Abstract

The paper has a specific and focused aim: to unveil a possible route to DOM, the crosslinguistically widely attested phenomenon whereby direct objects are introduced by a preposition, with interpretive constraints. The prepositional marker is ‘a’ in Italian and in (the majority of) Romance. The investigation is based on both comparative data from Romance and on some relevant experimental results from the acquisition of Italian involving a-Topics. The insights that syntactic cartography may provide on the characterization of such route is the leading note of the investigation: a-marking starts out on direct objects topics, only occurring when the (animate) direct object is preposed in the left periphery of the clause; then a-marking involves clause internal direct object topics in the vP-periphery; and finally a-marking is Case related in the small ‘v’ spine; the latter, is also implicated in causatives and in constructions involving benefactive arguments. The acquisition results reviewed indicate the use of left peripheral a-Topics in children’s elicited productions in Italian, which are not attested in the target language, thus illustrating a cartographically defined space of children’s grammatical creativity.

1 Introduction

It is a well-known and much debated fact that in several languages the direct object of a transitive verb can be marked in different ways depending on a number of properties – among which characteristically, its animacy, definiteness, specificity …. – leading to the differential object marking/DOM phenomenology (Bossong 1991). Romance languages are no exception to this widespread morphosyntactic phenomenon, which also involves some discourse related contextual properties concerning the direct object, such as its presupposed status, its topicality (Ledgeway forthcoming; Ledgeway et al. 2019; Leonetti 2004), as well as some form of affectedness (Belletti 2018a; Guasti 1993). The literature on DOM is extremely rich and variegated. The following pages will not do justice to the richness of such literature as this is not their aim. Rather, this paper has a specific and focused aim: a proposal on what may be seen as a route to DOM will be sketched out, so that, in the end, (some of) the various bricks ultimately involved in the phenomenon will be unveiled. The investigation will be based on both comparative data from Romance (Belletti 2018b) and on some relevant experimental results from the acquisition of Italian (mainly Belletti and Manetti 2019) involving a-Topics. The insights that syntactic cartography may provide on the characterization of such route will be one leading note of the investigation.

2 The Cartography of a-Topics in an Italian/Romance Perspective[1]

2.1 a-Topics and the Route to DOM

Two specific properties will be highlighted in this section, both from a diachronic and a synchronic dimension, looking at the prepositional marking of the direct object from the perspective of Romance, in which the differential marker is typically the preposition ‘a’.[2] The two properties are the following:

The diachronic development of DOM in Spanish indicates that a-marking was not present in earlier stages on the direct object when it was located in the canonical sentence internal position, yielding the order SVO (von Heusinger 2008, also based on Laka’s 2006 analysis of Cid). In contrast, preposition ‘a’ was substantially present when the direct object was preposed in a clause external Topic position, as in clitic left dislocation/CLLD constructions. In modern Spanish, instead, the direct object is typically a-marked in clause internal position thus illustrating a prototypical instance of DOM in Romance.

In some current Romance varieties, a-marking of the object is similarly limited to cases in which the direct object is preposed into the left peripheral Topic position in CLLD. This is straightforwardly the case in Balearic Catalan as described in Escandell-Vidal (2009); to some extent, it is also the case in modern Spanish where preposed objects in CLLD are always a-marked even in those cases in which they may appear without the marker in the clause internal position (e.g. with indefinites in the generic reading, Leonetti 2004); such marking in CLLD has effects on the interpretation (yielding a specific reading of the indefinite left dislocated direct object); to a more moderate extent, this is also the case in standard Italian (Belletti 2018a, 2018b) where preposed pronominal objects in CLLDs are typically a-marked (quasi obligatorily in first and second person, Berretta 1989).

Thus, a-marking appears to be a process primarily affecting the direct object when it is a topic, in the left peripheral Topic position.[3] Presence of the marker adds some further interpretive feature on the DP to be combined with its topicality. To a first approximation, some affected/involvement interpretation can be identified as the enrichment brought about by the presence of preposition ‘a’ introducing the left peripheral object topic (Belletti 2018a, and Section 2.1.1). Below some relevant contrasts are reproduced, both for the diachronic and the synchronic dimensions indicated in i. and ii, above, in i.′ and ii.′, respectively:

| A | las | sus | fijas | en braço las | prendia | (Cid, 275) | |

| to | the | his | daughters in | arm them | hold-3.SG | ||

| ‘He gathered his daughters in his arms’ | |||||||

| (adapted from von Heusinger 2008: 19′b)[4] | |||||||

As reported in von Heusinger (2008), 73% of animate definite direct objects in Cid were a-marked and preposed yielding a CLLD construction. In contrast, 80% of animate definite direct objects were not a-marked in sentence internal position, as illustrated in (2) and (3):

| En braços | tenedes | mis fijas | tan blancas | commo | el | ||||

| in arms | have-2PL | my daughters | as white | as | the | ||||

| sol | (Cid, 2333) | ||||||||

| sun | |||||||||

| ‘In your arms you hold my daughters, as white as the sun’ | |||||||||

| Escarniremos | las fijas | del | Campeador | (Cid, 2551) | |||||||||

| will-humiliate | the daughters | of the | Battler | ||||||||||

| ‘We shall humiliate the Battler’s daughters’ | |||||||||||||

| (von Heusinger 2008: 18a, b) | |||||||||||||

Hence, a-marking is limited to occurring in the left periphery in Old Spanish.

| Balearic Catalan (Majorcan) | ||||||

| a. | An | aquesta | darrera [frase] | noltros | la diríem | així |

| To | this | last [sentence] | we | it say COND.1PL | like that | |

| ‘This last sentence, we would say this way’ | ||||||

| (Escandell-Vidal 2009: 36) | ||||||

| b. | I | va | anar | ja | a amenaçar | es general |

| and | have.Pst.3.SG | go | already | to menace | the general | |

| ‘So he went to threaten the general’ | ||||||

| (Escandell-Vidal 2009: 24, b) | ||||||

As described in Escandell-Vidal (2009), a-marking is exclusively performed on the left peripheral direct object topic, as the contrast in (4) illustrates. Such marking is optional. This is in contrast with Modern Spanish, where a-marking is obligatory on the left dislocated (animate) object in CLLD. This is so also in those cases in which it may be optional in clause internal position in DOM-Spanish, as Leonetti (2004) clearly illustrates through the following contrasts (also Belletti 2018a; Laka 1987):[5]

| Simple declarative | |

| a. | Ya conocía (a) muchos estudiantes |

| already (I) knew many students | |

| b. | Habían incluido (a) dos catedráticos en la lista |

| they) had included two professors in the list | |

| CLLD | |

| a*. | (A) muchos estudiantes, ya los conocía | ||||

| (to) many students, (I) alreadu knew them(cl) | |||||

| b*. | (A) dos catedráticos, los habían incluido en la lista | ||||

| (to) two professors, (they) had included them(cl) in the list | |||||

| (adapted from Leonetti 2004: 12a, b) | |||||

As interestingly observed by von Heusinger (2008), modern translations of the sentences from Cid in (2) give rise to a minimal contrast with Old Spanish, as a-marking is quite widespread for direct objects in clause internal position in Modern Spanish, a classical manifestation of DOM. The contrast is illustrated in the examples reproduced in (7), from the indicated translations, in minimal contrast with (2) and (3):

| a. | tenéis | a mis hijas, | tan | blancas | come | el | ||

| have-2.PL | DOM | my daughter | as | white | as the | |||

| sol, | en | vuestros brazos | ||||||

| sun | in | your arms | ||||||

| (Cantar de mio Cid, Translation A.Reyes. Madrid: Espasa Calpe 1976) | ||||||||

| ‘In your arms you hold my daughters, as white as the sun’ | ||||||||

| b. | y | podremos | escarnecer | a | la hijas del Campeador | |||

| and | will-can1PL | humiliate | DOM | the daughters of the Battler | ||||

| (Cantar de mio Cid, Translation A.Reyes. Madrid: Espasa Calpe 1976) | ||||||||

In standard Italian a-marking is instead generally absent, in both clause internal and in the left peripheral topic position. However, whereas in the clause internal position it is completely excluded, in the left peripheral topic position it can be more or less accepted in some limited cases, with some variation among speakers. The best case allowing for a-marking of the left dislocated object is provided by the left dislocated experiencer direct object of psych-verbs of the preoccupare/worry class. The example below quoted from Belletti and Rizzi ‘s (1988) (footnote 27; also Belletti 2018a; Berretta 1989), due to Paola Benincà (Benincà 1986) illustrates the point:

| a. | ? A Gianni, questi argomenti non l’hanno convinto |

| to Gianni, these arguments him-CL have not convinced | |

| b. | *A Gianni, la gente non lo conosce |

| to Gianni, people him-CL do not know |

The possibility of (8)a contrasts with the complete unacceptability of (9)a. In (9) there is no difference in acceptability between the object experiencer (9a) and the theme/patient object (9)b, both are excluded, in contrast with (8):

| a. | * Questi argomenti non hanno convinto a Gianni |

| these arguments have not convinced to Gianni | |

| b. | * La gente non conosce a Gianni |

| people do not know to Gianni |

a-Marking of the preposed object is (quasi) obligatory in standard Italian when the object is a pronoun (in particular first and second person, singular, but also more generally). (10) illustrates this point with some relevant examples (from Belletti 2018a; Berretta 1989):

| a. | A me/?*Me non mi si inganna |

| to me/me they do not fool me | |

| b. | A te /*?te ti licenziano di sicuro |

| to you/you they you-CL fire for sure | |

| c. | ?A lui /✓lui lo rispettano tutti |

| to him/him they him-CL respect all | |

| d. | A noi sul lavoro non ci assume più nessuno |

| to us on work nobody us-CL hire anymore |

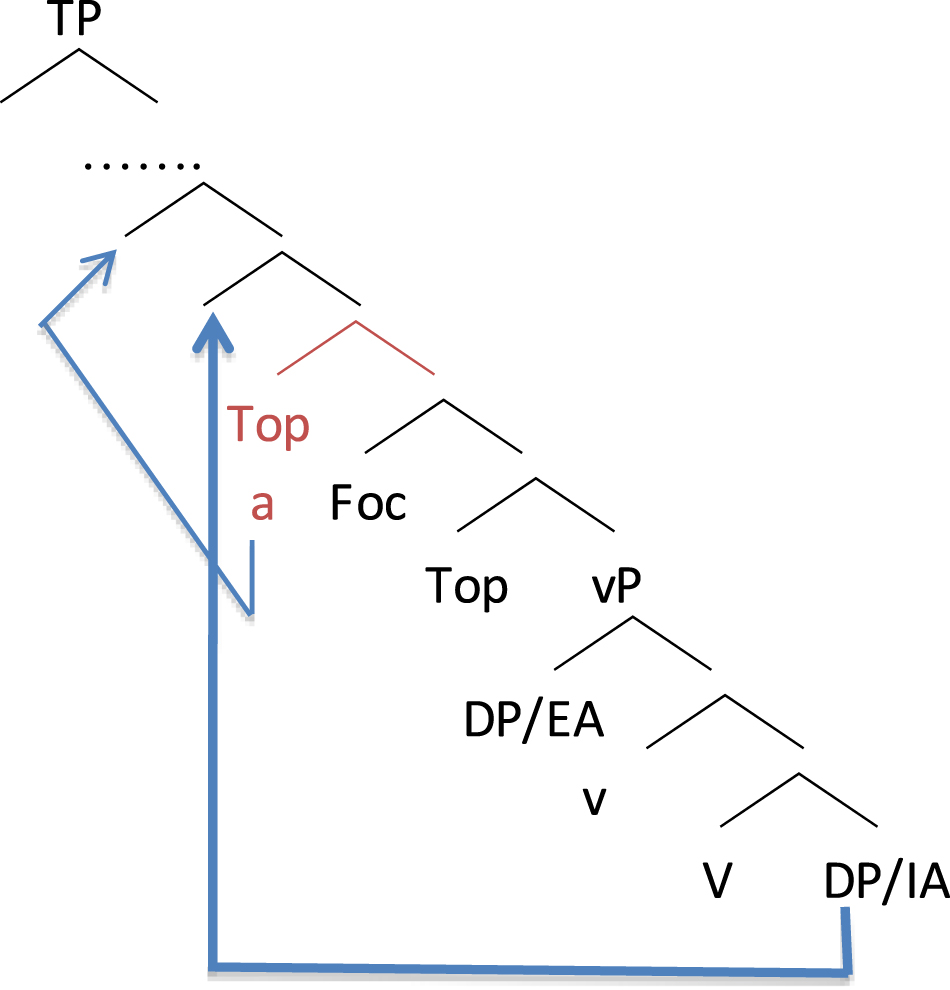

In conclusion, with different constraints and on a variable degree, a-marking of preposed object topics is characteristically a property associated with the topic position in the left periphery. Given the map of the left periphery (Rizzi 1997; Rizzi and Bocci 2017 for detailed updated description) in which a high Topic position is present, we conclude that preposition ‘a’ may thus be associated with the left peripheral Topic head, as illustrated in (11). The diagram in (11) also indicates the steps of the topicalization process, with the direct object moving to Spec/TopP and the preposition raising above it to some higher position, thus reestablishing the pre-positional order proper of Italian:[6]

|

It is often observed that in DOM-languages, the interpretation of the marked direct object in a sentence internal position is presupposed to some extent (Ledgeway forthcoming; Ledgeway et al. 2019 and references cited there). A way to express this property cartographically may be to allow that in such languages also the clause internal low topic position in the periphery of the vP (Belletti 2004) be endowed with preposition ‘a’ (for more on the interpretation it brings about, 2.1.1 below), in a parallel fashion. This is the hypothesis illustrated in (12):

|

2.1.1 On the Nature of Preposition ‘a’

A natural question arises: What is the contribution of preposition ‘a’ to the topic interpretation? A precise answer to this question is not easy to formulate as the relevant interpretive feature(s) is(are) not transparent. Nevertheless, a crosslinguistic comparison with English may contribute some relevant ingredients towards it. The usual translation of ‘a’ in English is preposition ‘to’, a correspondence also adopted in (some of) the glosses above (footnote 4). However, at a closer look, preposition ‘a’ and preposition ‘to’ do not completely coincide in the meaning they contribute. In particular, as first pointed out in Kayne (2004), English ‘to’ cannot introduce a benefactive argument, differently from preposition ‘à’ in French, and also, we add, from preposition ‘a’ in Italian. Consider the case of the benefactive argument that can be added to the argument structure of a transitive verb as in the Italian pairs in (13):

| a. | Farò una festa |

| I will do a party | |

| b. | Farò una festa ai bambini |

| I will do a party *‘to’ the kids/for the kids | |

| c. | Ho comprato un vestito |

| I bought a dress | |

| d. | Ho comprato un vestito ai bambini |

| I bought a dress *‘to’ the kids/for the kids |

The benefactive argument that is introduced by preposition ‘a’ in Italian, can be also added in English, but it is introduced by preposition ‘for’; ‘to’ is excluded in these cases, as indicated by the glosses in the examples in (13). The benefactive interpretation expresses a type of affectedness,[7] as in the case of the a-marker of left peripheral direct object topics hinted at above. Interestingly, to my knowledge, to-Topics do not seem to exist in English, as their appearance has never been documented.[8] Indeed, a similar affected status of the object is also recognized in the literature for the a-marked direct object in sentence internal position in Spanish. Consider, in this connection the following examples illustrating both physical and psychological affectedness (from Torrego 1998; von Heusinger 2008):

| a. | Golpearon a un extranjero |

| (they) beated ‘to’ a stranger | |

| b. | *Golpearon un extranjero |

| (they) beated a stranger | |

| c. | Odia a un vecino |

| (she) hates ‘to’ a neighbor | |

| d. | *Odia un vecino |

| (she) hates a neighbor |

A related component of a-marking may also be one expressing an empathic attitude of the speaker toward the preposed object (in the sense of Kuno and Kaburaki 1977).[9] So, an involvement component of the interpretation is to be understood as concerning both the object and the speaker. Thus, a feature [+a], suggesting affectedness/direct involvement in the event described by the verb, is proposed here as associated with preposition ‘a’ marking topics.

(11) and (12) can illustrate a diachronic path as the one described for Spanish in the previous section. However, in Spanish also a more grammaticalized step in a-marking may be operating. As Leonetti (2004) observes, a-marking on the direct object may not always be necessarily linked to topicality; ‘a’ can just be a marker of direct objects. Such a marker may thus be seen as a further step in the diachronic path, with ‘a’ being part of the Case-agreement system, as illustrated in (15) (Ledgeway et al. for closely related proposal):

|

In all cases ‘a’ contributes the affected/involvement interpretation described and dubbed [+a].

2.1.2 a-Marking as Case Marking: The Case of fare-a(/faire à) Causatives in Italian (and French)

Preposition ‘a’ as part of the Case-agreement system is also found in fare a causatives in Italian and /faire à causatives in French (Kayne 2004). In accord with the third step of a-marking described in (15), such ‘a’ is part of the extended projection of V, as such it is found in the ‘v’ spine. (16) reproduces the structure of a fare-a causative as described and discussed in Belletti (2017, updated in 2021):[10]

|

In (16) ‘a’ is indicated as the expression of a dative Case. Indeed, if the causee argument of a fare-a causative is expressed through a pronoun, such pronoun is realized in the form of a dative clitic, as in (17):

| Maria gli farà mangiare il gelato |

| Maria to-himcl will make eat the ice cream |

This is a most direct indication that ‘a’ is part of the Case-agreement system in the fare-a causative; in turn, this is also a clear indication that the a-marker of the left peripheral topic is not Case related.[11] In all cases of CLLD discussed above the resumptive clitic present in the clause following the left dislocated a-Topic is expressed in the form of an accusative clitic, both in Italian (in the limited cases in which a-Topics are possible) and in Spanish and in Balearic Catalan.

A last remark should be added at this point. The fact of being part of the Case-agreement system does not void the preposition of its interpretive [+a] feature. Hence, as noted in connection with (15), the a-marked direct object carries the relevant interpretation of affectedness/involvement. It must be noted now that the same holds true for the a-marked external argument of the vP in (16). Since Guasti’s (1993) analysis, the fact that the cause argument introduced by preposition ‘a’ carries an affected interpretation is generally recognized as one of the crucial characteristic properties of this argument in the causative construction.[12]

Thus, the picture concerning the a-marker looks coherent.

The following further observation completes the relevant overview of the status and role of the prepositional marker ‘a’. It is a well- known fact that a class of psych-verbs, e.g. the piacere (/like) class in Italian, expresses its Experiencer argument with an a-marked-DP. (18) provides one illustrative example:

| A Gianni piace la musica classica |

| to Gianni likes the music classical |

| (Gianni likes classical music) |

(18) is an instance of a so called quirky-subject, also found in several languages, as widely described in the literature in which the subject properties of the argument introduced by preposition ‘a’ in (18) are described (e.g. Belletti and Rizzi 1988 on Italian, Sigurdosson 2002 on Icelandic). If the experiencer argument of (18) is realized through a pronoun, the pronoun is the dative clitic gli(to-him) in Italian; whence the classical ‘quirky’ status of such an argument as a subject marked with a Case different from nominative (in a nominative-accusative language):

| Gli piace la musica classica |

| to-himcl likes the music classical |

| (He likes classical music) |

Once again, this Case manifestation is in sharp contrast with the Case properties of a-Topics noted above, which do not correspond to a dative, as the resumptive accusative clitic in CLLD indicates. This property is in turn consistent with the fact that the a-Topics, contrary to quirky-subjects of the type in (19), are not Case related and fill positions which are not related and are external to the Case zone(s) of the clause, i.e. the Topic position either in the left periphery or in the in the vP-periphery of the clause structure.

3 The Cartography of Children’s Inventions

3.1 Children’s a-Topics in the Left Periphery

As mentioned at various points in the previous sections, standard Italian is not a DOM language, in contrast with other Romance languages such as e.g. Spanish (and southern varieties of Italian as well). Furthermore, in contrast again with other Romance languages, a-Topics also have a very limited distribution (cfr. 8, 10 in 2.1). The previous sections have pointed out that diachronic evidence from Spanish clearly indicates that the process of a-marking started out in the left periphery and only in later stages involved the direct object in clause internal positions. The status of modern Balearic Catalan is especially revealing in this respect, as a-marking involves direct objects only (and optionally) when they are in the left peripheral topic position in CLLD. This may indeed be a characteristic pattern; the three stages illustrated in (11)-(12)-(15) thus schematize a diachronic path.

Evidence from children’s acquisition of CLLD in Italian has recently indicated (Belletti and Manetti 2019) that such pattern may also appear in language development during acquisition. In an experiment eliciting the relevant CLLD construction in which the left dislocated argument is the direct object, the (monolingual) Italian-speaking children investigated have made a wide use of a-Topics in their answers to the eliciting question, as illustrated by the production in (20) (e.g. Che cosa succede al mio amico, il pinguino?/What is happening to my friend, the penguin?):

| Il coniglio a i’ pinguino lo tocca | |

| The rabbit to the penguin him.Cl touches | |

| ‘The rabbit is touching the penguin’ | |

| (Adele 4;9 – Picture described by the child: Rabbit touching penguin)[13] | |

Children have thus shown the ability to ‘invent’ a construction by overextending it, since a-Topics are very limited and marginal in standard Italian, as pointed out in 2.1. Children’s use of a-Topics in Bellletti & Manetti’s results closely resembles the process of a-marking of direct objects illustrated in Section 2 for Spanish and more specifically for Balearic Catalan: in all of their productions a-marking only concerns the direct object when it fills the left peripheral Topic position. Never is the direct object marked with preposition ‘a’ in the clause internal position, thus clearly indicating that children are not treating Italian as a DOM language.[14] This systematic property of children’s productions is clearly illustrated by instances as the one in (21), in which in answering the elicitation question which concerned two direct objects involved in two different actions (Che cosa succede ai miei amici, la mucca e il pinguino?/What is happening to my friend the cow and the penguin?), the child realizes the first direct object in clause internal position in a SVO sentence, with no preposition ‘a’ present, and the second as a left dislocated a-marked a-Topic:

| La giraffa sta leccando la mucca, e il coniglio al pinguino lo sta grattando. |

| The giraffe is licking the cow and the rabbit to the penguin him-Cl is scratching |

| ‘The giraffe is licking the cow and the rabbit the penguin is scratching him.’ |

| (Omar, 5) |

These results indicate that there is a grammatical space of ‘invention’, that children are able to exploit. The reasons leading to this overuse of the otherwise very limited a-Topics in the target standard Italian, are discussed in detail in the reference quoted and will not be further developed in detail here. Suffice it to say that such marking with the introduction of the [+a] feature associated with preposition ‘a’ allows children to deal with the computation of a configuration of structural intervention expressed in terms of featural Relativized Minimality/fRM (Rizzi 1990, 2004; Starke 2001), which would be otherwise too hard, in fact impossible, for them to compute at the young ages tested (4–6).[15] Thus, under the pressure of the complexity of the computation, children exploit a grammatical option which is only rarely present in standard Italian. They show a capacity to somehow invent a construction by overextending it: their input may only contain the construction in a very limited way; in fact, productively, only with first and second person left dislocated personal pronouns; with lexical DPs, only marginally with object experiencers of psych-verbs (cfr. 2.1: 8–10). Children go beyond what they hear: their a-Topics are always lexical DPs of actional verbs. This is a very characteristic feature of children’s behavior during development. Interestingly, in this case children show that they are accessing the grammatical space that allows for this option and realize it in a way that is familiar from other languages. Considering the different status of preposition ‘to’ in English described in 2.1.1, the expectation is that young English-speaking children could not resort to a similar grammatical option, thus leading to the absence of ‘to-Topics’ in their productions in parallel experimental conditions. A new research question is generated by the results and considerations presented here, to be investigated and tested in future work.

Looking at the issue from the perspective of language change, it is possible that this overuse of a-Topics by the young Italian speaking children investigated may have revealed a potential change in progress in current standard Italian, possibly ultimately leading to DOM along the lines of the path illustrated by (11)-(12)-(15). Clearly, children are at the first stage (11), as shown by (21) and all the cases in which in a SVO sentence the direct object has never been marked with preposition ‘a’ by them. This remains as an open question; possibly in a few generations there will be an answer to it.[16]

3.2 Some Further Considerations on a-Topics and Animacy Based on Children’s Productions

Recent experimental results have added some new elements that may bear on the investigation of the value that preposition ‘a’ contributes for the interpretation of the a-Topic. Belletti and Manetti (2021) have manipulated the ‘animacy’ of the object topic. Among their aims was that of determining whether an inanimate object would qualify for a-marking, thus yielding a felicitous a-Topic for the children’s grammar.[17] The core of the results is that this is not the case. Some inanimate a-Topics were provided by children in their answer to the elicitation question (e.g.: che cosa succede a questa cosa, la macchina?/what happens to this thing, the car? Alla macchina, la lava/to the car, he washes it- M., 5;8, from Belletti and Manetti 2021: 14). However, this type of production happened to a very limited extent (12.5% of children’s answers). This is in sharp contrast to its overwhelming presence in the results from Belletti and Manetti (2019), where the direct object topic was always animate and a-Topics were produced in 74% of children’s CLLDs. As the authors conclude, these results indicate that animacy appears to play a role in the licensing of a-Topics (or whatever the proper feature is, with the proviso of footnote 15).[18] This conclusion is not surprising if the status of affected object characterizes the a-Topic, in a way also implying some involvement on the part of the speaker (i.e. the answering child in this case). Possibly, a special interpretation was attributed by the child to the inanimate a-marked object in the few cases in which it was expressed as an a-Topic in the left periphery (as is plausibly the case for the moving object ‘car’ in the example mentioned above). Be it as it may, it seems that a fair conclusion to draw is that the enrichment in the interpretation of the left dislocated direct object topic provided by preposition ‘a’ preferably, in fact almost exclusively, concerns animate objects.

4 Conclusion

We have reviewed here relevant data on the presence of preposition ‘a’ in the marking of a preposed direct object topic in CLLD, with special focus on Italian and comparative evidence from Old and Modern Spanish and Modern Balearic Catalan. We have compared these results with some experimental results from the acquisition of Italian by young (monolingual) children. A map of a-Topics and a-marked direct objects has emerged along the lines of the structural representations in (11)-(12)-(15), cartographically designed. The conclusion is that the invention that Italian speaking young children have produced in their realization of the left dislocated direct object topic in the form of an a-Topic follows the path indicated in the diachrony of Spanish and currently represented by Balearic Catalan, as described by Leonetti (2004) and Escandel-Vidal (2009), respectively. The a-Topic is indeed primarily a left peripheral topic, enriching the topic with some further feature, dubbed [+a] in our discussion, corresponding to its affected/involved interpretation, also implying some involvement in the event on the part of the speaker. Interestingly, the path individuated in (11)-(12)-(15), may be able to explicitly express the emergence of DOM, with a constrained clause internal interpretation of the a-marked direct object related to its topicality (i.e. in the Topic position of the vP-periphery, as in 12) or as a generalized (in this sense, grammaticalized) marking of direct objects (vP-internally, as in 15; on which see also Ledgeway et al. 2019). The interpretative content added by preposition ‘a’ has also been unveiled in the discussion, whose core remains constant in the various uses of this same preposition, such as its appearance in Italian/French causatives and in benefactive arguments (Kayne 2004, on French), and in its tendential absence on inanimate a-Topics in children’s productions. A coherent map emerges through this overview, that may guide in the fine characterization of such a core crosslinguistic phenomenon in which a direct object is in fact introduced by a preposition, in Italian/Romance typically preposition ‘a’.

References

Anderson, Stephen. 1987. Objects (direct and not so direct) in English and elsewhere. In Caroline Dunca-Rose & Theo Vennemann (eds.), On language. A festschrift for Robert P. Stockwell, 287–314. London and New York: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Belletti, Adriana. 2004. Aspects of the low IP area. In Luigi Rizzi (ed.), The structure of CP and IP. The cartography of syntactic structures, vol. 2, 16–51. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780195159486.003.0002Search in Google Scholar

Belletti, Adriana. 2017. Labeling (Romance) causatives. In Enoch Aboh, Eric Haeberli, Genoveva Puskas & Manuela Shonenberg (eds.), Elements of comparative syntax: Theory and description, 13–46. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter Mouton.10.1515/9781501504037-002Search in Google Scholar

Belletti, Adriana. 2018a. On a-marking of object topics in the Italian left periphery. In Roberto Petrosino, Pietro Carlo Cerrone & Harry van der Hulst (eds.), Beyond the veil of Maya. From sounds to structures, 445–466. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.10.1515/9781501506734-016Search in Google Scholar

Belletti, Adriana. 2018b. Objects and subjects in the left periphery: The case of a-topics. In Grimaldi Mirko, Rosangela Lai, Ludovico Franco & Benedetta Baldi (eds.), Structuring variation in Romance linguistics and beyond, 57–72. Linguistik Aktuell/Linguistics Today [LA]. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/la.252.03belSearch in Google Scholar

Belletti, Adriana. 2021. Ways of smuggling in syntactic derivations. In Adriana Belletti & Chris Collins (eds.), Smuggling in syntax, 13–37. New York: OUP.10.1093/oso/9780197509869.003.0002Search in Google Scholar

Belletti, Adriana & Claudia Manetti. 2019. Topics and passives in Italian-speaking children and adults. Language Acquisition 26(2). 153–182. https://doi.org/10.1080/10489223.2018.1508465.Search in Google Scholar

Belletti, Adriana & Claudia Manetti. 2021. (a)Topics and animacy. Glossa 6. 1. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780197509869.003.0001.Search in Google Scholar

Belletti, Adriana & Luigi Rizzi. 1988. Psych-verbs and Th-theory. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 6. 291–352. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00133902.Search in Google Scholar

Belletti, Adriana, Naama Friedmann, Dominique Brunato & Luigi Rizzi. 2012. Does gender make a difference? Comparing the effect of gender on children’s comprehension of relative clauses in Hebrew and Italian. Lingua 122(10). 1053–1069. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2012.02.007.Search in Google Scholar

Benincà, Paola. 1986. Il lato sinistro della frase italiana. ATI Journal 47. 57–85.Search in Google Scholar

Berretta, Monica. 1989. Sulla presenza dell’accusativo preposizionale nell’italiano settentrionale: note tipologiche. Vox Romanica 48. 13–37.Search in Google Scholar

Bossong, Georg. 1991. Differential object marking in Romance and beyond. In Dieter Wanner & Dougla A. Kibbe (eds.), New analyses in Romance linguistics. Selected papers from the XVIII linguistic symposium on Romance languages 1988, 143–170. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/cilt.69.14bosSearch in Google Scholar

Brugè, Laura & Gerhard Brugger. 1996. On the accusative a in Spanish. Probus 8. 1–51.10.1515/prbs.1996.8.1.1Search in Google Scholar

Collins, Chris. 2021. A smuggling approach to the dative alternation. In Adriana Belletti & Chris Collins (eds.), Smuggling in syntax, 96–107. New York: OUP.10.1093/oso/9780197509869.003.0005Search in Google Scholar

D’Alessandro, Roberta. 2021. Syntactic change in contact. Annual Review of Linguistics 7(7). 309–328. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-linguistics-011619-030311.Search in Google Scholar

Escandell-Vidal, Victoria. 2009. Differential object marking and topicality: The case of Balearic Catalan. Studies in Language 33(4). 832–885. https://doi.org/10.1075/sl.33.4.02esc.Search in Google Scholar

Friedmann, Naama, Adriana Belletti & Luigi Rizzi. 2009. Relativized relatives: Types of intervention in the acquisition of A-bar dependencies. Lingua 119. 67–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2008.09.002.Search in Google Scholar

Guardiano, Cristina. 2010. L’oggetto diretto preposizionale in siciliano. Una breve rassegna e qualche domanda. In Jacopo Garzonio (ed.), Studi sui dialetti della Sicilia, 83–101. Padua: Unipress.Search in Google Scholar

Guasti, Maria Teresa. 1993. Causative and perception verbs. A comparative study. Torino: Rosenberg & Sellier.Search in Google Scholar

von Heusinger, Klaus. 2008. Verbal semantics and the diachronic development of differential object marking in Spanish. Probus 20(1). 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1515/probus.2008.001.Search in Google Scholar

Iemmolo, Giorgio. 2010. Topicality and differential object marking: Evidence from Romance and beyond. Studies in Language 34(2). 239–272. https://doi.org/10.1075/sl.34.2.01iem.Search in Google Scholar

Kayne, Richard. 2004. Prepositions as probes. In Adriana Belletti (ed.), Structures and beyond – The cartography of syntactic structures, vol. 3, 192–212. New York: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195179163.003.0005Search in Google Scholar

Kuno, Susumu & Etsuko Kaburaki. 1977. Empathy and syntax. Linguistic Inquiry 8(4). 627–672. https://doi.org/10.1002/chin.197752397.Search in Google Scholar

Laca, Brenda. 1987. Sobre el uso del acusativo preposicional en espanol. In Pensado Carmen (ed.), El complement directo preposicional, 61–91. Madrid: Viso.10.1515/9783112418345-036Search in Google Scholar

Laca, Brenda. 2006. El objeto directo. La marcación proposicional. In Sintaxis historica del español. Primera parte: La frase verbal, vol. 1, C. Company (dir.), 423–475. Mexico: Fondo de cultura económica/Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.Search in Google Scholar

Ledgeway, Adam. forthcoming. Parametric variation in differential object marking in the dialects of Italy. Paper presented at The workshop on DOM, Paris, Fall 2019. ms: University of Cambridge.Search in Google Scholar

Ledgeway, Adam, Norma Schifano & Silvestri Giuseppina. 2019. Differential object marking and the properties of D in the dialects of the extreme south of Italy. Glossa: A Journal of General Linguistics 4(1). 1–25. https://doi.org/10.5334/gjgl.569.Search in Google Scholar

Leonetti, Manuel. 2004. Specificity and differential object marking in Spanish. Catalan Journal of Linguistics 3. 75–114. https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/catjl.106.Search in Google Scholar

Lightfoot, David. 1999. The development of language: Acquisition, change, and evolution. Oxford: Blackwell.Search in Google Scholar

Manzini, Maria Rita & Ludovico Franco. 2016. Goal and DOM datives. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 34. 197–240.10.1007/s11049-015-9303-ySearch in Google Scholar

Rizzi, Luigi. 1990. Relativized minimality. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.Search in Google Scholar

Rizzi, Luigi. 1997. The fine structure of the left periphery. In Liliane Haegeman (ed.), Elements of grammar, 281–337. Dordrecht: Kluwer.10.1007/978-94-011-5420-8_7Search in Google Scholar

Rizzi, Luigi. 2004. Locality and the left periphery. In Adriana Belletti (ed.), Structures and beyond: The cartography of syntactic structure, vol. 3, 223–251. New York: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780195171976.003.0008Search in Google Scholar

Rizzi, Luigi & Giuliano Bocci. 2017. Left periphery of the clause: Primarily illustrated for Italian. In Martin Everaert & Henk C. Van Riemsdijk (eds.), The Wiley Blackwell companion to syntax, 1–30. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.10.1002/9781118358733.wbsyncom104Search in Google Scholar

Sigurdsson, Halldor A. 2002. To be an oblique subject: Russian vs. Icelandic. Natural Languages and Linguistic Theory 20(4). 691–724.10.1023/A:1020445016498Search in Google Scholar

Starke, Michal. 2001. Move dissolves into merge: A theory of locality. Geneva: University of Geneva PhD dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Torrego, Esther. 1998. The dependencies of objects. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.10.7551/mitpress/2337.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Wood, Jim & Raffaella Zanuttini. 2018. Datives, data and dialect syntax in American English. Glossa: A Journal of General Linguistics 3(1). 1–22. https://doi.org/10.5334/gjgl.527.Search in Google Scholar

© 2022 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Original Articles

- Introduction: On the Role of Romance in Cartographic Studies

- a-Topics in Italian/Romance and the Cartography of Children’s Inventions

- Long Subject Questions in French: An Insight into the Left Periphery of Selected CPs

- On Two Sub-projections of the Nominal Extended Projection: Some Romance Evidence

- The Syntactic Encoding of Conventional Implicatures in Sicilian Polar Questions

- On French Est-ce que Yes/No Questions and Related Constructions

- Criterial V2: ModP as a Locus of Microvariation in Swiss Romansh Varieties

- On the Raising of the Finite Main Verb in Angolan Portuguese and in Mozambican Portuguese: Cartographic Hierarchies, Microvariation and the Use of Adverbs as Diagnostics for Movement

- Microvariation and Change in the Romance Left Periphery

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Original Articles

- Introduction: On the Role of Romance in Cartographic Studies

- a-Topics in Italian/Romance and the Cartography of Children’s Inventions

- Long Subject Questions in French: An Insight into the Left Periphery of Selected CPs

- On Two Sub-projections of the Nominal Extended Projection: Some Romance Evidence

- The Syntactic Encoding of Conventional Implicatures in Sicilian Polar Questions

- On French Est-ce que Yes/No Questions and Related Constructions

- Criterial V2: ModP as a Locus of Microvariation in Swiss Romansh Varieties

- On the Raising of the Finite Main Verb in Angolan Portuguese and in Mozambican Portuguese: Cartographic Hierarchies, Microvariation and the Use of Adverbs as Diagnostics for Movement

- Microvariation and Change in the Romance Left Periphery