the second conjunct is pro. Since there is no movement out of islands, (21) and (22) are acceptable.

In this respect, in line with Kim et al. (2020), we propose that Korean LNR constructions can be reduced to NOC constructions, where the pivot is asymmetrically scrambled from the first conjunct and there is a null pronoun pro in the second conjunct, which is anaphoric to the LNRed pivot as in (23):

| Proposal: scrambling-plus-pro (NOC) analysis of LNR |

| [&P NP1 [&P [TP1 … t1 …] [&’ [TP2 … pro …] &]]] |

In (23) the pivot NP1 is base-generated only in the first conjunct TP1 and assigned Case from the first conjunct predicate. In the second conjunct TP2, the superficially missing argument is pro, which does not care about the morphological Case of its antecedent, i.e., the pivot.[9] In short, this asymmetric scrambling-plus-pro analysis would be more favorable than the symmetric analyses to explaining the acceptable instances of Case-mismatches in Korean LNR.

4.2 Case type of a pivot

Our second finding was that while the preference for the first conjunct as the Case-licensing locus of pivots was maintained regardless of Case types, Case-mismatched dative pivots were more acceptable than Case-mismatched accusative pivots: (12a) > (12b). This finding may be addressed from the perspective of processing since a perception of acceptability was maintained in (12a) and (12b). In order to account for the difference of acceptability ratings between dative pivots and accusative pivots in LNR, it is reasonable to speculate, therefore, that the difference between (12a) and (12b) is not categorical but gradable in nature. Below, to evaluate the impact of the scrambled pivot on the processing and acceptability of LNRed sentences, we resort to the syntactic and semantic complexity of the filler-phrase.

Syntactically, it has been generally assumed that (24b) and (24c) involve a movement (i.e., scrambling) of an object to the clause-initial position (Miyagawa 2001; Saito 1985). We stress that scrambling does not influence the propositional meaning in (24) (Saito 1985):

| John-i | Mary-eykey | ton-ul | cwuessta. |

| John-Nom | Mary-Dat | money-Acc | gave |

| ‘John gave money to Mary.’ | |||

| Mary-eykey | John-i | ton-ul | cwuessta. |

| Mary-Dat | John-Nom | money-Acc | gave |

| ‘To Mary, John gave money.’ | |||

| Ton-ul | John-i | Mary-eykey | cwuessta. | |

| money-Acc | John-Nom | Mary-Dat | gave | |

| ‘Money, John gave to Mary.’ | ||||

In sentence processing, however, several studies on various languages have proved that the processing cost of scrambled word order is higher than that of canonical word order: German (Weyerts et al. 2002), Russian (Sekerina 2003), etc.

There are several explanations for this difference. One possible explanation is that complex structures require heavier processing costs than simple structures do. For example, according to Gibson (1998), processing non-canonical structures requires greater memory resources than processing canonical structures because the former is associated with higher reading times and is therefore more difficult to process. Notice that scrambled phrases may form a sort of filler-gap dependency with gaps. We thus assume that the pivot, fronted via scrambling, constitutes a filler-gap dependency with each gap in LNRed constructions. Under this explanation, the cause of difficulty for scrambling is related to working memory resources.

The difficulty of processing filler-gap dependencies depends not only on the length of the dependency (cf. Alexopoulou and Keller 2007), but also on the property of the filler itself. As an illustration, Hofmeister (2011) proves that complex filler-phrases turn out to facilitate processing at retrieval points. For example, the clefted indefinite in (25b), which is syntactically and semantically more complex than that in (25a), were found to produce faster reading times around the subcategorizing verb banned:

| It was a communist who the members of the club banned from ever entering the premises. |

| It was an alleged Venezuelan communist who the members of the club banned from ever entering the premises. (Hofmeister 2011: 385) |

To account for this pattern, Hofmeister (2011) argues that linguistic expressions with more syntactic and semantic features contribute to retrieval process in language comprehension, owing to increased activation and resistance to interference. This contribution ultimately leads to increasing acceptability.

Although it is beyond the scope of this paper to make precise the explanation of the processing cost of scrambling in Korean LNR, we speculate that the processing cost of scrambling in LNR can be alleviated by the degree of filler complexity. Assuming that the dative marker eykey (‘to’ or ‘toward’) is semantically and syntactically more complex (in that it behaves like a postposition) than the structural accusative marker (l)ul, we suggest that the processing cost of LNRed accusative pivot is higher than that of LNRed dative pivot due to the filler complexity of the latter.[10] To put it differently, we suggest that the complexity of the pivot under the filler-gap dependency in LNR may lower processing cost because the complex filler is easier to retrieve at the site of the gap and this leads to the amelioration in acceptability in (12a) in relation to (12b). To the extent that acceptability is partly derived in terms of processing difficulty, the observed contrast caused by the complexity of the LNRed pivot may play a key role in the perception of the acceptability of the entire sentence. In addition, the increase in acceptability is uniform between dative pivot conditions and accusative pivot conditions: (12a) > (12b) and (12c) > (12d).

Summing up, at the point of the gap site, complex fillers are easier to access and then integrate into the existing structure. We suggest that processing factors have the potential to account for this otherwise unexplained variation in acceptability judgments.

4.3 Dependent plural marking of a pivot

As mentioned before, Nakao (2010) briefly explores to reformulate her ATB scrambling analysis of Japanese LNR from the perspective from Citko’s (2005) multidominance proposal. According to Nakao’s multidominance reanalysis of LNR, the pivot is parallelly merged with the predicate in each conjunct, capturing the Case-matching requirement. In this analysis, the pivot must move to a higher position for linearization, obeying Kayne’s (1994) LCA. This perspective is echoed in Chung (2010), except that the movement of LNRed pivots is forced by Wilder’s (1999, 2008 version of the LCA. Departing from Citko (2005), Chung argues that multidominated elements do not necessarily leave their base position, establishing a derivational connection between RNR as in (26) and LNR as in (27).

| [RNR | +DPM] (= 13b) | ||||||||||||

| John-i | TOEFL-ul, | Mary-ka | TOEIC-ul, | yelsimhi-tul | kongpwuhayssta. | |||||||

| J-Nom | TOEFL-Acc | M-Nom | TOEIC-Acc | diligently-DPM | studied | |||||||

| ‘John (studied) TOEFL (diligently), and Mary studied TOEIC diligently.’ | ||||||||||||

| [LNR | +DPM] (= 13d) | ||||

| Yelsimhi-tul, | John-i | TOEFL-ul | kaluchi-ko, | |

| diligently-DPM | J-Nom | TOEFL-Acc | teach-and | |

| Mary-ka | TOEIC-ul | kongpwuhayssta. | ||

| M-Nom | TOEIC-Acc | studied | ||

| ‘Diligently, John taught TOEFL, and Mary studied TOEIC.’ | ||||

The derivations are represented in (28), respectively:

| RNR |

|

| LNR |

|

In (28a) the multidominated pivot VP ‘diligently-DPM studied’ remains in-situ, which would provoke a contradiction in linearization under Kayne’s (1994) LCA; since the pivot is dominated by both conjuncts, it has to precede itself, violating reflexivity. Chung, however, argues that there arises no linearization problem under Wilder’s (1999, 2008) LCA, according to which an in-situ pivot gets linearized at the right-edge of the conjuncts, deriving an RNR construction as in (26). According to Chung, moving out of the conjunct involving multidominance is an alternative way to deal with the linearization problem, which is employed in LNR constructions, as shown in (28b); the multidominated pivot yelsimhi-tul ‘diligently-DPM’ moves leftward out of the coordination structure.

Chung (2010) argues that the multidominance analysis has an advantage over the ATB scrambling analysis; it can accommodate the distribution of DPM as well as the Case-matching requirement. Based on Choe’s (1988) observation, he points out that the DPM tul, which is licensed by a c-commanding plural antecedent in the local domain, is licensed in both RNR (Chung 2004) and LNR even when the subject of each conjunct is singular as in (26) and (27), respectively. According to Chung, the well-formedness of such constructions can be explained via multidominance; the two singular subjects in the two conjuncts simultaneously c-command and license the pivot, collectively functioning as a plural antecedent.

However, as attested by Experiment 2, there is an acceptability contrast between RNR and LNR involving the DPM. The LNR construction in (27) is much worse than the RNR construction in (26), which raises an empirical question of whether the DPMed pivot in RNR and LNR is licensed in the same way. Recall that (28a) is acceptable according to the results of Experiment 2. Thus, the RNRed DPM can be licensed under the multidominance proposal in that its in-situ position is co-c-commanded by the split antecedents John and Mary. However, since (28b) is predicted to be acceptable under the multidominance proposal, the experimental result of the DPMed pivot in LNR is not compatible with Chung’s (2010) multidominance analysis.

Instead, the unacceptability of (28b) is predicted by the current scrambling-plus-pro analysis, as shown in (29).

| *[diligently-DPM1]pivot | John-Nom | t1 | TOEFL-Acc | teach-and | |

| Mary-Nom proTOEIC-Acc studied | |||||

Under the scrambling-plus-pro analysis, there is no chance of the DPMed pivot to be c-commanded by a (split) plural subject. In short, the unacceptable status of the DPMed pivot could be evidence of the scrambling-plus-pro analysis, but not of the multidominance analysis.[11]

5 Conclusion

In this paper, certain aspects of Korean left-node-raising (LNR) were examined via acceptability judgment experiments. We found that some Case-mismatches in Korean LNR were not as unacceptable as previously thought, and that the congruence between the pivot’s morphological Case and the Case assigned by the first conjunct predicate is crucial. This suggests that the Case-mismatch of LNRed pivots may be tolerated once their Case is licensed in the first conjunct. Also, the Case-mismatch in LNR was more acceptable when the Case of the pivot was dative than when it was accusative. Taken together, the current study poses a tough question to the symmetric analyses of LNR (Chung 2010; Nakao 2009, 2010) which take the Case-match requirement of LNRed objects as decisive evidence.

As a consequence, we provided evidence that the dative marker in Korean is different from the accusative marker, which is a typical structural Case maker, in that its semantic import as a postposition facilitates the processing of filler-gap dependency with a dative filler relative to an accusative filler. This evidence is in accord with the view that the complexity of fillers facilitates the processing of filler-gap dependencies (Hofmeister 2011).

In addition, the effect caused by the complexity of the LNRed pivot under filler-gap dependencies is uniform across both acceptable and unacceptable cases. The combined results thus steer us toward the view that the sensitivity to Case-type of pivots is due to a processing facilitation driven by filler-complexity and the first-conjunct-sensitivity effect is due to a grammatical principle such as Case theory. The results here suggest that these two effects may combine additively.

We also attested that the dependent plural marker (DPM) tul within the pivot decreases acceptability in LNR but not in right-node-raising (RNR) and thus showed that LNR is not a mirror image of RNR (contra Chung 2010; Nakao 2009, 2010; Yatabe 2001). In particular, we argued that the DPM within the pivot supports the scrambling-plus-pro analysis of LNR.

Overall, the findings of the experiments would contribute to articulating and developing further studies in Japanese/Korean LNR.

References

Abe, Jun & Chizuru Nakao. 2009. On ATB movement and parasitic gaps in Japanese. In 2009 visions of the minimalist program, proceedings of the 11th Seoul international conference on generative grammar, 1–15.Search in Google Scholar

Alexopoulou, Theora & Frank Keller. 2007. Locality, cyclicity, and resumption: At the interface between the grammar and the human sentence processor. Language 83(1). 110–160. https://doi.org/10.1353/lan.2007.0001.Search in Google Scholar

Baayen, Rolf H., Doug J. Davidson & Douglas M. Bates. 2008. Mixed-effects modeling with crossed random effects for subjects and items. Journal of Memory and Language 59(4). 390–412. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jml.2007.12.005.Search in Google Scholar

Barr, Dale J., Roger Levy, Christoph Scheepers & Harry J. Tily. 2013. Random effects structure for confirmatory hypothesis testing: Keep it maximal. Journal of Memory and Language 68(3). 255–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jml.2012.11.001.Search in Google Scholar

Bates, Douglas, Martin Machler, Benjamin M. Bolker & Steven C. Walker. 2015. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software 67(1). 1–48. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v067.i01.Search in Google Scholar

Boeckx, Cedric. 2008. Bare syntax. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Bošković, Željko. 2020. On the coordinate structure constraint, across-the-board-movement, phases, and labeling. In Jeroen van Craenenbroeck, Cora Pots & Tanja Temmerman (eds.), Recent developments in phase theory, 133–182. Berlin & Boston: Walter de Gruyter.10.1515/9781501510199-006Search in Google Scholar

Caha, Pavel. 2009. The nanosyntax of case. Tromsø, Norway: University of Tromsø dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Choe, Hyon Sook. 1988. Restructuring parameters and complex predicates: A transformational approach. Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Chomsky Noam. 1986. Knowledge of language: Its nature, origin, and use. New York, NY: Praeger.Search in Google Scholar

Chomsky Noam. 1995. The minimalist program. Cambridge MA: MIT Press.Search in Google Scholar

Chung, Daeho. 2004. A multiple dominance analysis of right node sharing constructions. Language Research 40(4). 791–811.Search in Google Scholar

Chung, Daeho. 2010. Left Node Raising as a shared node raising. Studies on Generative Grammar 20(1). 549–576.10.15860/sigg.20.1.201002.51Search in Google Scholar

Citko, Barbara. 2003. ATB wh-movement and the nature of Merge. In Makoto Kadowaki & Shigeto Kawahara (eds.), Proceedings of the 33th annual meeting of the North East Linguistic Society, 87–102. Charleston, SC: BookSurge Publishing.Search in Google Scholar

Citko, Barbara. 2005. On the nature of merge: External merge, internal merge, and parallel merge. Linguistic Inquiry 36(4). 475–496. https://doi.org/10.1162/002438905774464331.Search in Google Scholar

Drummond, Alex. 2016. Ibex farm. Available at: https://github.com/addrummond/ibexfarm.Search in Google Scholar

Dyła, Stefan. 1984. Across the board dependencies and Case in Polish. Linguistic Inquiry 15(4). 701–705.Search in Google Scholar

Franks, Steven. 1993. On parallelism in across-the-board dependencies. Linguistic Inquiry 24(3). 509–529.Search in Google Scholar

Gibson, Edward. 1998. Linguistic complexity: Locality of syntactic dependencies. Cognition 68. 1–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0010-0277(98)00034-1.Search in Google Scholar

Hofmeister, Philip. 2011. Representational complexity and memory retrieval in language comprehension. Language & Cognitive Processes 26(3). 376–405. https://doi.org/10.1080/01690965.2010.492642.Search in Google Scholar

Ishii, Yasuo. 1991. Operators and empty categories in Japanese. Storrs, CT: University of Connecticut dissertation.10.1515/jjl-1991-0113Search in Google Scholar

Kayne, Richard. 1994. The antisymmetry of syntax. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.Search in Google Scholar

Kim, Jeong-Seok. 2019. Sayngnyakkwa chocem: Swuyongseng phantanul cwungsimulo [Ellipsis and focus: With special reference to acceptability judgment]. Seoul: Hankook Publishing.Search in Google Scholar

Kim, Jeong-Seok, Duk-Ho Jung & Yunhui Kim. 2020. Case-mismatches in Korean left-node-raising: An experimental study. Linguistic Research 37(3). 499–529.Search in Google Scholar

Kuznetsova, Alexandra, Per B. Brockhoff & Rune H. B. Christensen. 2017. LmerTest package: Tests in linear mixed effects models. Journal of Statistical Software 82(13). 1–26. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v082.i13.Search in Google Scholar

Lenth, Russell. 2018. Emmeans: Estimated marginal means, aka least-squares means R package version 1.2.4. Available at: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=emmeans.10.32614/CRAN.package.emmeansSearch in Google Scholar

Marušič, Franc Lanko & Rok Žaucer. 2017. Coordinate structure constraint: A-/A’-movement vs. clitic movement. Linguistica Brunensia 65(2). 69–85.Search in Google Scholar

McCloskey, James. 2006. Resumption. In Martin Everaert & Henk van Riemsdijk (eds.), The Blackwell companion to syntax Volume 1, 94–117. Oxford: Blackwell.10.1002/9780470996591.ch55Search in Google Scholar

Miyagawa, Shigeru. 2001. The EPP, scrambling, and wh-in-situ. In Michael Kenstowicz (ed.), Ken Hale: A life in language, 293–338. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.10.7551/mitpress/4056.003.0012Search in Google Scholar

Munn, Alan. 1993. Topics in the syntax and semantics of coordinate structures. College Park, MD: University of Maryland dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Nakao, Chizuru. 2009. Island repair and non-repair by PF strategies. College Park, MD: University of Maryland dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Nakao, Chizuru. 2010. Japanese left node raising as ATB scrambling. Proceedings of the 33rd Annual Penn Linguistics Colloquium, U. Penn Working Papers in Linguistics 16(1). 156–165.Search in Google Scholar

Park, Myung-Kwan & Wooseung Lee. 2009. A ‘RNR’ analysis of ‘left node raising’ constructions in Korean. Studies in Generative Grammar 19(4). 505–528. https://doi.org/10.15860/sigg.19.4.200911.505.Search in Google Scholar

R Core Team. 2020. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available at: https://www.r-project.org.Search in Google Scholar

Ross, John R. 1967. Constraints on variables in syntax. Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Saito, Mamoru. 1985. Some asymmetries in Japanese and their theoretical implications. Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Schütze, Carson T. & Jon Sprouse. 2013. Judgment data. In Robert J. Podesva & Devyani Sharma (eds.), Research methods in linguistics, 27–50. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9781139013734.004Search in Google Scholar

Sekerina, Irina A. 2003. Scrambling and processing: Dependencies, complexity and constraints. In Simin Karimi (ed.), Word order and scrambling, 301–324. Malden, MA: Blackwell.10.1002/9780470758403.ch13Search in Google Scholar

Sprouse, Jon, Troy Messick & Jonathan David Bobaljik. 2022. Gender asymmetries in ellipsis: An experimental comparison of markedness and frequency accounts in English. Journal of Linguistics 58. 345–379. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0022226721000323.Search in Google Scholar

Weyerts, Helga, Martina Penke, Thomas F. Münte, Hans-Jochen Heinze & Harald Clahsen. 2002. Word order in sentence processing: An experimental study of verb placement in German. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research 31(3). 211–268. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1015588012457.10.1023/A:1015588012457Search in Google Scholar

Wilder, Chris. 1999. Right node raising and the LCA. In Sonya F. Bird, Andrew Carnie, Jason D. Haugen & Peter Norquest (eds.), Proceedings of the 18th West Coast Conference on formal linguistics, 586–598. Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Proceedings Project.Search in Google Scholar

Wilder, Chris. 2008. Shared constituents and linearization. In Kyle Johnson (ed.), Topics in ellipsis, 229–258. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511487033.010Search in Google Scholar

Yatabe, Shuichi. 2001. The syntax and semantics of left-node raising in Japanese. In Dan Flickinger & Andreas Kathol (eds.), Proceedings of the 7th international conference on head-driven phrase structure grammar, 325–344. Stanford, CA: CSLI Publications.10.21248/hpsg.2000.19Search in Google Scholar

© 2022 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Production of vowel reduction by Jordanian–Arabic speakers of English: an acoustic study

- The linguistic realization of focus in Uyghur: can the two focusing strategies be used interchangeably?

- Thematic role mappings in metaphor variation: contrasting English bake and Spanish hornear

- A probability distribution of dependencies in interlanguage

- Croatian (mor)phonotactic word-medial consonant clusters in the early lexicon

- The impact of gestural representation of metaphor schema on metaphor comprehension

- Licensing Case-mismatches and dependent plural markers in Korean left-node-raising

- Mandarin Chinese peer advice online: a study of gender disparity

- The pragmatics of ‘it is well’ in Nigerian English

- Active verbs with inanimate, text-denoting subjects in Polish and English abstracts of research articles in linguistics

- Book Reviews

- Book review. Melissa Yoong. 2020. Professional discourses, gender and identity in women’s media. Springer Nature Switzerland. 149pp. 49.99€, ISBN 978-3-030-55543-6.

- The status, roles, and dynamics of Englishes in Asia

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Production of vowel reduction by Jordanian–Arabic speakers of English: an acoustic study

- The linguistic realization of focus in Uyghur: can the two focusing strategies be used interchangeably?

- Thematic role mappings in metaphor variation: contrasting English bake and Spanish hornear

- A probability distribution of dependencies in interlanguage

- Croatian (mor)phonotactic word-medial consonant clusters in the early lexicon

- The impact of gestural representation of metaphor schema on metaphor comprehension

- Licensing Case-mismatches and dependent plural markers in Korean left-node-raising

- Mandarin Chinese peer advice online: a study of gender disparity

- The pragmatics of ‘it is well’ in Nigerian English

- Active verbs with inanimate, text-denoting subjects in Polish and English abstracts of research articles in linguistics

- Book Reviews

- Book review. Melissa Yoong. 2020. Professional discourses, gender and identity in women’s media. Springer Nature Switzerland. 149pp. 49.99€, ISBN 978-3-030-55543-6.

- The status, roles, and dynamics of Englishes in Asia