Abstract

Odisha, a state located in Eastern India, is renowned for its unique and indigenous folk performances. These performances are not merely sources of entertainment but repositories of the region’s culture, tradition, and heritage. Recognizing their culture significance, individuals and communities have taken initiatives to promote and preserve them through the social media platforms. Our article explores selected social media handles across three platforms, namely, YouTube, Facebook, and Instagram, to examine their role in preserving and promoting seven folk performances of Odisha: Odissi, Pala, Gotipua, Kandhei Nacha, Chaiti Ghoda, Ranapa, and Dasakathia. Through a qualitative content analysis of the selected social media handles and their content on folk performances, the study reveals that Odissi and Pala have strong visibility and engagement on social media, while the other five performances – Gotipua, Kandhei Nacha, Chaiti Ghoda, Ranapa, and Dasakathia – have limited presence due to a decline in their physical practice and performances. Among the platforms, YouTube emerges as the most active in terms of documentation and promotion, while Facebook and Instagram demonstrated relatively lower engagement. Furthermore, the study finds that although these platforms offer numerous features, many of these are not actively utilized by the reviewed accounts. This paper offers recommendations for a more systematic and strategic use of digital media to ensure the long-term visibility and sustainability of these folk performances. This research contributes to the fields of folklore study, cultural studies, and media studies by highlighting the potential of digital platforms in promoting and preserving regional cultural assets in a rapidly evolving digital age.

1 Introduction

Odisha as a state is deeply rooted in tradition and heritage. The region encompasses a rich tapestry of folk performances such as Odissi, Pala, Gotipua, Kandhei Nacha, Chaiti Ghoda Naacha, Ranapa, and Dasakathia. It is important to recognize the significance of folk media such as folk art, music, and dance (Kumar 2012). By focusing on the impact of folk music, dance, and epic or ballad recitation on society and community, it becomes evident that folk performances play a critical role in shaping regional identity and cultural continuity (Kumar 2012). These performances are not merely sources of entertainment; rather, they reflect the cultural and traditional essence of the region (Das and Mahapatra 1979). Whether through the rhythmic movements in Odissi, the narrative sequences of epics in Pala, or the acrobatic stilt dances in Ranapa, such performances transmit cultural values and historical narratives across generations (Das and Mahapatra 1979). However, in the face of rapid technological advancements and urbanization, traditional art forms are under threat. Many individuals are turning towards digital entertainment, leading to the marginalization of indigenous practices. Notably, the rise of technology challenges conventional preservation methods, which largely rely on physical archiving and museum displays. These methods, while valuable, often fail to capture the experiential and performative dimensions of cultural heritage (Ertürk 2020). Furthermore, globalization has contributed to the erosion of traditional identities and has catalyzed various cultural transformations (Heath et al. 2007; Yeganeh 2024). As a result, many folk traditions and performances face gradual decline (Yoshida et al. 2011). Given this context, cultural preservation becomes imperative, particularly with respect to safeguarding rituals, customs, and performing arts (Oladokun et al. 2024). Although conventional approaches such as museums and historical records play a role in conservation, they are increasingly inadequate in responding to the pace and nature of contemporary cultural change (Furferi et al. 2024).

In response, digital media has emerged as a critical tool in the preservation of intangible cultural heritage. Through the internet, communities now have unprecedented opportunities to archive, document, and disseminate cultural practices. Digital preservation, especially within museum and archival contexts, demands strategic planning and institutional engagement to ensure sustainability (Ertürk 2020). Digital technologies foster community involvement and can recreate traditional settings in immersive formats, thus serving as educational and engagement tools (Liu 2022). As the internet has reshaped communication, it has also facilitated global interconnectivity, making space for interactive platforms like social media (Slumkoski 2012). Collaborative approaches enabled by such platforms now play a pivotal role in addressing the complex challenges of cultural preservation (Liu 2022). Social media, especially Facebook, Instagram, and YouTube, has become an indispensable medium through which users can share, consume, and co-create cultural content globally (Trillo et al. 2020; Slumkoski 2012). Similarly, cultural engagement through posts and targeted outreach on platforms like Facebook has proven valuable in keeping heritage relevant and participatory (Susanti and Koswara 2017).

Taking the aforementioned concerns, our article examines selected social media handles across three platforms – YouTube, Facebook, and Instagram – to examine their role in preserving and promoting seven folk performances of Odisha: Odissi, Pala, Gotipua, Kandhei Nacha, Chaiti Ghoda, Ranapa, and Dasakathia. These seven folk performances were selected because they are culturally, historically, and spiritually rooted in Odisha and hold immense significance for its people and heritage. Among them, Odissi and Pala have gained widespread recognition and are experiencing increasing popularity. However, the remaining five have witnessed a noticeable decline in public interest in recent years. This study aims to explore how three social media platforms – YouTube, Facebook, and Instagram – are contributing to the promotion and preservation of these folk performances.

The selection of social media handles on YouTube, Facebook, and Instagram was based on a combination of content relevance and audience engagement. The first priority was first given to accounts and channels that are dedicated exclusively to uploading content related to the specific folk performances selected for this study. Following this, we also included handles that have a good number of subscribers, followers, and members and upload content on performances selected for our study along with other content. Additionally, individual videos, posts, pages, and reels that demonstrated significant audience engagement including likes, shares, comments, and views were also considered. In cases where certain performances were underrepresented across social media platforms, we selected content based on availability, even if it did not meet the earlier criteria. The process of identifying relevant social media handles for each folk performance was carried out using a keyword-based search strategy. Keywords included the names of the performances such as “Odissi dance,” “Odia Pala,” “Gotipua,” “Kandhei Nacha,” “Chaiti Ghoda,” “Ranapa,” and “Dasakathia,” as well as related terms like “academy,” “artists,” and “traditional dance of Odisha.” This method was applied across YouTube, Facebook, and Instagram to locate content relevant to the selected folk performances.

2 Odisha’s Cultural Legacy: Understanding the Selected Folk Performances of the State

In this article, we have taken the folk performances of Pala, Odissi, Gotipua, Kandhei Nacha, Chaiti Ghoda, Ranapa, and Dasakathia. To begin with, Pala is a mix of elements of classical Odia music, theatre, and poetry in Odia and Sanskrit. The art form originated in order to bring unison between the Hindus and Muslims during the Mughal era (Patra 2017). A typical Pala group has about five to seven members. The leader of the group is called Mukhya Gayaka. The secondary performer called Sri Palia joins the leader by repeating stanzas after him. The Bayak plays the Mrudangam. Baithaki Pala is the kind of performance where performers sit and perform, whereas Thia Pala is the kind where the performers stand on the stage to perform. The performance holds considerable cultural value as it draws from Odisha’s traditional narratives and mythologies (Patra 2017). It is often viewed as a spiritual medium that facilitates a connection with the divine (Patra 2017). Initially, the performance was based mostly on scenes from the epics of Mahabharata and Ramayana. However, in recent times, the performance has evolved to include themes such as spirituality and moral lessons (Sahoo 2019). Moving on, Odissi is an internationally renowned classical dance form, dating back to the temples of Odisha in the second century BCE. Odissi as a performance is believed to be heavily influenced by the Tandava Nritya of Lord Shiva (Das and Mahapatra 1979). Its costumes are aesthetically rich and contribute significantly to the storytelling aspect of the performance (Kothari 2022). The dancers use intricate hand gestures to express themselves while narrating mythological tales and stories (Kothari 2022). Initially, the dance form was performed exclusively by women. Over time, it has evolved to become a performance space for male dancers as well (Banerji 2019).

Next, the dance form of Gotipua is an age-old tradition in Odisha. The word Gotipua is derived from the words goti, meaning single, and pua, meaning boy. The dance is performed by young boys who are dressed as women. The dance involves rigorous acrobatic practice in the village clubs (Mondal 2018). The performers wear traditional silk dhoti, a waist belt, and their hair is styled in a bun, which enhances the visual presentation (Mondal 2018). The theme of Gotipua performance is centered around the divine tales of Lord Krishna and Lord Jagannath. Furthermore, the performance emphasizes flexibility and balance with as much energy as possible (Tarannum 2016). Although it was originally performed as a devotional offering, it has since evolved into a widely recognized folk dance that reflects Odisha’s cultural richness (Tarannum 2016). Culturally, the performance serves as a bridge that connects younger generations to traditional values and spiritual heritage. Apart from upholding the religious fabric of Odisha, the art form also showcases the versatile nature of the state’s artistic traditions (Mondal 2018). Chaiti Ghoda Nacha, another notable folk performance, is often linked with the worship of Goddess Vasuli. It originated from the Keuta community of fishermen in the coastal regions of Odisha. Traditionally, it is held for an entire month, beginning from Chaitra Purnima to Baisakha Purnima. Performers adorn themselves in vibrantly colored attire complemented by ornamental jewelry, contributing to the ceremonial visuality of the event. The central figure, representing the horse, is often dressed in a large, decorative horse mannequin (Mohapatra 2017). The rhythm of the performance is accentuated by drums and other instruments (Mohapatra 2017). Symbolically, the horse represents strength, valor, and new beginnings (Panda 2024). Culturally, this performance celebrates communal unity and marks seasonal transitions (Panda 2024). Similarly, Kandhei Nacha (dancing of the dolls) is a rod puppetry performance native to the Jhara community of Ganjam. It is typically staged during festivals like Makar Sankranti and Rath Yatra. The puppets are made of intricately carved wood, dressed in bright embroidered costumes and jewelry. They are dressed in brightly colored embroidered costumes and adorned with jewelry to enhance their visual appeal. The puppeteers wear traditional clothing, jewelry, and turbans to complement the performance setting (Mohapatra 2017). While narrating mythological stories, they manipulate the puppets with their hands (Mohapatra 2017). The performance promotes communal togetherness and reinforces collective cultural memory (Mohapatra 2017). It also strengthens the connection between art, religion, culture, and storytelling (Samantaray 2014). Following this, Ranapa, which translates to “battle dance,” is a folk performance that originated to celebrate courage and heroism. Rooted in the villages of Ganjam, it is typically performed during Dussehra. Performers are clad in traditional dhoti and turbans, accompanied by ornamental accessories. The dance features shields and swords that the dancers display with flair. The vigorous and acrobatic movements reflect both physical and mental strength (Sahoo 2019). The performance functions not only as a display of strength and agility but also as a ritualistic homage to spiritual and cultural ideals (Satpathy 2016). It is a communal activity that encourages youth to reconnect with ancestral heritage(Satpathy 2016). Lastly, Dasakathia originated in the Ganjam district and began as a storytelling tradition. Performers travel across villages narrating mythological tales using music, dance, and dialogue (Sahoo 2019). They dress in elaborate attire complemented by ornamental jewelry, lending a regal appearance to the performance. Cymbals and flutes are carried and played during the performance. Dancers stomp their feet rhythmically and use unique hand gestures that coordinate with the mythological background music (Satpathy 2016). The themes are based on moral and religious narratives, focusing on good versus evil and spiritual devotion (Satpathy 2016). Culturally, it serves as a pedagogical medium that transmits religious and ethical values to younger audiences. Since it is performed in local dialects, it contributes to linguistic preservation and cultural continuity (Satpathy 2016). The performance illuminates’ spiritual beliefs, social values, and Odisha’s deep cultural roots (Satpathy 2016).

We have attached a table below with the brief description of the folk performances selected for our study.

| Folk performances | Description |

|

|

|

| Pala | The Pala performance in Odisha originated during the Mughal era as a medium to unite the Hindus and Muslims. The folk performance uses negligible stagecraft while the performers wear props and costumes. One Pala performer group consists of five to seven members. The performers narrate stories taken from epics and scriptures. |

| Odissi | Odissi is the oldest surviving classical dance form, known for its poised postures, expressive facial movements, elaborate costumes and makeup. It features intricate hand gestures or mudras and is mostly dedicated to Lord Jagannath. Odissi is distinct as it introduced the concept of Tribhangi or dividing the body into three bends via visual appearance. |

| Gotipua | Originating from the Devadasi tradition, Gotipua is a traditional dance in which young boys are decorated like girls, dedicating their art form to the deities. The folk performance holds deep cultural significance by narrating stories from epics such as Ramayana and Mahabharata. |

| Chaiti Ghoda Nacha | It is a traditional folk dance that originated with the fishermen community or the Keutas. It is closely associated with Goddess Baseli. Performed during the month of Chaitra Purnima, it features men dressed as horses to narrate mythological stories, reflecting their cultural values. |

| Kandhei Nacha | Kandhei Naacha is the conventional rod puppetry practiced by the Jhara community of Keonjhar. It is known for its storytelling with the help of vibrant colored costumes. It features live music and dialogues that enhance the dramatic effect and bring the puppets to life. |

| Ranapa | Ranapa is the unique form of martial art that started in Ganjam, showcasing the bravery and valor of the warriors of the Ashoka reign. The performers use stilts or rods during the performance to add a visually striking element to its acrobatic movements. |

| Dasakathia | It is a traditional folk performance that originated in the Ganjam district of Odisha, emerging from the friction between Hindu and Muslim. It initially used to be performed by the low caste Hindu community. The performers use a specific wooden instrument called kathi which enhances the musical appeal. |

3 Cultural Preservation in the Digital Age: The Role of Specific Social Media Platforms in Preserving Selected Folk Performances of Odisha

A good number of Odissi dance videos is available on YouTube. Two notable channels solely dedicated to Odissi are “Vishnu Tattva Das Odissi Vilas” (3.5k subscribers, 155+ videos) and “GKMC[1] Research Centre” (6.89k subscribers, 864+ videos). The channel “Odissi Vilas” features recorded performances by legends of Odissi dance like Guru Kelucharan Mohapatra, Padma Shri Sanjukta Panigrahi, and Vishnu Tattva Das, whereas “GKMC” shares a wide range of content including Odissi performances, dance festivals, tutorials, and live streams. A notable upload on “Odissi Vilas” is “Mangala Charan – Namami” (46k views, 618 likes), showcasing the performance of Guru Kelucharan Mohapatra dancing to the tunes of classic Odissi instrumental music. It has received heartfelt comments such as, “Koti Koti Pranam to great legendary Odissi dancer Guru Kelucharan Mohapatra” and “Beautiful Namami in Raag Desh!!! The spectacular grace in Guruji’s movements shines through even this grainy video.” Similarly, GKMC’s video “Shrita Kamala Kucha Mandala – Gita Govinda” (80k views, 1.4k likes), featuring Sujata Mohapatra, presents a classical rendition praising Lord Krishna as the supreme creator. The video has been praised with comments like, “This is the best version of Shrita Kamala that I prefer to listen! And Sujata ma’am is as usual next level with her artistry and expression!”. A screenshot of an Odissi performance (Figure 1) and a comment (Figure 2) are provided below.

A screenshot taken from the YouTube video of Sujata Mohapatra’s Odissi performance on “Shrita Kamala Kucha Mandala” on the YouTube channel “GKCMC Odissi Research Centre.”

A screenshot of a particular comment taken from the YouTube video of Sujata Mohapatra’s Odissi performance on “Shrita Kamala Kucha Mandala” on the YouTube channel “GKCMC Odissi Research Centre.”

Despite the limited number of uploads on “Odissi Vilas,” the channel has gained a good number of subscribers. This can be attributed to the rare and invaluable recordings of legendary Odissi performers that are true treasures of the classical dance world. This trend reflects viewers’ reverence and appreciation for authentic, classical Odissi content. Nevertheless, the channel has become inactive in recent times, as the number of uploads has decreased. If this pattern continues, viewer interest may gradually decline. In contrast, “GKMC,” although created 4 years after “Odissi Vilas,” is more dynamic in its upload and engagement. Furthermore, channels like “SRJAN”[2] (5.24k subscribers, 352+ videos) and “Orissa Dance Academy” (2.26k subscribers, 120+ videos), which are run by dancing schools of Odisha, are very active in promoting Odissi performances through their platforms.

The Odissi performances on these channels reflect a blend of traditional mythological themes and contemporary societal expressions. Popular videos from “SRJAN” include “Ardhanarishwara” (24k+ views, 656 likes) and “Bhagabati Strotam” (16k+ views, 428 likes). The YouTube video “Ardhanarishwara” features a significant concept represented in Odissi dance as a symbol of the communion of the divine Shiva and Parvati. It has comments such as, “Brilliant choreography, as the music… both are my favorite dancers!!!” Meanwhile, the “Bhagabati Strotam” performance features a devotional hymn dedicated to Goddess Durga and showcases the victory over evil forces. A screenshot of an Odissi dance performance (Figure 3) and a comment (Figure 4) are provided below.

A screenshot taken from the YouTube Odissi video “Ardhanarishwara” on the “SRJAN” YouTube channel.

A screenshot of a comment on the YouTube Odissi video “Ardhanarishwara” on the “SRJAN” YouTube channel.

In addition to these, there are some popular channels like “Soulful Odisha” (40.6k subscribers, 595+ videos) and “Life & Time Odisha” (204k subscribers, 633+ videos) that upload Odissi performances along with other content. Among the most-watched Odissi dance videos is “Trahi Durga|Indian Classical Dance|Odissi|Nrutya Naivaidya” on Soulful Odisha (138k views, 3k likes) which features an Odissi performance symbolic of the strength of Goddess Durga, particularly emphasizing her role as a protector and highlighting her divine feminine strength. Noteworthy comments include “Awesome, just awesome. The self-decapitation scene is stunning.” Another such video titled “Chitra-Vitanam” by Guru Ratikant Mahapatra and Team Srjan on “Life & Time Odisha” (13k views, 307 likes) showcases an Odissi performance during Odisha Parba 2023,[3] emphasizing rhythmic style and choreography. Some significant viewer comments on these videos include expressions of cultural pride and emotional connection to the art form, such as “There’s a sense of pride watching a gorgeous dance form like this… May it preserve with us.” Likes and comments on these videos are mostly under 1,000 in number, which suggests that while people are watching the content, they are not actively engaging with it. This observation indicates a gap between viewership and viewer interaction on these channels. On the other hand, individual contemporary Odissi dancers’ channels like “Saswat Joshi” (275k subscribers) and “Tulika Tripathy” (25.2k subscribers) maintain very engaging and vibrant content. Notable videos like “Bande Utkal Janani” uploaded on “Saswat Joshi” and “Garaj Garaj” uploaded on “Tulika Tripathy” enjoy thousands of views and hundreds of likes. A screenshot of an Odissi performance (Figure 5) and a comment (Figure 6) are provided below.

A screenshot taken from the Youtube video “Chitra-Vaitnam…” on Life and Time Odisha.

A screenshot of a comment under the YouTube video “Chaitra Vaitnam…”

Moreover, there are some Facebook pages, groups, and personal accounts which take the initiative to promote and preserve Odissi through their content uploads. For instance, the public group “ODISSI” (21.2k members) posts diverse content on Odissi such as news articles, event updates, and posts from related pages. Similarly, “Odissi International” (7.9k members) mainly updates about the Odissi International Dance Festival and uploads photos and reels from the festival. Additionally, “Odissi Classical Dance Group in Houston” (1.7k members) is a well-organized group with clear rules, where members share performances and Odissi academy information. Another group, “Odissi Dancers Page” (2.6k members), has gained popularity recently, with more than 30 new members joining in the week before May 12, 2025. Members of this group post dance school advertisements, YouTube links, and event updates.

Elsewhere, the Facebook page “Nrutya Naivedya” (6.9k followers) actively engages its audience through frequent posts, while “Odissi Dance Creation” (5.6k followers) shares reels, photos, and long videos with brief captions and hashtags. The highest-viewed reel from “Odissi Dance Creation” is “Barshanuraga by the artists of Soor Mandir, Cuttack,” which achieved 31k views. Comments such as “creativity at its peak” show that the audience is interested in watching the performance. A screenshot of “Barshanuraga” video (Figure 7) and a comment (Figure 8) are given below.

A screenshot of “Barshanuraga” video on the YouTube channel “Odissi Dance Creation.”

A screenshot of the comment on the “Barshanuraga” video on the YouTube channel “Odissi Dance Creation.”

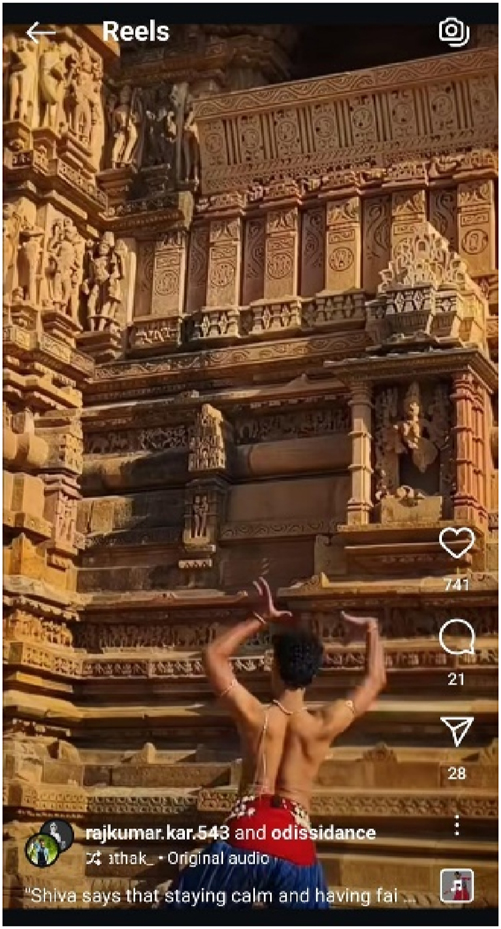

Likewise, certain public Instagram accounts completely dedicated to authentic Odissi dance content, such as “Odissidance” (3,786 followers), “Odissidancecreation” (2,033 followers), and “Gkcmorc” (1,199 followers), regularly upload visually attractive posts and reels of Odissi performances presented during various festivals and events. For instance, the account “Odissidance” features striking monochromatic-filtered photographs of different performers to enhance viewer engagement. A popular reel on this account titled “Shiva says that staying calm and having faith are often all you need to do to find peace” garnered 25.8k views, 740 likes, 21 comments, and 28 shares. However, despite featuring a substantial number of authentic reels and photos, these accounts have relatively low follower counts and less audience engagement metrics. A screenshot of an Instagram reel (Figure 9) and a comment (Figure 10) are provided below.

A screenshot of an Instagram reel “Shiava says that staying calm…” on the Instagram channel “odissidance.”

A screenshot of a comment on the Instagram reel “Shiava says that staying calm…” on the Instagram channel “odissidance.”

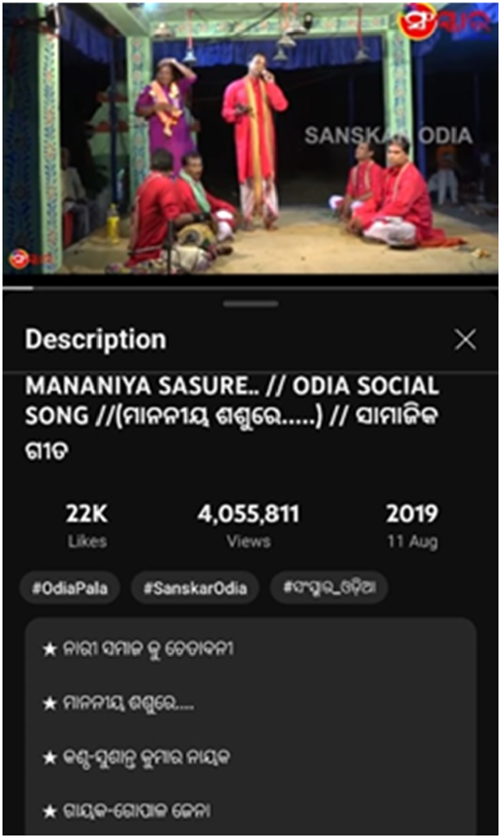

In addition to YouTube and Instagram, other digital platforms have also played a significant role in promoting traditional art forms such as Pala. Channels like “PALA Sanskar Odia TV” (276k subscribers and 3,100+ videos), “Ashok Creation” (139k subscribers and 643+ videos), “Shree Jagannath Pala Research” (79k subscribers and 2.6k videos), and “Siddharth Bhakti” (962k subscribers and 18k+ videos) actively promote Pala performances by uploading a variety of content, including full-length performances, shorts, live streams, and interviews. Notably, some of these channels, such as “PALA Sanskar Odia TV” and “Siddharth Bhakti,” offer a membership option for just Rs. 59 and Rs. 89 per month respectively. The introduction of low-cost memberships serves as an effective strategy to attract a wider audience. Among the notable videos on these platforms are “Mananiya Sasure” (4 million views, 23k likes), “Odia Pala||Radha Janma||Gayak Ratna||Prabhat Sahu” (77k views, 3.1k likes), and “ ”/“Bibhisana Janma” (73k+ views, 482 likes). These videos beautifully portray male artists dressed in female attire, using traditional instruments to act and narrate mythological tales in a detailed and engaging manner. These narratives are based on mythological tales from epics such as the Ramayana and Mahabharata. A screenshot of a Pala performance Youtube video (Figure 11) and a comment (Figure 12) are demonstrated below.

”/“Bibhisana Janma” (73k+ views, 482 likes). These videos beautifully portray male artists dressed in female attire, using traditional instruments to act and narrate mythological tales in a detailed and engaging manner. These narratives are based on mythological tales from epics such as the Ramayana and Mahabharata. A screenshot of a Pala performance Youtube video (Figure 11) and a comment (Figure 12) are demonstrated below.

A screenshot taken from the YouTube video “MANANIYA SASURE…” on the YouTube channel “Sanskar TV Odia.”

A screenshot of a comment on the YouTube video “MANANIYA SASURE…” on the YouTube channel “Sanskar TV Odia.”

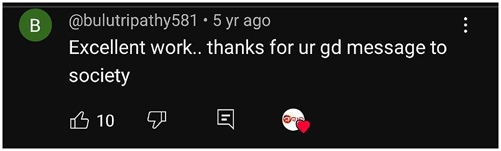

The presence of Pala content on Facebook remains limited and scattered. Several Facebook pages and groups, both older and recently created, such as “ODIA PALA” (51k followers), “Odia Pala Official” (77 followers), “Odisha Tourism” (276k followers), and “Satyanarayan Pala Sangathan” (667 members), attempt to promote Pala through short reels and posts. Among these, “ODIA PALA” stands out as the most active page, with a consistent posting frequency. For instance, its recent reel titled “Ajira Anuchinta” received 669k views, 10.9k likes, 33 comments, and 813 shares. This particular reel narrates a social message about the marginalization of women in families, using mythological tales of Goddess Durga to emphasize female strength. However, the activity levels of the other pages remain moderate, and their posts receive limited engagement in terms of likes, shares, and comments. On Instagram, although some reels and photos related to Pala performances are available, their presence is very scattered. Instagram accounts such as “bhavya_odisha” (1,955 followers) and “odia-badi-pala” (13 followers) have uploaded a few posts, but audience engagement remains low. Nevertheless, one particular reel titled “Have you ever watched a Pala live?” uploaded by the account “_glowonly” achieved a significant level of audience response (47.8k views, 5,791 likes, 167 comments, and 1,094 shares). This reel is distinctive in that it provides an informative segment explaining the historical and cultural context of the Pala tradition in Odisha. A screenshot of an Instagram reel (Figure 13) and a comment (Figure 14) are presented below.

A screenshot taken from a reel addressing Pala performance on the Instagram account “_glowonly.”

A screenshot of a comment taken from the comment section of the Instagram reel addressing the Pala performance on the Instagram account “_glowup.”

In the case of Gotipua, the visibility on digital space is even more limited. Currently, only one YouTube channel titled “Gotipua Dance Odisha” is solely dedicated to this art form. Despite being created nearly a decade ago, the channel has only 101 subscribers and 18 uploaded videos. At the time of writing, the most viewed video on this channel has received just 618 views. Some popular videos and reels of Gotipua performances are uploaded on other more established YouTube channels that are not exclusively dedicated to Gotipua. For instance, videos such as “Gotipua Dance by Kamal Nritya Aangan” (12k views, 1.1k likes), “Gotipua Dance Performance by Nakshyatra Gurukul” (36k views, 719 likes), “Gotipua Dance – Odisha Dance Academy – Dhauli Kalinga Mahotsav” (15k views, 189 likes), and “Gotipua Dance Performance|Orissa Dance Academy” (112k views, 1k likes) are found on platforms like JollyGul, Soulful Odisha, Odisha Live, and TEDx Talks, respectively. In these performances, young Gotipua artists, often boys dressed in female attire, perform with acrobatic and rhythmic poses that narrate mythological stories.

The video “Gotipua Dance Performance by Nakshyatra Gurukul” on “Soulful Odisha” is particularly notable for highlighting key elements of the Gotipua tradition, such as the opening Vandana, the dynamic Pallavi, and expressive Abhinaya sequences that depict divine tales of Radha and Krishna. Audience comments such as “Such an energetic and graceful performance!” and “This is a precious art form. Thank you for sharing this with the world” underscore the cultural significance of the performance. However, it is important to note that despite high view counts, the number of likes and comments remains comparatively low, suggesting the need for more effective strategies to improve audience engagement. A screenshot of a Gotipua dance performance video (Figure 15) and a comment (Figure 16) are provided below.

A screenshot of the “Gotipua Dance Performance by Nakshyatara Gurukul…” on the YouTube channel “SOULFUL ODISHA.”

A screenshot of a particular comment on the “Gotipua Dance Performance by Nakshyatara Gurukul…” on the YouTube channel “SOULFUL ODISHA.”

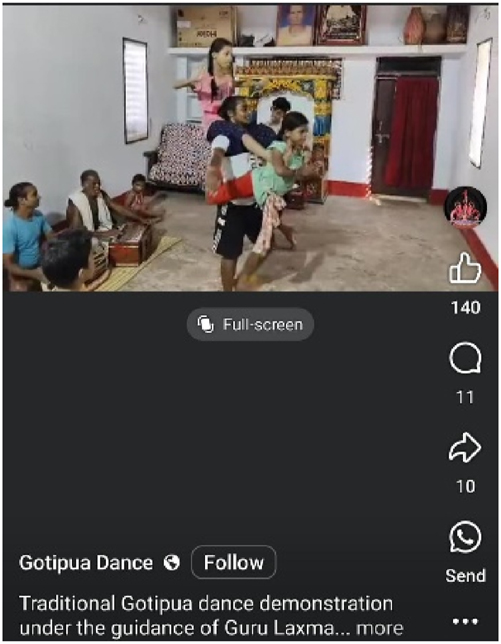

Similarly, on Facebook and Instagram, the presence of Gotipua performances is relatively minimal. Some older and newly created Facebook pages and groups, such as “Gotipua Dance” (4.7k followers), “The Odisha Tourism” (276k followers), “Gotipua Nrutya” (1k followers), and “Gotipua Dance in Odisha” (485 followers), occasionally share pictures and reels of Gotipua performances. For instance, the video titled “Traditional Gotipua…” on the Facebook account “Gotipua Dance” features young performers practicing under the guidance of Guru Laxman Maharana for an upcoming event at their Gurukul. One of the comments on this video reads, “Excellent,” highlighting the appreciation for the tradition. A screenshot of a Gotipua Dance performance video (Figure 17) and a comment (Figure 18) are demonstrated below.

A screenshot of a Gotipua performance video on the Facebook page “Gotipua Dance.”

A screenshot of a particular comment on a Gotipua performance video on the Facebook page “Gotipua Dance.”

Instagram accounts dedicated specifically to Gotipua, such as “gotipuanrutya” (190 followers), “dance_aradhana_” (127 followers), and “dasabhujagotipua” (427 followers), upload relevant content, including posts and reels. However, the lack of informative captions and hashtags significantly limits their engagement and visibility. In addition, the accounts have uploaded fewer reels than pictures, despite the fact that reels are currently prioritized by Instagram’s algorithm and are more likely to appear in users’ feeds. Reels also tend to attract greater levels of engagement such as likes, comments, and shares, particularly among younger audiences who prefer short-form video content.

With regard to Kandhei Nacha, its digital representation remains limited and scattered across various platforms. Notably, there is no YouTube channel solely dedicated to Kandhei Nacha performances. However, some videos and reels are available through a few multi-content YouTube channels. For instance, one prominent video titled “Dhinki Kuta|Kandhei Naacha,” uploaded on the “Life and Time Odisha” channel, garnered 151k views and 1.3k likes. The video depicts a scene titled “Dhinki Dhaana Kuta,” in which puppets engage in household chores such as sifting rice with a bamboo kula,[4] grinding with a chakki,[5] cooking, and cutting freshwater fish. The puppeteers’ mastery in handling the puppets using rods and strings demonstrates the critical importance of synchronization between the narrator and the puppeteer for effective storytelling. Comments such as “ ” (It has turned out very beautiful. Salutations to all the artist brothers) and “

” (It has turned out very beautiful. Salutations to all the artist brothers) and “

” (This is the culture and identity of our Odisha. We must preserve it, as it is on the verge of disappearing in the present times) express admiration and concern for preserving this traditional art form. Another noteworthy video titled “Puppet Dance – Kandhei Nacha Sita Bibhaha Ep 1” (16k views, 1k likes), uploaded on the “DD Odia” channel, portrays a Kandhei Nacha performance based on Sita Bibaha.[6] The narration interweaves key events from Vijaya Dashami,[7] Sita’s Swayamvar,[8] and Rama’s Breaking of the Divine Bow with synchronized puppet movements. The performance creatively integrates themes of feminine power and the victory of good over evil by linking Durga Maa Mahisasur Vadh with Sita Bibaha. A screenshot of a Kandhei Nacha video (Figure 19) and a comment (Figure 20) are demonstrated below.

” (This is the culture and identity of our Odisha. We must preserve it, as it is on the verge of disappearing in the present times) express admiration and concern for preserving this traditional art form. Another noteworthy video titled “Puppet Dance – Kandhei Nacha Sita Bibhaha Ep 1” (16k views, 1k likes), uploaded on the “DD Odia” channel, portrays a Kandhei Nacha performance based on Sita Bibaha.[6] The narration interweaves key events from Vijaya Dashami,[7] Sita’s Swayamvar,[8] and Rama’s Breaking of the Divine Bow with synchronized puppet movements. The performance creatively integrates themes of feminine power and the victory of good over evil by linking Durga Maa Mahisasur Vadh with Sita Bibaha. A screenshot of a Kandhei Nacha video (Figure 19) and a comment (Figure 20) are demonstrated below.

A screenshot of the “Dhinki Kuta Kandhei Nacha…” video on the YouTube channel “Life and Time Odisha.”

A screenshot of a comment on the “Dhinki Kuta Kandhei Nacha…” video on the YouTube channel “Life and Time Odisha.”

On Facebook, Kandhei Nacha has some visibility through short videos such as “The History of Puppetry Tradition ‘Kandhei Nacha’,” “Odisha’s Famous Folk-Art Form Kandhei Naacha,” “Kandhei Nacha: Heart Touching Story,” and “MahaLaxmi Katha,” shared by different pages and groups. Despite being informative, the likes and shares of these videos remain unsatisfactory. Additionally, a few Instagram accounts such as “villagesquareindia” (95.5k followers) and “lifeandtimeodisha” (309 followers) occasionally upload posts on Kandhei Nacha. Nevertheless, these accounts have very few posts and reels on this performance tradition, and their captions often lack detail and the use of hashtags. This omission limits discoverability and diminishes the potential impact of their content.

Moving on to Chaiti Ghoda, a few digital platforms have effectively captured its vibrant and culturally rich performances. The YouTube video titled “CHAITI GHODA” (5.5M views), uploaded on the “Siddharth Bhakti” channel, features a traditional performance by the Keuta[9] community in a rural setting. The performance begins with a recitation of the Guru Brahma Guru Vishnu[10] shloka and transitions into a folk narrative infused with regional songs such as Amaku side diya re, ame tah kaudi wala.[11] The sequence presents a dynamic dialogue between the narrators, who reflect on the relevance of the sacred shloka and traditional songs. In a similar vein, the video titled “Chaiti Ghoda Nacha by Padmashri Utsab Charan Das” (164k views), uploaded by “Odissi Sangita,” highlights both religious and social expressions of Odisha. The audience response has been remarkable. For example, one viewer commented, “

” (The song and music are extremely enchanting. Our heritage and traditions are our pride and glory), emphasizing the beauty of the performance and the importance of cultural preservation. A screenshot of a Chaiti Ghoda performance video (Figure 21) and a comment (Figure 22) are provided below.

” (The song and music are extremely enchanting. Our heritage and traditions are our pride and glory), emphasizing the beauty of the performance and the importance of cultural preservation. A screenshot of a Chaiti Ghoda performance video (Figure 21) and a comment (Figure 22) are provided below.

A screenshot of “CHAITI GHODA…” on the “Sidharth Bhakti” YouTube channel.

A screenshot of a comment on the “CHAITI GHODA…” on the “Sidharth Bhakti” YouTube channel.

Equally significant is the digital portrayal of Dasakathia, which is gaining traction on YouTube. The video “DASKATHIA (Bishaya – Bheema),” uploaded by “MBC TV,” has amassed over 609k views, 2.7k likes, and 103 comments. The performance features two male artists playing traditional instruments such as the kathi[12] or Ram Taali,[13] while singing bhajans in Odia. Another high-engagement video, “Garba Ganjana (Part 1) – Daskathia,” on the “World Music Odia” channel, has 874k views, 4k likes, and 140 comments. This particular performance not only recounts the mythological tales of Brahma and Krishna but also emphasizes themes like women’s empowerment through the stories of Sita, Lakshmi, and Draupadi. Likewise, “DASKATHIA – BHIMA ARJUNA JUDHA” on “Canvas Odisha” narrates an epic battle between Bhima and Arjuna, symbolizing valor and the complexities of dharma. Comments such as “

” (“It is our responsibility to preserve the ancient culture. A beautiful presentation. Victory to Lord Jagannath!”) and “

” (“It is our responsibility to preserve the ancient culture. A beautiful presentation. Victory to Lord Jagannath!”) and “

” (Singing the Dasakathia song in a very beautiful Odia language and a melodious voice) highlight the public’s appreciation for the preservation of traditional arts and the use of melodious Odia language in performance. A screenshot of a Dasakathia performance video (Figure 23) and a comment (Figure 24) are provided below.

” (Singing the Dasakathia song in a very beautiful Odia language and a melodious voice) highlight the public’s appreciation for the preservation of traditional arts and the use of melodious Odia language in performance. A screenshot of a Dasakathia performance video (Figure 23) and a comment (Figure 24) are provided below.

A screenshot of “Garba Ganjana…” on the “Sarthak Music” YouTube channel.

A screenshot of a comment on the “Garba Ganjana…” on the “Sarthak Music” YouTube channel.

On Facebook, a few short reels and images of Dasakathia are posted by pages such as “SHREE TV ODIA” and “Odiart Museum.” One notable reel discusses the decline in popularity of instruments like the Dasakathia[14] and the Khanjini,[15] underlining concerns regarding cultural erosion. Additionally, the “Odisha Tourism” page posted a photograph of a Dasakathia performance, which received 144 likes. Another photo shared by “Odia Samaj Directory” contains detailed descriptive text introducing the art form. On Instagram, posts by accounts such as “ministryofculturegoi” (380k followers) and “food_columnist_” (14.4k followers) also feature Dasakathia performances. A specific post by the Ministry of Culture explains the term “Dasakathia,” while another post by “food_columnist_” titled “Daskathia Dahibara Aloodum” received significant engagement (5,492 likes). A screenshot of an Instagram post on Dasakathia (Figure 25) and a comment (Figure 26) are presented below.

A screenshot of an Instagram post “DASKATHIA DAHIBARA…” on the account “food_columnist_”.

A screenshot of a comment under the Instagram post “DASKATHIA DAHIBARA…” on the account “food_columnist_”.

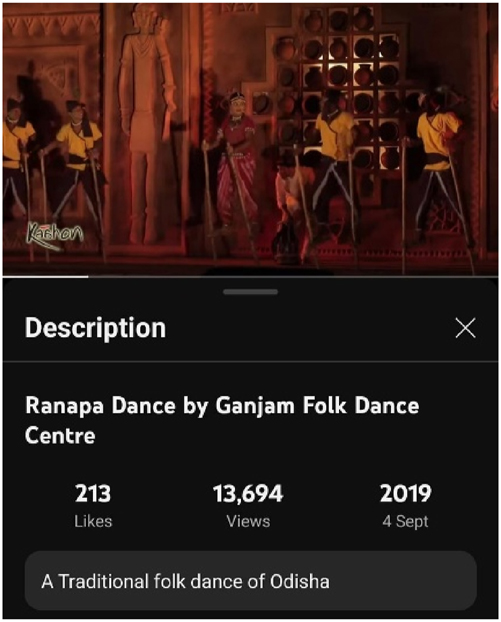

Turning to Ranapa, its digital presence, although limited, features some remarkable videos on YouTube. Two noteworthy videos, “Ranapa Dance by Ganjam Folk Dance Centre” and “Ganjam Folk Dance Centre: Ranapa Dance from Odisha,” both uploaded by the channel “S. Venkat Rao Reddy,” have received 13k views each. These videos showcase performers executing acrobatic movements and intricate footwork while balancing on wooden stilts, accompanied by traditional instruments like the dhol. Such content plays a crucial role in archiving and disseminating this distinctive dance tradition. A screenshot of a Ranapa dance performance video (Figure 27) and a comment (Figure 28) are demonstrated below.

A screenshot of “Ranapa Dance…” on the “S.Venkat Rao Reddy” YouTube channel.

A screenshot of a comment on the “Ranapa Dance…” on the “S.Venkat Rao Reddy” YouTube channel.

On Instagram, accounts such as “discover__odisha” (29.9k followers) and “saswatjoshi” (731k followers) have uploaded posts highlighting Ranapa. For example, a post on “discover__odisha” describes Ranapa as “one of the most famous dance forms majorly from the Ganjam district of Odisha,” receiving 571 likes. Another post on “saswatjoshi” titled “Most difficult style of performance” garnered 7,798 likes. However, despite a high number of likes, both posts have minimal comments and shares, indicating a need for enhanced engagement strategies. A screenshot of an Instagram reel (Figure 29) and a comment (Figure 30) are demonstrated below.

A screenshot of the reel “Most difficult style of performance…” on the Instagram account “saswatjoshi”.

A screenshot of a comment on “Most difficult style of performance…” on the Instagram account “saswatjoshi”.

The above discussion demonstrates that the initiatives taken by different social media platforms are significant for the promotion and preservation of folk performances of Odisha. Our findings reveal that all the selected folk performances have a presence on all three social media platforms. Moreover, the audience’s positive and impressive responses towards these contents reflect the importance of these performances for people. In terms of the authenticity of these contents, it is noticed that the reviewed social media accounts do not compromise the authenticity and originality of the contents to increase the volume of audience engagement. Notably, most of the contents are minimally edited recordings of live performances, which help preserve the cultural values and significance of these performances in the digital space. Apart from these positive aspects of these social media platforms, it has also been observed that these platforms adhere to the applicable standards and policies of the respective platform guidelines. For example, the policies of YouTube, Instagram, and Facebook on intellectual property, hate speech, and appropriate imagery have not been violated by any content on these selected platforms. Pages like “Odissi Dance Houston” state in their description that hate speech and bullying are not permitted. Furthermore, the channels that upload copyrighted materials, for example, “Odisha Vilas,” clearly mention that the content is shared for educational purposes and will be removed upon objection. Some other channels, such as “SRJAN” and “Odisha Dance Academy,” which upload their own creations, explicitly state that their videos contain copyrighted material and cannot be used by others without permission.

It is also important to note that all selected channels avoid practices discouraged by YouTube such as artificial inflation of views or misleading thumbnails. Additionally, most of these social media accounts are not heavily monetized. Advertisements, sponsorships, and other commercial elements are not prominently featured in the selected accounts. Two pages from our selection, such as “SRJAN” and “Odisha Dance Academy,” have a nominal subscription amount. The overall compliance with platform-specific digitization standards reinforces the credibility and authenticity of these efforts to digitally preserve Odisha’s folk traditions. Among the seven performances, Odissi and Pala have strong visibility on social media since these performances are largely presented in physical form, making the recordings readily available for social media uploads. Odissi is a world-renowned dance and Pala is highly revered and respected in every household of Odisha, which leads to their presence in substantial numbers on the digital space. However, the other five performances, which were prominent in earlier times, are now gradually losing significance because of the reduced practice and performances in Odisha. Hence, their visibility on social media is limited and scattered. Therefore, like the Pala and Odissi social media platforms, organized and systematic efforts should be taken to make these performances prominently visible in digital space. Initiatives should be taken by the government and institutions of Odisha to digitally archive the existing recordings, as well as to record performances by senior and emerging artists and share them online. Another observation is that for all performances, the visibility on Facebook and Instagram is comparatively lower than on YouTube. Facebook is widely used by people across all generations and accessed at various times throughout the day. Therefore, showcasing folk performances on Facebook can help these folk performances reach the broader public and attract a global audience. To draw the attention of younger generations, Instagram plays a more significant role, as it is primarily used by youth. Additionally, Instagram’s visual features such as pictures and reels are appealing and can contribute positively in this context. Apart from these, multilingual and detailed descriptions and captions, which are currently not very effective in most posts and videos, can enhance both reach and accessibility. Another observation is that the presence of contents on performances such as behind-the-scenes footage, interviews, and tutorial videos is very limited on social media – uploading content on such interesting matters will increase audience engagement. Additionally, it has been observed that the social media handles reviewed for our study do not utilize all the features provided by their platforms. The specific facilities of YouTube such as long-form video uploads, playlists, and monetization; of Facebook such as public groups, common threads, and event promotion tools; and of Instagram such as reels, tagging, and interactive features like polls are termed as affordances. This concept is explained by the affordance theory (Gibson 1977, 1979), which refers to the possibilities for action provided by objects or environments. Elsewhere, Davis and Chouinard (2016) distinguish between actual and perceived affordances. In the context of social media platforms, actual affordances refer to the capabilities provided by the platforms, such as YouTube’s ability to upload long-form videos or Instagram’s function of creating reels. However, their effectiveness relies on perceived affordances, namely, whether users recognize and actively apply these features based on their needs and intentions. For example, YouTube’s affordances have been utilized to some extent by channels like “GKCM Odissi Research Centre,” “Siddharth Bhakti,” “Life and Time Odisha,” and “PALA Sanskar Odia TV” by uploading long-form videos and creating playlists for archiving folk performances, which demonstrate an effective use of actual affordances. However, the monetization feature, although available, has not been fully leveraged by all channels. Its limited use reflects a gap between the actual affordance (the monetization tool) and the perceived affordance (the artist’s recognition and application of this tool to sustain their content creation). If utilized effectively, monetization could motivate content creators to post systematically, thereby supporting the long-term sustainability of digital archiving. In Facebook and Instagram pages and accounts such as “Odissidance,” “Gotipua Dance in Odisha,” and “eodishaord,” we observe that although certain basic affordances such as group creation, hashtags, and reels are used, many of the key features like event promotion tools, tagging, community building, and polls are not utilized much. These affordances do not merely support technological functions; rather, they shape human behavior and cultural interactions by inviting audience participation. Since the affordances are minimally or not utilized by the social media accounts, many of the contents fail to attract higher numbers of views, likes, and shares. This limits their potential to reach broader audiences and engage with them meaningfully. Consequently, this underscores the need for strategic and comprehensive utilization of all social media affordances to ensure that Odisha’s rich heritage not only survives but evolves and thrives in the digital era.

4 Conclusions

In this article, we have explored the contribution of YouTube, Facebook, and Instagram to the promotion and preservation of selected folk performances of Odisha, namely Odissi, Gotipua, Pala, Kandhei Nacha, Chaiti Ghoda, Ranapa, and Dasakathia. Through an analysis of selected social media handles and their content on folk performances, it becomes evident that the initiatives taken to promote and preserve these traditions are significant. However, the visibility of all folk performances on social media is not uniform. Performances that enjoy greater recognition and visibility among the contemporary population of Odisha, such as Odissi and Pala, are more prominently represented on social media, which is largely due to the widespread availability of their recordings. In contrast, folk performances like Gotipua, Chaiti Ghoda, Ranapa, Dasakathia, and Kandhei Nacha are less visible online, and their presence appears scattered and inconsistent due to limited physical practice and performance in the current era. This situation raises concerns regarding the sustainability of these art forms in the future. To address this, similar initiatives to those undertaken for Odissi and Pala must be implemented for the less practiced performances. Individuals, institutional repositories, and government bodies should actively engage in systematically recording and uploading these performances. Even if physical performances are infrequent, recordings can be created specifically for digital sharing, allowing these traditions to reach a wider audience. Such efforts can foster appreciation, inspire practice and viewership, and ultimately encourage performers and artists to remain engaged with their craft. Social media handles that are actively uploading content related to Odissi and Pala should continue doing so to maintain their visibility and recognition in the future. Among the three platforms studied, YouTube plays a particularly active role in the promotion and preservation of folk performances. However, there are relatively fewer Facebook and Instagram pages dedicated to these traditions. Given that different platforms offer varied affordances for user engagement, Facebook and Instagram also hold significant potential for reaching broader audiences. It has also been observed that not all available affordances of these platforms are being effectively utilized. Therefore, content creators should maximize the use of platform-specific features to enhance visibility, engagement, and archiving of these performances. Doing so will help preserve and sustain these rich cultural traditions for future generations.

To conclude, it should be noted that this article focused only on selected social media platforms and a limited range of folk performances to assess how these channels contribute to preservation and promotion. The study did not explore the role of traditional digital media in supporting these objectives. Future research may be undertaken to address these areas and provide a more comprehensive understanding of digital efforts in cultural preservation.

References

Banerji, A. 2019. Dancing Odissi: Paratopic Performances of Gender and State. Calcutta: Seagull Books.Suche in Google Scholar

Das, K. B., and L. K. Mahapatra. 1979. Folklore of Orissa. India: National Book Trust.Suche in Google Scholar

Davis, J. L., and J. B. Chouinard. 2016. “Theorizing Affordances: From Request to Refuse.” Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society 36 (4): 241–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/0270467617714944.Suche in Google Scholar

Ertürk, N. 2020. “Preservation of Digitized Intangible Cultural Heritage in Museum Storage.” Milli Folklor 16 (128): 100–10.Suche in Google Scholar

Furferi, R., L. Di Angelo, M. Bertini, P. Mazzanti, K. De Vecchis, and M. Biffi. 2024. “Enhancing Traditional Museum Fruition: Current State and Emerging Tendencies.” Heritage Science 12 (1): 20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-024-01139-y.Suche in Google Scholar

Gibson, J. J. 1977. “The Theory of Affordances.” In Perceiving, Acting, and Knowing, edited by R. Shaw, and J. Bransford, 67–82. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum.Suche in Google Scholar

Gibson, J. J. 1979. The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.Suche in Google Scholar

Heath, A., J. Martin, and G. Elgenius. 2007. “Who Do We Think We Are? The Decline of Traditional Social Identities.” In British Social Attitudes: The 23rd Report — Perspectives on a Changing Society, edited by A. Park, J. Curtice, K. Thomson, M. Phillips, and M. Johnson, 2–34. London: Sage.10.4135/9781849208680.n1Suche in Google Scholar

Kothari, S. 2022. “Odissi: From Devasabha to Janasabha.” Marg, A Magazine of the Arts 74 (1): 54.Suche in Google Scholar

Kumar, S. 2012. “Role of Folk Media in Nation Building.” Voice of Research 1 (2): 1–29.Suche in Google Scholar

Liu, Y. 2022. “Application of Digital Technology in Intangible Cultural Heritage Protection.” Mobile Information Systems 2022 (1): 1–8, https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/7471121.Suche in Google Scholar

Mohapatra, A.Dr. 2017. “The Essence of Popular Folk Dances of Odisha.” IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Science 22 (1): 29–32. https://doi.org/10.9790/0837-2201052932.Suche in Google Scholar

Mondal, K. 2018. “Delicate Faces, Virtuosic Bodies.” Performance Research 23 (1): 37–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/13528165.2018.1460445.Suche in Google Scholar

Oladokun, B. D., Y. A. Ajani, B. C. Ukaegbu, and E. A. Oloniruha. 2024. “Cultural Preservation through Immersive Technology: The Metaverse as a Pathway to the Past.” Preservation, Digital Technology & Culture 53 (3): 157–64. https://doi.org/10.1515/pdtc-2024-0015.Suche in Google Scholar

Panda, S. 2024. “The Other Side of Language, Literature, and Living: A Call to Hedge the Dying Art.” Indialogs 11: 103–18. https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/indialogs.255.Suche in Google Scholar

Patra, U. 2017. “Tracing the History and Evolution of Pala.” Lokaratna X: 37–52.Suche in Google Scholar

Sahoo, B. K. 2019. “Contribution of Nath Yogi, Chakuliapanda, Pala and Dasakathia to the Society and Culture of Orissa.” Think India Journal- Vichar Nyas Foundation 22 (4): 6539–54.Suche in Google Scholar

Samantaray, S. 2014. “A Shared Heritage of Humanity: A Glimpse into the Folklore of Odisha.” Labyrinth: An International Refereed Journal of Postmodern Studies 5 (1): 31–8.Suche in Google Scholar

Satpathy, M. K. 2016. Festivals and Folk Theatre of Odisha. Gurgaon, India: Shubhi Publications.Suche in Google Scholar

Slumkoski, C. 2012. “History on the Internet 2.0: The Rise of Social Media.” Acadiensis 41 (2): 153–62.Suche in Google Scholar

Susanti, S., and I. Koswara. 2017. “Menyatukan Perbedaan Melalui Seni Budaya Sunda.” MediaTor (Jurnal Komunikasi) 10 (2): 143–55. https://doi.org/10.29313/mediator.v10i2.2739.Suche in Google Scholar

Tarannum, S. 2016. “Mapping Odisha’s Indigenous Theatre.” Dialogue 12 (1): 58–67. https://www.dialoguethejournal.com/index.php/Dialogue/article/view/213.Suche in Google Scholar

Trillo, C., R. Aburamadan, S. Mubaideen, D. Salameen, and B. C. N. Makore. 2020. “Towards a Systematic Approach to Digital Technologies for Heritage Conservation. Insights from Jordan.” Preservation Digital Technology & Culture 49 (4): 121–38. https://doi.org/10.1515/pdtc-2020-0023.Suche in Google Scholar

Yeganeh, K. H. 2024. “Navigating Cultural Shifts: Globalization’s Impact on Society and Business.” In Abstracts of the 5th World Conference on Arts, Humanities, Social Sciences and Education, 101. Vienna, Austria: Eurasia Conference.10.62422/978-81-968539-1-4-064Suche in Google Scholar

Yoshida, I., T. Kobayashi, S. Sapkota, and K. Akkhavong. 2011. “Evaluating Educational Media Using Traditional Folk Songs (‘lam’) in Laos: A Health Message Combined with Oral Tradition.” Health Promotion International 27 (1): 52–62, https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dar086.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Technology, Preservation, and Resilience in an Era of Change: Editor’s Note

- Articles

- Newly Discovered Archival Logic: Functions Emerging from the Records in Contexts Standard

- Traversing Rock Climbers’ Oral Histories to Podcast Platforms: Processes, Analytics, and Digital Library Impact

- VGG-Based Feature Extraction for Classifying Traditional Batik Motifs Using Machine Learning Models

- The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on the Production and Editing of Audiovisual Content

- Navigation of Cultural Heritage in the Digital Age: The Role of Social Media Platforms in the Preservation of Selected Folk Performances of Odisha

- Review

- Saving Ukrainian Cultural Heritage Online (SUCHO)

- News and Comments

- PDT&C Editorial Board Position Paper on the Emerging Crisis in the Cultural Heritage and Preservation Sectors

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Technology, Preservation, and Resilience in an Era of Change: Editor’s Note

- Articles

- Newly Discovered Archival Logic: Functions Emerging from the Records in Contexts Standard

- Traversing Rock Climbers’ Oral Histories to Podcast Platforms: Processes, Analytics, and Digital Library Impact

- VGG-Based Feature Extraction for Classifying Traditional Batik Motifs Using Machine Learning Models

- The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on the Production and Editing of Audiovisual Content

- Navigation of Cultural Heritage in the Digital Age: The Role of Social Media Platforms in the Preservation of Selected Folk Performances of Odisha

- Review

- Saving Ukrainian Cultural Heritage Online (SUCHO)

- News and Comments

- PDT&C Editorial Board Position Paper on the Emerging Crisis in the Cultural Heritage and Preservation Sectors