Abstract

The focus of the present study is the relation between metaphor and aspect: are certain grammatical forms more prone to be used metaphorically? We approach this issue through a puzzling case of Russian aspectual triplets. The study is based on the distributions of the unprefixed imperfective verb gruzit’ (IPFV1) ‘load’, its perfective counterparts (PFVs) and prefixed secondary imperfectives (IPFV2s) with the prefixes na-, za-, and po-. The data collected from the Russian National Corpus offers support for the Telicity Hypothesis according to which IPFV2s become more “oriented towards a result” due to the presence of a prefix. We show that, although characterized by similar semantics, all verbs in a triplet have different distributions among constructions and metaphorical patterns. The difference is particularly noticeable in metaphorical contexts, where IPFV2s have a higher frequency of metaphorical uses. The prefix seems to play a more crucial role than aspect as metaphorical patterns of IPFV2s are more similar to the patterns attested for the perfective counterparts. Based on this study, we can assume that the resultative state more often serves as a source for conventional verbal metaphors than the process itself, which results in IPFV2s being more often used metaphorically than IPFV1.

1 Introduction

Recent studies have paid special attention to formal representations of metaphorical uses as opposed to literal ones. Deignan (2005) and Steen (2007) argue that certain parts of speech (particularly verbs and adjectives) are more prone to having metaphorical meanings. Deignan’s study of nouns denoting animals and their mappings onto human characteristics shows that derived adjectival forms like foxy and kittenish or the verbal forms of fox (foxes, foxing, foxed) are commonly not attested for the source domain units and are used only metaphorically (Deignan 2005: 153-154). Sokolova (2013) examines the formal differences between metaphorical and literal uses on a small family of closely related constructions, the Locative Alternation constructions, some of which are the focus of the present article. The corpus data from Russian reveal that certain Locative Alternation constructions are more often instantiated as metaphorical extensions than others. Finally, Sullivan (2013) presents a systematic overview of the basic English constructions (adjective constructions, argument structure constructions, preposition phrases and certain constructions beyond the clause) that can have metaphorical extensions. Although the book does not offer a quantitative study, the corpus data analyzed by Sullivan suggest a strong association between particular grammatical constructions and their role in metaphorical language.

The present article continues this discussion and explores the association that certain grammatical forms and constructions have on metaphor. The major focus is the relation between metaphor and aspect, which is analyzed through a case study of Russian aspectual triplets. In Russian, a perfective verb and two imperfectives, all related via word-formation, can share approximately the “same” lexical meaning goret’-IPFV – s-goret’-PFV – sgor-a-t’-IPFV ‘burn’). In this case we have an aspectual triplet consisting of a primary imperfective (IPFV1), a perfective, and a secondary imperfective (IPFV2) (Apresjan 1995; Zaliznjak and Mikaèljan 2010). Some of the questions that have been puzzling scholars in connection with aspectual triplets are: how the argument structures of the three forms in an aspectual triplet are related, and why the system allows for two imperfectives that on the surface function as equivalents (see Kuznetsova and Sokolova 2016 for an overview).

The data presented in this article show that, although characterized by similar semantics, all three verbs in a triplet tend to be used with different constructions. Since the two imperfectives in a triplet have been treated as very close synonyms (see Evgen’eva 1999; Ožegov and Švedova 2001; and the literature overview in Section 2.2) the major focus is set on their functional-semantic division of labour (in the sense of Radden and Panther 2004). This approach goes in line with other studies on variation within syntactic constructions (e.g. Goldberg 1995; Gries and Stefanowitsch 2004, etc.) and morphological variation (Janda and Lyashevskaya 2011b; Janda et al. 2013b). The difference among paired imperfectives is particularly noticeable in metaphorical contexts, where IPFV2 has a higher frequency of metaphorical uses than IPFV1. Due to the presence of a prefix, IPFV2s become more telic, or “oriented towards a result” (Veyrenc 1980; Kuznetsova and Sokolova 2016), and are used in constructions that are typical of prefixed perfective verbs. This is one of the first studies that analyzes aspectual triplets in terms of their metaphorical extensions. The article thus concentrates on differentiation of the three verbs in a triplet in metaphorical uses and leaves aside the discussion of cases of attraction between competing forms (see De Smet et al. 2018; and Fonteyn and Maekelberghe 2018 for more detail).

In order to corroborate this claim, the article presents a corpus analysis of the verb ‘load’ (based on Russian National Corpus, RNC: www.ruscorpora.ru), which has IPFV1 gruzit’, three perfective counterparts nagruzit’, zagruzit’, pogruzit’ and three IPFV2: nagružat’, zagružat’, pogružat’, with the prefixes na-, za-, and po- respectively. All the ‘load’ verbs show alternation between the two constructions, the Theme-Object (‘load the hay onto the truck’) and the Goal-Object (‘load the truck with hay’), which can have metaphorical extensions (for instance, ‘load somebody with information’).

This article is structured as follows. In Section 2, we present an overview of the Russian aspectual system and the relation between Russian aspect, verbal constructions and verbal prefixes. First the relevant terminology, such as aspectual pairs (2.1) and aspectual triplets (2.2), is introduced, followed by a brief overview of the main semantics of the three verbal prefixes relevant for this study, namely na-, za-, and po-. In Section 3, we present our hypothesis on how the constructional profiles of the three forms (IPFV1, PFV, and IPFV2) in an aspectual triplet are related. The data is described in Section 4, the results of the corpus study are offered in Section 5. Here we compare the members of the ‘load’ triplets in terms of constructions (5.1) and metaphorical uses (5.2) and then summarize the section with a detailed analysis of metaphorical patterns attested for IPFV1, PFV, and IPFV2 (5.3). Conclusions are offered in Section 6.

2 The puzzle of Russian aspect

In this section we present a general overview of Russian aspect and discuss two major notions, aspectual pair and aspectual triplet. Aspectual triplets present a puzzle for the aspectual system since on the surface it should be built upon a binary opposition.

2.1 Russian Paired IPFVs and PFVs

Traditionally in Russian linguistics, an imperfective verb and a perfective verb that share the same root and the same lexical meaning are said to constitute an aspectual pair (see Švedova et al. 1980; Čertkova 1996; Zaliznjak and Šmelev 2000). In Slavic languages the perfective aspect is characterized by telicity, i.e. “the presence of a limit or end-state for the process” (Bybee and Dahl 1989: 87–88). In the development of Russian aspect, telicity is associated with verbal prefixes (Dickey 2012). The secondary imperfective contains a prefix and in general is opposed to the primary imperfective in terms of telicity (for further discussion see Kuznetsova and Sokolova 2016 and Section 3 below).

The notion of an aspectual pair can be called a “central notion in [Russian] aspectology” (Čertkova 1996: 110). Perfective and imperfective verbs are related morphologically. Most simplex unprefixed verbs are imperfective, e.g., pisat’ ‘write-IPFV’. With regard to the form, the perfective verb is a combination of a prefix and the imperfective base, e.g., napisat’ ‘write-PFV’. A secondary imperfective can be seen as a combination of the prefix, an imperfective base, and an imperfectivizing suffix, e.g., perepisat’ ‘re-write-PFV’ – perepisyvat’ ‘rewrite-IPFV’. Thus, morphologically, Russian has two types of imperfective verbs: unprefixed simplex verbs, or “primary imperfectives”, and prefixed verbs with an imperfectivizing suffix, or “secondary imperfectives” (Švedova et al. 1980). We use the abbreviations IPFV1 and IPFV2 to refer to these two types of verbs. Subsequently, there are two types of aspectual pairs: pairs that consist of a perfective and a primary imperfective and pairs that consist of a perfective and a secondary imperfective, as presented in Table 1.

Morphological types of Russian aspectual pairs.

| Imperfective | Perfective | |

|---|---|---|

| Primary imperfective (IPFV1) | pisat’ ‘write’ | na pisat’ ‘write’ |

| Secondary imperfective (IPFV2) | perepisyvat’ ‘rewrite’ | perepisat’ ‘rewrite’ |

Aspectual pairs that consist of a perfective and a secondary imperfective are traditionally considered prototypical (Isačenko 1960: 130–175; Kasevič 1977: 77–78; Glovinskaya 2001: 55; Percov 2001: 120, 125; Timberlake 2004; Plungian 2011: 409). Pairs that consist of a perfective and a primary imperfective often are problematic, because several perfectives with different prefixes can be related to the same simplex imperfective. However, most traditional analyses (Vinogradov 1947; Šaxmatov 1952; Švedova 1980; Čertkova 1996; Anna Zaliznjak and Šmelev 2000) and practically all dictionaries and textbooks accept both kinds of pairs (see the discussion in Janda and Lyashevskaya 2011a).

In addition to morphological criteria, researchers in Russian linguistics have proposed several diagnostic contexts in which a perfective verb and an imperfective verb that form an aspectual pair show complementary distribution. The most important context is a criterion proposed by Maslov (1984), which states that in a sequence of past actions, we should be able to replace the perfective verb used in the past tense by the imperfective verb in praesens historicum:

Past tense (PFV):

On ot rasterjannosti okamenel, i ona tože zastyla licom (Ju. Trifonov)

‘He was petrified with perplexity and her face also froze.’

Praesens historicum (IPFV):

I vot on ot rasterjannosti kameneet, i ona tože zastyvaet licom

‘And so he is petrified with perplexity and her face also freezes.’

Another diagnostic context is the use of the imperative. In Russian, perfective imperatives change their aspect to imperfective when negated:

Positive imperative (PFV):

Pozvoni žene.

‘Call your wife.’

Imperative with negation (IPFV):

Ne zvoni žene.

‘Don’t call your wife.’

Paired IPFV and PFV are believed to share similar constructional profiles (see discussion in Berdičevskis and Eckhoff 2014; Kuznetsova 2015). All the ‘load’ verbs that are considered in this study can potentially be used in the same constructions [1] (see Sections 4 and 5.1 for detail). However, when presenting constructions, the degree of granularity becomes crucial as the same construction might have different metaphorical extensions depending on the semantics of the nouns that fill the construction slots and a broader context. In this article we place major focus on metaphorical extensions.

2.2 Aspectual triplets

As shown in Section 2.1, we can classify aspectual pairs into two different types: (1) a base imperfective verb with its perfective counterpart formed via prefixation (pisat’-IPFV ‘write’ – napisat’-PFV) and (2) a specialized perfective and its secondary imperfective formed via suffixation (perepisat’ ‘rewrite-PFV’ – perepisyvat’ ‘rewrite-IPFV’). However, a given perfective counterpart can have two corresponding imperfectives: the base imperfective (IPFV1) and the secondary imperfective (IPFV2), thus forming an aspectual triplet (Veyrenc 1980; Apresjan 1995; Petruxina 2000; Jasai 2001; Xrakovskij 2005; Zaliznjak and Mikaèljan 2010; Kuznetsova and Sokolova 2016; Nordrum 2017; Kozera 2018). Examples of Russian aspectual triplets are offered in Table 5.

Examples of Russian aspectual triplets.

| Primary Imperfective (IPFV 1) | Perfective | Secondary Imperfective (IPFV 2) | Gloss |

|---|---|---|---|

| žarit’-IPFV | za-žarit’-PFV | za-žar-iva-t’-IPFV | ‘fry’ |

| goret’-IPFV | s-goret’-PFV | s-gor-a-t’-IPFV | ‘burn’ |

If one assumes that the Russian aspectual system is based on aspectual pairs, the existence of aspectual triplets appears to be surprising, as has been pointed out in a number of works (Apresjan 1995; Petruxina 2000; and others). Why does the system allow for two IPFVs that are expected to function as equivalents? Can we say that “two is a company, and three is a crowd”? Before we present our hypothesis and proceed with the analysis, it is important to provide a brief overview of the prefixes that will be considered in this study.

2.3 Aspectual prefixes na-, za-, and po-

The prefixes na-, za-, and po- were selected for this study as only the load verbs with these prefixes are in a triplet relation with the simplex verb gruzit’ ‘load’. The information has been culled from dictionaries like Evgen’eva 1999 and Ožegov and Švedova 2001 and described in detail in Janda et al. (2013a) (see also the webpage of the project [2]). The verb gruzit’ ‘load’ can be combined with other prefixes, like pere-, but in such cases a different lexical meaning is produced, which is reflected in the gloss: peregruzit’-PFV and peregružat’-IPFV acquire the meaning ‘reload, overload’ and thus cannot be in a triplet relation with the verb gruzit’ ‘load’.

Janda et al. (2013a) have shown that Russian verbal prefixes always express meaning, even when they are used to form the perfective partners of aspectual pairs. The semantics of the aspectual prefix in an aspectual pair overlaps with the semantics of the verbal stem, which makes the semantics of the prefix less noticeable on the surface (hence the imperfective and the perfective verb in the pair retain relatively similar semantics). Since the semantics of the prefix in aspectual pairs is preserved, the same should be true for aspectual triplets (where the IPFV1, PFV, and IPFV2, in general, share the same gloss). Thus, for a more elaborate analysis of the ‘load’ aspectual triplets a short overview of the prefixes na-, za-, and po- is essential. For the examples considered in this study the prototypical, or central, meaning of the prefix is particularly relevant. While the radial categories for za- and po-have been explored in some cognitive studies (Janda 1986; Shull 2003; Sokolova and Endresen 2017 on za-; LeBlanc 2010 on po-), comprehensive studies of na- are mostly found within atomistic and structural tradition. [3]

The Semantics of the Prefix na-. In the atomistic tradition, as in Švedova et al. (1980), the semantics of na- is represented via spatial (‘direct an action on the surface of something’: naexat’ ‘drive on(to)-PFV’, nakleit’ ‘stick/attach-PFV’), resultative (napugat’ ‘scare-PFV’; nagret’ ‘heat-PFV’) and various cumulative/quantitative meanings like accumulation of objects: (nalovit’ ryby ‘to catch a lot of fish-PFV’ from lovit’ ‘catch-IPFV’) and accumulation of events (intensive activity): (nagrešit’ ‘sin a lot’ from grešit’ ‘sin-IPFV’). In a structural model, proposed by Russell (1985), the prefix na- minimally contains two notions: locus and quantity. Under this analysis, locus and quantity are regarded as extremes on a scale. There can be varying degrees of locative or quantitative meaning present in different verb stems and syntactic combinations.

In a relatively recent study, Janda and Lyashevskaya (2013) analyze the semantics of the prefix na- by means of semantic profiling that shows which semantic classes of verbs [4] the prefix is attracted to and repelled from. According to their findings, the semantic profile of na- is more diffuse than for the other prefixes, since it lacks the focus of having one strongly attracted semantic class. The two semantic classes that na- is almost equally attracted to are IMPACT (verbs like navoščit’ ‘wax’ and namylit’(sja) ‘soap’) and BEHAVIOR (nabezobrazničat’ ‘behave disgracefully’ and naxuliganit’ ‘behave like a hooligan’).

To sum up, we can conclude that the most salient meanings of na- appear to be related to SURFACE or ACCUMULATION.

The Semantics of the Prefix za-. In the literature the prefix za- has been called “the most varied” (Keller 1992: 35), “versatile and difficult” (Townsend 2008: 124) of the Russian prefixes (see also Sokolova and Endresen 2017). Without enumerating all possible meanings of the prefix za-, we will focus on the central ones that have often been discussed in relation with the radial category of this prefix.

Different authors propose different semantic candidates for the prototype of the prefix za-: DEVIATION (Janda 1985: 27); BEHIND (Shull 2003); COVER / BEHIND (Sokolova and Endresen 2017). According to Janda (1985), the central configuration (or spatial image-schema) for za- can be described in terms of the trajector transgressing the boundary of the landmark and passing into the area outside the landmark. Janda lists DEVIATION (or “deflection”) as the first meaning within the central configuration, illustrated in (3).

Zajti v magazin po puti domoj

za-walk in store-ACC on way-DAT home

‘Stop by a store on the way home.’

According to Shull, deviation (or “deviance”) together with other meanings of za- is “the result of the experiential correlation of objects going behind/beyond landmarks with losing sight of and access to those objects” (Shull 2003:194); see example (4).

Mal’čik zašel za dom.

Boy-NOM za-walked behind house-ACC

‘The boy walked (to) behind the house.’ (Shull 2003: 194)

Sokolova and Endresen (2017) suggest a “double” prototype for za-, namely COVER / BEHIND. This double prototype is based on the notion of construal (Langacker 1987, 1999: 206): depending on the semantics of the simplex verbal stem, the prefix za- can realize either one or the other side of its “double” schema, i.e. COVER or BEHIND. Examples (5) and (6) below make this idea explicit with the word ščit ‘shield’.

zakryt’sja ščitom

cover-self shield-INS

‘cover oneself with a shield’

zaiti za ščit

za-walk behind shield-ACC

‘walk behind the shield/board’

Both expressions involve a motion after which the object is covered with a shield. However, in the first case ščit ‘shield’ represents a trajector (movable object), whereas in the second case ščit ‘shield/board’ is a landmark (with the moving person being a trajector).

Since the meaning DEVIATION is restricted to verbs of motion (see Sokolova and Endresen 2017), the relevant meanings for this study are COVER and BEHIND.

The Semantics of the Prefix po-. Lexicographers and grammarians assigned po- between three and nine meanings or even more if one counts the sub-contexts. A comprehensive overview is offered in (LeBlanc 2010), which presents a statistical study of the verbs prefixed in po- from the RNC. For perfective verbs, LeBlanc identifies the following meanings of po-: resultative (e.g. postroit’ ‘build’), delimitative (e.g. postojat’ ‘stand for a while’), attenuative (e.g. poostyt’ ‘cool off somewhat’), [5] distributive (e.g. pobrosat’ ‘throw (distributively)’), and ingressive (e.g. poletet’ ‘(begin to) fly’).

LeBlanc (2010) concludes that the meanings of po- can be grouped into two clusters: Cluster one is comprised of the attenuative, delimitative, ingressive, and resultative meanings. Cluster two contains more peripheral meanings (e.g. distributive). He claims that the resultative meaning is prototypical and indicates that the subject has traversed the metaphorical PATH implied by the base verb in its entirety. The remaining meanings are metaphorical and metonymic extensions of that central meaning. This view of the semantics of po- coincides with what is known about the historical development of the prefix (see Dickey 2007).

Although according to some studies it remains unclear to which extent PATH is part of the semantics of the prefix (see Nesset 2008 on po- with verbs of motion), we will depart from LeBlanc’s proposal that the metaphorical PATH (reflected in the resultative meaning) can potentially be a salient semantic component of the prefix po-.

3 Hypothesis and predictions

This article provides further support for the Telicity Hypothesis introduced in (Veyrenc 1980) and specified in (Janda et al. 2013a; Kuznetsova and Sokolova 2016): “Primary imperfective denotes a process regarded without consideration of its result, whereas secondary imperfective denotes a process regarded with a consideration of its result” (Veyrenc 1980: 176). Due to the presence of a prefix, IPFV2s become more telic, or “oriented towards a result”.

On a more general level, the claim made by Veyrenc for Russian is reminiscent of other works that describe the semantics of aspectual forms using the notion BOUNDEDNESS (Langacker 1987; Talmy 2000, etc.): perfective processes are bounded in time and carry information about the beginning and end of an activity whereas imperfective processes are unbounded. IPFV2 presents a special case since it basically denotes a process, not temporally bounded in terms of (Croft 2012), but telic and potentially favoring bounded Themes (see the discussion in Section 5.1).

When discussing the difference in the semantics of IPFV1 and IPFV2, Veyrenc (1980) mentions several examples where we find a restriction on the metaphorical use of IPFV1:

Čem, bol’še muzykant oputan raznogo roda dogovorami i ob-

jazatel’stvami, tem trudnee emu vykraivat’-IPFV2/??kroit’-IPFV1 vremja dlja svobodnogo tvorčestva.

‘The more the musician is entangled with different sort of agreements and commitments, the harder it is for him to find time for creative work.’

The IPFV1 kroit’ literally means ‘cut into patterns/make patterns when sewing’. If we check the frequencies for IPFV1 and IPFV2, this observation would be rather striking as IPFV2 is selected in the metaphorical context even though the overall frequency of IPFV1 in the RNC is higher: 103 vs. 69 [6]. Veyrenc does not propose an explanation of the phenomenon, however, such restrictions can be interpreted in the following way: in a metaphorical context, we use not the process but the resultative state as a source domain for the metaphor, hence the preference for IPFV2 in the contexts like (7) above.

Departing from the Telicity Hypothesis we can make the following predictions:

Although characterized by similar semantics, all three verbs in a triplet are used with different constructions.

IPFV2s have a higher frequency of metaphorical uses than IPFV1s.

IPFV2 are used in metaphorical patterns that are typical of prefixed perfective verbs.

Taking Veyrenc’s observation into consideration, it would be interesting to examine a case where both IPFV1 and IPFV2 can have metaphorical uses and to verify whether IPFV2 is more susceptible to metaphor. The data presented in Section 5 below shows that IPFV1 and IPFV2 have different preferences in terms of metaphorical uses.

4 Data: Russian ‘load’ Verbs and Metaphorical Extensions

Janda et al. (2013a) and Kuznetsova and Sokolova (2016) show that there are roughly three groups of triplets: there are PFVs like vyrugat’ ‘curse’ that strongly prefer IPFV1, there are PFVs like zamolknut’ ‘shut up, fall silent’ that strongly prefer IPFV2, and there are PFVs that fall in between these two extremes. This article presents an analysis of the verb ‘load’, which has IPFV1 gruzit’, three perfective counterparts nagruzit’, zagruzit’, pogruzit’ and three IPFV2-s: nagružat’, zagružat’, pogružat’. The ‘load’ triplets belong to the last group: of all the attested imperfectives (IPFV1+IPFV2), secondary imperfectives (IPFV2) constitute 17.6% in the case of na-, 20.9% in the case of za-, and 46.8% in the case of po-.

Both IPFV1 and the three IPFV2s are characterized by a relatively high frequency in the RNC (see Table 6).

Competition between IPFV1 and IPFV2 in aspectual triplets of the ‘load’ verbs.

| Verb | Form | IPFV1 |

IPFV2 |

Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw | % | Raw | % | |||

| gruzit’/nagružat’ | IPFV1-IPFV2-na | 1537 | 82.4 | 328 | 17.6 | 1865 |

| gruzit’/zagružat’ | IPFV1-IPFV2-za | 1537 | 79.1 | 406 | 20.9 | 1943 |

| gruzit’/pogružat’ | IPFV1-IPFV2-po | 1537 | 53.2 | 720 | 46.8 | 2257 |

All the ‘load’ verbs show alternation between the two constructions, the Theme-Object and the Goal-Object constructions (terminology from Nichols 2008) illustrated by examples (8) and (9) below:

Theme-Object construction

gruzit’ seno-ACC na telegu-ACC

‘load the hay onto the truck’

The Goal-Object construction

gruzit’ telegu-ACC senom-INS

‘load the truck with hay’

Both constructions can have metaphorical extensions. For instance, human beings can serve as metaphorical containers for information that represents metaphorical contents (see example 10 below):

Ax, vam interesny podrobnosti iz žizni

oh you-DAT are-interesting particulars-NOM from life-GEN

zvezd? Radi boga, Andrej Maksimov “zagruzit”

pop-stars-GEN? For god Andrej Maksimov-NOM za-load-FUT

vas ètoj informaciej.

you-ACC this information-INS

‘Oh, you are interested in the details of the life of our pop stars? No problem, Andrej Maksimov will provide you with this information.’

We analyze the distribution of the two constructions using constructional profiling methodology (the frequency distribution of a given linguistic unit across syntactic environments, developed in Janda and Solovyev 2009) and take into account both literal uses and metaphorical extensions. We have culled all the examples of the ‘load’ verbs from the modern subcorpus (1950-2009) of the RNC, which contains 98 million words, and randomly selected only one example for each verb from any single author. For the secondary imperfectives (nagružat’, zagružat’, pogružat’) We have further reduced the number of examples by extracting 100 random attestations from the database. The passive forms were excluded from this study as they often reinforce the holistic effect associated with a construction and block some metaphorical patterns [7] (see Sokolova 2012 for details).

All examples have been manually coded for: the Locative Alternation constructions (Theme-Object vs. Goal-Object), metaphor (metaphorical vs. non-metaphorical), metaphorical pattern (the type of Theme and the type of Goal). For instance, the type of Theme in example (6) above is INFORMATION and the type of Goal is HUMAN, which gives the metaphorical pattern HUMAN+INFORMATION. Other types of Themes that are compatible with the Goal type HUMAN are PROBLEMS and WORK, which result in the metaphorical patterns HUMAN+ WORK and HUMAN+PROBLEMS. The metaphorical patterns are discussed in detail in Section 5.3 (see Table 9 for an overview).

Locative Alternation within the non-passive forms of the Russian ‘load’ verbs.

| Active forms only | Theme-Object construction frequency |

Goal-Object construction frequency |

Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| raw | relative | raw | relative | |||

| gruzit’ | IPFV1 | 180 | 72 | 69 | 28 | 249 |

| nagruzit’ | PFV-na | 34 | 23 | 113 | 77 | 147 |

| nagružat’ | IPFV2-na | 5 | 5 | 95 | 95 | 100 |

| zagruzit’ | PFV-za | 94 | 45 | 114 | 55 | 208 |

| zagružat’ | IPFV2-za | 43 | 43 | 57 | 57 | 100 |

| pogruzit’ | PFV-po | 253 | 99.6 | 1 | 0.4 | 254 |

| pogružat’ | IPFV2-po | 100 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

Relative frequencies of metaphorical contexts in the aspectual triplets of the ‘load’ verbs.

| Active forms only | Non-metaphorical frequency |

Metaphorical frequency |

Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| raw | relative | raw | relative | |||

| gruzit’ | IPFV1 | 186 | 75 | 63 | 25 | 249 |

| nagruzit’ | PFV-na | 110 | 75 | 37 | 25 | 147 |

| nagružat’ | IPFV2-na | 40 | 40 | 60 | 60 | 100 |

| zagruzit’ | PFV-za | 127 | 61 | 81 | 39 | 208 |

| zagružat’ | IPFV2-za | 56 | 56 | 44 | 44 | 100 |

Basic combinations of Theme and Goal in metaphorical representations of the ‘load’ verbs.

| Frequencies |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Goal representation | Theme representation |

gruzit’

|

nagruzit’

|

zagruzit’

|

nagružat’

|

zagružat’

|

|||||

| raw | % | raw | % | raw | % | raw | % | raw | % | ||

| human | information | 37 | 74 | 5 | 14 | 10 | 12 | 10 | 16 | 6 | 14 |

| human | work | 2 | 4 | 12 | 32 | 20 | 25 | 19 | 32 | 12 | 27 |

|

|

|||||||||||

| electronic device | file | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 21 | 26 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 34 |

| human | problems | 8 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 7 | 1 | 2 |

| words | meaning | 0 | 0 | 3 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 13 | 0 | 0 |

| facility | work | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 20 | 25 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 5 |

|

|

|||||||||||

| Total number of metaphorical representations | 50 | 37 | 81 | 60 | 44 | ||||||

5 Analysis

In this section the ‘load’ verbs are analyzed based on three parameters: the general distribution of constructions, the number of metaphorical extensions and specific metaphorical patterns attested for each verb.

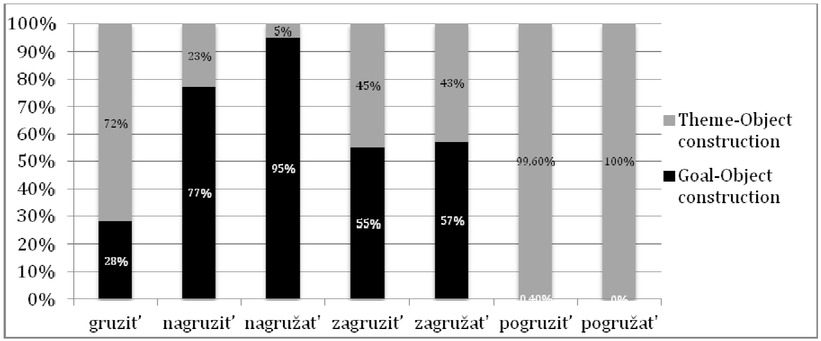

5.1 Triplets and constructions

The ‘load’ verbs are compatible with both the Theme-Object and the Goal-Object constructions (see examples 4 and 5 above). The relative distribution of the non-passive forms of the ‘load’ triplets across the Locative Alternation constructions is summarized in Table 7 and Figure 1 below. The verbs with the prefix po- (pogruzit’-PFV, pogružat’-IPFV2) are used almost exclusively in the Theme-object construction. IPFV2 with the prefix po- changes the meaning from ‘load’ to ‘submerge, sink’. For these reasons we have excluded the verbs with prefix po- from the further analysis.

Locative Alternation within the non-passive forms of the Russian ‘load’ verbs.

In Figure 1, we see that IPFV2s are similar to the corresponding PFVs but are all different from gruzit’-IPFV1. The unprefixed gruzit’ strongly prefers the Theme-Object construction. The prefixed verb nagruzit’-PFV and the secondary imperfective nagružat’-IPFV2 are nearly the mirror image, preferring the Goal-Object construction. The preference of na-verbs for profiling the Goal may be motivated by the SURFACE meaning of na- that has been mentioned in Section 2.3. The focus is rather placed on the changes that the Goal undergoes rather than on the placement of the Theme. On the contrary, pogruzit’-PFV and pogružat’-IPFV2 are almost exclusively restricted to the Theme-Object construction, suggesting a focus on the Theme that is loaded rather than the place where the load ends up. This may serve as an indirect evidence in support of LeBlanc’s claim (LeBlanc 2010), according to which the prototype of the prefix po- is related to PATH.

Zagruzit’-PFV and zagružat’-IPFV2 are the only verbs that show an almost even distribution across the two constructions. [8] A more elaborate analysis of the examples indicates that this could be due to additional metaphorical uses that the za-verbs have in the Goal-Object construction. As shown in (Sokolova 2013: 194), in the literal uses, zagruzit’-PFV favors the Theme-Object construction: the database contains 70 examples (55%) of the Theme-Object construction vs. 57 examples (45%) of the Goal-Object construction. However, in metaphorical contexts, the distribution is skewed towards the Goal-Object construction: 24 metaphorical examples (30%) used in the Theme-Object construction vs. 57 metaphorical examples in the Goal-Object construction (70%). A more even distribution of the two constructions in the case of za-verbs is in accordance with the “double” nature of the prototype of za- described in Section 2.3. The Theme-Object construction is compatible with the meaning BEHIND, whereas the uses in the Goal-Object construction represent the meaning COVER (or the meaning FILL as we are mostly dealing with three dimensional Goals).

In general, the prefix has an effect on the base verb, which is preserved in the secondary imperfectives. We see a clear contrast between the constructional profile of the unprefixed base verb and the prefixed ‘load’ verbs. Thus, prediction (A) is confirmed. At the same time the prefixed PFVs and their corresponding IPFV2s reveal closer profiles. Here a more detailed analysis, including analysis of the metaphorical extensions, is needed.

Janda et al. (2013a) and Kuznetsova and Sokolova (2016) have shown that secondary imperfectives are preferred in contexts where a result is implied. Thus, although IPFV1 and IPFV2 are used in the same constructions and similar contexts, we often get a semantic difference between these two imperfectives. Cf. examples (11–14) below that present a situation of loading people into vehicles (cars or trains):

Ja poterjala ljubimyj zont… zagružala dočku v mašinu, ostavila zont

na kryše. Tak i poexali… [Naši deti: Malyši do goda (forum) (2004)]

‘I lost my favorite umbrella… I was helping my daughter to get into

the car and left it on the top of the car. And we drove away like this.’

Provodnikii i passažiry, vstretiv ix kak rodstvenniki, zagružajut mat’

s det’mi v tambur. [Aleksandr Iličevskij. Pers (2009)]

‘The conductors … are helping the mother with the children to get onto the train.’

Včera moj tovarišč tak upilsja, čto gruzili ego v mašinu [9]

‘Yesterday my friend got so drunk that we had to load him into the car.’

– Telo bylo?

– Ešče by!

– Gruzili ego v mašinu? [10]

‘– Was there a body?

– Of course!

– Did you load it into the car?’

In examples (11) ad (12), the load is represented by people and their luggage. IPFV2 considers the boundaries of the Theme (and thus is more telic than IPFV1): zagružat’-IPFV2 is more commonly used with separate objects that need to be placed in a container (as opposed to a mass) and hence it is preferred in sentences that refer to careful actions. The verb gruzit’-IPFV1, on the other hand, does not set bounds on the Theme and is preferred when people are treated as a regular load or a mass. As can be seen from examples (13) and (14) above, the loading of dead bodies and drunk people is presented with IPFV1.

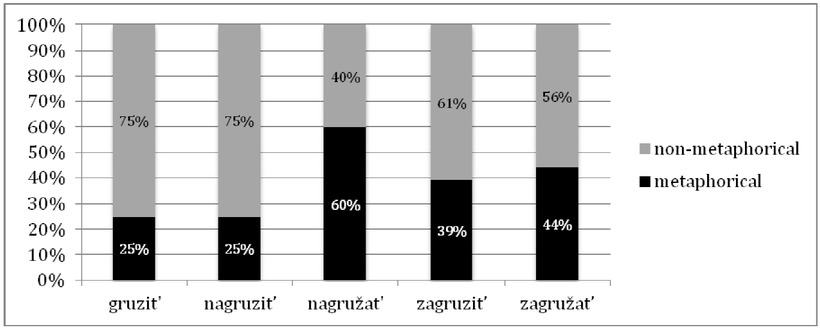

5.2 Triplets and metaphorical extensions

Of the three prefixed counterparts to the verb gruzit’ ‘load’, zagruzit’ is more often used metaphorically: zagruzit’ has 39% metaphorical uses, while nagruzit’ has 25% (see Table 8 and Figure 2). [11] The major metaphorical extensions of zagruzit’ involve a “person” (Goal), who serves as the metaphorical CONTAINER, and “information” or “work” (Theme), which represent metaphorical CONTENTS, as shown in (10), repeated here as (15), and (16).

Relative frequencies of metaphorical contexts in the aspectual triplets of the ‘load’ verbs.

Ax, vam interesny podrobnosti iz žizni

oh you-DAT are-interesting particulars-NOM from life-GEN

zvezd? Radi boga, Andrej Maksimov “zagruzit”

pop-stars-GEN? For god Andrej Maksimov-NOM za-load-FUT

vas ètoj informaciej.

you-ACC this information-INS

‘Oh, you are interested in the details of the life of our pop stars? No problem, Andrej Maksimov will provide you with this information.’

Zasedanie Gossoveta po kul’ture zagruzit

Meeting-NOM State-Council-GEN on culture-DAT za-load-FUT

rabotoj sotrudnikov Minsterstva kul’tury

work-INS members-ACC Ministry-GEN Culture-GEN

na bližajšie neskol’ko let.

for nearest-ACC few-ACC years-GEN

‘The agenda of the State Council on Culture will keep the members of the Ministry of culture busy for several years.’

The distribution of the two constructions among the ‘load’ verbs in the RNC indicates that IPFV2 behave differently from IPFV1 in terms of metaphorical extensions. As can be seen from Figure 2 above, IPFV2s indeed show a higher frequency of metaphorical uses than IPFV1: 25% (gruzit’) vs. 44% (zagružat’) and 60% (nagružat’), which supports prediction (B).

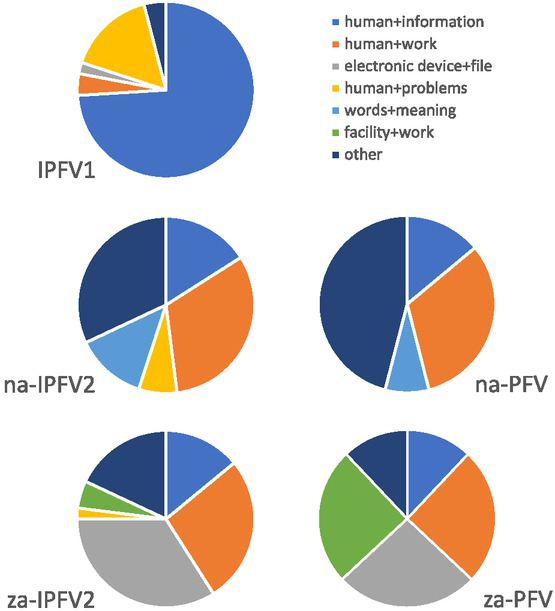

5.3 Triplets and metaphorical patterns

Although the verbs gruzit’ (IPFV1) and nagruzit’ (na-PFV) show similar general distribution of metaphorical constructions, they appear to have different combinations of metaphorical Themes and Goals within metaphorical representations. Table 9 and Figure 3 present the most frequent metaphorical patterns attested for the ‘load’ verbs. The patterns HUMAN+INFORMATION and HUMAN+WORK are attested for all the ‘load’ verbs considered in the section.

The distribution of various metaphorical patterns among the ‘load’ verbs.

Figure 3 illustrates that the unprefixed and prefixed ‘load’ verbs show different distributions of the basic metaphorical patterns. Prefixes seem to have a greater effect on the distribution of metaphorical patterns than verbal aspect. This way prediction (C) (IPFV2 are used in metaphorical patterns that are typical of prefixed perfective verbs) is confirmed. However, there is one pattern that characterizes only imperfective verbs, namely HUMAN+PROBLEMS:

GOAL:HUMAN + THEME:PROBLEMS

Bespomoščnoj ličnosti, čtoby ona ne “gruzilavas

Helpless personality in-order-to it not loadyou-ACC

svoimi problemami”, prosto ne nado davat’ sovety.

its problems-INS just not should give advice

‘You should not provide advice to a needy person unless you are prepared for him to dump [load of] his problems on you.’ (Tat’jana Blažnova. Karl Gustav Mannergeim. Memuary (2000) // “Kar’era”, 2000.02.01.)

The unprefixed verb gruzit’ ‘load’ selects mostly humans as metaphorical Goals that can be loaded with work, information or problems. Quite remarkably, however, it is the unprefixed ‘load’ verb that is more often used with the patterns HUMAN+INFORMATION and HUMAN+PROBLEMS, whereas the prefixed ‘load’ verbs to a greater extent select the pattern HUMAN+WORK.

To understand why IPFV1 is more frequent in the patterns HUMAN+INFORMATION and HUMAN+PROBLEMS than IPFV2s, let us look at a related example from Bulygina and Šmelev (1997), which represents a well-known dialogue from a Russian fairy-tale (18).

Kolobok, kolobok, ja tebja s”em!

‘Kolobok, I am going to eat you!’

Ne eš’ menja seryj volk!

‘Don’t eat me, Big Bad Wolf!’

?Ne s”edaj menja, seryj volk!

‘Do not eat me up, Big Bad Wolf!’

The primary imperfective est’ ‘eat’ in (18b) cannot be replaced with the secondary imperfective s”edat’, as shown in example (18c), as the secondary imperfective can only mean ‘Eat me, but do not eat me up’. Negated imperatives imply that the event will not take place and, therefore, no result will be achieved. Hence, the imperative with negation implies no result and tends to use the primary imperfective that does not consider the result (see Kuznetsova and Sokolova 2016 for detail).

Metaphorical patterns HUMAN+PROBLEMS and HUMAN+WORK resemble the tendencies in examples in (18). In the case of HUMAN+PROBLEMS, the boundary is not profiled as any amount of problems is unwelcome. The implication here is that the action should not take place at all. In HUMAN+WORK, work is an expected load, however, in this case it is important to keep it within the allocated boundaries (the potential of the person who represents the Goal) and not to exceed the limit.

In the remainder of the section I will focus on the effect that specific prefixes have on metaphorical patterns. The verbs with the prefix za- are characterized by the most “balanced” distribution where all major patterns constitute around 20%. The most frequent patterns here are HUMAN+INFORMATION, HUMAN+WORK, and FACILITY+WORK. Illustrative examples of major metaphorical representations listed in Table 9 and Figure 3 are given below.

GOAL:HUMAN + THEME:INFORMATION

Sledujuščie 15 minut ja “gružu” ego informaciej

Next 15 minutes I loadhim-ACC information-INS

o svoej rodine – ostrove Saxalin.

about my native-land – island Saxalin

‘In the next 15 minutes, I loadedhim with information about my native land – the land of Island of Saxalin.’ (Dmitrij Kovalenin. Marafonec Murakami (2002) // “Domovoj”, 2002.11.04.)

Xačatrjan ne sderžal neudovolstvija ot togo,

Xačatrjan didn’t suppress discontent from that

čto Kolomnin, kotorogo on toropilsja

what Kolomnin whom-ACC he was hurrying

“nagruzit’” informaciej, beskonečno otvlekaetsja.

to loadinformation-INS endlessly gets-distracted

‘Xačatrjan didn’t hide his discontent that Kolomnin whom he was trying to quickly fillwith information got distracted all the time.’ (Semen Daniljuk. Biznes-klass (2003).)

Ax, vam interesny podrobnosti iz žizni

oh you-DAT are-interesting particulars-NOM from life-GEN

zvezd? Radi boga, Andrej Maksimov “zagruzit”

pop-stars-GEN? For god Andrej Maksimov-NOM za-load-FUT

vas ètoj informaciej.

you-ACC this information-INS

‘Oh, you are interested in the details of the life of our pop stars? No problem, Andrej Maksimov will provide you with this information.’

GOAL:HUMAN + THEME:WORK

Ja, skažem, idu pokupat’ trubočnika ljubimoj ljaguške,

I, let’s-say, go to-buy sludge-worm favourite frog

a druz’ja, radujas’ čužoj bede, gruzjatporučenijami.

and friends, gloating another’s misfortune loadcommissions-INS

Exat’ nikto ne xočet.

go nobody not wants

‘Let’s say, I am going to the pet market to buy a sludge worm for my favorite frog. My friends, gloating over my misfortune, start commissioning me. Nobody wants to go.’ (Aleksej Torgašev. “Ptičku” snova žalko. Kak ob’’jasnit’ trudjaščimsja, počemu na Ptič’em rynke nel’zja pokupat’ košek (2002) // “Izvestija”, 2002.01.20.)

Neobxodim byl professional, kotoryj by stal “parovozom”,

Needed was professional which would become locomotive,

nagruzil sebja vsej rabotoj.

load itself-ACC all work-INS]

‘They needed a work horse, someone who would loadhimselfupwith all the work’ (I. È. Kio. Illjuzii bez illjuzij (1995–1999).)

Zasedanie Gossoveta po kul’ture zagruzitrabotoj

Meeting State-Council-GEN on culture will-loadwork-INS

sotrudnikov Minsterstva kul’tury na bližajšie neskol’ko

members- Ministry- Culture- for nearest few

ACC GEN GEN

let.

years

‘The agenda of the State Council on Culture will keepthe members of the Ministry of culture busy for several years.’ (Andrej Reut. Gossovet gotov spasti rossijskuju kul’turu // “Gazeta”, 2003.)

GOAL:FACILITY + THEME:WORK

V samom dele, razve pod vlijaniem reklamy

in very thing if under influence advertisement-GEN

my stanem dol’še kipjatit’ čajnik na gazovoj konforke,

we begin longer burn boiler on gas burner

a elektrocstancii zagruzjat rabotoj lišnie turbiny?

and power-plants will-loadwork-INS additional turbines

‘Really, is it possible that due to the advertisement we will boil the kettle longer on a gas burner or that the electrical power-plants will provideadditional turbines with work?’ (Veseljaščij gaz (2003) // “Novaja gazeta”, 2003.01.16.)

The ‘load’ verbs prefixed in za- demonstrate metaphorical patterns in both constructions, whereas other verbs are used metaphorically almost exclusively in one of the constructions (gruzit’ and nagruzit’ in the Goal-Object, and pogruzit’ in the Theme-Object). In addition to the metaphorical patterns mentioned above that go with the Goal-Object construction, zagruzit’ (za-PFV) and its IPFV2 zagružat’ show metaphorical extensions in the Theme-Object construction (cf. the pattern ELECTRONIC DEVICE+FILE):

GOAL:ELECTRONIC DEVICE + THEME:FILE

Každyj, kto rassčityvaet v Afinax zapustit’ v set’ virus

Everybody who intends in Athens to-launch into net-ACC virus

ili zagruzit’drugoe PO, smožet ubedit’sja, čto

or loadanother software-ACC will-be-able to-see that

dostup k diskovodam, a takže k USB-portam na PK i

access to disk-drives and also to USB-ports on PC and

serverax zakryt.

servers closed

‘Everybody with the intention to launch a virus or uploadsoftware onto the net in Athens will see that the access to the disk drives as well as to the USB ports on PCs and servers is closed.’ (Olimpiada komp’juternaja // “Computerworld”, 2004.)

Unlike the unprefixed verb gruzit’ (IPFV1) and the verbs with the prefix za-that show a strong preference towards certain patterns, the verbs prefixed in na- are characterized by a number of additional patterns, such as loading words or texts with meaning (the discussion of other smaller patterns is provided below).

GOAL:WORDS + THEME:MEANING

Posle simvolistov … slovo utratilo ves; akmeisty zaxoteli bylo

After symbolists … word lost weight, acmeists wanted was

ego nagruzit’ – no polučalas’ libo priključenčeskaja proza,

it-ACC load – but came-out either adventurous prose

libo nesvjaznoe, xot’ i angel’skoe bormotanie

or incoherent, although and angel-like murmur

‘After symbolists … the word lost its significance, acmeists wanted to fill it with a new meaning but this attempt ended up either as adventurous prose or as an incoherent, even though angelic murmur…’ (Dmitrij Bykov. Orfografija (2002).)

These additional patterns build upon the original semantics of the prefix na-. As can be seen from example (27) above, the meaning of the word is compared to a weight: obtaining a meaning is accumulating a load on the surface of a weighing scale. The heavier the weight, the more the word is worth (hence its significance).

The option “other” in Figure 3 includes other metaphorical combinations of Theme and Goal which are represented by merely one or two examples. As follows from Figure 3, metaphorical representations of both gruzit’ (IPFV1) and zagruzit’ (za-PFV) are constituted by larger groupings whereas nagruzit’ (na-PFV) is used in a number of smaller combinations. This is probably related to the fact that metaphorical contexts of the na-PFV mostly deal with more abstract notions for both Theme and Goal (see examples 28 and 29 below).

GOAL: TRIP + THEME: AIM

Ja ponjala: nado beč, štob ne vzrastit’ razdraženie uže

I realized: needed run in-order-to not grow irritation already

k Šure, kotoruju ja nežno ljublju, i ne vinovata ona,

towards Šura which I tenderly love and not to-blame she

čto ja nagruzila rodstvennuju poezdku k nej podspudnoj zadačej.

that I loadedfamily trip-ACC to her additional task-INS

‘I realized that I need to run if I didn’t want to exhibit frustration towards Šura, who I tenderly love. It is not her fault that I added a personal task to the family trip.’ (Galina Ščerbakova. Mitina ljubov’ (1996).)

GOAL: RELATIONSHIP THEME: TRUTH

Ona … bojalas’ daže treščiny, kotoraja mogla pojavit’sja, esli na

She … was-afraid even crack which could appear if on

ix xrupkie otnošenija nagruzit’ sliškom mnogo pravdy.

their fragile relations-ACC load too-much truth-ACC]

‘She was afraid that their fragile relationship would crack under the burden of too much truth’ (Ol’ga Novikova. Ženskij roman (1993).)

In the case of (27) having a considerable weight is something desirable as words should be meaningful, and that is what the poets are concerned about. Examples (28) and (29) also reflect the WEIGHT metaphor, however, in this case the weight is a heavy load: the family trip is burdened by a personal task and the fragile relationship could crack under the burden of too much truth.

Summing up, we can say that the prefix has a greater impact on metaphorical patterns than aspect. Metaphorical uses depend on the semantics of the prefix, which is preserved both in the perfective counterparts and IPFV2s. Imperfectives are more compatible with metaphorical contexts where the boundaries are not profiled. Hence, IPFV1 is the most natural verb with the metaphorical patterns HUMAN+INFORMATION and HUMAN+PROB-LEMS, which imply that the action should not be taking place.However, in the patterns where the boundaries are emphasized, for instance HUMAN+WORK, IPFV2s are preferred over IPFV1.

6 Conclusions

The data presented in this article offers further support for the Telicity Hypothesis according to which IPFV2s become more “oriented towards a result” due to the presence of a prefix. Based on the hypothesis we made the following predictions, all of which have been confirmed to a different extent:

Although characterized by similar semantics, all three verbs in a triplet are used with different constructions.

IPFV2s have a higher frequency of metaphorical uses than IPFV1s.

IPFV2 are used in metaphorical patterns that are typical of prefixed perfective verbs.

The distribution of the two constructions among the ‘load’ verbs in the RNC indicates that IPFV2s behave differently from IPFV1s in terms of constructions and metaphorical extensions, confirming prediction (A). In this sense, “three” is definitely “company”. However, constructional profiles of PFVs and their corresponding IPFV2s have shown to be rather similar. The major difference between them lies in the frequency of metaphorical uses and individual metaphorical patterns.

IPFV2s indeed show a higher frequency of metaphorical uses than IPFV1 (prediction (B)): 25% (gruzit’) vs. 44% (zagružat’) and 60% (nagružat’). The metaphorical patterns of IPFV2s are more similar to the patterns attested for the perfective counterparts than to those of IPFV1 (prediction (C)). This observation serves as evidence that the prefix affects metaphorical uses, contrasting perfective verbs and IPFV2s to IPFV1s.

IPFV2 is preferred when metaphorical context emphasizes the boundaries of the Theme/Goal or the change that it undergoes (e.g. loading humans with work, i.e. fitting the load into the existing boundaries). If the boundaries of the Theme/Goal are not profiled, the IPFV1 is preferred (e.g. in a situation of loading humans with information or problems it is implied that the action should not be taking place at all).

The results presented in this article have several relevant implications for linguistic theory. On a more general level, they are consistent with the previous claim that certain grammatical forms might be more susceptible to metaphor (cf. a greater number of metaphorical extensions in the case of IPFV2 compared to IPFV1). On a more specific level, the metaphorical uses show a closer relation between the prefixed perfective and the prefixed imperfective rather than between the simplex base verb and its prefixed perfective (which supports the intuition of Isačenko and some other scholars). Finally, the ‘load’ verbs provide indirect support for some recent proposals concerning the central meanings of major Russian verbal prefixes. Compared to the other ‘load’ verbs, the verbs prefixed in za- show a more even distribution among the Theme-Object and the Goal-Object constructions in both non-metaphorical and metaphorical contexts, which is compatible with a double prototype proposed for the prefix za-. Unlike the ‘load’ verbs prefixed in za-and na-, the verbs prefixed in po- are attested almost exclusively in the Theme-Object construction, suggesting the relevance of PATH to the central meaning of po-.

The study is based on a closed group of verbs, which leaves several important questions open. Will these findings be supported by aspectual triplets representing other semantic classes? If the verbs that are more oriented towards a result (IPFV2s) are more likely to appear in metaphorical uses, is it true that, in general, metaphors are more concerned about the changes that the Theme undergoes rather than about the process itself? The metaphorical patterns that are well represented among the ‘load’ verbs are all conventional expressions. Based on this study, we can only assume that the resultative state is more commonly used as a source for conventional verbal metaphors, which results in IPFV2s being more often used metaphorically than IPFV1. It would be beneficial to extend this study to triplets with different semantics and to take into consideration less conventional metaphors.

References

Apresjan, Ju.D. 1995. “Traktovka izbytočnyx aspektual’nyx paradigm v tolkovom slovare”. Izbrannye trudy. V.2. Integral’noe opisanie jazyka. Moscow: Škola “Jazyki russkoj kul’tury”. 102–113.Search in Google Scholar

Berdičevskis, A. and H.M. Eckhoff. 2014. “Verbal constructional profiles: reliability, distinction power and practical applications”. Proceedings of the Thirteenth International Workshop on Treebanks and Lingustic Theories (TLT13), December 12–13, Tübingen, Germany.Search in Google Scholar

Bulygina, T.V. and A.D. Šmelev. 1997. Jazykovaja konceptualizacija mira (na materiale russkoj grammatiki). Moskva.Search in Google Scholar

Bybee, J.L. and Ö. Dahl. 1989. “The creation of tense and aspect systems in the languages of the world”. Studies in Language 13(1). 51–103.10.1075/sl.13.1.03bybSearch in Google Scholar

Croft, W. 2012. Verbs: Aspect and causal structure. Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199248582.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Čertkova, M.Ju. 1996. Grammatičeskaja kategorija vida v sovremennom russkom jazyke. Moskva.Search in Google Scholar

Deignan, A. 2005. Metaphor and corpus linguistics. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/celcr.6Search in Google Scholar

De Smet, H., F. D’hoedt, L. Fonteyn and K. Van Goethem. 2018. “The changing functions of competing forms: Attraction and differentiation”. Cognitive Linguistics 29(2). 197–234.10.1515/cog-2016-0025Search in Google Scholar

Dickey, S.M. 2012. “Orphan prefixes and the grammaticalization of aspect in South Slavic”. Jezikoslovlje, 13(1). 71–105.Search in Google Scholar

Dickey, S.M. 2007. “A prototype account of the development of delimitative po- in Russian”. In Divjak, D. and A. Kochańska (eds.), Cognitive paths into the Slavic domain. Mouton de Gruyter. 326–371.10.1515/9783110198799.4.329Search in Google Scholar

Evgen’eva, A.P. (ed.) 1999. Slovar’ russkogo jazyka [A dictionary of Russian]. (In four volumes.) Moscow: Russkij jazyk.Search in Google Scholar

Fonteyn, L. and Ch. Maekelberghe. 2018. “Competing motivations in the diachronic nominalization of English gerunds”. Diachronica 35(4). 487–524.10.1075/dia.17015.fonSearch in Google Scholar

Glovinskaja, M.Ja. 2001. Mnogoznačnost’ i sinonimija v vido-vremennoj sisteme russkogo glagola. Moskva.Search in Google Scholar

Goldberg, A.E. 1995. Constructions: A Construction Grammar approach to argument structure. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.Search in Google Scholar

Gries, S.Th. and A. Stefanowitsch. 2004. “Extending collostructional analysis: A corpus-based perspective on ‘alternations’”. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics 9(1). 97–129.10.1075/ijcl.9.1.06griSearch in Google Scholar

Isačenko, A.V. 1960. Grammatičeskij stroj russkogo jazyka v sopostavlenii s slovackim. Morfologija (Tom 2). Bratislava.Search in Google Scholar

Janda, L. 1985. “The meaning of Russian verbal prefixes: Semantics and grammar”. In Timberlake, A. and M.S. Flier (eds.), The scope of Slavic aspect. Columbus, OH: Slavica. 26–40.Search in Google Scholar

Janda, L., A. Endresen, J. Kuznetsova, O. Lyashevskaya, A. Makarova, T. Nesset, and S. Sokolova. 2013a. Why Russian aspectual prefixes aren’t empty: prefixes as verb classifiers. Columbus, OH: Slavica Publishers.Search in Google Scholar

Janda, L., H. Baayen, A. Endresen, A. Makarova and T. Nesset. 2013b. “Making choices in Russian: Pros and cons of statistical methods for rival forms”. Space and time in Russian temporal expressions, a special issue of Russian Linguistics 37(3). 253–291.10.1007/s11185-013-9118-6Search in Google Scholar

Janda, L. and O. Lyashevskaya. 2013. “Semantic Profiles of Five Russian Prefixes: po-, s-, za-, na-, pro-“. Journal of Slavic Linguistics 21(2). 211–258.10.1353/jsl.2013.0012Search in Google Scholar

Janda, L. and O. Lyashevskaya. 2011a. “Grammatical profiles and the interaction of the lexicon with aspect, tense and mood in Russian”. Cognitive Linguistics 22(4). 719–763.10.1515/cogl.2011.027Search in Google Scholar

Janda, L. and O. Lyashevskaya. 2011b. “Prefix variation as a challenge to Russian aspectual pairs: are завязнуть and увязнуть ‘get stuck’ the same or different?” Russian Linguistics 35(2). 147–167.10.1007/s11185-011-9076-9Search in Google Scholar

Janda, L. and V. Solovyev. 2009. “What constructional profiles reveal about synonymy: A case study of Russian words for SADNESS and HAPPINESS”. Cognitive Linguistics 20(2). 367–393.10.1515/9783110335255.295Search in Google Scholar

Jasai, L. 2001. “O specifike vtoričnyx imperfektivov vidovyx korreljacij”. In Nedjalkov, I.V. (ed.), Issledovanija po jazykoznaniju: K 70-letiju členakorrespondenta RAN Aleksandra Vladimiroviča Bondarko. Sankt-Peterburg. 106–118.Search in Google Scholar

Kasevič, V.B. 1977. Elementy obščej lingvistiki. Moskva.Search in Google Scholar

Keller, H.H. 1992. “Measuring Russian prefixation polysemy: The 53 most frequent za- verbs matched against 20 meaning headings for za-”. Russian language journal XLVI(153). 35–51.Search in Google Scholar

Kozera, I. 2018. Semantika i pragmatika vtoričnoj imperfectivacii v sovremennom russkom jazyke na osnovanii korpusnogo analiza. (Język i metoda 5.) Kraków: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego.Search in Google Scholar

Kuznetsova, Ju. 2015. Linguistic profiles: Going from form to meaning via statistics. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.10.1515/9783110361858Search in Google Scholar

Kuznetsova, Ju. and S. Sokolova. 2016. “Aspectual triplets in Russian: Semantic predictability and regularity”. Russian Linguistics 40(3). 215–230.10.1007/s11185-016-9166-9Search in Google Scholar

Langacker, R.W. 1987. Foundations of Cognitive Grammar I. Stanford: Stanford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Le Blanc, N.L. 2010. The polysemy of an “empty” prefix: A corpus-based cognitive semantic analysis of the Russian verbal prefix po-. (PhD dissertation, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.)Search in Google Scholar

Maslov, Ju.S. 1984. “Vid i leksičeskoe značenie glagola v sovremennom russkom literaturnom jazyke”. In Maslov, Ju. S. Očerki po aspektologii. Leningrad. 48–65.Search in Google Scholar

Nichols, J. 2008. “Prefixation and the locative alternation in Russian contact verbs”. Presentation at the annual conference of the American Association of Teachers of Slavic and East European Languages, San Francisco, December 27–30, 2008.Search in Google Scholar

Nordrum, M. 2017. “The aspectual triplets of putat’: the Telicity Hypothesis and two ways to test it”. Russian Linguistics 41. 239–260.10.1007/s11185-017-9179-zSearch in Google Scholar

Ožegov, S.I. and N.Ju. Švedova 2001. Slovar’ russkogo jazyka [A dictionary of Russian]. Moscow: Russkij jazyk.Search in Google Scholar

Percov, N.V. 2001. Invarianty v russkom slovoizmenenii. Moskva.Search in Google Scholar

Petruxina, E.V. 2000. Aspektual’nye kategorii glagola v russkom jazyke v sopostavlenii s češskim, slovackim, pol’skim i bolgarskim jazykami. Moskva.Search in Google Scholar

Plungjan, V.A. 2011. Vvedenie v grammatičeskuju semantiku: grammatičeskie značenija i grammatičeskie sistemy jazykov mira. Moskva.Search in Google Scholar

Radden, G. and K.-U. Panther. 2004. “Introduction: Reflections on motivation”. In Radden, G. and K.-U. Panther (eds.), Studies in linguistic motivation. Berlin, New York: Mouton de Gruyter. 1–46.Search in Google Scholar

Romanova, E. 2007. Constructing perfectivity in Russian. (PhD Dissertation, University of Tromsø.)Search in Google Scholar

Russell, P. 1985. “Aspectual properties of the Russian verbal prefix na-”. In Michael, S. and A. Timberlake Flier (eds.), The scope of Slavic aspect. 59–75.Search in Google Scholar

Sokolova, S. 2013. “Verbal prefixation and metaphor: How does metaphor interact with constructions?” Journal of Slavic LinguisticsAspect in Slavic: Creating time, creating grammar) 21(1). 171–204.10.1353/jsl.2013.0001Search in Google Scholar

Sokolova, S. 2012. Asymmetries in linguistic construal: Russian prefixes and the locative alternation. (PhD dissertation, University of Tromsø.) Available at <https://munin.uit.no/handle/10037/4483Search in Google Scholar

Sokolova, S. and A. Endresen. 2017. “The return of the prefix za-, or what determines the prototype”. In Makarova, A., S.M. Dickey and D.S. Divjak (eds.), Thoughts on language: Studies in cognitive linguistics in honor of Laura A. Janda. Bloomington, IN: Slavica Publishers.Search in Google Scholar

Shull, S. 2003. The experience of space. The privileged role of spatial prefixation in Czech and Russian. Munich: Verlag Otto Sagner.Search in Google Scholar

Steen, G.J. 2007. Finding metaphor in grammar and usage: A methodological analysis of theory and research. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/celcr.10Search in Google Scholar

Sullivan, K. 2013. Frames and constructions in metaphoric language (Constructional Approaches to Language 14). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/cal.14Search in Google Scholar

Šaxmatov, A.A. 1952. Učenie o častjax reči. Moskva: Učebno-pedagogičeskoe izdatel’stvo.Search in Google Scholar

Švedova, N.Ju. (ed.). 1980. Russkaja grammatika [Russian grammar]. Volume 1. Moskva: Nauka.Search in Google Scholar

Talmy, L. 2000. Towards a Cognitive Semantics (2 vols.). Cambridge, MA and London: MIT Press.10.7551/mitpress/6847.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Timberlake, A. 2004. A reference grammar of Russian. Cambridge.Search in Google Scholar

Townsend, C.E. 2008. Russian word-formation. Slavica Publishers.Search in Google Scholar

Veyrenc, J. 1980. “Un problème de formes concurrentes dans l’économie de l’aspect en russe: imperfectifs premiers et imperfectifs seconds”. In Études sur les verbe russe. Paris. Institut d’études slaves. 159–179.Search in Google Scholar

Vinogradov, V.V. 1947. Russkij jazyk [The Russian language]. Moscow–Leningrad: Učebno-pedagogičeskoe izdatel’stvo.Search in Google Scholar

Xrakovskij, V.S. 2005. “Aspektual’nye trojki i vidovye pary”. Russkij jazyk v naučnom osvjaščenii 9(1). 46–59.Search in Google Scholar

Zaliznjak, A A. and I. Mikaeljan. 2010. “O meste vidovyx troek v aspektual’noj sisteme russkogo jazyka”. Dialog 2010. Moscow. 130–136.Search in Google Scholar

Zaliznjak, A.A. and A.D. Šmelev. 2000. Vvedenie v russkuju aspektologiju. Moskva.Search in Google Scholar

© 2021 Faculty of English, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań, Poland

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Introduction

- A grammatical construction in the service of interpersonal distance regulation. The case of the Polish directive infinitive construction

- Real-life pseudo-passives: The usage and discourse functions of adjunct-based passive constructions

- The network of reflexive dative constructions in South Slavic

- On motivation and incoordination in grammar – The case of two Polish exclamative constructions

- When three is company: The relation between aspect and metaphor in Russian aspectual triplets

- Between spatial domain and grammatical meaning: The semantic content of English telic particles

- An aspectual contour of phrasal verb constructions with English think

Articles in the same Issue

- Introduction

- A grammatical construction in the service of interpersonal distance regulation. The case of the Polish directive infinitive construction

- Real-life pseudo-passives: The usage and discourse functions of adjunct-based passive constructions

- The network of reflexive dative constructions in South Slavic

- On motivation and incoordination in grammar – The case of two Polish exclamative constructions

- When three is company: The relation between aspect and metaphor in Russian aspectual triplets

- Between spatial domain and grammatical meaning: The semantic content of English telic particles

- An aspectual contour of phrasal verb constructions with English think